Abstract

Background:

Many patients with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) experience acute and unexpected pain episodes over and above chronic background symptoms and there are emerging medications designed to treat such pain. We aimed to use conjoint analysis—a technique that elucidates how people make complex decisions—to examine patient preferences for emerging medicines for breakthrough IBS pain.

Methods:

We conducted a cross-sectional conjoint analysis survey among patients with Rome IV IBS and recurrent episodes of acute pain to assess the relative importance of medication attributes in their decision making. We also assessed what respondents would require of subcutaneous (SQ) therapies to consider their use.

Key Results:

Among 629 patients with Rome IV IBS, 606 (96.3%) reported ≥1 acute pain episodes in the past month. For the 461 participants with multiple attacks who completed the conjoint analysis, they prioritized medication efficacy (importance score 34.9%), avoidance of nausea (24.3%), and avoidance of constipation (12.2%) as most important in their decision making. These were followed by route of administration (10.3%), avoidance of headache (9.3%), and avoidance of drowsiness (8.9%). Moreover, 431 (93.5%) participants would consider SQ therapies for their acute pain; they had varying expectations on the minimum pain decrease and onset and duration of pain relief needed for considering their use.

Conclusions and Inferences:

The vast majority of patients with IBS experience breakthrough pain, and when selecting among therapies, they prioritize efficacy and most are willing to use a rapid-acting SQ treatment. These result support development of novel, effective medications—oral or SQ—for management of acute pain attacks.

Keywords: Irritable bowel syndrome, Abdominal pain, Oral, Patient preference, Subcutaneous

INTRODUCTION

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a chronic functional gastrointestinal (GI) disorder characterized by abdominal pain and changes in bowel habits.1 It is among the most commonly diagnosed GI conditions and depending on the diagnostic criteria used, the estimated worldwide prevalence ranges from 3.8% (Rome IV) to 9.2% (Rome III).2 Moreover, the economic burden associated with IBS is enormous and is estimated at $30 billion annually in the U.S.3

Although IBS is a multi-symptom disorder, abdominal pain is its defining characteristic1 and is a predominant feature of the IBS illness experience.4–8 Unlike other IBS symptoms, such as bloating or abnormalities in stool frequency or form, abdominal pain independently drives health-related quality of life decrements in IBS7 and is the principal driver of patient-reported symptom severity.6,8 In a study of 755 patients with IBS, abdominal pain was the most powerful predictor of patient-perceived severity among over 25 tested clinical factors.6 In short, IBS is defined by pain, and pain is the cornerstone of the IBS illness experience.

While there are many established IBS therapies that target chronic abdominal pain and bowel symptoms,9 there are now emerging medications that treat the acute, episodic breakthrough pain that often occurs over and above background symptoms—a model similar to prescribing on-demand, fast-acting therapies for acute migraine headache. For example, a subcutaneous (SQ) administered glucagon-like peptide 1 analogue was found to have benefit versus placebo in phase II testing,10 and other research is investigating the role of cannabinoid type 2 receptor agonists and histamine receptor H1 antagonists for IBS-related abdominal pain.11,12 As patients with severe IBS are willing to “try anything” to treat their symptoms,13–15 and given the increasing number of therapies in development for acute pain in IBS, we aimed to quantify the relative importance of medication attributes (e.g., route of administration, efficacy, side effects, etc.) in IBS patients’ decision making without making reference to any branded or investigational products. To accomplish this, we used conjoint analysis—a technique that determines how people make complex decisions by balancing competing factors that has been widely used in gastroenterology and beyond.16–22 Furthermore, as a separate aim, we evaluated patients’ willingness to use and minimum efficacy needed for them to consider SQ therapies for treating their breakthrough pain.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Design and Participant Recruitment

We performed a cross-sectional, self-administered, online survey between March 6 and March 24, 2020 of individuals in the U.S. with Rome IV IBS. This study was approved by the Cedars-Sinai Institutional Review Board (STUDY242).

To recruit participants, we collaborated with Cint (Stockholm, Sweden), a global survey research firm with access to >20 million research panelists in the U.S. Cint employs a reward system based on marketplace points, which we describe in detail elsewhere.23,24 Panelists aged ≥18 years were sent an email through Cint inviting them to complete an online survey. The email included a link to the survey along with the following text: “Based on the information stored in your [research panel] profile, we believe we have a survey that you will qualify & earn from. The survey takes approximately 15 to 20 minutes, and if you successfully complete it, your account will be credited with [incentive].” Users who clicked the link were brought to our survey home page where they were informed that the goal of the survey was to “learn how patients with chronic medical conditions make decisions about medicines.”

Study Population

Supplemental File 1 includes the full survey instrument. All respondents who accessed the survey were first asked whether they have been diagnosed by a physician with any of the following conditions (presented in random order): IBS, celiac disease; Crohn’s disease; eosinophilic esophagitis; gastroesophageal reflux disease; gastroparesis; ulcerative colitis; or none of the above. By having a ‘blinded’ screening question naming 7 different conditions, we aimed to maximize the likelihood that respondents had, in fact, been diagnosed by a physician with IBS and were not simply seeking compensation by participating in a survey.

Respondents who reported an IBS diagnosis were then asked how many episodes of acute abdominal pain lasting ≥30 minutes they experienced in the past month as well as the average pain severity during the attacks on a 0-10 scale. Acute abdominal pain was described as “pain that comes on suddenly and is typically more severe than chronic belly pain that you may be experiencing.” Afterwards, participants were guided through the Rome IV IBS questionnaire.1 Only those who met Rome IV IBS criteria and had ≥2 acute pain episodes in the past month with an average pain severity of ≥4 were eligible for the remaining survey items described below.

Survey Instrument

Using Conjoint Analysis to Assess Therapy Decision Making for Acute Abdominal Pain in IBS

Overview of Conjoint Analysis.

Eligible participants completed a conjoint analysis exercise, which we describe in detail elsewhere.25 In brief, conjoint analysis is a technique that quantifies how respondents make tradeoffs and is based on the idea that any product (e.g., a service, test, or treatment) can be described by its attributes and is valued based on the levels of these attributes.26 It is administered via a computer-based, interactive exercise where a series of side-by-side profiles of unbranded hypothetical products are presented with each profile having unique levels assigned to each attribute (Figure 1). Based on the respondent’s answer to the first comparison, an algorithm selects a new side-by-side comparison and asks the respondent to select the preferred profile for the stated objective.

FIGURE 1.

Sample choice tournament task where participants consider two hypothetical medication profiles side by side and decide which medication they would prefer for treating their acute IBS abdominal pain. Respondents were shown 18 different vignettes, each of which with varying attribute levels. IBS, irritable bowel syndrome.

Adaptive Choice-Based Conjoint (ACBC) Analysis for Therapy Decision Making for Acute IBS Pain.

We employed ACBC analysis software (Sawtooth Software, North Orem, UT) to determine how patients with IBS make decisions when selecting among the various treatment options for acute IBS pain. Table 1 displays the six attributes and their levels that were tested in the ACBC survey; these were modeled on characteristics of oral therapies commonly used for managing acute IBS pain (e.g., dicyclomine, hyoscyamine, opioids, peppermint oil)9,27 and a SQ therapy currently in the human clinical trial phase (ROSE-010).10 These attributes were selected based on input from the literature,9,10,27–31 IBS content experts on the research team (C.V.A., B.M.R.S.), and U.S. Food & Drug Administration (FDA) labels for currently marketed products to ensure accurate representation of factors relevant in the decision-making process.

TABLE 1.

Medication attributes and levels included in the conjoint analysis survey.

| Medication attribute | Attribute levels |

|---|---|

| Decrease in acute belly pain within 1 hour of taking the medicine | ● Severity of acute belly pain decreases by 10% ● Severity of acute belly pain decreases by 30% ● Severity of acute belly pain decreases by 50% ● Severity of acute belly pain decreases by 70% ● Severity of acute belly pain decreases by 90% ● Complete relief of belly pain |

| Route of administration | ● Taken orally as a pill ● Self-injected under the skin |

| Chance of constipation | ● 0% chance of constipation ● 5% chance of constipation ● 10% chance of constipation ● 15% chance of constipation ● 20% chance of constipation |

| Chance of drowsiness | ● 0% chance of drowsiness ● 10% chance of drowsiness ● 20% chance of drowsiness ● 30% chance of drowsiness |

| Chance of headache | ● 0% chance of headache ● 5% chance of headache ● 10% chance of headache ● 15% chance of headache |

| Chance of nausea | ● 0% chance of nausea ● 10% chance of nausea ● 20% chance of nausea ● 30% chance of nausea ● 40% chance of nausea |

The ACBC software used the inputted attributes and levels to create side-by-side profiles of hypothetical, unbranded acute IBS pain therapies as part of a ‘choice tournament’ with 18 distinct decisions (Figure 1). Before seeing the first set of profiles, participants were shown descriptions of the medication attributes to facilitate their understanding of each characteristic (Supplementary Figure 1). After participants completed the choice tournament, the software used hierarchical Bayes regression to estimate individual-level importance scores for each tested attribute17,32; attributes with higher importance scores are more highly valued in the decision-making process.17 For further information on ACBC and how importance scores are calculated, refer to the following link: http://links.lww.com/AJG/A215.25

Assessing Willingness to Use a SQ Therapy for Acute Abdominal Pain in IBS

After the conjoint vignettes, the survey presented respondents with a free-response question asking what they would require of a SQ medicine in order to consider using it. This was followed by multiple-choice questions assessing their desired minimum decrease in acute pain within 1 hour of taking the medicine, time to onset of pain relief, and duration of pain relief. We also inquired as to how willing they would be to use such a therapy if it only managed pain and did not treat bowel symptoms.

We then showed respondents a specific profile of a SQ medication modeled after ROSE-010, using efficacy and side effect data from its phase II trial (Supplementary Figure 2).10 Participants then reported how often they would use the medicine for their acute IBS pain as well as the minimum pain severity on a 0-10 scale needed in order to consider using it.

Demographics and Clinical Characteristics

Finally, respondents completed questions regarding sociodemographic information (e.g., age, sex, race/ethnicity, insurance, etc.) and clinical characteristics (e.g., current IBS and pain medication use, abdominal pain severity in past week as measured by National Institutes of Health Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System [PROMIS®],24,33 comorbidities). These data were collected to explore potential correlations between patient factors and therapy preferences.

Sample Size and Statistical Analyses

Based on conjoint analysis sample size precedents and recommendations from the software provider,34 we aimed to recruit at least 300 patients with Rome IV IBS to complete the conjoint analysis survey. However, to increase the number of meaningful responses to the open-ended questions, our goal was to recruit up to 500 individuals.

Statistical analyses were performed using Stata 16.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX). Descriptive analyses were used for patient sociodemographic and disease characteristics, importance scores derived from the ACBC, and willingness to use assessments. We also performed simulations using the ACBC data to assess the proportion of respondents who would prefer a SQ-administered medicine over an oral therapy across a range of efficacy levels, keeping side effect risks the same. We then performed multivariable linear and logistic regression models to adjust for potentially confounding factors and to calculate beta-coefficients, odds ratios, and adjusted p-values. The outcomes in the linear regressions were the importance scores for the six attributes tested in the conjoint analysis (Table 1). We also performed a logistic regression on their willingness to use the SQ medication modeled after ROSE-010. The regressions included patient-level sociodemographic and IBS clinical variables as covariates. A two-tailed p-value <.05 was considered significant.

Qualitative Analyses

For the open-ended question focused on assessing participants’ needs of a SQ medicine in order to consider using it for their pain, we used summative content analysis to examine their responses.35 We coded the free texts (word, sentence, and paragraph) and organized the codes into categories and subcategories.

RESULTS

Study Population

A total of 8,891 individuals were invited through Cint to complete the survey, of whom 5,823 (65.5%) accessed the site. Among those who accessed the survey, 629 (10.8%) reported having been diagnosed by a physician with IBS and met Rome IV criteria. They noted the following number of acute pain episodes that lasted ≥30 minutes in the past month: 0—n=23 (3.7%); 1—n=32 (5.1%); 2—n=132 (21.0%); 3—n=166 (26.4%); ≥4—n=276 (43.9%). For the 606 individuals who noted recent episodes of pain, they reported the following average pain severity on a 0-10 scale: 1—n=4 (0.7%); 2—n=2 (0.3%); 3—n=16 (2.6%); 4—n=29 (4.8%); 5—n=58 (9.6%); 6—n=108 (17.8%); 7—n=166 (27.4%); 8—n=139 (22.9%); 9—n=38 (6.3%); 10—n=46 (7.6%).

Among the 629 individuals with Rome IV IBS, we excluded these individuals: <2 acute pain episodes—n=54 (8.6%); finished survey too quickly—n=43 (6.8%); did not finish survey—n=36 (5.7%); average pain severity during episodes was <4—n=16 (2.5%); did not provide consent—n=13 (2.1%); provided implausible answers—n=6 (1.0%). Therefore, the analytic sample included 461 respondents with Rome IV IBS who experienced ≥2 acute pain episodes with an average pain severity of ≥4 in the past month; their demographics are shown in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Demographics of the study population (N=461).

| Variable | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age: | |

| 18-29 yo | 84 (18.2) |

| 30-39 yo | 147 (31.9) |

| 40-49 yo | 121 (26.3) |

| ≥50 yo | 109 (23.6) |

| Sex: | |

| Male | 146 (31.7) |

| Female | 314 (68.1) |

| Prefer not to say | 1 (0.2) |

| Race/ethnicity: | |

| Non-Hispanic White | 340 (73.8) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 38 (8.2) |

| Latino | 56 (12.2) |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 11 (2.4) |

| Other | 16 (3.5) |

| Educational attainment: | |

| High school degree or less | 100 (21.7) |

| Some college education | 120 (26.0) |

| College degree | 195 (42.3) |

| Graduate degree | 46 (10.0) |

| Marital status: | |

| Married | 232 (50.3) |

| Not married | 229 (49.7) |

| Total household income, $: | |

| <50,000 | 187 (40.6) |

| 50,000-100,000 | 183 (39.7) |

| ≥100,001 | 79 (17.1) |

| Prefer not to say | 12 (2.6) |

| Employment status: | |

| Not employed † | 161 (34.9) |

| Employed or student | 300 (65.1) |

| Health insurance status: | |

| No insurance | 43 (9.3) |

| Has insurance | 418 (90.7) |

| Has condition that affects GI tract ‡ | 330 (71.6) |

| U.S. region: | |

| Northeast | 71 (15.4) |

| South | 206 (44.7) |

| Midwest | 111 (24.1) |

| West | 73 (15.8) |

GI, gastrointestinal.

Includes those who reported being unemployed, unable to work owing to a disability, on leave of absence from work, retired, or a homemaker.

Includes celiac disease, cirrhosis, Crohn’s disease, diabetes, eosinophilic esophagitis, fibromyalgia, gallstones, gastroesophageal reflux disease, gastroparesis, HIV/AIDS, pancreatitis, peptic ulcer disease, thyroid disease, and ulcerative colitis.

IBS Characteristics and Medication Use

The study cohort’s IBS characteristics are listed in Table 3. We found that 47.9%, 27.3%, 24.5%, and 0.2% had mixed IBS (IBS-M), IBS with diarrhea (IBS-D), IBS with constipation (IBS-C), and unsubtyped IBS (IBS-U), respectively. More than half of the overall cohort reported abdominal pain as their most bothersome symptom as well as reported ≥4 episodes of acute abdominal pain in the past month. The mean pain severity during these acute episodes was 7.1 (standard deviation, 1.5).

TABLE 3.

Study cohort’s IBS characteristics (N=461).

| Variable | n (%) or mean ± standard deviation |

|---|---|

| IBS subtype: | |

| IBS-C | 113 (24.5) |

| IBS-D | 126 (27.3) |

| IBS-M | 221 (47.9) |

| IBS-U | 1 (0.2) |

| Most bothersome IBS symptom: | |

| Abdominal pain | 258 (56.0) |

| Constipation | 100 (21.7) |

| Diarrhea | 92 (20.0) |

| Not sure | 11 (2.4) |

| Number of acute pain episodes in past month: | |

| 2 episodes | 89 (19.3) |

| 3 episodes | 129 (28.0) |

| ≥4 episodes | 243 (52.7) |

| Average severity of acute pain episodes in past month (0-10 scale): | |

| 4 | 21 (4.6) |

| 5 | 42 (9.1) |

| 6 | 86 (18.7) |

| 7 | 138 (29.9) |

| 8 | 111 (24.1) |

| 9 | 28 (6.1) |

| 10 | 35 (7.6) |

| PROMIS abdominal pain score (percentile) † | 78.5 ± 17.0 |

| Currently taking IBS medicine | 343 (74.4) |

| Currently taking other medicine for pain | 433 (93.9) |

IBS, irritable bowel syndrome; IBS-C, irritable bowel syndrome with constipation; IBS-D, irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhea; IBS-M, mixed irritable bowel syndrome; IBS-U, unsubtyped irritable bowel syndrome; PROMIS, Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System.

Assesses severity of respondents’ abdominal pain in the past week. Higher score corresponds to more severe symptoms.

Overall, 343 (74.4%) of respondents reported currently taking an IBS therapy that can reduce pain. We also found that 433 (93.9%) were taking other medicines (e.g., acetaminophen, opioids, cannabidiol) for pain related to their IBS or otherwise. Supplementary Table 1 shows the individual medicines reported by respondents.

Using Conjoint Analysis to Assess Therapy Decision Making for Acute Abdominal Pain in IBS

The average importance scores calculated by the ACBC algorithm among the entire cohort were as follows: decrease in acute belly pain within 1 hour of taking the medicine—34.9%; chance of nausea—24.3%; chance of constipation—12.2%; route of administration—10.3%; chance of headache—9.3%; chance of drowsiness—8.9%. Supplementary Table 2 presents results from the regression analyses on the importance scores. Save for a few exceptions, IBS subtype and clinical characteristics and demographics were largely not predictive of decision making.

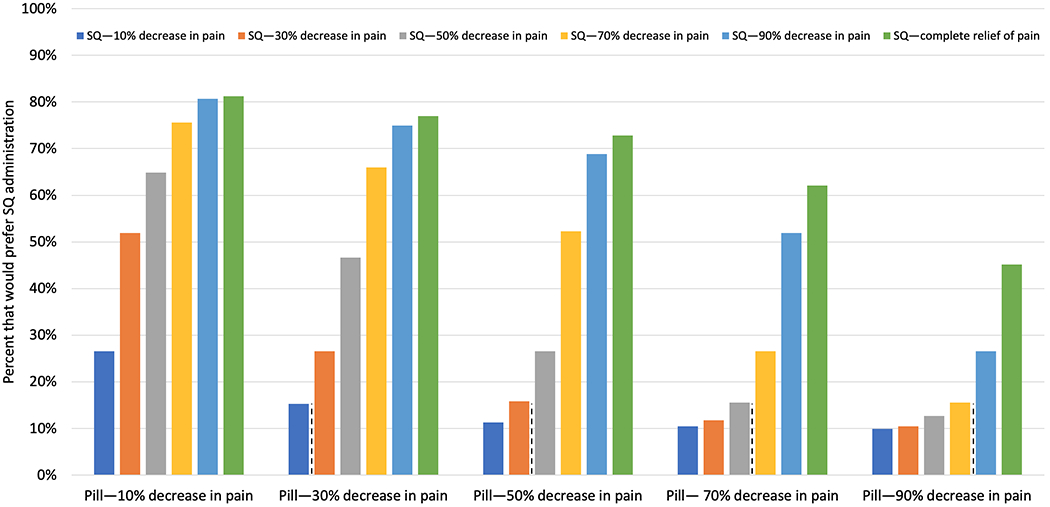

Figure 2 presents findings from the simulations that assessed the proportion of respondents who would prefer a SQ-administered medicine over an oral therapy across a range of efficacy levels, keeping risk of side effects the same. We found that increasing efficacy of the SQ therapy was associated with an increased proportion of those who would prefer it over pills. For example, 51.9% of individuals would opt for a SQ drug that decreases pain by 30% within 1 hour versus an oral option that reduces pain by only 10%.

FIGURE 2.

Simulations assessing the proportion of respondents who would prefer a SQ-administered medicine over an oral therapy across a range of efficacy levels, keeping all other factors the same (e.g., risk of side effects). For example, 66.0% of individuals would choose a SQ therapy that decreases pain by 70% within 1 hour when compared to an oral option that reduces pain by only 30%.

Assessing Willingness to Use a SQ Therapy for Acute Abdominal Pain in IBS

Supplementary Figure 3 shows a word cloud generated from the qualitative content analysis detailing respondents’ considerations when thinking about whether to use a SQ therapy for their acute pain. The most common consideration was drug efficacy, which encompassed both short- and long-term pain relief. Following were avoidance of side effects (e.g., nausea, constipation) and administration considerations including the need for painless injections, ease of use, syringe characteristics, and frequency of use. Factors mentioned less often were financial considerations, insurance coverage, and the reputation of the drug.

Through multiple-choice questions, we found that 30 (6.5%) of 461 respondents would never consider using a SQ therapy to manage their acute IBS pain. Supplementary Table 3 presents findings from the 431 individuals who were open to SQ therapies on the minimum pain decrease within 1 hour and time to and duration of pain relief required for them to consider using such medicines. Participants reported the following when asked how willing they would be to use a SQ therapy that only treated acute pain and not bowel symptoms: not at all—n=52 (12.1%); a little bit—n=78 (18.1%); somewhat—n=140 (32.5%); quite a bit—n=97 (22.5%); very much—n=64 (14.9%). When comparing IBS subtypes, we found no differences among the groups in the required minimum pain decrease (p=.92), pain relief onset (p=.23), pain relief duration (p=.68), and willingness to use the medication even if it did not impact bowel symptoms (p=.27).

All respondents (n=461) were also shown a specific medication profile with efficacy and side effects modeled after ROSE-010, and they noted the following when asked how often they would use it to treat their acute pain: never—n=51 (11.1%); rarely—n=78 (16.9%); sometimes—n=130 (28.2%); most of the time—n=139 (30.2%); always—n=63 (13.7%). The 410 patients who stated that they would be willing to use it reported that their pain severity needed to be at least the following: ≤2—n=12 (2.9%); 3—n=11 (2.7%); 4—n=18 (4.4%); 5—n=45 (11.0%); 6—n=52 (12.7%); 7—n=90 (22.0%); 8—n=102 (24.9%); 9—n=45 (11.0%); 10—n=35 (8.5%). Figure 3 shows respondents’ willingness to use the specific SQ medication stratified by their familiarity with SQ therapies. Increasing familiarity with self-injectables was associated with higher willingness to use ROSE-010.

FIGURE 3.

Respondents’ willingness to use a specific SQ medication modeled after ROSE-010 for treatment of their acute abdominal pain stratified by their familiarity with SQ medicines (n=410). SQ, subcutaneous.

Table 4 presents the regression on willingness to use the SQ medication patterned after ROSE-010; individuals deemed willing to use the therapy (n=202; 43.8%) were those who would use it most or all of the time for their pain attacks. More severe abdominal pain as measured by PROMIS, increasing age, Latino race/ethnicity, employed status, and presence of comorbidities were associated with increased odds for being likely to use the medication. No significant associations were seen with IBS subtype or the remaining clinical characteristics and demographics.

TABLE 4.

Predictors of willingness to use a specific medication modeled after ROSE-010 for acute IBS pain (N=461).

| Variable | Not, rarely, or sometimes willing to use ROSE-010 (n=259) | Most of the time or always willing to use ROSE-010 (n=202) | OR [95% CI] |

|---|---|---|---|

| IBS subtype: | |||

| IBS-C | 70 (27.0) | 43 (21.3) | Ref |

| IBS-D | 77 (29.7) | 49 (24.3) | 1.02 [0.56-1.85] |

| IBS-M | 111 (42.9) | 110 (54.5) | 1.54 [0.90-2.61] |

| IBS-U | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | --- † |

| Number of acute pain episodes in past month: | |||

| 2 episodes | 58 (22.4) | 31 (15.4) | Ref |

| 3 episodes | 73 (28.2) | 56 (27.7) | 1.10 [0.59-2.07] |

| ≥4 episodes | 128 (49.4) | 115 (56.9) | 1.00 [0.56-1.81] |

| Average severity of acute pain episodes in past month (0-10 scale) | 6.8 ± 1.5 | 7.4 ± 1.4 | 1.12 [0.94-1.32] |

| PROMIS abdominal pain score (percentile; higher=more severe) | 74.8 ± 17.6 | 83.3 ± 14.9 | 1.03 [1.01-1.04] |

| Currently taking IBS medicine | 180 (69.5) | 163 (80.7) | 1.24 [0.74-2.08] |

| Currently taking other medicine for pain | 243 (93.8) | 190 (94.1) | 0.92 [0.38-2.23] |

| Age: | |||

| 18-29 yo | 57 (22.0) | 27 (13.4) | Ref |

| 30-39 yo | 74 (28.6) | 73 (36.1) | 2.36 [1.25-4.47] |

| 40-49 yo | 64 (24.7) | 57 (28.2) | 2.22 [1.15-4.30] |

| ≥50 yo | 64 (24.7) | 45 (22.3) | 2.37 [1.13-4.96] |

| Sex: | |||

| Male | 68 (26.3) | 78 (38.6) | Ref |

| Female | 190 (73.4) | 124 (61.4) | 0.74 [0.46-1.20] |

| Prefer not to say | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | --- † |

| Race/ethnicity: | |||

| Non-Hispanic White | 202 (78.0) | 138 (68.3) | Ref |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 22 (8.5) | 16 (7.9) | 0.81 [0.37-1.80] |

| Latino | 19 (7.3) | 37 (18.3) | 2.58 [1.30-5.11] |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 8 (3.1) | 3 (1.5) | 0.59 [0.13-2.62] |

| Other | 8 (3.1) | 8 (4.0) | 1.36 [0.44-4.21] |

| Educational attainment: | |||

| High school degree or less | 52 (20.1) | 48 (23.8) | Ref |

| Some college education | 71 (27.4) | 49 (24.3) | 0.74 [0.40-1.38] |

| College degree | 111 (42.9) | 84 (41.6) | 0.53 [0.29-0.96] |

| Graduate degree | 25 (9.7) | 21 (10.4) | 0.52 [0.22-1.25] |

| Marital status: | |||

| Married | 121 (46.7) | 111 (55.0) | Ref |

| Not married | 138 (53.3) | 91 (45.1) | 0.78 [0.50-1.21] |

| Total household income, $: | |||

| <50,000 | 116 (44.8) | 71 (35.2) | Ref |

| 50,000-100,000 | 91 (35.1) | 92 (45.5) | 1.31 [0.78-2.18] |

| ≥100,001 | 43 (16.6) | 36 (17.8) | 1.07 [0.53-2.17] |

| Prefer not to say | 9 (3.5) | 3 (1.5) | 0.96 [0.23-4.06] |

| Employed or student | 154 (59.5) | 146 (72.3) | 1.98 [1.15-3.40] |

| Has health insurance | 232 (89.6) | 186 (92.1) | 1.82 [0.86-3.86] |

| Has condition that affects GI tract | 168 (64.9) | 162 (80.2) | 2.07 [1.28-3.37] |

| U.S. region: | |||

| Northeast | 46 (17.8) | 25 (12.4) | Ref |

| South | 107 (41.3) | 99 (49.0) | 1.52 [0.79-2.90] |

| Midwest | 66 (25.5) | 45 (22.3) | 1.23 [0.60-2.53] |

| West | 40 (15.4) | 33 (16.3) | 1.41 [0.66-3.03] |

Note: Data are presented as n (%) or mean ± standard deviation. The logistic regression model adjusted for all covariates in the table.

CI, confidence interval; GI, gastrointestinal; IBS, irritable bowel syndrome; IBS-C, irritable bowel syndrome with constipation; IBS-D, irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhea; IBS-M, mixed irritable bowel syndrome; IBS-U, unsubtyped irritable bowel syndrome; PROMIS, Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System; OR, odds ratio; Ref, reference.

Those with IBS-U (n=1) and unknown sex (n=1) were not included in the regression model as they perfectly predicted the outcome.

DISCUSSION

In this nationwide survey of patients with Rome IV IBS, we found that episodes of acute pain over and above background IBS symptoms are common with 96.3% of respondents reporting such episodes in the past month. This is important because presence of pain attacks is not an explicit component of the IBS diagnostic criteria and may not be a symptom frequently assessed for in clinical practice (in contrast to chronic pain). Among patients with recurrent, severe episodes of acute pain, we found through conjoint analysis that they prioritize medication efficacy and avoidance of nausea when selecting among pain therapies. We also found that 93.5% of participants would consider using a SQ therapy for their pain and they had varying expectations on the minimum pain decrease and onset and duration of pain relief needed for considering its use.

Our study observed that persons with Rome IV IBS in the general community commonly experience breakthrough pain. Namely, 96.3% of individuals reported at least 1 episode of acute pain that lasted ≥30 minutes in the past month and 43.9% even noted experiencing ≥4 episodes. With respect to severity, 91.6% of respondents reported that their average pain score during these episodes was at least 5 on a 0-10 scale. Hellström and colleagues similarly characterized acute pain attacks in those who met Rome III criteria.36 They noted that the median attack frequency was 5.4 per month with a median intensity score of 8 and 63% of the episodes interfered with patients’ work and daily activities.36 Additionally, they found that most pain episodes went untreated; pain medications were only used by 44% of patients during 29% of attacks.36 The low usage of treatments during these attacks is likely related to the lack of effective U.S. FDA-approved pain relief therapies specific for IBS. Given the high prevalence and significant burden associated with breakthrough IBS pain, development of such medications is urgently needed.

While conjoint analysis has been widely used to examine clinical decision making in other areas of healthcare,16–22 it has not been commonly employed to assess IBS therapy decision making. While prior studies have examined IBS patients’ decision making and willingness to take risks with hypothetical medications,13–15 our study is the first to use conjoint analysis to examine patient preferences for medications—both oral and SQ—that specifically treat pain attacks related to IBS. As expected, patients highly prioritized pain relief followed by avoidance of nausea and constipation. Route of administration, on the other hand, was the 4th most important medication attribute out of 6 total included in the conjoint exercise. Through standalone questions, we also noted that 93.5% of respondents would consider using a SQ therapy for management of their pain. These results strongly suggest that patients with Rome IV IBS suffering from recurrent pain attacks are open to using SQ therapies for management of their symptoms.

However, when comparing responses between participants’ requirements of a generic SQ therapy versus their willingness to use a specific medication modeled after ROSE-010, we noted some discordance. Namely, when respondents were asked—without providing additional context—about their requirements for using a generic SQ medication, they had very high expectations for its associated pain relief, time to onset, and duration of relief. Conversely, when presented with a specific profile of a medicine with an effectiveness that was lower than what most participants desired along with its potential side effects, 43.8% of participants reported they would use it most or all the time for treating their acute pain. While the reason behind this disconnect is unclear, it is consistent with prior survey data that found that 46% of patients with IBS are willing to “try anything” to help manage their condition.15

Though there are limited studies examining IBS patients’ willingness to use and acceptability of SQ therapies for breakthrough pain, such medications have been widely used in other conditions including diabetes, growth disorders, and multiple sclerosis.37 The most comparable application to our study’s IBS use case is in managing migraines, as SQ sumatriptan is effective, well-tolerated, and well-accepted among patients for treating acute migraine attacks.37–41 For example, Gross et al. observed that 88% of patients using SQ sumatriptan reported headache relief within 1 hour of the injection and 90% found it easy to use and would use it again in the future.40 Importantly, patients were first briefed in SQ device operation through an instruction leaflet along with an in-clinic explanation and study coordinator-guided practice injections with saline which likely contributed to the high satisfaction.40 Of note, in our study we found a link between willingness to consider a SQ pain medicine with familiarity with self-injection; 74.6% of patients who were either very much or quite a bit familiar with SQ therapies were willing to use a SQ medicine modeled after ROSE-010 for their pain. This finding, combined with the prior migraine literature,37–41 strongly suggests that when SQ options for acute IBS pain become available, clinics should provide structured teaching and education around how and when to use them in an effort to improve uptake and adherence.

Notably, in our simulations assessing the proportion of respondents who would prefer a SQ medicine over an oral therapy, we observed that some individuals preferred the SQ option even if it was equally or less effective than the pill. While this seems counter-intuitive, this finding may reflect some respondents’ difficulties in swallowing pills or aversion to taking pills when they have concomitant nausea and vomiting during their pain attacks. Of note, Schiele et al. found that 37% of survey respondents reported difficulty swallowing tablets and capsules and such issues were not identified by their primary care provider in 70% of cases.42 Additionally, some may prefer SQ therapies because they have preconceived beliefs that injectables are always more potent with quicker onset versus pills. These data suggest that treatment decision making for acute IBS pain is highly individualized and that effective medications with different administration routes (e.g., oral, SQ, sublingual, intranasal) may be needed.

Our study has several strengths. First, we recruited nearly 500 patients with Rome IV IBS experiencing recurrent acute pain episodes from all across the U.S. By doing so, we shed light on their burden of illness and approach to therapy decision making when choosing among the different options for their acute pain. Second, to identify participants, we used the validated Rome IV IBS questionnaire which has a high specificity of 97%.43 Third, we employed a mixed-methods approach (conjoint analysis, qualitative assessments, and standalone multiple-choice questions) to comprehensively assess what factors are important to patients when selecting a medicine for their pain as well as their willingness and thresholds for using potential SQ therapies.

There are limitations to our survey. First, we only recruited subjects from the U.S.; our findings may not be generalizable to patients with IBS in other parts of the world. Given the high global prevalence of IBS,2 additional studies in other countries examining breakthrough pain therapy decision making are warranted. Second, the IBS diagnosis was not confirmed by a healthcare professional. We attempted to minimize IBS misclassification by employing both a blinded screening question that listed IBS along with six other physician-diagnosed conditions as well as the Rome IV questionnaire which is highly specific43 and widely used in population-based survey studies.44–50 Third, we limited the conjoint analysis to six medication attributes. Patients may have other considerations when selecting a therapy, as revealed in our qualitative analyses (e.g., recommendation from the provider, tested and approved by the U.S. FDA, cost). However, this was by design, as ACBC surveys can become unwieldy with too many attributes. We thus focused on six core attributes that were deliberately chosen based on prior literature9,10,27–30 and input from content experts on the research team. Relatedly, as the study was focused on pharmacotherapies for acute IBS pain, we did not model non-pharmacologic therapies in the conjoint analysis. As some patients may prefer alternative treatments (e.g., neurostimulation,51 psychotherapy, relaxation techniques52) over medications for their acute pain, future conjoint analyses that model both classes of therapies are warranted. Prior to doing so, though, investigators should consider conducting focus groups that qualitatively examine how patients with IBS consider pharmacologic versus non-pharmacologic treatments for acute pain in order to identify the most pertinent attributes for inclusion in the conjoint analysis so that it remains manageable for respondents. Fourth, despite the interactive design of the conjoint analysis and limitation to 18 conjoint vignettes, the serial decision making may have been challenging for some patients. Those with lower numeracy skills may also have experienced difficulty interpreting the chances for improvement in pain and side effects. We attempted to minimize this issue by consistently and simply presenting the probabilities as percentages throughout the ACBC exercises. Finally, when assessing respondents’ willingness to use a SQ therapy, participants were only presented with its route of administration and potential side effects; other important factors such as out-of-pocket costs, insurance coverage, and portability were not considered. Of note, Shah and colleagues found that patients with IBS with annual incomes of <$75,000 and >$75,000 would be willing to pay $73 and $197 per month, respectively, for a hypothetical medicine that resolves their pain.14

In summary, the vast majority of patients with Rome IV IBS in the general community experience recurrent breakthrough abdominal pain and they prioritize efficacy when selecting among the therapeutic options. Moreover, most people are open to using SQ treatments for managing their pain attacks. Given the high prevalence of IBS combined with its significant impact on health-related quality of life and daily activities, continued development of novel, effective medications—oral and SQ—for management of acute IBS pain is warranted.

Supplementary Material

SUPPLEMENTARY FIGURE 1. Descriptions of each medication attribute shown to participants prior to the conjoint exercises to facilitate their understanding of each characteristic. Each panel was shown on a separate page.

SUPPLEMENTARY FIGURE 2. Description of a specific subcutaneous therapy for acute abdominal pain from irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) modeled after ROSE-010.

SUPPLEMENTARY FIGURE 3. Qualitative content analysis detailing what respondents would require of a subcutaneous therapy in order to consider using it for managing their acute abdominal pain from irritable bowel syndrome. The font sizes correspond to the prevalence.

Acknowledgements:

Christopher V. Almario, MD, MSHPM; Brennan M.R. Spiegel, MD, MSHS: substantial contributions to the conception and design of the work; acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data for the work; drafting the work and revising it critically for important intellectual content; final approval of the version to be published. Samuel Eberlein, MHDS; Carine Khalil, PhD: substantial contributions to the design of the work; acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data for the work; drafting the work and revising it critically for important intellectual content; final approval of the version to be published.

Funding:

This study was funded by Rose Pharma LLC. The study sponsor did not have a role in the collection, analysis, or interpretation of data, or drafting of the manuscript. The Cedars-Sinai Center for Outcomes Research and Education (CS-CORE) is supported by The Marc and Sheri Rapaport Fund for Digital Health Sciences & Precision Health. Drs. Almario and Spiegel are supported by a CTSI grant from the NIH/NCATS UL1TR001881-01.

Disclosures:

Dr. Christopher Almario—consulting fees from Alnylam Pharmaceuticals, Arena Pharmaceuticals, and Phathom Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Brennan Spiegel—grant support from AstraZeneca, Ironwood Pharmaceuticals, Rose Pharma LLC, Salix Pharmaceuticals, and Takeda Pharmaceuticals; advisory board consulting fees from Ironwood Pharmaceuticals, Synergy Pharmaceuticals, and Takeda Pharmaceuticals. The remaining authors do not have any relevant disclosures.

Abbreviations:

- CI

confidence interval

- FDA

Food & Drug Administration

- GI

gastrointestinal

- IBS

irritable bowel syndrome

- IBS-C

irritable bowel syndrome with constipation

- IBS-D

irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhea

- IBS-M

mixed irritable bowel syndrome

- IBS-U

unsubtyped irritable bowel syndrome

- OR

odds ratio

- PROMIS

Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System

- Ref

reference

- SD

standard deviation

- SQ

subcutaneous

Footnotes

Writing Assistance: No medical writing support was received. All content for the manuscript was written and developed by the authors.

Data Availability Statement:

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, B.M.R.S, upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mearin F, Lacy BE, Chang L, et al. Bowel Disorders. Gastroenterology. 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oka P, Parr H, Barberio B, Black CJ, Savarino EV, Ford AC. Global prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome according to Rome III or IV criteria: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;5(10):908–917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lembo AJ. The clinical and economic burden of irritable bowel syndrome. Pract Gastroenterol. 2007;31(Suppl):3–9. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Whitehead WE, Crowell MD, Bosmajian L, et al. Existence of irritable bowel syndrome supported by factor analysis of symptoms in two community samples. Gastroenterology. 1990;98(2):336–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Taub E, Cuevas JL, Cook EW 3rd, Crowell M, Whitehead WE Irritable bowel syndrome defined by factor analysis. Gender and race comparisons. Dig Dis Sci. 1995;40(12):2647–2655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Spiegel B, Strickland A, Naliboff BD, Mayer EA, Chang L. Predictors of patient-assessed illness severity in irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Spiegel BM, Gralnek IM, Bolus R, et al. Clinical determinants of health-related quality of life in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164(16):1773–1780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lembo A, Ameen VZ, Drossman DA. Irritable bowel syndrome: toward an understanding of severity. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3(8):717–725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ford AC, Moayyedi P, Chey WD, et al. American College of Gastroenterology Monograph on management of irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113(Suppl 2):1–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hellstrom PM, Hein J, Bytzer P, Bjornsson E, Kristensen J, Schambye H. Clinical trial: the glucagon-like peptide-1 analogue ROSE-010 for management of acute pain in patients with irritable bowel syndrome: a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;29(2):198–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ford AC, Sperber AD, Corsetti M, Camilleri M. Irritable bowel syndrome. Lancet. 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wouters MM, Balemans D, Van Wanrooy S, et al. Histamine receptor H1-mediated sensitization of TRPV1 mediates visceral hypersensitivity and symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2016;150(4):875–887.e879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lacy BE, Everhart KK, Weiser KT, et al. IBS patients’ willingness to take risks with medications. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107(6):804–809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shah SL, Janisch NH, Crowell M, Lacy BE. Patients with irritable bowel syndrome are willing to take substantial medication risks for symptom relief. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;19(1):80–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Törnblom H, Goosey R, Wiseman G, Baker S, Emmanuel A. Understanding symptom burden and attitudes to irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhoea: Results from patient and healthcare professional surveys. United European Gastroenterol J. 2018;6(9):1417–1427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johnson FR, Ozdemir S, Mansfield C, et al. Crohn’s disease patients’ risk-benefit preferences: serious adverse event risks versus treatment efficacy. Gastroenterology. 2007;133(3):769–779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lichtenstein GR, Waters HC, Kelly J, et al. Assessing drug treatment preferences of patients with Crohn’s disease. Patient. 2010;3(2):113–123. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hodgkins P, Swinburn P, Solomon D, Yen L, Dewilde S, Lloyd A. Patient preferences for first-line oral treatment for mild-to-moderate ulcerative colitis: a discrete-choice experiment. Patient. 2012;5(1):33–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johnson FR, Hauber B, Ozdemir S, Siegel CA, Hass S, Sands BE. Are gastroenterologists less tolerant of treatment risks than patients? Benefit-risk preferences in Crohn’s disease management. J Manag Care Pharm. 2010;16(8):616–628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnson FR, Ozdemir S, Mansfield C, Hass S, Siegel CA, Sands BE. Are adult patients more tolerant of treatment risks than parents of juvenile patients? Risk Anal. 2009;29(1):121–136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bewtra M, Fairchild AO, Gilroy E, et al. Inflammatory bowel disease patients’ willingness to accept medication risk to avoid future disease relapse. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110(12):1675–1681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Joo W, Almario CV, Ishimori M, et al. Examining treatment decision-making among patients with axial spondyloarthritis: insights from a conjoint analysis survey. ACR Open Rheumatol. 2020;2(7):391–400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Menees SB, Almario CV, Spiegel BMR, Chey WD. Prevalence of and factors associated with fecal incontinence: results from a population-based survey. Gastroenterology. 2018;154(6):1672–1681.e1673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Almario CV, Ballal ML, Chey WD, Nordstrom C, Khanna D, Spiegel BMR. Burden of gastrointestinal symptoms in the United States: results of a nationally representative survey of over 71,000 Americans. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113(11):1701–1710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Almario CV, Keller MS, Chen M, et al. Optimizing selection of biologics in inflammatory bowel disease: development of an online patient decision aid using conjoint analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113(1):58–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bridges JF, Hauber AB, Marshall D, et al. Conjoint analysis applications in health--a checklist: a report of the ISPOR Good Research Practices for Conjoint Analysis Task Force. Value Health. 2011;14(4):403–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barboza JL, Talley NJ, Moshiree B. Current and emerging pharmacotherapeutic options for irritable bowel syndrome. Drugs. 2014;74(16):1849–1870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lexicomp. Oxycodone: drug information. 2020; https://www.uptodate.com/contents/oxycodone-drug-information#F204871. Accessed February 1, 2020.

- 29.Lexicomp. Dicyclomine (dicycloverine): drug information. 2020; https://www.uptodate.com/contents/dicyclomine-dicycloverine-drug-information. Accessed February 1, 2020.

- 30.Khanna R, MacDonald JK, Levesque BG. Peppermint oil for the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2014;48(6):505–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alammar N, Wang L, Saberi B, et al. The impact of peppermint oil on the irritable bowel syndrome: a meta-analysis of the pooled clinical data. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2019;19(1):21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cunningham CE, Deal K, Chen Y. Adaptive choice-based conjoint analysis: a new patient-centered approach to the assessment of health service preferences. Patient. 2010;3(4):257–273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Spiegel BM, Hays RD, Bolus R, et al. Development of the NIH Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) gastrointestinal symptom scales. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109(11):1804–1814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Orme BK. Getting started with conjoint analysis: strategies for product design and pricing research. Research Publishers; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277–1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hellström PM, Saito YA, Bytzer P, Tack J, Mueller-Lissner S, Chang L. Characteristics of acute pain attacks in patients with irritable bowel syndrome meeting Rome III criteria. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106(7):1299–1307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ridyard CH, Dawoud DM, Tuersley LV, Hughes DA. A systematic review of patients’ perspectives on the subcutaneous route of medication administration. Patient. 2016;9(4):281–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Weidmann E, Unger J, Blair S, Friesen C, Hart C, Cady R. An open-label study to assess changes in efficacy and satisfaction with migraine care when patients have access to multiple sumatriptan succinate formulations. Clin Ther. 2003;25(1):235–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kaniecki RG. Mixing sumatriptan: a prospective study of stratified care using multiple formulations. Headache. 2001;41(9):862–866. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gross ML, Kay J, Turner AM, Hallett K, Cleal AL, Hassani H. Sumatriptan in acute migraine using a novel cartridge system self-injector. United Kingdom Study Group. Headache. 1994;34(10):559–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cady RK, Aurora SK, Brandes JL, et al. Satisfaction with and confidence in needle-free subcutaneous sumatriptan in patients currently treated with triptans. Headache. 2011;51(8):1202–1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schiele JT, Quinzler R, Klimm H-D, Pruszydlo MG, Haefeli WE. Difficulties swallowing solid oral dosage forms in a general practice population: prevalence, causes, and relationship to dosage forms. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2013;69(4):937–948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Palsson OS, Whitehead WE, Van Tilburg MA, et al. Development and validation of the Rome IV diagnostic questionnaire for adults. Gastroenterology. 2016;150(6):1481–1491. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Van den Houte K, Carbone F, Pannemans J, et al. Prevalence and impact of self-reported irritable bowel symptoms in the general population. United European Gastroenterol J. 2019;7(2):307–315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sperber AD, Bangdiwala SI, Drossman DA, et al. Worldwide prevalence and burden of functional gastrointestinal disorders, results of Rome Foundation Global Study. Gastroenterology. 2021;160(1):99–114.e113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Palsson OS, Whitehead W, Törnblom H, Sperber AD, Simren M. Prevalence of Rome IV functional bowel disorders among adults in the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom. Gastroenterology. 2020;158(5):1262–1273.e1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nakov R, Dimitrova-Yurukova D, Snegarova V, et al. Prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome, functional dyspepsia and their overlap in Bulgaria: a population-based study. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2020;29(3):329–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kosako M, Akiho H, Miwa H, Kanazawa M, Fukudo S. Influence of the requirement for abdominal pain in the diagnosis of irritable bowel syndrome with constipation (IBS-C) under the Rome IV criteria using data from a large Japanese population-based internet survey. Biopsychosoc Med. 2018;12:18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Almario CV, Chey WD, Spiegel BMR. Increased risk of COVID-19 among users of proton pump inhibitors. Am J Gastroenterol. 2020;115(10):1707–1715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Oh SJ, Fuller G, Patel D, et al. Chronic constipation in the United States: results from a population-based survey assessing healthcare seeking and use of pharmacotherapy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2020;115(6):895–905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Krasaelap A, Sood MR, Li BUK, et al. Efficacy of auricular neurostimulation in adolescents with irritable bowel syndrome in a randomized, double-blind trial. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18(9):1987–1994.e1982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hetterich L, Stengel A. Psychotherapeutic interventions in irritable bowel syndrome. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

SUPPLEMENTARY FIGURE 1. Descriptions of each medication attribute shown to participants prior to the conjoint exercises to facilitate their understanding of each characteristic. Each panel was shown on a separate page.

SUPPLEMENTARY FIGURE 2. Description of a specific subcutaneous therapy for acute abdominal pain from irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) modeled after ROSE-010.

SUPPLEMENTARY FIGURE 3. Qualitative content analysis detailing what respondents would require of a subcutaneous therapy in order to consider using it for managing their acute abdominal pain from irritable bowel syndrome. The font sizes correspond to the prevalence.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, B.M.R.S, upon reasonable request.