Abstract

Spectrin tetramers of the membranes of enucleated mammalian erythrocytes play a critical role in red blood cell survival in circulation. One of the spectrins, αI, emerged in mammals with enucleated red cells after duplication of the ancestral α-spectrin gene common to all animals. The neofunctionalized αI-spectrin has moderate affinity for βI-spectrin, whereas αII-spectrin, expressed in nonerythroid cells, retains ancestral characteristics and has a 10-fold higher affinity for βI-spectrin. It has been hypothesized that this adaptation allows for rapid make and break of tetramers to accommodate membrane deformation. We have tested this hypothesis by generating mice with high-affinity spectrin tetramers formed by exchanging the site of tetramer formation in αI-spectrin (segments R0 and R1) for that of αII-spectrin. Erythrocytes with αIIβI presented normal hematologic parameters yet showed increased thermostability, and their membranes were significantly less deformable; under low shear forces, they displayed tumbling behavior rather than tank treading. The membrane skeleton is more stable with αIIβI and shows significantly less remodeling under deformation than red cell membranes of wild-type mice. These data demonstrate that spectrin tetramers undergo remodeling in intact erythrocytes and that this is required for the normal deformability of the erythrocyte membrane. We conclude that αI-spectrin represents evolutionary optimization of tetramer formation: neither higher-affinity tetramers (as shown here) nor lower affinity (as seen in hemolytic disease) can support the membrane properties required for effective tissue oxygenation in circulation.

Significance

Spectrin tetramers, made by the association of pairs of αβ-spectrin dimers, are essential for red blood cell function. αIβI-spectrin tetramer is a unique feature of highly deformable enucleated mammalian red blood cells; αIIβII is a more stable tetramer found in other tissues. Here, we have developed a mouse model to investigate the connection between low-affinity red cell spectrin tetramer formation and cell deformability. Mice expressing the high-affinity αII-spectrin binding site for βI-spectrin have erythrocytes with lower deformability than wild-type. Lability of the αIβI-spectrin tetramer at the self-association site enables membrane skeleton remodeling in intact red blood cells and is an essential component of the red cell deformability.

Introduction

Mammalian red blood cells are extremely deformable; this is a requirement for effective tissue oxygenation and to survive the large deformations experienced as they transverse the vasculature. Structurally, the red blood cell membrane is a composite material in which the spectrin-based membrane skeleton is anchored to the lipid bilayer via two major protein complexes: an ankyrin-based complex (containing, among other proteins, Band 3, Rh/RhAG, and protein 4.2) and an actin-based complex (containing, among other proteins, 4.1R, adducin, dematin, Band 3, and glycophorin C) (1, 2, 3). The deformability of the red blood cell is a combination of mechanical properties of the cell membrane and excess surface area relative to its volume. Although the structural organization of the various components of the red blood cell membrane is well described, the structural basis for its deformability is not fully understood (4).

Red cells undergo extensive elastic deformations during passage through the microvasculature while maintaining constant membrane surface area; the area dilation is energetically highly unfavorable. The principal resistance to area dilation (stretching) and bending is provided by the lipid bilayer, whereas the resistance to shear deformation is provided by the membrane skeleton that is anchored to the lipid bilayer (5).

Spectrin tetramers are the main structural component of the red blood cell membrane skeleton, consisting of two heterodimers of αI- and βI-spectrin interacting head to head at the dimer self-association site. Spectrins are polypeptides of multiple triple-helical repeats, 20 1/3 for αI-spectrin and 16 2/3 for the shorter βI-spectrin (6,7). At the self-association site, the single helix of the R0 repeat at the N-terminus of αI-spectrin interacts with the two helices of the R17 repeat at the C-terminus of βI-spectrin, forming a complete triple-helical repeat (8, 9, 10).

αI and βI erythrocyte spectrins are members of a family of proteins encoded by multiple genes in mammals; two encode α-spectrin, and five encode β-spectrin. All spectrins can form tetramers (α2β2) by self-association of spectrin αβ dimers (11). The relative strength of spectrin dimer interaction at the self-association site differs markedly between the erythroid αI-βI-spectrin and the abundant αII-βII-spectrin found in solid tissues, with αII-βII-spectrin tetramers being significantly more stable (11). The significance of the reduced strength of erythroid dimer self-association remains unclear; one current hypothesis is that it allows rearrangement of the membrane skeleton under the shear force experienced in the circulation (4).

Through phylogenetic analysis, Salomao et al. (12) showed that the gene encoding αI-spectrin is the result of duplication of the ancestral α-spectrin common to all animals. The duplication event was coincident with the emergence of mammals. One of the resulting pair, αII-spectrin, retained the ancestral characteristics of high thermal and mechanical stability (11), together with high-affinity binding to spectrin β-chains (11). The other of the pair, αI-spectrin, was neofunctionalized for highly deformable, enucleated erythrocytes; it has a more flexible structure deriving from the lower stability of some of its triple-helical repeats (12) and lower-affinity binding to β-chains (11). The precise nature of the physiological benefits of this neofunctionalization, the lower affinity for β-chains, and how they relate to the advantages of enucleated erythrocytes are not clear.

In this study, we explored the contribution of the binding strength of αβ dimer at the self-association site to the biophysical properties of the red blood cell membrane. To achieve this, we generated a genetically modified mouse model in which the αI-spectrin self-association domain was exchanged for the αII-spectrin self-association domain. These mice are viable and do not present with significant anemia. Functional characterization of the genetically modified red cells showed that increasing the strength of the spectrin dimer self-association results in significantly reduced membrane deformability, with marked reduction in deformation-induced remodeling of the spectrin skeleton of intact red cells. We conclude that αI-spectrin represents evolutionary optimization of spectrin dynamics to support the unique membrane requirements of mammalian erythrocytes in circulation.

Materials and methods

Generation of αII-spectrin knock-in mice

αII-spectrin knock-in (αIIβI) mice were generated by the Ingenious Targeting Laboratory (Ronkonkoma, NY). Exons 1, 2, and 3 and part of exon 4 of the Spta1 gene spanning an ∼5.9 kb region were replaced with the exons 2 and 3 and part of exon 4 of Sptan1, spanning an ∼4.9 kb region. The mice were initially generated as a 129 × C57 hybrid and backcrossed for at least 10 generations into a C57BL/6 background. In experiments involving wild-type (WT) mice, pure C57BL/6 inbred mice were used. All animals were at least 3 months of age. Both sexes were used, and we did not observe differences between males and females. The mice were maintained at the animal facility of New York Blood Center under specific-pathogen-free conditions according to institutional guidelines. Animal protocols were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Genotyping

Genomic DNA was extracted from mouse tails. Genotyping was performed by multiplex PCR. The αI-spectrin allele was amplified using primers: αI forward 5′-ATG GAA ACT CCA AAG GAA ACT GTG AGT A-3′ and αI reverse 5′-GTC ATT CCA CAA GAG CAC AAT TTT TAG T-3′. Similarly, the αII-spectrin allele was amplified using primers: αII forward 5′-CAT TAT ACG AAG TTA TGG TAC CTG CAG-3′ and αII reverse 5′-TCA ATT CCT AGT ACT CTG TCT GCC TCC-3′.

Generation of anti-spectrin antibodies

Polyclonal antibody against αI-spectrin N-terminus, αI-spectrin C-terminus, or αII-spectrin N-terminus was raised in rabbit using recombinant αI N-terminus or αI 20-C- or αII N-terminus as antigen. The antibodies were affinity purified on Sulfolink Coupling Resin (Pierce Biotechnology, Waltham, MA). Antibody specificity was examined by Western blotting using the corresponding recombinant protein.

Characterization of α-spectrin in αIIβI mice red cells

The red blood cells (RBCs) of the αIIβI mice were characterized by native gels and Western blot analysis. Ghosts prepared by lysis of RBCs in ice-cold hypotonic buffer A (5 mM Tris, 5 mM potassium chloride (pH 7.4)) were twice washed in the same buffer and twice more with extraction medium (buffer B: 0.25 mM sodium phosphate (pH 7.4)). Spectrin was extracted by overnight dialysis at 4°C in buffer B and recovered in the supernatant after centrifugation for 20 min at 20,000 × g. Protein concentration was determined spectrophotometrically, taking E(280 nm; 1 mg mL−1; 1 cm) = 1.07. The extracted spectrin was then examined by gel electrophoresis in the native state in a Tris-bicine buffer system, run in the cold (13) and stained with GelCode Blue. Membrane proteins from whole RBC ghosts separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) in 4% polyacrylamide gels and were transferred to nitrocellulose membrane (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Membranes were blocked for 1 h in PBS-T (PBS + 0.1% Tween 20) containing 4% nonfat milk and 1% BSA, followed by 1-h incubation with relevant α-spectrin primary antibodies. After washing with PBS-T, the nitrocellulose membrane was incubated with the horseradish-peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (anti-rabbit). Immunoblots were visualized using the G:BOX gel imager (Imgen Technologies, New City, NY) by the enhanced chemiluminescence method.

Preparation of recombinant αII-spectrin fragment

The cDNA encoding the N-terminal region of nonerythroid αII-spectrin (amino acids 1–149) was expressed from the vector pGEX-2T, as described previously (11). The fragment was purified on a glutathione-Sepharose column, dialyzed, and concentrated using Centricon Plus-70 centrifugal filter units (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO).

Incorporation of αII-spectrin fragment into erythrocyte ghosts

Total blood was obtained from WT or αIIβI mice by cardiac puncture. RBCs were washed three times in ice-cold isotonic buffer and then lysed in 35 volumes of ice-cold buffer A to obtain ghosts. After three washes in 35 volumes of buffer A, ghosts (5 × 109/mL) were incubated with the indicated concentrations of αII-spectrin fragment for 10 min on ice. Isotonicity was restored by adding 0.1 volume of 1.5 M potassium chloride (pH 7.4) for 10 min on ice, and ghosts were resealed by incubating them at 37°C for 40 min.

Extraction and analysis of spectrin from resealed ghosts

After resealing, the ghosts were lysed again in 35 volumes of buffer A. 10 μL of packed ghosts was washed three times in isotonic saline and subjected to SDS-PAGE and Western blot with an anti-GST (anti-glutathione-S-transferase) antibody to confirm incorporation of the αII-spectrin fragment. The remaining ghost population was washed two additional times in ice-cold buffer A, and spectrin was then extracted in buffer B overnight at 4°C. After centrifugation (20,000 × g, 20 min), the spectrin tetramer, dimer, and their complexes with the αII-spectrin fragment were resolved by gel electrophoresis in a Tris-bicine buffer system run in the cold (13).

Measurements of red cell deformability by ektacytometry

Blood (50–200 μL) was drawn from mice via tail, submandibular vein (survival), or cardiac puncture (nonsurvival). RBC deformability was measured using an ektacytometer as previously described (14). RBCs were suspended in 4% polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP, 360 kDa) PBS solution (5 mL PBS-PVP + 25 μL whole blood) and deformed in a Couette viscometer, in which the outside cylinder is spun to obtain defined values of applied shear stress. The change in the laser diffraction pattern of the erythrocytes was recorded as they were subjected to increasing values of applied shear stress (0–30 Pa). The ratio of principal axes of the elliptically shaped diffraction pattern designated deformability index (DI) is a measure of the extent of cell deformation. The biomechanical origin of the shape of the DI curve is complex, but the reproducibility and certain characteristics are useful measures of the deformability of the red cell. At DImax, the value of the DI attained at the maximal value of applied shear stress of 30 Pa is a measure of cellular deformability. Decreased values of DImax reflect decreased surface area and hence increased sphericity of RBCs. As the rate of change of the DI at lower shear rates is a good indicator of the red cell membrane stiffness, illustrated best in the Eadie-Hofstee transformation of the DI curve (15), linear fitting of the Eadie-Hofstee transformed data allowed the maximal deformability index (DImax) and shear stress at half maximal deformation (SS1/2) to be extracted (15,16).

Rheoscope imaging

Deformation of RBCs from WT and αIIβI mice in Couette flow were observed and imaged in a transparent counter-rotating cone and plate rheoscope (17) (model MR-1; Myrenne Instruments, Rancho Cordova, CA) with a cone angle of 2°, mounted on a Leitz Diavert inverted microscope using a Leitz long-distance 32× (NA 0.4) objective (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany). 5 μL whole blood in 1 mL 8% PVP-PBS solution was used, and a series of observations were made across the full speed range 1–43 RPM (revolutions per minute) of the instrument. The images were taken using a Nikon DS-Qi camera (Tokyo, Japan) with a 1-ms exposure.

Osmotic fragility analysis

5 μL of packed RBCs was suspended in 2 mL of NaCl solutions of varying osmolarities and incubated for 20 min at room temperature. After low-speed centrifugation (200 × g, 3 min), the absorbance of the supernatant was measured at 540 nm to quantify the released hemoglobin. The absorbance at 540 nm for the different osmolarities was normalized against complete red blood cell lysis using water (18).

Thermal sensitivity

Whole blood was washed three times in PBS, and 5 μL of packed RBCs was suspended in 1 mL of PBS and 100 μL aliquoted into 10 PCR tubes. The tubes were heated using a gradient capable PCR thermal cycler, and the block was heated to 45°C for 1 min and 45–50°C gradient for another 15 min. Heated cells were fixed by adding 100 μL of 2% glutaraldehyde in PBS to each tube. The samples were examined for echinocytic and spherocytic cells by phase contrast microscopy and the numbers of normal and abnormal cells counted (19).

Blood analyses

Whole blood was collected from WT or αIIβI mice using an EDTA-coated capillary from the retro-orbital sinus. Complete blood counts were obtained using the ADVIA 120 Hematology System (Siemens, Munich, Germany).

Optical microscopy

High-resolution images of intact RBCs from WT and αIIβI mice were acquired using a Nikon DS-Qi camera mounted on a Nikon Ti-U inverted microscope with a Soret band filter (413 nm, 10 nm) (Edmund Optics, Barrington NJ) (20).

Fluorescence-imaged micropipette deformation

The density distribution of proteins within the red blood cell membrane during deformation was measured using the combination of fluorescent imaging and micropipette aspiration as described by Discher et al. (21), with some additional modifications. Whole blood was washed three times in mouse-PBS (MPBS) (10 mM NaCl, 155 mM KCl, 10 mM glucose, 1 mM MgCl2, 2.5 mM KHPO4 (pH 7.4)) (22). Band 3 was chemically labeled using methods previously described (23). Briefly, 5 μL of packed RBCs was incubated in 200 μL of 80 μg/μL Alexa Fluor 488 C5 Maleimide (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) in MPBS for 40 min. They were washed three times in MPBS and then suspended at 1 μL packed cells per mL MPBS + 0.1% bovine serum albumin. The labeled RBC suspension was injected into an imaging chamber consisting of a microscope slide and coverslip separated by four layers of parafilm. Individual cells were aspirated into glass micropipettes with internal diameters between 1 and 2 μm. The micropipettes were pulled from glass capillary tubing using a Sutter P-1000 micropipette puller (Sutter, Novato, CA) and cut to the required diameters using a home built microforge. The micropipettes were back filled using a Microfil capillary (World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL) with MPBS and connected to a manometer to control the aspiration pressure. The applied pressure was sufficient to aspirate the cell to the extent that the aspirated portion of the cell was maximal for the available surface area, and the proportion of the cell membrane outside the pipette was a sphere.

In this study, the aspiration length was adjusted by exchanging the suspending solution while individual cells were held in the micropipette. By using computer-controlled syringe pumps exchanging the PBS buffer between solutions of 250 and 150 mOsmol, we enabled the imaging of a single cell through a range of aspirated tongue lengths. Fluorescent images of the aspirated RBCs were acquired using a Nikon DS-Qi camera mounted on a Nikon Ti-U inverted microscope. All image analysis was done in ImageJ (24) and semiautomated with custom plugins. From measurements of the normalized aspiration length (L/Rp), the outside sphere radius (Rs), the normalized intensity profile along the aspiration, and the entrance intensity (ρe) and cap intensity (ρc) were computed.

Statistics

These data are obtained from at least three independent experiments using blood from at least three individual mice. Statistical significance was determined by two-tailed t-tests for unpaired samples with α = 0.05. Data are expressed as the mean ± SD (standard deviation); p-values > 0.05 were considered statistically significant and indicated by asterisks (∗p ≤ 0.05, ∗∗p ≤ 0.01, ∗∗∗p ≤ 0.001).

Results

Generation and characterization of αIIβI knock-in mice

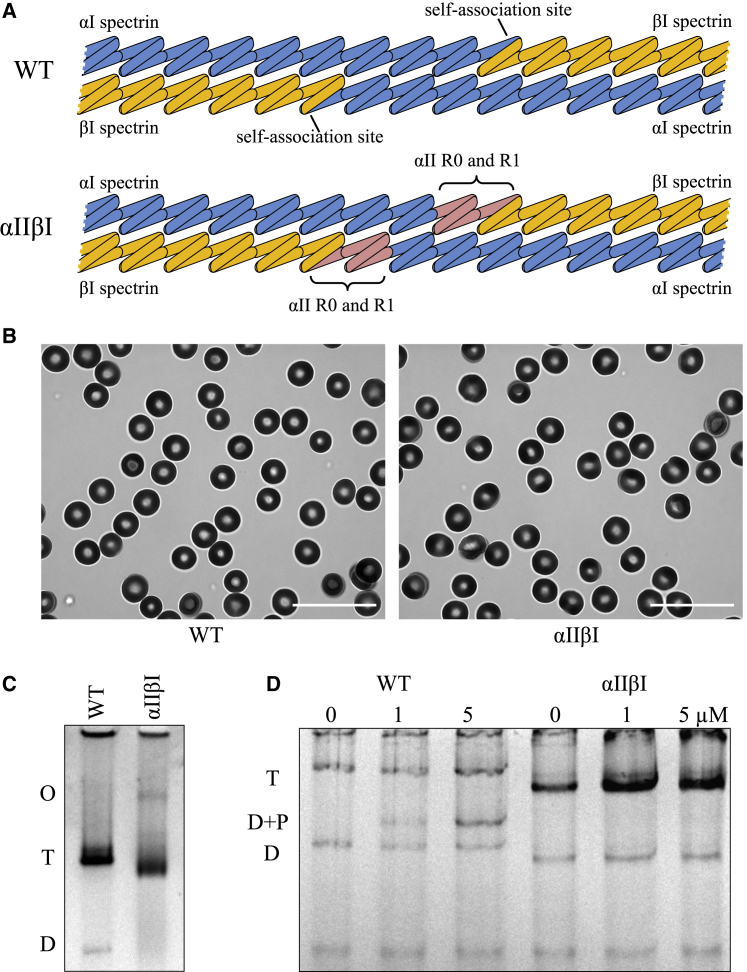

To assess the contribution of the binding strength of αβ dimer at the self-association site on the mechanical properties of the red blood cell membrane, a knock-in strain of mice was generated in which the labile αI-βI-spectrin tetramer was replaced by a much higher-affinity αII-βI-spectrin tetramer by exchanging exons 2–4 of αI-spectrin (Spta1) with the corresponding exons of αII-spectrin (Sptan1). This results in mouse RBCs that express hybrid α-spectrin protein in the erythrocyte that has the N-terminus domains R0 and R1 from αII-spectrin in place of the N-terminus domains R0 and R1 from αI-spectrin. The R0 and R1 N-terminus domain interacts with the C-terminal domain of β-spectrin to form the heterodimer and one half of the spectrin tetramer, as illustrated in Fig. 1 A.

Figure 1.

Development and initial analysis of the αIIβI mouse model. (A) Partial domain structures of spectrin in WT and αIIβI knock-in mouse showing self-association sites and the location of the substituted αII repeats. (Upper) WT spectrin with αI-spectrin on the left (blue) and βI-spectrin on the right (yellow). The interaction of α- with β-spectrin occurs between α-R0 and βI-R17. (Lower) αIIβI knock-in mouse spectrin; red indicates α-spectrin R0 and R1 from αII, and R2–R4 from αI-spectrin are in blue. β1-spectrin is unchanged in this mouse model. (B) Brightfield microscopy of RBCs from WT and αIIβI mice imaged using a Soret bandpass filter (413 nm, 10 nm). Scale bars, 20 μm. (C) Analysis of the oligomerization state of spectrin in each mouse strain. Spectrin was extracted in low ionic strength medium at low temperature from erythrocytes from each mouse strain. The extracts were separated by nondenaturing gel electrophoresis and stained with Coomassie. The positions of spectrin dimers (D), tetramers (T), and higher oligomers (O) are indicated. (D) Increasing concentrations of αII-peptide resealed into RBC ghosts from WT and αIIβI mice. T, tetramer; D + P, dimer-peptide complex; D, dimer. To see this figure in color, go online.

The genotypes of all mice were determined by PCR. Amplification with the primer pairs used produced a 340 bp fragment in WT mice and 700 bp fragment in the αIIβI knock-in mouse. Although the 340 bp fragment was a feature of WT mice, the homozygous knock-in mice showed only the 700 bp fragment, whereas, as expected, heterozygous knock-in mice showed both fragments (Fig. S1).

Further validation of the knock-in of the hybrid α-spectrin was shown by SDS gel and Western blot analysis of red blood cell membrane ghosts from WT and homozygous αIIβI mice (Fig. S2). The overall patterns of proteins revealed in Coomassie blue-stained SDS gels (Fig. 1 B, left panel) appeared essentially identical between the strains, indicating that the knock-in does not result in any major change to overall protein composition of the membranes. The antibody to the N-terminus of αI-spectrin, but not the antibody to the N-terminus of αII-spectrin, recognized the spectrin of RBCs of WT mice (Fig. S2). In contrast, and as expected, only the antibody to the N-terminus of αII-spectrin, but not the antibody to the N-terminus of αI-spectrin, recognized the spectrin of RBCs of homozygous αIIβI mice. Importantly, the antibody to the C-terminus of αI-spectrin recognized the spectrin in RBCs of both WT and αIIβI mice. Thus, the knock-in strategy we used successfully generated a full-length hybrid αI-spectrin with the self-association domain of the N-terminus of αII-spectrin in the RBCs of αIIβI mice.

Complete blood counts with an Advia 120 hematology analyzer (Siemens) demonstrated normal indices with no significant differences between WT and αIIβI mice (Table S1). Although statistically significant differences in RBC count, hemoglobin concentration, and hematocrit are observed between the WT and αIIβI mice, the difference is small and well within normal parameters for normal healthy mice and would only be considered to be very mildly anemic (25). In addition, both WT and αIIβI mice presented similar erythrocyte morphology, both appearing as normal biconcave discocytes, as shown in the representative microscopy images in Fig. 1 B.

Previous studies have reported altered erythrocyte membrane deformability despite normal red cell parameters (26). The formation of spectrin dimers, tetramers, and higher-order oligomers in intact membranes was assessed by extracting the spectrin from isolated membranes under conditions that preserve its native state, i.e., using very low ionic strength media at 4°C. The resulting extracts were analyzed by nondenaturing gel electrophoresis (Fig. 1 C). As expected, the spectrin extracts from WT mice showed mainly tetramers with some dimers but without indication of higher-order oligomers. Extracts from αIIβI mice showed similar tetramer composition but with no measurable dimers, instead showing a band indicating enhanced higher oligomer formation. Note also that the tetramer in the αIIβI mice extracts has a faster electrophoretic mobility than WT, consistent with the genetic modification leading to a small change in the overall conformation of the tetramer.

Univalent fragments of α-spectrin, containing the dimer self-association site, are known to bind to spectrin on the membrane as tetramers undergo dynamic association and dissociation (5,12). If spectrin tetramers in intact membranes are more dynamic in WT than αIIβI, then an exogenous αII-spectrin peptide fragment should incorporate more readily into WT than αIIβI membranes. To test this, the αII-peptide was added to ghosts from WT or αIIβI cells; the ghosts were resealed and incubated at 37°C to promote incorporation of the peptide. Fig. 1 D shows significant incorporation of the fragment into the spectrin of WT ghosts; by contrast, spectrin from αIIβI incorporated little to none. This result is consistent with αIIβI tetramers being much less labile than WT.

Surface area of αIIβI and WT RBCs

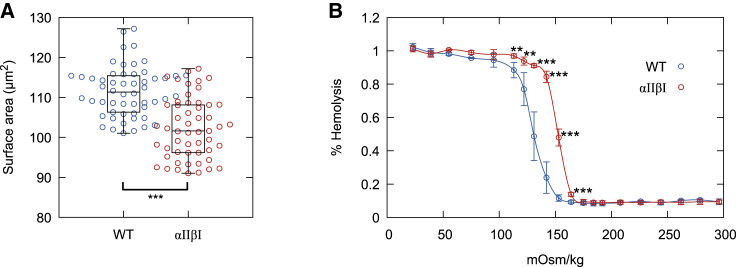

The surface area of RBCs was measured geometrically using the micropipette aspiration method (27,28). For αIIβI cells, it was 102.2 ± 7.6 μm2, an ∼10% loss compared to that of WT mice, 111.5 ± 6.2 μm2 (Fig. 2 A). The osmotic fragility of RBCs was measured by exposure to hypotonic stress by suspending them in low ionic strength buffer solutions (Fig. 2 B). RBCs from αIIβI mice show significantly less resistance to hemolysis with 50% lysis at 150 mOsm/kg in contrast to 50% lysis at 130 mOsm/kg of RBCs from WT mice. Resistance to hemolysis is primarily defined by the cell surface area/volume ratio (cell sphericity) (29,30), and we conclude that increased osmotic fragility arises from the increased sphericity of αIIβI cells, consistent with their decreased cell surface area.

Figure 2.

Effect of modified αIIβI on membrane stability. (A) Surface area measured geometrically by micropipette aspiration. WT mean surface area = 111.5 ± 6.2 μm2 (n = 53 cells), and αIIβI = 102.2 ± 7.6 μm2 (n = 44 cells), ~8.3% loss of surface area. (B) Osmotic fragility curves of WT (n = 12 mice) and αIIβI (n = 5 mice) RBCs; error bars represent the SD and ∗p ≤ 0.05, ∗∗p ≤ 0.01, ∗∗∗p ≤ 0.001 by unpaired Student’s t-test. To see this figure in color, go online.

Thermal sensitivity of αIIβI knock-in and WT RBCs

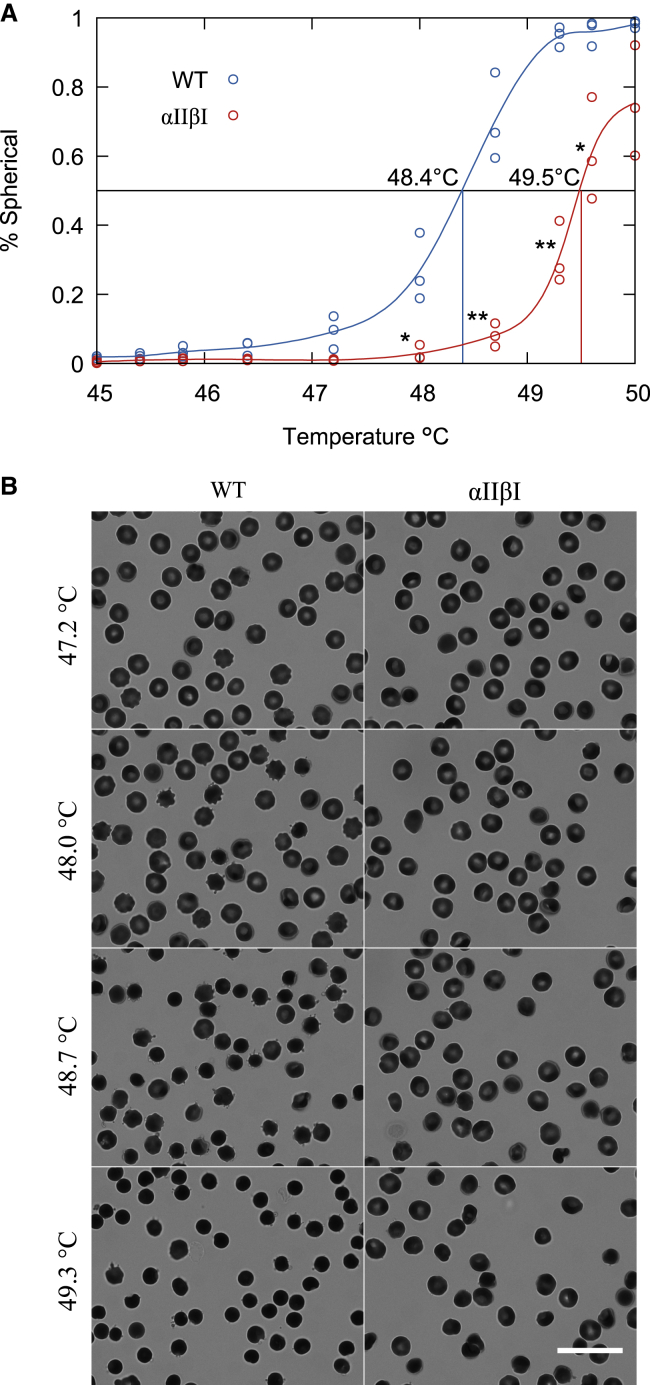

Erythrocytes have been shown to have particular sensitivity to temperature (19,31). Although human RBCs maintain their discoid morphology upon heating to 48°C, increasing the temperature to 49–50°C induces rapid shape transition with membrane fragmentation and generation of spherocytes (19). Diluted suspensions of RBCs from αIIβI and WT mice were heated to temperatures between 45 and 50°C. The RBCs from WT mice began to transform to echinocytes (crenated) at 47°C, with significant crenations between 48 and 49°C, and were 100% spherocytic at 49°C (Fig. 3 A), with 50% of RBCs crenating at 48.4°C. In contrast, RBCs of αIIβI mice did not start to crenate until 48–49°C. with significant crenation not occurring until >48.5°C, with 50% crenated RBCs occurring at 49.5°C. At 50°C, αIIβI RBCs did not reach 100% spherocyte cells. Shown in Fig. 3 B are brightfield images of heat-induced morphological changes in RBCs of both WT and αIIβI samples between 47 and 49°C. These findings imply that the more stable dimer-dimer interaction of αII-βI bestows increased thermal resistance to RBCs of αIIβI knock-in mice.

Figure 3.

Thermal stability of red blood cells from WT and αIIβI mouse. (A) The fraction of heat-induced spherical erythrocytes as at various temperatures from 45 to 50°C. Dashed lines show the temperature at which 50% of red blood cells are spherical. ∗p ≤ 0.05, ∗∗p ≤ 0.01, ∗∗∗p ≤ 0.001 by unpaired Student’s t-test. (B) Brightfield microscopy of red blood cells from WT and αIIβI mice imaged using a Soret bandpass filter (413 nm, 10 nm) after heating erythrocytes. Scale bars, 20 μm. To see this figure in color, go online.

Deformability of RBCs as assessed by Couette flow

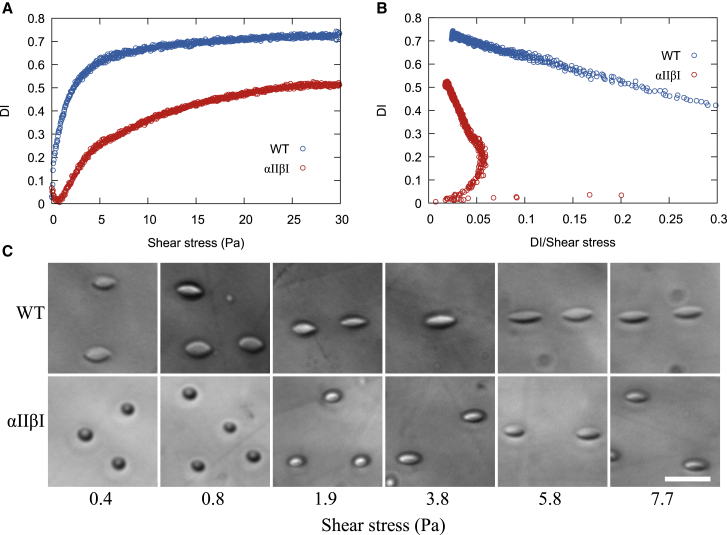

The effect of the modified αII-βI dimer on the deformability of RBCs was measured by ektacytometry (14). The maximal deformability index at the highest shear stress (DImax) in the higher-suspending medium viscosity reached a plateau defined as DImax, which is less for the αIIβI mice samples (DImax 0.67 ± 0.015) compared to the WT samples (DImax 0.75 ± 0.015), as shown in Fig. 4 A (Student’s t-test, p = 4.2 × 10−5). As the maximal DI should be only limited by the membrane surface area of the RBCs, provided the shearing does not result in cell fragmentation and loss of membrane area, the noted decrease in DImax is the result of ∼10% decrease in surface area of αIIβI mice RBCs. Importantly, the peak DI of the αIIβI cells did not reach a plateau at the maximal applied shear stress of the instrument in the suspending medium of lower viscosity (indicated in the Eadie-Hofstee transformed data shown in Fig. 4 B). The αIIβI cells clearly need significantly greater shear force to deform to the same extent as the WT cells. For example, the WT cells reach half their maximal deformation (SS1/2) at a shear stress of 1.13 ± 0.097 Pa, whereas the αIIβI samples needed a shear stress of 8.54 ± 0.51 Pa (Student’s t-test, p = 2.9 × 10−6) to reach the same extent of deformation, implying decreased membrane deformability (32). Additionally, at low shear stresses <1 Pa, the αIIβI cells did not undergo tank threading but instead showed DI values consistent with cell tumbling (33,34).

Figure 4.

The deformability of WT and αIIβI mouse red blood cells as a function of shear stress as measured by ektacytometry. WT sample is shown in blue and the αIIβI shown in red. (A) The deformability index (DI) as a function of shear stress. (B) Eadie-Hofstee transformation of the ektacytometry data in (A), with the DI as a function of DI/(shear stress). (C) Rheoscope images of WT and αIIβI red blood cells subject to increasing shear stress. Scale bars, 20 μm. To see this figure in color, go online.

This behavior is further demonstrated in the images of the RBCs of deformed by the rheoscope in Fig. 4 C. In those, αIIβI RBCs have significant resistance to shear deformation compared to WT mice. WT RBCs tank tread even at very low shear stress 0.4 Pa, whereas the αIIβI RBCs require shear stress >2 Pa to start tank treading.

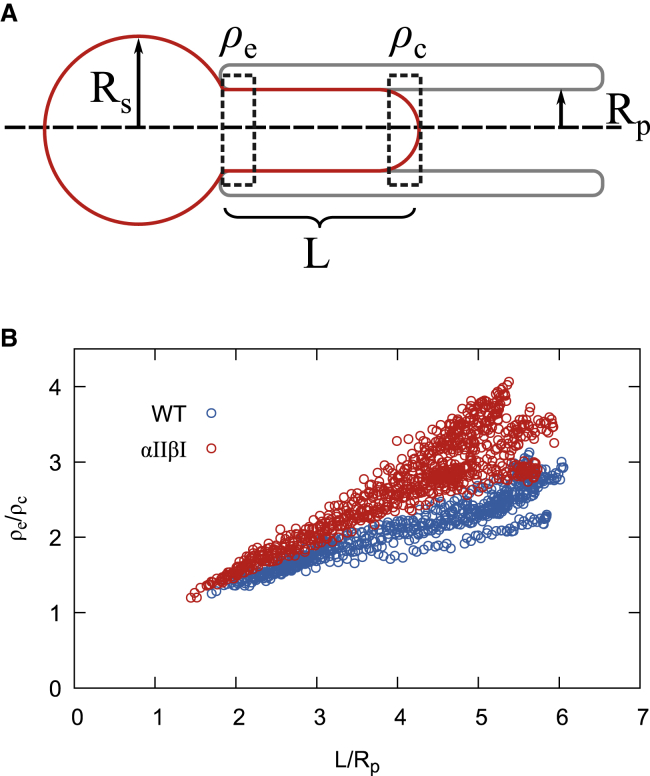

Membrane skeleton density of deformed αIIβI and WT as assessed by fluorescence-imaged microdeformation

Fluorescence-imaged microdeformation, developed by Discher et al. (21,23), is an effective way to determine the connectivity of membrane proteins such as Band 3 to the underlying membrane skeleton. The method typically involves imaging many cells suspended in isotonic buffer aspirated into micropipette with increasing aspiration pressures to determining the entrance (ρe) and cap (ρc) densities as a function of the aspirated cell length (Fig. 5 A). Changing the osmolality of the buffer in the chamber while the cell is aspirated in the micropipette enables the measurement of ρe and ρc at many aspiration lengths for each cell (Video S1). The ratio of ρe/ρc for Band 3 in the αIIβI cells using this strategy showed a significantly steeper gradient than that seen for WT cells (Fig. 5 B). As the measured Band 3 density correlates to the membrane skeletal density distribution, this finding implies that increased affinity of spectrin interaction at the self-association site results in greater resistance to membrane skeleton remodeling. By fitting Eq. 1 below for the Band 3 density data obtained for each aspirated cell, where K is the area dilation modulus, μ the shear modulus, Rp the micropipette radius, and L the aspiration length, a value for the parameter (K/μ) can be derived. For the αIIβI cells, the ratio of the area stretch/shear moduli (K/μ) was determined to be 1.10 ± 0.22 (n = 14) compared to 1.99 ± 0.32 (n = 8) for WT cells (Student’s t-test, p = 4.4 × 10−5) (21,23).

| (1) |

Figure 5.

Fluorescence-imaged microdeformation. (A) Illustration of the aspirated red blood cell; the red cell membrane is indicated by the red line, and the gray indicates the micropipette. Rs, radius of spherical portion of cell outside micropipette; L, the length of aspirated portion of red cell; ρe, the fluorescent intensity at pipette entrance; ρc, the fluorescent intensity at cap of aspirated portion; Rp, the internal radius of the micropipette. (B) The ratio of ρe/ρc of Band 3 in WT (blue) (n = 8 cells) and αIIβI (red) (n = 14 cells) as a function of the normalized aspiration length L/Rp. To see this figure in color, go online.

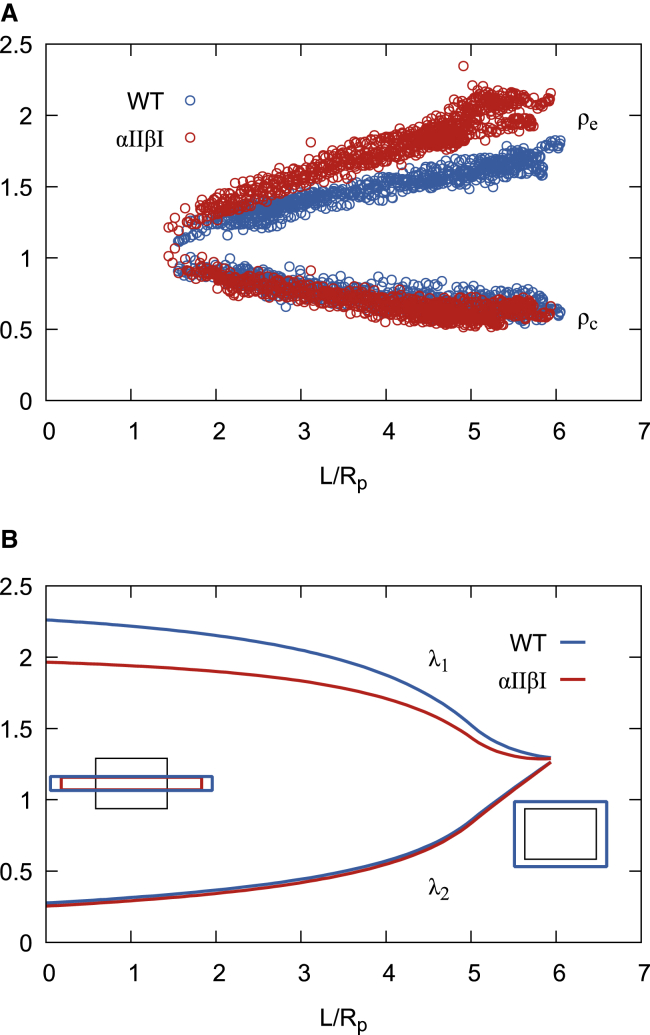

In the absence or reduction of remodeling, the membrane skeleton undergoes a larger shear deformation before breakage of the spectrin self-association site, and this will be reflected by higher ρe intensity. Indeed, the intensity at the micropipette entrance ρe is increased for all aspirated αIIβI red cells compared to the WT cells, whereas the ρc intensity showed a much smaller difference between the two cell types (Fig. 6 A). This is a result of the difference in the dominant type of deformation of the membrane skeleton at the pipette entrance and cap of the aspirated cell. At the micropipette entrance, skeletal deformation is mainly due to shear deformation, whereas at the cap, the deformation is dominated by area dilation. ρc shows only a small difference intensity between the WT ρc = 0.622 ± 0.050 compared to 0.525 ± 0.072 for the αIIβI cells at L/Rp = 6 (Student’s t-test, p = 0.0016). This indicates the maximal area dilation of the membrane skeleton is approximately the same, suggesting the maximal area extension of the membrane skeleton is constant, consistent with a spectrin tetramer length invariance between the two cell types. By contrast, ρe was significantly different between WT and αIIβI cells; at L/Rp = 6, WT ρe intensity was 1.71 ± 0.054, compared to 2.15 ± 0.098 for the αIIβI cells (Student’s t-test, p = 0.0025). This is consistent with a changed rate of remodeling spectrin tetramers in αIIβI cells.

Figure 6.

Fluorescence-imaged microdeformation. (A) ρe and ρc as a function of the normalized aspiration length L/Rp for aspirated red cells from both WT (blue) (n = 8 cells) and αIIβI (red) (n = 14 cells) mice. (B) The computed principal components of membrane skeleton deformation as a function L/Rp for a cell with an aspiration length L = 6. Insets show the change in shape of a unit area of membrane skeleton for the entrance of the micropipette (left) and the cap (right). To see this figure in color, go online.

Estimates of the principal stretch ratios of the membrane skeleton can be determined from the relative membrane skeleton density using methods described previously (21,23,35). Briefly, by conservation of mass and considering the aspirated tongue to be an axisymmetric deformation of a portion of a spherical surface radius R0 with uniform density, Eq. 2 can be used to estimate the principal stretch ratio λ2 and then λ1.

| (2) |

Because the intensity gradients of the aspirated portions of the cells are nearly perfectly linear, the mean ρe and ρc for a give aspiration length (L = 6) for each sample are used to model the ρ intensity profile to calculate the principal stretches shown in Fig. 6 B. Using this method, we find in WT cells λ1 = 2.18 ± 0.069, λ2 = 0.268 ± 0.006 at the pipette entrance and λ1 = λ2 = 1.27 ± 0.054 at cap, whereas in αIIβI cells λ1 = 1.86 ± 0.080 (Student’s t-test, p = 1.5 × 10−10), λ2 = 0.251 ± 0.008 (Student’s t-test, p = 4.8 × 10−7) at the pipette entrance and λ1 = λ2 = 1.38 ± 0.11 (Student’s t-test, p = 0.003) at cap. Findings from all these analyses are consistent with the hypothesis that spectrin tetramers undergo less remodeling in αIIβI membranes than WT and that remodeling requires making and breaking tetramers. WT membranes are more susceptible to deformation than αIIβI membranes because remodeling can accommodate larger strain.

Discussion

αI-spectrin emerged with the appearance of mammals and apparently coincident with the processes that allow enucleation of erythrocyte precursors and the circulation of mature enucleated erythrocytes. In earlier work, with fewer genomes than are now available, we noted the absence of αI-spectrin from all other vertebrates sequenced at that time (12). Subsequent sequencing of genomes of many more animals confirms this thesis. In particular, mammals are amniotes; the other amniotes are the birds and reptiles. Large numbers of bird and reptile genomes are now available; none of them encode αI-spectrin, although all encode the ancestral α-spectrin, which is retained in mammals as αII-spectrin.

These observations pose several questions about the physiological advantages obtained through the neofunctionalization of αI-spectrin. For example, is it part of, or required for, the process of enucleation? Alternatively (or in addition), is the low-affinity interaction with β-spectrin essential for the physiology of mature enucleated erythrocytes? In our study, we address this by exchanging the low-affinity binding site for β-spectrin in αI-spectrin for the high-affinity binding site in αII-spectrin. The resulting αI/αII chimeras clearly retain the ability first to form dimers with β-spectrin by side-to-side association and secondly to form tetramers by head-to-head association of dimers. Mature enucleated red cells form in the chimeric mice, indicating no indispensable role for αI-spectrin in the process of enucleation.

In broad terms, the overall properties of the chimeric spectrin are not grossly altered. The modification of spectrin does not result in phenotypes associated with anemia in humans. The αIIβI mice are not deficient in spectrin, and membrane loss is small (<10%), which results in increased osmotic fragility, probably a result of reduced remodeling in the αIIβI mice. The change in osmotic fragility is also minor compared to the more substantial increase in fragility seen in hereditary spherocytosis (HS) patients (36). Also, the osmotic fragility curve for the αIIβI mice does not have the shoulder seen for HS samples because the heterogeneity of sphericity of the HS red cells is much broader than that noted in αIIβI mice. Severe forms of hereditary elliptocytosis arise from mutations in αI- and βI-spectrin that inhibit tetramer formation (37,38); elliptocytes were absent in the αIIβI mice. A clinically severe form of elliptocytosis, hereditary pyropoikilocytosis (HPP), arises from mutations at the self-association site that markedly weakens spectrin dimer self-association and enhances the heat sensitivity of red cells (39,40). The weakened self-association site in HPP causes RBCs to fragment at 45°C compared to 50°C for normal human red cells (40). In marked contrast, red cells of the αIIβI mice show increased thermal stability; shape changes occur at 49.5°C, 0.9°C higher than that noted for WT normal red cells. Additionally, electrophoresis by nondenaturing gels of HPP patient samples shows a shift from spectrin tetramers to dimers (39), whereas αIIβI red cells show the opposite, with a shift to higher oligomers.

As measured by ektacytometry, there is a marked change in membrane deformability of αIIβI red cells; however, the difference in DImax is small, consistent with the relatively minor loss of membrane area. Membrane deformability as reflected by the SS1/2 parameter is 7.6× greater for the αIIβI red cells compared to normal red cells, clearly demonstrating the importance of the strength of dimer self-association to red cell membrane deformability. Distinctly different from the ektacytometry of HS red cells (in which DImax is markedly decreased), that decrease in DImax is much less for red cells of αIIβI mice. However, although the rates of change in DI or SS1/2 for HS and normal human red cells are very similar, the rate of change in DI is significantly less for αIIβI red cells compared to normal red cells at low shear rates 0–10 Pa (41, 42, 43). At low shear stresses <1 Pa, the deformability profiles of αIIβI red cells are consistent with red cell tumbling and swinging, and not tank treading (33,34,44). This is consistent with the images of the deformed red cells in the rheoscope showing the resistance of αIIβI red cells to deformation. This has been previously observed in more rigid cells (33,34) and theoretical models of such behavior (45,46).

The K/μ ratio measured by fluorescence-imaged microdeformation of αIIβI mice red cells was ∼80% less than those from normal WT mice. In computer simulations of erythrocyte membranes, Boal showed K/μ = 2 for sixfold networks of simple harmonic springs (47); similarly, modeling by Hansen et al. (48) revealed that decreasing the connectivity of the network increased K/μ. The simplest interpretation of our K/μ measurements is that αIIβI mice have increased connectivity in the cytoskeletal network, arising from enhanced interaction of spectrin dimers at the self-association site.

Electron microscopy studies of αII-spectrin and αI-spectrin have shown αII-spectrin to be a stiffer rod-like molecule compared to αI-spectrin (49,50). Because the spectrin modification in αIIβI mice is small (1 1/3 repeats of the 20 1/3 repeats), the modified polypeptide structure is largely unchanged, and the flexibility of αI-spectrin is retained. If modeled as a simple harmonic spring network, the spring constant would be essentially same in both the αIIβI and the WT. Therefore, the differences in membrane skeleton μ shear and K area dilation moduli observed between the αIIβI and the WT are best explained by membrane skeleton remodeling (i.e., by making and breaking tetramers) resulting in reduced connectivity in the WT compared to the αIIβI model.

The higher oligomers observed in the αIIβI mice could also contribute to the change in the mechanical properties of the membrane skeleton. The significant difference in the incorporation of αII-spectrin into the membrane clearly indicates that the change in binding strength at the self-association site is the dominant factor in the observed change in mechanical properties of the membrane skeleton in the αIIβI mice.

Almost all the computational and theoretical models of membrane biophysical properties ignore spectrin remodeling coming from breaking and reforming tetramers, and it is often absorbed into the shear modulus terms; this is largely due to the complexity of including this feature in the models. Recent attempts to model red blood cell membranes (51,52) have begun to include this contribution and, while giving improved understanding of red cell properties, the data presented here can be incorporated into theoretical models to refine them further. This will inform future understanding of cell fragmentation and life span in clinical settings, as well as understanding of evolutionary processes underlying the biology of blood circulation.

In relation to the evolution of spectrin gene function, it appears the ancestral α-spectrin underwent duplication at about the time mammals emerged, followed by selective adaptation of each, especially αI-spectrin. Gene pairs may become subfunctionalized, for example, by alterations to expression. In the case of mammalian α-spectrins, αII-spectrin is expressed in the vast majority of cell types other than erythrocytes; in erythrocytes, αI alone carries out the α-spectrin function.

Subfunctionalization is often the precursor to neofunctionalization (53), as functions can subsequently be adapted separately. In the case of αI-spectrin, we argued in earlier work (12) that the rapid make and break of spectrin tetramers in erythrocyte membranes represents a new function. The data presented here extend and bring new, to our knowledge, insight to this concept and demonstrate that the ancestral high-affinity spectrin tetramers cannot provide the erythrocyte plasma membrane with the deformability under shear stress required physiologically. We view the promotion of erythrocyte deformability as a new function of αI-spectrin that was not provided by the ancestral (αII) spectrin; hence, αI-spectrin is neofunctionalized.

Although neofunctionalization was the end point, the simplest path to getting there may have been neutral drift of one of the pair of duplicates after separation of expression (i.e., asymmetric evolution (54)), to the point at which any further reduction of affinity for βI-spectrin impaired red cell survival. The point at which neutral drift resulted in weaker but optimal affinity of αI-spectrin for βI-spectrin represented the point of neofunctionalization. Once this point had been reached in an early mammal, it appears to have been strongly favored in subsequent evolution; every amino acid in αI-spectrin at the interface with βI-spectrin (PDB: 3LBX) has been conserved since the last common ancestor of humans and platypus, around 180 million years ago.

Conclusions

In conclusion, our findings reveal that spectrin tetramers are dynamic at the self-association site in intact red blood cells and that remodeling of the membrane skeleton is an essential component of the normal mechanical properties of red blood cells. Mammalian erythrocytes have a form of spectrin optimized for rapid make and break of tetramers and cannot tolerate either higher- or lower-affinity spectrin tetramers for normal biophysical function.

Author contributions

J.H., X.A., W.G., A.B., and N.M. designed research. J.H., X.G., E.G., J.P., and L.B. performed research. J.H., L.B., W.G., A.B., C.D.H., and N.M. analyzed data. J.H., C.D.H., W.G., A.B., and N.M. wrote the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases grant DK32094.

Editor: Vivek Shenoy.

Footnotes

Supporting material can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpj.2021.07.027.

Supporting material

References

- 1.Mohandas N., Gallagher P.G. Red cell membrane: past, present, and future. Blood. 2008;112:3939–3948. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-07-161166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burton N.M., Bruce L.J. Modelling the structure of the red cell membrane. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2011;89:200–215. doi: 10.1139/o10-154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bennett V., Baines A.J. Spectrin and ankyrin-based pathways: metazoan inventions for integrating cells into tissues. Physiol. Rev. 2001;81:1353–1392. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2001.81.3.1353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lux S.E., IV Anatomy of the red cell membrane skeleton: unanswered questions. Blood. 2016;127:187–199. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-12-512772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.An X., Lecomte M.C., Gratzer W. Shear-response of the spectrin dimer-tetramer equilibrium in the red blood cell membrane. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:31796–31800. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204567200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Speicher D.W., Davis G., Marchesi V.T. Structure of human erythrocyte spectrin. II. The sequence of the alpha-I domain. J. Biol. Chem. 1983;258:14938–14947. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yan Y., Winograd E., Branton D. Crystal structure of the repetitive segments of spectrin. Science. 1993;262:2027–2030. doi: 10.1126/science.8266097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ursitti J.A., Kotula L., Speicher D.W. Mapping the human erythrocyte β-spectrin dimer initiation site using recombinant peptides and correlation of its phasing with the α-actinin dimer site. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:6636–6644. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.12.6636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Viel A., Gee M.S., Branton D. Motifs involved in interchain binding at the tail-end of spectrin. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1998;1384:396–404. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4838(98)00036-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hill S.A., Kwa L.G., Clarke J. Mechanism of assembly of the non-covalent spectrin tetramerization domain from intrinsically disordered partners. J. Mol. Biol. 2014;426:21–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2013.08.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bignone P.A., Baines A.J. Spectrin alpha II and beta II isoforms interact with high affinity at the tetramerization site. Biochem. J. 2003;374:613–624. doi: 10.1042/BJ20030507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Salomao M., An X., Baines A.J. Mammalian alpha I-spectrin is a neofunctionalized polypeptide adapted to small highly deformable erythrocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:643–648. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507661103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shahbakhti F., Gratzer W.B. Analysis of the self-association of human red cell spectrin. Biochemistry. 1986;25:5969–5975. doi: 10.1021/bi00368a020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Groner W., Mohandas N., Bessis M. New optical technique for measuring erythrocyte deformability with the ektacytometer. Clin. Chem. 1980;26:1435–1442. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stadnick H., Onell R., Holovati J.L. Eadie-Hofstee analysis of red blood cell deformability. Clin. Hemorheol. Microcirc. 2011;47:229–239. doi: 10.3233/CH-2010-1384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baskurt O.K., Hardeman M.R., Meiselman H.J. Parameterization of red blood cell elongation index--shear stress curves obtained by ektacytometry. Scand. J. Clin. Lab. Invest. 2009;69:777–788. doi: 10.3109/00365510903266069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goldsmith H.L., Marlow J. Flow behaviour of erythrocytes - I. Rotation and deformation in dilute suspensions. Proc. R. Soc. London. Ser. B. Biol. Sci. 1972;182:351–384. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Parpart A.K., Lorenz P.B., Chase A.M. The osmotic resistance (fragility) of human red cells. J. Clin. Invest. 1947;26:636–640. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tomaselli M.B., John K.M., Lux S.E. Elliptical erythrocyte membrane skeletons and heat-sensitive spectrin in hereditary elliptocytosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1981;78:1911–1915. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.3.1911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bessis M. Springer Berlin Heidelberg; Berlin, Germany: 1977. Blood Smears Reinterpreted. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Discher D.E., Mohandas N., Evans E.A. Molecular maps of red cell deformation: hidden elasticity and in situ connectivity. Science. 1994;266:1032–1035. doi: 10.1126/science.7973655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Robledo R.F., Ciciotte S.L., Peters L.L. Targeted deletion of alpha-adducin results in absent beta- and gamma-adducin, compensated hemolytic anemia, and lethal hydrocephalus in mice. Blood. 2008;112:4298–4307. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-05-156000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Discher D.E., Mohandas N. Kinematics of red cell aspiration by fluorescence-imaged microdeformation. Biophys. J. 1996;71:1680–1694. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79424-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schneider C.A., Rasband W.S., Eliceiri K.W. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat. Methods. 2012;9:671–675. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Raabe B.M., Artwohl J.E., Fortman J.D. Effects of weekly blood collection in C57BL/6 mice. J. Am. Assoc. Lab. Anim. Sci. 2011;50:680–685. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gallagher P.G. Red cell membrane disorders. Hematology Am. Soc. Hematol. Educ. Program. 2005;2005:13–18. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2005.1.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Katnik C., Waugh R. Electric fields induce reversible changes in the surface to volume ratio of micropipette-aspirated erythrocytes. Biophys. J. 1990;57:865–875. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(90)82606-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Katnik C., Waugh R. Alterations of the apparent area expansivity modulus of red blood cell membrane by electric fields. Biophys. J. 1990;57:877–882. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(90)82607-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Danon D. A rapid micro method for recording red cell osmotic fragility by continuous decrease of salt concentration. J. Clin. Pathol. 1963;16:377–382. doi: 10.1136/jcp.16.4.377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nagasawa T., Kojima S., Kimura E. Coil planet centrifugal and capillary tube centrifugal analysis of factors regulating erythrocyte osmotic fragility and deformability. Jpn. J. Physiol. 1982;32:25–33. doi: 10.2170/jjphysiol.32.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ungewickell E., Gratzer W. Self-association of human spectrin. A thermodynamic and kinetic study. Eur. J. Biochem. 1978;88:379–385. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1978.tb12459.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bessis M., Mohandas N. Red cell structure, shapes and deformability. Br. J. Haematol. 1975;31:5–10. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dupire J., Socol M., Viallat A. Full dynamics of a red blood cell in shear flow. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:20808–20813. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1210236109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Simmonds M.J., Meiselman H.J. Prediction of the level and duration of shear stress exposure that induces subhemolytic damage to erythrocytes. Biorheology. 2016;53:237–249. doi: 10.3233/BIR-16120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Discher D.E., Boal D.H., Boey S.K. Simulations of the erythrocyte cytoskeleton at large deformation. II. Micropipette aspiration. Biophys. J. 1998;75:1584–1597. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(98)74076-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chilcote R.R., Le Beau M.M., Rowley J.D. Association of red cell spherocytosis with deletion of the short arm of chromosome 8. Blood. 1987;69:156–159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Coetzer T., Zail S. Spectrin tetramer-dimer equilibrium in hereditary elliptocytosis. Blood. 1982;59:900–905. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Eber S., Lux S.E. Hereditary spherocytosis--defects in proteins that connect the membrane skeleton to the lipid bilayer. Semin. Hematol. 2004;41:118–141. doi: 10.1053/j.seminhematol.2004.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu S.C., Palek J., Castleberry R.P. Altered spectrin dimer-dimer association and instability of erythrocyte membrane skeletons in hereditary pyropoikilocytosis. J. Clin. Invest. 1981;68:597–605. doi: 10.1172/JCI110293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zarkowsky H.S., Mohandas N., Shohet S.B. A congenital haemolytic anaemia with thermal sensitivity of the erythrocyte membrane. Br. J. Haematol. 1975;29:537–543. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1975.tb02740.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chasis J.A., Agre P., Mohandas N. Decreased membrane mechanical stability and in vivo loss of surface area reflect spectrin deficiencies in hereditary spherocytosis. J. Clin. Invest. 1988;82:617–623. doi: 10.1172/JCI113640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cynober T., Mohandas N., Tchernia G. Red cell abnormalities in hereditary spherocytosis: relevance to diagnosis and understanding of the variable expression of clinical severity. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 1996;128:259–269. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2143(96)90027-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Renoux C., Faivre M., Connes P. Impact of surface-area-to-volume ratio, internal viscosity and membrane viscoelasticity on red blood cell deformability measured in isotonic condition. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:6771. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-43200-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Abkarian M., Faivre M., Viallat A. Swinging of red blood cells under shear flow. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2007;98:188302. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.98.188302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Skotheim J.M., Secomb T.W. Red blood cells and other nonspherical capsules in shear flow: oscillatory dynamics and the tank-treading-to-tumbling transition. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2007;98:078301. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.98.078301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sui Y., Low H.T., Roy P. Tank-treading, swinging, and tumbling of liquid-filled elastic capsules in shear flow. Phys. Rev. E Stat. Nonlin. Soft Matter Phys. 2008;77:016310. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.77.016310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Boal D. First Edition. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, UK: 2002. Mechanics of the Cell. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hansen J.C., Skalak R., Hoger A. Influence of network topology on the elasticity of the red blood cell membrane skeleton. Biophys. J. 1997;72:2369–2381. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78882-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Begg G.E., Morris M.B., Ralston G.B. Comparison of the salt-dependent self-association of brain and erythroid spectrin. Biochemistry. 1997;36:6977–6985. doi: 10.1021/bi970186n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Harris A.S., Green L.A., Morrow J.S. Mechanism of cytoskeletal regulation (I): functional differences correlate with antigenic dissimilarity in human brain and erythrocyte spectrin. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1985;830:147–158. doi: 10.1016/0167-4838(85)90022-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fai T.G., Leo-Macias A., Peskin C.S. Image-based model of the spectrin cytoskeleton for red blood cell simulation. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2017;13:e1005790. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Li H., Yang J., Karniadakis G.E. Cytoskeleton remodeling induces membrane stiffness and stability changes of maturing reticulocytes. Biophys. J. 2018;114:2014–2023. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2018.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.He X., Zhang J. Rapid subfunctionalization accompanied by prolonged and substantial neofunctionalization in duplicate gene evolution. Genetics. 2005;169:1157–1164. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.037051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Holland P.W.H., Marlétaz F., Paps J. New genes from old: asymmetric divergence of gene duplicates and the evolution of development. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2017;372:20150480. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2015.0480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.