Abstract

Objective

To synthesise the available scientific evidence on the effects of combined exercise on glycaemic control, weight loss, insulin sensitivity, blood pressure and serum lipids among patients with type 2 diabetes (T2D) and concurrent overweight/obesity.

Design and sample

PubMed, EMBASE, Web of Science, the Cochrane library, WANFANG, CNKI, SinoMed, OpenGrey and ClinicalTrials.gov were searched from inception through April 2020 to identify randomised controlled trials (RCTs) that reported the effects of combined exercise in individuals with T2D and concurrent overweight/obesity.

Methods

Quality assessment was performed using the Cochrane Collaboration’s risk of bias tool. The mean difference (MD) with its corresponding 95% CI was used to estimate the effect size. Meta-analysis was performed using Review Manager V.5.3.

Results

A total of 10 RCTs with 978 participants were included in the meta-analysis. Pooled results demonstrated that combined exercise significantly reduced haemoglobin A1c (MD=−0.16%, 95% CI: −0.28 to −0.05, p=0.006); body mass index (MD=−0.98 kg/m2, 95% CI: −1.41 to −0.56, p<0.001); homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance (MD=−1.19, 95% CI: −1.93 to −0.46, p=0.001); serum insulin (MD=−2.18 μIU/mL, 95% CI: −2.99 to −1.37, p<0.001) and diastolic blood pressure (MD=−3.24 mm Hg, 95% CI: −5.32 to −1.16, p=0.002).

Conclusions

Combined exercise exerted significant effects in improving glycaemic control, influencing weight loss and enhancing insulin sensitivity among patients with T2D and concurrent overweight/obesity.

Keywords: general diabetes, medical education & training, public health

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study provided a comprehensive assessment of the effect of combined exercise in patients with type 2 diabetes and concurrent overweight/obesity.

Nine electronic databases were searched to provide a comprehensive range of studies.

Because of strict inclusion and exclusion criteria, potential selection bias was minimised.

A limitation is the substantial heterogeneity among the included studies.

There were insufficient data to undertake subgroup analyses for some types of tests.

Introduction

The number of patients with diabetes is increasing globally, with an estimated 463 million adults diagnosed with diabetes. This number is predicted to exceed 700 million by 2045.1 Type 2 diabetes (T2D), characterised by hyperglycaemic resulting from hyposecretion of insulin and/or insulin resistance, accounts for nearly 90% of all types of diabetes.1 Propelling the surge of diabetes is the increasing prevalence of overweight and obesity. Data from the WHO2 show that nearly 2 billion adults are overweight and more than half a billion worldwide are obese. Furthermore, obesity accounts for 50.9%–98.6% of adults with T2D in Europe and 56.1% in Asia.3 Overweight and obesity contribute to the development of cardiovascular disease, cancer, T2D, hypertension, dyslipidaemia and mental health disorders. The coexistence of excess body weight and diabetes further aggravates the quality of life of individuals and imposes a tremendous burden on the healthcare system. Although various exercise options are available for individuals with either T2D or excess weight, individuals with T2D and concurrent overweight/obesity receive little attention. Measures to support individuals to optimise glycaemic control and weight management remain elusive.

Physical activity (defined as all body movement that increases energy use) and exercise (defined as a structured form of physical activity)4 have been recommended as the key components of lifestyle management for patients with T2D and concurrent overweight/obesity. Combined exercise involves aerobic exercise (repeated and continuous movement of large muscle groups when oxygen supply is sufficient) and resistance exercise (a strength-training workout that uses some form of resistance or tension) performed within the same or separate exercise sessions of a training programme.5 6 Compelling evidence shows that aerobic exercise has an active effect on receptor affinity (adipose tissue, skeletal muscle and insulin receptors), thereby inducing insulin sensitivity and glucose homeostasis.1 7 8 Resistance exercise can enhance muscle strength, insulin sensitivity and muscle rehabilitation.7 8 Current national and international guidelines recommend that people with diabetes should perform combined exercise, integrating both aerobic (at least 150 min per week of moderate-vigorous aerobic activities) and resistance exercise (two sessions per week at least 60 min).8 9 However, in reality, the adoption rate of combined exercise is quite low, and the combined modes have the potential to become excessively burdensome. Moreover, it remains unclear whether the combined exercise modes can exert benefits on glycaemic control and body weight among individuals with T2D and concurrent overweight/obesity.

Therefore, the aim of this systematic review and meta-analysis is to synthesise the best available evidence and explore the effectiveness of combined exercise on glycaemic control, weight loss, insulin sensitivity, blood pressure (BP) and serum lipids among patients with T2D and concurrent overweight/obesity.

Materials and methods

This systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses statement.10

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Eligibility was defined according to the PICOs (patient, intervention, comparison, outcome) framework

Type of participants

(1) T2D patients aged ≥18 years; (2) overweight or obesity indicated by body mass index (BMI) (BMI≥25 kg/m2 for Caucasians or BMI≥23 kg/m2 for Asian subjects).11

Type of intervention and comparison

(1) Included an intervention group performing the combined form of exercise, which included both aerobic (eg, jogging, running, cycling, brisk walking) and resistance (eg, push-ups, abdominal crunch, chest press, leg press, squats, knee extensions) exercise with predefined intensity, frequency and duration; (2) exercise intervention time ≥3 weeks12 and (3) potential comparison groups included any format of exercise intervention, general health counselling or usual care.

Outcomes

Primary outcomes included haemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) and BMI at the data collection timepoint. Secondary outcomes included serum insulin, homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR), systolic blood pressure (SBP), diastolic blood pressure (DBP), triglycerides (TG), total cholesterol (TC), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) or psycho-behavioural outcomes such as exercise performance, muscle strength or performance, exercise adherence, exercise self-efficacy, emotional well-being, anxiety, depression and objective measures (eg, pedometers or accelerometers).

Type of studies

RCTs.

Exclusion criteria

Studies were excluded if (1) participants were diagnosed with type 1 diabetes or gestational diabetes; (2) participants suffered from severe complications that impeded exercise engagement, such as acute infection, diabetic foot, diabetes ketoacidosis, severe hepatorenal insufficiency, diabetic retinopathy or obstacles to limb movement; (3) vague description of exercise intervention in terms of time and type and (4) full texts were not available.

Search strategy and literature selection

The literature retrieval was performed in PubMed, EMBASE, Web of Science, the Cochrane library, WANFANG, CNKI and SinoMed from inception through April 2020 for published studies; OpenGrey and ClinicalTrials.gov were also searched for unpublished studies. The reference lists of eligible publications were also retrieved to identify additional eligible studies. Keywords with the combination of medical subject heading terms were used in the search strategy: aerobic, exercise, training, isometric exercise, physical activity, physical exercise, resistance, strength training, strength exercise, weight lifting, weight bearing, combined exercise, diabetes, DM, T2D, NIDDM, overweight, obese, obesity, BMI, body weight and adiposity (online supplemental file). After removing duplicate records, two reviewers independently selected potential articles by assessing titles and abstracts. Then, full texts were further screened to identify study eligibility; at this stage, the two reviewers checked whether the participants were human subjects with T2D and concurrent overweight/obesity instead of animal model studies or people without T2D and concurrent overweight/obesity, and they eliminated articles that had no desired results shown in the inclusion criteria. Any disagreements or discrepancies regarding the selection of potential studies were resolved through discussion, and a third reviewer was consulted in case of any disagreement.

bmjopen-2020-046252supp001.pdf (92.2KB, pdf)

Data extraction

Two reviewers independently extracted details of the included studies using a structured data extraction form, including the study design, sample size, exercise intervention details, data collection time points, participant characteristics and outcomes (table 1). Any disagreements or discrepancies regarding data extraction were resolved through discussion, and a third reviewer was consulted in case of any disagreement.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the included studies

| Author year |

Country | Sample size (EX/CON) |

Combined exercise intervention | Control | Time points of data collection (week) |

Participant characteristics | Dropout rate (%) |

Outcomes | Adverse events | |||||||||||

| Exercise format | Supervision/facilitator | Exercise type | Intensity | Frequency (days/week) | Duration/session (min) |

Intervention time (weeks) |

Age (year) | BMI (kg/m2) |

T2D duration (years) |

|||||||||||

| AminiLari et al 201720 |

Iran | 30 (15/15) | Centre-based and group-based: each exercise session consisted of three phases—warm up, the main stage and a cool-down period | NR/NR | AE: cycle ergometer RE: leg extension, prone leg curl, abdominal crunch |

AE: 50%–55% of HRmax RE: 50%–55% 1 RM |

3 | 45–70 | 12 | NR | 0.12 | 45–60 | EX 29.0±2.6 CON 28.2±3.7 |

>2 | 6.7 | HOMA-IR, serum insulin, BMI |

NR | |||

| Balducci et al 2010a14 | Italy | 606 (303/303) |

Centre-based and group-based: in metabolic fitness centre | Yes/exercise specialist | AE: treadmill, step, elliptical, cycle ergometer RE: four resistance exercises (eg, chest press, lateral pull down, leg press, trunk flexion for the abdominals) and three stretching position standard care: same as control group |

Low–high intensity | 2 | 75 | 48 | Standard care (counselling and diet management) Counselling: encouraging any type of commuting, occupational, home and leisure time physical activity, counselling was reinforced every 3 months; Diet management: caloric intake reduction, adherence to diet was verified by using food diaries and dietary prescriptions were adjusted at each intermediate visit. |

0.48 | EX 58.8±8.6 CON 58.8±8.5 |

EX 31.2±4.6 CON 31.9±4.6 |

6 (3–10) | 7.1 | HbA1c, HOMA-IR, serum insulin, SBP, DBP, TG, TC, HDL-C, LDL-C, BMI |

Shoulder pain, low back pain, aggravation of pre-existing osteoarthritis, musculoskeletal discomfort |

|||

| Balducci et al 2010b15 | Italy | 42 (22/20) |

Centre-based and group-based: NR | Yes/NR | AE: treadmill, cycloergometer RE: four resistance exercises (eg, chest press, lateral pull down, leg press, trunk flexion for the abdominals) and three stretching position Dietary prescriptions |

AE: 70%–80% VO2max RE: 80% 1 RM |

2 | 60 | 48 | Dietary prescriptions | 0, 12, 24, 36, 48 |

EX 60.6±9.3 CON 61.1±7.1 |

EX 30.5±0.9 CON 30.9±1.1 |

EX 8.5±5.7 CON 7.8±5.2 |

4.8 | HbA1c, HOMA-IR, SBP, DBP, TG, TC, HDL-C, LDL-C, BMI |

Musculo- skeletal injury | |||

| Banitalebi et al 201916 | Iran | 35 (17/18) |

Centre-based and group-based: in a hospital gym | Yes/exercise physiologists | AE: treadmill, cycle ergometer RE: bilateral leg press, lateral pull down, bench press, bilateral biceps curl and bilateral triceps push down |

AE: 60%–70% of HRmax RE: 10–15 RM |

3 | 50 | 10 | Usual medical care and diabetes recommendations for self-management | 0.10 | EX 54.1±5.4 CON 55.7±6.4 |

EX 28.7±4.3 CON 30.1±3.5 |

NR | 20.0 | HbA1c, HOMA-IR, serum insulin, BMI |

Muscle soreness | |||

| Bjorgaas et al 200521 | Norway | 29 (15/14) |

Centre-based and group-based: each exercise session consisted of three phases—warm up, the main stage, a cool-down and stretching period | Yes/physiotherapist | AE: light jogging, co-ordination exercises, knee bends and stretching RE: NR diet information: same as control group |

50%–85% HRmax |

2 | 90 | 12 | Diet information: a plenary session by a clinical nutritionist | 0.12 | EX 57.9±8.0 CON 56.9±7.8 |

EX 31.7±2.6 CON 31.8±3.0 |

EX 2.5 (0.1–17) CON 1.5 (0.1–15) |

10.3 | HbA1c, SBP, DBP |

Achilles tendinitis | |||

| Author year |

Country | Sample size (EX/CON) |

Exercise intervention | Control | Time points of data collection (week) |

Participant characteristics | Dropout rate (%) |

Outcomes | Adverse events | |||||||||||

| Exercise format | Supervision/facilitator | Exercise type | Intensity | Frequency (days/week) | Duration/session (min) |

Intervention time (weeks) |

Age (year) | BMI (kg/m2) |

T2D duration (years) |

|||||||||||

| Johansen et al 201722 | Zealand and Denmark | 98 (64/34) |

Group-based: the geographical location of the participants’ home address | Yes/physiotherapist and trainer | AE: power walking, cycling, jogging uphill or on stairs RE: anterior chain (thigh), posterior chain (thigh), chest, back and shoulders standard care: same as control group |

AE: 60%–90% HRmax RE: 10–12 RM |

5–6 | 30–60 | 48 | Standard care: medical counselling, education in type 2 diabetes and lifestyle advice by the study nurse at baseline and every 3 months for 12 months | 0.48 | EX 53.6±9.1 CON 56.6±8.1 |

EX 31.4±3.9 CON 32.5±4.5 |

EX 5 (3–8) CON 6 (3–9) |

5.1 | HbA1c, serum insulin, SBP, DBP, TG, TC, HDL-C, LDL-C, BMI |

Musculoskeletal pain or discomfort, mild hypotension, insomnia, peripheral oedema | |||

| Leehey et al 201617 | USA | 36 (18/18) |

12 weeks of centre-based exercise followed by 40 weeks of home-based exercise | Yes/trainer | AE: treadmill, elliptical trainer and cycle ergometer RE: using elastic bands, hand-held weights or weight machine Diet management: same as control group |

AE: interval RE: progressive |

Centre-based exercise: 3 Home-based exercise: 3or 6 |

Centre-based: 80–90 Home-based: 60 (3 times) 30 (6 times) |

52 | Diet management: nutritional counselling session at baseline with nine follow-up telephone calls | 0,12,52 | EX 65.4±8.7 CON 66.6±7.5 |

EX 36.2±4.8 CON 37.4±4.2 |

NR | 11.1 | HbA1c, SBP, TG, TC, HDL-C, LDL-C, BMI |

Cardiovascular disease, cervical myelopathy | |||

| Lucotti et al 201118 | Italy | 50 (30/20) |

Centre-based and group-based: in a hospital | Yes/physician | AE: row ergometer and bicycle ergometer RE: arm curls, military press, push-ups, upright rowing, back extension, squats knee extensions, heel raises and bent knee sit-ups Diet management: same as control group |

AE: 70% HRmax RE: 40%–50% of 1 RM |

5 | 45 | 3 | AE plus diet management: AE: 70% HR max 5 days/week,30 min/session; Diet management: hypocaloric diet regime administered under a daily supervision of a dietician |

0.3 | EX 61.5±11.5 CON 58.1±9.9 |

EX 39.9±7.3 CON 38.8±4.5 |

NR | 6.0 | HbA1c SBP, DBP, TG, TC, HDL-C, BMI |

NR | |||

| Otten et al 201719 | Sweden | 32 (16/16) |

Centre-based: in a Sports Medicine unit | Yes/trainer | AE: cross-trainer, cycle-ergometer, cycle-ergometer RE: leg presses, leg curls, hip raises, seated rows, dumbbell rows, shoulder raises, back extensions, burpees, sit-ups and wall ball shots Palaeolithic diet: same as control group |

AE: 40%–100% HRmax RE: NR |

3 | 60 | 12 | Palaeolithic diet, education about the diet and cooked food by a trained dietician at baseline and once a month | 0.12 | EX 61 (58–66) CON 60 (53–64) |

EX 31.7 (29.2–35.4) CON 31.4 (29.4–33.1) |

EX 5.5 (1–8) CON 3 (1–5) |

9.4 | HbA1c, serum insulin, SBP, DBP, TG, TC, HDL-C, LDL-C |

NR | |||

| Vinetti et al 201523 | Italy | 20 (10/10) |

Centre-based: in a hospital-based setting | Yes/trainer | AE: cycling on mechanically braked cycle ergometers RE: major muscle groups (upper limb, lower limb, chest, back and core), using callisthenics, repetitions with ankle weights and dumbbells Standard care: same as control group |

AE: interval RE: progressive |

NR | 55–85 | 48 | Standard care: dietary regimen prescribed by the diabetologist | 0.48 | EX 60.56 ±5.94 CON 57.5±9.46 |

EX 29.7±4.1 CON 29.2±3.11 |

≥2 | 0 | HbA1c, serum insulin, SBP, DBP, TG, TC, HDL-C, BMI |

NR | |||

AE, aerobic exercise; BMI, body mass index; CON, control group; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; EX, exercise group; HbA1c, haemoglobin A1c; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; HOMA-IR, homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance; HR, heart rate; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; NR, not reported; RCT, randomised controlled trial; RE, resistance exercise; RM, repetition maximum; SBP, systolic blood pressure; TC, total cholesterol; T2D, type 2 diabetes; TG, triglycerides; VO2max, maximal oxygen consumption.

Quality assessment

The risk of bias of included studies was assessed using the Cochrane Collaboration’s Risk of Bias assessment tool.13 The quality of studies was judged to have low, unclear, or high risk of bias.

Data analysis

All analyses were performed using RevMan V.5.3 (Cochrane Collaboration, http://ims.cochrane.org/revman). Heterogeneity was assessed using Cochran’s Q test and the I2-test. A random-effects model was applied to calculate the pooled results if I2 ≥50%; otherwise, a fixed-effects model was used. Subgroup analysis on primary outcomes stratified by exercise frequency was conducted. The mean difference (MD) with its corresponding 95% CI was used to calculate the effect size. A two-sided p<0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

Patient and public involvement

No patient involved.

Results

Search outcome

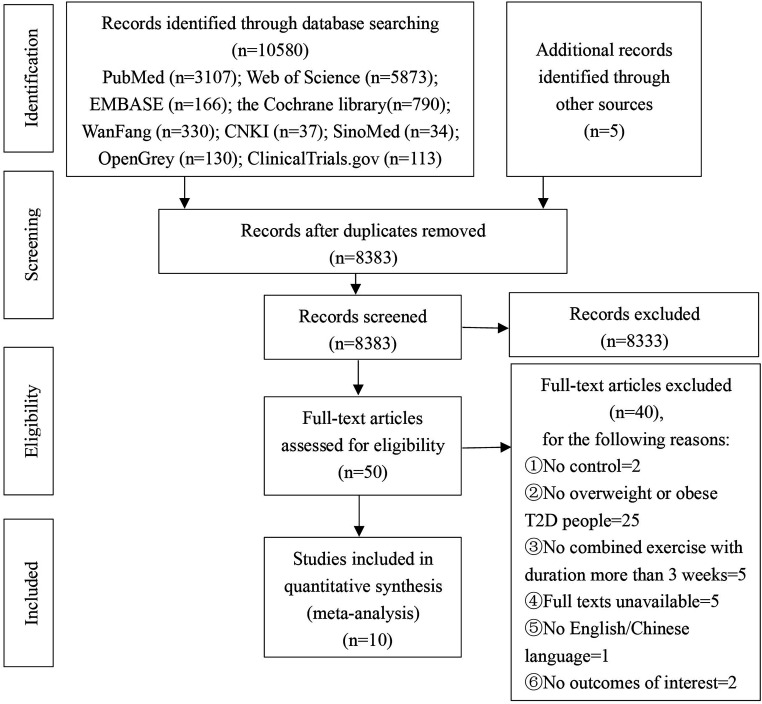

A total of 10 580 records were identified. After duplicate deletion, 8383 articles were screened for titles and abstracts, and 50 articles were further screened for full text. Finally, 10 studies were deemed eligible and included in this meta-analysis (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart for study selection according to PRISMA Declaration 2009. PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses; T2D, type 2 diabetes.

An overview of the characteristics of included studies is summarised in table 1. Across the included studies, the sample size ranged from 20 to 606; the intervention duration ranged from 3 to 52 weeks; the mean (SD) age of participants was similar across the included studies (range: 53.6 (9.1)–66.6 (7.5)) years; the baseline mean (SD) HbA1c ranged from 6.44 (0.33) to 9.50 (0.90); and the baseline mean (SD) BMI ranged from 28.15 (3.72) to 39.9 (7.3) kg/m2.

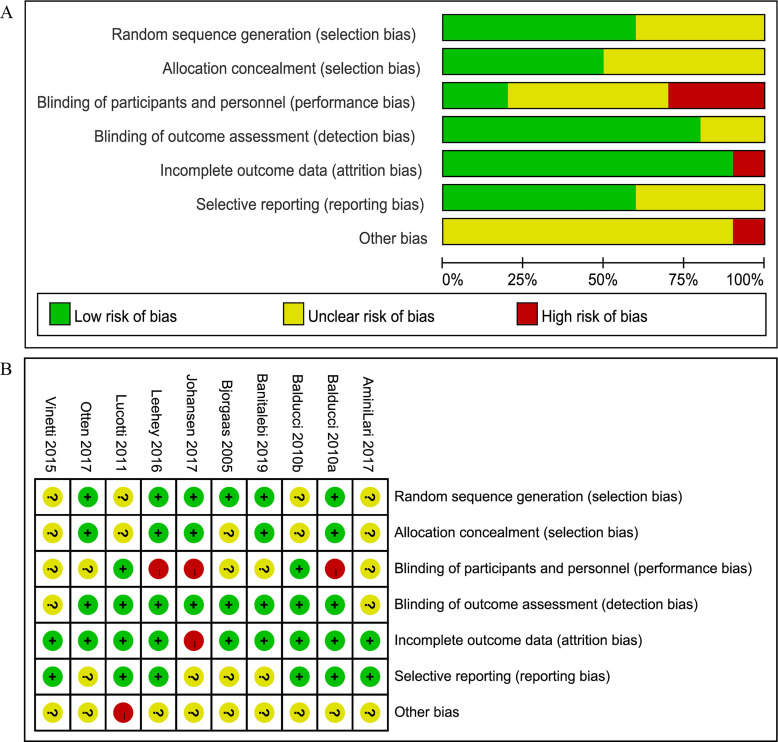

Quality of the included studies

Figure 2 shows the quality assessment of the included studies: six studies were judged to have a low risk of bias,14–19 while the remaining four studies showed uncertain risk of bias.20–23 The following were main sources of bias: lack of blinding of participants and personnel, absence of random sequence generation and allocation concealment and incomplete outcome data. In summary, the quality of the included studies was considered as having moderate risk of bias.

Figure 2.

Quality assessment of the included studies. (A) As percentages across all included studies in risk of bias graph; (B) bias risk of the included studies. ‘+’ indicates Low risk of bias; ‘?’ represents unclear risk of bias; ‘−’ indicates high risk of bias.

Pooled results

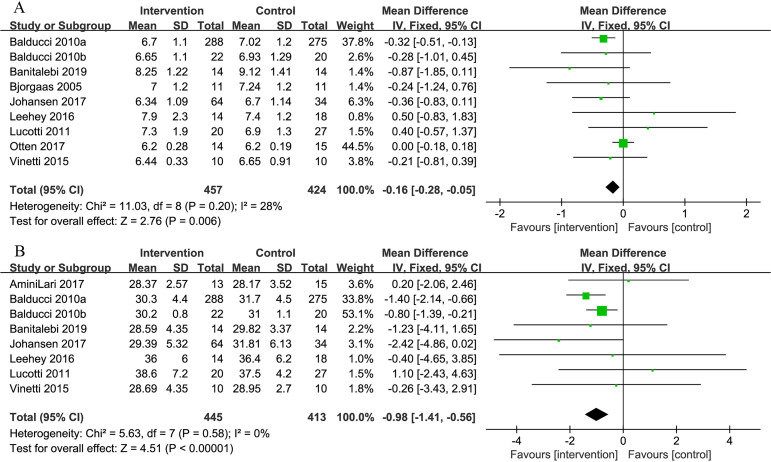

Glycemic control (HbA1c)

Nine studies provided data about the effect of combined exercise on HbA1c. The pooled results showed the combined intervention significantly reduced the HbA1c level of participants, favouring the intervention group, as compared with the control group (MD=−0.16%, 95% CI: −0.28 to −0.05, p=0.006) (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Comparison of HbA1c and body mass index (BMI) between intervention group and control group in patients with T2D and concurrent overweight/obesity. (A) Forest plot of HbA1c; (B) forest plot of BMI; unit of HbA1c is ‘%’; unit of BMI is ‘kg/m2’. HbA1c, haemoglobin A1c; T2D, type 2 diabetes.

Weight loss (BMI)

Eight studies reported changes in BMI. The pooled results showed that combined exercise significantly reduced BMI in the intervention group as opposed to the control group (MD=−0.98 kg/m2, 95% CI: −1.41 to −0.56, p<0.001) (figure 3).

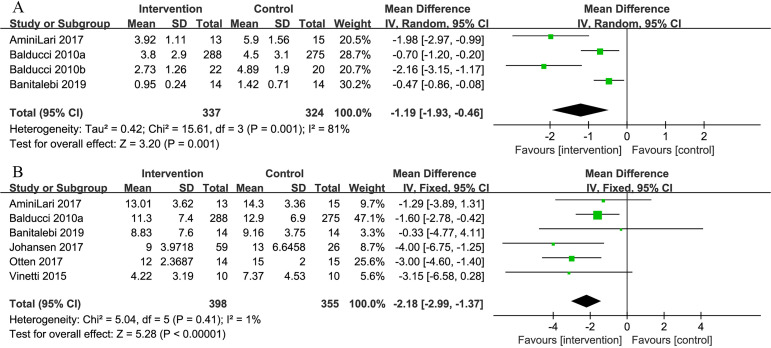

Insulin sensitivity (HOMA-IR, serum insulin)

Four of the 10 studies examined the effectiveness of combined exercise on the HOMA-IR index. The pooled result revealed a significant reduction in the HOMA-IR index favouring the intervention group (MD=−1.19, 95% CI: −1.93 to −0.46, p=0.001) (figure 4).

Figure 4.

Comparison of homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) and serum insulin between intervention group and control group in patients with T2D and concurrent overweight/obesity. (A) Forest plot of HOMA-IR; (B) forest plot of serum insulin. HOMA-IR has no units. Unit of serum insulin is ‘μIU/mL’.

Six studies examined serum insulin. The difference in mean of serum insulin significantly favoured the intervention group (MD=−2.18 μIU/mL, 95% CI: −2.99 to −1.37, p<0.001) (figure 4).

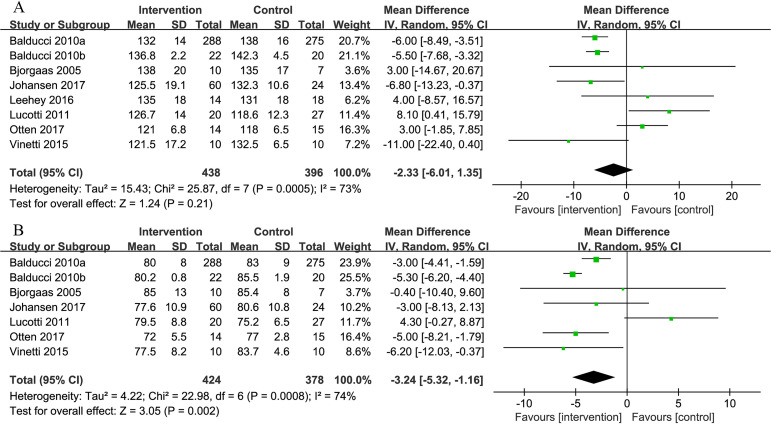

Blood pressure (SBP and DBP)

Eight of the 10 studies measured SBP and seven studies measured DBP. The pooled results showed no difference in SBP between the intervention and control groups (MD=−2.33 mm Hg, 95% CI: −6.01 to 1.35, p=0.21), whereas there was a significant reduction in DBP favouring the intervention group (MD=−3.24 mm Hg, 95% CI: −5.32 to −1.16, p=0.002) (figure 5).

Figure 5.

Comparison of systolic blood pressure (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) between intervention group and control group in patients with T2D and concurrent overweight/obesity. (A) Forest plot of SBP; (B) forest plot of DBP. Units of SBP and DBP are both ‘mm Hg’.

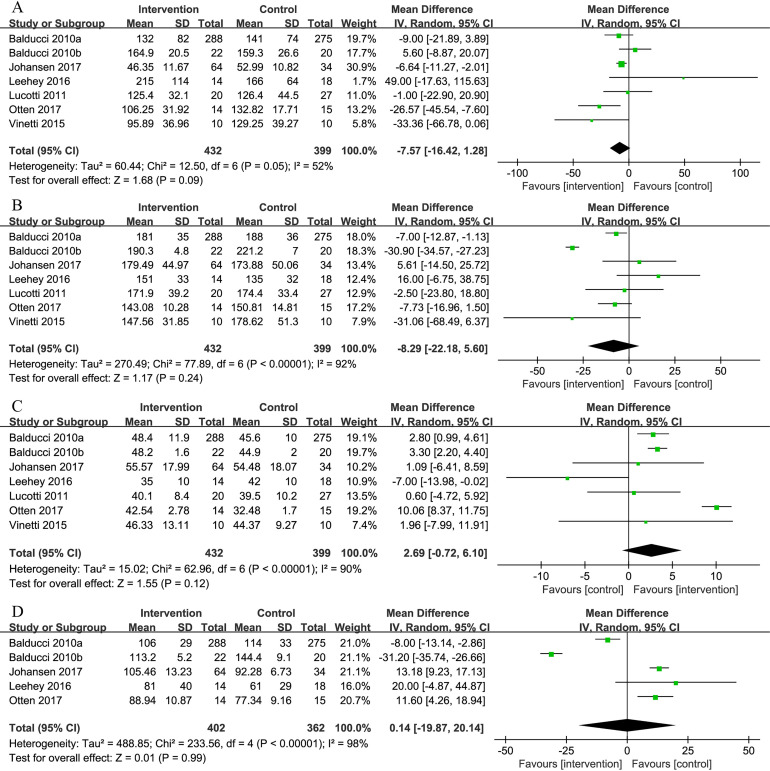

Serum lipids (TG, TC, HDL-C and LDL-C)

Seven studies measured the effectiveness of combined exercise on lipid profiles. The pooled results demonstrated that combined exercise had no significant effect on TG, TC, HDL-C and LDL-C levels (TG: MD=−7.57 mg/dL, 95% CI: −16.42 to 1.28, p=0.09; TC: MD=−8.29 mg/dL, 95% CI: −22.18 to 5.60, p=0.24; HDL-C: MD=2.69 mg/dL, 95% CI: −0.72 to 6.10, p=0.12; LDL-C: MD=0.14 mg/dL, 95% CI: −19.87 to 20.14, p=0.99) (figure 6).

Figure 6.

Comparison of triglycerides (TG), total cholesterol (TC), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) between intervention group and control group in patients with T2D and concurrent overweight/obesity. (A) Forest plot of TG; (B) forest plot of TC; (C) forest plot of HDL-C; (D) forest plot of LDL-C. Units of TG, TC, HDL-C and LDL-C are ‘mg/dL’.

Subgroup analysis (exercise frequency)

The results showed that combined exercise with frequency<3 days/week significantly lowered the HbA1c (MD=−0.31%, 95% CI: −0.50 to −0.13, p<0.001) and BMI (MD=−1.03 kg/m2, 95% CI: −1.49 to −0.57, p<0.001), while combined exercise with frequency≥3 days/week had no effect on HbA1c (MD=0.03%, 95% CI: −0.45 to 0.51, p=0.90) and BMI (MD=0.18 kg/m2, 95% CI: −1.34 to 1.71, p=0.81) (table 2).

Table 2.

Subgroup analysis on primary outcomes

| Subgroups | HbA1c | BMI | |||||||||||

| Included study (n) |

Sample size (EX) |

Sample size (CON) |

Mean difference (95% CI) |

P value | I2 | Included study (n) |

Sample size (EX) |

Sample size (CON) |

Mean difference (95% CI) |

P value | I2 | ||

| Exercise frequency (days/week) |

<3 | 3 | 321 | 306 | −0.31 (−0.50 to 0.13) | <0.001 | 0% | 2 | 310 | 295 | −1.03 (−1.49 to −0.57) | <0.001 | 36% |

| ≥3 | 3 | 44 | 55 | 0.03 (−0.45 to 0.51) | 0.90 | 0% | 4 | 57 | 70 | 0.18 (−1.34 to 1.71) | 0.81 | 0% | |

EX, exercise group; CON, control group; I2, I-squared.

Discussion

The results from this meta-analysis showed that combined exercise was associated with a significant decline in HbA1c, BMI, HOMA-IR index, serum insulin and DBP, indicating the important role of combined exercise in improving glycaemic and weight control and enhancing insulin sensitivity among patients with T2D and concurrent overweight/obesity. However, the results showed that combined exercise had no effect on serum lipids.

Our results showed that combined exercise had a significant effect on HbA1c among adults with T2D and concurrent overweight/obesity. It is important to mention that a 1% absolute reduction in HbA1c is associated with a 21% reduction in the risk of any end point or death related to diabetes.24 Previous meta-analyses of exercise in diabetic patients with or without overweight/obesity have found a positive effect on glycaemic control. Hou25 assessed the effect of combined exercise compared with aerobic exercise among patients with T2D. Their results showed a significant reduction of HbA1c by 0.31%, which was comparable with our finding that combined exercise decreased HbA1c by 0.16%. The meta-analysis by Zou26 identified 13 eligible studies investigating the effect of exercise on patients with T2D and obesity, and the result showed that exercise had no effect on HbA1c in the 3 months intervention subgroup, whereas exercise significantly reduced HbA1c by 0.25%, 0.93% and 0.26% when intervention duration were 4 months, 6 months and 12 months, respectively. This may indicate the effect of exercise in patients with T2D and obesity tends to be steady and persistent. The pooled effect of combined exercise in patients with T2D and concurrent overweight/obesity, however, seems to be much lower than that reported in the first adequately powered randomised controlled trial (RCT)27 that examined the effects of aerobic, resistance and combined exercise in people with T2D. Sigal and colleagues27 found a pronounced reduction (0.9%) in HbA1c with combined exercise. Such discrepancy might be attributed to the long exercise duration (210–270 min/week) of the combined exercise programme, in which participants performed intensive aerobic training programme (75–135 min/week) as well as resistance training programme (135 min/week).28

Our results showed that combined exercise exerted a significant effect on insulin sensitivity on patients with T2D and concurrent overweight/obesity, which was in line with the results of Thaane,29 wherein exercise appeared to improve insulin sensitivity among adults with T2D and concurrent overweight/obesity. Way30 also found that regular exercise had a significant benefit in insulin sensitivity in adults with T2D. They concluded this by synthesising the outcomes of clamps, insulin infusion sensitivity tests, insulin tolerance test and oral glucose tolerance test. The results of Way30 indicated that the durability of training-induced improvement in insulin sensitivity could persist beyond 72 hours after the last exercise session. However, potential heterogeneity was introduced by diverse measurement techniques for insulin sensitivity.

It is generally more difficult for patients with diabetes to lose weight and/or maintain weight loss than non-diabetic individuals. Our results showed that combined exercise achieved a statistically and clinically significant decrease in BMI among adults with T2D and concurrent overweight/obesity. Previous reviews also showed the effect of combined exercise on weight loss by using other obesity indicators. The review by Hou25 showed that combined exercise significantly reduced subcutaneous and visceral adipose tissue, and the results of Pan31 showed that combined exercise safely accentuated reduction in body weight. Whereas the results of Thaane29 suggested that short-term exercise training exerted no significant effect on body weight, BMI and body fat.

Cardiovascular disease was one of the leading reasons for frequent medical consultation and rehospitalisation for adults with T2D and concurrent overweight/obesity.32 BP and serum lipids are vital risk factors for cardiovascular disease, and the importance of managing and maintaining BP and cholesterol levels has been emphasised by the American Diabetic Association (ADA) guideline.33 Evidence has shown the benefits of simultaneous control of HbA1c, BP and lipid levels. Our study found that combined exercise had no effect on SBP and serum lipids, which was contradictory to the findings of Albalawi34 and Bersaoui,35 who reported that combined exercise was related to a statistically significant decline in BP and lipid control among patients with T2D. The possible reason for the discrepancy may be related to the differences of participants’ characteristics. In the current meta-analysis, participants had T2D and were overweight or obese. Low-grade metabolic inflammation in this group of people can induce changes in the neural mechanisms (eg, hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis), which in turn damage the cognitive function of individuals. Cognitive impairments further attenuate individuals’ motivation and ability to engage in self-management activities and maintain therapeutic lifestyles.36–39 Hence, combined exercise may have limited effect on BP and lipid control in people with T2D and concurrent overweight/obesity. More strategies need to be explored to help patients with T2D and concurrent overweight/obesity to simultaneously manage HbA1c, BP and cholesterol levels.

Exercise frequency is a pivotal determinant which moderates the effect of combined exercise on glycaemic control in patients with T2D and concurrent overweight/obesity.40 41 Our study showed that combined exercise had significant effects on HbA1c and BMI only in subgroup with exercise frequency less than 3 days/week. We would attribute such results to inherent differences between studies with exercise frequency <3 days/week and ≥3 days/week. Specifically, subjects in the studies with exercise frequency more than 3 days/week tended to perform short-duration exercise (3 weeks, 12 weeks), which was likely not enough to make a difference in outcomes. While subjects14 15 23 in the study with exercise frequency less than 3 days/week had been offered with long-term (48 weeks) exercise under supervision. Long-term exercise sessions and professional supervision were identified as important factors associated with prominent improvement of glycaemic and weight control.26 31 Additionally, Balducci14 15 even implemented diet management in addition to physical activity counselling. Thus, the results of subgroup analysis should be interpreted with caution.

Direction for future research and practice

Considering the benefits of combined exercise, it might be helpful to recommend combined exercise for patients with T2D and concurrent overweight/obesity to improve glycaemic and weight control and decrease insulin resistance. Physical activity counselling, psycho-educational interventions, mobile technologies and peer support groups could be integrated into the exercise to improve the adoption rate of combined exercise.42 Although there are ADA, American College of Sports Medicine and International Diabetes Federation exercise recommendations for diabetic patients,8 9 43 there is little evidence to indicate the ideal exercise duration, exercise intensity and exercise time that would be most appropriate for patients with T2D and concurrent overweight/obesity. Optimal exercise frequency and duration that would be beneficial for patients with T2D and concurrent overweight/obesity requires further investigation. According to the features of effective exercise interventions among the included studies, most research studies performed centre-based exercise with supervision. Hence, we recommend this kind of intervention in future studies to achieve greater metabolic effects.

Limitations

Our study has some limitations. First, the intervention components of combined exercise in terms of intervention frequency, intensity, duration and time were inconsistent among the included studies and there was substantial heterogeneity among the trials in the meta-analysis. The results, therefore, should be interpreted with caution. Second, only 10 studies met the inclusion criteria and were eligible for the meta-analysis. Some well-conducted and important RCTs were excluded because of not focusing on combined exercise or targeting patients with T2D and concurrent overweight/obesity.27 44 45 Third, the effectiveness of combined exercise observed in this meta-analysis should be interpreted with caution as the majority of the participants (~62%) included in this analysis were from a single study called the ‘Italian diabetes and exercise study’ with significant positive findings.11 Additionally, the patients in our study were mainly middle-aged and elderly subjects; hence, the effect of combined exercise on young subjects with T2D and concurrent overweight/obesity remains unclear. Finally, the T2D duration varied from 0.1 to 17 years or more and which subgroup of patients could benefit more from the combined exercise remains unclear.

Conclusions

This systematic review provides useful information for the clinical application of the combined exercise in the management of patients with T2D and concurrent overweight/obesity. The results show clear evidence that combined exercise intervention has positive effects on improving glycaemic and weight control, and enhancing insulin sensitivity among patients with T2D and concurrent overweight/obesity. More RCTs with robust methodological design, and more comprehensive body composition measurements are needed to elaborate the intervention effects and mechanism. This review also highlights the need for further studies to investigate the ideal duration, intensity and time of combined exercise for patients with T2D and concurrent overweight/obesity.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: XZ, QH, YZ and LC conceived the research; XZ, QH, YZ and LC established eligibility criteria and search strategy; XZ and QH worked on literature selection, data extraction and quality assessment; XZ, QH and LC performed statistical analysis; XZ wrote paper; XZ and LC had primary responsibility for final content; all authors read the manuscript and approved the final draft.

Funding: This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number: 71904214) and Medical Science and Technology Research Foundation of Guangdong Province (grant number: A2019003).

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplemental information.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

Ethics approval

This study does not require ethics approval as it is a review based on published studies.

References

- 1.International Diabetes Federation . IDF diabetes atlas. 9th edn, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization . Overweight and obesity. Available: https://www.who.int/gho/ncd/riskfactors/overweighttext/en/

- 3.Colosia AD, Palencia R, Khan S. Prevalence of hypertension and obesity in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in observational studies: a systematic literature review. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes 2013;6:327–38. 10.2147/DMSO.S51325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Caspersen CJ, Powell KE, Christenson GM. Physical activity, exercise, and physical fitness: definitions and distinctions for health-related research. Public Health Rep 1985;100:126–31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Colberg SR, Sigal RJ, Yardley JE, et al. Physical activity/exercise and diabetes: a position statement of the American diabetes association. Diabetes Care 2016;39:2065–79. 10.2337/dc16-1728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hurst C, Weston KL, McLaren SJ, et al. The effects of same-session combined exercise training on cardiorespiratory and functional fitness in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Aging Clin Exp Res 2019;31:1701–17. 10.1007/s40520-019-01124-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.American Diabetes Association . 3. Prevention or delay of type 2 diabetes: standards of medical care in diabetes-2020. Diabetes Care 2020;43(Suppl. 1:S32–6. 10.2337/dc20-S003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.American Diabetes Association . 5. Lifestyle management: standards of medical care in diabetes-2019. Diabetes Care 2019;42:S46–60. 10.2337/dc19-S005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Colberg SR, Sigal RJ, Fernhall B, et al. Exercise and type 2 diabetes: the American college of sports medicine and the American diabetes association: joint position statement executive summary. Diabetes Care 2010;33:2692–6. 10.2337/dc10-1548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021;372:n71. 10.1136/bmj.n71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.World Health Organization . Obesity and overweight, 2020. Available: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight

- 12.Oliveira C, Simões M, Carvalho J, et al. Combined exercise for people with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2012;98:187–98. 10.1016/j.diabres.2012.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.The Cochrane Collaboration . Higgens JPT, Green LA, eds. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 5.1.0, 2011: 174–219. http://www.cochrane-handbook.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 14.Balducci S, Zanuso S, Nicolucci A, et al. Effect of an intensive exercise intervention strategy on modifiable cardiovascular risk factors in subjects with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a randomized controlled trial: the Italian diabetes and exercise study (ides). Arch Intern Med 2010;170:1794–803. 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Balducci S, Zanuso S, Nicolucci A, et al. Anti-Inflammatory effect of exercise training in subjects with type 2 diabetes and the metabolic syndrome is dependent on exercise modalities and independent of weight loss. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 2010;20:608–17. 10.1016/j.numecd.2009.04.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Banitalebi E, Kazemi A, Faramarzi M, et al. Effects of sprint interval or combined aerobic and resistance training on myokines in overweight women with type 2 diabetes: a randomized controlled trial. Life Sci 2019;217:101–9. 10.1016/j.lfs.2018.11.062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leehey DJ, Collins E, Kramer HJ, et al. Structured exercise in obese diabetic patients with chronic kidney disease: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Nephrol 2016;44:54–62. 10.1159/000447703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lucotti P, Monti LD, Setola E, et al. Aerobic and resistance training effects compared to aerobic training alone in obese type 2 diabetic patients on diet treatment. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2011;94:395–403. 10.1016/j.diabres.2011.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Otten J, Stomby A, Waling M, et al. Benefits of a paleolithic diet with and without supervised exercise on fat mass, insulin sensitivity, and glycemic control: a randomized controlled trial in individuals with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2017;33. 10.1002/dmrr.2828. [Epub ahead of print: 30 06 2016]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.AminiLari Z, Fararouei M, Amanat S, et al. The effect of 12 weeks aerobic, resistance, and combined exercises on Omentin-1 levels and insulin resistance among type 2 diabetic middle-aged women. Diabetes Metab J 2017;41:205–12. 10.4093/dmj.2017.41.3.205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bjørgaas M, Vik JT, Saeterhaug A, et al. Relationship between pedometer-registered activity, aerobic capacity and self-reported activity and fitness in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab 2005;7:737–44. 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2004.00464.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johansen MY, MacDonald CS, Hansen KB, et al. Effect of an intensive lifestyle intervention on glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2017;318:637–46. 10.1001/jama.2017.10169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vinetti G, Mozzini C, Desenzani P, et al. Supervised exercise training reduces oxidative stress and cardiometabolic risk in adults with type 2 diabetes: a randomized controlled trial. Sci Rep 2015;5:9238. 10.1038/srep09238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stratton IM, Adler AI, Neil HA, et al. Association of glycaemia with macrovascular and microvascular complications of type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 35): prospective observational study. BMJ 2000;321:405–12. 10.1136/bmj.321.7258.405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hou Y, Lin L, Li W, et al. Effect of combined training versus aerobic training alone on glucose control and risk factors for complications in type 2 diabetic patients: a meta-analysis. Int J Diabetes Dev Ctries 2015;35:524–32. 10.1007/s13410-015-0329-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zou Z, Cai W, Cai M, et al. Influence of the intervention of exercise on obese type II diabetes mellitus: a meta-analysis. Prim Care Diabetes 2016;10:186–201. 10.1016/j.pcd.2015.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sigal RJ, Kenny GP, Boulé NG, et al. Effects of aerobic training, resistance training, or both on glycemic control in type 2 diabetes: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2007;147:357–69. 10.7326/0003-4819-147-6-200709180-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Larose J, Sigal RJ, Khandwala F, et al. Associations between physical fitness and HbA₁(c) in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia 2011;54:93–102. 10.1007/s00125-010-1941-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thaane T, Motala AA, McKune AJ. Effects of short-term exercise in overweight/obese adults with insulin resistance or type 2 diabetes: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. J Diabetes Metab 2018;9. 10.4172/2155-6156.1000816 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Way KL, Hackett DA, Baker MK, et al. The effect of regular exercise on insulin sensitivity in type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Metab J 2016;40:253–71. 10.4093/dmj.2016.40.4.253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pan B, Ge L, Xun Y-Q, et al. Exercise training modalities in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2018;15:72. 10.1186/s12966-018-0703-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Costanzo P, Cleland JGF, Pellicori P, et al. The obesity paradox in type 2 diabetes mellitus: relationship of body mass index to prognosis: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med 2015;162:610–8. 10.7326/M14-1551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.American Diabetes Association . 10. Cardiovascular disease and risk management: standards of medical care in diabetes-2020. Diabetes Care 2020;43:S111–34. 10.2337/dc20-S010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Albalawi H, Coulter E, Ghouri N, et al. The effectiveness of structured exercise in the South Asian population with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review. Phys Sportsmed 2017;45:408–17. 10.1080/00913847.2017.1387022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bersaoui M, Baldew S-SM, Cornelis N, et al. The effect of exercise training on blood pressure in African and Asian populations: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2020;27:457–72. 10.1177/2047487319871233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lowe CJ, Reichelt AC, Hall PA. The prefrontal cortex and obesity: a health neuroscience perspective. Trends Cogn Sci 2019;23:349–61. 10.1016/j.tics.2019.01.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Castanon N, Luheshi G, Layé S. Role of neuroinflammation in the emotional and cognitive alterations displayed by animal models of obesity. Front Neurosci 2015;9:229. 10.3389/fnins.2015.00229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ottino-González J, Jurado MA, García-García I, et al. Allostatic load and executive functions in overweight adults. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2019;106:165–70. 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2019.04.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cai X, Hu D, Pan C, et al. The risk factors of glycemic control, blood pressure control, lipid control in Chinese patients with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes _ a nationwide prospective cohort study. Sci Rep 2019;9:7709. 10.1038/s41598-019-44169-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Umpierre D, Ribeiro PAB, Schaan BD, et al. Volume of supervised exercise training impacts glycaemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review with meta-regression analysis. Diabetologia 2013;56:242–51. 10.1007/s00125-012-2774-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cradock KA, ÓLaighin G, Finucane FM, et al. Behaviour change techniques targeting both diet and physical activity in type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2017;14:18. 10.1186/s12966-016-0436-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fletcher GF, Landolfo C, Niebauer J, et al. Promoting physical activity and exercise: JACC health promotion series. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018;72:1622–39. 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.08.2141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Aschner P. New IDF clinical practice recommendations for managing type 2 diabetes in primary care. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2017;132:169–70. 10.1016/j.diabres.2017.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Church TS, Blair SN, Cocreham S, et al. Effects of aerobic and resistance training on hemoglobin A1c levels in patients with type 2 diabetes: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2010;304:2253–62. 10.1001/jama.2010.1710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cuff DJ, Meneilly GS, Martin A, et al. Effective exercise modality to reduce insulin resistance in women with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2003;26:2977–82. 10.2337/diacare.26.11.2977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2020-046252supp001.pdf (92.2KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplemental information.