Abstract

ATPase inhibitory factor 1 (IF1) is a mitochondrial regulatory protein that blocks ATP hydrolysis of F1-ATPase, by inserting its N-terminus into the rotor–stator interface of F1-ATPase. Although previous studies have proposed a two-step model for IF1-mediated inhibition, the underlying molecular mechanism remains unclear. Here, we analysed the kinetics of IF1-mediated inhibition under a wide range of [ATP]s and [IF1]s, using bovine mitochondrial IF1 and F1-ATPase. Typical hyperbolic curves of inhibition rates with [IF1]s were observed at all [ATP]s tested, suggesting a two-step mechanism: the initial association of IF1 to F1-ATPase and the locking process, where IF1 blocks rotation by inserting its N-terminus. The initial association was dependent on ATP. Considering two principal rotation dwells, binding dwell and catalytic dwell, in F1-ATPase, this result means that IF1 associates with F1-ATPase in the catalytic-waiting state. In contrast, the isomerization process to the locking state was almost independent of ATP, suggesting that it is also independent of the F1-ATPase state. Further, we investigated the role of Glu30 or Tyr33 of IF1 in the two-step mechanism. Kinetic analysis showed that Glu30 is involved in the isomerization, whereas Tyr33 contributes to the initial association. Based on these findings, we propose an IF1-mediated inhibition scheme.

Keywords: ATPase inhibitory factor 1 (IF1), ATP synthase, enzyme kinetics, F1-ATPase, rotary molecular motor

Graphical Abstract

ATP synthase, also termed as FoF1-ATP synthase (FoF1), is ubiquitously found in bacterial plasma membranes, chloroplast thylakoid membranes and mitochondrial inner membranes (1–5). It catalyzes ATP synthesis from ADP and inorganic phosphate (Pi) using proton motive force (pmf) across membranes. FoF1-ATP synthase consists of two reversible rotary motors, Fo and F1. Fo, the membrane-embedded portion of ATP synthase, conducts proton translocation across the membrane, whereas F1, the water-soluble portion, contains the catalytic centre domain for ATP synthesis. In the FoF1 complex, Fo and F1 are connected by the common rotary shaft and the peripheral stalk, enabling the interconversion of pmf and the chemical potential of ATP. Under physiological conditions with sufficiently high pmf level, Fo reverses the rotation of F1, inducing ATP synthesis. When pmf is low or diminished, F1 hydrolyzes ATP to rotate Fo in the opposite direction, resulting in active proton pumping to form pmf.

F1 hydrolyzes ATP to ADP and Pi when isolated from Fo (6, 7). α3β3γ is the minimum component of a rotary molecular motor. Three α subunits and three β subunits are arranged alternately to form the α3β3 stator ring, of which the central rotary shaft, the γ subunit, is inserted into the central cavity (8, 9). The catalytic reaction centres are located on the αβ interface, mainly on the β subunit. During ATP hydrolysis, the γ subunit of F1 rotates against the α3β3-ring in anticlockwise direction when viewed from the Fo side (5). Crystal structures of bovine mitochondrial F1-ATPase (bMF1) showed asymmetric features of nucleotide occupancy and the conformational states of the three β subunits (8, 10–12). One β subunit, designated βTP, preferentially binds to an ATP analogue, AMP-PNP, whereas another one, βDP, binds to ADP and Pi or Pi analogues, representing the catalytically active state. The third one, βE, has no nucleotides, although some crystal structures show that it has phosphate (9), thiophosphate (11) or sulfate ions (12), suggesting that βE represents the phosphate releasing state (13). Both βTP and βDP adopt a closed conformational state in which the C-terminal domain swings toward the γ subunit, wrapping the bound nucleotide, whereas βE assumes an open conformation.

The coupling reaction scheme for the rotation and catalysis of bMF1 was recently studied in a single-molecule rotation study (14). Similar to the reaction scheme for thermophilic F1 (TF1), bMF1 makes rotation with 120° steps, each resolved into 80° and 40° substeps. The 80° and 40° substeps are triggered by ATP binding and hydrolysis, respectively. Therefore, the dwelling states before the 80° and 40° substeps are referred to as ‘binding dwell’ and ‘catalytic dwell’, respectively. In addition, bMF1 exhibits a short transient pause between the binding dwell and the catalytic dwell. The reaction step involved in the short transient pause remains to be identified. Previous studies have shown that the crystal structures of bMF1 in the ground state or relevant states correspond to the catalytic dwell in the rotation assay (14–16).

There are diverse mechanisms for the suppression of ATP hydrolysis by F1, which is generally detrimental to cells (17–19). The self-inhibition of F1, termed ADP inhibition, is the most universal mechanism for F1 inhibition (14, 20, 21). Inhibitory factor 1 (IF1) of mitochondrial F1 inhibits unfavourable ATPase. Under inhibitory conditions, IF1 associates with F1 to block ATP hydrolysis by inserting its N-terminal region into FoF1-ATP synthase, which results in mechanical blockage of rotation and catalysis. Bovine mitochondrial IF1 is composed of 84 amino acid residues. IF1 inhibits the function of FoF1-ATP synthase under hydrolytic condition to prevent wasteful consumption of ATP. Thus, it is an unidirectional inhibitor of FoF1-ATP synthase (22, 23), although several reports have suggested that IF1 also has an inhibitory effect under synthesized condition (24, 25). Among the 84 residues in bovine IF1, the N-terminus is responsible for the inhibition of FoF1-ATP synthase, forming a long α-helix when bound to F1. When isolated from F1, the N-terminus of IF1 is intrinsically disordered (26). Native IF1 forms a homodimer associating at the C-terminal region (27, 28). Deletion of C-terminus residues 61–84 produces a stable monomeric form of IF1 without the loss of inhibition activity (28, 29). Thus, the C-terminus deleted form of IF1 (termed hereafter) provides a simple platform for biochemical and structural analyses of IF1 (28, 30, 31). Biochemical assay showed that the fusion of green fluorescent protein (GFP) and 6 histidine tag (His-tag) to the C-terminus in (GFPHis) has little impact on its inhibitory capacity (30).

The first crystal structure of the complex of bMF1 and showed that the N-terminal helix of was deeply buried in the αDP/βDP interface in its locked state (28). Following this, the crystal structure of the bMF1-()3 complex was resolved, revealing that each of the three α/β interfaces was occupied with IF1 (31). Each IF1 bound to the α/β interface differed in conformation: IF1 at the αDP/βDP interface showed the most folded state, as found in the first bMF1-IF1 structure; IF1 at αTP/βTP showed partially folded α-helix with unfolded N-terminal region; and IF1 at αE/βE was largely disordered. These findings suggest progressive conformational isomerization of IF1 from a disordered state to the α-helical state, accompanying the conformational transition of the α/β pair from αE/βE to αDP/βDP. As the conformational transition of the α/β pair is tightly coupled with γ rotation, the progressive conformational isomerization model inevitably assumes that IF inhibition accompanies γ rotation (Fig. 1A). Comprehensive studies of mutagenesis based on the crystal structure revealed that Glu30 and Tyr33 of IF1 are particularly critical for IF1 inhibition. Glu30 and Tyr33 form a salt bridge and hydrophobic interaction with a residue of the β subunit, respectively. Ala substitution causes a loss of the inhibitory activity of IF1 (30). However, the roles of these residues in the proposed progressive conformational change model remain to be elucidated.

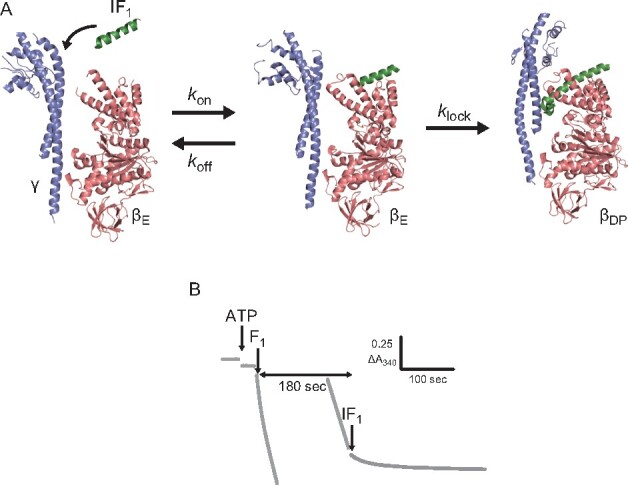

Fig. 1.

Experimental concept and procedure. (A) Schematic image of inhibition by IF1. IF1 loosely associates with the αE and βE subunits. Then, IF1 is deeply inserted into the αDPβDP interface (PDB: 2JDI and 4TT3). The initial association and the following isomerization are represented by three rate constants, , and . (B) Time course of 340 nm NADH absorbance at 1 mM ATP and 1 μM –60. At 180 s after F1 addition, –60 was added to the reaction mixture and ATPase activity decreased. To see this figure in colour, go online.

Biochemical studies have revealed that IF1 inhibition requires catalytic turnover of F1; in the absence of ATP, IF1 only shows slow and partial inhibition of F1 (32, 33). In the presence of ATP, IF1 shows rapid inhibition during turnover (34). Kinetic analyses showed that the rate constant of IF1-mediated inhibition increases with [ATP], although some complex behaviours of IF1 inhibition were observed, such as a decrease in the inhibition rate at the mM range of [ATP] (32, 33, 35). The correlation of IF1 inhibition with occupancy of the catalytic site was also studied (32, 33, 36). Based on kinetic analyses, an ATP-dependent two-step model has been proposed for IF1-mediated inhibition (35, 37, 38). The two-step model suggests that the rate constant of IF1-mediated inhibition should increase with [IF1], reaching an ATP-dependent plateau. However, comprehensive kinetic analysis covering a wide range of IF1 and ATP concentrations to confirm the expected hyperbolic curves has not been performed yet.

In this study, we studied the kinetics of bMF1 inhibition by bovine mitochondrial IF1 with an NADH-coupled ATP-regenerating system, using a wide range of [ATP] from 100 nM to 1 mM with [IF1] from 0.05 to 40 µM. The resultant rate constant of IF1-mediated inhibition showed typical hyperbolic curves for [IF1] at each [ATP], consistent with the two-step model. We then investigated the IF1 mutants IF1(E30A) and IF1(Y33A) to study the effects of Glu30 and Tyr33, respectively, on the kinetics of IF1 inhibition. Based on the results as well as the established reaction scheme for catalysis and rotation of bMF1 (14), we propose an IF1 inhibition scheme.

Materials and Methods

Construct and purification of IF1

An expression plasmid encoding residues 1–60 of bovine IF1 was constructed as follows: His-tag and TEV site were fused to the N-terminal region, and the linker and mScarlet sequences were fused to the C-terminal region. The resulting artificially synthesized construct was introduced into the pRSET-B plasmid, which encoded the protein mScarlet (hereafter referred to as wild-type or ).

was generated by deleting the linker and mScarlet sequences from the wild-type plasmid. The single-point amino acid mutants, E30A and Y33A, were introduced into the wild-type plasmid. The sequence encoding or a mutation was amplified by PCR. After gel electrophoresis and purification, the product was digested with two restriction enzymes and cloned into the vector wild-type plasmid, digested with the same restriction enzymes. The sequences of the recombinant plasmids for IF1 were confirmed by Fasmac sequencing service (Fasmac, Japan).

Cells of Escherichia coli C43 were transformed with the constructed plasmids and grown in LB medium containing 100 µg/mL carbenicillin at 37°C for 4 h as a preculture. The culture medium was then transferred to SB medium containing 100 µg/mL carbenicillin at 37°C. When the absorbance of the culture was 0.6 at 600 nm (for ∼4 h), isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) was added at a final concentration of 1 mM to induce protein expression. After 24 h of growth at 20°C, cells were harvested by centrifugation (7000×g, 8 min, 4°C). Subsequent procedures were performed at 4°C, except for the gel-filtration process. The harvested cells were suspended in buffer A [50 mM KPi (pH 7.5), 200 mM KCl, 10% Glycerol and 25 mM Imidazole], disrupted by an ultrasound disintegrator and subjected to ultracentrifugation (81,000×g, 20 min). The supernatant was applied to Ni-Sepharose FF resin (GE Healthcare) equilibrated in buffer A. After binding IF1 to the resin, it was washed with 10 volumes of buffer A. IF1 was eluted with elution buffer [50 mM KPi (pH 7.5), 200 mM KCl, 10% glycerol and 500 mM imidazole].

To remove His-tag, TEV protease was used. The eluted fractions containing the proteins were concentrated with a centrifugal concentrator (3 kDa for and 10 kDa for wild-type and mutants; Centricon50; Millipore Corp.). The concentrated fractions were diluted 20-fold with TEV treatment buffer [20 mM KPi (pH 8.0), 50 mM NaCl 0.04% 2-mercaptoethanol, and 0.1 mg/mL TEV protease]. After treatment for 16 h at 4°C, the solution was concentrated with a centrifugal concentrator and diluted 30-fold with buffer A. The resultant solution was applied to a Ni-Sepharose FF resin. The flow-through and wash fractions were concentrated with a centrifugal concentrator after adding DTT at a final concentration of 5 mM. The resulting samples were further purified by passing through a gel-filtration column (Superdex 75 for , and Superdex 200 for wild-type and mutants; GE Healthcare) equilibrated with Gel-filtration buffer [20 mM HEPES-KOH (pH7.5), 100 mM KCl and 10% glycerol]. If necessary, the fractions were concentrated with a centrifugal concentrator. The concentration of IF1 was determined based on the absorbance at 280 nm. The purified samples were flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C before use. Their molecular masses were verified by SDS-PAGE (sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis) analysis (Supplementary Fig. S1). Further confirmation of the molecular masses for wild-type and was performed by MALDI‐TOF/TOF mass spectrometry (Genomine. Inc., Korea) (Supplementary Table S1).

Construct and purification of bMF1

bMF1 was prepared as previously described (14) with slight modifications. We removed ATP from buffers A, B and gel-filtration buffer for measurements of ATPase activity at low ATP conditions because the carryover ATP from the purified bMF1 sample to the cuvette was not negligible under these conditions. The ATPase activity of bMF1 purified without ATP was identical to that purified with ATP.

Biochemical assay with NADH-coupled ATP-regenerating system

As previously reported (14), the ATPase activity of bMF1 was measured using a spectrometer at 25°C in HEPES-KOH (pH 7.5) containing KCl, MgCl2 and an ATP-regenerating system supplemented with NADH and lactate dehydrogenase. The ATPase reaction was initiated by adding purified bMF1.

IF1 was added 180 s after the addition of bMF1 to avoid ADP inhibition. The change in NADH absorbance was monitored for over 10 min. All data points were measured at least in triplicate. The apparent rate constants for IF1 inhibition () were measured from the exponential decay of ATPase activity after IF1 addition, using the following equation:

| (1) |

where and are the absorbances at time points t and 0 after IF1 addition, respectively, and and are the initial and final rates of reaction, respectively. For precise fitting, we have fitted the time course 60 s after IF1 injection to remove noise caused by solution injection. Examples of and , estimated in Fig. 2B at 1 mM ATP, were shown in Supplementary Fig. S6.

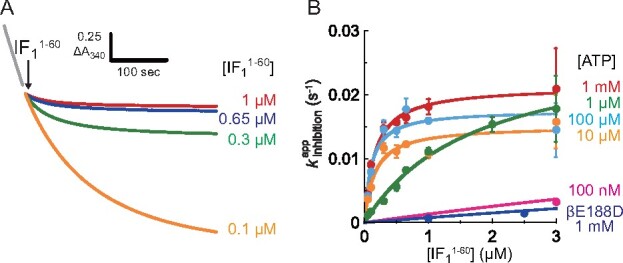

Fig. 2.

Kinetic analysis of IF1 inhibition in bMF1. (A) Time course of IF1 inhibition at 1 mM ATP. Colour represents different concentrations; (Red) 1 μM, (Blue) 0.65 μM, (Green) 0.3 μM, and (Orange) 0.1 μM. The final concentration of bMF1 was 10 nM. (B) Determined plotted against []s. The mean value and SD for each data point in (B) are shown with circles and error bars, respectively (n = 3 for each measurement). Solid line represents the fitting curve of Eq. 2. For wider [] range of wild-type bMF1 at 100 nM ATP and bMF1(βE188D) at 1 mM ATP, see Supplementary Fig. S4. To see this figure in colour, go online.

Modelling the two-step reaction of IF1 inhibition

The kinetic scheme is as follows:

where is the rate constant for IF1 binding to F1, is the rate constant for IF1 release from F1, and is the rate constant for isomerization to the locked state. F1 and are active and is inactive. In the first step, IF1 loosely binds to F1, forming an intermediate state. Following this, IF1 is irreversibly locked, forming a dead-end complex. For derivation of , see the Supplemental text.

Results

Preparation of IF1protein

C-terminal residues of in bovine IF1 were fused with mScarlet, a bright monomeric red fluorescent protein with a short linker sequence, to enhance its expression in E. coli, as previously described (30). The fusion IF1 is hereafter referred to as wild-type or for simplicity, unless mentioned otherwise. For comparison, we also purified lacking the linker sequence and the mScarlet domain. For the preparation of (E30A) or (Y33A), a single point mutation was introduced into the wild-type plasmid. For purification with an Ni-Sepharose column, the His-tag and TEV recognition sequences were fused to the N-terminal region of the IF1 proteins. After collecting the eluted fractions from the Ni-Sepharose column, the His-tag was cleaved with TEV-protease. The resultant products were identified by SDS-PAGE analysis (Supplementary Fig. S1) and mass spectroscopy (Supplementary Table S1).

Time course of IF1-mediated inhibition

ATP hydrolysis activity of bMF1 was monitored using an ATP regenerating system. The decay of NADH absorbance at 340 nm represents ATP hydrolysis leading to NADH oxidation. Upon injection, bMF1 initially showed rapid catalysis, followed by slow deceleration to reach steady-state catalysis (Fig. 1B). The slow auto-inactivation is a typical feature of ADP inhibition. Under the present conditions, bMF1 activity almost reached steady state within 180 s (Supplementary Fig. S2). Subsequently, IF1 was injected at 180 s after F1 injection. Since the time constant for ADP inhibition at 1 µM ATP was longer than 400 s, ADP inhibition did not reach an equilibrium state at the time of IF1 injection. However, additional analysis of IF1 inhibition including ADP inhibition (Supplementary text and Supplementary Fig. S3) revealed that it has little impact on IF1 kinetics, probably due to the slow and modest suppression at 1 µM ATP.

Fig. 2A shows the typical time courses of IF1-mediated inhibition at 1 mM [ATP]. Immediately after the injection of , ATPase activity decreased, reaching almost zero activity. The time course of IF1-mediated inhibition was well fitted with an exponential function (Eq. 1), giving the apparent rate constant of the inhibition, . The inhibition rate increased with [], reaching a plateau when [] was over 0.65 µM. We also measured the time courses of IF1-mediated inhibition to determine at all [ATP]s ranging from 100 nM to 1 mM. In Fig. 2B and Supplementary Fig. S4, data points of are plotted against [] at all [ATP]s. At a given [ATP], always increases with [] and reaches a plateau, following a hyperbolic curve. Further, we tested the inhibitory capacity of a monomer IF1 without mScarlet () and found that the result was almost identical to that of wild-type (Supplementary Fig. S5), suggesting that mScarlet in the C-terminal region did not affect the kinetics of IF1-mediated inhibition. It should be noted that previous biochemical assay based on mutagenesis (30) showed monotonous enhancement of , whereas clear hyperbolic curve was observed in our assay. Such an apparent difference is attributable to low [IF1] employed in the assay (30), which enabled to visualize the limited region of the hyperbolic curve in the two-step inhibition mechanism. Another possible reason for this discrepancy is the difference in experimental conditions: including pH, temperature and chemicals.

The observed hyperbolic curves suggest a two-step model, where IF1 reversibly associates with F1, and the resulting complex isomerizes to the final locked state. Thus, we assume the following reaction scheme for IF1-mediated inhibition:

where, represents the catalytically locked state of the complex. and represent the rate constants of association and dissociation, respectively. is the rate constant of isomerization to the locked state. This scheme calculates the apparent rate constant of IF1 inhibition, , as follows:

| (2) |

| (3) |

The experimentally obtained data points at each [ATP] were well fitted with Eq. 2, giving and .

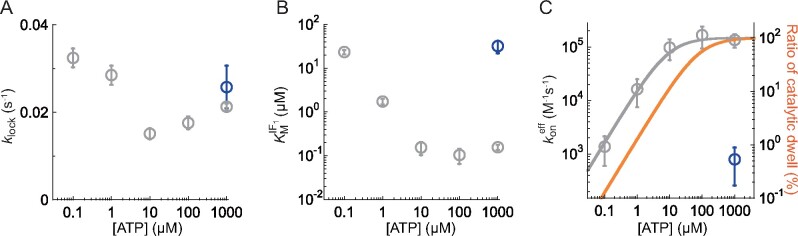

[ATP] dependence of

Fig. 3A shows the plot of against [ATP]s. Although not well constant, was around 0.02 s−1 irrespective of [ATP]; this value is almost consistent with that estimated from previous studies (39, 40). is evidently lower than the catalytic turnover rate, 1–200 s−1, indicating that IF1 transforms into the inhibitory locking state during the rotation of the γ subunit. Fig. 3B shows the plot of against [ATP]. was determined to be in the sub-µM to µM range, consistent with that of previous biochemical studies with isolated F1 and sub-mitochondrial particles (32–35, 39). reveals a clear [ATP] dependence, decreasing from 27 to 0.1 µM when [ATP] is over 10 µM. Considering constant over [ATP], this means that the rate constant of IF1 association to F1 follows a hyperbolic increment with [ATP].

Fig 3.

Fitted parameters derived fromFig. 2Band Supplementary Fig. S4. (A) and (B) . In (A) and (B), the circles and error bars in each data point represent the fitted parameter and fitting error determined in Fig. 2B and Supplementary Fig. S4. (C) The effective binding constant . The gray line represents the fitting curve of Eq. 5 and the orange line represents the duty ratio of catalytic dwell against overall reaction time. The circles and error bars in each data point represent the mean value and the SD calculated from Fig. 3A and B. In Fig. 3A–C, grey and blue points represent the results for bMF1(wild-type) at 0.1–1000 μM and bMF1(βE188D) at 1 mM ATP, respectively. To see this figure in colour, go online.

Here, we define the effective rate constant of IF1 association to F1 as follows:

| (4) |

Fig. 3C shows the plot of against [ATP]. As expected, shows a typical hyperbolic saturation curve. Considering that IF1 cannot bind ATP by itself, it is reasonable to attribute the ATP binding to F1, c.f. IF1 is predominantly associated with F1 in the post-ATP-bound state. In light of the reaction scheme for rotation and catalysis, this means that IF1 is not associated with F1 in the binding dwell, but it preferentially associates with F1 in the catalytic dwell.

With the assumption that IF1 preferentially binds to F1 in the catalytic dwell, we tested the mutant bMF1(βE188D). Previous studies have shown that Glu188 of bMF1 or the corresponding glutamic residues of other F1s are the most critical residues for catalysis (8, 16, 41). Mutagenic substitution of Glu188 with aspartic acid largely retarded bMF1 catalysis, lengthening the catalytic dwell by 400 times (14). We investigated IF1-mediated inhibition of bMF1(βE188D) at 1 mM [ATP] (Supplementary Fig. S7). Contrary to the expectation, bMF1(βE188D) did not exhibit enhanced IF1 inhibition rate compared with wild-type bMF1 at saturating [ATP]s. The hyperbolic inhibition curve of bMF1(βE188D) at 1 mM [ATP] was similar to that of wild-type bMF1 at 100 nM [ATP], where the binding dwell is dominant (Fig. 2B and Supplementary Fig. S4). Considering that F1 mediates two reactions through the catalytic dwell, hydrolysis and presumably inorganic phosphate release, the catalytic state and the conformation of bMF1(βE188D) at the catalytic dwell maybe different from that of the wild-type in some aspects.

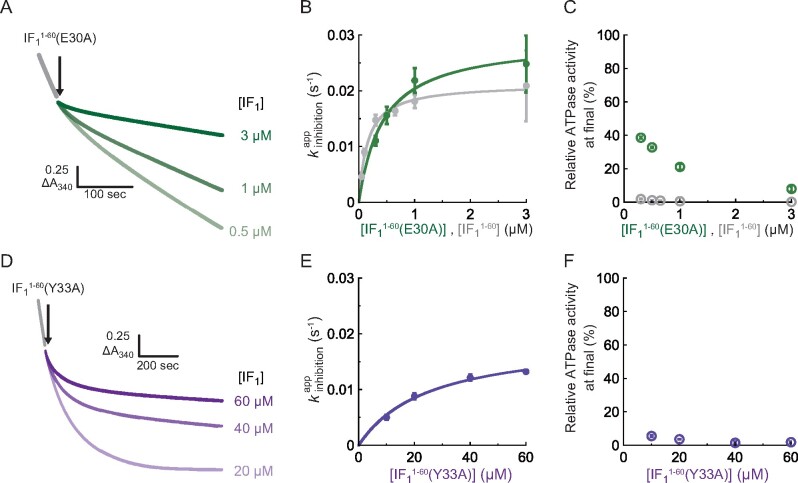

Mutation of Glu30 and Tyr33

A previous comprehensive mutagenetic study identified E30 and Y33 as the most critical residues for the inhibitory function of IF1 (31). Although the mutants created by substituting these residues with alanine suppressed the activity down to an undetectable level (30), we reinvestigated these mutants, (E30A) and (Y33A), in our experimental setup.

Experiments were conducted using 1 mM [ATP]. Fig. 4A shows the time course of its inhibition by (E30A) at 0.5, 1 and 3 µM concentrations, which are similar to the range for wild-type . ATPase activity showed slight decay and reached steady state with some activity remaining. Compared to wild type, where the complete inhibition was observed (Fig. 2A), the inhibition by (E30A) was not irreversible. Based on the exponential fitting of the time courses in Eq. 1, of (E30A) was determined (Fig. 4B, green) and found to be quite similar to that of wild-type (Fig. 4B, grey) at each [(E30A)]. The resultant and were almost consistent with those for the wild-type (Supplementary Table S2). These results show that the E30A mutant also follows a two-step mechanism for inhibition. However, (E30A)-mediated inhibition is evidently less efficient, as seen in the partial inhibition of ATPase activity. Fig. 4C shows the final ATPase activity observed at the end of the measurement (360 s after IF1 injection). While wild-type IF1 suppresses ATPase activity down to almost zero at each [], (E30A) suppresses ATPase activity down to only 20–40% at [(E30A)]s lower than 1 µM. Even at 3 µM [(E30A)], where reached a plateau, a fraction of bMF1 retained its activity.

Fig. 4.

Analysis of (A–C) (E30A) and (D–F) (Y33A) at 1 mM ATP. (A), (D) Time course of IF1 inhibition for (A) (E30A) and (D) (Y33A). The final concentration of bMF1 was 10 nM. (B), (E) Determined plotted against []s. Solid line represents the fitting curve of Eq. 2. (C), (F) Relative ATPase activity at the end of the measurement. The mean value and SD for each data point are shown with circles and error bars, respectively (n = 3 for each measurement). To see this figure in colour, go online.

The Y33A mutant, (Y33A), was also examined at 1 mM ATP. Fig. 4D shows the time course of its inhibition. This mutant required a significantly higher concentration of [(Y33A)], at least 10 µM [(Y33A)], to induce clear inhibition. However, in contrast to the E30A mutant, the Y33A mutant suppressed ATPase activity to almost zero (Fig. 4F). These observations suggest that the Y33A mutant has high inhibitory activity, although the time scale for its association with F1 was significantly longer than that for the wild-type . Fig. 4E shows of (Y33A), which follows a hyperbolic curve consistent with the two-step model of IF1 inhibition. The plateau determined the of (Y33A) to be 0.019 s−1, which is very similar to that of wild-type . The significant difference was observed for , which was 25 µM in case of (Y33A), 160 times higher than that of wild-type (Table S2).

Thus, the effect of the mutations contradicted each other. Although the E30A mutant had normal , it was evidently deficient in locking the catalysis of F1. The Y33A mutant was quite slow for the association with F1 and had lower and higher , although this mutant finally locked the catalysis almost completely.

Discussion

[ATP] dependence of

The present study showed that the effective binding rate ofIF1 to bMF1,, evidently followed an [ATP]-dependent saturation curve (Fig. 3C). As IF1 itself cannot bind ATP, the [ATP] dependence of can be attributed to bMF1. As IF1 inhibition requires catalytic turnover of bMF1, it is reasonable to assume that the [ATP] dependence is the result of the Michaelis–Menten kinetics of ATPase activity. Kinetic analysis of bMF1 rotation (14) shows that F1 principally has two conformational states: binding dwell and catalytic dwell. Here, we neglect the short dwell between the binding dwell and the catalytic dwell because its duration is significantly shorter than those of the other dwells. The duration of the binding dwell is inversely proportional to [ATP], whereas that of the catalytic dwell is constant at approximately 0.3 ms, irrespective of [ATP] (14). Thus, we consider the following two states of F1:

where, represents the rate of the catalytic dwell (∼2100 s−1) and is the rate of ATP binding to bMF1. The simplest assumption to explain the [ATP] dependence of is that IF1 preferentially associates with F1 in the catalytic dwell. Here, we calculate the duty ratio of the catalytic dwell in the overall reaction time () as follows:

| (5) |

where, is defined as from the Michaelis–Menten fitting of the rotation speed, 77 µM (14). Along with Eq. (4) and Eq. (5), we redefine and as follows:

| (6) |

| (7) |

where, is the genuine rate constant of IF1 binding to F1 in the catalytic dwell. In Fig. 3C, the calculated (orange) is plotted with the experimental data points of (gray) after normalization. The experimental data points were fitted to determine and . Since we have not estimated from our experimental data, we simply assume as 0.0017 s−1, which was previously estimated (30). The resultant was determined to be 1.5 × 105 M−1s−1, in good agreement with previous studies that determined in the order of 104–106 M−1s−1 (30, 32, 33, 35). However, was determined to be 9 µM, which was obviously lower than the expected concentration of 77 µM. One of the possible explanations for this is the difference in experimental conditions: the rotation assay that determined to be 77 µM selectively analysed actively rotating particles, whereas this study was based on a solution experiment where the value was averaged over molecules including those in the ADP-inhibited form. However, since the determined from ATPase measurement was 218 µM (14), we do not have convincing interpretations at this moment. Future single-molecule analysis of IF1 inhibition is required to overcome this limitation.

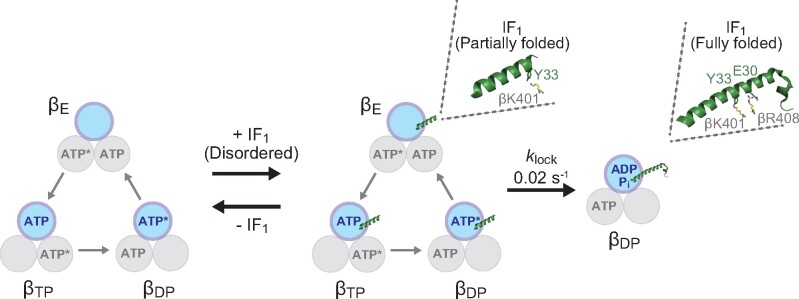

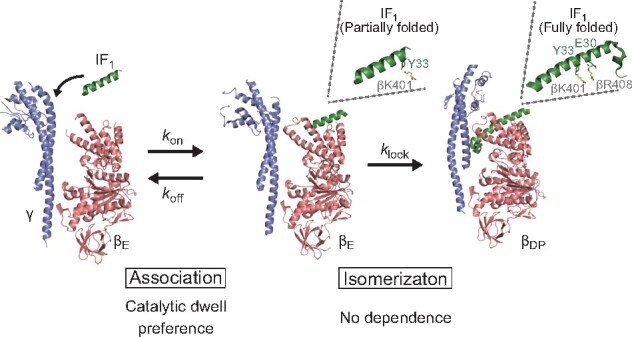

Proposed IF1 inhibition scheme and correlation with crystal structures

The present study observed hyperbolic curves at different [ATP]s that allows us to discuss the IF1 inhibition mechanism based on the rotary catalysis of bMF1. We also carefully examined the mutant IF1s with a mutation at critical points: Glu30 and Tyr33. These mutants significantly affect the IF1 inhibition at different processes. Taking the present results into account, together with those of previous single-molecule analyses (14) and structural studies (31), we propose the following IF1-mediated inhibition mechanism (Fig. 5), where the role of Glu30 and Tyr33 in the two-step inhibition by IF1 was clarified as well as the catalytic state of bMF1. Initially, IF1 weakly associates with F1 in the catalytic dwell. This weakly bound state corresponds to the intermediate state in the two-step model, as represented in Scheme 1, which undergoes reversible association and dissociation. We assume that this state represents IF1 bound to the αEβE site in the crystal structure of the bMF1-()3 complex (31), where only a small part of the N-terminal helix is folded and associates with βE via a few interactions at distal points to the γ subunit. In this state, a large part of the N-terminal helix remains unfolded and IF1 principally does not interfere with γ rotation and catalysis. Tyr33 of IF1 interacts with Lys401 of βE in its crystal structure. The present study showed that Y33A mutation of IF1 slows the association step of IF1, in consistent with the crystal structure. Therefore, it is reasonable that the Y33A mutation largely suppresses the formation of the initial F1-IF1 complex.

Fig. 5.

The possible IF1 inhibition scheme. Each circle represents the catalytic state of the β subunit. The asterisks following “ATP” represent the catalytically active state to undergo hydrolysis of a bound ATP. All nucleotide binding states of bMF1 in this figure represent catalytic dwell, where bMF1 executes cleavage of ATP. To see this figure in colour, go online.

After the formation of the initial F1-IF1 complex, IF1 slowly transforms its conformation to the fully folded state, inserting the N-terminal helix deeply into the αβ interface, as seen in IF1 at the αDPβDP site in its crystal structure. This state completely locks the rotation and catalysis of F1 ( in Scheme 1). In the crystal structure, Glu30 of IF1 forms a salt bridge with Arg408 of βDP or βTP but not with Arg408 of βE, indicating that Glu30 is involved in the isomerization of IF1 to the fully stretched state. Consistent with this, the present study shows that the Ala mutant of Glu30 significantly destabilizes the locked state, without affecting formation of the initial F1-IF1 complex.

Notably, the mean duration for this isomerization from the initial F1-IF1 complex to the final locked state is 50 s (), which is significantly longer than the meantime for rotation (5–1000 ms). This suggests that F1 drives thousands of γ rotation with a hanging IF1. In other words, IF1 almost always fails to isomerize to the locking state in each catalysis or each turn.

However, this contradicts the observation that IF1 preferentially associates with F1 in the catalytic dwell to form an initial complex. The contention that F1 can drive many turns while associated with IF1 indicates that F1 has some affinity to IF1 in any state besides the catalytic dwell. Although we do not have clear explanations for this contradiction, simplification of the reaction scheme may be a possible cause. Nevertheless, the crystal structure suggests that IF1 can have several conformations, and our model assumes only two states, neglecting intermediate states. Another possible reason for the contradiction is that some minor states were neglected through ensemble averaging and curve fitting of the time courses of IF1 inhibition. Considering the intrinsic heterogeneity of the F1 states among molecules, different experimental approaches that can assess molecular heterogeneity are required to resolve this problem and to elucidate the molecular mechanism of IF1-mediated inhibition.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary Data are available at JB Online.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank M. Hara (University of Tokyo) for technical support, Chun-Biu Li (Stockholm University) for data analysis, and all members of the Noji laboratory for their valuable comments.

Funding

This work was supported in part by Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Innovation Areasa (JP18H04817, JP19H05380) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (to H.U.).

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Abbreviations

- bMF1

F1 from bovine mitochondria

- F1

F1-ATPase

- FoF1

FoF1-ATP synthase

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

- His-tag

histidine tag

- HEPES

2-[4-(2-hydroxyethyl)piperazin-1-yl]ethanesulfonic acid

- IF1

ATPase Inhibitory factor 1

- KPi

potassium phosphate buffer

- MALDI-TOF/TOF

Matrix Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization—Time-of-Flight/Time-of-Flight mass spectrometer

- pmf

proton motive force

- SDS-PAGE

sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

- TEV

tobacco etch virus

- TF1

F1 from thermophilic Bacillus PS3.

References

- 1.Walker J.E.E. (2013) The ATP synthase: the understood, the uncertain and the unknown. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 41, 1–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Junge W., Sielaff H., Engelbrecht S. (2009) Torque generation and elastic power transmission in the rotary FoF1-ATPase. Nature 459, 364–370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mukherjee S., Bora R.P., Warshel A. (2015) Torque, chemistry and efficiency in molecular motors: a study of the rotary-chemical coupling in F1-ATPase. Q. Rev. Biophys. 48, 395–403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weber J. (2010) Structural biology: toward the ATP synthase mechanism. Nat. Chem. Biol. 6, 794–795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Noji H., Ueno H., McMillan D.G.G. (2017) Catalytic robustness and torque generation of the F1-ATPase. Biophys. Rev. 9, 103–118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Noji H., Ueno H., Kobayashi R. (2020) Correlation between the numbers of rotation steps in the ATPase and proton-conducting domains of F- and V-ATPases. Biophys. Rev. 12, 303–307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Spetzler D., York J., Daniel D., Fromme R., Lowry D., Frasch W. (2006) Microsecond time scale rotation measurements of single F1-ATPase molecules. Biochemistry 45, 3117–3124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abrahams J.P., Leslie A.G.W., Lutter R., Walker J.E. (1994) Structure at 2.8 Å resolution of F1-ATPase from bovine heart mitochondria. Nature 370, 621–628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kabaleeswaran V., Puri N., Walker J.E., Leslie A.G.W., Mueller D.M. (2006) Novel features of the rotary catalytic mechanism revealed in the structure of yeast F1 ATPase. Embo J. 25, 5433–5442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bowler M.W., Montgomery M.G., Leslie A.G.W., Walker J.E. (2007) Ground state structure of F1-ATPase from bovine heart mitochondria at 1.9 Å resolution. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 14238–14242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bason J.V., Montgomery M.G., Leslie A.G.W., Walker J.E. (2015) How release of phosphate from mammalian F1-ATPase generates a rotary substep. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 112, 6009–6014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Menz R.I., Walker J.E., Leslie A.G.W. (2001) Structure of bovine mitochondrial F1-ATPase with nucleotide bound to all three catalytic sites: implications for the mechanism of rotary catalysis. Cell 106, 331–341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Okazaki K.-i., Hummer G. (2013) Phosphate release coupled to rotary motion of F1-ATPase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 110, 16468–16473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kobayashi R., Ueno H., Li C.-B.B., Noji H. (2020) Rotary catalysis of bovine mitochondrial F1 - ATPase studied by single-molecule experiments. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 117, 1447–1456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Okuno D., Fujisawa R., Iino R., Hirono-Hara Y., Imamura H., Noji H. (2008) Correlation between the conformational states of F1-ATPase as determined from its crystal structure and single-molecule rotation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105, 20722–20727 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shimabukuro K., Yasuda R., Muneyuki E., Hara K.Y., Kinosita K., Yoshida M. (2003) Catalysis and rotation of F1 motor: cleavage of ATP at the catalytic site occurs in 1 ms before 40° substep rotation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100, 14731–14736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Feniouk B.A., Suzuki T., Yoshida M. (2006) The role of subunit epsilon in the catalysis and regulation of FOF1-ATP synthase. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1757, 326–338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mendoza-Hoffmann F., Zarco-Zavala M., Ortega R., García-Trejo J.J. (2018) Control of rotation of the F1FO-ATP synthase nanomotor by an inhibitory α-helix from unfolded ε or intrinsically disordered ζ and IF1 proteins. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 50, 403–424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krah A. (2015) Linking structural features from mitochondrial and bacterial F-type ATP synthases to their distinct mechanisms of ATPase inhibition. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 119, 94–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hirono-Hara Y., Noji H., Nishiura M., Muneyuki E., Hara K.Y., Yasuda R., Kinosita K., Yoshida M. (2001) Pause and rotation of F1-ATPase during catalysis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 13649–13654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McMillan D.G.G., Watanabe R., Cook G.M., Ueno H., Noji H. (2016) Biophysical characterization of a thermoalkaliphilic molecular motor with a high stepping torque gives insight into evolutionary ATP synthase adaptation. J. Biol. Chem. 291, 23965–23977 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Runswick M.J., Bason J.V., Montgomery M.G., Robinson G.C., Fearnley I.M., Walker J.E. (2013) The affinity purification and characterization of ATP synthase complexes from mitochondria. Open Biol. 3, 120160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.PullmanM.E., and , Monroy G.C. (1963) A naturally occurring inhibitor of mitochondrial adenosine triphosphatase. J.Biol. Chem. 238, 3762–3769 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sánchez-Cenizo L., Formentini L., Aldea M., Ortega Á.D., García-Huerta P., Sánchez-Aragó M., Cuezva J.M. (2010) Up-regulation of the ATPase Inhibitory Factor 1 (IF1) of the mitochondrial H+-ATP synthase in human tumors mediates the metabolic shift of cancer cells to a warburg phenotype. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 25308–25313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gómez-Puyou A., de Gómez-Puyou M.T., Ernster L. (1979) Inactive to active transitions of the mitochondrial ATPase complex as controlled by the ATPase inhibitor. Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Bioenerg. 547, 252–257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gordon-Smith D.J., Carbajo R.J., Yang J.C., Videler H., Runswick M.J., Walker J.E., Neuhaus D. (2001) Solution structure of a C-terminal coiled-coil domain from Bovine IF1: the inhibitor protein of F1 ATPase. J. Mol. Biol. 308, 325–339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cabezón E., Arechaga I., Jonathan P., Butler G., Walker J.E. (2000) Dimerization of bovine F1-ATPase by binding the inhibitor protein, IF1. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 28353–28355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gledhill J.R., Montgomery M.G., Leslie A.G.W., Walker J.E. (2007) How the regulatory protein, IF1, inhibits F1-ATPase from bovine mitochondria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104, 15671–15676 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Van Raaij M.J., Orriss G.L., Montgomery M.G., Runswick M.J., Fearnley I.M., Skehel J.M., Walker J.E. (1996) The ATPase inhibitor protein from bovine heart mitochondria: the minimal inhibitory sequence. Biochemistry 35, 15618–15625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bason J.V., Runswick M.J., Fearnley I.M., Walker J.E. (2011) Binding of the inhibitor protein IF1 to bovine F1-ATPase. J. Mol. Biol. 406, 443–453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bason J.V., Montgomery M.G., Leslie A.G.W., Walker J.E. (2014) Pathway of binding of the intrinsically disordered mitochondrial inhibitor protein to F1-ATPase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 111, 11305–11310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Corvest V., Sigalat C., Venard R., Falson P., Mueller D.M., Haraux F. (2005) The binding mechanism of the yeast F1-ATPase inhibitory peptide: role of catalytic intermediates and enzyme turnover. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 9927–9936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Corvest V., Sigalat C., Haraux F. (2007) Insight into the bind-lock mechanism of the yeast mitochondrial ATP synthase inhibitory peptide. Biochemistry 46, 8680–8688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Klein G., Satre M., Vignais P. (1977) Natural protein ATPase inhibitor from Candida utilis mitochondria binding properties of the radiolabeled inhibitor. FEBS Lett. 84, 129–134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Milgrom Y.M. (1989) An ATP dependence of mitochondrial F1-ATPase inactivation by the natural inhibitor protein agrees with the alternating-site binding-change mechanism. FEBS Lett. 246, 202–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wu Q., Andrianaivomananjaona T., Tetaud E., Corvest V., Haraux F. (2014) Interactions involved in grasping and locking of the inhibitory peptide IF1 by mitochondrial ATP synthase. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1837, 761–772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cintrón N.M., Hullihen J., Schwerzmann K., Pedersen P.L. (1982) Proton-adenosinetriphosphatase complex of rat liver mitochondria: effect of its inhibitory peptide on adenosine 5′-triphosphate hydrolytic and functional activities of the enzyme. Biochemistry 21, 1878–1885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gomez-Fernandez J.C., Harris D.A. (1978) A thermodynamic analysis of the interaction between the mitochondrial coupling adenosine triphosphatase and its naturally occurring inhibitor protein. Biochem. J. 176, 967–975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chernyak B.V., Khodjaev E.Y., Kozlov I.A. (1985) The oxidation of sulfhydryl groups in mitochondrial F1-ATPase decreases the rate of its inactivation by the natural protein inhibitor. FEBS Lett. 187, 253–256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Panchenko M.V., Vinogradov A.D. (1985) Interaction between the mitochondrial ATP synthetase and ATPase inhibitor protein. Active/inactive slow pH-dependent transitions of the inhibitor protein. FEBS Lett. 184, 226–230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hayashi S., Ueno H., Shaikh A.R., Umemura M., Kamiya M., Ito Y., Ikeguchi M., Komoriya Y., Iino R., Noji H. (2012) Molecular mechanism of ATP hydrolysis in F1-ATPase revealed by molecular simulations and single-molecule observations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 8447–8454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.