Abstract

Background:

Women with inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) commonly report an increase in their IBD symptoms related to their menstrual cycle. Hormonal contraceptives are safe for women with IBD and frequently used for reproductive planning, but data are lacking on their effect on IBD-related symptoms.

Methods:

We completed a cross-sectional phone survey of 129 women (31% response rate), aged 18 to 45 years, with IBD in an academic practice between March and November 2013. An electronic database query identified eligible women, and we sent an opt-out letter before contact. Questions included demographics, medical and reproductive history, and current/previous contraceptive use. Women were asked if/how their menses affected IBD-related symptoms and if/how their contraceptive affected symptoms. We calculated descriptive statistics and made comparisons by Crohn’s disease versus ulcerative colitis on Stata V11.

Results:

Participants were predominately white (85%) and college educated (97%), with a mean age of 34.2 (SD 6.2, range 19–45) years. Sixty percent had Crohn’s disease, and 30% had IBD-related surgery previously. Half of the participants were parous, and 57% desired future pregnancy. Of the participants, 88% reported current or past hormonal contraceptive use and 60% noted cyclical IBD symptoms. Symptomatic improvement in cyclical IBD symptoms was reported by 19% of estrogen-based contraceptive users and 47% of levonorgestrel intrauterine device users. Only 5% of all hormonal method users reported symptomatic worsening.

Conclusions:

In a subset of women with IBD, 20% of hormonal contraception users reported improved cyclical menstrual-related IBD symptoms. Health care providers should consider potential noncontraceptive benefits of hormonal contraception in women with cyclical IBD symptoms.

Keywords: menstruation, Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis

The diagnosis of inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) is most common in the second to fourth decades, with the highest incidence between ages 20 and 29 years (prime reproductive years for women).1 No cure for IBD exists; hence management is focused on decreasing symptoms and inducing remission of disease flares. Stress, negative mood, and major life events seem to be associated with disease flares.2 Additionally, women with ulcerative colitis are at risk of disease flares in pregnancy or postpartum period.3 Despite understanding some flare triggers, the unpredictable nature of the disease significantly impacts quality of life and can lead to anxiety, depression, and stress for many patients.4 Current medical management of IBD involves weighing the risks and benefits of chronic immunosuppression or immunomodulation, and few other treatments are available to improve symptoms or quality of life.5

Women with IBD frequently report cyclical menstrual-related IBD symptoms, highlighting a hormonal influence on disease activity.6–10 Patients with Crohn’s disease report increased abdominal pain and extraintestinal symptoms, such as irritability or sleeplessness, in the premenstrual phase.9,10 Both women with Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis describe increased diarrhea and pain during their menses.6 Menstrual cycle irregularity may even occur before IBD diagnosis and correlates with lower quality of life scores.8 The cyclical pattern of IBD symptoms seems to be independent of disease activity8; therefore, disease remission may not improve menstrual alterations or associated quality of life indices. In clinical practice, women report concern regarding menstrual-related symptoms as a possible trigger for a disease flare. Minimizing menstrual-related symptoms could positively impact quality of life and potentially mitigate flare risk.

Hormonal contraceptives are often used for their noncontraceptive benefits to lessen cyclical symptoms in other disorders, such as endometriosis, catamenial seizures, or migraines.11–13 In fact, 14% of birth control pill users, or 1.5 million women, rely on the pill for noncontraceptive benefits and only 42% of women use the pill exclusively for its contraceptive benefit.14 As menstruation, psychological distress, or both could trigger disease flares in women with IBD, hormonal contraception could allay the risk. To our knowledge, no current data exist on the effects of hormonal contraception on cyclical disease-related symptoms in women with IBD. In addition, hormonal contraceptives are safe15 and frequently used by women with IBD for reproductive planning; therefore, an understanding of the potential effect on bowel symptoms would assist reproductive health providers in contraceptive counseling.16,17 The objective of this study was to assess the impact of hormonal contraception methods on cyclical disease-related symptoms in women with IBD.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A query of the Northwestern University Enterprise Data Warehouse identified all women, aged 18 to 45 years, with Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis, who accessed care with the Northwestern Medical Faculty Foundation’s academic gastroenterology practice from 2010 to 2012. A manual chart review confirmed diagnoses and extracted contact information. We mailed potential participants an opt-out letter and then contacted women by phone within 30 days. All potential participants received up to 3 attempts at phone contact between March and November 2013, and verbal consent was obtained to complete the survey.

Phone survey questions collected data on demographics, medical and reproductive history, details regarding disease activity, and current and/or previous contraceptive method use. The questions probed if and how a participant’s menses affected her IBD-related symptoms, which symptoms were affected, and the cycle timing of any of the symptoms. We asked those who reported a current or previous contraceptive method if and how their contraceptive method affected any cyclical disease-related symptoms and reasons for discontinuation of the previous methods. As participants were asked about both current and previous contraceptive method use, those who reported different hormonal methods used previously and currently were independently counted for each exposure.

We documented qualitative responses verbatim and coded reported symptoms and cycle timing numerically. All quantitative and descriptive statistics were calculated and frequencies and proportions were reported. Comparisons were made by disease by using t test, Wilcoxon rank sum test, 2-sample test of proportions, or chi-square test, as appropriate, and data were stored in Microsoft Excel spreadsheets and analyzed with Stata V11 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX).

ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS

The Institutional Review Board of Northwestern University approved this study. All participants accepted a verbal consent, read verbatim from an institutional review board–approved script. All data are deidentified, and risk of breach of confidentiality was minimized with secure data storage.

RESULTS

A total of 420 opt-out letters were mailed and not returned to sender, 50 phone numbers were wrong or disconnected, and 80 women verbally declined participation. One hundred twenty-nine participants (31% response rate) completed the phone survey. The participants were predominately white (85%), with at least some college education (97%), and a mean age of 34.3 (SD 6.9) years. Sixty percent had Crohn’s disease and 40% ulcerative colitis. Participants with Crohn’s disease were more likely to have been hospitalized for their disease (P = 0.01), undergone IBD-related surgery (P = 0.001), or be on biological therapy (P < 0.001), than those with ulcerative colitis. Participants with ulcerative colitis were more likely to use aminosalicylates for medical management of their disease (P < 0.001) (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Participant Sociodemographic, Medical, and Reproductive Characteristics (N = 129)

| All Participants (N = 129) | Ulcerative Colitis (N = 52) | Crohn’s Disease (N = 77) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age (SD, range), yr | 34.3 (6.2, 19–45) | 34.4 (6.2) | 34.2 (6.3) | 0.89 |

| Race | 0.65 | |||

| White | 110 (85.3) | 46 (88.5) | 64 (83.1) | |

| African American | 17 (13.2) | 6 (11.5) | 11 (14.3) | |

| Hispanic ethnicity (any race) | 8 (6.2) | 4 (7.7) | 4 (5.2) | 0.56 |

| Married/committed relationship | 71 (55.1) | 33 (63.5) | 38 (49.4) | 0.11 |

| Education | 0.87 | |||

| High school | 4 (3.1) | 1 (1.9) | 3 (3.9) | |

| Some college/college degree | 81 (55.0) | 26 (50.0) | 45 (58.4) | |

| Graduate/professional | 54 (41.9) | 25 (46.1) | 29 (37.7) | |

| Reproductive history | ||||

| Mean age menarche (SD) | 12.9 (1.7) | 12.9 (1.8) | 12.9 (1.6) | 0.89 |

| Nulliparas | 65 (50.4) | 26 (50.0) | 39 (50.7) | 0.94 |

| Median parity (range) | 0 (0–4) | 0 (0–4) | 0 (0–4) | 0.94 |

| Desirous of future pregnancy | 73 (56.6) | 27 (51.9) | 46 (59.7) | 0.38 |

| Contraceptive method selection | ||||

| Current contraceptive method (all methods) | 88 (68.2) | 34 (65.4) | 54 (70.1) | 0.57 |

| Current hormonal contraceptive method use | 56 (43.4) | 18 (34.6) | 38 (49.5) | 0.09 |

| Previous hormonal contraceptive method use | 69 (53.5) | 28 (53.8) | 41 (53.2) | 0.95 |

| Participants reporting cyclical symptoms: current hormonal contraceptive users (n = 56) | 30 (53.6) | 8/18 (44.4) | 22/38 (57.9) | 0.34 |

| Participants reporting cyclical symptoms: not current hormonal contraceptive users (n = 73) | 47/73 (64.4) | 22/34 (64.7) | 25/39 (64.1) | 0.96 |

| Disease characteristics | ||||

| Median no. of years since diagnosis (range) | 116 (9–338) | 144 (9–298) | 112 (18–338) | 0.67 |

| Previous IBD-related surgery | 38 (29.5) | 7 (13.5) | 31 (40.3) | <0.01 |

| Median no. of IBD-related hospital admissions (range) | 1 (0–100) | 1 (0–25) | 1 (0–100) | 0.01 |

| Current IBD medications | ||||

| Aminosalicylates | 60 (46.5) | 36 (69.2) | 24 (31.2) | <0.01 |

| Immunomodulators | 40 (31.0) | 11 (21.2) | 29 (37.7) | 0.05 |

| Systemic steroids | 9 (7.0) | 4 (7.7) | 5 (6.5) | 0.79 |

| Biological therapies | 45 (34.9) | 7 (13.5) | 38 (49.4) | <0.01 |

Entries in the table represent the number of participants (percentage), unless otherwise specified. IBD medication classes: Aminosalicylates include balsalazide, sulfasalazine, mesalamine, and olsalazine; Immunomodulators include azathioprine, 6-mercaptopurine, and methotrexate; Systemic steroids include budesonide, prednisone, methylprednisolone, and prednisolone; Biological therapies include infliximab, adalimumab, certolizumab, and natalizumab.

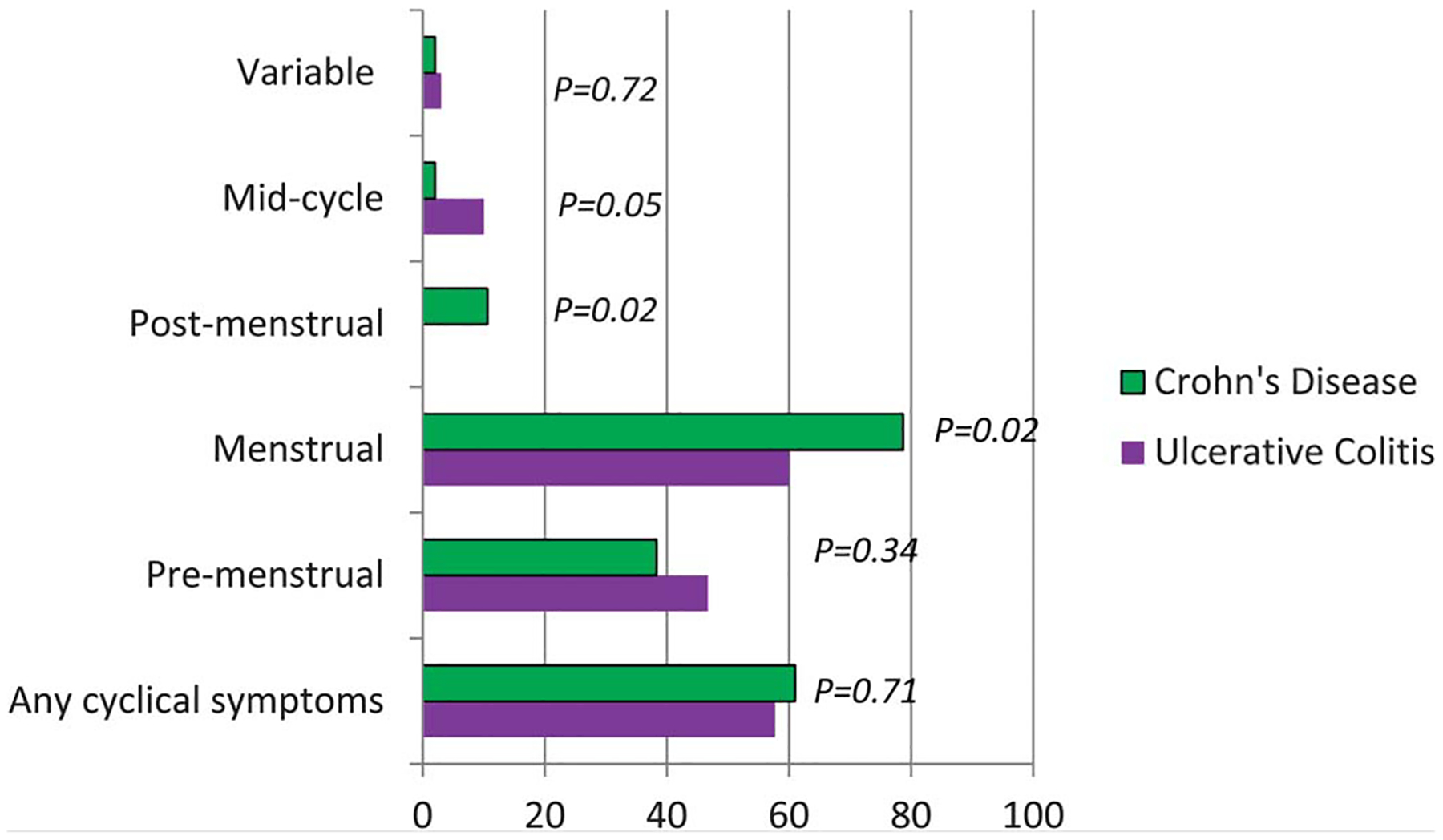

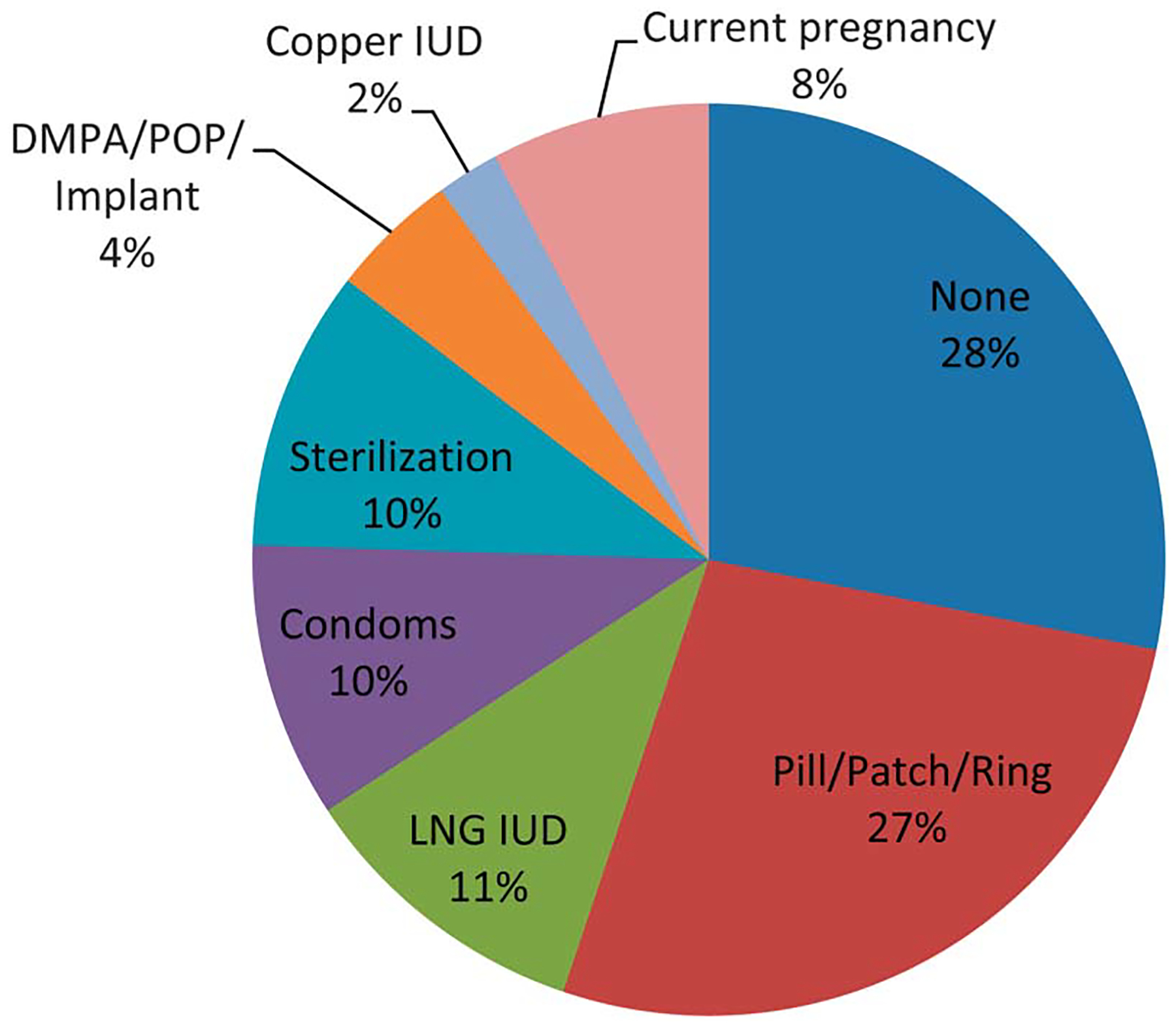

Half of the participants had at least 1 child and 57% desired a future pregnancy (Table 1). Cyclical disease-related symptoms were reported by 60% of the participants, primarily in the premenstrual (42%) or menstrual (72%) phases. Patients with Crohn’s disease were more likely to note disease-related symptoms during (P = 0.02) or after their menses (P = 0.02) than those with ulcerative colitis (Fig. 1). A current contraceptive method was used by 68% of the participants, and 43% used a hormonal method (Fig. 2). Only 12% (16) of the participants had never used a hormonal contraceptive method. There was no significant difference between the proportions of women reporting menstrual effects on IBD-related symptoms who currently used hormonal contraceptive methods compared with those who did not use hormonal methods (54% versus 64%; P = 0.22) or by disease type (Table 1).

FIGURE 1.

Proportion of participants reporting IBD-related cyclical symptoms in each menstrual phase by disease type.

FIGURE 2.

Current contraceptive method selection by study participants (N = 129). DMPA, depot medroxyprogesterone acetate; Implant, etonogestrel subdermal implant; LNG IUD, levonorgestrel intrauterine device; POP, progestin-only pills; P/P/R, combination estrogen and progestin pills, transdermal patch, or vaginal ring; sterilization, male or female.

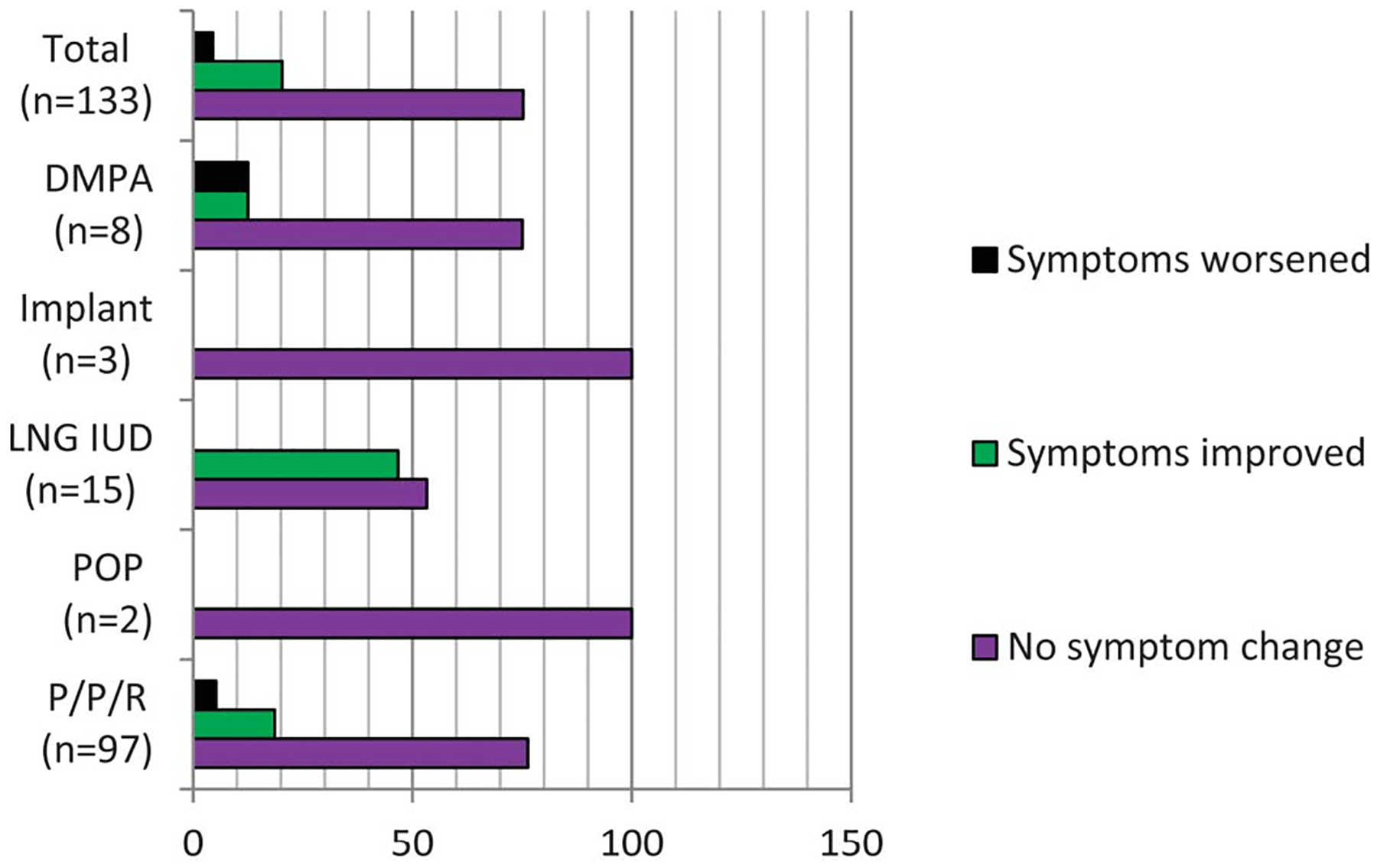

A total of 133 hormonal contraceptive exposures were explored and 20% of the participants reported improved cyclical disease-related symptoms with their hormonal method. Seventy-five percent had no change in their symptoms, and only 5% stopped a method because of IBD-related symptomatic worsening. Of the 97 (73%) women with current or previous combination estrogen-based contraceptive method use, 19% reported IBD-related symptomatic improvement and 76% had no change in symptoms. Forty-seven percent of the levonorgestrel intrauterine device users had symptomatic improvement and the remaining 53% had no change in their symptoms (Fig. 3). The most common symptoms described by the hormonal contraceptive users with cyclical improvement (n = 27) were diarrhea (48%), pain (44%), and cramping (41%) (Table 2).

FIGURE 3.

IBD-related symptoms by type of hormonal contraceptive type in current and past users. Participants reporting different current and previous hormonal methods are counted for each method; therefore, the total n = number of contraceptive method exposures. DMPA, depot medroxyprogesterone acetate; implant, etonogestrel subdermal implant; LNG IUD, levonorgestrel intrauterine device; POP, progestin-only pills; P/P/R, combination estrogen and progestin pills, transdermal patch, or vaginal ring.

TABLE 2.

Proportion of Hormonal Contraception Users with IBD-related Symptom Improvement by Symptom Type (N = 27)

| Diarrhea | 48% |

| Pain | 44% |

| Cramping | 41% |

| Steroid-requiring IBD flares | 11% |

| Nausea/vomiting | 7% |

| Bloating | 11% |

| Extra-GI symptoms | 7% |

| Constipation | 4% |

| Hematochezia | 15% |

GI, gastrointestinal.

DISCUSSION

Women with IBD report cyclical IBD-related symptoms that impact their quality of life and are a potential trigger for disease flares. This is the first study, to our knowledge, to directly explore the effects of hormonal contraception on disease-related cyclical symptoms. In this subset of women with IBD, the majority report either improvement or no significant change in their disease-related symptoms. This finding has several implications as follows: (1) contraception is unlikely to worsen IBD symptoms, (2) for at least a subset of patients with IBD, contraception use might improve symptoms by reducing the impact of menses on intestinal function, and (3) there is justification to study the use of contraception for disease management purposes in future studies.

To optimize and individualize care, clinicians must ask all reproductive age women about cyclical flares and disease triggers. Directing the patient to complete symptom diaries with the addition of bleeding days could improve self-management or alleviate the stress of questioning whether increased symptoms are a flare or normal for the woman’s cycle. Self-management is an important component of the chronic care aspect of IBD and increased awareness of symptoms might allow for other lifestyle modifications, such as stress management or continuous cycling of combination contraceptive methods, to offset known cyclical symptoms.5

Women with IBD need to carefully plan for pregnancy during disease remission to avoid adverse pregnancy outcomes, such as miscarriage or preterm delivery.18–20 Hormonal contraception is important for reproductive planning; yet, a significant proportion of women with IBD at risk for unintended pregnancy do not use any form of contraception.16 The reasons for underuse in this population have not been systematically explored, but concern over the effects of hormonal contraception on disease-related symptoms is reported in clinical practice. Contraceptive counseling should include a thorough discussion of the risks and benefits to improve method satisfaction and adherence.21 This study provides reassuring data for patient counseling that could alleviate fear over the use of hormonal contraception and decrease risk of unintended pregnancy by method adherence.

The limitations of this study include the small sample size and potential recruitment bias. The phone survey required a working consistent number; therefore, the data might not represent the views of those patients without stable phone access due to socioeconomic reasons or those we were unable to contact. The survey was only administered in English and the participants were primarily white and well educated, limiting generalizability to non–English-speaking populations, other ethnic groups, or those with lower education levels. Recall bias is also a potential given women were asked about previous contraceptive methods and symptoms over their entire reproductive lives after their IBD diagnosis. We did not assess IBD activity or control for different IBD treatment at the time of previous contraceptive method use; hence, disease activity could affect some responses. The analysis collapsed all combination method users due to low patch and ring use; variation in symptomatic response by drug delivery system was not assessed.

Despite these limitations, this study provides patient-reported data useful for contraceptive counseling. The data also support the option of hormonal contraceptive method utilization for noncontraceptive benefits, as 1 in 5 participants reported improvement in their cyclical disease-related symptoms. Prospective clinical studies are needed to confirm these findings and elucidate possible pathophysiological mechanisms. Given the limited options for quality of life improvement with the relapsing nature of IBD, hormonal contraception may be an important complementary treatment for cyclical symptoms while providing an effective means of reproductive planning.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors acknowledge the contribution by Suzanne Banuvar and Denise Romero to the phone survey administration and data collection.

Supported by NIH/NICHD Grant K12 HD050121 (PI: Bulun).

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Presented at Digestive Disease Week 2014, Chicago, IL.

REFERENCES

- 1.Molodecky NA, Soon IS, Rabi DM, et al. Increasing incidence and prevalence of the inflammatory bowel diseases with time, based on systematic review. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:46–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bernstein CN, Singh S, Graff LA, et al. A prospective population-based study of triggers of symptomatic flares in IBD. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010; 105:1994–2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pedersen N, Bortoli A, Duricova D, et al. The course of inflammatory bowel disease during pregnancy and postpartum: a prospective European ECCO-EpiCom Study of 209 pregnant women. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;38:501–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Iglesias-Rey M, Barreiro-de Acosta M, Caamano-Isorna F, et al. Psychological factors are associated with changes in the health-related quality of life in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2014;20:92–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Keefer L, Taft TH, Kiebles JL, et al. Gut-directed hypnotherapy significantly augments clinical remission in quiescent ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;38:761–771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kane SV, Sable K, Hanauer SB. The menstrual cycle and its effect on inflammatory bowel disease and irritable bowel syndrome: a prevalence study. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:1867–1872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parlak E, DaÄŸli U, Alkim C, et al. Pattern of gastrointestinal and psychosomatic symptoms across the menstrual cycle in women with inflammatory bowel disease. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2003;14:250–256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saha S, Zhao YQ, Shah SA, et al. Menstrual cycle changes in women with inflammatory bowel disease: a study from the ocean state Crohn’s and colitis area registry. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2014;20:534–540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lim SM, Nam CM, Kim YN, et al. The effect of the menstrual cycle on inflammatory bowel disease: a prospective study. Gut Liver. 2013;7:51–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bernstein MT, Graff LA, Targownik LE, et al. Gastrointestinal symptoms before and during menses in women with IBD. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;36:135–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Calhoun A, Ford S. Elimination of menstrual-related migraine beneficially impacts chronification and medication overuse. Headache. 2008;48:1186–1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Herzog AG. Intermittent progesterone therapy and frequency of complex partial seizures in women with menstrual disorders. Neurology. 1986;36:1607–1610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davis L, Kennedy SS, Moore J, et al. Modern combined oral contraceptives for pain associated with endometriosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;CD001019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jones RK. Beyond birth control: the overlooked benefits of oral contraceptive pills. Guttmacher Institute. November2011. Available at: http://www.guttmacher.org/pubs/Beyond-Birth-Control.pdf.AccessedMay 1, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 15.U.S. medically eligibility criteria for contraceptive use. Centers for Disease Control; 2010. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/pdf/rr/rr5904.pdf.AccessedApril 14, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gawron LM, Gawron AJ, Kasper A, et al. Contraceptive method selection by women with inflammatory bowel diseases: a cross-sectional survey. Contraception. 2014;89:419–425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marri SR, Ahn C, Buchman AL. Voluntary childlessness is increased in women with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2007;13: 591–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Riis L, Vind I, Politi P, et al. Does pregnancy change the disease course? A study in a European cohort of patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1539–1545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fonager K, Sorensen HT, Olsen J, et al. Pregnancy outcome for women with Crohn’s disease: a follow-up study based on linkage between national registries. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:2426–2430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Norgard B, Fonager K, Sorensen HT, et al. Birth outcomes of women with ulcerative colitis: a nationwide Danish cohort study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:3165–3170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fisher WA, Black A. Contraception in Canada: a review of method choices, characteristics, adherence and approaches to counselling. CMAJ. 2007;176:953–961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]