Abstract

Background

Most people who stop smoking gain weight. This can discourage some people from making a quit attempt and risks offsetting some, but not all, of the health advantages of quitting. Interventions to prevent weight gain could improve health outcomes, but there is a concern that they may undermine quitting.

Objectives

To systematically review the effects of: (1) interventions targeting post‐cessation weight gain on weight change and smoking cessation (referred to as 'Part 1') and (2) interventions designed to aid smoking cessation that plausibly affect post‐cessation weight gain (referred to as 'Part 2').

Search methods

Part 1 ‐ We searched the Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group's Specialized Register and CENTRAL; latest search 16 October 2020.

Part 2 ‐ We searched included studies in the following 'parent' Cochrane reviews: nicotine replacement therapy (NRT), antidepressants, nicotine receptor partial agonists, e‐cigarettes, and exercise interventions for smoking cessation published in Issue 10, 2020 of the Cochrane Library. We updated register searches for the review of nicotine receptor partial agonists.

Selection criteria

Part 1 ‐ trials of interventions that targeted post‐cessation weight gain and had measured weight at any follow‐up point or smoking cessation, or both, six or more months after quit day.

Part 2 ‐ trials included in the selected parent Cochrane reviews reporting weight change at any time point.

Data collection and analysis

Screening and data extraction followed standard Cochrane methods. Change in weight was expressed as difference in weight change from baseline to follow‐up between trial arms and was reported only in people abstinent from smoking. Abstinence from smoking was expressed as a risk ratio (RR). Where appropriate, we performed meta‐analysis using the inverse variance method for weight, and Mantel‐Haenszel method for smoking.

Main results

Part 1: We include 37 completed studies; 21 are new to this update. We judged five studies to be at low risk of bias, 17 to be at unclear risk and the remainder at high risk.

An intermittent very low calorie diet (VLCD) comprising full meal replacement provided free of charge and accompanied by intensive dietitian support significantly reduced weight gain at end of treatment compared with education on how to avoid weight gain (mean difference (MD) −3.70 kg, 95% confidence interval (CI) −4.82 to −2.58; 1 study, 121 participants), but there was no evidence of benefit at 12 months (MD −1.30 kg, 95% CI −3.49 to 0.89; 1 study, 62 participants). The VLCD increased the chances of abstinence at 12 months (RR 1.73, 95% CI 1.10 to 2.73; 1 study, 287 participants). However, a second study found that no‐one completed the VLCD intervention or achieved abstinence.

Interventions aimed at increasing acceptance of weight gain reported mixed effects at end of treatment, 6 months and 12 months with confidence intervals including both increases and decreases in weight gain compared with no advice or health education. Due to high heterogeneity, we did not combine the data. These interventions increased quit rates at 6 months (RR 1.42, 95% CI 1.03 to 1.96; 4 studies, 619 participants; I2 = 21%), but there was no evidence at 12 months (RR 1.25, 95% CI 0.76 to 2.06; 2 studies, 496 participants; I2 = 26%).

Some pharmacological interventions tested for limiting post‐cessation weight gain (PCWG) reduced weight gain at the end of treatment (dexfenfluramine, phenylpropanolamine, naltrexone). The effects of ephedrine and caffeine combined, lorcaserin, and chromium were too imprecise to give useful estimates of treatment effects. There was very low‐certainty evidence that personalized weight management support reduced weight gain at end of treatment (MD −1.11 kg, 95% CI −1.93 to −0.29; 3 studies, 121 participants; I2 = 0%), but no evidence in the longer‐term 12 months (MD −0.44 kg, 95% CI −2.34 to 1.46; 4 studies, 530 participants; I2 = 41%). There was low to very low‐certainty evidence that detailed weight management education without personalized assessment, planning and feedback did not reduce weight gain and may have reduced smoking cessation rates (12 months: MD −0.21 kg, 95% CI −2.28 to 1.86; 2 studies, 61 participants; I2 = 0%; RR for smoking cessation 0.66, 95% CI 0.48 to 0.90; 2 studies, 522 participants; I2 = 0%).

Part 2: We include 83 completed studies, 27 of which are new to this update.

There was low certainty that exercise interventions led to minimal or no weight reduction compared with standard care at end of treatment (MD −0.25 kg, 95% CI −0.78 to 0.29; 4 studies, 404 participants; I2 = 0%). However, weight was reduced at 12 months (MD −2.07 kg, 95% CI −3.78 to −0.36; 3 studies, 182 participants; I2 = 0%).

Both bupropion and fluoxetine limited weight gain at end of treatment (bupropion MD −1.01 kg, 95% CI −1.35 to −0.67; 10 studies, 1098 participants; I2 = 3%); (fluoxetine MD −1.01 kg, 95% CI −1.49 to −0.53; 2 studies, 144 participants; I2 = 38%; low‐ and very low‐certainty evidence, respectively). There was no evidence of benefit at 12 months for bupropion, but estimates were imprecise (bupropion MD −0.26 kg, 95% CI −1.31 to 0.78; 7 studies, 471 participants; I2 = 0%). No studies of fluoxetine provided data at 12 months.

There was moderate‐certainty that NRT reduced weight at end of treatment (MD −0.52 kg, 95% CI −0.99 to −0.05; 21 studies, 2784 participants; I2 = 81%) and moderate‐certainty that the effect may be similar at 12 months (MD −0.37 kg, 95% CI −0.86 to 0.11; 17 studies, 1463 participants; I2 = 0%), although the estimates are too imprecise to assess long‐term benefit.

There was mixed evidence of the effect of varenicline on weight, with high‐certainty evidence that weight change was very modestly lower at the end of treatment (MD −0.23 kg, 95% CI −0.53 to 0.06; 14 studies, 2566 participants; I2 = 32%); a low‐certainty estimate gave an imprecise estimate of higher weight at 12 months (MD 1.05 kg, 95% CI −0.58 to 2.69; 3 studies, 237 participants; I2 = 0%).

Authors' conclusions

Overall, there is no intervention for which there is moderate certainty of a clinically useful effect on long‐term weight gain. There is also no moderate‐ or high‐certainty evidence that interventions designed to limit weight gain reduce the chances of people achieving abstinence from smoking.

Keywords: Humans, Electronic Nicotine Delivery Systems, Nicotine, Smoking Cessation, Tobacco Use Cessation Devices, Weight Gain

Plain language summary

Interventions for preventing weight gain after smoking cessation

What is the best way to avoid putting on weight after stopping smoking?

Key messages

We are not certain which programmes or treatments work best to help people avoid gaining weight in the long term (up to 12 months) when stopping smoking, or how they affect success in stopping smoking. This is because the evidence shows varied and unclear effects on weight gain. Further studies should continue to look at how to limit weight gain in people who are stopping smoking. Future studies of new medicines to help people stop smoking should also measure changes in their weight.

Stopping smoking and weight gain

If you smoke, the best thing you can do for your health is to stop. But people often put on weight when they stop smoking, usually in the first few months of stopping. Gaining weight might undermine some of the benefits of stopping smoking, and might also affect the motivation of some people trying to stop smoking.

What did we want to find out?

Some programmes to help people stop smoking specifically target weight control. Other ways to help people stop smoking might also affect their weight; these include: exercise programmes, taking medicines, and using nicotine replacement therapy (NRT).

We wanted to find out the best ways to stop weight gain when stopping smoking.

What did we do?

In this update of a previously‐published review, we searched for studies that tested:

‐ specific programmes for weight control while stopping smoking;

‐ other ways to help people stop smoking, if those studies also measured weight change.

We were interested in:

‐ how many people stopped smoking for six months or 12 months;

‐ people's weight at the end of treatment, then after six months and after 12 months.

What did we find?

We found 116 studies in total:

37 studies of specific programmes for weight control for people stopping smoking (21 new studies for this update); and 83 studies of other ways to help people stop smoking (27 new studies for this update). Four of these studies contributed to both.

The 37 studies of specific programmes tested behavioural programmes, including dieting, to manage weight in 11,514 people trying to stop smoking. Some of the behavioural programmes were acceptance‐based, in which people also learn self‐regulation skills (for example, how to deal with cravings) to help them keep to the behaviours needed to lose weight. Most studies (27) were done in the USA and others took place in Australia, Canada, China and Europe.

The 83 studies of other ways of stopping smoking included 46,248 people and looked at:

exercise programmes; taking NRT; taking a medicine called varenicline (used to help people stop smoking); or taking a medicine called fluoxetine (used to treat depression).

Of these studies, 39 were done in the USA and the rest took place in other countries around the world. Very few studies reported on side effects.

What are the main results of our review?

Programmes aimed at limiting weight gain

Compared with no programme or brief advice only, a personalized weight‐management programme may reduce weight gain at the end of treatment, after six months and after 12 months. However, a weight‐management programme without personalized assessment, planning and feedback may not reduce weight gain, and may reduce the number of people who stop smoking.

Compared with no programme, acceptance‐based programmes for weight:

may help more people to stop smoking after six months and 12 months; but may make little to no difference to their weight gain.

Other programmes and treatments that might affect weight

Taking part in an exercise programme to help stop smoking may reduce weight gain after 12 months, compared with not taking part in one.

Using NRT probably reduces weight gain slightly after 12 months, compared with not using NRT.

Taking varenicline makes little difference to weight gain at the end of treatment, and may make little difference after six months or after 12 months.

Taking fluoxetine may reduce weight gain at the end of treatment, but we do not know how it affects weight gain after six months or 12 months.

What are the limitations of the evidence?

We are certain that there is no difference in weight gain at the end of treatment with varenicline, and further studies are unlikely to change this result. However, our confidence in all of the other evidence is limited, mainly because of small numbers of studies that could be compared, and small numbers of people taking part in them. The results varied widely, and there were not enough studies for us to be sure of the results. Our confidence is likely to change if further evidence becomes available.

How up to date is this evidence?

The evidence is current up to October 2020.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. Behavioural weight management interventions compared to brief advice or no intervention for post‐cessation weight control.

| Behavioural weight management interventions compared to brief advice or no intervention for post‐cessation weight control for preventing weight gain after smoking cessation | ||||||

| Patient or population: People wanting to quit smoking Setting: Community Intervention: Behavioural weight management interventions Comparison: advice or no intervention for post‐cessation weight control | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with advice or no intervention for post‐cessation weight control# | Risk with behavioural weight management interventions | |||||

| Mean weight change (kg) at end of treatment ‐ Weight management education versus no weight intervention | 1.45 kg | 1.41 kg (0.88 to 1.95) | MD 0.04 kg lower (0.57 lower to 0.5 higher) | 140 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWa,b | ‐ |

| Mean weight change (kg) at 6 months ‐ Weight management education verses no weight intervention | 0.97 kg | 1.86 kg (0.19 to 3.52) | MD 0.89 kg higher (0.78 lower to 2.55 higher) | 81 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWb,c | ‐ |

| Mean weight change (kg) at 12 months ‐ Weight management education versus no weight intervention | 0.46 kg | 0.25 kg (‐1.82 to 2.32) | MD 0.21 kg lower (2.28 lower to 1.86 higher) | 61 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOWc,d | ‐ |

| Smoking cessation at 6 months ‐ Weight management education versus no intervention | 275 per 1000 | 280 per 1000 (214 to 365) | RR 1.02 (0.78 to 1.33) | 660 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWd | ‐ |

| Smoking cessation at 12 months ‐ Weight management education versus no intervention | 294 per 1000 | 194 per 1000 (141 to 265) | RR 0.66 (0.48 to 0.90) | 522 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWa,b | ‐ |

| Mean weight change (kg) at end of treatment ‐ Personalised weight management support versus no weight intervention | 1.45 kg | 0.34 kg (‐0.48 to 1.16) | MD 1.11 kg lower (1.93 lower to 0.29 lower) | 121 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWa,b | ‐ |

| Mean weight change (kg) at 6 months ‐ Personalised weight management support versus no weight intervention | 0.97 kg | 0.01 kg (‐1.21 to 1.22) | MD 0.96 kg lower (2.18 lower to 0.25 higher) | 816 (5 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOWe,f | ‐ |

| Mean weight change (kg) at 12 months ‐ Personalised weight management support versus no weight intervention | 0.46 kg | 0.02 kg (‐1.88 to 1.92) | MD 0.44 kg lower (2.34 lower to 1.46 higher) | 530 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOWa,d | ‐ |

| Smoking cessation at 6 months ‐ Personalised weight management support versus no intervention | 188 per 1000 | 178 per 1000 (154 to 206) | RR 0.95 (0.82 to 1.10) | 5517 (7 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWg,h | ‐ |

| Smoking cessation at 12 months ‐ Personalised weight management support versus no intervention | 475 per 1000 | 308 per 1000 (214 to 437) | RR 0.65 (0.45 to 0.92) | 3441 (5 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWa,i | ‐ |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RCT: randomized controlled trial; RR: Risk ratio; MD: Mean difference | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

aDowngraded one level due to risk of bias. All studies judged to be at unclear or high risk of bias. Results not sensitive to removal of studies at high risk of bias. bDowngraded one level due to imprecision. Few studies and participants contributed data. cDowngraded one level due to risk of bias. Of the two studies contributing data, one was at high risk of bias, and other at low risk. Results not sensitive to removal of study at high risk.dDowngraded two levels due to imprecision. Wide CIs incorporate clinically meaningful weight reduction and clinically meaningful weight increase. eDowngraded two levels due to risk of bias. All studies judged to be at high risk. fDowngraded one level due to imprecision. Wide CIs encompass benefit and no clinically meaningful difference. gDowngraded one level due to risk of bias. All studies at high or unclear risk of bias, bar one small study at low risk of bias. Results not sensitive to removing studies at high risk of bias.

hDowngraded one level due to imprecision. Wide CIs incorporate clinically meaningful difference in favour of control group, as well as no clinically significant difference. iDowngraded one level due to inconsistency due to substantial unexplained statistical heterogeneity (I2 = 89%). #Calculated as weighted means from control group data.

Summary of findings 2. Acceptance interventions for weight concern compared to no weight management intervention for post‐cessation weight control.

| Acceptance interventions for weight concern compared to no weight management intervention for preventing weight gain after smoking cessation | ||||||

| Patient or population: People wanting to quit smoking Setting: Community Intervention: Acceptance interventions for weight concern Comparison: No weight management intervention | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with no weight management intervention# | Risk with acceptance interventions for weight concern | |||||

| Mean weight change (kg) at end of treatment | see comment | see comment | see comment | 169 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOWa,b | Substantial unexplained statistical heterogeneity precluded meta‐analysis. Of the 3 studies, 1 had wide CIs encompassing both benefit and harm, 1 suggested benefit with CIs excluding no difference, and 1 suggested harm with CIs excluding no difference. |

| Mean weight change (kg) at 6 months | 3.5 kg | 3.5 kg (1.97 to 5.03) | MD 0 kg (1.53 lower to 1.53 higher) | 106 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWa,c,d | ‐ |

| Mean weight change (kg) at 12 months | 4.39 kg | 3.69 kg (1.44 to 5.95) | MD 0.7 kg lower (2.95 lower to 1.56 higher) | 76 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOWa,c,d | ‐ |

| Smoking cessation at 6 months | 218 per 1000 | 309 per 1000 (224 to 427) | RR 1.42 (1.03 to 1.96) | 619 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWa,e | ‐ |

| Smoking cessation at 12 months | 143 per 1000 | 179 per 1000 (109 to 294) | RR 1.25 (0.76 to 2.06) | 496 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ LOWa,d | ‐ |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RCT: randomized controlled trial; RR: Risk ratio; MD: Mean difference | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

aDowngraded one level due to risk of bias. All studies judged to be at unclear or high risk of bias. Results not sensitive to removal of studies at high risk of bias. bDowngraded two levels due to inconsistency. Unexplained statistical heterogeneity prevented pooling data. cDowngraded one level due to inconsistency. Moderate unexplained statistical heterogeneity. dDowngraded two levels due to imprecision. CIs encompass clinically significant benefit and clinically significant harm. eDowngraded one level due to imprecision. < 300 events overall and CIs encompass clinically significant benefit and no clinically significant difference. #Calculated as weighted means from control group data.

Summary of findings 3. Exercise interventions for smoking cessation compared to no exercise intervention for preventing weight gain after smoking cessation.

| Exercise interventions for smoking cessation compared to no exercise intervention for preventing weight gain after smoking cessation | ||||||

| Patient or population: People who have quit smoking Setting: Community Intervention: Exercise interventions for smoking cessation Comparison: no exercise intervention | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with no exercise intervention# | Risk with Exercise interventions for smoking cessation | |||||

| Mean weight change (kg) at end of treatment | 2.85 kg | 2.6 kg (2.07 to 3.14) | MD 0.25 kg lower (0.78 lower to 0.29 higher) | 404 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWa,b | ‐ |

| Mean weight change (kg) at 12 months | 4.67 kg | 2.6 kg (0.89 to 4.31) | MD 2.07 kg lower (3.78 lower to 0.36 lower) | 182 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWa,b | ‐ |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RCT: randomized controlled trial; RR: Risk ratio; MD: Mean difference | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

aDowngraded one level due to imprecision. CIs encompass clinically significant benefit as well as no clinically significant difference. bDowngraded one level due to inconsistency ‐ end of treatment and 12 month outcomes are clinically significantly different, with no clear or plausible reason for difference. #Risk with no intervention from Aubin, 2012.

Summary of findings 4. Nicotine replacement therapy for smoking cessation compared to placebo for preventing weight gain after smoking cessation.

| Nicotine replacement therapy for smoking cessation compared to placebo for preventing weight gain after smoking cessation | ||||||

| Patient or population: People who have quit smoking Setting: Community Intervention: Nicotine replacement therapy for smoking cessation Comparison: placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with placebo# | Risk with nicotine replacement therapy for smoking cessation | |||||

| Mean weight change (kg) at end of treatment | 2.85 kg | 2.33 kg (1.86 to 2.8) | MD 0.52 kg lower (0.99 lower to 0.05 lower) | 2784 (21 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATEa,b,c | ‐ |

| Mean weight change (kg) at 6 months | 4.23 kg | 4.15 kg (3.72 to 4.58) | MD 0.08 kg lower (0.51 lower to 0.35 higher) | 1021 (11 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATEa,d | ‐ |

| Mean weight change (kg) at 12 months | 4.67 kg | 4.3 (3.81 to 4.67) | MD 0.37 kg lower (0.86 lower to 0.11 higher) | 1463 (17 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATEe | ‐ |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RCT: randomized controlled trial; RR: Risk ratio; MD: Mean difference | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

aDowngraded one level due to risk of bias. All studies at high or unclear risk. Results not sensitive to removal of studies at high risk of bias. bStatistical heterogeneity was substantial due to one study (2 Abelin 1989), which showed a 4.3 kg difference between weight gain in the treatment and control arms. When this study was removed, statistical heterogeneity reduced to 0% and the overall estimate decreased. Not downgraded on this basis. cFunnel plot showed some asymmetry, suggesting that smaller studies with less weight gain in intervention groups relative to control groups may be missing, but not downgraded on this basis, as asymmetry thought plausibly due to chance, given asymmetry in opposite direction at six months. dFunnel plot showed some asymmetry, suggesting that smaller studies with greater weight gain in intervention groups relative to control groups may be missing, but not downgraded on this basis as asymmetry thought plausibly due to chance, given asymmetry in opposite direction at end of treatment. eDowngraded one level due to imprecision. CIs encompass clinically significant benefit and no clinically significant difference. #Risk with no intervention from Aubin, 2012.

Summary of findings 5. Varenicline for smoking cessation compared to placebo for preventing weight gain after smoking cessation.

| Varenicline for smoking cessation compared to placebo for preventing weight gain after smoking cessation | ||||||

| Patient or population: People who have quit smoking Setting: Community Intervention: Varenicline Comparison: placebo for smoking cessation | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with placebo for smoking cessation# | Risk with varenicline | |||||

| Mean weight change (kg) at end of treatment | 2.85 kg | 2.62 kg (2.32 to 2.91) | MD 0.23 kg lower (0.53 lower to 0.06 higher) | 2566 (14 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ HIGH | ‐ |

| Mean weight change (kg) at 6 months | 4.23 kg | 4.14 kg (3.14 to 5.13) | MD 0.09 kg lower (1.09 lower to 0.9 higher) | 384 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWa | ‐ |

| Mean weight change (kg) at 12 months | 4.67 kg | 5.72 kg (4.09 to 7.36) | MD 1.05 kg higher (0.58 lower to 2.69 higher) | 237 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWb.c | ‐ |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RCT: randomized controlled trial; RR: Risk ratio; MD: Mean difference | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

aDowngraded two levels due to imprecision. CIs incorporate clinically significant benefit as well as clinically significant harm. bDowngraded one level due to risk of bias. All studies at unclear risk. cDowngraded one level due to imprecision. CIs incorporate clinically significant benefit and no difference. #Risk with no intervention from Aubin, 2012.

Summary of findings 6. Fluoexetine compared to placebo for smoking cessation for preventing weight gain after smoking cessation.

| Fluoxetine compared to placebo for smoking cessation for preventing weight gain after smoking cessation | ||||||

| Patient or population: People who have quit smoking Intervention: Fluoxetine for smoking cessation Comparison: placebo for smoking cessation | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with placebo for smoking cessation# | Risk with all types of antidepressant | |||||

| Mean weight change (kg) at end of treatment | 2.85 kg | 1.84 kg (1.36 to 2.32) | MD 1.01 kg lower (1.49 lower to 0.53 lower) | 144 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWa,b | ‐ |

| Mean weight change (kg) at 6 months | 4.67 kg | 3.66 kg (0.29 to 7.04) | MD 1.01 kg lower (4.38 lower to 2.37 higher) | 124 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ VERY LOWa,c | no studies followed up participants at 12 months |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RCT: randomized controlled trial; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

aDowngraded one level due to risk of bias. One study at unclear risk, one at high risk. bDowngraded one level due to imprecision. Only two studies contributed data, overall; n < 150. cDowngraded two levels due to imprecision; CIs incorporate clinically significant weight loss and clinically significant weight gain. #Risk with no intervention from Aubin, 2012

Background

Description of the condition

Although smoking cessation is associated with substantial health benefits, it is often accompanied by weight gain (Aubin, 2012; Audrain‐McGovern 2011). Increases in weight are most marked in the first months after quitting (Aubin, 2012), and longer‐term studies show further moderate increases in weight in quitters for a number of years compared with continuing smokers (2 Lycett 2011). Reports vary about the amount gained, but on average sustained quitters are likely to gain an additional two to five kilograms (kgs) in the first five years (Chiolero 2008; Klesges 1997; Tian 2015; Veldheer 2015; Williamson 1991), and up to seven kgs after eight years (2 Lycett 2011). It is important to note, however, that average weight gain masks a substantial variability at the individual level, with evidence suggesting some quitters may lose weight (Aubin, 2012; Bossé 1980), whereas around 10% to 15% gain 10 kgs or more (Aubin, 2012; Tian 2015; Williamson 1991). Factors that have been consistently associated with greater weight gain after smoking cessation include female sex, higher cigarettes smoked per day/nicotine dependency and higher body mass index (BMI) at quitting (Komiyama 2013; Scherr 2015; Veldheer 2015; Williamson 1991).

Description of the intervention

Interventions included in this review are discussed in two parts, described below.

Some smoking cessation interventions have been developed to promote smoking cessation and simultaneously control weight gain. They include behavioural interventions, such as exercise and energy restriction or healthy‐eating advice. Some pharmacological treatments with known or potential efficacy for reducing weight have also been tested. Interventions may combine both behavioural components and pharmacological treatments, or these may be tested individually. They are often delivered concurrently with smoking cessation support during the first few months of quitting, when the rate of weight gain is at its highest. The effects of these interventions on both smoking abstinence and weight are included in Part 1 of this review.

Several treatments for smoking cessation have been developed independently of concerns about weight gain, with the sole aim of assisting smoking cessation. Some of these, such as nicotine replacement therapy, e‐cigarettes, antidepressants, varenicline and exercise might plausibly influence weight gain as well as smoking cessation. The effects of these interventions on smoking cessation are evaluated in the relevant Cochrane Reviews, but the effects on weight gain are summarised only in the exercise intervention review (Ussher 2019). The effects of these medications on weight gain are included in Part 2 of this review.

How the intervention might work

Smoking (and quitting smoking) is likely to exert its effect on weight through the biological actions of nicotine and also through the influence of smoking on eating behaviours. Nicotine increases metabolic rate (Collins 1994; Dallosso 1984), and withdrawal of nicotine when people quit smoking results in a decrease in rate (Hofstetter 1986)

Nicotine may also be an appetite suppressant, and people may replace eating with smoking (Chiolero 2008). Particularly during the initial period of withdrawal from nicotine when quitting smoking, some people may eat more in order to deal with nicotine cravings/withdrawal, to satiate increases in appetite and replace the hand‐to‐mouth action of smoking (Audrain‐McGovern 2011; Ward 2001). Through these mechanisms, it is likely that an energy imbalance is created favouring weight gain.

Behavioural interventions that limit energy intake (i.e. dieting or calorie restriction) or increase energy expenditure (i.e. exercise) may serve to reduce any energy imbalance that occurs during quitting, and thus reduce the amount of weight gained (Cheskin 2005; Gritz 1988; Hall 1986; 1 Hall 1992; Hughes 1991).

Pharmacological treatments may limit weight gain through several mechanisms. Appetite suppressants may offset the increased appetite that accompanies cessation, limiting any increase in calorie consumption after quitting to satiate increased hunger. Pharmacotherapies that replace nicotine included in Part 2 (nicotine replacement therapies or e‐cigarettes) may reduce nicotine withdrawal effects on metabolism and appetite. Varenicline is a partial agonist of nicotinic receptors in the brain and so may also work through these mechanisms. Depressed mood is a recognised withdrawal symptom of nicotine, and antidepressants are known to affect bodyweight (Serretti 2010), although some increase and some decrease it.

The availability of interventions that limit weight gain might encourage smokers who are concerned about weight gain to try to stop smoking (Filozof 2004), and limiting weight gain may prevent people from returning to smoking to avoid an increase in weight. However, it is possible that some interventions that aim to limit energy intake might undermine the success of a quit attempt (1 Hall 1992). There is evidence that hunger and cigarette cravings are related, that hunger can undermine quit efforts (1 Hall 1992) and that hunger increases urges to smoke in current smokers (Cheskin 2005). There is evidence that early weight gain is associated with successful cessation (Gritz 1988; Hall 1986; Hughes 1991). It is important to investigate further the impact of these interventions on weight gain, and also to evaluate the effect on abstinence rates.

Why it is important to do this review

Among smokers there is a high prevalence of concerns about post‐cessation weight gain, and it has been cited as a primary reason for putting off quit attempts, especially in women (Clark 2004; Klesges 1989; Klesges 1992). Weight consciousness has been found to predict current smoking (Weekley 1992), and weight gain experienced during or after smoking cessation has been associated with relapse (Klesges 1988; Klesges 1989; Klesges 1992). However there is inconsistent evidence that fear of weight gain or actual weight gain after quitting does lead to relapse, with some studies finding associations (1 Copeland 2006; Clark 2006; Meyers 1997; Pomerleau 2001) and others no associations (Fidler 2009; Hutter 2006; Killen 1996; Mizes 1998); methodological differences make it hard to draw a conclusion.

Post‐cessation weight gain can have health consequences, although these do not outweigh the benefit of quitting smoking. In the shorter term, the incidence of diabetes is higher in people who quit smoking than in those who continue with it, an effect that appears to be explained by weight gain (Davey Smith 2005; Yeh 2010), although some evidence suggests in the longer term (more than 10 years) the risk is no higher in those who quit than in those who continued smoking (Luo 2013). Hypertension can also be mediated by post‐cessation weight gain (Gratziou 2009). Additionally, at least one study has suggested that cessation‐related weight gain (more than 5 kgs) may attenuate reductions in cancer risk (Kim 2019). The extent to which these associations are clinically meaningful is unclear. The temporarily increased risk of type 2 diabetes amongst smokers who quit smoking with associated weight gain, is not associated with increased cardiovascular and all‐cause mortality compared to non‐quitters (Hu 2018). Weight gain after smoking cessation has been found not to modify its protective effect on heart attack and stroke (Clair 2013; Kim 2018).

Given the uncertainty of the risks surrounding cessation‐related weight gain, and that concerns about weight gain are cited as a common reason for not attempting quitting, people who smoke, their healthcare providers, and policy‐makers are keen to understand the effects of interventions that could potentially minimize post‐cessation weight gain whilst not adversely affecting cessation. The 2012 version of this review found insufficient evidence to recommend any one type of intervention targeting post‐cessation weight gain. Since then, considerable further literature has been published and new smoking cessation treatments have come onto the market. This updated review considers the entirety of the evidence to date on possible ways to limit post‐cessation weight gain in people abstinent from smoking, and the impact of these interventions on smoking cessation as well as weight.

Objectives

To systematically review the effects of: (1) interventions targeting post‐cessation weight gain on weight change and smoking cessation (referred to as 'Part 1') and (2) interventions designed to aid smoking cessation that may also plausibly affect weight on post‐cessation weight change (referred to as 'Part 2').

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomized controlled trials.

Types of participants

Adults who smoke and are attempting to quit smoking, excluding pregnant women.

In Part 1, we examine smoking cessation in everyone enrolled. In Part 1 and Part 2, we examine the effect of interventions on weight gain in people who have successfully quit smoking only. This is for several reasons. Firstly, if we included those who were not abstinent, mean weight gain would be reduced. This is because people who attempt quitting but fail after a few days do not gain weight, as those who relapse to smoking often lose the weight they gained previously (2 Lycett 2011; O'Hara 1998). Thus the average weight gain of a mixed population of abstinent and non‐abstinent smokers would not reflect the weight gain of either. Secondly, this effect could bias results. If an intervention increased abstinence rates, it is very likely that it would appear to increase weight gain, regardless of whether it actually suppressed weight gain or had no effect. Thirdly, those who return to smoking tend not to attend clinics for follow‐up. Authors typically only report weight data in abstinent smokers, and imputing missing data on weight in those who have relapsed to smoking is problematic. We have little data on the weight trajectory of people who try and fail to achieve abstinence. It is likely that the weight will depend on time since relapse and that imputing data using last observation carried forward or baseline observation carried forward is likely to be misleading. For these reasons, we eschew the intention‐to‐treat approach which is typically used in the Tobacco Addiction Review Group's reviews. This issue has been discussed elsewhere (Parsons 2009b; Parsons 2011; Spring 2011a; Spring 2011b).

Types of interventions

Part 1 ‐ Interventions that are designed specifically to limit post‐cessation weight gain.

Part 2 ‐ Smoking cessation interventions that are not designed primarily to limit post‐cessation weight gain but which might plausibly influence it, i.e. antidepressants, exercise, nicotine replacement therapy (NRT), electronic cigarettes and varenicline, but excluding trials in which all arms receive the same medication, regardless of differences in dose and schedule.

Types of outcome measures

There are two primary outcome measures:

Smoking status at six and 12 months

Mean (SD) change in body weight (kgs) at end of treatment, six, and 12 months.

Both outcomes are fully examined for studies that fit the criteria for Part 1. For Part 2 studies, effects of these interventions on smoking are reported in the parent Cochrane Reviews and we only report the effects of interventions on weight change.

For Part 1 studies of pharmacotherapies, we also evaluate adverse events and serious adverse events. We do not evaluate adverse and serious adverse events for behavioural interventions, following standard Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group guidance. Information on adverse and serious adverse events for Part 2 studies can be found in the Cochrane Reviews on the relevant interventions (see Search methods for identification of studies).

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

Part 1 ‐ For the most recent update, we searched the Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group's Specialized Register (latest search 16 October 2020), using the following search terms in title, abstract or keywords: food, calorie restrict*, intake, diet*, body mass index (BMI), Quetelet, waist‐hip ratio (WHR), weight, body‐weight, weight‐changes. At the search date the specialized register included the results of searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled trials (CENTRAL), issue 9, 2020; MEDLINE (including in‐process and Epub ahead of print, via OVID) to update 202000928; Embase (via OVID) to week 2020040; and PsycINFO (via OVID) to update 20200921, as well as online registers of controlled trials.

Searching other resources

Part 2 ‐ We searched the following Cochrane Reviews: Antidepressants for smoking cessation (last updated 2020; Howes 2020); Exercise interventions for smoking cessation (last updated 2019; Ussher 2019); Nicotine replacement therapy for smoking cessation (last updated 2018; Hartmann‐Boyce 2018); Different doses, durations and modes of delivery of nicotine replacement therapy for smoking cessation (last updated 2019; Lindson 2019); Electronic cigarettes for smoking cessation (last updated 2020; Hartmann‐Boyce 2020), and Nicotine receptor partial agonists for smoking cessation (last updated 2016; Cahill 2016). We searched the text of references listed as included studies. For reviews last updated prior to 2019, we also searched the Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group's Specialized Register on 16 October 2020, using the search terms outlined in the individual reviews.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

For the 2020 searches, two review authors (for this update from: JHB, AT, LK, LH, AH and MS) independently screened all titles and abstracts obtained from the search using a piloted screening checklist. Full‐text versions were then independently screened for inclusion. We also ran a 2016 search in which titles and abstracts of records identified were screened in singular by the group's Information Specialist (Lindsay Stead [LS]). Full‐text records were then screened by AF and LS. Any discrepancies about eligibility throughout this update were resolved by discussion or with a third review author. Reasons for exclusion of key studies that required in‐depth discussion are listed in Characteristics of excluded studies.

Data extraction and management

For this update, two review authors (from: JHB, AT, LK, LH, AH, MS, AF, PA, PH, LLJ, DL) independently undertook data extraction using a piloted form. Extractions were then compared and a final version agreed upon following discussion, or with referral to a third review author, when necessary. We extracted the following data for each study:

Study design

Study start and end date

Recruitment

Setting*

Country

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

-

Summary of study participant characteristics

Total number randomized

Number per arm

Total percentage female

Mean age, baseline BMI, baseline weight, cigarettes per day (cpd), Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND) score

Summary of intervention and comparative conditions

Definition of smoking abstinence and type of biochemical validation (if any)

How weight was measured

Number of participants who were abstinent at end of treatment (EOT), 6 months, 12 months and/or at longest follow‐up

Mean weight change (kg) from baseline in abstinent smokers

Abstinence rates (Part 1 studies only)

Adverse events (AEs) and serious adverse events (SAEs) (Part 1 studies only)

Risk of bias in domains specified below

Study funding statement

Author declarations of interest

Any other notes

*studies identified during the 2020 search only.

One review author then entered the data into Review Manager 5 software for analyses (JHB), and another checked them (AT).

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (for this update from: JHB, AT, LK, LH, MS, AF, PA, PH, LLJ, DL) independently assessed the risks of bias for each included study, using the Cochrane risk of bias tool v1 (Higgins 2011). This approach uses a domain‐based evaluation that addresses different areas: random sequence generation; allocation concealment; blinding of participants and personnel; blinding of outcome assessment (smoking and weight); incomplete outcome data; and other potential sources of bias.

Specific considerations about judgements for individual domains for this review are outlined below:

Blinding of participants and personnel: This domain was not evaluated for studies investigating behavioural interventions for smoking cessation where blinding was not possible; this is in accordance with standard guidance from the Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group.

Blinding of outcome assessments (detection bias) were evaluated separately for smoking and weight outcomes, given different considerations for each outcome. Risk of detection bias ratings were based on assessments of both weight and smoking outcomes.

Following standard methods of the Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Review Group, we rated studies at high risk of attrition bias if loss to follow‐up was greater than 50% overall or if there was a difference in follow‐up rates of more than 20% between study arms.

We assigned a grade (low, high, or unclear) for risk of bias for each domain and resolved any disagreements by discussion or by consulting with a third review author. We judged studies to be at high risk of bias overall if they were rated at high risk in at least one domain, and at low risk of bias overall if they were judged to be at low risk across all domains evaluated. We judged the remaining studies to be at unclear risk of bias overall.

Measures of treatment effect

For Part 1, where possible we extracted smoking outcomes as continuous biochemically‐confirmed abstinence, but we accepted less strict definitions if confirmed continuous abstinence was not available. Abstinence rates and their corresponding risk ratio (95% CI) were reported at six and 12 months of follow‐up. We extracted adverse and serious adverse events for pharmacotherapy studies in Part 1 as the number of people experiencing an event, where these data were available. For studies in Part 2, we extracted data on weight change only.

We used the absolute mean (SD) difference in body weight (kgs) from baseline to follow‐up by trial arm as a summary statistic for the treatment effect on weight. We estimated mean weight change only in those abstinent from smoking.

In some studies in Part 1 and 2, more than one trial arm had been compared with a control arm. Where this was the case, we took one of two approaches: where it was inappropriate to combine arms, we analyzed results separately and report them as such. Where appropriate, to create one comparison intervention arm we combined outcome data. For smoking we added together the numerator and denominator from each arm. We calculated weight outcomes from more than one trial arm using the following formulas:

Meanc = ((Mean1*n1)+(Mean2*n2))/(n1+n2) Standard deviation = √varc

√varc= (sumsqc ‐ (nc * (Meanc2)))/(nc‐1)

sumsqc= (((n1‐1)*(var1 + ((n1/n1‐1))*(mean12) + ((n2‐1)*(var2 + ((n2/n2‐1))*(mean22))

Key: Meanc= Combined mean; sumsq = sum of squares; var = variance

Unit of analysis issues

The cluster‐randomized trial included reported results adjusted for intra‐class correlation; we use these adjusted estimates in our analysis. All other trials were individually randomized and hence we did not encounter issues with unit of analysis.

Dealing with missing data

We checked that, for smoking abstinence estimates, participants lost to follow‐up were coded as continuing to smoke and therefore all randomized participants were included in the denominator; if not, we corrected abstinence rates for this. Where weight gain had been measured but not reported at all or in full, we contacted authors or sponsors for clarification. If insufficient data were available for meta‐analysis, we reported results narratively. As outlined below, where possible, we converted data for use in our meta‐analysis.

In some studies mean (SD) weight change by trial arm was not reported in full. When the standard deviations for the changes in body weight were not present, we used several methods to calculate them using standard formulas, depending on the information available. This was mainly derived from confidence intervals and standard errors. To calculate standard deviations of the changes in weight from their associated confidence intervals for studies with a large sample size, we used the following formula:

SD = (√(n) x (upper limit ‐ lower limit)) /standard error

For studies with 95% confidence intervals for difference in means we divided by 3.92 standard errors wide. If sample size was less than 60, the 3.92 standard error wide was replaced with numbers specific to both the t‐distribution and the group sample size minus 1.

To calculate standard deviation from standard error we used the following formula:

SD = SE x √(n)

When the absolute mean differences in body weight were not reported explicitly, we calculated them by subtracting the baseline mean weights from the post‐intervention mean weights for the intervention and control groups. We calculated SDs by using an estimated correlation coefficient of 0.99, which describes how similar the baseline and finishing weight were across participants. This was estimated in abstinent smokers from raw data that we have collected from a trial to prevent weight gain on smoking cessation (Parsons 2009a) and from any other included studies that report standard deviations for mean weight at baseline, final measurement, and changes in means. To estimate the correlation coefficient for the intervention and control groups from other studies reporting starting and finishing means with SDs, we used the following formula:

r = (SD (B)2 + SD (F)2 ‐ SD (C)2) / (2 X SD(B) X SD (F))

(where r = correlation coefficient, SD = standard deviation for the changes in means, B = baseline, F = final measurement, and C = change in mean weight measurement).

The imputed correlation coefficient was used to calculate the missing standard deviations for changes in means for the intervention and control groups by using the following formula:

SD (C) = √((SD (B)2 + SD (F)2) ‐ (2 X r X SD (B) X SD (F))

Assessment of heterogeneity

We used the I2 statistic to investigate statistical heterogeneity, given by the formula [(Q‐df)/Q] x 100%], where Q is the Chi2 statistic and df is its degrees of freedom.

Assessment of reporting biases

We created funnel plots to visually investigate possible publication bias for meta‐analyses with 10 or more studies.

Data synthesis

Smoking cessation outcome data are given based on the number of quitters in the treatment and control groups divided by the total number of participants receiving treatment. Adverse and serious adverse event data are given as the number of people experiencing an event divided by the total number of participants followed up at the relevant time point. Results for both are reported as risk ratios (RRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). A risk ratio greater than 1.0 indicates that more people quit in the treatment group than in the control group, or that more people experienced an adverse event. We used the Mantel‐Haenszel random‐effects method for smoking cessation and adverse event outcomes where appropriate. Weight change outcome data are given as the difference in mean weight change between the intervention and control arms, and we combined estimates using the inverse variance method where appropriate.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Studies were subgrouped based on intervention type.

Sensitivity analysis

Following the standard approach of the Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group, we conducted sensitivity analyses removing studies at high risk of bias.

Summary of findings and assessment of the certainty of the evidence

Following standard Cochrane methodology, we created summary of findings tables for the following comparisons, agreed prior to beginning this update, using GRADEpro GDT:

Weight management education versus no weight intervention

Personalized weight management support versus no weight intervention

Interventions to allay concerns about weight gain versus no weight intervention

Exercise interventions versus no exercise intervention for smoking cessation

Nicotine replacement therapy versus placebo for smoking cessation

Varenicline versus placebo for smoking cessation

Fluoxetine versus placebo for smoking cessation

We selected these comparisons a priori as being the most clinically relevant. In the summary of findings tables, we present data on our primary outcomes (cessation and weight change) for these main comparisons. Also following standard Cochrane methodology, we used the five GRADE considerations (study limitations, consistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness and publication bias) to assess the certainty of the body of evidence for each outcome, and to draw conclusions about the certainty of evidence within the text of the review.

Results

Description of studies

Studies are described by part below. Part 1 represents studies of interventions specifically designed to address post‐cessation weight gain. Part 2 represents studies of smoking cessation interventions not specifically designed to address post‐cessation weight gain.

Results of the search

Part 1

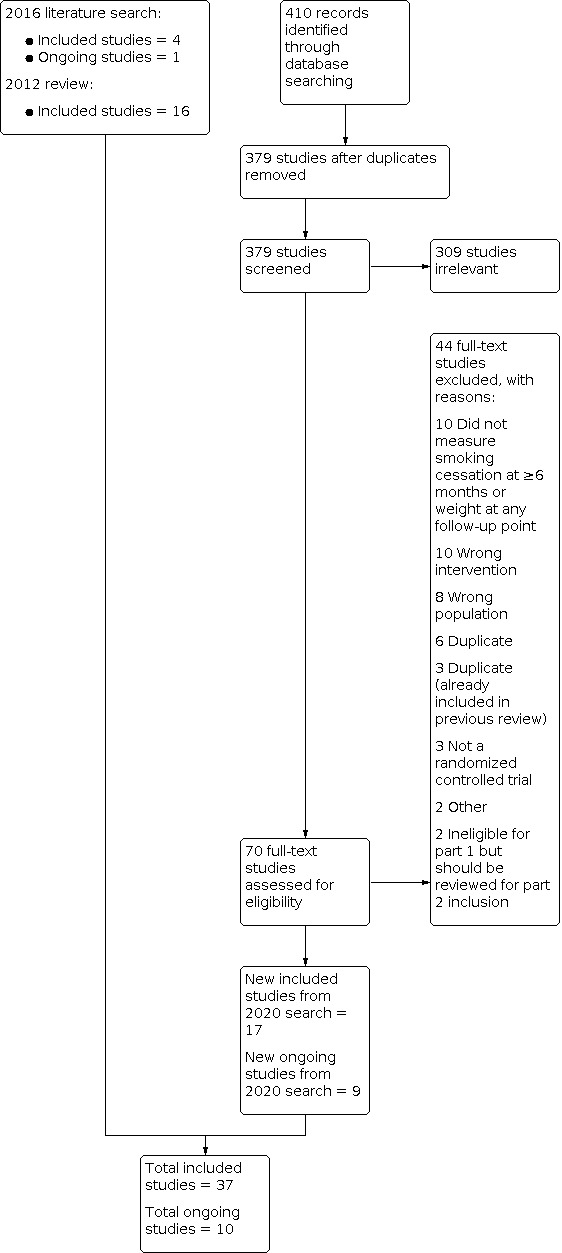

For Part 1 of this update, our 2020 searches identified 379 non‐duplicate references (Figure 1). All references were then screened and 70 full‐text articles were retrieved. For this update, we identified 21 new included studies and 10 new ongoing studies (Characteristics of ongoing studies). In total, we now include 37 studies in Part 1, i.e. 21 new included studies and 16 included studies identified in the 2012 review.

1.

Study flow diagram for Part 1 2020 search plus studies from 2016 search and the 2012 review

Part 2

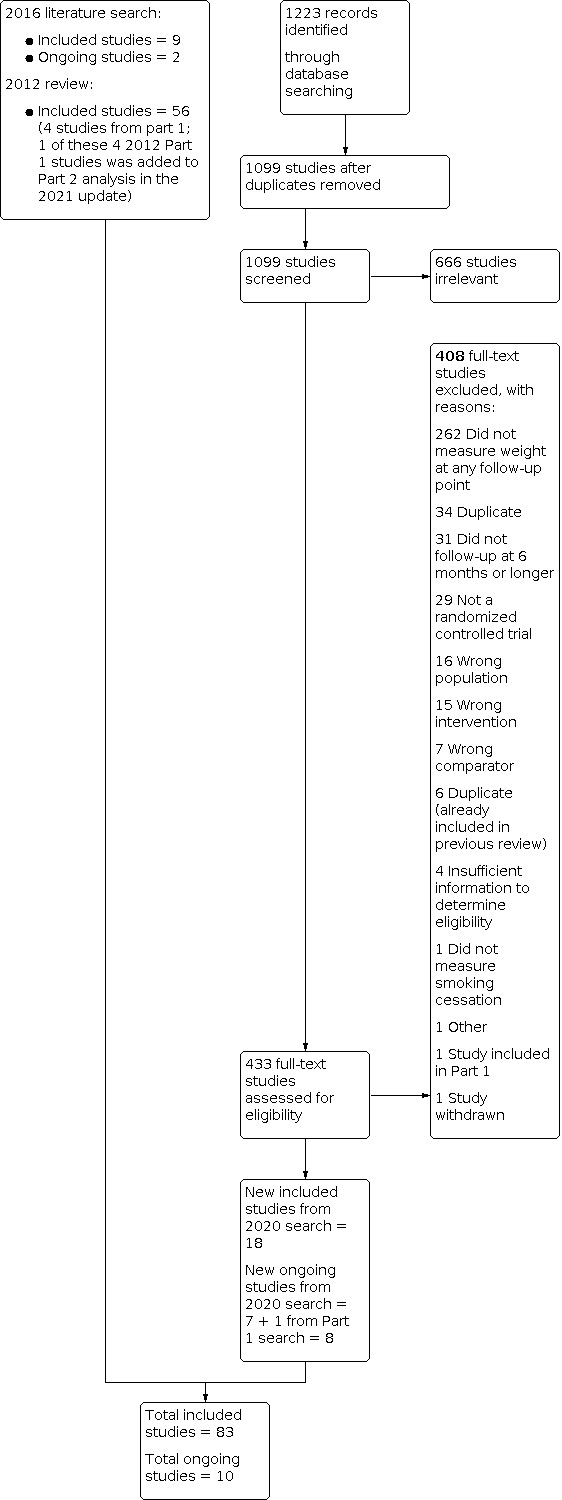

For Part 2 of this update, our 2020 searches identified 1099 non‐duplicate references (Figure 2). All references were then screened and 433 full‐text articles were retrieved. We identified 27 new included studies and 10 new ongoing studies for this update (Characteristics of ongoing studies). In total, we now include 83 studies in Part 2. Four trials are also included in Part 1 that contributed data to Part 2 (1 Cooper 2005 (also Part 2); 1 Levine 2010 (also Part 2); 1 Pirie 1992 (also Part 2); 1 Spring 1995 (also Part 2))

2.

Study flow diagram for Part 2 2020 search plus studies from 2016 search and the 2012 review

Included studies

Main features of studies included in Part 1 and Part 2 are summarized below, and further details on each included study can be found in the Characteristics of included studies table.

Participants

Part 1

A total of 11,514 participants were enrolled in the 37 included studies. Three‐quarters of the studies (27 studies) were undertaken in the USA, three were conducted in England, and one each in Australia, Canada, China, Denmark, Norway, Scotland, and Sweden. A median age of 45.5 years was reported across 27 of the 37 included studies, and a median body mass index (BMI) of 28.5 kg/m2 was reported across the 20 studies which provided these data at baseline. The median percentage of women across 35 studies reporting it was 75.4%, with 14 studies recruiting only women (1 Bloom 2020; 1 Cooper 2005 (also Part 2); 1 Copeland 2006; 1 Copeland 2015; 1 Danielsson 1999; 1 Klesges 1990; 1 Levine 2010 (also Part 2); 1 NCT03528304 2016; 1 Oncken 2019; 1 Perkins 2001; 1 Pirie 1992 (also Part 2); 1 Prapavessis 2018; 1 Spring 1995 (also Part 2); 1 Spring 2004). Participants smoked a median of 20 cigarettes per day at baseline, as reported across 26 studies. A median of 5.2 was scored on the Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence across the 12 studies that reported it.

Part 2

A total of 46,248 participants were enrolled in the 83 studies included in Part 2 of this review. Nearly half of the studies (39 studies) were conducted in the USA, and a further 15 studies were conducted across multiple countries. Four studies each were conducted in Sweden and England, three each in Switzerland and France and two each in Australia and Denmark. A single study was conducted each in Canada, China, Finland, Greece, India, Iceland, New Zealand, Japan, South Africa, Spain and Turkey.

Of the 83 included studies, 64 reported age, median 43 years, and 14 studies reported baseline BMI, median 27.2 kg/m2.The median percentage of women was 55% as reported across 71 studies, with eight of these studies recruiting only women. Participants smoked a median of 22 cigarettes per day at baseline (across 57 studies) and a median of 5.6 was scored on the Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence (22 studies).

Interventions and comparators

Part 1

Behavioural interventions

Twenty‐three studies assessed the effects of a behavioural intervention to prevent weight gain after a smoking cessation attempt.

Three trials examined an intervention consisting of education on weight management (1 Hall 1992; 1 Hankey 2009; 1 Pirie 1992 (also Part 2)) against standard smoking cessation support. Seven trials examined the effects of personalized weight management against usual smoking cessation care (1 Bush 2012; 1 Bush 2018; 1 Johnson 2017; 1 Lycett 2020; 1 Sobell 2017; 1 Spring 2004; 1 Hall 1992). One study tested the efficacy of a very low calorie diet (VLCD), meaning food replacements providing less than 800 kcal/day, where participants in the intervention and control groups both received the weight management education as well as usual smoking cessation support. Both groups were advised to follow a 1600 kcal diet, while the intervention group received two two‐week blocks of a VLCD provided free of charge. Treatment took place in a specialist obesity treatment centre (1 Danielsson 1999). One study compared 16 face‐to‐face one‐hour motivational interviewing and cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT) counselling sessions, given mostly by telephone (1 Baker 2018).

Four studies compared the use of CBT to promote acceptance of moderate weight gain to no behavioural weight advice. (1 Bloom 2020; 1 Levine 2010 (also Part 2); 1 Perkins 2001; 1 White 2019). One of these studies was a three‐arm RCT (1 Perkins 2001) and was also included in the aforementioned comparison on personalized weight management support versus no weight intervention.

Three studies new to this update directly compared behavioural weight management interventions. 1 Prapavessis 2018 tested an exercise maintenance condition with contact control to contact control alone, which included a behavioural weight management component, while 1 Heggen 2016 compared a low‐carbohydrate diet to a moderately reduced‐fat diet. 1 Copeland 2015 compared a minimally‐tailored group intervention which provided information on smoking and weight with a highly tailored, multidisciplinary individual approach, but could not be included in the statistical analysis as no measures of variance were reported alongside weight‐change data.

Five more studies could not be included in the statistical analyses. 1 Oncken 2019 tested the effect of 30 supervised exercise group sessions compared to relaxation group sessions. 1 Vander Weg 2016 compared a Quitline referral to a tailored tobacco intervention in which eligible participants who were worried about weight gain were offered support for weight management. Trial arms of interest in 1 NCT03528304 2016 compared a 16‐week culturally‐tailored contingency management intervention for smoking abstinence and weight loss to no intervention. 1 Lycett 2010 compared a VLCD to an individual dietary and activity‐planning intervention either begun at baseline or at eight weeks post‐quit. Finally, one study compared the effect of group to individual relapse‐prevention follow‐up sessions on smoking cessation and weight change after a two‐week smoking cessation programme (1 Copeland 2006). Results from this study are also reported narratively.

Pharmacological interventions

Fourteen studies compared the effects of pharmacological interventions to placebo on smoking cessation and post‐cessation weight change.

Pharmacological interventions included 8.33 mg phenylpropanolamine gum 16 pieces/day for 8 weeks (1 Cooper 2005 (also Part 2)), 9 pieces/day for 2 weeks (1 Klesges 1990) and up to 10 pieces/day for 4 weeks (1 Klesges 1995); 20 mg ephedrine plus 200 mg caffeine 3/day for 12 weeks (1 Norregaard 1996), 100, 50 and 25 mg/day naltrexone for 6 weeks (1 O'Malley 2006), 50 mg/day naltrexone for 12 weeks (1 King 2012), 25 mg/day naltrexone for 26 weeks (1 Toll 2010), 100 mg/day topiramate (up‐titrated over 5 weeks) for 10 weeks (1 Oncken 2014), 400 mg/day chromium polynicotinate for 14 weeks (1 Parsons 2009) and 30 mg/day dexfenfluramine for 12 weeks (1 Spring 1995 (also Part 2)). This study also examined the efficacy of 40 mg/day of fluoxetine for preventing weight gain (1 Spring 1995 (also Part 2)). As the other fluoxetine studies were included in Part 2 of the reviews, this comparison is described in Part 2.

1 Rose 2019 provided two weeks of lorcaserin or placebo during the two‐week pre‐quit period, followed by an identical treatment regimen of lorcaserin plus a nicotine patch for 12 weeks post‐quit date. Lorcaserin was also tested at 10 mg once or twice daily for 12 weeks in both 1 Shanahan 2017 and 1 Wilcox 2016, but data on the latter study were limited due to extraction from a conference abstract. Finally, 1 Lyu 2018 investigated a combination of adjunctive naltrexone (25 mg/day) and bupropion (300 mg/day) treatment for 24 weeks.

Part 2

Of the 83 included studies, 71 provided sufficient data to include in the meta‐analysis. The outstanding studies were new to this update and measured weight at eligible time points, but data were not provided in a form that we could meta‐analyze.

Of the 71 studies, 34 tested interventions with NRT, 19 with antidepressants, 17 with varenicline, four with exercise and two with electronic cigarettes. Five of these studies included multiple intervention arms or a combination of these interventions.

Nicotine replacement therapy was delivered in various forms, with most studies using a nicotine patch, while other studies delivered nicotine in the form of gum, lozenges, sublingual tablets, inhalers and intranasal spray. Some studies tested patches with varying nicotine dosing regimens, which were assessed separately.

Nineteen studies on antidepressants were included in this review, three of which compared bupropion to varenicline as well as placebo (2 Gonzales 2006; 2 Jorenby 2006; 2 Nides 2006). Overall, 14 studies compared weight change in participants treated with bupropion to placebo (2 Gonzales 2006; 2 Hurt 1997; 2 Jorenby 2006; 2 Nides 2006;2 Piper 2007; 2 Rigotti 2006; 2 Simon 2004; 2 Simon 2009; 2 Uyar 2007; 2 Zellweger 2005; 2 Cox 2012; 2 Eisenberg 2013; 2 Piper 2009; 1 Levine 2010 (also Part 2)). One of these studies (2 Simon 2004) provided a nicotine patch to both the bupropion and placebo study arms, and two additional studies compared varenicline and bupropion to varenicline and placebo (2 Rose 2014; 2 Ebbert 2014). A further two studies compared fluoxetine to placebo (2 Niaura 2002; 2 Saules 2004). 2 Saules 2004 tested fluoxetine versus placebo; both intervention and control arms used NRT, but we included it in the analyses with other fluoxetine‐versus‐placebo studies. One other study examined the efficacy of fluoxetine versus placebo (1 Spring 1995 (also Part 2)). It was not included in the parent Cochrane Review because smoking cessation at six months was not reported, but was identified and included here. All bupropion studies administered 300 mg/day and 2 Hurt 1997 also included a 100 mg/day and 150 mg/day arm. For the main comparison, we use the 300 mg/day arm for 2 Hurt 1997 and we use the lower‐dose arms to compare to the standard 300 mg/day treatment to the lower‐dose arms. Two fluoxetine studies compared two dosing levels (30 mg and 60 mg/day (2 Niaura 2002) and 20 mg and 40 mg/day (2 Saules 2004)) which we combined for the main comparison, while the lower doses and higher doses were compared in a separate comparison to examine for a dose‐dependent effect. One other study examined 40 mg fluoxetine versus placebo (1 Spring 1995 (also Part 2)).

Fourteen studies included in this review compared varenicline to placebo, with some studies including additional intervention components (e.g. patch) which were balanced between study arms. Once again, some studies compared different dosing regimens which were assessed in additional analyses. One study compared 2 mg/daily varenicline to a 21 mg patch tapering to 7 mg (2 Aubin 2008). As mentioned above, 2 Gonzales 2006; 2 Jorenby 2006; 2 Nides 2006 also compared varenicline with bupropion, while 2 Ioakeimidis 2018 compared varenicline with electronic cigarette (12 mg/ml nicotine) use for 12 weeks.

We found no new studies on exercise interventions for smoking cessation for inclusion in this update. In the four original studies, all participants in the treatment arm received an exercise component in parallel with cognitive behavioural treatment for smoking cessation, which was supplemented with nicotine replacement therapy in 2 Ussher 2003 and 2 Bize 2010. The exercise component included supervised exercise in three studies. 2 Marcus 1999 tested three supervised exercise sessions/week for 12 weeks, 30 to 40 minutes resting heart rate plus 60% to 85% heart reserve; 2 Marcus 2005 tested one supervised, four unsupervised exercise sessions/week for eight weeks, at least 30 minutes at resting heart rate plus 45% to 59% heart reserve; and 2 Bize 2010 tested moderate‐intensity (40% to 60% of maximal aerobic power) group‐based cardiovascular (CV) activity under the supervision of a trained monitor for 45 minutes weekly for nine weeks. In contrast, 2 Ussher 2003 compared the effect of seven weeks of exercise counselling to participants receiving a smoking cessation intervention with brief health education.

Finally, two new studies investigated the use of electronic cigarettes. 2 Walker 2020 was a three‐arm RCT comparing a nicotine patch versus nicotine‐containing electronic cigarette plus patch versus nicotine‐free electronic cigarette plus patch. 2 Ioakeimidis 2018, mentioned above,compared varenicline with electronic cigarette (12 mg/ml nicotine) use for 12 weeks.

Further information on dose or length or both of all interventions outlined above are available in the Characteristics of included studies table. Weight change from baseline in all of the studies included in the second part of the review was measured in abstainers only. Definition of abstinence varied between studies as in Part 1, and is also noted in the Characteristics of included studies table. Data for some time points were received following requests made to study authors, which is also noted in the Characteristics of included studies table.

Outcomes

Part 1

Of the 37 included studies:

28 reported data on weight change at end of treatment (EOT), six months, 12 months and/or at the longest follow‐up time point (data for three studies described narratively)

25 reported data on abstinence at EOT, six months, 12 months and/or at the longest follow‐up time point (data for one study are described narratively)

10 pharmacotherapy trials reported adverse or serious adverse outcomes, or both, six of which are described narratively.

Part 2

Of the 83 included studies:

71 reported data on weight change at EOT, six months or 12 months in sufficient detail to be included in the meta‐analysis.

Excluded studies

We list 200 studies excluded at full‐text stage along with reasons in Characteristics of excluded studies. The most common reasons for exclusion in the 2020 search were not measuring any of our outcomes (10 studies) or testing ineligible interventions (10 studies).

Risk of bias in included studies

Part 1: Overall, of the 37 included studies, we judged five studies to be at low risk of bias, 17 to be at unclear risk and the remaining 15 studies at high risk.

Part 2: Of the 83 studies not designed to address post‐cessation weight gain included in Part 2, we judged overall risk of bias to be low for 13 studies, unclear for 46 studies, and high for 24 studies.

Details of risk of bias judgements for each domain of each included study can be found in the Characteristics of included studies table and are illustrated in Figure 3.

3.

Methodological quality summary: review authors' judgements about each methodological quality item for each included study.

Allocation

For Part 1. we judged 10 studies to be at low risk of selection bias, and 27 studies to be at unclear risk of bias mainly due to limited information on allocation concealment.

A similar risk of selection bias for all studies included in Part 2. We judged 27 studies to be at low risk, 55 studies to be at unclear risk of bias, and one study at high risk of bias (2 Jodar‐Sanchez 2018). Most studies were again rated at unclear risk of bias due to insufficient information about allocation concealment.

Blinding

Of the 37 studies included in Part 1, we judged 11 out of 14 pharmacological studies to be at low risk of both performance and detection bias and the remaining three studies at unclear risk of bias. We judged 19 of the 23 behavioural studies to be at low risk of detection bias, one at unclear risk and three at high risk of detection bias; performance bias was not assessed in included studies on behavioural interventions.

Of the 83 studies included in Part 2, 74 tested a pharmacological intervention. Of these 74 studies, 29 were judged to be at low risk of both performance and detection bias, 34 at unclear risk and 11 at high risk. Many of these studies were rated at unclear or high risk of bias due to a lack of blinding when blinding was possible or due to insufficient information about blinding, mainly by not specifying who within the study were blinded. As with Part 1, performance bias was not assessed in the remaining nine behavioural studies included in Part 2. Of these nine studies, eight were judged to be at low risk of detection bias, while one study was rated at unclear risk because it did not specify how weight was measured.

Incomplete outcome data

We rated 16 out of the 37 studies included in Part 1 at low risk of attrition bias. We rated 14 studies with greater than 50% loss to follow‐up overall or a follow‐up difference of more than 20% between study arms, or both, at high risk of attrition bias. The remaining seven studies were judged to at unclear risk.

Similarly, of the 83 studies included in Part 2, most (49 studies) were judged to be at low risk of attrition bias. Twenty‐one studies were rated at unclear risk and 13 studies at high risk.

Other potential sources of bias

No studies in Part 1 were judged to be at unclear or high risk of other bias.

2 Bernard 2015 from Part 2 was rated at unclear risk of other bias as participants in the control group may have participated in exercise (contamination effect).

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3; Table 4; Table 5; Table 6

Part 1

Effects of pharmacological interventions to prevent post‐cessation weight gain versus placebo

Weight change

For three pharmacotherapies, there was evidence of reduced weight gain at end of treatment (EOT), and confidence intervals (CIs) excluded no difference (Analysis 1.1):

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Pharmacological interventions versus placebo for post cessation weight control, Outcome 1: Mean weight change (kg) at end of treatment

Dexfenfluramine: mean difference (MD) −2.50 kg, 95% confidence interval (CI) −2.98 to −2.02; 1 study at high risk of bias, 33 participants

Phenylpropanolamine (PPA): MD −0.50 kg, 95% CI −0.80 to −0.20; I2 = 0%; 3 studies, 112 participants; results not sensitive to removal of one study at high risk of bias

Naltrexone: MD −0.91 kg, 95% CI ‐1.49 to ‐0.34; I2 = 0%; 3 studies, 254 participants; results not sensitive to removal of one study at high risk of bias

For a further three pharmacotherapies, point estimates suggested reduced weight gain at end of treatment, but CIs included the possibility of no difference (Analysis 1.1):

Ephedrine + caffeine: MD −1.30 kg, 95% CI −2.87 to 0.27; 1 study at high risk of bias, 40 participants

Lorcaserin: MD −1.14 kg, 95% CI −3.65 to 1.37; 1 study at low risk of bias, 41 participants

Chromium: MD −0.81 kg, 95% CI −3.05 to 1.43; 1 study at high risk of bias, 15 participants

The one study of topiramate did not have any quitters in the placebo arm and hence an effect estimate could not be calculated (1 Oncken 2014). A further study comparing different treatment regimens of lorcaserin did not provide data by treatment arm (1 Rose 2019).

Four pharmacotherapies were tested in trials that reported at six (Analysis 1.2) and 12 months (Analysis 1.3). All had point estimates suggesting benefit, but only one study contributed data at each time point and in all cases CIs were wide and included no difference:

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Pharmacological interventions versus placebo for post cessation weight control, Outcome 2: Mean weight change (kg) at 6 months

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Pharmacological interventions versus placebo for post cessation weight control, Outcome 3: Mean weight change (kg) at 12 months

PPA 6 months: MD −2.06, 95% CI −5.56 to 1.44; 12 months MD −1.04, 95% CI −5.03 to 2.95; 38 participants; at unclear risk of bias

Ephedrine + caffeine 6 months: MD −0.70 kg, 95% CI −2.72 to 1.32; 32 participants; 12 months MD 1.20 kg, 95% CI −1.84 to 4.24; 24 participants; at unclear risk of bias

Chromium 6 months only: MD −3.87 kg, 95% CI −12.01 to 4.27; 9 participants; at unclear risk of bias

Naltrexone 6 months: MD −0.29 kg, 95% CI −2.23 to 1.65; 68 participants; 12 months MD −2.30 kg, 95% CI −4.92 to 0.32; 61 participants; at unclear risk of bias

Smoking cessation

For studies which measured smoking cessation at six (Analysis 1.4) or 12 months (Analysis 1.5), or both, CIs for all comparisons were wide and included no difference:

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Pharmacological interventions versus placebo for post cessation weight control, Outcome 4: Smoking cessation at 6 months

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Pharmacological interventions versus placebo for post cessation weight control, Outcome 5: Smoking cessation at 12 months

PPA 6 months: RR 1.38, 95% CI 0.76 to 2.53; 12 months RR 1.48, 95% CI 0.80 to 2.73; 1 study at unclear risk of bias, 295 participants

Ephedrine + caffeine 6 months: RR 1.06, 95% CI 0.53 to 2.11; 12 months RR 1.44, 95% CI 0.60 to 3.48; 1 study at unclear risk of bias, 225 participants

Naltrexone 6 months: RR 1.02, 95% CI 0.79 to 1.32; I2 = 0%; 3 studies, 890 participants; removing one at high risk did not impact results; 12 months: RR 1.25, 95% CI 0.67 to 2.31; 1 study at unclear risk of bias, 385 participants

Chromium 6 months only: RR 0.48, 95% CI 0.12 to 1.84; 1 study at unclear risk of bias,143 participants

Naltrexone and bupropion 6 months only: not estimable due to no quitters in either arm; 1 study at unclear risk of bias, 22 participants

Adverse and serious adverse events (SAEs)

For the most part, data were sparsely and heterogeneously reported, often precluding pooled analyses.