Abstract

Background

Pulmonary vascular microthrombi are a proposed mechanism of COVID-19 respiratory failure. We hypothesized that early administration of tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) followed by therapeutic heparin would improve pulmonary function in these patients.

Research Question

Does tPA improve pulmonary function in severe COVID-19 respiratory failure, and is it safe?

Study Design and Methods

Adults with COVID-19-induced respiratory failure were randomized from May14, 2020 through March 3, 2021, in two phases. Phase 1 (n = 36) comprised a control group (standard-of-care treatment) vs a tPA bolus (50-mg tPA IV bolus followed by 7 days of heparin; goal activated partial thromboplastin time [aPTT], 60-80 s) group. Phase 2 (n = 14) comprised a control group vs a tPA drip (50-mg tPA IV bolus, followed by tPA drip 2 mg/h plus heparin 500 units/h over 24 h, then heparin to maintain aPTT of 60-80 s for 7 days) group. Patients were excluded from enrollment if they had not undergone a neurologic examination or cross-sectional brain imaging within the previous 4.5 h to rule out stroke and potential for hemorrhagic conversion. The primary outcome was Pao2 to Fio2 ratio improvement from baseline at 48 h after randomization. Secondary outcomes included Pao2 to Fio2 ratio improvement of > 50% or Pao2 to Fio2 ratio of ≥ 200 at 48 h (composite outcome), ventilator-free days (VFD), and mortality.

Results

Fifty patients were randomized: 17 in the control group and 19 in the tPA bolus group in phase 1 and eight in the control group and six in the tPA drip group in phase 2. No severe bleeding events occurred. In the tPA bolus group, the Pao2 to Fio2 ratio values were significantly (P < .017) higher than baseline at 6 through 168 h after randomization; the control group showed no significant improvements. Among patients receiving a tPA bolus, the percent change of Pao2 to Fio2 ratio at 48 h (16.9% control [interquartile range (IQR), –8.3% to 36.8%] vs 29.8% tPA bolus [IQR, 4.5%-88.7%]; P = .11), the composite outcome (11.8% vs 47.4%; P = .03), VFD (0.0 [IQR, 0.0-9.0] vs 12.0 [IQR, 0.0-19.0]; P = .11), and in-hospital mortality (41.2% vs 21.1%; P = .19) did not reach statistically significant differences when compared with those of control participants. The patients who received a tPA drip did not experience benefit.

Interpretation

The combination of tPA bolus plus heparin is safe in severe COVID-19 respiratory failure. A phase 3 study is warranted given the improvements in oxygenation and promising observations in VFD and mortality.

Trial Registry

ClinicalTrials.gov; No.: NCT04357730; URL: www.clinicaltrials.gov

Key Words: ARDS, COVID-19, fibrinolysis, pulmonary failure, tissue plasminogen activator (tPA)

Abbreviations: aPTT, activated partial thromboplastin time; MV, mechanical ventilation; tPA, tissue plasminogen activator; VFD, ventilator-free day

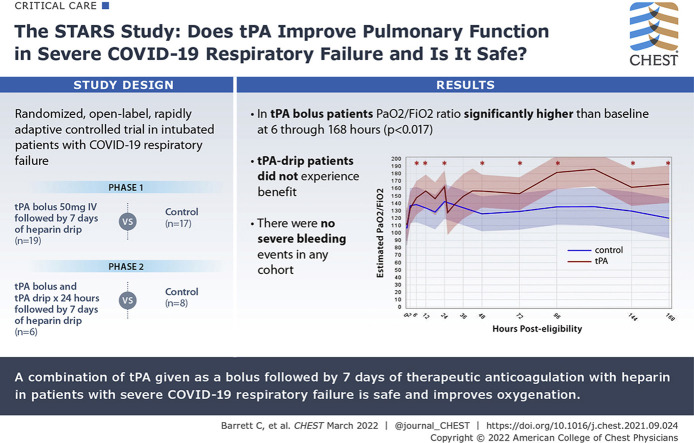

Graphical Abstract

FOR EDITORIAL COMMENT, SEE PAGE 595

Pathologic evaluations of patients with COVID-19 who died of respiratory failure have identified a common pattern of disseminated pulmonary microvascular thrombosis.1, 2, 3, 4 Whole blood coagulation assessment of critically ill patients with COVID-19 with viscoelastic testing universally has demonstrated a hypercoagulable state with increased clot strength5 , 6 and fibrinolysis resistance.7, 8, 9, 10 Early in the clinical course of COVID-19 respiratory failure, most patients show relatively normal lung compliance with markedly elevated dead space ventilation,11 a hallmark of vascular occlusive causes of respiratory failure that is consistent with the previously described autopsy findings.1, 2, 3, 4

In the large multicenter Accelerating COVID-19 Therapeutic Interventions and Vaccines 4 ACUTE/Antithrombotic Therapy to Ameliorate Complications of COVID-19/Randomized, Embedded, Multifactorial Adaptive Platform Trial for Community-Acquired Pneumonia trial (ACTIV-4a/ATTACC/REMAP-CAP trial), therapeutic anticoagulation improved survival to discharge and clinical outcomes in patients with emerging respiratory failure who were not yet dependent on mechanical ventilation (MV; the moderate group) compared with the prophylactic anticoagulation group.12 In contrast, no benefit was observed when therapeutic anticoagulation was initiated after the onset of severe respiratory failure, suggesting that therapeutic anticoagulation is only effective if started before the accumulation of significant clot burden within the lung vasculature. It is in this cohort of patients with severe COVID-19 respiratory failure and a high risk of death that our group hypothesized a potential role for fibrinolytic therapy with tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) to restore pulmonary microvascular patency, reduce dead space ventilation, and improve oxygenation.13, 14, 15

The use of fibrinolytic therapy to treat organ failure was proposed several decades ago,16 and two small phase 1 clinical trials have demonstrated safety and potential feasibility in patients with ARDS.17 The use of fibrinolytic therapy in COVID-19 respiratory failure initially was proposed by our group at the outset of the pandemic,14 and several case series and a small retrospective observational study subsequently were published suggesting a potential benefit from tPA.18, 19, 20, 21 However, the inherent bleeding risks after tPA administration for other clinical indications have limited enthusiasm for this approach.22 To determine whether tPA is a potentially useful and safe treatment of severe COVID-19 respiratory failure, we conducted a vanguard, multicenter, randomized controlled trial of tPA (alteplase) combined with varying doses of heparin vs standard of care treatment in severe COVID-19 respiratory failure (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT04357730). Our hypothesis was that the combination of tPA with heparin would improve oxygenation and reduce adverse outcomes compared with standard of care treatment.

Study Design and Methods

Study Design

The Study of Alteplase for Respiratory Failure in SARS-CoV-2 COVID-19 was a vanguard, phase 2a, multicenter, open-label, rapidly adaptive, pragmatic, randomized controlled clinical trial designed to evaluate whether different dosing regimens of tPA with heparin administered to patients with COVID-19-associated advanced respiratory failure could improve pulmonary function within 48 h (compared with immediately before its administration) without a significant increase in life-threatening hemorrhage. The study design was described previously.23 A multiphase approach with four analyses at short enrollment intervals (three interim and one final) was proposed to allow for rapid safety and efficacy assessment and adaptations at each interim analysis. At the third interim analysis (n = 30), it was decided to implement a tPA drip instead of bolus (detailed herein) as the intervention, which encountered logistical challenges given the relatively short shelf-life of tPA and was not implemented until patient enrollment 37. This resulted in two phases. In phase 1, 36 patients were randomized to either the intervention (tPA bolus, described in detail herein) or control (standard-of-care treatment per each institution’s protocol) group. In phase 2, 14 patients were randomized to the tPA drip (described below) or control (standard-of-care treatment) group.

Setting

Patients were recruited in eight academic tertiary care hospitals across the United States.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Eligible patients (1) were 18 to 75 years years of age; (2) had received a confirmed diagnosis of COVID-19 and severe respiratory failure requiring MV with Pao 2 to Fio 2 ratio of < 150 for > 4 h, (3) had been administered MV for fewer than 11 days at the time of enrollment, and (3) had undergone nonfocal neurologic examination or brain imaging with no evidence of stroke (MRI or CT scan within the prior 4.5 h). When arterial blood gas data were not available, imputed Pao 2 to Fio 2 ratios were allowed using the imputation table developed as part of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute’s Prevention and Early Treatment of Acute Lung Injury Network.24 Exclusion criteria included active bleeding, acute myocardial infarction or cardiac arrest on current admission, hemodynamic instability requiring noradrenaline > 0.2 μm/kg/min, acute renal failure requiring dialysis, liver failure (bilirubin > 3 times baseline), known or suspected cirrhosis, cardiac tamponade, bacterial endocarditis, severe uncontrolled hypertension (systolic BP > 185 mm Hg or diastolic BP > 110 mm Hg), traumatic brain injury within the prior 3 months, stroke or prior history of intracerebral hemorrhage, seizure during the course of COVID-19 before or during hospitalization, diagnosis of brain tumor or arteriovenous malformation, presently receiving extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, major surgery or trauma within the previous 2 weeks, GI or genitourinary bleed within the prior 3 weeks, known bleeding disorder, arterial puncture at a noncompressible site or lumbar puncture within the previous 7 days, pregnancy, prothrombin time international normalized ratio of > 1.7 (with or without concurrent use of warfarin), platelet count of < 100 × 109/L, history of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia, fibrinogen of < 300 mg/dL, P2Y12 receptor inhibitor medication (antiplatelet) within 5 days of enrollment, known abdominal or thoracic aortic aneurysm, history within past 5 years of CNS malignancy or other malignancy that commonly metastasizes to the brain (lung, breast, melanoma), or prisoner status.

Ethics Approval

The trial was performed according to the Food and Drug Administration Investigational New Drug regulations (Identifier: 149634) and was registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (Identifier: NCT04357730). All participating trial sites had study approval and oversight from their respective institutional review boards (e-Appendix 1). Because of the nature of the study, which enrolled critically ill patients receiving MV, informed consent for trial participation was obtained from each patient’s legally authorized representative. An independent data safety monitoring board oversaw the safety of the trial with mandatory reviews at each interim analysis and for all suspected serious adverse events. Data were stored in a Research Electronic Data Capture instrument sponsored by the National Institutes of Health/National Center for Advancing Translational Research Colorado Clinical and Translational Science Award [Grant UL1 TR002535].

Randomization and Masking

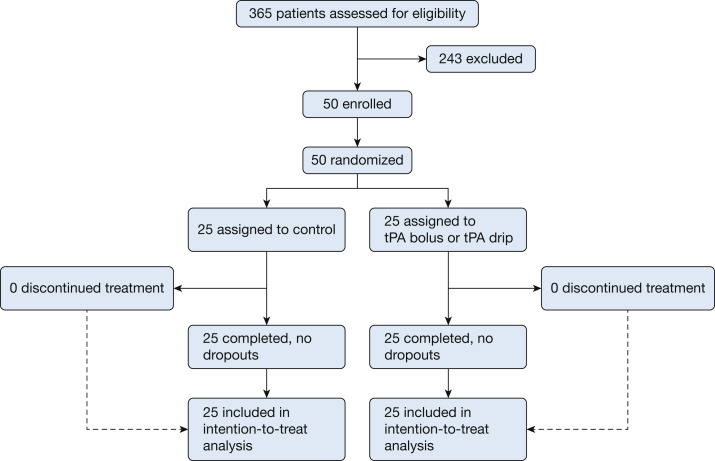

A randomization table was developed using Research Randomizer and automated via the Research Electronic Data Capture instrument to either the intervention (tPA bolus in phase 1 or tPA drip in phase 2, described herein) or control group. This was an open-label study because the intervention carries a risk of bleeding that could be mitigated with antifibrinolytic therapy; thus, no masking of the patients, research team, or primary treatment team occurred. The trial profile is shown in Figure 1 .

Figure 1.

Consolidated Standards for Reporting Trials diagram for the Study of Alteplase for Respiratory Failure in SARS-CoV-2 COVID-19.

Procedures

At randomization, patients assigned to the control group continued their current medical care according to their institution’s protocols, with no input from the study team. Patients randomized to the intervention arm received the following regimens.

During phase 1 (patients 1-36), patients randomized to tPA bolus intervention received an IV 50-mg bolus of 1 mg/mL tPA as a 10-mg push followed by the remaining 40 mg infused over the next 2 h. Immediately on completion of the tPA, a 5,000-unit bolus of IV unfractionated heparin was administered and continued for the next 7 days (or until extubation) as an infusion to maintain activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) of 60 to 80 s. At 24 h after tPA initiation, patients with a Pao 2 to Fio 2 ratio improvement that was at least 20%, but did not meet the primary end point of a 50% improvement (ie, 20%-49% improvement) and who did not demonstrated any of the above-mentioned exclusion criteria, received a second 50-mg tPA bolus, during which the unfractionated heparin infusion was halted and resumed at its prior rate as soon as the second tPA administration was complete. The heparin regimen was maintained for 7 days or until successful extubation.

During phase 2 (patients 37-50), patients randomized to the intervention received the tPA drip intervention consisting of a 50-mg IV bolus of 1 mg/mL tPA as a 10-mg push followed by the remaining 40 mg infused over the next 2 h (not to exceed a 0.9-mg/kg dose). Immediately after this initial tPA infusion, patients received a drip of 2 mg/h tPA over the ensuing 24 h (total, 48-mg infusion) accompanied by an infusion of a subtherapeutic dose of 500 units/h of heparin during the tPA drip. As soon as the tPA drip terminated, the heparin dose was titrated up (no bolus) to maintain an aPTT of 60 to 80 s.

Monitoring

On enrollment, at randomization, and at short intervals thereafter (hours 2, 6, 12, 18, and 24 and daily until day 7 after randomization), we collected data on arterial blood gases, CBC count with platelet count, prothrombin time international normalized ratio, aPTT, fibrinogen, D-dimer, troponin, C-reactive protein, and liver and renal function.

Outcomes

All outcomes were prespecified before the beginning of the trial. The primary outcome was improvement in Pao 2 to Fio 2 ratio at 48 h after randomization over baseline. Preplanned secondary outcomes reported herein include: (1) the composite outcome of achievement of Pao 2 to Fio 2 ratio of ≥ 200 or 50% increase in Pao 2 to Fio 2 ratio, (2) National Early Warning System 2 score, (3) 28-day in-hospital mortality, (4) in-hospital mortality; and (5) ventilator-free days (VFDs) and ICU-free days.25

Cessation rules to terminate treatment in patients enrolled in the intervention arm of the trial are described in e-Appendix 1. Any serious adverse event was to be reported immediately to the sponsor, institutional review board, data safety monitoring board, Food and Drug Administration, and funding agency for discussion and feedback per regulatory and ethical guidelines. Adverse events are reported according to the National Institutes of Health Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, where grade 1 is mild, grade 2 is moderate, grade 3 is severe, grade 4 is life threatening, and grade 5 is event that leads to death.

Statistical Analysis

The sample size calculations accounted for pairwise comparisons between study groups and were performed using PASS version 14 software (NCSS, LLC). Sample size assumptions were power of 80%, overall confidence of 95%, four sequential tests (three interim and one final) using the Pocock α spending function to determine test boundaries, and a baseline Pao 2 to Fio 2 ratio of 149 based on a previous study17 with an overestimated SD of 100. We also assumed a design effect of 1.12 because of the study’s multicenter nature (intraclass correlation coefficient, 0.03; average cluster, 5) and 20% inflation to account for premature deaths. A sample size of 50 (25 in each intervention group and 25 in the control group) eligible patients was able to detect a minimum 91% improvement in Pao 2 to Fio 2 ratio between simultaneously enrolled intervention and control groups. The complete statistical analysis plan and study protocol are included in e-Appendix 2.

Analyses were conducted with SAS version 9.4 software (SAS Institute). We assessed the randomization effectiveness by comparing demographic and baseline clinical characteristics (Table 1 ). All analyses were conducted initially as an intention to treat; no treatment cessation or crossover occurred, so as-treated analyses did not need to be conducted. As previously recommended,26 we assessed pairwise differences between groups of simultaneously enrolled patients in phases 1 and 2, that is, we report separate analyses for phases 1 and 2. No adjustments were made for multiple outcomes, because all study outcomes were prespecified hypotheses, to avoid increased type II errors.27 , 28 Linear mixed models were conducted (continuous outcomes) or generalized estimating equations (categorical outcomes) to account for intrahospital cluster effects and repeated measures. All preplanned comparisons included those within group (improvement over baseline) and between two concurrently enrolled groups. All tests were two-tailed with significance declared at P < .017 at each interim analysis according to the α defined by the Pocock α spending method for an overall trial α of < 0.05.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics in Phase 1

| Variable | Total | Control Group | tPA Bolus + Heparin Group |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. | 36 | 17 | 19 |

| Age, y | 60.0 (52.0-64.0) | 60.0 (57.0-62.0) | 59.0 (47.0-65.0) |

| Male sex | 25 (69.4) | 10 (58.8) | 15 (78.9) |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 36.8 (30.7-42.0) | 36.8 (29.6-42.0) | 37.1 (32.1-43.7) |

| Days from admission to randomization | 2.0 (1.0-4.0) | 2.0 (1.0-4.0) | 2.0 (1.0-4.0) |

| Pulmonary hypertension | 5 (14.3) | 3 (18.8) | 2 (10.5) |

| Diabetes | 12 (34.3) | 6 (37.5) | 6 (31.6) |

| Cardiac disease | 32 (91.4) | 14 (87.5) | 18 (94.7) |

| Hypertension | 10 (27.8) | 6 (35.3) | 4 (21.1) |

| COPD | 28 (80.0) | 13 (81.3) | 15 (78.9) |

| Immunosuppression | 33 (94.3) | 14 (87.5) | 19 (100) |

| Hyperlipidemia | 11 (31.4) | 6 (37.5) | 5 (26.3) |

| Other comorbidity | 12 (36.4) | 5 (35.7) | 7 (36.8) |

| Concurrent infections | 23 (63.9) | 10 (58.8) | 13 (68.4) |

| Dexamethasone | 20 (55.6) | 11 (64.7) | 9 (47.4) |

| Remdesivir | 17 (47.2) | 8 (47.1) | 9 (47.4) |

| Received second tPA dose | 8 | N/A | 8 (42.1) |

| Position | . . . | . . . | . . . |

| Prone | 14 (38.9) | 7 (41.2) | 7 (36.8) |

| Supine | 16 (44.4) | 9 (52.9) | 7 (36.8) |

| Side | 4 (11.1) | 1 (5.9) | 3 (15.8) |

| Pao2 to Fio2 ratio | 112.3 (87.0-134.5) | 107.1 (85.0-128.9) | 113.3 (89.0-135.0) |

| NEWS2 score | 6.0 (5.0-9.0) | 6.0 (5.0-9.0) | 6.0 (5.0-9.0) |

| aPTT | 30.5 (27.5-33.7) | 30.0 (28.5-33.1) | 32.3 (26.3-34.9) |

| INR | 1.2 (1.1-1.3) | 1.3 (1.1-1.3) | 1.1 (1.1-1.2) |

| Fibrinogen, mg/dL | 685.0 (597.0-827.0) | 668.5 (599.5-843.0) | 685.0 (527.0-819.0) |

| D-dimer, ng/mL | 1,900.0 (1,089.0-4,800.0) | 1,900.0 (910.0-6,137.0) | 2,105.0 (1,169.5-4,294.0) |

Data are presented as No., No. (%), or median (interquartile range). aPTT = activated partial thromboplastin time; INR = international normalized ratio for prothrombin time; N/A = not applicable; NEWS2 = National Early Warning System 2; tPA = tissue plasminogen activator.

A preplanned subgroup analysis stratified by median D-dimer at baseline is presented. In ad hoc analyses, we also examined the aPTT time trends in each of the study groups to assess the role of heparin and trends in COVID-19 severity of enrolled patients during the trial. The trends were assessed statistically by the Cochran-Armitage trend test or by linear regression.

Role of the Funding Source

The funder of this investigator-initiated study (Genentech, Inc) had no role in the study design, data collection, analysis, interpretation, or manuscript preparation. Five authors (E. E. M., H. B. M., C. D. B., M. B. Y., and A. S.) served as the steering committee and had full access to the data.

Results

Figure 1 shows the Consolidated Standards for Reporting Trials diagram for patient eligibility and distribution, with the enrollment period spanning May 14, 2020, through March 3, 2021, at which time the trial was stopped for reaching the target enrollment (n = 50).

Phase 1

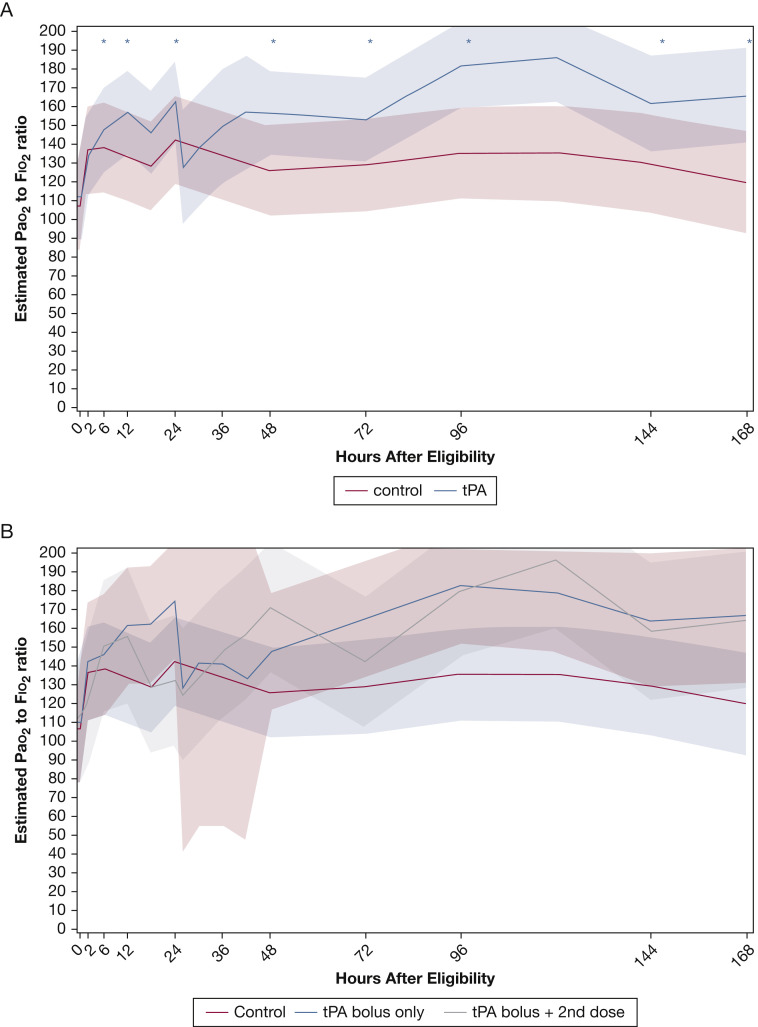

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the 36 patients enrolled during phase 1 (control group, n = 17; tPA bolus group, n = 19). Only minor imbalances were found between the two groups at baseline, with slightly more patients in the tPA bolus group being men and having concurrent infections (other than COVID-19) and being less likely to receive dexamethasone. All other baseline variables showed good balance, importantly including a similar baseline Pao 2 to Fio 2 ratio. Of the 19 patients receiving the tPA bolus intervention, 8 (42.1%) required a second tPA dose because of transient Pao 2 to Fio 2 ratio improvement as defined in the Methods. No patients crossed over or withdrew. As shown in Table 2 and Figure 2 , patients in the tPA bolus group showed a larger and statistically significant increase in Pao 2 to Fio 2 ratio relative to baseline at every time point measured (6, 12, 24, 48, 72, 96, 144, and 168 h after randomization), whereas control participants did not, resulting in more patients in the tPA bolus group reaching the composite outcome, although no significant differences were found in Pao 2 to Fio 2 ratios between groups at 48 h. No differences were found in National Early Warning System 2 scores over time between groups (Table 2). Observations between patients in the tPA bolus group and control participants with respect to VFD, ICU-free days, and in-hospital mortality did not reach significant differences. Control participants maintained significantly shorter aPTT than patients who received the tPA bolus (P < .001) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Outcomes for Phase 1

| Variable | Total | Control Group | tPA Bolus + Heparin Group | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | 36 | 17 | 19 | ... |

| Pao2 to Fio2 ratio | ||||

| At 24 h | 145.0 (110.5-193.5) | 146.7 (98.8-174.0) | 144.0 (122.9-217.1) | .5471 |

| % Improvement over baseline at 24 h | 39.7 (–4.9 to 72.1) | 37.0 (–6.4 to 64.5) | 44.4 (–3.4 to 78.0) | .6573 |

| At 48 h | 138.2 (105.0-181.0) | 125.0 (87.5-147.5) | 157.1 (130.0-188.0) | .0458 |

| % Improvement over baseline at 48 h | 24.6 (–1.5 to 59.8) | 16.9 (–8.3 to 36.8) | 29.8 (4.5-88.7) | .1131 |

| Composite outcome: Pao2 to Fio2 ratio % improvement at 48 h of > 50% or Pao2 to Fio2 ratio of ≥ 200 | 11 (30.6) | 2 (11.8) | 9 (47.4) | .0312 |

| Paralytics at 48 h | 18 (50.0) | 10 (58.8) | 8 (42.1) | .5051 |

| Position at 48 h | .8166 | |||

| Prone | 14 (38.9) | 6 (35.3) | 8 (42.1) | |

| Supine | 16 (44.4) | 9 (52.9) | 7 (36.8) | |

| Left side | 2 (5.6) | 1 (5.9) | 1 (5.3) | |

| Right side | 4 (11.1) | 1 (5.9) | 3 (15.8) | |

| NEWS2 score % increase over baseline at 48 h | 0.0 (–22.2 to 30.0) | 0.0 (–22.2 to 40.0) | 0.0 (–22.2 to 20.0) | .9241 |

| PTT, s | ||||

| At 24 h | 38.9 (32.7-58.6) | 32.9 (28.0-36.1) | 51.7 (36.9-65.6) | .0004 |

| At 48 h | 41.2 (30.0-65.6) | 30.0 (26.9-36.2) | 64.3 (55.7-73.6) | < .0001 |

| INR | ||||

| At 24 h | 1.2 (1.1-1.3) | 1.3 (1.2-1.3) | 1.2 (1.1-1.2) | .1521 |

| At 48 h | 1.2 (1.1-1.3) | 1.2 (1.1-1.3) | 1.2 (1.1-1.3) | .5685 |

| Fibrinogen, mg/dL | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| At 24 h | 613.0 (562.0-814.0) | 595.0 (521.0-828.0) | 627.0 (567.0-800.0) | .7513 |

| At 48 h | 586.0 (498.0-798.0) | 612.0 (450.0-817.0) | 567.0 (520.0-786.0) | .9725 |

| D-dimer, ng/mL | ||||

| At 24 h | 1,895.0 (969.0-4,422.0) | 1,426.0 (730.0-3,970.0) | 2,296.0 (1,330.0-9,700.0) | .0615 |

| At 48 h | 1,641.0 (900.0-3,450.0) | 1,326.0 (870.0-2,970.0) | 1,975.0 (1,010.0-3,650.0) | .4282 |

| Adverse event incidence | 26 (72.2) | 13 (76.5) | 13 (68.4) | .7169 |

| Bleeding event incidence | 5 (13.9) | 2 (11.8) | 3 (15.8) | 1.000 |

| Ventilation days | 14.0 (9.0-28.0) | 18.0 (9.0-28.0) | 13.0 (8.0-25.0) | .2088 |

| VFD | 0.0 (0.0-17.0) | 0.0 (0.0-9.0) | 12.0 (0.0-19.0) | .1064 |

| ICU days | 16.5 (11.5-28.0) | 18.0 (12.0-28.0) | 16.0 (11.0-28.0) | .8990 |

| IFD | 0.0 (0.0-14.0) | 0.0 (0.0-10.0) | 6.0 (0.0-15.0) | .4200 |

| Mortality | ||||

| In-hospital | 11 (30.6) | 7 (41.2) | 4 (21.1) | .1907 |

| 28-d | 9 (25.0) | 5 (29.4) | 4 (21.1) | .5631 |

Data are presented as No., No. (%), or median (interquartile range). IFD = ICU-free day; INR = international normalized ratio for prothrombin time; NEWS2 = National Early Warning System 2; PTT = partial thromboplastin time; tPA = tissue plasminogen activator; VFD = ventilation-free day.

Figure 2.

A, Graph showing Pao2 to Fio2 ratio over time in phase 1 estimates with 95% confidence bands based on the linear mixed model (interaction time × intervention; P = .14) for the tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) bolus vs control groups. Asterisks indicate significant (P < .017) differences compared with baseline. Only the tPA bolus group showed significant improvements in Pao2 to Fio2 ratio compared with baseline. No significant improvements in Pao2 to Fio2 ratio were found in the control group. B, Graph showing the Pao2 to Fio2 ratio, which is same as in (A), but further stratifying by requirement of a second tPA bolus at 24 h.

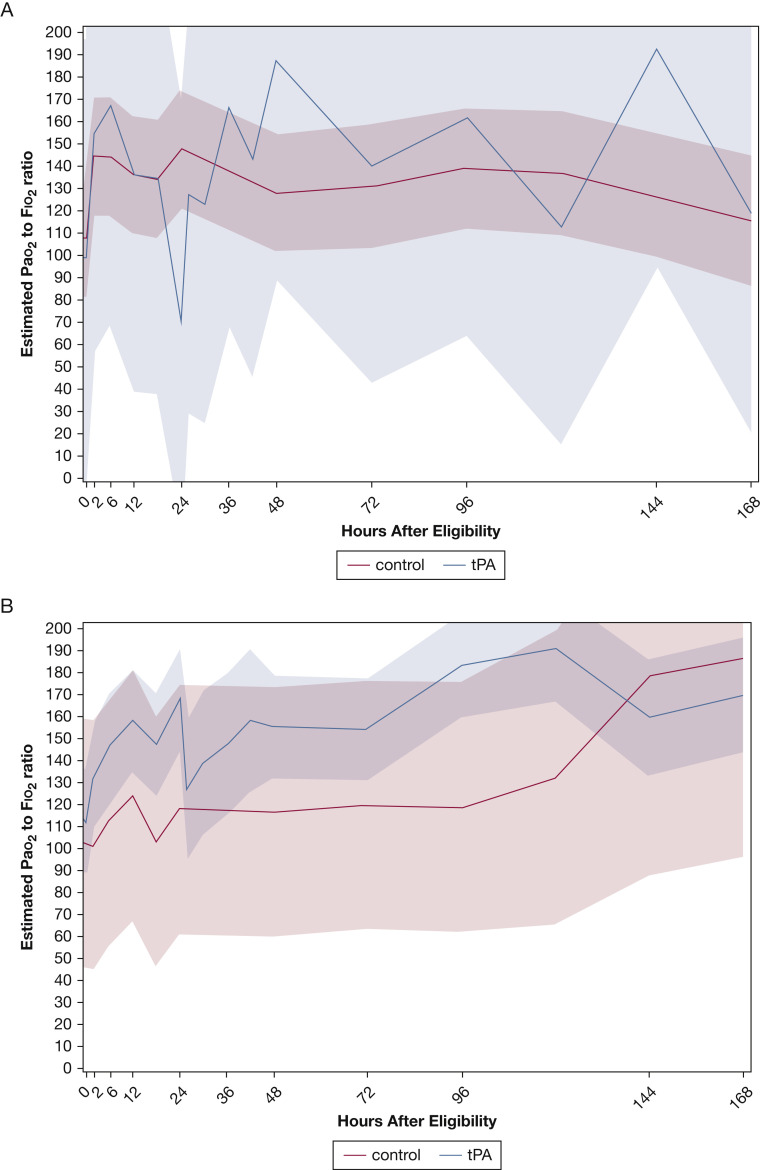

Stratification of the temporal trends of patients in the tPA bolus group by receipt of a second tPA dose at 24 h resulted in a second peak in the Pao 2 to Fio 2 ratio and sustained higher values for up to 7 days (Fig 2B). Further stratification by average aPTT over 7 days after randomization showed that among patients who maintained a 7-day average aPTT of > 40 s (the approximate median value at 48 h), tPA bolus recipients maintained consistently higher Pao 2 to Fio 2 ratios over time (Fig 3 A), which is in contrast to those patients whose 7-day average aPTT was ≤ 40 s (Fig 3B).

Figure 3.

A, B, Graphs showing the role of average activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) in Pao2 to Fio2 ratio temporal trends in phase 1: 7-day average aPTT ≤ 40 s (n = 15) (A) and 7-day average aPTT > 40 s (n = 21) (B).

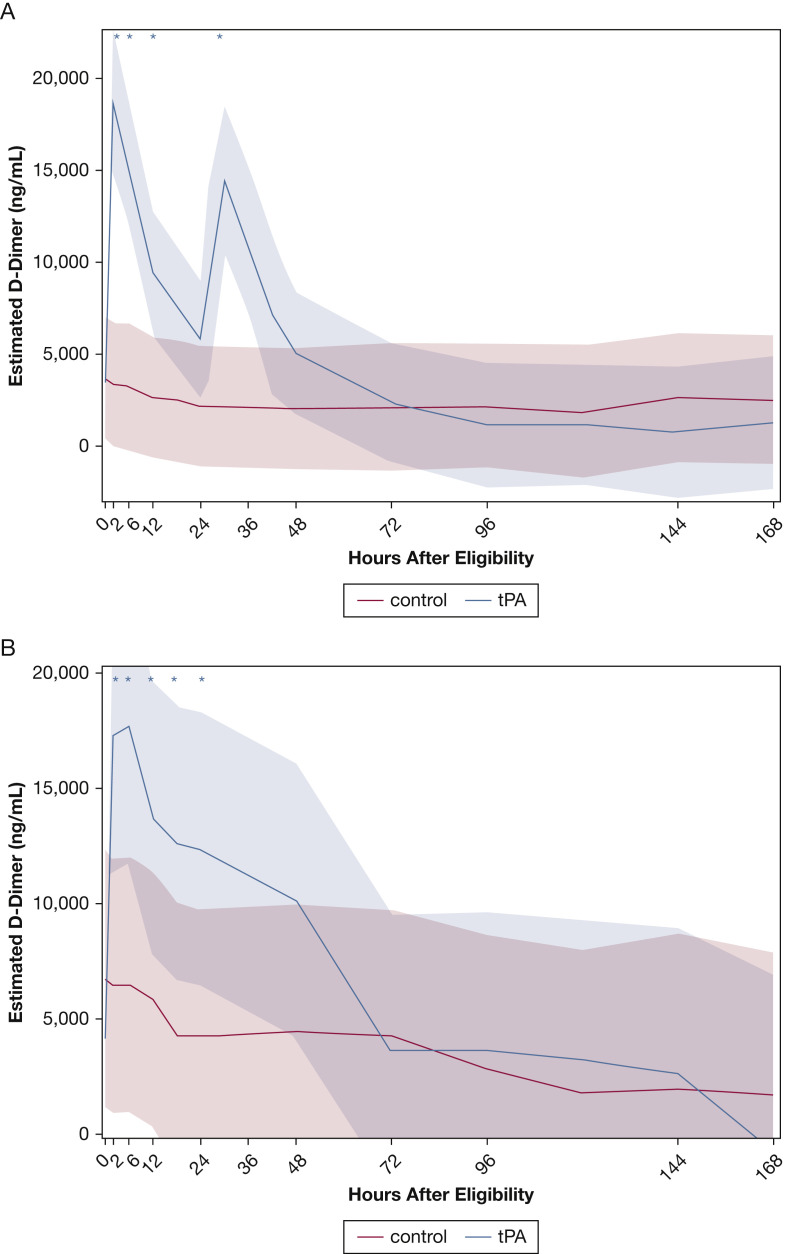

As anticipated, the temporal trends of D-dimer differed significantly between intervention and control participants (interaction intervention × time; P < .0001). The peak D-dimer levels (Fig 4 A) occurred immediately after completion of the 2-h bolus, whereas a second smaller peak (also significantly different than baseline) was seen at 36 h, consistent with a repeat tPA bolus in a large number of patients. However, baseline D-dimer levels (> 1,900 ng/mL vs ≤ 1,900 ng/mL, which was the median on randomization) did not modify the differences between patients who received a tPA bolus and control participants at 48 h or affect the temporal trends of these two study groups.

Figure 4.

A, B, Graphs showing D-dimer temporal trends by study group in phase 1 (A) and phase 2 (B). A, In phase 1 (tissue plasminogen activator [tPA] bolus vs control), the intervention significantly changed the temporal trends of the study groups (interaction intervention × time; P < .0001). Asterisks indicate significant (P < .003, adjusted for multiple comparisons by false-discovery rate) differences compared with baseline; only the tPA bolus group showed significant changes in D-Dimer levels compared with baseline. No significant changes in D-Dimer levels were found in the control group. B, In phase 2 (tPA drip vs control), the intervention changed (albeit not significantly at P < .017) the temporal trends of the study groups (interaction intervention × time; P < .013). Asterisks indicate significant (P < .003, adjusted for multiple comparisons by false-discovery rate) differences compared with baseline. Only the tPA drip group showed significant changes in D-dimer levels compared with baseline. No significant changes in D-dimer levels were found in the control group.

Phase 2

Table 3 shows the characteristics of the 14 patients enrolled during phase 2 (control group, n = 8; tPA drip group, n = 6). No major imbalances in baseline characteristics were noted. The tPA drip group did not show benefit compared with simultaneously enrolled control participants (Table 4 ). Of note, aPTT was short (< 40 s) in both study groups (tPA drip and control groups), further suggesting the pivotal role of therapeutic heparin in the intervention. Similar to the tPA bolus group, the tPA drip group demonstrated a large and significant spike in D-dimer levels immediately after initiation of tPA compared with control participants (Fig 4B). No severe, life-threatening, or fatal bleeding events occurred in the tPA drip group (Table 4, Table 5 ). Subgroup analyses in this phase were not informative because of the small sample size.

Table 3.

Baseline Characteristics of Phase 2

| Variable | Total | Control Group | tPA Drip + Heparin Group |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. | 14 | 8 | 6 |

| Age, y | 63.5 (56.0-66.0) | 60.5 (51.0-65.0) | 64.5 (62.0-68.0) |

| Male sex | 12 (85.7) | 6 (75.0) | 6 (100) |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 30.3 (27.7-35.4) | 30.9 (26.1-35.4) | 29.5 (27.7-36.1) |

| Days from admission to randomization | 1.5 (1.0-4.0) | 1.0 (0.5-1.5) | 5.0 (2.0-8.0) |

| Diabetes | 5 (35.7) | 3 (37.5) | 2 (33.3) |

| Cardiac disease | 1 (7.1) | 1 (12.5) | 0 |

| Hypertension | 8 (57.1) | 4 (50.0) | 4 (66.7) |

| COPD | 3 (21.4) | 0 | 3 (50.0) |

| Hyperlipidemia | 2 (14.3) | 1 (12.5) | 1 (16.7) |

| Other comorbidity | 9 (64.3) | 5 (62.5) | 4 (66.7) |

| Infections | 9 (64.3) | 5 (62.5) | 4 (66.7) |

| Dexamethasone | 6 (46.2) | 3 (42.9) | 3 (50.0) |

| Remdesivir | 3 (23.1) | 2 (28.6) | 1 (16.7) |

| Position | |||

| Prone | 8 (57.1) | 6 (75.0) | 2 (33.3) |

| Supine | 3 (21.4) | 1 (12.5) | 2 (33.3) |

| Side | 3 (21.4) | 1 (12.5) | 2 (33.3) |

| Pao2 to Fio2 ratio | 99.5 (77.0-128.3) | 99.5 (75.5-123.9) | 109.7 (77.0-132.9) |

| NEWS2 score | 7.5 (5.0-10.0) | 10.0 (7.5-11.0) | 6.0 (5.0-7.0) |

| aPTT, s | 31.1 (27.0-33.7) | 31.1 (27.0-33.7) | 31.0 (26.7-41.3) |

| INR | 1.2 (1.0-1.3) | 1.3 (1.1-1.3) | 1.1 (1.0-1.3) |

| Fibrinogen, mg/dL | 695.0 (560.0-870.0) | 560.0 (507.0-992.0) | 695.5 (692.0-717.0) |

| D-dimer, ng/mL | 3,940.0 (1,364.0-5,510.0) | 4,180.0 (1,434.0-9,170.0) | 2,652.0 (963.0-5,510.0) |

Data are presented as No., No. (%), or median (interquartile range). aPTT = activated partial thromboplastin time; INR = international normalized ratio for prothrombin time; NEWS2 = National Early Warning System 2; tPA = tissue plasminogen activator.

Table 4.

Outcomes in Phase 2

| Variable | Total | Control Group | tPA Drip + Heparin Group | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | 14 | 8 | 6 | ... |

| Pao2 to Fio2 ratio | ||||

| At 24 h | 114.1 (87.1-124.0) | 119.2 (111.9-131.3) | 94.5 (71.0-114.5) | .0814 |

| % Improvement over baseline at 24 h | 14.5 (–19.5 to 45.8) | 19.9 (–0.3 to 80.8) | –16.7 (–37.4 to 36.5) | .1376 |

| At 48 h | 104.5 (84.3-116.7) | 113.7(88.8-160.0) | 103.5(78.8-105.0) | .4014 |

| % Improvement over baseline at 48 h | –19.6 (–22.6 to 101.9) | –11.9 (–24.3 to 136.1) | –19.6 (–21.7 to 2.3) | .7469 |

| Composite outcome: Pao2 to Fio2 ratio % improvement at 48 h of > 50% or Pao2 to Fio2 ratio of ≥ 200 | 4 (28.6) | 3 (37.5) | 1 (16.7) | .5804 |

| Paralytics at 48 h | 10 (71.4) | 6 (75.0) | 4 (66.7) | 1.0000 |

| Position at 48 h | .8601 | |||

| Prone | 7 (50.0) | 3 (37.5) | 4 (66.7) | |

| Supine | 4 (28.6) | 3 (37.5) | 1 (16.7) | |

| Left side | 2 (14.3) | 1 (12.5) | 1 (16.7) | |

| Right side | 1 (7.1) | 1 (12.5) | ... | |

| NEWS2 score % increase over baseline at 48 h | 0.0 (–25.0 to 60.0) | –12.5 (–26.8 to 18.8) | 65.7 (0.0-80.0) | .0794 |

| PTT, s | ||||

| At 24 h | 30.5 (26.9-38.8) | 35.6 (29.0-51.2) | 27.7 (26.8-30.0) | .1752 |

| At 48 h | 34.4 (28.5-73.4) | 53.1 (28.5-95.9) | 33.0 (28.5-57.4) | .5181 |

| INR | ||||

| At 24 h | 1.1 (1.0-1.2) | 1.1 (1.0-1.3) | 1.1 (1.0-1.2) | .7453 |

| At 48 h | 1.2 (1.1-1.4) | 1.2 (1.1-1.3) | 1.2 (1.1-1.4) | .9477 |

| Fibrinogen, mg/dL | ||||

| At 24 h | 606.0 (474.0-822.0) | 588.5 (441.0-768.0) | 612.0 (542.0-822.0) | .8465 |

| At 48 h | 564.5 (420.0-706.0) | 480.5 (395.5-638.5) | 698.5 (542.0-821.0) | .1748 |

| D-dimer, ng/mL | ||||

| At 24 h | 5,420.0 (3,320.0-11,510) | 3,855.0 (1,996.0-8,500.0) | 8,477.0 (5,540.0-11,510) | .1066 |

| At 48 h | 4,060.5 (3,460.0-5,890.0) | 3,480.5 (2,713.5-4,750.0) | 4,957.5 (4,261.0-7,650.0) | .0612 |

| Adverse event incidence | 7 (50.0) | 5 (62.5) | 2 (33.3) | .5921 |

| Bleeding event incidence | 1 (7.1) | 1 (12.5) | 0 | 1.000 |

| Ventilation days | 20.5 (16.0-26.0) | 24.5 (12.0-27.0) | 17.5 (16.0-25.0) | .6979 |

| VFD | 0.0 (0.0-0.0) | 0.0 (0.0-1.0) | 0.0 (0.0-0.0) | .9284 |

| ICU days | 22.5 (17.0-29.0) | 27.0 (12.0-30.5) | 19.0 (17.0-25.0) | .6982 |

| IFD | 0.0 (0.0-0.0) | 0.0 (0.0-0.0) | 0.0 (0.0-0.0) | .3123 |

| Mortality | ||||

| In-hospital | 9 (64.3) | 4 (50.0) | 5 (83.3) | .1977 |

| 28-d | 8 (57.1) | 4 (50.0) | 4 (66.7) | .5329 |

Data are presented as No., No. (%), or median (interquartile range). IFD = ICU-free day; INR = international normalized ratio for prothrombin time; NEWS2 = National Early Warning System 2; PTT = partial thromboplastin time; tPA = tissue plasminogen activator; VFD = ventilation-free day.

Table 5.

Adverse Events by Study Group and Severity Grade

| Variable | Study Group |

Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control (n = 25) | tPA Bolus (n = 19) | tPA Drip (n = 6) | ||

| Severity grade 5 | ||||

| Arrest | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Liver failure | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Renal failure | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Worsening of lung function | 4 | 3 | 1 | 8 |

| Total no. of events | 6 | 3 | 3 | 12 |

| No. of participants | 6 | 3 | 1 | 10 |

| % of participants | 24.0 | 12.0 | 4.0 | 40.0 |

| Severity grade 4 | ||||

| Cardiac arrhythmia | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Failed extubation | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Hyperkalemia | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Hypotension | 2 | 1 | 0 | 3 |

| Liver failure | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Multiple organ failure | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Peritonitis | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Pneumonia | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Septic shock | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Worsening of lung function | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| Total no. of events | 12 | 2 | 2 | 16 |

| No. of participants | 5 | 2 | 1 | 8 |

| % of participants | 20.0 | 8.0 | 4.0 | 32.0 |

| Severity grade 3 | ||||

| Candidiasis | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Cardiac arrhythmia | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Delirium | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Deep venous thrombosis | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Hypervolemia | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Hypotension | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Ileus | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Pulmonary embolism | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| Pneumonia | 1 | 2 | 0 | 3 |

| Renal failure | 4 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| Septic shock | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Urinary tract infection | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| Worsening of lung function | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Total no. of events | 12 | 9 | 0 | 21 |

| No. of participants | 8 | 6 | 0 | 14 |

| % of participants | 32.0 | 24.0 | 0 | 56.0 |

| Severity grade 2 | ||||

| Acidosis (respiratory) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Alkalosis, metabolic or respiratory | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Aspiration | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| Bacteremia | 2 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| Bleeding abdominal | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Bleeding hemoptysis | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Bleeding rectal tear | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Bleeding urinary | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Candidiasis | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Cardiac arrhythmia | 1 | 2 | 0 | 3 |

| Delirium | 2 | 1 | 0 | 3 |

| Diarrhea | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Deep venous thrombosis | 3 | 1 | 0 | 4 |

| EBV | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Failure to wean off ventilation | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Fracture | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| HSV | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Hyperfibrinogenemia | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Hyperglycemia | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Hyperkalemia | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Hypervolemia | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| Hypotension | 2 | 1 | 0 | 3 |

| Myopathy | 2 | 1 | 0 | 3 |

| Pleural effusion | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Pneumonia | 4 | 2 | 0 | 6 |

| Pneumothorax | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Renal failure | 0 | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| Sepsis | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Thrombosis arterial | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Tongue edema | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Urinary retention | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Urinary tract infection | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Worsening of lung function | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Total no. of events | 34 | 17 | 6 | 57 |

| No. of participants | 14 | 6 | 3 | 23 |

| % of participants | 56.0 | 24.0 | 12.0 | 92.0 |

| Severity grade 1 | ||||

| Agitation | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Alkalosis, metabolic | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Anemia | 5 | 4 | 0 | 9 |

| Aspiration | 2 | 1 | 0 | 3 |

| Bacteremia | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Benzodiazepine or opiate withdrawal | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Biliary dilation | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Bleeding nasal | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Bleeding oral | 2 | 2 | 0 | 4 |

| Bleeding vaginal | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Bronchial obstruction | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Cardiac arrhythmia | 2 | 3 | 0 | 5 |

| Constipation | 2 | 4 | 0 | 6 |

| Dehydration | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Delirium | 4 | 2 | 0 | 6 |

| Diarrhea | 1 | 2 | 0 | 3 |

| DVT | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Dysphagia | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Dysphonia | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Encephalopathy | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Eosinophilia | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| Facial edema | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Fall | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Fever | 7 | 2 | 1 | 10 |

| Hyperglycemia | 3 | 1 | 0 | 4 |

| Hyperkalemia | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Hypernatremia | 2 | 3 | 0 | 5 |

| Hypertension | 2 | 2 | 0 | 4 |

| Hypervolemia | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Hypoglycemia | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Hypokalemia | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Hyponatremia | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Hypotension | 5 | 1 | 0 | 6 |

| Hypovolemia | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Ileus | 1 | 3 | 0 | 4 |

| Leukocytosis | 2 | 3 | 0 | 5 |

| Myopathy | 4 | 4 | 0 | 8 |

| Paraphimosis | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Pleural effusion | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Pneumatocele | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Pneumonia | 2 | 3 | 1 | 6 |

| Pressure ulcer | 1 | 2 | 0 | 3 |

| Pulmonary hypertension | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Rash | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Renal failure | 2 | 2 | 0 | 4 |

| Renal tubular acidosis | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Sinusitis | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Thrombocytosis | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Thrombocytosis | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Transaminitis | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| Urinary retention | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Urinary tract infection | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Vomit | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Worsening of lung function | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Total no. of events | 73 | 70 | 3 | 146 |

| No. of participants | 11 | 11 | 2 | 24 |

| % of participants | 44.0 | 44.0 | 8.0 | 96.0 |

Severity grade: 1 = mild to 5 = life threatening or fatal; includes death only as a consequence of an adverse event. EBV = Epstein-Barr virus; HPV = herpes simplex virus; tPA = tissue plasminogen activator.

Adverse Events

No severe, life-threatening, or fatal bleeding events occurred in the tPA bolus group (Table 2, Table 5) or in the tPA drip group (Table 4, Table 5).

Evolution of COVID-19 Severity Over the Duration of the Trial

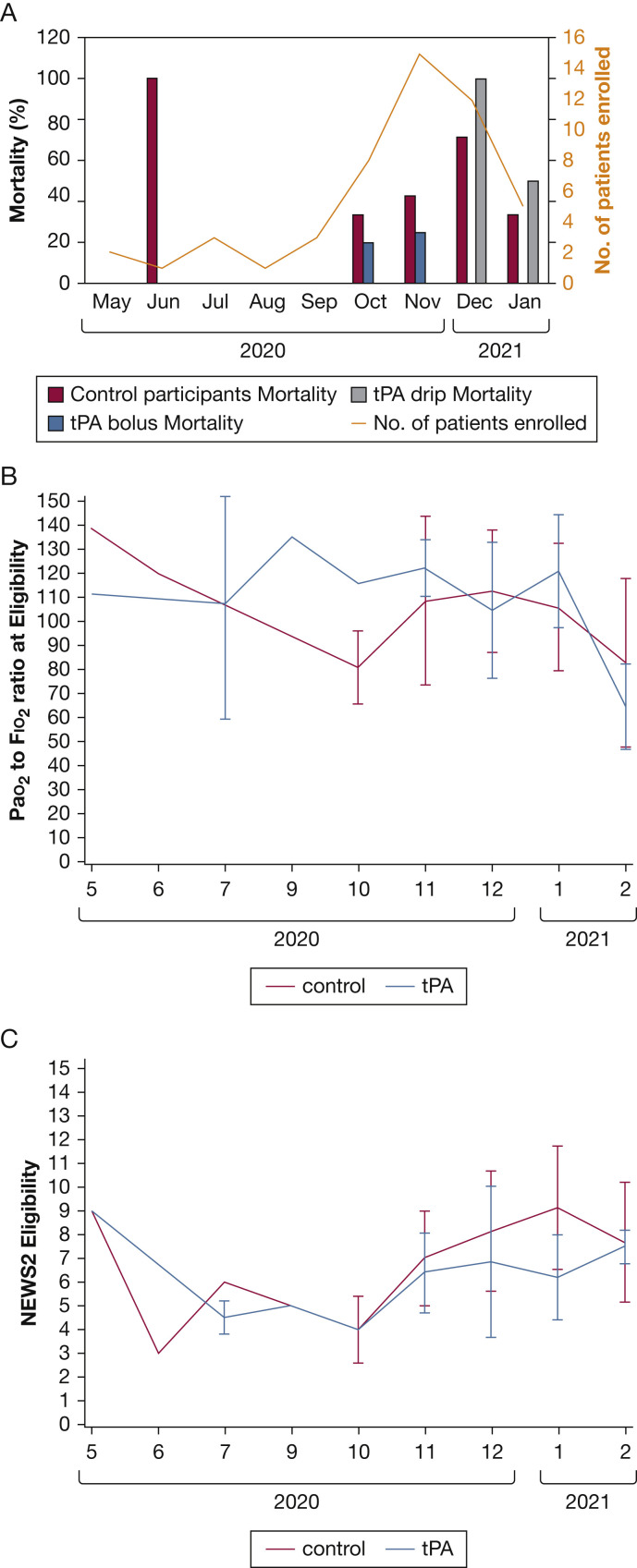

Over the duration of the trial, we documented a change in the COVID-19 severity among the eligible patients. Figure 5 A shows the monthly mortality by study group over the duration of the trial, which increased significantly over time (P = .02, Cochran-Armitage trend test). The Pao 2 to Fio 2 ratio on enrollment did not show a significant change over time (Fig 5B) (R 2 = 0.05; P = .13), nor did the National Early Warning System 2 score (Fig 5C) (R 2 = 0.06; P = .08).

Figure 5.

A-C, Graphs showing trends in disease severity during the trial: mortality (A), Pao2 to Fio2 ratio at eligibility (B), and NEWS2 score at eligibility (C). NEWS2 = National Early Warning System 2; tPA = tissue plasminogen activator.

Discussion

The results of this trial show that the use of tPA (alteplase) as a bolus with immediate therapeutic anticoagulation after its administration for severe COVID-19 respiratory failure is safe and seems to improve oxygenation over baseline in a sustained fashion (from 6 through 168 h after randomization), whereas the control group did not show any significant improvement at any time. The trial was markedly underpowered to detect significant differences in clinically important parameters like VFD and in-hospital mortality, so not surprisingly, no significant differences were found in these outcomes. The trial’s power to detect differences was reduced further by a late-stage adaptation. Although not significantly different, the observation that the tPA bolus group had a median of 12 VFDs, whereas the control group had a median of 0 VFDs, was a large effect-size signal that persisted at every interim analysis during the trial. The same is true of in-hospital mortality, where the trial was unable to detect significant differences between the tPA bolus group and control participants, but the low in-hospital mortality observed for the tPA bolus group, at just 21%, was a promisingly low rate for patients with such severe COVID-19 respiratory failure.

These findings are of elevated clinical significance during a global pandemic of a disease with high morbidity and mortality. Of particular importance is safety: no major bleeding events occurred, including intracranial hemorrhage, that were associated with tPA and heparin, answering an important question for future investigations and clinical use. The safe outcomes likely were aided by careful selection, because a nonfocal neurologic examination or cross-sectional brain imaging was required within the preceding 4.5 h before enrollment to rule out a stroke before use of tPA, in addition to ensuring no laboratory or medical findings that posed unacceptable increased risk of bleeding before enrollment.

In COVID-19 respiratory failure, a substantial contribution of microvascular thrombosis and occlusion leading to dead space ventilation seems to exist.1, 2, 3, 4 This would explain the findings reported by Gattinoni et al11 and others observing relatively preserved lung compliance despite profound respiratory failure early in the course of disease and also would explain the results of the ACTIV-4a/ATTACC/REMAP-CAP trial that therapeutic heparin therapy is beneficial only if initiated early before decompensation requiring MV (ie, before too much of the pulmonary microvasculature clots off).12 These observations support our findings of improved oxygenation with tPA bolus plus therapeutic heparin, because therapeutic heparinization alone cannot re-establish vascular patency and reduce dead space ventilation after the microvasculature is clotted off; thrombolysis is required to accomplish this. It is also noteworthy that a significant spike in D-dimer levels was observed in the tPA bolus group that temporally aligned with dosing of tPA (and repeat dosing of tPA), verifying that we accomplished lysis of a mature, cross-linked clot just as hypothesized.

In contrast to the tPA bolus group, the tPA drip group achieved no benefit. The major limitation of these findings is that they are based on six patients at a different time of the pandemic, when mortality rates in the control group also were increasing. Moreover, an important protocol difference in the tPA drip group was the low-dose or subtherapeutic heparin infusion during the 24-h tPA drip that resulted in consistently short aPTT values. In phase 1 of the trial, the highest benefit of the tPA bolus was observed among patients for whom the heparin regimen resulted in longer aPTT values. This raises the possibility that, in the tPA drip group, any revascularization effect of the initial tPA bolus before the drip ensued was lost by the lack of therapeutic anticoagulation during the low-dose tPA infusion over those subsequent 24 h. This is supported by the coagulation data, where the aPTT at 24 h essentially was within normal limits in the tPA drip group, whereas the unfractionated heparin infusion and aPTT values in the tPA bolus group were fully therapeutic at that time. Thus, rethrombosis of the microvasculature resulting from subtherapeutic heparin could explain failure to improve in the tPA drip group.

This study has a number of important limitations, in large part because of funding restrictions. First, it was underpowered to detect significant differences between most of the clinically important outcomes. Second, the standard-of-care treatment of patients with COVID-19 changed over the duration of the trial, although the randomization process would be expected to have controlled for these changes. Additionally, three of the eight enrolling centers made up more than half of the enrollments and could have impacted the outcomes, despite a relatively even randomization. Finally, this was an open-label study; thus, it is possible that the primary treatment teams changed portions of the care for patients receiving tPA that could have impacted the trial outcomes.

Interpretation

In summary, bolus dosing of tPA with immediate therapeutic heparin anticoagulation in well-selected patients with severe COVID-19 respiratory failure is safe and improves oxygenation. The trial was underpowered to detect differences in clinical outcomes like VFD and in-hospital mortality, although the observations in these outcomes were promising. A phase 3 study is warranted.

Take-home Points.

StudyQuestion: Does fibrinolytic therapy with tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) improve pulmonary function in severe COVID-19 respiratory failure, and is it safe, specifically with respect to bleeding, in this setting?

Results: The tPA bolus group showed improved oxygenation with no intracranial hemorrhages, and additional promising observations were noted in ventilator-free days and mortality.

Interpretation: The Study of Alteplase for Respiratory Failure in SARS-CoV-2 COVID-19 trial provides the first known prospective evidence of potential benefit of fibrinolytic therapy in COVID-19 respiratory failure with an acceptable risk profile when patients are selected carefully.

Acknowledgments

Author contributions: E. E. M. is the author responsible for the content of the manuscript. C. D. B., H. B. M., E. E. M., A. S., and M. B. Y. had access to all data and contributed to all components of the study and manuscript generation. All other Study of Alteplase for Respiratory Failure in SARS-CoV-2 COVID-19 authors meet at least the minimum three criteria for CHEST authorship.

Financial/nonfinancial disclosures: The authors have reported to CHEST the following: C. D. B., H. B. M., E. E. M., and M. B. Y. have patents pending related to both coagulation and fibrinolysis diagnostics and therapeutic fibrinolytics and are passive co-founders and hold stock options in Thrombo Therapeutics, Inc. H. B. M. and E. E. M. have received grant support from Haemonetics and Instrumentation Laboratories. M. B. Y. previously received a gift of Alteplase (tPA) from Genentech and owns stock options as a cofounder of Merrimack Pharmaceuticals. C. D. B., H. B. M., E. E. M., J. W., N. H., D. S. T., A. S., and M. B. Y. have received research grant funding from Genentech. J. W. receives consulting fees from Camurus A. B. None declared (W. L. B., L. L., P. R. P., M. S. T., R. M., T. M. B., L. A. A., A. G., J. C., I. D., E. S., P. K. M., F. L. W., R. R., R. B., M. R., A. D., D. S. M., T. D., P. K. S., B. K., C. S., C. M., H. M. G. V., C. P., L. A.-B., E. N. B.-K., R. J., S. S., K. C., V. B.-G.).

Role of sponsors: The funder of this investigator-initiated study (Genentech, Inc.) had no role in the study design, data collection, analysis, interpretation, or manuscript preparation. Five authors (E. E. M., H. B. M., C. D. B, M. B. Y., and A. S.) served as the steering committee and had full access to the data.

Additional information: The e-Appendixes can be found in the Supplemental Materials section of the online article.

Footnotes

Drs Barrett and H. B. Moore contributed equally to this manuscript as co-first authors.

Drs E. E. Moore and Yaffe contributed equally to this manuscript as co-corresponding authors.

Supplementary Data

References

- 1.Ciceri F., Beretta L., Scandroglio A.M., et al. Microvascular COVID-19 lung vessels obstructive thromboinflammatory syndrome (MicroCLOTS): an atypical acute respiratory distress syndrome working hypothesis. Crit Care Resusc. 2020;22(2):95–97. doi: 10.51893/2020.2.pov2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dolhnikoff M., Duarte-Neto A.N., de Almeida Monteiro R.A., et al. Pathological evidence of pulmonary thrombotic phenomena in severe COVID-19. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(6):1517–1519. doi: 10.1111/jth.14844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wichmann D., Sperhake J.P., Lutgehetmann M., et al. Autopsy findings and venous thromboembolism in patients with COVID-19: a prospective cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173(4):268–277. doi: 10.7326/M20-2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fox S.E., Akmatbekov A., Harbert J.L., Li G., Quincy Brown J., Vander Heide R.S. Pulmonary and cardiac pathology in African American patients with COVID-19: an autopsy series from New Orleans. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8(7):681–686. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30243-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Panigada M., Bottino N., Tagliabue P., et al. Hypercoagulability of COVID-19 patients in intensive care unit: a report of thromboelastography findings and other parameters of hemostasis. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(7):1738–1742. doi: 10.1111/jth.14850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roh D.J., Eiseman K., Kirsch H., et al. Hypercoagulable viscoelastic blood clot characteristics in critically ill coronavirus disease 2019 patients and associations with thrombotic complications. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2021;90(1):e7–e12. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000002963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wright FL Vogler T.O., Moore E.E., et al. Fibrinolysis shutdown correlates to thromboembolic events in severe COVID-19 infection. J Am Coll Surg. 2020;231(2):193–203. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2020.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Slomka A., Kowalewski M., Zekanowska E. Hemostasis in coronavirus disease 2019—lesson from viscoelastic methods: a systematic review. Thromb Haemost. 2021;121(9):1181–1192. doi: 10.1055/a-1346-3178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Creel-Bulos C., Auld S.C., Caridi-Scheible M., et al. Fibrinolysis shutdown and thrombosis in a COVID-19 ICU. Shock. 2021;55(3):316–320. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0000000000001635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hightower S., Ellis H., Collen J., et al. Correlation of indirect markers of hypercoagulability with thromboelastography in severe coronavirus 2019. Thromb Res. 2020;195:69–71. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gattinoni L., Coppola S., Cressoni M., Busana M., Rossi S., Chiumello D. COVID-19 does not lead to a “typical” acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;201(10):1299–1300. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202003-0817LE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.ATTACC Investigators, ACTIV-4a Investigators, REMAP-CAP Investigators, et al. Therapeutic anticoagulation with heparin in noncritically ill patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:777–789. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2105911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barrett C.D., Moore H.B., Moore E.E., et al. Fibrinolytic therapy for refractory COVID-19 acute respiratory distress syndrome: scientific rationale and review. Res Pract Thromb Haemost. 2020;4(4):524–531. doi: 10.1002/rth2.12357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moore H.B., Barrett C.D., Moore E.E., et al. Is there a role for tissue plasminogen activator as a novel treatment for refractory COVID-19 associated acute respiratory distress syndrome? J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2020;88(6):713–714. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000002694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barrett C.D., Moore H.B., Yaffe M.B., Moore E.E. ISTH interim guidance on recognition and management of coagulopathy in COVID-19: a comment. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(8):2060–2063. doi: 10.1111/jth.14860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hardaway R.M., Drake D.C. Prevention of “irreversible” hemorrhagic shock with fibrinolysin. Ann Surg. 1963;157:39–47. doi: 10.1097/00000658-196301000-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hardaway R.M., Harke H., Tyroch A.H., Williams C.H., Vazquez Y., Krause G.F. Treatment of severe acute respiratory distress syndrome: a final report on a phase I study. Am Surg. 2001;67(4):377–382. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang J., Hajizadeh N., Moore E.E., et al. Tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) treatment for COVID-19 associated acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS): a case series. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(7):1752–1755. doi: 10.1111/jth.14828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Poor H.D., Ventetuolo C.E., Tolbert T., et al. COVID-19 critical illness pathophysiology driven by diffuse pulmonary thrombi and pulmonary endothelial dysfunction responsive to thrombolysis. Clin Transl Med. 2020;10(2):e44. doi: 10.1002/ctm2.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Christie D.B., III, Nemec H.M., Scott A.M., et al. Early outcomes with utilization of tissue plasminogen activator in COVID-19-associated respiratory distress: a series of five cases. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2020;89(3):448–452. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000002787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Orfanos S., El Husseini I., Nahass T., Radbel J., Hussain S. Observational study of the use of recombinant tissue-type plasminogen activator in COVID-19 shows a decrease in physiological dead space. ERJ Open Res. 2020;6(4):00455-2020–02020. doi: 10.1183/23120541.00455-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abou-Ismail M.Y., Diamond A., Kapoor S., Arafah Y., Nayak L. The hypercoagulable state in COVID-19: incidence, pathophysiology, and management. Thromb Res. 2020;194:101–115. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.06.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moore H.B., Barrett C.D., Moore E.E., et al. STudy of Alteplase for Respiratory failure in SARS-Cov2/COVID-19: study design of the phase IIa STARS Trial. Res Pract Thromb Haemost. 2020;4(6):984–996. doi: 10.1002/rth2.12395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brown S.M., Grissom C.K., Moss M., et al. Nonlinear imputation of Pao2/Fio2 from Spo2/Fio2 among patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Chest. 2016;150(2):307–313. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2016.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schoenfeld D.A., Bernard G.R. Statistical evaluation of ventilator-free days as an efficacy measure in clinical trials of treatments for acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care Med. 2002;30(8):1772–1777. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200208000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cohen D.R., Todd S., Gregory W.M., Brown J.M. Adding a treatment arm to an ongoing clinical trial: a review of methodology and practice. Trials. 2015;16(1):179. doi: 10.1186/s13063-015-0697-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rothman K.J. No adjustments are needed for multiple comparisons. Epidemiology. 1990;1(1):43–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Perneger T.V. 1998. What’s wrong with Bonferroni adjustments. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.