Abstract

The Split-Cre system is a powerful tool for genetic manipulation and can be used to spatiotemporally control gene expression in vivo. However, the low activity of the reconstituted NCre/CCre recombinase in the Split-Cre system limits its application as an indicator of the simultaneous expression of a pair of genes of interest. Here, we describe two approaches for improving the activity of the Split-Cre system after Cre reconstitution based on self-associating split GFP (Split-GFP) and SpyTag/SpyCatcher conjugation. First, we created the Split-GFP-Cre system by constructing fusion proteins of NCre and CCre with the N-terminal and C-terminal subunits of GFP, respectively. Reconstitution of Cre by GFP-mediated dimerization of the two fusion proteins resulted in recombinase activity approaching that of full-length Cre in living cells. Second, to further increase recombinase activity at low levels of Split-Cre expression, the Split-Spy-GCre system was established by incorporating the sequences for SpyTag and SpyCatcher into the components of the Split-GFP-Cre system. As anticipated, covalent conjugation of the SpyTag and SpyCatcher segments improved Split-GFP dimerization to further increase Cre recombinase activity in living cells. The increased efficiency and robustness of this dual-split system (Split-Cre and Split-GFP) minimize the problems of incomplete double gene-specific KO or low labeling efficiency due to poor NCre/CCre recombinase activity. Thus, this Split-Spy-GCre system allows more precise gene manipulation of cell subpopulations, which will provide advanced analysis of genes and cell functions in complex tissue such as the immune system.

Keywords: Split-Cre, Split-GFP, SpyTag/SpyCatcher, Split-Spy-GCre

Abbreviations: HEK 293T, human embryonic kidney cancer cells 293T; NLS, nuclear localization signal

The Cre-loxP recombinase system, which catalyzes homologous DNA recombination between two pairs of 34-bp sequences called loxP sites, is widely used to edit animal genomes to conditionally activate or knock out specific genes (1, 2). Genetic lineage tracing technology based on the Cre-loxP system is a powerful tool for studying the plasticity of cell fate during development, immunity, and regeneration (3) but has technical limitations. In particular, the accuracy of this technology mainly depends on the specificity of Cre expression. Ectopic expression of a small amount of Cre in nontargeted cells or transient expression in stem cells at an early stage of development may lead to accidental lineage tracking and confusing interpretation of fate-mapping data. This limitation has been a major source of scientific controversy in recent years.

Two or more genes are often required to accurately define a certain type of cell; consequently, Cre transgenic models driven by a single promoter often show limited specificity for their intended target cells. The Cre enzyme can be split into two inactive polypeptide chains (NCre and CCre, respectively), which spontaneously reassociate with each other to produce an active recombinase under the control of different promoters (4). Expression of both NCre and CCre in the same cell type allows for recombination of loxp-flanked DNA sequences. The Split-Cre system or a combination of multiple recombinases can be used to knock out two genes simultaneously or mark a particular subset of cells (5, 6, 7). In the Split-Cre system, two specific gene promoters are used to activate NCre and CCre expression; Cre recombinase activity is obtained only when the two specific genes/promoters are simultaneously expressed in the same cell (8). The activity of Split-Cre recombinase can be further improved by fusing NCre and CCre to complementary fragments whose dimerization is induced by a ligand. The efficiency of DNA recombination is closely related to the activity of the reconstituted Cre, which in turn depends strictly on the affinity and stability of the dimer molecule bringing NCre and CCre together. A far-red light-induced Split-Cre system based on a bacteriophytochrome optogenetic system was recently reported for controllable genome engineering in mice (9).

Various efforts have sought to evaluate and improve the reconstitution and activity of Cre polypeptides. Among the earliest works, Jullien et al. (10) reconstituted the Cre pairs aa 19 to 59/aa 60 to 343 and aa 19 to 104/106 to 343. In a transient assay, the aa 19 to 104/106 to 343 pair showed higher recombination activity, whereas the aa 19 to 59/aa 60 to 343 pair was more efficient in a stable excision assay. Hirrlinger et al. (7) fused the coiled-coil domain of the yeast transcriptional activator GCN4 with the Split-Cre pair aa 19 to 59/aa 60 to 343 to promote NCre–CCre dimer formation in transgenic mice and found 26% deletion efficiency. In 2012, Wang et al. (11) used split inteins from the protein DnaE of the cyanobacterium Synechocystis to reassemble Cre peptides aa 19 to 59 and aa 60 to 343 and observed high Cre activity in mouse brain tissue. Wen et al. (12) reconstructed Cre from the pair aa 1 to 59/aa 60 to 343 with and without the SV40 nuclear localization signal (NLS) and achieved up to 67% WT Cre efficiency in an excision assay of Agrobacterium rhizogenes-mediated transformation of tobacco root hair.

Although these Split-Cre systems can be used to spatiotemporally control gene expression in vivo, their applicability is limited by the low efficiency of Cre reconstitution and subsequent recombinase activity. In this article, we improved the activity of the Split-Cre system in two stages. First, self-associating split GFP (Split-GFP) was fused with NCre and CCre for complementation and reconstitution. Split-GFP is a powerful tool for evaluating self-association; the appearance of a fluorescent signal indicates that two genes are being expressed at the same time in live cells or animals. The high efficiency and stability of Split-GFP reassembly at physiological temperature make this reporter system ideal for identifying and studying interactions between proteins and/or peptides in vivo (13, 14, 15). Second, SpyTag/SpyCatcher was introduced into the Split-GFP-Cre system to further improve the NCre–CCre interaction. SpyTag/SpyCatcher is a peptide–protein pair that spontaneously reconstitutes to form a covalent bond under a range of temperatures (4–37 °C), pH values (5, 6, 7, 8) and buffers (no specific anion or cation required) (16). We found that covalent binding of the SpyTag and SpyCatcher pair from the Streptococcus pyogenes fibronectin-binding protein FbaB selectively increased GFP fluorescence intensity and improved Cre recombinase activity in living cells. This innovative and efficient Split-Spy-GCre system has important application potential in biological research.

Results

Reconstitution of Cre activity in Split-Cre pairs by the Split-GFP

To improve the Split-Cre system, we first analyzed the sequence and structure of Cre recombinase. Studies have shown that the 17 amino acids (aa 2–18) at the N terminus of Cre are not related to the enzyme’s recombinase activity (17). We measured the recombinase activity of Cre missing these 17 aa (ΔN17Creaa 19–343) and confirmed that it was comparable to that of full-length Cre (Fig. S1, A and B). Consequently, ΔN17Creaa 19–343 was used as the template for further construct generation. Relatively few break points allow Cre fragment complementation; several pairs split after aa 59, which is located between the loops of α-helices B and C, and a single pair split at aa 104 to 106 has been reported. Taking all factors into consideration, we chose aa 59 and aa 104 as break points for evaluation.

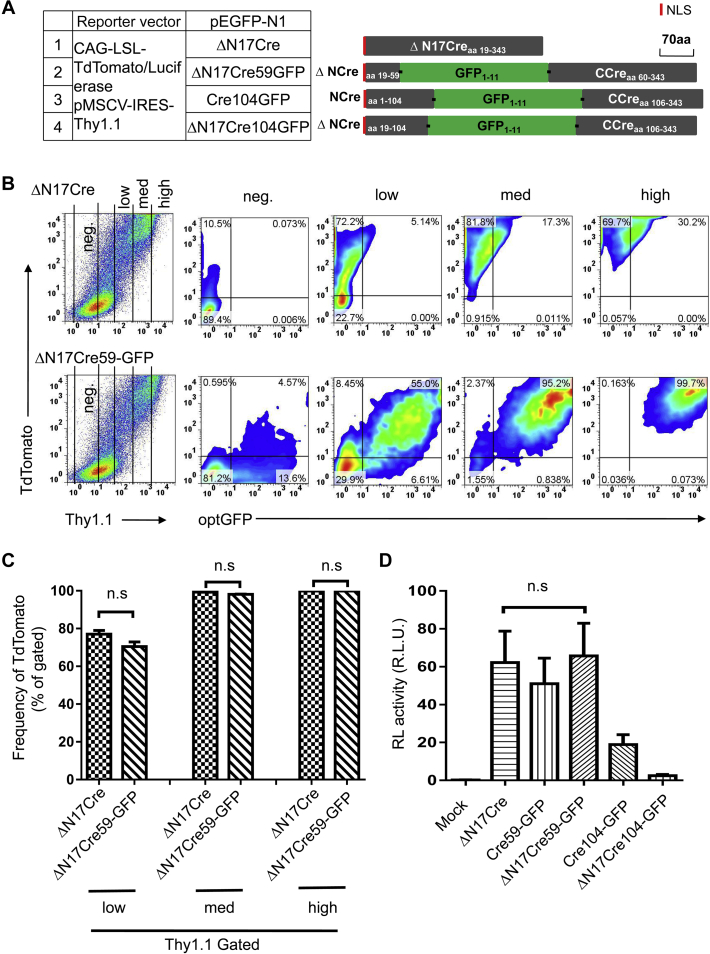

The complete GFP sequence was inserted into Cre at both selected break points, aa 59 and aa 104, to generate the fully connected GFP-Cre (Fig. 1A). To compare Cre activity, both the full-length and 17-aa deletion sequences of Cre were used to generate GFP-Cre constructs (Fig. 1, B and D). Human embryonic kidney cancer cells 293T (HEK 293T) cells were cotransfected with one of the GFP-Cre constructs, the Cre activity detection vector CAG-loxp-STOP-loxp-TdTomato (Fig. S2), and pMSCV-Thy1.1. pMSCV-Thy1.1 was used to facilitate the use of flow cytometry to detect gene transfection efficiency and target gene expression in cells, as the expression of Thy1.1 on the cell surface can be used to indicate intracellular expression of transfected genes. GFP-Cre expression levels were classified as high, middle, and low according to the level of Thy1.1 expression, and the proportion of TdTomato-positive cells was calculated. Flow cytometry analysis showed that the Cre recombinase activity of fully connected GFP-Cre in which GFP was inserted at aa 59 (ΔN17Cre59-GFP) was equivalent to that of full-length Cre (ΔN17Cre) (Fig. 1, B and C). As further confirmation, we used CAG-loxp-STOP-loxp-Luciferase as the Cre activity detection vector (Fig. S2). The dual-luciferase reporter system showed the same results as flow cytometry (Fig. 1D). By contrast, aa 104 was not an ideal break point. The recombinase activity of Cre104-GFP, especially ΔN17Cre104-GFP, was extremely low (Fig. 1D).

Figure 1.

Quantitative analysis of the recombinase activity of the different Cre-GFP fusion proteins.A, schematic representation of the Cre-GFP fusion protein constructs. The translation initiation codon was inserted in the Kozak consensus sequence. NLS indicates the nuclear localization signal peptide. The Cre-GFP genes were cloned into the pEGFP-N1 vector after deleting the EGFP gene. HEK 293T cells were cotransfected with one of the GFP-Cre constructs, the Cre activity detection vector CAG-loxp-STOP-loxp-TdTomato (or CAG-loxp-STOP-loxp-TdTomato), and pMSCV-IRES-Thy1.1. B, analysis of recombinase activity by transient transfection. HEK 293T cells were transiently transfected with a Cre-GFP fusion construct and cotransfected with CAG-loxp-STOP-loxp-TdTomato and pMSCV-Thy1.1 as reporters to visualize Cre reconstitution and transfection efficiency, respectively. The cells were harvested 20 h after transfection, and cells with different Cre expression levels as indicated by the Thy1.1 expression level were analyzed by flow cytometry. C, the average frequencies of TdTomato+ cells among cells with different Cre expression levels (Thy1.1 low, medium, and high) in panel B are shown. D, analysis of recombinase activity by transient transfection. HEK 293T cells were transiently transfected with a Cre-GFP fusion construct and CAG-loxp-STOP-loxp-Luciferase. The activities of Cre were determined 20 h after transfection. The data shown are typical results from three experiments. The small horizontal bars indicate the mean ± SEM. HEK 293T, human embryonic kidney cancer cells 293T; ns, not significant; R.L.U., relative luciferase units.

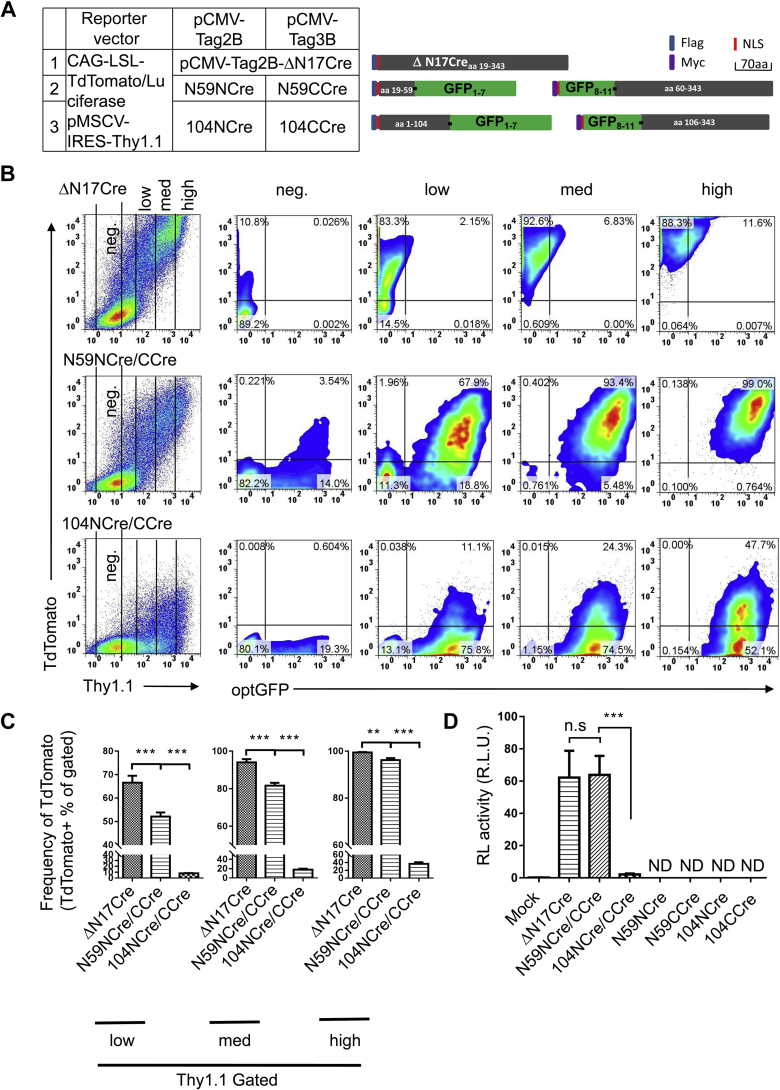

Next, we joined NCre with N-terminal GFP and C-terminal GFP with CCre through a GGGGS linker to generate the following Split-Cre constructs: N59NCre (NCreaa 19–59-NGFP1–7), 104NCre (NCreaa 1–104-NGFP1–7), N59CCre (CGFP8–11-CCreaa 60–343), and 104CCre (CGFP8–11-CCreaa 106–343). Because the Cre enzyme needs to enter the nucleus for genomic cleavage and only NCre retains the original NLS sequence of Cre, we added an additional NLS to the N terminus of the CCre construct. A flag tag was added in front of the NLS in N59NCre and 104NCre, and an myc tag was added in front of the NLS in N59CCre and 104CCre (Fig. 2A). Then, HEK 293T cells were cotransfected with a matching Split-Cre pair, the CAG-loxp-STOP-loxp-TdTomato Cre activity detection vector, and pMSCV-Thy1.1. The expression of Cre was classified as high, middle, and low depending on the level of Thy1.1 expression, and the proportion of TdTomato-positive cells was determined. The results showed that aa 59 was an ideal break point for our GFP-Cre system. The recombinase activity of Split-Cre using this break point reached approximately 60% to 95% of full-length Cre activity (Fig. 2, B and C). We named this system Split-GFP-Cre. To further verify the flow cytometry results, we used CAG-loxp-STOP-loxp-Luciferase as the Cre activity detection vector. The dual-luciferase reporter system showed that the recombinase activity of Split-GFP-Cre was similar to that of full-length Cre (Fig. 2D).

Figure 2.

Reconstitution of Cre activity in Split-Cre pairs by the Split-GFP.A, schematic representation of the Split-GFP-Cre fusion proteins in this study. The amino acid numbers shown in the blue bars correspond to the Cre protein. N59NCre and 104NCre correspond to the N-terminal half of Cre, and N59CCre and 104CCre correspond to the C-terminal half of Cre. GFP1–7 and GFP8–11 designate fragments of GFP corresponding to β-sheets 1 to 7 and 8 to 11, respectively. The positions of immunotags (flag, myc) and the nuclear localization sequence (NLS) are also shown. B, comparison of the level of Cre recombinase activity after transient transfection of the different Split-GFP-Cre constructs. The plasmids CAG-loxp-STOP-loxp-TdTomato and pMSCV-Thy1.1 were cotransfected as reporters to visualize Cre recombinase activity and transfection efficiency, respectively. The cells were harvested 20 h after transfection, and cells with different Cre expression levels as indicated by the Thy1.1 expression level were analyzed by flow cytometry. C, the average frequencies of TdTomato+ cells among cells expressing different levels of Cre (Thy1.1 low, medium, and high) in panel B are shown. D, analysis of recombinase activity by transient transfection. HEK 293T cells were transiently cotransfected with a Split-GFP-Cre construct and CAG-loxp-STOP-loxp-Luciferase. The activities of Cre were determined 20 h after transfection. The data shown are typical results from three experiments. The small horizontal bars indicate the mean ± SEM. ∗∗p < 0.01 and ∗∗∗p < 0.001 (ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test). HEK 293T, human embryonic kidney cancer cells 293T; ND, none detected; ns, not significant; R.L.U., relative luciferase units.

Comparative analysis of the Cre activity of different Split-Cre reconstitution systems

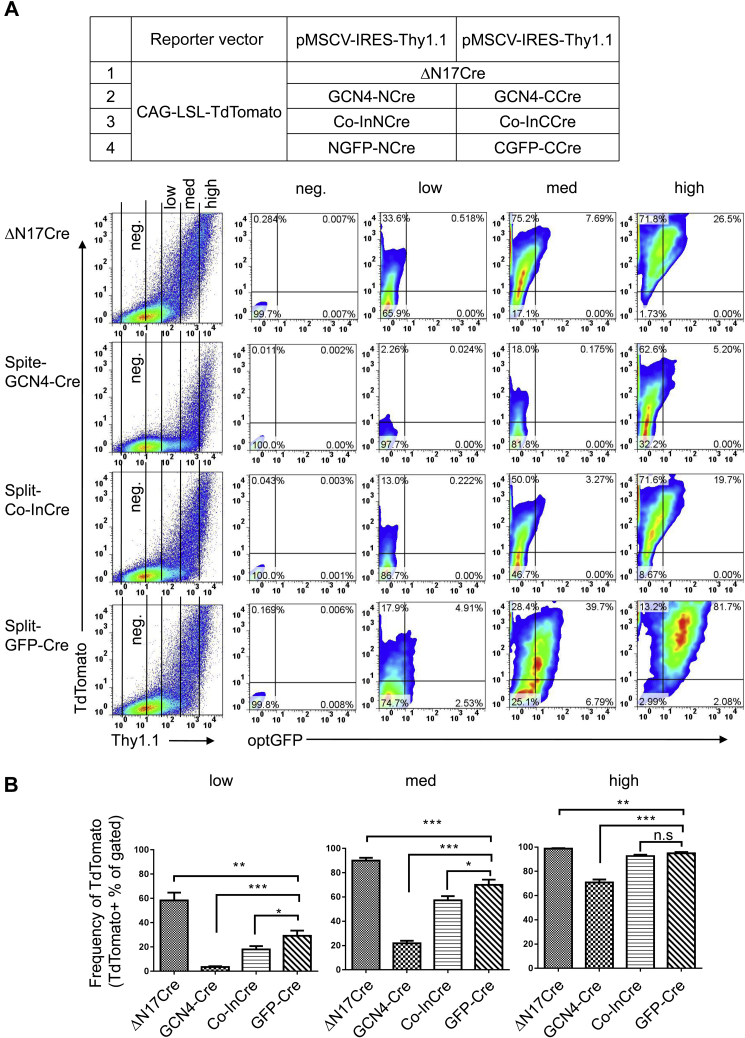

Previously reported Split-Cre systems using aa 59 as the break point include Split-GCN4-Cre and Split-Co-InCre. The Split-GCN4-Cre system uses a leucine zipper–based dimerization strategy, and efficient dimerization likely requires medium to high expression levels of each half of Cre. In contrast to reconstituting activity from protein fragment complementation, the Split-Co-InCre system effectively reconstructs the full Cre protein by splicing together the separate protein peptides.

To compare the activity of our Split-GFP-Cre system with these two systems, the components of each system were subcloned into the pMSCV-IRES-Thy1.1 expression vector. The expression level of Split-Cre was divided into high, middle, and low according to the strength of Thy1.1 expression, and the proportion of TdTomato-positive cells was calculated. Compared with the Split-GCN4-Cre and Split-Co-InCre systems, the Split-GFP-Cre system had higher recombinase activity under the same expression level (Fig. 3, A and B). In addition, GFP fluorescence of the Split-GFP-Cre heterodimer was successfully detected (Fig. 3A). The detection of GFP fluorescence indicates that the components with two different promoters were expressed simultaneously, which will allow the use of this system with the Rosa26 reporter in future fate-mapping studies in vivo.

Figure 3.

Comparative analysis of Cre activity in different Split-Cre reconstitution systems.A, comparison of Cre recombinase activity levels after the transient transfection of different pairs of complementary Cre fragments. ΔN17Cre and the components of Split-GCN4-Cre, Split-Co-InCre, and Split-GFP-Cre were each inserted into the pMSCV-Thy1.1 expression reporter vector and used to transfect HEK 293T cells with the CAG-loxp-STOP-loxp-TdTomato Cre activity detection vector. The cells were harvested 20 h after transfection, and TdTomato+ cells were detected. B, the average frequencies of TdTomato+ cells among cells with different Cre expression levels (Thy1.1 low, medium, and high) in panel A are shown. The data shown are typical results from three experiments. The small horizontal bars indicate the mean ± SEM. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, and ∗∗∗p < 0.001 (ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test). HEK 293T, human embryonic kidney cancer cells 293T; ns, not significant.

SpyTag/SpyCatcher-assisted complementation of Split-GFP-Cre

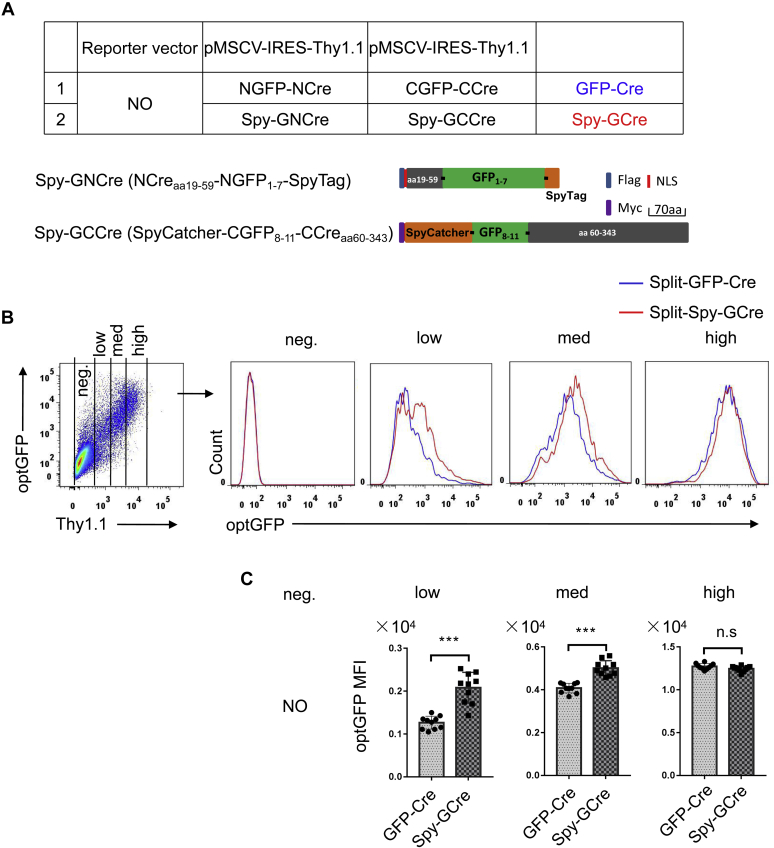

Although the formation of a dimer by Split-GFP increased Cre recombinase activity in the Split-GFP-Cre system to a certain extent, the recombinase activity was not ideal under low levels of Cre expression. SpyTag/SpyCatcher conjugation technology produces spontaneous and rapid covalent ligation that does not affect the original catalytic activity and function of the target protein and has strong stability. Therefore, in an attempt to improve upon the Split-GFP-Cre system, we created the Split-Spy-GCre system, which links NGFP1–7 and CGFP8–11 through SpyTag/SpyCatcher conjugation technology to improve the recombinase activity after Split-GFP-Cre dimerization.

To build the Split-Spy-GCre system, we constructed Spy-GNCreaa 59 (NCreaa 19–59-NGFP1–7-SpyTag) and Spy-GCCreaa 60 (SpyCatcher-CGFP8–11-CCreaa 60–343) (Fig. 4A). We first assessed the ability of SpyTag/SpyCatcher conjugation technology to enhance the fluorescence intensity of Split-GFP. The expression of the reporter gene Thy1.1 was used to correlate the intensity of GFP fluorescence with different expression levels. The conjugation technology significantly increased the fluorescent signal of GFP, indicating enhanced reconstitution of GFP (Fig. 4, B and C). To evaluate the subsequent effects on Split-Cre recombinase activity, we cotransfected the Split-Spy-GCre system and CAG-loxp-STOP-loxp-TdTomato Cre activity detection reporter into HEK 293T cells. Analysis of TdTomato-positive cells at different Cre expression levels showed that, compared with the Split-GFP-Cre system, the Split-Spy-GCre-system significantly increased the activity of Split-Cre recombinase. Moreover, the recombinase activity of Split-Cre in the Split-Spy-GCre system was comparable with that of intact Cre at all expression levels (Fig. 5, A and B).

Figure 4.

SpyTag/SpyCatcher can improve the stability of Split-GFP.A, schematic representation of the Spy-GNCreaa 59 (NCreaa 19–59-NGFP1–7-SpyTag) and Spy-GCCreaa 60 (SpyCatcher-CGFP8–11-CCreaa 60–343) fusion proteins in this study. All constructs were inserted into the pMSCV-Thy1.1 expression reporter vector. B, HEK 293T cells were transiently transfected with components of the Split-GFP-Cre or Split-Spy-GCre system. The cells were harvested 20 h after transfection, and cells with different Cre expression levels as indicated by the Thy1.1 expression level were analyzed by flow cytometry. C, the fluorescence intensity of GFP among cells expressing different levels of Cre (Thy1.1 low, medium, and high) is shown. HEK 293T, human embryonic kidney cancer cells 293T; ns, not significant. ∗∗∗p < 0.001 (ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test).

Figure 5.

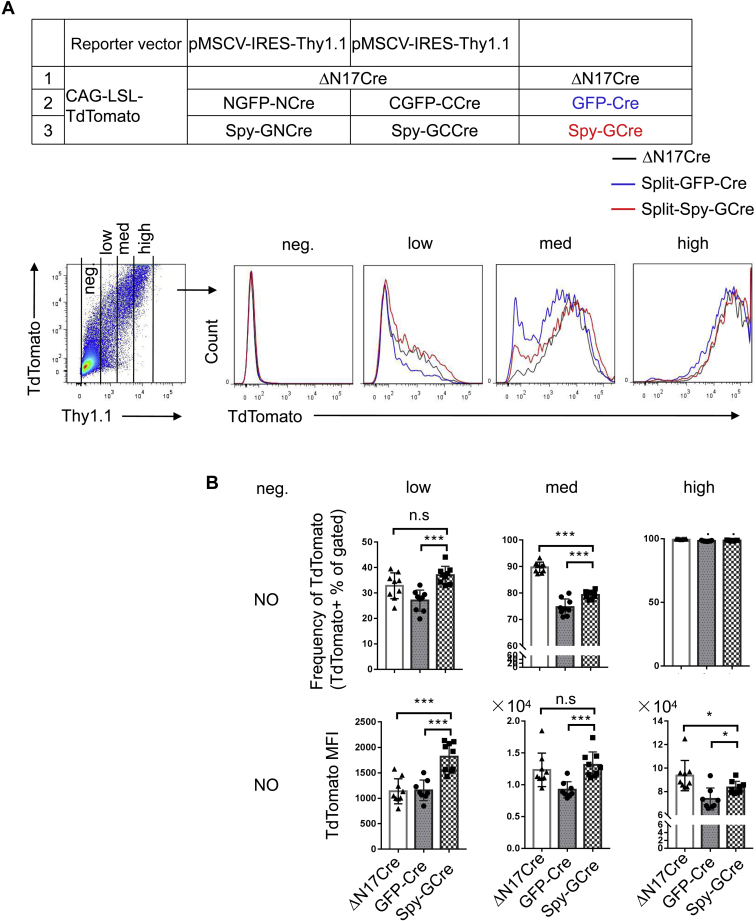

SpyTag/SpyCatcher-assisted reconstitution of Split-GFP-Cre.A, comparison of the level of Cre recombination after transient transfection of different complementary pairs of Cre fragments. HEK 293T cells were transiently transfected with plasmids encoding ΔN17Cre or the components of the Split-GFP-Cre or Split-Spy-GCre system. All genes were first inserted into pMSCV-Thy1.1 expression reporter vector. The cells were cotransfected with the CAG-loxp-STOP-loxp-TdTomato reporter vector to visualize Cre reconstitution efficiency. The cells were harvested 20 h after transfection, and cells with different Cre expression levels as indicated by the Thy1.1 expression level were analyzed by flow cytometry. B, the fluorescence intensity of TdTomato and average frequencies of TdTomato+ cells among cells expressing different Cre levels (Thy1.1 low, medium, and high) are shown. The data shown are typical results from two experiments. The small horizontal bars indicate the mean ± SEM. ∗p < 0.05 and ∗∗∗p < 0.001 (Student’s t test and ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test). HEK 293T, human embryonic kidney cancer cells 293T; ns, not significant.

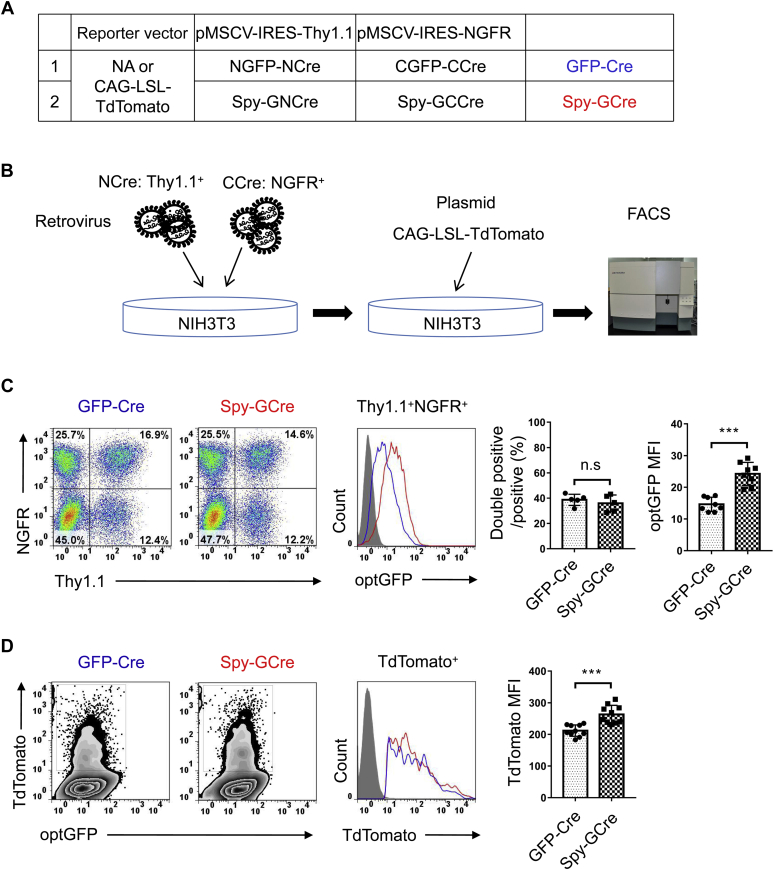

A major rationale for building the Split-Spy-GCre system was to facilitate genome editing and lineage tracing in vivo. Genetic manipulation in vivo often involves stable insertion, which results in different patterns and levels of protein expression compared with in vitro plasmid overexpression systems. To assess the effects of stable integration of the NCre and CCre expression vectors on Split-Cre recombinase expression, the NCre and CCre constructs were inserted into the pMSCV-Thy1.1 retroviral vector and pMSCV-NGFR retroviral vector, respectively, and the two sets of virus particles were used to infect a mammalian cell line for stable insertion into the cell genome. The vectors also encoded the labeling proteins Thy1.1 and NGFR, respectively, to identify cells infected with both NCre and CCre retroviruses (i.e., double positive, Thy1.1+NGFR+) (Fig. 6, A and B). Double-positive cells accounted for approximately 40% of all infected cells, and the proportion of double-positive cells did not differ between the Split-GFP-Cre and Split-Spy-GCre systems. Statistical analysis of the fluorescence intensity of GFP in double-positive cells revealed that the mean fluorescence intensity of GFP was much higher with the Split-Spy-GCre system than the Split-GFP-Cre system, consistent with the results of the corresponding overexpression systems (Fig. 6C). To evaluate the effects of stable integration on Split-Cre recombinase activity, we cotransfected the CAG-loxp-STOP-loxp-TdTomato Cre activity detection reporter, and the fluorescence intensity of TdTomato in double-positive cells was analyzed. Compared with the Split-GFP-Cre system, the Split-Spy-GCre system significantly increased the activity of Split-Cre recombinase when stably integrated in the genome (Fig. 6D).

Figure 6.

SpyTag/SpyCatcher-assisted reconstitution in the stable integration system.A, schematic representation of the Split-Cre plasmids in this study. All NCre constructs were inserted into the pMSCV-Thy1.1 retroviral vector, and all CCre constructs were inserted into the pMSCV-NGFR retroviral vector. B, schematic representation of the experimental design. NIH3T3 cells were incubated with retroviruses encoding NCre and CCre for 6 h, followed by removal of the medium and replacement with 1 ml of the fresh medium. The infected cells were then analyzed for GFP fluorescence by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) or transfected with the CAG-loxp-STOP-loxp-TdTomato reporter vector to visualize Cre reconstitution efficiency. C, cells were harvested 24 h after retrovirus infection, and cells coexpressing NCre and CCre (double positive) were detected based on Thy1.1 and NGFR expression. The fluorescence intensity of GFP in double-positive cells is shown. D, cells with stable integration of the NCre and CCre constructs were transfected with the CAG-loxp-STOP-loxp-TdTomato reporter vector and harvested 24 h after transfection. The fluorescence intensity of TdTomato among double-positive cells is shown. ns, not significant. ∗∗∗p < 0.001 (ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test).

We also constructed a Split-Spy-Cre system without GFP in which SpyTag/SpyCatcher conjugation technology was used to directly connect NCre and CCre together after expressing Spy-NCreaa 59 (NCreaa 19–59-SpyTag) and Spy-CCreaa 60 (SpyCatcher-CCreaa 60–343), but the Cre recombinase activity was significantly lower in this system than in the Split-GFP-Cre system (Fig. S3).

Discussion

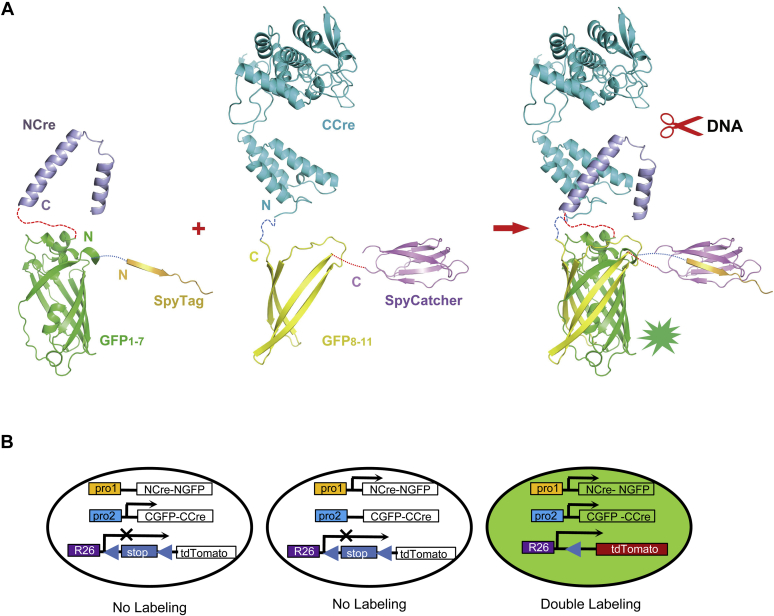

In the present work, we demonstrated that SpyTag/SpyCatcher conjugation technology was only able to increase Cre recombinase activity when NCre and CCre were linked by GFP, which we hypothesize is due to the ability of Split-GFP to form a dimer spontaneously. When SpyTag/SpyCatcher was used for conjugation, the dimerization of Split-GFP promoted stable dimerization of NCre/CCre to increase recombinase activity (Fig. 7A). In the absence of Split-GFP, the dimerization efficiency of NCre and CCre was strongly reduced, resulting in reduced recombinase activity. Thus, together, SpyTag/SpyCatcher conjugation technology and Split-GFP can maximize the activity of NCre/CCre (Split-Cre) recombinase. The Split-Spy-GCre system achieved Cre recombinase activity levels approaching those of full-length Cre. When applied in future in vivo experiments such as transgenic mice, the Split-Spy-GCre system may minimize problems of incomplete double gene-specific KO or low labeling efficiency due to poor NCre/CCre recombinase activity.

Figure 7.

Model of the SpyTag/SpyCatcher-assisted Split-GFP-Cre system.A, schematic representation of the fusion proteins generated in the Split-Spy-GCre system. In the system, SpyTag/SpyCatcher mediates protein conjugation, and NGFP and CGFP dimerize to form full GFP and promote stable dimerization of NCre/CCre to excise DNA. B, schematic representation of the structure of the Split-Cre transgenes. The expression of NCre-NGFP and the expression of CGFP-CCre are driven by different promoters. The CAG/Rosa26-loxp-STOP-loxp-TdTomato reporter is used to visualize Cre reconstitution; Cre recombinase activity excises the STOP cassette, and TdTomato is induced only when the two constructs controlled by different promoters are both expressed.

GFP is one of the most commonly used fluorescent proteins, and many articles have reported fusions of GFP and Cre for real-time labeling of Cre expression (18). Most of these strategies have involved fusion of GFP to the N terminus or C terminus of Cre. Our study is the first to insert GFP into the Creaa 59 site to construct a GFP-Creaa 59 fusion protein. The GFP-Creaa 59 fusion protein and WT Cre had comparable recombinase activity, suggesting that inserting GFP after aa 59 of Cre is an ideal fusion strategy for visualizing Cre expression in real time. By introducing this GFP real-time labeling method into the NCre/CCre system, we created the first system for detecting the simultaneous expression of two specific genes (the genes that initiate NCre/CCre expression) by detecting the expression of GFP (Fig. 7B), which expands the application range and effective detection sensitivity of the NCre/CCre system. Although we confirmed that the Split-Spy-GCre system increased Cre recombinase activity at low, medium, and high levels of NCre/CCre expression in cells in vitro, the levels of gene-specific NCre/CCre expression in vitro differ from those in mice. Therefore, the specific levels of NCre/CCre recombinase activity at different gene abundances in mice require further study.

Experimental procedures

Plasmid constructs

The intact GFPopt1−11 sequence reported previously was fused at the split point of Cre located between the 59th (linker1)/60th (linker2) or 104th (linker1)/106th (linker2) amino acids, and the resulting construct was cloned into the Hind III/Not I sites of pEGFP-N1 after deleting the EGFP gene (15). Intact Cre (GenBank No. KC800700.1) and ΔN17Cre (amino acids 2–18 truncated) were also cloned into the Hind III/Not I sites of pEGFP-N1.

To obtain the constructs for expressing the NCre-NGFP and CGFP-CCre fusion proteins (Split-GFP-Cre), the N-terminal (aa 19–59, aa 1–104) and C-terminal (aa 60–343, aa 106–343) fragments of Cre were first PCR amplified. The NCre fragment and sequences encoding NGFP, which comprises β-sheets 1 to 7 of GFPopt1–11, a short linker1 (SGGGG) and an NLS, were cloned into the EcoR I/Pst I sites of pCMV-Tag-2B to obtain the fusion expression construct NLS-NCre-Linker1-NGFP. Intact Cre and ΔN17Cre (aa 2–18 truncated) were also cloned into the EcoR I/Pst I sites of pCMV-Tag-2B. In a similar manner, CCre, CGFP, which encodes β-sheets 8 to 11 of GFPopt1−11, a short linker2 (GGGGS), and an NLS were cloned into the EcoR I/Pst I sites of pCMV-Tag-3B to generate the fusion expression construct NLS-CGFP-Linker2-CCre. Before constructing these vectors, the multiple cloning sites of pCMV-Tag-2B and pCMV-Tag-3B were replaced with a new multiple cloning site (BamH I EcoR I Sma I Pst I Spe I Hind III).

For activity comparisons, the flag-NLS-NCre-Linker1-NGFP, myc-NLS-CGFP-Linker2-CCre, Split-GCN4-Cre, Split-Co-InCre, flag-NLS-NCre-Linker1-NGFP-Linker3-SpyTag, myc-NLS-SpyCatcher-Linker3-CGFP-Linke2-CCre (Split-Spy-GCre), flag-NLS-NCre-Linker3-SpyTag, and myc-NLS-SpyCatcher-Linker3-CCre (Split-Spy-Cre) fragments were constructed and each inserted into pMSCV-IRES-Thy1.1 or pMSCV-IRES-NGFR to generate separate expression vectors. SpyCatcher and SpyTag were directly synthesized based on the reported sequences (Integrated DNA Technologies and GenScript Biotech Corporation) (19) and subcloned into the pMSCV-IRES-Thy1.1 expression vector.

Cell culture

The HEK 293T cell line (American Type Culture Collection), NIH3T3 cells, and Plat-E cells were grown at 37 °C and 5% CO2 in a humidified incubator in DMEM supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) FBS and 100 μg/ml penicillin/streptomycin solution.

Cell transfection

Transfection was performed using 60% confluent HEK 293T cells. In 24-well plates, HEK 293T cells were cotransfected with 200 ng of NCre plasmid, 200 ng of CCre plasmid, 400 ng of the activity detection vector (CAG-loxp-STOP-loxp-TdTomato or CAG-loxp-STOP-loxp-Luciferase) and, if necessary, 100 ng of the expression reporter vector (pMSCV-Thy1.1) using 2 μl of Lipofectamine 2000 transfection reagent (Invitrogen, 11668019) following the manufacturer’s recommended protocol and assayed 20 h later.

Luciferase assay

To characterize the reporter system, 24-well tissue culture plates were seeded with 1 × 106 HEK 293T cells/well. The cells were cotransfected with mixtures of plasmids using 2 μl of Lipofectamine 2000 transfection reagent (Invitrogen, 11668019) following the manufacturer's recommended protocol. At 20 h after transfection, the cells were washed with 1× PBS and lysed with 1× passive lysis buffer (Promega, catalog No. E1941). Dual-luciferase activity was measured using the Dual-Luciferase reporter assay system (Promega, catalog No. E1960) and GloMax 20/20 luminometer according to the specifications of the manufacturers. Data were normalized to control groups. Differences in relative light units were analyzed for statistical significance using the unpaired Student's t test.

Retroviral vectors and infection

All NCre constructs were inserted into the pMSCV-Thy1.1 retroviral vector, and all CCre constructs were inserted into the pMSCV-NGFR retroviral vector (Fig. 6A). To generate retroviruses by transient transfection, we transfected Plat-E cells with pMSCV using Lipofectamine 2000. After 2 days, the supernatant containing retrovirus was collected. For infection, NIH3T3 cells were plated in 24-well plates and incubated at 37 °C and 5% CO2 for 6 h, yielding a confluent monolayer. The medium was removed and replaced with 1 ml of NCre (Thy1.1+) virus stock plus 1 ml of CCre (NGFR+) virus stock. After 6 h, the medium was removed and replaced with 1 ml of fresh medium. The GFP fluorescence of the double-infected cells was analyzed by fluorescence-activated cell sorting. Double-infected cells were transfected with the CAG-loxp-STOP-loxp-TdTomato reporter vector to visualize Cre reconstitution efficiency.

Sample preparation and flow cytometry analysis

For flow cytometry analysis, 48 h after transfection, transfected HEK 293T cells were trypsinized into single cells with trypsin-EDTA (0.25%) (Gibco) and resuspended in 0.5 ml of PBS. Analytical flow cytometry was carried out on the FACSCalibur or LSR II instrument (BD Biosciences). Flow cytometry data analysis (gating and plotting) was conducted using FlowJo software (FlowJo, LLC).

Statistical analysis

Differences between two datasets were analyzed by ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test or an unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test with Prism (GraphPad) software. p Values of less than 0.05 were considered significant. Error bars denote the mean ± SEM.

Data availability

All data are contained in the article.

Supporting information

This article contains supporting information.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Zene Matsuda (China-Japan Joint Laboratory of Structural Virology and Immunology, Institute of Biophysics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China) for kindly providing of the Split green fluorescent protein (Split-GFP). This work was supported by the National Science and Technology Major Project of China (No. 2016YFA0201500, 2018ZX10301-208-002-002, and 2016ZX10004222-007), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81802872, 31870911), the Gold Bridge Funds of Beijing (No. ZZ21051), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (No. 3332018177), and the Doctoral Fund of Beijing Hospital (No. bj-2018-036).

Author contributions

X. W., X. Z., and J. M. conceptualization; X. W., J. Z., X. Z., and J. M. data curation; X. W., J. Z., X. Z., and J. M. formal analysis; X. W., J. Z., J. C., and W. X. investigation; X. W., X. Z., and J. M. methodology; X. W., J. Z., X. Z., and J. M. writing–original draft; X. W., J. Z., J. C., and W. X. project administration; X. W., J. Z., X. Z., and J. M. writing–review and editing; X. Z. and J. M. resources; X. Z. and J. M. supervision.

Edited by John Denu

Contributor Information

Xuyu Zhou, Email: zhouxy@im.ac.cn.

Jie Ma, Email: majie4685@bjhmoh.cn.

Supporting information

References

- 1.Nagy A. Cre recombinase: The universal reagent for genome tailoring. Genesis. 2000;26:99–109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sauer B. Inducible gene targeting in mice using the Cre/lox system. Methods. 1998;14:381–392. doi: 10.1006/meth.1998.0593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gu H., Marth J.D., Orban P.C., Mossmann H., Rajewsky K. Deletion of a DNA polymerase beta gene segment in T cells using cell type-specific gene targeting. Science. 1994;265:103–106. doi: 10.1126/science.8016642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Casanova E., Lemberger T., Fehsenfeld S., Mantamadiotis T., Schutz G. Alpha complementation in the Cre recombinase enzyme. Genesis. 2003;37:25–29. doi: 10.1002/gene.10227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.He L., Li Y., Li Y., Pu W., Huang X., Tian X., Wang Y., Zhang H., Liu Q., Zhang L., Zhao H., Tang J., Ji H., Cai D., Han Z. Enhancing the precision of genetic lineage tracing using dual recombinases. Nat. Med. 2017;23:1488–1498. doi: 10.1038/nm.4437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wei X., Zhang J., Gu Q., Huang M., Zhang W., Guo J., Zhou X. Reciprocal expression of IL-35 and IL-10 defines two distinct effector Treg subsets that are required for maintenance of immune tolerance. Cell Rep. 2017;21:1853–1869. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.10.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hirrlinger J., Scheller A., Hirrlinger P.G., Kellert B., Tang W., Wehr M.C., Goebbels S., Reichenbach A., Sprengel R., Rossner M.J., Kirchhoff F. Split-cre complementation indicates coincident activity of different genes in vivo. PLoS One. 2009;4 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim J.S., Kolesnikov M., Peled-Hajaj S., Scheyltjens I., Xia Y., Trzebanski S., Haimon Z., Shemer A., Lubart A., Van Hove H., Chappell-Maor L., Boura-Halfon S., Movahedi K., Blinder P., Jung S. A binary Cre transgenic approach dissects microglia and CNS border-associated macrophages. Immunity. 2021;54:176–190.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2020.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu J., Wang M., Yang X., Yi C., Jiang J., Yu Y., Ye H. A non-invasive far-red light-induced split-Cre recombinase system for controllable genome engineering in mice. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:3708. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-17530-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jullien N., Sampieri F., Enjalbert A., Herman J.P. Regulation of Cre recombinase by ligand-induced complementation of inactive fragments. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31 doi: 10.1093/nar/gng131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang P., Chen T., Sakurai K., Han B.X., He Z., Feng G., Wang F. Intersectional Cre driver lines generated using split-intein mediated split-Cre reconstitution. Sci. Rep. 2012;2:497. doi: 10.1038/srep00497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wen M., Gao Y., Wang L., Ran L., Li J., Luo K. Split-Cre complementation restores combination activity on transgene excision in hair roots of transgenic tobacco. PLoS One. 2014;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0110290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blakeley B.D., Chapman A.M., McNaughton B.R. Split-superpositive GFP reassembly is a fast, efficient, and robust method for detecting protein-protein interactions in vivo. Mol. Biosyst. 2012;8:2036–2040. doi: 10.1039/c2mb25130b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kondo N., Miyauchi K., Meng F., Iwamoto A., Matsuda Z. Conformational changes of the HIV-1 envelope protein during membrane fusion are inhibited by the replacement of its membrane-spanning domain. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:14681–14688. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.067090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang J., Kondo N., Long Y., Iwamoto A., Matsuda Z. Monitoring of HIV-1 envelope-mediated membrane fusion using modified split green fluorescent proteins. J. Virol. Methods. 2009;161:216–222. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2009.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zakeri B., Fierer J.O., Celik E., Chittock E.C., Schwarz-Linek U., Moy V.T., Howarth M. Peptide tag forming a rapid covalent bond to a protein, through engineering a bacterial adhesin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2012;109:E690–E697. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1115485109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guo F., Gopaul D.N., van Duyne G.D. Structure of Cre recombinase complexed with DNA in a site-specific recombination synapse. Nature. 1997;389:40–46. doi: 10.1038/37925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhou X., Bailey-Bucktrout S.L., Jeker L.T., Penaranda C., Martinez-Llordella M., Ashby M., Nakayama M., Rosenthal W., Bluestone J.A. Instability of the transcription factor Foxp3 leads to the generation of pathogenic memory T cells in vivo. Nat. Immunol. 2009;10:1000–1007. doi: 10.1038/ni.1774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Keeble A.H., Banerjee A., Ferla M.P., Reddington S.C., Anuar I., Howarth M. Evolving accelerated amidation by SpyTag/SpyCatcher to analyze membrane dynamics. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2017;56:16521–16525. doi: 10.1002/anie.201707623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data are contained in the article.