Abstract

We examined the longitudinal relation between behavioral inhibition (BI) and social anxiety symptoms and behavior, and the mediating role of emotion regulation (ER). Moreover, we investigated the influence of parenting behavior on the development of ER strategies. Participants were 291 children (135 male) followed longitudinally from 2 to 13 years. Mothers were predominantly well-educated and non-Hispanic Caucasian. Children were screened for BI using maternal-report and observational measures (ages 2 and 3), parenting behavior was observed while children and their mothers participated in a fear-eliciting task (age 3), ER strategies were observed while children completed a disappointment task (age 5), and socially anxious behavior was measured via multi-method assessment at 10 and 13 years. Children who exhibited high BI in early childhood exhibited more socially anxious behavior across ages 10 and 13, and there was a significant indirect effect of BI on socially anxious behavior through ER strategies. Children who were high in BI, demonstrated less engaged ER strategies during the disappointment task, which in turn predicted more socially anxious behavior. Furthermore, parenting behavior moderated the pathway linking early BI and ER strategies to social anxiety outcomes; such that children who exhibited high BI and who received more affectionate/oversolicitous behavior from their mother, displayed less engaged ER strategies and more socially anxious behavior than children low in BI or low in oversolicitous parenting behaviors. These findings expand on our understanding of the role that ER strategies and parenting play in the developmental pathway linking early BI to future social anxiety outcomes.

Keywords: temperament, emotion regulation, parenting, social anxiety

Introduction

Social anxiety disorder (SAD) is recognized as a prevalent and severely impairing psychiatric disorder (Wittchen et al., 1999). Fearful temperament – particularly in the form of behavioral inhibition (BI) – is one of the strongest early predictors of SAD (Clauss & Blackford, 2012; Sandstrom et al., 2020). BI is a temperament characterized by fearful disposition and withdrawal in unfamiliar contexts and situations (Kagan et al., 1984). Children who strongly and consistently exhibit BI early in life are at increased risk for developing anxiety symptoms and disorders in childhood and adolescence, especially social anxiety (Chronis-Tuscano et al., 2009; Pérez-Edgar & Fox, 2005). However, not all behaviorally inhibited children display continuity of this temperamental trait, nor do all behaviorally inhibited children go on to develop social anxiety in middle childhood and adolescence. Thus, it is essential to better understand developmental pathways that link early BI to social anxiety, which may help identify malleable predictors and moderators to inform intervention efforts (Degnan & Fox, 2007).

Emotion regulation (ER) strategies may be one mechanism through which early BI confers risk for later social anxiety symptoms and behaviors. In adults, social anxiety is associated with deficits in ER and the use of maladaptive ER strategies characterized by avoidance or passive tolerance (Goldin et al., 2014; Werner et al., 2011). In children aged 8–16 years, difficulties in emotion regulation processes (e.g., inability to engage in goal-directed behavior and non-acceptance) longitudinally predict greater social anxiety symptoms 36 months later (Schneider et al., 2018). Previous research has identified three specific forms of ER strategies in children: active, passive, and disruptive strategies. Active ER strategies (e.g., seeking social support and problem solving) entail deliberately engaging with the emotion-eliciting stimulus in an attempt to change the situation and reduce stress (Penela et al., 2015). Conversely, passive ER strategies (e.g., self-soothing behavior or passive tolerance) entail disengaging from the environment to cope with the source of distress (Feng et al., 2008; Walker et al., 2014). Finally, disruptive ER strategies involve responding in a physically or verbally aggressive manner to the distressing stimulus (Calkins et al., 1999). Overall, active strategies are considered most adaptive as they tend to be more effective at regulating emotions compared to disruptive strategies, which are associated with observed peer conflict. Similarly, passive strategies may provide relief to negative emotions in the short-term, but are less effective than active strategies in the long-term and predict increased anxiety symptoms over time (Aldao et al., 2010; Calkins et al., 1999; Compas et al., 2017).

A growing body of literature suggests that children exhibiting an inhibited or shy temperament have a tendency to utilize less active and more passive strategies to regulate their emotions. For example, in a sample of young boys, maternal-reported shy temperament at age 1.5 years was associated with children’s use of passive ER strategies (e.g., physical comfort seeking and passive waiting) during a delay of gratification task two years later (Feng et al., 2011). In another study, highly inhibited preschoolers engaged in more comfort-seeking behaviors from their mothers and less active regulatory strategies (i.e., task engagement/orientation) during a fear-eliciting task (Root et al., 2015). Shy or inhibited children often react more intensely in emotionally charged situations, which may hinder their ability to employ active strategies to regulate their emotions (Hane et al., 2008).

In addition, previous developmental research suggests that ER strategies mediate the relation between early shy and/or inhibited temperament and later difficulties with socioemotional functioning. In a sample of preschool-aged children (i.e., 2.5 to 5 years), researchers examined the role of parent-reported ER strategies (e.g., problem solving, self-directed speech, and information-seeking behaviors) in shy children’s social adjustment four months later (Hipson et al., 2019). They found that shyness was significantly and positively related to asocial behavior and negatively associated with active ER strategies (e.g., self-directed speech, information gathering, and constructive coping), and these active ER strategies mediated the link between shyness and indicators of poor social behavior. Moreover, another study found that ER strategies measured during a disappointment task at 5 years mediated the relation between early BI at 2 and 3 years and social competence at 7 years, such that early BI predicted the use of less active and more passive ER strategies during a disappointment task, and more active ER strategies predicted higher levels of social competence (Penela et al., 2015). These findings demonstrate the importance of ER strategies in the link between early shy and/or fearful temperament and social functioning; however, whether or not these findings extend to socially anxious outcomes, incorporating symptomatology, behavioral observation, and clinical evaluation, has not been examined. This marks an important gap in the literature given that social competence is only one component of socially anxious behavior and observed behavior in the context of peers does not fully capture anxious feelings and symptoms, which are not easily measured until later childhood or early adolescence. The ability to engage in adaptive ER strategies may be one of the developmental pathways linking early temperamental risk to social anxiety. Thus, the first aim of this study was to extend previous findings by examining the role of ER strategies in the relation between early fearful temperament and socially anxious behavior in late childhood and early adolescence.

Parents also play a major role in the development of children’s ER. According to Morris and colleagues’ (2007) tripartite model, parents influence the development of children’s ER via three mechanisms: observation and modeling of parent’s displays of ER, emotion-related parenting practices and behaviors, and the overall emotional climate of the family. Of particular interest for the current study, research has shown that parenting behaviors related to emotion socialization, such as emotion-coaching, teaching about specific ER strategies, and parental reactions to their child’s displays of emotion, shape children’s understanding about emotions and their strategies for responding to them (Eisenberg et al., 1998; Gottman et al., 1996; Morris et al., 2011). It is important to note, however, that the effects of certain emotion-related parenting behaviors may be dependent on child characteristics, including developmental status and temperament (Morris et al., 2007). In toddlerhood, children become increasingly able to deliberately employ ER strategies with a significant increase between 3 and 5 years (Kopp, 1989; Morales & Fox, 2019). Because parenting behavior is one of the main mechanisms of influences on the development of children’s ER (Kopp, 1982; Morris et al., 2007), we observed parenting behavior during a fear-eliciting task at 3 years and measured ER strategies at 5 years.

It is well established that child characteristics (e.g., temperament) and the caregiving environment (e.g., caregiver characteristics and parenting behaviors) are dynamically-related over time and jointly contribute to the child’s developmental outcomes (Sameroff & Mackenzie, 2003). For example, past research has demonstrated that parental history of BI moderates the association between early childhood BI and social anxiety in late childhood (Stumper et al., 2017). Moreover, parents of behaviorally inhibited children often engage in a pattern of parenting marked by highly affectionate behaviors and oversolicitousness (e.g., excessive or inappropriate comforting), such that parents attempt to comfort or shield their fearful children in an overly protective manner in situations that might elicit fear or anxiety (Rubin & Burgess, 2002). Previous literature characterizes oversolicitous parenting as displays of warmth, intrusiveness, and restrictiveness during children’s ongoing activities in order to avoid potentially upsetting experiences (Rubin et al., 1997; Rubin & Burgess, 2002). Parents tend to take control in potentially fearful situations at times when it is neither warranted nor sensitive to do so. Thus, we chose to focus on parenting behavior during a novel and unpredictable situation, that despite potentially eliciting fear or discomfort in some children, presented no actual danger, but may evoke protective parenting behaviors likely to impact the continuity of inhibited behavior and the development of social anxiety over time. For children displaying consistent BI from an early age, parents who engage in behaviors that are highly affectionate/oversolicitous may actually contribute to the stability of their child’s inhibition by not allowing them to engage in and practice important ER strategies for themselves or to gain confidence in their own coping strategies. In turn, these parenting behaviors may have unintended consequences, potentially leading to the development and maintenance of more severe socially anxious symptoms and behavior, in addition to a hindrance on a child’s independence, which becomes more impairing as they approach adolescence.

Multiple studies have demonstrated that this type of highly affectionate/oversolicitous parenting behavior can be detrimental to adaptive social development among socially withdrawn and behaviorally inhibited children (e.g., Lewis-Morrarty et al., 2012). One study found that socially wary toddlers were more likely to exhibit inhibited behavior with a same-age peer if their mothers were also more intrusively controlling and highly affectionate during a free-play session (Rubin et al., 1997). Another study identified maternal oversolicitousness as a moderator of the relation between peer inhibition and social reticence, such that behaviorally inhibited children at age 2 were likely to show social reticence at age 4 only if their mothers exhibited oversolicitous and/or derisive behaviors during free-play and clean-up tasks at age 2 (Rubin et al., 2002). Thus, previous findings suggest that highly affectionate/oversolicitous parenting behavior may interact with child fearful temperament to maintain inhibited behavior over time, yet no study has prospectively examined whether highly affectionate/oversolicitous parenting behavior moderates the association between early BI and ER strategy use. It is possible that high levels of affectionate/oversolicitous parenting behaviors encourage children exhibiting high BI to remain dependent on parents, reinforcing children’s avoidance and hampering the development of constructive ER strategies, which, in turn, may contribute to the persistence of fearful behavior and the development of social anxiety symptoms and behavior. Thus, the second aim of this study was to examine how specific parenting behaviors observed during toddlerhood influence the development of ER strategies among children who are high on BI, and thereby also better understand their future anxiety.

Current Study

Previous studies conducted in early and middle childhood suggest that ER strategies mediate the relation between early behaviorally inhibited temperament and poor socioemotional functioning. However, it is unclear if this relation contributes to the development of more severe socially anxious symptoms and behavior. The current study extends the findings of previous studies by examining the associations between BI (ages 2 and 3), ER strategies (age 5), and socially anxious behavior (ages 10 and 13). To parallel work done in a previous study (Penela et al., 2015), we coded the frequency of active and passive ER strategies in a laboratory-based disappointment task at age 5 in order to examine children’s ER strategy repertoire (i.e., the kinds of ER strategies they use most often). Because most children utilize both types of strategies, we created a composite that combined the frequency of specific and observable active and passive strategies (reverse coded) in order to form a novel composite of engaged ER. Engaged ER reflects more frequent attempts to deliberately engage with the emotion-eliciting stimulus to change the situation and fewer instances of disengagement or passive tolerance of the situation (i.e., the use of more active and less passive strategies). We examined if engaged ER strategies are one mechanism through which early BI confers risk for later socially anxious behavior.

We hypothesized that higher levels of BI in toddlerhood (age 2 and 3 years) would be prospectively associated with less engaged ER strategies (i.e., lower levels of active strategies and higher levels of passive strategies) during a disappointment task at age 5, as well as more socially anxious behavior in late childhood (age 10 years) and adolescence (age 13 years). Moreover, we hypothesized that less engaged ER strategies would predict more socially anxious behavior. Finally, we hypothesized that less engaged ER strategies would mediate the relation between BI and socially anxious behavior.

The second aim of the current study was to conduct a moderated mediation analysis to better understand how different parenting behaviors may contribute to the development of ER strategies of behaviorally inhibited children, and how this interaction may influence later socially anxious behavior. We hypothesized that maternal parenting behaviors during a fear-eliciting task at age 3 would moderate the relation between BI at ages 2 and 3 and ER strategies at age 5. Specifically, we hypothesized that oversolicitous parenting behaviors during a fear-eliciting task would moderate the relation such that children high in BI and who received more oversolicitous parenting behaviors at age 3 would use less engaged ER strategies at age 5. In addition to the moderating effect of parenting on the relation between BI and ER strategies, we predicted that oversolicitous parenting would moderate the strength of the developmental pathway linking early BI to future socially anxious behavior via children’s ER strategies.

1. Methods

Participants

Participants for this study were drawn from a larger, longitudinal investigation of temperament and social development. The current study included 291 children (135 male, 156 female). Based on the initial sample demographics, mothers were primarily Caucasian (69.4%), African American (16.5%), Hispanic (7.2%), Asian (3.1%), other (3.4%), and 0.3% did not report race or ethnicity. Mothers were also highly educated: 16.2% high school graduates, 41.9% college graduates, 35.7% graduate school graduates, 5.5% other, and 0.7% did not report education. Families were recruited using commercially available mailing lists targeting households with very young infants (Hane et al., 2008). At 4 months of age, 779 infants were brought to the laboratory and observed during a temperament screening to assess their reactions to novel auditory and visual stimuli. Infants with higher levels of reactivity were oversampled to represent a wider range of temperamental reactivity compared to a randomly selected community sample. Of these children, 291 were selected to participate in the larger study based on displays of positive and negative affect and motor reactivity to the stimuli, creating 106 positive reactive (i.e., higher motor activity and higher positive affect), 116 negative reactive (i.e., higher motor activity and higher negative affect), and 69 control group infants who participated in subsequent assessments (see Hane et al., 2008 for more details on the screening and recruitment strategy). The selected families did not differ from the larger screening sample in child gender or maternal ethnicity and education (p’s > .13).

Of the original sample (N=291), 268 had data on the BI variable at the 2- and 3- year visit, 205 had data on parenting behaviors at the 3-year visit, 206 had data on ER strategy use at the 5-year visit, and 209 had data on the socially anxious behavior factor at the 10-year or 13-year visit (see supplement for sample sizes for each component of composite measures; Table S1). Examining the patterns of missing data revealed that mother’s ethnicity (non-Hispanic Caucasian vs. other minority groups) was associated with missing data on the BI variable (χ2 (1) = 12.64, p < .001) and the oversolicitous parenting variable (χ2 (1) = 6.43, p = .01) – such that children with available data on these measures were more likely to have non-Hispanic Caucasian mothers. Because of this, maternal ethnicity was included as a covariate in the SEM analyses. Missing data on all other variables was not associated with children’s gender, mother’s ethnicity, maternal education, or BI (p’s > .10).

Procedure

BI was measured at ages 2 and 3 using maternal-report questionnaires and observational measures of children’s behavior during the presentation of novel social and nonsocial stimuli. At the 3-year assessment, children also engaged in an unpredictable toy task with their mother present, during which measures of parenting were coded (Kochanska, 1995). Children returned to the lab at age 5 to complete a disappointment task, during which ER strategies were coded (Cole, 1986; Cole et al., 2004). Finally, as a measure of socially anxious behavior, we utilized a robust multi-method measure that incorporates observed socially anxious behavior as well as parent and child reports, and clinical diagnoses across late childhood and adolescence (10 and 13 years). All methods for recruitment and study procedures were approved by the institutional review board (IRB) of the University of Maryland, Trajectories of Behavioral Inhibition and Risk for Anxiety (312425).

Measures

Temperament –

BI was assessed at ages 2 and 3 using behavioral observations of children’s response to unfamiliar stimuli (Calkins et al., 1996; Kagan et al., 1984). The unfamiliar stimuli presented to the children included an adult stranger, a robot, and an inflatable tunnel. The adult stranger sat quietly for one minute, played with a truck for one minute, and then (if the child had not yet approached) invited the child to join her for play for one minute. Children were then presented with an 18-inch-tall battery-operated robot, which made loud noises, had flashing lights, and moved unpredictably around the room. Finally, an inflatable tunnel was presented to the child and a research assistant encouraged the child to crawl through it. Each task was reliably coded by scoring (in seconds): (1) latency to vocalize, (2) latency to approach/touch the stimuli, and (3) duration of time spent in proximity to mother (ICCmean=.92; ICCrange=.72–1.00; for more details, see Degnan et al., 2014). A composite measure of behavioral inhibition was computed by averaging the standardized scores for each task at each age. For each age, the scores of each behavioral task (i.e., the adult stranger, the robot, and the inflatable tunnel) were significantly correlated (rmean=.40; ICCrange=.34–.48), yielding composites with acceptable reliability (α24mo = .63; α36mo = .69). The BI composites at the two ages were also significantly correlated (r = .34, p < .001).

The Toddler Behavior Assessment Questionnaire (TBAQ) was also used to measure BI at ages 2 and 3. The TBAQ is a valid and reliable questionnaire for use with 16- to 36-month-old children (Goldsmith, 1996). Using 7-point Likert scales, mothers rated their child on six dimensions of temperament. Of interest to the current study was the social fearfulness subscale, which measures inhibition, distress, and shyness in novel situations (α24mo = .83; α36mo = .88). A composite measure of BI was created based on observations of BI and maternal report at ages 2 and 3 years to reflect a broader measure of child temperament. Behavioral coding and parental reports of BI had normal distributions (Skewness < |0.29| and Kurtosis < |.54|) and were significantly correlated (r = .42, p < .001). This composite measure is a well-established measure of BI, which has been used in multiple studies (e.g., Troller-Renfree et al., 2019a; Troller-Renfree et al., 2019b; Walker et al., 2014). Moreover, parent-report and observational measures have their respective strengths and limitations. On the one hand, purely behavioral measures are more objective, but are still limited to the laboratory and may be affected by examiner observation. On the other hand, parent report provides information about child behavior outside the laboratory but may subject to reporter bias (Olino et al., 2020). Thus, the combination of parent report and observational measures provides a more robust measurement of BI. Lastly, examining the results with a BI composite that just included observed BI produced similar results that lead to the same conclusions – suggesting that our findings are robust to the specific measure of BI (see supplement; Table S2).

Parenting –

During the 36-month home visit, children participated in the Unpredictable Toy task with their caregiver present. This task aimed to elicit moderate levels of fear and/or discomfort in the child (Kochanska, 1995). The home visit started with a 7-minute free play segment, followed by a series of tasks that the mother and the child completed together. The Unpredictable Toy task occurred towards the middle of the visit and lasted for three minutes. An experimenter brought a mechanical toy dinosaur into the room that made unpredictable sounds and movements, turned it on, and placed it on the floor in front of the mother and child. The mother and child were told by the examiner that the toy was touch- and sound-activated and they were instructed to play with the toy for a few minutes.

The presence or absence of nine maternal behaviors during each 30-second epoch were coded, for a total of six epochs. The coding scheme was based on the literature regarding common maternal responses to toddlers’ expressions of negative emotions, and it allowed for multiple maternal behaviors to be recorded in any of the six epochs (Penela, 2009). The following nine maternal behaviors were scored as either present or absent during each of the six 30-second epochs: (1) Comfort-Verbal: making a statement or complimenting the child to help him/her feel better (e.g., “You’re being a good girl.”); (2) Comfort-Physical: offering physical affection; (3) Verbal Instruction: suggesting a cognitive or behavioral strategy for alleviating negative affect; (4) Narrating: talking to the child about what is occurring throughout the task; (5) Task Directing – Verbal: providing directions and/or suggestions for what to do in the task (e.g., I think you should tickle the dinosaur); (6) Task Directing – Physical: providing directions in a physical manner (e.g., moving the dinosaur closer to the child); (7) Quiz-Task: asking questions about the task at hand (8) Quiz/label-feeling: asking questions or making statements about how the child feels during the task; and (9) Dismissive: ignoring the child’s negative affect, making a statement indicating that the child isn’t justified in the expression of their negative affect, or making derisive/teasing comments. A code of incoherent was given if the verbalization was not heard clearly.

Coders summed the frequency count for each maternal behavior, which generated a total count of how often each child experienced each maternal behavior. Observers overlapped on 25% of cases (N=45; ICCmean=.78; ICCrange=.64–.90). The lowest intraclass correlation was for dismissive (.64), which occurred in low frequency; otherwise, all ICCs were above .70. Proportion scores were calculated to indicate how often (e.g., 3 out of 6 epochs) the mother performed each behavior.

To examine the different parenting dimensions that emerged from the data, these proportion scores were entered into a Principal Components Analysis (PCA). The results suggested a three-component solution based on eigenvalues greater than one and inspecting the scree plot (see supplement for details; Table S3 shows the component loadings). Scores on the three parenting dimensions were calculated by averaging the maternal behaviors with the highest loadings for each component. The first parenting component, High Affectionate/Oversolicitousness, explained 24.07% of the variance and was comprised of the proportion of Comfort-Verbal, Comfort-Physical, Verbal Instruction, and Quiz/Label-Feelings. The second component, Dismissiveness, explained 16.41% of the variance and included the proportion of Dismissive behavior, Quiz-Task, and Narrating. Lastly, the third component, Task-Directiveness, explained 12.11% of the variance and was comprised of the proportion of Task Directing-Physical and Task Directing-Verbal. To address the aims of the current study, we focused on the component capturing the High Affectionate/Oversolicitousness parenting style. However, in order to account for the effect of the other parenting behaviors and test the specificity of the effects of High Affectionate/Oversolicitous parenting, we included the other parenting composites in the model.

Child affect during Unpredictable Toy task.

Children’s expressed affect during the Unpredictable Toy task was coded using an observational coding scheme. Child affect was coded during each 30-second epoch, for a total of six epochs per child. During each epoch, coders rated the intensity of children’s positive, frustrated, and fearful/sad affect using a 6-point Likert scale. Thirty percent of cases (N=52) were coded by three raters to establish reliability. ICCs for positive affect, frustration, and sad/fearful affect were .79, .72, and .72, respectively. The average rating across epochs were computed with higher scores indicating greater intensity of each affect. Given our interest in BI and anxiety, we utilized the fearful/sad affect ratings. In order to control for the effects of children’s behavior during the parenting task, we included children’s level of fearful/sad affect as covariates to help isolate the effects of parenting. As a sensitivity analysis, we also controlled for the child’s level of frustration, which was not associated with parenting (r = .06), finding the same general pattern of results (Table S4).

Emotion Regulation Strategies –

ER strategies were assessed at age 5 using behavioral observations during the Disappointment Paradigm. This task was initially designed to examine display rules in young children (Cole, 1986), and later used to evaluate regulatory strategies among young children (Cole et al., 2004). During this task, a research assistant presented eight toys to the child, four of which were flawed and described as such to the child (e.g., “This is a pair of sunglasses, but they are broken and cannot be fixed.”). The remaining four toys were in good condition and described as such (e.g., “This is a bouncy ball with different colors on it.”). Children rank-ordered all eight toys on a tray. Following a separate and unrelated 15-minute task, another experimenter entered and placed the child’s lowest-ranked toy on the table, and said, “Here is your prize. Thanks for all your hard work.” This experimenter stayed in the room for one minute and repeated back to the child any statements that he/she made. Afterward, this research assistant explained to the child that he/she accidentally picked up the incorrect toy, and the child received the prize he/she initially selected as his/her top choice.

Children’s ER strategies were coded in 10-second epochs, beginning when the toy was placed on the table, for a total of 6 epochs. ER strategies were coded as one of three types: (1) Active regulation (e.g., attempting to fix the broken toy, asking the research assistant for the correct toy), (2) Passive toleration (e.g., staring at toy), and (3) Disruptive behavior (e.g., breaking or throwing the toy). The presence or absence of each strategy was coded in each epoch, and multiple strategies could be coded within one epoch. Proportion scores were created that reflected the proportion of epochs in which a particular strategy was used, thus creating three continuous scores ranging from zero to one that represented children’s use of each strategy type. The ICC for the number of active, passive, and disruptive ER strategies was .82, .87, and .79, respectively. Due to the low frequency of disruptive strategies (4.7%), this variable was dropped from further analyses. To assess children’s ER strategy use, we created a composite (i.e., average) of the strongly negatively correlated (r = −.834) proportion scores for active and passive ER strategies. This composite of active and passive ER strategies was used as the indicator for the engaged ER strategies variable, with higher scores indicating greater levels of active ER strategies and lower levels of passive ER strategies.

Socially Anxious Behavior –

In order to create a robust and comprehensive composite of socially anxious behavior as the outcome of interest, the current study utilizes a multidimensional assessment of parent and child reported symptoms of social anxiety, socially anxious behavior, and clinical diagnoses of social anxiety in late childhood and early adolescence (at ages 10 and 13 years). The measures and methods used to create this comprehensive composite are described in detail below.

Screen for Child Anxiety Related Disorders (SCARED).

At both the 10- and 13-year visits, parents and children independently completed the SCARED, a questionnaire assessment of symptoms linked to DSM-IV anxiety disorders (Muris et al., 2004). In order to assess social anxiety symptoms, items for the social phobia subscale of the SCARED were separately summed for parents and children at each age. Reliability estimates identified good internal consistency for the social phobia subscale (α10-year parent = .90; α10-year child = .78; α13-year parent = .90; α13-year child = .87).

Socially anxious behavior.

To provide direct observation of socially anxious behavior, participants completed a “Get to Know You (GTKY)” task. This task has been previous described (Bowers et al., 2020; Buzzell et al., in press). Briefly, participants were seated at a table with unfamiliar peers (one peer at age 10, two peers at age 13). The participants were left alone for two minutes, providing an opportunity to speak with one another. Participants’ behaviors were videotaped and coded offline by trained coders. The amount of time until participants made their first spontaneous utterance and the percentage of time they spoke during the two-minute period were recorded. The number of times participants shared information about themselves, and separately, the number of times they sought information from others through questions were also recorded. Further, appropriateness of conversation (e.g., flow of conversation, information seeking from peer), openness to interaction (e.g., eye contact in relation to peer, physical orientation in relation to peer), and social ease during interaction were globally rated on a scale of 1 to 5 (10-year ICCrange=.78 – .98; 13-year ICCrange= 0.89 – 0.98). Where appropriate, coded variables were reverse-scored so that higher values would relate to greater socially anxious behavior. Separate exploratory factor analyses for the variables coded at age 10 and 13 suggested that single factors best explained all variables at each time point. Therefore, all variables at each time point were Z-scored and then averaged to create composites capturing socially anxious behavior during the social interaction task at each age.

Clinical Interviews.

Semi-structured diagnostic interviews (Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia; KSADS) were completed for children and parents at the 10- and 13-year assessments. All interviews were conducted under the supervision of diagnostic experts. Final diagnoses were made by expert consensus; audiotapes for 26.6% of interviews were reviewed for reliability, yielding exceptionally high reliability for anxiety diagnoses (κ = .911). The present study examined the presence of clinically significant social anxiety, defined by clinical diagnosis and was coded as 1 = Clinical Diagnosis and 0 = No Diagnosis. Clinical diagnosis of social anxiety at the 10- and 13-years assessments was 4.3% and 6.9%, respectively.

To create a measure of socially anxious behavior that included several measures and multiple informants during late childhood and early adolescence, we created factor scores by using a confirmatory factor analysis based on Buzzell et al., 2021. In brief, the factor included 8 indicators: the observed socially anxious behavior composite from the GTKY task, child and parent reports of social anxiety from the SCARED, and clinical diagnoses of social anxiety from the 10- and 13-year time points. The residual variances for the individual indicators were allowed to co-vary across time points to account for repeated measures. Because clinical diagnoses were coded as dichotomous variables, the confirmatory factor analysis used the WLSMV estimator, wherein missing data are excluded on a pairwise basis. All the indicators significantly loaded into the anxiety factor (see supplement; Table S5). The model yielded excellent model fit (RMSEA = .00, CFI = 1.0, SRMR = .052) and factor scores were extracted for subsequent analyses, such that higher scores indicate more socially anxious behavior. Sensitivity analyses examining socially anxious behavior at 10 and 13 years separately produced the same pattern of results across both ages (see supplement; Tables S6 & S7) and showed that socially anxious behavior is highly consistent across ages (β = .884). This supports our decision to examine these ages together in one composite and is in line with a previous report from this dataset (Buzzell et al., 2021). Moreover, sensitivity analyses testing the effects using a more traditional anxiety composite of only parent and child reports of anxiety in the SCARED (Bowers et al., 2020), showed similar results (Table S8).

Analytical Strategy

Structural equation modeling with lavaan (Rosseel, 2012) in R, Version 3.6, (R Development Core Team, 2008) was used to test the study’s aims. In order to evaluate the first aim of the study, we conducted a mediation analysis using a path model. Specifically, BI was the predictor, ER strategy was the mediator, and socially anxious behavior was the outcome. In order to evaluate the second aim of the study, we conducted a moderated mediation analysis building on the previous mediation model by testing if parenting moderated the path between BI and ER strategies (Figure 1). In addition, as in previous studies with these dataset (Miller et al., 2019; Morales et al., 2019), models included the following covariates a priori: gender, maternal ethnicity, and maternal education. This was to better estimate missing patterns and because some these covariates were related with variables of interest. Gender was coded as males = 0 and females = 1. Maternal ethnicity was coded as Non-Hispanic Caucasian = 1 and Other = 0 and maternal education was coded as High school graduate = 0, College Graduate = 1, Graduate school graduate = 2, and Other = missing. Moreover, in order to isolate the effects of oversolicitous parenting and control for evocative child effects, we included as covariates in the final model, children’s level of fearful/sad affect during the Unpredictable Toy task as well as the other parenting dimensions and their interactions with BI.

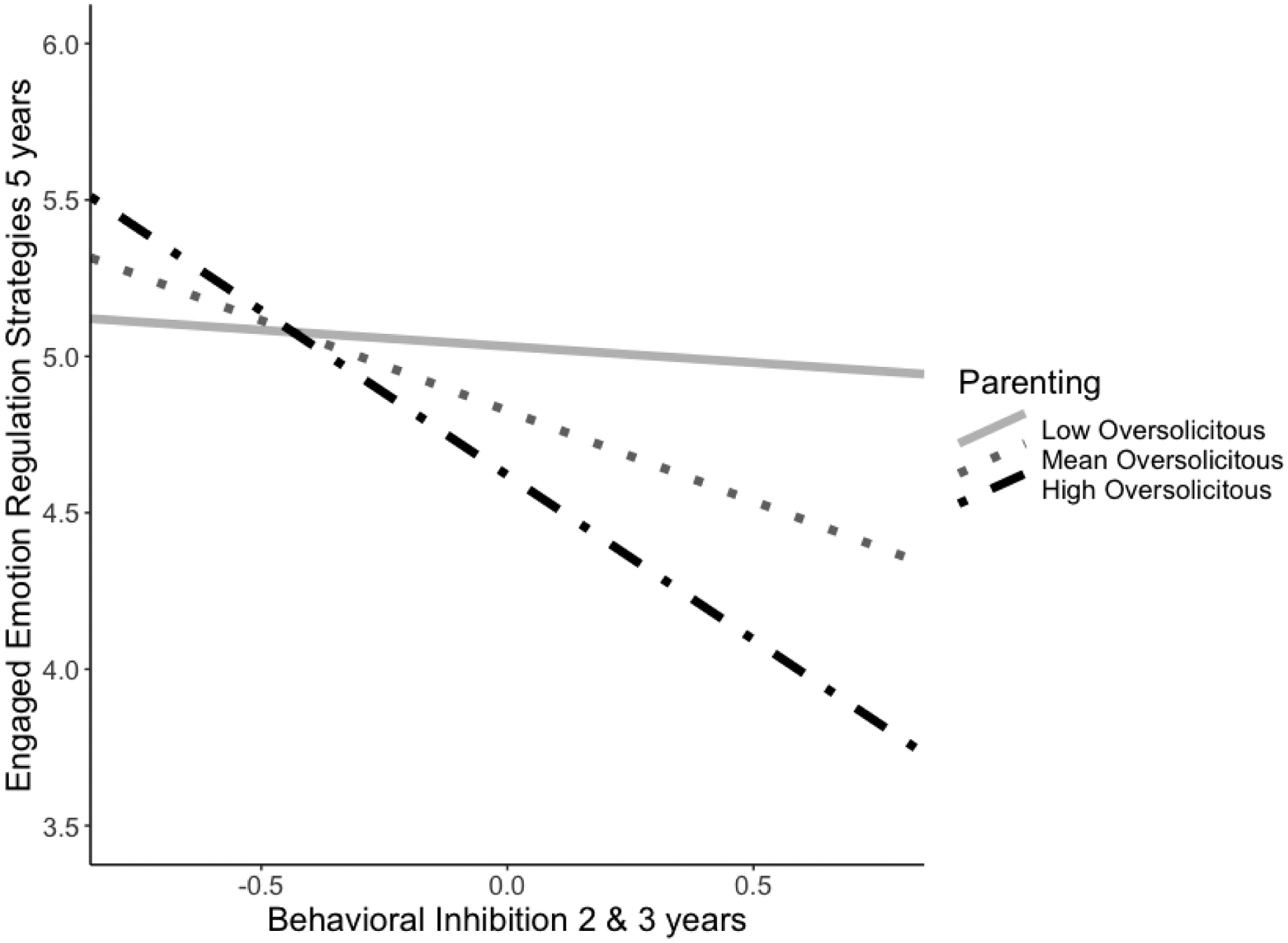

Figure 1. Interaction Between Behavioral Inhibition and Levels of Affectionate/Oversolicitous Parenting.

Note. Simple slopes for the interaction between BI at different levels of affectionate/oversolicitous parenting behaviors predicting ER strategies at 5 years. Low affectionate/oversolicitous parenting was defined as −1SD and high affectionate/oversolicitous parenting as +1SD from the mean.

Both models used full information maximum likelihood estimation (FIML) to handle missing data to reduce potential bias in the parameter estimates (Enders et al., 2014; Enders & Bandalos, 2001). This permitted the inclusion of all participants with data on one or more variables (as opposed to list-wise deletion). Moreover, due to the missing data and to correct for any departures from multivariate normality, the models were estimated using a robust maximum likelihood estimator and a scaled test chi-squared statistic (Satorra & Bentler, 2001). As a sensitivity analysis, we also analyzed our models using listwise deletion rather than FIML, finding the same pattern of results (Table S9). To evaluate mediation effects, we used both the delta method and bias corrected bootstrapping. The delta method, which tests the significance of the product of standard errors for the a and b paths, provides a conservative estimate of mediation (Sobel, 1982). Therefore, we used a bias-corrected bootstrapping procedure as our primary test (5,000 draws) because it has been shown to increase accuracy and power, especially for small and medium sample sizes (MacKinnon et al., 2004; Preacher & Hayes, 2008; Shrout & Bolger, 2002). For significant moderation effects, we tested the interaction and the indirect effect at one standard deviation above and below the mean to probe the nature of the moderated mediation effect (Preacher et al., 2007). In the moderation models, predictors were mean-centered, and the interaction term was created as the product of the centered predictors outside of the model (with missing data) and treated as a manifest variable.

2. Results

Preliminary Analyses

Descriptive statistics and correlations for all study variables are displayed in Table 1. Of note, BI at ages 2 and 3 years was negatively associated with engaged ER strategies at age 5 (r = −0.24), and significantly and positively associated with socially anxious behavior at ages 10 and 13 (r = 0.24). Child sex was significantly associated with child negative affect at age 3 (r = .16), use of engaged ER strategies (r = −0.23), and socially anxious behavior (r =.21), such that males exhibited less negative affect, more engaged ER strategies, and less socially anxious behavior.

Table 1.

Means, standard deviations, and correlations with confidence intervals

| Variable (age in years) | M | SD | N | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gender | + | 291 | ||||||||||

| 2. Maternal Ethnicity | ++ | 290 | .05 | |||||||||

| 3. Maternal Education | 1.21 | 0.72 | 273 | −.01 | .19 | |||||||

| 4. Behavioral Inhibition (2 & 3) | −0.01 | 0.77 | 268 | −.00 | −.04 | .05 | ||||||

| 5. Oversolicitous Parenting (3) | 0.28 | 0.21 | 205 | .12 | −.03 | −.13 | −.01 | |||||

| 6. Dismissive Parenting (3) | 0.74 | 0.15 | 205 | .04 | .28 | .09 | −.08 | −.15 | ||||

| 7. Task Directive Parenting (3) | 0.41 | 0.21 | 205 | −.09 | −.20 | −.18 | −.10 | .20 | −.13 | |||

| 8. Child negative (fear/sad) affect (3) | 0.49 | 0.55 | 171 | .16 | .01 | .10 | .10 | .62 | −.30 | .15 | ||

| 9. Emotion Regulation (5) | 4.65 | 1.85 | 206 | −.23 | −.00 | .05 | −.24 | −.07 | −.06 | −.01 | −.00 | |

| 10. Socially Anxious Behavior (10 & 13) | −0.03 | 1.68 | 209 | .21 | −.14 | −.19 | .24 | .08 | −.09 | .05 | .04 | −.33 |

Note. M and SD are used to represent mean and standard deviation, respectively. Bold = p < .05. + 1 = Females and 0 = Males. ++ Non-Hispanic Caucasian = 1 and Other = 0.

Mediation Analysis

To examine aim one, the associations between BI (ages 2 and 3), engaged ER strategies (age 5), and socially anxious behavior (ages 10 and 13), we tested a mediation model. Specifically, the model included BI as the predictor, engaged ER strategy as the mediator, and socially anxious behavior as the outcome. As shown in Table 2, results revealed that the significant association between BI and socially anxious behavior (c) is explained through ER strategy use during the disappointment task. The paths were significant from BI to ER strategy (a), and from ER strategy to socially anxious behavior (b). Importantly, the indirect effect of BI on socially anxious behavior through ER strategy was significant (ab), b = .136, SE = .05, p = .009, 95% Bootstrapped CI [0.050, 0.276]. The direct effect of BI on socially anxious behavior (c′) was also significant. The model explained 11.4% of the ER variance and 18.9% of the social anxiety variance.

Table 2.

Path Results for the Mediation Model

| Outcome/Predictors (path) | β | b | p | LL | UL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emotion Regulation | |||||

| Gender | −0.23 | −0.85 | 0.000 | −1.321 | −0.374 |

| Maternal Ethnicity | −0.01 | −0.03 | 0.923 | −0.581 | 0.526 |

| Maternal Education | 0.05 | 0.14 | 0.433 | −0.205 | 0.479 |

| Behavioral Inhibition (a1) | −0.24 | −0.59 | 0.000 | −0.913 | −0.264 |

| Socially Anxious Behavior | |||||

| Gender | 0.15 | 0.48 | 0.021 | 0.074 | 0.896 |

| Maternal Ethnicity | −0.10 | −0.38 | 0.106 | −0.834 | 0.081 |

| Maternal Education | −0.15 | −0.36 | 0.020 | −0.659 | −0.056 |

| Emotion Regulation (b1) | −0.26 | −0.23 | 0.001 | −0.366 | −0.096 |

| Behavioral Inhibition (c’) | 0.16 | 0.34 | 0.013 | 0.070 | 0.608 |

Note. β = standardized estimates. b = unstandardized estimates. LL = lower limit of 95% confidence interval. UL = upper limit of 95% confidence interval. Bold = p < .05. BI = Behavioral Inhibition. Gender was coded as females = 1 and males = 0. Maternal Ethnicity was coded as Non-Hispanic Caucasian = 1 and Other = 0. Maternal Education was coded as High school graduate = 0, College Graduate = 1, Graduate school graduate = 2, and Other = missing.

Moderated Mediation Analyses

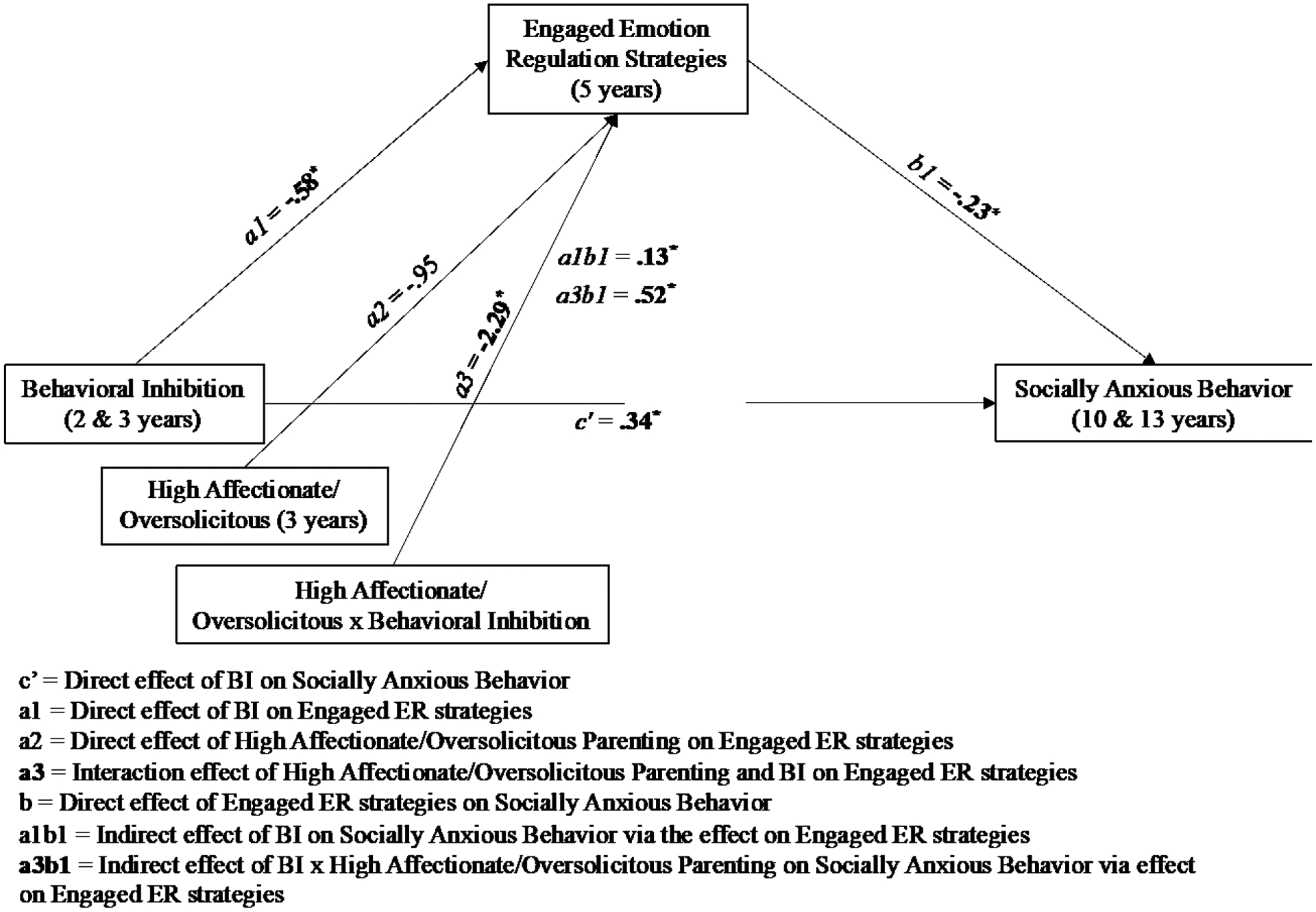

In order to examine the second aim, the impact of parenting behaviors on children’s use of ER strategies and future socially anxious behavior, we conducted a moderated mediation analysis. As predicted and shown in Table 3, results revealed the relation between BI and ER strategy was moderated by affectionate/oversolicitous parenting behaviors. As shown in Table 3 and Figure 1, BI predicted less engaged ER strategy use at high and average levels of affectionate/oversolicitous parenting behavior, b = −1.06, SE = 0.19, p < 0.001, 95% CI [−1.437, −0.679] and b = −0.58, SE = 0.16, p < 0.001, 95% CI [−0.896, −0.257], respectively. But BI did not predict ER at low levels of affectionate/oversolicitous parenting behavior, b = −0.10, SE = 0.24, p = 0.692, 95% CI [−0.564, 0.374]. In turn, more engaged ER strategies predicted less socially anxious behavior at ages 10 and 13, b = −0.23, SE = 0.07, p = 0.001, 95% CI [−0.363, −0.091]. Importantly, the indirect pathway linking BI to social anxiety via engaged ER strategies was also conditional on affectionate/oversolicitous parenting behaviors as indicated by a significant interaction indirect effect, b = 0.52, SE = 0.24, p = 0.033, 95% Bootstrapped CI [0.121, 1.186] (see Figure 2). Probing this interaction revealed that for children receiving high or average levels of affectionate/oversolicitous parenting behavior, engaged ER strategies mediated the relation between BI and socially anxious behavior, b = 0.24, SE = 0.09, p = 0.005, 95% Bootstrapped CI [0.089, 0.455] and b = 0.13, SE = 0.05, p = 0.008, 95% Bootstrapped CI [0.051, 0.268], respectively. This indirect effect was not significant at low levels of affectionate/oversolicitous parenting behavior, b = 0.02, SE = 0.05, p = 0.685, 95% Bootstrapped CI [−0.102, 0.150]. The model explained 17.4% of the ER variance and 18.7% of the social anxiety variance. Moreover, the model had good fit, χ2(7) = 3.63, p = .82; RMSEA = 0.00; CFI = 1.00; SRMR = 0.011.

Table 3.

Path Results for the Moderated Mediation Model

| Outcome/Predictors (path) | β | b | p | LL | UL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emotion Regulation | |||||

| Gender | −0.24 | −0.90 | 0.000 | −1.395 | −0.400 |

| Maternal Ethnicity | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0.818 | −0.505 | 0.639 |

| Maternal Education | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.732 | −0.299 | 0.426 |

| Child Negative (Fear/Sad) Affect | 0.09 | 0.29 | 0.372 | −0.351 | 0.939 |

| Behavioral Inhibition (a1) | −0.24 | −0.58 | 0.000 | −0.896 | −0.257 |

| Oversolicitous Parenting (a2) | −0.11 | −0.95 | 0.295 | −2.721 | 0.826 |

| BI × OP (a3) | −0.19 | −2.29 | 0.001 | −3.631 | −0.946 |

| Dismissive Parenting | −0.06 | −0.12 | 0.415 | −0.398 | 0.164 |

| Task Directive Parenting | −0.07 | −0.13 | 0.375 | −0.402 | 0.151 |

| BI × DP | −0.12 | −0.31 | 0.075 | −0.642 | 0.031 |

| BI × TDP | −0.08 | −0.17 | 0.313 | −0.499 | 0.160 |

| Socially Anxious Behavior | |||||

| Gender | 0.14 | 0.48 | 0.022 | 0.070 | 0.894 |

| Maternal Ethnicity | −0.10 | −0.38 | 0.103 | −0.837 | 0.077 |

| Maternal Education | −0.15 | −0.36 | 0.019 | −0.661 | −0.058 |

| Emotion Regulation (b1) | −0.25 | −0.23 | 0.001 | −0.363 | −0.091 |

| Behavioral Inhibition (c’) | 0.16 | 0.34 | 0.014 | 0.068 | 0.609 |

Note. β = standardized estimates. b = unstandardized estimates. LL = lower limit of 95% confidence interval. UL = upper limit of 95% confidence interval. Bold = p < .05. BI = Behavioral Inhibition. OP = Overprotective Parenting. DP = Dismissive Parenting. TDP = Task Directive Parenting. Gender was coded as females = 1 and males = 0. Maternal Ethnicity was coded as Non-Hispanic Caucasian = 1 and Other = 0. Maternal Education was coded as High school graduate = 0, College Graduate = 1, Graduate school graduate = 2, and Other = missing.

Figure 2. Unstandardized Results of Regression Analyses for the Moderated Mediation Analysis.

Note. The covariates gender, maternal ethnicity, maternal education, child negative affect, and other parenting dimensions are not shown in the figure but are shown in Table 3.

Finally, in addition to the sensitivity analyses described above, we also examined if results changed while controlling for previous anxiety levels at age 5 by using parent reports in the Anxiety Scale of the Child Behavior Checklist (Achenbach, 1991), finding that results remained the same (Table S10). Taken together, the sensitivity analyses suggest that our results are robust to several methodological decisions such as the specific measure of BI (observed vs. parent reports) and anxiety (latent factor vs. traditional average and one age of assessment vs. across assessments), handling of missing data (listwise deletion vs. FIML) and controlling for previous levels of anxiety.

3. Discussion

This study examined the role of ER strategies in the relation between early fearful temperament (BI) and socially anxious behavior. We extend the findings of previous studies, highlighting the important role that ER strategies play in the relation between early displays of BI and future socially anxious behavior. Consistent with our hypothesis, we found that children who exhibited high BI in early childhood displayed more socially anxious behavior in late childhood and early adolescence, and this association was mediated via ER strategies used during the disappointment task at age 5. The indirect effect of BI on socially anxious behavior through ER strategies was significant, demonstrating that children who were high in BI, employed less engaged ER strategies during the disappointment task, which in turn predicted more socially anxious behavior in late childhood and early adolescence. Moreover, parenting behavior proved to be an important moderator in the pathway linking early BI and ER strategies to social anxiety outcomes. In line with our hypothesis, children exhibiting high levels of BI at 2 and 3 years and who received more highly affectionate/oversolicitous behavior from their mothers during a fear-eliciting task at 3 years displayed less engaged ER strategies at age 5, which in turn, led to increased socially anxious behavior at ages 10 and 13 years.

The current study extends previous findings, highlighting ER strategy use as one developmental mechanism linking early BI to social anxiety. Further, we elucidate the moderating role of oversolicitous/highly affectionate parenting in the relation between BI and ER strategies, which further impacts the developmental pathway linking BI to socially anxious behavior. The present study had several methodological strengths, in particular, the longitudinal design and the use of observational measures to assess specific behaviors relevant to the developmental pathway, including BI, ER strategies, parenting behaviors, and social anxiety. Further, we examined the longitudinal relations among these constructs beginning in early childhood (i.e., 2 and 3 years) before symptoms of social anxiety are typically present. However, the current study is not without limitations.

Features of this work limit the conclusions we can draw about the developmental pathway linking early BI to socially anxious behavior. First, we were unable to adjust for prior or concurrent levels of BI, parenting, ER strategy use, or social anxiety. This limitation is largely due to the types of measures and methods used in this study, which change considerably across development. For example, assessment of emotion regulation using the disappointment task is most often used with children between 4 to 6 years (Carlson & Wang, 2007; Cole et al., 1994; Feng et al., 2008; Stifter et al., 2011). More rigorous longitudinal designs that measure each variable at multiple time points in a uniform manner are required to provide stronger evidence of causal pathways among these variables. Additionally, as is common in longitudinal studies, there were missing data across assessment periods. In our longitudinal cohort, children with complete data on several measures were more likely to have non-Hispanic, Caucasian mothers. Although we utilized statistical methods that maximize the available data and reduce the potential biases associated with missing data, missing data should be considered a limitation of the current study. Moreover, the current sample was mostly Caucasian, highly educated, and demonstrated low rates of clinical diagnosis for social anxiety; therefore, the generalizability of the study results are limited by each of these factors. Also, it should be noted that several effects (e.g., the indirect effects) are not large; however, the sensitivity analyses conducted suggest that although the results may not have a very large effect, they are robust to several methodological decisions, increasing our confidence in the findings. Still, future replication of these findings is encouraged.

Future studies should also examine characteristics of the mothers and the children that may lead to the observed differences in parenting. In the current study, we failed to collect data on parental characteristics (e.g., psychopathology and temperament). Previous studies show that the association between BI and social anxiety disorder may be particularly strong for children whose parents have anxiety disorders and/or a history of BI (Hirshfeld-Becker et al., 2007; Stumper et al., 2017). It is possible that parental characteristics contribute to the continuity of inhibited behavior and anxiety risk and the intergenerational transmission of anxiety. Future research should incorporate this data to disentangle whether socially anxious behavior is caused by parental characteristics or child characteristics, or both. In addition, it should be noted that this study was conducted with a selected sample of children on the basis of early temperament, and as such, further work is needed to determine if our findings generalize to an unselected sample. Lastly, the coding of parenting behavior during the fear-eliciting task was done in 30-second epochs, which limited our ability to examine unique transactional patterns between the parent and the child. Moment-to-moment coding during the fear-eliciting task would provide an in-depth analysis of the dyadic interactions between the parent and child and help to elucidate how these parent-child transactions may produce the observed behavioral outcomes. Such an in-depth coding strategy would help clarify how parenting behavior and child temperament interact to influence children’s ER strategy use and the development of socially anxious behavior.

Despite these limitations, our results suggest that the ability to employ engaged ER strategies may be one of the developmental pathways by which early temperamental risk leads to more severe socially anxious behavior. These findings are in line with previous research, which shows that children’s diminished use of engaged ER strategies links shy or behaviorally inhibited behavior to asocial behavior and poor social competence (Hipson et al., 2019; Penela et al., 2015). Our results build on the existing literature, demonstrating that for children exhibiting high BI, ER strategy selection and implementation is important not only for future social competence, but also for future socially anxious behavior more broadly. Children exhibiting consistent BI from an early age may become overly aroused during situations that evoke emotions such as disappointment or sadness, and this, in turn, may lead to inappropriate strategy selection (e.g., BI children resorting to more passive ER strategies) and worse internalizing problems across development. Moreover, the use of passive ER strategies (e.g., passive tolerance, avoidance) may mitigate discomfort in the short-term; however, reliance on such maladaptive ER strategies limits the opportunity to increase tolerance to the seemingly intolerable situation/emotion, fostering increased anxiety over time (Aldao et al., 2010; Jazaieri et al., 2015).

Furthermore, we show that parenting behavior has an important moderating impact on the developmental pathway linking early BI to future socially anxious behavior. Interestingly, none of the observed parenting behaviors exhibited a direct main effect on engaged ER strategies, but there was a significant interaction indicating that the link between BI to social anxiety via engaged ER strategies was conditional on affectionate/oversolicitous parenting behaviors. The presence of the interaction in the absence of a main effect highlights the unique dynamic interaction between child characteristics and parenting behaviors in shaping a child’s ER strategy repertoire. Parents who engage in such highly affectionate and oversolicitous behaviors may do so as a way of shielding their especially fearful children from potential fear/anxiety inducing scenarios, even when it may be considered inappropriate or insensitive to do so. In this way, parents may be inadvertently preventing their children from developing and engaging in necessary and self-initiated ER strategies that may protect against future anxiety. This form of oversolicitous/overprotective parenting behavior is closely related to a style of parenting referred to as parental accommodation, a posited contributor to the development and maintenance of youth anxiety disorders (Kagan et al., 2016). Parental accommodation refers to modifications in parenting behavior meant to prevent or mitigate their child’s distress when they encounter a fear-invoking situation or stimulus (Thompson-Hollands et al., 2014). Examples of such modifications in parenting behavior include, but are not limited to, enabling children’s anxiety-related avoidance, providing excessive support and reassurance, and modifying family routines (Kagan et al., 2016; Thompson-Hollands et al., 2014). Parental accommodation, which is closely related to oversolicitous/overprotective parenting styles, can reduce children’s distress in the short term, but tends to contribute to the persistence of anxiety-symptoms through facilitation of future avoidance behaviors (Ginsburg et al., 2004; Thompson-Hollands et al., 2014).

The present findings have many implications for how intervention strategies may help to prevent negative outcomes, such as social anxiety, by encouraging especially fearful children to practice effective engaged ER strategies. Interventions that incorporate the development of important social skills and the practice of constructive strategies for coping with distress have proven to be initially promising in reducing socially wary behaviors and promoting social competence in children who are high on BI (Chronis-Tuscano et al., 2015; Coplan et al., 2010). Moreover, one study found that low negative emotionality and strong physiological regulation (i.e., high levels of baseline RSA) buffered highly inhibited children against later social reticence with an unfamiliar peer (Smith et al., 2019). Thus, children showing higher levels of BI may benefit significantly from programs that promote engaged ER strategy use and the practice of active coping during emotionally salient social or non-social situations. In addition, family-based interventions aimed at treating childhood anxiety disorders have placed emphasis on issues related to parental accommodation and show initial success in improving child outcomes (Chronis-Tuscano et al., 2015; Comer et al., 2012; Lebowitz et al., 2014, 2020). Implementation of similar interventions that focus on reducing oversolicitous/highly affectionate behaviors in parents of young BI children might also help to mitigate or prevent the onset of social anxiety symptoms and behavior later in life.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the families who participated in the study, as well as the students and staff who assisted in data collection. This research was supported the National Institutes of Health MH093349 and HD017899 to Dr. Nathan Fox.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Achenbach TM, & Rescorla L (2001). Manual for the ASEBA school-age forms and profiles: An integrated system of multi-informant assessment. University of Vermont Department of Psychiatry. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM (1991). Child Behavior Checklist 4–18. Department of Psychiatry, University of Vermont. [Google Scholar]

- Aldao A, Nolen-Hoeksema S, & Schweizer S (2010). Emotion-regulation strategies across psychopathology: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 30(2), 217–237. 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowers ME, Reider LB, Morales S, Buzzell GA, Miller N, Troller-Renfree SV, Pine DS, Henderson HA, & Fox NA (2020). Differences in Parent and Child Report on the Screen for Child Anxiety-Related Emotional Disorders (SCARED): Implications for Investigations of Social Anxiety in Adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 48(4), 561–571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buzzell GA, Morales S, Bowers ME, Troller-Renfree SV, Chronis-Tuscano A, Pine DS, Henderson HA, & Fox NA (2021). Inhibitory control and set shifting describe different pathways from behavioral inhibition to socially anxious behavior. Developmental Science, 24(1), e13040. 10.1111/desc.13040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calkins SD, Fox NA, & Marshall TR (1996). Behavioral and Physiological Antecedents of Inhibited and Uninhibited Behavior. Child Development, 67(2), 523–540. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1996.tb01749.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calkins SD, Gill KL, Johnson MC, & Smith CL (1999). Emotional Reactivity and Emotional Regulation Strategies as Predictors of Social Behavior with Peers During Toddlerhood. Social Development, 8(3), 310–334. 10.1111/1467-9507.00098 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson SM, & Wang TS (2007). Inhibitory control and emotion regulation in preschool children. The Development of Self-Regulation: Toward the Integration of Cognition and Emotion, 22(4), 489–510. 10.1016/j.cogdev.2007.08.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chronis-Tuscano A, Degnan KA, Pine DS, Perez-Edgar K, Henderson HA, Diaz Y, Raggi VL, & Fox NA (2009). Stable Early Maternal Report of Behavioral Inhibition Predicts Lifetime Social Anxiety Disorder in Adolescence. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 48(9), 928–935. 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181ae09df [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chronis-Tuscano A, Rubin KH, O’Brien KA, Coplan RJ, Thomas SR, Dougherty LR, Cheah CSL, Watts K, Heverly-Fitt S, Huggins SL, Menzer M, Begle AS, & Wimsatt M (2015). Preliminary evaluation of a multimodal early intervention program for behaviorally inhibited preschoolers. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 83(3), 534–540. 10.1037/a0039043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clauss JA, & Blackford JU (2012). Behavioral inhibition and risk for developing social anxiety disorder: A meta-analytic study. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 51(10), 1066–1075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole PM (1986). Children’s Spontaneous Control of Facial Expression. Child Development, 57(6), 1309–1321. JSTOR. 10.2307/1130411 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cole PM, Martin SE, & Dennis TA (2004). Emotion Regulation as a Scientific Construct: Methodological Challenges and Directions for Child Development Research. Child Development, 75(2), 317–333. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00673.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole PM, Zahn-Waxler C, & Smith KD (1994). Expressive control during a disappointment: Variations related to preschoolers’ behavior problems. Developmental Psychology, 30(6), 835. [Google Scholar]

- Comer JS, Puliafico AC, Aschenbrand SG, McKnight K, Robin JA, Goldfine ME, & Albano AM (2012). A pilot feasibility evaluation of the CALM Program for anxiety disorders in early childhood. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 26(1), 40–49. 10.1016/j.janxdis.2011.08.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compas BE, Jaser SS, Bettis AH, Watson KH, Gruhn MA, Dunbar JP, Williams E, & Thigpen JC (2017). Coping, emotion regulation, and psychopathology in childhood and adolescence: A meta-analysis and narrative review. Psychological Bulletin, 143(9), 939–991. 10.1037/bul0000110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coplan RJ, Schneider BH, Matheson A, & Graham A (2010). ‘Play skills’ for shy children: Development of a Social Skills Facilitated Play early intervention program for extremely inhibited preschoolers. Infant and Child Development, 19(3), 223–237. 10.1002/icd.668 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Degnan KA, Almas AN, Henderson HA, Hane AA, Walker OL, & Fox NA (2014). Longitudinal trajectories of social reticence with unfamiliar peers across early childhood. Developmental Psychology, 50(10), 2311–2323. 10.1037/a0037751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degnan K, & Fox N (2007). Behavioral inhibition and anxiety disorders: Multiple levels of a resilience process. Development and Psychopathology, 19, 729–746. 10.1017/S0954579407000363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Cumberland A, & Spinrad TL (1998). Parental socialization of emotion. Psychological Inquiry, 9(4), 241–273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enders CK, & Bandalos DL (2001). The Relative Performance of Full Information Maximum Likelihood Estimation for Missing Data in Structural Equation Models. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 8(3), 430–457. 10.1207/S15328007SEM0803_5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Enders CK, Baraldi AN, & Cham H (2014). Estimating interaction effects with incomplete predictor variables. Psychological Methods, 19(1), 39–55. 10.1037/a0035314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng X, Shaw DS, Kovacs M, Lane T, O’Rourke FE, & Alarcon JH (2008). Emotion regulation in preschoolers: The roles of behavioral inhibition, maternal affective behavior, and maternal depression. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 49(2), 132–141. 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01828.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng X, Shaw DS, & Moilanen KL (2011). Parental Negative Control Moderates the Shyness–Emotion Regulation Pathway to School-Age Internalizing Symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 39(3), 425–436. 10.1007/s10802-010-9469-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginsburg GS, Siqueland L, Masia-Warner C, & Hedtke KA (2004). Anxiety disorders in children: Family matters. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 11(1), 28–43. 10.1016/S1077-7229(04)80005-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goldin PR, Lee I, Ziv M, Jazaieri H, Heimberg RG, & Gross JJ (2014). Trajectories of change in emotion regulation and social anxiety during cognitive-behavioral therapy for social anxiety disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 56, 7–15. 10.1016/j.brat.2014.02.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldsmith HH (1996). Studying Temperament via Construction of the Toddler Behavior Assessment Questionnaire. Child Development, 67(1), 218–235. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1996.tb01730.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottman JM, Katz LF, & Hooven C (1996). Parental meta-emotion philosophy and the emotional life of families: Theoretical models and preliminary data. Journal of Family Psychology, 10(3), 243–268. 10.1037/0893-3200.10.3.243 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hane AA, Fox NA, Henderson HA, & Marshall PJ (2008). Behavioral reactivity and approach-withdrawal bias in infancy. Developmental Psychology, 44(5), 1491–1496. 10.1037/a0012855 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hipson WE, Coplan RJ, & Séguin DG (2019). Active emotion regulation mediates links between shyness and social adjustment in preschool. Social Development, 28(4), 893–907. 10.1111/sode.12372 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hirshfeld-Becker DR, Biederman J, Henin A, Faraone SV, Davis S, Harrington K, & Rosenbaum JF (2007). Behavioral Inhibition in Preschool Children At Risk Is a Specific Predictor of Middle Childhood Social Anxiety: A Five-Year Follow-up. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics, 28(3), 225–233. 10.1097/01.DBP.0000268559.34463.d0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jazaieri H, Morrison AS, Goldin PR, & Gross JJ (2015). The Role of Emotion and Emotion Regulation in Social Anxiety Disorder. Current Psychiatry Reports, 17(1), 531. 10.1007/s11920-014-0531-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagan ER, Peterman JS, Carper MM, & Kendall PC (2016). Accommodation and Treatment of Anxious Youth. Depression and Anxiety, 33(9), 840–847. 10.1002/da.22520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagan J, Reznick JS, Clarke C, Snidman N, & Garcia-Coll C (1984a). Behavioral inhibition to the unfamiliar. Child Development, 2212–2225. [Google Scholar]

- Kagan J, Reznick JS, Clarke C, Snidman N, & Garcia-Coll C (1984b). Behavioral Inhibition to the Unfamiliar. Child Development, 55(6), 2212–2225. JSTOR. 10.2307/1129793 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kochanska G (1995). Children’s Temperament, Mothers’ Discipline, and Security of Attachment: Multiple Pathways to Emerging Internalization. Child Development, 66(3), 597. 10.2307/1131937 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kopp CB (1982). Antecedents of self-regulation: A developmental perspective. Developmental Psychology, 18(2), 199–214. 10.1037/0012-1649.18.2.199 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kopp CB (1989). Regulation of distress and negative emotions: A developmental view. Developmental Psychology, 25(3), 343–354. APA PsycArticles. 10.1037/0012-1649.25.3.343 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lebowitz ER, Marin C, Martino A, Shimshoni Y, & Silverman WK (2020). Parent-Based Treatment as Efficacious as Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Childhood Anxiety: A Randomized Noninferiority Study of Supportive Parenting for Anxious Childhood Emotions. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 59(3), 362–372. 10.1016/j.jaac.2019.02.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebowitz ER, Omer H, Hermes H, & Scahill L (2014). Parent Training for Childhood Anxiety Disorders: The SPACE Program. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 21(4), 456–469. 10.1016/j.cbpra.2013.10.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis-Morrarty E, Degnan KA, Chronis-Tuscano A, Rubin KH, Cheah CSL, Pine DS, Henderon HA, & Fox NA (2012). Maternal Over-Control Moderates the Association Between Early Childhood Behavioral Inhibition and Adolescent Social Anxiety Symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 40(8), 1363–1373. 10.1007/s10802-012-9663-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, & Williams J (2004). Confidence Limits for the Indirect Effect: Distribution of the Product and Resampling Methods. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 39(1), 99–128. 10.1207/s15327906mbr3901_4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller NV, Hane AA, Degnan KA, Fox NA, & Chronis-Tuscano A (2019). Investigation of a developmental pathway from infant anger reactivity to childhood inhibitory control and ADHD symptoms: Interactive effects of early maternal caregiving. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 60(7), 762–772. 10.1111/jcpp.13047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morales S, & Fox NA (2019). A Neuroscience Perspective on Emotional Development. In LoBue V, Pérez-Edgar K, & Buss KA (Eds.), Handbook of Emotional Development (pp. 57–81). Springer International Publishing. 10.1007/978-3-030-17332-6_4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Morales S, Miller NV, Troller-Renfree SV, White LK, Degnan KA, Henderson HA, & Fox NA (2019). Attention bias to reward predicts behavioral problems and moderates early risk to externalizing and attention problems. Development and Psychopathology, 1–13. 10.1017/S0954579419000166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris AS, Silk JS, Morris MDS, Steinberg L, Aucoin KJ, & Keyes AW (2011). The influence of mother–child emotion regulation strategies on children’s expression of anger and sadness. Developmental Psychology, 47(1), 213–225. 10.1037/a0021021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris AS, Silk JS, Steinberg L, Myers SS, & Robinson LR (2007). The Role of the Family Context in the Development of Emotion Regulation. Social Development, 16(2), 361–388. 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2007.00389.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muris P, Dreessen L, Bögels S, Weckx M, & van Melick M (2004). A questionnaire for screening a broad range of DSM-defined anxiety disorder symptoms in clinically referred children and adolescents. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 45(4), 813–820. 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00274.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olino TM, Guerra-Guzman K, Hayden EP, & Klein DN (2020). Evaluating maternal psychopathology biases in reports of child temperament: An investigation of measurement invariance. Psychological Assessment, 32(11), 1037–1046. APA PsycArticles. 10.1037/pas0000945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penela EC (2009). Maternal Socialization of Emotion Regulation: Promoting Social Engagement Among Inhibited Toddlers.

- Penela EC, Walker OL, Degnan KA, Fox NA, & Henderson HA (2015). Early Behavioral Inhibition and Emotion Regulation: Pathways Toward Social Competence in Middle Childhood. Child Development, 86(4), 1227–1240. 10.1111/cdev.12384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Edgar K, & Fox NA (2005). Temperament and Anxiety Disorders. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 14(4), 681–706. 10.1016/j.chc.2005.05.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, & Hayes AF (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40(3), 879–891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Rucker DD, & Hayes AF (2007). Addressing Moderated Mediation Hypotheses: Theory, Methods, and Prescriptions. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 42(1), 185–227. 10.1080/00273170701341316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Development Core Team. (2008). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. http://www.R-project.org.

- Root AE, Byrne R, & Watson SM (2015). The regulation of fear: The contribution of inhibition and emotion socialisation. Early Child Development and Care, 185(4), 647–657. 10.1080/03004430.2014.946503 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rosseel Y (2012). Lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling and more. Version 0.5–12 (BETA). Journal of Statistical Software, 48(2), 1–36. 10.18637/jss.v048.i02 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin KH, & Burgess KB (2002). Parents of aggressive and withdrawn children. In Handbook of parenting: Children and parenting, Vol. 1, 2nd ed. (pp. 383–418). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin KH, Burgess KB, & Hastings PD (2002). Stability and Social–Behavioral Consequences of Toddlers’ Inhibited Temperament and Parenting Behaviors. Child Development, 73(2), 483–495. 10.1111/1467-8624.00419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin KH, Hastings PD, Stewart SL, Henderson HA, & Chen X (1997). The Consistency and Concomitants of Inhibition: Some of the Children, All of the Time. Child Development, 68(3), 467–483. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1997.tb01952.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sameroff AJ, & Mackenzie MJ (2003). Research strategies for capturing transactional models of development: The limits of the possible. Development and Psychopathology, 15(3), 613–640. Cambridge Core. 10.1017/S0954579403000312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandstrom A, Uher R, & Pavlova B (2020). Prospective Association between Childhood Behavioral Inhibition and Anxiety: A Meta-Analysis. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 48(1), 57–66. 10.1007/s10802-019-00588-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satorra A, & Bentler PM (2001). A scaled difference chi-square test statistic for moment structure analysis. Psychometrika, 66(4), 507–514. 10.1007/BF02296192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider RL, Arch JJ, Landy LN, & Hankin BL (2018). The Longitudinal Effect of Emotion Regulation Strategies on Anxiety Levels in Children and Adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 47(6), 978–991. 10.1080/15374416.2016.1157757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrout PE, & Bolger N (2002). Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods, 7(4), 422. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith KA, Hastings PD, Henderson HA, & Rubin KH (2019). Multidimensional Emotion Regulation Moderates the Relation Between Behavioral Inhibition at Age 2 and Social Reticence with Unfamiliar Peers at Age 4. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 47(7), 1239–1251. 10.1007/s10802-018-00509-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobel ME (1982). Asymptotic Confidence Intervals for Indirect Effects in Structural Equation Models. Sociological Methodology, 13, 290–312. JSTOR. 10.2307/270723 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stifter CA, Dollar JM, & Cipriano EA (2011). Temperament and emotion regulation: The role of autonomic nervous system reactivity. Developmental Psychobiology, 53(3), 266–279. 10.1002/dev.20519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stumper A, Danzig AP, Dyson MW, Olino TM, Carlson GA, & Klein DN (2017). Parents’ behavioral inhibition moderates association of preschoolers’ BI with risk for age 9 anxiety disorders. Journal of Affective Disorders, 210, 35–42. 10.1016/j.jad.2016.12.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson-Hollands J, Kerns CE, Pincus DB, & Comer JS (2014a). Parental accommodation of child anxiety and related symptoms: Range, impact, and correlates. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 28(8), 765–773. 10.1016/j.janxdis.2014.09.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson-Hollands J, Kerns CE, Pincus DB, & Comer JS (2014b). Parental accommodation of child anxiety and related symptoms: Range, impact, and correlates. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 28(8), 765–773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troller-Renfree SV, Buzzell GA, Bowers ME, Salo VC, Forman-Alberti A, Smith E, Papp LJ, McDermott JM, Pine DS, Henderson HA, & Fox NA (2019). Development of inhibitory control during childhood and its relations to early temperament and later social anxiety: Unique insights provided by latent growth modeling and signal detection theory. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 60(6), 622–629. 10.1111/jcpp.13025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troller-Renfree SV, Buzzell GA, Pine DS, Henderson HA, & Fox NA (2019). Consequences of Not Planning Ahead: Reduced Proactive Control Moderates Longitudinal Relations Between Behavioral Inhibition and Anxiety. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 58(8), 768–775.e1. 10.1016/j.jaac.2018.06.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]