Abstract

Background:

Whether to screen high-risk groups before early peanut introduction is controversial.

Objective:

We sought to determine the risk of peanut allergy (PA) before peanut introduction for infants with (1) moderate-severe eczema, (2) another food allergy (FA), and/or (3) a first-degree relative with peanut allergy (FH).

Methods:

Infants aged 4 to 11 months with no history of peanut ingestion, testing, or reaction and at least 1 of the above risk factors received peanut skin prick test and, depending on skin prick test wheal size, oral food challenge or observed feeding.

Results:

A total of 321 subjects completed the enrollment visit (median age, 7.2 months; 58% males); 78 had eczema only, 11 FA only, 107 FH only, and 125 had multiple risk factors.

Overall, 18% of 195 with eczema, 19% of 59 with FA, and 4% of 201 with FH had PA. Only 1% of 115 with FH and no eczema had PA. Among those with eczema, older age (odds ratio [OR],1.3; 95% CI, 1.04–1.68 per month), higher SCORing Atopic Dermatitis score (OR, 1.19; 95% CI, 1.06–1.34 per 5 points), black (OR, 5.79; 95% CI, 1.92–17.4 compared with white), or Asian race (OR, 6.98; 95% CI, 1.92–25.44) and suspected or diagnosed other FA (OR, 3.98; 95% CI, 1.62–9.80) were associated with PA.

Conclusions:

PA is common in infants with moderate-severe eczema, whereas FH without eczema is not a major risk factor, suggesting screening only in those with significant eczema. Even within the first year of life, introduction at later ages is associated with a higher risk of PA among those with eczema, supporting introduction of peanut as early as possible.

Keywords: Food allergy, peanut allergy, prevention, early introduction

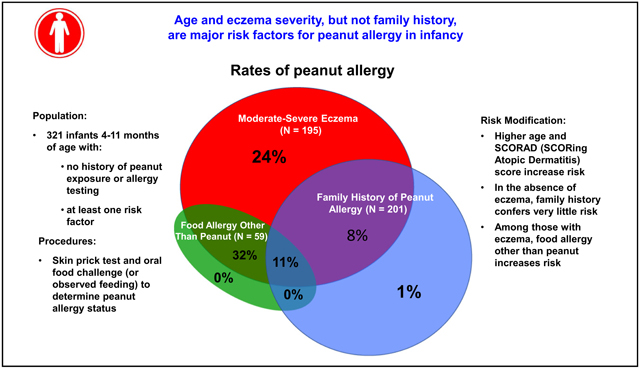

Graphical Abstract:

In 2015, the Learning Early About Peanut Allergy (LEAP) study was published, showing that introduction of peanut at age 4 to 11 months in infants with severe eczema and/or egg allergy reduced the risk of peanut allergy by more than 80% compared with peanut avoidance.1 The LEAP study reversed previous thinking that earlier introduction of allergenic foods led to food allergy, prompting nearly immediate changes in guidelines for food introduction in infants around the world.2,3 Although most countries, public health authorities, and professional societies now recommend “early” introduction of peanut and, sometimes, other allergenic foods, there are many areas of controversy about how to practically implement early introduction of peanut for prevention of allergy.4–9 In the United States, addendum food allergy guidelines sponsored by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) were published in 2017 and followed the LEAP protocol closely in terms of target populations for implementation and screening. These guidelines recommended that in those with severe eczema, egg allergy, or both, screening with skin prick test (SPT) and/or peanut-specific IgE should be done before peanut introduction.2 For infants with mild-moderate eczema, they recommended introduction without screening at around 6 months. In contrast, countries in Europe and Australasia do not generally recommend any screening before peanut introduction, and many infant feeding guidelines do not differentiate recommendations by risk factor.3,10–14 Whether to screen any subgroups of infants before peanut introduction is one of the major controversies surrounding early peanut introduction.

Although no current guidelines recommend screening children on the basis of family history alone, previous guidelines have included infants with a family history as “high-risk.”7,11,15 In practice, parents are often reluctant to introduce peanut when they have an older child who is peanut allergic, and providers commonly perform screening tests in these infants.16,17 However, the true magnitude of risk of peanut allergy in young infants with a first-degree relative with peanut allergy is unclear.15,18,19

For successful implementation of earlier peanut introduction, more data are needed to inform guideline refinement and ensure buy-in across key stakeholders. The goal of this prospective cohort study was to quantify the risk of peanut allergy in infancy for 3 risk factors: moderate-severe eczema, family history of peanut allergy, and presence of another physician-diagnosed food allergy.

METHODS

Population

Infants aged 4 to 11 months were recruited to Johns Hopkins Hospital and MassGeneral Hospital for Children using social media advertisements; direct mailing to general pediatric, pediatric allergy, and dermatology practices; My-Chart letters to Johns Hopkins patients; and direct recruitment in the Pediatric Allergy and Dermatology Clinics. Inclusion criteria included no known history of peanut exposure or reaction, no history of peanut IgE or SPT testing, and at least 1 of the following risk factors:

- Moderate-severe eczema as defined by

- an objective SCORing Atopic Dermatitis (SCORAD)20 score of at least 25 on present or previous evaluation, or

- a rash that required the application of topical creams or ointments containing corticosteroids or calcineurin inhibitors and occurred on at least 7 days on 2 separate occasions, or

- being described by the parent or guardian as having been at any time “a bad rash in joints or creases” or “a bad itchy, dry, oozing or crusted rash,”

physician diagnosis of food allergy other than peanut, or

a first-degree relative with a history of either a physician diagnosis of peanut allergy or reported history of symptoms consistent with peanut allergy.

Exclusion criteria included history of a feeding disorder that would make oral food challenge (OFC) difficult, history of eosinophilic gastrointestinal disease, and significant medical history aside from eczema, food allergy, or wheeze. Enrollment started at Johns Hopkins Hospital on December 21, 2016, and expanded to MGH on July 17, 2019. The accrual goal was 400, but because of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 pandemic, enrollment was halted in March 2020 at 325 infants.

Infants were brought to the Pediatric Clinical Research Unit at either Johns Hopkins or Massachusetts General Hospital for the baseline visit, which included informed consent and screening for eligibility, physical examination with quantification of objective and total SCORAD score,21 SPT to peanut extract, histamine, and saline, blood draw, and, depending on the results of the SPT as outlined below, peanut observed feeding, OFC, or referral to allergy clinic with a diagnosis of peanut allergy. For logistical reasons, the observed feeding or OFC could occur up to 2 weeks after the initial screening visit, but typically occurred on the same day. Details of the methods can be found in this article’s Methods section in the Online Repository at www.jacionline.org.

Statistical analysis

The analytical data set used for this report involves only the baseline evaluations and not the outcomes assessed longitudinally until age 30 months. Study data were collected and managed using Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap, Vanderbilt, Tenn) tools hosted at John Hopkins School of Medicine. Peanut allergy status was tabulated by risk factor, stratified into overlapping groups. Infants meeting the entry criteria for eczema were compared with infants not meeting the entry criteria using t test or chi-square test as appropriate to the variable of interest. Multivariable logistic regression was used to estimate associations between risk factors and peanut allergy. All models included age, race, and sex and were restricted to infants who met the inclusion criteria for eczema, hereafter called “moderate-severe eczema.” SCORAD score was included as indicated, and an interaction term between age and SCORAD score was created to assess for interaction. All analyses were done using STATA 14 (College Station, Tex).

The study was funded by the NIAID as a cooperative agreement. The protocol was approved by the NIAID Division of Allergy, Immunology and Transplantation Clinical Research Committee, and the institutional review boards of Johns Hopkins School of Medicine and MassGeneral Hospital for Children (Partners institutional review board). The protocol was monitored by an NIAID-appointed Data and Safety Monitoring Board.

RESULTS

Participants

Three hundred twenty-five children were enrolled (307 at Johns Hopkins and 14 at MassGeneral Hospital for Children). Two withdrew consent before study procedures, 1 was a screen failure after consent and 1 did not complete the observed feeding and did not introduce peanut at home so could not be evaluated, leaving 321 in the analysis population: 78 with moderate-severe eczema only, 107 with family history of peanut allergy only, 11 with personal history of other food allergy only, and 125 with multiple risk factors, for a total of 195 with moderate-severe eczema, 201 with family history of peanut allergy, and 59 with a personal history of food allergy other than peanut. Of those with a first-degree relative with peanut allergy, in 164 (82%) it was a sibling who was allergic, in 33 (16%) it was the parent, and in 4 (2%) both. The mean age at evaluation was 7.2 ± 1.7 months, 58% were males, 74% white, 8% black, 7% Asian, and 12% multiracial or of other racial background. Among those with moderate-severe eczema according to the inclusion criteria, the mean objective SCORAD score was 21 ± 16 (Table I). Among those without moderate-severe eczema meeting inclusion criteria, 34% had a parental report of a history of a skin rash and 5% had a physician’s diagnosis of eczema. Compared with infants without moderate-severe eczema, those with eczema were significantly older and more likely to be black or Asian (see Table E3 in this article’s Online Repository at www.jacionline.org).

TABLE I.

Demographic and other characteristics of the study population by risk factor

| Characteristic | Overall (321) | Risk factor* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moderate-severe eczema (195) | Family history (201) | FA other than peanut (59) | ||

| Age (mo), mean ± SD | 7.2 ± 1.7 | 7.4 ± 1.7 | 7.0 ± 1.7 | 7.4 ± 1.7 |

| Race, % | ||||

| White | 74 | 67 | 75 | 80 |

| Black | 8 | 12 | 5 | 8 |

| Asian | 7 | 9 | 7 | 3 |

| Multi/other | 12 | 12 | 12 | 8 |

| Male sex, % | 58 | 61 | 54 | 67 |

| Moderate-severe eczema, n (%) | 195 (61) | 195 (100) | 86 (43) | 40 (68) |

| Family history of peanut allergy, n (%) | 200 (62) | 86 (44) | 201 (100) | 17 (29) |

| Physician-diagnosed nonpeanut food allergy, n (%) | 59 (18) | 40 (21) | 17 (9) | 59 (100) |

| Suspected or physician-diagnosed nonpeanut food allergy, n (%) | 123 (38) | 88 (45) | 54 (27) | 59 (100) |

| History of suspected or physician-diagnosed nonpeanut food allergy with immediate symptoms, n (%) | 91 (28) | 71 (36) | 34 (17) | 40 (68) |

Subjects may have more than 1 risk factor.

In addition to the 59 with physician-diagnosed nonpeanut allergy, there were 64 with suspected food allergies, for a total of 123 with either a physician-diagnosed or a suspected nonpeanut allergy (Table I). The most common nonpeanut allergies were to milk (66%), egg (23%), soy (20%), or “other” (ie, foods other than milk, egg, soy, sesame, wheat, tree nut, fish, or shellfish, 37%) (see Table E4 in this article’s Online Repository at www.jacionline.org).

Prevalence of peanut allergy at first introduction by risk factor

Of 321 children included in the analysis, 69 (21%) had a positive SPT result, of whom 57 underwent OFC, and 252 (79%) had a negative SPT result, of whom all underwent observed feeding. Thirty-seven children (11% of the total) were found to be peanut allergic at the baseline visit. Of these, 25 (68%) were diagnosed by positive food challenge (22 [59%]) or observed feeding (3 [8%]), and 12 (32%) were deemed peanut allergic by SPT wheal size, including 1 with a peanut SPT size of 8.5 mm, peanut-specific IgE of 1.49 kU/L, and Ara h 2 specific IgE of 1.39 kU//L whose parents refused the food challenge. Of the 284 who were not found to be peanut allergic, 35 (12%) had negative OFC, 237 (83%) had negative observed feeding, and 12 (4%) did not consume sufficient quantity of challenge material, but introduced peanut at home without problems. As above, 1 did not consume sufficient challenge material during the observed feeding and did not introduce peanut so could not be evaluated.

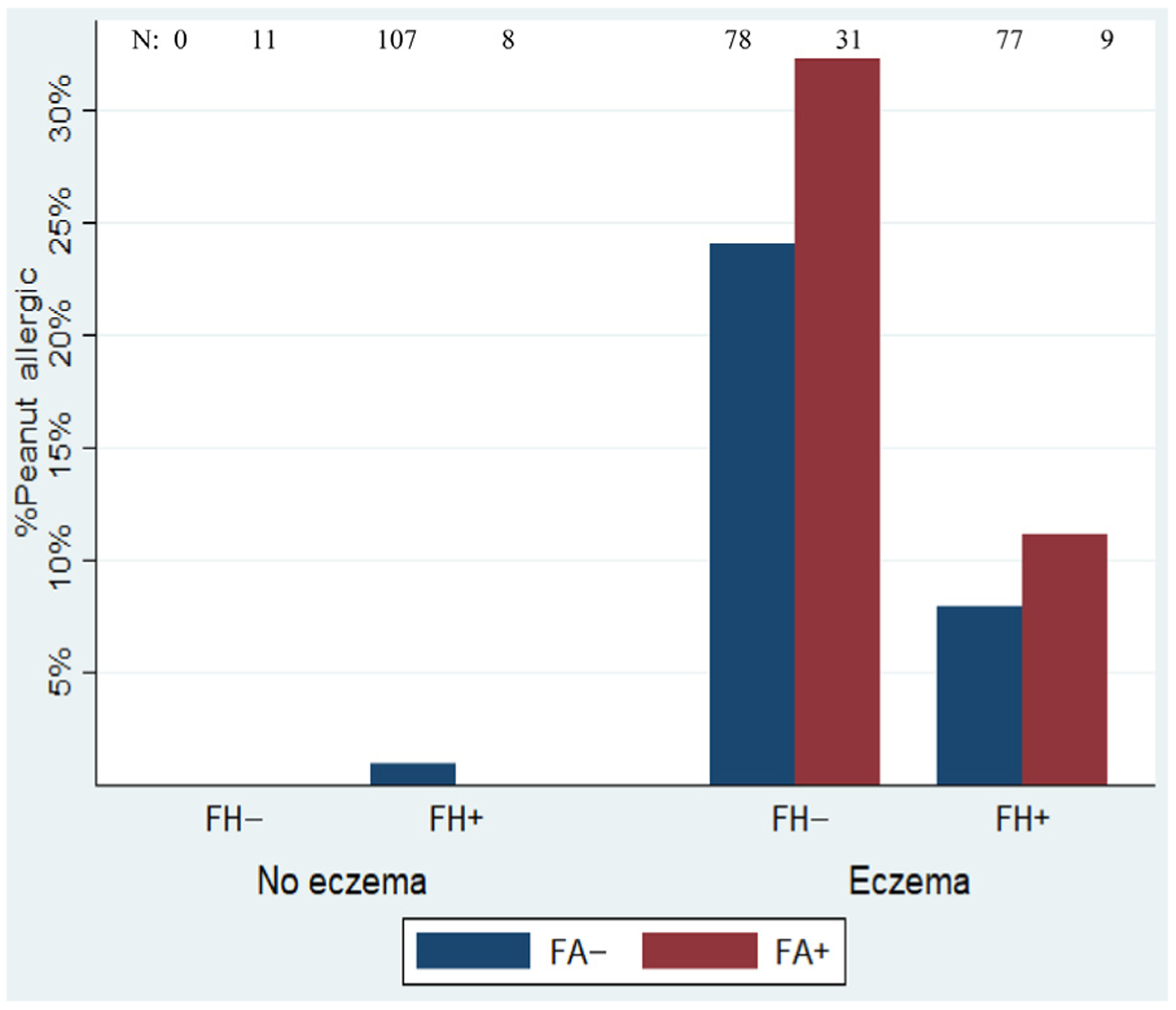

In the overlapping risk factor groups, peanut allergy was diagnosed in 36 of 195 (18%; 95% CI, 13%−25%) with moderate-severe eczema, 8 of 201 (4%, 95% CI, 2%−8%) with a family history of peanut food allergy, and 11 of 59 (19%; 95% CI, 10%−31%) with another food allergy. Of 126 infants who did not meet the inclusion criteria of moderate-severe eczema (107 with family history alone, 8 with family history and food allergy other than peanut, and 11 with food allergy other than peanut), only 1 infant was determined to be peanut allergic (0.8%; 95% CI, 0.02%−4.3%) (Table II and Fig 1). Detailed descriptions of the eczema, age, family history, and food allergy status of those with peanut allergy and those without peanut allergy can be found in Table III.

TABLE II.

Peanut allergy by risk factor

| Risk factor | Total N | Peanut allergic, n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Overlapping groups | ||

| Moderate-severe eczema overall (195) | 195 | 36 (18) |

| Family history overall (201) | 201 | 8 (4) |

| Food allergy other than peanut overall (59) | 59 | 11 (19) |

| Nonoverlapping groups | ||

| Eczema alone (79) | 78 | 19 (24) |

| Eczema plus FH, no FA (77) | 77 | 6 (8) |

| Eczema plus FA, no FH (31) | 31 | 10 (32) |

| Eczema plus FH, plus FA (9) | 9 | 1 (11) |

| FH alone (106) | 107 | 1 (1) |

| FH plus FA, no eczema (8) | 8 | 0 |

| FA alone (11) | 11 | 0 |

FA, Another (nonpeanut) food allergy; FH, family history of peanut allergy.

FIG 1.

Percent peanut allergic by risk category. Eczema, Moderate-severe eczema by inclusion criteria; no eczema, includes those with eczema who did not meet the inclusion criteria; FA, history of a nonpeanut food allergy diagnosed by a physician; FH, family history, defined as a first-degree relative with peanut allergy; N, total number in each group.

TABLE III.

Detailed characteristics of peanut-allergic and peanut nonallergic subjects

| Characteristic | Peanut nonallergic (N = 284) | Peanut allergic (N = 37) |

|---|---|---|

| History of skin rash | 201 (70.8) | 36 (97.3) |

| History of physician- diagnosed eczema | 141 (49.7) | 36 (97.3) |

| History of skin rash occurring at least 7 d on 2 occasions | 161 (56.7) | 36 (97.3) |

| History of skin rash described as “a bad rash in joints or creases” or “a bad, itchy, dry, oozing or crusted rash” | 141 (49.7) | 36 (97.3) |

| History of skin rash treated with medicated cream or ointment | 135 (47.5) | 33 (89.2) |

| Objective SCORAD score category | ||

| 0 (none) | 76 (26.8) | 1 (2.7) |

| 1–14 (mild) | 123 (43.3) | 11 (29.7) |

| 14–40 (moderate) | 66 (23.2) | 15 (40.5) |

| >40 (severe) | 19 (6.7) | 10 (27) |

| Age (mo), mean ± SD | 7.2 ± 1.7 | 8.0 ± 1.7 |

| First-degree relative with peanut allergy | 193 (68.0) | 8 (21.6) |

| Nonpeanut allergy in subject | 48 (16.9) | 11 (29.7) |

Values are n (%) unless otherwise indicated.

Predictors of peanut allergy

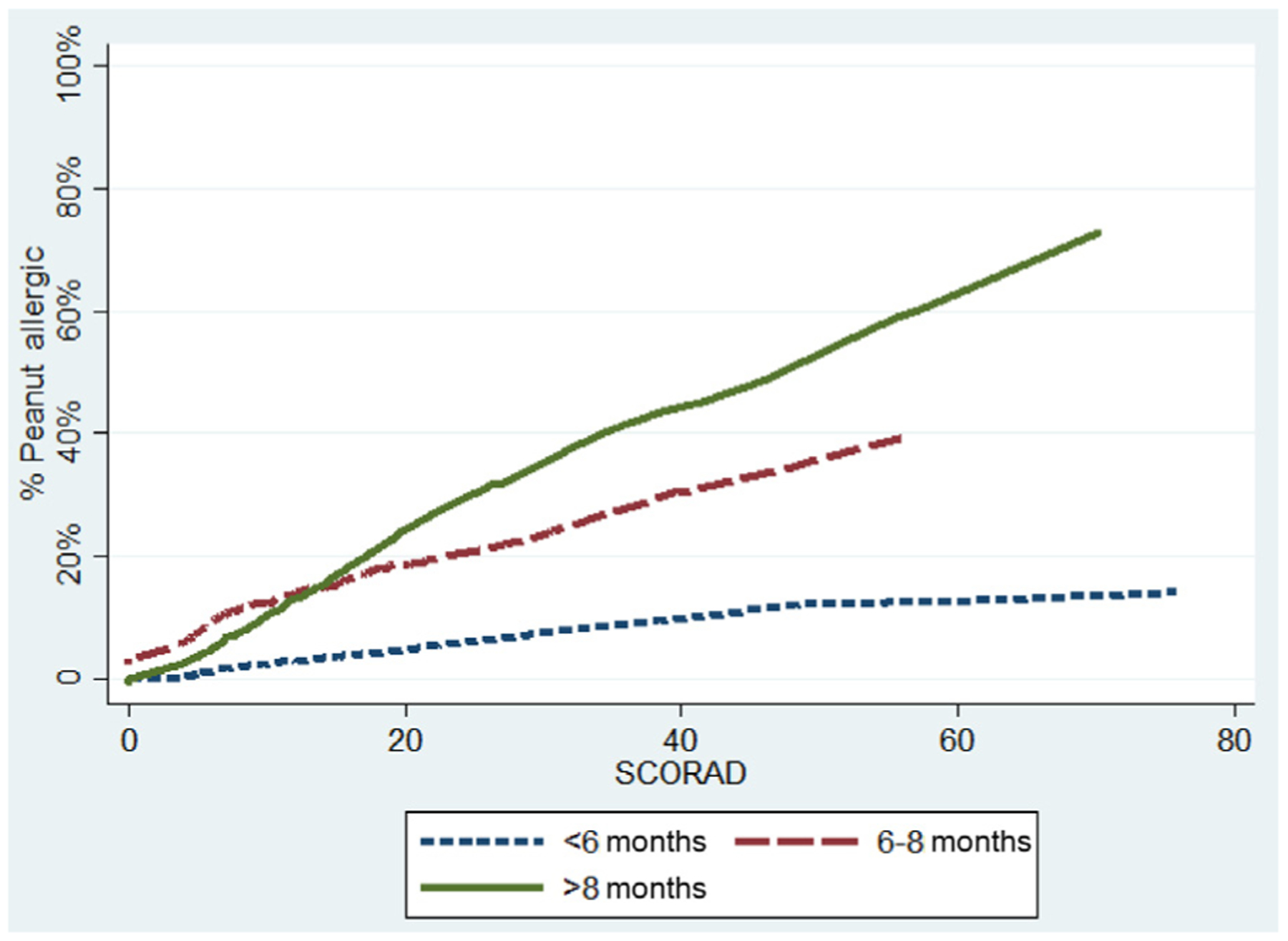

Among those meeting the eczema inclusion criteria, in a multivariable model that included age, race, sex, suspected/diagnosed food allergy, and SCORAD score, the odds of peanut allergy were significantly higher for each increased month of age (odds ratio [OR], 1.3; 95% CI, 1.04–1.68; P = .02), for each 5-point increase in SCORAD score (OR, 1.19; 95% CI, 1.06–1.34; P = .003), and for black (OR, 5.79; 95% CI, 1.92–17.4; P = .003) or Asian race (OR, 6.98; 95% CI, 1.91–25.44; P = .03) compared with white race (Table IV and V and Fig 2). As can be seen in Table IV, even moderate eczema, as defined by objective SCORAD score between 15 and 40, conferred elevated risk of peanut allergy, particularly at older ages.

TABLE IV.

Multivariable analysis of risk factors for peanut allergy among infants with moderate-severe eczema

| Risk factor | OR (95% CI), P value |

|---|---|

| Age, per month | 1.3 (1.04–1.68), .02 |

| Race, | |

| White | Reference |

| Black | 5.79 (1.92–17.4), .003 |

| Asian | 6.98 (1.92–25.44), .003 |

| Multi/other | 2.09 (0.61–7.19), .24 |

| Male sex | 1.17 (0.48–2.86), .72 |

| SCORAD score, per 5 points | 1.19 (1.06–1.34), .003 |

| Physician diagnosis of food allergy or suspected food allergy | 3.98 (1.61–9.80), .003 |

TABLE V.

Risk of peanut allergy by age and SCORAD score category

| Objective SCORAD score | Age | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <6 mo | 6–8 mo | >8 mo | ||||

| Total N | n (%) peanut allergic | Total N | n (%) peanut allergic | Total N | n (%) peanut allergic | |

| 0 (none) | 25 | 0 (0) | 32 | 1 (3) | 20 | 0 (0) |

| 1–14 (mild) | 29 | 0 (0) | 62 | 8 (13) | 43 | 3 (7) |

| 15–40 (moderate) | 21 | 2 (10) | 36 | 5 (14) | 24 | 8 (33) |

| >40 (severe) | 10 | 1 (10) | 11 | 5 (45) | 8 | 4 (50) |

FIG 2.

Probability of peanut allergy by age and objective SCORAD score. Smoothed LOWESS curve, bandwidth(0.8).

Having another food allergy, whether physician diagnosed or suspected by the parents, also increased the risk of peanut allergy (OR, 2.56, 95% CI, 1.02–6.43 for physician diagnosed; OR, 3.98, 95% CI, 1.62–9.80 for suspected or diagnosed food allergy combined) in a model adjusting for race, age, sex, and SCORAD score (Table IV). Other food allergy increased risk regardless of whether the symptoms reported were immediate or nonimmediate (OR, 3.75; 95% CI, 1.47–9.58 for immediate symptoms vs OR, 5.13, 95% CI, 1.27–20.76 for only nonimmediate symptoms), and egg allergy did not increase risk compared with other foods (OR, 1.70, 95% CI, 0.56–5.13 for egg allergy vs OR, 3.20, 95% CI, 1.33–7.73 for other food allergies) (Table E4).

DISCUSSION

In this study of 321 children prospectively enrolled to understand risk factors for peanut allergy in infancy, we found that among infants with moderate-severe eczema, the rate of peanut allergy before peanut introduction was 18%. In contrast, family history of peanut allergy, in the absence of moderate-severe eczema, did not confer substantial risk. Among infants with moderate-severe eczema, older age was strongly associated with increased risk of peanut allergy, as was severity of eczema, such that the presence of peanut allergy for those with severe eczema (SCORAD score >40) who entered the study at an age older than 6 months was nearly 50%. These findings support 2 important concepts: (1) in infants with moderate-severe eczema, introducing peanut-containing foods at or after age 6 months may not be as effective in preventing peanut allergy because many of them will already be peanut allergic and (2) infants with a family history of peanut allergy, but without other risk factors, do not need to be screened for peanut allergy before peanut introduction. In infants with moderate-severe eczema, our data support introduction of peanut-containing foods before age 6 months, and guidelines that encourage providers to consider screening those with severe eczema before introduction, particularly if the infant is in later infancy.

That close to one-fifth of infants with at least moderate eczema may already be peanut allergic at a mean of age 7 months suggests that simply following the LEAP protocol may not be sufficient to prevent peanut allergy. Compared with infants with eczema or egg allergy screened for LEAP, our cohort of infants with moderate-severe eczema were of similar age (7.4 vs 7.8 months), lower mean SCORAD score (21 vs 35 in LEAP), and similar racial distribution.22 Despite these similarities between the LEAP screening population with eczema and our population, had we applied the LEAP inclusion criteria to this study, more than twice as many infants would have been excluded from attempting early peanut introduction (24% vs 11%). In fact, our population already had a rate of peanut allergy/high sensitization similar to what the LEAP “avoiders” ended up having at age 5 years; in the LEAP study, 11% were excluded from the trial for SPT wheal size and 17% of those randomized to avoidance had peanut allergy at age 5 years, for a total of 28% with either SPT wheal size more than 4 mm at baseline or peanut allergy at 5 years, which is only slightly higher than the 26% in our population who either had an SPT wheal size more than 4 mm or were found to be peanut allergic at baseline.1,22 This may suggest that the LEAP study identified infants less likely to be peanut allergic than would typically be found among infants with at least moderate eczema, that we recruited a population more likely to be allergic, or that there are differences between the United Kingdom and the United States in other risk factors for peanut allergy, and thus the rate of peanut allergy. Of note, our rates of peanut allergy in infants with moderate-severe eczema are similar to those in the population-based HealthNuts study of 12- to 14-month-old infants.23 Regardless of the reason, our findings suggest that there is a group of infants with severe eczema who are at a very high risk of peanut allergy if peanut is not introduced by the second half of the first year. In addition, even “moderate” eczema raises the risk of peanut allergy and may be an indication for testing.

It is possible that control of eczema may allow for more successful introduction of foods24 and less food allergy, although interventions studied thus far have had mixed results.25

Age of introduction is an area of controversy surrounding the US and international guidelines.26–28 The World Health Organization, the European Food Safety Association, and the Australasian Society of Clinical Immunology and Allergy recommend starting introduction of complementary foods around age 6 months, with the European Food Safety Association recently stating that there is no evidence that introduction before age 6 months is beneficial for allergy prevention.10,12–14,29 In contrast, both the NIAID-sponsored guidelines and the British Society for Allergy and Clinical Immunology recommend starting peanut as early as age 4 months in high-risk infants.2,13 Our finding that earlier age of introduction was associated with less baseline risk of allergy is in line with both the LEAP screening study, where earlier age was associated with a lower risk of SPT sensitization,22,28 and the Enquiring About Tolerance study,30 which found a protective effect of peanut introduction before age 6 months. The accumulated evidence from these studies and the current study supports introduction of peanut before age 6 months when possible in high-risk groups, as is recommended in the United States and the United Kingdom. Pediatricians and parents should be educated on the benefits of early introduction, with the understanding that it may be difficult to introduce solid foods as early as 4 months in all infants. Although screening may be warranted for infants with severe eczema, it should not delay introduction. Additional methods of prevention of food allergy may also be required to prevent a large portion of peanut allergy.

We found a very low rate of peanut allergy among infants whose only risk factor was a family history of peanut allergy, indicating that this group does not need to be screened before peanut introduction. Of 115 children with a family history of peanut allergy but without moderate-severe eczema, only 1 child was peanut allergic. Although it is not recommended by the Peanut Allergy Prevention Guidelines, performing screening SPT or IgE testing among infants whose only risk factor is family history is common, because parents with a family history of peanut allergy may be unwilling to introduce peanut early in their child’s infancy without testing.17,31,32 Both parental and physician fears about high sibling risk may be driven by previous small reports, which found the risk of peanut allergy in siblings to be 7% to 9%.15,18,19 Generally, these studies reported low rates of peanut ingestion history among siblings classified as allergic and did not verify the allergy with food challenge. Moreover, they found a much higher risk among younger siblings of the index child than among older siblings, suggesting that younger siblings may have been misdiagnosed with peanut allergy and/or had higher rates because of prolonged avoidance of peanut. In the population-based HealthNuts study, where food allergy was confirmed by OFC, the OR conferred by family history of food allergy in the study participants was low and about equal to the risk conferred by being the first-born child (OR, ~1.3).33 Here, we found that in the absence of moderate-severe eczema, the risk of peanut allergy with a peanut-allergic first-degree relative was less than 1%, a risk not larger than the expected baseline risk in the overall population.34 Interestingly, we found that those with family history were less likely to be peanut-allergic, even adjusting for age, SCORAD score, and demographic features (data not shown). There is no clear explanation for this, but it may relate to unmeasured severity factors among those recruited with eczema. The low risk conferred by family history of peanut allergy does not mean that genetic predisposition does not play a role in peanut allergy, but instead that most genes involved may act through a shared risk of eczema,35 interact with eczema susceptibility genes,36 and/or manifest only with prolonged oral avoidance of peanut and/or skin exposure.37 Our results should provide substantial reassurance that screening of younger siblings of peanut-allergic children before peanut introduction is not necessary.

Because we were able to identify very few infants with a previous diagnosis of another nonpeanut food allergy who did not have moderate-severe eczema, it is difficult to assess the magnitude of the risk present in infants with food allergy who do not have eczema. At the time of evaluation for early peanut introduction, many children had very little exposure to other allergenic foods, making the presence of other food allergy of limited utility as a determinative factor for identifying infants for screening or for targeted early introduction. We found no peanut allergy in the small group of infants who had other food allergy but no eczema, but our evaluation of other food allergies was by report, not by food challenge or systematic testing, and we were unable to find very many infants who had suspected food allergies but had not yet been evaluated for peanut allergy. However, among those with moderate-severe eczema, both suspected and physician’s diagnosis of food allergy were associated with increased risk of peanut allergy, suggesting that those with evidence of food allergy and eczema are a particularly high-risk group for peanut allergy. Interestingly, immediate-type symptoms and reactions to common food allergens did not seem to confer a higher risk than nonimmediate symptoms or reactions to uncommon food allergens. Furthermore, with relevance to the US guidelines, nonegg allergy conferred at least as much risk as egg allergy, raising the question of whether egg allergy should be singled out as a risk factor in current peanut allergy guidelines.2

As has been reported for food allergy in general by other studies,38–41 we found substantially higher rates of peanut allergy among those of black or Asian race than among those of white race, even accounting for age and eczema severity. It is not fully understood why these groups may be at a higher risk of food allergy; research in this area could help better understand the mechanism of food allergy development. Prevention measures may also need to specifically address these groups.

Limitations of this analysis include the recruitment strategy, which was not a random population-based sample. To recruit a large number of high-risk infants from a population-based sample would have required a very large sample, which, in the context of the intensive screening that included food challenge, would not have been feasible. Our strategy likely identified infants whose parents may have been more concerned about peanut allergy, inflating the prevalence estimates. However, although it was not a population-based study, we did use broad recruitment methods that likely identified a large portion of those who would seek screening by their pediatrician or allergist, making the results largely generalizable to this group. Another limitation is that not all infants classified as peanut allergic were challenged, but this was because all the first 9 children with SPT wheal size more than 10 mm reacted to the food challenge. Finally, the mobile app that we used to assess the SCORAD score42 does not allow for percent involvement of each given body segment, so tends to overestimate overall body surface area involvement, and thus the overall SCORAD score. This should not affect the relationships calculated between degree of SCORAD score and risk of peanut allergy, but because the SCORAD score may be overestimated here, may tend to underestimate the absolute risk of peanut allergy for a given SCORAD value.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest several considerations that may inform practices about early peanut introduction. First, among infants with moderate-severe eczema, the risk of peanut allergy before peanut introduction is high and rises rapidly over the first year of life. This finding supports the recommendation that introduction of peanut should occur as soon as possible and earlier than age 6 months in high-risk infants and that physicians consider screening infants with severe eczema before introduction, particularly if they are older than 6 months. Second, although the utility of using food allergy in the absence of eczema as a determining factor for screening is not clear, history of symptoms with other foods is associated with increased risk of peanut allergy among those with eczema, and nonegg allergies appear to confer as much risk of peanut allergy as egg allergy. Finally, infants whose only risk factor is family history of peanut allergy do not need to be screened before peanut introduction. Our study contributes to the necessary “fine tuning” that can improve early peanut introduction guidelines, but additional work is needed to optimize approaches that will combine scientific accuracy, feasibility, and public acceptance.

Supplementary Material

Clinical implications:

Introduction of peanut in infants with moderate-severe eczema should start before age 6 months. In the absence of moderate-severe eczema in an infant, family history of peanut allergy alone is not a strong risk factor for peanut allergy.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH)/National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (grant no. 1U01AI125290). This publication was made possible by the Johns Hopkins Institute for Clinical and Translational Research (ICTR), which is funded in part by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) (grant no. UL1 TR003098), a component of the NIH, and the NIH Roadmap for Medical Research. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of the Johns Hopkins ICTR, NCATS, or NIH. The project described was supported by grant number 1UL1TR002541-01. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center for Research Resources, the NCATS, or the NIH. J.D. is funded by the Pearl M. Stetler Fund.

We acknowledge Mharlove Andre for assistance with recruitment and data collection.

Abbreviations used

- LEAP

Learning Early About Peanut Allergy

- NIAID

National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases

- OFC

Oral food challenge

- OR

Odds ratio

- SCORAD

SCORing Atopic Dermatitis

- SPT

Skin prick test

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: Disclaimer: Dr Togias’ authorship of this report does not constitute endorsement by the US National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases or any other US government agency.

Disclosure of potential conflict of interest: C. Keet receives royalties from Up to Date. M. Pistiner has served as a consultant for AAFA, kaléo, and DBV Technologies; received funding from kaléo, DBV Technologies, and National Peanut Board; and is cofounder of AllergyHome and Allergy Certified Training. W. Shreffler has served on the Scientific Advisory Board of Aimmune Therapeutics, and as an advisor to Food Allergy Research and Education (FARE), Buhlmann Laboratories AG, and Sanofi Pasteur. R. Wood receives research support from FARE, Aimmune, DBV, Astellas, Regeneron, Sanofi, and HAL-Allergy, and royalties from Up to Date. The rest of the authors declare that they have no relevant conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Du Toit G, Roberts G, Sayre PH, Bahnson HT, Radulovic S, Santos AF, et al. Randomized trial of peanut consumption in infants at risk for peanut allergy. N Engl J Med 2015;372:803–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Togias A, Cooper SF, Acebal ML, Assa’ad A, Baker JR Jr, Beck LA, et al. Addendum guidelines for the prevention of peanut allergy in the United States: report of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases-sponsored expert panel. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2017;139:29–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Joshi PA, Smith J, Vale S, Campbell DE. The Australasian Society of Clinical Immunology and Allergy infant feeding for allergy prevention guidelines. Med J Aust 2019;210:89–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shaker MS, Iglesia E, Greenhawt M. The health and economic benefits of approaches for peanut introduction in infants with a peanut allergic sibling. Allergy 2019;74:2251–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koplin JJ, Peters RL, Dharmage SC, Gurrin L, Tang MLK, Ponsonby AL, et al. Understanding the feasibility and implications of implementing early peanut introduction for prevention of peanut allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2016;138: 1131–41.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shaker M, Stukus D, Chan ES, Fleischer DM, Spergel JM, Greenhawt M. “To screen or not to screen”: comparing the health and economic benefits of early peanut introduction strategies in five countries. Allergy 2018;73:1707–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Greer FR, Sicherer SH, Burks AW. Effects of early nutritional interventions on the development of atopic disease in infants and children: the role of maternal dietary restriction, breastfeeding, timing of introduction of complementary foods, and hydrolyzed formulas. Pediatrics 2008;121:183–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Greer FR, Sicherer SH, Burks AW. The effects of early nutritional interventions on the development of atopic disease in infants and children: the role of maternal dietary restriction, breastfeeding, hydrolyzed formulas, and timing of introduction of allergenic complementary foods. Pediatrics 2019;143:e20190281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Assa’ad A Guidelines for the prevention of peanut allergy in the United States: from development to prospective outcomes. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2017;118:125–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Health Organization. Complementary feeding. Available at: https://www.who.int/health-topics/complementary-feeding#tab=tab_2.AccessedJune 26, 2020.

- 11.American Academy of Pediatrics. Committee on Nutrition. Hypoallergenic infant formulas. Pediatrics 2000;106:346–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Australian Society of Clinical Immunolgy and Allergy. Infant feeding and allergy prevention. 2016. Available at: https://www.allergy.org.au/images/pcc/ASCIA_Guidelines_infant_feeding_and_allergy_prevention.pdf.AccessedJune 26, 2020.

- 13.British Society for Allergy & Clinical Immunology. Preventing food allergy in higher risk infants. 2018. Available at: https://www.bsaci.org/pdf/Early-feeding-guidance-for-HCPs.pdf.AccessedJune 26, 2020.

- 14.European Food Safety Authority. Age to start complementary feeding in infants. 2019. Available at: https://www.efsa.europa.eu/sites/default/files/Complementary_Feeding_PLS_PDF.pdf.AccessedJune 26, 2020.

- 15.Liem JJ, Huq S, Kozyrskyj AL, Becker AB. Should younger siblings of peanut-allergic children be assessed by an allergist before being fed peanut? Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol 2008;4:144–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tey D, Allen KJ, Peters RL, Koplin JJ, Tang ML, Gurrin LC, et al. Population response to change in infant feeding guidelines for allergy prevention. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2014;133:476–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johnson J, Gupta RS, Bilaver LA, Hu JW, Martin J, Jiang JL, et al. Implementation of the 2017 Addendum Guidelines for Peanut Allergy Prevention Among AAAAI Allergists and Immunologists. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2019;143:Ab421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lavine E, Clarke A, Joseph L, Shand G, Alizadehfar R, Asai Y, et al. Peanut avoidance and peanut allergy diagnosis in siblings of peanut allergic children. Clin Exp Allergy 2015;45:249–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hourihane JO, Dean TP, Warner JO. Peanut allergy in relation to heredity, maternal diet, and other atopic diseases: results of a questionnaire survey, skin prick testing, and food challenges. BMJ 1996;313:518–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.SCORAD. European Task Force on Atopic Dermatitis. Copyright Pr JF Stalder - ETFAD - 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Severity scoring of atopic dermatitis: the SCORAD index. Consensus Report of the European Task Force on Atopic Dermatitis. Dermatology 1993;186:23–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Du Toit G, Roberts G, Sayre PH, Plaut M, Bahnson HT, Mitchell H, et al. Identifying infants at high risk of peanut allergy: the Learning Early About Peanut Allergy (LEAP) screening study. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2013;131:135–43.e1-e12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Martin PE, Eckert JK, Koplin JJ, Lowe AJ, Gurrin LC, Dharmage SC, et al. Which infants with eczema are at risk of food allergy? Results from a population-based cohort. Clin Exp Allergy 2015;45:255–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Natsume O, Kabashima S, Nakazato J, Yamamoto-Hanada K, Narita M, Kondo M, et al. Two-step egg introduction for prevention of egg allergy in high-risk infants with eczema (PETIT): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2017;389:276–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brough HA, Nadeau KC, Sindher SB, Alkotob SS, Chan S, Bahnson HT, et al. Epicutaneous sensitization in the development of food allergy: what is the evidence and how can this be prevented? [published online ahead of print April 6, 2020]. Allergy. 10.1111/all.14304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Netting MJ, Campbell DE, Koplin JJ, Beck KM, McWilliam V, Dharmage SC, et al. An Australian Consensus on Infant Feeding Guidelines to Prevent Food Allergy: Outcomes From the Australian Infant Feeding Summit. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2017;5:1617–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Koplin JJ, Allen KJ. Optimal timing for solids introduction—why are the guidelines always changing? Clin Exp Allergy 2013;43:826–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lawson K, Bahnson HT, Brittain E, Sever M, Du Toit G, Lack G, et al. Letter of response to Greenhawt et al. ‘LEAPing Through the Looking Glass: Secondary Analysis of the Effect of Skin Test Size and Age of Introduction on Peanut Tolerance after Early Peanut Introduction’. Allergy 2017;72:1267–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fewtrell M, Bronsky J, Campoy C. Complementary feeding: a position paper by the European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition (ESPGHAN) Committee on Nutrition: Erratum (vol 64, pg 119, 2017). J Pediatr Gastr Nutr 2017;64:653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Perkin MR, Logan K, Tseng A, Raji B, Ayis S, Peacock J, et al. Randomized trial of introduction of allergenic foods in breast-fed infants. N Engl J Med 2016;374: 1733–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Greenhawt M, Chan ES, Fleischer DM, Hicks A, Wilson R, Shaker M, et al. Caregiver and expecting caregiver support for early peanut introduction guidelines. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2018;120:620–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Volertas S, Coury M, Sanders G, McMorris M, Gupta M. Real-life infant peanut allergy testing in the post-NIAID peanut guideline world. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2020;8:1091–3.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Koplin JJ, Allen KJ, Gurrin LC, Peters RL, Lowe AJ, Tang ML, et al. The impact of family history of allergy on risk of food allergy: a population-based study of infants. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2013;10:5364–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rona RJ, Keil T, Summers C, Gislason D, Zuidmeer L, Sodergren E, et al. The prevalence of food allergy: a meta-analysis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2007;120: 638–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marenholz I, Esparza-Gordillo J, Lee YA. The genetics of the skin barrier in eczema and other allergic disorders. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol 2015;15: 426–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hong X, Tsai HJ, Wang X. Genetics of food allergy. Curr Opin Pediatr 2009;21: 770–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Winters A, Bahnson HT, Ruczinski I, Boorgula MP, Malley C, Keramati AR, et al. The MALT1 locus and peanut avoidance in the risk for peanut allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2019;143:2326–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Koplin JJ, Peters RL, Ponsonby AL, Gurrin LC, Hill D, Tang ML, et al. Increased risk of peanut allergy in infants of Asian-born parents compared to those of Australian-born parents. Allergy 2014;69:1639–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dunlop JH, Keet CA. Allergic diseases among Asian children in the United States. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2019;144:1727–9.e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McGowan EC, Matsui EC, McCormack MC, Pollack CE, Peng R, Keet CA. Effect of poverty, urbanization, and race/ethnicity on perceived food allergy in the United States. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2015;115:85–6.e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Keet CA, Savage JH, Seopaul S, Peng RD, Wood RA, Matsui EC. Temporal trends and racial/ethnic disparity in self-reported pediatric food allergy in the United States. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2014;112: 222–9.e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.SCORAD & PO-SCORAD Applications. Fondation Pour La Dermatite Atopique Recherche et Education. Available at: https://www.fondation-dermatiteatopique.org/sites/default/files/leaflet_po-scorad.pdf.AccessedOctober 27, 2020.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.