Abstract

Adolescence is a period of dramatic developmental transitions -- from puberty-related changes in hormones, bodies, and brains to an increasingly complex social world. The concurrent increase in the onset of many mental disorders has prompted the search for key developmental processes that drive changes in risk for psychopathology during this period of life. Hormonal surges and consequent physical maturation linked to pubertal development in adolescence are believed to impact multiple aspects of brain development, social cognition, and peer relations; each of which have also demonstrated associations with risk for mood and anxiety disorders. These puberty-related effects may combine with other non-pubertal influences on brain maturation to transform adolescents’ social perception and experiences, which in turn continue to shape both mental health and brain development through transactional processes. In this review, we focus on pubertal, neural, and social changes across the duration of adolescence that are known or believed to be related to adolescent-emergent disorders, specifically depression, anxiety, and deliberate self-harm (non-suicidal self-injury). We propose a theoretical model in which social processes (both social cognition and peer relations) are critical to understanding the way in which pubertal development drives neural and psychological changes that produce potential mental health vulnerabilities, particularly (but not exclusively) in adolescent girls.

Keywords: puberty, internalizing, neurodevelopment, social cognition, social connection, social rejection

Adolescence is a period of significant vulnerability to the emergence of mental health disorders.(1) In particular, it is a critical window for the emergence of internalizing (i.e., mood and anxiety) disorders, especially in girls.(2,3) Many theories have been advanced to account for how, when, why, and for whom internalizing symptoms and disorders emerge in adolescence, which spans roughly from the second decade through half of the third decade. Collectively, these approaches consider a wide range of biological, cognitive, and affective aspects of relevant developmental processes including puberty, brain development, cognitive style, emotional reactivity, and psychosocial stress -- and the fundamental role of social factors has often been highlighted.(4–6)

Despite these important theoretical insights, there has been a tendency to examine risk factors independently from each other, despite the acknowledgement that multiple processes operate together to exert deleterious effects on adolescent development. To that end, there is great promise in taking a multilevel and integrative approach, whereby epidemiological and etiological insights combine to identify modifiable risk factors.(7,8) This review focuses on adolescent-emergent internalizing disorders, specifically depression, anxiety, and non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI). We first summarize gender disparities and recent cohort effects in these disorders, which leads to a consideration of the potential prominent role of puberty, a 5–7 year process of neuroendocrine changes that mark the beginning of adolescence and prepare individuals for sexual reproduction. We then review evidence (and pinpoint knowledge gaps) about neural and social changes linked with puberty and internalizing disorders; details about empirical studies cited are cited in Supplementary Material. We propose a conceptual model that integrates across this evidence base, and conclude with suggestions for future research directions.

Growing Gender Disparities in Internalizing Disorders During Adolescence

Meta-analyses show that during adolescence, girls’ risk for depression rises to double or more than that of boys -- a disparity in both symptoms and diagnoses that peaks in mid-late adolescence, and persists across most of the remaining lifespan (for a recent multinational meta-analysis, see (2)). Most worry-related anxiety disorders also have median age of onsets in mid-to-late adolescence; social anxiety, panic, general anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorders all increase from ages 13–18, and girls are also diagnosed with these disorders 2–3x more often than boys.(9–11) Meanwhile, NSSI significantly increases in early adolescence, but continues to emerge well into mid-to-late adolescence, where it exhibits peak prevalence and gender disparities.(12,13) Experiencing a disorder like depression or anxiety in adolescence has high costs; it is associated with greater likelihood of recurrence(14–18) as well as a range of poor long-term outcomes spanning peer and family relationships, physical health problems, health-risking behaviors, and impediments to educational/occupational attainment.(19)

Cohort effects

Layered atop these well-known developmental trajectories, a series of new findings indicate that rates of these adolescent-emergent mental health problems (depressive and anxiety disorders, NSSI, and suicidal thoughts and behaviors) have been increasing worldwide -- especially over the past decade, and most notably amongst girls.(2,20–23) A full examination of possible factors contributing to these cohort effects is beyond the scope of this review, but increases in treatment seeking or primary care diagnoses are unlikely explanations;(24) the social processes discussed in this review may provide one useful starting point for such an analysis. Regardless, this underscores the urgency of identifying mechanisms for these internalizing problems in adolescence as well as the associated gender disparities.

Puberty

Internalizing disorders are known to be associated specifically with pubertal processes rather than with age, suggesting that the relationship is not due solely to psychosocial factors common to individuals at a chronologically-defined stage of adolescence.(25,26) These biological risk factors play out differently for girls and boys.(18,27–29) For example, in girls, earlier pubertal timing and more rapid pubertal tempo (relative to same-age, same-sex peers) is associated with higher rates of depressive disorders in particular, as well as substance use disorders, eating disorders, and antisocial behavior.(30–32) We focus on the gonadarcheal phase of pubertal development instead of the earlier adrenarcheal phase, which is largely about energizing growth (for a review, see (33)). Meanwhile, gonadarcheal development fosters maturation into a sexual being, which incorporates a broader suite of social processes such as negotiating sexual feelings, sensitivity to status, intimate friendships, and romantic relationships.(34,135) Additionally, development of secondary sexual characteristics impact how adolescents are perceived by themselves and others, and may contribute to adultification (when children are perceived as being older and less innocent), particularly for Black girls.(35,36)

There are various theories about why early (or atypical) timing and tempo may produce risk for psychopathology. Some well-known psychosocial hypotheses include maturational-deviance, developmental readiness, risky social contexts, and maturational compression (for a review, see (6)). Maturational-deviance focuses on the risks of off-time development (early and late). In contrast, early-maturing youth in particular may be unprepared (developmental readiness) or overexposed (to risky social contexts). Finally, maturational-compression focuses specifically on faster progression through puberty than peers. These compelling psychosocial explanations would benefit from more explicit connection to neurobiological foundations, given that puberty encompasses both psychosocial and neurobiological changes. Meanwhile, neurobiological approaches have largely emphasized reward and positive valence systems, alone or in conjunction with negative affect and emotion regulation (for reviews, see (11,37–40)). These perspectives have tended to overlook many social processes like self-perception and mentalizing, or to simply subsume social processes within the affective and motivational aspects of experiences like rejection. The present model is an attempt to fill this gap, given that contributions from these other processes and systems have been well detailed elsewhere.

Brain Development

There is a rich literature using animal models to reveal cellular mechanisms for puberty’s effects on brain development, although a full review of this topic is outside the scope of this paper (for a comprehensive review, see (41)). Briefly, gonadal steroids increase to adult levels (primarily estrogen and progesterone in females and testosterone in males, although all three increase in both sexes), and produce changes in adolescents’ bodies and brains. Receptors for these hormones are found throughout the brain, particularly in frontal cortex. Steroids can have long-term effects by regulating gene expression, or acute effects through second messenger cascades. Two key neural processes associated with puberty are dendritic spine turnover, and increased inhibitory neurotransmission. Greater turnover (both loss and gain) of dendritic spines during a 24-hour period in adolescence compared to adulthood likely accommodates neuroplasticity and experience-dependent learning. Ovarian hormones in particular have been linked to the changes in balance of inhibition versus excitation in frontal cortex.

Translating from the animal literature to humans has been a focus in the past decade. A recent systematic review catalogued evidence of associations between puberty and human brain structure (sMRI), function (fMRI), diffusion (DWI), and resting-state functional connectivity (rs-fcMRI).(42) Most studies related brain structure or function to pubertal development when controlling for age, which is akin to modelling pubertal timing (i.e., pubertal stage relative to that of one’s same-age peers). In general, prefrontal cortex structure and function were most frequently linked with puberty. This may tentatively align with the insights about cellular processes discussed above. However, newer studies may refine that understanding. In a recent accelerated longitudinal dataset, pubertal development was found to be a better predictor of subcortical brain volume than age,(43) and subcortical-cortical functional connectivity decreased with advancing pubertal stage in girls, which may reflect altered inhibitory neurotransmission and synaptic pruning with particular impact on fronto-striatal functioning.(44)

Brain development as a mediator of puberty’s impact on adolescent mental health

Despite growing evidence of pairwise puberty-brain associations, few studies have taken the more integrative step of empirically testing whether brain development mediates links between puberty and mental health outcomes. A pair of structural studies found larger pituitary volumes mediated the relationship between early pubertal timing and increased depressive symptoms,(45) as well as between greater dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) levels and social anxiety symptoms.(46) Hippocampal structure also mediated the link between greater testosterone levels for one’s age and depressive symptoms in girls.(47) Meanwhile, a recent large multisite sample of 14-year-olds observed intrinsic functional connectivity (iFC) of key nodes from the default mode network (DMN) decreased with puberty in girls (but increased with puberty in boys); weak connectivity of perigenual ACC in particular was associated with higher internalizing symptoms two years later, although mediation was not tested directly.(48) This last result is particularly relevant given involvement of DMN in social cognition broadly, and perigenual ACC in adolescent self-perception specifically.(49–51)

These initial efforts represent important proofs of concepts, but more needs to be done to identify neural mechanisms of the puberty-internalizing association in adolescence. A number of the extant studies have examined adrenarche and related androgens such as DHEA, but expanding to focus on the gonadal phase of puberty is essential. Diversifying beyond structural metrics of brain maturation will also be particularly important in order to understand how these processes influence brain reactivity to particular classes of stimuli, as well as iFC. Work relating puberty and iFC of the DMN is surprisingly sparse given extensive evidence of the latter’s role in internalizing.(48) Based on the animal and human literature on pubertal-neural associations, we think close attention to frontal cortex (particularly at the midline); the DMN and salience networks; and fronto-striatal connectivity is warranted.(52)

Social Processes

In addition to the neural changes linked to pubertal development, there are significant changes in a host of social processes across adolescence that unfold in tandem with ongoing “social brain” development (including cortical midline structures, temporo-parietal junction, and anterior temporal cortex).(53–56)

Social cognition

There is a substantial literature documenting changes in social cognition (self-perception and mentalizing) across adolescence. One focus has been on change in self-esteem trajectories across adolescence at both the group mean and individual level,(57,58) with pronounced decreases specifically seen in girls.(59) Studies have also documented increases across development in self-consciousness,(60,61) self-complexity,(62,63) and self-disclosure.(64) Other research has suggested that mentalizing (cognitive perspective-taking) also continues to improve, as seen by increased accuracy and decreased reaction time on laboratory mentalizing tasks.(65–67) Adolescents also self-report a greater tendency to take others’ perspectives as they mature, an effect that is stronger for girls than boys.(68)

Social cognition and mental health.

These developmental changes, particularly in self-perception, are thought to impact (and be impacted by) adolescent mental health in transactional relationships over time. Low self-esteem and high self-consciousness are established prospective psychosocial risk factors for adolescent depression.(57,69–71) Several other studies find various facets of self-complexity prospectively predict depressive symptoms in adolescents.(62,63) Furthermore, cognitive models of anxiety (particularly social phobia) propose that both self-focused attention and “construction of the self as a social object” maintain anxiety by increasing negative self-evaluations.(72) Regarding mentalizing, some recent integrative theoretical frameworks point to this as an overlooked contributor to, and consequence of, adolescent mental illness.(8) Empirical evidence on this point is more limited, although one recent study found that poor mentalizing abilities (about emotions and thoughts) may be associated with symptoms of withdrawal/depression in adolescents.(66)

Social cognition and pubertal or neural changes.

There is still limited empirical evidence directly linking puberty and changes in social cognition or its neural substrates, despite prominent theoretical proposals that they are intimately intertwined.(73) One recent study found that increased negative self-evaluations were associated with advanced puberty and severity of depressive symptoms.(74) Neurally, self-reported pubertal stage tracked with an increased response in ventral striatum (VS) during third-person self-evaluation (a process that employs mentalizing to inform self-knowledge);(75) and over a three-year period, greater advancement through puberty associated with greater increases in ventromedial PFC (vmPFC) activity during social self-evaluations.(50) Another study of adolescent girls found anterior temporal cortex activation during social emotion processing (which implicated mentalizing) increased with hormone levels, independent of age.(76) However, we recently observed no association between either age or puberty (self-reported stage or hormone levels) and vmPFC activation during self-evaluation in a well-powered cross-sectional study of early adolescent girls.(77) Furthermore, most neuroimaging studies of social cognition have relied on chronological age to track maturation rather than pubertal stage. For example, increases in vmPFC have been found by age for both physical self-concept(78) and self-consciousness.(79) In contrast, dorsomedial PFC (dmPFC) activation during mentalizing decreases with age.(76,80–82) In sum, most of these studies would benefit from replication in much larger samples, and further incorporation of pubertal or hormonal measures.

Peer relations

It is widely understood that peer relations are a major determinant of well-being and mental health in childhood and adolescence. In this section we focus on three facets of peer relations: peer rejection, close friendships, and romantic or sexual relationships. Together these represent highly salient/emerging developmental tasks in adolescence,(83) reflecting the need to foster social connection with peers and minimize social rejection from them. Of course, the quality of family relationships is also well-known to robustly impact adolescent mental health, such that family support buffers against risk and family conflict augments it,(84–86) and many of the underlying mechanisms described here may apply to family interactions as well.

Peer rejection.

Rejection during adolescence is a powerful threat to mental health.(87) Peer rejection experienced chronically and in the context of power imbalances is known as bullying or victimization, and adolescents who lack social support (especially those who lack a best friend) are more vulnerable to bullying.(88) Being bullied from late childhood through mid-adolescence predicts risk for anxiety disorders through late adolescence and beyond.(89) Similarly, chronic relational victimization is a consistent predictor of adolescent depression, temporally preceding it in many longitudinal studies,(90) and interpersonal stressors, particularly peer rejection, are prominently associated with self-harm.(91,92) For adolescent girls in particular, intentional social exclusion is a common form of relational aggression(93) and a potent risk factor for internalizing problems.(94)

Close friendships.

Although friendships emerge in childhood, building and strengthening close friendships are core developmental tasks of adolescence,(83) and considered uniquely impactful relative to broader markers of acceptance by the peer group.(95) Recent research suggests supportive close friendships can buffer against the harmful consequences of negative family relationships on mental health,(96) and that close friendship strength during adolescence is related to physical and mental health over a decade later.(95,97) In addition, social support from close friends increases self-worth, and buffers the effects of chronic peer rejection on internalizing(87,95,98) and long-term well-being.(99)

But some features of peer relationships, especially in adolescent girls’ close friendships, may exacerbate risk for mental health problems.(100) Notably, even positive features of close friendship quality may be associated with mental health risk, by increasing socialization of depressive symptoms and self-harm behaviors,(101,102) particularly in adolescent girls with a co-ruminative style.(103,104) While self-disclosure to close friends is related to increased intimacy,(105) it can also be related to current and future adolescent depression, as well as deliberate self-harm and suicidality.(69,104,106) Co-rumination, or the tendency to extensively discuss problems in the context of a dyadic relationship, is more frequently seen in girls’ close friendships, and is more strongly related to increases over time in both internalizing symptoms and intimacy in adolescent girls’ friendship dyads than boys’.(104) Taken together, the evidence suggests close friendship quality is typically a protective factor against mental health problems in adolescence, but under certain conditions, close friendships may exacerbate internalizing problems in adolescent girls.

Romantic and sexual relationships.

Romantic relationships represent an emerging developmental task in the latter half of adolescence, with over 70% prevalence by age 17,(107) and provide important learning experiences.(108) Particularly for girls, romantic relationships are initially associated with increased internalizing symptoms, because they are new and stressful experiences.(109) By late adolescence and beyond, however, romantic relationships frequently provide intimacy and support that exceeds that of close friends.(110) Although in adolescence sexual activities are most frequently pursued in the context of romantic relationships, having sex outside of romantic relationships is increasingly frequent;(111) these sexual, non-romantic relationships can include “friends with benefits” and sometimes produce distress if they do not evolve into romantic relationships.(112) Some features of romantic and sexual relationships (e.g., poor quality relationships, breakups) are strongly associated with adolescent mental health outcomes.(113) This ranges from depressive symptoms, particularly in girls,(109,114) to self-harm and suicide risk.(115–117) In these studies, the experience of being rejected has been found to be a particularly salient relationship stressor that acts as a precipitant of mental health problems.

Peer relations and brain development.

One of the most extensive lines of research in developmental social neuroscience has focused on neural responses to experiences of social exclusion, including in adolescents with internalizing disorders. Many studies use the virtual ball-tossing game Cyberball (118–121) or other interactive paradigms with adolescents (Chatroom, Virtual School)(39,122,123) to assess neural responses to ostensible experiences of acute social exclusion or social evaluation (rejection and acceptance feedback) by peers. Collectively, these studies demonstrate consistent evidence of engagement in subgenual ACC (sgACC), vlPFC, posterior midline regions, and ventral striatum (for a meta-analysis, see (124)); the paradigms that look at anticipation/receipt of social evaluative feedback additionally elicit responses in amygdala and medial orbitofrontal cortex.(39,122,123,125) A few studies suggested activity in these regions produced by social exclusion or rejection feedback was associated with pubertal development,(121,123) or predicted future depressive symptoms,(120) but more work is needed to integrate across pubertal, neural, social, and internalizing processes. The anterior insula, part of the salience network, has also been implicated in atypical responses to social exclusion in depression(123,126) and anxiety,(127) but the direction of effects has been mixed. In comparison to both depressed adolescents and healthy controls, adolescents who engage in self-harm likewise exhibit group differences responses to social exclusion in mPFC, vlPFC, striatum, and insula.(128,129)

Compared to this body of work, we know relatively little about how brain development relates to positive aspects of social connection, like close friendships. However, one recent study found that friendship buffers affective and neural responses to social exclusion in adolescents who experienced early adversity.(130) Another recent study showed choosing to self-disclose about intimate information to a close friend was associated with increased activity in regions associated with social cognition and emotion regulation, including vmPFC, for adolescent girls.(131) There is likewise very little information about neural changes accommodating the emergence of romantic or sexual relationships in adolescence, and the few neuroimaging studies in this area mainly focus on sexual risk-taking.(34)

Peer relations and puberty.

In contrast to its under-examined associations with brain development, romantic and sexual relationships are frequently characterized as a salient consequence of puberty.(132) Adolescent romantic relationships and behaviors are qualitatively different than the feelings pre-pubescent children can have towards their peers;(110,133) testosterone and estradiol seem to underlie some of that romantic interest.(134) Importantly, although sexual reproduction can be considered the ultimate evolutionary target of pubertal development, reproductive success encompasses a much broader range of social processes than sexual reproductive capacity per se.(34,135) In this sense, romantic and sexual relationships represent a primary and highly developmentally salient context in which the social changes of adolescence reveal themselves. In contrast to this work on romantic/sexual relationships, there is a relative dearth of information relating close friendships to pubertal development, although one study found early-maturing girls to be more likely to experience dissolution of a friendship.(136) Work in this area tends to look at puberty’s relations to a broader category of peer stress.(137) Peer rejection is one type of peer stressor in this category. Much of the work on peer rejection and puberty has typically investigated the latter as a moderator of the association between social victimization and mental health, consistent with the contextual amplification model, which posits that off-time maturation acts to amplify the negative impact of stressful social contexts.(138,139)

Conceptual Model

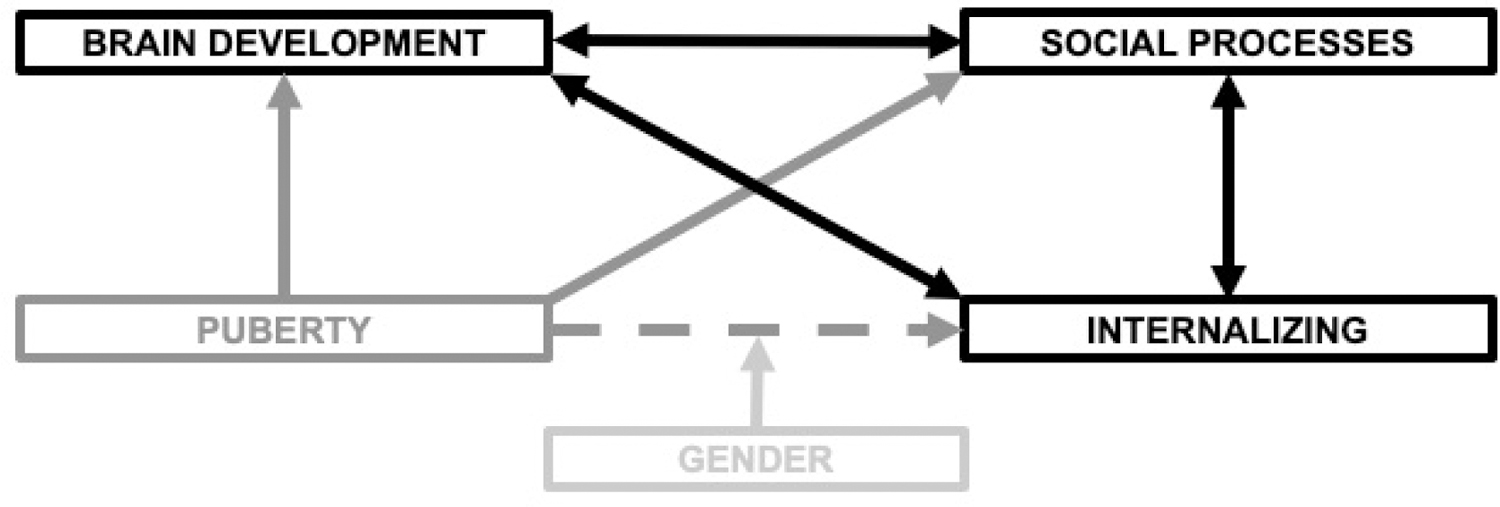

The literature reviewed above suggests there is a convincing pattern of associations between puberty, brain development, social processes (social cognition and peer relations) and adolescent-emergent internalizing disorders. Our model proposes that puberty dramatically alters adolescents’ social perceptions and experiences with peers. It does so via physical, neural, and interpersonal changes that reshape how adolescents see themselves, and how they interact with others. Thus in contrast to contextual amplification theory(138) which casts puberty in a moderating role, we propose direct and indirect effects of pubertal (and neural) changes on social processes and mental health (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Heuristic conceptual model of neural and social mechanisms for the impact of pubertal development on adolescent mental health. The dashed arrow represents mediation of the puberty-internalizing link via neural and social mechanisms. Double-headed arrows represent transactional processes unfolding over time across adolescence. Gender is depicted as a known moderator of the puberty-internalizing link; it is expected to moderate the other paths in this model (e.g., puberty-brain development, puberty-social processes, social processes-internalizing) but these are not depicted for clarity’s sake. Note that neither the brain’s initial trigger of puberty, nor social experiences that affect pubertal timing such as early life adversity, are depicted here as double-headed arrows due to the specific focus on processes happening throughout adolescence.

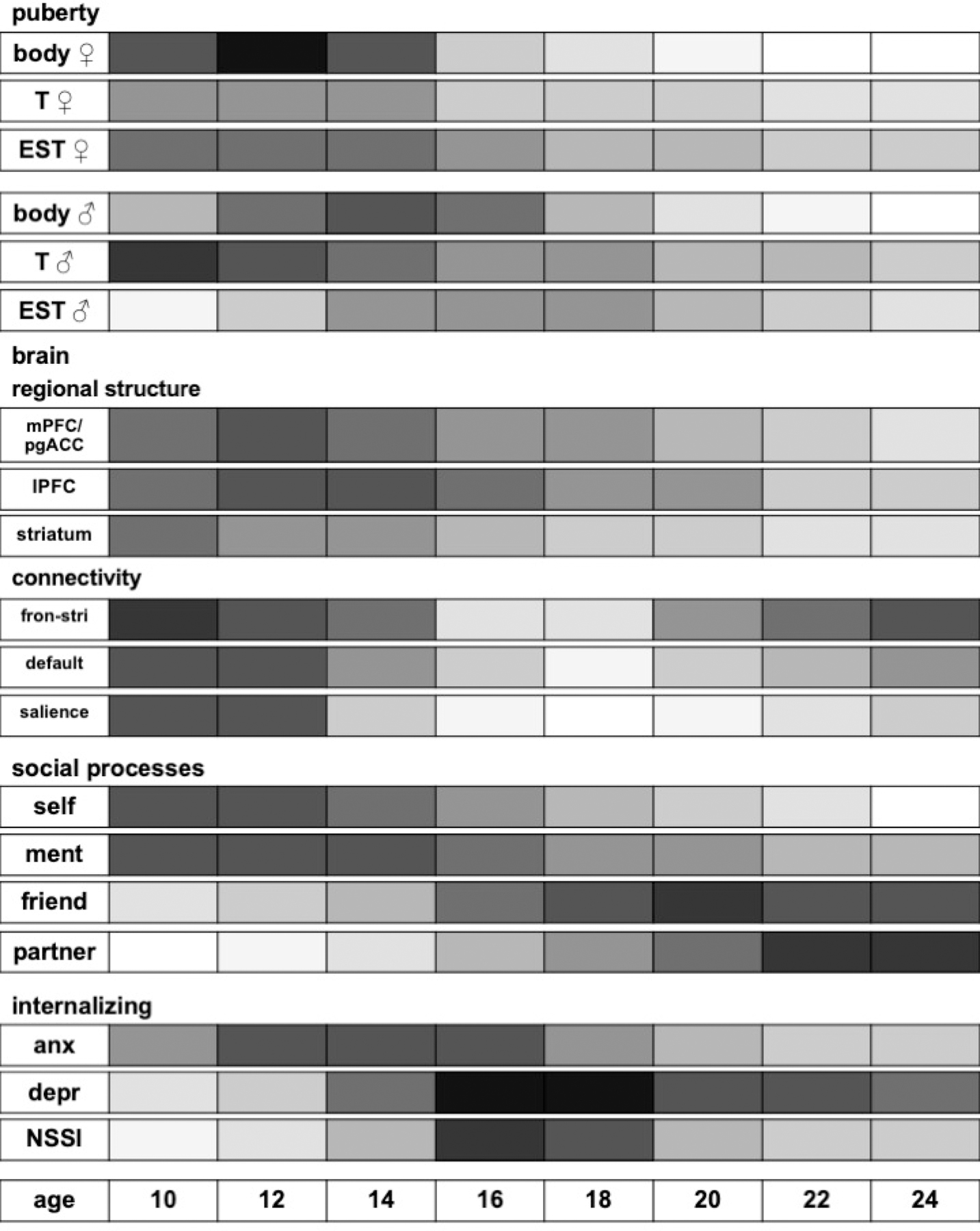

Another central feature of our model is a consideration of how social, neural, and pubertal processes co-evolve across the duration of adolescence (see Figure 2 for alignment of these processes with mental health trajectories). For example, most significant changes in secondary sexual characteristics finish in mid-adolescence, but hormone levels continue to rise through late adolescence, just as do changes in brain structure, function, and connectivity. In the social sphere, early adolescence is characterized by changes in self-perception, as well as an emphasis on avoiding social rejection by the peer group. By middle adolescence, more advanced perspective-taking tendencies and mentalizing abilities largely plateau, except for in some very complex or highly recursive tasks. At this time new forms of social connection with peers emerge, namely romantic and sexual relationships, and through late adolescence they play increasingly prominent roles as sources of support and contexts of important learning experiences. These social developmental trajectories shape the unfolding of transactional processes in our model across the second decade of life.

Figure 2.

This chart depicts the degree of dynamic developmental relevance for each process or system, aligned by chronological age. The values were determined by qualitatively aggregating from the literature referenced in our manuscript, including empirical studies reported on in reviews we cited. Each bar represents a two-year age window across adolescence, from 10–11 years to 24–25 years. Color is saturated in 10% intervals ranging from 0% to 100% saturation (low to high plasticity, respectively). For example, the rapid development of secondary sex characteristics (bodily changes) in early to mid adolescence are conveyed by the highly saturated values during those age windows. Saturation values do NOT represent levels or prevalence rates of the process or system. For example, the slope of increase in testosterone is steepest in early adolescence, as represented by high saturation values, even though absolute levels of testosterone do not peak at the youngest ages. We note that the emphasis is on the relevance of each process or system in developmental tasks across an age cohort, rather than on an individual level. In other words, testosterone remains influential on social behavior in late adolescence and beyond, but this is due to individual differences rather than development. We also note that there are well-documented shifts in pubertal timing such that some racial/ethnic identity minority adolescents (Black and Latinx) enter puberty earlier than others (non-Latinx White and Asian). Finally, in contrast to pubertal processes and internalizing, saturation values for resting-state functional connectivity networks (default mode, salience) and social processes were heavily based on cross-sectional studies and therefore caution is warranted during interpretation until these patterns are confirmed in longitudinal samples. T = testosterone, EST = estrogen, mPFC = medial prefrontal cortex, pgACC = perigenual anterior cingulate cortex, lPFC = lateral prefrontal cortex, fron-stri = frontostriatal connectivity, default = default mode network, salience = salience (cingulo-opercular) network, ment = mentalizing, friend = close friendships, partner = romantic and sexual relationships, anx = worry-based anxiety disorders, depr = depression, NSSI = non-suicidal self-injury.

Each social advance sets the tone for subsequent changes -- social cognitive predispositions adjust the probability of success or failure in peer relations, and the resulting social experiences also shape the brain and impact mental health. In other words, social experiences across adolescence are not only predictive of concurrent and near-future mental health, but also part of a cascading series of developmental and risk processes that are at least in part driven by earlier biological and psychosocial changes. Through such interactions this dynamic system can augment or buffer against risk for mood and anxiety disorders. While these neural and social consequences of puberty for internalizing may be most pronounced in girls, they are still expected to impact boys.

For this work to progress our scientific models must have testable, falsifiable hypotheses.(140) Key examples of testable and falsifiable hypotheses in our integrative model include: i) features of brain development or social processes mediate the association between pubertal development and internalizing; ii) there are specific temporal sequences to these effects, particularly social ones (e.g., that self and social cognition related processes have greater impact in early to middle adolescence, while close friendships or romantic relationships have greater impact in late adolescence); and iii) these effects proceed along specific paths (e.g., that competing mediations through puberty within the adolescent period are not supported). While some of these have begun to be tested as reviewed above, many require special types of designs (e.g., longitudinal) to be adequately evaluated.

Future Directions

One future direction with strong implications for both mental health and social processes is to understand the role that digital devices and social media play in these processes -- a pressing question to which individuals, families, schools, policy makers, legislators, and digital designers are all demanding answers.(20) However, the scientific literature on this topic to date has generally been of mixed quality and conclusions.(141) Of course, one of the key functions of digital technology for adolescents in particular is social connection via social media and other communication platforms. As such, an especially important consideration is how social connection is experienced in the context of digital technology and social media, and how this might influence mental health in light of the material reviewed previously about the dual-edged nature of close relationships.

In addition, the biological changes of adolescence do not cease when puberty concludes; rather, the brain continues to exhibit change in structure and function across the entire duration of adolescence, reaching developmental asymptotes largely in the mid-twenties.(142) Despite the completion of many of the morphological changes associated with puberty-related development of secondary sexual characteristics, rendering self-report metrics ineffective, hormone levels continue to rise across the same extended period as brain development.(33) These ongoing increases in sex hormones are also believed to shape and refine neural circuitry as well as drive many late-maturing events not captured by categorical Tanner stages. In this respect, hormone levels may serve as a better index of maturation to incorporate during the latter half of adolescence, as well as a measure of individual differences relating to social changes and mental health.(42)

While neuroimaging studies have increasingly assayed sex hormones, many studies relating puberty to mental health draw on large, nationally representative samples that are typically limited to self-report and thus unable to examine later contributions of hormonal changes. This limitation is counterbalanced by the ability of nationally representative studies to contextualize these associations across sex and ethnicity, something that most neuroimaging work has yet to be able to do. We hope a move towards more multilevel, longitudinal work will make progress towards these open questions, which is happening in medium-sized cohorts (Ns~100–300),(143) as well as large ones (Ns>1000s).(144,145) A trend we hope spreads widely is for studies to harmonize data collection efforts, with an aim to truly complement and inform each other. For example, medium and smaller-sized studies may be more nimble and suited to achieve deep phenotyping, while larger studies contribute breadth and generalizability.

Finally, pubertal-social-internalizing links have been more extensively studied in girls, which clearly calls for more work to understand these interactions in boys. For example, there is mixed evidence on whether and how atypical tempo or timing of pubertal maturation may impact boys’ mental health; it may have different negative consequences than for girls, possibly oriented more towards externalizing.(146,147) One reason for the lagging understanding of these processes in boys is that measuring puberty via the oft-used self-report scales may be less precise for boys than girls.(148) As noted in the legend of Figure 1, future research should explore which of the potential moderating influences of gender are fundamental (i.e., mechanistic) versus epiphenomenal.

Conclusion

The evidence presented in this review suggests puberty launches a concert of neural and social changes that individually and together affect adolescent propensity for internalizing disorders, particularly for girls. Over time, these neural, social, and mental health processes interact in a transactional manner to mutually shape trajectories of risk or resilience. A major goal of our proposed model is to highlight the central role of social processes, particularly related to the progression of changes from social cognition to social connection. Incorporating a focus on social processes across different phases of adolescence in these multilevel studies is a high priority for future research, particularly in studies using biomarkers of neural or pubertal development. To truly advance the field, we should endeavor to design integrative approaches that measure these domains across multiple levels and within individuals over time.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This review and the conceptual model were developed in and with the support of the Transitions in Adolescent Girls (TAG) Study, funded by the National Institute of Mental Health (R01 MH104718; PI Pfeifer).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Financial Disclosures

Dr. Pfeifer reports no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest. Dr. Allen has an equity interest in Ksana Health, Inc., for which he is the co-founder and CEO.

References

- 1.Kessler RC, Amminger GP, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Alonso J, Lee S, Ustün TB (2007): Age of onset of mental disorders: a review of recent literature. Curr Opin Psychiatry 20: 359–364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Salk RH, Hyde JS, Abramson LY (2017): Gender Differences in Depression in Representative National Samples: Meta-Analyses of Diagnoses and Symptoms. Psychol Bull 143: 783–822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hankin BL, Abramson LY, Moffitt TE, Silva PA, McGee R, Angell KE (1998): Development of depression from preadolescence to young adulthood: emerging gender differences in a 10-year longitudinal study. J Abnorm Psychol 107: 128–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hyde JS, Mezulis AH, Abramson LY (2008): The ABCs of depression: Integrating affective, biological, and cognitive models to explain the emergence of the gender difference in depression. Psychological Review 115: 291–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nolen-Hoeksema S (2001): Gender Differences in Depression. Curr Dir Psychol Sci 10: 173–176. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rudolph KD (2014): Puberty as a Developmental Context of Risk for Psychopathology. In: Lewis M, Rudolph KD, editors. Handbook of Developmental Psychopathology. Boston, MA: Springer US, pp 331–354. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Allen NB, Dahl RE (2015): Multi-Level Models of Internalizing Disorders and Translational Developmental Science: Seeking Etiological Insights that can Inform Early Intervention Strategies. J Abnorm Child Psychol 43: 875–883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Luyten P, Fonagy P (2018): The stress–reward–mentalizing model of depression: An integrative developmental cascade approach to child and adolescent depressive disorder based on the Research Domain Criteria (RDoC) approach. Clinical Psychology Review 64: 87–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beesdo K, Knappe S, Pine DS (2009): Anxiety and Anxiety Disorders in Children and Adolescents: Developmental Issues and Implications for DSM-V. Psychiatr Clin North Am 32: 483–524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beesdo-Baum K, Knappe S (2012): Developmental Epidemiology of Anxiety Disorders. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America 21: 457–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Caouette JD, Guyer AE (2013): Gaining insight into adolescent vulnerability for social anxiety from developmental cognitive neuroscience. Dev Cogn Neurosci 8: 65–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hawton K, Saunders KE, O’Connor RC (2012): Self-harm and suicide in adolescents. The Lancet 379: 2373–2382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moran P, Coffey C, Romaniuk H, Olsson C, Borschmann R, Carlin JB, Patton GC (2012): The natural history of self-harm from adolescence to young adulthood: a population-based cohort study. The Lancet 379: 236–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Essau CA, Lewinsohn PM, Olaya B, Seeley JR (2014): Anxiety disorders in adolescents and psychosocial outcomes at age 30. Journal of Affective Disorders 163: 125–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lewinsohn PM, Allen NB, Seeley JR, Gotlib IH (1999): First onset versus recurrence of depression: differential processes of psychosocial risk. J Abnorm Psychol 108: 483–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mendle J, Ryan RM, McKone KMP (2018): Age at Menarche, Depression, and Antisocial Behavior in Adulthood. Pediatrics 141. 10.1542/peds.2017-1703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ohannessian CM, Milan S, Vannucci A (2017): Gender Differences in Anxiety Trajectories from Middle to Late Adolescence. J Youth Adolescence 46: 826–839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Patton GC, Coffey C, Romaniuk H, Mackinnon A, Carlin JB, Degenhardt L, et al. (2014): The prognosis of common mental disorders in adolescents: a 14-year prospective cohort study. The Lancet 383: 1404–1411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Birmaher B, Arbelaez C, Brent D (2002): Course and outcome of child and adolescent major depressive disorder. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am 11: 619–637, x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haidt J, Allen N (2020): Scrutinizing the effects of digital technology on mental health. Nature 578: 226–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Keyes KM, Gary D, O’Malley PM, Hamilton A, Schulenberg J (2019): Recent increases in depressive symptoms among US adolescents: trends from 1991 to 2018. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 54: 987–996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Duffy ME, Twenge JM, Joiner TE (2019): Trends in Mood and Anxiety Symptoms and Suicide-Related Outcomes Among U.S. Undergraduates, 2007–2018: Evidence From Two National Surveys. Journal of Adolescent Health 65: 590–598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Twenge JM, Cooper AB, Joiner TE, Duffy ME, Binau SG (2019): Age, period, and cohort trends in mood disorder indicators and suicide-related outcomes in a nationally representative dataset, 2005–2017. Journal of Abnormal Psychology 128: 185–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mojtabai R, Olfson M, Han B (2016): National Trends in the Prevalence and Treatment of Depression in Adolescents and Young Adults. Pediatrics 138. 10.1542/peds.2016-1878 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Patton GC, Hemphill SA, Beyers JM, Bond L, Toumbourou JW, McMORRIS BJ, Catalano RF (2007): Pubertal stage and deliberate self-harm in adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 46: 508–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Patton GC, Olsson C, Bond L, Toumbourou JW, Carlin JB, Hemphill SA, Catalano RF (2008): Predicting female depression across puberty: a two-nation longitudinal study. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 47: 1424–1432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Graber JA (2013): Pubertal timing and the development of psychopathology in adolescence and beyond. Hormones and Behavior 64: 262–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mendle J, Harden KP, Brooks-Gunn J, Graber JA (2010): Development’s Tortoise and Hare: Pubertal Timing, Pubertal Tempo, and Depressive Symptoms in Boys and Girls. Dev Psychol 46: 1341–1353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Negriff S, Susman EJ (2011): Pubertal timing, depression, and externalizing problems: A framework, review, and examination of gender differences. Journal of Research on Adolescence 21: 717–746. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Graber JA (2013): Pubertal timing and the development of psychopathology in adolescence and beyond. Hormones and Behavior 64: 262–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marceau K, Ram N, Houts RM, Grimm KJ, Susman EJ (2011): Individual Differences in Boys’ and Girls’ Timing and Tempo of Puberty: Modeling Development With Nonlinear Growth Models. Dev Psychol 47: 1389–1409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mendle J, Harden KP, Brooks-Gunn J, Graber JA (2010): Development’s Tortoise and Hare: Pubertal Timing, Pubertal Tempo, and Depressive Symptoms in Boys and Girls. Developmental Psychology 46: 1341–1353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Byrne ML, Whittle S, Vijayakumar N, Dennison M, Simmons JG, Allen NB (2017): A systematic review of adrenarche as a sensitive period in neurobiological development and mental health. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience 25: 12–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Suleiman AB, Galván A, Harden KP, Dahl RE (2017): Becoming a sexual being: The ‘elephant in the room’ of adolescent brain development. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience 25: 209–220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Epstein R, Blake J, González T (2017): Girlhood Interrupted: The Erasure of Black Girls’ Childhood. Rochester, NY: Social Science Research Network. 10.2139/ssrn.3000695 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mendle J, Koch MK (2019): The Psychology of Puberty: What Aren’t We Studying That We Should? Child Development Perspectives 13: 166–172. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Forbes EE, Dahl RE (2010): Pubertal development and behavior: Hormonal activation of social and motivational tendencies. Brain and Cognition 72: 66–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nielson DM, Keren H, O’Callaghan G, Jackson SM, Douka I, Zheng CY, et al. (2020): Great Expectations: A Critical Review of and Recommendations for the study of Reward Processing as a Cause and Predictor of Depression. Biological Psychiatry. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2020.06.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Guyer AE, Silk JS, Nelson EE (2016): The neurobiology of the emotional adolescent: From the inside out. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 70: 74–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Young KS, Sandman CF, Craske MG (2019): Positive and Negative Emotion Regulation in Adolescence: Links to Anxiety and Depression. Brain Sci 9. 10.3390/brainsci9040076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Piekarski DJ, Johnson CM, Boivin JR, Thomas AW, Lin WC, Delevich K, et al. (2017): Does puberty mark a transition in sensitive periods for plasticity in the associative neocortex? Brain Research 1654: 123–144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vijayakumar N, Op de Macks Z, Shirtcliff EA, Pfeifer JH (2018): Puberty and the human brain: Insights into adolescent development. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 92: 417–436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wierenga LM, Bos MGN, Schreuders E, vd Kamp F, Peper JS, Tamnes CK, Crone EA (2018): Unraveling age, puberty and testosterone effects on subcortical brain development across adolescence. Psychoneuroendocrinology 91: 105–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Duijvenvoorde ACK van, Westhoff B, Vos F de, Wierenga LM, Crone EA (n.d.): A three-wave longitudinal study of subcortical–cortical resting-state connectivity in adolescence: Testing age- and puberty-related changes. Human Brain Mapping 0. 10.1002/hbm.24630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Whittle S, Yücel M, Lorenzetti V, Byrne ML, Simmons JG, Wood SJ, et al. (2012): Pituitary volume mediates the relationship between pubertal timing and depressive symptoms during adolescence. Psychoneuroendocrinology 37: 881–891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Murray CR, Simmons JG, Allen NB, Byrne ML, Mundy LK, Seal ML, et al. (2016): Associations between dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) levels, pituitary volume, and social anxiety in children. Psychoneuroendocrinology 64: 31–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ellis R, Fernandes A, Simmons JG, Mundy L, Patton G, Allen NB, Whittle S (2019): Relationships between adrenarcheal hormones, hippocampal volumes and depressive symptoms in children. Psychoneuroendocrinology 104: 55–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ernst M, Benson B, Artiges E, Gorka AX, Lemaitre H, Lago T, et al. (2019): Pubertal maturation and sex effects on the default-mode network connectivity implicated in mood dysregulation. Translational Psychiatry 9: 103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Andrews-Hanna JR, Smallwood J, Spreng RN (2014): The default network and self-generated thought: component processes, dynamic control, and clinical relevance: The brain’s default network. Ann NY Acad Sci 1316: 29–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pfeifer JH, Kahn LE, Merchant JS, Peake SJ, Veroude K, Masten CL, et al. (2013): Longitudinal Change in the Neural Bases of Adolescent Social Self-Evaluations: Effects of Age and Pubertal Development. J Neurosci 33: 7415–7419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pfeifer JH, Berkman ET (2018): The Development of Self and Identity in Adolescence: Neural Evidence and Implications for a Value-Based Choice Perspective on Motivated Behavior. Child Development Perspectives 12: 158–164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Menon V (2011): Large-scale brain networks and psychopathology: a unifying triple network model. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 15: 483–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Blakemore S-J, Mills KL (2014): Is Adolescence a Sensitive Period for Sociocultural Processing? Annual Review of Psychology 65: 187–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kilford EJ, Garrett E, Blakemore S-J (2016): The development of social cognition in adolescence: An integrated perspective. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 70: 106–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lamblin M, Murawski C, Whittle S, Fornito A (2017): Social connectedness, mental health and the adolescent brain. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 80: 57–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mills KL, Lalonde F, Clasen LS, Giedd JN, Blakemore S-J (2014): Developmental changes in the structure of the social brain in late childhood and adolescence. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci 9: 123–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Birkeland MS, Melkevik O, Holsen I, Wold B (2012): Trajectories of global self-esteem development during adolescence. Journal of Adolescence 35: 43–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Robins RW, Trzesniewski KH, Tracy JL, Gosling SD, Potter J (2002): Global self-esteem across the life span. Psychol Aging 17: 423–434. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Baldwin SA, Hoffmann JP (2002): The Dynamics of Self-Esteem: A Growth-Curve Analysis. Journal of Youth and Adolescence 31: 101–113. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rankin JL, Lane DJ, Gibbons FX, Gerrard M (2004): Adolescent Self-Consciousness: Longitudinal Age Changes and Gender Differences in Two Cohorts. Journal of Research on Adolescence 14: 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Takishima-Lacasa JY, Higa-McMillan CK, Ebesutani C, Smith RL, Chorpita BF (2014): Self-consciousness and social anxiety in youth: the Revised Self-Consciousness Scales for Children. Psychol Assess 26: 1292–1306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Abela JRZ, Véronneau-McArdle M-H (2002): The relationship between self-complexity and depressive symptoms in third and seventh grade children: a short-term longitudinal study. J Abnorm Child Psychol 30: 155–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cohen JR, Spiegler KM, Young JF, Hankin BL, Abela JRZ (2014): Self-Structures, Negative Events, and Adolescent Depression: Clarifying the Role of Self-Complexity in a Prospective, Multiwave Study. J Early Adolesc 34: 736–759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Vijayakumar N, Pfeifer JH (2020): Self-disclosure during adolescence: exploring the means, targets, and types of personal exchanges. Current Opinion in Psychology 31: 135–140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dumontheil I, Apperly IA, Blakemore S-J (2010): Online usage of theory of mind continues to develop in late adolescence. Dev Sci 13: 331–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Poznyak E, Morosan L, Perroud N, Speranza M, Badoud D, Debbané M (2019): Roles of age, gender and psychological difficulties in adolescent mentalizing. Journal of Adolescence 74: 120–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Symeonidou I, Dumontheil I, Chow W-Y, Breheny R (2016): Development of online use of theory of mind during adolescence: An eye-tracking study. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology 149: 81–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Van der Graaff J, Branje S, De Wied M, Hawk S, Van Lier P, Meeus W (2014): Perspective taking and empathic concern in adolescence: Gender differences in developmental changes. Developmental Psychology 50: 881–888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hankin BL, Stone L, Wright PA (2010): Corumination, interpersonal stress generation, and internalizing symptoms: accumulating effects and transactional influences in a multiwave study of adolescents. Dev Psychopathol 22: 217–235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lewinsohn PM, Pettit JW, Joiner TE, Seeley JR (2003): The symptomatic expression of major depressive disorder in adolescents and young adults. J Abnorm Psychol 112: 244–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Orth U, Robins RW, Roberts BW (2008): Low self-esteem prospectively predicts depression in adolescence and young adulthood. J Pers Soc Psychol 95: 695–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Haller SPW, Cohen Kadosh K, Scerif G, Lau JYF (2015): Social anxiety disorder in adolescence: How developmental cognitive neuroscience findings may shape understanding and interventions for psychopathology. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience 13: 11–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kilford EJ, Garrett E, Blakemore S-J (2016): The development of social cognition in adolescence: An integrated perspective. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 70: 106–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ke T, Wu J, Willner CJ, Brown Z, Crowley MJ (2018): Adolescent positive self, negative self: associated but dissociable? Journal of Child & Adolescent Mental Health 30: 203–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Jankowski KF, Moore WE, Merchant JS, Kahn LE, Pfeifer JH (2014): But do you think I’m cool?: Developmental differences in striatal recruitment during direct and reflected social self-evaluations. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience 8: 40–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Goddings A-L, Heyes SB, Bird G, Viner RM, Blakemore S-J (2012): The relationship between puberty and social emotion processing. Developmental Science 15: 801–811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Barendse MEA, Cosme D, Flournoy JC, Vijayakumar N, Cheng TW, Allen NB, Pfeifer JH (2020): Neural correlates of self-evaluation in relation to age and pubertal development in early adolescent girls. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience 44: 100799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.van der Cruijsen R, Peters S, van der Aar LPE, Crone EA (2018): The neural signature of self-concept development in adolescence: The role of domain and valence distinctions. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience 30: 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Somerville LH, Jones RM, Ruberry EJ, Dyke JP, Glover G, Casey BJ (2013): The Medial Prefrontal Cortex and the Emergence of Self-Conscious Emotion in Adolescence. Psychological Science 24: 1554–1562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Blakemore S-J (2008): The social brain in adolescence. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 9: 267–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Gunther Moor B, Op de Macks ZA, Güroğlu B, Rombouts SARB, Van der Molen MW, Crone EA (2012): Neurodevelopmental changes of reading the mind in the eyes. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci 7: 44–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Overgaauw S, van Duijvenvoorde ACK, Gunther Moor B, Crone EA (2015): A longitudinal analysis of neural regions involved in reading the mind in the eyes. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci 10: 619–627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Roisman GI, Masten AS, Coatsworth JD, Tellegen A (2004): Salient and emerging developmental tasks in the transition to adulthood. Child Dev 75: 123–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Schwartz OS, Simmons JG, Whittle S, Byrne ML, Yap MBH, Sheeber LB, Allen NB (2017): Affective Parenting Behaviors, Adolescent Depression, and Brain Development: A Review of Findings From the Orygen Adolescent Development Study. Child Development Perspectives 11: 90–96. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Sheeber L, Hops H, Alpert A, Davis B, Andrews J (1997): Family Support and Conflict: Prospective Relations to Adolescent Depression. J Abnorm Child Psychol 25: 333–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.van Harmelen A-L, Gibson JL, St Clair MC, Owens M, Brodbeck J, Dunn V, et al. (2016): Friendships and Family Support Reduce Subsequent Depressive Symptoms in At-Risk Adolescents. PLoS One 11. 10.1371/journal.pone.0153715 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.McDougall P, Vaillancourt T (2015): Long-term adult outcomes of peer victimization in childhood and adolescence: Pathways to adjustment and maladjustment. American Psychologist 70: 300–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kendrick K, Jutengren G, Stattin H (2012): The protective role of supportive friends against bullying perpetration and victimization. Journal of Adolescence 35: 1069–1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Copeland WE, Wolke D, Angold A, Costello EJ (2013): Adult psychiatric outcomes of bullying and being bullied by peers in childhood and adolescence. JAMA Psychiatry 70: 419–426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Platt B, Kadosh KC, Lau JYF (2013): The Role of Peer Rejection in Adolescent Depression. Depression and Anxiety 30: 809–821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Nock MK, Prinstein MJ, Sterba SK (2009): Revealing the form and function of self-injurious thoughts and behaviors: A real-time ecological assessment study among adolescents and young adults. Journal of Abnormal Psychology 118: 816–827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Whitlock J (2006): Self-injurious Behaviors in a College Population. PEDIATRICS 117: 1939–1948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Wang J, Iannotti RJ, Nansel TR (2009): School Bullying Among Adolescents in the United States: Physical, Verbal, Relational, and Cyber. Journal of Adolescent Health 45: 368–375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Beeri A, Lev□Wiesel R (2012): Social rejection by peers: a risk factor for psychological distress. Child and Adolescent Mental Health 17: 216–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Narr RK, Allen JP, Tan JS, Loeb EL (2019): Close Friendship Strength and Broader Peer Group Desirability as Differential Predictors of Adult Mental Health. Child Dev 90: 298–313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Havewala M, Felton JW, Lejuez CW (2019): Friendship Quality Moderates the Relation between Maternal Anxiety and Trajectories of Adolescent Internalizing Symptoms. J Psychopathol Behav Assess 41: 495–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Allen JP, Uchino BN, Hafen CA (2015): Running With the Pack: Teen Peer-Relationship Qualities as Predictors of Adult Physical Health. Psychol Sci 26: 1574–1583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Prinstein MJ, Boergers J, Vernberg EM (2001): Overt and Relational Aggression in Adolescents: Social-Psychological Adjustment of Aggressors and Victims. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology 30: 479–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Marion D, Laursen B, Zettergren P, Bergman LR (2013): Predicting life satisfaction during middle adulthood from peer relationships during mid-adolescence. J Youth Adolesc 42: 1299–1307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Rueger SY, Malecki CK, Pyun Y, Aycock C, Coyle S (2016): A meta-analytic review of the association between perceived social support and depression in childhood and adolescence. Psychological Bulletin 142: 1017–1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Heath NL, Ross S, Toste JR, Charlebois A, Nedecheva T (2009): Retrospective analysis of social factors and nonsuicidal self-injury among young adults. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science / Revue canadienne des sciences du comportement 41: 180–186. [Google Scholar]

- 102.Schwartz-Mette RA, Smith RL (2018): When Does Co-Rumination Facilitate Depression Contagion in Adolescent Friendships? Investigating Intrapersonal and Interpersonal Factors. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology 47: 912–924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Bastin M, Vanhalst J, Raes F, Bijttebier P (2018): Co-Brooding and Co-Reflection as Differential Predictors of Depressive Symptoms and Friendship Quality in Adolescents: Investigating the Moderating Role of Gender. J Youth Adolescence 47: 1037–1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Rose AJ, Carlson W, Waller EM (2007): Prospective associations of co-rumination with friendship and emotional adjustment: Considering the socioemotional trade-offs of co-rumination. Developmental Psychology 43: 1019–1031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.McNelles LR, Connolly JA (1999): Intimacy between adolescent friends: Age and gender differences in intimate affect and intimate behaviors. Journal of Research on Adolescence 9: 143–159. [Google Scholar]

- 106.Stone LB, Hankin BL, Gibb BE, Abela JRZ (2011): Co-rumination predicts the onset of depressive disorders during adolescence. J Abnorm Psychol 120: 752–757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Collins WA, Welsh DP, Furman W (2009): Adolescent Romantic Relationships. Annual Review of Psychology 60: 631–652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Suleiman AB, Harden KP (2016): The importance of sexual and romantic development in understanding the developmental neuroscience of adolescence. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience 17: 145–147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Davila J (2008): Depressive Symptoms and Adolescent Romance: Theory, Research, and Implications. Child Development Perspectives 2: 26–31. [Google Scholar]

- 110.Connolly JA, McIsaac C (2009): Romantic relationships in adolescence. Handbook of Adolescent Psychology: Contextual Influences on Adolescent Development, Vol. 2, 3rd Ed. Hoboken, NJ, US: John Wiley & Sons Inc, pp 104–151. [Google Scholar]

- 111.Davila J, Capaldi DM, Greca AML (2016): Adolescent/Young Adult Romantic Relationships and Psychopathology. Developmental Psychopathology. American Cancer Society, pp 1–34.

- 112.Hughes M, Morrison K, Asada KJK (2005): What’s love got to do with it? Exploring the impact of maintenance rules, love attitudes, and network support on friends with benefits relationships. Western Journal of Communication 69: 49–66. [Google Scholar]

- 113.Mirsu-Paun A, Oliver JA (2017): How Much Does Love Really Hurt? A Meta-Analysis of the Association Between Romantic Relationship Quality, Breakups and Mental Health Outcomes in Adolescents and Young Adults. Journal of Relationships Research 8. 10.1017/jrr.2017.6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Joyner K, Udry JR (2000): You don’t bring me anything but down: adolescent romance and depression. J Health Soc Behav 41: 369–391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Asarnow JR, Baraff LJ, Berk M, Grob C, Devich-Navarro M, Suddath R, et al. (2008): Pediatric emergency department suicidal patients: two-site evaluation of suicide ideators, single attempters, and repeat attempters. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 47: 958–966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Bagge CL, Glenn CR, Lee H-J (2013): Quantifying the impact of recent negative life events on suicide attempts. J Abnorm Psychol 122: 359–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Price M, Hides L, Cockshaw W, Staneva AA, Stoyanov SR (2016): Young Love: Romantic Concerns and Associated Mental Health Issues among Adolescent Help-Seekers. Behavioral Sciences 6: 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Cheng TW, Vijayakumar N, Flournoy JC, Op de Macks Z, Peake SJ, Flannery JE, et al. (2020): Feeling left out or just surprised? Neural correlates of social exclusion and overinclusion in adolescence. Cogn Affect Behav Neurosci. 10.3758/s13415-020-00772-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 119.Masten CL, Eisenberger NI, Borofsky LA, Pfeifer JH, McNealy K, Mazziotta JC, Dapretto M (2009): Neural correlates of social exclusion during adolescence: understanding the distress of peer rejection. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci 4: 143–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Masten CL, Eisenberger NI, Borofsky LA, McNealy K, Pfeifer JH, Dapretto M (2011): Subgenual anterior cingulate responses to peer rejection: A marker of adolescents’ risk for depression. Development and Psychopathology 23: 283–292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Masten CL, Eisenberger NI, Pfeifer JH, Dapretto M (2013): Neural responses to witnessing peer rejection after being socially excluded: fMRI as a window into adolescents’ emotional processing. Developmental Science 16: 743–759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Guyer AE, Jarcho JM (2018): Neuroscience and Peer Relations. Handbook of Peer Interactions, Relationships, and Groups, In Bukowski WM, Laursen B, Rubin KH (Eds.),. The Guilford Press, p 23. [Google Scholar]

- 123.Silk JS, Siegle GJ, Lee KH, Nelson EE, Stroud LR, Dahl RE (2014): Increased neural response to peer rejection associated with adolescent depression and pubertal development. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci 9: 1798–1807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Vijayakumar N, Cheng TW, Pfeifer JH (2017): Neural correlates of social exclusion across ages: A coordinate-based meta-analysis of functional MRI studies. NeuroImage 153: 359–368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Nelson EE, Guyer AE (2011): The development of the ventral prefrontal cortex and social flexibility. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience 1: 233–245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Jankowski KF, Batres J, Scott H, Smyda G, Pfeifer JH, Quevedo K (2018): Feeling left out: depressed adolescents may atypically recruit emotional salience and regulation networks during social exclusion. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci 13: 863–876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Oppenheimer CW, Silk JS, Lee KH, Dahl RE, Forbes E, Ryan N, Ladouceur CD (2019): Suicidal Ideation Among Anxious Youth: A Preliminary Investigation of the Role of Neural Processing of Social Rejection in Interaction with Real World Negative Social Experiences. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 10.1007/s10578-019-00920-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 128.Brown RC, Plener PL, Groen G, Neff D, Bonenberger M, Abler B (2017): Differential Neural Processing of Social Exclusion and Inclusion in Adolescents with Non-Suicidal Self-Injury and Young Adults with Borderline Personality Disorder. Front Psychiatry 8. 10.3389/fpsyt.2017.00267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Groschwitz RC, Plener PL, Groen G, Bonenberger M, Abler B (2016): Differential neural processing of social exclusion in adolescents with non-suicidal self-injury: An fMRI study. Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging 255: 43–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Fritz J, Stretton J, Askelund AD, Schweizer S, Walsh ND, Elzinga BM, et al. (2019): Mood and neural responses to social rejection do not seem to be altered in resilient adolescents with a history of adversity. Development and Psychopathology 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Vijayakumar N, Flournoy J, Mills K, Cheng TW, Mobasser A, Flannery J, et al. (2019): Getting to know me better: An fMRI study of intimate and superficial self-disclosure to friends during adolescence. 10.31234/osf.io/h8gkc [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Fortenberry JD (2013): Puberty and adolescent sexuality. Hormones and Behavior 64: 280–287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Carlson W, Rose AJ (2007): The Role of Reciprocity in Romantic Relationships in Middle Childhood and Early Adolescence. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly 53: 262–290. [Google Scholar]

- 134.Finkelstein JW, Susman EJ, Chinchilli VM, D’Arcangelo MR, Kunselman SJ, Schwab J, et al. (1998): Effects of estrogen or testosterone on self-reported sexual responses and behaviors in hypogonadal adolescents. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism 83: 2281–2285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Buss D (2019): Evolutionary Psychology: The New Science of the Mind, 6 edition. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- 136.Sontag LM, Graber JA, Brooks-Gunn J, Warren MP (2008): Coping with Social Stress: Implications for Psychopathology in Young Adolescent Girls. J Abnorm Child Psychol 36: 1159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Sontag LM, Graber JA, Clemans KH (2011): The Role of Peer Stress and Pubertal Timing on Symptoms of Psychopathology During Early Adolescence. J Youth Adolescence 40: 1371–1382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Ge X, Natsuaki MN (2009): In Search of Explanations for Early Pubertal Timing Effects on Developmental Psychopathology: Current Directions in Psychological Science. Retrieved April 17, 2020, from 10.1111/j.1467-8721.2009.01661.x [DOI]

- 139.Hamlat EJ, Shapero BG, Hamilton JL, Stange JP, Abramson LY, Alloy LB (2015): Pubertal Timing, Peer Victimization, and Body Esteem Differentially Predict Depressive Symptoms in African American and Caucasian Girls. The Journal of Early Adolescence 35: 378–402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Pfeifer JH, Allen NB (2016): The audacity of specificity: Moving adolescent developmental neuroscience towards more powerful scientific paradigms and translatable models. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience 17: 131–137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Odgers CL, Jensen MR (2020): Annual Research Review: Adolescent mental health in the digital age: facts, fears, and future directions. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 61: 336–348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Somerville LH (2016): Searching for signatures of brain maturity: What are we searching for? Neuron 92: 1164–1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Barendse MEA, Vijayakumar N, Byrne ML, Flannery JE, Cheng TW, Flournoy JC, et al. (2020): Study Protocol: Transitions in Adolescent Girls (TAG). Frontiers in Psychiatry 10. 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.01018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Barch DM, Albaugh MD, Avenevoli S, Chang L, Clark DB, Glantz MD, et al. (2018): Demographic, physical and mental health assessments in the adolescent brain and cognitive development study: Rationale and description. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience 32: 55–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Uban KA, Horton MK, Jacobus J, Heyser C, Thompson WK, Tapert SF, et al. (2018): Biospecimens and the ABCD study: Rationale, methods of collection, measurement and early data. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience 32: 97–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Mendle J, Ferrero J (2012): Detrimental psychological outcomes associated with pubertal timing in adolescent boys. Developmental Review 32: 49–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Negriff S, Susman EJ (2011): Pubertal Timing, Depression, and Externalizing Problems: A Framework, Review, and Examination of Gender Differences. Journal of Research on Adolescence (Wiley-Blackwell) 21: 717–746. [Google Scholar]

- 148.Shirtcliff EA, Dahl RE, Pollak SD (2009): Pubertal Development: Correspondence Between Hormonal and Physical Development. Child Development 80: 327–337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.