Abstract

Women with pathogenic germline mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes have an increased risk to develop breast and ovarian cancer. There is, however, a high interpersonal variability in the modality and timing of tumor onset in those subjects, thus suggesting a potential role of other individual’s genetic, epigenetic, and environmental risk factors in modulating the penetrance of BRCA mutations. MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are small noncoding RNAs that can modulate the expression of several genes involved in cancer initiation and progression. MiRNAs are dysregulated at all stages of breast cancer and although they are accessible and evaluable, a standardized method for miRNA assessment is needed to ensure comparable data analysis and accuracy of results. The aim of this review was to highlight the role of miRNAs as potential biological markers for BRCA mutation carriers. In particular, biological and clinical implications of a link between lifestyle and nutritional modifiable factors, miRNA expression and germline BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations are discussed with the knowledge of the best available scientific evidence.

Keywords: miRNAs, breast cancer, nutriepigenomics, BRCA1/2 mutations, breast cancer risk

Introduction

Breast cancer (BC) is the most common cancer in women, as the cumulative risk of developing a BC during all life is calculated to be about 1 case every 8 women worldwide (1) (2). BC is also the principal cause of cancer death among women worldwide accounting for 25% of cancer cases and 15% of cancer-related deaths (3).

Hereditary breast cancer accounts for about 5-10% of all breast cancers (BCs) and is associated with an increased risk of ovarian cancer (4, 5).

Hereditary Breast and Ovarian Cancer syndrome (HBOC) is related, in about 50% of cases, to pathogenic germline mutations of BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes (6, 7). BRCA1/2 genes are onco-suppressors involved in homologous recombination repair (HRR) of DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) and maintenance of genome stability (8). Women who inherit BRCA1/2 mutations have a lifetime risk to develop breast and ovarian cancer of 45-60% and 10-59%, respectively (9) (10). In these cases, viable prevention strategies include intensive radiologic surveillance, chemoprevention, and prophylactic surgery of breasts and ovaries (11).

Although breast and ovarian cancer risk increases considerably, not all women with BRCA1/2 mutations develop a neoplasm. There is a high interpersonal variability in the modality and timing of tumor onset in BRCA-mutated subjects, thus suggesting a potential role of other genetics, epigenetics, or environmental individual risk factors in modulating the penetrance of BRCA1/2 germline mutations (12).

Transcribed, non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) do not encode for proteins and have a specific biological function (13). NcRNAs have various transcripts’ lengths: short ncRNAs are <50 nucleotides (nt), as well as microRNAs (miRNAs); midsize ncRNAs include the ncRNAs between 50 nt and 200 nt. Finally, long ncRNAs (lncRNAs) have a length over 200 nt (13–15).

MiRNAs are involved in post-transcriptional, epigenetic modification of DNA expression (16). They are readily detectable in tissue and blood samples (17), saliva (18) or urine (19). While it is difficult to establish cause-and-effect relationships, several studies indicate that some miRNA expression patterns may be associated with: i) increased breast/ovarian cancer risk; ii) some modifiable nutrition/lifestyle risk factors; iii) BRCA1/2 mutations (12, 17). Gene panels, which simultaneously evaluate whole miRNAs, are able to identify different miRNA expression profiles between healthy women, women with sporadic BC and women with BRCA-mutated BC (19, 20).

Based on these considerations, the aim of this review is to highlight the role of miRNAs as potential biomarkers for BRCA mutation carriers. Biological and clinical implications of a link between lifestyle and nutritional modifiable factors, miRNA expression and germline BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations are here discussed with the knowledge of the best available scientific evidence.

Mechanistic Insights of the Interaction of miRNAs With BRCA Genes

MiRNAs are critical regulators of the transcriptome over a number of different biological processes and they may behave as onco-suppressors and onco-promoters (21). MiRNAs can post-transcriptionally suppress gene expression by binding to the 3′-untranslated region (UTR) of messenger RNA (mRNA) (22). However, miRNA interactions with other regions, which include the 5′-UTR, coding sequence, and gene promoters, have also been described (22, 23). Moreover, miRNAs have been shown to trigger gene expression under certain condition (21). Recent studies have demonstrated that miRNAs are transferred between various subcellular compartments to regulate both translation and transcription (21) (22).

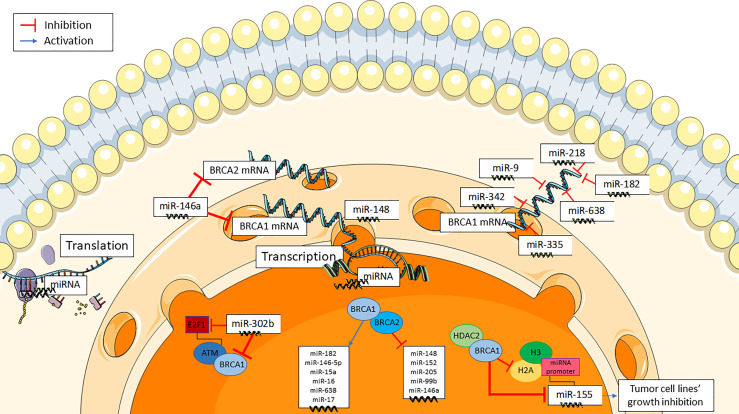

BRCA1/2 gene expression can be altered by miRNAs, in addition to deletion or mutation, in a BRCAness-like phenomenon (Figure 1) (21). E2F1, a G1/S transition regulator, is targeted by miR-302b in breast cancer cell lines. MiR-302b, by negatively regulating E2F1, downregulates ATM, the principal cellular sensor of DNA damage, that phosphorylases and actives BRCA1. As a result, miR-302b indirectly impairs BRCA1 function (23). Furthermore, various studies have evaluated some miRNAs targeting BRCA genes in breast cancer. MiR-146a binds to the 3′-UTRs of BRCA1and BRCA2 mRNAs, thus negatively modulating their expression. Interestingly, the binding capacity of miR-146a seems to be dependent from some of its gene polymorphisms (24). In human tumor xenografts, miR-9 has been found to bind to the 3’-UTR of BRCA1 mRNA, downregulate BRCA1 expression, and enhance cancer cell susceptibility to DNA damage (25). Similar findings have been reported for miR-182 (26), miR-155 (27), miR-342 (28), miR-335 (29), miR-218 and miR-638 (23).

Figure 1.

Mechanistic insights of the interaction of miRNAs with BRCA genes.

BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes also regulate several miRNAs either by upregulating some of them (i.e. miR-146a, miR-146-5p, miR-182, miR-15a, miR-16, miR-17, and miR-638), or by downregulating some others (i.e. miR-155, miR-152, miR-148, miR-205, miR-146a, and miR-99b) (Figure 1) (19). Notably, BRCA1 is involved in the epigenetic control of miR-155, which is a well-known proinflammatory and oncogenic miRNA (27, 30). MiR-155 overexpression stimulates while miR-155 knockdown impairs cancer cell growth. BRCA1 targets the miR-155 promoter, thus suppressing its transcription. More precisely, BRCA1 suppresses miR-155 expression through its association with histone deacetylase 2 (HDAC2), which deacetylates histones H2A and H3 on the miR-155 promoter (27). Some moderate-risk BRCA1 variants (e.g. R1699Q) do not affect DNA repair but abrogate the inhibition of microRNA-155 (27).

Role of miRNAs in Different Breast Cancer Subtypes

Breast cancers are usually grouped into surrogate intrinsic subtypes, defined by routine histology and immunohistochemistry (IHC): luminal A-like tumors are generally low grade, strongly estrogen receptor (ER)/progesterone receptor (PR)-positive, human epidermal growth factor receptor (HER2)-negative and have low proliferation rate. Luminal B-like tumors are ER-positive with variable degrees of ER/PR expression, are higher grade and have higher proliferation rate. HER2-positive tumors are usually high grade, frequently ER/PR-negative, and have high proliferative rate. Triple-negative breast cancers (TNBCs) are high grade, ER/PR-negative, HER2-negative, and have high proliferation rate (1) (2) (3). The expression of numerous miRNAs correlates with different BC subtypes and different prognosis (Table 1).

Table 1.

miRNAs as diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers in breast cancer.

| miRNA role/function | Identified miRNAs | miRNA detection tissue | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overexpressed in Luminal-like BC | miR-29; miR-181a; miR-652; miR-342 | Serum | (31) |

| miR-100; miR-155; miR-126; miR10a; let-7c; let-7f; miR-217; miR-218; miR-377; miR-520f-520c; miR-18a | Tumor tissue | (32–34) | |

| Overexpressed in HER2-positive BC | miR-21; miR-376b | Serum | (35, 34) |

| Overexpressed in TNBC | miR-210; miR-146a; miR-146b-5p; miR-10b; miR-18a; miR-135b; miR-93v; miR-299-3p; miR-190; miR-135b; miR-520g; miR-527-518a | Tumor tissue | (34, 36–38) |

| Overexpression associated with endocrine sensitivity | miR-27a; miR-100; miR-375; miR-342; miR-221/222; let-7f | Tumor tissue | (32, 34) |

| Overexpression associated with better survival | miR-497; miR10a; miR-126; Let-7b; miR-147b; miR-6715a; miR-324-5p; miR-711; miR-375 | Tumor tissue | (32–34, 39–41) |

| miR-1258 | Tumor tissue/serum | (42) | |

| miR-92a | Plasma/serum | (43) | |

| Overexpression associated with worse survival | miR-21 | Tumor tissue/serum | (29, 43) |

| miR-210; miR-205; miR-374a; miR-10b; miR-549a; miR-4501; miR-7974; miR-4675; miR-9; miR-18b; miR-103; miR-107; miR-652; miR-27b-3p | Tumor tissue | (32, 36, 38) (42–44) | |

| Overexpressed in BC compared to HC | miR-1; miR-133a; miR-133b; miR-92a; miR-21; miR-16; miR-27; miR-150; miR-191; miR-200c; miR-210; miR-451; miR-155; miR-195; Let-7b; miR-106b; miR-145; miR-425-5p; miR-139-5p; miR-130a; miR-34a | Tumor/normal tissue/serum | (41–43, 45–50) |

| miR-1246; miR-1307-3p; miR-4634; miR-6861-5p; miR-6875-5p; miR-1246; miR-146a; miR-18a | Plasma/serum | (34, 43, 47, 51) | |

| Underexpressed in BC compared to HC | miR-145 | Tumor/normal tissue/serum | (41) |

| miR-30a | Plasma | (52) | |

| miR-140-5p; miR-497; miR-199a; miR-484; miR-202; miR-181a (Nassar) | Tumor/normal tissue | (36, 41, 53) |

miRNA, microRNA; BC, breast cancer; TNBC, triple negative breast cancer; pts, patients; HC, healthy controls.

Some highly expressed miRNA clusters have been associated with Luminal A-like and Luminal B-like tumors (31, 32). Interestingly, overexpression of miR-100 in basal-like breast cancer cells leads to stemness loss, expression of luminal markers and sensitivity to endocrine therapy (54). Baseline tumor expression of miR-100 has been associated with response to endocrine treatment in patients with ER-positive/HER2-negative breast cancer. In the METABRIC dataset, high expression of miR-100 was observed in luminal A breast cancers with better overall survival (54).

MiR-21 overexpression has been observed in HER2-positive breast cancers, probably because the corresponding gene is located on chromosome 17 and, thus, co-amplifies with HER2 (35, 55). MiR-21 is also an independent prognostic factor associated with early disease relapse and worse disease-free interval (DFI) (56). Furthermore, low miR-497 expression has been observed to be strictly correlated with HER2-positive status and advanced clinical stage (39). In a retrospective case series of tumor tissues and correspondent normal breast tissues, patients with low miR-497 expression had worse 5-year disease-free survival (DFS) and overall survival (OS) than the ones with high miR-497 (39).

Approximately 10-15% of breast tumors are known to be of the TNBC subtype, which is considered to have an aggressive clinical history and shorter survival (20, 31, 57, 58). Up to 29% of TNBC patients harbors somatic mutations or epigenetic downregulation of BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes (59). Differential miRNA expression could help predict prognosis in patients with TNBC (36, 37). Accordingly, miR-210 is often up-regulated in TNBC tissues and correlates with unfavorable prognosis (38). High levels of miR-146a and miR-146b-5p have also been described in triple negative tumor samples (60). MiR-155 is commonly down-regulated in TNBC, indeed its overexpression is related with good prognosis (61). Interestingly, some miRNAs may play different prognostic roles depending by molecular subtypes: miR-27 is associated with better OS in ER-positive BC patients, while its upregulation is detrimental in ER-negative ones (44).

Several other miRNAs have been shown to influence the prognosis of BC patients (Table 1). The deregulation of 5 metastasis-related miRNAs (miR-21, miR-205, miR-10b, miR-210, and let-7a) observed in a series of 84 primary breast tumors significantly correlated with clinical outcome (32, 62). In a sample of 81 postmenopausal, ER-positive BC patients, a higher tumor expression of miR-126 and miR-10a was associated with longer relapse-free survival (RFS) (33). The expression of let-7b in tumor tissues of 80 breast cancer patients was inversely associated with lymph node involvement, OS and RFS (40). MiR-374a expression was significantly elevated in the primary tumors of 33 patients with metastatic disease in comparison with that observed in primary tumors of 133 patients with no evidence of distant metastasis (63). Decreased levels of miR-92a and increased tumor levels of miR-21 were associated with higher tumor stage and presence of lymph node metastases (43). According to other reports, the downregulation of miR-1258 was associated with positive lymph node involvement, later clinical stage, and poor prognosis (42).

Role of MiRNAs in Breast Cancer Risk and Detection

Several studies focused on identifying either individual or groups of miRNAs to be used for prediction of BC risk and for BC detection (Table 2). The most studied miRNAs were analyzed in plasma/serum and tumor tissues of BC patients in comparison with normal controls (41). However, those studies were conducted in different ethnic groups and used different experimental methodology (43). Some studies detected miRNAs in breast tissues using distinct platforms (real-time quantitative reverse transcription PCR [qRT-PCR], sequencing, microarray) followed by validation in serum/plasma (41, 34). Others produced array panels on plasma samples followed by verification using qRT-PCR (47) or started with qRT-PCR on tissues with subsequent serum qRT-PCR (41). One of the limitations of the previously mentioned platforms is their restriction to known miRNAs. Next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies provide novel approaches for identification of new miRNAs and confirmation of known ones (34).

Table 2.

Diagnostic parameters to evaluate breast cancer diagnostic ability of individual and combined studied miRNAs.

| miRNA | Sensitivity | Specificity (%) | PPV (%) | NPV (%) | DA (%) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| miR-21 | 73 | 81 | 76 | 78 | 77 | (50, 64–67) |

| miR-155 | 78 | 75 | 78 | 75 | 77 | (50, 64–67) |

| miR-23a | 78 | 75 | 88 | 44 | 68 | (50, 64–67) |

| miR-130a | 83 | 78 | 83 | 78 | 81 | (50, 64–67) |

| miR-145 | 78 | 91 | 78 | 91 | 83 | (50, 64–67) |

| miR-425-5p | 70 | 100 | 70 | 100 | 81 | (50, 64–67) |

| miR-139-5p | 76 | 96 | 76 | 95 | 83 | (50, 64–67) |

| miR-451 | 73 | 72 | 73 | 72 | 73 | (50, 64–67) |

| miR-200a | 69 | 62 | NR | NR | 70 | (50, 64–67) |

| miR-200c | 71 | 67 | NR | NR | 74 | (50, 64–67) |

| miR-141 | 68 | 70 | NR | NR | 74 | (50, 64–67) |

| miR-10b | NR | NR | NR | NR | 85 | (50, 64–67) |

| miR-181a | NR | NR | NR | NR | 82 | (50, 64–67) |

| miR-106b | NR | NR | NR | NR | 89 | (50, 64–67) |

| miR-34a | 85 | 70 | 93 | 70 | 81 | (50, 64–67) |

| miR-200b + miR-429 | 77 | 63 | NR | NR | 75 | (50, 64–67) |

| miR-145 + miR-425-5p | 78 | 95 | 78 | 95 | 84 | (50, 64–67) |

| miR-21 + miR-23a | 95 | 66 | 95 | 66 | 82 | (50, 64–67) |

| miR-21 + miR-130a | 88 | 78 | 88 | 78 | 84 | (50, 64–67) |

| miR-21 + miR-23a +miR-130a | 93 | 78 | 93 | 78 | 86 | (50, 64–67) |

| miR-145 + miR-139-5p +miR-130a | 95 | 86 | 95 | 86 | 92 | (50, 64–67) |

| miR-145 +miR-139-5p +miR-130a + miR-425-5p | 97 | 91 | 97 | 90 | 95 | (50, 64–67) |

| miR-1246 + miR-206 + miR-24 + miR-373 | 98 | 96 | NR | NR | 97 | (50, 64–67) |

PPV, positive predictive value; NPV, negative predictive value; DA, diagnostic accuracy; NR, not reported.

In a recent study, miRNAs from paired breast tumors, normal tissue, and serum samples of 32 patients were profiled; serum samples from healthy individuals (n = 22) were also used as controls. Twenty miRNAs including miR-21, miR-10b, and miR-145 were found to be differentially expressed in breast cancers. Only 7 miRNAs were overexpressed in both serum and tumors, thus indicating that miRNAs may be selectively released into the serum. MiR-92a, miR-1, miR-133a, and miR-133b were identified as the most significant diagnostic serum markers (45). A combination of 5 serum miRNAs (miR-1307-3p, miR-1246, miR-6861-5p, miR-4634, and miR-6875-5p) were also found to detect breast cancer patients among healthy controls (53).

MiR-21, one of the most common miRNAs in human cells, has been investigated in different diseases including cardiovascular diseases as well as cancers (46). Studies have demonstrated that miR-21 plays an oncogene function in breast cancer by targeting tumor suppressor genes which include programmed cell death 4 (PDCD4), tropomyosin 1 (TPM1), and phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) (68). The diagnostic role of high plasma levels of both miR-1246 and miR-21 was demonstrated by analyzing the contents of circulating exosomes, which are secretory microvesicles that selectively enclose miRNAs (69). Exosomes were collected from the conditioned media of human BC cell lines, murine plasma of patient-derived xenograft models (PDX), and human plasma samples. MiR-21 and miR-1246 were selectively enriched in human BC exosomes and significantly increased in the plasma of BC patients (69). Other studies have suggested a key role for miR-21 in discriminating healthy individuals from BC patients. Overexpression of circulating miR-21 and miR-146a were significantly higher in plasma samples of BC patients, when compared to controls (51). Serum levels of miR-16, miR-21, miR-155, and miR-195 were observed to be higher in stage I BC patients in comparison with unaffected women (51).

Nine miRNAs (miR-16, miR-21, miR-27a, miR-150, miR-191, miR-200c, miR-210, miR-451 and miR-145) were observed to be deregulated in both plasma and tumor tissues from BC patients (47). A validation cohort study reported that a combination of miR-145 and miR-451 was the best biomarker in discriminating breast cancer from healthy controls and other tumor types (47).

The expression of 10 miRNAs (measured by qRT-PCR) has been evaluated in 48 tissue and 100 serum samples of patients with primary BC and in 20 control samples of healthy women (43). The level of miR-92a was significantly lower, while miR-21 was higher in tissue and serum samples of BC patients in comparison with controls. The same expression levels correlated with tumor size and lymph node-positive status (43).

MiR-30a has also been studied as diagnostic biomarker of breast cancer. The median plasma levels of miRNA-30a were significantly lower in a sample of 100 patients with preoperative breast cancer than in 64 age-matched and disease-free controls (52). MiR-497 and miR-140-5p have been shown to be down-regulated in breast tumor samples compared to noncancerous breast tissues, while let-7b seems to be upregulated in BC specimens compared to benign breast diseases (38, 46, 68). Validation of these data in serum or plasma samples is missing.

Another interesting approach is to use miRNAs to unveil BC patients with lymph node involvement (overcoming the prognostic role of the axillary dissection) or to identify patients with metastatic disease. Levels of circulating miR-1258 decreased (42), while miR-10b and miR-373 levels increased (70) in a series of BC patients with lymph nodes metastasis in comparison with non-metastatic patients (70). Furthermore, tumor tissue expression of miR-140-5p decreased in the sequence from stage I to III breast cancer, and was lower in breast tumors with lymph node involvement in comparison with ones without metastasis (71).

Receiver operating characteristics (ROC) analyses have been conducted to evaluate breast cancer diagnostic ability of miRNAs (50, 64–67). Specificity, sensitivity, positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV), and diagnostic accuracy for the most studied individual and combined miRNAs are reported in Table 2.

Role of MiRNAs in BRCA Mutation Carriers

Breast cancer susceptibility in BRCA1/2 mutation carriers may be related to the aberrant expression of certain miRNA clusters (Table 3) (78). MiR-3665, miR-3960, miR-4417, miR-4498, and let-7 have been observed to be overexpressed in women with BRCA-mutated breast tumors (75). Conversely, the downregulation of miR-200c has been reported in BRCA-mutated, TNBC (74).

Table 3.

miRNAs and germinal BRCA mutations.

| miRNA role/function | Identified miRNAs | miRNA detection tissue | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Upregulated by wild-type BRCA1 | miR-182; miR-146-5p; miR-15a; miR-16; miR-638; miR-17 | Tumor/normal tissue/serum | (19) |

| Downregulated by wild-type BRCA1 | miR-148; miR-152; miR-205; miR-99; miR-146a | Tumor/normal tissue/serum | (19, 72) |

| Combined expressions of miRNAs distinguish between BRCA-mutated and BRCA wild-type BC | miR-142-3p; miR-505; miR-1248; miR-181a-2; miR-25; miR-340 | Tumor/normal tissue | (72) |

| miR-627; miR-99b; miR-539; miR-24; miR-331; miR-663a; miR-362; miR-145 | Tumor/normal tissue | (73) | |

| Downregulated in BRCA-mutated BC | miR-155; let-7a; miR-335 | Tumor tissue | (27, 29, 61) |

| miR-200c | Cell culture | (74) | |

| Overexpressed in BRCA-mutated BC | miR-3665; miR-3960; miR-4417; miR-4498; let-7 | Tumor tissue | (75) |

| Regulate BRCA1 expression in BC | miR-342; miR-182; miR-335; miR-146a, miR-146b-5p; miR-182 | Tumor tissue | (26, 28, 60, 76) |

| Restores HRR and genomic stability in BRCA2-mutated cancers | miR-493-5p | Tumor tissue | (77) |

miRNA, microRNA; BC, breast cancer; HRR, Homologous Recombination Repair.

Some studies have also shown that genetic polymorphisms in the gene codifying for miR-146a were associated with early onset in familial cases of breast and ovarian tumors (24). Different expression patterns of six miRNAs (miR-505*, miR-142-3p, miR-1248, miR-181a-2*, miR-340*, and miR-25*) have been found to distinguish between BRCA-mutated and BRCA wild-type (BRCAwt) breast tumors with an accuracy of 92% (24,72). Similarly, a miRNA expression analysis using NanoString technology was performed on BRCA-mutated and sporadic, BRCAwt breast tumor tissues. Eight miRNAs (miR-539, miR-627, miR-99b, miR-24, miR-663a, miR-331, miR-362, and miR-145) were differentially expressed in hereditary breast cancers (73). Let-7a and miR-335 are tumor suppressor miRNAs that can impair both tumorigenesis and metastasis. Let-7a and miR-335 expression levels were significantly downregulated in cancers of patients with BRCA mutations in comparison with tumors of BRCAwt subjects (29, 76).

BRCA-mutated tumors are in vitro and in vivo sensitive to DNA-damaging agents (such as platinum salts) and to poly-ADP ribose polymerase (PARP) inhibitors (PARPi) (8, 79). Up to 29% of patients with TNBC harbor somatic mutations or epigenetic downregulation of BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes, thus being sensitive to platinum salts and PARPi (79). MiR-146a, miR-146b-5p and miR-182 downregulate BRCA1 protein expression and some reports have shown that different expression of miR-182 in breast cancer cell lines affects their sensitivity to PARPi (26, 60). Furthermore, other studies have reported that the over-expression of miR-493-5p restores genomic stability of BRCA2-mutated/depleted leading to acquired resistance to PARPi/platinum salts (77).

Nutriepigenomics and Breast Cancer Risk

Nutriepigenomics is the study of nutrients and their effects on human health through epigenetic modifications. Numerous studies have suggested that body mass index (BMI), components of food and lifestyle may interfere with miRNA expression, thus affecting tumors’ initiation and progression (72) (29) (Table 4).

Table 4.

miRNAs, body mass index and lifestyle changes.

| miRNA role/function | Identified miRNAs | miRNA detection tissue | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Downregulated in BC of obese patients vs. lean subjects | miR-10b | Tumor/normal tissue | (48) |

| Inversely correlated with BMI in BC survivors | miR-191-5p; miR17- 5p | Serum | (80–82) |

| Directly correlated with BMI in BC survivors | miR-122-5p | (82) | |

| Overexpressed during diet and exercise intervention in BC survivors | miR-191-5p; miR-122-5p; let-7b-5p; miR-24-3p | Serum | (82) |

| Underexpressed during diet and exercise intervention in BC survivors | miR-106b; miR-106b_5p; miR-27a-3p; miR-92a-3p | Serum | (49, 81, 82) |

| Upregulated post lifestyle intervention in responders vs. baseline and vs. nonresponders postintervention. | miR-10a-5p; miR-211-5p; miR-10a-5p | Serum | (81) |

| Regulate the expression and activity of PPARγ and C/EBP proteins involved in tumor carcinogenesis, adipocyte differentiation and obesity | Let-7b; miR-27; miR-143; miR-31 | Tumor/normal tissue | (77, 82–84) |

BC, breast cancer; BMI, body mass index; CRP, C-reactive Protein; IL6, interleukin-6; DFS, disease free survival; OS, overall survival; PPARγ, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma; C/EBP, CCAAT/enhancer-binding family of proteins.

Obesity causes changes in the physiological function of adipose tissue, leading to adipocyte differentiation, insulin resistance, abnormal secretion of adipokines, and altered expression of hormones, growth factors, and inflammatory cytokines. All these factors are involved in the occurrence of several diseases, such as type 2 diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease, and various types of cancers (83). Obesity is one of the major risk factors for breast cancer, especially in post-menopausal women. Recent studies have proposed the association between obesity, cancer and up- or down-regulation of some miRNAs (85).

Obesity has been found to reduce expression of miR-10b in primary tumors compared to normal tissue, thus suggesting that the metabolic state of the organism can alter the molecular composition of a tumor (48, 80, 81, 84). Expression levels of miR-191_5p, miR-122-5p and miR-17_5p, which are involved in tumorigenic processes, have been inversely associated with BMI (82). Levels of miR-191-5p significantly increased during a six-month weight-loss intervention (Lifestyle, Exercise, and Nutrition; LEAN trial) in 100 BC survivors (82). Furthermore, the related family member miR-106b_5p, which is up-regulated in breast cancer patients (49, 81), has been found to significantly decrease in response to exercise intervention and diet (82, 85). The nuclear peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ) plays a critical role in the modulation of cellular differentiation, glucose and lipid homeostasis (84). It has been associated with anti-inflammatory activities, and differentiation of preadipocytes into mature adipocytes together with members of the CCAAT/enhancer-binding family protein (C/EBP) family (82). PPARγ is implicated in the pathology of numerous diseases involving cancer and obesity, and altered expressions of miRNAs, such as let-7, miR-27, and miR-143 have been found to regulate the expression and activity of PPARγ (81). Interestingly, miR-31 has been found to impair both BC cell proliferation and adipogenesis by directly targeting C/EBP proteins (81).

Dietary elements, seem to have a key role in regulating miRNAs (84, 86, 87) (Table 5).

Table 5.

Dietary elements and expression/regulation of miRNAs.

| Elements | On-target effect | Effect on miRNAs | Outcome | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Curcumin (dyferuloylmethane) | Inhibition of Bcl2 protein | Overexpression of miR-15a and miR-16 | Inhibition of anti-apoptotic activity in MCF-7 BC cells | (88) |

| Curcumin (dyferuloylmethane) | Inhibition of MMPs. Reduction of CXCL1/2 protein levels | Overexpression of miR-181b | Reduction of cancer cells invasivity | (89) |

| Curcumin (dyferuloylmethane) | Reduction of Axl, Slug, CD24 and Rho-A protein levels | Overexpression of miR-34a | Inhibition of EMT in MCF-10F and MDA-MB-231 BC cell lines | (90) |

| Genistein | Upregulation of PTEN/FOXO3/AKT axis | Underexpression of miR-155; overexpression of miR-23b | Anti-proliferative and pro-apoptotic effects in Hs578t and MDA_MB-435 BC lines | (91) |

| Rasveratrol | Downregulation of EF1A2 gene expression | Overexpression of miR-663, miR-141, miR-774 and miR-200c | Antiproliferative effect in MCF-7 BC cells; inhibition of CSC phenotype transition | (87, 92) |

| 1,25-D | p53-mediated regulation of PCNA | Overexpression of miR-182 | Reduction of cellular stress | (81) |

| 1,25-D | Erα upregulation | Underexpression of miR-489 | Antiproliferative effect in ER-positive BC cell lines | (93) |

| SCFAs acetate (butyrate, propionate) | Activation of FFARs | Overexpression of miR-31 | Induction of cellular senescence | (81, 86) |

| Omega-3 fatty acids (EPA and DHA) | PTEN-mediated CSF1R inhibition | Underexpression of miR-21 | Anti-proliferative and pro-apoptotic effects in BC cell lines | (86) |

| Indole 3 carbinol | AHR-mediated CD4+ T helper activation | Overepression of miR-212 and miR-132 | Enhancement of anti-cancer immune response | (94, 95) |

Bcl2 protein, B cell lymphoma 2 protein; BC, breast cancer; MMPs, matrix metalloproteinases; EMT, epithelial-mesenchymal transition; PTEN, phosphatases and tensin homolog; FOXO3, forkhead box 3 protein; EF1A2, elongation factor 1A2; CSC, cancer stem-like cell; PCNA, proliferating-cell nuclear antigen; 1,25D, 1,25-dihydroxycholecalciferol vitamin D; ERα, estrogen receptor-α; SCFAs, short-chain fatty acids; FFARs, free fatty acid receptors; EPA, eicosapentaenoic acid; DHA, docosahexaenoic acid; CSF1R, colony stimulating factor 1 receptor; AHR, aryl-hydrocarbon receptor.

Polyphenols are a large family of natural compounds widely distributed in plant foods and have been shown to modulate, both in vitro and in vivo, the activity of several enzymes involved in the DNA metabolism (i.e. DNA methyltransferases, and histone deacetylases) (96). In this group, curcumin and curcuminoids have been assiduously studied as anti-inflammatory and anticancer agents (86, 87).

Curcumin (dyferuloylmethane) plays an onco-suppressor role by inhibiting several oncogenic pathways (88). In vitro, curcumin shows an anti-proliferative effect on cancer cell lines even through the modulation of expression of several miRNAs. For example, in vitro, curcumin induces the overexpression of the tumor suppressors miR-15a and miR-16, thus inhibiting some anti-apoptotic proteins (89). In MDA-MB-231 cells, curcumin upregulates miR-181b, interfering with the capacity of invasion and with the inflammation related to chemokines (90). In addition, it reduces the expression levels of genes involved in epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and invasion by controlling miR-34a expression in MCF-10F and MDA-MB-231 lines (91). Despite several studies suggest the anticancer activity of curcumin, its potential use is limited by peculiar pharmacodynamic properties: it has poor absorption, low serum levels, rapid hepatic metabolism, limited tissue distribution and short half-life (96).

Flavonoids (genistein, glabridin, glyceollins) and stilbenes (resveratrol) are polyphenols that affect the epigenetic regulation of genes involved in BC progression and drug-resistance. In TNBC cell lines, such as Hs578t, genistein suppresses miR-155 expression and up-regulates the expression of miR-23b, that has a pro-apoptotic and antiproliferative role (97).

Resveratrol treatment inhibits the proliferation on MCF-7 BC cells by upregulating miR-663, miR-141, miR-774, thus leading to the inhibition of elongation factor 1A2 (EF1A2) (85). In MDA-MB-231 cell lines, resveratrol exhibits strong anti-oxidant activity and induces apoptosis by increasing the levels of tumor-suppressive miRNAs, in particular miR-200c (87, 92).

The active metabolite of the vitamin D (1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3, Calcitriol) binds to the vitamin D receptor (VDR) and influences various signaling pathways involved in cell differentiation, cell cycle arrest and apoptosis (93). Furthermore, it regulates miR-182 expression, leading to protection of breast epithelial cells against cellular stress (81). Calcitriol also reduces the level of miR-489, which is an estrogen regulated miRNA promoting tumor cell growth induced by sexual hormones (98).

Other dietary components modulating miRNA expression in breast cancer cells are fatty acids (FAs) (81, 86) and indole alkaloids such as indole 3-carbinol (94, 95).

Several studies describe the role of physical activity and healthy diet in reducing breast cancer risk, also for subjects carrying BRCA1/2 mutations (94, 99–101). In this context, a nutriepigenetic pilot study is being conducted to evaluate how a personalized nutritional and lifestyle intervention (NLI) can modulate expression of blood and salivary miRNAs associated with breast cancer risk in unaffected young women (<40 years) with BRCA1/2 mutations (19, 102). This study also aims to evaluate whether NLI as primary prevention strategy may help deal with emotional distress occurring in women at high risk for hereditary breast and ovarian cancer who are involved in intensive screening programs.

Conclusions

In this review, we have reported most of the published data evaluating the role of miRNAs in influencing BRCA-related breast cancer risk and diagnosis. Prospective validation of the reported results and standardization of miRNA isolation methods are, however, still awaited before their use in routine clinical practice. Interestingly, numerous preclinical and clinical studies have showed that BRCA1/2 genes may interfere with and be silenced by several miRNAs. Furthermore, emerging evidences suggest the role of nutritional and lifestyle interventions in preventing breast cancer development, even through the modulation of breast cancer-related miRNAs. Prospective clinical trials evaluating the association between penetrance of BRCA mutations, NLI strategies for primary prevention and miRNA signatures are ongoing.

Author Contributions

CT and BP contributed equally to the writing of the manuscript and tables. AM and DB were involved in planning and supervised the study. ASi, MMi, VU, BB, FB, PM, SP, ASq, MV, DC, GM, and MMe reviewed this work. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This study was supported by a research grant from the Lega Italiana per la Lotta contro i Tumori (LILT) – bando di ricerca sanitaria 2017 (cinque per mille anno 2015) and by the Gruppo Oncologico Italiano di Ricerca Clinica (GOIRC).

Author Disclaimer

Any views, opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this material are those solely of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of ESMO or Roche.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

BP was supported by ESMO with a Clinical Translational Fellowship aid supported by Roche.

References

- 1.Paci E, Puliti D. Come Cambia L’epidemiologia Del Tumore Della Mammella in Italia. Osservatorio Nazionale Screening (2011) 1:1–1117. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE, Jemal A. Cancer Statistics, 2021. CA Cancer J Clin (2021) 71:7–33. 10.3322/caac.21654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Torre LA, Islami F, Siegel RL, Ward EM, Jemal A. Global Cancer in Women: Burden and Trends. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev (2017) 26:444–57. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-16-0858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Malone KE, Daling JR, Doody DR, Hsu L, Bernstein L, Coates RJ, et al. Prevalence and Predictors of BRCA1 and BRCA2 Mutations in a Population-Based Study of Breast Cancer in White and Black American Women Ages 35 to 64 Years. Cancer Res (2006) 66:8297–308. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rennert G, Bisland-Naggan S, Barnett-Griness O, Bar-Joseph N, Zhang S, Rennert HS, et al. Clinical Outcomes of Breast Cancer in Carriers of BRCA1 and BRCA2 Mutations. N Engl J Med (2007) 357:115–23. 10.1056/NEJMoa070608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Antoniou A, Pharoah PDP, Narod S, Risch HA, Eyfjord JE, Hopper JL, et al. Average Risks of Breast and Ovarian Cancer Associated With BRCA1 or BRCA2 Mutations Detected in Case Series Unselected for Family History: A Combined Analysis of 22 Studies. Am J Hum Genet (2003) 72:1117–30. 10.1086/375033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen S, Parmigiani G. Meta-Analysis of BRCA1 and BRCA2 Penetrance. J Clin Oncol (2016) 25:1329–33. 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.1066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.O’Connor MJ. Targeting the DNA Damage Response in Cancer. Mol Cell (2015) 60:547–60. 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.10.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kiechle M, Engel C, Berling A, Hebestreit K, Bischoff SC, Dukatz R, et al. Effects of Lifestyle Intervention in BRCA1/2 Mutation Carriers on Nutrition, BMI, and Physical Fitness (LIBRE Study): Study Protocol for a Randomized Controlled Trial. Trials (2016) 17:368. 10.1186/s13063-016-1504-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Castéra L, Krieger S, Rousselin A, Legros A, Baumann J-J, Bruet O, et al. Next-Generation Sequencing for the Diagnosis of Hereditary Breast and Ovarian Cancer Using Genomic Capture Targeting Multiple Candidate Genes. Eur J Hum Genet (2014) 22:1305–13. 10.1038/ejhg.2014.16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kotsopoulos J. BRCA Mutations and Breast Cancer Prevention. Cancers (2018) 10:524. 10.3390/cancers10120524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shen J. Evaluation of Environmental and Personal Susceptibility Characteristics That Modify Genetic Risks. Methods Mol Biol (2009) 471:163–77. 10.1007/978-1-59745-416-2_8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bach D-H, Lee SK, Sood AK. Circular RNAs in Cancer. Mol Ther - Nucleic Acids (2019) 16:118–29. 10.1016/j.omtn.2019.02.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tripathi R, Soni A, Varadwaj PK. Integrated Analysis of Dysregulated LnRNA Expression in Breast Cancer Cell Identified by RNA-Seq Study. Non-coding RNA Res (2016) 1:35–42. 10.1016/j.ncrna.2016.09.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Balsano R, Tommasi C, Garajova I. State of the Art for Metastatic Pancreatic Cancer Treatment: Where are We Now? Anticancer Res (2019) 39:3405–12. 10.21873/anticanres.13484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morales S, Monzo M, Navarro A. Epigenetic Regulation Mechanisms of Microrna Expression. Biomolecular Concepts (2017) 8:203–12. 10.1515/bmc-2017-0024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nassar FJ, Chamandi G, Tfaily MA, Zgheib NK, Nasr R. Peripheral Blood-Based Biopsy for Breast Cancer Risk Prediction and Early Detection. Front Med (2020) 7:28. 10.3389/fmed.2020.00028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Setti G, Pezzi ME, Viani MV, Pertinhez TA, Cassi D, Magnoni C, et al. Salivary MicroRNA for Diagnosis of Cancer and Systemic Diseases: A Systematic Review. Int J Mol Sci (2020) 21:907. 10.3390/ijms21030907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gasparri ML, Casorelli A, Bardhi E, Besharat AR, Savone D, Ruscito I, et al. Beyond Circulating Microrna Biomarkers: Urinary MicroRNAs in Ovarian and Breast Cancer. Tumour Biol (2017) 39:101042831769552. 10.1177/1010428317695525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abdul QA, Yu BP, Chung HY, Jung HA, Choi JS. Epigenetic Modifications of Gene Expression by Lifestyle and Environment. Arch Pharm Res (2017) 40:1219–37. 10.1007/s12272-017-0973-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dhawan A, Scott JG, Harris AL, Buffa FM. Pan-Cancer Characterisation of MicroRNA Across Cancer Hallmarks Reveals MicroRNA-Mediated Downregulation of Tumour Suppressors. Nat Commun (2018) 9:5228. 10.1038/s41467-018-07657-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.O’Brien J, Hayder H, Zayed Y, Peng C. Overview of MicroRNA Biogenesis, Mechanisms of Actions, and Circulation. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) (2018) 9:402. 10.3389/fendo.2018.00402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Plantamura I, Cosentino G, Cataldo A. MicroRNAs and DNA-Damaging Drugs in Breast Cancer: Strength in Numbers. Front Oncol (2018) 8:352. 10.3389/fonc.2018.00352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shen J, Ambrosone CB, DiCioccio RA, Odunsi K, Lele SB, Zhao H. A Functional Polymorphism in the MiR-146a Gene and Age of Familial Breast/Ovarian Cancer Diagnosis. Carcinogenesis (2008) 29:1963–6. 10.1093/carcin/bgn172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sun C, Li N, Yang Z, Zhou B, He Y, Weng D, et al. MiR-9 Regulation of BRCA1 and Ovarian Cancer Sensitivity to Cisplatin and PARP Inhibition. JNCI: J Natl Cancer Institute (2013) 105:1750–8. 10.1093/jnci/djt302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moskwa P, Buffa FM, Pan Y, Panchakshari R, Gottipati P, Muschel RJ, et al. MiR-182-Mediated Downregulation of BRCA1 Impacts DNA Repair and Sensitivity to PARP Inhibitors. Mol Cell (2011) 41:210–20. 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.12.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chang S, Wang R-H, Akagi K, Kim K-A, Martin BK, Cavallone L, et al. Tumor Suppressor BRCA1 Epigenetically Controls Oncogenic MicroRNA-155. Nat Med (2011) 17:1275–82. 10.1038/nm.2459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Crippa E, Lusa L, Cecco LD, Marchesi E, Calin GA, Radice P, et al. Mir-342 Regulates BRCA1 Expression Through Modulation of ID4 in Breast Cancer. PloS One (2014) 9:e87039. 10.1371/journal.pone.0087039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Erturk E, Cecener G, Egeli U, Tunca B, Tezcan G, Gokgoz S, et al. Expression Status of Let-7a and MiR-335 Among Breast Tumors in Patients With and Without Germ-Line BRCA Mutations. Mol Cell Biochem (2014) 395(1-2):77–88. 10.1007/s11010-014-2113-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pasculli B, Barbano R, Fontana A, Biagini T, Di Viesti MP, Rendina M, et al. Hsa-MiR-155-5p Up-Regulation in Breast Cancer and its Relevance for Treatment With Poly[ADP-Ribose] Polymerase 1 (PARP-1) Inhibitors. Front Oncol (2020) 10:1415. 10.3389/fonc.2020.01415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McGuire A, Brown JAL, Kerin MJ. Metastatic Breast Cancer: The Potential of MiRNA for Diagnosis and Treatment Monitoring. Cancer Metastasis Rev (2015) 34:145–55. 10.1007/s10555-015-9551-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lai J, Wang H, Pan Z, Su F. A Novel Six-MicroRNA-Based Model to Improve Prognosis Prediction of Breast Cancer. Aging (Albany NY) (2019) 11(2):649–62. 10.18632/aging.101767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hoppe R, Achinger-Kawecka J, Winter S, Fritz P, Lo W-Y, Schroth W, et al. Increased Expression of MiR-126 and MiR-10a Predict Prolonged Relapse-Free Time of Primary Oestrogen Receptor-Positive Breast Cancer Following Tamoxifen Treatment. Eur J Cancer (2013) 49:3598–608. 10.1016/j.ejca.2013.07.145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.van Schooneveld E, Wildiers H, Vergote I, Vermeulen PB, Dirix LY, Van Laere SJ. Dysregulation of MicroRNAs in Breast Cancer and Their Potential Role as Prognostic and Predictive Biomarkers in Patient Management. Breast Cancer Res (2015) 18:17. 10.1186/s13058-015-0526-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu Y, Xu J, Choi HH, Han C, Fang Y, Li Y, et al. Targeting 17q23 Amplicon to Overcome the Resistance to Anti-HER2 Therapy in HER2+ Breast Cancer. Nat Commun (2018) 9(1):4718. 10.1038/s41467-018-07264-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sabit H, Cevik E, Tombuloglu H, Abdel-Ghany S, Tombuloglu G, Esteller M. Triple Negative Breast Cancer in the Era of MiRNA. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol (2020) 157:103196. 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2020.103196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sorlie T, Tibshirani R, Parker J, Hastie T, Marron JS, Nobel A, et al. Repeated Observation of Breast Tumor Subtypes in Independent Gene Expression Data Sets. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA (2003) 100:8418–23. 10.1073/pnas.0932692100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lü L, Mao X, Shi P, He B, Xu K, Zhang S, et al. MicroRNAs in the Prognosis of Triple-Negative Breast Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Med (Baltimore) (2017) 96(22):e7085. 10.1097/MD.0000000000007085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang S, Li H, Wang J, Wang D. Expression of MicroRNA-497 and its Prognostic Significance in Human Breast Cancer. Diagn Pathol (2013) 8:172. 10.1186/1746-1596-8-172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 40.Ma L, Li G-Z, Wu Z-S, Meng G. Prognostic Significance of Let-7b Expression in Breast Cancer and Correlation to its Target Gene of BSG Expression. Med Oncol (2014) 31:773. 10.1007/s12032-013-0773-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nassar FJ, Nasr R, Talhouk R. MicroRNAs as Biomarkers for Early Breast Cancer Diagnosis, Prognosis and Therapy Prediction. Pharmacol Ther (2017) 172:34–49. 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2016.11.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tang D, Zhang Q, Zhao S, Wang J, Lu K, Song Y, et al. The Expression and Clinical Significance of MicroRNA-1258 and Heparanase in Human Breast Cancer. Clin Biochem (2013) 46:926–32. 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2013.01.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Si H, Sun X, Chen Y, Cao Y, Chen S, Wang H, et al. Circulating MicroRNA-92a and MicroRNA-21 as Novel Minimally Invasive Biomarkers for Primary Breast Cancer. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol (2013) 139:223–9. 10.1007/s00432-012-1315-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ljepoja B, García-Roman J, Sommer A-K, Wagner E, Roidl A. MiRNA-27a Sensitizes Breast Cancer Cells to Treatment With Selective Estrogen Receptor Modulators. Breast (2019) 43:31–8. 10.1016/j.breast.2018.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chan M, Liaw CS, Ji SM, Tan HH, Wong CY, Thike AA, et al. Identification of Circulating MicroRNA Signatures for Breast Cancer Detection. Clin Cancer Res (2013) 19:4477–87. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-3401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Grimaldi AM, Incoronato M. Clinical Translatability of “Identified” Circulating MiRNAs for Diagnosing Breast Cancer: Overview and Update. Cancers (2019) 11:901. 10.3390/cancers11070901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ng EKO, Li R, Shin VY, Jin HC, Leung CPH, Ma ESK, et al. Circulating MicroRNAs as Specific Biomarkers for Breast Cancer Detection. PloS One (2013) 8:e53141. 10.1371/journal.pone.0053141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Meerson A, Eliraz Y, Yehuda H, Knight B, Crundwell M, Ferguson D, et al. Obesity Impacts the Regulation of MiR-10b and Its Targets in Primary Breast Tumors. BMC Cancer (2019) 19:86. 10.1186/s12885-019-5300-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zheng R, Pan L, Gao J, Ye X, Chen L, Zhang X, et al. Prognostic Value of MiR-106b Expression in Breast Cancer Patients. J Surg Res (2015) 195(1):158–65. 10.1016/j.jss.2014.12.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Itani MM, Nassar FJ, Tfayli AH, Talhouk RS, Chamandi GK, Itani ARS, et al. A Signature of Four Circulating MicroRNAs as Potential Biomarkers for Diagnosing Early-Stage Breast Cancer. Int J Mol Sci (2021) 11:6121. 10.3390/ijms22116121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kumar S, Keerthana R, Pazhanimuthu A, Perumal P. Overexpression of Circulating MiRNA-21 and MiRNA-146a in Plasma Samples of Breast Cancer Patients. Indian J Biochem Biophys (2013) 50:210–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zeng R, Zhang W, Yan X, Ye Z, Chen E, Huang D, et al. Down-Regulation of MiRNA-30a in Human Plasma is a Novel Marker for Breast Cancer. Med Oncol (2013) 30:477. 10.1007/s12032-013-0477-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shimomura A, Shiino S, Kawauchi J, Takizawa S, Sakamoto H, Matsuzaki J, et al. Novel Combination of Serum MicroRNA for Detecting Breast Cancer in the Early Stage. Cancer Sci (2016) 107:326–34. 10.1111/cas.12880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Petrelli A, Bellomo SE, Sarotto I, Kubatzki F, Sgandurra P, Maggiorotto F, et al. MiR-100 is a Predictor of Endocrine Responsiveness and Prognosis in Patients With Operable Luminal Breast Cancer. ESMO Open (2020) 5. 10.1136/esmoopen-2020-000937 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang SE, Lin RJ. MicroRNA and HER2-Overexpressing Cancer. Microrna (2013) 2(2):137–47. 10.2174/22115366113029990011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Markou A, Yousef GM, Stathopoulos E, Georgoulias V, Lianidou E. Prognostic Significance of Metastasis-Related MicroRNAs in Early Breast Cancer Patients With a Long Follow-Up. Clin Chem (2014) 60:197–205. 10.1373/clinchem.2013.210542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dawood S. Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Drugs (2010) 70:2247–58. 10.2165/11538150-000000000-00000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dawson SJ, Provenzano E, Caldas C. Triple Negative Breast Cancers: Clinical and Prognostic Implications. Eur J Cancer (2009) 45:27–40. 10.1016/S0959-8049(09)70013-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wu J, Mamidi TKK, Zhang L, Hicks C. Integrating Germline and Somatic Mutation Information for the Discovery of Biomarkers in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Int J Environ Res Public Health (2019) 16:1055. 10.3390/ijerph16061055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Garcia AI, Buisson M, Bertrand P, Rimokh R, Rouleau E, Lopez BS, et al. Down-Regulation of BRCA1 Expression by MiR-146a and MiR-146b-5p in Triple Negative Sporadic Breast Cancers. EMBO Mol Med (2011) 3:279–90. 10.1002/emmm.201100136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Piasecka D, Braun M, Kordek R, Sadej R, Romanska H. MicroRNAs in Regulation of Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Progression. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol (2018) 144:1401–11. 10.1007/s00432-018-2689-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Guo C, Fu M, Dilimina Y, Liu S, Guo L. Microrna-10b Expression and its Correlation With Molecular Subtypes of Early Invasive Ductal Carcinoma. Exp Ther Med (2018) 15:2851–9. 10.3892/etm.2018.5797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cai J, Guan H, Fang L, Yang Y, Zhu X, Yuan J, et al. MicroRNA-374a Activates Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling to Promote Breast Cancer Metastasis. J Clin Invest (2013) 123:566–79. 10.1172/JCI65871 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Jang JY, Kim YS, Kang KN, Kim KH, Park YJ. Kim CW Multiple Micrornas as Biomarkers for Early Breast Cancer Diagnosis. Mol Clin Oncol (2021) 14:31. 10.3892/mco.2020.2193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Liu X, Zhang J, Xie B, Li H, Shen J, Chen J. MicroRNA-200 Family Profile. Am J Ther (2016) 23:e388–97. 10.1097/MJT.0000000000000361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yang C, Tabatabaei SN, Ruan X, Hardy P. The Dual Regulatory Role of MiR-181a in Breast Cancer. Cell Physiol Biochem (2017) 44:843–56. 10.1159/000485351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Imani S, Zhang X, Hosseinifard H, Fu S, Fu J. The Diagnostic Role of MicroRNA-34a in Breast Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Oncotarget (2017) 8:23177–87. 10.18632/oncotarget.15520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zhu S, Si M-L, Wu H, Mo Y-Y. MicroRNA-21 Targets the Tumor Suppressor Gene Tropomyosin 1 (TPM1). J Biol Chem (2007) 282:14328–36. 10.1074/jbc.M611393200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hannafon BN, Trigoso YD, Calloway CL, Zhao YD, Lum DH, Welm AL, et al. Plasma Exosome Micrornas are Indicative of Breast Cancer. Breast Cancer Res (2016) 18:90. 10.1186/s13058-016-0753-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Chen W, Cai F, Zhang B, Barekati Z, Zhong XY. The Level of Circulating MiRNA-10b and MiRNA-373 in Detecting Lymph Node Metastasis of Breast Cancer: Potential Biomarkers. Tumor Biol (2013) 34:455–62. 10.1007/s13277-012-0570-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lu Y, Qin T, Li J, Wang L, Zhang Q, Jiang Z, et al. MicroRNA-140-5p Inhibits Invasion and Angiogenesis Through Targeting VEGF-a in Breast Cancer. Cancer Gene Ther (2017) 24:386–92. 10.1038/cgt.2017.30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Tanic M, Yanowski K, Gómez-López G, Rodriguez-Pinilla MS, Marquez-Rodas I, Osorio A, et al. MicroRNA Expression Signatures for the Prediction of BRCA1/2 Mutation-Associated Hereditary Breast Cancer in Paraffin-Embedded Formalin-Fixed Breast Tumors. Int J Cancer (2015) 136:593–602. 10.1002/ijc.29021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Pessôa-Pereira D, Evangelista AF, Causin RL, da Costa Vieira RA, Abrahão-Machado LF, Santana IVV, et al. MiRNA Expression Profiling of Hereditary Breast Tumors From BRCA1- and BRCA2-Germline Mutation Carriers in Brazil. BMC Cancer (2020) 20:143. 10.1186/s12885-020-6640-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Erturk E, Cecener G, Tezcan G, Egeli U, Tunca B, Gokgoz S, et al. BRCA Mutations Cause Reduction in MiR-200c Expression in Triple Negative Breast Cancer. Gene (2015) 556(2):163–9. 10.1016/j.gene.2014.11.047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Murria Estal R, Palanca Suela S, de Juan Jiménez I, Egoavil Rojas C, García-Casado Z, Juan Fita MJ, et al. MicroRNA Signatures in Hereditary Breast Cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat (2013) 142:19–30. 10.1007/s10549-013-2723-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Heyn H, Engelmann M, Schreek S, Ahrens P, Lehmann U, Kreipe H, et al. MicroRNA MiR-335 is Crucial for the BRCA1 Regulatory Cascade in Breast Cancer Development. Int J Cancer (2011) 129:2797–806. 10.1002/ijc.25962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Meghani K, Fuchs W, Detappe A, Drané P, Gogola E, Rottenberg S, et al. Multifaceted Impact of MicroRNA 493-5p on Genome-Stabilizing Pathways Induces Platinum and PARP Inhibitor Resistance in BRCA2-Mutated Carcinomas. Cell Rep (2018) 23:100–11. 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.03.038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kurozumi S, Yamaguchi Y, Kurosumi M, Ohira M, Matsumoto H, Horiguchi J. Recent Trends in MicroRNA Research Into Breast Cancer With Particular Focus on the Associations Between Micrornas and Intrinsic Subtypes. J Hum Genet (2017) 62:15–24. 10.1038/jhg.2016.89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Loibl S, Weber KE, Timms KM, Elkin EP, Hahnen E, Fasching PA, et al. Survival Analysis of Carboplatin Added to an Anthracycline/Taxane-Based Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy and HRD Score as Predictor of Response—Final Results From Geparsixto. Ann Oncol (2018) 29:2341–7. 10.1093/annonc/mdy460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Chan DSM, Vieira AR, Aune D, Bandera EV, Greenwood DC, McTiernan A, et al. Body Mass Index and Survival in Women With Breast Cancer—Systematic Literature Review and Meta-Analysis of 82 Follow-Up Studies. Ann Oncol (2014) 25:1901–14. 10.1093/annonc/mdu042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kasiappan R, Rajarajan D. Role of MicroRNA Regulation in Obesity-Associated Breast Cancer: Nutritional Perspectives. Adv Nutr (2017) 8:868–88. 10.3945/an.117.015800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Adams BD, Arem H, Hubal MJ, Cartmel B, Li F, Harrigan M, et al. Exercise and Weight Loss Interventions and Mirna Expression in Women With Breast Cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat (2018) 170:55–67. 10.1007/s10549-018-4738-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Chen J, Xu X. 8 - Diet, Epigenetic, and Cancer Prevention. In: Herceg Z, Ushijima T, editors. Advances in Genetics Epigenetics and Cancer, Part B. New York: Academic Press. (2010) p. 237–55. 10.1016/B978-0-12-380864-6.00008-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Villapol S. Roles of Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor Gamma on Brain and Peripheral Inflammation. Cell Mol Neurobiol (2018) 38:121–32. 10.1007/s10571-017-0554-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Palmer JD, Soule BP, Simone BA, Zaorsky NG, Jin L, Simone NL. MicroRNA Expression Altered by Diet: Can Food be Medicinal? Ageing Res Rev (2014) 17:16–24. 10.1016/j.arr.2014.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Krakowsky RHE, Tollefsbol TO. Impact of Nutrition on non-Coding RNA Epigenetics in Breast and Gynecological Cancer. Front Nutr (2015) 2:16. 10.3389/fnut.2015.00016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Biersack B. Current State of Phenolic and Terpenoidal Dietary Factors and Natural Products as non-Coding RNA/MicroRNA Modulators for Improved Cancer Therapy and Prevention. Non-Coding RNA Res (2016) 1:12–34. 10.1016/j.ncrna.2016.07.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Sun M, Estrov Z, Ji Y, Coombes KR, Harris DH, Kurzrock R. Curcumin (Diferuloylmethane) Alters the Expression Profiles of MicroRNAs in Human Pancreatic Cancer Cells. Mol Cancer Ther (2008) 7:464–73. 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-07-2272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Yang J, Cao Y, Sun J, Zhang Y. Curcumin Reduces the Expression of Bcl-2 by Upregulating MiR-15a and MiR-16 in MCF-7 Cells. Med Oncol (2010) 27:1114–8. 10.1007/s12032-009-9344-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kronski E, Fiori ME, Barbieri O, Astigiano S, Mirisola V, Killian PH, et al. MiR181b Is Induced by the Chemopreventive Polyphenol Curcumin and Inhibits Breast Cancer Metastasis via Down-Regulation of the Inflammatory Cytokines CXCL1 and -2. Mol Oncol (2014) 8:581–95. 10.1016/j.molonc.2014.01.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Gallardo M, Kemmerling U, Aguayo F, Bleak TC, Muñoz JP, Calaf GM. Curcumin Rescues Breast Cells From Epithelial−Mesenchymal Transition and Invasion Induced by Anti−MiR−34a. Int J Oncol (2020) 56:480–93. 10.3892/ijo.2019.4939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Hagiwara K, Kosaka N, Yoshioka Y, Takahashi R-U, Takeshita F, Ochiya T. Stilbene Derivatives Promote Ago2-Dependent Tumour-Suppressive MicroRNA Activity. Sci Rep (2012) 2:314. 10.1038/srep00314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Umar M, Sastry KS, Chouchane AI. Role of Vitamin D Beyond the Skeletal Function: A Review of the Molecular and Clinical Studies. Int J Mol Sci (2018) 19:1618. 10.3390/ijms19061618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Biersack B. Non-Coding RNA/MicroRNA-Modulatory Dietary Factors and Natural Products for Improved Cancer Therapy and Prevention: Alkaloids, Organosulfur Compounds, Aliphatic Carboxylic Acids and Water-Soluble Vitamins. Noncoding RNA Res (2016) 1:51–63. 10.1016/j.ncrna.2016.09.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Nakahama T, Hanieh H, Nguyen NT, Chinen I, Ripley B, Millrine D, et al. Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor-Mediated Induction of the Microrna-132/212 Cluster Promotes Interleukin-17-Producing T-Helper Cell Differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA (2013) 110:11964–9. 10.1073/pnas.1311087110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Alegría-Torres JA, Baccarelli A, Bollati V. Epigenetics and Lifestyle. Epigenomics (2011) 3:267–77. 10.2217/epi.11.22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.de la Parra C, Castillo-Pichardo L, Cruz-Collazo A, Cubano L, Redis R, Calin GA, et al. Soy Isoflavone Genistein-Mediated Downregulation of MiR-155 Contributes to the Anticancer Effects of Genistein. Nutr Cancer (2016) 68:154–64. 10.1080/01635581.2016.1115104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Kasiappan R, Sun Y, Lungchukiet P, Quarni W, Zhang X, Bai W. Vitamin D Suppresses Leptin Stimulation of Cancer Growth Through MicroRNA. Cancer Res (2014) 74:6194–204. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-1702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Kotsopoulos J, Narod SA. Brief Report: Towards a Dietary Prevention of Hereditary Breast Cancer. Cancer Causes Control (2005) 16:125–38. 10.1007/s10552-004-2593-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Pettapiece-Phillips R, Narod SA, Kotsopoulos J. The Role of Body Size and Physical Activity on the Risk of Breast Cancer in BRCA Mutation Carriers. Cancer Causes Control (2015) 26:333–44. 10.1007/s10552-014-0521-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Nkondjock A, Robidoux A, Paredes Y, Narod SA, Ghadirian P. Diet, Lifestyle and BRCA-Related Breast Cancer Risk Among French-Canadians. Breast Cancer Res Treat (2006) 98:285–94. 10.1007/s10549-006-9161-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Available at: https://www.lilt.it/sites/default/files/allegati/articoli/2019-02/elenco_progetti_finanziati_2017.pdf.