Abstract

Objectives

In KSA, numerous studies are conducted to measure the prevalence of dental caries. However, the prevalence of dental caries varies in KSA. This systematic review aims to improve the understanding of the prevalence of dental caries among adults and children residing in KSA.

Methods

Online databases of MEDLINE, EMBASE, and the Cochrane Library were searched. The Saudi Dental Journal was hand-searched. Study selection and data extraction were conducted in duplicate. The studies on dental caries in the Saudi population were included. The Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) was used to assess the quality of the selected studies. Finally, a narrative synthesis was conducted.

Results

Forty-nine cross-sectional studies were identified. Areas of weakness in study design/conduct were low response rates, reliable outcome measurement, and identification and handling of confounding factors. Statistical pooling of data was not appropriate due to substantial heterogeneity, also in part to a variation in geographical location and the target population. Twenty-nine studies presented data for primary dentition. The proportion of dental caries among primary teeth ranged from 0.21 to 1.00. Eighteen studies presented data for permanent dentition. The proportion of dental caries across permanent teeth ranged from 0.05 to 0.99.

Conclusions

In general, the methodological quality of the included studies was poor. Dental caries proportion level ranged from 0.05 to 0.99 in permanent teeth, and 0.21 to 1.00 across primary teeth. The available data does not provide a complete assessment of dental caries across KSA. Existing studies are limited in terms of the populations studied for dental caries.

Keywords: Dental caries, Permanent teeth, Prevalence, Primary dentition, KSA

الملخص

أهداف البحث

هنالك العديد من الدراسات عن مستوى انتشار تسوس الأسنان في المملكة العربية السعودية، ولكن هذه النسب متفاوتة. ولذلك فإن هدف هذه المراجعة المنهجية هو تقييم مدى نسبة انتشار تسوس الأسنان بشكل أكثر دقة لدى البالغين والأطفال في المملكة العربية السعودية

طرق البحث

تم البحث في قواعد البيانات على الإنترنت ومنها مكتبة "الكوكرين" و"مدالين" و"امبيز". بالإضافة إلى البحث اليدوي في مجلة طب الأسنان السعودية. وتم ضم الدراسات لهذه الدراسة إذا تم إجراؤها في المملكة العربية السعودية على أي مجموعة سكانية (البالغين والأطفال)، وجمعت خلالها بيانات تسوس الأسنان. واستخدم مقياس نيوكاسل-أوتاوا لتقييم جودة الدراسات.

النتائج

ضمت هذه الدراسة ٤٩ دراسة مقطعية. لكن أغلبها كان ضعيفا ومجالات الضعف كانت في تصميم الدراسات ومعدلات الاستجابة المنخفضة، وقياس النتائج الموثوق بها، وتحديد ومعالجة العوامل المربكة. لم يكن التجميع الإحصائي للبيانات مناسبا بسبب عدم التجانس الكبير، ويرجع ذلك جزئيا إلى التباين في الموقع الجغرافي والسكاني للمستهدفين في تلك الدراسات. قدمت ٢٩ دراسة بيانات عن الأسنان اللبنية. وتراوحت نسبة تسوس الأسنان بين الأسنان اللبنية من ٠.٢١ إلى١. بينما قدمت ١٨ دراسة بيانات عن الأسنان الدائمة. تراوحت نسبة تسوس الأسنان بين الأسنان الدائمة من٠.٠٥ إلى ٠.٩٩.

الاستنتاجات

جودة منهجية الدراسات المتضمنة في هذا البحث ضعيفة بشكل عام. بينما تراوحت نسبة تسوس الأسنان من٠.٠٥ إلى ٠.٩٩ في الأسنان الدائمة، وفي الأسنان اللبنية تراوحت نسبه التسوس من ٠.٢١إلى ١. لا تقدم البيانات المتوفرة حاليا تقييما كاملا لتسوس الأسنان في جميع أنحاء المملكة العربية السعودية. الدراسات الحالية محدودة من حيث السكان المشمولين.

Introduction

Dental caries is one of the most common diseases in the world, making Dental caries a public health problem. A World Health Organization (2012) report on oral health stated that 60%–80% of children worldwide suffer from dental caries, and almost 100% of adults have them.1 In KSA, several studies have been conducted to measure the prevalence of dental caries; most of them concluded that there is a high prevalence of caries among children and adults. Some of the studies were systematic reviews; for example, Al Agili et al. (2013) conducted a systematic review to measure the prevalence of dental caries in KSA between 1988 and 2010.2 They concluded that 70% of children in primary schools had caries of their permanent dentition, while 80% of them had dental caries cavity in their primary dentition. Another review concluded that the amount of dental caries in permanent dentition is high, with a mean DMFT of 3.34; they also found that mean DMFT in primary dentition is 5.38.3 Similarly, Al-Ansari et al. (2014) found that the mean DMFT in primary dentition is 7.34, while the mean DMFT in permanent dentition for adults is 7.35.4 Other studies across KSA have reported different amounts of dental caries in different areas.5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 A systematic review was conducted to identify all relevant reports and risk factors due to the wide variation in reported dental caries prevalence across KSA. Each of these reports was critically appraised. This review will help to improve the understanding of caries prevalence in KSA. Furthermore, this study will attempt to identify reasons behind this variation of outcomes of studies on the prevalence of dental caries in KSA. This will be supported by an assessment of the risk of bias of identified studies to determine if methodological factors might have impacted the findings.DED

Materials and Methods

The search strategy was designed to be as comprehensive as possible and followed the PRISMA statement. Three databases were used to identify articles published from 1999 to 2019: MEDLINE via OVID, EMBASE via OVID, and the Cochrane Library. Hand searching of the Saudi Dental Journal was also undertaken from 1999 to 2019. A mix of free-text and MeSH terms was utilised for both key concepts: dental caries and KSA. Given that the systematic review encompassed all study designs suitable for assessing caries prevalence, no study design filter was applied to the search. There was no restriction regarding the geographical coverage of the study (i.e., local community setting, town, city, province, or country-wide).

Inclusion criteria

Studies had to measure or report the dental caries experience in any area of KSA, using a valid measurement tool (for example DMFT, DMFS; ICDAS; proportion caries-free). Included studies could be conducted on adults and/or children as primary studies. They could also focus on specific demographics, such as employment status, systemic disease, or age. Studies had to be published after 1999 when the first national survey study was published.

Exclusion criteria

Studies were excluded if they measured the incidence of other oral conditions and did not consider dental caries; were not conducted in KSA; were published in a language other than English or Arabic; were not primary studies; were published before 1999.

Identified studies were collected and checked for duplication in Endnote X9. A visual double-check was conducted to identify any duplication that could have been missed. Titles and abstracts of all the remaining articles were read to check for relevance according to the inclusion criteria. Irrelevant articles were excluded at this stage.

Selection of studies

Three reviewers (FA, LOM, and AMG) independently reviewed all potential studies. Full copies of all potentially relevant articles were retrieved and reviewed until a final agreement was reached regarding inclusion.

Data extraction

Once the included studies had been identified, relevant data from those papers were extracted and transferred from the paper source to a pre-specified data table (Table 3).

Table 3.

Summary of study characteristics and outcome measures.

| Study name | Location | Age | Gender | % Caries | % Dental Free | Caries | Caries prevalence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bhayat and Ahmad (2011) | Almadinah Almunawwarah | 12 | Male | (57.2%) | (42.8%) | Overall: DMFT (1.53) (SD:1.88) Private school: DMFT (1.28) (SD:1.55) Public school: DMFT (1.81) (SD:2.15) |

D = 1.30 (SD: 1.82) Private School: D= (0.98) (SD:1.47) Public School: D=(1.65) (SD: 2.10) |

| AL Agili and Alaki (2013) | Jeddah | 9 year (880) 14 year (775) |

Male (875) Female (780) |

Age 9 (91.58%) Age 14 (73.42%). |

Overall: (16.87%) Age (9): (8.42%) Age (14): (26.58%) |

Overall: (83.13%) Age: (9) (91.58%) Age: (14) (73.42%) |

Primary teeth: (63%) Permanent teeth: (56.7%) Age 9: untreated decays: (81%) Age 14: untreated decays: (59%) |

| Al Agili and Park 2013 | Jeddah | 13 to 20 years old | Male (270) | 56% | 44% | DMFT (2.1) (SD: 2.77) | 80% of DMFT is decays |

| Al Akli et al. (2013) | Jeddah | 5_13 Years | Male (35) Female (25) |

Not record | Not record | dmft:(8.96) With asthma dmft: (8.03) Without asthma DMFT: (2.16) With asthma DMFT: (1.96) Without asthma |

Not recorded |

| Alkarimi et al., 2014 | Jeddah | 6 _ 8 years | Male (175) Female (242) |

Primary teeth (87.1%) Permanent teeth (4.8%) |

Primary teeth 12. % Permanent teeth 95.2% |

dmft: (5.7) (SD: 4.2) | (d)= (5.1) (SD:4.1) It is (89.5%) of dmft value |

| AL Amoudi et al. (2012) | Jeddah | At least 10 moths to 36 months | Not | dmft: (4.08) (SD 3.70) | |||

| Al Dosari et al. (2004) | Riyadh & Qaseem | 6 to 7 years 12–13 years |

91.2% | 8.8% | Riyadh: dmft: (6.53) (SD: 4.3) DMFT: (5.06) (SD:3.65) |

Riyadh: d= (5.67) D= (4.65) |

|

| Qaseem: dmft: (6.35) (SD: 3.83) DMFT: (4.53) (SD:3.57) |

Qaseem: d= (5.28) D= (4.11) |

||||||

| Al Malik and Rehbini, (2006) | Jeddah | 6_7 years | Male (150) Female (150) |

96% | 4% | dmft: (8.06) (SD: 4.04) DMFT: (0.41) (SD:0.86) |

d= (6.92) (SD:3.94) D= (0.40) (SD:0.83) |

| Al Shahrani et al. (2015) | Dammam | 9–11 years | Male (307) | 66.4% | 33.6% | dmft: (5.61) (SD: 3.01) | d = (4) (SD:2.83) |

| Al-hebshi et al. (2015) | Jazan | 6–12 years | Male (142) Female (128) |

93% | 7% | DMFT: (1.98) (SD: 2.10) | D = (1.89) (SD:2.10) |

| Al-Jobair et al. (2013) | Riyadh | 4_12 years Orphan |

Male (69) Female (21) |

96% | 4% | dmft: (2.90) (SD: 2.51) dmfs:(5.51) (SD:7.36) DMFT: (2.80) (SD:2.12) DMFS: (3.49) (SD:3.31) |

The (d) compound from dmfs is d= (3.80) (SD: 4.17). The (D) compound from DMFS is D= (3.18) (SD: 2.70) |

| 4–12 years Non-orphan |

Male (69) Female (21) |

90% | 10% | dmft: (3.23) (SD: 3.20) dmfs: (5.51) (SD:7.36) DMFT: (1.99) (SD: 2.29) DMFS: (1.97) (SD: 2.62) |

The (d) compound from dmfs is d = (2.03) (SD:4.13) The (D) compound from DMFS is D = (0.90) (SD: 2.10) |

||

| AlMobeeriek 2012 | Riyadh | 20_50 years | Male (59) Female (41) (Psychological) |

Not recorded | Not recorded | DMFT: (13.81) | D=(2.95) (SD: 2.88) |

| Male 59 Female (25) (Normal) |

Not recorded | Not recorded | DMFT: (10.48) | D= (6.21) (SD: 4.87) | |||

| AL-BANYAN et al. (2000) | Riyadh | 5_12 years | Male (154) Female (118) |

99.3% | 0.7% | dmft: (3.8) (SD:3.2) DMFT: (3.8) (SD: 3.2). (Notice there are sub) |

Decayed primary teeth (70%) Decayed permanent teeth (41%) |

| Al Dosari et al. (2011) | Saudi | 6–7 years old 12–13 years old 15–18 years old |

Male (6100) Female (6100) |

Not recorded | Not recorded | dmft: (2.68–7.07) DMFT: (1.81–4.70) |

d primary teeth (86%) D permanent teeth (90%) |

| Alhammad et al., 2010 | Riyadh | 3 to 6 7 to 9 10 to 12 10 to 12 |

Male (82) Female (58) |

(98.6%) | 1.4% | DMFS: (18.8) (SD: 16.3). | DS= (10.9) (SD: 7.5) |

| DMFS: (23.4) (SD:17.7). | DS = (15.4) (SD:12.1) | ||||||

| DMFS: 20.5 SD (14.0). | DS= (12.4) (SD: 9.7) | ||||||

| Al Malik et al. (2001) | Jeddah | 2 to 5 years old | Male (511) Female (476) |

73% | 27% | Over all dmft: (4.8) (SD:4.87) Over all dmfs: (12.67) (SD:15.46) |

|

| Age 3: dmft: (3.59) (SD: 4.74) dmfs: (8.64) (SD: 13.59) | |||||||

| Age 4: dmft: (4.82) (SD: 4.89) dmfs: (12.56) (SD: 15.33) | |||||||

| Age 5: dmft (5.09) (SD: 4.85) | |||||||

| AL Qahtani and Wyne (2008) | Riyadh | 6_7 years old 11_12 years old |

Female (219) | Age (6_7): dmft: (7.58) (SD: 2.02) Deaf: dmft: (7.35) (SD: 3.82) DMFT: (1.67) (SD: 1.67) Deaf DMFT: (0.87) (SD: 1.25) |

(d) = (6.33) (SD: 2.74) (Deaf) (d)= (7.9) (SD: 3.55) (D)= (1.67) (SD:1.67) Deaf (D)= (0.87) (SD: 1.25) |

||

| Age (11_12): dmft: (1.0) (SD: 1.9) DMFT: (5.12) (SD:3.45) Deaf dmft: (2.11) (SD: 2.53) Deaf DMFT: (5.81) (SD: 2.95) |

(d)= (1.0) (SD: 1.9) (D)= (3.76) (SD (2.66) Deaf (d)= (1.0) (SD: 2.37) Deaf (D)= (5.16) (SD: 2.62) |

||||||

| Alshammary 1999 | Saudi | 12_13 Years old | Male (937) Female (937) |

Rural: 64% | 36% | DMFT: (2.65) (SD: 2.62). | (D)= (2.38) (89.81%) |

| Urban: 74% | 26% | DMFT: 2.69 SD (2.57). | (D)= (2.41) (89.59%) | ||||

| Amin and Al-Abad 2008 | AL_Hassa | 10 _14 Years old | Male (1115) | 68.9% | 31.1% | Not record | Not record |

| Atieh (2008) | Dammam | 60 years old | Male (95) Female (65) |

NS | NS | DMFT: (20.7) (SD: 5.3) GOHI-ar: (32.1) (SD:122) |

Not record |

| Brown 2009 | Riyadh | 5 Years old | Male (203) Female (183) |

Healthy: 84% | 16% | deft: (6.25) (SD: 4.71) | d = 79.3% |

| Unhealthy: 91.9% | 8.9% | deft: (9.91) (SD: 5.61) | d = 79.5% | ||||

| Fadel et al., 2010 | Riyadh& Jeddah | Mean 38 years old (SD: 15) | Male (76) Female (36) |

NS | NS | RDT: (0.6) (SD: 2) | D = (5) (SD: 4) |

| Farooqi et al., 2015 | Dammam | 6–9 years | Male (406) | 77.8% | 22.2% | dmft: (3.66) (SD: 3.17) | (d)= (3.28) (SD: 2.92) |

| 10–12 years old | 68%. | 32% | DMFT: (1.94) (SD: 2.0) | (D)= (1.76) (SD:1.85) | |||

| Farsi 2008 | Jeddah | 6–11 years old | Male (179) Female (133) |

99.04% | 0.96% | DMFT: (2.93) (SD:2.29) | |

| 12–17 years old | DMFT: (6.83) (SD: 4.63) | ||||||

| 18–40 years old | DMFT: (12.51) (SD: 5.45) | ||||||

| Farsi 2010 | Jeddah | 4 years old | Male (204) Female (306) |

dmft: (3.73) | |||

| 5 years old | dmft: (4.13) | ||||||

| Gandeh and Milaat(2000) | Jeddah | Male (39,206) Female (43,044) |

83% | 17% | Not recorded | Not recorded | |

| Mannaa et al. (2013) | Jeddah | 4_6 years old | dmft: (9.0) (SD: 5.0) | (d)= (8.0) (SD: 5.1) | |||

| 12_14 years old | DMFT: 5.8 SD (4.1) | (D)= (4.5) (SD: 3.7) | |||||

| 37 years old (SD: 4.5) | DMFT: 12.4 SD (5.3) | (D)= (5.5) (SD: 3.9) | |||||

| Mardard 2009 | Jeddah | >18 years old | Male (100) Female (100) |

DMFS (Endo): (48.7) (SD: 21.8) | (D)= (5) (SD: 5.7) | ||

| DMFS (non-endo): (33.6) (SD: 22.5) | (D)= (7.5) (SD: 9.8) | ||||||

| Paul 2003 | Al Kharj (Riyadh) | 5 years old | Male (53) Female (50) |

83.5% | 16.5% | dmft: (7.1) | 82% (d) = 5.8 (SD 5.0) |

| Quadri et al. (2015) | Jazan | 6–15 years old | Male (520) Female (333) |

91.3% | 8,7% | Not recorded | Not recorded |

| Wyne et al., 2003 | Riyadh | 7–11 years old | 94.4% | 5.6% | dmft: (6.3) (SD: 3.5) | (d)= (4.9) (SD: 3.1) (78%) | |

| DMFT: (1.6) (SD: 1.5) | (D) = (1.5) (SD: 1.4) (93%) | ||||||

| Wyne 2004 | Central area | 12–13 years old | Male (723) Female (684) |

90.5%. | 9.50% | ||

| 15–19 years old | 90.90% | 9.10% | |||||

| Wyne 2008 | Riyadh | 3–5 years old | Male (379) Female (410) |

74.8% | 25.2% | dmft: (6.1) (SD: 3.9) | (d)= (4.66) |

| Wyne et al., 2002 | Riyadh | 55 moths old (SD: 20.0) | Male (34) Female (40) |

100% | 0% | ||

| Wyne et al., 2002 | Al-Hassa | 2–5 years old | Male (164) Female (158) |

62.7% | 37.3% | dmft: (2.92) (SD: 3.51) | (d)= (2.62) (SD:3.36) |

| Wyne et al., 2001 | Riyadh | 2–6 years old | Male (571) Female (445) |

27.3% | 72.7% | Overall: dmft (8.6) (SD: 3.4) | For all (d) = (7.6) (SD: 3.5) 83.6% |

| Age 2: dmft (6.7) (SD: 4.7) | |||||||

| Age 3: dmft:(6.9) (SD: 3.7) | |||||||

| Age 4: dmft: (8.5) (SD: 3.3) | |||||||

| Age 5: dmft: (9.2) (SD: 3.3) | |||||||

| Age 6: dmft: (9.3) (SD: 2.3) | |||||||

| Wyne et al., 2001 | Qaseem | 4–10 years old | Male (106) Female (47) |

Mean aged 4.0 SD (1.4) 21.8% | 79.2% | DMFT: (0.91) (SD: 2.42) | |

| Mean aged (9.7 SD (2.9) 19.7% | 81.3% | DMFT: (0.74) (SD: 1.48) | |||||

| Mansour et al., 2000 | Riyadh | 6_7 years old | Female (200) | Public school 92.9% | 7.1% | dmft: (6.0) (SD: 3.7) | (d)= (4.8) (SD: 3.6) |

| Military schools 97% | 3% | dmft: (8.1) (SD: 4.1) | (d)= (6.3) (SD: 4.2) | ||||

| Al Janakh 2016 | Hail | 16 to 18 years old | Male | 79% | 21% | DMFT: (3.49) (SD: 2.78) | (D)= (2.68) (SD 2.27) |

| Al Otaibi et al., 201755 | Riyadh | 5–6 years old | Male (127) Female (97) |

72.8% | 27.2% | dmft: (3.96) (SD: 3.85) | (d)= (3.22) (SD 3.55) |

| Al Shahrani et al., 2018 | Asir | 15 to 17 years old | Male (3411) | 72.9% | 27.1% | DMFT: (4.3) (SD: 5.59) | (D)= (3.1) (SD 3.34) |

| Al-Meedni and Al-Dlaigan 2016 | Riyadh | 3 to 5 years old | Male (184) Female (204) | 69% | 31% | dmft: (3.4) (SD: 3.6) | |

| Alghamdi and Almahdy 2017 | Riyadh | 14 to 16 years old | Male (610) | 54.1% | 45.9% | DMFT: (1.26) | (d)= (4.66) |

| Alhadban et al., 2018 | Riyadh | 6 to 8 years old | Male (578) | 83% | 17% | dmft: (4.3) (SD: 2.96) | |

| Al Amri et al., 2017 | Riyadh | 3 to 5 years old | Male (1571) | 80% | 20% | dmft: (4.30) | (d) = (3.15) |

| Al Osaimi et al., 2017 | Riyadh | 3 to 5 years old | Male (255) Female (275) |

85.5% | 14.5% | dmft: (5.54) (SD: 3.49) | Not recorded |

| Al Zahidy 2017 | Jeddah | 12 to 14 years old | Male (1123) Female (990) |

89.2% | 10.8% | Not recorded | Not recorded |

| AL-Otsibi et al., 2016 | Qassem | 6 to 12 years old | Male (121) | 57% | 43% | Not recorded | Not recorded |

Assessment of risk of bias

All included studies were assessed of potential risk of bias using a modification of the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) appraisal tool; these findings were then tabulated.12 The NOS items included sample methods, sample size, outcomes validity, outcomes reliability, confounders identified, and dealing with confounding factors. FA, LOM, and AMG assessed the studies.

Data analysis

To interpret the findings from the included studies, caries data were plotted according to geographical location, separating data by primary and permanent dentition. Narrative synthesis analysis was applied.

Results

Search results

A total of 167 articles were found through the electronic search. These were imported into Endnote X9. Only one duplicate record was identified and deleted. Two additional records were identified through hand searching.

After screening of titles and abstracts, 71 records appeared to meet the inclusion criteria. However, on further assessment, 22 were excluded due to being multiple publications of the same study, not primary studies, or not providing data on dental caries experiences. The final number of studies included in the review was 49 (Figure 1). All studies were cross-sectional in design.

Figure 1.

PRISMA Flow Chart.

Risk of bias

None of the identified studies scored ‘Yes’ for all domains assessed. However, nine studies were considered to be of moderate quality, scoring ‘Unclear’ for one or two items, but ‘Yes’ for all others. All others studies scored ‘No’ for at least one item. The summary of the risk of bias assessment is presented in (Table 1).

Table 1.

Assessment of included studies using a modified Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS).

| Study | Sampling strategy | Sample size | Responders/non-responders | Valid outcome assessment | Reliable outcome assessment | Confounders identified | Confounders appropriately handled |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Bhayat & Ahmad, 2014) | Y | Y | ? | Y | Y | N | N |

| (Al Agili & Alaki, 2014) | Y | Y | ? | Y | ? | Y | Y |

| (Al Agili & Park, 2012) | Y | Y | ? | Y | Y | Y | ? |

| (Alaki et al., 2013) | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| (Alkarimi et al., 2014) | Y | ? | ? | Y | Y | Y | ? |

| (Alamoudi et al., 2012) | N | N | N | Y | Y | Y | N |

| (AlDosari et al., 2004) | Y | Y | ? | Y | ? | Y | Y |

| (Al-Malik & Rehbini, 2006) | Y | Y | ? | Y | Y | ? | ? |

| (Al-Shahrani et al., 2015) | ? | N | ? | Y | Y | ? | ? |

| (Al-hebshi et al., 2015) | ? | N | ? | Y | Y | N | N |

| (Al-Jobair et al., 2013) | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | ? | ? |

| (Al-Mobeeriek, 2012) | Y | N | N | ? | N | Y | N |

| (Al-Banyan et al., 2001) | Y | N | ? | Y | N | Y | Y |

| (Aldosari et al., 2010) | Y | ? | N | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| (Alhammad & Wyne, 2010) | N | N | N | Y | N | Y | ? |

| (Al-Malik et al., 2001) | Y | Y | ? | Y | ? | Y | Y |

| (Al-Qahtani & Wyne, 2004) | Y | Y | ? | Y | Y | N | N |

| (Al-Shammery, 1999) | Y | Y | ? | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| (Amin & Al-Abad, 2008) | Y | Y | ? | Y | Y | ? | ? |

| (Atieh, 2008) | Y | Y | N | Y | N | Y | Y |

| (Brown, 2009) | Y | N | N | Y | Y | ? | ? |

| (Fadel et al., 2011) | Y | N | ? | Y | Y | Y | N |

| (Farooqi et al., 2015) | Y | Y | ? | Y | N | N | N |

| (Farsi, 2008) | Y | N | N | Y | Y | ? | ? |

| (Farsi, 2010) | Y | Y | ? | Y | Y | N | N |

| (Gandeh & Milaat, 2000) | Y | Y | N | Y | N | Y | Y |

| (Khan, 2003) | Y | Y | N | Y | N | N | N |

| (Mannaa et al., 2013) | N | N | N | Y | Y | N | N |

| (Merdad et al., 2010) | Y | N | ? | Y | Y | Y | N |

| (Paul, 2003) | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N | N |

| (Quadri et al., 2015) | Y | Y | ? | Y | N | Y | Y |

| (Wyne et al., 2002) | Y | Y | ? | Y | Y | N | N |

| (Wyne, 2004) | Y | N | ? | Y | N | N | N |

| (Wyne, 2008) | Y | Y | ? | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| (Wyne et al., 2002) | Y | N | ? | Y | N | Y | ? |

| (Wyne et al., 2002) | Y | Y | ? | Y | Y | N | N |

| (Wyne et al., 2001) | Y | N | ? | Y | ? | N | N |

| (Wyne et al., 2001) | N | N | N | Y | ? | ? | ? |

| (Mansour, 2000) | Y | N | ? | Y | N | N | N |

| (Al Zahidy, 2017) | N | N | N | Y | Y | N | N |

| (Alotaibi et al., 2017) | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N | N |

| (Alosaimi et al., 2017) | Y | N | ? | Y | Y | Y | ? |

| (Aljanakh et al., 2016) | Y | ? | N | Y | Y | N | N |

| (Alamri et al., 2017) | Y | ? | N | Y | ? | N | N |

| (Alghamdi & Almahdy, 2017) | N | N | N | Y | Y | Y | N |

| (Al-Meedani & Al-Dlaigan, 2016) | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | N |

| (Alshahrani et al., 2018) | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N | N |

| (Al-Otaibi et al., 2016) | N | N | N | Y | N | N | N |

| (Alhabdan et al., 2018) | Y | Y | ? | Y | Y | Y | ? |

“Each of those items were marked either Y= Yes, N No or? = Not clear. Each item that received a Yes was scored “1”; items were scored zero if they received a No and “0.5” if they were unclear. The total account of the scores for every study will help the reviewers to categorise the studies into three types to clarify their quality; the scores ranged from 0 to 6. Studies scoring 5 and above will be considered high quality, studies ranging from 4 to 5 will be considered moderate studies, and studies scoring lower than 4 will be considered low quality.”

Sampling

Forty studies (82%) included information about sampling methods. Random sampling was used in 33 of the studies, of which three used random sampling based on the fluoride concentration zone.8,13,14 Six studies included all their target populations. Finally, only one study used a convenience sampling approach.15 Subsequently, seven studies did not indicate the sampling process used. The sampling method was not clear in two studies.

Sample size

The sample sizes across the included studies ranged from 74 to 82,250 participants. Almost half of the studies (49%; 23 studies) justified their sample size. For 11 studies (23%), the justification of sample size was unclear. The remainder did not justify their sample size.

Responders/Non-responders

All included studies either failed to include or had vague descriptions regarding the comparison of responders and non-responders.

Valid outcome assessment

In terms of the tools used to measure dental caries prevalence, all the included studies used a valid dental caries measurement. Forty-six studies used the DMFT index to quantify the extent of dental caries, with 39 following the WHO diagnosis criteria. Of the remaining studies, two used the Basic Screening Survey (BSS). Finally, one study used the Arabic version of the Oral Health Questionnaire (GOHAI-Ar) and the DMFT index.

Reliable outcome assessment

More than half (63%, n = 31) of the studies had an outcome reliability evaluation. However, 12 studies did not, and it was unclear if the outcome assessment was reliable or not for six studies.

Confounding factors – identified

Fewer than half of the studies (43%, n = 21) listed potential confounding factors. These included socio-economic status (SES), oral hygiene practice, water fluoridation, smoking habits, and sugar consumption. Details of these factors are listed in (Table 2).

Table 2.

Studies indicated the risk factors.

| Study name | SES indicator(s) used |

|---|---|

| (Al Agili & Alaki, 2014) | Parents education and type of home |

| (Al Agili & Park, 2012) | Income and parents' education and smoking status |

| (Alaki et al., 2013) | Parents education, oral health practice and sugar consumption |

| (Alkarimi et al., 2014) | Family income and parents' education |

| (Al-Shahrani et al., 2015) | Family income, parents' education, sugar consumption and oral health practice |

| (Al-Malik et al., 2001) | Mother's education level and father's job |

| (Al-Malik & Rehbini, 2006) | School type (military school) |

| (Al-Shammery, 1999) | House size and type and sugar consumption |

| (Gandeh & Milaat, 2000) | House size |

| (Quadri et al., 2015) | Family income and parents' education level |

| (Wyne., 2008) | School type |

| (Wyne et al., 2002) | Parents' education level |

| (Alghamdi & Almahdy., 2017) | Parents' education level and house type |

| (Alhabdan et al., 2018) | School type, parents' education, type of school and Oral health practice |

| (Al-Banyan et al., 2001) | Oral health practice |

| (Alosaimi et al., 2017) | Oral health practice and sugar consumption |

| (Alamoudi et al., 2012) | Diet and sugar consumption |

| (Al-Mobeeriek, 2012) | smoking status |

| (Atieh, 2008) | smoking status |

| (Aldosari et al., 2010) | Water fluoridation |

| (AlDosari et al., 2004) | Water fluoridation |

Confounding factors – adjusted for

Among the studies that identified risk factors, only 31% (n = 15) adjusted for confounding factors, while 46% (n = 23) of the studies did not. In almost a quarter (23%, n = 11) of the studies, adjustment for confounding was unclear.

Study settings

The studies were divided into three main geographical settings:

-

-

Two studies were national surveys covering the whole country

-

-

Three studies were conducted across two provinces; Riyadh and two other cities (Jeddah and Qaseem).

-

-

Forty-four studies were conducted in a single Saudi city (Almadinah Almunawwarah, Jeddah, Dammam, Riyadh, Jazan, Al Hassa, Al Kharj, Qaseem, Ha'il, and Asir).

Target population

National surveys

The two national surveys recruited children who attend either primary or intermediate schools with ages ranging from six to 18 years old.7,13 One national survey recruited children based on SES and living place (urban or rural) to compare dental caries experience in urban and rural settings of all SES.7 The second study, conducted by Aldosari et al. (2010),13 recruited participants based on water fluoridation concentration to measure the prevalence of dental caries in each area and examine the effects of water fluoridation on dental caries prevalence.

Cross-province surveys

The three studies that made comparisons across provinces recruited the sample. Based either on oral health condition or water fluoridation zone. Fadel et al. (2011) evaluated the dental caries prevalence in adult periodontal patients with a mean age of 38 years old in Riyadh and Jeddah.16 AlDosari et al. (2004) and Wyne (2004) recruited their samples from primary/intermediate schools in Riyadh and Qaseem according to water fluoridation concentrations; the age ranged from six to 19 years in both studies.8,14

Jeddah

Fourteen studies were conducted in Jeddah to measure the prevalence of dental caries. The age range was from ten months to 40 years old. The youngest participants were aged from ten months to three years and were recruited alongside their mothers by Alamoudi et al. (2012).17 This study recruited mothers who attended the dental hospital in Jeddah. Also, Mannaa et al. (2013) recruited mothers with their children as volunteers who visited the King Abdul-Aziz University (KAU) dental clinic.18 In both studies, the mothers were aged above 25.

Two studies recruited children from nursery schools;19,20 the age ranged from two to five years. Three studies recruited children aged six to 12 years from primary schools.6,10,21 Al-Malik et al. (2006) and Alkarimi et al. (2014) recruited children from primary military schools.6,10 Al Agili et al. (2014) recruited their sample of children from nine to 14 years old from both primary and intermediate schools.22 Al Agili et al. (2012) evaluated the oral health status in adolescents, using smokeless tobacco among high-school students aged 16 to 20 years old.23 Al Zahidy (2017) recruited the sample from high-school students aged 16 to 18 years old.24 Alaki et al. (2013) evaluated the effects of asthma and asthma medication on dental caries in children aged five to 13 years old.25 Farsi (2008) recruited from those who had attended the dental clinic at KAU, with participants ranging from six to 40 years old.26 One study recruited adults only, focusing on adults with endodontically treated teeth; they were above 18 years old.27

Riyadh

Of the 17 studies conducted in Riyadh, 14 were conducted on children, with ages ranging from three to 12 years. Of these 14 studies, six focused on specific populations. Alhammad et al. (2010) evaluated dental caries in children with cerebral palsy (CP); Al-Qahtani et al. (2004) recruited their sample from blind, deaf, and mentally disordered children; Brown (2009) assessed the oral health status of children with metabolic disorders, heart diseases, and haematology diseases; Al-Jobair et al. (2013) evaluated dental caries in orphaned children; Al-Banyan et al. (2001) outlined the dental caries prevalence in national guard school children; Mansour (2000) investigated the oral health status of female children in military schools.28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33 The remaining four studies of children recruited preschool/school children in general.9,34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40

Al-Meedani et al. (2016) and Alghamdi et al. (2017) conducted their studies on children in intermediate school aged 14 to 16 years old.41,42 Furthermore, one study was conducted on adults aged between 20 and 50 with psychiatric problems.43

Dammam

Three studies were conducted in Dammam. Two of these studies recruited children and one recruited adults. In the two studies on children, the age ranged from six to 12 years. One study was performed on adults: Atieh (2008) outlined the oral health status of Saudis over 60 years old.44

Al-Hassa

There were two studies conducted in Al-Hassa; the ages ranged from three to 14 years old.11,45

Jizan

Two studies were conducted on public school children. Al-hebshi et al. (2015) focused on male primary school children aged six to 12 years.46 However, Quadri et al. (2015) involved both male and female children from primary and intermediate schools with ages ranging from six to 15 years old.47

Almadinah Almunawwarah

One study was conducted in Almadinah Almunawwarah on male children aged 12 years from public primary schools.48

Al-Kharj

Paul (2003) conducted their study on preschool children aged five years.49

Qaseem

Two studies were conducted in the Qaseem area. The first study focused on children who lived either in the desert of Qaseem or around it; the age ranged from four to ten years.38 The second study was conducted by Al-Otaibi et al. (2016), who recruited children with Down's Syndrome (DS) aged six to 12 years.50

Ha'il

One study was conducted in Ha'il city. Aljanakh et al. (2016) recruited their sample from high school students aged 16 to 18 years.51

Asir

A single study conducted by Alshahrani et al. (2018), targeted all the students in Asir who were aged from 15 to 17.52

All the study characteristics are presented in (Table 3).

Caries data

The caries data can be divided into two groups based on the type of teeth. Two studies by Mannaa et al. (2013) and Mardard et al. (2009) were excluded from the following analysis as they did not provide present the prevalence of caries as a percentage.18,27

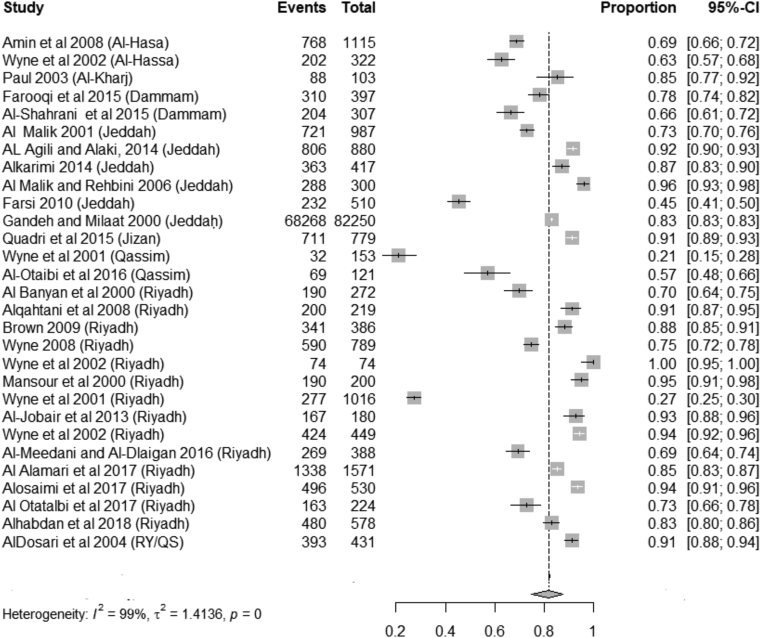

Primary dentition

Twenty-nine studies across seven geographical locations (Al Hassa, Al-Kharj, Dammam, Jeddah, Jazan, Qasseem, Riyadh, Riyadh, and Qassem) and one study across the whole of KSA presented data for primary dentition. There is substantial heterogeneity in the effect estimates (I2 = 99%), even when controlled for location of the study, which made it inappropriate to pool data across the studies. The proportion of caries prevalence within primary teeth ranged from 0.21 to 1.00 (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Effect estimates for caries prevalence in primary dentition.

In Al Hassa, the proportion of dental caries among primary teeth ranged from 0.63 to 0.69; in Al- Kharj, 0.85; Dammam ranged from 0.66 to 0.78; Jeddah ranged from 0.45 to 0.96; Jazan, 0.91; Qassem ranged 0.21 to 0.57; Riyadh ranged 0.27 to 1.00; and in Riyadh and Qassem, 0.91.

Two studies were conducted simultaneously and targeted the same population in two cities of KSA. In Dammam, Farooqi et al. (2015), targeted children aged six to 12 who attended primary schools.53 They recruited 711 children and found the prevalence of dental caries among them to be 0.78. Al-Shahrani et al. (2015) recruited 307 primary school children aged between nine and 11 years and found the proportion of dental caries among them to be 0.66.54 The difference in the prevalence of dental caries can be explained by the difference in age group and sample size.

In Jeddah, Al Agili & Alaki (2014) recruited 1655 children aged nine to 14 years from public primary and intermediate schools; the dental caries proportion was 0.92.22 Alkarimi et al. (2014) recruited 417 children aged six to eight who attended military schools, measuring the dental caries proportion as 0.87.10 This difference can be explained by the variation in ages and sample size as well as the target population.

Moving to Riyadh, three studies were conducted in the same year and had different results regarding the prevalence of dental caries. Alotaibi et al. (2017) recruited 224 pre-school children aged three to four years from rural areas in Riyadh province (Aldwadmi) and recorded the dental caries proportion as 0.73.36 The same age group was recruited by Alosaimi et al. (2017) but with a sample size of 530 children. The study recorded the dental caries proportion as 0.94.35 Alamri et al. (2017) recruited 1844 primary school children aged six to nine and found the dental caries proportion to be 0.86.34 This difference in dental caries can be explained due to the variation in the sample size and age group.

Permanent dentition

Eighteen studies presented data for permanent dentition across eight city locations (Asir, Dammam, Ha'il, Jeddah, Jazan, Almadinah Almunawwarah, Riyadh, Riyadh, and Qaseem) and one study examined the whole of KSA. There is substantial heterogeneity in the effect estimates (I2 = 100%), even when considered by location of the study, which made it inappropriate to pool data across the studies. The proportion for caries prevalence among permanent teeth ranged from 0.05 to 0.99 (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Effect estimates for caries prevalence in permanent dentition.

In Asir, the proportion of dental caries prevalence among permanent teeth was 0.73; 0.68 in Dammam; 0.79 in Ha'il; 0.93 in Jazan; and 0.58 in Almadinah Almunawwarah. In Jeddah, caries prevalence ranged from 0.05 to 0.99; Riyadh ranged from 0.41 to 0.99. In Riyadh and Qaseem, caries ranged from 0.90 to 0.94; and in the whole of KSA, caries prevalence was 0.72.

Discussion

This study aimed to systematically review studies evaluating the prevalence of dental caries in KSA from 1999 to 2019. It identified 49 studies. The proportion of dental caries among primary teeth ranged from 0.21 to 1.00, and in permanent teeth, ranged from 0.05 to 0.99.

The included studies showed a substantial amount of heterogeneity (I2 = 100) regarding the prevalence of dental caries, both in primary and permanent dentition. This heterogeneity between studies came as a result of varying methodologies with different sample sizes, target populations, and geographical settings examined across the studies.

The sample sizes varied, ranging from 74 to 82,250 participants. Furthermore, only 49% of the included studies justified their sample size; the other studies either did not justify their sample size or had unclear justification. Another aspect is population variation, for example, targetting specific populations, such as those with specific medical conditions including cleft lip and palate, blind, deaf, mental disorders, children with cerebral palsy (CP), orphaned children, participants with asthma. Previous studies have shown such conditions are associated with a high risk of dental caries.56,57 This is supported by the findings of the included studies. Alaki et al. (2013) reported DMFT of 8.96 with asthma and DMFT: 8.03 without asthma; DMFT: (2.16) with asthma; DMFT: (1.96) without asthma. Brown (2009) reported dental caries among children with cleft lip and palate as 0.92, while in healthy children dental caries prevalence was 0.86.30

The location of the studies also varied, with most of the studies conducted in two main cities: Riyadh (35%) and Jeddah (29%), leaving some parts of KSA with either a single or no studies at all.

A previous systematic review conducted to measure the prevalence of dental caries in KSA among school children concluded that 70% of children in primary school had caries of permanent dentition, while 80% of them had caries in their primary dentition.2 However, this review did not assess the quality of the studies included in this review. Without exploring the quality of the studies, it is difficult to interpret differences in the identified rates of caries.

As a result, this present systematic review is limited by the quality of the studies included. This, alongside the significant heterogeneity, means that the findings can only be interpreted with caution. That makes the present study the first review of its kind to assess the quality of primary studies evaluating dental caries in KSA.

The prevalence of dental caries in countries bordering KSA were found to be lower. In Kuwait, Al-Mutawa et al. (2006) found the dental caries prevalence among children aged 12 to 14 years to be 0.18, and Ali (2016) found dental caries among children aged 12 to 16 years to be 0.52.58,59 In Oman, Al-lsmaily et al. (1996) found the dental caries prevalence among children aged 12 years to be 0.58.60 In Qatar, the dental caries prevalence among children aged five to 15 years old is reported as 0.7361 and 0.85 among children aged 12 to 14 years.62

Regarding reporting outcomes other than dental caries, few studies reported clear data on issues such as diet and oral hygiene behaviours. Regarding oral health behaviours, none of the included studies reporting on this indicate high levels of oral health hygiene/oral health practice. Moreover, some studies report the consumption of foods high in sugar. There is clear, well-established evidence that brushing teeth with fluoride toothpaste is effective in preventing dental caries.63,64 Similarly, the role of high sugar consumption in the development of dental caries is well established,65 with the WHO recommending that sugar consumption be reduced, and strongly recommending that sugar should provide below 10% of the total energy provided by food.66

Despite public dental services being free in KSA, none of the included studies provided any information regarding access to dental services. Only a few studies gave some information about dental insurance, however, they did not indicate how this could help in improving oral health.

Due to the methodological weaknesses of the included studies, the clinical heterogeneity demonstrated and the gaps in the populations/geographical areas covered, the results of this study cannot be generalised to the general population of KSA. To truly develop a good understanding of dental caries, and to determine whether their levels are increasing or decreasing, it would be helpful to develop a national protocol to conduct regular surveys of both adults and children. Such methods exist in other countries; for example, in the UK there are regular epidemiological surveys, such as Public Health England (2012), which can be used to help inform the dental public health policy.67 Having such survey systems in KSA will help the country run regular surveys to measure the prevalence of dental caries or other dental conditions. That will help provide accurate and up-to-date information on dental caries across KSA and give policymakers reliable indications of where dental services are needed.

Conclusion

This study found that the methodology quality of the included studies is poor in general. Furthermore, the dental caries proportion level ranged from 0.05 to 0.99 and from 0.21 to 1.00 for permanent and primary teeth. This indicates that the prevalence of dental caries in KSA is high. However, the current data do not provide a complete assessment of dental caries across KSA.

Recommendations

This study indicates the need to have criteria regarding future research to measure the prevalence of dental caries across KSA.

Source of funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Ethical approval

The authors confirm that this review had been prepared in accordance with COPE roles and regulations. Given the nature of the review, the IRB review was not required.

Consent

As there were no participants in this study, consent was not required.

Authors' contributions

FA, LOM, and AMG conceived and designed the study, conducted research, critiquing the included studies, and wrote the final manuscript. HA and FA analysed and interpreted data. MA and WS developed the methodology and counted the factor biases. AMG supervised the whole process. All authors have critically reviewed and approved the final draft and are responsible for the content and similarity index of the manuscript.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank the University of Ha'il, Professor Peter Imrey and Mr. George Stroud.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Taibah University.

References

- 1.World Health Organization . 2012. World health statistics 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Al Agili D.E. A systematic review of population-based dental caries studies among children in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Dent J. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.sdentj.2012.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Khan S.Q., Khan N.B., ArRejaie A.S. Dental caries. A meta analysis on a Saudi population. Saudi Med J. 2013:744–749. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Al-Ansari A. Prevalence, severity, and secular trends of dental caries among various saudi populations: a literature review. Saudi J Med Med Sci. 2014 doi: 10.4103/1658-631x.142496. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Al-Malik M., Holt R.D. The prevalence of caries and of tooth tissue loss in a group of children living in a social welfare institute in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Int Dent J. 2000 doi: 10.1111/j.1875-595x.2000.tb00568.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Al-Malik M.I., Rehbini Y.A. Prevalence of dental caries, severity, and pattern in age 6 to 7-year-old children in a selected community in Saudi Arabia. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2006 doi: 10.5005/jcdp-7-2-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Al-Shammery A.R. Caries experience of urban and rural children in Saudi Arabia. J Publ Health Dent. 1999 doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.1999.tb03236.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.AlDosari A.M., Wyne A.H., Akpata E.S., Khan N.B. Caries prevalence and its relation to water fluoride levels among schoolchildren in Central Province of Saudi Arabia. Int Dent J. 2004 doi: 10.1111/j.1875-595X.2004.tb00299.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alhabdan Y.A., Albeshr A.G., Yenugadhati N., Jradi H. Prevalence of dental caries and associated factors among primary school children: a population-based cross-sectional study in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Environ Health Prev Med. 2018 doi: 10.1186/s12199-018-0750-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alkarimi H.A., Watt R.G., Pikhart H., Sheiham A., Tsakos G. Dental caries and growth in school-age children. Pediatrics. 2014 doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-0846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Amin T.T., Al-Abad B.M. Oral hygiene practices, dental knowledge, dietary habits and their relation to caries among male primary school children in Al Hassa, Saudi Arabia. Int J Dent Hyg. 2008 doi: 10.1111/j.1601-5037.2008.00310.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wells G., Shea B., O’Connell D., Peterson J., Welch V., Losos M. Oxford; 2012. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality if nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses.http://http//www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp Available from URL. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aldosari A.M., Akpata E.S., Khan N. Associations among dental caries experience, fluorosis, and fluoride exposure from drinking water sources in Saudi Arabia. J Publ Health Dent. 2010 doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.2010.00169.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wyne A.H. The bilateral occurrence of dental caries among 12-13 and 15-19 year old school children. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2004 doi: 10.5005/jcdp-5-1-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Al Agili D.E., Park H.K. Oral health status of male adolescent smokeless tobacco users in Saudi Arabia. East Mediterr Health J. 2013 doi: 10.26719/2013.19.8.711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fadel H., Al Hamdan K., Rhbeini Y., Heijl L., Birkhed D. Root caries and risk profiles using the Cariogram in different periodontal disease severity groups. Acta Odontol Scand. 2011 doi: 10.3109/00016357.2010.538718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alamoudi N.M., Hanno A.G., Sabbagh H.J., Masoud M.I., Almushayt A.S., El Derwi D.A. Impact of maternal xylitol consumption on mutans streptococci, plaque and caries levels in children. J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2012 doi: 10.17796/jcpd.37.2.261782tq73k4414x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mannaa A., Carlén A., Lingström P. Dental caries and associated factors in mothers and their preschool and school children - a cross-sectional study. J Dent Sci. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.jds.2012.12.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Al-Malik M.I., Holt R.D., Bedi R. The relationship between erosion, caries and rampant caries and dietary habits in preschool children in Saudi Arabia. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2001 doi: 10.1046/j.0960-7439.2001.00320.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Farsi N. Developmental enamel defects and their association with dental caries in preschoolers in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Oral Health Prev Dent. 2010 doi: 10.3290/j.ohpd.a18831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gandeh M.B.S., Milaat W.A. Dental caries among schoolchildren: report of a health education campaign in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. East Mediterr Heal J. 2000;6:396–401. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Al Agili D.E., Alaki S.M. Can socioeconomic status indicators predict caries risk in schoolchildren in Saudi Arabia? A cross-sectional study. Oral Heal Prev Dent. 2014 doi: 10.3290/j.ohpd.a31669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Al Agili D.E., Park H.K. The prevalence and determinants of tobacco use among adolescents in Saudi Arabia. J Sch Health. 2012 doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2011.00676.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Al Zahidy H.A. Prevalence of dental caries among children in Jeddah-Saudi arabia-2015. EC Dent Sci. 2017;8:15–20. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alaki S.M., Ashiry EA Al, Bakry N.S., Baghlaf K.K., Bagher S.M. The effects of asthma and asthma medication on dental caries and salivary characteristics in children. Oral Heal Prev Dent. 2013 doi: 10.3290/j.ohpd.a29366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Farsi N. Dental caries in relation to salivary factors in Saudi population groups. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2008 doi: 10.5005/jcdp-9-3-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Merdad K., Sonbul H., Gholman M., Reit C., Birkhed D. Evaluation of the caries profile and caries risk in adults with endodontically treated teeth. Oral Surgery, Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endodontology. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2010.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alhammad N.S., Wyne A.H. Caries experience and oral hygiene status of cerebral palsy children in Riyadh. Odonto-Stomatol Trop. 2010;33 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Al-Qahtani Z., Wyne A.H. Caries experience and oral hygiene status of blind, deaf and mentally retarded female children in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Odonto-Stomatol Trop. 2004:37–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brown A. Caries prevalence and treatment needs of healthy and medically compromised children at a tertiary care institution in Saudi Arabia. East Mediterr Health J. 2009 doi: 10.26719/2009.15.2.378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Al-Jobair A.M., Al-Sadhan S.A., Al-Faifi A.A., Andijani R.I., Al-Motlag S.K. Medical and dental health status of orphan children in central Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J. 2013;34:531–537. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Al-Banyan R.A., Echeverri E.A., Narendran S., Keene H.J. Oral health survey of 5-12-year-old children of national guard employees in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2001 doi: 10.1046/j.1365-263x.2000.00166.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mansour Magda. Comparison OF caries IN 6-7 year old SAUDI girls attending public and armed forces schools IN riyadh , Saudi Arabia. Saudi Dent J. 2000;12:33–36. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alamri A.A., Aldossary M.S., Alshiha S.A., Alwayli H.M., Alfraih Y.K., Hattan M.A. Dental caries prevalence among primary male schoolchildren in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia: a cross-sectional survey. J Int Oral Health. 2017 doi: 10.4103/jioh.jioh_111_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Alosaimi B., Alturki G., Alnofal S., Alosaimi N., Ansari S.H. Assessing untreated dental caries among private and public preschool children in Riyadh , a cross-sectional study design. J Dent oral Heal. 2017;3(10) [Google Scholar]

- 36.Alotaibi F., Sher A., Khounganian R. Prevalence of early childhood caries among preschool children in dawadmi, Saudi Arabia. IJMSCI. 2017;4:3010–3014. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wyne A.H., Al-Ghorabi B.M., Al-Asiri Y.A., Khan N.B. Caries prevalence in Saudi primary schoolchildren of Riyadh and their teachers’ oral health knowledge, attitude and practices. Saudi Med J. 2002;23:77–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wyne A., al-Dlaigan Y., Khan N. Caries prevalence, oral hygiene and orthodontic status of Saudi Bedouin children. Indian J Dent Res. 2001;12(4):194–198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wyne A.H. Caries prevalence, severity, and pattern in preschool children. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2008 doi: 10.5005/jcdp-9-3-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wyne A.H., Chohan A.N., al-Begomi R. Feeding and dietary practices of nursing caries children in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Odonto-Stomatol Trop. 2002;25:37–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Al-Meedani L.A., Al-Dlaigan Y.H. Prevalence of dental caries and associated social risk factors among preschool children in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Pakistan J Med Sci. 2016 doi: 10.12669/pjms.322.9439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Alghamdi A.A., Almahdy A. Association between dental caries and body mass index in schoolchildren aged between 14 and 16 Years in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. J Clin Med Res. 2017 doi: 10.14740/jocmr2958w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Al-Mobeeriek A. Oral health status among psychiatric patients in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. W Indian Med J. 2012 doi: 10.7727/wimj.2012.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Atieh M.A. Arabic version of the geriatric oral health assessment Index. Gerodontology. 2008 doi: 10.1111/j.1741-2358.2007.00195.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wyne A.H., Al-Ghannam N.A., Al-Shammery A.R., Khan N. Caries prevalence, severity and pattern in pre-school children. Saudi Med J. 2002;23(5):580–584. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Al-hebshi N.N., Abdulhaq A., Quadri M.F.A., Tobaigy F.M. Salivary carriage of Candida species in relation to dental caries in a population of Saudi Arabian primary school children. Saudi J Dent Res. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.sjdr.2014.07.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Quadri F.A., Hendriyani H., Pramono A., Jafer M. Knowledge, attitudes and practices of sweet food and beverage consumption and its association with dental caries among schoolchildren in Jazan, Saudi Arabia. East Mediterr Health J. 2015 doi: 10.26719/2015.21.6.403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bhayat A., Ahmad M.S. Oral health status of 12-year-old male schoolchildren in Medina, Saudi Arabia. East Mediterr Health J. 2014 doi: 10.26719/2014.20.11.732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Paul T.R. Dental health status and caries pattern of preschool children in Al-Kharj, Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J. 2003;24(12):1347–1351. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Al-Otaibi Saud Moflih, Hazem Rizk M.A.R. Prevalence of dental caries, salivary Streptococcus mutans, lactobacilli count, pH level and buffering capacity among children with Down's Syndrome in Al-qassim region, KSA. Int J Contemp Med Res. 2016;3(9):2793–2797. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Aljanakh M., Siddiqui A.A., Mirza A.J. Teachers' knowledge about oral health and their interest in oral health education in hail , Saudi Arabia. Int J Health Sci. 2016 doi: 10.12816/0031223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Alshahrani I., Tikare S., Meer Z., Mustafa A., Abdulwahab M., Sadatullah S. Prevalence of dental caries among male students aged 15–17 years in southern Asir, Saudi Arabia. Saudi Dent J. 2018 doi: 10.1016/j.sdentj.2018.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Farooqi F.A., Khabeer A., Moheet I.A., Khan S.Q., Farooq I., Arrejaie A.S. Prevalence of dental caries in primary and permanent teeth and its relation with tooth brushing habits among schoolchildren in Eastern Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J. 2015 doi: 10.15537/smj.2015.6.10888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Al-Shahrani N., Al-Amri A., Hegazi F., Al-Rowis K., Al-Madani A., Hassan K.S. The prevalence of premature loss of primary teeth and its impact on malocclusion in the Eastern Province of Saudi Arabia. Acta Odontol Scand. 2015 doi: 10.3109/00016357.2014.939709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Alotaibi F., Sher A., Khounganian R. Prevalence of early childhood caries among preschool children in dawadmi, Saudi Arabia. Int J Med Sci Clin Invent. 2017 doi: 10.18535/ijmsci/v4i6.08. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Alavaikko S., Jaakkola M.S., Tjäderhane L., Jaakkola J.J.K. Asthma and caries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Epidemiol. 2011 doi: 10.1093/aje/kwr129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Antonarakis G.S., Palaska P.K., Herzog G. Caries prevalence in non-syndromic patients with cleft lip and/or palate: a meta-analysis. Caries Res. 2013;47(5):406–413. doi: 10.1159/000349911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Al-Mutawa S.A., Shyama M., Al-Duwairi Y., Soparkar P. Dental caries experience of Kuwaiti schoolchildren. Community Dent Health. 2006;23(1) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ali D.A. Evaluation of dental status of adolescents at Kuwait university dental clinic. Oral Heal Prev Dent. 2016 doi: 10.3290/j.ohpd.a35300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Al-lsmaily M., Ai-Khussaiby A., Chestnutt I.G., Stephen K.W., AI-Riyami A., Abbas A. The oral health status of Omani 12-year-olds-a national survey. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1996 doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1996.tb00877.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bener A., Al Darwish M.S., Tewfik I., Hoffmann G.F. The impact of dietary and lifestyle factors on the risk of dental caries among young children in Qatar. J Egypt Public Health Assoc. 2013 doi: 10.1097/01.EPX.0000430962.70261.8e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Al-Darwish M., El Ansari W., Bener A. Prevalence of dental caries among 12-14year old children in Qatar. Saudi Dent J. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.sdentj.2014.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wong M.C.M., Clarkson J., Glenny A.M., Lo E.C.M., Marinho V.C.C., Worthington H.V. Cochrane reviews on the benefits/risks of fluoride toothpastes. J Dent Res. 2011 doi: 10.1177/0022034510393346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Walsh T., Worthington H.V., Glenny A.M., Marinho V.C.C., Jeroncic A. Fluoride toothpastes of different concentrations for preventing dental caries. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007868.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Harris R., Nicoll A.D., Adair P.M., Pine C.M. Risk factors for dental caries in young children: a systematic review of the literature. Community Dent Health. 2004:165–170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.World Health Organization . WHO Libr Cat Data; 2015. WHO Guideline: sugars intake for adults and children. 978 92 4 154902 8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Public Health England . PHE Gatew; 2012. National Dental Epidemiology Programme for England: oral health survey of five-year-old children 2012 A report on the prevalence and severity of dental decay. [Google Scholar]