Abstract

Causal decomposition analyses can help build the evidence base for interventions that address health disparities (inequities). They ask how disparities in outcomes may change under hypothetical intervention. Through study design and assumptions, they can rule out alternate explanations such as confounding, selection bias, and measurement error, thereby identifying potential targets for intervention. Unfortunately, the literature on causal decomposition analysis and related methods have largely ignored equity concerns that actual interventionists would respect, limiting their relevance and practical value. This paper addresses these concerns by explicitly considering what covariates the outcome disparity and hypothetical intervention adjust for (so-called allowable covariates) and the equity value judgments these choices convey, drawing from the bioethics, biostatistics, epidemiology, and health services research literatures. From this discussion, we generalize decomposition estimands and formulae to incorporate allowable covariate sets (and thereby reflect equity choices) while still allowing for adjustment of non-allowable covariates needed to satisfy causal assumptions. For these general formulae, we provide weighting-based estimators based on adaptations of ratio-of-mediator-probability and inverse-odds-ratio weighting. We discuss when these estimators reduce to already used estimators under certain equity value judgements, and a novel adaptation under other judgments.

Keywords: Causal inference, Oaxaca–Blinder decomposition, mediation analysis, interventional effects, equity, disparity, allowability, ethics

Introduction

Health disparities represent differences across socially privileged vs. socially marginalized groups that society considers inequitable, avoidable, and unjust.1 Interventions that address disparities2 usually affect risk factors that are overrepresented among marginalized groups. Often their evidence base draws from studies that compare measures of disparities before and after adjustment for a risk factor (the difference method3). But the changes seen after such adjustments may be due to confounding, selection bias, or information bias. The results may not imply that the risk factor studied is the one to be intervened upon. Causal decomposition methods4–8 compare to a counterfactual disparity under a hypothetical intervention on a target risk factor. They overcome the limitations of simple adjustment through sound study design and unverifiable assumptions to rule out alternative explanations (bias). They ask a simple question: how disparities in outcomes would change if disparities in a targeted factor (that affects the outcome) were removed.

Unfortunately, estimators used for causal decomposition have ignored how disparities and hypothetical interventions are defined, limiting their relevance in health equity research. What should a disparity measure for the outcome condition on or standardize over? Surveillance reports that track health disparities usually adjust for age and sex, but some decomposition estimators adjust for all covariates needed to identify a causal effect. Ideally, disparity measures should reflect judgments about what constitutes an inequitable difference in the outcome.

Estimators have also ignored how hypothetical interventions are defined. As such, the hypothetical intervention, meant to remove disparities in a targeted factor, may not reflect equity concerns that actual interventionists would respect. For example, an intervention to remove disparities in healthcare should depend on clinical status, but not socioeconomic status which is irrelevant for medical care. Hypothetical interventions should reflect judgments about what constitutes an inequitable difference in the target.

In this paper, we outline a framework for defining disparities and interventions in causal decomposition analysis and provide estimands, non-parametric formulae, and weighting estimators to implement it. Specifically, we draw from the bioethics, biostatistics, epidemiology, and health services research literatures to consider when covariates are ‘allowable’ for adjusting disparity measures and hypothetical interventions. The estimands, formulae, and estimators we propose partition covariates into ‘allowable’ sets that define the disparity and intervention, and a ‘non-allowable’ set that is needed to identify the causal effect. Under a motivating example, we use this framework to examine estimators of natural and interventional effects (mediation analysis) and discrimination (Oaxaca–Blinder decomposition) and the equity judgments they imply and consider a meaningful alternative.

Motivating Example and Notation

We ground our ideas through a motivating example from clinical medicine: how to reduce disparities in hypertension control by intervening on decisions to intensify antihypertensive treatment.9 Suppose a healthcare system administrator wants to address disparities in hypertension control across race/ethnicity and tasks us with forming a cohort to study them. Patients are enrolled at their first visit if, on the basis of their systolic blood pressure (), they can be classified as hypertensive (;1=yes, mm Hg, 0 =no, mm Hg). For simplicity we ignore diastolic blood pressure. At six months follow-up systolic blood pressure () and uncontrolled hypertension (;1=yes, mm Hg, 0 =no, mm Hg) are measured. Disparities in hypertension control may arise through clinical uncertainty.10 When providers know less about their patients’ medical condition (due to poor provider communication, for example) their decisionmaking may rely on stereotypes. We are interested in how eliminating disparities in treatment decisions would affect disparities in hypertension control.

We thus record the patient’s race where represents membership in the marginalized group (e.g., blacks) and the privileged group (e.g., whites), demographics age and sex , whether antihypertensive treatment was intensified at the initial visit (; 1=yes, 0=no) as well as socioeconomic factors such as educational attainment and private health insurance that may implicitly affect treatment and hypertension control. We also record diabetes diagnosis which, as a marker of cardiovascular risk, predicts blood pressure and may influence treatment decisions.

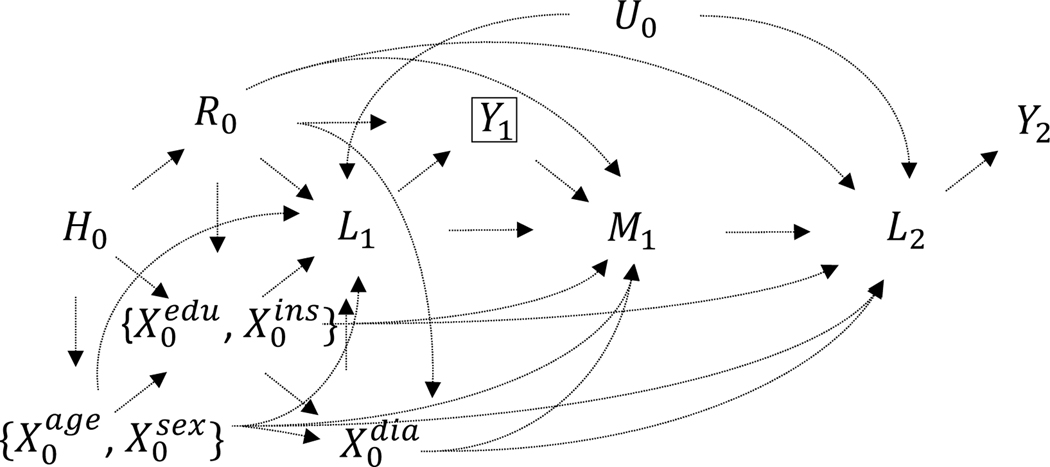

The subscripts in our notation grossly indicates a temporal ordering, where ‘0’ indicates variables that are realized before baseline, ‘1’ indicate those realized at baseline, and ‘2’ indicates those realized at follow-up. We assume that some associations between race/ethnicity , , and are driven by historical processes (e.g., slavery, Jim Crow, federal and local housing policies) as depicted in our causal graph (Figure 1), provided for intuition. We allow that unmeasured factors may correlate repeated measures of systolic blood pressure and and possibly other variables but do not independently predict treatment intensification . In our notation, random variables are written in uppercase and their realizations in lowercase. For any variable , the probability is abbreviated as .

Figure 1.

Causal diagram depicting relationships between history (), race (), demographics age and sex ( and ), socioeconomic covariates educational attainment and private health insurance ( and ), diabetes (), baseline and follow-up blood pressure ( and ), hypertensive status at baseline and subsequent control ( and ), and treatment intensification . Additional arrows could be allowed from to the covariates . The subscripts denote, grossly, the time of realization: ‘0’ pre-baseline, ‘1’ baseline, ‘2’ follow-up. The box around indicates that the population of interest is those with uncontrolled hypertension at baseline. To simplify the graph, brackets group covariates with similar relationships. Within the subset no causal relationship is specified; within the subset causes

To develop general formulae, we will discuss two non-overlapping sets of ‘allowable’ covariates, those used to define the disparity in hypertension control (the outcome ), denoted as , and those used to further define the intervention on treatment intensification (the targeted factor ), denoted as . These sets are restricted to variables not affected by treatment intensification . While the time subscript on these sets indicates measurement at baseline, they can include variables measured before baseline as well.

We let denote a hypothetical stochastic intervention11,12 to set the conditional distribution of treatment intensification among blacks to the distribution among whites with identical values for and , denoted as . Suppose we choose as and , as and . Among blacks, under , their treatment is intensified according to a random draw from the distribution among whites who share the same values for , , and .

Meaningful Disparity and Intervention Definition

The disparity in hypertension control arises in large part because contextual and other cardiovascular risk factors, and also access to and quality of medical care, are differentially distributed across race.13 In the U.S., these inequities result from centuries of injustice, including slavery, Jim Crow, government policy, and other forms of structural, cultural, and personal racism.14 In our example, causal decomposition analysis asks how, among those with uncontrolled hypertension at baseline, the disparity in hypertension control at follow-up is affected by intervening to eliminate the disparity in treatment decisions .

Defining a disparity is a complex process involving decisions about what is fair and just in the distribution of health and its determinants.15–19 We focus on which covariates are considered allowable for adjustment in defining outcome disparities and interventions, and how these choices relate to equity value judgments. The notion of allowability has been discussed in the context of medical goods and used to define healthcare disparities in counterfactual terms.20,21 Our discussion broadens the concept to health disparities and decomposition analysis but avoids counterfactual definitions of disparity.

Allowability

In the bioethics literature, many define a health disparity as an avoidable, systematic difference between socially advantaged vs. marginalized groups, wherein the marginalized group is further disadvantaged on health.22,23 In the health services research literature, disparities in healthcare are often defined using the Institute of Medicine definition, as differences in healthcare services that are not due to differences in underlying health needs or preferences.20,24 A careful reading of these definitions recognizes that, in defining disparities, both avoid detailing a causal model for how they arise. While there are some objections to this,21 there are practical and scientific reasons why this may be desirable.22,23

These definitions encourage us to consider what sources of difference might be considered fair or allowable and to take these off the table when measuring disparity. By corollary, non-allowable sources are those that are unjust and thus contribute to disparity. For health outcomes, allowable sources typically include demographic factors such as age and sex.25 For medical goods, allowable sources typically include clinical status, history, and presentation.20,24 All other factors are often considered non-allowable. Although these represent default choices in many studies, other positions become clear when issues of modifiability, amenability to intervention, social contract, and purpose are considered.

Modifiability & Amenability to Intervention

In defining health disparity measures, it is common to see innate, apparently non-modifiable factors such as chronological age, sex, and even somatic genotype treated as allowable and adjusted for. While society has profound power over the historical distribution of innate factors (through war, genocide, racism, and policy), for a fixed living population, it has no ability to modify them. On these grounds, some might argue that innate differences leading to differences in health are not necessarily unfair.19

Some object to using strict modifiability to decide whether to treat a covariate as allowable. The conceptualization and role of innate characteristics in daily, civic, and economic life are entirely under society’s control.26 Moreover, while society cannot change characteristics defined at birth, it can address their effects.16,22 Social programs can be made age and sex appropriate, increasing their effectiveness. Targeted cancer therapies have been developed for genetic profiles. If one considers a disparity as any difference placing a marginalized group at further disadvantage, and society can address the effects of innate characteristics, one might then consider their differences as contributors to disparity when society fails to adequately respond to them. Thus, innate differences could be considered non-allowable and not adjusted for. The decision to not adjust for innate factors is best applied when the marginalized group is disadvantaged on the innate factor. Failing to adjust otherwise could mask unjust differences.

Consider these arguments in our motivating example. First, we have pre-existing conditions. Blacks disproportionately encounter barriers to care, such as lack of health insurance, leading to higher prevalence of chronic conditions at baseline encounters. By that point, a patient’s clinical history is beyond the control of the clinician and healthcare system. However, this history can be managed for better prognosis, for example by consulting a specialist. Clinical guidelines recommend tailored treatment protocols for patients with diabetes, kidney disease, and heart failure. Thus, healthcare can respond to disparate pre-existing conditions. Failure to do so equitably would contribute to unjust differences in prognosis. Second, we have age. Blacks are typically younger than whites, and increasing age predicts poor hypertension control. Not adjusting for age would mask unjust differences in hypertension control. Overall, when measuring disparities in prognosis, if there are disparities in pre-existing conditions, one might reasonably decide to treat them as non-allowable (and not adjust). If blacks are younger than whites, one might reasonably decide to treat age as allowable (and adjust).

Social Contract

When defining hypothetical interventions that address disparities in goods, allowability choices should consider the social contract. The distribution of any good is ideally governed by norms and conditions that society has agreed upon as fair and just. That is, we believe that decisions about goods are fair if and only if they are based upon ideal criteria that reflect our shared norms and values. That is, in defining interventions on goods, we treat our idealized criteria as allowable.

These arguments have clear implications for interventions that address medical goods. Medical ethics dictates that decisions be clinically appropriate. For addressing disparities in diagnosis, allowable sources could include information needed to accurately differentiate between syndromes, such as presentation and test results. For addressing disparities in treatment, allowable sources could include factors that indicate and modify treatment effectiveness, such as comorbid conditions.24 For addressing disparities in social conditions, perhaps through a community health worker, allowable sources could include social needs. In our motivating example, the hypothetical intervention to intensify treatment would need to consider age, sex, baseline blood pressure, and diabetes but ignore socioeconomic status. Otherwise, the intervention would not only be unethical, but also inequitable. It would preserve racial differences in treatment that operate through racial differences in socioeconomic status.5 Observing the social contract reflects that our goal is not equal treatment, but equitable treatment.24

When defining disparities in outcomes that represent goods, allowability choices should also consider the social contract. This again would treat idealized decision-inputs as allowable. An exception can be made when one seeks to reduce racial differences in goods by eliminating disparities in a criterion governing their distribution. Suppose one were studying a lower rate of listing for transplantation among blacks compared with whites. Listing decisions often consider anticipated social support. An overall racial difference in listing partly due to differences in social support might be concerning, even considered disparate. Here, social support could be treated as non-allowable (and not adjusted for) so it could be studied as a hypothetical intervention.

Purpose

In defining outcome disparity measures, allowability must also consider their use. In surveillance and quality assessment, disparity measures can track how well a society, institution, or actor meets objectives. In these settings, when factors the actor does not control are treated as non-allowable (and not adjusted for), this can lead to deleterious effects. In our example, if an external body were benchmarking clinical practices based on disparities in hypertension control rates without any risk adjustment, those that serve marginalized populations with comorbidities may score worse. Those clinics might then be incentivized to avoid complex patients.27 When causal decomposition analysis is applied to performance assessment measures, it is advisable to study the one used in practice, which might call for pre-existing conditions to be treated as allowable, for the sake of risk adjustment.28

Measurement

We now turn to how outcome disparities are defined in our causal decomposition analysis. For the outcome, we define disparity as the mean outcome difference across levels of social groups, where the distribution of allowable covariates is standardized. Here, we use the pooled distribution as the standard. In defining the hypothetical intervention, which is intended to remove disparities in a targeted factor, we adjust for allowable covariates through conditioning. We have chosen these simple statistical measures of disparity because the observed disparities can be estimated directly from the data with minimal assumptions and are consistent with widely adopted definitions of disparity.22–24 These definitions assume common support for the allowable covariates across race. Otherwise adjustment would fail to remove the influence of allowable covariates. Defining disparities using the distribution among blacks or whites, rather than the pooled as the standard may weaken this common support assumption.

Meaningful Disparity Decomposition

Here, we present general causal decomposition estimands defined by allowable covariates for the disparity in hypertension control (the outcome ) and the hypothetical intervention to intensify treatment (the targeted intervention ). Under assumptions, we provide identifying formulae and weighting-based estimators. Importantly, these formulae and estimators can incorporate confounders that are considered non-allowable, without using them to define outcome disparities or the intervention. All expressions condition on the population of interest, persons with uncontrolled hypertension at baseline.

Definition

The observed disparity in uncontrolled hypertension is:

| (1) |

The change in disparity under the intervention to remove the disparity in treatment intensification is:

| (2) |

The remaining disparity after the intervention is:

| (3) |

The covariates used to define the disparity are considered outcome-allowable. These covariates , along with are used to define the intervention so both are considered target-allowable. These formulae (1)–(3) are agnostic about whether components of affect components of and vice-versa, and are also agnostic about whether and are affected by race , but do require that and are not affected by the targeted variable, treatment intensification . This will be satisfied in a design where the eligibility criteria defining the population of interest, the timing of the intervention on , and the start of follow-up coincide, and allowable covariates are measured at or before this moment.

Identification

The counterfactual disparity reduction (2) and residual (3) are not observed. These expressions can be identified with observational data under assumptions (see eAppendix for formal statements). Among blacks, where , we assume conditional exchangeability,29 or no unmeasured confounding of the relationship between treatment intensification and hypertension control : given the allowables and and an additional set of non-allowable confounders , the potential outcomes under treatment intensification are independent of observed treatment intensification. We further assume positivity29 among blacks, where there is a positive conditional probability of each observed value for treatment intensification given the allowable covariate sets and used to define the estimands and the non-allowable covariates used to help identify them. Subtly, it is sufficient if these conditions hold only for the values of observed among whites who share (with blacks) identical values of and . As a consequence, they can be satisfied when, for some subgroups, all have their treatment intensified. We also assume common support across race for the targeted factor and allowable covariates (jointly). Finally, we assume consistency29 among blacks, that their outcomes would be the same regardless if their values were merely observed or set by hypothetical intervention. These assumptions are strong and the ability to satisfy them will vary across substantive settings.30

When these assumptions hold, we can identify the proportion with uncontrolled hypertension among blacks under as:

| (4) |

This allows us to identify the disparity reduction (2) given that the observed proportion of uncontrolled hypertension among blacks is:

| (5) |

We can also identify the disparity residual (3) given that the observed proportion of uncontrolled hypertension among whites is:

| (6) |

Note that in equations (4)–(6) is replaced by if the distribution of outcome-allowable covariates that standardizes the disparity measure is drawn from blacks, and by if drawn from whites.

Estimation

Equations (4)–6) could be estimated using Monte Carlo integration similar to the parametric g-formula,31 using correctly specified parametric models, as in other contexts.32–37 A key distinction from these proposals is what the models condition on. The outcome models condition on: (a) allowable and non-allowable covariates in the observed and counterfactual scenarios for blacks, (b) only allowable covariates in the observed scenario among whites. The target factor models condition on: (a) allowable and non-allowable covariates in the observed scenario for blacks, (b) only allowable covariates in the observed scenario for whites and the counterfactual scenario for blacks. Other algorithms are possible (see eAppendix) but this one does not require non-allowables to be measured or even defined among whites.

Because simulation-based approaches are computationally intensive and require correctly specifying several models, we present two simple weighting-based estimators that can be implemented with standard statistical software routines (briefly described in the eAppendix). In the health equity context, these encompass existing estimators in the economics,38–40 sociology,41,42 biostatistics and epidemiology literatures,43–48 including those used to estimate natural direct and indirect effects,49,50 path-specific effects,51 interventional effects,11,12,46 and discrimination52,53 under certain allowability choices, and novel adaptations under others.

Ratio of Mediator Probability Weighting Estimation

The first weighting procedure is based on a ratio of probabilities for treatment intensification . The disparity reduction (2) and residual (3) under the intervention are estimated by comparing weighted means for blacks and whites. First, we estimate the observed proportion with uncontrolled hypertension among blacks, standardized for the outcome-allowable covariates :

| (7a) |

where the weight

| (7b) |

Next, we estimate the observed proportion with uncontrolled hypertension among whites, standardized for the outcome-allowable covariates :

| (8a) |

where the weight

| (8b) |

Last, we estimate the counterfactual proportion with uncontrolled hypertension among blacks under the intervention , which depends on the outcome- and target-allowable covariates and . Like the observed outcomes, the estimated counterfactuals are standardized for the outcome-allowable covariates :

| (9a) |

where the weight

| (9b) |

The counterfactual disparity reduction is obtained by subtracting (9a) from (7a), and the residual by subtracting (8a) from (9a).

Inverse Odds Ratio Weighting Estimation

The second weighting procedure is based on a ratio of inverted odds for race . The disparity reduction (2) and residual (3) under the intervention are estimated by comparing weighted means for blacks and whites. The observed proportions with uncontrolled hypertension among black and whites, standardizing for the outcome-allowable covariates , are respectively given in (7a) and (8a). The counterfactual proportion with uncontrolled hypertension among blacks under the intervention , standardized for the outcome-allowable covariates , is given by:

| (10a) |

where the weight

| (10b) |

When all covariates are treated as allowable, the middle term in (10b) cancels and does not need to be estimated. As with ratio of mediator probability weighting estimation, the disparity reduction is estimated by subtracting (10a) from (7a), and the disparity residual by subtracting (8a) from (10a). Finally, with both ratio of mediator probability and inverse odds ratio weighting estimation, each of the weights are multiplied by a factor of if the distribution of outcome-allowable covariates that standardizes the disparity measure is drawn from blacks, and by a factor of if drawn from whites.

A Closer Look at Existing Estimators

Estimators of natural and path-specific effects, their analogues, and the Oaxaca–Blinder decomposition are often applied to study disparities. We now use our general expressions to examine these estimators and the equity value judgments they convey (see eAppendix for a formal discussion). Many of these estimators were developed in the context of mediation analysis to study the effects of exposures and others to measure discrimination.5,54,55 When these estimators are used to study disparities, the decomposition estimands they identify are not always meaningful. The problem arises because of how they adjust for covariates. They implicitly define outcome disparities and interventions in ways that often ignore principles of modifiability, amenability to intervention, social contract, and purpose. Our generalized estimators explicitly consider allowable and non-allowable partitions, so users can be more intentional.

Natural Indirect Effect Analogue

Estimators of the natural direct and indirect effects include the regression approaches of Valeri and VanderWeele56 and Breen et al.,57 ratio of mediator probability weighting of Hong,41,42 natural effect models of Lange et al.;43 inverse odds ratio weighting of Tchetgen Tchetgen;45 propensity-score weighting of Huber;58 imputation approaches of Albert59 and Vansteelandt, Bekaert, and Lange;60 simulation approaches of Imai et al.33 and Wang et al.;34 and targeted maximum likelihood estimation of Zheng.48 In our example, these estimate the observed disparity (1) by conditioning the entire analysis on all covariates needed to de-confound the relationship between treatment decisions and hypertension control (or by standardizing across race). This renders all covariates as outcome-allowable. This is problematic because pre-existing diabetes, low educational attainment, and lack of private insurance are risk factors for poor hypertension control and are more common among blacks. Moreover, their effects on hypertension control are amenable to intervention. Thus, treating these pre-existing conditions as outcome-allowable artefactually diminishes the amount of unjust difference to be studied. Furthermore, these approaches estimate the disparity reduction (2) by allowing the hypothetical intervention on treatment intensification to depend on all covariates. This renders all covariates as target-allowable. This is problematic because, by ignoring the social contract, racial differences in treatment intensification that operate through racial differences in educational attainment would persist.

Path-Specific Effect Analogues

Estimators of path-specific effects and their interventional analogues have also been applied to study disparities. In our example, all would estimate the observed disparity as (1) by conditioning the entire analysis on age and sex, treating them as outcome-allowable (belonging to ). But they differ in how they would treat covariates affected by race, which in our example are educational attainment, private insurance, diabetes, and baseline blood pressure. The weighting estimator proposed by VanderWeele, Vansteelandt, and Robins46 would treat such covariates as non-allowable (all belonging to , leaving empty). Therefore, in estimating the disparity reduction as (2), this intervention to set treatment decisions would only depend on age and sex. This is problematic because our society has generally agreed that treatment decisions should depend on clinical needs. Respecting the social contract would assign clinical needs as target-allowable. In contrast, the weighting approach proposed by Zheng and Van Der Laan48 (and, upon recoding race, that of Miles et al.44), would estimate the disparity reduction (2) by treating all race-affected covariates as allowable (all belonging to , leaving empty). This intervention to set treatment decisions would depend not only on clinical needs but also educational attainment and private insurance. This is problematic because, as we argued with the natural indirect effect analogue, medical treatment decisions should not hinge on education or private insurance.Finally, a regression-based estimator of Jackson and VanderWeele5 and a simulation-based estimator proposed by Vansteelandt and Daniel36 make the same allowability choice as VanderWeele, Vansteelandt, and Robins.46 Additionally, the latter identifies a path-specific effect that does not map to the disparity reduction (2) in the presence target-outcome confounders affected by race, as in our motivating example, but rather the differential impact of two interventions (see eAppendix).

Oaxaca–Blinder Decompositions

The Oaxaca–Blinder Decomposition52,53 has also been applied to study disparities. The approach estimates the disparity reduction (2) by using linear models to regress the outcome on treatment intensification and all covariates and carrying out what is known as a detailed decomposition with respect to treatment intensification.5 This studies a marginal racial difference in hypertension control, with a hypothetical intervention to remove marginal differences in treatment intensification. Effectively, it treats all covariates as neither outcome-allowable nor target-allowable, leaving and empty. All covariates are treated as non-allowable and included through only to control for confounding. Alternatively, re-weighting estimators38,39 of the Oaxaca–Blinder decomposition have been widely used. Here, the racial difference in hypertension control conditions on no covariates, leaving empty, but the hypothetical intervention on treatment intensification conditions on all covariates, by including them in . Thus, no covariates are treated as outcome-allowable but all are treated as target-allowable. These allowability assignments share the problems listed for the estimators of natural and path-specific effect analogues.

A Meaningful Estimator

In our example, the many existing estimators we examined do not map to meaningful estimands because of the implicit allowability choices they make, which are summarized in Table 1. We could, in adapting the general formulae and weighting expressions, choose to deem age and sex as outcome- and target-allowable (by including them in ), respecting principles of modifiability and amenability to intervention, and deem baseline blood pressure and diabetesas exclusively target-allowable (by including them in ), respecting the social contract. Doing so would treat educational attainment and private insurance as non-allowable (by including them in ), using them to adjust for confounding but not to define the outcome disparity or hypothetical intervention.

Table 1.

Allowability Designations of Estimators

| 1. Oaxaca–Blinder Decomposition via Linear Models52,53: All covariates are considered non-allowable | |||

| 2. Oaxaca–Blinder Decomposition Estimator via Reweighting Functions: No covariates considered outcome-allowable; all covariates are considered target-allowable38,39 | |||

| 3. Natural Direct/Indirect Effect Analogue Estimators33,41–43,48,56–58: All covariates are considered outcome- and target-allowable | |||

| 4. Path-Specific Effect Analogue (I & II) Estimator5,36,46: Demographic covariates considered outcome- and target-allowable; remaining covariates considered non-allowable | |||

| 5. Path-Specific Effect Analogue (III) Estimator44,47: Demographic covariates outcome- and target-allowable; remaining covariates considered target-allowable | |||

| 6. A Meaningful Estimator: Demographic covariates considered outcome- and target-allowable; clinical covariates considered target-allowable; socioeconomic covariates considered non-allowable |

Abbreviations: outcome- (and target-) allowable covariates, exclusively target-allowable covariates, non-allowable covariates, the empty set; List of covariates include age, sex, educational attainment, private health insurance, diabetes, baseline blood pressure

Discussion

We have shown how causal decomposition analysis can incorporate equity concerns by partitioning covariates into allowable and non-allowable subsets (the latter used for identification). When a covariate is deemed outcome-allowable, its contribution is removed so that we are left with a difference we consider unjust. The hypothetical intervention to remove disparities in a targeted factor is administered within levels of target-allowable covariates, so that the intervention is equitable. We have discussed how allowability choices can consider issues of modifiability, amenability to intervention, social contract, and purpose, reflecting value judgments about equity. We provided generalized non-parametric formulae and weighting-based estimators that are defined in terms of allowable and non-allowable subsets. Last, we discussed when these estimators reduce to existing ones under certain value judgements, unifying and clarifying various approaches from biostatistics, epidemiology, economics, and sociology in the health equity context.

Our proposal has implications for study design in causal decomposition analysis. Researchers should consider variables needed to sensibly measure disparity, and whether these are measured by the start of follow-up with common support among blacks and whites. When our estimators are used, in particular ratio of mediator probability weighting estimation and formulae (4)–(6) estimated by Monte-Carlo integration, the non-allowables only need to be defined and measured among blacks. This is important given the way in which some non-allowable constructs, such as racial discrimination, may occur almost exclusively with racial or ethnic minorities.8

Regarding disparity definition, by only discussing additive measures of disparity across more vs. less marginalized groups, and by ignoring group size, we implicitly entertained several value judgments.16,17,22 Our results easily extend to other scales such as the risk ratio or odds ratio. Our approach involved a single axis of disadvantage, but could be extended to study intersectional disparities.7,8,61 Regarding disparity measurement, selected populations induce correlations between race and outcomes through collider-stratification,62 as in our example. Because selection occurs pre-target and conditional exchangeability nonetheless holds, we still have causal identification.4 The impact and interpretation of this important issue for disparity measurement is left for future work.

Regarding estimation, our approach focused on a single target, and continuous and (even non-rare) binary mean outcomes, allowing for race-target, race-covariate, target-covariate, and covariate-covariate interactions. Considering earlier work on ratio of mediator probability and inverse odds ratio weighting estimation,38,39,43,45 and also simulation-based estimation,32 our approach should extend to multiple targets, distributional outcomes, repeated outcomes, and survival analysis but this is left for future work. Regarding the intervention, we focused on categorical targets. Extensions to continuous targets could involve estimating conditional densities, expanding on earlier work,32,38,39 but this may prove difficult with several covariates. The weights must be estimated using correctly specified models (see eAppendix). Our focus was on conceptual issues in definition and their relevance for estimation. Future work will consider practical guidance in implementation.

Conclusion

We have outlined a framework for incorporating equity concerns into causal decomposition analysis. Our contributions should be of wide interest, particularly when there are baseline differences in non-modifiable factors or when hypothetical interventions concern socially distributed goods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding

This research was supported by a grant from the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (K01HL145320).

Footnotes

Editor’s Note: A related article appears on p. XXX.

References

- 1.Braveman PA, Kumanyika S, Fielding J, Laveist T, Borrell LN, Manderscheid R, Troutman A. Health disparities and health equity: the issue is justice. Am J Public Health 2011;101Suppl1:S149–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cooper LA, Hill MN, Powe NR. Designing and evaluating interventions to eliminate racial and ethnic disparities in health care. J Gen Intern Med 2002;17(6):477–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.VanderWeele TJ. Mediation Analysis: A Practitioner’s Guide. Annual Review of Public Health 2016;37(1):17–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.VanderWeele TJ, Robinson WR. On the causal interpretation of race in regressions adjusting for confounding and mediating variables. Epidemiology 2014;25(4):473–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jackson JW, VanderWeele TJ. Decomposition Analysis to Identify Intervention Targets for Reducing Disparities. Epidemiology 2018;29(6):825–835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jackson JW. On the Interpretation of Path-specific Effects in Health Disparities Research. Epidemiology 2018;29(4):517–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jackson JW. Explaining intersectionality through description, counterfactual thinking, and mediation analysis. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2017;52(7):785–793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jackson JW, VanderWeele TJ. Intersectional decomposition analysis with differential exposure, effects, and construct. Soc Sci Med 2019;226:254–259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boonyasai RT, Rakotz MK, Lubomski LH, Daniel DM, Marsteller JA, Taylor KS, Cooper LA, Hasan O, Wynia MK. Measure accurately, Act rapidly, and Partner with patients: An intuitive and practical three-part framework to guide efforts to improve hypertension control. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2017;19(7):684–694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Balsa AI, Seiler N, McGuire T, Bloche MG. Clinical uncertainty and healthcare disparities. American Journal of Law & Medicine 2003;29(2–3):203–219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Didelez V, Dawid AP, Geneletti S. Direct and Indirect Effects of Sequential Treatments. Conference on Uncertainty in Artificial Intelligence. Arlington, Virginia: AUAI Press, 2006;138–146. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Geneletti S. Identifying direct and indirect effects in a non-counterfactual framework. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series B 2007;69(2):199–216. [Google Scholar]

- 13.James SA. Epidemiologic research on health disparities: some thoughts on history and current developments. Epidemiol Rev 2009;31:1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Williams DR, Lawrence JA, Davis BA. Racism and Health: Evidence and Needed Research. Annu Rev Public Health 2019;40:105–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Keppel K, Pamuk E, Lynch J, Carter-Pokras O, Kim I, Mays V, Pearcy J, Schoenbach V, Weissman JS. Methodological issues in measuring health disparities. Vital Health Stat 2 2005(141):1–16. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Asada Y. Which Health Distributions are Inequitable? Health Inequality: Mortality and Measurement. Toronto, Canada: University of Toronto Press, 2007;27–52. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harper S, King NB, Meersman SC, Reichman ME, Breen N, Lynch J. Implicit value judgments in the measurement of health inequalities. Milbank Q 2010;88(1):4–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Messer LC. Invited commentary: measuring social disparities in health--what was the question again? Am J Epidemiol 2008;167(8):900–4; author reply 908–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fabienne P, Evans T. The Social Basis of Disparities in Health. In: Evans T, Whitehead M, Diderichsen F, Bhuiya A, Wirth M, eds. Challenging Inequities in Health: From Ethics to Action. New York, New York: Oxford University Press, 2009;24–33. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cook BL, McGuire TG, Zaslavsky AM. Measuring racial/ethnic disparities in health care: methods and practical issues. Health Serv Res 2012;47(3 Pt 2):1232–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Duan N, Meng XL, Lin JY, Chen CN, Alegria M. Disparities in defining disparities: statistical conceptual frameworks. Stat Med 2008;27(20):3941–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Braveman P. Health disparities and health equity: concepts and measurement. Annu Rev Public Health 2006;27:167–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Duran DG, Pérez-Stable EJ. Novel Approaches to Advance Minority Health and Health Disparities Research. Am J Public Health 2019;109(S1):S8–s10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Institute of Medicine. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Adler N. Appendix D. Overview of Health Disparities. In: Institute of Medicine, ed. Examining the Health Disparities Research Plan of the National Institutes of Health: Unfinished Business. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press., 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Krieger N. On the Causal Interpretation of Race. Epidemiology 2014;25(6):937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brook RH, Iezzoni LI, Jencks SF, Knaus WA, Krakauer H, Lohr KN, Moskowitz MA. Symposium: case-mix measurement and assessing quality of hospital care. Health Care Financ Rev 1987;Spec No:39–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Braithwaite RS. Risk Adjustment for Quality Measures Is Neither Binary nor Mandatory. JAMA, 2018;319(20):2077–2078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hernan MA, Robins JM. Estimating causal effects from epidemiological data. J Epidemiol Community Health 2006;60(7):578–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jackson JW, Arah OA. Invited Commentary: Making Causal Inference More Social and (Social) Epidemiology More Causal. Am J Epidemiol 2020;189(3):179–182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Taubman SL, Robins JM, Mittleman MA, Hernán MA. Intervening on risk factors for coronary heart disease: an application of the parametric g-formula. Int J Epidemiol 2009;38(6):1599–611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Machado J, Mata J. Counterfactual decomposition of changes in wage distributions using quantile regression. Journal of Applied Econometrics 2005;20(4):445–465. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Imai K, Keele L, Tingley D. A general approach to causal mediation analysis. Psychol Methods 2010;15(4):309–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang A, Arah OA. G-computation demonstration in causal mediation analysis. Eur J Epidemiol 2015;30(10):1119–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lin S-H, VanderWeele TJ. Interventional Approach for Path-Specific Effects. Journal of Causal Inference 2017;5(1):1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vansteelandt S, Daniel RM. Interventional Effects for Mediation Analysis with Multiple Mediators. Epidemiology 2017;28(2):258–265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sudharsanan N, Bijlsma M. A Generalized Counterfactual Approach to Decomposing Differences Between Populations. MDPIDR Working Papers and Preprints 2019;WP-2019–004:1–49. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Barsky R, Bound J, Charles KK, Lupton JP. Accounting for the Black-White Wealth Gap: A Nonparametric Approach. Journal of the American Statistical Association 2002;97(459):663–673. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dinardo J, Fortin N, Lemieux T. Labor Market Institutions and the Distribution of Wages, 1973–1992: A Semiparametric Approach. Econometrica 1996;64(5):1001–1044. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Huber M. Causal Pitfalls in the Decomposition of Wage Gaps. Journal of Business and Economic Statistics 2015;33(2):179–191. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hong G. Ratio of mediator probability weighting for estimating natural direct and indirect effects. Joint Statistical Meeting. Alexandria, Virginia: American Statistical Association, 2010;2401–2415. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hong G, Deutsch J, Hill HD. Ratio-of-Mediator-Probability Weighting for Causal Mediation in the Presence of Treatment-by-Mediator Interaction. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics 2015;40(3):307–340. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lange T, Vansteelandt S, Bekaert M. A simple unified approach for estimating natural direct and indirect effects. Am J Epidemiol 2012;176(3):190–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Miles CH, Shpitser I, Kanki P, Meloni S, Tchetgen Tchetgen EJ. On semiparametric estimation of a path-specific effect in the presence of mediator-outcome confounding. Biometrika 2019;107(1):159–172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tchetgen Tchetgen EJ. Inverse odds ratio-weighted estimation for causal mediation analysis. Stat Med 2013;32(26):4567–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vanderweele TJ, Vansteelandt S, Robins JM. Effect decomposition in the presence of an exposure-induced mediator-outcome confounder. Epidemiology 2014;25(2):300–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zheng W, van der Laan M. Longitudinal Mediation Analysis with Time-varying Mediators and Exposures, with Application to Survival Outcomes. J Causal Inference 2017;5(2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zheng W, van der Laan MJ. Targeted maximum likelihood estimation of natural direct effects. Int J Biostat 2012;8(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Robins JM, Greenland S. Identifiability and exchangeability for direct and indirect effects. Epidemiology 1992;3(2):143–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Direct Pearl J. and indirect effects. In: Breese K, Koller D, eds. Uncertainty in Artificial Intelligence. San Francisco: Morgan Kaufmann, 2001;411–420. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Daniel RM, De Stavola BL, Cousens SN, Vansteelandt S. Causal mediation analysis with multiple mediators. Biometrics 2015;71(1):1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Blinder A. Wage Discrimination: Reduced Form and Structural Estimates. The Journal of Human Resources 1973;8(4):436. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Oaxaca R. Male-Female Wage Differentials in Urban Labor Markets. International Economic Review 1973;14(3):693–709. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nguyen TQ, Schmid I, Stuart EA. Clarifying causal mediation analysis for the applied researcher: Defining effects based on what we want to learn. Psychol Methods 2020;(in press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fortin N, Lemieux T, Firpo S. Decomposition Methods in Economics. Handbook of Labor Economics 2011;4:1–102. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Valeri L, Vanderweele TJ. Mediation analysis allowing for exposure-mediator interactions and causal interpretation: theoretical assumptions and implementation with SAS and SPSS macros. Psychol Methods 2013;18(2):137–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Breen R, Karlson KB, Holm A. Total, Direct, and Indirect Effects in Logit and Probit Models. Sociological Methods & Research 2013;42(2):164–191. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Huber M. Identifying causal mechanisms (primarily) based on inverse probability weighting. Journal of Applied Econometrics 2014;29(6):920–943. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Albert JM. Distribution-free mediation analysis for nonlinear models with confounding. Epidemiology 2012;23(6):879–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Vansteelandt S, Bekaert M, Lange T. Imputation Strategies for the Estimation of Natural Direct and Indirect Effects. Epidemiologic Methods 2012;1(1):130–158. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jackson JW, Williams DR, VanderWeele TJ. Disparities at the intersection of marginalized groups. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2016;51(10):1349–1359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Smith LH. Selection Mechanisms and Their Consequences: Understanding and Addressing Selection Bias. Current Epidemiology Reports 2020. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.