Abstract

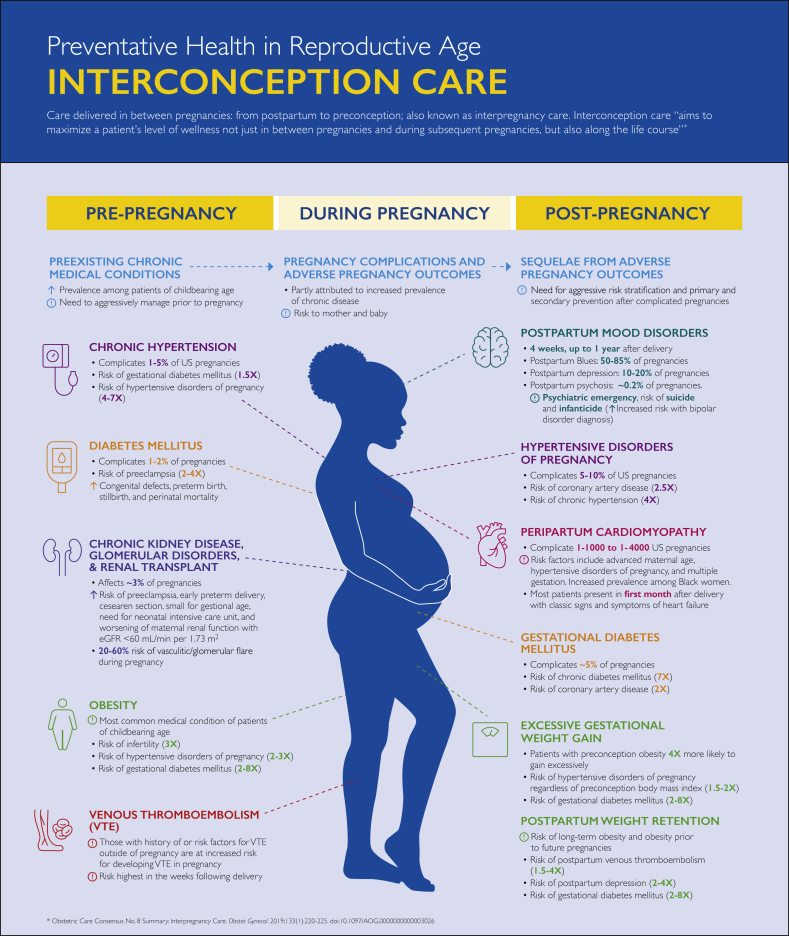

Severe maternal morbidity and mortality continue to increase in the United States, largely owing to chronic and newly diagnosed medical comorbidities. Interconception care, or care and management of medical conditions between pregnancies, can improve chronic disease control before, during, and after pregnancy. It is a crucial and time-sensitive intervention that can decrease maternal morbidity and mortality and improve overall health. Despite these potential benefits, interconception care has not been well implemented by the primary care community. Furthermore, there is a lack of guidelines for optimizing preconception chronic disease, risk stratifying postpartum chronic diseases, and recommending general collaborative management principles for reproductive-age patients in the period between pregnancies. As a result, many primary care providers, especially those without obstetric training, are unclear about their specific role in interconception care and may be unsure of effective methods for collaborating with obstetric care providers. In particular, internal medicine physicians, the largest group of primary care physicians, may lack sufficient clinical exposure to medical conditions in the obstetric population during their residency training and may feel uncomfortable in caring for these patients in their subsequent practice.

The objective of this article is to review concepts around interconception care, focusing specifically on preconception care for patients with chronic medical conditions (eg, chronic hypertension, chronic diabetes mellitus, chronic kidney disease, venous thromboembolism, and obesity) and postpartum care for those with medically complicated pregnancies (eg, hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, gestational diabetes mellitus, excessive gestational weight gain, peripartum cardiomyopathy, and peripartum mood disorders). We also provide a pragmatic checklist for preconception and postpartum management.

Abbreviations and Acronyms: ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme; ACOG, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; BMI, body mass index; CKD, chronic kidney disease; CVD, cardiovascular disease; DM, diabetes mellitus; GDM, gestational diabetes mellitus; HbA1c, hemoglobin A1c; HDP, hypertensive disorder of pregnancy; MFM, maternal-fetal medicine; NTD, neural tube defect; OB/GYN, obstetrician/gynecologist; PCP, primary care provider; PPCM, peripartum cardiomyopathy; SMFM, Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine; VTE, venous thromboembolism

During the last 40 years, maternal morbidity and mortality have dramatically increased.1,2 Although of concern in many countries, the United States in particular has the highest maternal mortality ratio† of any developed nation, with wide disparities by race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status.2, 3, 4 This rise is due to several factors; however, chronic and newly diagnosed peripartum medical comorbidities are a large contributor.5,6 In the United States, there is an increasing prevalence of preexisting medical conditions among reproductive-age patients,‡ which has led to greater emphasis on the importance of optimally managing chronic conditions in the preconception period.1,7,8 Furthermore, there is increased awareness that certain complications during pregnancy are also associated with future chronic disease development, highlighting the need for better postpartum follow-up of these patients to improve future pregnancy outcomes and long-term health.9, 10, 11

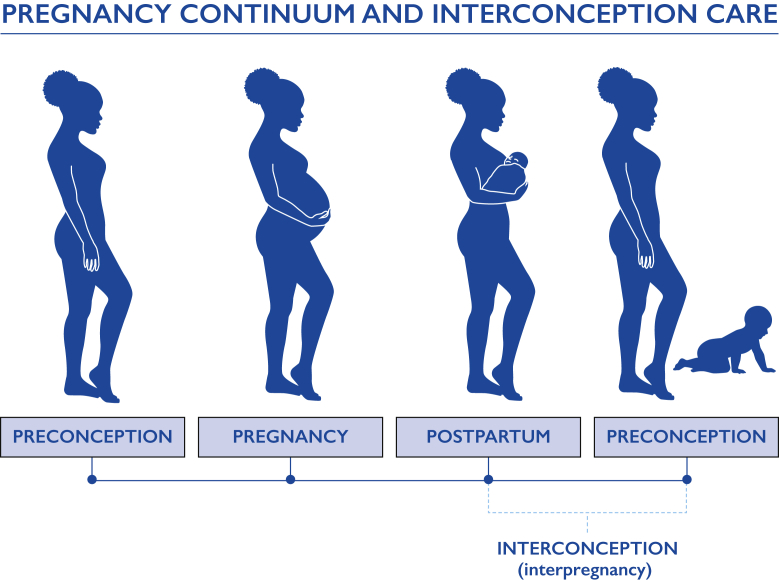

Interconception care (or interpregnancy care) is defined as “care provided to mothers between pregnancies to improve health outcomes for patients [and their infants].”12 Interconception care encompasses the continuum of postpartum and preconception care (Figure 1) and emphasizes the evaluation of a patient’s health through a life course perspective that acknowledges the influence of pregnancy on health trajectory.13,14 Attention to chronic medical conditions in this period can improve chronic disease control before, during, and after pregnancy and is crucial in decreasing maternal morbidity and mortality and improving long-term health, especially because 36% of patients aged 18 to 49 years have at least 1 medical condition. Most (74%) of these patients have a usual source of care to go to when they are sick and describe their usual source of care as primary care providers (PCPs), who typically have family medicine, internal medicine, or advanced practice provider backgrounds.15 Importantly, there is some evidence to suggest that patients of reproductive age are more likely to identify obstetrician/gynecologists (OB/GYNs) as their usual source of care and to seek preventive care from these providers.16 However, there is also evidence that compared with OB/GYNs, PCPs are more likely to screen and to counsel on chronic disease and lifestyle interventions during well-patient visits.16 Accordingly, closer continuity with PCPs who manage chronic disease during the preconception and postpartum periods provides a mechanism to achieve the optimal interconception care and has been recommended by maternal mortality review committees as well as by national organizations focused on reproductive health.9,10,17, 18, 19, 20 However, many PCPs are unclear about their specific role in interconception care. In particular, most general internal medicine physicians, in contrast to family medicine physicians, lack sufficient clinical exposure to medical conditions in the obstetric population during their residency training. They may not feel well equipped to provide preconception and interconception care, perhaps believing these tasks more suitable for obstetric care providers (eg, nurse midwives and OB/GYNs).21,22 However, internal medicine physicians are the largest medical specialty and provide nearly 35% of primary care in the United States.23 Thus, it is a missed opportunity to not use the internal medicine workforce along with other PCPs who manage chronic disease (eg, family medicine providers and other advanced practice providers) to improve maternal health outcomes through chronic disease control and prevention.

Figure 1.

Pregnancy continuum and interconception care.

Although interconception care has not been well addressed by the primary care community, the American Heart Association and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) have issued some guidance on this topic.10,20 However, guidelines for PCPs regarding chronic disease risk stratification and management of reproductive-age patients in the period between pregnancies are lacking. For example, the 2018 American College of Physicians position paper on women's health policy acknowledged the contribution of rising chronic medical conditions on maternal mortality, but there were no specific clinical recommendations for the care of patients of reproductive age before or between pregnancies.24

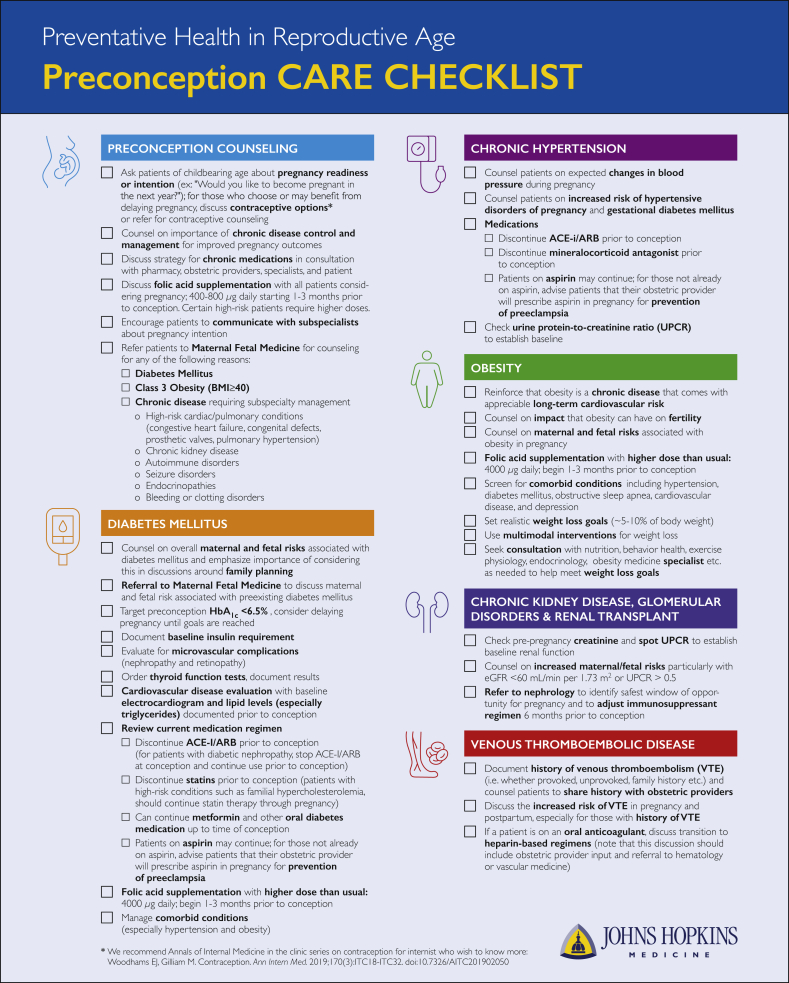

In this report, we address this content gap by reviewing high-yield interconception care concepts for general internal medicine physicians and other PCPs who manage chronic disease in adults. We begin with an overview of key history taking and collaborative management principles for reproductive-age patients. We then focus on preconception and interconception management for patients with medical comorbidities, including chronic hypertension, hypertensive disorder of pregnancy (HDP), preexisting diabetes mellitus (DM), gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM), preconception obesity, excessive gestational weight gain, chronic kidney disease (CKD), venous thromboembolism (VTE), peripartum cardiomyopathy (PPCM), and peripartum mood disorders. We also include a Supplement (available online at http://mcpiqojournal.org) on emerging trends related to opioid use disorders and maternal health and the role of the PCP. We focus on these medical topics because they represent the most significant contributors to maternal morbidity and mortality that can be recognized by PCPs. We also summarize these topics in several high-yield figures and tables. Finally, we include a pragmatic reference for interconception care, with checklists (Figure 2) for preconception and postpartum management.

Figure 2.

Preconception and postpartum checklists for the management of the reproductive age patient with medical comorbidities. ACE-I, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; HbA1c, hemoglobin A1c; NSAIDs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; UPCR, urine protein to creatinine ratio; VTE, venous thromboembolism.

In developing this review, we reference primary research articles, expert narrative reviews, systematic reviews, and meta-analyses and the guidelines of the ACOG, Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine (SMFM), American Diabetes Association, and American Heart Association. We also add our opinions because we are clinicians in the fields of general internal medicine, cardiology, nephrology, obstetric medicine, obesity medicine, and maternal-fetal medicine (MFM) and focus our research on preconception planning, pregnancy-related complications, and medical education in the care of the pregnant patient.

Part I: Interconception Counseling and Collaborative Management

Discuss Family Planning and Birth Spacing

Patients who are not breastfeeding can become pregnant within 6 weeks of delivery. The ACOG and SMFM recommend avoiding extreme interpregnancy intervals (eg, less than 6 months or more than 5 to 10 years) as this is associated with increased risks of adverse maternal and fetal outcomes.10,25,26 Therefore, PCPs should inquire about family planning, assess pregnancy readiness and intention, and elicit questions about contraceptive care at every visit. The PCP can consider the following:

-

•

Evaluate pregnancy readiness and intention. The PCP can use this patient-centered screening question: Would you like to become pregnant in the next year?27

-

•

Discuss birth spacing. After assessing time since last pregnancy, PCPs should counsel patients on recommended interpregnancy intervals of more than 6 months and ideally more than 18 months.10

-

•

Discuss contraceptive options. Primary care providers should consider increasing their general understanding of birth control options, success rates, and risks of different methods. They can review references, such as the Annals of Internal Medicine “In the Clinic Series” discussing contraception.28 In addition, PCPs should be aware of the risks of combined hormonal contraceptives, including VTE, arterial clot, and ischemic stroke.28 They should be aware of the predisposing risk factors and symptoms of these complications, including uncontrolled hypertension, smoking, migraine with aura, and previous VTE. In these situations, combined hormonal contraceptives are relatively contraindicated. In addition, patients older than 40 years and those who are obese are at greater risk of adverse outcomes.28

• For PCPs who prescribe contraceptives, use the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s medical eligibility criteria to guide counseling and prescribing for patients with medical problems (https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/contraception/contraception-app.html; also available as a smartphone app for Android and Apple devices).29, 30, 31

• For complex patients who require in-depth counseling or contraceptive procedures, PCPs should consider referral to an OB/GYN or family planning specialist.29

Obtain an Obstetric History

When evaluating patients in the interconception period, PCPs should obtain an obstetric history and particularly focus on pregnancy complications that are important predictors for future cardiovascular disease (CVD), including GDM, HDP, and preterm birth.32 In some cases, health record review is important because GDM and gestational age at delivery are recalled with high sensitivity but HDP is less well remembered.33,34 Although the following list is not exhaustive,§ PCPs should at least focus on these questions:

-

•

Did you have diabetes during your pregnancy?

-

•

Did you have high blood pressure, preeclampsia or eclampsia, or toxemia during your pregnancy?

-

•

Was your baby born early or preterm (<37 weeks)?

Provide Preconception Advice and Counseling

Primary care providers play a pivotal role during preconception counseling for patients with chronic medical conditions. They should highlight the impact of chronic diseases on conception and emphasize the importance of chronic disease management for optimal pregnancy outcomes. In addition, PCPs should closely coordinate management with medical subspecialists, OB/GYNs, and MFM physicians to optimize health status before pregnancy.

Medication Management

Partly because of the lack of data on medication safety in pregnancy,35 it is common for patients to abruptly discontinue medications because of the fear of adverse fetal effects.36 However, a healthy mother is important for a healthy baby, and chronic disease that is well controlled with medications generally portends improved outcomes for both mother and child. The PCP should emphasize this maternal health–fetal link and engage in shared decision-making regarding treatment modalities during pregnancy. In addition, PCPs should develop strong relationships with subspecialists, pharmacists, obstetricians, and MFM providers to consider medication risks and benefits and to assess alternative treatments in a multidisciplinary manner.

Communication With Subspecialists

Similar to other times, PCPs should coordinate patient care during the preconception period with subspecialists. In addition, PCPs should encourage patients to communicate with subspecialists about pregnancy intentions. Communication can be through designated areas in the electronic health record or email among members of multidisciplinary teams (especially at times of care transitions).37

Care Coordination With MFM Specialists

Maternal-fetal medicine physicians are OB/GYNs who specialize in the diagnosis and management of high-risk pregnancies. Patients requiring subspecialty care for chronic conditions should be referred to an MFM physician for pregnancy planning and to assess maternal and fetal risk.

Part II: Management of Medical Conditions Related to Maternal Morbidity and Mortality

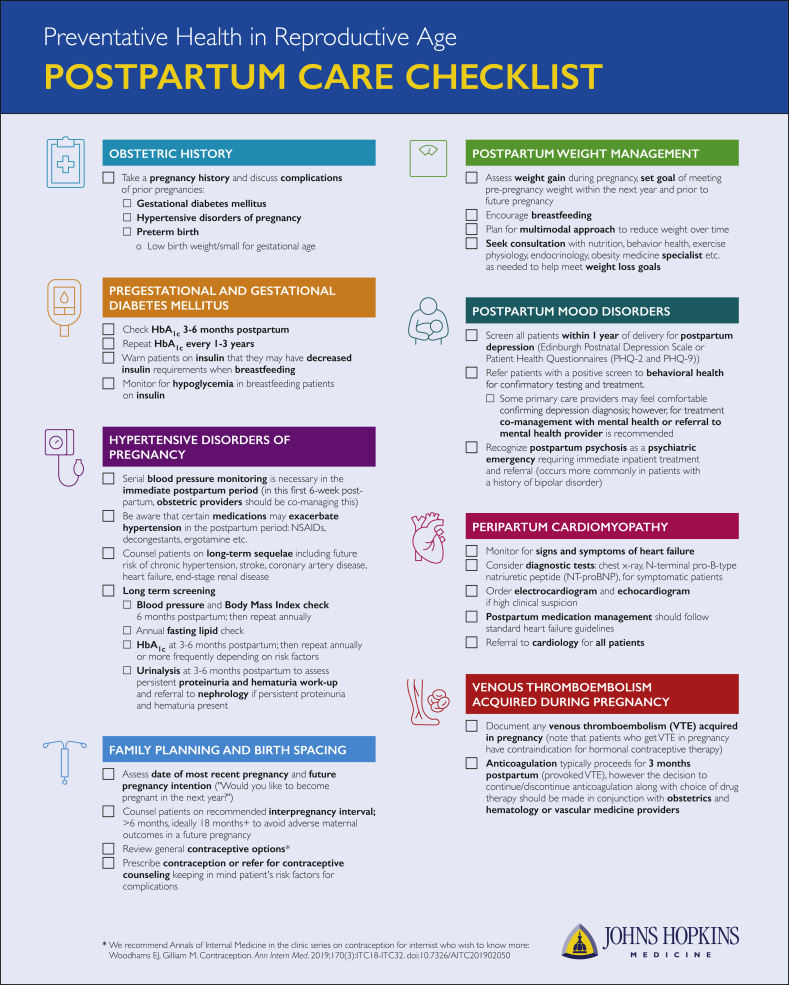

In the following sections, we describe 10 important interconception care concepts that should become familiar to PCPs (Figure 3).

-

1.

Address preexisting (chronic) hypertension during the preconception and early pregnancy periods.

Figure 3.

Prepregnancy and postpregnancy medical conditions related to maternal morbidity and mortality. ACE-I, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; HbA1c, hemoglobin A1c; NSAIDs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; UPCR, urine protein to creatinine ratio; VTE, venous thromboembolism.

Preexisting hypertension (ie, chronic hypertension) is present in approximately 8% of patients of reproductive age38 and complicates 1% to 5% of pregnancies.39, 40, 41 Primary care providers can play a crucial role in preconception counseling and antihypertensive medical management.

-

•

Address maternal-fetal risks. Patients can be counseled that preexisting hypertension confers a 1.5 increased risk of GDM and a 4-fold to 7-fold higher risk of preeclampsia∗∗ compared with patients without preexisting hypertension.39,42, 43, 44 In addition, there is increased risk for abnormal fetal growth and placental dysfunction.41,44

-

•

Management of blood pressure changes. Blood pressure goals and responses to therapy differ during pregnancy and are typically less restrictive than blood pressure goals outside of pregnancy (eg, the ACOG recommends that patients with uncomplicated hypertension maintain blood pressures between 120/80 mm Hg and 160/105 mm Hg42,45). Patients may need fewer or no antihypertensive medications early in pregnancy because of the physiologic changes of pregnancy—late first-trimester systemic vasodilation results in a fall of 5 to 10 mm Hg in blood pressure.42 Many need close follow-up and adjustment of medications, which can be facilitated with home monitoring devices.46

-

•Preconception antihypertensive management42,46,47

-

○In patients who intend to become pregnant, PCPs should consider switching to labetalol or nifedipine, 2 antihypertensive medications with known safety profiles. In contrast, switching to methyldopa is less desirable, even though it has been a longtime first-line agent for blood pressure management in pregnant patients, because of its dosing frequency, adverse effect profile, and limited use in patients with underlying renal or hepatic disorders. In addition, PCPs should stop angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), which are contraindicated during pregnancy. Patients with a well-established indication, such as proteinuria or heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, should be observed closely in the antepartum period by their respective subspecialists so that an individualized decision can be made about the timing of medication cessation, which can occur at conception or before conception. Those with a sole diagnosis of hypertension should be transitioned off these medications before conception.

-

○Before conception, PCPs should transition away from mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists as these medications are contraindicated during pregnancy.

-

○Patients treated with diuretics should be closely observed. The decision to continue or to discontinue diuretics depends on the indication. Hypertension could be easily managed with alternative antihypertensives,47 but other indications related to cardiac, hepatic, or renal disease should involve input from the appropriate subspecialist before medication cessation. If adding diuretics during pregnancy is considered, it should be initiated only in close collaboration with MFM physicians and medical subspecialists.

-

○Low-dose aspirin therapy during pregnancy may reduce the risk of preeclampsia. Because patients with chronic hypertension are at increased risk of preeclampsia, obstetric providers typically initiate low-dose aspirin (81 mg daily is the dose currently recommended by the ACOG and SMFM) between 12 and 28 weeks’ gestation (optimally before 16 weeks).48 Primary care providers should be aware that patients with chronic hypertension or receiving aspirin therapy for other reasons may remain on this medication before conception.

-

○

-

2.

Manage patients with a history of HDP.

Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy complicate approximately 5% to 10% of pregnancies and occur along a spectrum of severity based on the timing of elevated blood pressure and whether there is associated end-organ damage (Table 1). Patients discharged with manifestations of hypertension in the hospital need outpatient follow-up within 1 week of discharge. In addition, blood pressure should be checked 3 to 10 days after delivery to allow close titration of antihypertensive medications.11

-

•

Postpartum management of antihypertensive medications

Table 1.

General Classification of Patients With Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy

| Hypertensive condition | Gestational age at onset | Details for diagnosis |

|---|---|---|

| Chronic hypertension | Before pregnancy or <20 weeks | Blood pressure >140/90 mm Hga |

| Gestational hypertension | >20 weeks | Blood pressure >140/90 mm Hg and No evidence of proteinuria No end-organ damage |

| Preeclampsia or eclampsia | >20 weeks | Blood pressure >140/90 mm Hg and Evidence of proteinuria or Signs and symptoms of hypertension-related end-organ damage |

| Chronic hypertension with superimposed preeclampsia | >20 weeks | Meets diagnostic criteria for chronic hypertension and develops criteria for preeclampsia/eclampsia syndrome after 20 weeks of gestation |

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ definition of hypertensive disorder of pregnancy uses blood pressure above 140/90 mm Hg, which is based on the 2003 Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC7) guideline criteria for hypertension. In 2017, the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association updated guidelines, recommending a lower threshold for the diagnosis of hypertension (blood pressure <130/80 mm Hg). Studies evaluating the implications of using more stringent American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association criteria for the diagnosis of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy are ongoing,49, 50, 51, 52 but currently the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ definitions are unchanged.

If possible, PCPs should discontinue postpartum medications that can exacerbate hypertension (eg, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, decongestants, ergotamine).17,18 Otherwise, postpartum hypertension management resembles preconception hypertension management. Blood pressure targets should be consistent with American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association blood pressure guidelines (ie, nonpregnant patients who are in the stage 1 hypertension category [systolic blood pressure of 130 to 139 mm Hg or diastolic blood pressure of 80 to 89 mm Hg] should begin treatment if they have risk factors for CVD).53

When selecting medications, PCPs should consider comorbidities and the mother’s choice to breastfeed. Many medications are generally safe with lactation, including ACE inhibitors (particularly captopril and enalapril),†† calcium channel blockers, methyldopa, and labetalol.47 Nifedipine is especially effective and probably should be considered first in the absence of compelling indications for another medication class.54 Labetalol and other nonselective beta blockers are generally considered safe; however, cardioselective beta blockers (eg, atenolol and metoprolol) are less useful because they may concentrate in breast milk and lead to newborn lethargy and bradycardia. Because of these adverse effects, the American Academy of Pediatrics had cautioned against these medications,42,55 but their most recent update notes difficulty in keeping up with the safety data for lactating mothers. Therefore, PCPs should consult the up-to-date National Institute of Health’s LactMed database56 before initiating antihypertensive medications in breastfeeding patients.57

-

•

Counseling on long-term HDP sequelae

Primary care providers should inform patients who have had HDP that they are at increased risk for development of chronic hypertension (defined as the persistence of elevated blood pressure 12 weeks post partum).45 In addition, they are at increased risk for CVD, including stroke, coronary artery disease, and heart failure.58 Because of the increased risk for long-term adverse outcomes, there is increased interest in the use of aspirin for the prevention of CVD; however, there is not enough evidence to recommend its use. In addition, other adverse long-term HDP outcomes include chronic and end-stage kidney disease59 and DM.60

-

•

Screening for future disease

In patients who have had HDP, PCPs should aggressively screen and treat risk factors for CVD, including hypertension, obesity, hyperlipidemia, DM, and renal dysfunction.61,62 PCPs should

-

○

Screen for chronic hypertension and elevated body mass index (BMI) every 6 months in the first year after delivery and then annually afterward.

-

○

Check annual fasting lipid profile 3 to 6 months post partum or after breastfeeding cessation. Checking earlier is of less value because pregnant and lactating patients have elevated lipid levels.

-

○

Check fasting glucose concentration or hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) level 3 to 6 months after delivery and then at least annually.

-

○

Perform urinalysis to detect the presence or persistence of proteinuria 3 months post partum; if proteinuria persists past 3 months, refer to a nephrologist.

-

3.

Manage patients with preexisting (chronic) DM.

Preexisting (chronic) DM complicates 1% to 2% of pregnancies and is associated with significant adverse maternal and fetal outcomes, including preeclampsia, cesarean delivery, and acute myocardial infarction.63,64 There are also higher fetal risks for congenital defects, preterm birth, stillbirth, and perinatal mortality.64 To minimize these complications, PCPs should aim for a preconception HbA1c level below 6.0% to 6.5%, unless there are episodes of hypoglycemia, in which case a target level below 7% is preferred.63,65 In addition, these patients need close coordination of care with MFM physicians. Finally, patients are at higher risk of concomitant CVD and need aggressive screening and treatment of risk factors and comorbid conditions.

-

•

Discuss maternal and fetal risks and referral to MFM physician. Inform patients of the risks of DM on maternal and fetal health. In addition, patients with poorly controlled DM should be referred to an MFM physician for preconception counseling.64

-

•

Target preconception HbA1clevel to below 6.5%. Discuss pregnancy timing with patients whose HbA1c level is not at goal. Also, optimize medical therapy and encourage lifestyle changes.63, 64, 65

-

•

Refer for retinal examination. Diabetic retinopathy often worsens during pregnancy or with rapid improvements in glycemic control. All patients with type 1 or type 2 DM should undergo retinal examination at least once before conception.63,64

-

•

Quantify proteinuria. Patients with diabetic kidney disease require MFM management during pregnancy because of increased risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes.63,64 Therefore, it is important to obtain a baseline urine protein to creatinine ratio or a urine albumin to creatinine ratio.

-

•

Check thyroid function. Patients with type 1 DM are at higher risk of additional preexisting autoimmune disorders, including thyroid disease. Therefore, it is recommended to obtain baseline thyroid function levels.63,64

-

•

Review folic acid supplementation requirements. The ACOG and the US Preventive Services Task Force recommend that all pregnant patients take 400 to 800 μg of folic acid for at least 1 month (ideally 3 months) preceding pregnancy to prevent neural tube defects (NTDs). For higher risk patients, including those with prior NTD-affected pregnancy, those with a personal or partner history of NTD, those with a first-degree relative with NTD, those taking antiseizure medications, those with poorly controlled or type 1 DM, and those who are obese, higher doses (4000 μg daily) of folic acid supplements need to be started 3 months before conception.66,67

-

•Manage medications.

- ○

-

○Some medications concomitantly used in patients with DM, such as statins, ACE inhibitors, and ARBs, are teratogenic. Therefore, PCPs should carefully review medication lists and discontinue contraindicated therapies.64 Of note, patients with high-risk conditions, such as patients with severe familial hypercholesterolemia and patients taking statins before pregnancy, should continue statin therapy through pregnancy. Similarly, patients with diabetic nephropathy or other high-risk condition requiring ACE inhibitors or ARBs should discontinue use at conception instead of before conception.

-

○Similar to patients with preexisting or chronic hypertension, patients with preexisting DM are at increased risk of preeclampsia. Therefore, low-dose aspirin (81 mg daily) initiated between 12 and 28 weeks’ gestation is recommended.48 Because DM is considered a cardiovascular risk factor equivalent, patients with DM may already be taking low-dose aspirin for primary prevention, in which case PCPs should confirm aspirin use and recommend continuation of aspirin throughout pregnancy.

-

•

Closely monitor lactating patients. Breastfeeding for patients with DM is associated with many benefits, including reduced postpartum weight and a lower risk of obesity and type 2 DM in the offspring.69, 70, 71 However, breastfeeding may increase the risk for hypoglycemic events, which may require reductions in insulin dose or the provision of small snacks during lactation.63,64

-

4.

Manage patients with a history of GDM.

Approximately 5% of all pregnant patients develop GDM, which occurs when DM develops during the second or third trimester of pregnancy.68 Gestational diabetes mellitus also increases the risk of adverse maternal and fetal outcomes, including preeclampsia, cesarean delivery, neonatal hypoglycemia, neonatal macrosomia, shoulder dystocia, fetal hyperbilirubinemia, and birth trauma.63,72 In addition, patients with a history of GDM have a 7-fold higher risk for subsequent development of type 2 DM and a 2-fold higher risk for development of chronic hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and CVD.73, 74, 75, 76 For these reasons, all patients who have had GDM need follow-up with a PCP.10,77 In particular, the PCP should screen for the development of chronic DM in the postpartum period and manage concomitant cardiometabolic risk factors.

-

•

Check for persistent postpartum glucose intolerance. Patients with a history of GDM should undergo a screening 2-hour 75-g oral glucose tolerance test at the 6-week obstetric postpartum visit. However, there are high rates of nonadherence to this recommendation, so checking of HbA1c level 3 to 6 months post partum is reasonable.68

-

•

Check HbA1clevel regularly. Patients with a history of GDM should undergo HbA1c testing at least once every 3 years, although annual checks are ideal. More frequent testing is recommended for those with additional risk factors, including elevated BMI, family history of DM, and multiple pregnancies complicated by GDM.68

-

5.

Manage and discuss risks associated with preconception obesity.

Obesity is the most common medical problem for reproductive-age patients, affecting 32% of those aged 20 to 39 years.78 Preconception obesity affects pregnancy risk and is associated with worse adverse maternal and fetal outcomes compared with large amounts of gestational weight gain.79 Despite these deleterious effects, only 5% of patients with overweight or obesity received weight counseling before pregnancy.80 Therefore, it is imperative for PCPs to increase their focus on interventions to improve preconception BMI,81 especially for those patients who do not recognize obesity as a medical problem or understate its significance in pregnancy.82,83 Primary care providers can also screen for comorbid conditions, which are more often found in the obese population.

-

•

Define obesity. Educate patients on normal BMI numbers as well as on obesity-associated metabolic and cardiovascular sequelae (eg, hypertension, DM, dyslipidemia, obstructive sleep apnea; also consider prior pregnancies complicated by HDP and GDM84).

-

•

Counsel about the effects of obesity on fertility. Obesity can negatively affect fertility through dysregulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis.85 Patients with obesity and documented infertility can benefit from referral to obstetric subspecialists or endocrinologists for evaluation of polycystic ovarian syndrome or other hormonal dysregulations.

-

•

Review folic acid supplementation requirements. As discussed in the DM section, patients with obesity are at higher risk for fetal NTD and should take higher doses (4000 μg daily) of folic acid supplements, preferably starting 3 months before conception.66,67

-

•Address increase in maternal and fetal risks.86 Obesity in pregnancy increases maternal and fetal morbidity, increasing the risk of

-

○HDP and GDM

-

○Spontaneous abortion and recurrent miscarriage

-

○Delivery complications: failed labor, spontaneous preterm delivery, cesarean section, endometritis, and wound rupture or dehiscence

-

○Maternal health complications: cardiac dysfunction, obstructive sleep apnea, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, and VTE

-

○Fetal health complications: congenital anomalies, fetal macrosomia

-

○Postpartum complications: risk of early breastfeeding termination, postpartum anemia, and postpartum depression

-

○

-

•

Encourage realistic weight loss goals. Weight loss is the best pre-pregnancy intervention for patients with overweight or obesity. A target weight loss of 5% to 10% improves fertility and pregnancy outcomes.82,86

-

•Know the most effective weight loss strategies and implications for reproductive planning. Changes in diet alone and diet plus exercise are more effective than exercise alone,34 with even better results from intensive multimodal interventions that include lifestyle changes in diet, exercise, and behavior.30

-

○Patients with a BMI of 30 kg/m2 or higher (or BMI ≥27 kg/m2 with obesity-associated comorbidities) who do not achieve significant weight loss with lifestyle interventions should be considered for antiobesity medication therapy. Antiobesity medications demonstrate an additive benefit to lifestyle interventions, leading to more than 5% additional weight loss, which leads to improvements in cardiometabolic and reproductive health.87 For additional insights in prescribing these medications, PCPs can consult a weight loss specialist or engage a multidisciplinary team. Importantly, antiobesity medications have not been extensively studied in pregnancy and may be teratogenic. Therefore, antiobesity medications should be discontinued before conception is attempted. At other times, PCPs should counsel patients on the risks and benefits of antiobesity medications and work together to come up with a contraceptive plan while the patient is taking these medications.

-

○Patients with a BMI of 40 kg/m2 or higher (or BMI >35 kg/m2 with obesity-associated comorbidities) who do not achieve significant weight loss with lifestyle interventions or antiobesity medications should be considered for surgical intervention. Bariatric surgery is the highest efficacy option for long-term weight loss. Among patients with obesity, preconception bariatric surgery improves fertility and reduces obesity-related pregnancy complications as well as the risk of obesity in offspring.84,88,89 Eligible patients can be referred to bariatric surgery centers and multidisciplinary weight management teams for evaluation. These teams should closely collaborate with knowledgeable OB/GYN and MFM providers, who can recommend timing of conception (the general recommendation is to avoid pregnancy in the first year after bariatric surgery or during the period of rapid weight loss) and address any surgical complications or nutritional deficiencies.90,91

-

○

-

•

Use a multidisciplinary approach. Involve nutritionists, exercise physiologists, behavioral health providers, endocrinologists, or obesity medicine specialists for the optimal care of patients in the interconception period.82

-

6.

Manage gestational weight gain and postpartum weight retention.

Patients with higher preconception BMI are 4 times more likely than patients with normal preconception BMI to gain excessive weight during pregnancy.92 In addition, weight gain during pregnancy catalyzes the development, persistence, and exacerbation of obesity.93,94 In particular, excessive gestational weight gain increases the likelihood of postpartum weight retention and subsequent preconception BMI.93,94 For these reasons, PCPs should advise patients on optimal weight gain during pregnancy as outlined in Table 2, which depends on preconception BMI. Of note, weight reduction during pregnancy remains controversial and is not recommended.95

-

•

Assess risk for excessive gestational weight gain and postpartum weight retention. Be familiar with the Institute of Medicine guidelines for pregnancy weight gain (Table 2) and help with postpartum weight reduction plans.

-

•

Counsel patients on healthy gestational and postpartum weight. Whereas some persistent postpartum weight retention can be a consequence of a normal pregnancy, weight reduction should be encouraged if a patient is overweight or obese. The first 6 months post partum may be a time of readjustment and transition; conversations about weight management and physical activity may be better received after this time. Recommendations for weight loss generally follow recommendations in the preconception period. However, antiobesity medications should not be used while breastfeeding. In addition, the ideal timing for bariatric surgery after pregnancy is unclear, but it is reasonable to wait 1 year to begin evaluation. If future pregnancies are planned, it is reasonable to set a goal to return to pre-pregnancy weight ( or lower) before the next pregnancy.

-

•

Encourage breastfeeding. In addition to other benefits, multiple studies have established that breastfeeding is associated with reduced postpartum weight retention.69

-

7.

Manage and discuss risks associated with preconception CKD.

Table 2.

Institute of Medicine Weight Gain Recommendations for Pregnancy

| Preconception weight category (body mass index) | Recommended total weight gain during pregnancy |

|---|---|

| Underweight (<18.5 kg/m2) | 28-40 pounds |

| Normal weight (18.5-24.9 kg/m2) | 25-35 pounds |

| Overweight (25-29.9 kg/m2) | 15-25 pounds |

| Obese (>30 kg/m2) | 11-20 pounds |

Adapted from Weight Gain During Pregnancy: Reexamining the Guidelines.95

Although kidney disease is uncommon (~3%) in the average patient of reproductive age, even early stages of CKD carry an increased risk of adverse maternal and fetal outcomes, including higher rates of preterm delivery, cesarean section, and need for neonatal intensive care.96,97 Importantly, worsening of maternal and fetal outcomes is noted in more advanced stages of CKD (eg, stages 3 to 5 CKD), including new-onset hypertension and proteinuria, worsening CKD, and dialysis initiation.97 Most notably, 25% of patients with advanced CKD experience a postpartum decline in their estimated glomerular filtration rate, which is significant enough to increase the risk of dialysis dependence within 6 months of delivery.97,98 Given these pregnancy-associated risks, pregnant patients with even mild stages of CKD should be referred to a nephrologist for care during their pregnancies.

It is also important for PCPs to identify patients with underlying glomerular disorders who intend to become pregnant as these patients are often taking immunosuppressive medications with teratogenic potential. These regimens require a subspecialist for transition to safer alternatives at least 6 months before conception to ensure disease quiescence.

-

•Establish preconception kidney function in patients with underlying kidney disease. PCPs should measure pre-pregnancy creatinine concentration and urine protein to creatinine ratio to help risk stratify patients at increased risk for adverse maternal and fetal outcomes.

-

○Although multiple societies recommend against routine screening for kidney disease in asymptomatic individuals, it is reasonable to check kidney function in patients who are desiring pregnancy, especially among those with risk factors (eg, family history of kidney failure and those with chronic hypertension or DM).99, 100, 101

-

○

-

•

Refer patients with renal transplant and patients with rheumatologic, vasculitic, or glomerular disease to the appropriate subspecialist if they are trying to conceive. Pregnancy is known to incite disease flares and confers a higher risk of HDP in patients with these disorders.102, 103, 104, 105, 106 In addition, patients often require a change in immunosuppressives to allow a safe pregnancy.

-

•

Evaluate for postpartum resolution of HDP-related abnormalities. Most patients should have complete normalization of their blood pressure, proteinuria, or hematuria by 8 weeks post partum. Persistence of these findings, particularly proteinuria or hematuria, warrants further investigation by a nephrologist.

-

•

Encourage breastfeeding. Mothers can safely continue many medications for renal disease while breastfeeding, including prednisone, azathioprine, calcineurin inhibitors, some ACE inhibitors, intravenous immunoglobulin, and dialysis therapy.56 Before discontinuation of a medication or breastfeeding, a thorough discussion between PCP, subspecialist, and patient is needed to ensure that breastfeeding is not inadvertently and inappropriately discontinued.

-

•

Discuss family planning. With the help of a nephrologist, a safe window for pregnancy can be identified while taking into account the underlying glomerular disorder or CKD severity.

-

8.

Postpartum mood disorders

Postpartum depression affects 10% to 20% of patients.107 Postpartum depression is characterized by symptoms of major depression within 4 weeks of delivery but can occur up to 1 year after delivery.107 Postpartum depression occurs more commonly in those with a history of preconception depression or postpartum depression after a prior pregnancy. Other postpartum mood disorders that may occur include postpartum blues and postpartum psychosis. Postpartum blues affect 50% to 85% of patients and may be related to hormonal swings in the postpartum period. Patients with postpartum blues describe fatigue, emotional lability, and exhaustion; these symptoms usually resolve within 2 weeks and do not cause significant morbidity.107 In contrast, postpartum psychosis, the rarest and gravest of the postpartum mood disorders, affects approximately 0.2% of patients and is considered a psychiatric emergency because of symptoms of delusions, hallucinations, and tendencies toward infanticide.107 Because of their familiarity with depression, PCPs are uniquely positioned to screen and to identify patients at risk of postpartum depression and other postpartum mood disorders.

-

•

Screen for postpartum depression and other postpartum mood disorders. Primary care providers should consider using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale, which is specifically designed for primary care settings and can be completed in 5 minutes. Alternatively, PCPs may use the more familiar 2-item and 9-item Patient Health Questionnaires (PHQ-2 and PHQ-9, respectively). The PHQ-2 has high sensitivity and the PHQ-9 has high specificity for identifying postpartum depression; thus, a 2-stage approach using these questionnaires is accurate in detecting postpartum depression.108

-

•Recognize spectrum of postpartum mood disorders and initiate management or referral. The PCP should recognize differences between postpartum blues, postpartum depression, and postpartum psychosis and offer different levels of services accordingly:

-

a.Postpartum blues. In general, providers should provide reassurance and support. In addition, providers should have heightened vigilance for postpartum depression because approximately 20% of these patients develop postpartum depression.107

-

b.Postpartum depression. Psychotherapy is the initial treatment of choice for mild to moderate postpartum depression; however, it is also reasonable to initiate antidepressant pharmacotherapy (for both breastfeeding and non-breastfeeding patients) when psychotherapy is not available. For treatment-naive patients, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors are first line (paroxetine, sertraline, or citalopram is recommended).109 For patients who do not respond initially to a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, switching drug classes to a serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor, tricyclic antidepressant, or α2-adrenergic receptor antagonist may be warranted. Postpartum depression cases that are refractory to antidepressant medications may require electroconvulsive therapy or brexanalone infusion (a progesterone metabolite).109 Primary care providers may not feel comfortable with treating postpartum depression, in which case referral or consultation for co-management with a mental health provider is an appropriate strategy.

-

c.Postpartum psychosis. This psychiatric emergency requires immediate inpatient admission and consultation with a mental health provider.

-

a.

-

•

Learn available mental health resources. Primary care providers should be familiar with mental health resources within their clinic. They should also know referral sources, including reproductive behavioral and mental health providers, emergency suicide prevention phone numbers and protocols, case management support, and other sources.

-

9.

Venous thromboembolic disorders

Because pregnancy is a hypercoagulable state, VTE is a leading cause of maternal morbidity and mortality, particularly in the postpartum period.110 In general, patients with a history of or risk factors for VTE are at even greater risk for development of VTE in pregnancy. In addition, patients with VTE receiving anticoagulation who are planning pregnancy should be transitioned to low-molecular-weight heparin in anticipation of pregnancy because warfarin and other direct anticoagulants are not preferred owing to teratogenicity or lack of safety data.110 For those patients who develop acute VTE during pregnancy, anticoagulation is required for the remainder of pregnancy and at least 3 months post partum.110

-

•

Document VTE risk factors and history of conditions requiring anticoagulation. Primary care providers should survey for family history of VTE, known hypercoagulable states, and history of conditions requiring long-term anticoagulation (eg, mechanical prosthetic heart valves).111 For patients with prior VTE, determining whether the VTE was unprovoked or provoked helps in determining the need for anticoagulation during pregnancy.

-

•

Avoid estrogen-containing contraceptives. Patients with a history of pregnancy-associated VTE should not take estrogen-containing contraceptives or products post partum because these medications dramatically increase the risk of recurrent VTE.

-

•

Consult obstetrics, vascular medicine, or hematology specialists. A thorough discussion between PCPs and subspecialists is needed before discontinuation of anticoagulation for pregnancy-provoked VTE.

-

10.

Peripartum cardiomyopathy

Peripartum cardiomyopathy occurs in approximately 1 in 1000 to 1 in 4000 pregnancies in the United States.112 This clinical syndrome involves new left ventricular dysfunction in the final month of pregnancy or within 5 months post partum.112,113 Diagnosis can be difficult because the clinical signs and symptoms of heart failure overlap with the normal physiologic changes of pregnancy. Risk factors for PPCM include advanced maternal age, multiple gestation, and preeclampsia. The prevalence of PPCM is also higher among Black patients.112 Importantly, PPCM is a diagnosis of exclusion and may be clinically indistinguishable from other causes of heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. The diagnosis requires a high level of clinical suspicion, and a history of recent pregnancy and investigation into the aforementioned pregnancy-related risk factors are key to diagnosis. In the presence of symptoms and risk factors, PCPs should consider PPCM and aid in diagnosis, initial work-up, and referral to a cardiologist.

-

•

Initiate diagnostic work-up. Patients within 6 months of delivery presenting with signs or symptoms of left ventricular dysfunction (eg, worsening edema, orthopnea, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, dyspnea on exertion, or jugular venous distention) need echocardiography, electrocardiography, chest imaging, measurement of N-terminal pro–B-type natriuretic peptide (to identify early diastolic dysfunction),114,115 complete blood count, urinalysis, and complete metabolic panel.112,116

-

•

Treat PPCM with common heart failure medications in the postpartum period. Medical therapy for PPCM is identical to that for other forms of heart failure with reduced ejection fraction and includes ACE inhibitors, ARBs, beta blockers, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists, diuretics, and other therapies.112

-

•

Refer to cardiology provider. All patients with PPCM need referral to a cardiologist, preferably one specializing in heart failure.

Conclusion

Primary care providers are in a unique position to improve maternal and fetal outcomes through the provision of quality interconception care for patients with or at risk for medical comorbidities. They can also increase collaboration with obstetricians, MFM physicians, and subspecialists to enhance communication during transitions of care, create opportunities to engage in multidisciplinary co-management, and reinforce the shared mission of ensuring that patients experiencing pregnancy live healthy and fulfilled lives through pregnancy and beyond.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Kimberly Lawler (Graphic Arts, Department of Art as Applied to Medicine, The Johns Hopkins School of Medicine) for her work on the figures included in this manuscript.

Potential Competing Interests: The authors report no competing interests.

The maternal mortality ratio is the number of maternal deaths per 100,000 live births.

We use patients as a gender-inclusive term that includes all people with a uterus and the capacity for pregnancy. In some places, the word woman or women is used in directly referencing titles of previous reports.

Small for gestational age and low birth weight are also important CVD risk factors, but recall among mothers varies considerably.117, 118, 119

Some evidence suggests that mothers who had preterm births should not use ACE inhibitors.

Supplemental material can be found online at http://mcpiqojournal.org. Supplemental material attached to journal articles has not been edited, and the authors take responsibility for the accuracy of all data.

See Table 1 for definition of preeclampsia.

Supplemental Online Material

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Reproductive health. Pregnancy mortality surveillance system. https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternalinfanthealth/pmss.html

- 2.GBD 2015 Maternal Mortality Collaborators Global, regional, and national levels of maternal mortality, 1990-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015 [erratum appears in Lancet. 2017;389(10064):e1] Lancet. 2016;388(10053):1775–1812. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31470-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martin N., Montagne R. U.S. has the worst rate of maternal deaths in the developed world. NPR. https://www.npr.org/2017/05/12/528098789/u-s-has-the-worst-rate-of-maternal-deaths-in-the-developed-world Published May 12, 2017.Accessed May 8, 2020.

- 4.Howell E.A. Reducing disparities in severe maternal morbidity and mortality. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2018;61(2):387–399. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0000000000000349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Azeez O., Kulkarni A., Kuklina E.V., Kim S.Y., Cox S. Hypertension and diabetes in non-pregnant women of reproductive age in the United States. Prev Chronic Dis. 2019;16(10):190105. doi: 10.5888/pcd16.190105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Admon L.K., Winkelman T.N.A., Moniz M.H., Davis M.M., Heisler M., Dalton V.K. Disparities in chronic conditions among women hospitalized for delivery in the United States, 2005-2014. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130(6):1319–1326. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Building U.S Capacity to Review and Prevent Maternal Deaths. Report from nine maternal mortality review committees. http://reviewtoaction.org/Report_from_Nine_MMRCs

- 8.Atrash H.K., Johnson K., Adams M., Cordero J.F., Howse J. Preconception care for improving perinatal outcomes: the time to act. Matern Child Health J. 2006;10(5, suppl):S3–S11. doi: 10.1007/s10995-006-0100-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frayne D.J. A paradigm shift in preconception and interconception care. Using every encounter to improve birth outcomes. https://beforeandbeyond.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/Zero-to-Three-Article-for-Dr.-Frayne.pdf

- 10.Bryant A., Ramos D., Stuebe A., Blackwell S.C. Obstetric Care Consensus No. 8: interpregnancy care. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133(1):e51–e72. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.ACOG Committee Opinion No. 736: optimizing postpartum care. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131(5):e140–e150. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rosener S.E., Barr W.B., Frayne D.J., Barash J.H., Gross M.E., Bennett I.M. Interconception care for mothers during well-child visits with family physicians: an IMPLICIT network study. Ann Fam Med. 2016;14(4):350–355. doi: 10.1370/afm.1933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rich-Edwards J.W. Reproductive health as a sentinel of chronic disease in women. Womens Health (Lond) 2009;5(2):101–105. doi: 10.2217/17455057.5.2.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rich-Edwards J.W., Fraser A., Lawlor D.A., Catov J.M. Pregnancy characteristics and women’s future cardiovascular health: an underused opportunity to improve women’s health? Epidemiol Rev. 2014;36(1):57–70. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxt006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Long M., Frederiksen B., Ranji U., Salganicoff A. Women’s health care utilization and costs: findings from the 2020 Kaiser Family Foundation Women’s Health Survey. https://www.kff.org/womens-health-policy/issue-brief/womens-health-care-utilization-and-costs-findings-from-the-2020-kff-womens-health-survey/

- 16.Stormo A.R., Saraiya M., Hing E., Henderson J.T., Sawaya G.F. Women’s clinical preventive services in the United States: who is doing what? JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(9):1512–1514. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.3003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Texas Department of State Health Services Maternal Mortality and Morbidity Task Force and Department of State Health Services joint biennial report. July 2016. https://www.dshs.texas.gov/mch/pdf/2016BiennialReport.pdf Accessed January 4, 2019.

- 18.Texas Department of State Health Services Maternal Mortality and Morbidity Task Force and Department of State Health Services joint biennial report. September 2018. https://www.dshs.texas.gov/mch/pdf/MMMTFJointReport2018.pdf Accessed January 3, 2019.

- 19.Smith G.N., Sadde G. Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine white paper: pregnancy as a window to future health. https://www.smfm.org/publications/141-smfm-white-paper-pregnancy-as-a-window-to-future-health

- 20.Brown H.L., Warner J.J., Gianos E., Gulati M., Hill A.J., Hollier L.M. Promoting risk identification and reduction of cardiovascular disease in women through collaboration with obstetricians and gynecologists: a presidential advisory from the American Heart Association and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Circulation. 2018;137(24):e843–e852. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Conway T., Mason E., Hu T.C. Attitudes, knowledge, and skills of internal medicine residents regarding pre-conception care. Acad Med. 1994;69(5):389–391. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199405000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hsieh E., Nunez-Smith M., Henrich J.B. Needs and priorities in women’s health training: perspectives from an internal medicine residency program. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2013;22(8):667–672. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2013.4264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Petterson S., McNellis R., Klink K., Meyers D., Bazemore A. The state of primary care in the United States: a chartbook of facts and statistics. January 2018. www.graham-center.org/content/dam/rgc/documents/publications-reports/reports/PrimaryCareChartbook.pdf

- 24.Daniel H., Erickson S.M., Bornstein S.S., Health and Public Policy Committee of the American College of Physicians Women’s health policy in the United States: an American College of Physicians position paper. Ann Intern Med. 2018;168(1):874–875. doi: 10.7326/M17-3344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thagard A.S., Napolitano P.G., Bryant A.S. The role of extremes in interpregnancy interval in women at increased risk for adverse obstetric outcomes due to health disparities: a literature review. Curr Womens Health Rev. 2018;14(3):242–250. doi: 10.2174/1573404813666170323154244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gebremedhin A.T., Regan A.K., Malacova E., Marinovich M.L., Ball S., Foo D. Effects of interpregnancy interval on pregnancy complications: protocol for systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2018;8(8):25008. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-025008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.ACOG Committee Opinion No. 762 summary: prepregnancy counseling. Am Coll Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133(1):228–230. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schreiber C.A., Barnhart K. In: Yen and Jaffe's Reproductive Endocrinology. (Eighth Edition). Strauss J.F. III, Barbieri R.L., Antonio R., Gargiulo A.R., editors. Elsevier; Philadelphia: 2019. Contraception; pp. 962–978.e4. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Curtis K.M., Tepper N.K., Jatlaoui T.C., Berry-Bibee E., Horton L.G., Zapata L.B. U.S. medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65(3):1–103. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.rr6503a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Contraception. Apps on Google Play. https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=gov.cdc.ondieh.nccdphp.contraception2&hl=en_US&gl=US

- 31.Contraception on the App Store. https://apps.apple.com/us/app/contraception/id595752188

- 32.Catov J.M., Bairey-Merz N., Rich-Edwards J. Cardiovascular health during pregnancy: future health implications for mothers. Curr Epidemiol Rep. 2017;4:232–238. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Carter E.B., Stuart J.J., Farland L.V., Rich-Edwards J.W., Zera C.A., McElrath T.F. Pregnancy complications as markers for subsequent maternal cardiovascular disease: validation of a maternal recall questionnaire. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2015;24(9):702–712. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2014.4953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stuart J.J., Noel Bairey Merz C., Berga S.L., Miller V.M., Ouyang P., Shufelt C.L. Maternal recall of hypertensive disorders in pregnancy: a systematic review. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2013;22(1):37–47. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2012.3740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Adam M.P., Polifka J.E., Friedman J.M. Evolving knowledge of the teratogenicity of medications in human pregnancy. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2011;157C(3):175–182. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.30313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Matsui D. Adherence with drug therapy in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol Int. 2012;2012:796590. doi: 10.1155/2012/796590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chase J., Oza K., Goldman S. Email-based care transitions to improve patient outcomes and provider work experience in a safety-net health system. Am J Accountable Care. 2017;5(4):e19–e22. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bateman B.T., Shaw K.M., Kuklina E.V., Callaghan W.M., Seely E.W. Hypertension in women of reproductive age in the United States: NHANES 1999-2008. PLoS One. 2012;7(4):e36171. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists' Committee on Practice Bulletins—Obstetrics ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 203: chronic hypertension in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133(1):e26–e50. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ananth C.V., Duzyj C.M., Yadava S., Schwebel M., Tita A.T.N., Joseph K.S. Changes in the prevalence of chronic hypertension in pregnancy, United States, 1970 to 2010. Hypertension. 2019;74(5):1089–1095. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.119.12968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bramham K., Parnell B., Nelson-Piercy C., Seed P.T., Poston L., Chappell L.C. Chronic hypertension and pregnancy outcomes: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2014;348:g2301. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g2301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Seely E.W., Ecker J. Chronic hypertension in pregnancy. Circulation. 2014;129(11):1254–1261. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.003904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bramham K., Briley A.L., Seed P., Poston L., Shennan A.H., Chappell L.C. Adverse maternal and perinatal outcomes in women with previous preeclampsia: a prospective study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;204(6):512.e1–512.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Panaitescu A.M., Syngelaki A., Prodan N., Akolekar R., Nicolaides K.H. Chronic hypertension and adverse pregnancy outcome: a cohort study. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2017;50(2):228–235. doi: 10.1002/uog.17493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hypertension in pregnancy. Report of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Task Force on Hypertension in Pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122(5):1122–1131. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000437382.03963.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Reddy S., Jim B. Hypertension and pregnancy: management and future risks. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2019;26(2):137–145. doi: 10.1053/j.ackd.2019.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mehta L.S., Warnes C.A., Bradley E., Burton T., Economy K., Mehran R. American Heart Association Council on Clinical Cardiology; Council on Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis and Vascular Biology; Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing; and Stroke Council. Cardiovascular considerations in caring for pregnant patients: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association [erratum appears in Circulation. 2021;143(12):e792-e793] Circulation. 2020;141(23):e884–e903. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.ACOG Committee Opinion No. 743: low-dose aspirin use during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132(1):e44–e52. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.O’Connor C.M. High heart failure readmission rates: is it the health system’s fault? JACC Heart Fail. 2017;5(5):393. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2017.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sisti G., Colombi I. New blood pressure cut off for preeclampsia definition: 130/80 mmHg. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2019;240:322–324. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2019.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Darwin K.C., Federspiel J.J., Schuh B.L., Baschat A.A., Vaught A.J. ACC-AHA diagnostic criteria for hypertension in pregnancy identifies patients at intermediate risk of adverse outcomes. Am J Perinatol. 2021;38(S 01):e249–e255. doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1709465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hu J., Li Y., Zhang B., Zheng T., Li J., Peng Y. Impact of the 2017 ACC/AHA guideline for high blood pressure on evaluating gestational hypertension-associated risks for newborns and mothers. Circ Res. 2019;125(2):184–194. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.119.314682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Whelton P.K., Carey R.M., Aronow W.S., Casey D.E., Jr., Collins K.J., Dennison Himmelfarb C. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71(19):e127–e248. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Katsi V., Skalis G., Vamvakou G., Tousoulis D., Makris T. Postpartum hypertension. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2020;22(8):58. doi: 10.1007/s11906-020-01058-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Drugs Transfer of drugs and other chemicals into human milk. Pediatrics. 2001;108(3):776–789. doi: 10.1542/peds.108.3.776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Drugs and Lactation Database: LactMed. J Electronic Resources Med Libr. 2012;9(4):272–277. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sachs H.C. The transfer of drugs and therapeutics into human breast milk: an update on selected topics. Pediatrics. 2013;132(3):e796–e809. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wu P., Haththotuwa R., Kwok C.S., Babu A., Kotronias R.A., Rushton C. Preeclampsia and future cardiovascular health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2017;10(2):e003497. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.116.003497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Barrett P.M., McCarthy F.P., Kublickiene K., Cormican S., Judge C., Evans M. Adverse pregnancy outcomes and long-term maternal kidney disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(2):e1920964. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.20964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Weissgerber T.L., Mudd L.M. Preeclampsia and diabetes. Curr Diab Rep. 2015;15(3):9. doi: 10.1007/s11892-015-0579-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Spaan J., Peeters L., Spaanderman M., Brown M. Cardiovascular risk management after a hypertensive disorder of pregnancy. Hypertension. 2012;60(6):1368–1373. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.112.198812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ying W., Catov J.M., Ouyang P., Hopkins J. Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy and future maternal cardiovascular risk classification and epidemiology of HDP. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7(17):e009382. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.118.009382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists' Committee on Practice Bulletins—Obstetrics ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 201: pregestational diabetes mellitus. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132(6):e228–e248. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Alexopoulos A.S., Blair R., Peters A.L. Management of preexisting diabetes in pregnancy: a review. JAMA. 2019;321(18):1811–1819. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.4981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.American Diabetes Association Standards of medical care in diabetes—2019 abridged for primary care providers. Clin Diabetes. 2019;37(1):11–34. doi: 10.2337/cd18-0105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.US Preventive Services Task Force. Bibbins-Domingo K., Grossman D.C., Curry S.J., Davidson K.W., Epling J.W., Jr., García F.A. Folic acid supplementation for the prevention of neural tube defects: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2017;317(2):183–189. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.19438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Practice Bulletin No. 187 summary: neural tube defects. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130(6):1394–1396. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.American Diabetes Association 13. Management of diabetes in pregnancy: standards of medical care in diabetes—2018. Diabetes Care. 2018;41(suppl 1):S137–S143. doi: 10.2337/dc18-S013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Baker J.L., Gamborg M., Heitmann B.L., Lissner L., Sørensen T.I., Rasmussen K.M. Breastfeeding reduces postpartum weight retention. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;88(6):1543–1551. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2008.26379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kaul P., Bowker S.L., Savu A., Yeung R.O., Donovan L.E., Ryan E.A. Association between maternal diabetes, being large for gestational age and breast-feeding on being overweight or obese in childhood. Diabetologia. 2019;62(2):249–258. doi: 10.1007/s00125-018-4758-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Martens P.J., Shafer L.A., Dean H.J., Sellers E.A.C., Yamamoto J., Ludwig S. Breastfeeding initiation associated with reduced incidence of diabetes in mothers and offspring [erratum appears in Obstet Gynecol. 2017;129(2):394-395] Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128(5):1095–1104. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wendland E.M., Torloni M.R., Falavigna M., Trujillo J., Dode M.A., Campos M.A. Gestational diabetes and pregnancy outcomes—a systematic review of the World Health Organization (WHO) and the International Association of Diabetes in Pregnancy Study Groups (IADPSG) diagnostic criteria. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2012;12:23. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-12-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bellamy L., Casas J.P., Hingorani A.D., Williams D. Type 2 diabetes mellitus after gestational diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2009;373(9677):1773–1779. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60731-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kaul P., Savu A., Nerenberg K.A., Donovan L.E., Chik C.L., Ryan E.A. Impact of gestational diabetes mellitus and high maternal weight on the development of diabetes, hypertension and cardiovascular disease: a population-level analysis. Diabet Med. 2015;32(2):164–173. doi: 10.1111/dme.12635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Carr D.B., Utzschneider K.M., Hull R.L., Tong J., Wallace T.M., Kodama K. Gestational diabetes mellitus increases the risk of cardiovascular disease in women with a family history of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2006;29(9):2078–2083. doi: 10.2337/dc05-2482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kramer C.K., Campbell S., Retnakaran R. Gestational diabetes and the risk of cardiovascular disease in women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetologia. 2019;62(6):905–914. doi: 10.1007/s00125-019-4840-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 190: gestational diabetes mellitus. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131(2):e49–e64. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Flegal K.M., Carroll M.D., Kit B.K., Ogden C.L. Prevalence of obesity and trends in the distribution of body mass index among US adults, 1999-2010. JAMA. 2012;307(5):491–497. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.LifeCycle Project–Maternal Obesity and Childhood Outcomes Study Group. Voerman E., Santos S., Inskip H., Amiano P., Barros H., Charles M.A. Association of gestational weight gain with adverse maternal and infant outcomes. JAMA. 2019;321(17):1702–1715. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.3820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Waring M.E., Moore Simas T.A., Rosal M.C., Pagoto S.L. Pregnancy intention, receipt of pre-conception care, and pre-conception weight counseling reported by overweight and obese women in late pregnancy. Sex Reprod Healthc. 2015;6(2):110–111. doi: 10.1016/j.srhc.2015.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.McDermott M.M., Brubaker L. Prepregnancy body mass index, weight gain during pregnancy, and health outcomes. JAMA. 2019;321(17):1715. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.3821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Delcore L., LaCoursiere D.Y. Preconception care of the obese woman. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2016;59(1):129–139. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0000000000000182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Price S.A., Sumithran P., Nankervis A., Permezel M., Proietto J. Preconception management of women with obesity: a systematic review. Obes Rev. 2019;20(4):510–526. doi: 10.1111/obr.12804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ogunwole S.M., Zera C.A., Stanford F.C. Obesity management in women of reproductive age. JAMA. 2021;325(5):433–434. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.21096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Broughton D.E., Moley K.H. Obesity and female infertility: potential mediators of obesity’s impact. Fertil Steril. 2017;107(4):840–847. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2017.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 156: obesity in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126(6):e112–e126. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Khera R., Murad M.H., Chandar A.K., Dulai P.S., Wang Z., Prokop L.J. Association of pharmacological treatments for obesity with weight loss and adverse events a systematic review and meta-analysis [erratum appears in JAMA. 2016;316(9):995] JAMA. 2016;315(22):2424–2434. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.7602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Yi X.Y., Li Q.F., Zhang J., Wang Z.H. A meta-analysis of maternal and fetal outcomes of pregnancy after bariatric surgery. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2015;130(1):3–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2015.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Smith J., Cianflone K., Biron S., Hould F.S., Lebel S., Marceau S. Effects of maternal surgical weight loss in mothers on intergenerational transmission of obesity. Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94(11):4275–4283. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-0709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 105: bariatric surgery and pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113(6):1405–1413. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181ac0544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Falcone V., Stopp T., Feichtinger M., Kiss H., Eppel W., Husslein P.W. Pregnancy after bariatric surgery: a narrative literature review and discussion of impact on pregnancy management and outcome. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018;18(1):507. doi: 10.1186/s12884-018-2124-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Luke S., Kirby R.S., Wright L. Postpartum weight retention and subsequent pregnancy outcomes. J Perinat Neonatal Nurs. 2016;30(4):292–301. doi: 10.1097/JPN.0000000000000160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Gilmore L.A., Klempel-Donchenko M., Redman L.M. Pregnancy as a window to future health: excessive gestational weight gain and obesity. Semin Perinatol. 2015;39(4):296–303. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2015.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Schmitt N.M., Nicholson W.K., Schmitt J. The association of pregnancy and the development of obesity—results of a systematic review and meta-analysis on the natural history of postpartum weight retention. Int J Obes (Lond) 2007;31(11):1642–1651. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Institute of Medicine (US) and National Research Council (US). Committee to Reexamine IOM Pregnancy Weight Guidelines; Rasmussen KM, Yaktine AL, eds. Weight Gain During Pregnancy: Reexamining the Guidelines. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2009. [PubMed]

- 96.Piccoli G.B., Attini R., Vasario E., Conijn A., Biolcati M., D'Amico F. Pregnancy and chronic kidney disease: a challenge in all CKD stages. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5(5):844–855. doi: 10.2215/CJN.07911109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Piccoli G.B., Cabiddu G., Attini R., Vigotti F.N., Maxia S., Lepori N. Risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes in women with CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;26(8):2011–2022. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2014050459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Jones D.C., Hayslett J.P. Outcome of pregnancy in women with moderate or severe renal insufficiency [erratum appears in N Engl J Med. 1997;336(10):739] N Engl J Med. 1996;335(4):226–232. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199607253350402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Qaseem A., Hopkins R.H., Sweet D.E., Starkey M., Shekelle P. Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians. Screening, monitoring, and treatment of stage 1 to 3 chronic kidney disease: a clinical practice guideline from the Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159(12):835–847. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-159-12-201312170-00726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Understanding task force recommendations: screening for chronic kidney disease. http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/chronic-kidney-disease-ckd-screening Accessed June 22, 2021.

- 101.National Kidney Foundation National Kidney Foundation, Renal Physicians Association urge screening for those at risk for kidney disease. https://www.kidney.org/news/newsroom/nr/NKF-RPA-Urge-Screening-for-atRisk-KD

- 102.Smyth A., Oliveira G.H., Lahr B.D., Bailey K.R., Norby S.M., Garovic V.D. A systematic review and meta-analysis of pregnancy outcomes in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus and lupus nephritis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5(11):2060–2068. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00240110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Clowse M.E., Richeson R.L., Pieper C., Merkel P.A. Vasculitis Clinical Research Consortium. Pregnancy outcomes among patients with vasculitis. Arthritis Care Res. 2013;65(8):1370–1374. doi: 10.1002/acr.21983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Fredi M., Lazzaroni M.G., Tani C., Ramoni V., Gerosa M., Inverardi F. Systemic vasculitis and pregnancy: a multicenter study on maternal and neonatal outcome of 65 prospectively followed pregnancies. Autoimmun Rev. 2015;14(8):686–691. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2015.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Galdo T., González F., Espinoza M., Quintero N., Espinoza O., Herrera S. Impact of pregnancy on the function of transplanted kidneys. Transplant Proc. 2005;37(3):1577–1579. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2004.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Gutiérrez M.J., Acebedo-Ribó M., García-Donaire J.A., Manzanera M.J., Molina A., González E. Pregnancy in renal transplant recipients. Transplant Proc. 2005;37(9):3721–3722. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2005.09.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Clay E.C., Seehusen D.A. A review of postpartum depression for the primary care physician. South Med J. 2004;97(2):157–161. doi: 10.1097/01.SMJ.0000091029.34773.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Gjerdincjen D., Crow S., McGovern P., Miner M., Center B. Postpartum depression screening at well-child visits: validity of a 2-question screen and the PHQ-9. Ann Fam Med. 2009;7(1):63–70. doi: 10.1370/afm.933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Viguera A. Severe postpartum unipolar major depression: choosing treatment. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/severe-postpartum-unipolar-major-depression-choosing-treatment

- 110.ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 196: thromboembolism in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132(1):e1–e17. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]