Abstract

Background:

Pulmonary rehabilitation (PR) is an interdisciplinary intervention designed to improve the physical status and the psychological condition of people with chronic respiratory diseases. To improve patients' participation in PR programs, telerehabilitation has been introduced.

Objective:

This study aimed to identify factors that could influence the intention to use telerehabilitation among patients attending traditional PR programs.

Methods:

This cross-sectional study recruited subjects attending the PR centers in the hospitals of the Indiana State University, United States of America, between January and May 2017. Data were collected using self-administered Tele-Pulmonary Rehabilitation Acceptance Scale (TPRAS). TPRAS had two subscales: perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use. Behavioral intention (BI) was the dependent variable, and all responses were dichotomized into positive and negative intention to use. Multiple logistic regressions were performed to assess the influence of variables on the intention to use telerehabilitation.

Results:

A total of 134 respondents were included in this study, of which 61.2% indicated positive intention to use telerehabilitation. Perceived usefulness was a significant predictor of the positive intentions to use of telerehabilitation. Duration of respiratory disease was negatively associated with the use of telerehabilitation.

Conclusion:

Perceived usefulness was a significant predictor of using telerehabilitation. The findings of this study may be useful for health-care organizations in improving the adoption of telerehabilitation or in its implementation. Future telerehabilitation acceptance studies could explore the effects of additional factors including computer literacy and culture on the intention to use telerehabilitation.

Keywords: Patient acceptance, pulmonary rehabilitation, respiratory care, technology acceptance, telehealth, telerehabilitation

INTRODUCTION

Pulmonary rehabilitation (PR) is a multidisciplinary intervention that is designed to reduce symptoms and complications of respiratory diseases. PR often includes sessions of education about the disease, muscle strengthening exercises and psychological support.[1] PR could reduce patient's dyspnea, improve exercise capacity, improve mental health status, and improve health-related quality of life (HRQoL).[2,3,4,5,6]

When referred, adherence to PR programs is critical for achieving the goals in managing disease symptoms. Poor adherence could result in high morbidity rates, high health-care costs, more frequent hospitalizations and poor quality of life.[7] A study showed that although the benefits associated with PR were well known, not all patients referred to a PR program attended it, and among those who did, a proportion did not complete the program.[8] Adherence to PR programs for subjects with chronic diseases is expected to be low because of the symptoms, including dyspnea and muscle weakness.[9] To improve participation and adherence to PR programs, telerehabilitation has been introduced. Telerehabilitation has the potential to facilitate independent rehabilitation in the patient's home.[10]

In telerehabilitation, telecommunication technology is used as a means to provide and receive rehabilitation services for subjects at home.[10] Using telerehabilitation was associated with positive clinical outcomes for subjects with COPD that include improvements in HRQoL, exercise capacity, dyspnea level, and the sense of social support.[11] Users' acceptance of the technology is suggested as one of the determinants of future use and adherence to telerehabilitation services.[12] People with low levels of technology acceptance might use the telerehabilitation services less, which might reduce the potential benefits of the programs.[12]

Determinants of the positive intention to use telerehabilitation are not well-known. Particularly, there is a gap in the literature about the factors influencing people's intention to use telerehabilitation for PR. Therefore, the goal of this study was to determine factors influencing people's intention to use telerehabilitation. Specifically, we examined the influence of the subject's perception of the benefits of the telerehabilitation, perception of ease of using telerehabilitation, age, duration of the disease, and travel time to the rehabilitation center on the behavioral intention to use telerehabilitation.

METHODS

Design, setting and participants

This cross-sectional study used convenience sampling[13] to recruit subjects attending the PR centers in eight hospitals of the Indiana State University, United States of America, between January and May 2017. The Institutional Review Board of Indiana University–Purdue University at Indianapolis approved this study.

The sample size was calculated based on the number of responses required to conduct factor analysis statistics, i.e., 5 to 10 times the number of items in a scale.[14] The scale used to collect the data had 13 items; therefore, the targeted sample size for this study was between 65 and 130 subjects. The number of patients regularly attending the Indiana University Health PR centers in a single week ranged from 10 to 40 patients, with trips twice weekly. Participants were considered eligible for the study if they (1) could read and write in English, (2) were are aged >18 years, and (3) currently attending any of the PR programs at the Indiana University Health for any respiratory condition (e.g., COPD, cystic fibrosis, or post lung transplantation).

Data collection tool and procedure

Data were collected with a self-administered (paper-based) survey using the Tele-Pulmonary Rehabilitation Acceptance Scale (TPRAS). TPRAS was previously developed from the technology acceptance model (TAM) to specifically measure acceptance of telerehabilitation, and was found to have strong evidence of content validity.[15] TPRAS has two subscales, perceived usefulness (PU) and perceived ease of use (PEOU). PU was defined as the degree to which a subject believes that using telerehabilitation will be associated with clinical and other benefits. PEOU was defined as the degree to which a subject believes that using telerehabilitation would be with minimum effort. Behavioral intention (BI) was set as the dependent variable of the factors, and was defined as the extent to which a subject is ready to use telerehabilitation or the possibility of using it in the future.

The coordinators from the PR programs were asked to distribute recruitment flyers to all patients attending the programs. The flyer included information about the study's purpose and information about telerehabilitation. Those who agreed to participate were first requested to read and complete the consent form and watch a telerehabilitation example video on YouTube before responding to the questionnaire. All the participants were informed that information collected in this study will be used only for research purposes and in ways that will not reveal their identities. Participants received an incentive equivalent to $10 upon survey completion. All the participants were able to read and answer the questions by themselves.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analyses in this study were performed using the SPSS 24.0 software (SPSS Inc., Armonk, NY, USA). Data screening was performed for missing data and outliers. No replacement for the missed data was used. Therefore, the frequency of available responses to a specific question was calculated as a percentage of all valid responses only. However, responses that were missing data from key demographics (e.g., age, duration of the disease, and travel time to the rehabilitation center) or subscales' items were excluded from the analysis.

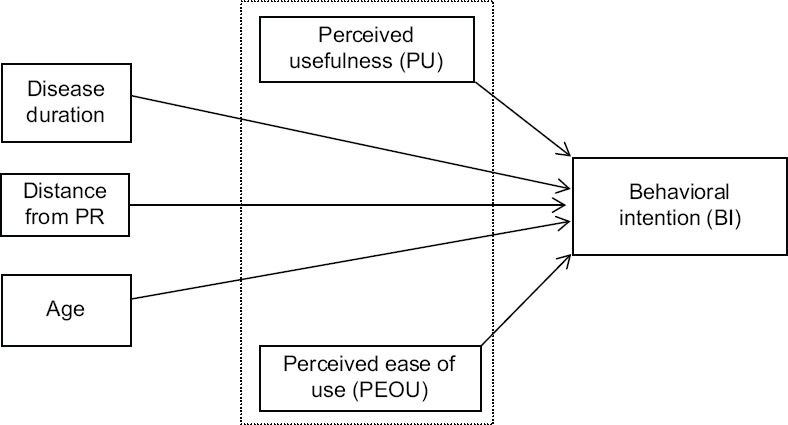

Multiple logistic regressions were performed on the variables included in the prediction model to examine their influences on the intention to use telerehabilitation. BI was considered as the dependent variable, while PU, PEOU, age, duration of the disease, and travel time to the rehabilitation center were added to the model as the predictor variables. The dependent variable (BI) was dichotomized to two categories (Agree or Disagree) based on the participants' responses on the 5-point Likert scale. Scores above the midpoint value of 2.5 were considered as positive intention, and scores equal or below the midpoint value considered as negative intention. The statistical significance level P value for all the analyses was set as <0.05. For the model's variables and their relationships to the dependent variable, please see Figure 1.

Figure 1.

A model predicting participants' intentions to use telerehabilitation

RESULTS

A total of 134 subjects completed the survey from the eight hospital-based outpatient PR programs. The participants' age ranged from 19 to 87 years (mean ± SD: 66.07 ± 10.74 years). When the participants were asked about their perception of travel time from home to the PR center, 53% estimated their travel time to be 16 to 30 minutes. The majority of the participants (88.6%) used their cars to come to the PR center. Of the participants, 20.8% indicated that they never used the Internet. None of the participants in this sample had used telehealth or telerehabilitation to receive health-care services. Table 1 presents the overall sample characteristics. Of all the participants, 61.2% indicated a positive intention to use telerehabilitation.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics (n=134)

| Characteristic | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age (years), mean±SD (range) | 66.07±10.74 (19-87) |

| Gender | |

| Female | 67 (50) |

| Male | 66 (49.25) |

| No answer | 1 (0.75) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Hispanic or Latino | 1 (0.75) |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 123 (91.8) |

| No answer | 10 (7.5) |

| Race | |

| American Indian or Alaskan native | 1 (0.75) |

| Black or African American | 19 (14.2) |

| Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander | 1 (0.75) |

| White | 108 (80.6) |

| Biracial | 2 (1.5) |

| No answer | 3 (2.2) |

| Level of education | |

| Less than a high school degree | 6 (4.47) |

| High school degree or diploma | 68 (50.74) |

| Associate degree | 19 (14.17) |

| Bachelor degree | 20 (15) |

| Graduate degree | 12 (8.95) |

| No answer | 9 (6.7) |

| Approximate travel time to the rehabilitation center (min) | |

| <15 | 48 (35.8) |

| Between 16 and 30 | 70 (52.2) |

| Between 31 and 60 | 14 (10.5) |

| No answer | 2 (1.5) |

| Household income | |

| Income is not enough for the basic needs | 11 (8.2) |

| Income is just enough for the basic needs | 56 (41.8) |

| Financially comfortable | 38 (28.4) |

| Preferred not to disclose | 29 (21.6) |

| Types of transportation | |

| Own car | 117 (87.3) |

| Public transportation (buses, trains, etc.) | 5 (3.7) |

| Taxi cab or other similar services | 2 (1.5) |

| Transportation offered via family friend | 8 (6) |

| No answer | 2 (1.5) |

| Type of device used to access the Internet | |

| PCs | 45 (33.6) |

| Laptops | 55 (41) |

| Smartphones | 43 (32) |

| Tablets | 46 (34.3) |

| Smart TVs | 8 (6) |

| No internet access | 29 (21.6) |

| Disease duration (years), mean±SD (mode) | 8.9±10.7 (10.00) |

SD – Standard deviation

In the multiple regression analyses, PU, PEOU, age, duration of the disease, and travel time from home to the rehabilitation center were examined to determine their influences on the BI to use telerehabilitation, and only PU was found to have a significant effect (β = 1.88, P < .01) [Table 2].

Table 2.

Relationship between the variables and behavioral intention

| Model | β | Wald | P | OR | 95% CI for OR (lower-upper) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PU | 1.88 | 6.43 | 0.01 | 6.57 | 1.53-28.12 |

| PEOU | 0.89 | 1.61 | 0.20 | 2.44 | 0.62-9.66 |

| Age | 0.02 | 0.75 | 0.39 | 1.02 | 0.98-1.06 |

| Duration of the disease | <−0.01 | 0.02 | 0.89 | 1.00 | 0.96-1.04 |

| Distance from the PR center | −0.01 | 0.23 | 0.63 | 0.99 | 0.94-1.04 |

Dependent variable: Behavioral intention. PR – Pulmonary rehabilitation; PU – Perceived usefulness; PEOU – Perceived ease of use; OR – Odds ratio; CI – Confidence interval

DISCUSSION

This study found that about 60% of the participants had a positive intention to use telerehabilitation. The results of this study differ from those of a similar study conducted by Seidman et al., in which 40% of the patients had a positive intention to use telerehabilitation and another 20% were undecided.[16] Notably, unlike the study by Seidman et al., no neutral middle choice was provided in our survey's response scale. This may have contributed to differences in the findings between the two studies, as lack of a neutral choice mandates the participants to provide a more definitive response. In addition, the study by Seidman et al. provided written definitions of telerehabilitation to participants, while we used a brochure and a video to introduce the concept of telerehabilitation to the participants, which may have improved their understanding and perceptions about telerehabilitation.

This study found that perceived usefulness of telerehabilitation has a significant influence on the participants' intention to use it, which was the same as that of other studies.[17,18,19] PEOU was found to have no significant effect on the intention to use telerehabilitation in our study (P = 0.20). In contrast, many studies found that the PEOU (effort expectancy) had a positive significant effect on the intention to use telehealth.[17,18,19] However, participants had used the telehealth systems for 30 days in two of these studies;[18,19] therefore, the heterogeneity among the participants of these two and our study makes the direct comparability of PEOU difficult.

Our study showed that age has no significant effect on the behavioral intention to use telerehabilitation. Similarly, Cimperman et al. examined the influence of age on the intention to use telehealth and found no significant influence.[17] Due to the effects of aging, which includes physical and cognitive limitations, low confidence, and difficulties in comprehension, elderly people may face difficulties when using the Internet and the communication technologies.[20,21] Considering the needs of the older adults when designing telerehabilitation programs will improve acceptance and compliance with the proposed services. Future telerehabilitation programs constructed with age-appropriate designs such as easy navigation screens, sound activated features, and light-weight devices would make it easer for older adults to accept telerehabilitation.

Telehealth was introduced as a solution to the barriers of receiving health care services, such as transportation difficulties and living in a rural area.[8,22] Traveling time from home to the rehabilitation centers was not a significant influence on the intention to use telerehabilitation in our study. The current study investigated whether living in an area far from the PR center, or having transportation difficulties may affect the acceptance of receiving rehabilitation services at home through telerehabilitation. Most of the subjects in our study sample (87.3%) were using their own cars to reach the PR centers. The majority of the participants (52.2%) indicated that it takes between 16 to 30 minutes for them to reach the PR centers from their homes. Both factors suggest that subjects in our sample have no difficulties in reaching the PR centers, which affected their perceptions about telerehabilitation. No previous study has examined the effect of the travel distance to PR or the type of transportation on patients' acceptance of using telerehabilitation. Future studies need to explore the influence of travelling longer distance to reach the PR centers on telerehabilitation acceptance in other geographic areas as well as in countries where transportation may be difficult.

Our results showed that disease duration was negatively associated with the intention to use telerehabilitation. This suggests that the longer the respiratory disease duration, the less the patients would accept using telerehabilitation. The negative association between the length of contracting the disease and the intention to use telerehabilitation can be explained by aging-related changes including the disease progression likely affecting patients' perception of telerehabilitation.

Limitations

A limitation of this study was the relatively small sample size. However, recruiting subjects was challenging, as they come to the PR centers twice a week for about an 1 hour and have had respiratory conditions that limit their ability to engage in conversations, especially after an exercise session. In addition, to introduce the concept and benefits of telerehabilitation to the participants, the study was unable to provide a telerehabilitation program due to its unavailability. Not receiving the actual sense of telerehabilitation could possibly have affected its perception. Although the face validity of the scale assessed its readability, as data were self-reported, the literacy level of the participants could have resulted in differences in understanding and, consequently, in responses. The self-reported data collection may also have resulted in recall and reporting bias.

CONCLUSION

This study showed that perceived usefulness was a significant predictor of the intention to use telerehabilitation, while age, disease duration, and travel time to the PR center were not. The findings of this study may be useful for health-care organizations in improving the adoption of telerehabilitation or in its implementation. Future telerehabilitation acceptance studies could explore the effects of additional factors including computer literacy and culture on the intention to use telerehabilitation.

Ethical considerations

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Indiana University–Purdue University at Indianapolis (protocol #1403903178) on November 28, 2016. The study was conducted in adherence with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, 2013, and all participants provided their written consent for participation.

Peer review

This article was peer-reviewed by two independent and anonymous reviewers.

Financial support and sponsorship

None.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Mrs. Debbie Koehl from the Indiana University Methodist Hospital (Indianapolis, IN, USA) for assistance in recruiting participants.

REFERENCES

- 1.McCarthy B, Casey D, Devane D, Murphy K, Murphy E, Lacasse Y. Pulmonary rehabilitation for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;2:CD003793. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003793.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carlin BW. Pulmonary rehabilitation and chronic lung disease: Opportunities for the respiratory therapist. Respir Care. 2009;54:1091–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ries AL, Bauldoff GS, Carlin BW, Casaburi R, Emery CF, Mahler DA, et al. Pulmonary rehabilitation: Joint ACCP/AACVPR evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2007;131:4S–42S. doi: 10.1378/chest.06-2418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Holland AE, Hill CJ, Nehez E, Ntoumenopoulos G. Does unsupported upper limb exercise training improve symptoms and quality of life for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease? J Cardiopulm Rehabil. 2004;24:422–7. doi: 10.1097/00008483-200411000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Garvey C, Bayles MP, Hamm LF, Hill K, Holland A, Limberg TM, et al. Pulmonary Rehabilitation exercise prescription in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Review of selected guidelines: An official statement from the american association of cardiovascular and pulmonary rehabilitation. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev. 2016;36:75–83. doi: 10.1097/HCR.0000000000000171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ko FW, Cheung NK, Rainer TH, Lum C, Wong I, Hui DS. Comprehensive care programme for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A randomised controlled trial. Thorax. 2017;72:122–8. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2016-208396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scullion JE. Helping patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease adhere to regimens. Prim Heal Care. 2010;20:33–9. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Keating A, Lee A, Holland AE. What prevents people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease from attending pulmonary rehabilitation.A systematic review? Chron Respir Dis. 2011;8:89–99. doi: 10.1177/1479972310393756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fernández AM, Pascual J, Ferrando C, Arnal A, Vergara I, Sevila V. Home-based pulmonary rehabilitation in very severe COPD: Is it safe and useful? J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev. 2009;29:325–31. doi: 10.1097/HCR.0b013e3181ac7b9d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tang J, Mandrusiak A, Russell T. The feasibility and validity of a remote pulse oximetry system for pulmonary rehabilitation: A pilot study. Int J Telemed Appl. 2012;2012:798791. doi: 10.1155/2012/798791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Almojaibel AA. Delivering pulmonary rehabilitation for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease at home using telehealth: A review of the literature. Saudi J Med Med Sci. 2016;4:164–71. doi: 10.4103/1658-631X.188247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huis in 't Veld RM, Kosterink SM, Barbe T, Lindegård A, Marecek T, Vollenbroek-Hutten MM. Relation between patient satisfaction, compliance and the clinical benefit of a teletreatment application for chronic pain. J Telemed Telecare. 2010;16:322–8. doi: 10.1258/jtt.2010.006006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Methods of Sampling from a Population | Health Knowledge. [Last accessed on 2021 Jun 21]. Available from: https://www.healthknowledg e.org.uk/public-health-textbook/research-methods/1a-epidemiology/methods-of-sampling-population .

- 14.Ferketich S. Focus on psychometrics.Aspects of item analysis. Res Nurs Health. 1991;14:165–8. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770140211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Almojaibel AA, Munk N, Goodfellow LT, Fisher TF, Miller KK, Comer AR, et al. Development and validation of the tele-pulmonary rehabilitation acceptance scale. Respir Care. 2019;64:1057–64. doi: 10.4187/respcare.06432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Seidman Z, McNamara R, Wootton S, Leung R, Spencer L, Dale M, et al. People attending pulmonary rehabilitation demonstrate a substantial engagement with technology and willingness to use telerehabilitation: A survey. J Physiother. 2017;63:175–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jphys.2017.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cimperman M, Makovec Brenčič M, Trkman P. Analyzing older users' home telehealth services acceptance behavior-applying an extended UTAUT model. Int J Med Inform. 2016;90:22–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2016.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Diño MJ, de Guzman AB. Using partial least squares (PLS) in predicting behavioral intention for telehealth use among filipino elderly. Educ Gerontol. 2015;41:53–68. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tsai CH. Integrating social capital theory, social cognitive theory, and the technology acceptance model to explore a behavioral model of telehealth systems. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2014;11:4905–25. doi: 10.3390/ijerph110504905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang L, Rau PL, Salvendy G. Older adults' acceptance of information technology. Educ Gerontol. 2011;37:1081–99. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chang J, McAllister C, McCaslin R. Correlates of, and barriers to, Internet use among older adults. J Gerontol Soc Work. 2015;58:66–85. doi: 10.1080/01634372.2014.913754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Young P, Dewse M, Fergusson W, Kolbe J. Respiratory rehabilitation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Predictors of nonadherence. Eur Respir J. 1999;13:855–9. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3003.1999.13d27.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]