Abstract

Congenital abnormalities of the uterus result primarily from embryological maldevelopment of the paramesonephric ducts and have been associated with pregnancy complications, reduced fertility, and other adverse fetal outcomes. While such abnormalities are rare, affected patients should be correctly managed to improve psychological, sexual, and reproductive outcomes. This review intends to elucidate the impact of congenital uterine abnormalities on fertility and pregnancy outcomes. We also present the available management methods and discuss the role of assisted reproductive technologies (ART) to benefit affected women. This review clearly shows that although these disorders are generally not lethal, they critically impact the patient’s reproductive health. The fertility rate of patients with uterine congenital abnormalities depends on the severity of the condition. Reproductive endocrinologists and infertility specialists must be considered as active parts of the interdisciplinary treatment team for such patients. ART practices are reasonably successful at managing fertility problems of women with these abnormalities.

Keywords: congenital abnormalities, uterus, fertility, reproductive technologies

INTRODUCTION

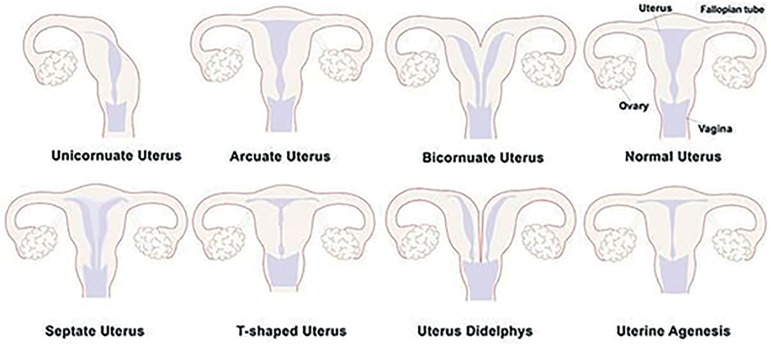

Congenital uterine abnormalities mainly result from embryological maldevelopment of the paramesonephric ducts and have been associated with pregnancy complications, reduced fertility and other adverse fetal outcomes (Mucowski et al., 2010; Nejatbakhsh et al., 2012; Parmar & Tomar, 2014). According to Saravelos et al. (2008), the prevalence of these abnormalities is 16% in women with recurrent miscarriages and 7.3% in infertile women. Congenital uterine abnormalities may also accompany other abnormalities, which may probably affect other organs and result in further complications (Hassan et al., 2010). The first classification of congenital uterine anomalies was introduced in 1979 (Devi Wold et al., 2006). In 1988, the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM) updated this classification (Figure 1) (Saravelos et al., 2008; Devi Wold et al., 2006).

Figure 1.

Schematic diagrams of uterine congenital malformations according to the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM). Based on the ASRM descriptions, malformations in the female genital tract occurred during embryogenesis that generally result from abnormal development of the Müllerian duct(s) are called uterine congenital malformations.

Unfortunately, there is limited number of literature regarding the medical management of the affected women and treatment options for infertile individuals. In this review, we discussed the fertility potential, chance of pregnancy, and pregnancy complications of patients with congenital uterine abnormalities. The potential roles of ART for treating infertility in these patients were also discussed. In general, ART procedures such as in vitro fertilization (IVF) and intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) are reasonably successful in managing fertility problems of women with these abnormalities.

EVIDENCE ACQUISITION

For data collection, published reports from the literature of the years 2000 to 2020 discussing congenital uterine malformations were searched in the PubMed database, using keywords “Congenital Malformations”, “Uterine”, “Fertility” and “Reproductive Technologies”. Eighty-eight articles were eventually selected and included in the review.

RESULTS

Class I: Müllerian agenesis

The Müllerian duct evolves to the vagina and uterus during embryogenesis, while the ovaries originate from a different embryonic source (Stanhiser & Attaran, 2016). Therefore, a deficiency in Müllerian duct development may result in an absent or shortened vagina, or an incomplete midline uterus or uterine horns with normal ovaries. (Folch et al., 2000). In this abnormality, the secondary sexual characteristic appears to be normal, but due to structural and probable functional defects of the uterus, patients are faced with fertility problems (Stanhiser & Attaran, 2016). Müllerian agenesis, also known as Mayer-Rokitansky-Kuster-Hauser (MRKH) syndrome, is the second most common cause of primary amenorrhea, with an incidence of 0.020-0.025% (Londra et al., 2015).

Gestational difficulties of females with MRKH syndrome are primarily managed with the aid of a gestational surrogate (Anchan et al., 2013; Raziel et al., 2012). IVF followed by embryo transfer to a gestational surrogate is an option for these patients, since the embryonic origin of the ovaries is separate from the tubes and uterus that provide normal oocytes which are hyper-responsive to stimuli, independent from the menses dating (Ben-Rafael et al., 1998; Cakmak & Rosen, 2015; Raziel et al., 2012). Oocyte retrieval efficiency, fertilization rates, embryo quality, and successful pregnancy rates are slightly below average for MRKH patients; however, trying IVF is still an attractive option to these patients (Folch et al., 2000; Pabuccu et al., 2011; Raziel et al., 2012). Because of the unique pelvic anatomy of MRKH patients, oocytes from these women should be preferably retrieved via the transabdominal rather than transvaginal route (Londra et al., 2015). Conventional hyperstimulation protocols, including ovarian hyperstimulation in these cases, have been recently used in a similar fashion to urgent oocyte cryopreservation performed for cancer patients (Bakhtiari et al., 2012; Ben-Rafael et al., 1998; Cakmak & Rosen, 2015). Following up on the health of children born from MRKH patients may be helpful to investigate possible related etiologies (Londra et al., 2015; Petrozza et al., 1997).

In the treatment protocol for this type of anomaly, correct and comprehensive diagnosis as well as psychosocial consultation are necessary, while laparoscopy is principally used in patients with pelvic pain (Folch et al., 2000). A new vagina can be created via surgical and nonsurgical approaches (Folch et al., 2000; Morcel et al., 2007).

Class II: Unicornuate uterus

In this type of anomaly, the development of the Müllerian duct is normal on one side, but on the other side the uterus shows a single horn, termed unicornuate or banana shaped uterus (Ozgur et al., 2017). Typically, the dominant side of the uterus has a healthy endometrial cavity (Saravelos et al., 2008). The natural horn develops from the intact paramesonephric duct, while in the abnormal side it originates from a hypoplastic paramesonephric duct and is categorized into four subtypes based on the extent of malformation (Dove et al., 2018; Saravelos et al., 2008). Different types of unicornuate uterus anomalies are: 1) complete unicornuate uterus lacking a second horn, 2) a primitive horn lacking endometrial cavity, 3) a primitive horn having an endometrial cavity isolated from the dominant uterine cavity, and 4) a primitive horn having the endometrial cavity, which is in contact with the dominant uterine cavity (Dove et al., 2018). According to the American Fertility Society, isolated rudimentary endometrial cavities are most often seen in cases of unicornuate uterus (Bodur et al., 2017). Ovarian development is typically not compromised, although the ovary on the affected side might be ectopic or even absent in rare cases (Reichman et al., 2009). Accidental renal abnormalities are common, and women with rudimentary horns are at increased risk of developing endometriosis or chronic pain because of hematometra (Fedele et al., 1987; Reichman et al., 2009).

The association between unicornuate uterus and infertility is less clear. A retrospective observational study including 3181 women reported that 23.7% of the patients with a unicornuate uterus were diagnosed with subfertility (Chen et al., 2018). Only one third of the pregnancies of patients with a unicornuate uterus ended with live births, while a significant portion (~50%) resulted in preterm delivery and 4% in ectopic pregnancy (Chan et al., 2011a). Single and multiple miscarriages and intrauterine fetal demise were prevalent in these patients (Reichman et al., 2009). The pathological mechanisms involved in such reproductive failures relate to pregnancy maintenance regulating procedures such as incompetent uterine and placental blood flow, uterine muscle insufficiency, and cervical weakness (Khati et al., 2012).

Cases of unicornuate uterus account for a significant portion of congenital uterine anomalies, with an incidence in the general population of about 0.1% (Agarwal et al., 2017; Ozgur et al., 2017). Unicornuate uterus is one of the main etiologies of infertility in the general population (Li et al., 2017). Surgery is not needed before IVF in such cases (Ludwin et al., 2011). According to the comparative study by Li et al. (2017), early pregnancy loss, premature delivery, and perinatal mortality in patients with a unicornuate uterus occurred much more frequently than in controls. The live birth rate after IVF-ET decreases in such patients, while the risk of premature delivery increases (Li et al., 2017). Ozgur et al. (2017) reviewed previously published data on the pregnancy, perinatal, and obstetric rates seen in patients with a unicornuate uterus after ICSI. Their retrospective study confirmed the observation of low pregnancy rates, low birth weight, high risk of miscarriage, premature birth, and stillbirth.

Ectopic pregnancies are also prevalent in women with a unicornuate uterus (Yoldemir, 2015). Very sporadically, pregnancy may occur within the non-communicating rudimentary horn (1 out of 76,000), with high risk of uterine rupture occurring mostly in the sixth month of pregnancy (Rackow & Arici, 2007). However, there are exceptional cases such as one of the twin fetuses reported by Nanda et al., which successfully grew in the non-communicating rudimentary horn of a unicornuate uterus (Caserta et al., 2014).

In spite of the odds, successful pregnancy and delivery are not impossible in women with a unicornuate uterus if the pregnancy is well monitored in terms of intrauterine growth retardation. Laparoscopy can be used in the excision of rudimentary horns in non-pregnant patients (Ben-Rafael et al., 1998).

Class III: Uterus didelphys

Uterine didelphys accounts for about 10% of uterine anomalies and 0.2% of cases of infertility (Al-Hussaini, 2017; Yang et al., 2015). Patients with the condition develop two uteri and two cervices and may have two vaginas in very few cases. This is a congenital malformation resulting from deficient embryonic lateral fusion of the two Müllerian ducts. It is mostly diagnosed during infertility workup or examination for recurrent miscarriage (Yang et al., 2015). The diagnosis of uterus didelphys is mostly incidental, since it is often asymptomatic. However, the presence of a vaginal septum may be associated with painful intercourse, menstruation, or abdominal pain as the vagina or the vagina and uterus are filled with menstrual blood (Park & Lee, 2013), in addition to occasional genital neoplasms and endometriosis (Heinonen, 2000; Rezai et al., 2015). The reproductive performance of patients with uterus didelphys is relatively less problematic compared to other more common Müllerian duct malformations such as septate or bicornuate uterus (Table 1) (Park & Lee, 2013; Rezai et al., 2015). However, women with this condition struggle with the risk of miscarriage, intrauterine growth retardation, and a high rate of preterm delivery with the lowest rate (<50%) of full-term pregnancy (Chan et al., 2011a; Raga et al., 1997). Consequently, fertility efficiency is considered weak and successful cases have been scarcely reported (Raga et al., 1997; Sanfilippo & Peticca, 2016). Although performed with a small population (40 women), a study by Heinonen (2000) found no significant difference in the fertility and miscarriage rates of patients with uterus didelphys, septate and bicornuate uteri. Published reports of twin and triplet pregnancies of women with uterus didelphys show the competence of one of the uteri in carrying healthy fetuses (Okafor et al., 2016; Nohara et al., 2003; Tuteja et al., 2015; Al Yaqoubi & Fatema, 2017). Nevertheless, increased rates of prematurity have been reported for women with uterus didelphys compared to individuals with other Müllerian duct anomalies (MDA) (Heinonen, 2000).

Table 1.

Pregnancy outcomes from different types of congenital uterine malformation.

| Study | Pregnancy outcome | Unicornuate n (%) |

Didelphys n (%) |

Arcuate n (%) |

Septate n (%) |

Bicornuate n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Michalas, 1991 | Spontaneous miscarriage | (5) | (8) | - | (19) | (14) |

| Raga et al., 1997 | Early miscarriage Ectopic pregnancy Preterm delivery |

6 (37.5) 0 4 (25.0) |

3 (20.0) 1 (6.6) 8 (53.3) |

14 (12.7) 3 (2.7) 5 (4.5) |

37 (25.5) 3 (2.1) 21 (14.5) |

14 (25.0) 0 14 (25.0) |

| Salim et al., 2003 | Recurrent miscarriage | 2 (0.4) | - | 86 (16.9) | 27 (5.3) | 6 (1.2) |

| Yassaee & Mostafaee, 2011 | Preterm delivery | - | - | 1 (33.3) | - | 8 (72.7) |

| Butt, 2011 | Miscarriage Ectopic pregnancy |

1(2.5) 1(2.5) |

1(2.5) 0 |

2(5) 1(2.5) |

2(5) 0 |

4(10) 0 |

| Bailey et al., 2015 | Recurrent pregnancy loss. | 6(0.7) | 2(0.2) | - | 43 (4.9) | 7(0.8) |

With all things considered, artificial reproductive technologies and embryo transfer may be occasionally helpful, such as in the case of a patient with a complete longitudinal vaginal septum described by Al-Hussaini (2017), who conceived twice after several failed ICSI attempts. Another case of IVF and embryo transfer involving a woman with uterus didelphys was reported by Yang et al. (2015) as having reached successful gestations. Since data on the precise frequency of reconstructive surgery for congenital anomaly repair (metroplasty) is not available, the ability to achieve pregnancy of women with uterus didelphys is not well understood. The vaginal septum, for example, should be removed in symptomatic uterus didelphys cases. However, a cesarean section is recommended whenever a thick and inelastic vaginal septum is present (Rezai et al., 2015). Having uterus didelphys does not necessarily correlate with cervical weakness. However, it has been recommended that patients with uterus didelphys be examined for renal anomalies to rule Herlyn-Werner-Wunderlich (HWW) syndrome out (Rezai et al., 2015). HWW is another infrequent congenital anomaly affecting the paramesonephric and mesonephric ducts characterized by uterus didelphys, obstructed hemivagina, and ipsilateral renal agenesis (Khaladkar et al., 2016).

Nevertheless, women with uterus didelphys can have healthy pregnancies using split embryo transfer in IVF/ICSI cycles with no need for cerclage. Hysteroscopy is a viable diagnostic tool to find horn embryos, which are better candidates to be replaced. It also helps to diagnose other abnormalities that might interfere with implantation, especially in cases of recurrent implantation failure (Al-Hussaini, 2017).

Class IV: Bicornuate uterus

Similar to uterus didelphys, bicornuate uterus derives from deficient fusion of Müllerian ducts during fetal development; in this case, the two cavities are entirely or partially unified by caudal fusion (Doruk et al., 2013). Both endometrial cavities frequently open to a single vagina via a single uterine cervix (unicollis) or via separate uterine cervices in rare cases (bicollis) (Chan et al., 2011b; Gasim & Al Jama, 2013; Nitzsche et al., 2017). Bicornuate uterus competes with arcuate uterus for the place of third most frequent congenital Müllerian malformation in unselected populations (0.4%) (Dohbit et al., 2017; Kowalik et al., 2011). It is often asymptomatic and remains unidentified before puberty, showing a significant correlation with infertility and miscarriage (Dohbit et al., 2017).

The rate of the Premature Rupture of Membranes (PROM), preterm separation of the placenta, miscarriage, premature delivery, and Intrauterine Growth Restriction (IUGR) is higher in cases of bicornuate uterus (Mastrolia et al., 2017). Bicornuate uterus significantly contributes to uterine ruptures in first pregnancy patients and at any gestational age (Nitzsche et al., 2017), as well as cervical incompetence, which can significantly increase the perception of birth risk (Mastrolia et al., 2017). However, there are several reports of successful gestations involving bicornuate uterus patients. Prognosis remains debatable, since pregnancy may be compromised by cervical atresia, cervical mucus absence, upper congenital anomalies, recurrence of the anomaly after cervical corrective surgery, and postoperative retrograde adhesions (Acién et al., 2008; Aimen et al., 2016; Deffarges et al., 2001; Radhouane et al., 2015).

Nevertheless, pregnancy may be possible after surgical corrections through natural or artificial insemination (Table 2). In a rare case, Li et al. (2016) reported a successful full-term twin pregnancy in each cavity of a bicorporeal septate uterus of a patient with two cervices and a longitudinal vaginal septum via natural insemination. Furthermore, a women with bicornuate unicollis uterus with twins successfully delivered at 35 weeks of gestation through a bilateral cesarean section (Doruk et al., 2013). In addition, several cases of successful pregnancies of women with a bicornuate uterus have been reported without surgical correction of the anomaly. A successful gestation in one of the horns in a women with a bicornuate uterus has been referenced by Adeyemi et al. (2013). To our knowledge, surgical corrections or IVF procedures have not been reported in women with a bicornuate uterus.

Table 2.

Reproductive performance according to the study by Prior et al. (2018) in women with congenital uterine malformations and women with normal uteri following assisted reproductive technology (ART) treatment. Live birth and clinical pregnancy rates were similar between the two groups, although preterm births were more common in women with uterine malformations than in controls.

| Normal uterus (n=1943) | Congenital uterine malformations (n=432) | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of retrieved oocytes | 12±7.6 | 12±6.5 | 0.75 | |

| Clinical pregnancy | 850 (44%) | 180 (42%) | 0.45 | |

| Preterm birth | <37 weeks | 102/722 (14%) | 33/152 (22%) | 0.026 |

| <34 weeks | 20/722 (3%) | 12/152 (8%) | 0.007 | |

| <32 weeks | 13/722 (2%) | 11/152 (7%) | 0.001 | |

| Live birth | 722 (37%) | 152 (35%) | 0.47 | |

Nevertheless, one cannot deby that pregnancies of women with Müllerian anomalies associate with potential obstetric complications. However, pregnancies in a bicornuate uterus have shown more favorable obstetric outcomes than pregnancies in patients with other Müllerian fusion disorders. Considering the rare occurrence of such cases and the potential contributing risks, pregnancies of women with a bicornuate uterus, and twin pregnancies in particular, should be managed carefully, in a tailored fashion (Doruk et al., 2013).

Class V: Septate uterus

This class of uterine anomalies constitutes the most frequent uterine malformation (35%), outranking before bicornuate uterus and arcuate uterus (Kowalik et al., 2011). The uterus of these patients is partitioned into two cavities because the midline septum has not been reabsorbed partially or entirely during fetal development (Kowalik et al., 2011; Valle & Ekpo, 2013). Therefore, the septum that begins from the uterine fundus may extend from before or after the internal cervical os (partial or complete uterine septum) to the external cervical os (complete uterine septum with septate cervix) or to the upper vagina (complete uterine septum with cervical and vaginal septations) (Valle & Ekpo, 2013).

Uterine septum anomaly increases the risk of obstetrical complications, recurrent miscarriage (Nouri et al., 2010), infertility (Nouri et al., 2010; Seet et al., 2015), preterm birth, fetal malpresentation, and miscarriage before six months (Seet et al., 2015), in addition to reducing the rate of clinical fertilization success (Table 1) (Chan et al., 2011a). Two mechanisms with suggested associations with spontaneous miscarriage are decreased septum vascular supply and an abnormal overlying endometrium, resulting in abnormal implantation (Ali et al., 2017; Freud et al., 2015). Müllerian malformations, including septate uterus, are among the several possible underlying causes of persistent decreased fetus movement. Repeated differential diagnostic evaluations are especially important when the fetus is diagnosed as healthy in examinations (Ali et al., 2017). A complete septate uterus may be confused with uterus didelphys, especially in the presence of a duplicated cervix and a longitudinal septum in the vagina (Patton et al., 2004).

The management of these anomalies is controversial; thus, proper diagnosis with the aid of different imaging resources - HSG, US, and Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) - is a key element in planning for surgical interventions (Patton et al., 2004; Seet et al., 2015). One of the interventions is hysteroscopic resection (HR) of the uterine septum, a procedure known to provide better reproductive outcomes in patients with a track record of spontaneous miscarriage or premature labors (Freud et al., 2015).

The possibilities offered by ART interventions to enhance the reproductive outcomes of patients with uterine septa have not been well documented. However, data from relative population studies showed that pregnancy and miscarriage outcomes of patients submitted to hysteroscopic septoplasty and IVF were similar to the outcomes of individuals with a normal uterine cavity (Abuzeid et al., 2014). In this regard, several studies showed that uterine septum HR might improve pregnancy and live birth rates while decreasing the risk of miscarriage in patients receiving IVF or ICSI workup (Ban-Frangez et al., 2009; Ozgur et al., 2007; Tomaževič et al., 2010). Therefore, hysteroscopic procedures may be considered in uterine anomaly repairs not only for women with recurrent pregnancy loss and preterm labor, but also for infertile women. This technique is a simple method with minimal postoperative sequelae that may improve reproductive outcomes, especially in cases where IVF is an option (Tomaževič et al., 2010). In such cases, it is important to make the best of every single chance of pregnancy, because of the adverse effects of multiple pregnancies on the possibility of taking pregnancies to full-term (Abuzeid et al., 2014).

Class VI: Arcuate uterus

This mild uterine anomaly sometimes considered normal is characterized by an arcuate uterus that produces little or no impact on reproductive outcomes (Fatema, 2011; Grimbizis et al., 2001). The uterine cavity is normally straight or pulvinate towards the fundus of the uterus, while in the arcuate uterus, the uterine cavity is curved against the fundus and the myometrium of the fundus is a bit extended toward the cavity, sometimes displaying a small septum (Mucowski et al., 2010; Mueller et al., 2007; Saravelos et al., 2008). In addition, differentiating an arcuate uterus from a septate uterus is still controversial, since the distinctions between them have not been standardized (Mucowski et al., 2010). The intrinsic mechanism that occurs during embryo development to result in an arcuate morphology is unknown. However, it has been suggested that it may be linked to partial septal resorption (Tomaževič et al., 2010).

Although an arcuate uterus scarcely requires treatment on account of its minimal association with poor reproductive outcomes (Fatema, 2011; Grimbizis et al., 2001), a few reports have described an association with increased risk of spontaneous miscarriage, preterm labor, and second-trimester pregnancy loss, which result in a marginal reduction in term delivery rates (Table 1) (Woelfer et al., 2001; Zlopasa et al., 2007). The mechanism underlying the occurrence of late pregnancy complications in arcuate uterus patients has not been elucidated (Lin, 2004; Mucowski et al., 2010).

Regarding reports on successful reproductive outcomes after HR, guidelines for arcuate anomaly management, including cases of recurrent pregnancy loss, have not been consolidated. HR may be prescribed to individuals with recurrent pregnancy loss without a distinguishable alternative etiology. However, there is no universally agreed method to treat individuals with an arcuate uterus. Nevertheless, hysteroscopic septoplasty may help patients with primary and secondary infertility and an arcuate uterus before they undergo infertility treatments such as IVF-ET (Abuzeid et al., 2014; Chan et al., 2011a).

A few studies discussed an association between arcuate anomaly and poor reproductive outcomes, although they included small populations and were affected by confounders and bias in case selections (Mucowski et al., 2010). These studies described recurrent pregnancy loss and low term delivery rates among patients with an arcuate anomaly, although other reports indicated improvements in term delivery rates and decreases in miscarriage rates (Abuzeid et al., 2014). These results were obtained with the aid of surgical repair (hysteroscopic septoplasty) (Abuzeid et al., 2014). Therefore, more longitudinal studies enrolling larger populations should be performed to acquire accurate data on the incidence of arcuate uterus and the associated pregnancy complications in the unselected population (Mucowski et al., 2010).

Class VII: T-shaped uterus

Women exposed to diethylstilbestrol (DES) in utero during fetal development may develop a uterine malformation referred to as T-shaped uterus. In non-exposed individuals, T-shaped uterus is a rare occurrence (Pui, 2004). DES hampers hormonal induction during embryo evolution (Golan et al., 1989; Pui, 2004); however, its exact role in infertility remains unknown (Lin et al., 2002). This anomaly is the only genital malformation which can be acquired as well (e.g., in Asherman syndrome) (Fernandez et al., 2011). Data on ART indicates that the T-shaped uterus anomaly has been associated with a remarkable decreases in pregnancy, implantation, and in term pregnancy rates, and with increased spontaneous miscarriage rates (SAB) (Lin, 2004; Lin et al., 2002). The pathogenesis of the T-shaped uterus anomaly and its exact etiology are unknown. Apparently, its reported impacts revolve around oocyte maturation, fertilization, cleavage, and embryo quality and development (Dehdehi et al., 2020; Lin et al., 2002; Rennell, 1979), leading to a history of primary infertility in patients, recurrent miscarriage, or preterm delivery (Fernandez et al., 2011). The side effects of DES appear to be limited to the uterus (Lin et al., 2002).

The endometrial cavity of the uterus in patients with a T-shaped uterus is thin and more easily identifiable by HSG compared to US or MRI (Pui, 2004). Failure to treat individuals with a T-shaped uterus has been linked to inferior reproductive outcomes, including failed implantation, increased risk of ectopic pregnancy, miscarriage, and preterm delivery (Berger & Goldstein, 1980; Fernandez et al., 2011; Katz et al., 1996). Few reports described hysteroscopic metroplasty for T-shaped uterus patients, although the procedure has been often performed for septate uterus patients (Fernandez et al., 2011). Therefore, hysteroscopic metroplasty may be considered as a beneficial approach to increase the live birth rates of T-shaped uterus patients; however, it does not treat infertility (Fernandez et al., 2011; Giacomucci et al., 2011).

CONCLUSION

This review clearly showed that congenital uterine malformations are related with poor reproductive outcomes. The exact impact is dependent on the type of anomaly and the outcome being considered. Modern clinical understanding and advanced imaging techniques allow more precise identification of congenital uterine malformations. As affected women approach childbearing age, the impact of their underlying condition on sexuality and reproductive potential assumes greater importance. It is therefore paramount for involved practitioners to be aware of the most up-to-date reproductive technologies and surgical interventions to optimally manage patients with these conditions. The present review provides the available necessary information for adequate patient counseling and treatment. Additionally, this review underscored the need for further longitudinal studies and prospective randomized trials to best define what treatments may be offered to this patient cohort.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors gratefully acknowledge Professor Norman Eizenberg from the University of Notre Dame, Melbourne VIC, Australia for comprehensive editing of the article.

Footnotes

Abbreviations

ART: Assisted Reproductive Technologies; ASRM: America Society for Reproductive Medicine; DES: Diethylstilbestrol; HR: Hysteroscopic Resection; HWW: Herlyn-Werner-Wunderlich Syndrome; ICSI: Intracytoplasmic Sperm Injection; IUGR: Intrauterine Growth Restriction; IVF: In Vitro Fertilization; IVF-ET: In Vitro Fertilization and Embryo Transfer; MDA: Müllerian Duct Anomaly; MRI: Magnetic Resonance Imaging; MRKH: Mayer-Rokitansky-Kuster-Hauser Syndrome; US: Ultrasonography; HSG: Hysterosalpingography; PROM: Premature Rupture of Membranes.

Authors’ contributions

Concept, format, revision, and editing: HH, YS; Literature search, extraction, and analysis: PY, FM, JK, BK, NA; Table and Figure PY, FM; manuscript drafting HH, JK, BK. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there are no competing interests related to the subject matter or materials discussed in this article.

Funding None.

REFERENCES

- Abuzeid M, Ghourab G, Abuzeid O, Mitwally M, Ashraf M, Diamond M. Reproductive outcome after IVF following hysteroscopic division of incomplete uterine septum/arcuate uterine anomaly in women with primary infertility. Facts Views Vis Obgyn. 2014;6:194–202. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acién P, Acién MI, Quereda F, Santoyo T. Cervicovaginal agenesis: spontaneous gestation at term after previous reimplantation of the uterine corpus in a neovagina: Case Report. Hum Reprod. 2008;23:548–553. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dem420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adeyemi AS, Atanda OO, Adekunle AD. Successful pregnancy in one horn of a bicornuate uterus. Ann Afr Med. 2013;12:252–254. doi: 10.4103/1596-3519.122696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal M, Sinha HH, Anamika Congenital absence of a part of the fallopian tube: a case report. Int J Reprod Contracept Obstet Gynecol. 2017;6:320–322. doi: 10.18203/2320-1770.ijrcog20164686. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aimen FM, Atef Y, Majed G, Radhouane A, Manel M, Monia M, Khaled N, Hedi R. Spontaneous pregnancy after vaginoplasty in a patient presenting a congenital vaginal aplasia. Asian Pac J Reprod. 2016;5:351–353. doi: 10.1016/j.apjr.2016.06.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Hussaini TK. Two successful pregnancies using split embryo transfer in a woman with uterus didelphys: A case report. Middle East Fertil Soc J. 2017;22:70–72. doi: 10.1016/j.mefs.2016.06.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Al Yaqoubi HN, Fatema N. Successful Vaginal Delivery of Naturally Conceived Dicavitary Twin in Didelphys Uterus: A Rare Reported Case. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol. 2017;2017:7279548–7279548. doi: 10.1155/2017/7279548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali E, Khan T, Khanam D. Decreased Foetal Movements Secondary to Uterine Septum: A Case Report and Proposed Algorithm of Management. J Clin Diagn Res. 2017;11:QD06–QD07. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2017/25833.10466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anchan RM, Missmer SA, Correia KF, Ginsburg ES. Gestational carriers: A viable alternative for women with medical contraindications to pregnancy. Open J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;3:24–31. doi: 10.4236/ojog.2013.35A2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey AP, Jaslow CR, Kutteh WH. Minimally invasive surgical options for congenital and acquired uterine factors associated with recurrent pregnancy loss. Womens Health (Lond) 2015;11:161–167. doi: 10.2217/WHE.14.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakhtiari M, Mansouri K, Sadeghi Y, Mostafaie A. Proliferation and differentiation potential of cryopreserved human skin-derived precursors. Cell Prolif. 2012;45:148–157. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2184.2011.00803.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ban-Frangez H, Tomazevic T, Virant-Klun I, Verdenik I, Ribic-Pucelj M, -Bokal EV. The outcome of singleton pregnancies after IVF/ICSI in women before and after hysteroscopic resection of a uterine septum compared to normal controls. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2009;146:184–187. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2008.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Rafael Z, Bar-Hava I, Levy T, Orvieto R. Simplifying ovulation induction for surrogacy in women with Mayer-Rokitansky-Kuster-Hauser syndrome. Hum Reprod. 1998;13:1470–1471. doi: 10.1093/humrep/13.6.1470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger MJ, Goldstein DP. Impaired reproductive performance in DES-exposed women. Obstet Gynecol. 1980;55:25–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodur S, Fidan U, Kinci MF, Karasahin KE. Unicornuate uterus with a rudimentary horn diagnosed at scheduled third Cesarean Section. Pak J Med Sci. 2017;33:779–781. doi: 10.12669/pjms.333.12409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butt F. Reproductive Outcome in Women with Congenital Uterine Anomalies. Annals KEMU. 2021;17:171–171. doi: 10.21649/akemu.v17i2.294. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cakmak H, Rosen MP. Random-start ovarian stimulation in patients with cancer. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2015;27:215–221. doi: 10.1097/GCO.0000000000000180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caserta D, Mallozzi M, Meldolesi C, Bianchi P, Moscarini M. Pregnancy in a unicornuate uterus: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2014;8:130–130. doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-8-130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan YY, Jayaprakasan K, Tan A, Thornton JG, Coomarasamy A, Raine-Fenning NJ. Reproductive outcomes in women with congenital uterine anomalies: a systematic review. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2011a;38:371–382. doi: 10.1002/uog.10056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan YY, Jayaprakasan K, Zamora J, Thornton JG, Raine-Fenning N, Coomarasamy A. The prevalence of congenital uterine anomalies in unselected and high-risk populations: a systematic review. Hum Reprod Update. 2011b;17:761–771. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmr028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Nisenblat V, Yang P, Zhang X, Ma C. Reproductive outcomes in women with unicornuate uterus undergoing in vitro fertilization: a nested case-control retrospective study. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2018;16:64–64. doi: 10.1186/s12958-018-0382-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deffarges JV, Haddad B, Musset R, Paniel BJ. Utero-vaginal anastomosis in women with uterine cervix atresia: long-term follow-up and reproductive performance. A study of 18 cases. Hum Reprod. 2001;16:1722–1725. doi: 10.1093/humrep/16.8.1722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehdehi L, Ghaffari Novin M, Sadeghi Y, Abdollahifar MA, Ziai SA, Nazarian H. Chronic Stress Diminishes the Oocyte Quality and In Vitro Embryonic Development in Maternally Separated Mice. Int J Womens Health Reprod Sci. 2020;8:29–36. 0.15296/ijwhr.2020.04. [Google Scholar]

- Devi Wold AS, Pham N, Arici A. Anatomic factors in recurrent pregnancy loss. Semin Reprod Med. 2006;24:25–32. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-931798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dohbit JS, Meka E, Tochie JN, Kamla I, Mwadjie D, Foumane P. A case report of bicornis bicollis uterus with unilateral cervical atresia: an unusual aetiology of chronic debilitating pelvic pain in a Cameroonian teenager. BMC Womens Health. 2017;17:39–39. doi: 10.1186/s12905-017-0396-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doruk A, Gozukara I, Burkaş G, Bilik E, Dilek TU. Spontaneous twin pregnancy in uterus bicornis unicollis. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol. 2013;2013:834952–834952. doi: 10.1155/2013/834952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dove CK, Harvey SM, Spalluto LB. Sonographic findings of early pregnancy in the rudimentary horn of a unicornuate uterus: A two case report. Clin Imaging. 2018;47:25–29. doi: 10.1016/j.clinimag.2017.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fatema K. A Case Report of Arcuate Uterus. Faridpur Med Coll J. 2011;6:107–109. doi: 10.3329/fmcj.v6i2.9213. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fedele L, Zamberletti D, Vercellini P, Dorta M, Candiani GB. Reproductive performance of women with unicornuate uterus. Fertil Steril. 1987;47:416–419. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(16)59047-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez H, Garbin O, Castaigne V, Gervaise A, Levaillant JM. Surgical approach to and reproductive outcome after surgical correction of a T-shaped uterus. Hum Reprod. 2011;26:1730–1734. doi: 10.1093/humrep/der056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folch M, Pigem I, Konje JC. Müllerian agenesis: etiology, diagnosis, and management. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2000;55:644–649. doi: 10.1097/00006254-200010000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freud A, Harlev A, Weintraub AY, Ohana E, Sheiner E. Reproductive outcomes following uterine septum resection. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2015;28:2141–2144. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2014.981746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasim T, Al Jama FE. Massive Hematometra due to Congenital Cervicovaginal Agenesis in an Adolescent Girl Treated by Hysterectomy: A Case Report. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol. 2013;2013:640214–640214. doi: 10.1155/2013/640214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giacomucci E, Bellavia E, Sandri F, Farina A, Scagliarini G. Term delivery rate after hysteroscopic metroplasty in patients with recurrent spontaneous abortion and T-shaped, arcuate and septate uterus. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2011;71:183–188. doi: 10.1159/000317266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golan A, Langer R, Bukovsky I, Caspi E. Congenital anomalies of the müllerian system. Fertil Steril. 1989;51:747–755. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(16)60660-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimbizis GF, Camus M, Tarlatzis BC, Bontis JN, Devroey P. Clinical implications of uterine malformations and hysteroscopic treatment results. Hum Reprod Update. 2001;7:161–174. doi: 10.1093/humupd/7.2.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassan MA, Lavery SA, Trew GH. Congenital uterine anomalies and their impact on fertility. Womens Health. 2010;6:443–461. doi: 10.2217/WHE.10.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinonen PK. Clinical implications of the didelphic uterus: long-term follow-up of 49 cases. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2000;91:183–190. doi: 10.1016/S0301-2115(99)00259-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz Z, Ben-Arie A, Lurie S, Manor M, Insler V. Beneficial effect of hysteroscopic metroplasty on the reproductive outcome in a ‘T-shaped’ uterus. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 1996;41:41–43. doi: 10.1159/000292033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khaladkar SM, Kamal V, Kamal A, Kondapavuluri SK. The Herlyn-Werner-Wunderlich Syndrome - A Case Report with Radiological Review. Pol J Radiol. 2016;81:395–400. doi: 10.12659/PJR.897228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khati NJ, Frazier AA, Brindle KA. The unicornuate uterus and its variants: clinical presentation, imaging findings, and associated complications. J Ultrasound Med. 2012;31:319–331. doi: 10.7863/jum.2012.31.2.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowalik CR, Goddijn M, Emanuel MH, Bongers MY, Spinder T, de Kruif JH, Mol BW, Heineman MJ. Metroplasty versus expectant management for women with recurrent miscarriage and a septate uterus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(6):CD008576–CD008576. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008576.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Yang L, Tian Y, Li D, Luo S. Successful term delivery of spontaneous twin pregnancy in a woman with bicorporeal septate uterus: A case report. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2016;42:1029–1033. doi: 10.1111/jog.13015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Ouyang Y, Yi Y, Lin G, Lu G, Gong F. Pregnancy outcomes of women with a congenital unicornuate uterus after IVF-embryo transfer. Reprod Biomed Online. 2017;35:583–591. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2017.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin PC, Bhatnagar KP, Nettleton GS, Nakajima ST. Female genital anomalies affecting reproduction. Fertil Steril. 2002;78:899–915. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(02)03368-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin PC. Reproductive outcomes in women with uterine anomalies. J Womens Health. 2004;13:33–39. doi: 10.1089/154099904322836438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Londra L, Chuong FS, Kolp L. Mayer-Rokitansky-Kuster-Hauser syndrome: a review. Int J Womens Health. 2015;7:865–870. doi: 10.2147/IJWH.S75637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludwin A, Ludwin I, Banas T, Knafel A, Miedzyblocki M, Basta A. Diagnostic accuracy of sonohysterography, hysterosalpingography and diagnostic hysteroscopy in diagnosis of arcuate, septate and bicornuate uterus. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2011;37:178–186. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0756.2010.01304.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mastrolia SA, Baumfeld Y, Hershkovitz R, Loverro G, Di Naro E, Yohai D, Schwarzman P, Weintraub AY. Bicornuate uterus is an independent risk factor for cervical os insufficiency: A retrospective population based cohort study. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2017;30:2705–2710. doi: 10.1080/14767058.2016.1261396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michalas SP. Outcome of pregnancy in women with uterine malformation: evaluation of 62 cases. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1991;35:215–219. doi: 10.1016/0020-7292(91)90288-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morcel K, Camborieux L, Programme de Recherches sur les Aplasies Müllériennes. Guerrier D. Mayer-Rokitansky-Küster-Hauser (MRKH) syndrome. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2007;2:13–13. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-2-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mucowski SJ, Herndon CN, Rosen MP. The arcuate uterine anomaly: a critical appraisal of its diagnostic and clinical relevance. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2010;65:449–454. doi: 10.1097/OGX.0b013e3181efb0db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller GC, Hussain HK, Smith YR, Quint EH, Carlos RC, Johnson TD, DeLancey JO. Müllerian duct anomalies: comparison of MRI diagnosis and clinical diagnosis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2007;189:1294–1302. doi: 10.2214/AJR.07.2494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nejatbakhsh R, Kabir-Salmani M, Dimitriadis E, Hosseini A, Taheripanah R, Sadeghi Y, Akimoto Y, Iwashita M. Subcellular localization of L-selectin ligand in the endometrium implies a novel function for pinopodes in endometrial receptivity. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2012;10:46–46. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-10-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nitzsche B, Dwiggins M, Catt S. Uterine rupture in a primigravid patient with an unscarred bicornuate uterus at term. Case Rep Womens Health. 2017;15:1–2. doi: 10.1016/j.crwh.2017.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nohara M, Nakayama M, Masamoto H, Nakazato K, Sakumoto K, Kanazawa K. Twin pregnancy in each half of a uterus didelphys with a delivery interval of 66 days. BJOG. 2003;110:331–332. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-0528.2003.01173.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nouri K, Ott J, Huber JC, Fischer EM, Stögbauer L, Tempfer CB. Reproductive outcome after hysteroscopic septoplasty in patients with septate uterus--a retrospective cohort study and systematic review of the literature. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2010;8:52–52. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-8-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okafor II, Odugu BU, Ugwu IA, Oko DS, Onyekpa IJ, Enyinna PK, Nevo CO, Ede JA. Undiagnosed Uterus Didelphys in a Term Pregnancy with Adverse Fetal Outcome: A Case Report. Divers Equal Health Care. 2016;13:177–179. [Google Scholar]

- Ozgur K, Isikoglu M, Donmez L, Oehninger S. Is hysteroscopic correction of an incomplete uterine septum justified prior to IVF? Reprod Biomed Online. 2007;14:335–340. doi: 10.1016/S1472-6483(10)60876-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozgur K, Bulut H, Berkkanoglu M, Coetzee K. Reproductive outcomes of IVF patients with unicornuate uteri. Reprod Biomed Online. 2017;34:312–318. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2016.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pabuccu E, Kahraman K, Taskın S, Atabekoglu C. Unilateral absence of fallopian tube and ovary in an infertile patient. Fertil Steril. 2011;96:e55–e57. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park TC, Lee HJ. Pregnancy coexisting with uterus didelphys with a blind hemivagina complicated by pyocolpos due to Pediococcus infection: a case report and review of the published reports. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2013;39:1276–1279. doi: 10.1111/jog.12049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parmar M, Tomar S. Bicornuate Uterus: Infertility Treatment and Pregnancy Continuation without Cerclage: An Unusual Case. Open J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;4:981–985. doi: 10.4236/ojog.2014.415138. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Patton PE, Novy MJ, Lee DM, Hickok LR. The diagnosis and reproductive outcome after surgical treatment of the complete septate uterus, duplicated cervix and vaginal septum. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190:1669–1675. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.02.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrozza JC, Gray MR, Davis AJ, Reindollar RH. Congenital absence of the uterus and vagina is not commonly transmitted as a dominant genetic trait: outcomes of surrogate pregnancies. Fertil Steril. 1997;67:387–389. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(97)81927-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prior M, Richardson A, Asif S, Polanski L, Parris-Larkin M, Chandler J, Fogg L, Jassal P, Thornton JG, Raine-Fenning NJ. Outcome of assisted reproduction in women with congenital uterine anomalies: a prospective observational study. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2018;51:110–117. doi: 10.1002/uog.18935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pui MH. Imaging diagnosis of congenital uterine malformation. Comput Med Imaging Graph. 2004;28:425–433. doi: 10.1016/j.compmedimag.2004.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rackow BW, Arici A. Reproductive performance of women with müllerian anomalies. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2007;19:229–237. doi: 10.1097/GCO.0b013e32814b0649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radhouane A, Mohamed B, Imen BA, Aymen F, Khaled N. Successful pregnancy by IVF in a patient with congenital cervical atresia. Asian Pac J Reprod. 2015;4:249–250. doi: 10.1016/j.apjr.2015.05.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Raga F, Bauset C, Remohi J, Bonilla-Musoles F, Simón C, Pellicer A. Reproductive impact of congenital Müllerian anomalies. Hum Reprod. 1997;12:2277–2281. doi: 10.1093/humrep/12.10.2277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raziel A, Friedler S, Gidoni Y, Ben Ami I, Strassburger D, Ron-El R. Surrogate in vitro fertilization outcome in typical and atypical forms of Mayer-Rokitansky-Kuster-Hauser syndrome. Hum Reprod. 2012;27:126–130. doi: 10.1093/humrep/der356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichman D, Laufer MR, Robinson BK. Pregnancy outcomes in unicornuate uteri: a review. Fertil Steril. 2009;91:1886–1894. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.02.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rennell CL. T-shaped uterus in diethylstilbestrol (DES) exposure. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1979;132:979–980. doi: 10.2214/ajr.132.6.979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rezai S, Bisram P, Lora Alcantara I, Upadhyay R, Lara C, Elmadjian M. Didelphys Uterus: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol. 2015;2015:865821–865821. doi: 10.1155/2015/865821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salim R, Regan L, Woelfer B, Backos M, Jurkovic D. A comparative study of the morphology of congenital uterine anomalies in women with and without a history of recurrent first trimester miscarriage. Hum Reprod. 2003;18:162–166. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deg030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanfilippo JS, Peticca K. In: Congenital Müllerian Anomalies - Diagnosis and Management. Pfeifer SM, editor. Cham: Springer; 2016. Uterus Didelphys: Diagnosis, Treatment, and Impact on Fertility and Reproduction; pp. 105–109. [Google Scholar]

- Saravelos SH, Cocksedge KA, Li TC. Hum Reprod Update. 2008;14:415–429. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmn018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seet MJ, Lau MS, Chan JK, Tan HH. Management of complete vagino-uterine septum in patients seeking fertility: report of two cases and review of literature. Gynecol Minim Invasive Ther. 2015;4:140–145. doi: 10.1016/j.gmit.2015.06.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stanhiser J, Attaran M. In: Congenital Müllerian Anomalies - Diagnosis and Management. Pfeifer SM, editor. Cham: Springer; 2016. Müllerian Agenesis: Diagnosis, Treatment, and Future Fertility; pp. 65–78. [Google Scholar]

- Tomaževič T, Ban-Frangež H, Virant-Klun I, Verdenik I, Požlep B, Vrtačnik-Bokal E. Septate, subseptate and arcuate uterus decrease pregnancy and live birth rates in IVF/ICSI. Reprod Biomed Online. 2010;21:700–705. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2010.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuteja TV, Bendre KR, Niyogi G. A rare case of uterus didelphys with full term pregnancy in left horn. Int J Reprod Contracept Obstet Gynecol. 2015;4:275–276. doi: 10.5455/2320-1770.ijrcog20150255. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Valle RF, Ekpo GE. Hysteroscopic metroplasty for the septate uterus: review and meta-analysis. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2013;20:22–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2012.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woelfer B, Salim R, Banerjee S, Elson J, Regan L, Jurkovic D. Reproductive outcomes in women with congenital uterine anomalies detected by three-dimensional ultrasound screening. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;98:1099–1103. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(01)01599-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang MJ, Tseng JY, Chen CY, Li HY. Delivery of double singleton pregnancies in a woman with a double uterus, double cervix, and complete septate vagina. J Chin Med Assoc. 2015;78:746–748. doi: 10.1016/j.jcma.2015.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yassaee F, Mostafaee L. The role of cervical cerclage in pregnancy outcome in women with uterine anomaly. J Reprod Infertil. 2011;12:277–279. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoldemir T. Rupture of a rudimentary uterine horn at the 19th week of pregancy subsequent to an earlier normal vaginal delivery. Marmara Med J. 2015;28:109–111. doi: 10.5472/MMJcr.2802.09. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zlopasa G, Skrablin S, Kalafatić D, Banović V, Lesin J. Uterine anomalies and pregnancy outcome following resectoscope metroplasty. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2007;98:129–133. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2007.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]