Version Changes

Revised. Amendments from Version 1

The authors looked into the reviewers' valuable comments and took into consideration their recommended changes to improve the systematic review. Minor changes have been suggested by one of the reviewers. These minor changes include adding citations suggested by the reviewer which can add a broad idea about the topic. These citations were added to the background section of the review. The other change is suggested in the discussion section which has been modified according to the reviewer’s recommendation.

Abstract

Background: Acute type two respiratory failure (AT2RF) is characterized by high carbon dioxide levels (PaCO 2 >6kPa). Non-invasive ventilation (NIV), the current standard of care, has a high failure rate. High flow nasal therapy (HFNT) has potential additional benefits such as CO 2 clearance, the ability to communicate and comfort. The primary aim of this systematic review is to determine whether HFNT in AT2RF improves 1) PaCO 2, 2) clinical and patient-centred outcomes and 3) to assess potential harms.

Methods: We searched EMBASE, MEDLINE and CENTRAL (January 1999-January 2021). Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and cohort studies comparing HFNT with low flow nasal oxygen (LFO) or NIV were included. Two authors independently assessed studies for eligibility, data extraction and risk of bias. We used Cochrane risk of bias tool for RCTs and Ottawa-Newcastle scale for cohort studies.

Results: From 727 publications reviewed, four RCTs and one cohort study (n=425) were included. In three trials of HFNT vs NIV, comparing PaCO 2 (kPa) at last follow-up time point, there was a significant reduction at four hours (1 RCT; HFNT median 6.7, IQR 5.6 – 7.7 vs NIV median 7.6, IQR 6.3 – 9.3) and no significant difference at 24-hours or five days. Comparing HFNT with LFO, there was no significant difference at 30-minutes. There was no difference in intubation or mortality.

Conclusions: This review identified a small number of studies with low to very low certainty of evidence. A reduction of PaCO 2 at an early time point of four hours post-intervention was demonstrated in one small RCT. Significant limitations of the included studies were lack of adequately powered outcomes and clinically relevant time-points and small sample size. Accordingly, systematic review cannot recommend the use of HFNT as the initial management strategy for AT2RF and trials adequately powered to detect clinical and patient-relevant outcomes are urgently warranted.

Keywords: High flow nasal oxygen, high flow nasal therapy, acute type 2 respiratory failure, acute hypercapnic respiratory failure, acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

Introduction

Background

Acute type two respiratory failure (AT2RF) is characterised by arterial hypercapnia (PaCO 2 >6 kPa or >45 mmHg) and its treatment requires ventilator support in a significant proportion of cases. 1 Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is the second-most widespread disease in the UK, with 1,201,685 cases reported in 2013. Acute exacerbations of COPD (AECOPD) account for 100,000 admissions annually in England. Of these, around 20% will present with or develop hypercapnia, an indicator of increased risk of death. 2, 3 Development of AT2RF in patients with COPD is associated with a significantly increased risk for requiring invasive ventilation and mortality rate, 4, 5 with mortality rates up to 15% in patients who require admission to the intensive care unit (ICU).

The treatment of AT2RF is aimed at the underlying pathological processes such as fluid overload, bronchospasm and infection along with controlled oxygen therapy, to decrease the work of breathing. Patients often require ventilator support that may be non-invasive ventilation (NIV) or invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV). Current guidelines recommend the use of NIV. 1 Current evidence has established the role of NIV in improving arterial oxygenation, hypercapnia, acidosis, mortality and intubation rates. 6 However, the NIV failure rate ranges from 15 to 25%, with some evidence stating a failure rate as high as 60%. 7– 10 The factors leading to NIV failure include non-compliance due to claustrophobia, delirium, sputum retention, reduced communication and skin compromise such as skin necrosis in the nasal bridge. 1, 10, 11

High flow nasal oxygen or insufflation (described as high flow nasal therapy (HFNT) in this manuscript) is novel respiratory support that integrates humidified air with a high flow rate of up to 60 L/minute. Reported benefits from HFNT include consistent fractional inspired oxygen delivery, dead space washout, reduced work of breath, comfort and tolerability, ability to communicate, mucous clearance and NIV-like effects, which makes it a more tolerable method for patients. 12– 15 In type I ARF with different aetiologies, HFNT has been demonstrated to lead to improved oxygenation, lower rates of endotracheal intubations and lower mortality. 16, 17

In the last 10 years, evidence has emerged for its increasing use and a role for these modalities in clinical practice for the treatment of AT2RF. 15, 18 Several observational studies have suggested potential benefits of HFNT for AT2RF as demonstrated by improved gas exchange and acidosis, 19, 20 and reductions in the respiratory rate and work of breathing. 21– 23 Individual studies have shown that HFNT improves blood gas levels in AT2RF patients 22– 25 and is associated with improved comfort. 24

Why this review is important

Adequate respiratory support through controlled oxygen, reduced work of breathing and CO 2 clearance is essential to prevent intubation and invasive ventilation. NIV, despite its frequent use, has limitations and a high failure rate. HFNT might overcome the limitations of NIV and could be used in AT2RF patients as an initial intervention or in patients who do not tolerate NIV. Despite the increase in current literature suggesting benefits from the use of HFNT in AT2RF, current evidence is limited. Other systematic reviews are exploring the use of HFNT for the management of AT2RF post-extubation and after initial stabilization of the patient using a respiratory optimisation method like NIV or LFO. 26- 28 However, there is no systematic review that focuses on the use of HFNT as an initial management strategy for AT2RF.

Objectives

The primary objective of this systematic review was to determine whether the use of HFNT for patients with AT2RF improves PaCO 2 in comparison to LFO or NIV. Secondary objectives were to examine whether HFNT in patients with AT2RF improves other clinical or patient-centred outcomes and to assess any potential harms.

Methods

The systematic review was registered in the PROSPERO database ( CRD42019148748, 05/09/2019) and published a priori. We conducted this systematic review according to the PRISMA guidelines (see Reporting guidelines). 29, 30

Eligibility criteria

Randomized controlled trials, uncontrolled trials and cohort studies were included if they compared the use of HFNT with a flow rate >20 L/minutes versus LFO or NIV. We included studies of adult (≥18 years old) patients with AT2RF (>6 kPa or >45 mmHg) managed as inpatients in an acute care setting (emergency department, respiratory ward or critical care units). We excluded reports that described the use of HFNT in peri-operative settings, drug overdose, or ventilator weaning.

Outcomes

The primary outcome for this review was the change in PaCO 2 post-intervention (measured at time points reported by authors). The secondary outcomes were: respiratory parameters including pH, the partial arterial pressure of oxygen (PaO 2), dyspnoea score, tidal volume and minute volume; mucous clearance (before, during or after HFNT application); the level of consciousness; patient comfort; intubation rate; length of stay in hospital; mortality; post-discharge COPD exacerbation rate and readmission rate secondary to AECOPD.

Search strategy

We searched the electronic databases MEDLINE, EMBASE and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials from January 1999 to January 2021. The databases search was conducted on 15/01/2021. Language restrictions were not applied. In addition, we searched Google Scholar and references of all articles for any additional studies. With the assistance of a professional librarian, we developed a systematic search strategy using appropriate keywords and MeSH terms and these are detailed in the data availability section (see Extended data). 30 The systematic review software management system Covidence was used to store citations, remove duplication and aid screening.

Selection of studies

Two review authors (AAA and MS) independently screened the titles and abstracts of all citations. The full texts of all potentially eligible studies were independently reviewed for inclusion confirmation. Any disagreement was resolved through discussion within the review team.

Data extraction

Data were independently extracted from included studies using a standardized data extraction form by two reviewers (AAA and MS). The information extracted included type and setting of the study, recruitment information, participant characteristics (age and underlying conditions), inclusion criteria, nature of interventions, in each group (e.g. flow rate and method of delivery), time-points of measurement and outcomes. Any disagreement was resolved through discussion with BB. Data that were unavailable or insufficient from publications were requested from study authors.

Two reviewers (AAA and MS) independently assessed the quality of included studies using the Cochrane risk of bias tool for RCTs and the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for cohort studies. 31, 32 Each potential source of bias was marked as high, low or unclear. We assessed the quality of the evidence associated with HFNT for AT2RF using GRADE to determine the strength of the evidence into one of four grades: high, moderate, low or very low. 33 The quality of evidence is reported in the Summary of Findings (SOF) tables ( Tables 1, 2, 3).

Table 1. Summary of findings: High flow nasal therapy versus non-invasive ventilation for acute hypercapnic respiratory failure.

| Patient or population: Acute hypercapnic respiratory failure patient

Setting: Acute Care Intervention: HFNT Comparison: NIV | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes | Interventions | MD

*/

OR * (95%)/p-value |

№ of participants analyzed

(studies) |

The certainty of the evidence

(GRADE) |

|

| NIV

*

Median (IQR *) or mean (SD *) |

HFNT

*

Median (IQR *) or mean (SD *) |

||||

|

Primary outcome a. PaCO 2 (kPa *) 34 time-point: 4 hours |

7.6 (6.3 – 9.3) | 6.7 (5.6 – 7.7) | P = 0.03 | 65 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊕O

Moderate 2 |

| b. PaCO

2 (kPa

*)

36

time-point: 6 hours |

7.7 (1.6) | 8.5 (2) | MD 0.80 [0.00, 1.60] | 88 (1 RCT) | ⊕OOO

Very Low 2,4 |

| c. PaCO

2 (kPa

*)

23

time-point: 24 hours |

6.6 (1.9) | 6.3 (2.1) | MD −0.30 [−1.14, 0.54] | 88 (1 Cohort) | ⊕OOO

Very Low 2,3 |

| d. PaCO

2 (kPa

*)

35

time-point: 5 days |

8 (1.9) | 7.8 (1.9) | MD −0.20 [−0.77, 0.37] | 165 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊕O

Moderate 2 |

|

Secondary outcome (continuous data) a. PaO 2 (kPa *) 34 time-point: 4 hours |

11.7 (10.3 – 12.9) | 11.1 (5.3 – 13.2) | P = 0.71 | 65 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊕O

Moderate 2 |

| b. PaO

2 (kPa

*)

36

time-point: 6 hours |

‡N/R | ‡N/R | ‡N/R | 88 (1 RCT) | ⊕OOO

Very Low 2,4 |

| c. PaO

2 (kPa

*)

23

time-point: 24 hours |

11.3 (3.1) | 11.2 (2.5) | MD −0.10 [−1.28, 1.08] | 88 (1 Cohort) | ⊕OOO

Very Low 2,3 |

| d. PaO

2 (kPa

*)

35

time-point: 5 days |

‡11 (2.1) | ‡10.9 (2) | ‡MD −0.10 [0.72, 0.52] | 165 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊕O

Moderate 2 |

| e. pH

34

time-point: 4 hours |

7.35 (7.3-7.4) | 7.4 (7.3-7.4) | P = 0.24 | 65 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊕O

Moderate 2 |

| f. pH

36

time-point: 6 hours |

N/R ‡ | N/R ‡ | N/R ‡ | 88 (1 RCT) | ⊕OOO

Very Low 2,4 |

| g. pH

23

time-point: 24 hours |

7.4 (0.1) | 7.4 (0.1) | MD 0.00 [−0.03, 0.03] | 88 (1 Cohort) | ⊕⊕OO

Low 3 |

| h. pH

35

time-point: 5 days |

7.4 (0.1) ‡ | 7.35 (0.1) ‡ | MD −0.05 [0.08, 0.01] ‡ | 165 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊕O

Moderate 2 |

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence

High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | |||||

| Explanation

1- Downgraded for indirectness because of the study population 2- Downgraded for imprecision for a wide confidence interval, the small sample size 3- Downgraded for study design (non-RCT) 4- Downgraded for risk of bias | |||||

Abbreviations: HFNT, High flow nasal therapy; IQR, Interquartile range; kPa, Kilopascal; MD, mean difference; NIV, Non-invasive ventilation; OR, Odd ratio; SD, Standard deviation.

N/R - Not reported.

Table 2. Summary of findings: High flow nasal therapy versus non-invasive ventilation for acute hypercapnic respiratory failure.

| Patient or population: Acute hypercapnic respiratory failure patient

Setting: Acute Care Intervention: HFNT Comparison: NIV | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes | Interventions | MD */OR * (95%)/p-value | № of participants analyzed

(studies) |

The certainty of the evidence

(GRADE) |

Comments | |

| NIV

*

n/N * |

HFNT

*

n/N * |

|||||

|

Secondary outcome (Dichotomous data) a. Mortality rate 23 time-point: 30-day |

44/8 | 44/7 | OR 0.85 [0.28, 2.59] | 88 (1 Cohort) | ⊕⊕OO

Low 3 |

|

| b. Mortality rate

36

time-point: in-hospital mortality |

39/6 | 40/2 | OR 0.29 [0.05, 1.53] | 80 (1RCT) | ⊕⊕⊕O

Moderate 2 |

The study didn’t provide the time-point for mortality. |

| c. Intubation rate

36

time-points: 6 hours |

39/1 | 40/1 | OR 0.97 [0.06, 16.14] | 80 (1RCT) | ⊕⊕⊕O

Moderate 2 |

|

| d. Intubation rate

34

time-point: 72 hours |

31/5 | 34/2 | OR 0.33 [0.06, 1.81] | 65 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊕O

Moderate 2 |

|

| e. Intubation rate

23

time-points: 30-day |

44/12 | 44/11 | OR 0.89 [0.34, 2.30] | 88 (1 Cohort) | ⊕⊕OO

Low 3 |

|

| f. Dysponea 34, 36 | - | - | - | 145 (2RCTs) | - | Dyspnoea was measured by 2 studies at various time points. It was assessed by modified Borg. |

| g. Patient comfort 35, 36 | - | - | - | 245 (2 RCTs) | - | Comfort was measured by 2 studies at various time points. It was assessed by a self-designed survey and a 10-point numerical rating scale. |

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence

High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

| Explanation

1- Downgraded for indirectness because of the study population 2- Downgraded for imprecision for a wide confidence interval, the small sample size 3- Downgraded for study design (non-RCT) 4- Downgraded for risk of bias | ||||||

Abbreviations: HFNT, High flow nasal therapy; IQR, Interquartile range; MD, mean difference; n/N, Number of patients NIV, Non-invasive ventilation; OR, Odd ratio; SD, Standard deviation.

Table 3. Summary of findings: High flow versus low flow nasal therapy for acute hypercapnic respiratory failure.

| Patient or population: Acute hypercapnic respiratory failure patient

Setting: Acute Care Intervention: HFNT Comparison: LFO | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes | Interventions | MD * (95%) | № of participants analysed

(studies) |

The certainty of the evidence

(GRADE) |

Comments | |

| LFO

*

Mean (SD *) |

HFNT

*

Mean (SD *) |

|||||

|

Primary outcome a. PaCO 2 (KPa *) 24 time-point: 30 minutes |

6.5 (1.3) | 6.3 (1.3) | -0.20 [-1.24, 0.84] | 24 (1 RCT) | ⊕OOO

Very low 2,4 |

|

|

Secondary outcome (continuous) a. Patient comfort 24 |

- | - | - | 24 (1 RCT) | ⊕OOO

Very Low 2,4 |

The questions used to assess patient comfort were not validated, and the sample size was low |

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence

High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

| Explanation

1- Downgraded for serious indirectness because of the study population 2- Downgraded for serious imprecision for a wide confidence interval, the small sample size 3- Downgraded for study design (non-RCT) 4- Downgraded for risk of bias | ||||||

Abbreviations: HFNT, High flow nasal therapy; LFO, kPa, Kilopascal; Low flow oxygen; MD, mean difference; SD, Standard deviation.

Data synthesis

Measurement of effect

RevMan software (Review Manager, version 5.3) was used for data analysis. Results are reported as odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for binary variables and mean differences (MD) with 95% CIs for continuous variables. A meta-analysis was planned, but there were insufficient studies and results are presented narratively.

Subgroup and sensitivity analysis

The planned subgroup analyses of patient conditions (COPD, neuromuscular disorders, and interstitial lung disease), and the planned sensitivity analysis excluding trials with a high risk of bias could not be undertaken due to the low number of trials.

Results

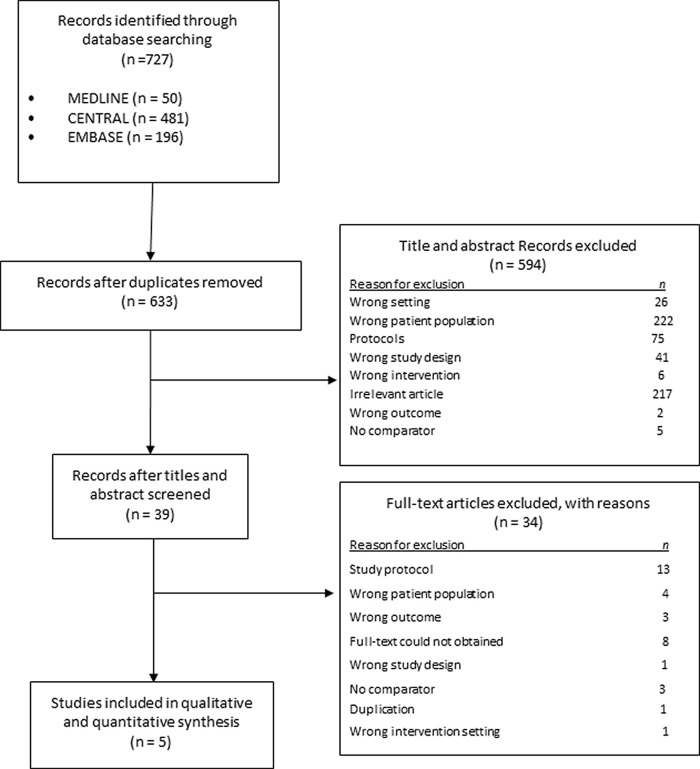

The search identified 727 records. Following the removal of duplicates and non-eligible studies, 39 full-text studies were screened and 34 studies were excluded. Five studies with 425 participants were included in this review ( Figure 1). 23, 24, 34– 36

Figure 1. PRISMA flowchart for study selection.

Study characteristics and risk of bias

The characteristics of the included studies are summarized in Table 4. Four studies were RCTs 23, 24, 34– 36 and one was a cohort study. 23 Four studies compared HFNT with NIV 23, 34– 36 and one RCT compared HFNT with LFO using simple nasal prongs. 24 The disease state of interest was an acute-moderate hypercapnic respiratory failure (n = 88) in one study, 23 and AECOPD (n = 337) in the remaining four studies. 24, 34– 36

Table 4. Study characteristics.

| Author and year | No. of participants | Country | Setting | Study design | Population | Intervention (flow rate L/min) | Control | Outcomes measured relevant for this review |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cortegiani et al. 36 2020 | 80 | Italy | Emergency Department, Intensive

Care Units or Respiratory Unit |

RCT * | AECOPD * | HFNT * (60 L/min) | NIV * | PaCO 2, PaO 2, pH, intubation rate, mortality, dyspnoea score, comfort, hospital stay |

| Doshi et al. 34 2020 | 65 | United States of America | Emergency department | RCT * | AECOPD * | HFNT

*

(35 L/min) |

NIV * | PaCO 2, PaO 2, pH, dyspnoea score, intubation rate, hospital stay |

| Cong et al. 35 2019 | 168 | China | Intensive care unit | RCT * | AECOPD * | HFNT

*

(30 – 35 L/min) |

NIV * | PaCO 2, PaO 2, pH, comfort, hospital stay |

| Lee et al. 23 2018 | 88 | South Korea | Emergency department | Cohort | Acute-moderate hypercapnic respiratory failure | HFNT

*

(35 L/min) |

NIV * | PaCO 2, PaO 2, pH, intubation rate, mortality |

| Pilcher et al. 24 2017 | 24 | New Zealand | Emergency department | RCT * | AECOPD * | HFNT

*

(35 L/min) |

Standard nasal prong | PaCO 2, patient tolerability |

Abbreviations: ACOPD, Acute chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; COPD, Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; HFNT, High flow nasal therapy; n/N: Number of patients; NIV: Non-invasive ventilation; RCT, Randomized controlled trial.

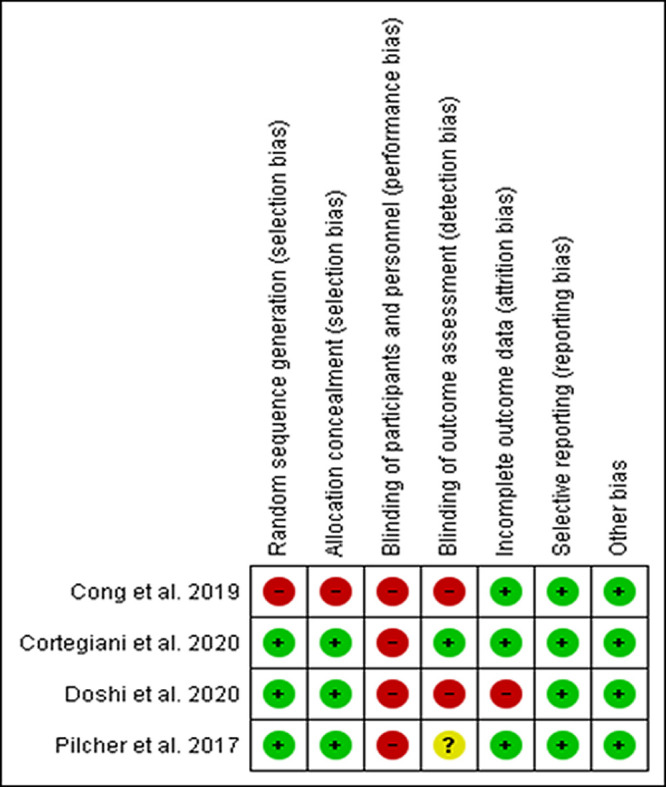

The risk of bias assessments for the four RCTs are described in Figure 2. 24, 34– 36 Blinding of participants and personnel were not possible in the trials. One trial showed a high risk for selection bias due to unexplained randomization sequence and allocation concealment. 35 The trials showed a high risk or unclear risk of detection bias due to no 34, 35 or unclear 24 blinding of the outcomes assessor. One trial showed a high risk of attrition bias due to unreported incomplete data. 34 The cohort study showed a low risk of bias in all domains and did not describe how the outcomes were assessed. 23

Figure 2. Risk of bias assessment.

Primary outcome (PaCO 2)

Changes in PaCO 2 after the intervention was reported in all five studies ( Table 5), 23, 24, 34– 36 four studies compared HFNT to NIV. 23, 34– 36 Doshi et al. 34 reported no significant difference in PaCO 2 at one hour between HFNT and NIV but there was a significant reduction in PaCO 2 at four hours (HFNT 6.7, 5.6 – 7.7 vs NIV 7.6, 6.3 – 9.3 (Median, interquartile range (IQR)). In the other studies comparing HFNT to NIV, 23, 35, 36 there was no significant difference in PaCO 2 at various time-points with a similar trend in PaCO 2 ( Figure 3). Pilcher et al. 24 compared HFNT with LFO at various five-minute time intervals with no significant difference, but when adjusted for the baseline PaCO 2, they reported a significant improvement in PaCO 2 by HFNT when compared to LFO.

Table 5. Trends in PaCO2 (kPa) at various time-points.

| Study | Time-points | HFNT * n/N * | HFNT

*

Mean (SD *) or Median (IQR *) |

n/N * | Mean (SD

*)

or Median (IQR *) |

Mean difference | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NIV * | LFO * | NIV * | LFO * | |||||

| Doshi et al. 34 2020 | Baseline | 34/34 | 56 (26 – 112) | 34/31 | - | 64.6 (38 – 137) | - | - |

| 1 hour | 34/33 | 56 (23 – 130) | 34/31 | - | 63 (31 – 122) | - | - | |

| 4 hour | 34/27 | 50 (31 – 74) | 34/25 | - | 57 (35 – 113) | |||

| Cortegiani et al. 36 2020 | Baseline | 80/40 | 9.8 (1.7) | 80/39 | - | 9.6 (1.7) | - | 0.20 [−0.55, 0.95] |

| 2 hours | 80/40 | 9.1 (2.1) | 80/39 | - | 8.4 (1.8) | - | 0.70 [−0.16, 1.56] | |

| 6 hours | 80/40 | 8.5 (2) | 80/39 | - | 7.7 (1.6) | - | 0.80 [0.00, 1.60] | |

| Cong et al. 35 2019 | Baseline | 168/84 | 9.6 (2.2) | 168/84 | - | 9.6 (2.3) | - | 0.00 [−0.68, 0.68] |

| 12 hours | 168/84 | 8.4 (2.1) | 168/84 | - | 8.4 (2.1) | - | 0.00 [−0.64, 0.64] | |

| 5 days | 168/84 | 7.8 (1.9) | 168/84 | - | 8 (1.9) | - | −0.20 [−0.77, 0.37] | |

| Lee et al. 23 2018 | Baseline | 88/44 | 7.50 (1.3) | 88/44 | - | 7 (1.2) | - | 0.50 [−0.02, 1.02] |

| 6 hours | 88/44 | 6.20 (2.2) | 88/44 | - | 6.90 (2.3) | - | −0.70 [−1.64, 0.24] | |

| 24 hours | 88/44 | 6.30 (2.1) | 88/44 | - | 6.6 (1.9) | - | −0.30 [−1.14, 0.54] | |

| Pilcher

et al.

24

2017 |

Baseline | 24/12 | 6.50 (1.3) | - | 24/12 | - | 6.50 (1.3) | 0.00 [−1.04, 1.04] |

| 5 minutes | 24/12 | 6.40 (1.3) | - | 24/12 | - | 6.50 (1.3) | −0.10 [−1.14, 0.94] | |

| 10 minutes | 24/12 | 6.30 (1.3) | - | 24/12 | - | 6.50 (1.3) | −0.20 [−1.24, 0.84] | |

| 15 minutes | 24/12 | 6.30 (1.3) | - | 24/12 | - | 6.50 (1.3) | −0.20 [−1.24, 0.84] | |

| 20 minutes | 24/12 | 6.35 (1.3) | - | 24/12 | - | 6.40 (1.3) | −0.05 [−1.09, 0.99] | |

| 25 minutes | 24/12 | 6.40 (1.3) | - | 24/12 | - | 6.40 (1.3) | 0.00 [−1.04, 1.04] | |

| 30 minutes | 24/12 | 6.30 (1.3) | - | 24/12 | - | 6.50 (1.3) | −0.20 [−1.24, 0.84] | |

Abbreviations: RCT, Randomized controlled trial; HFNT, High flow nasal therapy; NIV, Non-invasive ventilation; LFO, Low flow oxygen; n/N, Number of patients; SD, Standard deviation; min, minutes.

Figure 3. Forest plot of PaCO 2 at last available time-points from Cong et al. 35 and Cortegiani et al. 36 .

Secondary outcomes

pH level was reported in three studies. 23, 34, 35 Doshi et al. 34 reported no significant difference in pH between HFNT and NIV at one hour (HFNT 7.36, 7.34-7.42 vs NIV 7.31, 7.27-7.37, (Median, IQR)) or four hours (HFNT 7.38, 7.34-7.42 vs NIV 7.35, 7.33-7.37, (Median, IQR)). Cong et al. 35 reported no significant difference in pH between HFNT and NIV at 12 hours (MD -0.10, 95% CI -0.13, 0.06) or five days (MD -0.05, 95% CI -0.08, -0.01). Lee et al. 23 showed no significant difference in pH between HFNT and NIV at six hours (MD 0.02, 95% CI -0.16, 0.20) or 24 hours (MD 0.00, 95% CI -0.03, 0.03). The PaO 2 level was reported in four trials. 23, 34– 36 Doshi et al. 34 reported no significant difference in PaO 2 between HFNT and NIV at one hour (HFNT 13.2, 10.7-19.2 vs NIV 15.1, 8.8-22.9, (Median, IQR)) or four hours (HFNT 11.1, 5.3-13.2 vs NIV 11.7, 10.3-12.9, (Median, IQR)). Cong et al. 35 reported no significant difference in PaO 2 between HFNT and NIV at 12 hours (MD 0.00 kPa, 95% CI −0.70, 0.70) or five days (MD −0.10 kPa, 95% CI −0.72, 0.52). Lee et al. 23 reported no significant difference in PaO 2 between HFNT and NIV at six hours (MD 0.00 kPa, 95% CI −1.30, 1.30) or 24 hours (MD −0.10 kPa, 95% CI −1.28, 1.08).

Patient comfort was reported in three RCTs. 24, 35, 36 Patient comfort assessed using a self-designed survey in Cong et al. 35 a 10-point numerical rating scale in Cortegiani et al. 36 and the Likert scale in Pilcher et al. 24 showed that HFNT was more comfortable than LFO but louder than LFO ( Table 6).

Table 6. Comfort score using Likert scale * (RCT comparing HFNT vs SNP). 24 .

| Study | Time-points | Question | HFNT ‡ n/N ‡ | Mean (SD ‡) HFNT ‡ | SNP ‡ N/n ‡ | Mean (SD ‡) SNP ‡ | MD ‡ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pilcher et al. 24 2017 | 30 minutes | I found wearing the nasal interface:

1 = Very comfortable 5 = Very uncomfortable |

24/12 | 2.4 (1.3) | 24/12 | 2.4 (1.1) | 0.00 [−0.96, 0.96] |

| The nasal interface was:

1 = Light 5 = Heavy |

24/12 | 2.2 (1.2) | 24/12 | 1.9 (1.2) | 0.30 [−0.66, 1.26] | ||

| The intervention was:

1 = Quiet 5 = Noisy |

24/12 | 2.6 (1.4) | 24/12 | 1.3 (0.6) | 1.30 [0.44, 2.16] | ||

| My nasal passages were:

1 = Comfortable 5 = Dry |

24/12 | 1.9 (1.2) | 24/12 | 3.0 (1.7) | −1.10 [−2.28, 0.08] | ||

| Breathing through my nose was:

1 = Easy 5 = Very difficult |

24/12 | 2.3 (1.2) | 24/12 | 1.8 (1.0) | 0.50 [−0.38, 1.38] |

Answers to questions were made on a 1-5.

Abbreviations: RCT, Randomized controlled trial; HFNT, High flow nasal therapy; n/N, Number of patients; SD, Standard deviation; NIV, Non-invasive ventilation; MD, mean difference; SNP, Simple nasal prongs; MD, mean difference.

The intubation rate was reported in three studies comparing HFNT with NIV. 23, 34, 36 Doshi et al. 34 demonstrated no significant difference in intubation rate at 72 hours (RCT; OR 0.33 95% CI 0.06, 1.81). Cortegiani et al. 36 reported no significant difference in intubation rate at two hours (RCT; OR 0.32 95% CI 0.01, 8.02) or six hours (RCT; OR 0.97 95% CI 0.06, 16.14). Lee et al. 23 reported no significant difference at 30 days (cohort; OR 0.89 95% CI 0.34, 2.30) ( Table 7).

Table 7. Comfort score using 10-point numerical rating scale * (RCT comparing HFNT vs NIV). 36 .

| Study | Time-points | HFNT ‡ | NIV ‡ | P-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n/N ‡ | Median | IQR ‡ | n/N ‡ | Median | IQR ‡ | |||

| Cortegiani et al. 36 2020 | 2 hours | 80/40 | 1 | [0–2] | 80/39 | 3 | [1–5] | 0.0010 |

| 6 hours | 80/40 | 0 | [0–2] | 80/39 | 2 | [1–4] | 0.0003 | |

10-point numerical rating scale: where 0 is no discomfort and 10 is maximum discomfort

Abbreviations: HFNT, High flow nasal therapy; n/N, Number of patients; NIV, Non-invasive ventilation; IQR, Interquartile range.

The mortality rate was reported in two studies 23, 36 and there was no difference between HFNT and NIV groups ( Table 7).

The dyspnoea score, measured by Modified Borg score, a self-reported rating of perceived dyspnoea on a scale of one to 10, with 10 being the worst, was reported in two trials. 34, 36 The reduction in the dyspnoea score was similar between HFNT and NIV at different time points in both trials ( Table 8).

Table 8. Comfort score using self-designed survey* (comparing HFNT vs NIV). 35 .

| Study | Time-points | Treatment | n/N ‡ | Comfort N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cong et al. 35 2019 | 12 hours and 5 days | NIV ‡ | 168/84 | 57 (67.9) |

| HFNT ‡ | 168/84 | 75 (88.2) | ||

| P-value | 0.008 | |||

Self-designed survey: developed by the researchers to measure the comfort and satisfaction of patients in both groups.

Abbreviations: High flow nasal therapy; n/N, Number of patients; NIV, Non-invasive ventilation

Length of stay in hospital was reported by three trials 34– 36 comparing HFNT and NIV with no difference between the two groups ( Table 9).

Table 9. Mortality and intubation rate.

| Study | Outcome | Time-points | HFNT * n/N * | NIV * n/N * | OR * (95%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lee et al. 23 2018 | Mortality rate | 30-day | 44/7 | 44/8 | 0.85 [0.28, 2.59] |

| Cortegiani et al. 36 2020 | Mortality rate | In hospital mortality | 40/2 | 39/6 | 0.29 [0.05, 1.53] |

| Doshi et al. 34 2020 | Intubation rate | 72-hours | 34/2 | 31/5 | 0.33 [0.06, 1.81] |

| Cortegiani et al. 36 2020 | Intubation rate | 2 hours | 40/0 | 39/1 | 0.32 [0.01, 8.02] |

| 6 hours | 40/1 | 39/1 | 0.97 [0.06, 16.14] | ||

| Lee et al. 23 2018 | Intubation rate | 30-days | 44/11 | 44/12 | 0.89 [0.34, 2.30] |

Abbreviations: HFNT, High flow nasal therapy; n/N: Number of patients; NIV: Non-invasive ventilation; OR: Odd ratio

Table 10. Dyspnoea score using Modified Borg Score * (comparing HFNT vs NIV). 33, 36 .

| Study | Time points | HFNT ‡ | NIV ‡ | P-value/MD ‡ | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n/N ‡ | Median (IQR ‡) /Mean (SD ‡) | n/N ‡ | Median (IQR ‡)/Mean (SD ‡) | |||

| Doshi et al. 34 2020 | 30 minute | 65/33 | 4 (3-7) | 65/29 | 4 (2-6) | 451 |

| 1 hour | 65/31 | 3 (2-6) | 65/29 | 3 (1.5-5) | 0.595 | |

| 90 minute | 65/31 | 3 (2-5) | 65/29 | 2 (0-4.5) | 0.11 | |

| 4 hours | 65/28 | 2 (1-3.75) | 65/24 | 3 (1-4) | 0.788 | |

| Cortegiani et al. 36 2020 | 2 hours | 80/40 | 3 (2) | 80/39 | 3 (2) | 0.00 [−0.88, 0.88] |

| 6 hours | 80/40 | 5 (2) | 80/39 | 5 (2) | 0.00 [−0.88, 0.88] | |

Borg Modified Score: a self-reported rating of perceived dyspnoea on a scale of one to 10, with 10 being the worst.

Abbreviations: n/N, Number of patients; IQR, Interquartile range; HFNT, High flow nasal therapy; NIV, Non-invasive ventilation

Table 11. Length of stay.

| Study | HFNT * n/N * | Mean SD */Median IQR * | NIV * n/N * | Mean (SD *)/Median (IQR *) | MD * |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Doshi et al. 34 2020 | 65/34 | 105.1 hours (78.5-178.3) | 65/31 | 120.4 hours (67-144.5) | - |

| Cortegiani et al. 36 2020 | 80/40 | 10 days (9-19) | 80/39 | 13 days (9-16) | - |

| Cong et al. 35 2019 | 168/84 | 18.04 (6.15) | 168/84 | 18.31 (7.01) | −0.27 days |

Abbreviations: n/N, Number of patients; IQR, Interquartile range; HFNT, High flow nasal therapy; NIV, Non-invasive ventilation; MD, mean difference; SD, standard deviation

Discussion

Within the AT2RF patient population where HFNT is used as the initial management strategy, this systematic review has identified very few studies: four comparing HFNT with NIV and one comparing HFNT with LFO. HFNT, compared with NIV, showed a significant difference in PaCO 2 after four hours of treatment, 34 although the difference was not demonstrated at 24 hours, 23 five days, 35 six hours 36 and a similar lack of difference is seen when compared to LFO at 30 minutes. 24 The reduction in PaCO2 between the two groups at four hours demonstrated in Doshi et al. 34 is not adjusted for the baseline difference in PaCO 2 between the two groups. The absolute reduction of PaCO 2, when compared to the baseline, was 0.8 kPa for the HFNT group and 0.99 kPa in the NIV group, which suggest that the significant difference was secondary to baseline difference rather than true clinical superiority. Compared with NIV or LFO, HFNT showed no difference in pH and PaO 2 and has similar intubation rates, mortality and hospital length of stay. HFNT, when compared to NIV, is associated with better comfort as presented by Cong et al. 35 and Cortegiani et al., 36 although this was not replicated in Pilcher et al. 24 This systematic review found that despite the potential benefit of improved patient comfort and increasing use of HFNT in the treatment of AT2RF, the current evidence is quite poor. The certainty of the evidence was primarily impacted by the small number of trials and sample sizes, selection bias and few RCTs. Lack of blinding is a potential source of bias but the nature of the intervention precludes blinding, while the objective nature of the outcome measures reduces the risk of bias. Hence, objective outcome measures were not downgraded for lack of blinding while subjective measures such as comfort score and dyspnoea score were downgraded.

In AT2RF, the production of CO 2 is increased due to additional work of breathing, increased metabolism and failure to clear CO 2. NIV failure occurs in a quarter of these patients needing further IMV. The extent of reduction in pH, associated with the elevated CO 2, is significantly associated with NIV failure. 37 Any medical optimization introduced early after the detection of AT2RF should be aimed at improving CO 2 clearance and pH because the development of respiratory acidaemia post-admission is associated with a mortality of 33%. 3 While current evidence has convincingly established the benefits of NIV for AT2RF, evidence for newer and better-tolerated technologies to reduce hypercapnia is urgently required due to the high intolerance rate leading to a late failure. 10

In this systematic review focused on early intervention for AT2RF patients, there is no difference in various respiratory parameters between HFNT and NIV except for one study showing an improvement in PaCO 2 at a single time-point. HFNT is associated with a reduction in PaCO 2 and an increase in pH similar to NIV. While this could suggest that HFNT is non-inferior to NIV, HFNT cannot be recommended as an alternative management strategy to reduce PaCO 2 due to the low quality of evidence, lack of standardization of time-points for PaCO 2 measurement and the lack of adequately powered sample sizes. Similarly, in patients failing NIV due to compliance issues, HFNT may be a promising option to limit mechanical ventilation. This recommendation falls beyond the scope of this systematic review and is a clinical scenario that requires urgent attention. A similar response in CO 2 to HFNT is reported in COPD patients with stable type 2 respiratory failure, 38 post-acute NIV, 39 post NIV failure, 40– 42 post-extubation 43 and during breaks in NIV. 21

Studies have shown a reduction in intubation rate and mortality between NIV versus usual care 39 and a reduction in the length of hospital stay, lower incidence of complications with a longer-term benefit of fewer readmissions to hospital in the following year between NIV and IMV 44 with one study suggesting a mortality benefit. 45 HFNT, if equivalent to NIV, should ultimately reduce important outcomes such as intubation, mortality and health resource use. Three studies found no difference in intubation rate 23, 34, 36 and three studies found no difference in length of stay 34– 36 thus suggesting therapeutic equivalence but the studies were not powered for these outcomes. Doshi et al., 34 showed that HFNT when compared to NIV had a similar therapy failure rate of approximately 25%. Patients receiving HFNT had a trend towards a shorter ICU stay, likely driven by a lower intubation rate in the HFNT group (5.9%) when compared to the NIV group (16.1%), which did not achieve statistical significance in this study that was not powered for this outcome.

A key balancing outcome is an increase in adverse outcomes that have been highlighted in studies comparing NIV to usual care that include a delay in escalation to IMV, 46 increased mortality when compared to immediate IMV, and increased mortality when IMV is delayed. 47 In this systematic review, Lee et al. 23 and Cortegiani et al. 36 taken together with lower intubation rate in the HFNT arm, 34 suggests that HFNT is unlikely to be associated with harm through delayed initiation of IMV, but this hypothesis needs to be confirmed in a clinical trial.

One of the putative benefits of HFNT is patient comfort due to the lack of a tight-fitting mask, prevention of skin breakdown, better communication and mucous clearance. 24 HFNT, when compared to NIV, was shown to be associated with improved comfort in Cong et al. 35 and Cortegiani et al. 36 In this review, Doshi et al. 34 and Cortegiani et al. 36 did not detect any difference in dyspnoea between HFNT and NIV. The lack of demonstrable benefit is likely secondary to the earlier time points in the studies investigating the role of HFNT in the initial management of AT2RF.

HFNT is increasingly emerging as a therapeutic option for AT2RF, but various studies have combined it with other clinical scenarios such as post-extubation, 42 NIV interruption, 21 or physiological studies 24 and even in studies that explored its efficacy in acute exacerbations, the place of intervention could lead to bias, for example after initial management in the emergency medicine department, thus introducing unintentional bias such as lead-time bias as well selection bias. 35 The location of patients in a closely monitored environment, as opposed to a general ward, 47 might mask any adverse outcomes due to deterioration through earlier intervention. Hence, it is essential to investigate its utility in the early management of AT2RF in the emergency medicine department.

High flow nasal cannula can flush anatomical dead space, provide mild positive distending pressure, improve mucociliary clearance as well as be better tolerated. 48 Depending on the type of respiratory failure, type 1 or 2, a specific nasal cannula design that alters flow pattern could have a differential effect. A small-bore nasal cannula as seen in high flow nasal insufflation might purge the anatomical dead space more efficiently, thereby providing minimal ventilator assistance. 48, 49

The strength of the systematic review is that it was conducted to a high standard following recommended methods for the conduct, quality assessment and reporting, 50 using a comprehensive search strategy of all electronic databases. Despite this, the recommendations of the review are limited by the small number of trials, which highlights the need for further adequately powered trials.

We recommend that future research needs to address the following research gaps in the evidence base for the use of HFNT in AT2RF. Future trial designs should be randomized controlled trials, they should include sufficiently large patient numbers to ensure they are adequately powered for important clinical outcomes. Outcomes should be standardized with clear definitions including clinical outcomes, use validated scales and relevant time points. 51 The role of nasal cannula diameter in the efficiency of CO 2 clearance should be tested to determine whether the type of device used has an impact on therapy efficacy. 52 Studies should also encompass a robust health economic analysis, include outcome analysis of patients who fail therapy and identify any features to predict the outcome of the therapy to allow patient selection.

In conclusion, this review found very few studies investigating the clinical efficacy of HFNT in AT2RF. A similar reduction in PaCO 2 was seen between HFNT and NIV at various time-points, 35, 36 while a significantly higher PaCO 2 clearance with HFNT, when compared to NIV, was demonstrated at an early time point in one study. 34 Similarly, HFNT use was associated with better comfort in two studies, 35, 36 while a similar benefit was not shown in the other study. 24 The evidence is also moderate in quality and the benefit demonstrated is limited to clinically irrelevant time points, with no studies powered to detect clinical outcomes. Therefore, a change in practice cannot be recommended until further high-quality clinical trials are conducted.

Data availability

Underlying data

All data underlying the results are available as part of the article and no additional source data are required.

Extended data

Queen’s University Belfast institutional data repository (Pure system): High flow nasal therapy for acute type 2 respiratory failure: A systematic review. https://doi.org/10.17034/4080c4eb-38f0-4c02-91ee-37129ceb65a6. 30

This project contains the following extended data:

-

-

Search strategy for Medline for research article High flow nasal therapy for acute type two respiratory failure. A systematic review.pdf

Data are available under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC-BY 4.0).

Reporting guidelines

Queen’s University Belfast institutional data repository (Pure system): PRISMA checklist for “High flow nasal therapy for acute type 2 respiratory failure: A systematic review”. https://doi.org/10.17034/4080c4eb-38f0-4c02-91ee-37129ceb65a6. 30

Data are available under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC-BY 4.0).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge support from the Deanship of Scientific Research at King Saud University and Queen’s University Belfast librarian, Richard Fallis, for his support in developing the search strategy.

Funding Statement

The author(s) declared that no grants were involved in supporting this work.

[version 2; peer review: 2 approved]

References

- 1.Davidson A, Banham S, Elliott M, et al. : BTS/ICS guideline for the ventilatory management of acute hypercapnic respiratory failure in adults. Thorax. 2016;71:ii1–ii35. 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2015-208209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Plant PK, Owen JL, Elliott MW: One year period prevalence study of respiratory acidosis in acute exacerbations of COPD: implications for the provision of non-invasive ventilation and oxygen administration. Thorax. 2000;55:550–554. 10.1136/thorax.55.7.550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roberts CM, Stone RA, Buckingham RJ, et al. : National Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Resources and Outcomes Project implementation group. Acidosis, non-invasive ventilation and mortality in hospitalised COPD exacerbations. Thorax. 2011;66:43–48. 10.1136/thx.2010.153114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murphy R, Driscoll P, O'Driscoll R: Emergency oxygen therapy for the COPD patient. Emerg Med J. 2001;18:333–339. 10.1136/emj.18.5.333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Steer J, Gibson GJ, Bourke SC: Predicting outcomes following hospitalization for acute exacerbations of COPD. QJM. 2010;103:817–829. 10.1093/qjmed/hcq126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nicolini A, Ferrera L, Santo M, et al. : Noninvasive ventilation for hypercapnic exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: factors related to noninvasive ventilation failure. Pol Arch Med Wewn. 2014;124:525–531. 10.20452/pamw.2460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Contou D, Fragnoli C, Córdoba-Izquierdo A, et al. : Noninvasive ventilation for acute hypercapnic respiratory failure: intubation rate in an experienced unit. Respir Care. 2013 Dec;58:2045–2052. 10.4187/respcare.02456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Confalonieri M, Garuti G, Cattaruzza MS, et al. : Italian noninvasive positive pressure ventilation (NPPV) study group. A chart of failure risk for noninvasive ventilation in patients with COPD exacerbation. Eur Respir J. 2005 Feb;25:348–355. 10.1183/09031936.05.00085304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Phua J, Kong K, Lee KH, et al. : Noninvasive ventilation in hypercapnic acute respiratory failure due to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease vs. other conditions: effectiveness and predictors of failure. Intensive Care Med. 2005;31:533–539. 10.1007/s00134-005-2582-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Squadrone E, Frigerio P, Fogliati C, et al. : Noninvasive vs invasive ventilation in COPD patients with severe acute respiratory failure deemed to require ventilatory assistance. Intensive Care Med. 2004;30:1303–1310. 10.1007/s00134-004-2320-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ngandu H, Gale N, Hopkinson JB: Experiences of noninvasive ventilation in adults with hypercapnic respiratory failure: a review of evidence. Eur Respir Rev. 2016;25:451–471. 10.1183/16000617.0002-2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Möller W, Feng S, Domanski U, et al. : Nasal high flow reduces dead space. J Appl Physiol. 2017;122:191–197. 10.1152/japplphysiol.00584.2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Parke RL, McGuinness SP: Pressures delivered by nasal high flow oxygen during all phases of the respiratory cycle. Respir Care. 2013;58:1621–1624. 10.4187/respcare.02358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Spoletini G, Alotaibi M, Blasi F, et al. : Heated Humidified High-Flow Nasal Oxygen in Adults: Mechanisms of Action and Clinical Implications. Chest. 2015;148:253–261. 10.1378/chest.14-2871 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ashraf-Kashani N, Kumar R: High-flow nasal oxygen therapy. BJA Education. 2017;17:57–62. 10.1093/bjaed/mkw041 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim ES, Lee H, Kim SJ, et al. : Effectiveness of high-flow nasal cannula oxygen therapy for acute respiratory failure with hypercapnia. J Thorac Dis. 2018;10:882–888. 10.21037/jtd.2018.01.125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sklar MC, Mohammed A, Orchanian-Cheff A, et al. : The impact of high-flow nasal oxygen in the immunocompromised critically ill: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Respir Care. 2018;63:1555–1566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Espiney R, Jablonski J, Brys M, et al. : Humidified High Flow Nasal Cannula Algorithm for Primary Therapy in Hypercapnic Respiratory Failure. Glob J Anes & Pain Med. 2019;1:86–91. 10.32474/GJAPM.2019.01.000120 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bräunlich J, Wirtz H: Nasal high-flow in acute hypercapnic exacerbation of COPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2018;13:3895–3897. 10.1183/13993003.congress-2019.PA4035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yuste ME, Moreno O, Narbona S, et al. : Efficacy and safety of high-flow nasal cannula oxygen therapy in moderate acute hypercapnic respiratory failure. Rev Bras Ter Intensiva. 2019;31:156–163. 10.5935/0103-507X.20190026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Longhini F, Pisani L, Lungu R, et al. : High-Flow Oxygen Therapy After Noninvasive Ventilation Interruption in Patients Recovering From Hypercapnic Acute Respiratory Failure: A Physiological Crossover Trial. Crit Care Med. 2019;47:e506–e511. 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Doshi P, Whittle JS, Bublewicz M, et al. : High-Velocity Nasal Insufflation in the Treatment of Respiratory Failure: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Ann Emerg Med. 2018;72:73–83.e5. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2017.12.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee MK, Choi J, Park B, et al. : High flow nasal cannulae oxygen therapy in acute-moderate hypercapnic respiratory failure. Clin Respir J. 2018;12:2046–2056. 10.1111/crj.12772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pilcher J, Eastlake L, Richards M, et al. : Physiological effects of titrated oxygen via nasal high-flow cannulae in COPD exacerbations: A randomized controlled cross-over trial. Respirology. 2017;22:1149–1155. 10.1111/resp.13050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Papachatzakis Y, Nikolaidis PT, Kontogiannis S, et al. : High-Flow Oxygen through Nasal Cannula vs. Non-Invasive Ventilation in Hypercapnic Respiratory Failure: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:5994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li Z, Wang T, Yang Y, et al. : Efficacy of non-invasive ventilation and oxygen therapy on immunocompromised patients with acute hypoxaemic respiratory failure: protocol for a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e015335. 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-015335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhao H, Wang H, Sun F, et al. : High-flow nasal cannula oxygen therapy is superior to conventional oxygen therapy but not to noninvasive mechanical ventilation on intubation rate: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care. 2017;21:184. 10.1186/s13054-017-1760-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pisani L, Astuto M, Prediletto I, et al. : High flow through nasal cannula in exacerbated COPD patients: a systematic review. Pulmonology. 2019;25:348–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. : The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. 10.1136/bmj.n71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alnajada A, Blackwood B, Mobrad A, et al. : High flow nasal therapy for acute type 2 respiratory failure: a systematic review. 2021. 10.17034/4080c4eb-38f0-4c02-91ee-37129ceb65a6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, et al. : The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d5928. 10.1136/bmj.d5928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wells G, Shea B, O'Connell D, et al. : The Ottawa Hospital. [cited 2019 Aug 21]. Reference Source

- 33.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, et al. : GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2008;336:924–926. 10.1136/bmj.39489.470347.AD [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Doshi PB, Whittle JS, Dungan G, 2nd, et al. : The ventilatory effect of high velocity nasal insufflation compared to non-invasive positive-pressure ventilation in the treatment of hypercapneic respiratory failure: A subgroup analysis. Heart Lung. 2020;49:610–615. 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2020.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cong L, Zhou L, Liu H, et al. : Outcomes of high-flow nasal cannula versus non-invasive positive pressure ventilation for patients with acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2019;12:10863–10867. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cortegiani A, Longhini F, Madotto F, et al. : AECOPD study investigators. High flow nasal therapy versus noninvasive ventilation as initial ventilatory strategy in COPD exacerbation: a multicenter non-inferiority randomized trial. Crit Care. 2020;24:692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Price LC, Lowe D, Hosker HS, et al. : UK National COPD Audit 2003: Impact of hospital resources and organisation of care on patient outcome following admission for acute COPD exacerbation. Thorax. 2006;61:837–842. 10.1136/thx.2005.049940 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bräunlich J, Beyer D, Mai D, et al. : Effects of nasal high flow on ventilation in volunteers, COPD and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis patients. Respiration. 2013;85:319–325. 10.1159/000342027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pisani L, Betti S, Biglia C, et al. : Effects of high-flow nasal cannula in patients with persistent hypercapnia after an acute COPD exacerbation: a prospective pilot study. BMC Pulm Med. 2020;20:1–9. 10.1186/s12890-020-1048-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Plotnikow G, Thille AW, Vasquez D, et al. : High-flow nasal cannula oxygen for reverting severe acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A case report. Med Intensiva. 2017;41:571–572. 10.1016/j.medin.2016.11.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pavlov I, Plamondon P, Delisle S: Nasal high-flow therapy for type II respiratory failure in COPD: A report of four cases. Respir Med Case Rep. 2017;20:87–88. 10.1016/j.rmcr.2016.12.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lepere V, Messika J, La Combe B, et al. : High-flow nasal cannula oxygen supply as treatment in hypercapnic respiratory failure. Am J Emerg Med. 2016;34:1914.e1–1914.e19142.39. 10.1016/j.ajem.2016.02.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jing G, Li J, Hao D, et al. : Comparison of high flow nasal cannula with noninvasive ventilation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients with hypercapnia in preventing postextubation respiratory failure: A pilot randomized controlled trial. Res Nurs Health. 2019;42:217–225. 10.1002/nur.21942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Osadnik CR, Tee VS, Carson-Chahhoud KV, et al. : Non-invasive ventilation for the management of acute hypercapnic respiratory failure due to exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;7:CD004104. 10.1002/14651858.CD004104.pub4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Conti G, Antonelli M, Navalesi P, et al. : Noninvasive vs. conventional mechanical ventilation in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease after failure of medical treatment in the ward: a randomized trial. Intensive Care Med. 2002;28:1701–1707. 10.1007/s00134-002-1478-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Confalonieri M, Parigi P, Scartabellati A, et al. : Noninvasive mechanical ventilation improves the immediate and long-term outcome of COPD patients with acute respiratory failure. Eur Respir J. 1996;9:422–430. 10.1183/09031936.96.09030422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wood KA, Lewis L, Von Harz B, et al. : The use of noninvasive positive pressure ventilation in the emergency department: results of a randomized clinical trial. Chest. 1998;113:1339–1346. 10.1378/chest.113.5.1339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chandra D, Stamm JA, Taylor B, et al. : Outcomes of noninvasive ventilation for acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in the United States, 1998-2008. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185:152–159. 10.1164/rccm.201106-1094OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Spicuzza L, Schisano M: High-flow nasal cannula oxygen therapy as an emerging option for respiratory failure: the present and the future. Ther Adv Chronic Dis. 2020;11:2040622320920106. 10.1177/2040622320920106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Campbell M, McKenzie JE, Sowden A, et al. : Synthesis without meta-analysis (SWiM) in systematic reviews: reporting guideline. BMJ. 2020;368:l6890. 10.1136/bmj.l6890 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Alexander G, Mathioudakis AG, Moberg M, et al. : Outcomes reported on the management of COPD exacerbations: a systematic survey of randomised controlled trials. ERJ Open Res. 2019;5:00072–02019. 10.1183/23120541.00072-2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bräunlich J, Mauersberger F, Wirtz H: Effectiveness of nasal highflow in hypercapnic COPD patients is flow and leakage dependent. BMC Pulm Med. 2018;18:1–6. 10.1186/s12890-018-0576-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]