Abstract

Evidence about the health problems associated with sugary drink consumption is well-established. However, little is known about which sugary drink health harms are most effective at changing consumers’ behavior. We aimed to identify which harms people were aware of and most discouraged them from wanting to buy sugary drinks. Participants were a national convenience sample of diverse parents (n=1,058), oversampled for Latino parents (48%). Participants rated a list of sugary drink-related health harms occurring in children (7 harms) and in adults (15 harms). Outcomes were awareness of each harm and how much each harm discouraged parents from wanting to purchase sugary drinks. Most participants were aware that sugary drinks contribute to tooth decay in children (75%) and weight gain in both children (73%) and adults (73%). Few participants were aware that sugary drinks contribute to adult infertility (16%), arthritis (18%), and gout (17%). All health harms were rated highly in terms of discouraging parents from wanting to buy sugary drinks (range: 3.59–4.11 on a 1–5 scale), with obesity, pre-diabetes, and tooth decay eliciting the highest discouragement ratings. Harm-induced discouragement was higher for participants who were aware of more health harms (B=0.06, p<0.0001), identified as male (B=0.17 compared to female, p=0.01), or had an annual household income of $50,000 or more (B=0.16 compared to less than $50,000, p=0.03). These findings suggest health messages focused on a variety of health harms could raise awareness and discourage sugary drink purchases.

Keywords: sugar sweetened beverages, sugary drinks, sugary drink warning labels

1. Introduction

Children and adults in the U.S. consume well above recommended levels of sugary drinks (i.e., drinks with added sugar such as sodas, sports drinks, and fruit-flavored drinks), which has been shown to be a major determinant of obesity.1–4 Sugary drink consumption has also been linked to type II diabetes,4 sleep disturbances,5 tooth decay,6 and heart disease.7 Health communications, including warning labels and mass media campaigns, are promising strategies for informing the public about the risks of sugary drinks and discouraging purchasing and consumption. For example, a recent meta-analysis of experimental studies found that sugary drink warnings elicited more thinking about negative health effects of sugary drinks, lower perceived healthfulness of sugary drinks, and lower purchasing of sugary drinks.8 However, this meta-analysis pooled across multiple types of warnings, including those that discussed dental caries, obesity, and multiple health harms. It remains unknown which of these health harms are most effective for use in warnings. Mass media campaigns also have the potential to increase awareness of the harms of sugary drinks and reduce purchasing.9 Most sugary drink reduction campaigns focus on obesity10 or type II diabetes;11 little is known about whether inclusion of other health harms from sugary beverages could strengthen campaign effectiveness. Moreover, little is known about whether creating messages about harms occurring in children versus adults would be more effective.

Also unknown is whether awareness of and reactions to the health harms from sugary drink consumption vary by specific sub-populations. Epidemiological data indicates that Black and Latino populations have higher sugary drink intake than White populations,12 contributing to preventable inequities in chronic diseases.13–16 Thus, it is crucial to understand whether reactions to the harms differ among key population subgroups to ensure that public health messaging could reach populations with higher rates of sugary drink consumption.

1.1. Objectives

In this exploratory study, we sought to identify which harms parents were aware of and which most discouraged them from purchasing sugary drinks. We focused on parents because they tend to be the primary purchasers of beverages for both themselves and for their children. This study assessed awareness because information campaigns often seek to increase knowledge of sugary drink harms, and because increasing awareness could help discourage sugary drink purchases. We additionally examined perceived discouragement from purchasing sugary drinks because it has been found to be predictive of actual behavior change.17 Additionally, to provide insight into the potential for sugary drink health messages to affect health disparities, we also sought to examine demographic predictors (e.g., race, ethnicity, and gender) of the extent to which participants reported the health harms discouraged them from purchasing sugary drinks. Finally, we aimed to compare reactions to health harms that occur in children to those that occur in adults.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Sample

In October 2019, we recruited a convenience sample of 1,078 U.S. adults, as part of a larger study that aimed to examine image-based vs. text nutrient and health warnings among Latinos and non-Latinos. Recruitment occurred through CloudResearch Prime Panels, a platform with access to over 20 million participants for behavioral research. Inclusion criteria were currently residing in the U.S., being at least 18 years old, and having at least one child between the ages of 2 and 12. Prime Panels used purposive sampling to recruit about half Latino and half non-Latino parents, in line with the objectives of the larger study. Latino ethnicity was measured by asking participants if they were “of Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish origin.”

After providing informed consent, participants completed an online survey, programmed using Qualtrics survey software. Participants completed three experimental tasks (one about the above-described sugary drink warnings, one about fruit drink marketing, and one about water and soda-related messaging; these experiments will be reported in forthcoming papers) and then answered questions related to the current paper. Participants received incentives in cash, gift cards or reward points from Prime Panels after completing the survey. The University of North Carolina Institutional Review Board approved this study.

2.2. Measures

The survey assessed awareness of and discouragement in response to different health harms of sugary drinks. Sugary drinks were defined in the survey as “packaged drinks (ready-to-drink or powdered) that are sweetened. This includes regular sodas, fruit-flavored drinks, sports drinks, sweetened teas and coffees, horchata, agua de Jamaica, chocolate milk, and energy drinks. This does NOT include homemade drinks like agua fresca, coffee, tea, or freshly made fruit juice. This also does NOT include diet or low-calorie drinks.” Awareness that sugary drinks contribute to health harms was assessed using two select-all-that-apply questions, adapted from previous studies.18,19 The first question asked about awareness of harms occurring in children with the following question: “Before today, had you ever heard that drinking beverages with added sugar can contribute to the following health harms in children?” The answer choices included seven harms, displayed in random order. The second question asked about awareness of sugary drink-related harms occurring in adults with the following question: “Before today, had you ever heard that drinking beverages with added sugar can contribute to the following health harms in adults?” with 15 different harms also displayed in random order. For both questions, participants had the option to select “I haven’t heard of any of these health harms before”; this option always appeared last. The study team selected harms based on a review of the recent epidemiologic evidence of health implications of consuming sugary drinks. To be included, harms must have been supported by either a systematic review, meta-analysis, or a prospective longitudinal study. The harms occurring in children were pre-diabetes,20 obesity,20 weight gain,20,21 sleep problems,20 headaches,20 anxiety and stress,20 and tooth decay.20,22 The harms occurring in adults were type II diabetes,4,23,24 obesity,25,26 weight gain,21,24 obesity which increases risk of some cancers,21,27 sleep problems (such as poor sleep quality, tiredness/fatigue, and late bedtime),28 nonalcoholic fatty liver disease,29 tooth decay,6 heart disease,30,31 high blood pressure,24,30,31 arthritis,32 gout,33,34 early death,35,36 and infertility.37

Participants also rated the extent to which knowing about each health harm discouraged them from wanting to purchase sugary drinks, using a measure adapted from previous studies.19,38 The question about harms occurring in children asked, “How much does knowing that beverages with added sugar contributes to these health harms in children discourage you from wanting to purchase these beverages?” The health harms were formatted as a matrix in a random order, with answer choices on a 5-point Likert type scale that ranged from “not at all” (coded as 1) to “very much” (coded as 5). The same question was asked about harms occurring in adults with the same response scale.

Participants also answered standard demographic questions including race, age, and income level. Participants had the option to take the survey in either English or Spanish. A professional translation company translated survey items from English to Spanish.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

1,078 parents completed the survey; of these, 1,058 were included in analyses and 20 were excluded due to missing data on one or more key variables. First, we calculated descriptive statistics, including the percent of the sample indicating awareness of each harm and means and standard deviations of discouragement ratings for each health harm. Second, we estimated unadjusted Pearson’s correlation coefficients to determine the relationship between awareness of each health harm and harm-induced discouragement from purchasing sugary drinks.

Six health harms were asked about in the context of both children and adults. For these harms, we used paired t-tests to determine if discouragement from consuming sugary drinks differed based on whether the health harm was described as occurring in children compared to in adults. To determine differences in awareness of these harms, we used McNemar’s test in the same pairwise manner.

Next, analyses used ordinary least squares linear regression to examine predictors of overall discouragement (i.e., calculated for each participant as the mean discouragement across all health harms). The model included age, gender, sexual orientation, ethnicity, race, language of survey, education, annual household income, number of children in the household, use of the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), disordered eating behavior, and current sugary drink consumption, and overall awareness (calculated as the total number of health harms each participant indicated being aware of).

All analyses were conducted using StataSE 16 (Stata Corp, College Station, Texas) with two-tailed tests and a critical alpha of 0.05. All analyses were exploratory and therefore no hypotheses were specified regarding these variables before the data were collected and no analysis plan was pre-specified.

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

Most participants identified as female (59%) and white (74%), with almost half of the sample identifying as Latino (48%), consistent with the sampling strategy to over-sample Latino participants (Table 1). The majority of participants took the survey in English (86%). About a third (32%) used SNAP in the last year and 14% reported a history of disordered eating behaviors. A majority of participants reported they consumed sugary beverages more than once per week (74%). Similarly, 71% participants reported their children consumed sugary beverages more than once per week.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics

| Full Sample (n = 1078) |

Analytic Sample (n = 1058) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |

|

| ||||

| Age | ||||

| 18–29 years | 238 | 22% | 236 | 22% |

| 30–39 years | 563 | 52% | 553 | 52% |

| 40–54 years | 259 | 24% | 254 | 24% |

| 55+ years | 15 | 1% | 15 | 1% |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 445 | 41% | 434 | 41% |

| Female | 628 | 58% | 619 | 59% |

| Transgender | 5 | 0% | 5 | 0% |

| Sexual Orientation | ||||

| Straight | 994 | 92% | 977 | 92% |

| Gay or lesbian | 24 | 2% | 22 | 2% |

| Bisexual | 49 | 5% | 49 | 5% |

| Something else | 11 | 1% | 10 | 1% |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Hispanic | 514 | 48% | 505 | 48% |

| Race | ||||

| White | 796 | 74% | 782 | 74% |

| Black | 135 | 13% | 133 | 13% |

| Asian | 23 | 2% | 22 | 2% |

| Other/multiracial | 121 | 11% | 119 | 11% |

| American Indian/Alaskan Native | 1 | 0% | 1 | 0% |

| Pacific Islander | 2 | 0% | 1 | 0% |

| Preferred language to speak at home | ||||

| Mostly or only English | 691 | 64% | 680 | 64% |

| Mostly or only Spanish | 247 | 23% | 242 | 23% |

| Equally Spanish and English | 140 | 13% | 136 | 13% |

| Educational attainment | ||||

| Less than HS | 39 | 4% | 38 | 4% |

| HS/GED | 473 | 44% | 468 | 44% |

| 4-year college degree | 428 | 40% | 418 | 40% |

| Graduate degree | 138 | 13% | 134 | 13% |

| Household income, annual | ||||

| $0–$24,999 | 213 | 20% | 209 | 20% |

| $25,000–$49,999 | 288 | 27% | 283 | 27% |

| $50,000–$74,999 | 202 | 19% | 198 | 19% |

| $75,000+ | 375 | 35% | 368 | 35% |

| Number of children in household (0–18) | ||||

| 1 | 381 | 35% | 373 | 35% |

| 2 | 416 | 39% | 407 | 38% |

| 3 | 184 | 17% | 183 | 17% |

| 4 or more | 97 | 9% | 95 | 9% |

| Used SNAP in die last year | 344 | 32% | 339 | 32% |

| History of disordered eating* | 156 | 14% | 151 | 14% |

| Body mass index (BMl, kg/m2) | ||||

| Underweight | 37 | 3% | 37 | 4% |

| Healthy weight | 384 | 36% | 377 | 36% |

| Overweight | 327 | 31% | 322 | 31% |

| Obese | 314 | 30% | 309 | 30% |

| Paren’s frequency of SSB consumption | ||||

| 0–l times per week | 279 | 26% | 276 | 26% |

| > 1 time per week to <7 times per week | 370 | 34% | 362 | 34% |

| 1 to 2 times per day | 205 | 19% | 198 | 19% |

| More than 2 times per day | 224 | 21% | 222 | 21% |

| Child’s frequency of SSB consumption | ||||

| 0–1 times per week | 300 | 28% | 297 | 28% |

| > 1 time per week to <7 times per week | 425 | 39% | 416 | 39% |

| 1 to 2 times per day | 189 | 18% | 183 | 17% |

| More than 2 times per day | 164 | 15% | 162 | 15% |

| Language of survey administration | ||||

| English | 924 | 86% | 909 | 86% |

| Spanish | 154 | 14% | 149 | 14% |

Note.

Measured with four yes or no questions: “Are you satisfied with your eating patterns? “Do you ever eat in secret?’' “Does your weight affect the way you feel about yourself?” and “Do you currently suffer with or have you ever suffered in the past with an eating disorder?” Participants who responded with abnormal eating behaviors to at least three of the four questions were coded as exhibiting disordered eating (Cotton et al., 2003)

3.2. Awareness and Discouragement

Participants reported high awareness of SSBs contributing to some of the harms studied, including tooth decay in children (75%), obesity in children (74%), and weight gain in both children (73%) and in adults (73%; Table 2). Participants reported low awareness of other harms, such as sugary drinks contributing to infertility (16%), gout (17%) and arthritis (18%). The sample was most discouraged by obesity in children (mean=4.11, SD=1.12), pre-diabetes in children (mean=4.10, SD=1.13), and tooth decay in children (mean=4.07, SD=1.09; Table 2). Participants reported the lowest discouragement for infertility (mean=3.59, SD=1.38), gout (mean=3.63, SD=1.31), and arthritis (mean=3.69, SD=1.31) in adults. However, the magnitude of differences in discouragement among harms was small, as the difference between the mean discouragement for the most and least discouraging health harms was less than one point on the 1–5 Likert-type scale (4.11 vs. 3.59). The mean correlation between awareness and discouragement was r=0.20.

Table 2.

Awareness and discouragement of the harms of sugary drink consumption (n = 1,078)

| Discouragement |

Awareness |

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | % | r | |

|

| ||||

| Child Health Harms | ||||

| Obesity | 4.11 | 1.12 | 74 | 0.23 |

| Pre-diabetes | 4.10 | 1.13 | 66 | 0.27 |

| Tooth decay | 4.07 | 1.09 | 75 | 0.29 |

| Weight gain | 4.03 | 1.12 | 73 | 0.24 |

| Sleep problems | 3.84 | 1.20 | 43 | 0.14 |

| Anxiety and stress | 3.84 | 1.20 | 32 | 0.14 |

| Headaches | 3.80 | 1.20 | 30 | 0.19 |

| Adult Health Harms | ||||

| Type II diabetes | 4.06 | 1.14 | 68 | 0.25 |

| Obesity | 4.04 | 1.14 | 68 | 0.26 |

| Weight gain | 4.04 | 1.13 | 69 | 0.23 |

| Obesity, which increases risk of some cancers | 4.04 | 1.16 | 54 | 0.26 |

| Tooth decay | 3.97 | 1.16 | 62 | 0.23 |

| Heart disease | 3.97 | 1.20 | 44 | 0.21 |

| High blood pressure | 3.93 | 1.20 | 51 | 0.25 |

| Early death | 3.88 | 1.29 | 27 | 0.18 |

| Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease | 3.84 | 1.25 | 27 | 0.17 |

| Sleep problems | 3.78 | 1.23 | 40 | 0.17 |

| Headaches | 3.77 | 1.23 | 38 | 0.17 |

| Feeling tired | 3.72 | 1.23 | 41 | 0.21 |

| Arthritis | 3.69 | 1.31 | 18 | 0.10 |

| Gout | 3.63 | 1.31 | 18 | 0.19 |

| Infertility | 3.59 | 1.38 | 16 | 0.10 |

| Mean among all harms | 3.90 | 1.20 | 47 | 0.20 |

Discouragement rated on a Likert-type scale from 1 to 5, with 1 being the least discouraged and 5 being the most discouraged. SD = standard deviation. Pearson's correlation coefficient (r) unadjusted.

3.3. Comparing Harms among Children and Adults

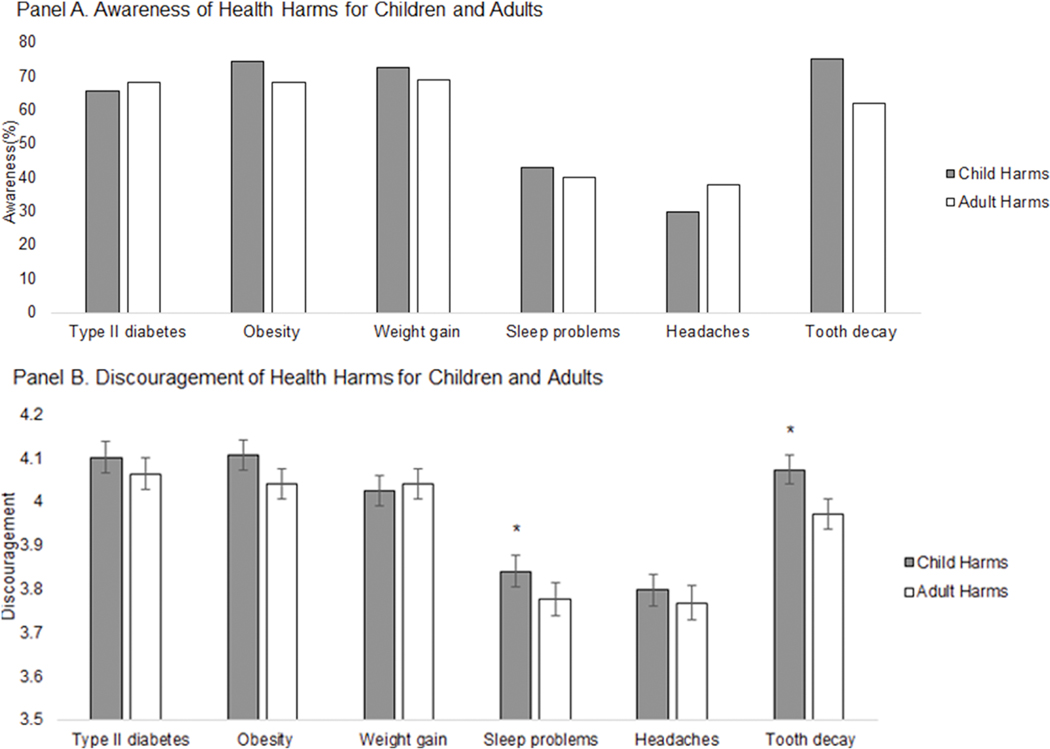

We evaluated six health harms that occur in both children and adults: diabetes (type II diabetes in adults, pre-diabetes in children), obesity, weight gain, sleep problems, headaches, and tooth decay. More participants were aware of SSBs contributing to sleep problems (p<0.001) and headaches (p<0.001) among adults than among children (Figure 1, Panel A). Conversely, participants were more aware of obesity (p=0.001) and tooth decay (p<0.001) among children than among adults. There were no differences in awareness of harms in children versus adults for diabetes or weight gain (p=0.063 and p=0.784 respectively). When comparing discouragement from consuming sugary drinks based on these harms, participants were more discouraged based on obesity (p=0.008), sleep problems (p=0.023), and tooth decay (p<0.001) among children than among adults (Figure 1, Panel B). There were no differences in discouragement based on diabetes (p=0.111), weight gain (p=0.525), or headaches (p=0.282).

Figure 1.

Awareness and Discouragement of Adult and Child Health Harms (n=1058). Discouragement is shown as mean ± SE. Asterisks (*) indicate statistical significance at the alpha=0.05 level. Panel A shows the results of McNemar’s test comparing participants’ awareness of the health harm in children compared to in adults. Panel B shows the results of paired t-tests to determine if discouragement from consuming sugary drinks differed based on whether the health harm occurred in children compared to in adults.

3.4. Predictors of Discouragement

In multivariable analyses examining relationships between demographic characteristics and overall discouragement, awareness of more health harms was associated with a greater overall discouragement from sugary drink purchasing (b=0.06, p<0.001). Women were less discouraged overall from purchasing sugary drinks compared to men (b=−0.17, p=0.01). Those with an annual household income of $50,000 or more were more discouraged than those with an annual household income less than $50,000 (b=0.16, p=0.03). None of the other factors were related to overall discouragement (all p>0.19). Sensitivity analyses explored whether experimental arm assignments in the earlier parts of the survey were significant predictors in this model, and whether the pattern of results changed after controlling for earlier group assignments. The pattern of findings was identical in terms of direction of effect and statistical significance, and prior experimental arm assignments were not associated with the outcome (p>0.10). Therefore, we retained a simplified model without group assignments as our final model.

4. Discussion

This study examined parents’ reactions to different health harms associated with sugary drink consumption. In a diverse sample of parents, we found that awareness of sugary drink-related health harms varied widely. Most participants were aware that sugary drinks contribute to harms such as tooth decay, type II and pre-diabetes, obesity, and weight gain. In contrast, less than 20% of participants were aware that sugary drinks contribute to infertility, arthritis, and gout, potentially reflecting the fact that these harms may be less prevalent in the population. Overall, parents reported that knowing about specific sugary drink-related health harms discouraged them from wanting to purchase sugary drinks (mean harm-induced discouragement: 3.90 out of 5). The harm that elicited the greatest discouragement was obesity in children. This suggests that messaging about obesity in children could be particularly effective; however, campaigns should take care to develop messages that do not elicit weight stigma.39–41 We also found that participants were generally more discouraged and more aware of harms described as occurring in children compared to harms occurring in adults. Messaging that highlights health harms in children may be therefore be particularly effective for encouraging parents to reduce their sugary drink purchasing, consistent with research showing that parents highly value nutritional quality for their children.42

The harms that fewer people had heard of were also generally rated slightly lower in terms of discouragement, in line with prior research showing that awareness and discouragement of tobacco-related harms are positively correlated.43–45 Campaigns could consider trying to raise awareness of lesser-known harms, with the eventual goal of using these harms in warnings or other messaging approaches to discourage sugary beverage purchasing. In the meantime, many of the better-known harms with high ratings on discouragement could be excellent candidates for health messaging interventions seeking to reduce sugary drink consumption.

Participants who were aware of a greater number of health harms, self-identified as men, or had an annual household income of $50,000 or more were more discouraged from consuming sugary drinks, although the magnitude of the effects was small. However, discouragement ratings did not differ by race or ethnicity. Given higher rates of sugary drink consumption and associated health effects among Black and Latino populations compared to white populations, the absence of differences in discouragement by race/ethnicity is an important and promising finding, as it suggests that health communication campaigns focusing on these harms would be unlikely to exacerbate disparities. This finding builds on prior studies finding that sugary drink health warnings tend to work equally well for diverse populations.46,47

One policy strategy to reduce sugary drink intake is requiring warning labels on product packaging. A recent meta-analysis found that warnings are effective at reducing sugary drink purchases compared to controls,8 but studies have not compared specific health harms to each other, so it was unknown which health harms warnings should highlight. Our study suggests that all of the health harms hold promise for discouraging sugary drink purchasing, and therefore that policymakers have a range of options for harms to describe in warnings, while also weighing other factors such as legal viability of messages given First Amendment constraints.48 Given that most warning policies aim to inform consumers, policymakers could also consider warnings that focus on lesser-known harms (e.g., heart disease or sleep problems), following the approach FDA used for the recently finalized graphic cigarette pack warnings.49 Prior studies have demonstrated that warnings’ impact may decline over time,50–53 suggesting that rotation of warning topics could be important for sustaining the benefits of warnings. The fact that multiple harms in our study were rated similarly highly suggests that there are multiple viable health harms to include in warnings that could be rotated on product packaging over time.

4.1. Strengths and Limitations

Study strengths include the evaluation of a comprehensive list of sugary drink health harms based on the latest evidence. Additionally, the sample included a large proportion of participants identifying as Latino, a priority population for sugary drink messaging research given higher rates of sugary drink consumption among Latino populations in the U.S.12

Study limitations include the use of a convenience sample, which may limit our ability to generalize the findings to the U.S. population; future studies could examine similar research questions in nationally representative samples. Additionally, the study did not experimentally compare the different health harms against a control, meaning we could not evaluate how harms would compare to neutral messages or no message. We also did not assess objective behavioral outcomes, although discouragement has been found to predict actual message effectiveness.17 Additionally, the health harms used in the survey were all supported by evidence from systematic reviews, meta-analyses, or prospective cohort studies; however, we did not evaluate a comprehensive list of all possible harms linked with sugary drink consumption. Future work should investigate how other harms like cardiovascular disease, mortality, and gestational diabetes may discourage people from sugary drink purchasing.

4.2. Conclusions

In our study of U.S. parents, we found widely varying levels of awareness of the health harms of sugary drink consumption. The majority of health harms highly discouraged participants from wanting to purchase sugary drinks: parents reported that knowing about specific sugary drink-related health harms discouraged them from wanting to purchase sugary drinks, especially obesity in children. This finding suggests that those designing health communication approaches have many promising options in terms of which harms to highlight. Future research would benefit from replicating this study with a nationally representative sample, comparing the health harms against a control group, and directly measuring messages’ effects on sugary drink purchasing and consumption behaviors.

Supplementary Material

Table 3.

Predictors of discouragement from consuming sugary drinks in multivariable linear regression (n = 1,045)

| b | SE | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Awareness of health harms | 0.05 | 0.005 | 0.00 |

| Age | 0.00 | 0.004 | 0.73 |

| Men (vs. women) | 0.15 | 0.064 | 0.02 |

| Transgender (vs. women)a | - | - | - |

| Straight or heterosexual (vs. gay, lesbian, bisexual, or other) | 0.13 | 0.113 | 0.24 |

| Not Latino (vs. Latino) | 0.03 | 0.065 | 0.70 |

| White race (vs. all other races) | 0.10 | 0.069 | 0.16 |

| Survey taken in English (vs. in Spanish) | 0.02 | 0.093 | 0.79 |

| High school graduate or less (vs. more than high school) | 0.04 | 0.067 | 0.54 |

| Annual household income of $50,000 or more (vs. less) | 0.16 | 0.070 | 0.03 |

| Number of children in household ages 0–18 | −0.04 | 0.029 | 0.21 |

| Used SNAP in the last year (vs. did not) | 0.02 | 0.069 | 0.73 |

| Exhibits an eating disorder (vs. does not) | −0.01 | 0.086 | 0.94 |

| Parental sugary drinks (<7 times per week vs 7 or more times per week) | −0.08 | 0.063 | 0.23 |

Note. Reference group is displayed in parentheses. A positive b value indicates that the non-referent group had higher levels of discouragement than the referent group, and a negative b value indicates that the non-reference group had lower levels of discouragement than the referent group. These values represent average higher or lower amounts of discouragement on a 5-point scale (e.g., men reported being .17 points less discouraged than women).

Results of gender (transgender vs. women) suppressed due to small ceil size for transgender participants.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the participants in this study. General support was provided by NIH grant to the Carolina Population Center, grant numbers P2C HD050924 and T32 HD007168. K01HL147713 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the NIH supported Marissa Hall’s time writing the paper. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Footnotes

Ethical Statement:

This study obtained ethical approval from the University of North Carolina Institutional Review Board (no. 19–0277). All participants gave informed consent before taking part in this study and all participants were over the age of 18.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Russo RG, Northridge ME, Wu B, Yi SS. Characterizing Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Consumption for US Children and Adolescents by Race/Ethnicity. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2020;7(6):1100–1116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Te Morenga L, Mallard S, Mann J. Dietary sugars and body weight: systematic review and meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials and cohort studies. BMJ. 2012;346:e7492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pan L, Li R, Park S, Galuska DA, Sherry B, Freedman DS. A longitudinal analysis of sugar-sweetened beverage intake in infancy and obesity at 6 years. Pediatrics. 2014;134 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):S29–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Malik VS, Popkin BM, Bray GA, Despres JP, Hu FB. Sugar-sweetened beverages, obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and cardiovascular disease risk. Circulation. 2010;121(11):1356–1364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Prather AA, Leung CW, Adler NE, Ritchie L, Laraia B, Epel ES. Short and sweet: Associations between self-reported sleep duration and sugar-sweetened beverage consumption among adults in the United States. Sleep Health. 2016;2(4):272–276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bernabé E, Vehkalahti MM, Sheiham A, Aromaa A, Suominen AL. Sugar-sweetened beverages and dental caries in adults: a 4-year prospective study. J Dent. 2014;42(8):952–958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huang C, Huang J, Tian Y, Yang X, Gu D. Sugar sweetened beverages consumption and risk of coronary heart disease: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. Atherosclerosis. 2014;234(1):11–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grummon AH, Hall MG. Sugary drink warnings: A meta-analysis of experimental studies. PLoS Med. 2020;17(5):e1003120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schwartz MB, Schneider GE, Choi YY, et al. Association of a Community Campaign for Better Beverage Choices With Beverage Purchases From Supermarkets. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(5):666–674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.!!! INVALID CITATION !!! {}.

- 11.Jordan A, Taylor Piotrowski J, Bleakley A, Mallya G. Developing media interventions to reduce household sugar-sweetened beverage consumption. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 2012;640(1):118–135. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bleich SN, Vercammen KA, Koma JW, Li Z. Trends in beverage consumption among children and adults, 2003–2014. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2018;26(2):432–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Graham G Disparities in cardiovascular disease risk in the United States. Curr Cardiol Rev. 2015;11(3):238–245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pool LR, Ning H, Lloyd-Jones DM, Allen NB. Trends in Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Cardiovascular Health Among US Adults From 1999–2012. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6(9). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hales CM, Carroll MD, Fryar CD, Ogden CL. Prevalence of obesity among adults and youth: United States, 2015–2016. NCHS data brief. 2017(288):1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hales CM, Carroll MD, Fryar CD, Ogden CL. Prevalence of Obesity and Severe Obesity Among Adults: United States, 2017–2018. NCHS data brief 2020(360):1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baig SA, Noar SM, Gottfredson NC, Lazard AJ, Ribisl KM, Brewer NT. Incremental criterion validity of message perceptions and effects perceptions in the context of anti-smoking messages. J Behav Med. 2021;44(1):74–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kelley DE, Boynton MH, Noar SM, et al. Effective message elements for disclosures about chemicals in cigarette smoke. Nicotine Tob Res. 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rohde JA, Noar SM, Mendel JR, et al. E-cigarette health harm awareness and discouragement: Implications for health communication. Nicotine Tob Res. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bleich SN, Vercammen KA. The negative impact of sugar-sweetened beverages on children’s health: an update of the literature. BMC Obes. 2018;5:6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Malik VS, Pan A, Willett WC, Hu FB. Sugar-sweetened beverages and weight gain in children and adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2013;98(4):1084–1102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bernabé E, Ballantyne H, Longbottom C, Pitts NB. Early Introduction of Sugar-Sweetened Beverages and Caries Trajectories from Age 12 to 48 Months. J Dent Res. 2020;99(8):898–906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Imamura F, O’Connor L, Ye Z, et al. Consumption of sugar sweetened beverages, artificially sweetened beverages, and fruit juice and incidence of type 2 diabetes: systematic review, meta-analysis, and estimation of population attributable fraction. Br J Sports Med. 2016;50(8):496–504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vartanian LR, Schwartz MB, Brownell KD. Effects of soft drink consumption on nutrition and health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(4):667–675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Emond JA, Patterson RE, Jardack PM, Arab L. Using doubly labeled water to validate associations between sugar-sweetened beverage intake and body mass among White and African-American adults. Int J Obes (Lond). 2014;38(4):603–609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ruff RR, Akhund A, Adjoian T, Kansagra SM. Calorie intake, sugar-sweetened beverage consumption, and obesity among New York City adults: findings from a 2013 population study using dietary recalls. J Community Health. 2014;39(6):1117–1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lauby-Secretan B, Scoccianti C, Loomis D, Grosse Y, Bianchini F, Straif K. Body Fatness and Cancer--Viewpoint of the IARC Working Group. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(8):794–798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim AE, Nonnemaker JM, Loomis BR, et al. Influence of point-of-sale tobacco displays and graphic health warning signs on adults: evidence from a virtual store experimental study. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(5):888–895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wijarnpreecha K, Thongprayoon C, Edmonds PJ, Cheungpasitporn W. Associations of sugar- and artificially sweetened soda with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. QJM. 2016;109(7):461–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xi B, Huang Y, Reilly KH, et al. Sugar-sweetened beverages and risk of hypertension and CVD: a dose-response meta-analysis. Br J Nutr. 2015;113(5):709–717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Malik VS, Hu FB. Fructose and Cardiometabolic Health: What the Evidence From Sugar-Sweetened Beverages Tells Us. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66(14):1615–1624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hu Y, Costenbader KH, Gao X, et al. Sugar-sweetened soda consumption and risk of developing rheumatoid arthritis in women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014;100(3):959–967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Choi HK, Curhan G. Soft drinks, fructose consumption, and the risk of gout in men: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2008;336(7639):309–312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Choi HK, Willett W, Curhan G. Fructose-rich beverages and risk of gout in women. JAMA. 2010;304(20):2270–2278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Malik VS, Li Y, Pan A, et al. Long-Term Consumption of Sugar-Sweetened and Artificially Sweetened Beverages and Risk of Mortality in US Adults. Circulation. 2019;139(18):2113–2125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Collin LJ, Judd S, Safford M, Vaccarino V, Welsh JA. Association of Sugary Beverage Consumption With Mortality Risk in US Adults: A Secondary Analysis of Data From the REGARDS Study. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(5):e193121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hatch EE, Wesselink AK, Hahn KA, et al. Intake of Sugar-sweetened Beverages and Fecundability in a North American Preconception Cohort. Epidemiology. 2018;29(3):369–378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Baig SA, Noar SM, Gottfredson NC, Boynton MH, Ribisl KM, Brewer NT. UNC Perceived Message Effectiveness: Validation of a brief scale. Ann Behav Med. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pearl RL, Puhl RM. Measuring internalized weight attitudes across body weight categories: validation of the modified weight bias internalization scale. Body Image. 2014;11(1):89–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Puhl R, Peterson JL, Luedicke J. Fighting obesity or obese persons? Public perceptions of obesity-related health messages. Int J Obes (Lond). 2013;37(6):774–782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Puhl RM, Heuer CA. The stigma of obesity: a review and update. Obesity. 2009;17(5):941–964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Norman Å, Berlin A, Sundblom E, Elinder LS, Nyberg G. Stuck in a vicious circle of stress. Parental concerns and barriers to changing children’s dietary and physical activity habits. Appetite. 2015;87:137–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hall MG, Ribisl KM, Brewer NT. Smokers’ and nonsmokers’ beliefs about harmful tobacco constituents: Implications for FDA communication efforts. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2014;16(3):343–350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Noar SM, Kelley DE, Boynton MH, et al. Identifying principles for effective messages about chemicals in cigarette smoke. Prev Med. 2018;106:31–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brewer NT, Morgan JC, Baig SA, et al. Public understanding of cigarette smoke constituents: three US surveys. Tob Control. 2016;26(5):592–599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Grummon AG, Taillie LS, Golden SD, Hall MG, Ranney LM, Brewer NT. Sugar-sweetened beverage health warnings and purchases: A randomized controlled trial. Am J Prev Med. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Grummon AH, Smith NR, Golden SD, Frerichs L, Taillie LS, Brewer NT. Health Warnings on Sugar-Sweetened Beverages: Simulation of Impacts on Diet and Obesity Among U.S. Adults. Am J Prev Med. 2019;57(6):765–774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pomeranz JL, Mozaffarian D, Micha R. Can the government require health warnings on sugars-weetened beverage advertisements? JAMA. 2018;319(3):227–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.U. S. Food and Drug Administration. Tobacco Products; Required Warnings for Cigarette Packages and Advertisements. 2020; https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2020/03/18/2020-05223/tobacco-products-required-warnings-for-cigarette-packages-and-advertisements.

- 50.Hammond D, Fong GT, Borland R, Cummings KM, McNeill A, Driezen P. Text and graphic warnings on cigarette packages: Findings from the International Tobacco Control Four Country Study. Am J Prev Med. 2007;32(3):202–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Strahan EJ, White K, Fong GT, Fabrigar LR, Zanna MP, Cameron R. Enhancing the effectiveness of tobacco package warning labels: a social psychological perspective. Tob Control. 2002;11(3):183–190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Thrasher JF, Abad-Vivero EN, Huang L, et al. Interpersonal communication about pictorial health warnings on cigarette packages: Policy-related influences and relationships with smoking cessation attempts. Soc Sci Med. 2015;164:141–149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Swayampakala K, Thrasher JF, Yong HH, et al. Over-Time Impacts of Pictorial Health Warning Labels and their Differences across Smoker Subgroups: Results from Adult Smokers in Canada and Australia. Nicotine Tob Res. 2018;20(7):888–896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cotton MA, Ball C, Robinson P. Four simple questions can help screen for eating disorders. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18(1):53–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.