Supplemental Digital Content is available in the text.

Keywords: Bangladesh, pneumonia, etiology, childhood, PERCH

Background:

Pneumonia remains the leading infectious cause of death among children <5 years, but its cause in most children is unknown. We estimated etiology for each child in 2 Bangladesh sites that represent rural and urban South Asian settings with moderate child mortality.

Methods:

As part of the Pneumonia Etiology Research for Child Health study, we enrolled children 1–59 months of age with World Health Organization–defined severe and very severe pneumonia, plus age-frequency-matched controls, in Matlab and Dhaka, Bangladesh. We applied microbiologic methods to nasopharyngeal/oropharyngeal swabs, blood, induced sputum, gastric and lung aspirates. Etiology was estimated using Bayesian methods that integrated case and control data and accounted for imperfect sensitivity and specificity of the measurements.

Results:

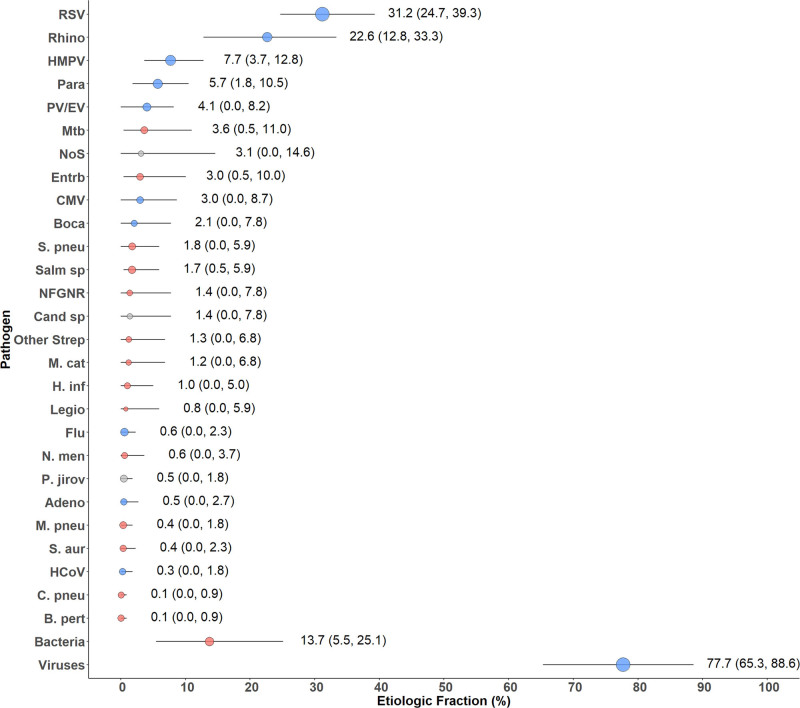

We enrolled 525 cases and 772 controls over 24 months. Of the cases, 9.1% had very severe pneumonia and 42.0% (N = 219) had infiltrates on chest radiograph. Three cases (1.5%) had positive blood cultures (2 Salmonella typhi, 1 Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae). All 4 lung aspirates were negative. The etiology among chest radiograph–positive cases was predominantly viral [77.7%, 95% credible interval (CrI): 65.3–88.6], primarily respiratory syncytial virus (31.2%, 95% CrI: 24.7–39.3). Influenza virus had very low estimated etiology (0.6%, 95% CrI: 0.0–2.3). Mycobacterium tuberculosis (3.6%, 95% CrI: 0.5–11.0), Enterobacteriaceae (3.0%, 95% CrI: 0.5–10.0) and Streptococcus pneumoniae (1.8%, 95% CrI: 0.0–5.9) were the only nonviral pathogens in the top 10 etiologies.

Conclusions:

Childhood severe and very severe pneumonia in young children in Bangladesh is predominantly viral, notably respiratory syncytial virus.

Pneumonia remains the leading infectious cause of child mortality, accounting for 900,000 deaths among children <5 years old.1,2 Both Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) and pneumococcal conjugate vaccines (PCV) are reducing these major known causes of pneumonia. Other causes now contribute significant pneumonia burden, with related death and morbidity concentrated in low- and middle-income countries.3–5 In Bangladesh, 1 of the 5 countries that contribute over half of the world’s pneumonia cases in children <5 years, 1.87 million pneumonia cases were diagnosed annually as of 2016.1 When the Pneumonia Etiology Research for Child Health (PERCH) study launched in 2012, 21,000 Bangladeshi children died of pneumonia.2 While global pneumonia incidence is decreasing,6 most incident pneumonia cases occur in Asia, with Bangladesh remaining a principal contributor.

We describe Bangladesh results from the PERCH study, a standardized etiologic evaluation of hospitalized severe and very severe pneumonia among children 1-59 months of age in 7 African and Asian countries.7

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Population

There were 2 PERCH sites in Bangladesh, Matlab and Dhaka; both had low-HIV-seroprevalence and low seasonal malaria transmission (prevalence <0.2%).8–11 Bangladesh is a lower-middle-income country with 163 million population and an under-5 child mortality rate of 37.6 deaths per 1000 live births (Dhaka: 38/1000; Matlab: 31.6/1000).8,9 Hib vaccine was introduced in 2009 with 90% coverage in 2017,12 leading to substantial reductions in pneumonia and meningitis.13,14 PCV was introduced in 2015, after PERCH ended.

Matlab, a rural region located 50 km southeast of Dhaka, has Matlab Hospital and a Health and Demographic Surveillance System (HDSS), both operated by the International Center for Diarrheal Disease Research, Bangladesh (icddr,b). The Matlab HDSS service area had a population of 118,926, including 12,531 children <5 years of age during the study.15 In Dhaka, children living within the Kamalapur icddr,b HDSS area were eligible for enrollment. This is a rapidly growing, densely populated urban community of 350,000 population during the PERCH study, of which approximately 10% participate in demographic surveillance through stratified random selection, including approximately 7000 children <5 years old. Children enrolled in the Dhaka site were also participating in long-standing active respiratory disease surveillance in which households were visited once weekly and assessed for fever and signs of respiratory infection; those with symptoms were directed to the Kamalapur study clinic for evaluation and treatment, as previously described.16,17

Selection of Participants

Cases and community controls 1–59 months of age were enrolled between January 1, 2012, and January 9, 2014, in Dhaka, and between January 1, 2012, and January 7, 2014, in Matlab. Details of entry criteria for the PERCH study have been described.7,18

Cases had severe or very severe pneumonia, defined using modified World Health Organization criteria (2005 definitions), namely cough and/or difficulty in breathing, plus danger signs (central cyanosis, difficulty breast-feeding/drinking, vomiting everything, multiple or prolonged convulsions, lethargy/unconsciousness or head nodding) defining “very severe pneumonia,” or lower chest wall indrawing defining “severe pneumonia.”18–20 We excluded children with auscultatory wheezing if lower chest wall indrawing resolved after standardized bronchodilator therapy (see study protocol and standard operating procedures21). Radiological pneumonia was defined using World Health Organization criteria22,23; chest radiograph–positive (CXR+) cases were defined as those with findings of consolidation or other infiltrates.

At the Kamalapur study clinic, operated and staffed by the study team, we enrolled patients from 8 am to 5 pm, 7 days a week, before referring cases to icddr,b Dhaka Hospital for management. After hours, we enrolled patients admitted directly to the hospital. In Matlab, patients admitted to the pneumonia ward of icddr,b Matlab Hospital were screened and enrolled by hospital physicians 24 hours daily, 7 days a week. Possible minor disruptions in enrolment occurred between March and May 2013 during political unrest, including potentially 10 cases missed in Matlab.

Controls were randomly selected from the Kamalapur HDSS Dhaka site and the Matlab icddr,b HDSS service area. Controls were frequency-matched to cases on age using 4 age groups (1–5, 6–11, 12–23, 24–59 months) with the goal of enrolling at least 25 controls per month, and 10–15 per site. Those meeting the PERCH case definition were excluded but otherwise those with acute respiratory infections were included. Control enrollment was done at home visits, followed by specimen collection at the Kamalapur clinic (if not, then Dhaka Hospital) or Matlab Hospital.

Laboratory Testing of Collected Samples

Details of clinical samples and laboratory testing have been published.24 Briefly, all participants provided nasopharyngeal/oropharyngeal (NP/OP) swabs for polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for respiratory pathogens using a 33-pathogen multiplex quantitative PCR (FTD Resp-33; Fast-track Diagnostics, Sliema, Malta) and culture (plus serotyping) for pneumococcus, blood for pneumococcal PCR and serum for antibiotic activity testing.25 Cases also provided blood for bacterial culture and C-reactive protein, and induced sputum (or gastric aspirate, n = 3) for Mycobacterium tuberculosis culture. Selected cases in Dhaka underwent transthoracic percutaneous direct fine-needle aspiration.25 In Dhaka, all specimens were collected and initially processed at the Kamalapur Clinic, then transported to the icddr,b main site laboratory in Dhaka twice daily for testing, except lung aspirates which were collected in the icddr,b Dhaka Hospital. At Matlab, all specimens were collected at the hospital; complete blood count, conventional blood cultures, serum for C-reactive protein and mycobacterial cultures of sputum and gastric aspirate were done at the Matlab Hospital laboratory; all other specimens were shipped daily to the Dhaka icddr,b laboratory. Cases and controls were not tested for HIV because the prevalence among pregnant women in these settings is known to be extremely low,26,27 and the local institutional review board deemed it unethical to test for it accordingly. Positivity was defined using quantitative PCR density thresholds for four pathogens where there was similar prevalence in cases and controls; these include S. pneumoniae (≥ 2.2 log10 copies/mL) from whole blood28 and Streptococcus pneumoniae (≥ 6.9 log10 copies/ml)29 Haemophilus influenzae (≥ 5.9 log10 copies/mL)30, cytomegalovirus (CMV, ≥ 4.9 log10 copies/mL), and Pj (≥ 4 log10 copies/mL) NP/OP (CMV threshold analysis available from authors).

Statistical Analysis

Logistic regression was used to estimate odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) of the prevalence of pathogens identified on NP/OP PCR in cases compared with controls adjusted for age in months, site and all other pathogens detected on NP/OP PCR to account for associations between pathogens. The percent of pneumonia due to each pathogen was estimated using the PERCH Integrated Analysis (PIA) method. The PIA, described in detail elsewhere,24,31,32 is a Bayesian nested partially latent class analysis that integrates the results for each case from blood culture, NP/OP PCR, whole blood PCR for pneumococcus and induced sputum culture for M. tuberculosis. The PIA also integrates test results from controls to account for imperfect test specificity of NP/OP PCR and whole blood PCR. Blood culture results (excluding contaminants) and M. tuberculosis results were assumed to be 100% specific. The PIA accounts for imperfect sensitivity of each test/pathogen measurement by using a priori estimates of their sensitivity (ie, estimates regarding the plausibility range of sensitivity which varied by laboratory test method and pathogen). Sensitivity of blood culture was reduced if blood volume was low (≤1.5 mL) or if antibiotics were administered before specimen collection. Sensitivity of NP/OP PCR for Streptococcus pneumoniae and H. influenzae was reduced if antibiotics were administered before specimen collection (Table, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/INF/D809).

As a Bayesian analysis, both the list of pathogens and their starting “prior” etiologic fraction values were specified a priori, which favored no pathogen over another (ie, “uniform”). The pathogens selected for inclusion in the analysis included any noncontaminant bacteria detected by culture in blood at any of the 9 PERCH sites, regardless of whether it was observed at the Bangladesh sites specifically, M. tuberculosis, and all of the multiplex quantitative PCR pathogens except those considered invalid because of poor assay specificity (Klebsiella pneumoniae33 and Moraxella catarrhalis). A category called “Pathogens Not Otherwise Specified” was also included to estimate the fraction of pneumonia caused by pathogens not tested for or not observed. A child negative for all pathogens would still be assigned an etiology, which would be either one of the explicitly estimated pathogens (implying a “false negative,” accounting for imperfect sensitivity of certain measurements) or Pathogens Not Otherwise Specified. The model assumes that each child’s pneumonia was caused by a single pathogen.

All analyses were adjusted for age (<1 vs. ≥1 year) and site (Dhaka and Matlab) to account for differences in pathogen prevalence by these factors; analyses stratified by pneumonia severity could not adjust for age due to small sample size. For results stratified by case clinical data (eg, to CXR+, very severe, etc), the test results from all controls were used. However, for analyses stratified by age, only data from controls representative of that age group were used.

The PIA estimated both the individual and population-level etiology probability distributions, each summing to 100% across pathogens where each pathogen has a probability ranging from 0% to 100%. The population-level etiologic fraction estimate for each pathogen was approximately the average of the individual case probabilities and was provided with a 95% credible interval (95% CrI), the Bayesian analog of the CI.

Data collection was managed within an online system (The Emmes Corporation, Rockville, MD).34 Statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC), R Statistical Software 3.3.1 (The R Development Core Team, Vienna, Austria) and Bayesian inference software JAGS 4.2.0 (http://mcmc-jags.sourceforge.net/). The PIA analysis was performed using a publicly available R package, named the Bayesian Analysis Kit for Etiology Research (https://github.com/zhenkewu/baker).

Ethics

We obtained written informed consent for participation in the study from parents or legal guardians of cases and controls, as described previously.35 The study was approved by the Research Review Committee and the Ethical Review Committee of icddr,b and the Institutional Review Board of the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

RESULTS

Study Participants

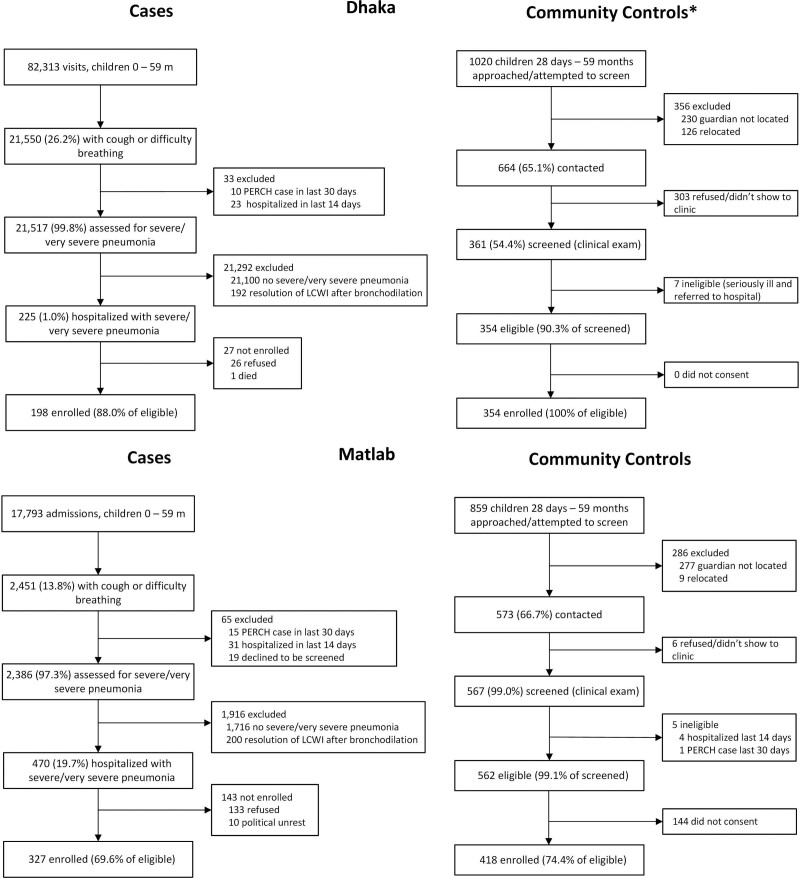

We enrolled 525 cases, 198 (88%) of 225 eligible in Dhaka, and 327 (70%) of 470 eligible in Matlab (Fig. 1); 33 were recommended for hospitalization but not admitted, 32 (97.0%) because the parent refused.

FIGURE 1.

Case and control enrollment flow diagram by site. Data were extrapolated for 4 of 24 months for which control screening data were missing at the Dhaka site. Only the number of enrolled cases contains no extrapolated data. LCWI indicates lower chest wall indrawing.

In Dhaka, 354 (34.4%) controls were enrolled among 1020 randomly selected; 356 could not be screened because the guardian could not be located or the family migrated, 303 refused participation (primarily due to recent participation in a respiratory infection surveillance assessment) and 7 were ineligible (Fig. 1). At Matlab, 418 (48.7%) controls of 859 randomly selected were enrolled; 277 were not screened because the guardian was not located, 9 relocated, 6 declined screening, 5 were ineligible and 144 refused participation (Fig. 1).

Half (49.0%) of cases were <1 year old and 25.3% had been exposed to antibiotics within 24 hours before specimen collection (Table 1), versus 1.4% of controls. Moderate to severe malnutrition, defined by weight-for-age Z score below −2, was more common in cases (38.9%) than controls (23.4%, P < 0.001) and cases were less likely to be female (36.4% vs. 52.1%; P < 0.001). Coverage with 2 or more doses of pentavalent vaccine was high in both cases (85.7%) and controls (94.3%). While prevalences of some of these factors may have varied by site, their associations with case status were similar (Table, Supplemental Digital Content 2, http://links.lww.com/INF/D810).

TABLE 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Cases and Controls

| All Cases | CXR-positive Cases* | Controls | |

|---|---|---|---|

| All | 525 | 219 | 772 |

| Age | |||

| Median age in months (IQR) | 12 (5, 20) | 12 (6, 21) | 11 (5, 23) |

| 1–5 mo | 136 (25.9) | 50 (22.8) | 221 (28.6) |

| 6–11 mo | 121 (23.0) | 50 (22.8) | 168 (21.8) |

| 12–23 mo | 178 (33.9) | 81 (37.0) | 196 (25.4) |

| 24–59 mo | 90 (17.1) | 38 (17.4) | 187 (24.2) |

| Female | 191 (36.4) | 87 (39.7) | 402 (52.1) |

| Season of enrollment | |||

| Monsoon (June–October) | 270 (51.4) | 119 (54.3) | 320 (41.5) |

| Dry (November–May) | 255 (48.6) | 100 (45.7) | 452 (58.5) |

| Respiratory tract illness† (controls only) | n/a | n/a | 169 (21.9) |

| Number of pentavalent vaccine doses received‡ | |||

| None | 26 (5.0) | 8 (3.7) | 12 (1.6) |

| 1 | 49 (9.4) | 20 (9.2) | 32 (4.2) |

| 2 | 30 (5.7) | 12 (5.5) | 72 (9.4) |

| 3 | 418 (79.9) | 178 (81.7) | 650 (84.9) |

| Pentavalent fully vaccinated for age‡ | |||

| <1-yr old | 214 (83.9) | 85 (85.9) | 346 (88.9) |

| ≥1-yr old | 263 (98.1) | 114 (95.8) | 364 (96.6) |

| ≥1 measles dose received (among children >10.5 mo) | 266 (84.7) | 110 (80.9) | 384 (88.1) |

| Weight-for-age (WHO) Z scores | |||

| >−2 Z scores | 321 (61.1) | 118 (53.9) | 591 (76.6) |

| −3 ≤ Z scores ≤ −2 | 146 (27.8) | 70 (32.0) | 138 (17.9) |

| <−3 Z scores | 58 (11.1) | 31 (14.2) | 43 (5.6) |

| Prematurity (gestational age <37 wk) | 30 (5.9) | 16 (7.4) | 23 (3.0) |

| Prior diagnosis with wheeze or asthma | 100 (19.0) | 56 (25.6) | 49 (6.3) |

| Antibiotic use | |||

| Serum antibiotic activity | 118 (23.9) | 45 (21.6) | 10 (1.4) |

| Parental report of antibiotics | 186 (35.6) | 78 (35.9) | 57 (7.4) |

| Administered at study hospital before specimen collection§ | 41 (7.8) | 21 (9.6) | n/a |

| Evidence of antibiotic exposure before specimen collection¶ | 126 (25.3) | 52 (24.6) | 10 (1.4) |

*CXR-positive cases: presence of alveolar consolidation and/or other infiltrates on chest radiograph.

†Respiratory tract illness defined as (1) cough and/or runny nose or (2) at least 1 of ear discharge, wheezing or difficulty breathing in the presence of either a temperature of ≥38.0°C within past 48 h or a history of sore throat.

‡Numbers reflect children who received pentavalent vaccine (diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis-Haemophilus influenzae type b-hepatitis B vaccine). An additional 32 children, including 6 cases and 26 controls, received diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis-only, not Penta. For children <1 yr, diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis fully vaccinated defined as: received at least 1 dose and up-to-date for age based on the child’s age at enrollment, doses received and country schedule (allowing 4-wk window each for dose). For children >1 yr, defined as 3+ doses.

§Reported by clinician.

¶Presence of antibiotics by serum, antibiotics at the referral hospital, clinician report of antibiotics before blood specimen collection or antibiotics before specimen collection based on time of specimen collection and time of antibiotic administration. Only criterion applicable to controls is serum. Restricted to children with a blood specimen obtained.

IQR indicates interquartile range; n/a, not applicable; WHO, World Health Organization.

Few (11.1%) cases had very severe pneumonia, who primarily met the case definition due to head nodding (8.2% of all cases) (Table 2). Two cases died, both from Dhaka (Table 2). Hypoxemia was uncommon (8.2%) but was reported 4 times more often in Dhaka (15.2%) than Matlab (4.0%) (age-adjusted OR 4.5; 95% CI: 2.3–8.9; P < 0.001) and was more common among very severe cases (45.3%) than among severe (4.0%; P < 0.001). Most cases had crackles (93.1%) and wheeze (97.0%); only 15.0% had fever.

TABLE 2.

Demographic and Characteristics of Cases by Site

| Both Sites | Matlab | Dhaka | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Cases | CXR-positive Casesa | All Cases | CXR-positive Casesa | All Cases | CXR-positive Casesa | |

| All | 525 | 219 | 327 | 101 | 198 | 118 |

| CXR result | ||||||

| Any consolidation | 58 (11.1) | 58 (26.5) | 31 (9.5) | 31 (30.7) | 27 (13.8) | 27 (22.9) |

| Other infiltrate only | 161 (30.9) | 161 (73.5) | 70 (21.5) | 70 (69.3) | 91 (46.4) | 91 (77.1) |

| Normal | 254 (48.8) | 0 (0.0) | 185 (56.9) | 0 (0.0) | 69 (35.2) | 0 (0.0) |

| Uninterpretable | 48 (9.2) | 0 (0.0) | 39 (12.0) | 0 (0.0) | 9 (4.6) | 0 (0.0) |

| Season of enrollment | ||||||

| Monsoon (June–October) | 270 (51.4) | 119 (54.3) | 163 (49.8) | 54 (53.5) | 107 (54.0) | 65 (55.1) |

| Dry (November–May) | 255 (48.6) | 100 (45.7) | 164 (50.2) | 47 (46.5) | 91 (46.0) | 53 (44.9) |

| Median duration of illness in days (IQR)b | 3 (2, 5) | 3 (2, 5) | 3 (2, 4) | 3 (2, 4) | 4 (3, 6) | 4 (3, 6) |

| Duration of illnessb (d) | ||||||

| 0–2 | 163 (31.0) | 61 (27.9) | 117 (35.8) | 38 (37.6) | 46 (23.2) | 23 (19.5) |

| 3–5 | 270 (51.4) | 107 (48.9) | 174 (53.2) | 48 (47.5) | 96 (48.5) | 59 (50.0) |

| >5 | 92 (17.5) | 51 (23.3) | 36 (11.0) | 15 (14.9) | 56 (28.3) | 36 (30.5) |

| Median duration of hospitalization in days (IQR) | 3 (2, 5) | 3 (2, 4) | 4 (3, 5) | 4 (3, 5) | 3 (2, 4) | 3 (2, 4) |

| Duration of hospitalization (d) | ||||||

| 0–2 | 133 (25.7) | 61 (28.1) | 39 (12.1) | 9 (9.1) | 94 (48.2) | 52 (44.1) |

| 3–5 | 306 (59.2) | 127 (58.5) | 227 (70.5) | 73 (73.7) | 79 (40.5) | 54 (45.8) |

| >5 | 78 (15.1) | 29 (13.4) | 56 (17.4) | 17 (17.2) | 22 (11.3) | 12 (10.2) |

| Oxygen use at admission | 24 (4.6) | 12 (5.5) | 8 (2.4) | 1 (1.0) | 16 (8.1) | 11 (9.3) |

| Hypoxemiac | 43 (8.2) | 22 (10.0) | 13 (4.0) | 3 (3.0) | 30 (15.2) | 19 (16.1) |

| Tachypnead | 489 (93.1) | 210 (95.9) | 292 (89.3) | 93 (92.1) | 197 (99.5) | 117 (99.2) |

| Tachycardiae | 140 (26.7) | 54 (24.7) | 105 (32.1) | 28 (27.7) | 35 (17.7) | 26 (22.0) |

| Very severe pneumoniaf | 53 (10.1) | 27 (12.3) | 26 (8.0) | 9 (8.9) | 27 (13.6) | 18 (15.3) |

| Head nodding | 43 (8.2) | 19 (8.7) | 26 (8.0) | 9 (8.9) | 17 (8.6) | 10 (8.5) |

| Central cyanosis | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.8) |

| Multiple or prolonged convulsions | 5 (1.0) | 4 (1.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (2.5) | 4 (3.4) |

| Lethargyg | 11 (2.1) | 7 (3.2) | 2 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | 9 (4.5) | 7 (5.9) |

| Unable to feed | 15 (2.9) | 7 (3.2) | 4 (1.2) | 0 (0.0) | 11 (5.6) | 7 (5.9) |

| Vomiting everything | 3 (0.6) | 2 (0.9) | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.0) | 2 (1.7) |

| Crackles | 489 (93.1) | 210 (95.9) | 293 (89.6) | 93 (92.1) | 196 (99.0) | 117 (99.2) |

| Wheeze on auscultation | 509 (97.0) | 213 (97.3) | 319 (97.6) | 100 (99.0) | 190 (96.0) | 113 (95.8) |

| Grunting | 13 (2.5) | 5 (2.3) | 11 (3.4) | 5 (5.0) | 2 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Nasal flaring | 40 (7.6) | 13 (5.9) | 30 (9.2) | 8 (7.9) | 10 (5.1) | 5 (4.2) |

| Fever (temperature ≥38°C) | 79 (15.0) | 38 (17.4) | 45 (13.8) | 16 (15.8) | 34 (17.2) | 22 (18.6) |

| Leukocytosish | 269 (55.2) | 123 (60.0) | 161 (55.1) | 49 (55.7) | 108 (55.4) | 74 (63.2) |

| CRP ≥ 40 mg/L | 49 (10.3) | 26 (12.9) | 26 (8.9) | 9 (9.9) | 23 (12.5) | 17 (15.3) |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | ||||||

| 0–7.5 | 8 (1.6) | 6 (2.9) | 2 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (3.1) | 6 (5.1) |

| 7.6–13.5 | 465 (95.5) | 196 (95.6) | 278 (95.2) | 86 (97.7) | 187 (95.9) | 110 (94) |

| >13.5 | 14 (2.9) | 3 (1.5) | 12 (4.1) | 2 (2.3) | 2 (1.0) | 1 (0.9) |

| Blood culture volume (mL) | ||||||

| 1 to <2 | 197 (39.5) | 90 (42.7) | 100 (33.2) | 29 (31.2) | 97 (49.0) | 61 (51.7) |

| 2 to <3 | 288 (57.7) | 119 (56.4) | 191 (63.5) | 63 (67.7) | 97 (49.0) | 56 (47.5) |

| ≥3 | 14 (2.8) | 2 (1.0) | 10 (3.3) | 1 (1.1) | 4 (2.0) | 1 (0.9) |

| Antibiotic use | ||||||

| Serum antibiotic activity | 118 (23.9) | 45 (21.6) | 84 (28.3) | 21 (22.8) | 34 (17.3) | 24 (20.7) |

| Parental report of antibiotics | 186 (35.6) | 78 (35.9) | 108 (33.2) | 30 (30.3) | 78 (39.4) | 48 (40.7) |

| Administered at study hospital before blood specimen collectioni | 41 (7.8) | 21 (9.6) | 29 (8.9) | 11 (10.9) | 12 (6.1) | 10 (8.5) |

| Evidence of antibiotic exposure before blood specimen collectionj | 126 (25.3) | 52 (24.6) | 87 (28.9) | 24 (25.8) | 39 (19.7) | 28 (23.7) |

| Missing 30-d vital status | 9 (1.7) | 3 (1.4) | 6 (1.8) | 1 (1.0) | 3 (1.5) | 2 (1.7) |

| Died in hospital or within 30 d of admission | 5 (1.0) | 2 (0.9) | 2 (0.6) | 1 (1.0) | 3 (1.5) | 1 (0.9) |

| Died in hospital | 2 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Died postdischargek | 3 (0.6) | 2 (0.9) | 2 (0.6) | 1 (1.0) | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.9) |

Percentages are based on the numbers with available data. For the majority of variables, missingness was <1%, except for duration of hospitalization (8 [1.5%]), CRP (49 [9.3%]) and hemoglobin (38 [7.2%]). Blood culture volume and antibiotic exposure before blood collection exclude the 26 (5%) of cases missing a blood culture specimen.

aCXR-positive cases: presence of alveolar consolidation and/or other infiltrates on chest radiograph.

bDuration of cough, difficulty breathing, fever or wheeze, whichever is longest.

cOxygen saturation <92% on room air at admission or oxygen requirement (if no room air reading available).

dTachypnea: respiratory rate (RR) ≥ 60 for age < 2 mo; RR ≥ 50 for age 2–11 mo; RR ≥ 40 for age 12+ mo.

eTachycardia: 0–11 mo > 160 beats per minute; 12–35 mo > 150 beats per minute; 36–59 mo > 140 beats per minute.

fPresence of one of the following danger signs: head nodding, central cyanosis, multiple or prolonged convulsions, lethargy, unable to feed or vomiting everything.

gLethargy: responds to voice (V), pain (P), or unresponsive (U) (V, P, or U on Alert, Verbal, Pain, Unresponsive scale).

hLeukocytosis defined as white blood cell count ≥15,000/µL.

iPer clinician report.

jPresence of antibiotics by serum, antibiotics at the referral hospital, clinician report of antibiotics before specimen collection or antibiotics before blood culture specimen collection based on time of specimen collection and time of antibiotic administration.

kDenominator restricted to children discharged alive with known vital status at 30 d from admission (window of 21–90 d). None died within 7 d of discharge.

CRP indicates C-reactive protein; IQR, interquartile range.

CXRs were available from 99% of cases and 219 (42.0%) were CXR+ (Table 2); the proportion CXR+ was lower at Matlab (31.0%) than at Dhaka (59.6%, P < 0.001), partly due to more uninterpretable CXRs at Matlab (12.0% vs. 4.6%). Demographic and clinical characteristics did not change meaningfully when restricted to CXR+ cases (Tables 1 and 2). Pretreatment with antibiotics more common at Matlab than Dhaka among CXR-negative cases (27.9% vs. 13.7%; P < 0.001) but was similar among CXR+ cases (25.8% vs. 23.7%; Table 2).

Only 3 (1.5%) cases, all from Dhaka, were blood culture positive: 2 had Salmonella typhi (1 was CXR+) and 1 (CXR+) had both Escherichia coli and K. pneumoniae, which were grouped in analyses as Enterobacteriaceae (Table 3). Blood culture contamination was 7.2%. Four CXR+ cases had lung aspirates collected (all from Dhaka) within 3 days of admission; all were PCR and culture negative. Two (0.4%) cases (1 CXR+) had M. tuberculosis detected by induced sputum culture. Of these, only those with findings on chest radiograph were considered confirmed for pneumonia and included in the primary analysis.

TABLE 3.

Cases With a Pathogen Detected by Blood Culture or Mycobacterium tuberculosis Detected in Induced Sputum Specimen by Culture

| Case | Site | Severity | Age (mo) | Pathogens Detected on Blood Culture | Pathogens Detected on NP/OP PCR | TB Positive on Induced Sputum | Chest radiograph | Antibiotic Pretreatment Before Specimen Collection | Comorbidity* | Died in Hospital or Within 30 d of Discharge | Duration of Hospitalization (d) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Dhaka | Severe | 18 | Salmonella typhi | CMV Rhinovirus |

No | Consolidation + other infiltrate | No | No | No | 3 |

| 2 | Dhaka | Severe | 45 | S. typhi | Haemophilus influenzaeParainfluenza 4Staphylococcus aureus | No | Normal | No | Premature (32 wk) | No | 5 |

| 3 | Dhaka | Very severe | 12 | Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae† | CMV H. influenzae Moraxella catarrhalis Streptococcus pneumoniae |

No | Other infiltrate | No | No | No | 5 |

| 4 | Dhaka | Very severe | 56 | - |

S. pneumoniae

S. aureus |

Yes | Consolidation + other infiltrate | No | Yes (severe malnutrition) | No | 15 |

| 5 | Matlab | Severe | 6 | - | CMV Influenza A S. pneumoniae |

Yes | Normal | Yes | No | No | 4 |

*Includes prematurity, heart disease, developmental delay, congenital abnormality and severe malnutrition.

†Categorized as Enterobacteriaceae in etiology analyses.

CMV indicates cytomegalovirus; TB, M. tuberculosis.

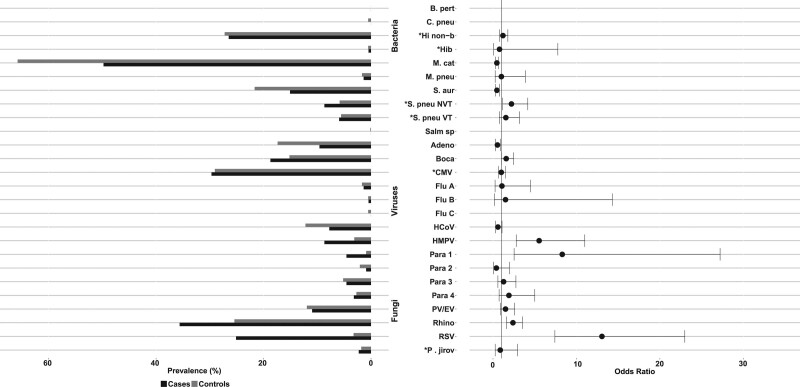

Virtually all cases (99.4%) and controls (99.9%) had an organism detected on NP/OP, and 87.8% and 86.4%, respectively, carried a mixture of bacteria and viruses (Table, Supplemental Digital Content 3, http://links.lww.com/INF/D811). NP/OP organisms most strongly associated with CXR+ pneumonia cases compared with controls were all viral: respiratory syncytial virus (RSV; CXR+ case prevalence = 25.1%; control prevalence = 3.2%; OR 12.9; 95% CI: 7.3–22.8), parainfluenza 1 virus (case = 4.6%; control = 0.9%; OR 8.0; 95% CI: 2.4–26.3) and human metapneumovirus (HMPV) A/B (case = 8.7%; control = 3.1%; OR 5.8; 95% CI: 2.9–11.5) (Fig. 2 and Table, Supplemental Digital Content 4, http://links.lww.com/INF/D812). Pneumococcus was commonly detected in cases (67.6%) but less frequently than in controls (82.1%; OR 0.55; 95% CI: 0.37–0.83); however, high pneumococcal load (≥6.9 log10 copies/mL) was more common in cases (14.6%) than in controls (10.6%; OR 2.3; 95% CI: 1.4–3.8), except in cases with evidence of antibiotic use before specimen collection (5.2% vs. 15.6% without; P = 0.023). Rhinovirus was commonly found among both CXR+ cases (35.6%) and controls (25.4%), as was high load (≥4.9 log10 copies/mL) cytomegalovirus (29.7% vs. 29.1%). Hib (CXR+ cases 0.9%; controls 1.7%) and influenza viruses A, B and C (1.9% vs. 2.7%) were not commonly detected.

FIGURE 2.

Prevalence and odds ratios* of organisms detected in NP/OP specimens, CXR-positive cases versus controls. *Prevalence defined using NP/OP PCR density thresholds for 4 pathogens: P. jirovecii, 4 log10 copies/mL; H. influenzae, 5.9 log10 copies/mL; CMV, 4.9 log10 copies/mL; S. pneumoniae, 6.9 log10 copies/mL). Refer to Supplemental Digital Content 4, http://links.lww.com/INF/D812, for NP/OP PCR results based on positivity. Pathogens are ordered alphabetically among bacteria and then viruses and fungi. Odds ratios adjusted for age, site and all other pathogens. Odd ratios could not be calculated due to zero cells for the following pathogens: B. pertussis, C. pneumoniae, Salmonella species and Flu C. Results presented for both Bangladesh sites combined; refer to Supplemental Digital Content 5, http://links.lww.com/INF/D813, for select results stratified by site. Adeno indicates Adenovirus; B. pert, Bordetella pertussis; Boca, Human bocavirus; C. pneu, Chlamydophila pneumoniae; CMV, cytomegalovirus; CXR+, chest radiograph positive (consolidation and/or other infiltrate); Flu, influenza virus; HCoV, Human coronavirus; Hib, Haemophilus influenzae type b; Hi non-b, Haemophilus influenzae non-b; HMPV, Human metapneumovirus A/B; M. cat, Moraxella catarrhalis; M. pneu, Mycoplasma pneumoniae; NP/OP, nasopharyngeal/oropharyngeal; NVT, non-PCV13 vaccine type; Para, Parainfluenza virus; P. jirov, Pneumocystis jirovecii; PV/EV, Parechovirus/Enterovirus; Rhino, rhinovirus; RSV, respiratory syncytial virus A/B; S. aur, Staphylococcus aureus; S. pneu, Streptococcus pneumoniae; Salm sp, Salmonella species; VT, PCV13 vaccine type.

NP/OP results were generally similar between Dhaka and Matlab (Table, Supplemental Digital Content 5, http://links.lww.com/INF/D813), except Matlab had 2 RSV seasons while Dhaka had 1 (Figure, Supplemental Digital Content 6, http://links.lww.com/INF/D814), almost doubling RSV-positives in Matlab compared with Dhaka (cases: 33.3% vs. 18.7%, P = 0.0003; controls: 4.8% vs. 1.7%, P = 0.013). The low RSV positivity in Dhaka corresponded to low case enrolments during those months (3–5 per month vs. >30 in Matlab). Other significant NP/OP prevalence differences between sites included S. pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus, and Parainfluenza virus 3 among cases, and S. pneumoniae, Pneumocystis jirovecii, cytomegalovirus and HMPV A/B among controls (Table, Supplemental Digital Content, http://links.lww.com/INF/D813).

The estimated etiologies among CXR+ cases were predominantly viral (77.7%, 95% CrI: 65.3–88.6), driven primarily by RSV (31.2%, 95% CrI: 24.7–39.3) and rhinovirus (22.6%, 95% CrI: 12.8–33.3), followed by HMPV (7.7%, 95% CrI: 3.7–12.8) and parainfluenza virus (5.7%, 95% CrI: 1.8–10.5), which were the only other pathogens with an etiologic fraction above 5% (Fig. 3 and Table, Supplemental Digital Content 7, http://links.lww.com/INF/D815). Influenza virus caused only 0.6% (95% CrI: 0.0–2.3) due to low prevalence. Non-viral top 10 etiologies included M. tuberculosis (3.6%, 95% CrI: 0.5–11.0), Enterobacteriaceae species (3.0%, 95% CrI: 0.5–10.0) and S. pneumoniae (1.8%, 95% CrI: 0.0–5.9). Pathogens targeted by vaccines included in the Bangladesh national immunization program during PERCH (Bordetella pertussis, Hib and M. tuberculosis) accounted for only 3.9% (95% CrI: 0.5–11.0) of CXR+ pneumonia cases; the total fraction for vaccine-preventable etiologies (adding PCV13-type S. pneumoniae, influenza virus A/B and Neisseria meningitidis) was 5.4% (95% CrI: 0.9–13.2). Differences by site were not statistically significant: M. tuberculosis (6.2% vs. 0.7%), parainfluenza virus 3 (3.7% vs. 0.2%) and Enterobacteriaceae (5.1% vs. 0.6%) were higher at Dhaka, while RSV (39.9% vs. 23.7%) and parechovirus/enterovirus (7.7% vs. 1.0%) were higher at Matlab (Figure, Supplemental Digital Content 8, http://links.lww.com/INF/D816). Results from analyses stratified by severity or age yielded no additional notable findings. Results of analyses of all cases (ie, regardless of CXR findings) were similar to CXR+ cases with the exception of a greater fraction attributed to PV/EV (10.1% vs. 4.1%) and rhinovirus (30.4% vs. 22.6%) resulting in a greater fraction due to viruses overall (91.7% vs. 77.7%) (Table, Supplemental Digital Content 7, http://links.lww.com/INF/D815).

FIGURE 3.

Integrated etiology results for HIV-uninfected/CXR-positive cases. Other Strep includes Streptococcus pyogenes and Enterococcus faecium. NFGNR includes Acinetobacter species and Pseudomonas species. Enterobacteriaceae includes Escherichia coli, Enterobacter species and Klebsiella species, excluding mixed Gram-negative rods. CXR+ defined as consolidation and/or other infiltrate on chest radiograph. Bacterial summary excludes Mtb. Analysis adjusted for age and site. Pathogens estimated at the subspecies level but grouped to the species level for display (Parainfluenza virus type 1, 2, 3 and 4; S. pneumoniae PCV 13 and S. pneumoniae non-PCV 13 types; H. influenzae type b and H. influenzae non-b; influenza A, B and C). Exact figures and subspecies and serotype disaggregation (eg, PCV-13 type and non-PCV-13 type) are given in Supplemental Digital Content 7, http://links.lww.com/INF/D815. Line represents the 95% credible interval. The size of the symbol is scaled based on the ratio of the estimated etiologic fraction to its standard error. Of 2 identical etiologic fraction estimates, the estimate associated with a larger symbol is more informed by the data than the priors. Adeno indicates Adenovirus; B. pert, Bordetella pertussis; Boca, Human bocavirus; C. pneu, Chlamydophila pneumoniae; Cand sp, Candida species; CMV, cytomegalovirus; Entrb, Enterobacteriaceae; Flu, influenza virus A, B and C; H. inf, Haemophilus influenzae; HCoV, Coronavirus; HMPV, Human metapneumovirus A/B; Legio, Legionella species; M. cat, Moraxella catarrhalis; M. pneu, Mycoplasma pneumoniae; Mtb, Mycobacterium tuberculosis; NFGNR, nonfermentative gram-negative rods; N. men, Neisseria meningitidis; NoS, Not Otherwise Specified (ie, pathogens not tested for); P. jirov, P. jirovecii; Para, parainfluenza virus types 1, 2, 3 and 4; PV/EV, parechovirus/enterovirus; Rhino, human rhinovirus; RSV, respiratory syncytial virus A/B; S. aur, Staphylococcus aureus; S. pneu, Streptococcus pneumoniae; Salm sp, Salmonella species.

DISCUSSION

The preponderance (77.7%) of virus-attributed severe and very severe childhood pneumonia in Bangladesh was notable, possibly explaining the 97% prevalence of wheezing. RSV and rhinovirus were the dominant causes at both the Dhaka (urban) and Matlab (rural) sites, despite differences in pneumonia incidence16,36–38 and pathogen-specific seasonality,39,40 which should simplify disease control policy. Among the differences, RSV caused more pneumonia than rhinovirus (39.9% vs. 23.7%) in Matlab, whereas in Dhaka, they were similar (23.7% vs. 21.6%), reflecting the additional RSV peak at Matlab. Parechovirus/enterovirus contributed 7.7% at Matlab versus only 1.0% in Dhaka; Salmonella species was 3.0% in Dhaka but only 0.3% at Matlab, perhaps reflecting the high urban prevalence of S. Typhi and Paratyphi in children.41–43

While the leading pathogens in Bangladesh were found at other PERCH sites,24 their relative contributions varied, implying differences in pathogen burden and disease control prioritization. For example, after standardizing on age and severity, bacterial pathogens only accounted for 9.7% of pneumonia in Bangladesh compared with over 30% at all other PERCH sites except Kenya (16.8%).24 Although we cannot rule out a possibly higher fraction of bacterial disease in the greater Bangladesh population since children from the PERCH catchment areas likely had earlier access to effective treatment, the findings for Bangladesh suggest a focus on antiviral vaccines and therapeutic agents.

Cases in Matlab were less likely to have a prior wheezing history (1.8%) than those in Dhaka (47.5%) (Supplemental Digital Content 2, http://links.lww.com/INF/D810). These differences are related to differences in the health systems at the rural versus urban sites. In the former, outpatient complaints are attended either by community health workers or at government-run clinics, where documentation on clinical findings and diagnoses is limited, resulting in under-reporting of nonsevere illnesses like outpatient wheezing. The urban clinic is staffed entirely by project physicians trained to both identify and document diagnoses, including wheezing illnesses using standardized criteria on case report forms. Importantly, the rates of wheezing diagnoses among children in both Dhaka and Matlab by trained PERCH study physicians are identical, suggesting that the true background rates of wheezing-related illnesses in these 2 populations are not dissimilar.

Rhinovirus has been implicated as a lower respiratory pathogen in recent studies,44–46 including Bangladesh,47 and as a leading cause of acute48–52 and recurrent wheezing,53–58 as well as the development of asthma53,59,60 in young children. The PERCH study found that Bangladesh had the highest prevalence of rhinoviruses among the study sites.24 The current study was not designed to determine the relationship between wheezing and specific pathogens, although this has been explored previously61,62; however, Bangladesh, with the greatest population density and crowding of any country,63 had both the highest prevalence of rhinovirus, together with one of the highest prevalences of RSV, another pathogen associated with wheezing in young children.48,64–67 Wheezing was much higher in Bangladesh (97.3% among CXR+) than at the other PERCH sites (range 10.6%–38.8%). The highest prevalence of wheezing among young children adds further evidence to the contribution of rhinovirus to the burden of wheezing-related illnesses, particularly in settings of crowding, poor household ventilation and indoor air pollution.68–70 Further study is indicated on the contribution of viruses and environmental factors to reversible lower airway obstructive diseases in this setting.

Despite the absence of pneumococcal vaccination, the etiologic fraction attributed to S. pneumoniae was small (1.8%). The PERCH case definition was restricted to hospitalized children presenting with severe and very severe pneumonia, meaning that children presenting to hospital earlier in their illness or to outpatient facilities were not enrolled. Many children receive effective antibiotic therapy at presentation, likely resulting in bacterial pneumonias not progressing to case-defining severe or very severe pneumonia. In PERCH, 1 in 4 severe/very severe pneumonias was treated with antimicrobials before presentation, likely reducing the number of bacteremic pneumococcal cases and the number of pneumococcal pneumonias. We previously estimated invasive pneumococcal disease incidence of 447 episodes/100,000 child-years,16 which is on par with that of The Gambia pre-PCV introduction.71 This was based on 5946 blood cultures over 7600 child-years of observation from children with suspected bacterial infection (diagnosed with upper respiratory infection, otitis media, meningitis, sepsis, or pneumonia of any severity) at the urban Kamalapur site.16 Of the 34 pneumococcal blood isolates detected in this earlier study, only 8 presented with pneumonia (23.5%) and none were severe or very severe pneumonia; 4 of the 34 pneumococcal cases progressed to severe or very severe pneumonia from either nonsevere pneumonia or other nonpneumonia initial diagnoses. Furthermore, we continued recovering pneumococcal blood isolates throughout the study period in PERCH-ineligible children at background rates similar to those previously documented. Therefore, if bacteremia is a time-limited phase that occurs earlier in illness onset, or if there are different types of pneumococcal pneumonia illnesses, including severe/very severe pneumonia that do not involve bacteremia, then the PERCH case definition may have selected against children with active pneumococcal bacteremia. It will be important to monitor the impact of PCV-10 in this population on pneumococcal and total pneumonia disease burden in both nonsevere and severe pneumonia.

Previously, high influenza incidence (102 episodes/1000 child-years) as ascertained by tissue culture has been documented in this population, contributing 11% of all childhood pneumonia.17 However, in PERCH, <2% of cases and controls had influenza despite using more sensitive PCR. Ongoing surveillance17,72 indicated low influenza circulation during PERCH (January 2012 to December 2013; Figure, Supplemental Digital Content 9, http://links.lww.com/INF/D817). A major disruption to influenza seasonality occurred following the emergence of influenza A(H1N1)pdm09.73 By October 2009, influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 circulation fell, and apart from a brief 4- to 6-week period, we had unusually low influenza A activity between July 2009 when it arrived in Bangladesh to April 2013. The nonpandemic A/H1N1 and the current A/H3N2 were substantial drivers of childhood lower respiratory illness,17 whereas A(H1N1)pdm09 has behaved as a milder virus with substantial subclinical infection (22%), even during the first wave.73 Influenza B is associated with lower respiratory infection but has a lower incidence than influenza A and less association with pneumonia in this population. The similarly low detection among community controls is additional evidence that circulation was lower than historical levels.

Given the high prevalence of RSV in severe childhood pneumonia and the different circulatory patterns between the sites, as previously observed,39 surveillance will remain an important tool in determining the optimal use of RSV vaccines. While influenza virus circulation across Bangladesh has been well described,47,74,75 less has been done for other respiratory viruses. Our RSV observations raise the possibility that other viruses might have heterogeneous circulatory patterns, with implications for case management and prevention, which only surveillance would detect.

There were several limitations to this study, in addition to those cited in our main article,24 which could have affected our results. First, 1 in 5 cases, including 25.3% of those <1 year old had been exposed to antibiotics within 24 hours before specimen collection, thus likely reducing the fraction of true bacterial pathogen positives. Second, although 99% of cases provided CXRs, 9.2% of these were uninterpretable, likely reducing the number of CXR-positives and our analytical power for CXR-associated illnesses. Third, was patient recruitment. The Kamalapur urban site was closed during evenings. Although the population is accustomed to self-referral at the local hospital, it is conceivable that some cases were missed. In Matlab, 30% of eligible cases were not enrolled due to withholding of parental consent. Both could have affected our results. Fourth, although applicable for all of the PERCH sites, our surveillance data underscored the limitations of how only 2 years of observation can affect pathogen detection, in this case influenza, which was barely detectable during PERCH. Finally, there is the potential that cases with very severe pneumonia were misclassified which may have affected our etiology estimate. Given that the 2 sites were comparable on head-nodding rates, we estimate we would have missed or misclassified 5% of cases in Matlab assuming the sites are similar on the rates of other very severe defining symptoms (13.6% of cases with very severe pneumonia minus 8.6% with head nodding, based on observations in Dhaka). This equates to missing a maximum of 16 cases with very severe pneumonia. We were not able to estimate etiology by danger sign due to small sample sizes; therefore, we cannot hypothesize how this would have affected the overall etiology estimate. However, it is unlikely that excluding or misclassifying 5% of cases in Matlab (3% overall) would have meaningfully changed the etiologic findings.

Our observations have specific implications for surveillance: case definitions can affect etiologic ascertainment, laboratory-supported syndromic surveillance needs to be regional to prioritize interventions and surveillance needs to be sufficiently long term to identify secular trends in pathogen circulation beyond seasonality, preferably in multiple locations to identify heterogeneous circulation. Together, these observations enable adaptive and responsive disease control policy and implementation.

CONCLUSIONS

Childhood severe and very severe pneumonia in Bangladesh is predominantly viral, notably RSV. RSV is thus an important target for vaccine and therapeutic intervention. The low fraction attributed to S. pneumoniae and influenza may have been influenced by study design and timing, respectively, and these cannot be ruled out as important pneumonia agents. Our findings suggest that further laboratory-supported observation of childhood pneumonia is warranted, particularly as pneumonia-relevant vaccine programs are implemented.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We offer sincere thanks to the children and families who participated in this study. We acknowledge the study of all PERCH contributors who were involved in data collection at the local sites and central laboratories, members of the PERCH Chest Radiograph Reading Panel and Shalika Jayawardena and Rose Watt from Canterbury Health Laboratories. We also acknowledge the substantial contributions of the other members of the PERCH Study Group not listed as coauthors:

Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, MD: Orin S. Levine (former principal investigator, current affiliation Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Seattle, WA), Andrea N. DeLuca, Amanda J. Driscoll, Nicholas Fancourt, Wei Fu, E. Wangeci Kagucia, Ruth A. Karron, Mengying Li, Daniel E. Park, Qiyuan Shi, Zhenke Wu, Scott L. Zeger; The Emmes Company, Rockville, MD: Nora L. Watson; Nuffield Department of Clinical Medicine, University of Oxford, United Kingdom: Jane Crawley; Medical Research Council, Basse, The Gambia: Stephen R. C. Howie (site principal investigator); KEMRI-Wellcome Trust Research Programme, Kilifi, Kenya: J. Anthony G. Scott (site principal investigator and PERCH co-principal investigator, joint affiliation with London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, London, United Kingdom); Division of Infectious Disease and Tropical Pediatrics, Department of Pediatrics, Center for Vaccine Development, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, and Centre pour le Développement des Vaccins (CVD-Mali), Bamako, Mali: Karen L. Kotloff (site principal investigator); Medical Research Council: Respiratory and Meningeal Pathogens Research Unit and Department of Science and Technology/National Research Foundation: Vaccine Preventable Diseases, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa: Shabir A. Madhi (site principal investigator); Thailand Ministry of Public Health – U.S. CDC Collaboration, Nonthaburi, Thailand: Henry C. Baggett (site principal investigator), Susan A. Maloney (former site principal investigator); Boston University School of Public Health, Boston, MA, and University Teaching Hospital, Lusaka, Zambia: Donald M. Thea (site principal investigator); Canterbury Health Laboratories, Christchurch, New Zealand: Trevor P. Anderson, Joanne Mitchell.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

PERCH was supported by grant 48968 from The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation to the International Vaccine Access Center, Department of International Health, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

W.A.B. reported funding from Sanofi, PATH, Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, and contributions to contemporaneous studies from Serum Institute of India, LTD, Roche, and Sanofi. M.D.K. has received funding for consultancies from Merck, Pfizer, Novartis, and grant funding from Merck and Pfizer. M. M. H. has received grant funding from Pfizer. L. L. H. has received grant funding from GlaxoSmithKline, Pfizer, and Merck. K. L. O. has received grant funding from GlaxoSmithKline and Pfizer and participates on technical advisory boards for Merck, Sanofi-Pasteur, PATH, Affinivax, and Clear-Path. C.P. has received grant funding from Merck. The funding mentioned here for these authors was unrelated to this study.

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal’s website (www.pidj.com).

REFERENCES

- 1.GBD 2016 Lower Respiratory Infections Collaborators. Estimates of the global, regional, and national morbidity, mortality, and aetiologies of lower respiratory infections in 195 countries, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Infect Dis. 2018;18:1191–1210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu L, Oza S, Hogan D, et al. Global, regional, and national causes of under-5 mortality in 2000-15: an updated systematic analysis with implications for the sustainable development goals. Lancet. 2016;388:3027–3035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bénet T, Sylla M, Messaoudi M, et al. Etiology and factors associated with pneumonia in children under 5 years of age in Mali: a prospective case-control study. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0145447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oumei H, Xuefeng W, Jianping L, et al. Etiology of community-acquired pneumonia in 1500 hospitalized children. J Med Virol. 2018;90:421–428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jonnalagadda S, Rodríguez O, Estrella B, et al. Etiology of severe pneumonia in Ecuadorian children. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0171687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rudan I, O’Brien KL, Nair H, et al. ; Child Health Epidemiology Reference Group (CHERG). Epidemiology and etiology of childhood pneumonia in 2010: estimates of incidence, severe morbidity, mortality, underlying risk factors and causative pathogens for 192 countries. J Glob Health. 2013;3:010401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Levine OS, O’Brien KL, Deloria-Knoll M, et al. The pneumonia etiology research for child health project: a 21st century childhood pneumonia etiology study. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54(suppl 2):S93–S101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Bank. Bangladesh - Country snapshot. Washington, DC, 2016. Available at: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/654391476782032287/Bangladesh-Country-snapshot. Accessed November 30, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 9.You D, Hug L, Ejdemyr S, et al. ; United Nations Inter-agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation (UN IGME). Global, regional, and national levels and trends in under-5 mortality between 1990 and 2015, with scenario-based projections to 2030: a systematic analysis by the UN Inter-agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation. Lancet. 2015;386:2275–2286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Streatfield PK, Khan WA, Bhuiya A, et al. HIV/AIDS-related mortality in Africa and Asia: evidence from INDEPTH health and demographic surveillance system sites. Glob Health Action. 2014;7:25370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haque U, Overgaard HJ, Clements AC, et al. Malaria burden and control in Bangladesh and prospects for elimination: an epidemiological and economic assessment. Lancet Glob Health. 2014;2:e98–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Health Organization/UNICEF. WHO/UNICEF Estimates of National Immunization Coverage (WUENIC). 2018. Available at: http://www.who.int/immunization/monitoring_surveillance/data/en/. Accessed July 26, 2018.

- 13.Baqui AH, El Arifeen S, Saha SK, et al. Effectiveness of Haemophilus influenzae type B conjugate vaccine on prevention of pneumonia and meningitis in Bangladeshi children: a case-control study. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2007;26:565–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sultana NK, Saha SK, Al-Emran HM, et al. Impact of introduction of the Haemophilus influenzae type b conjugate vaccine into childhood immunization on meningitis in Bangladeshi infants. J Pediatr. 2013;163(1 suppl):S73–S78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research Bangladesh (icddrb). Health and demographic surveillance system - matlab vol. 37, registration of health and demographic events. Sci Rep. 2006;93:1–118. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brooks WA, Breiman RF, Goswami D, et al. Invasive pneumococcal disease burden and implications for vaccine policy in urban Bangladesh. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2007;77:795–801. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brooks WA, Goswami D, Rahman M, et al. Influenza is a major contributor to childhood pneumonia in a tropical developing country. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2010;29:216–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Deloria-Knoll M, Feikin DR, Scott JA, et al. ; Pneumonia Methods Working Group. Identification and selection of cases and controls in the pneumonia etiology research for child health project. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54(suppl 2):S117–S123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.World Health Organization. Management of the Child with a Serious Infection or Severe Malnutrition: Guidelines for Care at First-Referral Level in Developing Countries. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Scott JA, Wonodi C, Moïsi JC, et al. ; Pneumonia Methods Working Group. The definition of pneumonia, the assessment of severity, and clinical standardization in the Pneumonia Etiology Research for Child Health study. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54 Suppl 2:S109–S116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.The PERCH Study Group. The Pneumonia Etiology Research for Child Health Project (PERCH) Study Materials. 2012. https://www.jhsph.edu/ivac/resources/perch-background-and-methods/. Accessed June 27, 2019.

- 22.World Health Organization. Pneumonia Vaccine Trial Investigators’ Group & World Health Organization. (2001). Standardization of interpretation of chest radiographs for the diagnosis of pneumonia in children / World Health Organization Pneumonia Vaccine Trial Investigators’ Group. World Health Organization. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/66956 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fancourt N, Deloria Knoll M, Barger-Kamate B, et al. Standardized interpretation of chest radiographs in cases of pediatric pneumonia from the PERCH Study. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;64(suppl_3):S253–S261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pneumonia Etiology Research for Child Health (PERCH) Study Group. Causes of severe pneumonia requiring hospital admission in children without HIV infection from Africa and Asia: the PERCH multi-country case-control study. Lancet (London, England). 2019;394:757–779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Driscoll AJ, Karron RA, Morpeth SC, et al. Standardization of laboratory methods for the PERCH Study. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;64(suppl_3):S245–S252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Azim T, Chowdhury EI, Reza M, et al. Prevalence of infections, HIV risk behaviors and factors associated with HIV infection among male injecting drug users attending a needle/syringe exchange program in Dhaka, Bangladesh. Subst Use Misuse. 2008;43:2124–2144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Azim T, Khan SI, Haseen F, et al. HIV and AIDS in Bangladesh. J Health Popul Nutr. 2008;26:311–324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Deloria Knoll M, Morpeth SC, Scott JAG, et al. Evaluation of Pneumococcal Load in Blood by Polymerase Chain Reaction for the Diagnosis of Pneumococcal Pneumonia in Young Children in the PERCH Study. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;64(suppl_3):S357–S367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baggett HC, Watson NL, Deloria Knoll M, et al.Density of Upper Respiratory Colonization With Streptococcus pneumoniae and Its Role in the Diagnosis of Pneumococcal Pneumonia Among Children Aged <5 Years in the PERCH Study. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;64(suppl_3):S317–S27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Park DE, Baggett HC, Howie SRC, et al.Colonization Density of the Upper Respiratory Tract as a Predictor of Pneumonia-Haemophilus influenzae, Moraxella catarrhalis, Staphylococcus aureus, and Pneumocystis jirovecii. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;64(suppl_3):S328–S36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wu Z, Deloria-Knoll M, Zeger SL. Nested partially latent class models for dependent binary data; estimating disease etiology. Biostatistics. 2017;18:200–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Deloria Knoll M, Fu W, Shi Q, et al. Bayesian estimation of pneumonia etiology: epidemiologic considerations and applications to the pneumonia etiology research for Child Health Study. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;64(suppl_3):S213–S227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zar HJ, Barnett W, Stadler A, et al. Aetiology of childhood pneumonia in a well vaccinated South African birth cohort: a nested case-control study of the Drakenstein Child Health Study. Lancet Respir Med. 2016;4:463–472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Watson NL, Prosperi C, Driscoll AJ, et al. Data management and data quality in PERCH, a large international case-control study of severe childhood pneumonia. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;64(suppl_3):S238–S244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.DeLuca AN, Regenberg A, Sugarman J, et al. Bioethical considerations in developing a biorepository for the Pneumonia Etiology Research for Child Health project. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54(suppl 2):S172–S179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zaman K, Baqui AH, Yunus M, et al. Acute respiratory infections in children: a community-based longitudinal study in rural Bangladesh. J Trop Pediatr. 1997;43:133–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brooks WA, Santosham M, Naheed A, et al. Effect of weekly zinc supplements on incidence of pneumonia and diarrhoea in children younger than 2 years in an urban, low-income population in Bangladesh: randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2005;366:999–1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Homaira N, Luby SP, Petri WA, et al. Incidence of respiratory virus-associated pneumonia in urban poor young children of Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2009-2011. PLoS One. 2012;7:e32056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stockman LJ, Brooks WA, Streatfield PK, et al. Challenges to evaluating respiratory syncytial virus mortality in Bangladesh, 2004-2008. PLoS One. 2013;8:e53857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nasreen S, Luby SP, Brooks WA, et al. Population-based incidence of severe acute respiratory virus infections among children aged <5 years in rural Bangladesh, June-October 2010. PLoS One. 2014;9:e89978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brooks WA, Hossain A, Goswami D, et al. Bacteremic typhoid fever in children in an urban slum, Bangladesh. Emerg Infect Dis. 2005;11:326–329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Charles RC, Sheikh A, Krastins B, et al. Characterization of anti-Salmonella enterica serotype Typhi antibody responses in bacteremic Bangladeshi patients by an immunoaffinity proteomics-based technology. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2010;17:1188–1195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sheikh A, Bhuiyan MS, Khanam F, et al. Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi-specific immunoglobulin A antibody responses in plasma and antibody in lymphocyte supernatant specimens in Bangladeshi patients with suspected typhoid fever. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2009;16:1587–1594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.García-García ML, Calvo C, Pozo F, et al. Spectrum of respiratory viruses in children with community-acquired pneumonia. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2012;31:808–813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Guittet V, Brouard J, Vabret A, et al. [Rhinovirus and acute respiratory infections in hospitalized children. Retrospective study 1998-2000]. Arch Pediatr. 2003;10:417–423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Iwane MK, Prill MM, Lu X, et al. Human rhinovirus species associated with hospitalizations for acute respiratory illness in young US children. J Infect Dis. 2011;204:1702–1710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Homaira N, Luby SP, Hossain K, et al. Respiratory viruses associated hospitalization among children aged <5 years in Bangladesh: 2010-2014. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0147982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chung JY, Han TH, Kim SW, et al. Detection of viruses identified recently in children with acute wheezing. J Med Virol. 2007;79:1238–1243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jartti T, Aakula M, Mansbach JM, et al. Hospital length-of-stay is associated with rhinovirus etiology of bronchiolitis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2014;33:829–834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jartti T, Lehtinen P, Vuorinen T, et al. Respiratory picornaviruses and respiratory syncytial virus as causative agents of acute expiratory wheezing in children. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10:1095–1101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Korppi M, Kotaniemi-Syrjänen A, Waris M, et al. Rhinovirus-associated wheezing in infancy: comparison with respiratory syncytial virus bronchiolitis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2004;23:995–999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rakes GP, Arruda E, Ingram JM, et al. Rhinovirus and respiratory syncytial virus in wheezing children requiring emergency care. IgE and eosinophil analyses. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;159:785–790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jackson DJ, Gangnon RE, Evans MD, et al. Wheezing rhinovirus illnesses in early life predict asthma development in high-risk children. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;178:667–672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lemanske RF, Jr, Jackson DJ, Gangnon RE, et al. Rhinovirus illnesses during infancy predict subsequent childhood wheezing. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;116:571–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Midulla F, Pierangeli A, Cangiano G, et al. Rhinovirus bronchiolitis and recurrent wheezing: 1-year follow-up. Eur Respir J. 2012;39:396–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ramilo O, Rodriguez-Fernandez R, Mejias A. Respiratory syncytial virus, rhinoviruses, and recurrent wheezing: unraveling the riddle opens new opportunities for targeted interventions. JAMA Pediatr. 2019;173:520–521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rossi GA, Colin AA. Infantile respiratory syncytial virus and human rhinovirus infections: respective role in inception and persistence of wheezing. Eur Respir J. 2015;45:774–789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Valkonen H, Waris M, Ruohola A, et al. Recurrent wheezing after respiratory syncytial virus or non-respiratory syncytial virus bronchiolitis in infancy: a 3-year follow-up. Allergy. 2009;64:1359–1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Calişkan M, Bochkov YA, Kreiner-Møller E, et al. Rhinovirus wheezing illness and genetic risk of childhood-onset asthma. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1398–1407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Everard ML. The relationship between respiratory syncytial virus infections and the development of wheezing and asthma in children. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;6:56–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dawood FS, Fry AM, Goswami D, et al. Incidence and characteristics of early childhood wheezing, Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2004-2010. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2016;51:588–595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Havers FP, Fry AM, Goswami D, et al. Population-based incidence of childhood pneumonia associated with viral infections in Bangladesh. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2019;38:344–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Central Intelligence Agency. Bangladesh. In: The World Factbook. 2018. Available at: https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/resources/the-world-factbook/geos/bg.html. Accessed April 12, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Farah MM, Padgett LB, McLario DJ, et al. First-time wheezing in infants during respiratory syncytial virus season: chest radiograph findings. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2002;18:333–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bont L, Steijn M, Van Aalderen WM, et al. Seasonality of long term wheezing following respiratory syncytial virus lower respiratory tract infection. Thorax. 2004;59:512–516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chang J. Current progress on development of respiratory syncytial virus vaccine. BMB Rep. 2011;44:232–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mansbach JM, Piedra PA, Teach SJ, et al. ; MARC-30 Investigators. Prospective multicenter study of viral etiology and hospital length of stay in children with severe bronchiolitis. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2012;166:700–706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Murray EL, Brondi L, Kleinbaum D, et al. Cooking fuel type, household ventilation, and the risk of acute lower respiratory illness in urban Bangladeshi children: a longitudinal study. Indoor Air. 2012;22:132–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Murray EL, Klein M, Brondi L, et al. Rainfall, household crowding, and acute respiratory infections in the tropics. Epidemiol Infect. 2012;140:78–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ram PK, Dutt D, Silk BJ, et al. Household air quality risk factors associated with childhood pneumonia in urban Dhaka, Bangladesh. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2014;90:968–975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Cutts FT, Zaman SM, Enwere G, et al. ; Gambian Pneumococcal Vaccine Trial Group. Efficacy of nine-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine against pneumonia and invasive pneumococcal disease in The Gambia: randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2005;365:1139–1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research Bangladesh (icddrb). Population-based influenza surveillance, Dhaka. Heal Sci Bull. 2006;4:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Nasreen S, Rahman M, Hancock K, et al. Infection with influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 during the first wave of the 2009 pandemic: evidence from a longitudinal seroepidemiologic study in Dhaka, Bangladesh. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2017;11:394–398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Azziz-Baumgartner E, Alamgir AS, Rahman M, et al. Incidence of influenza-like illness and severe acute respiratory infection during three influenza seasons in Bangladesh, 2008-2010. Bull World Health Organ. 2012;90:12–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zaman RU, Alamgir AS, Rahman M, et al. Influenza in outpatient ILI case-patients in national hospital-based surveillance, Bangladesh, 2007-2008. PLoS One. 2009;4:e8452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.