Abstract

Objective

The widespread deployment of electronic health records (EHRs) has introduced new sources of error and inefficiencies to the process of ordering medications in the hospital setting. Existing work identifies orders that require pharmacy intervention by comparing them to a patient’s medical records. In this work, we develop a machine learning model for identifying medication orders requiring intervention using only provider behavior and other contextual features that may reflect these new sources of inefficiencies.

Materials and Methods

Data on providers’ actions in the EHR system and pharmacy orders were collected over a 2-week period in a major metropolitan hospital system. A classification model was then built to identify orders requiring pharmacist intervention. We tune the model to the context in which it would be deployed and evaluate global and local feature importance.

Results

The resultant model had an area under the receiver-operator characteristic curve of 0.91 and an area under the precision-recall curve of 0.44.

Conclusions

Providers’ actions can serve as useful predictors in identifying medication orders that require pharmacy intervention. Careful model tuning for the clinical context in which the model is deployed can help to create an effective tool for improving health outcomes without using sensitive patient data.

Keywords: electronic health records, prescribing errors, medical order entry systems, machine learning

INTRODUCTION

Significant amounts of heterogeneous data from electronic health record (EHR) platforms have led to a surge in interest in using machine learning in clinical decision support (CDS) tools.1 This has resulted in the development of tools that provide clinicians with information which, when embedded at the appropriate point in their workflows, can improve healthcare.2–5 CDS tools encompass a variety of systems that can assist in the interpretation, diagnosis, and treatment of patients through the use of various tools, including alerts and reminders, clinical guidelines, recommendations, order sets, patient data reports and dashboards, documentation templates, diagnostic support, and other clinical workflow tools.3,4

One interesting application area lies in detecting medication order errors.6 Medical errors (including invasive procedures and hospital-acquired infections as well as those involving drugs and medical devices) are a significant public health problem and a leading cause of death.7 For medication order errors, manual review of incoming pharmacy orders is the “gold standard”8 for improving the use of medications and minimizing prescribing errors,8,9 though a series of recent studies have shown that pharmacies in both inpatient and outpatient settings are often understaffed.10–13 As a result, pharmacists experience a high degree of burnout10 and are at higher risk of making errors or not detecting problems with incoming orders. Supporting clinical pharmacists with CDS tools could therefore improve health outcomes for patients and effectively help pharmacists in under-resourced institutions to manage the load of detecting and correcting orders requiring intervention.

The widespread deployment of computerized physician order entry systems is believed to have resulted in significant declines in traditional sources of medication order errors.5,14,15 Recent research, however, has suggested ways in which these tools may have introduced or contributed to other sources of error (eg, alert fatigue, orders in the wrong medical records, etc.).14,16,17 These types of errors tend to fall into 2 categories:18 (1) errors in the process of entering and retrieving information (eg, interfaces that are not suitable for a highly interruptive use context, that produce cognitive overload by requiring structured information entry, that fragment information onto different screens, and that overemphasize information about a patient that is not useful), or (2) errors that come from a mismatch between the structured communication and coordination processes embedded in digital systems relative to the highly flexible and fluid ways in which clinical work happens in reality.

Prior work has centered on comparing the order to the patient’s medical records and omits features representing provider behavior. For example, Corny et al8 evaluate orders in the medical context of the individual patient’s laboratory reports, demographics, medical and allergy history, and physiological data. Similarly, Segal et al19 screen patients’ medical records and corresponding orders to identify time-dependent irregularities, clinical outliers, dosage outliers, and drug overlaps that might be indicative of medication order errors. Nguyen et al20 use an alternative approach in which patient information is used to identify those who are at high risk of receiving an inappropriate therapeutic and to prioritize review of orders made on their behalf.

These approaches may be missing critical signals from the provider’s suboptimal interactions with the EHR leading up to the submission of an order, and therefore entire “phenotypes” of errors. In this paper, we develop a predictive model for flagging orders requiring intervention using only information about the ordering provider’s interaction with the EHR. The model is then tuned and evaluated within the clinical context in which it would be deployed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Setting

This work was conducted within a large urban academic hospital system comprised of 3 hospitals (a quarternary care, a tertiary care, and an orthopedic subspecialty hospital) with over 1600 beds (combined) and numerous satellite locations.

Pharmacy orders were submitted via the electronic medications management system, EPIC. Auto-verification was implemented only for dietary supplements. Interventions were made by pharmacists in a main dispensing pharmacy or unit-based satellites, as well as by clinical pharmacists that rounded directly with the medical teams in certain specialty areas. A more comprehensive break-down of order intervention types can be found in supplementary materials. The frequency of each type of clinical intervention may vary in different functional areas. For example, a pharmacist rounding with a medical team is more likely to see patient-specific details and optimize a medication therapy plan to improve patient tolerance. Alternatively, a pharmacist dispensing medications from the pharmacy may not have access to as many patient-specific details, but may intervene on general medication issues (eg, reviewing medication dose, checking for appropriateness given patient renal function/age/weight, advising of allergy risk). There may also be variability in the documentation of interventions between pharmacists and at times of increased workload; however, supervision of clinical pharmacists and review of interventions by supervisors find a high rate of adherence to the expected workflow.

Analysis

Data

This study relies on inpatient data from July 10 through July 24, 2017. The dataset included a total of 181 407 individual orders submitted by 2708 providers. On average, providers submit 4.96 orders at once. We therefore consolidated orders made simultaneously into 36 585 order “batches.” Of these, 2054 (5.61%) contained at least one order that required intervention. The sample is described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Description of sample used

| Type | Inpatient |

|---|---|

| Dates | July 10–24, 2017 |

| No. of orders | 181 407 |

| No. of order batches | 38 966 |

| No. of order batches requiring intervention | 2054 (5.61%) |

| No. of providers | 2708 |

| No. of departments | 183 |

| No. of therapeutic classes | 45 |

| No. of patients | 16 714 |

Feature construction

Model features were determined using descriptive analysis and clinical expertise. Conversations with clinician informants revealed that they experience high administrative workload and a high degree of disruption and fragmentation in their workflows. This can tax working memory, which acts as a temporary storage for task-relevant information (often in the face of distractions).21–23 This is consistent with prior research14,17 and informed our selection of 17 features (continuous features described in Table 2).

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics of continuous features included in the model

| Feature | Mean |

Median | Std. Dev. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of administrative actions in hour preceding order | 15.42 | 2 | 29.62 | |

| No. of administrative actions in patient files in hour preceding order | 30.26 | 7 | 46.30 | |

| No. of orders in batch | 3.09 | 2 | 3.22 | |

| No. of ordersets in batch | 0.05 | 0 | 0.44 | |

| No. of actions related to patient encounters in hour preceding order | 49.65 | 8 | 79.81 | |

| No. of patients in batch | 1.07 | 1 | 0.31 | |

| No. of reconciliations in batch | 1.23 | 0 | 3.96 | |

| No. of STAT orders in batch | 0.68 | 0 | 1.80 | |

| No. of unique patient encounters in hour preceding order | 3.63 | 1 | 5.70 | |

| No. of unique workstations | 1.62 | 1 | 1.06 | |

-

Measures of clinician engagement with patients and the EHR in the hour preceding the order. These features capture behaviors that may require the provider to store more information in working memory22,23 (eg, seeing many patients in a short period of time), or periods in which a provider is multitasking or their workflow is disrupted (eg, needing to communicate information about a patient to a colleague while engaged with a different patient).24 Interruptions and multitasking increase the demands on working memory by requiring them to process information unrelated to their primary task, increasing the potential for error.21,25

Number of patient encounters.

Number of workstations accessed by a provider.

Number of general administrative actions the provider engaged in the EHR (eg, reviewing a patient list, checking messages, using the chat tool).

Number of administrative actions in a patient’s EHR (eg, reviewing a prior patient’s history) outside of the current patient encounter.

Number of administrative actions in the EHR related to a specific patient during an in-person visit (eg, reviewing their chart).

-

Details of the orders contained in the order batch. Creating orders is one of the more complex parts of the order-prescribing task21 and taxes a provider’s working memory (eg, when choosing clinical elements for an order), particularly when they are being made for multiple patients. This is especially true when the provider is disrupted or distracted as they are placing the order, increasing the probability of making an error or suboptimal order.

Number of orders in batch (submitted at once).

Number of orders in a batch using a predefined order template called ordersets.

Number of medications in a batch which are reorders of a prior medication order, called reorders.

Number of orders in a batch intended to keep a patient’s medications up-to-date, commonly from old or outdated prescriptions, when the patient’s care is transferred from one context to another (eg, when transferred from the ambulatory context to the inpatient context or from one team in the hospital to another), called reconciliations.

Number of time-sensitive (“STAT”) orders in a batch.

Number of patients for whom orders within a batch are being made.

-

Contextual data related to the clinician and the order. The context in which orders are made may influence providers’ behavior; for example, clinicians in certain specialties (eg, Emergency Department) may experience higher levels of cognitive load. We include the following contextual features:

Ordering clinician type (eg, Nurse Practitioner, Resident)

Ordering clinician specialty (eg, Emergency Medicine, Oncology)

Day of the week

Time of day (eg, early morning, late morning)

Hospital

Order therapeutic class (eg, Antivirals, Antibiotics)

Machine learning model

The model was designed as a binary classification task where the target labels corresponded to whether an order batch required intervention.

The data were split randomly into 70%, 15%, and 15% sets for model training, validation, and testing, respectively. Logistic regression with L1 and L2 regularization was used as baselines, and gradient-boosted trees (XGBoost) were employed as our focal ML algorithm. Cross-validation was used to identify the λ penalty in the regressions with regularization where the value selected gives the simplest model but also lies within one standard error of the optimal value of lambda (λ = 0.013 and λ = 0.28, respectively).

The XGBoost model was implemented with nested 5-fold cross-validation with early stopping (maximum of 50 rounds). Grid search was used to tune model hyperparameters, resulting in a maximum tree depth = 7, minimum child weight = 1, subsampling = 0.84, evaluation metric = auc, eta = 0.17, and gamma = 0.32. The validation set was used to monitor the model training through early stopping to evaluate the model performance and the effectiveness of the decision boundary; the test set was then used to evaluate the generalizability of the trained model. Due to a significant class imbalance in the training data (5.53% of batches required intervention), synthetic minority oversampling technique (SMOTE) was used to generate a pseudosynthetic training set with 5672 order batches in which 2836 (50%) required intervention.

RESULTS

The XGBoost algorithm outperformed both of the logistic regressions as well as the random forest algorithm by a significant margin in both area under the receiver-operator (AUROC) and precision-recall (AUPR) curves (Table 3). This indicates complex and nonlinear relationships between predictors that are not captured by linear classifiers or simple decision trees.

Table 3.

Model performance metrics for baseline (Lasso, Ridge, and Random Forest regression) and focal models (XGBoost)

| Model | AUROC | AUPR |

|---|---|---|

| Logistic regression with L1 (Lasso) regularization | 0.528 | 0.276 |

| Logistic regression with L2 (Ridge) regularization | 0.530 | 0.278 |

| Random forest with pruning | 0.579 | 0.180 |

| Extreme gradient-boosted trees (XGBoost) | 0.908 | 0.439 |

AUPR: area under the precision-recall; AUROC: area under the receiver-operator.

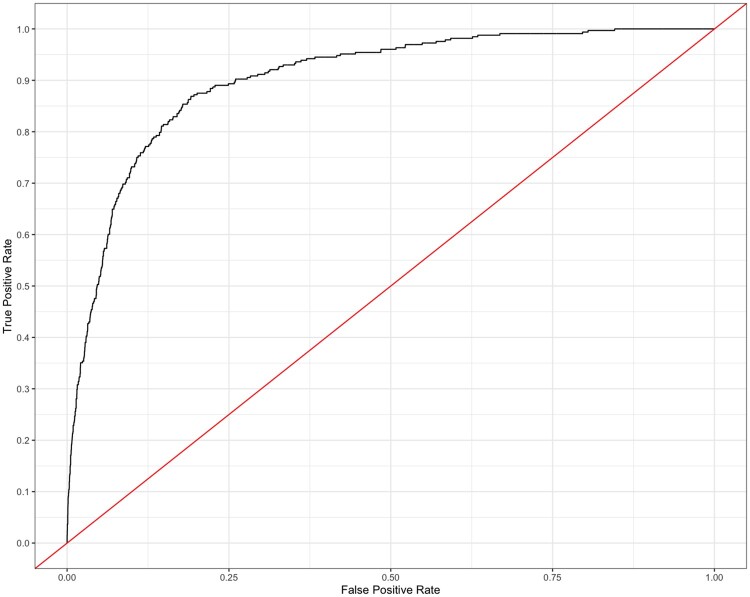

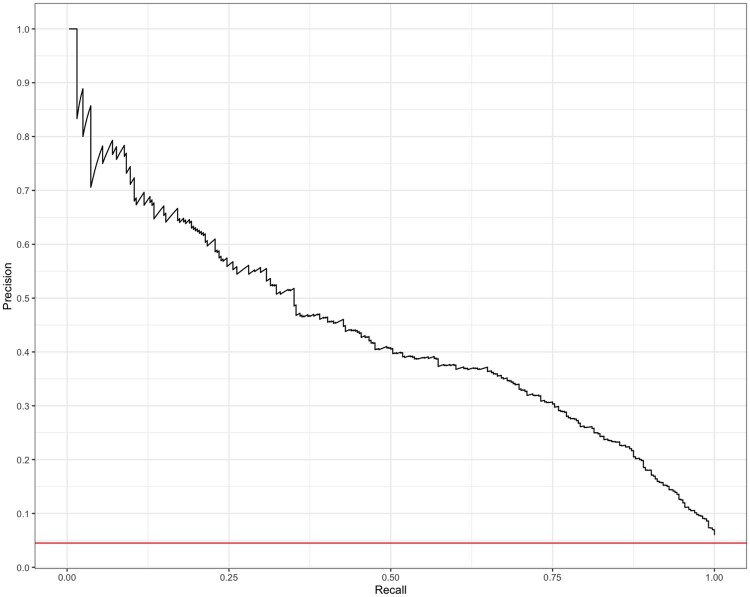

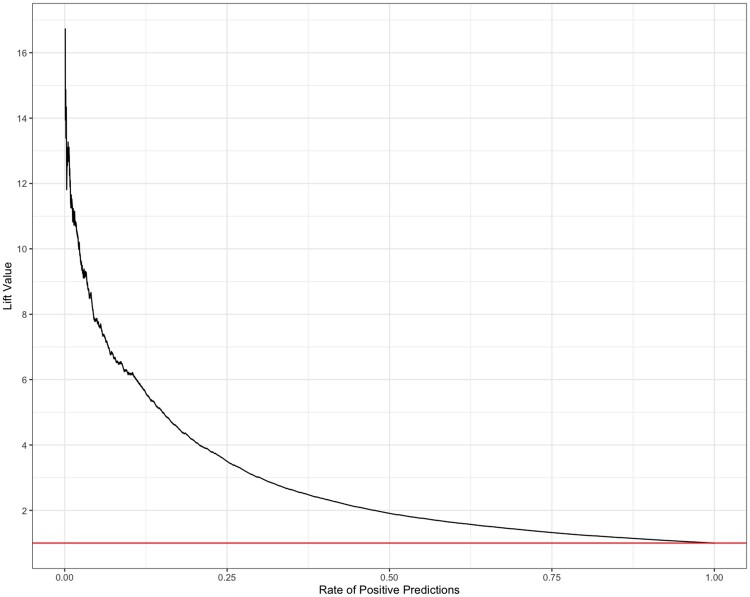

The trained XGBoost model had an AUROC of 0.908 (Figure 1); however, the high AUROC performance is likely a result of the imbalanced data set. In this case, the precision-recall curve can offer us a more accurate representation of model performance (visualized in Figure 2). The AUPR curve is 0.439. The resultant Lift curve shows that flagging a small fraction of orders for review results in the detection of a large number of the orders that required intervention (eg, selecting the top 20% of orders according to the model results in approximately 4 times the total number of orders requiring intervention being identified). This is visualized in Figure 3.

Figure 1.

Average receiver-operator characteristic (ROC) curve. AUROC is 0.908. AUROC: area under the receiver-operator curve.

Figure 2.

Precision-recall curve. AUPR is 0.439. AUPR: area under the precision-recall.

Figure 3.

Lift curve.

The choice of decision boundary will influence the performance of the model in the context of the clinical workflow. We therefore want to consider constraints on model error that exist at different stages in the workflow, then evaluate the model performance within the context of each of these stages. The hospital system on which this analysis is centered follows a well-established, digitally mediated process for prescribing and dispensing medications in the inpatient setting that involves the verification of all orders that are placed by clinicians to the pharmacy. Based on this workflow, we evaluate the model at 2 potential points:

Intervene at the point of order submission by the clinician. For example, alerting the clinician at the time of order entry that it may contain an error or require optimization. In this scenario, a high number of incorrectly flagged orders (false positives) could become burdensome and lead the provider to distrust or disregard the system.26–28 Within these constraints the precision rate should be relatively high, but the precision-recall curve for our model (Figure 1) suggests that this model may not adequately minimize both false positives and false negatives (AUPR= 0.439); we therefore consider the alternative.

Intervene at the point of order receipt by the pharmacist. For example, by removing the requirement for pharmacist verification on incoming orders that the model has identified as having a low risk of requiring an intervention. Clinical pharmacists currently review incoming orders assuming equal probability of requiring an intervention. Their order verification queue could be reduced by deprioritizing these orders. An intervention targeting pharmacists therefore has a requirement for a low false-negative rate, but pharmacists can likely tolerate a higher rate of false positives (relative to prescribing clinicians) because they already review a large number of orders that do not require intervention in the current workflow so any reduction in this workload is an improvement.

In light of this, we compute the classification threshold for the model that optimizes for model recall performance using the F10 score (0.076). Table 4a displays the corresponding confusion matrix and other model performance metrics.

Table 4.

Confusion matrix associated with decision boundaries displayed on the left side of the double lines in the table, and the corresponding model performance metrics are displayed on the right

| (a) | Actual | Model performance metrics | |||||

|

| |||||||

| Decision boundary = 0.076 | Intervention | No intervention | Accuracy | Recall | Specificity | Precision | |

| Prediction | Intervention | 312 | 3241 | 0.41 | 0.99 | 0.37 | 0.09 |

| No intervention | 2 | 1933 | |||||

|

| |||||||

| (b) | Actual | Model performance metrics | |||||

|

| |||||||

| Decision boundary = 0.5 | Intervention | No intervention | Accuracy | Recall | Specificity | Precision | |

| Prediction | Intervention | 242 | 606 | 0.88 | 0.77 | 0.88 | 0.29 |

| No intervention | 72 | 4568 | |||||

|

| |||||||

| (c) | Actual | Model performance metrics | |||||

|

| |||||||

| Decision boundary = 0.83 | Intervention | No intervention | Accuracy | Recall | Specificity | Precision | |

| Prediction | Intervention | 130 | 120 | 0.94 | 0.41 | 0.98 | 0.52 |

| No intervention | 184 | 5054 | |||||

Displays model performance associated with the selected decision boundary (0.076);

Displays the model performance with a decision boundary of 0.5; and

Displays the model performance with a decision boundary of 0.83.

Though the model accuracy is only 0.41, it has a sensitivity of 0.99 and specificity of 0.37 on the test set. The associated confusion matrix shows a very low number of false negatives (2) when deprioritizing 35% (1933 + 2) of orders identified by the model as not requiring intervention.

To demonstrate how alternative thresholds would perform consider (a) 0.5 and (b) 0.83 (model performance metrics in Table 4b and c). The model performance metrics associated with threshold (a) (Table 4a) show an accuracy and specificity rate of 0.88. This is a significant increase in specificity compared with the selected threshold (0.37) and corresponds to a substantial decrease in false positives (from 3241 to 606 with threshold [b]). However, the number of false negatives increases from 2 to 72, corresponding to a decrease in sensitivity from 0.99 to 0.77 with threshold (b). These trends continue when the decision boundary is increased to 0.83 (Table 4c). Though the percentage of orders that can be deprioritized increases from 85% (with threshold [a]) to 95% (with threshold [b]), there is a simultaneous and substantial increase in false negatives (the number of errors that are incorrectly labeled as not requiring intervention)—well beyond what we have identified as an acceptable rate of missing errors (maximum 5%).

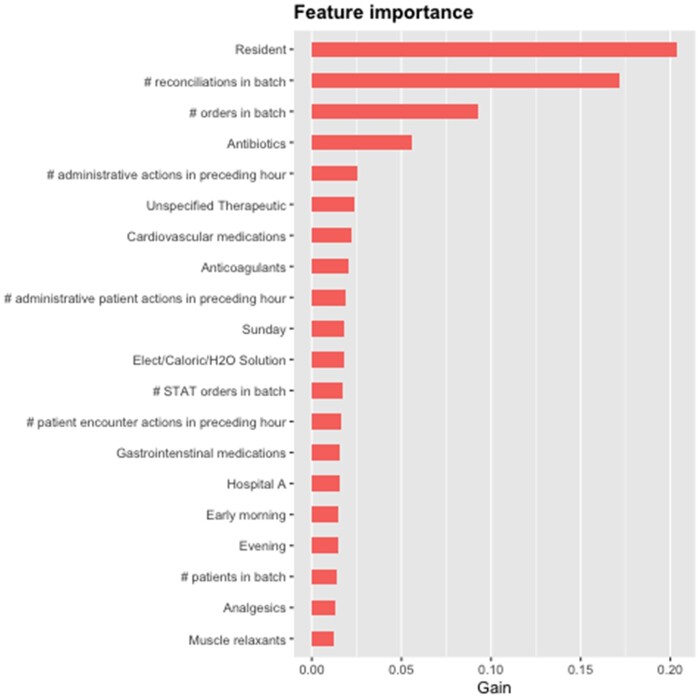

Finally, we examine the global and local feature importance of model features. In Figure 4, we display the 20 features with the highest gain. Whether the provider is a Resident has the greatest impact, followed closely by the number of reconciliations contained in an order batch. The number of individual orders in a batch and orders for antibiotics has moderate gain, whereas remaining features have relatively low influence over the model at the aggregate level.

Figure 4.

Top 20 features with the highest global importance. Gain represents the improvement in accuracy brought by a feature to the branches it is on.

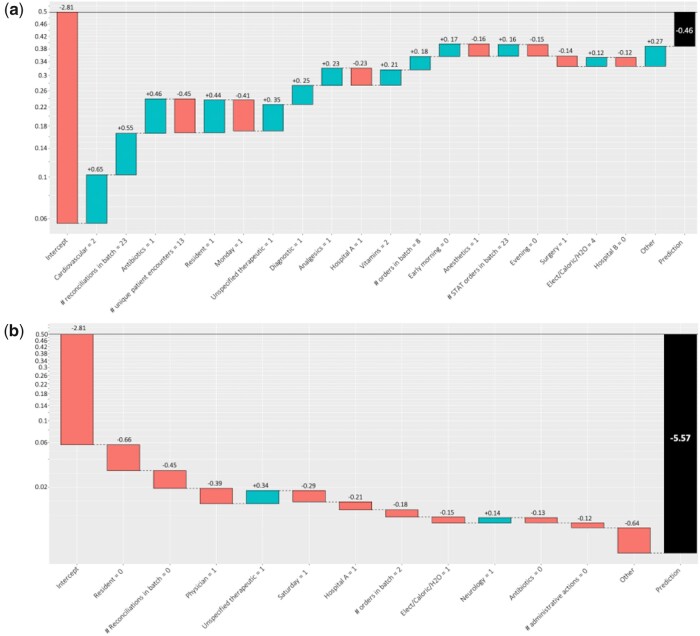

To understand how these features impact individual predictions, we visualize local feature importance (Figures 5A and 6B) as the log-odds of an order requiring pharmacist intervention with the addition of each feature to the model. The baseline intercept corresponds to the naive probability that any single order batch requires intervention (5.61%). Figure 5A visualizes these effects for a randomly sampled order from the test set where the outcome of the model resulted in a true positive, Figure 5B visualizes a true negative, Figure 6A visualizes a false positive, and Figure 6B visualizes a false negative. The y-axis corresponds to the probabilities associated with the calculated log-odds, red bars correspond to a decrease in the log-odds of an order requiring intervention, and the blue bars signify an increase in the log-odds. The order represented in Figure 5A contains 2 cardiovascular medications, which is associated with an increase in the log-odds of this order requiring the intervention of 0.65 over the baseline rate (5.61% in the sample). The plot also showed significant increases in the log-odds attributed to the number of reconciliations contained in the batch, orders for antibiotics, and providers who are residents (+0.55, +0.46, and +0.44, respectively). The number of patients the provider saw in the hour preceding the submission of the order and the day of the week (Monday) was among the features that reduced the log-odds of the order requiring intervention (by −0.45 and −0.41, respectively).

Figure 5.

The y-axis represents the change in the probability of the order requiring intervention. Red bars represent a decrease in the log-odds, whereas blue bars represent an increase. (A) Contribution of features to the log-odds of a true positive order. The estimated probability of this order requiring intervention is 0.39, well above the 0.076 decision boundary and consistent with the observed outcome. (B) Contribution of features to the log-odds of a true negative order. The estimated probability of this order requiring intervention is 0.004, below the 0.076 decision boundary.

Figure 6.

The y-axis represents the change in the probability of the order requiring intervention. Red bars represent a decrease in the log-odds, whereas blue bars represent an increase. (A) Contribution made by individual features to the log-odds of a false-positive order. The estimated probability of this order requiring intervention is 0.10, which is above the 0.076 decision boundary, though this particular order was not observed to require intervention. (B) Contribution made by individual features to the log-odds of a false-negative order. The estimated probability of this order requiring intervention is 0.003. Despite being well below the 0.076 decision boundary, this particular order did require intervention.

DISCUSSION

The widespread deployment of EHRs and computerized order entry systems has largely reduced medication order errors and inefficiencies in the inpatient setting. Emerging research suggests, however, that they have also introduced new sources of error related to the interaction between the provider and the platform. Despite this, prior work has centered on the compatibility of the medication ordered with the patient’s medical records. We instead developed a machine learning model using provider behavioral data and other contextual features related to the usage of these systems. We collected data on providers’ actions in the EHR and pharmacy orders over a 2-week period within the hospital system. We then built a classification model to identify incoming orders requiring pharmacist intervention and tuned the model considering the constraints of the pharmacist’s workflow. The resultant model had an AUROC curve of 0.91and an AUPR curve of 0.44.

Though the precision-recall curve in Figure 2 suggests that false positives and negatives are not entirely separable, we show that by strategically tuning the model to the clinical context in which it is deployed we can still bring significant value to users. The model performance metrics (Table 4a) show a very low number of false negatives (2) when deprioritizing 35% (1933 + 2) of orders deemed by the model as not requiring intervention. While this reduction may not be as meaningful to a well-resourced institution, many hospitals have understaffed pharmacies. In these settings, such an intervention may be critical for managing the workload on pharmacy staff. Future work may further improve the accuracy of the model by taking into consideration the severity of the intervention or stratifying by type of intervention. This may improve the model’s utility in a broader range of clinical contexts.

The features that have the highest gain in our model (Figures 5A and 6B) are consistent with clinical experience. For example, Residents are often the least experienced class of provider and can have high workloads. This could account for their orders having a higher likelihood of requiring intervention. We also see order reconciliations providing substantial gain in this model. The reconciliation of medications involves reviewing medications that patients were receiving at an earlier phase of care (either as an outpatient prior to being admitted or on a different unit prior to being transferred) and decide which ones to continue and discontinue depending on the change of clinical context. Clinicians may anchor on the patient’s previous prescriptions, biasing them toward continuing these medications and not thoughtfully assessing whether the change in context should correspond to an adjustment.

The total number of orders in a batch might correlate to a higher rate of intervention because each individual order has some baseline probability of containing an error and the probability of requiring intervention increases for batches containing more orders. It could also represent cognitive overburdening of the submitting clinician; orders often accumulate as the clinician is rounding and are submitted together at the end, providing opportunity for errors associated with switching among patients and their different needs. Finally, antibiotic ordering is understood to be complex and many institutions have structured guidelines and oversight groups that direct their approach to order antibiotics. It is thus not a surprise that antibiotic ordering is associated to increased gain in our model.

This modeling approach offers us a novel perspective on the factors influencing order entry by focusing on the behavior of the provider and errors that arise from the workflow around the EHR. Whereas previous models predicting errors ingest patients’ medical records, by focusing on the behavior of the clinician, we also reduce the risk to the privacy and security of these patients’ data while still being useful to pharmacists.

LIMITATIONS AND FUTURE WORK

In our analysis, we used data from 2 weeks in July 2017. While we believe that this sample is sufficient to demonstrate the use of clinician behavior and other contextual features in predicting the occurrence of order errors, there may be seasonality and other effects that limit the generalizability of the model. For example, July is the start of the year for medical and surgical trainees. This introduces the possibility of increased order errors due to new interns being less knowledgeable about medications, the EHR system, and about processes in busy health systems.29 Further analysis using longer periods of data collection is needed to account for new trainees’ evolving clinical experience and knowledge.

Future work may also consider comparing the results of these models across hospital systems to gain a better understanding of how different clinical contexts influence the occurrence of such errors; however, each hospital system is likely idiosyncratic in terms of the culture, processes, and procedures which may affect the occurrence and treatment of order errors. We therefore believe that models for detecting these errors will likely need to be tuned for the specific hospital in which they are deployed. Additional refinement of order error by type (eg, improper dosage, incorrect medication, etc.) may bring further precision to these models, and improve their utility to the clinician in context.

The implementation and deployment of this model in the hospital setting remain an open question; specifically, what features are available at the time the batch of orders is submitted to run the model and provide decision support. Three types of features outlined in the analysis section include measures of EHR clinical engagement, details of orders, and contextual data related to clinician and order. Both of the latter feature sets are readily available at order time. The most difficult feature is the former (EHR clinical engagement) that is not routinely available in real time from our EHR vendor. A custom build from the EHR would be required to access these data elements. Future work could analyze more subfeature sets to see how to maintain performance given features more readily available.

CONCLUSION

Errors involving medications are a significant challenge that is well suited to interventions based on machine learning models. Conventional approaches have opted to compare medication orders to the contents of the patient’s medical records and do not consider sources of error that are produced by EHRs and reflected in the provider’s behavior.

In this work, we develop a machine learning model that relies only on features related to the provider’s behavior and basic contextual information related to the order to demonstrate a well-performing model. Furthermore, we show that with proper tuning, such models can significantly improve the workload on pharmacists without risking the privacy and security of sensitive patient data.

FUNDING

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation grant number 1928614.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors provided critical feedback and helped to shape the research, analysis, and manuscript. MB, YA, and ON conceived and planned the analysis. JC and EI collected the data. MB carried out the development of the ML model with input from JC, EI, YA, and ON. MB, EI, YA, and ON contributed to the interpretation of the results; EI contributed clinical insight. MB took the lead in writing the manuscript with input from all coauthors.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Supplementary material is available at JAMIA Open online.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

DATA AVAILABILITY

The data that support the findings of this study are not available due to the sensitive context of this study.

Supplementary Material

REFERENCES

- 1.Johnson SG, Speedie S, Simon G, et al. Application of an ontology for characterizing data quality for a secondary use of EHR data. Appl Clin Inform 2016; 7 (1): 69–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khairat S, Marc D, Crosby W, et al. Reasons for physicians not adopting clinical decision support systems: critical analysis. JMIR Med Inform 2018; 6 (2): e24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Musen MA, Middleton B, Greenes RA.. Clinical decision-support systems. In: Shortliffe EH, Cimino JJ, eds. Biomedical Informatics. London: Springer; 2014: 643–74. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Osheroff JA, Teich JM, Middleton B, et al. A roadmap for national action on clinical decision support. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2007; 14 (2): 141–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tolley CL, Forde NE, Coffey KL, et al. Factors contributing to medication errors made when using computerized order entry in pediatrics: a systematic review. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2018; 25 (5): 575–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Patient Safety Primer: Systems Approach. In: Patient Safety Network. 2019. https://psnet.ahrq.gov/primer/systems-approach Accessed September 23, 2022.

- 7.Makary MA, Daniel M.. Medical error—the third leading cause of death in the US. BMJ 2016; 353: i2139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Corny J, Rajkumar A, Martin O, et al. A machine learning–based clinical decision support system to identify prescriptions with a high risk of medication error. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2020; 27 (11): 1688–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Benjamin DM.Reducing medication errors and increasing patient safety: case studies in clinical pharmacology. J Clin Pharmacol 2003; 43 (7): 768–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Muir PR, Bortoletto DA.. Burnout among Australian hospital pharmacists. J Pharm Pract Res 2007; 37 (3): 187–9. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wuliji T.Current status of human resources and training in hospital pharmacy. Am J Health Syst Pharm 2009; 66 (5 Suppl 3): s56–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gabler E. At Walgreens, complaints of medication errors go missing. New York Times, February 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/02/21/health/pharmacies-prescription-errors.html Accessed September 23, 2022.

- 13.Gabler E. How chaos at chain pharmacies is putting patients at risk. New York Times, January 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/01/31/health/pharmacists-medication-errors.html Accessed September 23, 2022.

- 14.Koppel R, Metlay JP, Cohen A, et al. Role of computerized physician order entry systems in facilitating medication errors. JAMA 2005; 293 (10): 1197–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bates DW, Leape LL, Cullen DJ, et al. Effect of computerized physician order entry and a team intervention on prevention of serious medication errors. JAMA 1998; 280 (15): 1311–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schiff GD, Amato MG, Eguale T, et al. Computerised physician order entry-related medication errors: analysis of reported errors and vulnerability testing of current systems. BMJ Qual Saf 2015; 24 (4): 264–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bobb A, Gleason K, Husch M, et al. The epidemiology of prescribing errors: the potential impact of computerized pre-scriber order entry. Arch Intern Med 2004; 164 (7): 785–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ash JS, Berg M, Coiera E.. Some unintended consequences of information technology in health care: the nature of patient care information system-related errors. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2004; 11 (2): 104–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Segal G, Segev A, Brom A, et al. Reducing drug prescription errors and adverse drug events by application of a probabilistic, machine learning based clinical decision support system in an inpatient setting. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2019; 26 (12): 1560–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nguyen T-L, Leguelinel-Blache G, Kinowski J-M, et al. Improving medication safety: development and impact of a multivariate model-based strategy to target high-risk patients. PLoS One 2017; 12 (2): e0171995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Westbrook JI, Raban MZ, Walter SR, et al. Task errors by emergency physicians are associated with interruptions, multitasking, fatigue and working memory capacity: a prospective, direct observation study. BMJ Qual Saf 2018; 27 (8): 655–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baddeley A.Working memory. Science 1992; 255 (5044): 556–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baddeley A.Working Memory, Thought, and Action. Vol. 45. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Potter P, Wolf L, Boxerman S, et al. Understanding the cognitive work of nursing in the acute care environment. J Nurs Adm 2005; 35 (7): 327–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thomas L, Donohue-Porter P, Stein Fishbein J.. Impact of interruptions, distractions, and cognitive load on procedure failures and medication administration errors. J Nurs Care Qual 2017; 32 (4): 309–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carspecken CW, Sharek PJ, Longhurst C, et al. A clinical case of electronic health record drug alert fatigue: consequences for patient outcome. Pediatrics 2013; 131 (6): e1970–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McCoy AB, Thomas EJ, Krousel-Wood M, Sittig DF.. Clinical decision support alert appropriateness: a review and proposal for improvement. Ochsner J 2014; 14 (2): 195–202. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Khan S, Richardson S, Liu A, et al. Improving provider adoption with adaptive clinical decision support surveillance: an observational study. JMIR Hum Factors 2019; 6 (1): e10245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Phillips DP, Barker GE.. A July spike in fatal medication errors: a possible effect of new medical residents. J Gen Intern Med 2010; 25 (8): 774–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are not available due to the sensitive context of this study.