Abstract

Calpains are a family of Ca2+-dependent cysteine proteases that participate in various cellular processes. Calpain 3 (CAPN3) is a classical calpain with unique N-terminus and insertion sequence 1 and 2 domains that confer characteristics such as rapid autolysis, Ca2+-independent activation and Na+ activation of the protease. CAPN3 is the only muscle-specific calpain that has important roles in the promotion of calcium release from skeletal muscle fibers, calcium uptake of sarcoplasmic reticulum, muscle formation and muscle remodeling. Studies have indicated that recessive mutations in CAPN3 cause limb-girdle muscular dystrophy (MD) type 2A and other types of MD; eosinophilic myositis, melanoma and epilepsy are also closely related to CAPN3. In the present review, the characteristics of CAPN3, its biological functions and roles in the pathogenesis of a number of disorders are discussed.

Keywords: CAPN3, muscle formation, muscle remodeling, limb-girdle muscular dystrophy type 2A

1. Overview of CAPN3

Discovery

In 1989, Sorimachi et al (1) discovered a molecular clone named p94 that encodes a novel calcium-dependent protease comprising 821 amino acid residues with a relative molecular mass of 94 kDa. In 2013, p94 was renamed calpain 3 (CAPN3) (2), or calcium-activated neutral protease, by the American Association of Experimental Biology. In humans, CAPN3 is located in the chromosomal region 15q15.1-q21.1 (3). Mainly expressed specifically in skeletal muscle (1), the mRNA of CAPN3 has also been detected in the early embryonic heart, but it will gradually disappear from the ventricular area, and finally, only the transcript of CAPN3 is present (4,5). In addition, CAPN3 is also expressed in the cytoplasm and nucleus of neuron-like PC12 cells, as well as in rat astrocytes and in the brain of Microcebus (6,7).

Structure

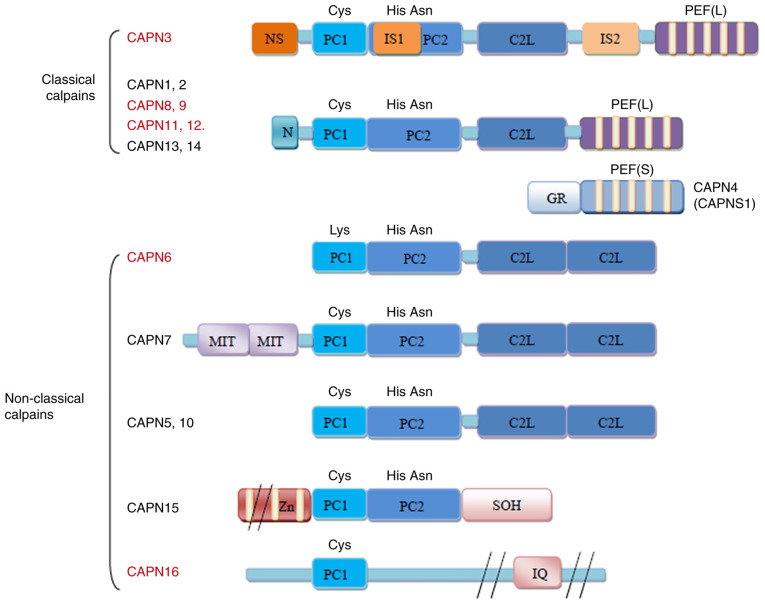

So far, the calpain family has 16 members, including classic calpains and non-classical calpains (summarized in Fig. 1). As a classic calpain, CAPN3 exhibits a large subunit containing four domains (I-IV). Domain I is distinctly different from the other domains. Domain II is a conserved cysteine protease domain comprising protease core domain 1 (PC1) and PC2 that confer protease activity. Domain III, also known as the calpain-type β-sandwich domain (CBSW or C2L), is responsible for protein structural changes upon CAPN3 activation. Domain IV, or the penta-EF-hand (E, E-helix; F, F-helix) (PEF) domain, mainly participates in calcium ion binding and CAPN3 homodimerization. The sequences of domain II and IV in CAPN3 are homologous with those in other calpains (1).

Figure 1.

Structure of the human calpains. The calpains presented in red are predominantly expressed in specific tissues or organs, while those in black are more widely expressed. The major difference in the structure of CAPN3 is that it contains three additional insertion sequences, namely NS at the N-terminus, IS1 of PC2 and IS2 between CBSW/C2L and PEF (L). Small subunits are not present in CAPN3. CAPN3, calpain 3; GR, Gly-rich domain; MIT, microtubule-interacting and transport motif; Zn, zinc-finger motif; SOH, small optic lobes product homology domain; IQ, calmodulin-interacting motif; NS, N-terminus; IS1, insertion sequence 1; PC1, protease core domain 1; PEF, penta-EF-hand (E, E-helix; F, F-helix); CBSW/C2L, calpain-type β-sandwich.

In particular, CAPN3 contains three additional insertion sequences, namely the N-terminus (NS), insertion sequence 1 (IS1) of PC2 and IS2 between CBSW/C2L and PEF (L) (8). IS1, which interrupts the protease core, must be cleaved in order to be activated for substrate binding (9). The PEF domain is where four Ca2+ bind at positions 1, 2, 3 and 5 of EF-hand to promote CAPN3 homodimerization. In calpain, EF5 is used to form dimers independently of Ca2+ (10,11). In CAPN3, the addition of a CBSW domain at the NS enhances its trimer-forming properties. Therefore, CAPN3 actually forms a homotrimer. Although PEF domain deletion has been observed to abolish trimer formation, insertion of the CAPN3-specific sequences NS, IS1 and IS2 had no impact (12). Small subunits are not present in CAPN3 (1) (summarized in Fig. 1).

Various splice variants

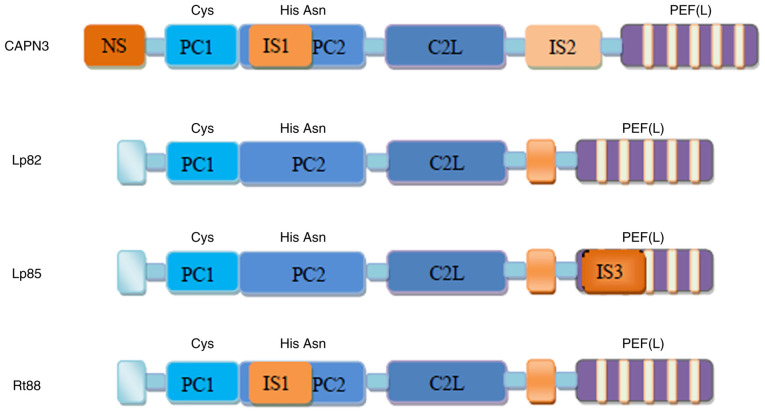

There are numerous different splice variants of CAPN3 (summarized in Fig. 2), such as Lp82 that is expressed in the cytoplasm of the lens, cortex and nuclear fibers of rodents (lack of exons 6, 15 and 16) (13,14), Lp85 (Lp82+IS3) that is expressed in the lens (15), Rt88 (Lp82+IS1) that is expressed in the retina and numerous other isoenzymes (with deleted exons 6, 15 and 16) that are expressed in the embryonic muscles (16,17). The cDNAs of CAPN3 variants are highly conserved and the differences in their expression patterns may be related to the function of each variant in specific tissues or different species (18). The IS1, IS2 and NS sequences that are either inserted or deleted in CAPN3 variants endow CAPN3 with numerous characteristics that are different from those of the original CAPN3.

Figure 2.

Representative CAPN3 isoforms generated by alternative splicing of CAPN3. Lp82, lack of exons 6, 15 and 16; Lp85, Lp82+IS3; Rt88, Lp82+IS1. IS3, insertion sequence 3; CAPN3, calpain 3; PEF, penta-EF-hand (E, E-helix; F, F-helix); NS, N-terminus; IS1, insertion sequence 1; PC1, protease core domain 1; C2L, calpain-type β-sandwich.

2. CAPN3 activation and inhibition

Platform element for inhibition of autolytic degradation (PLEIAD), also known as SUMO-interacting motif-containing protein 1/chromosome 5 open reading frame 25, is a multi-SUMO protein that is mainly located in the cytoplasm and occasionally in the sarcomere I zone. Studies have indicated that PLEIAD is a novel CAPN3 binding protein. The C-terminal N2A titin of PLEIAD, which is highly conserved in vertebrates, is able to inhibit the activity of CAPN3. The N-terminus of PLEIAD is able to bind to co-transcription factor C-terminal binding protein 1 (CTBP1) and CTBP1 is proteolyzed and functionally modified in COS7 cells expressing CAPN3. Other than CAPN3 inhibition, PLEIAD also has a role in CAPN3 substrate recruitment. Hence, PLEIAD is a novel CAPN3 regulator (19).

Calmodulin (CaM), a known calcium signal transducer, is able to bind CAPN3 at two sites located in the C2L domain to activate CAPN3 autolysis. CaM may also promote CAPN3-mediated cleavage of substrate titin in vivo. Therefore, CaM is the first positive regulator of CAPN3 autolysis (20,21).

3. Features of CAPN3

Autolysis

Since CAPN3 contains specific sequences NS, IS1 and IS2 that are not present in other calpains or proteases, CAPN3 exhibits unique characteristics. For instance, the complete autolysis of CAPN3 is rapid and is independent of Ca2+ activation (22). CAPN3 is so far the only intracellular enzyme that relies on Na+ activation.

The half-life of CAPN3 in vitro is <10 min and its fast autolysis rate is attributed to the presence of IS1 and IS2 (23). Under normal physiological conditions, CAPN3 undergoes intramolecular dissolution, producing a nick with its IS1 sequence. As autolysis continues, CAPN3 begins to hydrolyze exogenous substrates. The IS1 sequence then forms numerous small fragments and the remaining part constitutes the two achiral Ca2+ binding sites in the active center (24,25). Subsequent proteolysis of IS2 eventually inactivates CAPN3 (26). In the presence of IS1, the autolysis of CAPN3 is unable to be prevented even by calpain inhibitors. Binding between N2A connectin fragment and CAPN3 has been observed to inhibit IS2 proteolysis and subsequent dissociation of CAPN3 fragments (27).

Compared with other classical calpains, due to the presence of the PC2, CBSW and PEF domains, the required Ca2+ concentration for CAPN3 autolysis is only 0.1 mM with a normal physiological Na+ concentration in cells. The required Ca2+ concentration for CAPN3 activation is lower than that for other classical calpains (28,29).

In addition, CAPN3 may be activated by Na+ in vitro at a required Na+ concentration of 100 mM. Calcium binding site 1 (CBS-1) in PC1 is the binding site for Na+. In the absence of IS1 and IS2, CAPN3 loses its Na+ dependency (30). Therefore, the dependence of CAPN3 to Na+ requires synergy between CBS-1, IS1 and IS2.

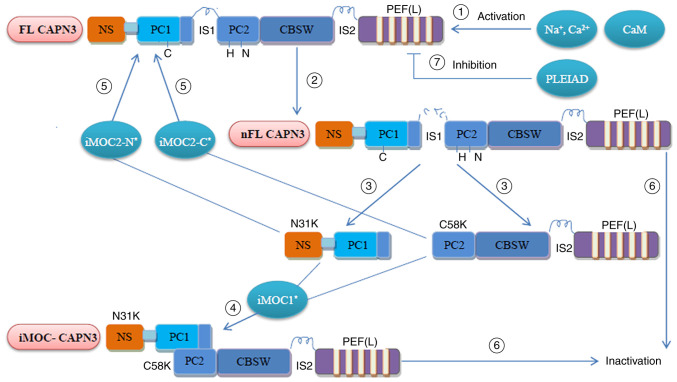

Regain of activity after inactivation

The rapid and continuous autolysis nature and the instability feature of CAPN3 allow CAPN3 to regulate its own activity (summarized in Fig. 3). Studies have indicated that intramolecular complementation (iMOC) between the two autolytic fragments of CAPN3 (N and C terminus) enables CAPN3 to regain the activity of the active core protease domain (31). Under appropriate conditions, the use of autolyzed fragments containing CAPN3 wild-type amino acid sequence through iMOC has been indicated to enable two different CAPN3 mutant molecules to amend each other, so that part of the CAPN3 mutant activity is restored (31,32).

Figure 3.

Regulation of CAPN3 activity. ① Translated FL-CAPN3 (FL-CAPN3) is activated by physiological Na+/Ca2+ and CaM; ② FL-CAPN3 undergoes intramolecular dissolution and the IS1 sequence produces a nick (but not dissociated), which is nFL-CAPN3; ③ N31K and C58K are dissociated from each other; ④ N31K and C58K were recombined into active CAPN3 (iMOC-CAPN3) by iMOC1, and its location and function were completely different from FL/nFL-CAPN3; ⑤ N31K/C58K and full-length CAPN3 reorganization by iMOC2-N/C to restore partial activity; ⑥ The IS2 and other sites in nFL-CAPN3 undergo further autolysis and the recombined iMOC-CAPN3 enters the next round of autolysis, and will eventually be inactivated; ⑦ PLEIAD is able to bind to FL-CAPN3 and inhibit CAPN3 activity through its C-terminus. FL-CAPN3, full-length calpain 3; nFL-CAPN3, nick full-length CAPN3; PEF, penta-EF-hand (E, E-helix; F, F-helix); NS, N-terminus; IS1, insertion sequence 1; PC1, protease core domain 1; CBSW, calpain-type β-sandwich; iMOC, intramolecular complementation; PLEIAD, platform element for inhibition of autolytic degradation; CaM, calmodulin.

4. Physiological function

Calpain is a 'regulatory protease' that requires Ca2+ for function in cells. It processes substrates through limited and specific proteolysis to facilitate Ca2+ signal transduction and regulate various protein functions in cells (33). CAPN3 is the only muscle-specific member of the calpain family. It is expressed in the myofibril, cytoplasm and triad components of skeletal muscle (34). In resting human skeletal muscle, most (87%) CAPN3 is expressed in myofibrils and only a small proportion (<10%) exists in an autolyzed state (35). The biological function of CAPN3 is closely related to its location in the cell. Nuclear localized CAPN3 is related to cell survival (7,36), while CAPN3 localized in the cytoplasm may be related to the control of cell motility or skeletal plasticity (37,38). CAPN3 has both proteolytic and non-proteolytic functions.

CAPN3 promotes calcium release of skeletal muscle fibers and calcium uptake of sarcoplasmic reticulum

The triad is the structural component of the muscle responsible for calcium transport and excitation-contraction coupling. Aldolase is also present as one of the components in muscles rich in triads. Glycolytic enzyme aldolase A (AldoA) is the binding partner of CAPN3. CAPN3 is able to degrade AldoA, but AldoA is not the body substrate of CAPN3. Aldolase and CAPN3 are able to interact with ryanodine receptor (RyR) to form the main calcium release channel. Compared with the wild-type, the levels of AldoA and RyR associated with the triplet in CAPN3-deficient muscle are decreased; hence, CAPN3 helps maintain the integrity of the triplet in skeletal muscle, which then promotes the release of calcium from muscle fibers (39,40).

The Na+-Ca2+ exchanger isoform 3 (NCX3) is also expressed in the triad of skeletal muscle. A number of studies have indicated that NCX3 is associated with the increased Ca2+ content in the sarcoplasmic reticulum. CAPN3 is able to increase the activity of NCX3, but only the NCX3-AC variant, which is mainly expressed in the skeletal muscle, is sensitive to calpain. Increased intracellular levels of Ca2+ ([Ca2+]i) or [Na+]i significantly increase cellular Ca2+ uptake through the reverse mode of NCX3 ingestion. Exercise causes excitation-contraction uncoupling, NCX3 increases the uptake of Ca2+ and supplements Ca2+ in the sarcoplasmic reticulum (41).

CAPN3 promotes muscle formation and muscle remodeling

CAPN3 mRNA is expressed at high levels in muscles (42). CAPN3 is distributed in the amorphous plaques of myoblasts, the area close to the myotube nucleus, the adhesion plaques and stress fibrous structures of myotubes and the filaments of fibroblasts (43). CAPN3 is located in the Z line and N2 line regions of the sarcomere by binding to its chaperone protein titin (33). The most characteristic function of CAPN3 is that it is located in the sarcomere. CAPN3 is an important protein required for muscle formation and a prerequisite for maintaining normal muscle function (42).

Muscle formation

CAPN3 is mostly inactive in muscles. It may be activated by autolysis in the active site to destroy the cytoskeleton of actin. By lysing several endogenous proteins, the sarcomere and sarcomere components are lysed; this may enhance the adaptability of muscle cells to external and/or internal stimuli. Titin and filamin C, substrates of CAPN3, are co-localized in multiple locations within the cytoskeleton structure in the body (38). Therefore, CAPN3 is a muscle cytoskeleton regulator.

As a scaffold protein, CAPN3 may have a role during the early stages of myogenesis. Muscle-specific filamin C (FLNC) is a candidate substrate of CAPN3. The C-terminus of FLNC binds to the cytoplasmic domain of δ- and γ-glycans. CAPN3 cleaves the C-terminus of FLNC in living cells in order to eliminate the interaction between FLNC and δ- and γ-glycans, while the FLNC-sarcoglycan interaction may have a regulatory effect on CAPN-mediated myoblast fusion (44). M-cadherin has a role in the fusion of myoblasts. CAPN3 is able to cut M-cadherin and β-catenin. In the absence of CAPN3, M-cadherin and β-catenin accumulate abnormally on the myometrial membrane, while myoblasts and myotubes continue to fuse, which may inhibit muscle differentiation steps, such as integrin complex body rearrangement and sarcomere assembly, inhibiting the formation of sarcomere (45). Therefore, down-regulation of CAPN3 leads to a decrease in the number of muscle cells and in the size of myotubes formed (43).

Muscle remodeling

During the development of myoblasts into fully differentiated myotubes in vitro, a number of 'reserve cells' are maintained. These reserve cells are closely related to satellite cells responsible for muscle regeneration. The level of endogenous CAPN3 mRNA expressed in the reserve cells is higher than that of proliferating myoblasts. CAPN3 is able to decrease the transcriptional activity of MyoD, a key myogenic regulator, through proteolysis in a manner that is independent of the ubiquitin-proteasome degradation pathway, participate in the establishment of the reserve cell bank and promote the renewal of satellite cell compartments (46). The expression of CAPN3 mRNA after muscle injury (denervation-devasculaization) is related to the muscle wet weight ratio. CAPN3 is upregulated from day 7 to 14 in order to promote satellite cell renewal by inhibiting cell differentiation. CAPN3 is decreased significantly from day 14 to 28 in order to promote myoblast differentiation in L6 cells and enhance the recovery function. Isoforms lacking exon 6 dominate the early regeneration process (47,48).

Substrates of CAPN3 are divided into two major functional categories: Metabolic substrates and myofibrils, including myosin light chain 1 (MLC1). CAPN3 has a proteolytic effect on MLC1 in vitro (49). Among these substrates, there are three E3 SUMO ligases belonging to the protein inhibitor of activated states (PIAS) family. CAPN3 is able to cleave PIAS protein and negatively regulate the activity of PIAS3 sumoylase. In the muscle tissue of patients with limb-girdle muscular dystrophy (MD) type 2A (LGMD2A), SUMO2 is dysregulated (50). Therefore, CAPN3, through fast-acting one-way proteolytic switch, has a significant role in muscle remodeling. CAPN3 also has a role upstream of the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway by targeting ubiquitination and proteasome degradation. Increased expression of CAPN3 has been reported to enhance ubiquitination and promote sarcomere remodeling by cutting and releasing myofibrillar proteins (51).

In addition, in the triplet, CAPN3 co-localizes with calmodulin kinase IIβ (CaMKIIβ). CAPN3 and CaMKIIβ have a role in gene regulation during adaptive endurance exercise. Muscles of CAPN3 knockout mice (C3KO) have been reported to exhibit decreased triplet integrity and weakened CaMKIIβ signaling. After atrophy induction, it has been indicated that C3KO muscles were unable to activate CaMKIIβ signaling and inducible heat shock protein 70, and that the expression of cell stress-related genes remained unchanged; hence the inflammatory response required to promote muscle recovery was absent. Meanwhile, C3KO muscles have been indicated to exhibit decreased immune cell infiltration and decreased expression of myogenic genes (34). In patients with severe LGMD2A, recent muscle regeneration determined by the number of neonatal myosin heavy chain/vimentin-positive fibers was significantly decreased. Compared with those in patients with residual CAPN3, the signs of abnormal regeneration of spiral fibers were highly enhanced in patients with complete CAPN3 deficiency (52). Therefore, during sarcomere remodeling, CAPN3 is necessary for the muscle regeneration process.

Promotion of neurodegenerative processes

The IκBα/nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) signaling pathway is related to cell apoptosis and it regulates the process of neurodegeneration by direct alteration of gene expression in neurons. Loss of CAPN3 proteolytic activity has been observed to severely interfere with the IκBα/NF-κB pathway (53). On the contrary, when CAPN3 is activated, the IκBα/CAPN3 complex is formed. Increased levels of calpain-dependent IκBα cleavage products in the nucleus subsequently stimulate the activation of nuclear CAPN3-like proteases in neurons and calpain-dependent cell death. The proteolysis of IκBα, which activates the IκBα/NF-κB pathway, promotes neurodegenerative processes (7).

A role in astrocyte plasticity and/or motility

Most astrocytes in the brains of rats and Microcebus co-express glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), which is an ubiquitous target of calpain in vitro (54). GFAP is necessary for the movement of astrocytes (55). CAPN3 is located in the cytoplasm of astrocytes, where GFAP is closely related to CAPN3. In addition, cells expressing GFAP and CAPN3 are particularly common in the sub-ventricular zone (SVZ) and SVZ astrocytes are actually the progenitor cells of stem cells that produce new neurons (56). Therefore, CAPN3 may have a role in astrocyte motility or cytoskeletal plasticity (6).

5. CAPN3 in diseases

Since calpain participates in various physiological processes in cells, dysregulation of CAPN3 may cause different diseases (Table I), such as MD, myositis or epilepsy.

Table I.

CAPN3 protein and genes in different diseases.

| A, MD

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Disease | Protein expressiona | Gene mutationa | (Refs.) |

| Limb-girdle MD type 2A | Normal or low expression | Mutation | (59-69) |

| Limb-girdle MD type 2B | Low expression | Mutation | (86,87) |

| Limb-girdle MD type 2J | Low expression | - | (89,90) |

| Tibial MD | Low expression | - | (89,90) |

| Duchenne MD | Low expression | - | (91) |

| Facioscapulohumeral MD | Overexpression | Mutation | (92-94) |

| Ullrich congenital MD | Low expression | - | (95) |

|

| |||

| B, Other diseases

| |||

| Disease | Protein expression | Gene mutation | (Refs.) |

|

| |||

| Idiopathic eosinophilic myositis | - | Mutation | (96) |

| Inclusion body myositis | Low expression | - | (97,98) |

| Rhabdomyolysis syndrome | Low expression | - | (99,100) |

| Melanoma | Overexpression | - | (101-106) |

| Epilepsy | - | Mutation | (107,108) |

| Alzheimer's disease | Uncertain | - | (111) |

| Diabetes | Uncertain | - | (112,113) |

| Cardiovascular diseases | - | Mutation | (114,115) |

| Vitiligo | Overexpression | - | (116) |

| Age-related cataract | Overexpression | - | (117) |

Not all diseases have clear protein expression changes and gene mutations. MD, muscular dystrophy.

Muscular diseases

MD

MD is a group of muscular diseases caused by genetic factors characterized by progressive muscle weakness and degeneration of muscles that govern exercise. A common pathological feature is muscle atrophy accompanied by hyperplasia of fibrous tissue and adipose tissue. MD has a high degree of genetic heterogeneity characterized by autosomal dominant or recessive inheritance of genes (57). CAPN3 is closely related to the occurrence of a variety of MD.

LGMD2A

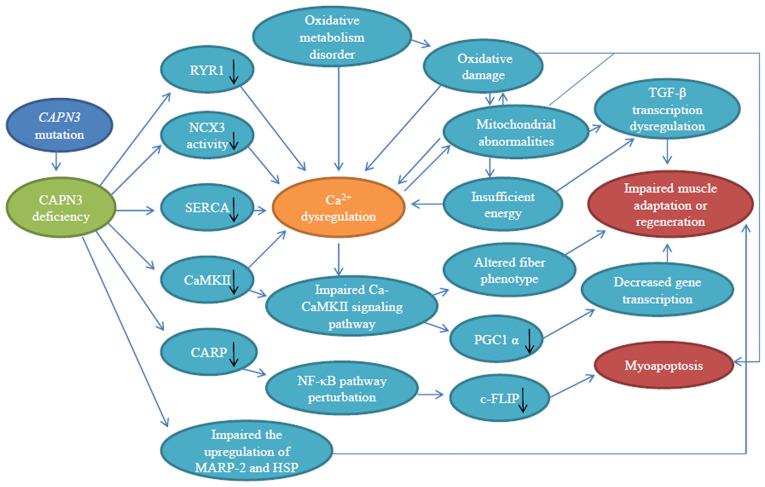

LGMD2A is the most commonly diagnosed type of LGMD, accounting for 30-40% of all LGMD cases (58). LGMD2A is caused by a recessive mutation in CAPN3. So far, >500 mutation sites have been reported. Different pathogenic CAPN3 mutations include missense mutations, frameshift mutations, nonsense mutations, deletions/insertions, splice site mutations and single mutations. Among them, missense mutations that are distributed along the entire CAPN3 gene are most common (59-64). These mutations have been observed to weaken CAPN3 proteolytic activity by affecting the protein inter-domain interactions, decrease CAPN3 autocatalytic activity by lowering its affinity towards Ca2+, cause complete or partial loss of CAPN3 protein (62,65-67) or result in changes of other characteristics of CAPN3. For instance, D705G and R448H mutations affect the ability and stability of CAPN3 to bind titin in vitro (68,69). These mutations have been reported to cause skeletal muscle Ca2+ imbalance (70,71), abnormal muscle adaptation (72,73), sarcomere disorder (74,75), oxidative damage (23,76), mitochondrial abnormality (42,77) and impaired muscle regeneration (77,78) (summarized in Fig. 4), which then lead to inflammation, necrosis, fibrosis, atrophy and progressive muscle degeneration. All these complications are the characteristics of LGMD2A.

Figure 4.

Schematic diagram of the pathogenic mechanism of CAPN3 deficiency. CAPN3 deficiency results in reduced levels of RyR1, SERCA, CaMKII and CARP, decreased NCX3 activity and impaired upregulation of MARP-2 and HSP, causing Ca2+ imbalance and compromise Ca-CaMKII and NF-κB downstream signaling pathways, which may lead to impaired gene transcription, mitochondrial abnormalities, oxidative damage and altered fiber phenotype. This eventually leads to abnormal muscle adaptation, myocyte apoptosis and impaired regeneration. Among these mechanisms, there are multiple feedback loops. Black arrows indicate a decline. CAPN3, calpain 3; RyR, ryanodine receptor; NCX3, Na+-Ca2+ exchanger isoform 3; SERCA, sarco-endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase; Ca-CaMKII, Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II; CARP, cardiac myotonic repeat protein; MARP-2, muscle ankyrin repeat protein 2; HSP, heat shock protein; PGC1α, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ coactlvator-1α; c-FLIP, cell FLICE inhibitor protein.

Dysregulation of Ca2+ in the skeletal muscles is a potential event of MD, including LGMD2A (71,79,80). As one of the constituents of the triplet, the absence of CAPN3, which destroys the triplet integrity, decreases the release of Ca2+ in the skeletal muscles. CAPN3 deficiency also leads to degradation and dysfunction of skeletal muscle sarco-endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase 1 and 2 proteins, resulting in impaired Ca2+ homeostasis in human myotubes (79) and NCX3 dysfunction, causing impaired reticular Ca2+ storage (41).

CAPN3 knockout studies have indicated that Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (Ca-CaMKII)-mediated signal transduction is impaired (81), which not only decreases the slow muscle fiber phenotype and the fast muscle fiber phenotype (82,83), but also lowers the level of p38 MAPK activation. Eventually, the level of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ coactivator-1α (PGC1α; a transcriptional co-regulator that coordinates muscle adaptive response) is decreased, leading to the decreased levels of transcription of genes involved in muscle adaptation (40). In addition, the loss of CAPN3 protease activity has been observed to impair the upregulation of muscle ankyrin repeat protein 2 and hsp, causing stress and muscle degeneration in skeletal muscles. Exercise has been indicated to exacerbate this change (73). In the end, long-term failure of muscles to adapt and reshape causes the occurrence of LGMD2A.

In addition, a multi-protein complex comprising CAPN3 and cardiac myotonic repeat protein (CARP) is present in the N2A region of the sarcomeric protein titin. CAPN3 regulates CARP subcellular localization by cleaving the N-terminus of CARP. The higher the activity of CAPN3, the more important is the retention of CARP's sarcomere. Overexpression of CARP decreases the DNA binding activity of NF-κB p65, a factor that exhibits anti-apoptotic effects. CAPN3 is unable to decrease the inhibitory effect of CARP on NF-κB, which may decrease the survival rate of muscle cells (84). In addition, the activity of anti-apoptotic factor cell FLICE inhibitor protein (c-FLIP) depends on the NF-κB pathway in normal muscle cells. CAPN3 is involved in regulating the expression of c-FLIP. CAPN3-dependent IκBα is expressed after NF-κB activation (75). In the muscle cells of patients with LGMD2A, NF-κB is activated under cytokine induction in the absence of CAPN3, IκBα accumulation prevents nuclear translocation of NF-κB, the NF-κB pathway is dysregulated, c-FLIP expression is downregulated, and finally, cell apoptosis and muscle shrinking occur (74,75).

CAPN3 deficiency may also weaken the antioxidant defense mechanism of skeletal muscles in LGMD2A patients [super- oxide dismutase (SOD)-1 and nuclear factor erythroid-2-related factor 2, but not SOD-2], as well as increase lipid peroxidation and protein ubiquitination, causing obvious oxidative damage and redox imbalance (76).

Muscles of C3KO induced by cardiotoxin have too many lobulated fibers belonging to the type of oxidative metabolism, increased connective tissue, insufficient muscle energy and no increase in mitochondrial content, PGC-1α and ATP synthase subunit δ transcripts, resulting in significant TGF-β transcription level increases with microRNA dysregulation, and the radial growth of muscle fibers is weakened, Akt/mTOR complex 1 signaling is disturbed, this signal is uncoupled from protein synthesis, and in C3KO myoblast cultures, myotube fusion is defective (77), so that healthy sarcomere cannot be reconstructed. This is the pathogenesis of abnormal muscle regeneration in patients with LGMD2A.

Although the symptoms of most patients with LGMD2A are usually uniform, studies have indicated that, compared with homozygous missense mutations, compound heterozygous mutations (such as pG222R/pR748Q) have a compensatory effect and that the presence of 'molecular complementation' may rescue a certain amount of the proteolytic activity of CAPN3, resulting in an exceptionally benign phenotype (32). Therefore, the severity and progression of the disease are dependent on different gene mutations.

LGMD2B

Mutations in dysferlin (DYSF) are responsible for LGMD2B. DYSF is absent or minimally expressed in the muscle tissues of patients (85). DYSF is thought to have a role in membrane repair. CAPN3 and recombinant desmoyokin (AHNAK; a protein involved in subsarcolemmal cytoarchitecture and membrane repair) coexist in the DYSF protein complex. In skeletal muscle cells with normal CAPN3 expression activity, the expression of AHNAK is decreased; conversely, in cells without CAPN3 expression, the expression of ANHAK is increased. Furthermore, cleaved fragments of AHNAK by CAPN3 lose their affinity for DYSF in skeletal muscles. Therefore, CAPN3 is a modulator of the DYSF protein complex in skeletal muscles (86). The expression of CAPN3 in the skeletal muscles of patients with LGMD2B is decreased. Further analysis has indicated missense mutations in CAPN3 that change the amino acids of CAPN3 into the amino acids present in CAPN1 and CAPN2 (87). Therefore, CAPN3 is associated with the onset of LGMD2B, but the specific mechanism exerted by CAPN3 in LGMD2B requires further exploration.

LGMD2J and tibial MD (TMD)

Titin C-terminal mutations in the M-band of striated muscles may cause LGMD2J and TMD (88). CAPN3 binds titin at the C-terminus and uses it as a substrate in vitro. There are several CAPN3 cleavage sites in the C-terminus of titin. Hydrolysis of titin at the C-terminus by CAPN3 may have an important role in normal muscles (89). Titin C-terminal mutations lead to the loss of binding site for CAPN3 and also to the lack of CAPN3 in muscle (89,90). Therefore, CAPN3 is involved in the pathogenesis of LGMD2J and TMD.

Duchenne MD (DMD)

DMD is a lethal X-linked muscle disease caused by defective expression of cytoskeletal protein dystrophin (Dp)427. Certain retinal neurons express Dp427 and/or the short subtype of dystrophin. Therefore, patients with DMD may also experience specific visual defects. A study that analyzed whether the lack of Dp427 affects the late development of retina in mdx mice (the most in-depth study of DMD animal models) indicated that, compared with that of age-matched wild-type mice, the expression of genes E18-P5 and P5 that encode proteins related to retinal development and synaptogenesis, including CAPN3, is transiently decreased in mdx mice (91).

Facioscapulohumeral MD (FSHD)

FSHD is a muscle disease related to the loss of heterozygous D4Z4 on chromosome 4q35. In previously reported atypical cases, DNA analysis of patients indicated that the loss of 4q35 is associated with heterozygous CAPN3 mutations (92,93). Overexpression of FSHD region gene 1 (FRG1) may disrupt muscle development and cause FSHD-like phenotypes. FSHD may also be related to splicing. FRG1 is related to RNA-binding fox-1 homolog 1 (Rbfox1) RNA and may reduce its stability. Rbfox1 is down-regulated in mice with high FRG1 expression and in patients with FSHD; on the contrary, CAPN3 subtypes lacking exon 6 (CAPN3 E6) were increased. Rbfox1 decreased and CAPN3 E6 overexpression inhibited muscle differentiation. Therefore, FSHD is caused by FRG1 overexpression, decreased Rbfox1 expression and high CAPN3 protein expression through misplaced splicing (94).

Ullrich congenital MD (UCMD)

UCMD is a common MD caused by abnormality of COL6A2 that leads to a defect in collagen VI. UCMD is characterized by unequal muscle fiber size and loss of muscle mass, as well as hyperplasia of connective tissue and adipose tissue. Studies have indicated that the expression of CAPN3 mRNA is decreased in patients with UCMD and that the downregulation of CAPN3 is related to altered nuclear immunolocalization of NF-κB. The weakening of CAPN3 and NF-κB signal transduction may cause muscle cell reduction and mass loss (95), but the exact mechanism remains to be elucidated.

Other diseases

Idiopathic eosinophilic myositis (IEM)

EM is frequently related to parasitic infections, systemic diseases, drugs or L-tryptophan intake. When these causes can be excluded, the pathology is IEM. A study has indicated that CAPN3 is a candidate gene associated with IEM, which has an autosomal recessive inheritance pattern. Idiopathic patients have the following characteristics: i) EM in the first decade; ii) elevated serum creatine phosphokinase levels (isolated or no corresponding weakness); and iii) increased peripheral blood eosinophils (96); its pathogenesis is related to mutation of CAPN3. Further studies that focus on the physiological functions of CAPN3 in skeletal muscles, particularly analyses of CAPN3 protein and gene in patients, are required to better understand IEM.

Inclusion body myositis (IBM)

IBM is the most commonly diagnosed primary myopathy in the elderly (97). Disorders of calcium homeostasis in cardiomyocytes may exacerbate factors that mediate IBM muscle degeneration. Immune-mediated membrane damage and/or abnormal accumulation of proteins may be the cause of calcium disorders in patients with IBM. Analysis of muscles in patients with IBM indicated that insufficient expression of CAPN3 mRNA and protein, which is conducive to proper calcium homeostasis and increased abundance of two CAPN3 substrates (97,98). The pathogenesis of IBM remains to be clarified and the role of CAPN3 in IBM remains to be explored.

Rhabdomyolysis syndrome

Rhabdomyolysis syndrome is a medical emergency caused by exposure to external triggers and may be related to increased genetic susceptibility. Previously, two patients have been diagnosed with rhabdomyolysis syndrome after consuming wild quail meat. Analysis has indicated that the expression of CAPN3 protein in these two patients was decreased and that there was no pathogenic mutation in the CAPN3 gene (99). Another study suggested that certain patients with underlying genetic diseases (such as recurrent episodes, a positive family history and high or persistently increased CK levels) have clear genetic defects and that CAPN3 may be related to increased genetic susceptibility to rhabdomyolysis syndrome (100).

Melanoma

Numerous genes involved in intracellular calcium and G protein signal transduction are highly expressed in melanoma, with CAPN3 being one of the most highly expressed genes (101).

In the process of induction of irreversible growth arrest and terminal differentiation, and subsequent apoptosis of melanoma cells, the expression of CAPN3 variant 6 is inhibited, but still maintained at a high level. After apoptotic injury, the high expression of CAPN3 has no critical role in the regulation of growth dynamics and/or cell viability. It has been suggested that the upregulation of CAPN3 may not be a pathogenic factor, but is related to the development of melanoma (102). Both hMp78 and hMp84 are established new splice variants of CAPN3. They are localized in the cytoplasm and in nucleoli. Compared with that in benign melanoma cells, the expression of these variants is downregulated in malignant melanoma cells. In A375 and HT-144 cells, hMp78 and hMp84 are over-expressed. In A375 cells, hMp84 exhibits catalytic activity that induces p53 stability, regulates the expression of certain genes related to p53 and oxidative stress and increases the production of cellular reactive oxygen species, which then leads to oxidative modification of phospholipids (F2-isoprostaglandin formation) and DNA damage, and ultimately decreased cell proliferation ability and cell death. In HT-144 cells, in addition to p53 accumulation, the effects of hMp84 are consistent with those observed in A375 cells. Therefore, it is thought that downregulation of CAPN3 may contribute to the progression of melanoma (103,104).

CAPN3 is also associated with the invasion of melanoma cells (105). Compared with that of M14C2/C4 cells with a low-invasive phenotype, the growth rate of highly invasive M14C2/MK18 cells is more rapid. In M14C2/MK18 cells, the expression of CAPN3 is downregulated. Inhibition of CAPN3 activity in M14C2/C4 cells significantly increases the invasiveness of M14C2/C4 cells, indicating that downregulation of CAPN3 promotes malignant melanoma invasion (106).

CAPN3 has a vital role in the development and metastasis of melanoma, but the underlying mechanism and whether the specific role of CAPN3 is related to tumor cell types require further clarification.

Epilepsy

There has been a case report of CAPN3 mutation in a pediatric case of LGMD with hereditary generalized epilepsy. It is thought that CAPN3 mutation is related to the occurrence of hereditary generalized epilepsy (107). Recently, members of a family were diagnosed with generalized epilepsy and LGMD phenotypes. It has been determined that patients with CAPN3 homozygous mutations developed LGMD, while subjects with CAPN3 heterozygous mutations developed epilepsy (108). Hence, CAPN3 mutations may have a role in hereditary generalized epilepsy.

Alzheimer's disease (AD)

AD is the most common type of dementia and its onset and development are related to specific changes in DNA methylation in affected brain regions (109,110). Patients with advanced AD frequently lose the ability to recognize family members. The fusiform gyrus (FUS) of the brain is important in facial recognition. Studies have indicated that the expression levels of CAPN3 and other four characteristic genes are abnormal in FUS and that there are related changes in the DNA methylome profiles of these genes (111). Compared with that of currently used clinical standards, the level of sensitivity of these related methylome profile changes is higher and may effectively predict the prognosis of AD.

Diabetes

Obesity is an important factor in the development of insulin resistance, which is the basis of type 2 diabetes. Studies have indicated that the expression levels of CAPN3 in skeletal muscle are positively correlated with carbohydrate oxidation but negatively correlated with circulating glucose and insulin concentrations, as well as body fat (112). Another study that performed fasting (inducing insulin resistance) and refeeding (reversing insulin) in healthy patients suggested that the expression of CAPN3 mRNA or protein is unaffected (113). Further studies are required to explore the association between CAPN3 and diabetes.

Coronary artery disease (CAD)

Lipid homeostasis is closely related to cardiovascular risk. Although hundreds of loci associated with blood lipids and related cardiovascular traits have been identified, there is only a small number of known genetic links that explore long-term changes in blood lipids. A genotyping analysis has revealed that there is a variant site (P=1.2x10-4) in CAPN3 that is related to CAD (114). The integration variation, haplotype and double ploidy of CAPN3 and FERM domain containing 5 genes are related to blood lipid variables (115). Therefore, CAPN3 is associated with blood lipids and related cardiovascular diseases.

Vitiligo

Vitiligo is a disease that features skin depigmentation. Its pathogenesis involves factors such as the environment, genetics and biology of melanocytes. RNA sequencing has identified CAPN3 as one of the five differentially expressed genes, with the RNA levels of CAPN3 being significantly increased (116). Further study of these differentially expressed genes is required to understand the pathogenesis and disease progression of vitiligo.

Age-related cataract

Age-related cataracts are related to degenerative changes that slowly occur in old individuals. In certain cases, vision is affected by lens opacity. Studies have suggested that 129α3Cx46-/- mice are able to form age-related cataracts, while in the absence of CAPN3, the formation of cataracts is delayed and the cataract appearance becomes more diffuse and of the pulverulent type. Analysis has indicated that CAPN3 is directly involved in the γ-crystallin cleavage pathway; CAPN3 is therefore associated with the formation of age-related cataracts in α3Cx46-/- mice (117). Since age-related cataract is the leading cause of blindness worldwide, it is important to better understand its pathogenesis.

6. Conclusions and future perspectives

CAPN3, a member of the calpain family, has certain common features of calpains, but due to its special structure, it has complex biological functions, including fast autolysis. To better understand CAPN3, it is necessary to study the quaternary structure, activity and natural substrates of CAPN3, particularly by using full-length CAPN3 purified protein.

Although certain functions of CAPN3 have been under-stood, due to its inherent instability, the molecular mechanisms of its substrate or CAPN3 activation remain elusive. In addition, iMOC may help regain the activity of the mutant CAPN3, which in turn helps to partially alleviate LGMD2A caused by missense mutations in the CAPN3 allele. Therefore, revealing the physiological significance of iMOC and the molecular mechanisms of CAPN3 is of great significance.

Existing CAPN3 and disease-related studies have been helpful in explaining the pathogenesis of associated diseases, which may facilitate the prediction of disease development and prognosis, but there is a relatively large number of studies on LGMD2A and only a small number of studies on other diseases; its role in numerous diseases remains controversial and may be further investigated. In terms of treatment, recombinant adeno-associated virus (rAAV) that mediates CAPN3 gene transfer and autologous induced pluripotent stem cells have been used to treat LGMD2A (118,119), both of which have certain curative effects, but with certain issues, including the potential immune response caused by the introduction of rAAV or CAPN3, or the persistence of genes. CAPN3-related diseases, particularly MD, are genetic-related. The combination of genetics and biochemical research will help to further clarify the pathogenic roles of this unusual calpain molecule in order to provide a basis to facilitate the development of precision gene and cell therapy in the future.

In addition, current studies on CAPN3 mainly focus on skeletal muscle. Although CAPN3 is a skeletal muscle-specific calpain, is not limited to skeletal muscle due to its diverse function and damage it causes in humans after mutation, which requires to be further explored.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- CAPN3

calpain 3

- NS

N-terminus

- IS1

insertion sequence 1

- MD

muscular dystrophy

- PC1

protease core domain 1

- PEF

penta-EF-hand (E, E-helix

- F

F-helix)

- CBSW

calpain-type β-sandwich

- PLEIAD

platform element for inhibition of autolytic degradation

- CTBP1

C-terminal binding protein 1

- CaM

calmodulin

- CBS-1

calcium binding site

- iMOC

intramolecular complementation

- AldoA

aldolase A

- RyR

ryanodine receptor

- NCX3

Na+-Ca2+ exchanger isoform 3

- FLNC

filamin C

- MLC1

myosin light chain 1

- PIAS

protein inhibitor of activated states

- LGMD2A

limb-girdle muscular dystrophy type 2A

- CaMKIIβ

calmodulin kinase IIβ

- C3KO

CAPN3 knockout mice

- NF-κB

nuclear factor κB

- GFAP

glial fibrillary acidic protein

- SVZ

sub-ventricular zone

- Ca-CaMKII

Ca2+/CaM-dependent protein kinase II

- PGC1α

peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ coactivator-1α

- CARP

cardiac myotonic repeat protein

- c-FLIP

cell FLICE inhibitor protein

- DYSF

dysferlin

- TMD

tibial MD

- DMD

Duchenne MD

- FSHD

facioscapulohumeral MD

- FRG1

FSHD region gene 1

- CAPN3 E6-

CAPN3 subtypes lacking exon 6

- UCMD

Ullrich congenital MD

- IEM

idiopathic eosinophilic myositis

- IBM

inclusion body myositis

- AD

Alzheimer's disease

- FUS

fusiform gyrus

- CAD

coronary artery disease

- AAV

adeno-associated virus

Funding Statement

The present study was supported by the National Key R&D Programme of China (grant nos. 2017YFA 0104201 and 2017YFA 0104200), the National Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 81330016, 82071353 and 82001593) and the Key R&D projects of Science and Technology Department of Sichuan Province (grant no. 2020YFS 0104).

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing is not applicable to this article, as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Authors' contributions

LC, FT, HG, XZ, XL and DX were involved in the conceptualization of the study. LC, FT, XL and DX were involved in software applications. LC, FT, HG, XZ, XL and DX provided the study resources. LC and FT were involved in the writing and preparation of the original draft, and in the writing, reviewing and editing of the study. HG and XZ were involved in the processing of the figures. XL and DX supervised the study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. Data authentication is not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Sorimachi H, Imajoh-Ohmi S, Emori Y, Kawasaki H, Ohno S, Minami Y, Suzuki K. Molecular cloning of a novel mammalian calcium-dependent protease distinct from both m- and mu-types. Specific expression of the mRNA in skeletal muscle. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:20106–20111. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(19)47225-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ono Y, Ojima K, Shinkai-Ouchi F, Hata S, Sorimachi H. An eccentric calpain, CAPN3/p94/calpain-3. Biochimie. 2016;122:169–187. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2015.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ohno S, Minoshima S, Kudoh J, Fukuyama R, Shimizu Y, Ohmi-Imajoh S, Shimizu N, Suzuki K. Four genes for the calpain family locate on four distinct human chromosomes. Cytogenet Cell Genet. 1990;53:225–229. doi: 10.1159/000132937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fougerousse F, Durand M, Suel L, Pourquié O, Delezoide AL, Romero NB, Abitbol M, Beckmann JS. Expression of genes (CAPN3, SGCA, SGCB, and TTN) involved in progressive muscular dystrophies during early human development. Genomics. 1998;48:145–156. doi: 10.1006/geno.1997.5160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fougerousse F, Anderson LV, Delezoide AL, Suel L, Durand M, Beckmann JS. Calpain3 expression during human cardiogenesis. Neuromuscul Disord. 2000;10:251–256. doi: 10.1016/S0960-8966(99)00107-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.König N, Raynaud F, Feane H, Durand M, Mestre-Francès N, Rossel M, Ouali A, Benyamin Y. Calpain 3 is expressed in astrocytes of rat and Microcebus brain. J Chem Neuroanat. 2003;25:129–136. doi: 10.1016/S0891-0618(02)00102-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marcilhac A, Raynaud F, Clerc I, Benyamin Y. Detection and localization of calpain 3-like protease in a neuronal cell line: Possible regulation of apoptotic cell death through degradation of nuclear IkappaBalpha. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2006;38:2128–2140. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2006.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McCartney CE, Ye Q, Campbell RL, Davies PL. Insertion sequence 1 from calpain-3 is functional in calpain-2 as an internal propeptide. J Biol Chem. 2018;293:17716–17730. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA118.004803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ye Q, Campbell RL, Davies PL. Structures of human calpain-3 protease core with and without bound inhibitor reveal mechanisms of calpain activation. J Biol Chem. 2018;293:4056–4070. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA117.001097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Imajoh S, Kawasaki H, Suzuki K. The COOH-terminal E-F hand structure of calcium-activated neutral protease (CANP) is important for the association of subunits and resulting proteolytic activity. J Biochem. 1987;101:447–452. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a121930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Partha SK, Ravulapalli R, Allingham JS, Campbell RL, Davies PL. Crystal structure of calpain-3 penta-EF-hand (PEF) domain-a homodimerized PEF family member with calcium bound at the fifth EF-hand. FEBS J. 2014;281:3138–3149. doi: 10.1111/febs.12849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hata S, Doi N, Shinkai-Ouchi F, Ono Y. A muscle-specific calpain, CAPN3, forms a homotrimer. Biochim Biophys Acta Proteins Proteom. 2020;1868:140411. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2020.140411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ma H, Fukiage C, Azuma M, Shearer TR. Cloning and expression of mRNA for calpain Lp82 from rat lens: Splice variant of p94. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1998;39:454–461. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ma H, Shih M, Fukiage C, Azuma M, Duncan MK, Reed NA, Richard I, Beckmann JS, Shearer TR. Influence of specific regions in Lp82 calpain on protein stability, activity, and localization within lens. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000;41:4232–4239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ma H, Shih M, Hata I, Fukiage C, Azuma M, Shearer TR. Lp85 calpain is an enzymatically active rodent-specific isozyme of lens Lp82. Curr Eye Res. 2000;20:183–189. doi: 10.1076/0271-3683(200003)2031-9FT183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Herasse M, Ono Y, Fougerousse F, Kimura E, Stockholm D, Beley C, Montarras D, Pinset C, Sorimachi H, Suzuki K, et al. Expression and functional characteristics of calpain 3 isoforms generated through tissue-specific transcriptional and posttranscriptional events. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:4047–4055. doi: 10.1128/MCB.19.6.4047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Azuma M, Fukiage C, Higashine M, Nakajima T, Ma H, Shearer TR. Identification and characterization of a retina-specific calpain (Rt88) from rat. Curr Eye Res. 2000;21:710–720. doi: 10.1076/0271-3683(200009)2131-RFT710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nakajima T, Fukiage C, Azuma M, Ma H, Shearer TR. Different expression patterns for ubiquitous calpains and Capn3 splice variants in monkey ocular tissues. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2001;1519:55–64. doi: 10.1016/S0167-4781(01)00212-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ono Y, Iemura S, Novak SM, Doi N, Kitamura F, Natsume T, Gregorio CC, Sorimachi H. PLEIAD/SIMC1/C5orf25, a novel autolysis regulator for a skeletal-muscle-specific calpain, CAPN3, scaffolds a CAPN3 substrate, CTBP1. J Mol Biol. 2013;425:2955–2972. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2013.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ermolova N, Kramerova I, Spencer MJ. Autolytic activation of calpain 3 proteinase is facilitated by calmodulin protein. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:996–1004. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.588780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ono Y, Sorimachi H. Calpains: An elaborate proteolytic system. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1824:224–236. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2011.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sorimachi H, Kawabata Y. Calpain and pathology in view of structure-function relationships. Nihon Yakurigaku Zasshi. 2003;122:21–29. doi: 10.1254/fpj.122.21. In Japanese. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sorimachi H, Toyama-Sorimachi N, Saido TC, Kawasaki H, Sugita H, Miyasaka M, Arahata K, Ishiura S, Suzuki K. Muscle-specific calpain, p94, is degraded by autolysis immediately after translation, resulting in disappearance from muscle. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:10593–10605. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(18)82240-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rey MA, Davies PL. The protease core of the muscle-specific calpain, p94, undergoes Ca2+-dependent intramolecular autolysis. FEBS Lett. 2002;532:401–406. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(02)03722-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Diaz BG, Moldoveanu T, Kuiper MJ, Campbell RL, Davies PL. Insertion sequence 1 of muscle-specific calpain, p94, acts as an internal propeptide. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:27656–27666. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313290200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fukiage C, Nakajima E, Ma H, Azuma M, Shearer TR. Characterization and regulation of lens-specific calpain Lp82. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:20678–20685. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200697200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ono Y, Torii F, Ojima K, Doi N, Yoshioka K, Kawabata Y, Labeit D, Labeit S, Suzuki K, Abe K, et al. Suppressed disassembly of autolyzing p94/CAPN3 by N2A connectin/titin in a genetic reporter system. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:18519–18531. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601029200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ono Y, Hayashi C, Doi N, Tagami M, Sorimachi H. The importance of conserved amino acid residues in p94 protease sub-domain IIb and the IS2 region for constitutive autolysis. FEBS Lett. 2008;582:691–698. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.01.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hata S, Doi N, Kitamura F, Sorimachi H. Stomach-specific calpain, nCL-2/calpain 8, is active without calpain regulatory subunit and oligomerizes through C2-like domains. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:27847–27856. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703168200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Parr T, Sensky PL, Scothern GP, Bardsley RG, Buttery PJ, Wood JD, Warkup C. Relationship between skeletal muscle-specific calpain and tenderness of conditioned porcine longissimus muscle. J Anim Sci. 1999;77:661–668. doi: 10.2527/1999.773661x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ono Y, Shindo M, Doi N, Kitamura F, Gregorio CC, Sorimachi H. The N- and C-terminal autolytic fragments of CAPN3/p94/calpain-3 restore proteolytic activity by inter- molecular complementation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:E5527–E5536. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1411959111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sáenz A, Ono Y, Sorimachi H, Goicoechea M, Leturcq F, Blázquez L, García-Bragado F, Marina A, Poza JJ, Azpitarte M, et al. Does the severity of the LGMD2A phenotype in compound heterozygotes depend on the combination of mutations? Muscle Nerve. 2011;44:710–714. doi: 10.1002/mus.22194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ojima K, Ono Y, Hata S, Koyama S, Doi N, Sorimachi H. Possible functions of p94 in connectin-mediated signaling pathways in skeletal muscle cells. J Muscle Res Cell Motil. 2005;26:409–417. doi: 10.1007/s10974-005-9023-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kramerova I, Torres JA, Eskin A, Nelson SF, Spencer MJ. Calpain 3 and CaMKIIβ signaling are required to induce HSP70 necessary for adaptive muscle growth after atrophy. Hum Mol Genet. 2018;27:1642–1653. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddy071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Murphy RM, Vissing K, Latchman H, Lamboley C, McKenna MJ, Overgaard K, Lamb GD. Activation of skeletal muscle calpain-3 by eccentric exercise in humans does not result in its translocation to the nucleus or cytosol. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2011;111:1448–1458. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00441.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Baghdiguian S, Martin M, Richard I, Pons F, Astier C, Bourg N, Hay RT, Chemaly R, Halaby G, Loiselet J, et al. Calpain 3 deficiency is associated with myonuclear apoptosis and profound perturbation of the IkappaB alpha/NF-kappaB pathway in limb-girdle muscular dystrophy type 2A. Nat Med. 1999;5:503. doi: 10.1038/8385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sorimachi H, Kinbara K, Kimura S, Takahashi M, Ishiura S, Sasagawa N, Sorimachi N, Shimada H, Tagawa K, Maruyama K, et al. Muscle-specific calpain, p94, responsible for limb girdle muscular dystrophy type 2A, associates with connectin through IS2, a p94-specific sequence. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:31158–31162. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.52.31158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Taveau M, Bourg N, Sillon G, Roudaut C, Bartoli M, Richard I. Calpain 3 is activated through autolysis within the active site and lyses sarcomeric and sarcolemmal components. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:9127–9135. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.24.9127-9135.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kramerova I, Kudryashova E, Wu B, Ottenheijm C, Granzier H, Spencer MJ. Novel role of calpain-3 in the triad-associated protein complex regulating calcium release in skeletal muscle. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17:3271–3280. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kramerova I, Ermolova N, Eskin A, Hevener A, Quehenberger O, Armando AM, Haller R, Romain N, Nelson SF, Spencer MJ. Failure to up-regulate transcription of genes necessary for muscle adaptation underlies limb girdle muscular dystrophy 2A (calpainopathy) Hum Mol Genet. 2016;25:2194–2207. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddw086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Michel LY, Hoenderop JG, Bindels RJ. Calpain-3-mediated regulation of the Na+-Ca2+ exchanger isoform 3. Pflugers Arch. 2016;468:243–255. doi: 10.1007/s00424-015-1747-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Beckmann JS, Spencer M. Calpain 3, the 'gatekeeper' of proper sarcomere assembly, turnover and maintenance. Neuromuscul Disord. 2008;18:913–921. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2008.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.de Andrade Rosa I, Corrêa S, Costa ML, Mermelstein C. The scaffolding protein calpain-3 has multiple distributions in embryonic chick muscle cells and it is essential for the formation of muscle fibers. Tissue Cell. 2020;67:101436. doi: 10.1016/j.tice.2020.101436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Guyon JR, Kudryashova E, Potts A, Dalkilic I, Brosius MA, Thompson TG, Beckmann JS, Kunkel LM, Spencer MJ. Calpain 3 cleaves filamin C and regulates its ability to interact with gamma- and delta-sarcoglycans. Muscle Nerve. 2003;28:472–483. doi: 10.1002/mus.10465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kramerova I, Kudryashova E, Wu B, Spencer MJ. Regulation of the M-cadherin-beta-catenin complex by calpain 3 during terminal stages of myogenic differentiation. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:8437–8447. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01296-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stuelsatz P, Pouzoulet F, Lamarre Y, Dargelos E, Poussard S, Leibovitch S, Cottin P, Veschambre P. Down-regulation of MyoD by calpain 3 promotes generation of reserve cells in C2C12 myoblasts. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:12670–12683. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.063966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stockholm D, Herasse M, Marchand S, Praud C, Roudaut C, Richard I, Sebille A, Beckmann JS. Calpain 3 mRNA expression in mice after denervation and during muscle regeneration. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2001;280:C1561–C1569. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2001.280.6.C1561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wu R, Yan Y, Yao J, Liu Y, Zhao J, Liu M. Calpain 3 expression pattern during gastrocnemius muscle atrophy and regeneration following sciatic nerve injury in rats. Int J Mol Sci. 2015;16:26927–26935. doi: 10.3390/ijms161126003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cohen N, Kudryashova E, Kramerova I, Anderson LV, Beckmann JS, Bushby K, Spencer MJ. Identification of putative in vivo substrates of calpain 3 by comparative proteomics of overexpressing transgenic and nontransgenic mice. Proteomics. 2006;6:6075–6084. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200600199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.de Morrée A, Lutje Hulsik D, Impagliazzo A, van Haagen HH, de Galan P, van Remoortere A, 't Hoen PA, van Ommen GB, Frants RR, van der Maarel SM. Calpain 3 is a rapid-action, unidirectional proteolytic switch central to muscle remodeling. PLoS One. 2010;5:e11940. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kramerova I, Kudryashova E, Venkatraman G, Spencer MJ. Calpain 3 participates in sarcomere remodeling by acting upstream of the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:2125–2134. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hauerslev S, Sveen ML, Duno M, Angelini C, Vissing J, Krag TO. Calpain 3 is important for muscle regeneration: Evidence from patients with limb girdle muscular dystrophies. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2012;13:43. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-13-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Richard I, Roudaut C, Marchand S, Baghdiguian S, Herasse M, Stockholm D, Ono Y, Suel L, Bourg N, Sorimachi H, et al. Loss of calpain 3 proteolytic activity leads to muscular dystrophy and to apoptosis-associated IkappaBalpha/nuclear factor kappaB pathway perturbation in mice. J Cell Biol. 2000;151:1583–1590. doi: 10.1083/jcb.151.7.1583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.DeArmond S, Fajardo M, Naughton S, Eng L. Degradation of glial fibrillary acidic protein by a calcium dependent proteinase: An electroblot study. Brain Res. 1983;262:275–282. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(83)91018-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lepekhin EA, Eliasson C, Berthold CH, Berezin V, Bock E, Pekny M. Intermediate filaments regulate astrocyte motility. J Neurochem. 2001;79:617–625. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00595.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Alvarez-Buylla A, Seri B, Doetsch F. Identification of neural stem cells in the adult vertebrate brain. Brain Res Bull. 2002;57:751–758. doi: 10.1016/S0361-9230(01)00770-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schmidt WM, Uddin MH, Dysek S, Moser-Their K, Pirker C, Höger H, Ambros IM, Ambros PF, Berger W, Bittner RE. DNA damage, somatic aneuploidy, and malignant sarcoma susceptibility in muscular dystrophies. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1002042. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Oliveira Santos M, Ninitas P, Conceição I. Severe limb-girdle muscular dystrophy 2A in two young siblings from Guinea-Bissau associated with a novel null homozygous mutation in CAPN3 gene. Neuromuscul Disord. 2018;28:1003–1005. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2018.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ono Y, Sorimachi H, Suzuki K. New aspect of the research on limb-girdle muscular dystrophy 2A: A molecular biologic and biochemical approach to pathology. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 1999;9:114–118. doi: 10.1016/S1050-1738(99)00018-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Richard I, Roudaut C, Saenz A, Pogue R, Grimbergen JE, Anderson LV, Beley C, Cobo AM, de Diego C, Eymard B, et al. Calpainopathy-a survey of mutations and polymorphisms. Am J Hum Genet. 1999;64:1524–1540. doi: 10.1086/302426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chae J, Minami N, Jin Y, Nakagawa M, Murayama K, Igarashi F, Nonaka I. Calpain 3 gene mutations: Genetic and clinico-pathologic findings in limb-girdle muscular dystrophy. Neuromuscul Disord. 2001;11:547–555. doi: 10.1016/S0960-8966(01)00197-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Fanin M, Nascimbeni AC, Fulizio L, Trevisan CP, Meznaric-Petrusa M, Angelini C. Loss of calpain-3 auto- catalytic activity in LGMD2A patients with normal protein expression. Am J Pathol. 2003;163:1929–1936. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63551-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Peddareddygari LR, Surgan V, Grewal RP. Limb-girdle muscular dystrophy type 2A resulting from homozygous G2338C transversion mutation in the calpain-3 gene. J Clin Neuromuscul Dis. 2010;12:62–65. doi: 10.1097/CND.0b013e3181f3dbd3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Perez F, Vital A, Martin-Negrier ML, Ferrer X, Sole G. Diagnostic procedure of limb girdle muscular dystrophies 2A or calpainopathies: French cohort from a neuromuscular center (Bordeaux) Rev Neurol (Paris) 2010;166:502–508. doi: 10.1016/j.neurol.2009.10.015. In French. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Fanin M, Fulizio L, Nascimbeni AC, Spinazzi M, Piluso G, Ventriglia VM, Ruzza G, Siciliano G, Trevisan CP, Politano L, et al. Molecular diagnosis in LGMD2A: Mutation analysis or protein testing? Hum Mutat. 2004;24:52–62. doi: 10.1002/humu.20058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Fanin M, Nascimbeni AC, Angelini C. Screening of calpain-3 autolytic activity in LGMD muscle: A functional map of CAPN3 gene mutations. J Med Genet. 2007;44:38–43. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2006.044859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pathak P, Sharma MC, Sarkar C, Jha P, Suri V, Mohd H, Singh S, Bhatia R, Gulati S. Limb girdle muscular dystrophy type 2A in India: A study based on semi-quantitative protein analysis, with clinical and histopathological correlation. Neurol India. 2010;58:549–554. doi: 10.4103/0028-3886.68675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chrobáková T, Hermanová M, Kroupová I, Vondrácek P, Maríková T, Mazanec R, Zámecník J, Stanek J, Havlová M, Fajkusová L. Mutations in Czech LGMD2A patients revealed by analysis of calpain3 mRNA and their phenotypic outcome. Neuromuscul Disord. 2004;14:659–665. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2004.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ermolova N, Kudryashova E, DiFranco M, Vergara J, Kramerova I, Spencer MJ. Pathogenity of some limb girdle muscular dystrophy mutations can result from reduced anchorage to myofibrils and altered stability of calpain 3. Hum Mol Genet. 2011;20:3331–3345. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Duguez S, Bartoli M, Richard I. Calpain 3: A key regulator of the sarcomere? FEBS J. 2006;273:3427–3436. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2006.05351.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Groen EJ, Charlton R, Barresi R, Anderson LV, Eagle M, Hudson J, Koref MS, Straub V, Bushby KM. Analysis of the UK diagnostic strategy for limb girdle muscular dystrophy 2A. Brain. 2007;130:3237–3249. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Chiannilkulchai N, Pasturaud P, Richard I, Auffray C, Beckmann JS. A primary expression map of the chromosome 15q15 region containing the recessive form of limb-girdle muscular dystrophy (LGMD2A) gene. Hum Mol Genet. 1995;4:717–725. doi: 10.1093/hmg/4.4.717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ojima K, Kawabata Y, Nakao H, Nakao K, Doi N, Kitamura F, Ono Y, Hata S, Suzuki H, Kawahara H, et al. Dynamic distribution of muscle-specific calpain in mice has a key role in physical-stress adaptation and is impaired in muscular dystrophy. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:2672–2683. doi: 10.1172/JCI40658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Baghdiguian S, Richard I, Martin M, Coopman P, Beckmann JS, Mangeat P, Lefranc G. Pathophysiology of limb girdle muscular dystrophy type 2A: Hypothesis and new insights into the IkappaBalpha/NF-kappaB survival pathway in skeletal muscle. J Mol Med (Berl) 2001;79:254–261. doi: 10.1007/s001090100225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Benayoun B, Baghdiguian S, Lajmanovich A, Bartoli M, Daniele N, Gicquel E, Bourg N, Raynaud F, Pasquier MA, Suel L, et al. NF-kappaB-dependent expression of the anti- apoptotic factor c-FLIP is regulated by calpain 3, the protein involved in limb-girdle muscular dystrophy type 2A. FASEB J. 2008;22:1521–1529. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-8701com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Nilsson MI, Macneil LG, Kitaoka Y, Alqarni F, Suri R, Akhtar M, Haikalis ME, Dhaliwal P, Saeed M, Tarnopolsky MA. Redox state and mitochondrial respiratory chain function in skeletal muscle of LGMD2A patients. PLoS One. 2014;9:e102549. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0102549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Yalvac ME, Amornvit J, Braganza C, Chen L, Hussain SA, Shontz KM, Montgomery CL, Flanigan KM, Lewis S, Sahenk Z. Impaired regeneration in calpain-3 null muscle is associated with perturbations in mTORC1 signaling and defective mitochondrial biogenesis. Skelet Muscle. 2017;7:27. doi: 10.1186/s13395-017-0146-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Gallardo E, Saenz A, Illa I. Limb-girdle muscular dystrophy 2A. Handb Clin Neurol. 2011;101:97–110. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-08-045031-5.00006-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Toral-Ojeda I, Aldanondo G, Lasa-Elga r resta J, Lasa-Fernández H, Fernández-Torrón R, López de Munain A, Vallejo-Illarramendi A. Calpain 3 deficiency affects SERCA expression and function in the skeletal muscle. Expert Rev Mol Med. 2016;18:e7. doi: 10.1017/erm.2016.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lasa-Elgarresta J, Mosqueira-Martín L, Naldaiz-Gastesi N, Sáenz A, López de Munain A, Vallejo-Illarramendi A. Calcium mechanisms in limb-girdle muscular dystrophy with CAPN3 mutations. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:4548. doi: 10.3390/ijms20184548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.DiFranco M, Kramerova I, Vergara JL, Spencer MJ. Attenuated Ca(2+) release in a mouse model of limb girdle muscular dystrophy 2A. Skelet Muscle. 2016;6:11. doi: 10.1186/s13395-016-0081-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kramerova I, Kudryashova E, Ermolova N, Saenz A, Jaka O, López de Munain A, Spencer MJ. Impaired calcium calmodulin kinase signaling and muscle adaptation response in the absence of calpain 3. Hum Mol Genet. 2012;21:3193–3204. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Liu J, Campagna J, John V, Damoiseaux R, Mokhonova E, Becerra D, Meng H, McNally EM, Pyle AD, Kramerova I, Spencer MJ. A small-molecule approach to restore A slow-oxidative phenotype and defective CaMKIIβ signaling in limb girdle muscular dystrophy. Cell Rep Med. 2020;1:100122. doi: 10.1016/j.xcrm.2020.100122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Laure L, Danièle N, Suel L, Marchand S, Aubert S, Bourg N, Roudaut C, Duguez S, Bartoli M, Richard I. A new pathway encompassing calpain 3 and its newly identified substrate cardiac ankyrin repeat protein is involved in the regulation of the nuclear factor-κB pathway in skeletal muscle. FEBS J. 2010;277:4322–4337. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2010.07820.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Fanin M, Pegoraro E, Matsuda-Asada C, Brown RH, Jr, Angelini C. Calpain-3 and dysferlin protein screening in patients with limb-girdle dystrophy and myopathy. Neurology. 2001;56:660–665. doi: 10.1212/WNL.56.5.660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Huang Y, de Morrée A, van Remoortere A, Bushby K, Frants RR, den Dunnen JT, van der Maarel SM. Calpain 3 is a modulator of the dysferlin protein complex in skeletal muscle. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17:1855–1866. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Anderson LV, Harrison RM, Pogue R, Vafiadaki E, Pollitt C, Davison K, Moss JA, Keers S, Pyle A, Shaw PJ, et al. Secondary reduction in calpain 3 expression in patients with limb girdle muscular dystrophy type 2B and Miyoshi myopathy (primary dysferlinopathies) Neuromuscul Disord. 2000;10:553–559. doi: 10.1016/S0960-8966(00)00143-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Haravuori H, Vihola A, Straub V, Auranen M, Richard I, Marchand S, Voit T, Labeit S, Somer H, Peltonen L, et al. Secondary calpain3 deficiency in 2q-linked muscular dystrophy: Titin is the candidate gene. Neurology. 2001;56:869–877. doi: 10.1212/WNL.56.7.869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Charton K, Sarparanta J, Vihola A, Milic A, Jonson PH, Suel L, Luque H, Boumela I, Richard I, Udd B. CAPN3-mediated processing of C-terminal titin replaced by pathological cleavage in titinopathy. Hum Mol Genet. 2015;24:3718–3731. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddv116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Charton K, Danièle N, Vihola A, Roudaut C, Gicquel E, Monjaret F, Tarrade A, Sarparanta J, Udd B, Richard I. Removal of the calpain 3 protease reverses the myopathology in a mouse model for titinopathies. Hum Mol Genet. 2010;19:4608–4624. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Persiconi I, Cosmi F, Guadagno NA, Lupo G, De Stefano ME. Dystrophin is required for the proper timing in retinal histogenesis: A thorough investigation on the mdx mouse model of duchenne muscular dystrophy. Front Neurosci. 2020;14:760. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2020.00760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Pastorello E, Cao M, Trevisan CP. Atypical onset in a series of 122 cases with facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2012;114:230–234. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2011.10.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Sacconi S, Camaño P, de Greef JC, Lemmers RJ, Salviati L, Boileau P, Lopez de Munain Arregui A, van der Maarel SM, Desnuelle C. Patients with a phenotype consistent with facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy display genetic and epigenetic heterogeneity. J Med Genet. 2012;49:41–46. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2011-100101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Pistoni M, Shiue L, Cline MS, Bortolanza S, Neguembor MV, Xynos A, Ares M, Jr, Gabellini D. Rbfox1 downregulation and altered calpain 3 splicing by FRG1 in a mouse model of Facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy (FSHD) PLoS Genet. 2013;9:e1003186. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Paco S, Ferrer I, Jou C, Cusí V, Corbera J, Torner F, Gualandi F, Sabatelli P, Orozco A, Gómez-Foix AM, et al. Muscle fiber atrophy and regeneration coexist in collagen VI-deficient human muscle: Role of calpain-3 and nuclear factor-κB signaling. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2012;71:894–906. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e31826c6f7b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Krahn M, Lopez de Munain A, Streichenberger N, Bernard R, Pécheux C, Testard H, Pena-Segura JL, Yoldi E, Cabello A, Romero NB, et al. CAPN3 mutations in patients with idiopathic eosinophilic myositis. Ann Neurol. 2006;59:905–911. doi: 10.1002/ana.20833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Parker KC, Kong SW, Walsh RJ, Bch Salajegheh M, Moghadaszadeh B, Amato AA, Nazareno R, Lin YY, Krastins B. et al. Fast-twitch sarcomeric and glycolytic enzyme protein loss in inclusion body myositis. Muscle Nerve. 2009;39:739–753. doi: 10.1002/mus.21230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Amici DR, Pinal-Fernandez I, Mázala DA, Lloyd TE, Corse AM, Christopher-Stine L, Mammen AL, Chin ER. Calcium dysregulation, functional calpainopathy, and endoplasmic reticulum stress in sporadic inclusion body myositis. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2017;5:24. doi: 10.1186/s40478-017-0427-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Musumeci O, Aguennouz M, Cagliani R, Comi GP, Ciranni A, Rodolico C, Messina C, Vita G, Toscano A. Calpain 3 deficiency in Quail Eater's disease. Ann Neurol. 2004;55:146–147. doi: 10.1002/ana.10821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Kruijt N, van den Bersselaar LR, Kamsteeg EJ, Verbeeck W, Snoeck MMJ, Everaerd DS, Abdo WF, Jansen DRM, Erasmus CE, Jungbluth H, Voermans NC. The etiology of rhabdomyolysis: An interaction between genetic susceptibility and external triggers. Eur J Neurol. 2021;28:647–659. doi: 10.1111/ene.14553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Weeraratna AT, Becker D, Carr KM, Duray PH, Rosenblatt KP, Yang S, Chen Y, Bittner M, Strausberg RL, Riggins GJ, et al. Generation and analysis of melanoma SAGE libraries: SAGE advice on the melanoma transcriptome. Oncogene. 2004;23:2264–2274. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Huynh KM, Kim G, Kim DJ, Yang SJ, Park SM, Yeom YI, Fisher PB, Kang D. Gene expression analysis of terminal differentiation of human melanoma cells highlights global reductions in cell cycle-associated genes. Gene. 2009;433:32–39. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2008.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Moretti D, Del Bello B, Cosci E, Biagioli M, Miracco C, Maellaro E. Novel variants of muscle calpain 3 identified in human melanoma cells: Cisplatin-induced changes in vitro and differential expression in melanocytic lesions. Carcinogenesis. 2009;30:960–967. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgp098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Moretti D, Del Bello B, Allavena G, Corti A, Signorini C, Maellaro E. Calpain-3 impairs cell proliferation and stimulates oxidative stress-mediated cell death in melanoma cells. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0117258. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0117258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Rambow F, Job B, Petit V, Gesbert F, Delmas V, Seberg H, Meurice G, Van Otterloo E, Dessen P, Robert C, et al. New functional signatures for understanding melanoma biology from tumor cell lineage-specific analysis. Cell Rep. 2015;13:840–853. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.09.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Ruffini F, Tentori L, Dorio AS, Arcelli D, D'Amati G, D'Atri S, Graziani G, Lacal PM. Platelet-derived growth factor C and calpain-3 are modulators of human melanoma cell invasiveness. Oncol Rep. 2013;30:2887–2896. doi: 10.3892/or.2013.2791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Pizzanelli C, Mancuso M, Galli R, Choub A, Fanin M, Nascimbeni AC, Siciliano G, Murri L. Epilepsy and limb girdle muscular dystrophy type 2A: Double trouble, serendipitous finding or new phenotype? Neurol Sci. 2006;27:134–136. doi: 10.1007/s10072-006-0615-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Viloria-Alebesque A, Bellosta-Diago E, Santos-Lasaosa S, Mauri-Llerda JÁ. Familial association of genetic generalised epilepsy with limb-girdle muscular dystrophy through a mutation in CAPN3. Epilepsy Behav Case Rep. 2019;11:122–124. doi: 10.1016/j.ebcr.2019.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Sanchez-Mut JV, Aso E, Panayotis N, Lott I, Dierssen M, Rabano A, Urdinguio RG, Fernandez AF, Astudillo A, Martin-Subero JI, et al. DNA methylation map of mouse and human brain identifies target genes in Alzheimer's disease. Brain. 2013;136:3018–3027. doi: 10.1093/brain/awt237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.De Jager P, Srivastava G, Lunnon K, Burgess J, Schalkwyk LC, Yu L, Eaton ML, Keenan BT, Ernst J, McCabe C, et al. Alzheimer's disease: Early alterations in brain DNA methylation at ANK1, BIN1, RHBDF2 and other loci. Nat Neurosci. 2014;17:1156–1163. doi: 10.1038/nn.3786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Ma D, Fetahu IS, Wang M, Fang R, Li J, Liu H, Gramyk T, Iwanicki I, Gu S, Xu W, et al. The fusiform gyrus exhibits an epigenetic signature for Alzheimer's disease. Clin Epigenetics. 2020;12:129. doi: 10.1186/s13148-020-00916-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Walder K, McMillan J, Lapsys N, Kriketos A, Trevaskis J, Civitarese A, Southon A, Zimmet P, Collier G. Calpain 3 gene expression in skeletal muscle is associated with body fat content and measures of insulin resistance. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2002;26:442–449. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Norton L, Parr T, Bardsley RG, Ye H, Tsintzas K. Characterization of GLUT4 and calpain expression in healthy human skeletal muscle during fasting and refeeding. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 2007;189:233–240. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.2006.01639.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Varga TV, Kurbasic A, Aine M, Eriksson P, Ali A, Hindy G, Gustafsson S, Luan J, Shungin D, Chen Y, et al. Novel genetic loci associated with long-term deterioration in blood lipid concentrations and coronary artery disease in European adults. Int J Epidemiol. 2017;46:1211–1222. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyw245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]