Abstract

Background

Substance use disorder (SUD) treatment use is low in the United States. We assessed differences in treatment use and perceived need by sexual identity (i.e., lesbian, gay, bisexual, heterosexual) and gender among adults with a past-year SUD.

Methods

We pooled data from the 2015-2019 National Survey on Drug Use and Health for adults (18+) who met past-year DSM-IV SUD criteria and self-reported sexual identity (n = 21,926). Weighted multivariable logistic regressions estimated odds of past-year: 1) any SUD treatment; 2) specialty SUD treatment; 3) perceived SUD treatment need by sexual identity, stratified by gender and adjusted for socio-demographics.

Results

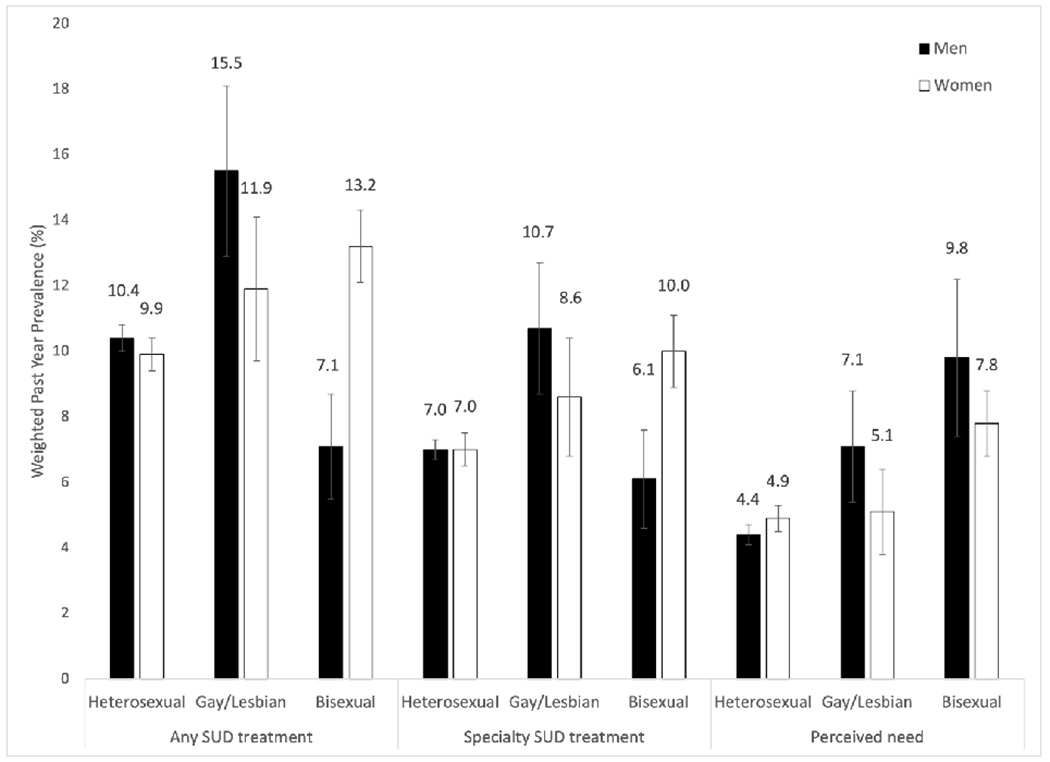

Any past-year SUD treatment use was low among adult men (heterosexual [10.4%], gay [15.5%], and bisexual [7.1%]) and women (heterosexual [9.9%], gay/lesbian [11.9%], and bisexual [13.2%]). Patterns were similar for specialty SUD treatment and perceived treatment need. Adjusted odds of any SUD treatment use were higher among gay men (aOR = 1.65 [95% Confidence Interval 1.10-2.46]) and bisexual women (aOR = 1.31 [1.01-1.69]) than their heterosexual peers. Compared to their heterosexual counterparts, adjusted odds of perceived SUD treatment need were higher among bisexual women (aOR = 1.65 [1.22-2.25]), gay men (aOR = 1.76 [1.09-2.84]), and bisexual men (aOR = 2.39 [1.35-4.24]).

Conclusions

Most adults with SUD did not receive treatment. Gay men and bisexual women were more likely to receive treatment and reported higher perceived SUD treatment need than heterosexual peers. Facilitating treatment access and engagement is needed to reduce unmet needs among marginalized people who perceive SUD treatment need.

Keywords: Substance use disorder; Sexual identity; Gender, disparities; Treatment use; Perceived need for treatment

1. Introduction

Substance use disorders (SUDs) are a major public health concern in the United States (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), 2016). In 2019, 7.7% of the population 18 years or older, or 19.3 million people, reported any SUD in the past year (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2020a, 2020b). Despite the high prevalence of SUD in the United States, SUD treatment use prevalence is low (Blanco et al., 2015; Mauro et al., 2020; Olfson et al., 1998; Wang et al., 2005). In 2019, only 10.3% of adults needing SUD treatment received it (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2020a). Sexual minority adults (i.e., individuals who identify as lesbian, gay, or bisexual) report disproportionately high levels of SUDs in the past-year (i.e., 15.1%, compared to 7.8% of sexual majority adults (Medley et al., 2006). For example, bisexual women have a five-fold higher prevalence of alcohol use disorder than heterosexual women (Allen and Mowbray, 2016; Hughes, 2011; Schuler et al., 2018), and some SUDs are also more prominent among sexual minority men than heterosexual men, in spite of similar patterns of substance use (Schuler et al., 2018; Schuler and Collins, 2020). Sexual minority adults could therefore have higher need for SUD-related services, but information on SUD treatment utilization and perceived need among sexual minority adults remains limited.

Minority stress theory can be applied to explain disparities in SUD burden among sexual minority adults, with potential implications for SUD treatment uptake. This theory states that sexual minority individuals are uniquely impacted by stigma, discrimination, and victimization due to their sexual minority status (Feinstein and Dyar, 2017; Meyer, 2003). Exposure to stressors like sexual orientation discrimination has a detrimental effect on population health (Bränström and Pachankis, 2018; Frost et al., 2015; Hatzenbuehler and Pachankis, 2016), including SUDs among sexual minority populations (McCabe et al., 2010). Sexual minority adults disproportionately face SUD treatment barriers compared to heterosexual adults, including healthcare discrimination, under-insurance, and issues accessing substance use treatment (Haney, 2020; McCabe et al., 2010; Pennay et al., 2018). Minority stressors could decrease healthcare utilization in spite of perceived need for care, especially if individuals avoid treatment due to fear of disclosing their sexual identity to a provider due to anticipated stigma (Whitehead et al., 2016). The disproportionate SUD burden and treatment barriers among sexual minority adults highlight the urgent need to examine whether similar disparities exist in their patterns of treatment utilization.

While few substance use treatment programs report tailored programs for sexual minority adults (Williams and Fish, 2020), sexual minority adults with lifetime SUDs are more likely to enter SUD treatment compared to heterosexual adults (Allen and Mowbray, 2016; McCabe et al., 2013). At the same time, sexual minority adults who enter treatment do so with more severe SUDs than their heterosexual counterparts (Green and Feinstein, 2012), which could be a product of differences in the barriers (Haney, 2020) and facilitators that contribute to treatment use. One such facilitator is perceived treatment need, which is associated with subsequent treatment-seeking behaviors among adults overall (Mojtabai and Crum, 2013). However, less is known about perceived need for SUD treatment among sexual minority adults. Examining both SUD treatment utilization and perceived treatment need by sexual identity and gender in the past year, not just lifetime, is necessary to identify and address potential unmet SUD treatment needs among a particularly marginalized population. However, the few studies examining disparities in SUD treatment and perceived need either utilized older national survey data as well as lifetime measures of substance use and substance use treatment utilization (Allen and Mowbray, 2016; McCabe et al., 2013), or focused solely on barriers to treatment among people who perceived a need (Haney, 2020), limiting our understanding of potential disparities in treatment-related outcomes.

The current study aimed to address a gap in our understanding of both SUD treatment utilization and perceived need among sexual minority adults with SUDs compared to their heterosexual peers. We used the most recent data available from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) to test the hypothesis that sexual minority adults with a past-year SUD would have higher perceived need for SUD treatment and higher odds of receiving any type of SUD treatment than heterosexuals in the past year. By assessing both SUD treatment use and perceived need, our findings can help provide a more comprehensive picture of the SUD treatment gap among sexual minority adults.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design

The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) sponsors the NSDUH, an annual cross-sectional survey that collects data on substance use among a nationally representative household sample of individuals 12 years and older across all 50 states and the District of Columbia. The weighted interview response rates for individuals aged 18 and older were 64.2%-68.4% for 2015-2019 (Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, 2020, 2016). Participants were interviewed in person using computer-assisted interviewing (CAI) after providing informed consent and were compensated $30. Potentially sensitive questions were asked via audio computer-assisted self-interviewing (ACASI). NSDUH sample selection and survey weighting are described elsewhere (Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, 2020, 2016).

2.2. Study sample

We pooled five years of publicly available NSDUH data to increase power to detect differences by gender and sexual identity: 2015 (n = 57,146), 2016 (n = 56,897), 2017 (n = 56,276), 2018 (n = 56,313), and 2019 (n = 56,136). Beginning in 2015, the NSDUH began collecting information on sexual identity among adults 18 years and older only, so individuals aged 12 to 17 (n = 68,263) were excluded from our study. To estimate SUD service utilization and perceived need for treatment among people reporting impairment related to their substance use, we excluded 192,323 adults who did not meet past-year Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV) criteria for substance abuse or substance dependence, including alcohol, cannabis, or other drugs (American Psychiatric Association, 1994). Moreover, we excluded adults who reported their sexual identity as “Don’t know” or who were missing sexual identity information (n = 256) to allow for comparisons of self-identified sexual identity subgroups. Our final analytic sample included 21,926 adults in the 2015-2019 NSDUH who self-identified as heterosexual, lesbian, gay, or bisexual and met criteria for any past-year SUD.

2.3. Measures

Sexual identity was assessed by asking, “Which one of the following do you consider yourself to be?” Response options included “Heterosexual, that is, straight,” “Lesbian or gay,” “Bisexual,” “Don’t know,” or refuse to answer. We created a categorical variable for sexual identity (i.e., heterosexual, lesbian or gay, or bisexual). As noted above, “Don’t know” and “refuse” were excluded from the sample.

Past-year SUD treatment outcomes of interest included: 1) any SUD treatment; 2) specialty SUD treatment; and 3) perceived SUD treatment need. Any past-year SUD treatment was assessed by asking respondents: “During the past 12 months, have you received treatment or counseling for your use of alcohol or any drug, not counting cigarettes?” This included any service utilization in outpatient and inpatient settings, such as a hospital, rehabilitation facility, emergency room, mental health center, doctor’s office, prison or jail, as well as self-help services (e.g., Alcoholics Anonymous and Narcotics Anonymous), or “some other place.” Specialty SUD treatment, a subset of any SUD treatment, encompasses treatment in an inpatient hospital, drug or alcohol rehabilitation center (inpatient or outpatient), or mental health center offering specialty treatments (i.e., excluding outpatient hospital, emergency room, doctor’s office, self-help groups, prison, or jail). Perceived SUD treatment need was assessed among respondents who did not receive SUD treatment in the past 12 months (i.e., “[D]id you [need] treatment or counseling for your alcohol or drug use?”) and people who reported feeling a need for additional SUD treatment despite having received treatment. We created binary variables (yes/no) for each of the three past-year outcomes: any SUD treatment, specialty SUD treatment, and perceived treatment need.

Socio-demographic characteristics included gender (men, women), age (18-25, 26-34, 35-49, ≥50 years), race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, non-Hispanic Other), education (less than high school, high school graduate, some college/2-year degree, 4-year college degree), any health insurance (yes, no), household income (<$20,000, $20,000-$49,999, $50,000-$74,999, ≥$75,000), and survey year (2015, 2016, 2017, 2018, 2019). An indicator of past-year co-occurring SUDs (i.e., 1, 2, or 3+ SUDs) was based on a count of number of SUDs, including alcohol, cannabis, or other drugs.

2.4. Statistical analyses

We calculated weighted percentages to describe each demographic characteristic stratified by gender and sexual identity among adults with a past-year SUD. We then calculated weighted prevalences of SUD treatment use and perceived need, stratified by gender and sexual identity.

We used weighted multivariable logistic regression models to estimate odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for the association between sexual identity and SUD treatment outcomes among adults with SUD. Multivariable models were stratified by gender, in accordance with prior literature (Philbin et al., 2020; Schuler et al., 2019a, 2019b; Schuler and Collins, 2020), and adjusted for potential confounders of reporting sexual identity and treatment, including age, race/ethnicity, education, survey year, marital status, health insurance, and household income. Additionally, we conducted sensitivity analysis adjusting for the number of co-occurring SUDs in order to account for potential differences in treatment utilization among people with multiple SUDs.

All analyses accounted for complex survey design, with survey-provided sample weights divided by five to account for pooled sample across 2015-2019 per NSDUH guidelines. Data analyses were performed using Stata SE version 14 (StataCorp, 2015).

3. Results

3.1. Demographic characteristics

Table 1 reports sample sociodemographic characteristics among adults in the United States with at least one past-year SUD by sexual identity and gender. Between 57.1-70.0% of our sample were non-Hispanic white, 18.0-40.6% completed a 4-year college degree, 19.3-33.5% had an income of less than $20,000, and a majority (82.6-89.9%) had health insurance. In the past year, a majority of the sample with an SUD met criteria for alcohol use disorder (66.2-76.0%), 14.2-27.4% for cannabis use disorder, and 18.9-30.3% other drug use disorder (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics among 2015-2019 NSDUH1 participants 18 years or older with substance use disorder in the past year by gender and sexual identity (n=21,926).

| Men (n=12,884) | Women (n=9,042) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Heterosexual (n=11,944) |

Gay (n=487) |

Bisexual (n=453) |

Heterosexual (n=7,111) |

Gay/Lesbian (n=342) |

Bisexual (n=1,589) |

| w. col, %2 | w. col, %2 | w. col, %2 | w. col, %2 | w. col, %2 | w. col, %2 | |

| Age (years) | ||||||

| 18-25 | 23.6 | 25.4 | 34.1 | 28.0 | 34.4 | 44.8 |

| 26-34 | 24.5 | 27.8 | 26.1 | 22.3 | 31.6 | 33.0 |

| 35-49 | 25.4 | 28.4 | 21.7 | 25.9 | 21.4 | 17.0 |

| ≥50 | 26.5 | 18.4 | 18.1 | 23.8 | 12.6 | 5.3 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 66.3 | 59.2 | 63.3 | 70.0 | 57.1 | 61.6 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 11.2 | 15.5 | 9.7 | 10.8 | 17.0 | 15.1 |

| Hispanic | 16.3 | 20.1 | 20.6 | 11.9 | 18.2 | 15.7 |

| Other | 6.1 | 5.3 | 6.5 | 7.2 | 7.6 | 7.7 |

| Education | ||||||

| Less than high school | 15.0 | 7.5 | 10.5 | 8.2 | 9.0 | 11.8 |

| High school graduate | 27.3 | 17.2 | 28.6 | 21.1 | 18.5 | 26.1 |

| Some college / 2-year degree | 31.3 | 34.6 | 43.0 | 39.3 | 36.0 | 41.6 |

| 4-year college degree | 26.4 | 40.6 | 18.0 | 31.4 | 36.5 | 20.5 |

| Health Insurance | ||||||

| Yes | 82.6 | 87.2 | 83.9 | 89.9 | 85.1 | 85.6 |

| Household Income | ||||||

| <$20,000 | 19.3 | 20.6 | 24.8 | 22.4 | 31.9 | 33.5 |

| $20,000-$49,999 | 28.7 | 28.2 | 39.0 | 29.4 | 25.3 | 31.2 |

| $50,000-$74,999 | 14.3 | 16.5 | 11.4 | 15.0 | 7.3 | 11.8 |

| ≥$75,000 | 37.8 | 34.7 | 24.8 | 33.2 | 35.5 | 23.6 |

| Number of substance use disorders | ||||||

| 1 | 80.5 | 69.0 | 75.4 | 78.5 | 77.2 | 68.6 |

| 2 | 12.4 | 19.7 | 14.3 | 13.7 | 14.9 | 18.5 |

| 3+ | 7.1 | 11.3 | 10.3 | 7.8 | 7.9 | 12.9 |

| Types of substance use dependence or abuse | ||||||

| Alcohol | 76.0 | 74.8 | 70.6 | 75.9 | 69.5 | 66.2 |

| Cannabis | 19.9 | 22.6 | 27.0 | 14.2 | 22.9 | 27.4 |

| Illicit drugs other than cannabis | 18.9 | 30.2 | 22.9 | 22.0 | 20.3 | 30.3 |

| Survey Year | ||||||

| 2015 | 21.1 | 23.0 | 13.0 | 20.7 | 16.7 | 14.3 |

| 2016 | 19.6 | 23.9 | 18.7 | 21.4 | 17.6 | 17.8 |

| 2017 | 19.7 | 17.5 | 17.9 | 19.4 | 20.6 | 18.2 |

| 2018 | 20.0 | 15.9 | 25.7 | 19.9 | 18.0 | 21.3 |

| 2019 | 19.6 | 19.7 | 24.7 | 18.5 | 27.1 | 28.4 |

NSDUH - National Survey on Drug Use and Health

w. col % = survey weighted column percentage

Column percentages may not sum to 100% due to rounding

3.2. Prevalence of SUD service utilization and perceived treatment need by sexual identity and gender

Any SUD treatment, specialty treatment, and perceived treatment need among adults with a past-year SUD were uniformly low across genders and sexual identities (Figure 1). Prevalence of any past-year SUD treatment was 10.4% among heterosexual men, 15.5% among gay men, and 7.1% among bisexual men. Past-year specialty SUD treatment utilization was also low—heterosexual men (7.0%), gay men (10.7%) and bisexual men (6.1%). Only 4.4% of heterosexual men , 7.1% of gay men, and 9.8% of bisexual men with SUD perceived a need for treatment.

Figure 1.

Prevalence of substance use disorder treatment use and perceived treatment need among adults 18 years or older with a past-year substance use disorder by sexual identity and gender in the 2015-2019 NSDUH (n=21,926).

Among women with SUDs, prevalence of any past-year SUD treatment was 9.9%, 11.9%, and 13.2% among heterosexual, gay/lesbian, and bisexual women, respectively. Past-year specialty SUD treatment utilization was uniformly low: heterosexual women (7.0%), gay/lesbian women (8.6%), and bisexual women (10.0%)—as was perceived treatment need—heterosexual women (4.9%), gay/lesbian women (5.1%), and bisexual women (7.8%).

3.3. Relationship between past-year SUD treatment use and sexual identity by gender

In the adjusted models, gay men had higher odds of any past-year SUD treatment (adjusted odds ratio (aOR) = 1.65, 95% CI 1.10-2.46) and specialty SUD treatment (aOR = 1.71, 95% CI 1.10-2.65) than their heterosexual counterparts (Table 2). Bisexual women also had higher adjusted odds of any past-year SUD treatment (aOR = 1.31, 95% CI 1.01-1.69) and specialty SUD treatment (aOR = 1.36, 95% CI 1.01-1.82) than heterosexual women.

Table 2.

Gender-stratified associations between sexual identity and past-year SUD treatment utilization and perceived treatment need among adults 18 years or older with a past-year substance use disorder, NSDUH1 2015-2019 (n = 21,926).

| Any past-year SUD treatment | Past-year specialty SUD treatment | Perceived treatment need | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Sexual identity | uOR (95% CI) | aOR (95% CI) | uOR (95% CI) | aOR (95% CI) | uOR (95% CI) | aOR (95% CI) |

| Men | Heterosexual | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Gay | 1.58 (1.06-2.36) | 1.65 (1.10-2.46) | 1.60 (1.03-2.48) | 1.71 (1.10-2.65) | 1.66 (1.02-2.69) | 1.76 (1.09-2.84) | |

| Bisexual | 0.66 (0.41-1.06) | 0.63 (0.40-1.01) | 0.86 (0.50-1.49) | 0.84 (0.49-1.42) | 2.36 (1.36-4.10) | 2.39 (1.35-4.24) | |

| Women | Heterosexual | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Gay/Lesbian | 1.23 (0.80-1.88) | 1.27 (0.83-1.94) | 1.26 (0.78-2.02) | 1.28 (0.79-2.06) | 1.05 (0.60-1.86) | 1.07 (0.60-1.90) | |

| Bisexual | 1.38 (1.09-1.76) | 1.31 (1.01-1.69) | 1.48 (1.11-1.97) | 1.36 (1.01-1.82) | 1.64 (1.23-2.19) | 1.65 (1.22-2.25) | |

NSDUH - National Survey on Drug Use and Health.

SUD = substance use disorder. uOR = unadjusted odds ratio. aOR = adjusted odds ratio.

Adjusted models controlled for age, race/ethnicity, education, survey year, health insurance status, and household income.

Bolded estimates were statistically significant at the 0.05 probability level.

3.4. Relationship between perceived SUD treatment need and sexual identity by gender

In adjusted models, gay men (aOR = 1.76, 95% CI 1.09-2.84) and bisexual men (aOR = 2.39, 95% CI 1.35-4.24) had higher odds of perceived treatment need than heterosexual men (Table 2). Similarly, bisexual women had higher adjusted odds of perceived treatment need (aOR = 1.65, 95% CI 1.22-2.25) than heterosexual women.

Sensitivity analysis adjusting for number of co-occurring SUD attenuated the magnitude of effects and were consistent with the direction of our main findings (Table S1).

4. Discussion

In this study of adults in the United States with a past-year SUD, we estimated past-year SUD treatment use and perceived treatment need by sexual identity and gender. Consistent with prior research (Blanco et al., 2015; Mauro et al., 2020; Olfson et al., 1998; Wang et al., 2005), we found that any SUD treatment utilization was low among all groups of adults with a past-year SUD (i.e., 7.1%-15.5%). Results showed that gay men and bisexual women, but not bisexual men, were more likely to receive any SUD treatment or specialty SUD treatment than their heterosexual peers after adjusting for covariates. We also found significantly greater perceived treatment need among gay men, bisexual men, and bisexual women compared to heterosexuals of the same gender, after adjusting for sociodemographics. As substantial unmet treatment need remains among all adults, public health efforts should prioritize facilitating substance use treatment uptake among adults with SUDs. This includes efforts to reduce SUD treatment barriers among sexual minority adults (Haney, 2020) who have a notably higher SUD burden than their heterosexual counterparts (Allen and Mowbray, 2016; Hughes, 2011; McCabe et al., 2013; Schuler et al., 2019b).

We found differences in the likelihood of past-year any and specialty SUD treatment use by gender and sexual identity among adults with past-year SUD, partially in line with past work (Allen and Mowbray, 2016; McCabe et al., 2013). Treatment utilization, either any or specialty, was significantly higher among gay men and bisexual women (compared to heterosexual men and women, respectively). Gay men show greater utilization of health care (Boehmer et al., 2012) and screening services (Heslin et al., 2008) than heterosexual men. This might be, at least in part, due to community involvement that provides social support and counters stigma (Ramirez-Valles, 2002), community based public health campaigns for prevention of HIV and increasing healthcare utilization (Cahill et al., 2013), and higher utilization of mental health services among gay men in comparison to heterosexual men (Cochran et al., 2003). Bisexual women utilize mental health services more often than heterosexual women (Bakker et al., 2006; Flentje et al., 2015; Grella et al., 2009), which is consistent with our observed patterns of higher SUD treatment use. In contrast, bisexual men reported the lowest prevalence of SUD treatment use overall, contrary to prior work (McCabe et al., 2013). For bisexual men and other sexual minority adults, expanding access to comprehensive health insurance coverage and healthcare overall that is affirming of the experiences of sexual minority adults improves health outcomes and may facilitate competent linkage to SUD care and uptake of SUD treatment (Buchmueller and Carpenter, 2010; Haney, 2020; Senreich, 2010; Tabaac et al., 2020).

Our findings of higher treatment use among certain subgroups, particularly gay men and bisexual women, are partially at odds with minority stress theory. From a strength-based perspective, our findings highlight the hurdles that individuals from these marginalized communities have overcome to meet their substance use treatment needs. Our study, as well as prior ones, demonstrate that sexual minorities, bisexual women in particular, are more likely to enter SUD treatment (McCabe et al., 2013) and hence may also be more aware of SUD treatment need than their heterosexual peers. These findings contrast existing evidence suggesting sexual minority groups under-estimate substance use-related harms (Boyle et al., 2020). Still, peer and community norms-based interventions may help to correct any existing misinformation related to substance use, thereby further expanding wiliness to engage in substance use treatment, and improving the overall low levels of treatment utilization among groups with disproportionately high SUD burden (Allen and Mowbray, 2016; Hughes, 2011; McCabe et al., 2013; Schuler et al., 2019b).

At the same time, we found that sexual minority adults were more likely to perceive a need for SUD treatment relative to heterosexuals of the same gender, with the exception of gay/lesbian women. As perceived treatment need has been associated with subsequent treatment seeking overall (Mojtabai and Crum, 2013), our findings could indicate that sexual minority adults may be more likely to seek SUD treatment services in the future. Higher perceived need for treatment among sexual minority adults suggests a critical opportunity to reduce the SUD burden experienced by sexual minority adults (Allen and Mowbray, 2016; Green and Feinstein, 2012; Hughes, 2011; Pennay et al., 2018; Schuler et al., 2019a, 2019b, 2018). Our findings are consistent with higher perceived need and higher mental health service use among sexual minority adults relative to heterosexual adults (Flentje et al., 2015; Jeong et al., 2016). Future studies should assess whether higher perceived need for treatment is a result of community norms that allow for higher treatment acceptability in this population.

In our sample, bisexual women had higher prevalence of SUD treatment use and perceived treatment need than other subgroups of women. These findings align with prior work (Allen and Mowbray, 2016; McCabe et al., 2013) that found higher SUD treatment utilization among bisexual individuals compared to their heterosexual counterparts. As a contrast, bisexual men reported the lowest overall prevalence of SUD treatment (7.1%) use while having a significantly higher perceived treatment need than heterosexual men. Bisexual men and women encounter unique treatment barriers than their heterosexual and gay/lesbian peers, such as disproportionate financial barriers, dismissal of bisexual identity, stress related to concealment and disclosure of sexual identity, including rejection sensitivity, and internalized stigma related to bisexual identity (Allen and Mowbray, 2016; Bränström, 2017; Feinstein and Dyar, 2017; Meyer, 2003; Pachankis, 2014; Schrimshaw et al., 2013). These may particularly inhibit treatment utilization among bisexual men who disclose their sexual identity to non-affirming providers. Moreover, given that only a small fraction of bisexual women received SUD treatment (13.2%) despite having the highest SUD burden (Schuler and Collins, 2020) and perceiving a need, tailoring SUD treatment and prevention outreach for bisexual women is a pressing public health goal. Future studies could examine potential lateral disparities (Schuler and Collins, 2020) in perceived treatment need between lesbian/gay and bisexual women (Jeong et al., 2016) in addition to the distinctive barriers to treatment utilization among bisexual men, compared to gay men, who perceive a need for substance use treatment.

The unmet treatment need identified by our study of adults with past-year SUD supports the need for interventions seeking to bridge the gap between perceived treatment need and SUD treatment utilization. For example, integrating screening for SUDs and perceptions of SUD treatment need in primary and other healthcare settings could be a tool to reduce barriers to treatment (Senreich, 2010). This is important across subgroups, because while most adults who use drugs report not discussing drug use with their providers, these discussions are positively associated with treatment use and perceived treatment need (Mauro et al., 2020). While beyond the scope of our study, programs that scale up access to SUD treatment for sexual minority adults could help to reduce the complex burden of unmet treatment need (Cochran et al., 2007). This includes programs that acknowledge and address the diverse minority stressors that sexual minority clients cope with on a daily basis, and that adequately train their staff around treatment issues particular to the needs of sexual minority clients (Cochran et al., 2007). Specific strategies could be used to enhance treatment linkage and retention, such as including treatment services that are attentive to the needs of sexual minority individuals, with supportive providers who do not perpetuate stigma and discrimination (Cochran and Cauce, 2006; Flentje et al., 2015). Substance use treatment providers serving sexual minority groups should not take a monolithic approach, but rather tailor treatment to the needs of specific sexual minority subgroups (e.g., gay men versus bisexual men) (Cochran and Cauce, 2006; Pennay et al., 2018).

Our study has several limitations and strengths. First, sexual identity was gathered through self-report, and sexual minority identities may be under-reported. However, audio computer-assisted methods could reduce social desirability biases related to sensitive information (Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, 2016). Our findings may not generalize to individuals with other sexual identities not captured in the survey, or to adolescents for whom we did not have sexual identity information. Second, the NSDUH did not target recruitment of sexual minority adults, which may lead to imprecise estimates among smaller subgroups (e.g., bisexual men). Still, the use of a nationally representative sample of adults more broadly can strengthen our understanding of SUD treatment outcomes among sexual minority individuals beyond clinic-based samples. Third, the NSDUH does not include questions on gender identity, which prohibits our ability to study substance use treatment utilization and perceived need among people based on their gender identities. Fourth, self-reported treatment measures may be affected by recall bias. As the NSDUH does not include questions related to craving, which is a component of SUD diagnostic criteria in the DSM-5, so we used DSM-IV criteria for past-year SUD including substance abuse and/or dependence among adults. Nonetheless, DSM-IV SUD criteria still provide clinically meaningful information regarding who may need SUD treatment services.

5. Conclusion

We utilized nationally representative data from 2015-2019 to examine sexual identity and gender disparities in substance use treatment service utilization and perceived treatment need among adults with SUD. We found that SUD treatment utilization was low overall. Our findings suggest higher perceived need for SUD treatment among gay men, bisexual men, and bisexual women compared to same-gender heterosexual adults, but only gay men and bisexual women had higher SUD treatment utilization than their heterosexual counterparts. Increased access to SUD treatment services, tailored SUD treatment, and outreach may be needed to bridge the gap between perceived need for treatment and the treatment utilization overall and among sexual minority adults with SUD. Future studies should attend to the social and contextual factors that may be implemented to increase SUD treatment uptake among sexual minority adults who perceive a treatment need.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Past-year SUD treatment use was low among adults across sexual identity and gender

Most LGB adults perceived a greater SUD treatment need than heterosexuals

SUD treatment use odds were higher among bisexual women and gay men

Results support facilitating SUD treatment access and engagement among LGB adults

Funding

This work was partially supported by the National Institutes of Health/National Institute on Drug Abuse grants K01DA045224 (PI: Mauro); T32DA031099 (PI: Hasin); K01DA039804A (PI: Philbin).

References

- Allen JL, Mowbray O, 2016. Sexual orientation, treatment utilization, and barriers for alcohol related problems: Findings from a nationally representative sample. Drug Alcohol Depend. 161, 323–330. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.02.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association, 1994. DSM-IV Criteria for Substance Abuse and Substance Dependence 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Bakker FC, Sandfort TGM, Vanwesenbeeck I, van Lindert H, Westert GP, 2006. Do homosexual persons use health care services more frequently than heterosexual persons: Findings from a Dutch population survey. Soc. Sci. Med 63, 2022–2030. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.05.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco C, Iza M, Rodríguez-Fernández JM, Baca-García E, Wang S, Olfson M, 2015. Probability and predictors of treatment-seeking for substance use disorders in the U.S. Drug Alcohol Depend. 149, 136–144. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.01.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boehmer U, Miao X, Linkletter C, Clark MA, 2012. Adult Health Behaviors Over the Life Course by Sexual Orientation. Am. J. Public Health 102, 292–300. 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle SC, LaBrie JW, Omoto AM, 2020. Normative substance use antecedents among sexual minorities: A scoping review and synthesis. Psychol. Sex. Orientat. Gend. Divers 7, 117–131. 10.1037/sgd0000373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bränström R, 2017. Minority stress factors as mediators of sexual orientation disparities in mental health treatment: a longitudinal population-based study. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 71, 446–452. 10.1136/jech-2016-207943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bränström R, Pachankis JE, 2018. Sexual orientation disparities in the co-occurrence of substance use and psychological distress: a national population-based study (2008–2015). Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol 53, 403–412. 10.1007/s00127-018-1491-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchmueller T, Carpenter CS, 2010. Disparities in Health Insurance Coverage, Access, and Outcomes for Individuals in Same-Sex Versus Different-Sex Relationships, 2000–2007. Am. J. Public Health 100, 489–495. 10.2105/AJPH.2009.160804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahill S, Valadéz R, Ibarrola S, 2013. Community-based HIV prevention interventions that combat anti-gay stigma for men who have sex with men and for transgender women. J. Public Health Policy 34, 69–81. 10.1057/jphp.2012.59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, 2020. 2019 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Methodological summary and definitions. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. [Google Scholar]

- Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, 2016. 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Methodological summary and definitions. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. [Google Scholar]

- Cochran BN, Cauce AM, 2006. Characteristics of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender individuals entering substance abuse treatment. J. Subst. Abuse Treat 30, 135–146. 10.1016/j.jsat.2005.11.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cochran BN, Peavy KM, Robohm JS, 2007. Do Specialized Services Exist for LGBT Individuals Seeking Treatment for Substance Misuse? A Study of Available Treatment Programs. Subst. Use Misuse 42, 161–176. 10.1080/10826080601094207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cochran SD, Sullivan JG, Mays VM, 2003. Prevalence of mental disorders, psychological distress, and mental health services use among lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults in the United States. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol 71, 53–61. 10.1037/0022-006X.71.1.53 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinstein BA, Dyar C, 2017. Bisexuality, Minority Stress, and Health. Curr. Sex. Heal. Reports 9, 42–49. 10.1007/s11930-017-0096-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flentje A, Livingston NA, Roley J, Sorensen JL, 2015. Mental and Physical Health Needs of Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Clients in Substance Abuse Treatment. J. Subst. Abuse Treat 58, 78–83. 10.1016/j.jsat.2015.06.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost DM, Lehavot K, Meyer IH, 2015. Minority stress and physical health among sexual minority individuals. J. Behav. Med 38, 1–8. 10.1007/s10865-013-9523-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green KE, Feinstein BA, 2012. Substance use in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: An update on empirical research and implications for treatment. Psychol. Addict. Behav 26, 265–278. 10.1037/a0025424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grella CE, Greenwell L, Mays VM, Cochran SD, 2009. Influence of gender, sexual orientation, and need on treatment utilization for substance use and mental disorders: Findings from the California Quality of Life Survey. BMC Psychiatry 9, 52. 10.1186/1471-244X-9-52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haney JL, 2020. Sexual Orientation, Social Determinants of Health, and Unmet Substance Use Treatment Need: Findings from a National Survey. Subst. Use Misuse 0, 1–9. 10.1080/10826084.2020.1853775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML, Pachankis JE, 2016. Stigma and Minority Stress as Social Determinants of Health Among Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Youth: Research Evidence and Clinical Implications. Pediatr. Clin. North Am 63, 985–997. 10.1016/j.pcl.2016.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heslin KC, Gore JL, King WD, Fox SA, 2008. Sexual Orientation and Testing for Prostate and Colorectal Cancers Among Men in California. Med. Care 46, 1240–1248. 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31817d697f [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes T, 2011. Alcohol Use and Alcohol-Related Problems Among Sexual Minority Women. Alcohol. Treat. Q 29, 403–435. 10.1080/07347324.2011.608336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong YM, Veldhuis CB, Aranda F, Hughes TL, 2016. Racial/ethnic differences in unmet needs for mental health and substance use treatment in a community-based sample of sexual minority women. J. Clin. Nurs 25, 3557–3569. 10.1111/jocn.13477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mauro PM, Samples H, Klein KS, Martins SS, 2020. Discussing Drug Use With Health Care Providers Is Associated With Perceived Need and Receipt of Drug Treatment Among Adults in the United States. Med. Care 58, 617–624. 10.1097/MLR.0000000000001340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe SE, Bostwick WB, Hughes TL, West BT, Boyd CJ, 2010. The relationship between discrimination and substance use disorders among lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults in the United States. Am. J. Public Health 100, 1946–1952. 10.2105/AJPH.2009.163147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe SE, West BT, Hughes TL, Boyd CJ, 2013. Sexual Orientation and Substance Abuse Treatment Utilization in the United States: Results from a National Survey. J. Subst. Abuse Treat 44, 4–12. 10.1016/j.jsat.2012.01.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medley G, Lipari RN, Bose J, Cribb DS, Kroutil LA, McHenry G, 2006. Sexual Orientation and Estimates of Adult Substance Use and Mental Health: Results from the 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH, 2003. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychol. Bull. 129, 674–697. 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mojtabai R, Crum RM, 2013. Perceived unmet need for alcohol and drug use treatments and future use of services: Results from a longitudinal study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 127, 59–64. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.06.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olfson M, Kessler RC, Berglund PA, Lin E, 1998. Psychiatric Disorder Onset and First Treatment Contact in the United States and Ontario. Am. J. Psychiatry 155, 1415–1422. 10.1176/ajp.155.10.1415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pachankis JE, 2014. Uncovering Clinical Principles and Techniques to Address Minority Stress, Mental Health, and Related Health Risks Among Gay and Bisexual Men. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract 21, 313–330. 10.1111/cpsp.12078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennay A, McNair R, Hughes TL, Leonard W, Brown R, Lubman DI, 2018. Improving alcohol and mental health treatment for lesbian, bisexual and queer women: Identity matters. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 42, 35–42. 10.1111/1753-6405.12739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philbin MM, Greene ER, Martins SS, LaBossier NJ, Mauro PM, 2020. Medical, Nonmedical, and Illegal Stimulant Use by Sexual Identity and Gender. Am. J. Prev. Med 59, 686–696. 10.1016/j.amepre.2020.05.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez-Valles J, 2002. The protective effects of community involvement for HIV risk behavior: a conceptual framework. Health Educ. Res 17, 389–403. 10.1093/her/17.4.389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrimshaw EW, Siegel K, Downing MJ, Parsons JT, 2013. Disclosure and concealment of sexual orientation and the mental health of non-gay-identified, behaviorally bisexual men. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol 81, 141–153. 10.1037/a0031272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuler MS, Collins RL, 2020. Sexual minority substance use disparities: Bisexual women at elevated risk relative to other sexual minority groups. Drug Alcohol Depend. 206, 107755. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.107755 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuler MS, Dick AW, Stein BD, 2019a. Sexual minority disparities in opioid misuse, perceived heroin risk and heroin access among a national sample of US adults. Drug Alcohol Depend. 201, 78–84. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.04.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuler MS, Rice CE, Evans-Polce RJ, Collins RL, 2018. Disparities in substance use behaviors and disorders among adult sexual minorities by age, gender, and sexual identity. Drug Alcohol Depend. 189, 139–146. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.05.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuler MS, Stein BD, Collins RL, 2019b. Differences in substance use disparities across age groups in a national cross-sectional survey of Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Adults. LGBT Heal. 6, 68–76. 10.1089/lgbt.2018.0125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senreich E, 2010. Are specialized LGBT program components helpful for gay and bisexual men in substance abuse treatment. Subst. Use Misuse 45, 1077–1096. 10.3109/10826080903483855 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- StataCorp, 2015. Stata Statistical Software: Release 14.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2020a. Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: Results from the 2019 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Rockville, MD: Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2020b. 2019 NSDUH Detailed Tables. Rockville, MD. [Google Scholar]

- Tabaac AR, Solazzo AL, Gordon AR, Austin SB, Guss C, Charlton BM, 2020. Sexual orientation-related disparities in healthcare access in three cohorts of U.S. adults. Prev. Med. (Baltim) 132, 105999. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2020.105999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), 2016. Office of the Surgeon General, Facing Addiction in America: The Surgeon General’s Report on Alcohol, Drugs, and Health. Washington, DC: HHS. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang PS, Berglund P, Olfson M, Pincus HA, Wells KB, Kessler RC, 2005. Failure and Delay in Initial Treatment Contact After First Onset of Mental Disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 62, 603. 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitehead J, Shaver J, Stephenson R, 2016. Outness, Stigma, and Primary Health Care Utilization among Rural LGBT Populations. PLoS One 11, e0146139. 10.1371/journal.pone.0146139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams ND, Fish JN, 2020. The availability of LGBT-specific mental health and substance abuse treatment in the United States. Health Serv. Res 1475–6773.13559. 10.1111/1475-6773.13559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.