Abstract

Starting with Freud and Jung, dreams have always been considered a core source of information for psychoanalysis. Nowadays, neuroscientific findings suggest that dreams are related especially to limbic and right emotional brain circuit, and that during REM stages they engage self-related and visual internally generated processing. These neuroscientific findings together with contemporary psychoanalysis suggest that dreams are related to the sense of self and serve the purpose of re-integrating and re-structuring the integrity of the psyche. However, while dreams are still viewed as ‘the via regia to the unconscious’, it is the unconscious that has been reconsidered. The repressed unconscious seems to be related with left brain activity while the unrepressed unconscious based on dissociation seems to be associated with limbic and cortical areas of the right hemisphere. This notion of the unconscious might be seen as an implicit self-system encoded in the right brain that evolves in the interaction with a primary caregiver developing through preverbal and bodily stages of maturation enhanced by signals of dual communication. What kind of dreams for which unconscious? What are the differences regarding the capacity to dream for neurotic and borderline personality organizations? Our research aims to integrate psychodynamics, infant research, and neuroscientific findings to better understand the role of dreams in the assessment and treatment of, especially, traumatized and borderline patients. The capacity to dream is here proposed as a sort of enacted manifestation of emotional memories for the development of a more cohesive, coherent and symbolic vs fragmented, diffuse and alexithymic sense of self.

Key words: Dreams, un-repressed unconscious, dissociation, implicit memory, sense of self

The role of dreams in psychoanalysis and neuroscience and their relationship with the self

In the history of psychoanalysis, starting with Freud, dreams have always been considered the ‘via regia to the unconscious’ (Freud, 1900). Nowadays, dream research and neuroscientific findings give us the opportunity to build a bridge between the different branches of science and substantiate the importance of working through dreams in psychotherapy.

Freud gave an extraordinary value to dreams as a primary way of access to the unconscious, which was considered both as a source of instinctual energy pressing for discharge, and as a container of fantasies and memories banished and then repressed from consciousness. Whereas Freud (1900) was convinced that dreaming served the function of protecting sleep by distorting the unconscious meaning of the dream, Jung (2013/1928-30) saw dreams as a spontaneously produced picture of the current situation of the psyche including unconscious aspects serving also to compensate the attitude of ego consciousness. In ‘Structure and dynamics of psyche’, Jung proposed a different perspective from the Freudian view and considered dreams as a manifestation of the affective complex, which might be considered the architect of dreams and symptoms (Jung, 2014). For Jung dreams attempted to lead the individual towards wholeness through a dialogue between the ego and the self.

The concept of ego and the concept of self have various differences, however, as noted by Strachey (1961, pp 7-8) and Kernberg (1984, pp. 227-8), Freud himself preserved the German Ich - ego - as a mental structure and psychic agency, but also as the personal, subjective, experiential self in all his writing. To put it simply, Strachey and Kernberg propose that Freud never dissociated the ego from the experiencing self. However, in this work we consider the concept of self in a broader sense (including not only the Jungian but especially the contemporary relational psychoanalysis perspective) that embeds and goes beyond the id-ego-superego topology introduced by Freud. Supporting our vantage point, Kohut (1971) defined the self as the feeling of our own ego emphasizing the bodily and affective component related to that.

During the years a series of psychoanalytic models have gradually been changing together with a different conceptualization of dreams. Within the theory of object relations, Fairbairn (1944) stated that ‘dreams are representations of endopsychic situations in which the dreamer has been trapped (points of fixation) and often include some attempts to overcome that situation’ (1978, cited in Padel, p. 133). In self-psychology, Kohut (1977) proposed that when the self is threatened by a state of fragmentation or dissolution, the function of dreams is to heal and reintegrate the self and its intrinsic sense of continuity. This kind of dreams is called ‘self-state dreams’ and it aims to resolve the non-verbal tensions of traumatic states: ‘Dreams of this type depict the dreamer’s fear respect to an uncontrollable increase in tension or his fear of the dissolution of the self. The act of depicting these vicissitudes in the dream constitutes an attempt to control psychological danger by covering indefinite and frightening processes with defined visual images’ (Kohut, 1977, p.107). In this kind of dreams, according to the author, the associations do not lead to latent contents, but provide images that remain at the same level as the manifest content of the dream, serving to focus the patient’s anxiety (Kohut, 1977). About these dreams, Stolorow (1989) pointed out that for Kohut the vivid perceptual images of dreams serve to sustain the integrity of the subjective world threatened of disintegration: ‘vividly reifying the experience of being in danger, dream images bring the state of the self to a focal awareness with a feeling of belief and reality that can only accompany sensory perceptions’ (Stolorow, 1989, p.35). This would allow us to see the distinctive feature of the dream experience, that is, the use of concrete perceptual images with hallucinatory vividness to symbolize abstract thoughts and subjective states, in a different light than Freud. For Stolorow the concrete symbolization of the dream with its hallucinatory vividness is at the service of a vital intent, the understanding of which can illuminate the very need to dream. The fundamental purpose of the concrete symbolization of the dream has to be found in the superordinate need to maintain one’s own organization of experience, which the symbolization of the dream satisfies in two ways: on the one hand, the dream images help to consolidate the particular subjective structures of the dreamer by actualizing them in specific configurations of self and of the other, on the other hand, the vivid images of the dream directly serve to reintegrate and sustain the integrity and stability of the structures of a subjective world threatened of disintegration, as in the case of self-state dreams. Altogether, the development of these psychoanalytic conceptions of dreams seems to be related: i) to the sense of self; ii) to serve the purpose of re-integrating and re-structuring the integrity of the psyche and the self. However, how our psychoanalytic conceptualization of self and dreams relates to neuroscientific findings is still partially unclear.

The neuroscience of self: a nested topographical and neuropsychodynamic model

A recent large-scale fMRI meta-analysis in healthy subjects suggests a multi-layered nested hierarchical model of self (Qin, Wang & Northoff, 2020) including: i) interoceptive self; ii) extero-proprioceptive self; and iii) mental self. The interoceptive self refers to the processing of the body’s inner organs and was investigated trough fMRI task related to interoceptive awareness of the own body. The extero-proprioceptive self-focus on external or proprioceptive bodily inputs and was investigated with fMRI studies focusing on external bodily-related inputs like facial or other proprioceptive inputs. Finally, the mental self was investigated considering all task employing trait adjectives or other self-related stimuli vs non-self. Intriguingly the studies related to the interoceptive self emphasizes the role of bilateral insula, dorsal anterior cingulate cortex, thalamus, and parahippocampus, which are also considered core regions of the salience network (Menon & Uddin, 2010). The extero-proprioceptive selfyielded regions like bilateral insula, interior frontal gryus, premotor cortex, temporo-parietal junction (TPJ), and medial prefrontal cortex (MPFC). These regions share the processing of propioceptive inputs related to the own body, this seems to be closely related to the concept of embodied self’ (Tsakiris, 2017; Gallagher, 2005). Finally, the mental self-related to fMRI studies that yielded DMN cortical midline regions like medial prefrontal cortex and posterior cingulate cortex as well as the regions included in the extero-proprioceptive self, most notably bilateral TPJ, and the interoceptive self, i.e. bilateral insula and thalamus. Together, these findings describe hierarchical model of self (Qin et al., 2020) showing how regions of the interoceptive self were also included in the other layers like extero-proprioceptive and mental self where they were complemented by additional regions extending the topography of the self.

This nested topographical hierarchical model of self might be associated and add more information to the proposed neuropsychodynamic nested model of self (Scalabrini, Mucci & Northoff, 2018) that has been conceptualized as related to the different levels of personality organization as theorized by Kernberg (1975) and reprised by PDM-2 (Lingiardi & McWilliams, 2017). In this context the authors propose a multi-layered model of the self-departing from the building blocks of relational alignment to the different layers of self, named: i) Self-constitution; ii) Self-manifestation; and iii) Self-expansion, which might somehow parallel the: i) interoceptive; ii) extero- proprioceptive; and iii) mental self. As proposed by the authors (Scalabrini, Mucci & Northoff, 2018), relational alignment is considered the prerequisite that gives the framework for the born of the sense of subjectivity that is dependent by the first encounter with the other (in this case the caregiver) that facilitate (or not) the constitution and development of the self, depending form the degree of attunement and synchronization that play a fundamental role in shaping the sense of self, relatedness, the capacity to regulate emotions and to mentalize among the complexity of psychological development (Schore, 2011, 2012; Mucci, 2013, 2018, 2021a, 2021b). Intriguingly this hypothesis is further supported by literature showing how the child development and their growing brain is optimized where provision of parental care is sensitively attuned to the infant’s needs (Atzil, Gao, Fradkin, & Barrett, 2018; Atzil & Barrett, 2017 for a perspective). Atzil and colleagues (2018) propose how in particular the insula and the regulation of interoception and allostatic needs of the child, might play a fundamental role for the development of the self and of a social brain. The emphasis on the interoceptive and allostatic needs of the child further support the hierarchical model of self (Qin et al., 2020) and the importance of the insular cortex as a crossroads for the relation integration between internal and external stimuli (Craig, 2010; Menon & Uddin, 2010). These relational aspects are the prerequisite for the three layers of the self. This results in different neuronally grounded configurations or organizations that, in turn, correspond to different levels of personality organization, such as psychotic (as related to the layer of self-constitution), borderline (as related to the layer of self-manifestation) and neurotic (as related to the layer of self-expansion). Self-constitution it is linked with the ownership of one’s own body, sense of agency and the capacity to distinguish the self from the non-self and the internal from the external (i.e. reality testing). Self-manifestation it is particularly featured by the degree of integration of the self and significant others and by the actual experience and manifestation of the self with the external world. Self-expansion is related to the capacity to self-expand and bind the different information of various aspects of self and other into perception and memory (Sui & Humphrey, 2015).

Taken together here we provide for the first time a parallel between these two models that give us a neuroscientific topographical grounded model of self as linked to different personality organization, which carries major psychodynamic and neuroscientific implications.

Is there a link between different self-level and personality organization with the capacity to dream? How does the first relational encounter shape our access to the dream and the unconscious? These are only some of the questions that we will try to answer in the next sections of our work.

The neuroscience of dreams

Neuroscientifically, dreaming is usually described as a process in which our inner system is engaged in processing information (Dewan, 1970). The so-called inner models are constantly modified in co-occurrence with what is perceived. During the wakening state, the individual has the possibility to react immediately with the environment at the expense of storing information in memory given the limited capacity of the system itself. On the contrary, sleeping state and dreaming seems to play a key role in processing information ‘off-line’ and enabling integration into long-term memory (Stickgold & Walker, 2007). Dreams might be seen as an expression of emotional self-state and are usually associated with unconscious memories that can be traced back to early childhood and attachment-related experiences and have been stored implicitly in memory without access to the actual consciousness. The close link between affective states and dreams is further supported by the knowledge that dreams have been related to the seeking systems that drives emotion and behaviour (see Panksepp & Biven, 2012; Solms, 2020).

Lately, the role of dreams in unconscious learning and in memory consolidation and re-consolidation has been emphasized (Stickgold, Hobson, Fosse, & Fosse, 2001). Dreams might be conceived as self-states that are usually accompanied by reactivation of old memories and might also lead to the new associations among pre-existing memories (Nalbantian, 2011), resulting in new insight experiences. This process parallels the proposed concept of ‘embodied memories’ proposed by Leuzinger-Bohleber (2018). Intriguingly psychoanalysts and researchers Moser and von Zeppelin (1996) consider dreams as a manifestation that searches for solutions or the best possible adaptations for the underlining conflict.

Moreover, dreams seem to represent a kind of bizarre expression of affects, emotions, images, and cognition that link the deep unconscious with consciousness. Intriguingly, following Panksepp primary emotion descriptions (Panksepp & Biven, 2012; Solms, 2020), affects and dream-related contents are characterized by an extreme degree of spontaneity resulting in free-floating and unconstrained features that exclude any form of rationality. Thus, dreams are not only characterized by their degree of bizarreness and incongruities that recently was associated with the cognitive organization during the waking state of abnormal psychiatric conditions like schizophrenia (Scarone et al., 2008), but also by their degree of spontaneity characterizing other forms of self-generated cognition (see, for example, Christoff, Irving, Fox, Spreng, & Andrews-Hanna, 2016).

Dreams are usually associated with rapid eye movement (REM) sleep, but this association is not exclusive. Indeed, dreaming can be associated also with the other stages of NREM-sleep (N1-4), most likely occurring in REM-phase (Siclari et al., 2017; Siclari, Bernardi, Cataldi, & Tononi, 2018). In this regard a recent research (Zilio et al., 2021) investigated different dynamic EEG measurements during REM-sleep. Measuring the intrinsic time scales of the brain related to input processing, they found a global increase in spontaneous brain activity in the REM phase compared to deep sleep phases. This further supports that the sleeping and dreaming state is associated with particular phases of information processing and is consistent with the neurophysiology and neurocognitive state of REM sleep, which paradoxically is similar to that of the neurophysiology and neurocognitive state of wakefulness (e.g., high-frequency, desynchronized, low-amplitude EEG). According to Hobson (2009) REM sleep may constitute a preconscious state that provides a virtual reality model of the world and is connected with a primary consciousness that can be defined as simple awareness including mainly perceptions and emotions (vs secondary consciousness, more related to language, metacogntition and awareness). In this regard, studies of cerebral blood flow and metabolism during REM sleep suggested a relatively reduced activity in regions like the praecuneus, dorsolateral prefrontal, posterior and parietal cortex, with increased activation in subcortical and limbic regions like amygdala, hippocampus and anterior cingulate and orbitofrontal cortex (Dang-Vu, 2012). Dreaming seems to abound in perceptions and emotions, related to primary consciousness, and are self-generated by the brain without external stimulation. Intriguingly, as reported by Zilio (2020) in his work on the relation between consciousness and the world, during sleep and dreaming all stimulus-interaction is suppressed while the rest-stimulus interaction within the body is still present. This suggests that interoception plays the role of exteroception during dreaming (Northoff, 2011; Northoff & Huang, 2017). Indeed, during REM sleep the increased spontaneous brain activity and interoceptive processing shape the rest- interaction in a very similar way to exteroception (Hobson, 2009; Northoff, 2011). Again, this suggests a close relationship between insular cortices and their interoceptive features together with limbic and emotional features. This involvement of limbic structures is further supported by findings that relate bizarreness in dream that is positively associated with volumes of hippocampus and negatively with volume in left amygdala (De Gennaro et al., 2011). The predominance of right brain activation related to dream and fantasies is further supported by a recent study (Benedetti et al., 2015) showing the involvement of right inferior frontal gyrus, right superior temporal gyrus and right middle temporal gyrus when compared to non-imaginative reports conditions. Other studies in REM sleep stages show an increased activation and connectivity in medial temporal regions like the hippocampus, a key hub for encoding and retrieving memory (Burgess, Maguire, & O’Keefe, 2002). This suggests that personal memories are usually recruited or retrieved during dreams. This suggests an involvement of the self-related processing in dreams (Northoff, 2016, 2018). Moreover, other studies that compared REM sleep stages with NREM showed also an increased activity of the visual cortex (Fox, Nijeboer, Solomonova, Domhoff, & Christoff, 2013; Domhoff & Fox, 2015; Fox & Girn, 2018), suggesting an enhanced visual activity during dreams related to the self-generating inputs (rather than external).

Altogether these findings suggest that dreams are: i) related especially to limbic and right emotional brain circuit; ii) that hippocampus, amygdala and memory play an important role in dreams; iii) that dreams engage during REM stages DMN-self related processing at the expense of CEN-external inputs processing; iv) that also visual cortex is increased during REM suggesting internallygenerating visual processing or a kind of ‘embodied simulation’ (Northoff, 2011). Accordingly, Efrat Ginot (2015) suggests that dreams arise from the deep unconscious, finding their path into meaning and consciousness and, furthermore, might be considered as enacted manifestations of unconscious emotional memories and self-system. However, the unconscious suggested here does not seem the same theorized by Freud located in the explicit autobiographical memory but, cogently, seems to be more related to the unrepressed unconscious and implicit memory (Craparo & Mucci, 2018; Mucci, 2017). However what unconscious for what kind of dream is still unclear.

Un-repressed vs repressed unconscious. The implicit memory system and the development of the self

Sigmund Freud was the first author to use the construct of repressed unconscious in relation to the emotional world, in both ‘The Interpretation of Dreams’ (1900) and ‘The unconscious’ (1915). On the relationship between the repressed and the unconscious, he maintained that ‘the Ucs. does not coincide with the repressed; it is still true that all that is repressed is Ucs., but not all that is Ucs. is repressed’ (Freud, 1923, p. 17). According to Freud, the contents of the repressed unconscious are related to the emotional traces of childhood experiences, that he called ‘thing representations’ (Sachvorstellung). This concept proposed by Freud ‘consists in the cathexis, if not of the direct memory-images of the thing, at least of remoter memory-traces derived from these’ (1915, p. 201).

Lately, the concept of repressed unconscious has been challenged and revised by Mauro Mancia (2007) and Allan Schore (2011) on the basis of a developmental view of the self in which repression is a more mature defence, based on the left brain activity (see also Mucci, 2021a, 2021b); notoriously the left brain develops and usually become dominant after the first year and a half of life, while the right brain is predominant in the first year and develops first. This un-repressed unconscious is an implicit nucleus of the self (Schore, 2012) which was originally created in connection with genetically inherited possibilities by the regulatory movement occurring between the mother’s and the child’s right brains, which took place primarily in the first year of the child’s life, the critical period for attachment. This regulation helps to develop the right brain of the child before the left brain, hinting at a pre-eminence of emotional and affective life over analytic, decisional, and linguistic processes, and it creates a difference in the two systems of memory.

All the traumatic experiences of those first years cannot be repressed properly but only dissociated, left out, buried in amygdala processes and implicit, somatic memories of developments. The so-called (Freudian) repressed unconscious is related to a more developed self, a kind of mental-self (Qin et al., 2020) that can actively repress or has to do with less severe traumatization (this seems to be more related to what has been conceptualized as self-expansion that, in turn, is related to a neurotic organization of personality - Scalabrini, Mucci & Northoff, 2018). In a secure attachment, with good relational early experiences, through well attuned sensory experiences, the mother aligns with the infant sending messages of affective attunement, emotional holding, reliability, happiness, and dedication. But when there is no alignment between mother and child, probably because of her past un-elaborated and un-integrated traumatic experiences, she can also send messages experienced as traumatic, terrifying, threatening, non-reassuring, or strongly frustrating (see Craparo & Mucci, 2018). This is the situation when the security of attachment is disrupted (Bowlby, 1969) together with reflective and mentalizing capacities (Fonagy & Target, 1997), threatening seriously the organization of the self (Stern, 1985), resulting, in worst cases, in disorganized patterns (Liotti, 2004). These kinds of relational traumatic experiences with the animate environment cannot be repressed because the structures that concern the explicit memory, indispensable for repression, are lacking in the early stages of infancy (Joseph, 1996; Siegel, 1999). Following Mancia (2006, 2007), therefore, these experiences will be the foundation of an early unrepressed unconscious nucleus of the self. Therefore, in contrast to Freud’s view of the repressed unconscious, the unrepressed unconscious might be conceived as the result of the storage in the implicit memory of experiences, phantasies, and defences that belong to the pre-symbolic and pre-verbal stage of development and cannot, therefore, be remembered. It is our contention that intriguingly this unrepressed unconscious can reveal itself in dreams especially in patients who develop non-neurotic pathologies, but pathologies of a more severe kind, rooted on earlier traumatic exchanges.

According to Mancia, dreams can be the privileged representation of this primitive and un-symbolic encoding, giving insight into the phantasies, affects, as well as into the reconstructive elements, related to the pre-verbal and pre-symbolic experiences that characterize the implicit structures of the individual. Dreams within the individual have the function of creating images capable of filling the void of what was never represented, thus giving a first symbolic representation to experiences that were originally unrepresentable, and pre-symbolic. Once the implicit structures of the mind in each patient, together with the unconscious dynamics with which they function are made thinkable, patients will be able to represent the non-representable material of their unrepressed unconscious and to recover those parts of the self which have either been denied or split and projected in the early development of their minds.

On the basis of this dynamic and theoretical configuration, it is possible to suggest that the repressed unconscious finds its own location in the structures of explicit, or autobiographic, memory. Supporting this hypothesis is the recent observation by Anderson and colleagues (Anderson et al., 2004), who demonstrated that the deliberate forgetting of mental experiences, which can be compared to Freudian repression, is accompanied by an increase of activity in the dorsolateral prefrontal areas and a parallel reduction of the hippocampus activity. This phenomenon is opposed to the ‘depressive’ character of dreams (in rapid eye movement – REM - sleep), during which an increase of hippocampal activity and a deactivation of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (Braun et al., 1998) have been observed. On the contrary, the unrepressed unconscious may find in the implicit memory its own organization, promoted by the activation of the amygdala which presides over the emotions (Damasio, 1999; LeDoux, 2000; Bennett & Hacker, 2005). It seems to be associated with the posterior associative cortical areas (temporal-occipital- parietal) of the right hemisphere, as well as in the basal ganglia and in the cerebellum. Intriguingly Solms (1995) has also found that patients with lesions to the posterior associative areas do not dream.

It would, therefore, seem that only within the explicit and episodic memory, or autobiographical memory, where an ‘I’ has been modulated and the structure of the brain and the functions pertaining to memory are more mature, is it possible to have the kind of defence that subtracts those contents from the mass of conscious information, and represses them. As processes controlled by the left brain, they deal with contents that have been consciously learnt and maintained (following the second or third year of development of the brain); they must have undergone repression only in a later moment and subsequently they might become retrievable under certain circumstances (linked to a collaboration of both implicit and explicit systems and through language). The right brain, as the site of implicit memory, becomes the psychobiological base of the unconscious in its most comprehensive meaning in terms of ‘what is not conscious’ and, none the less, leads relevant aspects of our life. In doing so, it is the basis of our motivational and affective life, implicit affective processes become distinguished from explicit cognitive and learning processes (Mucci, 2018, in Craparo & Mucci, 2018).

This other path left open to Freud’s contemporaries (that of early real trauma and subsequent dissociation, encoded implicitly in the body, not of repression as in Freud) would be the course taken by Pierre Janet’s theorization (see also Scalabrini et al., 2020a and Scalabrini Mucci, Angeletti & Northoff, 2020b), on one hand, and Sandor Ferenczi’s theory and practice, on the other (Lingiardi & Mucci, 2014; Mucci, Craparo & Lingiardi, 2019). The discovery of what is inscribed in implicit memory (unconscious but organising what the subject experiences and directing future social exchanges and even personality development) shows that experience is not encoded by a self in the sense of an autonomous, intentional subject as an agent, but a self that is, nonetheless, capable of encoding in the body a personal piece of experience. In other words, it points at the reality of some kind of utter experience not registered verbally, nor encoded semantically (episodic and autobiographical memory, explicit system) but, none the less, existing, directing and influencing the subject in his/her life and often creating suffering (therefore the dream for the traumatized mind would be linked to what the body knows, not to what the mind has repressed - see Mucci, 2018, in Craparo & Mucci, 2018, p. 107).

The traumatic terrain is also the place of another fundamental twist in the theory of self and selflessness, or unconscious state: it has to do with the fact that in order for episodic memory to be active, there needs to be a subject capable of narrating the experience (which can be done also retrospectively, as a consequence of the therapeutic process). In other words, where trauma is, the subject has been deleted, together with the capacity to remember in a left-brain kind of explicit narration, involving linguistic awareness and representation.

Repression as a defence is responsive to anxiety - a negative but regulable affect that signals the potential emergence into consciousness of mental contents that may create unpleasant, but bearable intrapsychic conflict. Dissociation as a defence is responsive to trauma - the chaotic, convulsive flooding by the unregulatable affect that takes over the mind, threatening the stability of selfhood and sometimes sanity (Bromberg, 2011, p. 49). How traumatic and dissociative experiences are manifest in dreams is still partly unclear and it is our aim to propose our personal view.

Dreaming for traumatized and dissociated minds

The dream activity for the traumatized patient is inscribed in the tendency to ‘repeat the trauma’ and in the ‘compulsion to repeat’, therefore assumes the same function of repetition - compulsive, obligatory -, of what has not been psychically resolved, because, precisely, exceeding the individual, intrapsychic processing capacity. The oneiric process, for the traumatized person, is part of those behaviours of affective regulation between body-mindbrain (Mucci, 2018, 2021a, 2021b) that repeat, that is, bring back the ‘traumatic’ element (for Freud, the ‘repressed’: but this pertains to neurotic patients, not to borderline patients), in order to implement a neurobiological, affective, emotional, perceptive, bodily re-elaboration through motor, sensorial and image-related mechanisms. For Freud and for the neurotic patient, the subject is rather induced to repeat the repressed content in the form of a current experience, ‘rather than, as the doctor would like, to remember it as part of his past’ (Freud, 1920, p. 204).

In both visions, in the traumatic dream theorized in 1920 as for the statute of the dream of 1899, what is represented is the statute of the unconscious itself: however, it is a different mode of unconscious, in the first a repressed unconscious, while in the second seems to be more related to the ‘not repressed’ or unrepressed unconscious (Mancia, 2006; Mucci, 2017).

The ‘unrepressed’ unconscious has its raison d’etre in more primitive and ancient psychic formations, rooted in the first years of life, or linked to transcriptions that are only corporeal, due to the activation of the emotional-affective part of memory, based on the functioning of the amygdala (active from birth), not on that of the hippocampus, which instead is possible only when the child is at least two or three old (the memory transcription, among other things, will not be possible, in the future, when the adult subject is in a state of hyperarousal, i.e. traumatizations cannot be registered at the hippocampus level but only at the amygdala level, helping to ensure that the subject does not have a true memory of the event but only a sensation or incomprehensible emotional-bodily states and flashbacks of the event).

In other words, the traumatic dream (and the dream of a severe patient, related to borderline or psychotic organization) depicts the difference between an unconscious understood as repressed, in Freud’s explanation, and an unconscious not removed, probably dissociated early or following trauma, identified with what is deposited at the implicit, somatic level (Mucci, 2018a). This implicit or somatic level seems to parallel the interoceptive or extero- proprioceptive level at the basis of self-constitution and self-manifestation (Qin et al., 2020; Scalabrini, Mucci & Northoff, 2018) vs the mental self that seems to be more related to neurotic organizations.

In contemporary clinical practice, in which we often find ourselves working with pre-oedipal and borderline rather than neurotic and oedipal patients, for whom the development of id-ego and superego would be expected, we believe that dreams need to be analysed and can provide different indications on the functioning of the subject in the complexity of its levels; they can constitute a real internal map of the functioning and of the dialectic not only between conscious and unconscious but also between repressed and dissociated or implicit-not repressed (and therefore expressed by the body sensory and non-verbal but imaginative subsymbolic, Bucci, 1997; Mucci, 2018a).

While the neurotic dream implies a narrative, metaphorical, symbolic line, the traumatic dream, more concrete and linked to the first expressions of the somatic memories activated by the therapy, constitutes a first, and very useful, attempt at staging the trauma before being non-verbal, corporeal. Only through the work of psychotherapy, finally the traumatic dream becomes narratable, verbalizable, symbolic and expressible in a story, thanks to the passage through the images and what there is of sensorial and emotional communication, subsymbolic. This is a manifestation of the healing process between the patient-therapist dyad and their respective relational alignment (Mucci, 2018a).

In the patient traumatized by a human hand, (for the distinction with trauma due to natural catastrophes see Mucci, 2013) what cannot be expressed in words or not yet represented can/may find a first form of representation in the so-called ‘traumatic’ dream, especially in the form of a nightmare. In traumatized and borderline patients, dreams primarily manage a first reconnection between implicit (bodily, amygdala-based somatic, i.e. emotional and sensory) and explicit (narrational, episodic, based mainly on a hippocampal coding) memory, to the extent that whose memory traces of the past are reactivated by triggers encountered both in everyday life and reactivated by the solicitation of working with the therapist (Mucci, 2014, 2018a, 2018b, 2021).

Following the assessment model proposed by Mucci in Borderline Bodies (Mucci, 2018a), dreams, though not the main axis for the evaluation of the mental functioning of borderline patients, show the lack of symbolic capacity in severe alexithymic patients; the capacity for symbolic elaboration as constructed and shown in dreams can certainly be one of the elements in the diagnostic chart as elaborated by Mucci (2018a, 2020, 2021), in which the three main, vertical axis evaluate attachment and intergenerational trauma, then assess the actual personality disorders and comorbidity, then evaluate the kind of bodily attack (self-harming, suicidality, eating disorders and addiction); while the secondary horizontal axis considers respectively the dream-symbolic capacity (vs lack of dream and alexithymia and concrete thinking) and the axis of sexual identity diffusion, also devised by Mucci in connection to the typical identity diffusion that Otto Kernberg considers one of the main diagnostic elements towards what he terms borderline organization (Kernberg, 1984).

Within the context of treatment process, the dream function is for us both intrapsychic as well as interpersonal since they constitute not only an internal map for inner dynamics and functioning, but they are also a bridge of communication to the therapist, the point of becoming a sort of enactment, not only of the patient’s internal scenario and treatment process (Bromberg, 2011), but even of something related to intersubjective communication of the two unconscious (in the sense of repressed unconscious and non-repressed unconscious, of both; Mucci, 2018a, 2018b; Schore, 2011, 2012).

Dreams might also manifest themselves in form of nightmares carried by a major affect that invades the patient’s conscious life. Nightmares are important re-elaborations and working through of traumatic material or sometimes even unconscious repetition or implicit memory retrievals of a dissociated nature elicited by the therapeutic actions. They are to be seen and valued as the beginning of a verbalizing activity of what was until then proto-mental or, to use Bucci’s terminology, pre-symbolic or nonverbal sub-symbolic, a real link between the two hemispheres and a link between what the body has contained in dissociated and unverbalized form until then and what the body-mind-brain system is coming to see visually and metaphorically and has started mentalizing and putting into words (Mucci, 2018a).

Dreams show therefore the most direct movement between body-mind-brain, as well as the link between implicit memory and the story reconstructed in therapy. Ferenczi, closer to a description of the dissociative/traumatized mind than to Freud’s model of the repressed (not of traumatic, mostly external origin for Freud but from a conflictual, intrapsychic origin) has called this process activated through dreams the ‘traumatolytic’ function of the dreams (Ferenczi, 1910; Martin Cabré, 2011). The dream becomes a first form of verbalization and integration into consciousness of what was until then unrepressed implicit material - corporeally dissociated or somaticized memories - of traumatic early memory. This is totally in agreement with what Mauro Mancia (2006, 2007) hypothesized to be the function of traumatic dreams in therapy. Nightmares are clearly a first way to elaborate negative affects or traumatic memories at the unconscious (implicit) conflictual or traumatic level, establishing a first communication between implicit nonverbal and explicit verbal memory, constituting a useful road to symbolization and also allowing the expression of those negative affects that, in neuroscientific terms, have been toxic for the amygdala in the traumatic experience and never released. This is what has been lately defined as the ‘integrative function of traumatic dreams’ (Mucci, 2013). They are the neurological correlates of enactments (as described by Bromberg and by Schore) connected to the relational intersubjective work between patient and therapist, a bridge in their relationship connecting their right-brain communication, allowing also the elaboration of traumatic memories.

Finally, severe borderline and narcissistic patients, closer to a psychotic and psychosomatic continuum of severity than to the neurotic spectrum, present a serious difficulty in dreaming or at least in remembering the night dreaming activity. They seem to have a problem in symbolic appreciation and rendering of emotional experience, so that the body receiving the emotions and the external stimuli is not in tune with the emotional recognition of those affects so that unrecognized and unverbalized emotions bypass the symbolic, representational rendering and become entrapped in the body, in the soma, with a short circuit.

This is also the case of the alexithymic patients, also of severe traumatic origin and to be included in our opinion within the further spectrum of the severe narcissistic formations (stemming from severe neglect and relational deficit). This alexythimic self shows a deficit in symbolic oneiric capacity whose counterpart is the incapacity to name feelings and affects in self and body (Mucci, 2018a).

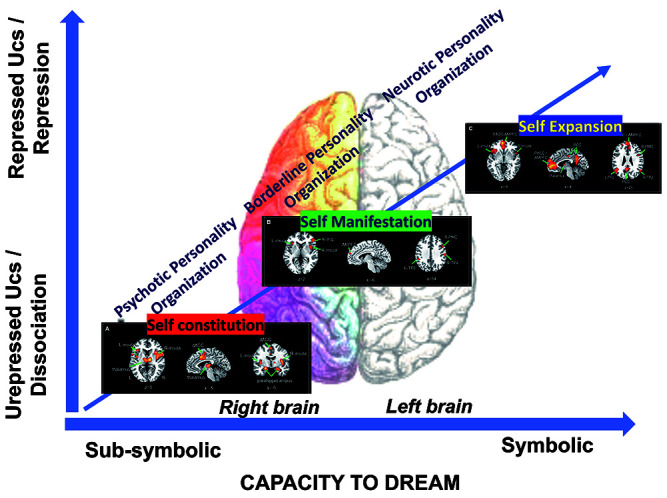

Only the appropriate and secure psychotherapeutic relationship, focusing to become aware of what the body feels and to verbalize the emotions, will enable the patient to use the dream activity as a symbolic laboratory, as an access to work through the somatic/traumatic/unverbalized/ unrepressed elements of mental functioning linked to past experiences (Figure 1).

Conclusions

Sometimes the enactments presented by dreams are even intergenerational (as seen in working with generations of massive trauma, such as in the Shoah generations, Mucci, 2013). However, this interpersonal communication of dreams, which becomes similar to an enactment between the two participants, is not the simple contribution of transference- countertransference as understood in traditional psychoanalytic practice; it depends on the reactivation of the dissociated parts in the patient and is possible thanks to the contribution of the therapist, who functions as a witness, an embodied witnessing mechanism, a function of ‘embodied testimony’ in which the whole mind-body-brain system of the two subjects of the treatment participates (Mucci, 2018a, 2020).

Figure 1.

Visual representation of the proposed model related to the capacity to dream (sub-symbolic and symbolic), different unconscious (unrepressed vs repressed) & defences (dissociation vs repression). In this model we connect the hierarchy of self (Qin, Wang, & Northoff, 2020) with different personality organization/levels of self (as reported in Scalabrini, Mucci, & Northoff, 2018) together with Mucci (2018a) and Schore (2012) right brain model of personality disorders.

As the therapeutic process can be defined as the dialogue of the two body/mind-brain of the protagonists, also addressed to the right brain of the one in conjunction to the right brain of the other (being the right brain the most involved with the body itself), similarly the dream activity, especially during therapeutic healing process, can be viewed as the outcome of the regulatory and communicative efforts between the two minds and the two unconscious (repressed or not repressed) of the participants. The ongoing communication between them makes the dual unconscious movements the actual representation of the implicit and explicit, intrapsychic and interpersonal activation of the self and other processes in the analytic ‘dance’: if the dream for Freud was the royal path to the unconscious, nowadays this path has been defined more and more by several interdisciplinary and intersubjective path, both in terms of development and in terms of restoration and cure or healing. The work through the dreams of the patients is a form of ‘embodied witnessing’ (Mucci, 2018a, 2020), where the analyst through his/her embodied participation not only gives back to the patient a restored and restructured sense of self-continuity and a sense of emotional truth of what has happened in early experience but also, trough the analyst’s role as witness, emotional truth is acknowledged and recognized taking finally a symbolic psychic form instead of un-symbolic acting resulting in destructiveness and symptomatic actions.

Funding Statement

Funding: this project/research was supported by ‘Search for Excellence – UdA’ (University G. d’Annunzio of Chieti Pescara) to A.S. for the project SYNC (The Self and its psYchological and Neuronal Correlates – Implications for the understanding and treatment of disorders of Self).

References

- Anderson M. C., Ochsner K. N., Kuhl B., Cooper J., Robertson E., Gabrieli S. W., Gabrieli J. D. (2004). Neural systems underlying the suppression of unwanted memories. Science, 303(5655), 232-235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atzil S., Gao W., Fradkin I., Barrett L. F. (2018). Growing a social brain. Nature Human Behaviour, 2(9), 624-636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atzil S., Barrett L. F. (2017). Social regulation of allostasis: Commentary on ‘Mentalizing homeostasis: The social origins of interoceptive inference’ by Fotopoulou and Tsakiris. Neuropsychoanalysis, 19(1), 29-33. [Google Scholar]

- Benedetti F., Poletti S., Radaelli D., Ranieri R., Genduso V., Cavallotti S., D’Agostino A. (2015). Right hemisphere neural activations in the recall of waking fantasies and of dreams. Journal of sleep research, 24(5), 576-582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett M. R., Hacker P. M. S. (2005). Emotion and cortical- subcortical function: conceptual developments. Progress in Neurobiology, 75(1), 29-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. (1969). Attachment and loss, v. 3 (Vol. 1). London: Hogarth Press. [Google Scholar]

- Braun A. R., Balkin T. J., Wesensten N. J., Gwadry F., Carson R. E., Varga M., Herscovitch P. (1998). Dissociated pattern of activity in visual cortices and their projections during human rapid eye movement sleep. Science, 279(5347), 91-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bromberg P. M. (2011). The shadow of the tsunami and the growth of the relational mind. New York, NY: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Bucci W. (1997). Psychoanalysis and cognitive science: A multiple code theory. New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Burgess N., Maguire E. A., O’Keefe J. (2002). The human hippocampus and spatial and episodic memory. Neuron, 35(4), 625-641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabré L. J. M. (2011). La funzione traumatolitica del sogno. Rivista di Psicoanalisi, 57(2), 395-399. [Google Scholar]

- Christoff K., Irving Z. C., Fox K. C., Spreng R. N., Andrews-Hanna J. R. (2016). Mind-wandering as spontaneous thought: a dynamic framework. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 17(11), 718-731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craparo G., Mucci C. (Eds.). (2018). Unrepressed unconscious, implicit memory, and clinical work. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Craig A. D. (2010). The sentient self. Brain structure and function, 214, 563-577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damasio A. R. (1999). How the brain creates the mind. Scientific American, 281(6), 112-117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dang-Vu T. T. (2012). Neuronal oscillations in sleep: insights from functional neuroimaging. Neuromolecular medicine, 14(3), 154-167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Gennaro L., Cipolli C., Cherubini A., Assogna F., Cacciari C., Marzano C., Spalletta G. (2011). Amygdala and hippocampus volumetry and diffusivity in relation to dreaming. Human brain mapping, 32(9), 1458-1470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewan E. M. (1970). The programming (P) hypothesis for REM sleep. In Ernest Harmann (Eds.), Sleep and dreaming (Vol. 7, pp. 295-307). Boston: Little Brown. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domhoff G. W., Fox K. C. (2015). Dreaming and the default network: A review, synthesis, and counterintuitive research proposal. Consciousness and cognition, 33, 342-353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairbairn W. R. D. (1944). Endopsychic structure considered in terms of object-relationships. International Journal of Psycho- Analysis, 25, 70-92. [Google Scholar]

- Ferenczi S. (1910). The psychological analysis of dreams. The American Journal of Psychology, 21(2), 309-328. [Google Scholar]

- Fonagy P., Target M. (1997). Attachment and reflective function: Their role in self-organization. Developmental Psychopathology, 9(4), 679-700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox K. C., Nijeboer S., Solomonova E., Domhoff G. W., Christoff K. (2013). Dreaming as mind wandering: evidence from functional neuroimaging and first-person content reports. Frontiers in human neuroscience, 7, 412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox K. C., Girn M. (2018). 28 Neural Correlates of Self- Generated Imagery and Cognition Throughout the Sleep Cycle. The Oxford Handbook of Spontaneous Thought: Mind-Wandering, Creativity, and Dreaming, 371. [Google Scholar]

- Freud S. (1900). The Interpretation of Dreams. SE 4, pp. ix- 627. London: Hogarth. [Google Scholar]

- Freud S. (1915). The unconscious. S. E., 14: 166-204. London: Hogarth. [Google Scholar]

- Freud S. (1920). Al di là del principio di piacere. In OSF, vol. IX. Torino: Bollati Boringhieri, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Freud S. (1923). The Ego and the Id. S. E., 19: 12-59. London: Hogarth [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher S. (2005). Dynamic models of body schematic processes. Advances in consciousness research, 62, 233. [Google Scholar]

- Ginot E. (2015). The Neuropsychology of the Unconscious: Integrating Brain and Mind in Psychotherapy (Norton Series on Interpersonal Neurobiology). New York, NY: WW Norton & Company. [Google Scholar]

- Hobson J. A. (2009). REM sleep and dreaming: towards a theory of protoconsciousness. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 10(11), 803-813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph R. (1996). Neuropsychiatry, neuropsychology, and clinical neuroscience: Emotion, evolution, cognition, language, memory, brain damage, and abnormal behaviour. New York, NY: Williams & Wilkins Co. [Google Scholar]

- Jung C. G. (2013). Dream Analysis 1: Notes of the Seminar Given in 1928-30. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Jung C. H. (2014). Collected works of CG Jung, Volume 8: Structure & dynamics of the psyche. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kernberg O. F. (1975). Borderline conditions and pathological narcissism. New York, NY: Aronson. [Google Scholar]

- Kernberg O. F. (1984). Severe personality disorders: Psychotherapeutic strategies. New Haven, CT: Yale UP. [Google Scholar]

- Kohut H. (1977). La guarigione del Sè [The restoration of the self]. Torino: Boringhieri; (1980). [Google Scholar]

- Kohut H. (1971). The analysis of the self. A systematic approach to the psychoanalytic treatment of personality disorders. New York, NY: International Universities Press. [Google Scholar]

- LeDoux J. E. (2000). Emotion circuits in the brain. Annual review of neuroscience, 23(1), 155-184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leuzinger-Bohleber M. (2018). Finding the body in the mind: Embodied memories, trauma, and depression. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Lingiardi V., Mucci C. (2014). Da Janet a Bromberg, passando per Ferenczi. Psichiatria e psicoterapia, 33(1). [Google Scholar]

- Lingiardi V., McWilliams N. (Eds.). (2017). Psychodynamic diagnostic manual: PDM-2. New York, NY: Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Liotti G. (2004). Trauma, dissociation, and disorganized attachment: Three strands of a single braid. Psychotherapy: Theory, research, practice, training, 41(4), 472. [Google Scholar]

- Mancia M. (2006). Implicit memory and early unrepressed unconscious: Their role in the therapeutic process (How the neurosciences can contribute to psychoanalysis) 1. The International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 87(1), 83-103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mancia M. (Ed.). (2007). Psychoanalysis and neuroscience. Springer Science & Business Media [Google Scholar]

- Menon V., Uddin L. Q. (2010). Saliency, switching, attention and control: a network model of insula function. Brain structure and function, 214(5-6), 655-667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moser U., von Zeppelin I. (1996). Dergeträumte Traum. Stuttgart: Kohlhammer. [Google Scholar]

- Mucci C. (2013). Beyond individual and collective trauma: Intergenerational transmission, psychoanalytic treatment, and the dynamics of forgiveness. New York & London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Mucci C. (2014). Trauma e perdono. Una prospettiva psicoanalitica internazionale. Milano: Raffaello Cortina. [Google Scholar]

- Mucci C. (2017). Implicit memory, unrepressed unconscious, and trauma theory: The turn of the screw between contemporary psychoanalysis and neuroscience. Craparo G., Mucci C. (Eds.), Unrepressed unconscious, implicit memory and clinical work (pp. 99-129). London: Karnac. [Google Scholar]

- Mucci C. (2018a). Borderline Bodies: Affect Regulation Therapy for Personality Disorders (Norton Series on Interpersonal Neurobiology). New York, NY: WW Norton & Company. [Google Scholar]

- Mucci C. (2018b). Partecipazione affettiva dell’analista e testimonianza incarnata. The Wisebaby. Il poppante saggio. Rivista del rinascimento ferencziano, 2, 167-183. [Google Scholar]

- Mucci C. (2020). Corpi Borderline. Regolazione affettiva e clinica dei disturbi di personalità. Milano: Raffaello Cortina Editore srl. [Google Scholar]

- Mucci C., Craparo G., Lingiardi V. (2019). From Janet to Bromberg, via Ferenczi Standing in the spaces of the literature on dissociation. Craparo G., Ortu F., van der Hart O. (Eds). Rediscovering Pierre Janet (pp. 75-92). New York, NY: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Mucci C, Scalabrini A. (2021) Traumatic effects beyond diagnosis: The impact of dissociation on the mind-body-brain system. Psychoanalytic Psychology, doi:10.1037/pap0000332. [Google Scholar]

- Mucci C. (2021a). Dissociation vs Repression: A New Neuropsychoanalytic Model for Psychopathology. American Journal of Psychoanalysis, 81(1), 82-111. doi:10.1057/s11231-021-09279-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mucci C. (2021b). A right-brain dissociative model for rightbrain disorders: Dissociation vs repression in borderline and other severe psychopathologies of early traumatic origin. Tweedy R. (Ed.), The Divided Therapist. Hemispheric Difference and Contemporary Psychotherapy. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Nalbantian S. (2011). The memory process: neuroscientific and humanistic perspectives. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Northoff G. (2011). Neuropsychoanalysis in Practice: Brain, Self and Objects. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Northoff G., Huang Z. (2017). How do the brain’s time and space mediate consciousness and its different dimensions? Temporo-spatial theory of consciousness (TTC). Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 80, 630-645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Northoff G. (2016). Is the self a higher-order or fundamental function of the brain? The ‘basis model of self-specificity’ and its encoding by the brain’s spontaneous activity. Cognitive neuroscience, 7(1-4), 203-222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Northoff G. (2018). How does the brain’s spontaneous activity generate our thoughts? The spatiotemporal theory of taskunrelated thought (STTT). Christoff K., Fox C.R. (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Spontaneous Thought: Mind-Wandering, Creativity, and Dreaming (pp. 55-70). Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Padel J. (1978). Object relational approach. Fosshage J., Loew C.A. (Eds.), Dream interpretation: A comparative study, Revised Edition (pp. 125-148). New York, NY: PMA Publishing Corp. [Google Scholar]

- Panksepp J., Biven L. (2012). The archaeology of mind: neuroevolutionary origins of human emotions (Norton series on interpersonal neurobiology). New York, NY: WW Norton & Company. [Google Scholar]

- Qin P., Wang M., Northoff G. (2020). Linking Bodily, Environmental and Mental States In the Self-A Three-level Model Based on A Meta-analysis. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 115, 77-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scalabrini A., Mucci C., Northoff G. (2018). Is our self-related to personality? A neuropsychodynamic model. Frontiers in human neuroscience, 12, 346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scalabrini A., Mucci C., Esposito R., Damiani S., Northoff G. (2020a). Dissociation as a disorder of integration–On the footsteps of Pierre Janet. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry, 101, 109928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scalabrini A., Mucci C., Angeletti L. L., Northoff G. (2020b). The self and its world: a neuro-ecological and temporospatial account of existential fear. Clinical Neuropsychiatry, 17(2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scarone S., Manzone M. L., Gambini O., Kantzas I., Limosani I., D’Agostino A., Hobson J. A. (2008). The dream as a model for psychosis: an experimental approach using bizarreness as a cognitive marker. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 34(3), 515-522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schore A. N. (2011). The right brain implicit self lies at the core of psychoanalysis. Psychoanalytic dialogues, 21(1), 75-100. [Google Scholar]

- Schore A. N. (2012). The science of the art of psychotherapy (Norton series on interpersonal neurobiology). New York, NY: WW Norton & Company. [Google Scholar]

- Siclari F., Baird B., Perogamvros L., Bernardi G., LaRocque J. J., Riedner B., Tononi G. (2017). The neural correlates of dreaming. Nature neuroscience, 20(6), 872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siclari F., Bernardi G., Cataldi J., Tononi G. (2018). Dreaming in NREM sleep: a high-density EEG study of slow waves and spindles. Journal of Neuroscience, 38(43), 9175-9185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel D. J. (1999). The developing mind: Toward a neurobiology of interpersonal experience. New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Solms M. (1995). New findings on the neurological organization of dreaming: Implications for psychoanalysis. The Psychoanalytic Quarterly, 64(1), 43-67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solms M. (2020). New project for a scientific psychology: General scheme. Neuropsychoanalysis, 1-31. [Google Scholar]

- Stern D. N. (1985). The Interpersonal World of the Infant: A View from Psychoanalysis and Developmental Psychology. New York, NY: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Stickgold R., Walker M. P. (2007). Sleep-dependent memory consolidation and reconsolidation. Sleep medicine, 8(4), 331-343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stickgold R., Hobson J. A., Fosse R., Fosse M. (2001). Sleep, learning, and dreams: off-line memory reprocessing. Science, 294(5544), 1052-1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stolorow R. D., Atwood G. E. (1989). The unconscious and unconscious fantasy: An intersubjective-developmental perspective. Psychoanalytic Inquiry, 9(3), 364-374. [Google Scholar]

- Strachey J. (1961). Editor’s introduction. Freud S.. (1923). The ego and the id. SE 19, 3-11. London, Hogarth Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sui J., Humphreys G. W. (2015). The integrative self: How self-reference integrates perception and memory. Trends in cognitive sciences, 19(12), 719-728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsakiris M. (2017). The multisensory basis of the self: from body to identity to others. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 70(4), 597-609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zilio F., Gomez-Pilar J., Cao S., Zhang J., Zang D., Qi Z., Northoff G. (2021). Are intrinsic neural timescales related to sensory processing? Evidence from abnormal behavioral states. NeuroImage, 226, 117579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zilio F. (2020). Consciousness and World. A Neurophilosophical and Neuroethical Account. Pisa: Edizioni ETS. [Google Scholar]

- Sui J., Humphreys G. W. (2015). The integrative self: How self-reference integrates perception and memory. Trends in cognitive sciences, 19(12), 719-728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsakiris M. (2017). The multisensory basis of the self: from body to identity to others. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 70(4), 597-609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zilio F., Gomez-Pilar J., Cao S., Zhang J., Zang D., Qi Z., Northoff G. (2021). Are intrinsic neural timescales related to sensory processing? Evidence from abnormal behavioral states. NeuroImage, 226, 117579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zilio F. (2020). Consciousness and World. A Neurophilosophical and Neuroethical Account. Pisa: Edizioni ETS. [Google Scholar]