Abstract

Introduction

SMART Recovery is a popular mutual support group program. Little is known about its suitability or perceived helpfulness for Indigenous peoples. This study explored the cultural utility of SMART Recovery in an Australian Aboriginal context.

Methods

An Indigenous‐lensed, multi‐methods, exploratory study design was used to develop initial evidence of: (i) attributes of Aboriginal SMART Recovery facilitators and group members; (ii) characteristics of Aboriginal‐led SMART Recovery groups; (iii) perceived acceptability and helpfulness of SMART Recovery; and (iv) areas for potential improvement. Data were collected by synthesising Indigenous qualitative methods (research topic and social yarning) with western qualitative and quantitative methods (participant surveys, program adherence rating scale, group observations and field notes). Data were analysed using thematic analysis.

Results

Participants were a culturally diverse sample of male and female Aboriginal facilitators (n = 10) and group members (n = 11), aged 22–65 years. Aboriginal‐led SMART Recovery groups were culturally customised to suit local contexts. Program tools ‘goal setting’ and ‘problem solving’ were viewed as the most helpful. Suggested ways SMART Recovery could enhance its cultural utility included: integration of Aboriginal perspectives into facilitator training; creation of Aboriginal‐specific program and marketing materials; and greater community engagement and networking. Participants proposed an Aboriginal‐specific SMART Recovery program.

Discussion and Conclusions

This study offers insights into Aboriginal peoples' experiences of SMART Recovery. Culturally‐informed modifications to the program were identified that could enhance cultural utility. Future research is needed to obtain diverse community perspectives and measure health outcomes associated with group attendance.

Keywords: mutual support group, Indigenous, addiction, substance use, gambling

Introduction

Mutual support groups are a popular treatment option for problematic substance use and other problematic behaviours like gambling [1, 2]. Such groups offer non‐clinical, community‐based meetings that harness shared experiential knowledge and mobilise member‐to‐member social, emotional and informational support [3]. Appealing to recovery seekers, meetings can typically be accessed weekly, at no cost and over a long term [4]. Regular group attendance has been shown to prevent relapse [5], alleviate comorbidities such as depression [6] and promote long‐term abstinence [7]. Reciprocal group support can help to build personal insight [8], enhance problem‐solving skills [9] and reduce risk‐taking behaviours [10].

The most widely accessed forms of mutual support are the 12‐step programs (i.e. alcoholics anonymous, gamblers anonymous) and SMART Recovery (self‐management and recovery training). Approximately 25 000 SMART Recovery meetings are delivered in over 23 different countries [11]. Of these, over 250 weekly meetings occur face‐to‐face and online Australia‐wide [12, 13].

A detailed description of SMART Recovery's core program contents and operational features is published elsewhere [14]. In brief, SMART Recovery is a free, empirically‐based mutual support group program that imparts tools and techniques derived from motivational interviewing and cognitive behavioural therapy techniques to encourage ‘self‐empowered behaviour change’ [12]. The program's core tools are: ‘change plan’, ‘cost benefit analysis’, ‘goal setting’, ‘problem solving', ‘role play', ‘thoughts, feelings, and actions’ and ‘urge log’ [15].

SMART Recovery caters for individuals (16 years +) seeking recovery from both substance and non‐substance related addiction such as alcohol, illicit drugs and gambling [11]. Meetings are led by trained facilitators who follow a manualised 18‐item program protocol [16]. Each meeting typically has the following format: ‘check in', problem‐focused discussion, establishment of a ‘7‐day plan’ and a ‘check out’ [17].

There is a small but growing body of evidence demonstrating the effectiveness of the SMART Recovery program [18]. Research has shown that participation is associated with reduced substance use [19, 20], establishment of supportive social networks [21] and improved quality of life [22]. More research is needed, however, to understand SMART Recovery's utility as a clinical or public health tool [18].

There is also the need for research to examine the cultural appropriateness of mutual support groups for Indigenous populations. A recent systematic review [23] for similarly colonised countries (Australia, New Zealand, Canada, USA and Hawaii) identified just four peer‐reviewed studies examining mutual support groups for Indigenous peoples. All of those studies focused on Native American Indian cultures syncretised to Alcoholics Anonymous [24, 25, 26, 27] and no study reported on Indigenous peoples' perspectives on the group model. This paucity of research highlights the need for empirical investigation of Indigenous peoples' experiences and outcomes associated with mainstream mutual support group attendance.

Indigenous health advocates worldwide are calling for more research on the effectiveness of culture‐based interventions to address mental health and substance use conditions amongst Indigenous populations [2, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33]. The under‐representation of Indigenous voices within previous mutual support group studies has hindered the translation of Indigenous cultural knowledge into health‐promoting policies and practices [34, 35]. Research conducted with and for Indigenous peoples will help build the body of knowledge needed for understanding the cultural appropriateness and potential benefits of mutual support groups for Indigenous populations [32, 36].

To address these knowledge gaps, we conducted a multi‐method [37] exploration [38] of the cultural utility of SMART Recovery for Aboriginal peoples in Australia. For the purpose of this study, cultural utility was defined by the authors as ‘the perceived suitability and helpfulness of a health intervention within a specific cultural context’. To ensure the evaluation was culturally‐informed, an Indigenous research perspective (lens) [39, 40, 41, 42] was used to: (i) describe the attributes of Aboriginal SMART Recovery facilitators and group members; (ii) describe the characteristics of Aboriginal‐led SMART Recovery groups; (iii) explore Aboriginal facilitators' and group members' perceptions of acceptability and helpfulness of SMART Recovery; and (iv) identify areas for potential improvement.

Methods

Study design

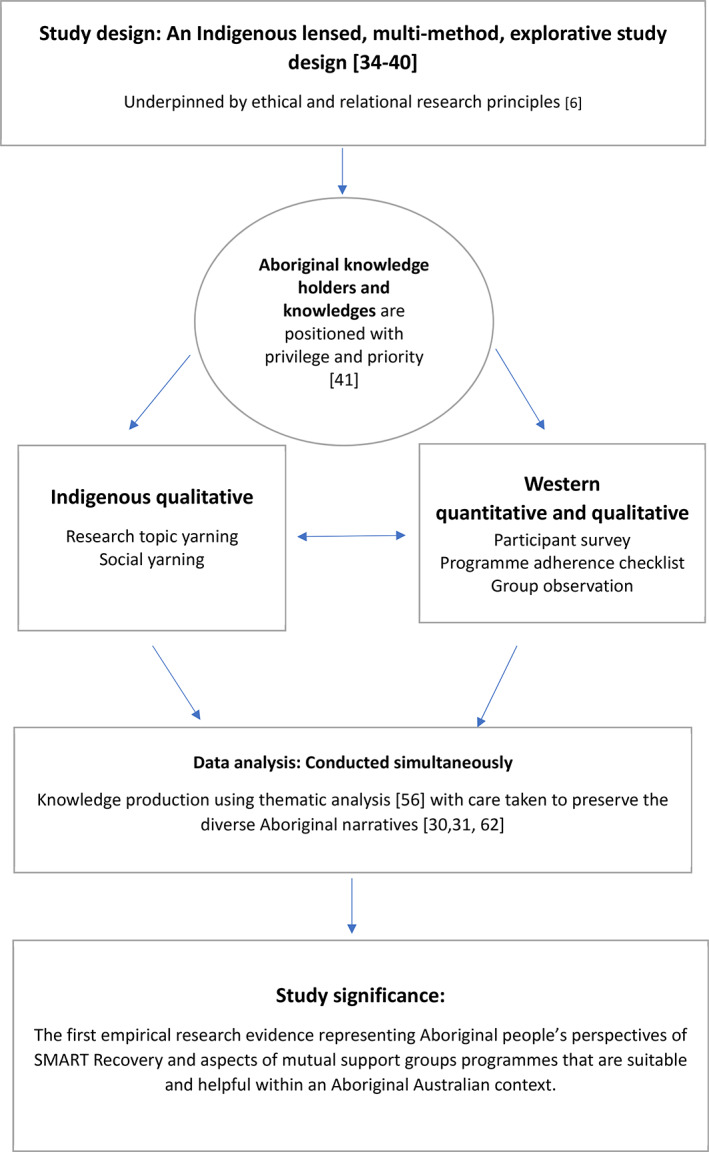

We used a multi‐method study design with an Indigenous research lens [39, 40, 41, 42, 43] to explore the cultural utility of SMART Recovery in an Australian Aboriginal context (see Figure 1). Data were collected concurrently by synthesising western qualitative and quantitative methods (group observation, field‐notes and participant survey [44, 45]) with Indigenous qualitative research methods (research topic yarning and social yarning [46, 47]). Research topic yarning is a relational and culturally acceptable way to obtain Indigenous peoples perspectives in relation to a research topic [46]. Social yarning refers to informal and impromptu conversations that occurs between researcher and participant before and/or after official data collection begins (i.e. research topic yarning) [46]. When used together, both yarning styles can help to build trust and rapport between researcher and participant and can support participants' autonomy [48]. This approach has been shown to enhance cultural and scientific credibility of research findings [39]. Themes emerging from quantitative and qualitative data were synthesised during data analysis [49].

Figure 1.

Study design.

Setting

The participants in this study represented five diverse Aboriginal communities spanning rural, remote and urban contexts and included Yuin, Gadigal and Bunjalung (New South Wales; NSW) and Nukunka and Kaurna (South Australia; SA).

Participants

Participants were 10 Aboriginal SMART Recovery facilitators (Table 1), 13 group members (Table 2) and three Aboriginal‐led SMART Recovery groups; referred herein as Groups 1 (rural NSW), 2 (remote SA) and 3 (urban SA; see Table 3).

Table 1.

Socio‐cultural characteristics for Aboriginal SMART Recovery's group facilitators

| Characteristic | (n = 10) | % |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | 7 | 70 |

| Female | 3 | 30 |

| Age, years | ||

| 35–45 | 3 | 30 |

| 46–55 | 4 | 40 |

| 56–65 | 3 | 30 |

| Indigeneity | ||

| Aboriginal | 10 | 100 |

| Geographical locality | ||

| Rural NSW | 3 | 30 |

| Urban NSW | 2 | 20 |

| Remote NSW | 2 | 20 |

| Remote SA | 2 | 20 |

| Urban SA | 1 | 10 |

| Highest level of education | ||

| Year 12 or below | 4 | 40 |

| Graduate certificate or diploma | 2 | 20 |

| University degree | 4 | 40 |

| Role worked as a facilitator | ||

| AOD support worker | 7 | 70 |

| SEWB counsellor | 1 | 10 |

| Drug health project officer | 1 | 10 |

| MERT clinician | 1 | 10 |

| Facilitation experience | ||

| Mean number of groups | 10.3 (SD = 9.9) | |

| Facilitating as solo presenter | 1 | 10 |

| Facilitating as co‐facilitator | 6 | 60 |

| Facilitating one group | 4 | 70 |

| Facilitating multiple groups | 3 | 30 |

AOD, alcohol and other drugs; MERT, Magistrates Early Referral into Treatment; NSW, New South Wales; SA, South Australia; SEWB, social and emotional wellbeing.

Table 2.

Socio‐cultural characteristics, patterns of attendance and concurrent treatments for Aboriginal SMART Recovery's group members

| Characteristic | (n = 13) | % |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | 5 | 38 |

| Female | 8 | 62 |

| Age, years | ||

| 20–35 | 5 | 38 |

| 36–45 | 7 | 54 |

| 46 + | 1 | 8 |

| Indigeneity | ||

| Aboriginal | 11 | 92 |

| Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander | 2 | 8 |

| Highest level of education | ||

| Year 12 or below | 10 | 77 |

| Diploma level | 2 | 15 |

| University degree | 1 | 8 |

| Employment status | ||

| Currently employed | 2 | 15 |

| Unemployed | 11 | 85 |

| Has stable accommodation | ||

| Yes | 11 | 85 |

| No | 2 | 15 |

| Main reason for attending | ||

| Alcohol | 1 | 8 |

| Drugs | 5 | 38 |

| Alcohol and other drugs (AOD) | 3 | 23 |

| Food/eating | 2 | 15 |

| Relapse prevention (for AOD) | 1 | 8 |

| To support others | 1 | 8 |

| Length of attendance | ||

| First time | 2 | 15 |

| 2–4 weeks | 5 | 39 |

| 6 weeks to 3 months | 3 | 23 |

| 4 to 6 months | 2 | 15 |

| 7 + months | 1 | 8 |

| Frequency of attendance | ||

| Weekly | 13 | 100 |

| Accessing concurrent treatment | ||

| Psychology | 7 | 53 |

| Drug and alcohol counselling | 3 | 23 |

| GP (pharmacotherapy) | 2 | 15 |

| Family support service | 2 | 15 |

| Methadone clinic | 2 | 15 |

| Relapse prevention service | 1 | 8 |

| Have attended alternative mutual support groups | ||

| None | 10 | 76 |

| Alcoholics anonymous (AA) | 1 | 8 |

| Narcotics anonymous (NA) | 1 | 8 |

| AA and NA | 1 | 8 |

Table 3.

Characteristics of Aboriginal‐led SMART Recovery groups

| Group | Location | State | Service setting | Facilitators (n) | Participants (n) | Group characteristics | Group features | Environmental features |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Rural | NSW | ACCHO | Co‐facilitated; 2 male | n = 4; 2 male, 2 female | Aboriginal only, aged 16+, mixed gender, weekly. | Transport to and from groups, one–one counselling with facilitators, integrated in a holistic model of care (e.g. doctors, family support, dentist, material assistance food, inclusion of other health service staff). |

Light, airy room, circular open seating, whiteboard integrated into circle, facilitators seated in the group, food and beverages laid out, family members involved in the group. Facilitators did not use the current SMART Recovery Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander facilitator and group member handbook. |

| 2 | Remote | SA | State funded health service | Co‐facilitated; 1 male, 1 female | n = 3; 3 female, 1 male | Aboriginal only, aged 16+, female only, weekly. | Transport to and from groups, one–one counselling with facilitators, referrals to other services, food, guest speakers, inclusion of other health service staff, attendance extended to family and friends. |

Circular seating around a table, whiteboard at the end of table, facilitator presented group while standing at whiteboard, food and beverages laid out, family members were involved in the group. Facilitators did not use the current SMART Recovery Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander facilitator and group member handbook. |

| 3 | Urban | SA | ACCHO | Solo facilitator; 1 male | n = 6; 4 female, 2 male | Aboriginal only, aged 16+, mixed gender, weekly. | One–one counselling with facilitators, integrated within a holistic model of care (e.g. doctors, family support, dentist, material assistance), food, guest speakers, inclusion of other health service staff, attendance extended to family and friends. |

Circular seating around the table, facilitator seated at the table and within easy access to whiteboard, food and beverages available in adjoining kitchen, members were allowed to leave the room, partners and family members were involved in the group. Facilitators did not use the current SMART Recovery Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander facilitator and group member handbook. |

ACCHO, Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation; NSW, New South Wales; SA, South Australia.

Ethics and informed consent

Ethical approval was granted by the University of Wollongong Human Research Ethics Committee (#2018/398), the Aboriginal Health Council of South Australia (04‐19‐845), the Western Australia Aboriginal Health Ethics Committee (939) and the Aboriginal Health and Medical Research Council of New South Wales (1447/18). Participants provided written and verbal consent through an informed process. An additional opt‐out consent process was used to safeguard participants during the group observations [50]. This was extended to include unplanned staff or community members who were also present. No individuals exercised the opt‐out option.

Procedure

Recruitment

Facilitators

The SMART Recovery group facilitators were required to self‐identify as being of Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander descent and to have completed SMART Recovery approved training. Facilitators were recruited via phone or email (by ED) using a mailing list provided by SMART Recovery Facilitators were also recruited using snowball sampling via the researchers' professional and community networks (ED, KCl, KL, KCo, PK) or via an advertisement placed on the SMART Recovery website.

Group members

Group members were eligible for inclusion if they were aged 18+, self‐identified as being of Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander descent and had past or current involvement in an Aboriginal‐led SMART Recovery group. Group members participating in this study were a convenience sample of individuals who were present during one of the group observations. Group members only were reimbursed for their time ($20 shopping chain voucher).

Aboriginal‐led SMART Recovery groups

Aboriginal‐led SMART Recovery groups were recruited via the facilitators after permission was received from the facilitators' service managers. Group members were provided with advanced notice of the observation date and the researcher's intentions ahead of time to avoid coercion.

Data collection

All information for this study was collected between October and December 2019 (by ED). Quantitative and qualitative data were collected simultaneously using participant surveys, group observations, hand‐recorded field notes and research topic yarning and social yarning (hereafter, ‘yarn[s]’) [46]. Equal priority was given to all approaches to elicit descriptively rich data [51] and to minimise bias [52].

Facilitators and group members were asked to complete a self‐administered survey before participating in a yarn [46]. Surveys were piloted (by ED, KL and a local Aboriginal Elder). The use of a survey before the yarns avoided the need for a question‐answer dialogue between researcher and participant. This enabled us to preserve the relational, story‐telling nature of yarning [53].

Five facilitator yarns and all group member yarns (n = 11) were conducted 1:1, face‐to‐face after their respective group had been observed. Due to geographical distance, the remaining facilitators (n = 5) completed a survey via email and participated in a telephone yarn. Mean duration of each yarn was 30.2 min (SD = 10.6; facilitators) and 6.9 min (SD = 2.6; members). All yarns were audio recorded and professionally transcribed verbatim. Before data analysis, the accuracy of returned transcripts was checked (by ED) by randomly selecting five transcripts and comparing these against the original audio recordings.

Instruments

Quantitative materials

Facilitator participant survey

All facilitators completed a participant survey which asked questions about their demographic characteristics (e.g. gender, age, Indigeneity, the highest level of educational attainment and employment status) and level of facilitator experience (e.g. ‘how many groups have you facilitated since completing the training?’). A five‐point Likert scale (never to always) was used to identify which and how frequently SMART Recovery program tools were used. For example, facilitators were asked to rate how often they used ‘goal setting with group members’.

Group member participant survey

Each group member completed a survey which asked questions to obtain their demographic characteristics (e.g. gender, age, Indigeneity, the highest level of educational attainment and employment status) and identify their patterns of and motivations for attending groups, concurrent recovery treatments and experiences with other mutual support group programs. The same five‐point Likert scale (never to always) was used to identify which and how frequently they used SMART Recovery program tools within their groups (e.g. ‘goal setting’). An additional question asked group members to identify what ‘tools’ they ‘leave SMART Recovery meetings with’.

Group observations

Group observations were conducted to identify each group's characteristics and operational processes. An observation protocol was created that involved positioning the researcher (ED) as an observer‐participant [54] and administration of a purposefully‐designed SMART Recovery program adherence checklist with hand‐recorded field notes to obtain comparable descriptive accounts.

SMART Recovery program adherence checklist

The SMART Recovery program adherence checklist (‘checklist’; see Supporting Information) was designed as an 18‐item inventory of the SMART Recovery program protocol. The checklist also allowed for easy identification of the seven‐core program ‘tools’. The checklist was arranged according to the program's recommended sequence of implementation. Items were scored as either ‘yes = 1’ (item was present) or ‘no = 0’ (item was absent). Adherence scores were interpreted as high (80–100%), moderate (51–79%) or low (0–50%) [55].

Content validity for the checklist was established using a three‐stage process [56]: (i) items were selected following a review of SMART Recovery literature and program materials; (ii) the checklist was co‐created with SMART Recovery program coordinators located in their Australian head office; and (iii) review and approval of checklist through consensus agreement by the SMART Recovery Australia Research Advisory Committee.

Before data collection, the checklist was piloted for accuracy and reliability (by PK and ED; each SMART Recovery trained facilitators) by observing and rating a non‐Aboriginal‐led SMART Recovery meeting. The group facilitator was shown the checklist on conclusion of the group, when they were asked to complete a self‐rating. Inter‐rater reliability was calculated as a percentage of agreement between the three raters (PK, ED and the facilitator). An inter‐rater reliability score of 100% was achieved (see Supporting Information).

Field notes

Hand‐recorded field notes were systematically recorded (by ED) to accompany the checklist. Field notes recorded program modifications or deviations. Culturally specific variations (e.g. language or delivery style) would be identifiable through this process [57].

Qualitative materials

Research topic yarning

Separate yarning guides were developed to support the yarns with facilitators and members. These guides were piloted (by ED and a local Aboriginal Elder). Both yarning guides contained core questions to explore perceived cultural acceptability and helpfulness of SMART Recovery and suggestions for improvements. For example, group members were asked: ‘Do you feel that the SMART recovery model is a fit with your Aboriginal culture?’; ‘How could SMART Recovery be better for Aboriginal people?’

Facilitators were also asked to describe their experiences of the SMART Recovery facilitator training process (e.g. ‘What was it like as an Aboriginal person completing the SMART Recovery training?’; ‘How would you describe what it's like to be an Aboriginal person facilitating SMART recovery groups?’).

Data analysis

Quantitative analysis

Descriptive analysis was conducted of survey data and fieldnote recordings. Data from the adherence checklist were tabulated to calculate an overall program adherence rating score for each group. This involved dividing the number of items adhered to by the total number of possible checklist items (maximum score of 18). Total scores were then converted into a percentage. Data were then tabulated to enable an item‐by‐item level evaluation of common group features and operational processes.

Qualitative analysis

All qualitative data were imported into NVivo version 12 for thematic analysis. (by ED) [58]. This involved an initial coding phase followed by a focused phase, with simultaneous comparison with the quantitative data to assist with theme development [58]. A matrix was used to categorise emergent themes and collapse these into key themes and sub‐themes [59]. All transcripts and field notes were checked for coding (by KL) and discussed (ED, KL) to reach consensus.

To mitigate bias, field notes were recorded as soon as possible after group observations. Then, field notes were rechecked (by ED) and discussed with another author (KL). Contact was maintained with some facilitators (by ED) throughout analysis to feedback and reflect on emerging themes.

Data from each of the five participating Aboriginal communities (i.e. yarning transcripts, participant surveys and for the three groups, observation results) were then grouped and regarded individually so that their unique storylines could be appreciated prior to amalgamation into a final data pool [60]. This approach acknowledges the need to consider cultural and environmental diversity when developing and disseminating research knowledge [35, 61, 62].

Results

Facilitator attributes

Facilitators were mostly male (n = 7/10) and their mean age was 50.5 years (SD = 9.7; Table 1). All identified as Aboriginal. Most of the facilitators (n = 7/10) were actively running groups and of these, three (n = 3/7) ran more than one group each week. More than half of the facilitators (n = 6/10) co‐facilitated their SMART Recovery group. Facilitators each held a range of educational and professional qualifications. The majority had completed year 12 or below (at school; n = 8/10) and had gained health‐related tertiary certificate or diploma level (n = 8/10) qualifications (e.g. in alcohol and other drugs counselling). Professional backgrounds included plumbing, security, religious ministry and construction work.

Group member attributes

All group members (n = 11) currently attended an Aboriginal‐led SMART Recovery group (Table 2). There was minimal difference between group member ages and genders; women (n = 6/11; mean age 37.09, SD = 9.45) and men (n = 5/11; mean age 39.6, SD = 12.5) and most identified as Aboriginal (n = 9/11). Two members identified as being of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander descent. All but one member attended voluntarily (n = 1; court mandated). Just over a third (n = 5/11) had attended a group in the past 2–4 weeks (at the time of yarn). Nominated reasons for attending groups included problematic alcohol use (n = 1/11), illicit drug use (n = 5/11), combined alcohol and illicit drug use (n = 3/11) and relapse prevention (n = 1/11). One member was attending the group to learn how to support a close relative.

Characteristics of observed Aboriginal‐led SMART Recovery groups

All Aboriginal‐led SMART Recovery groups (n = 3) were offered weekly in a primary health‐care service (Table 3). Two groups were located in an Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation. The average length of time groups had operated for was 10.3 weeks and the duration of meetings was just over an hour (mean: 63.5 min, SD = 4.7). All groups were open to people aged 16+. One group (urban; SA) was offered to both Aboriginal and non‐Aboriginal peoples. Another group (remote; SA) was for females only.

Program adherence ranged from 44% to 55% (Table 4). Of the 18 program adherence items, just four were performed consistently across each group (i.e. member ‘check in’, use of discussion time to ‘generate ideas’ and share lived experiences, and a formal group closure). Of the seven core SMART Recovery tools, just two were used, ‘goal setting’ and ‘problem solving’.

Table 4.

Distribution of program items that were observed for each group

| Adherence checklist itema | Group 1 (rural NSW) | Group 2 (remote SA) | Group 3 (urban SA) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Opening protocols | |||

| Welcome statement | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Acknowledgment of country | ✓ | ||

| Description of SMART Recovery | ✓ | ||

| Group rules and guidelines | ✓ | ✓ | |

| ‘Here and now’ perspective | |||

| Meeting format explained | |||

| Check in | |||

| Each member checks in | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Members identify a problem to discuss | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Check in is brief and balanced | ✓ | ||

| Group discussion | |||

| Members can address their problem | ✓ | ||

| Group idea generation | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Members input shared experiences | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Members set a 7‐day plan | ✓ | ||

| Use of core program tools | ✓b,c | ✓ | ✓c |

| Check out and close | |||

| Each member checks out | |||

| Members summarise what they learned | |||

| Members state their 7‐day plan | |||

| Facilitator formally closes group | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Program adherence score (%) | 55 | 44 | 44 |

Checklist items have been summarised from the original instrument. b Goal setting. c Problem solving. NSW, New South Wales; SA, South Australia.

Facilitator and group member survey results were not consistent with each other, or with program adherence checklist scores. During the group observations (n = 3), the adherence checklist identified one group (n = 1/3) that used ‘goal setting’, while two groups (n = 2/3) utilised ‘problem solving’. In contrast, all facilitators (n = 10) reported they ‘always’ use ‘goal setting’ and just over half of group members (n = 7/11) reported that ‘goal setting’ was ‘always’ used during groups. Also, while all facilitators reported via survey that their meetings ‘always’ used problem solving, just under a quarter of group members (27%; n = 3/11) reported that they ‘always’ engaged in problem solving. Just over half of group members reported that they leave each meeting having learned new skills and ideas (n = 6/11).

Perceived acceptability and helpfulness of SMART Recovery

Facilitators

During the yarns, all facilitators said while they liked the concept of SMART Recovery (i.e. empowering people to make behaviour change) they felt that the program needed ‘tweaking’ to better suit the cultural and practical needs of their local community.

‘At the time when I completed the training I thought, well this will work, particularly if you adapt it and make it a bit more culturally appropriate’. (male facilitator, 65 years)

‘[the way they wanted us to run meetings] was just too non‐Indigenous, too formal, and really direct questions. Where [our yarning approach] is more informal and more open… [we want our clients] to feel comfortable and express themselves’. (male facilitator, 38 years)

‘The other thing that I have used are picture cards in my group’. (female facilitator, 54 years)

‘I was concerned that some of the language wasn't necessarily able to be understood by older members or older clients … [I also modified] the language, delivery style … [and] where it was delivered’. (male facilitator, 65 years)

From a cultural perspective, facilitators felt that the SMART Recovery program was too ‘formal’ and ‘strict’. They all felt it needed less clinical language, more Aboriginal specific health‐promoting resources and a relaxed ‘yarning circle’ meeting style, which would enable them to facilitate a ‘recovery‐focused yarn’ (‘recovery yarn’) Facilitators hosting groups within an Aboriginal community‐controlled health organisation (n = 6) described how the provision of practical and wrap around health services offered additional member benefits:

‘Like the clients I bring, if I don't transport them, they don't come. It's just as simple as that, [many of them] just don't have transport … one of the participants [was] saying today, [coming to group has been] a whole change of lifestyle for them … we're doing the right thing, and it's very successful’. (male facilitators, 52 years)

‘They come here, do SMART Recovery … they get to see the doctors, you know; like last week a lot of them with their goal was to get back on medication. So, they finish SMART Recovery, go over and make a doctor's appointment. So, the holistic approach of it, really works.’ (male facilitator, 42 years)

‘A lot of success comes because its connected to [our Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation] and all the other wrap around services.’ (male facilitator, 38 years)

Group members

During the yarns, all group members said what they liked most about SMART Recovery was the avoidance of labels (i.e. alcoholic), and the opportunity to learn practical, recovery‐orientated tools and strategies (e.g. goal setting), and to problem solve with people ‘in a similar situation’:

‘[I like that SMART Recovery] is non‐judgemental. It's harm‐minimisation based. It's realistic, in that the focus is on self‐management. Attainable goals, you know.’ (male facilitator, 34 years)

‘I like the fact that I don't have to call myself an addict. I think the fact that it's problem solving and setting your own goals’.(female member, 37 years)

‘I like being able to have the social support … I look forward to [coming to group], when I come, because I know … it's going to be safe today’. (female member, 22 years)

Group members described the group as ‘relaxed’ and ‘comfortable.’ They saw meetings as a ‘safe’ place to ‘talk out’ problems without ‘judgement’ or ‘shame’:

‘It's pretty comfortable coming here … you're not obligated to talk; you can just come here and relax … just be around people in a similar situation … I like it … It's easy going, you're not pressured to do anything.’ (male member, 22 years)

‘[There can be] a shamefulness of addressing situations … where [this meeting has been made] more blackfella friendly [more] open’. (male member, 44 years)

All group members described how a safe group environment was important for building peer connections and facilitating sharing of similar lived experiences and advice:

‘I like the fact that it's a relaxed environment. I like the fact it's only a small group and that we're all going through something different, so we can give each other new ideas or ways to help…we can ask each other for advice and work out some new ideas and new supports’ (female member, 40 years)

This sense of connectedness, described as ‘accountability’, appeared to give all group members motivation to ‘stay on track’ and attend regularly:

‘I think talking anything out is helpful. Even if nothing changes, talking it out kind of lessens the shame and makes me a bit accountable … If I say what my goal is, the next week, I've got to say if I've achieved that or not. So that's good’. (female member, 37 years)

‘I set a goal every week here and then I try and accomplish it before I come back’.(male member, 22 years)

‘[The SMART Recovery meeting help] keeps me on the straight and narrow’. (male member, 57 years)

Regular group attendance was described by group members as having broader community benefits. Nearly half (n = 6/13) saw themselves as role models for positive health‐seeking behaviour while a majority (n = 8/13) felt that the skills and knowledge learned during the program could be passed down to younger generations:

‘[I want to get better] to show other people how to get better…I want to show what you can do. That's the whole reason [I attend SMART Recovery]’. (male member, 22 years)

‘There's young people out there…using amphetaminesand I'd like to teach them and show them that's not good, it's not cool’. (female member, 37 years)

Suggested areas for improvement

Participants offered a range of practical suggestions that if adopted by SMART Recovery, could enhance its cultural utility for Aboriginal communities:

‘Go back to [SMART and say this is what we need] … In the handouts and stuff, [we need these to be] more aware of how Indigenous people live [and have] stuff [in] there about culture and a little bit of tradition and stuff like that, you know, so people can relate to it when they're looking at it. [And] the contents have got to assist the delivery of it, [for example] it don't have to be so formal… it can be delivered better [it needs] to be adapted and be more adaptable to our people’. (male facilitator, 42 years)

The participants' suggestions for improvement were categorised into four key areas: implementing Aboriginal perspectives into the facilitator training; Aboriginal‐specific program materials; community engagement, marketing and networking; and establishment of an Aboriginal SMART Recovery program (Table 5).

Table 5.

Suggested improvements from Aboriginal facilitators and group members for the SMART Recovery program

| Theme and sub‐themes | Quotes |

|---|---|

| 1. Integrate Aboriginal perspectives into the facilitator training | |

| Knowledge of socio‐economic, cultural and historical determinants underlying Aboriginal people's experiences with substance use and problematic behaviours |

‘We're talking about layers, and layers of colonial trauma and pain …. we're talking about a difficult space where Aboriginal people are still not recognised equally … don't have justice … don't have inclusion … are we healing, are we recovering; what does that mean? because recovery to our people it's a multitude of things, and what's underneath … there's so much there underneath’. (female facilitator, 63 years) ‘I think more [training is needed] about the underlying issues. So why they have an addiction in the first place? What are they clouding by using alcohol and drugs? …. Stolen Generation … loss of culture … trauma … all those things’. (female facilitator, 47 years) ‘And then go back to like the guys that do the training, if they're … more aware of how Indigenous people live and how, you know, it can be delivered better to adapt to be more adaptable to our people’. (male facilitator, 42 years |

| Understanding of Aboriginal views of health and wellbeing | ‘Non‐Aboriginal people don't have the same world view. They don't see the world in the same way that we do [for example there's our] intergenerational trauma, there's reasons – I believe there's reasons why I'm like this’. (female member, 44 years) |

| Need Aboriginal trainers to design and deliver training | ‘I think they [need] an Aboriginal … to train us up so we can run it culturally appropriate for our mob [that] would be great!’ (male facilitator, 57 years) |

| 2. Create Aboriginal‐specific program materials | |

| Co‐creation in consultation and collaboration with Aboriginal communities | ‘You need to sit down with a group of Elders, and you get their input, you get their understanding of what they want for their community and for their mobs’. (male facilitator, 57 years) |

| Use Aboriginal artwork and relatable narratives | ‘[an Aboriginal workbook is needed] … definitely [with] visual material. So, if things have got pictures … and Aboriginal designs on it, it's going to make them feel more comfortable just to start with. It's inviting’. (female facilitator, 54 years) |

| Avoid clinical language and be written with sensitivity for a variety of literacy levels | ‘I was concerned that some of the language wasn't necessarily able to be understood by older members or older clients that might participate’. (male facilitator, 65 years) |

| Contain activities that promote healthy cultural identities and foster stronger connections to community and culture | ‘We want to do more, we should be able to do more, instead of just talking we should be able to [do cultural] activities … [and] it helps writing something down … try and make it easier’. (male member, 22 years) |

| 3. Community engagement, marketing and networking | |

| Establish a better presence and reputation in the community to increase Aboriginal attendance. This would be achieved by promoting itself via culturally inviting online and social media opportunities, and via face‐to‐face networking. |

‘For our Mob, they're just not getting there … they don't know enough about it. It's not advertised in their area’. (female facilitator, 63 years) ‘I think getting out [to the] smaller rural and remote areas is really important and continue going out. Not just go out and do one workshop … and they need to put more on the website … when you go online, have a look at SMART Recovery's Australia, there's nothing really there for Aboriginal people’. (female facilitator, 54 years) ‘[SMART Recovery's could be made better for our community] with more promotion … because it's not very well promoted … and that's why we've only got a few people’. (female member, 40 years) |

| 4. Establish an Aboriginal SMART Recovery program | |

| Flexibility to allow for customisation and localisation by diverse community groups without jeopardising the model's outcomes | ‘The yarning … that's a really important aspect of, if people look at redoing SMART Recovery, it really [needs to] have a yarning aspect … and I think in its current format it depends on the facilitator being enabled to adapt it and deliver it at a culturally appropriate manner, while still meeting the outcomes or the guidelines to how it's supposed to be run'. (male facilitator, 65 years) |

| Retain the ‘concept’ of SMART Recovery's (i.e. problem solving, goal setting, harm minimisation approach) | ‘You still have the concept of SMART Recovery you're getting to, you know, like their weekly goals and what they want to achieve, just in a less formal approach’. (male facilitator, 57 years, rural NSW) |

| Inclusion of Aboriginal health resources and tools | ‘There's nothing cultural in [in the current workbooks]’ (female member, 37 years) |

| Delivered as a yarning circle; ‘Check in’, Recovery yarn, ‘checkout’ | ‘[an Aboriginal SMART Recovery would be] a yarning circle with a difference, you know what I mean?’. (male facilitator, 53 years) |

| Avoid clinical language | ‘I worry about some of the language … you know, even referring to things like specific, measurable, attainable. You know, I just worry that it would [not be understood by everyone] … I [use the term from the Aboriginal stages of change version] not worried, [instead of the clinical term] abstinence’. (male facilitator, 34 years) |

| Provision of practical assistance (e.g. food, transport) | ‘[food is important because] probably [a lot of them] don't eat for days or weeks at a time. So, if I put a feed on for them, bit of nutrition, bit of education, bit of unloading … drive the bus … [you'll] get more people in’. (male facilitator, 53 years) |

| Establish an Aboriginal facilitators support network | ‘Have like an Aboriginal facilitator support group. That could be something, whether it be online … [to share information and support]. (female facilitator, 54 years) |

Discussion

This is the first study to explore the cultural utility of SMART Recovery for Aboriginal peoples in Australia. Western and Indigenous research methodologies were synthesised to explore the experiences and perceptions of Aboriginal facilitators and group members and to observe three Aboriginal‐led SMART Recovery groups. We found that Aboriginal‐led SMART Recovery groups were operating as culturally customised versions of the original program. Customisations included a yarning circle style of facilitation, deliberate omissions from the core program ‘tools', supplementation with Aboriginal‐specific program resources and (for groups run within Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisations) integration of groups with a holistic model of care. These differences, together with recommended program improvements, offer SMART Recovery practical ways to enhance their cultural utility for Aboriginal Australians.

Adaptations to facilitation styles and core program features

All groups were observed and reported by facilitators via yarning and surveys to be operating in ways that maintained the ‘concept’ of SMART Recovery (i.e. emphasis on shared experiential learning and use of goal setting and problem solving to encourage behaviour change). However, groups were delivered via a traditional yarning circle (as opposed to the prescribed ‘meeting agenda’) [63]. Yarning circles are a relational and culturally appropriate forum for storytelling, knowledge sharing and learning [64]. When used in a psychosocial context, yarning circles have been shown to improve health‐related outcomes [47] in drug and alcohol recovery [65] and in mental health care [66]. As shown via the program adherence checklist, the aspects of the SMART Recovery meeting agenda that were retained by all facilitators (i.e. the ‘check in,’ group problem‐solving discussion and ‘check out’) [17] are similar to traditional yarning circle protocols (i.e. group introductions, reciprocal discussion and formal group closure) [63]. This finding suggests that these program aspects hold cultural value and could be a suitable way to facilitate SMART Recovery groups for Aboriginal peoples.

The inclusion of Aboriginal‐designed psycho‐educational resources (e.g. Aboriginal ‘picture cards’) [67] enabled facilitators to introduce Aboriginal perspectives to health and wellbeing. Similar adaptations have been made by Native American Indian peoples to improve the cultural utility of Alcoholics Anonymous [27]. In one such example, Western religious‐based acts and prayers were replaced with ‘Indian practices’ such as drumming, smudging ceremonies and traditional prayers [68] and medicine wheel teachings were incorporated into group meetings [69].

During the yarns, both facilitators and group members identified a range of positive outcomes from attending groups that were consistent with previous SMART Recovery outcome studies: reduced substance use [18, 19], recovery skills acquisition (e.g. ‘goal setting’ and ‘problem solving’) [15], being able to establish social support networks [20] and improved quality of life [21]. However, there was discrepancy between facilitator and group member survey responses and the adherence checklist in terms of how frequently ‘goal setting’ and ‘problem solving’ were used. Group member yarns were in full agreement that ‘goal setting’ and ‘problem solving’ were the only two program ‘tools’ (of seven available) that they liked. This finding is consistent with a previous study [14] of a national sample of non‐Aboriginal facilitators (n = 65) and group members (of which 6.5% were Aboriginal) [14, 70]. However, in contrast to this national study [14], we did not find any evidence via yarning, surveys or group observations that the remaining core program tools were utilised or perceived as helpful (i.e. ‘change plan’, ‘cost benefit analysis’, ‘role play’, ‘thoughts, feelings, and actions plays’, or ‘urge log’) [15]. Future research could identify barriers to implementation or additional cultural‐specific tools that could enhance the cultural utility of SMART Recovery from the perspective of Aboriginal facilitators. The degree to which reductions to the core program tools could jeopardise the therapeutic integrity [71] of SMART Recovery also warrants further investigation.

Groups that were hosted in an Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation (n = 6) offered members easy access to a variety of ‘wrap‐around’ health services that are often needed during recovery from substance use disorders (e.g. counselling and medical health services) [72, 73]. The provision of transport was also demonstrated as necessary for helping Aboriginal people overcome social and economic barriers that might otherwise impede group attendance [74, 75].

A unique outcome of this study was the finding that all group members described broader community benefits associated with their SMART Recovery attendance (e.g. opportunities to be a positive role model in the community, and to obtain information to educate younger generations). This has particular significance for Aboriginal Australians who regard the ‘self’ as communal [76] and derive their health and wellbeing via their connections with each other [77].

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, the average time taken to complete the participant surveys was not recorded. However, time was set aside to facilitate survey data collection such that group members and facilitators did not feel rushed. Second, observational data denoting the characteristics of Aboriginal‐led groups were derived from one‐off observations of just three Aboriginal‐led SMART Recovery groups. Similarly, our small group participant sample size restricts study conclusions. Although our participants represented three regionally diverse Aboriginal communities across two Australian states, more research is needed with more Aboriginal‐led groups and Aboriginal facilitators and group members of other communities to corroborate these findings. This line of research would be enhanced by employing community‐based participatory research methods [78] and longer‐term, ethnographic investigations [79].

The perspectives of Aboriginal people attending mainstream groups are also needed to contrast with these findings. Moreover, future research to investigate the cultural utility of SMART Recovery Australia's online support group service would be important especially with regards to the current global coronavirus pandemic and ensuing social isolation regulations. Third, this study did not measure the groups' effectiveness for reducing members' substance use. Measures of group effectiveness are therefore needed to understand which aspects of Aboriginal‐led groups are linked to improved health outcomes.

Last, the SMART Recovery program adherence checklist, while designed with SMART Recovery Australia head office and their research committee, has only been used in this study. Future work to validate this checklist would enable SMART Recovery to detect effective program aspects and the circumstances under which they can be most reliable [80]. Such an instrument could be used to both monitor the program's treatment fidelity and also to help ensure it is meeting the needs of diverse cultural groups.

Implications

This study has implications for the future planning and development of SMART Recovery to be more accessible and acceptable for Aboriginal Australians. The mainstream SMART Recovery program could either be adjusted to suit local Aboriginal contexts or an Aboriginal‐specific SMART Recovery program could be developed. Either option would need to be guided by Aboriginal leadership from the outset and be co‐designed with community members.

To extend this study, we are engaging in a modified Delphi process [81, 82] to obtain guidance from Aboriginal experts on how SMART Recovery could be adapted to enhance cultural utility of this program's handbook for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander facilitators and group members. This study will demonstrate how Indigenous knowledges and expertise can be embedded into an existing mutual support group program and could benefit Indigenous communities more globally.

Conclusions

This study offers first insights into Aboriginal peoples' experiences of SMART Recovery. Culturally informed modifications to the program were identified that could enhance the cultural utility of SMART Recovery for Aboriginal Australians. Future research is needed to obtain diverse community perspectives and measure health outcomes associated with attendance in Aboriginal‐led groups.

Conflicts of Interest

ED and PK are members of the SMART Recovery Australia Research Advisory Committee. ED became a member in June 2020, after all data collection and analysis was complete for this study. PK had no part in data analysis. SMART Recovery had no part in design, analysis or write up of this study. ED and PK were not involved in the running of any of the groups that were observed.

Supporting information

Appendix S1. SMART Recovery program adherence checklist.

Appendix S2. SMART Recovery program adherence checklist inter‐rater reliability calculations.

Acknowledgements

This study was made possible through collaborative partnerships with Aboriginal communities, individuals and organisations across New South Wales and South Australia. The authors would like to acknowledge and pay respect to the traditional custodians of these lands, to creator God, Elders past, present and future and the Indigenous voices that are represented herein. We appreciate the help from Dr Angela Argent from SMART Recovery Australia by equipping us with SMART Recovery Australia resources and manuals, providing ED with free SMART Recovery facilitator training and being our key liaison person. This research has been conducted with the support from an Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship and the University of Wollongong (for ED). We also acknowledge the support from the National Health and Medical Research Council via the Centre of Research Excellence in Indigenous Health and Alcohol (#1117198; for ED) and a Practitioner Fellowship for KCo (#1117582).

Elizabeth Dale, Doctor of Philosophy (Clinical Psychology), Psychologist, KS Kylie Lee PhD, Associate Professor, Deputy Director, Adjunct Associate Professor, Visiting Research Fellow, Katherine M. Conigrave PhD, Addiction Medicine Specialist, Professor, Director, James H. Conigrave PhD, Research Fellow, Rowena Ivers MBBS, FRACGP, Associate Professor, Kathleen Clapham PhD, Professor (Indigenous Health) and Director, Peter J. Kelly PhD, Associate Professor, Deputy Head of School (Research), School of Psychology.

References

- 1.Dawson DA, Grant BF, Stinson FS, Chou PS. Estimating the effect of help‐seeking on achieving recovery from alcohol dependence. Addiction 2006;101:824–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hing N, Breen H, Gordon A, Russell A. The gambling behavior of Indigenous Australians. J Gambl Stud 2014;30:369–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Public Health England . Improving mutual aid engagement: A professional development resource. London: Public Health England, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kelly JF, Magill M, Stout RL. How do people recover from alcohol dependence? A systematic review of the research on mechanisms of behavior change in Alcoholics Anonymous. Addict Res Theory 2009;17:236–59. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration . An introduction to mutual support groups for alcohol and drug abuse. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Rockville, MD: SAMHSA's National Clearinghouse for Alcohol and Drug Information, 2008:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Theurer K, Wister A, Sixsmith A, Chaudhury H, Lovegreen L. The development and evaluation of mutual support groups in long‐term care homes. J Appl Gerontol 2014;33:387–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kelly JF, Humphreys K, Ferri M. Alcoholics Anonymous and other 12‐step programs for alcohol use disorder. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2020;3:CD012880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Binde P. A Swedish mutual support society of problem gamblers. Int J Ment Health Addict 2012;10:512–23. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sanders JM. Use of mutual support to counteract the effects of socially constructed stigma: gender and drug addiction. J Groups Addict Recover 2012;7:237–52. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tonigan JS, Connors GJ, Miller WR. Special populations in Alcoholics Anonymous. Alcohol Health Res World 1998;22:281–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.SMART Recovery . About SMART Recovery 2019. Available at: https://www.smartrecovery.org/about-us/.

- 12.SMART . Recovery Australia. SMART Recovery Australia – About Us 2020. https://smartrecoveryaustralia.com.au/about/smart-recovery-australia/. [Google Scholar]

- 13.SMART Recovery Australia . On line SMART Recovery meetings: SMART Recovery Australia 2020. Available at: https://smartrecoveryaustralia.com.au/online-smart-recovery-meetings-2/.

- 14.Kelly PJ, Raftery D, Deane FP, Baker AL, Hunt D, Shakeshaft A. From both sides: Participant and facilitator perceptions of SMART Recovery groups. Drug Alcohol Rev 2017;36:325–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Horvath AT, Yeterian JD. SMART Recovery: Self‐empowering, science‐based addiction recovery support. J Groups Addict Recover 2012;7:102–17. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Beck AK, Baker AL, Kelly PJet al. Protocol for a systematic review of evaluation research for adults who have participated in the ‘SMART recovery’ mutual support programme. BMJ Open 2016;6:e009934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.SMART Recovery Australia . In: Freeman J, ed. SMART Recovery Facilitator Training Manual: Practical information and tools to help you facilitate a smart recovery group. Sydney, Australia: SMART Recovery, 2015:14–5. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beck AK, Forbes E, Baker ALet al. Systematic review of SMART Recovery: outcomes, process variables, and implications for research. Psychol Addict Behav 2017;31:1–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Milin M. Which types of consequences of alcohol abuse are related to motivation to change drinking behavior? The Sciences and Engineering [Internet] 2007:68. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hester RK, Lenberg KL, Campbell W, Delaney HD. Overcoming Addictions, a Web‐based application, and SMART Recovery, an online and in‐person mutual help group for problem drinkers, part 1: three‐month outcomes of a randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res 2013;15:e134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Raftery D, Kelly PJ, Deane FP, Baker AL, Dingle G, Hunt D. With a little help from my friends: Cognitive‐behavioral skill utilization, social networks, and psychological distress in SMART Recovery group attendees. J Sub Use 2020;25:56–61. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brooks AJ, Penn PE. Comparing treatments for dual diagnosis: twelve‐step and self‐management and recovery training. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse 2003;29:359–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dale E, Kelly PJ, Lee KSK, Conigrave JH, Ivers R, Clapham K. Systematic review of addiction recovery mutual support groups and Indigenous people of Australia, New Zealand, Canada, the United States of America and Hawaii. Addict Behav 2019;98:106038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beals J, Novins DK, Spicer P, Whitesell NR, Mitchell CM, Manson SM. Help seeking for substance use problems in two American Indian reservation populations. Psychiatr Serv 2006;57:512–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Herman‐Stahl M, Chong J. Substance abuse prevalence and treatment utilization among American Indians residing on‐reservation. Am Indian Alsk Native Ment Health Res 2002;10:1–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kenny MC. An integrative therapeutic approach to the treatment of a depressed American Indian client. Clin Case Stud 2016;5:37–52. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Spicer P. Culture and the restoration of self among former American Indian drinkers. Soc Sci Med 2001;53:227–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brady M. Culture in treatment, culture as treatment. A critical appraisal of developments in addictions programs for indigenous North Americans and Australians. Soc Sci Med 1995;41:1487–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shakeshaft A, Clifford A, Shakeshaft M. Reducing alcohol related harm experienced by Indigenous Australians: identifying opportunities for Indigenous primary health care services. Aust N Z J Public Health 2010;34:S41–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Walker M, Fredericks B, Mills K, Anderson DJ. “Yarning” as a method for community‐based health research with indigenous women: the indigenous women's wellness research program. Health Care Women Int 2014;35:1216–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Leske S, Harris MG, Charlson FJet al. Systematic review of interventions for Indigenous adults with mental and substance use disorders in Australia, Canada, New Zealand and the United States. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2016;50:1040–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee KS, Dawson A, Conigrave KM. The role of an Aboriginal women's group in meeting the high needs of clients attending outpatient alcohol and other drug treatment. Drug Alcohol Rev 2013;32:618–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gray N, Mays MZ, Wolf D, Jirsak J. A culturally focused wellness intervention for American Indian women of a small southwest community: Associations with alcohol use, abstinence self‐efficacy, symptoms of depression, and self‐esteem. Am J Health Promot 2010;25:e1–e10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kawakami AJ, Aton K, Cram F, Lai M, Porima L.Improving the practice of evaluation through indigenous values and methods. Illustrated ed: Honolulu, HI: Guilford Press; 2008. 219–42 p. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zavala M. What do we mean by decolonizing research strategies? Lessons from decolonizing, Indigenous research projects in New Zealand and Latin America. Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society [Internet] 2013;2:55–71. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Johnson‐Jennings M, Jennings D, Little M. Indigenous data sovereignty in action: The food wisdom repository. J Indig Wellbeing 2019;4:26–38. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stange KC, Crabtree BF, Miller WL. Publishing multimethod research. Annals Family Med 2006;4:292–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Walter M. Social Research Methods. Melbourn, Victoria: Oxford University Press, 2010:501. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Durie M. Understanding health and illness: research at the interface between science and Indigenous knowledge. Int J Epidemiol 2004;33:1138–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sherwood J, Edwards T. Decolonisation: A critical step for improving Aboriginal health. Contemp Nurse 2006;22:178–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wilson S. What is an Indigenous research methodology? Canadian J Native Education [Internet] 2001;25:175–9. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rigney LI. Internationalisation of an Indigenous anti‐colonial cultural critique of research methodologies: A guide to Indigenous research methodology and its principles. J Nat Am Studies, WICAZO Sa Review 1997;14:109–21. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Foley D. Indigenous standpoint theory: an acceptable academic research process for indigenous academics. Int J Humanit 2006;3:25–36. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Phellas CN, Bloch A, Seale C. Structured methods: interviews, questionnaires and observation. Researching society and culture, Vol. 3. London ECIY ISP: Sage publications LTD, 2011:181–205. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Spradley JP. Participant observation. Long Grove: Il Waveland Press, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bessarab D, Ng'andu B. Yarning about yarning as a legitimate method in Indigenous research. Int J Crit Indig Stud 2010;3:37–50. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lin I, Green C, Bessarab D. Yarn with me: applying clinical yarning to improve clinician–patient communication in Aboriginal health care. Aust J Prim Health 2016;22:377–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hamilton SL, Maslen S, Best Det al. Putting ‘justice’ in recovery capital: Yarning about hopes and futures with young people in detention. Int J Crime Justice Soc Democr 2020;9:20–36. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Johnson RB, Onwuegbuzie AJ. Mixed methods research: A research paradigm whose time has come. Educ Res 2004;33:14–26. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vellinga A, Cormican M, Hanahoe B, Bennett K, Murphy AW. Opt‐out as an acceptable method of obtaining consent in medical research: a short report. BMC Med Res Methodol 2011;11:40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bazeley P, ed. Keynote Speech 2: A Mixed Methods Way of Thinking and Doing: Integration of Diverse Perspectives in Practice Mixed Methods Research International Symposium. Aogaku, Japan: Aoyama J Int Studies, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Withall J, Jago R, Fox K. Why some do but most don't. Barriers and enablers to engaging low‐income groups in physical activity programmes: a mixed methods study. BMC Public Health 2011;11:1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fredericks B, Clapham K, Bessarab Det al. Developing pictorial conceptual metaphors as a means of understanding and changing the Australian Health System for Indigenous People. ALARA: Action Learn 2015;21:77–107. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Creswell JW. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches, Third edn. California, USA: SAGE Publications, Inc, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Toomey E, Matthews J, Hurley DA. Using mixed methods to assess fidelity of delivery and its influencing factors in a complex self‐management intervention for people with osteoarthritis and low back pain. BMJ Open 2017;7:1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zamanzadeh V, Ghahramanian A, Rassouli M, Abbaszadeh A, Alavi‐Majd H, Nikanfar AR. Design and Implementation Content Validity Study: Development of an instrument for measuring Patient‐Centered Communication. J Caring Sci 2015;4:165–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Carroll C, Patterson M, Wood S, Booth A, Rick J, Balain S. A conceptual framework for implementation fidelity. Implement Sci 2007;2:40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 2006;3:77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Averill JB. Matrix analysis as a complementary analytic strategy in qualitative inquiry. Qual Health Rese 2002;12:855–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mills J, Bonner A, Francis K. The development of constructivist grounded theory. Int J Qual Methods 2006;5:25–35. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Smith LT. Decolonizing methodologies: research and Indigenous peoples. second edition ed. London and New York: Zed Books Ltd, 2012:240. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wilson S. Research is ceremony: Indigenous research methods, illustrated edn. Canada: Fernwood Publishing, 2008:144. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Queensland Government . Yarning circles [Resources]. 2018. [updated 25.07.2018. Available at: https://www.qcaa.qld.edu.au/about/k-12-policies/aboriginal-torres-strait-islander-perspectives/resources/yarning-circles.

- 64.Mills KA, Sunderland N, Davis‐Warra J. Yarning circles in the literacy classroom. Read Teach 2013;67:285–9. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Towney LM. The power of healing in the yarns: Working with Aboriginal men. Int J Narrative Therapy Commun Work 2005;1:39–43. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Vicary D, Bishop B. Western psychotherapeutic practice: Engaging Aboriginal people in culturally appropriate and respectful ways. Aust Psychol 2005;40:8–19. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Simmons T, Conway S. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Stages of Change Story Titjikala community. Australia: Northern Territory Government, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Coyhis D, Simonelli R. The Native American healing experience. Subst Use Misuse 2008;43:1927–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Coyhis D, Simonelli R. Rebuilding Native American communities. Child Welfare 2005;84:323–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Robinson LD, Kelly PJ, Deane FP, Reis SL. Exploring the relationships between eating disorders and mental health in women attending residential substance use treatment. J Dual Diagn 2019;15:270–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Breitenstein SM, Gross D, Garvey CA, Hill C, Fogg L, Resnick B. Implementation fidelity in community‐based interventions. Res Nurs Health 2010;33:164–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.McLellan AT. Have we evaluated addiction treatment correctly? Implications from a chronic care perspective. Addiction 2002;97:249–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Vanderplasschen W, Colpaert K, Autrique Met al. Therapeutic communities for addictions: a review of their effectiveness from a recovery‐oriented perspective. Sci World Journal 2013;2013:427817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Jennings W, Spurling GK, Askew DA. Yarning about health checks: barriers and enablers in an urban Aboriginal medical service. Aust J Prim Health 2014;20:151–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Gray D, Wilson M, Allsop S, Saggers S, Wilkes E, Ober C. Barriers and enablers to the provision of alcohol treatment among Aboriginal Australians: A thematic review of five research projects. Drug Alcohol Rev 2014;33:482–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Berry JW. Aboriginal cultural identity. Canada: Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples, 1994;1–36. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Dudgeon P, Bray A, D'Costa B, Walker R. Decolonising Psychology: validating social and emotional wellbeing. Aust Psychol 2017;52:316–25. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Tobias JK, Richmond CA, Luginaah I. Community‐based participatory research (CBPR) with indigenous communities: producing respectful and reciprocal research. J Empir Res Hum Res Ethics 2013;8:129–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Chenhall RD. Benelong's Haven: An anthropological study of an Australian Aboriginal rehabilitation centre [Doctoral dissertation ]: University of London; 2002.

- 80.Feely M, Seay KD, Lanier P, Auslander W, Kohl PL. Measuring Fidelity in Research Studies: A field guide to developing a comprehensive fidelity measurement system. Child Adolesc Social Work J 2017;35:139–52. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hart LM, Jorm AF, Kanowski LG, Kelly CM, Langlands RL. Mental health first aid for Indigenous Australians: using Delphi consensus studies to develop guidelines for culturally appropriate responses to mental health problems. BMC Psychiatry 2009;9:47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Chalmers KJ, Bond KS, Jorm AF, Kelly CM, Kitchener BA, Williams‐Tchen A. Providing culturally appropriate mental health first aid to an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander adolescent: development of expert consensus guidelines. Int J Ment Health Syst 2014;8:6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1. SMART Recovery program adherence checklist.

Appendix S2. SMART Recovery program adherence checklist inter‐rater reliability calculations.