Abstract

Objectives. To assess the quality of population-level US mortality data in the US Census Bureau Numerical Identification file (Numident) and describe the details of the mortality information as well as the novel person-level linkages available when using the Census Numident.

Methods. We compared all-cause mortality in the Census Numident to published vital statistics from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. We provide detailed information on the linkage of the Census Numident to other Census Bureau survey, administrative, and economic data.

Results. Death counts in the Census Numident are similar to those from published mortality vital statistics. Yearly comparisons show that the Census Numident captures more deaths since 1997, and coverage is slightly lower going back in time. Weekly estimates show similar trends from both data sets.

Conclusions. The Census Numident is a high-quality and timely source of data to study all-cause mortality. The Census Bureau makes available a vast and rich set of restricted-use, individual-level data linked to the Census Numident for researchers to use.

Public Health Implications. The Census Numident linked to data available from the Census Bureau provides infrastructure for doing evidence-based public health policy research on mortality.

Mortality is a critical outcome in public health surveillance. The COVID-19 pandemic has demonstrated the importance of placing individual death events within their social, economic, and geographic contexts. For example, to identify if Black and Hispanic individuals are overrepresented in COVID-19 mortality rates, high-quality race and ethnicity data linked to mortality records are necessary. To identify why Black and Hispanic individuals are overrepresented, we may need a much richer set of data, potentially going back in time. To study how frontline health workers are impacted by COVID-19 mortality, death records must be linked with occupation or employer data. These kinds of person-level data linkages are often made by public health researchers in smaller settings, but doing so at the population level and in a timely way during a public health emergency is unprecedented.

The Census Bureau’s Data Linkage Infrastructure is an ecosystem of survey and administrative records that are linked at the person, address, and business levels. The files are de-identified and made available anonymously to researchers in a restricted-access setting. This infrastructure is an excellent environment to study mortality because it holds full-population death data from the Social Security Administration’s Numerical Identification file (SSA Numident). While the SSA Numident has historically suffered from underreporting of deaths and incorrect death dates, the Social Security Administration’s (SSA’s) efforts to improve death monitoring have greatly enhanced the mortality information in the SSA Numident file. 1–3 Moreover, the Census Bureau has actively analyzed, curated, and documented the death information in the file, working with SSA to disseminate high-quality and complete death data through the Census Bureau’s Numerical Identification file (Census Numident).

The linkage of Census Bureau surveys, administrative data, business data, and death data allows for rich analyses of the relationships between all-cause mortality and demographic characteristics, socioeconomic factors, educational attainment, family structure, residential location, migration, program participation, and early life conditions. While research use of SSA death data is not new, 4 the research possibilities for measuring relationships between social and economic determinants of all-cause mortality with the data available through the Census Bureau are vast and generally underutilized. 5 , 6 These data are currently accessible to researchers working on approved projects within the Federal Statistical Research Data Center (FSRDC) network.

In this article, we introduce the mortality data in the Census Numident and explain the origin and creation of the data file. To assess the quality of the data, we compared mortality estimates from the Census Numident with the primary population-level published statistics for the United States collected from states by the National Center for Health Statistics and published by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The availability and linkage of these mortality data to other data held at the Census Bureau for research is also described, as well as how researchers can access these data. We show that the Census Numident is an excellent source to study all-cause mortality, especially for analyzing social determinants, understanding neighborhood context, making evidence-based decisions, and even studying pandemics.

SOCIAL SECURITY ADMINISTRATION AND CENSUS NUMIDENT FILES

SSA uses the SSA Numident to maintain records of Social Security Number (SSN) holders. Although SSNs were created and issued starting in 1936, electronic tracking of SSN information in the Numident began in 1972. The Numident contains all interactions individuals have with SSA related to SSNs, including information on SSN applications, claim records, death information, and requested changes to SSN information. There are now more than 1 billion transactions within the SSA Numident for approximately 518 million living and deceased SSN holders in the SSA Numident.

The Census Bureau obtains SSA Numident data from SSA to improve Census Bureau survey and decennial census data, perform record linkage, and conduct research and statistical projects. To facilitate the use of the SSA Numident data, the Census Bureau processes quarterly updates from SSA transaction records to create a person-level research file that includes the history of individual-level interactions with the SSA Numident. The Census Bureau calls this processed file the Census Numident. Like the SSA Numident, the Census Numident is a cumulative file. The most recent vintage of the Census Numident is the largest and most up-to-date version, and researchers should use the newest vintage for mortality research.

The Census Bureau assigns a unique, anonymous identifier, called a Protected Identification Key (PIK) to all individuals in the Numident based solely on the SSN. All names and SSNs are removed from the Census Numident file, and the resulting data file, with the PIK added, is then made available to Census Bureau staff and external researchers for approved Census Bureau production and research projects. PIKs are used to link records at the person level over time and across survey and administrative records.

The scope of information in an individual’s Census Numident record varies based on when the individual received an SSN, and if the individual has interacted with SSA, such as for a name change. In general, most records include date of birth, place of birth, sex, race/ethnicity, date of SSN application, dates and types of SSA interactions, and the reported date of death (month, day, and year) if deceased. (The variables are listed in Table A, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org.)

DEATH INFORMATION IN THE NUMIDENT

SSA administers the US Old-Age, Survivors, and Disability Insurance program, often referred to as “Social Security.” The death information included in the SSA Numident is collected by SSA for the purposes of administering the Old-Age, Survivors, and Disability Insurance program, and the way this information is collected and managed has changed over time. Death information is obtained through several sources including first-party reports of death from family members and representatives and verified third-party reports from friends, state government offices, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, the Department of Veterans Affairs, and the Internal Revenue Service.

SSA began maintaining death information using electronic methods in 1962 7 and integrated those records into the Numident when it was created. 8 Information on deaths before 1962 is often incomplete or missing. 8 Previous research has shown that because SSA was primarily focused on deaths of claimants, the Numident had greater death coverage for deaths occurring at older ages than deaths occurring at younger ages. 9 However, since 2005, SSA has improved its methods for monitoring deaths by using a new system for electronically registering deaths, the Death Information Processing System. In 2019, SSA undertook the Death Data Improvement Initiative following a report from the Government Accountably Office in 2013 about errors in the death data 1 and 2 reports from the Office of the Inspector General about missing and incorrect deaths in the Numident. 2 , 3 This resulted in more records with death information and updates to death information for deaths going back to 1960. The SSA Numident is now SSA’s single system of record for death information. 10

The data included in the SSA Numident and, thus, the Census Numident are limited to SSN holders, and their deaths can occur anywhere, including outside of the United States. The SSA Numident also contains much more complete death records than the oft-used public Death Master File, 11–14 which has always been a subset of the SSA Numident death records. (See “Death Data Related to the Census Numident” available in the supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org for more information.) The Death Master File has deteriorated in coverage since a reinterpretation of privacy statutes in 2011, which limited the inclusion of state records. 15–17 While SSA death reports are considered to be measured with some error, 18 they have been used for research on all-cause mortality even before these recent data quality improvements. 19–22

METHODS

We measured all-cause mortality using the Census Numident by simply counting the deaths based on the recorded year of death. For the primary analyses, we used the Census Numident date of death, which is the most recent death information for a person from the SSA Numident. We benchmarked all-cause mortality estimates using vital statistics mortality estimates from the CDC, the primary source of mortality data for the United States. The CDC data are compiled from death certificates from state vital statistics offices that have been provided to the National Center for Health Statistics. We use the Compressed Mortality Files from CDC WONDER for the years 1980 to 2016. For 2017 to 2018, we used the CDC WONDER public data tool, and for 2019 to 2020, we used counts from the provisional tables. 23 We also compared the Census Numident death counts before 1980 to published mortality estimated from the CDC Compressed Mortality data and the National Vital Statistics System historical tables. 24 The CDC data, including the restricted-use National Death Index, provide date of death, age, sex, race, cause of death, and place of death.

The CDC data have a different universe than the Census Numident, but they provide a useful comparison to assess the coverage of the Numident file for measuring mortality. The CDC-published estimates only include deaths occurring in US states and are not limited to SSN holders, whereas the Census Numident includes deaths of SSN holders dying abroad and in US territories but does not include deaths occurring in the United States for those without an SSN. Thus, almost all the deaths in the United States will appear in each of the files. The difference in counts between the files depends on both error in the data-generating process and the difference between the number of deaths occurring to SSN holders outside of US states and the number of deaths occurring to individuals within the United States without an SSN.

We further benchmarked the Census Numident to the CDC data by performing comparisons of weekly death estimates, age of death, and place of death. Although the Numident does not contain place of death, we were able to proxy for location of death by identifying almost all individuals’ most recent residential locations from the Census Bureau’s Master Address File - Auxiliary Reference File (MAF-ARF), which is a data file created using information from population-level censuses and administrative records, including annual Medicare enrollment and individual tax filings. Thus, we can approximate death counts by state using records that were assigned a location in the MAF-ARF. Additional analyses of the death counts by race and sex are shown in Tables D and E (available as supplements to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org). By comparing the Census Numident to the CDC data in more detail, we can assess data quality and identify any shortcomings of mortality records in the Census Numident.

RESULTS

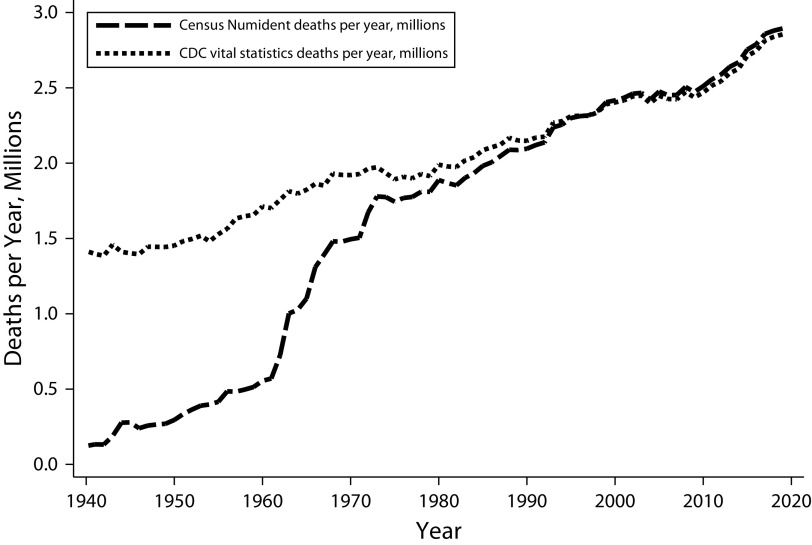

Figure 1 shows yearly mortality estimates from the Census Numident and the CDC from 1940 to the present (the underlying estimates can be found in Table B, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org). The yearly comparison shows that the Census Numident has more deaths than the CDC estimates in each year from 1997 forward. Going back in time, the Census Numident coverage declines slightly each year until 1985, when the Census Numident contains 95% of the death counts from the CDC and remains around there until 1980. Before 1980, the Census Numident death counts drop steadily until 1967, when they are 75% of the CDC counts. The coverage then drops precipitously, reaching down to 32% of the CDC count in 1960 and continues to decline steadily to under 10% in 1940. This large decrease in deaths captured by the Census Numident occurs directly before the creation of the electronic system for capturing deaths.

FIGURE 1.

Coverage of Deaths per Year in the Census Numident vs Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Vital Statistics: United States, 1940–2019

Source. Census Numident calculations from vintage 2020Q4. All Census Numident results were approved for release by the US Census Bureau, authorization number CBDRB-FY21-ERD002-009. CDC counts were obtained from the CDC WONDER database.

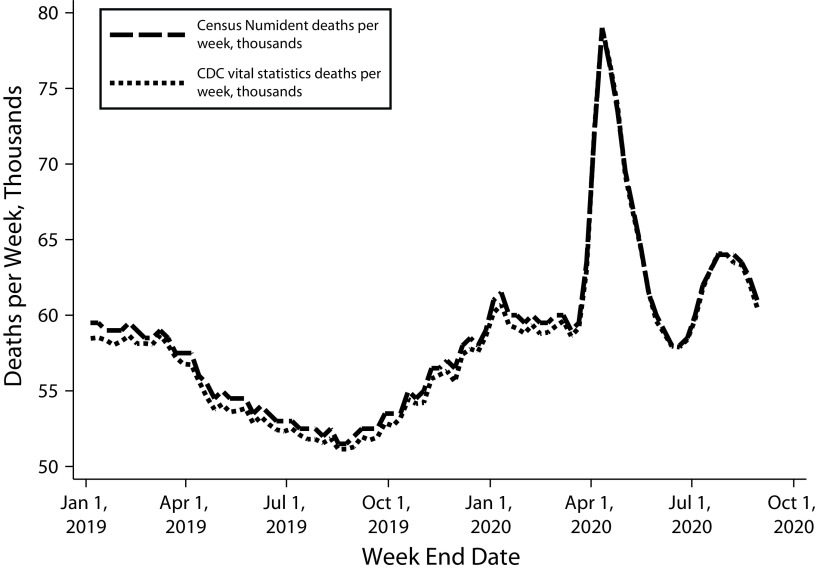

The yearly mortality counts suggest that the Census Numident is similar to the vital statistics from CDC on average. Likewise, the weekly mortality estimates from the Census Numident and CDC from 2019 and 2020 are nearly identical. Figure 2 shows the weekly death counts from the Census Numident and the CDC from January 2019 through August 2020. The weekly estimates are nearly the same over the period, both showing the large spike from the COVID-19 pandemic. The weekly coverage of the Census Numident, when compared with the CDC data, ranges from 97% in the final week to 102% in the first week of 2019. These results show that the death data in the Census Numident are accurate and timely. Further analyses show that, in 2019, most deaths appear in the Census Numident within 7 days after the death occurs. This has improved since 2000, when more than half of the deaths were added to the SSA Numident 13 or more days following the death. (Detailed statistics about reporting delay can be found in Table F, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org.)

FIGURE 2.

Coverage of Deaths per Week in the Census Numident vs Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Vital Statistics, January 2019‒September 2020

Source. Census Numident calculations from the vintage 2020Q4. All Census Numident results were approved for release by the US Census Bureau, authorization number CBDRB-FY21-ERD002-009. CDC counts were obtained from the CDC WONDER database.

Table 1 shows death counts that occurred between 2000 and 2018 by age at the time of death from both the Census Numident and the CDC. Columns 2 and 3 show the percentage of the total deaths occurring for individuals at those ages within each of the files and column 4 shows the ratio of Numident to CDC deaths. The Census Numident has a larger share of deaths for people of unknown ages (death records missing birth dates or exact date of death) and fewer deaths for individuals aged younger than 1 year than the CDC data. The infant deaths captured by CDC and not the Census Numident are likely from live births that do not result in SSN issuance because of deaths occurring shortly after births. 25 The share of deaths in each of the age categories is remarkably similar across the files in the other age categories. For ages older than 75 years, the Census Numident has a slightly larger share of total deaths falling between ages 75 and 84 years and age 85 years and older.

TABLE 1.

Mortality Counts by Age at Death: United States, 2000–2018

| Age | Census Numident (% of Total) | CDC Vital Statistics (% of Total) | Numident/CDC |

| < 1 y | 231 000 (0.47) | 489 447 (1.02) | 0.47 |

| 1–4 y | 82 000 (0.17) | 84 362 (0.18) | 0.97 |

| 5–14 y | 114 000 (0.23) | 114 051 (0.24) | 1.00 |

| 15–24 y | 583 000 (1.20) | 600 236 (1.25) | 0.97 |

| 25–34 y | 842 000 (1.73) | 869 313 (1.80) | 0.97 |

| 35–44 y | 1 483 000 (3.04) | 1 506 617 (3.13) | 0.98 |

| 45–54 y | 3 358 000 (6.88) | 3 365 173 (6.99) | 1.00 |

| 55–64 y | 5 899 000 (12.09) | 5 830 574 (12.10) | 1.01 |

| 65–74 y | 8 586 000 (17.59) | 8 351 622 (17.34) | 1.03 |

| 75–84 y | 12 830 000 (26.29) | 12 514 521 (25.98) | 1.03 |

| ≥ 85 y | 14 730 000 (30.18) | 14 446 308 (29.99) | 1.02 |

| Missing | 65 000 (0.13) | 4 151 (0.01) | 15.66 |

| Total | 48 803 000 | 48 176 375 | 1.01 |

Note. CDC = Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Missing age indicates that age on date of death could not be calculated because the observation was missing the day of the month the death occurred. The Census Numident counts are rounded per Census Bureau Disclosure Review Board guidelines.

Source. Census Numident calculations from vintage 2020Q4. All Census Numident results were approved for release by the US Census Bureau, authorization numbers CBDRB-FY21-ERD002-004 and CBDRB-FY21-ERD002-009. The CDC vital statistics counts were obtained from the CDC WONDER database.

We were able to use the MAF-ARF to obtain the deceased’s state of residence during the year of death (or location during most recent year in the MAF-ARF before death) for 92% of the total deaths in the Census Numident from 2010 to 2018. While some of the individuals not linked to the MAF-ARF were because they lived abroad, most were likely not linked because of incompleteness in the MAF-ARF (though we cannot distinguish between these 2 groups). The state-level comparison of the Census Numident to the CDC estimates presented in Table 2 support this as the Census Numident death counts are more than 90% of the CDC counts in most states, but there are 11 states with coverage between 85% and 90%, and Hawaii has the lowest coverage rate at 72% of the CDC count. These states in particular suggest that this undercount is not comprised fully of deaths from residents without SSNs, and while it is possible to estimate location of death, these data are incomplete for studying state-level deaths.

TABLE 2.

State-Level Mortality Counts: United States, 2010–2018

| States | Census Numident, No. | CDC Vital Statistics, No. | Numident/ CDC |

| Hawaii | 69 000 | 95 857 | 0.720 |

| Montana | 73 500 | 85 849 | 0.856 |

| West Virginia | 173 000 | 201 324 | 0.859 |

| Vermont | 44 500 | 51 428 | 0.865 |

| New Mexico | 137 000 | 157 207 | 0.871 |

| Mississippi | 243 000 | 277 152 | 0.877 |

| Kentucky | 363 000 | 408 180 | 0.889 |

| Louisiana | 348 000 | 390 890 | 0.890 |

| Arkansas | 248 000 | 277 887 | 0.892 |

| Arizona | 424 000 | 474 748 | 0.893 |

| Idaho | 103 000 | 115 165 | 0.894 |

| Oregon | 278 000 | 309 821 | 0.897 |

| Oklahoma | 312 000 | 347 505 | 0.898 |

| North Dakota | 50 000 | 55 689 | 0.898 |

| North Carolina | 699 000 | 775 916 | 0.901 |

| South Carolina | 372 000 | 412 329 | 0.902 |

| Utah | 136 000 | 150 439 | 0.904 |

| Maine | 112 000 | 123 730 | 0.905 |

| Alabama | 415 000 | 458 389 | 0.905 |

| Texas | 1 512 000 | 1 654 386 | 0.914 |

| Washington | 434 000 | 474 541 | 0.915 |

| Georgia | 639 000 | 697 003 | 0.917 |

| Missouri | 486 000 | 527 724 | 0.921 |

| New York | 1 258 000 | 1 365 987 | 0.921 |

| Tennessee | 540 000 | 585 743 | 0.922 |

| Nevada | 185 000 | 200 165 | 0.924 |

| Alaska | 34 500 | 37 288 | 0.925 |

| Ohio | 970 000 | 1 046 075 | 0.927 |

| Massachusetts | 466 000 | 501 959 | 0.928 |

| Indiana | 514 000 | 553 409 | 0.929 |

| Kansas | 217 000 | 233 479 | 0.929 |

| Virginia | 537 000 | 577 702 | 0.930 |

| Rhode Island | 82 000 | 88 214 | 0.930 |

| Colorado | 295 000 | 316 578 | 0.932 |

| California | 2 115 000 | 2 269 249 | 0.932 |

| Nebraska | 135 000 | 144 777 | 0.932 |

| Pennsylvania | 1 096 000 | 1 173 367 | 0.934 |

| Illinois | 885 000 | 946 599 | 0.935 |

| New Hampshire | 97 000 | 103 632 | 0.936 |

| Iowa | 246 000 | 262 491 | 0.937 |

| Wisconsin | 427 000 | 453 863 | 0.941 |

| New Jersey | 611 000 | 649 343 | 0.941 |

| South Dakota | 64 000 | 67 896 | 0.943 |

| Wyoming | 39 500 | 41 826 | 0.944 |

| Minnesota | 356 000 | 376 234 | 0.946 |

| Michigan | 797 000 | 841 628 | 0.947 |

| District of Columbia | 41 000 | 43 234 | 0.948 |

| Delaware | 72 000 | 75 720 | 0.951 |

| Maryland | 400 000 | 419 668 | 0.953 |

| Connecticut | 259 000 | 270 646 | 0.957 |

| Florida | 1 621 000 | 1 690 238 | 0.959 |

| Total | 22 031 000 | 23 860 169 | 0.923 |

Note. CDC = Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The Census Numident counts are rounded per Census Bureau Disclosure Review Board guidelines.

Source. Census Numident calculations from vintage 2020Q4. All Census Numident results were approved for release by the US Census Bureau, authorization numbers CBDRB-FY21-ERD002-004 and CBDRB-FY21-ERD002-009. The CDC counts were obtained from the CDC WONDER database.

The results from benchmarking the Census Numident to the CDC vital statistics show that the population-level death counts are similar across the data sources, even though each has a slightly different universe. The timing and quality of the Census Numident data have improved over time, and the death data in the Census Numident are a high-quality source for measuring all-cause mortality.

DISCUSSION

The results show that the Census Numident accurately estimates all-cause mortality for the United States. While these data do not include cause of death, they become valuable research tools when linked at the person level to other data held at the Census Bureau. Moreover, these data are available to researchers working on approved projects through the FSRDC network.

Linking Census Bureau Data to the Census Numident

Data sets available within the Census Bureau’s Data Linkage Infrastructure are linkable to the Census Numident and allow researchers to measure the relationship between mortality and demographic characteristics, educational attainment, economic well-being, neighborhoods, migration, public policy, program participation, disability, general health, and many other potential social determinants of mortality. Researchers are already using 2000 and 2010 decennial census data and American Community Survey (ACS) data linked to Census Numident birthplace information to proxy for early life location and exposure. 26 Moreover, researchers can link individuals to the 1940 Decennial Census, 27 and soon to all decennial censuses from 1940 to 2020, to understand the impacts of early life conditions and place-based exposure on mortality. 28

As described previously, individual records in the Census Numident are assigned PIKs based solely on SSN. Data from the Census Numident are then included in the Census Bureau’s Reference Files, which are used within the Census Bureau’s Person Identification Validation System to assign PIKs probabilistically to other Census Bureau data using information such as SSN, name, address, birthdate, and sex. 29 All names and SSNs are removed after PIK application so that data access by researchers remains confidential. Any data file that has been assigned PIKs can be linked at the individual level to the Census Numident. While the assignment of PIKs to data sets is probabilistic, reviews of the Person Identification Validation System show that PIK assignment has resulted in high-quality linkages with minimal error. 30 , 31 Because the Census Numident is restricted to SSN holders, linkages to the other data sets are also limited to SSN holders. The data files are restricted-use and available to researchers upon approval for specified projects.

The Census Bureau surveys that can be linked anonymously at the person level to the Census Numident vary in the type of data and population coverage. The 2000 and 2010 Decennial Censuses capture precise location, household structure, and basic demographic information for all residents in the United States, and roughly 90% of the person records in these files have been assigned a PIK. Additional detailed information on educational attainment, federal program participation, migration, employment, income, disability, fertility, veteran status, and dwelling characteristics are available for nearly 20% of Census 2000 (known as the long-form sample). Since 2000, the ACS has been fielded to nearly 3% of the population yearly, and it includes questions similar to the Census 2000 long form. Various Census Bureau surveys also have PIKs assigned to them, and they include more detailed questions on health, well-being, and life experiences for smaller samples. These data files include the Current Population Survey Annual Social and Economic Supplement, the Survey of Income and Program Participation, the National Crime Victimization Survey, and the National Survey of College Graduates.

In addition to survey data, the Census Bureau Data Linkage Infrastructure holds administrative data from federal agencies, state and local governments, and third parties that have had PIKs assigned at the person level. These data include Medicare and Medicaid enrollment data, the Criminal Justice Administrative Records System, program data from the Department of Housing and Urban Development, and state-level administrative records from the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program and Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children. Researchers can also access the MAF-ARF, which links individuals with PIKs to address-level residential locations from 2000 to the present using comingled survey and administrative data, and the Census Household Composition Key, which links PIKs of parents to PIKs of children born from 1997 to the present.

Finally, the Census Bureau’s Longitudinal Employer-Household Dynamics program integrates employer and employee data from state unemployment insurance records with other business and demographic data. Employees in the Longitudinal Employer-Household Dynamics data can be linked by PIK to the Census Numident. And the businesses in the Longitudinal Employer-Household Dynamics data can be linked to the many economic microdata files created by the Census Bureau for research including the Business Register, the Economic Census, and other establishment surveys.

Access and Use of the Census Numident File

The Census Numident file is available to researchers through the FSRDCs, along with all the other data described previously, for use on approved projects. The FSRDC network currently includes 32 physical research centers at universities and research institutions, and many projects are currently approved for virtual access. 32 Researchers can apply to use the Census Numident data through the standard Census Bureau FSRDC application process, which starts by contacting the closest FSRDC. 33

The Census Numident is updated quarterly with new SSA transactions in March, June, September, and December. As discussed, there are slight delays in death reporting to SSA and inclusion in the Numident updates. At the median, dates of death now appear in the Census Numident a week after death events. About 25% of deaths take at least 2 weeks to appear, and the slowest 5% take 6 weeks to appear.

Public Health Implications

Complete, high-quality mortality data are essential for public health monitoring. Linking mortality data to survey and administrative data allows public health researchers to understand the relationships between mortality and demographic characteristics, social factors, economics, and geographic settings. Large linked data are also essential to evaluate and create evidence-based public health policy. We have shown that the Census Numident is a high-quality, population-wide mortality data source and that the Census Bureau’s Data Linkage Infrastructure provides novel linkages to perform groundbreaking research on mortality. The use of these data to measure the relationships between social and economic determinants of all-cause mortality will improve our understanding of public health and health policy in the United States.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Results were approved for release by the Census Bureau’s Disclosure Review Board, authorization numbers CBDRB-FY21-ERD002-004 and CBDRB-FY21-ERD002-009.

We are grateful for feedback from Trent Alexander, Carla Medalia, Matthew Smeltz, and John Sullivan. We also appreciate helpful correspondence from many employees at the US Census Bureau and the Social Security Administration.

Note. Any views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the US Census Bureau.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

HUMAN PARTICIPANT PROTECTION

No human participants were used in this research, and this research was approved by the US Census Bureau.

References

- 1.Government Accountability Office. 2013. https://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-14-46

- 2.US Social Security Administration Office of the Inspector General. 2018. https://oig.ssa.gov/audits-and-investigations/audit-reports/A-09-17-50259

- 3.US Social Security Administration Office of the Inspector General. 2018. https://oig.ssa.gov/audits-and-investigations/audit-reports/A-06-17-50190

- 4.Kestenbaum B. Mortality by nativity. Demography. 1986;23(1):87–90. doi: 10.2307/2061410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rendall MS, Weden MM, Favreault MM, Waldron H. The protective effect of marriage for survival: a review and update. Demography. 2011;48(2):481–506. doi: 10.1007/s13524-011-0032-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miller S, Altekruse S, Johnson N, Wherry LR. 2019. https://www.nber.org/papers/w26081 [DOI]

- 7.The National Archives and Records Administration. 2018. https://aad.archives.gov/aad/content/aad_docs/rg047_num_faq_2018Dec.pdf

- 8.Puckett C. The story of the Social Security Number. Soc Secur Bull. 2009;69(2):55–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hill ME, Rosenwaike I. The Social Security Administration’s Death Master File: the completeness of death reporting at older ages. Soc Secur Bull. 2001;64(1):45–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.US Social Security Administration. 2017. https://secure.ssa.gov/apps10/poms.nsf/lnx/0202602050

- 11.Navar AM, Peterson ED, Steen DL, et al. Evaluation of mortality data from the Social Security Administration Death Master File for clinical research. JAMA Cardiol. 2019;4(4):375–379. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2019.0198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gavrilov LA, Gavrilova NS. Mortality measurement at advanced ages: a study of the Social Security Administration Death Master File. N Am Actuar J. 2011;15(3):432–447. doi: 10.1080/10920277.2011.10597629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huntington JT, Butterfield M, Fisher J, Torrent D, Bloomston M. The Social Security Death Index (SSDI) most accurately reflects true survival for older oncology patients. Am J Cancer Res. 2013;3(5):518–522. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hanna DB, Pfeiffer MR, Sackoff JE, Selik RM, Begier EM, Torian LV. Comparing the National Death Index and the Social Security Administration’s Death Master File to ascertain death in HIV surveillance. Public Health Rep. 2009;124(6):850–860. doi: 10.1177/003335490912400613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Technical Information Service. 2011. https://classic.ntis.gov/assets/pdf/import-change-dmf.pdf

- 16.Levin MA, Lin HM, Prabhakar G, McCormick PJ, Egorova NN. Alive or dead: validity of the Social Security Administration Death Master File after 2011. Health Serv Res. 2019;54(1):24–33. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.13069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.da Graca B, Filardo G, Nicewander D. Consequences for healthcare quality and research of the exclusion of records from the Death Master File. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2013;6(1):124–128. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.112.968826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cowper DC, Kubal JD, Maynard C, Hynes DM. A primer and comparative review of major US mortality databases. Ann Epidemiol. 2002;12(7):462–468. doi: 10.1016/S1047-2797(01)00285-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chetty R, Stepner M, Abraham S, et al. The association between income and life expectancy in the United States, 2001‒2014. JAMA. 2016;315(16):1750–1766. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.4226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dupre ME, Gu D, Vaupel JW. Survival differences among native-born and foreign-born older adults in the United States. PLoS One. 2012;7(5):e37177. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Turra CM, Elo IT. The impact of salmon bias on the Hispanic mortality advantage: new evidence from Social Security data. Popul Res Policy Rev. 2008;27(5):515–530. doi: 10.1007/s11113-008-9087-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Elo IT, Turra CM, Kestenbaum B. Mortality among elderly Hispanics in the United States: past evidence and new results. Demography. 2004;41(1):109–128. doi: 10.1353/dem.2004.0001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://wonder.cdc.gov

- 24.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/mortality/hist290a.htm

- 25.Social Security Programs Operations Manual System (POMS) 2015. https://secure.ssa.gov/apps10/poms.nsf/lnx/0110225080

- 26.Bailey MJ, Hoynes HW, Rossin-Slater M, Walker R. 2020. https://www.nber.org/papers/w26942

- 27.Massey CG, Genadek KR, Alexander JT, Gardner TK, O’Hara A. Linking the 1940 US Census with modern data. Hist Methods. 2018;51(4):246–257. doi: 10.1080/01615440.2018.1507772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Genadek KR, Alexander JT. 2019. https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/working-papers/2019/econ/dcdl-workingpaper.pdf

- 29.Wagner D, Lane M. 2014. https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/working-papers/2014/adrm/carra-wp-2014-01.pdf

- 30.Mulrow E, Mushtaq A, Pramanik S, Fontes A. 2011. https://www.norc.org/Research/Projects/Pages/census-personal-validation-system-assessment-pvs.aspx

- 31.Layne M, Wagner D, Rothhaas C. 2014. https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/working-papers/2014/adrm/carra-wp-2014-02.pdf

- 32.US Census Bureau. https://www.census.gov/content/census/en/about/adrm/fsrdc/locations.html

- 33.US Census Bureau. https://www.census.gov/about/adrm/fsrdc/apply-for-access.html