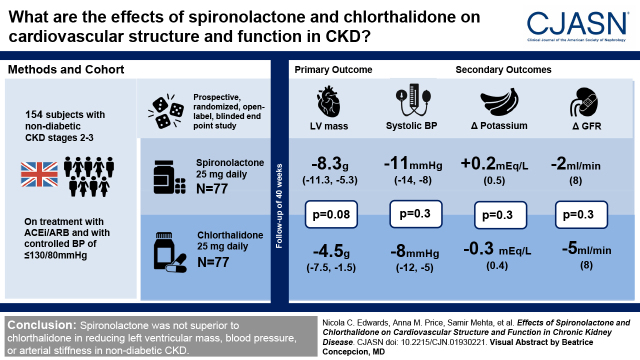

Visual Abstract

Keywords: chronic kidney disease, aldosterone, randomized controlled trials, chlorthalidone, spironolactone, cardiovascular system

Abstract

Background and objectives

In a randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, treatment with spironolactone in early-stage CKD reduced left ventricular mass and arterial stiffness compared with placebo. It is not known if these effects were due to BP reduction or specific vascular and myocardial effects of spironolactone.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

A prospective, randomized, open-label, blinded end point study conducted in four UK centers (Birmingham, Cambridge, Edinburgh, and London) comparing spironolactone 25 mg to chlorthalidone 25 mg once daily for 40 weeks in 154 participants with nondiabetic stage 2 and 3 CKD (eGFR 30–89 ml/min per 1.73 m2). The primary end point was change in left ventricular mass on cardiac magnetic resonance imaging. Participants were on treatment with an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker and had controlled BP (target ≤130/80 mm Hg).

Results

There was no significant difference in left ventricular mass regression; at week 40, the adjusted mean difference for spironolactone compared with chlorthalidone was −3.8 g (95% confidence interval, −8.1 to 0.5 g, P=0.08). Office and 24-hour ambulatory BPs fell in response to both drugs with no significant differences between treatment. Pulse wave velocity was not significantly different between groups; at week 40, the adjusted mean difference for spironolactone compared with chlorthalidone was 0.04 m/s (−0.4 m/s, 0.5 m/s, P=0.90). Hyperkalemia (defined ≥5.4 mEq/L) occurred more frequently with spironolactone (12 versus two participants, adjusted relative risk was 5.5, 95% confidence interval, 1.4 to 22.1, P=0.02), but there were no patients with severe hyperkalemia (defined ≥6.5 mEq/L). A decline in eGFR >30% occurred in eight participants treated with chlorthalidone compared with two participants with spironolactone (adjusted relative risk was 0.2, 95% confidence interval, 0.05 to 1.1, P=0.07).

Conclusions

Spironolactone was not superior to chlorthalidone in reducing left ventricular mass, BP, or arterial stiffness in nondiabetic CKD.

Introduction

CKD stage 1–3 affects >10% of the population of developed countries (1). The risk of cardiovascular disease is higher, with a graded inverse relationship to eGFR, and far exceeds the risk of kidney failure (2). Part of this risk is due to accelerated atheroma, but traditional cardiovascular risk models designed to predict death perform poorly in CKD (3) and nonatherosclerotic changes including left ventricular fibrosis and hypertrophy and arteriosclerosis are important (4). Pathophysiological mechanisms underlying these processes are likely to include activation of the renin-angiotensin system, systemic inflammation, and altered bone mineral metabolism.

Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) are widely used in CKD to control BP and reduce proteinuria, but often fail to suppress the elevated levels of aldosterone that occur in CKD as a result of both aldosterone escape and breakthrough (5). In addition to hypertension, experimental studies have shown that aldosterone exerts numerous adverse cardiovascular effects, including endothelial dysfunction, and prohypertrophic, inflammatory, and fibrotic effects on the myocardium and arterial walls, particularly in the presence of sodium overload as occurs in CKD (6). In a randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, the addition of spironolactone to ACE inhibitors or ARBs reduced left ventricular mass and arterial stiffness and improved left ventricular diastolic function with a satisfactory safety profile, but it was unclear whether these beneficial effects were due to the unique actions of spironolactone or BP reduction (7). This follow-up trial compared the effects of spironolactone with those of an active antihypertensive control drug, chlorthalidone, to achieve equal BP control. Our hypothesis was that spironolactone would cause greater reduction in left ventricular mass and arterial stiffness as a result of its inhibition of the multiple adverse effects of aldosterone.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Treatment Regimens

A multicenter, prospective randomized open-label, blinded end point trial recruiting participants with stage 2 and 3 CKD at four United Kingdom (UK) centers (Birmingham, Cambridge, Edinburgh, and London) between June 2014 and December 2016 (8). Participants were individually randomized into the trial in a 1:1 ratio to either spironolactone 25 mg once daily or chlorthalidone 25 mg once daily for 40 weeks. Randomization was provided by a computer-generated program at the Birmingham Clinical Trials Unit, using a minimization algorithm to ensure balance between the arms with regard to the following important clinical variables: systolic BP (<130 mm Hg, ≥130 mm Hg), age (<55 years, ≥55 years), and sex (male, female). Follow-up was completed by November 2017. Adherence to the Declaration of Helsinki, Ethical (West Midlands National Research Ethics Service September 2013 [13/WM/0304]), Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (Clinical Trials Authorization 21761/0295/001–0001), and US National Institutes of Health database (NCT02502981) approvals were obtained.

Participants

The rationale and detailed trial design have been reported in full (8). In brief, patients were eligible for inclusion if they were aged ≥18 years, had stable CKD stage 2 or 3 (eGFR 30–89 ml/min per 1.73 m2), were taking an ACE inhibitor or ARB, with controlled BP using standard UK guideline BP target values <130/80 mm Hg in 2015. Local investigators were encouraged not to change concomitant antihypertensive medication after study entry unless for a strong clinical indication. Aggregate BP data by treatment arm were reviewed regularly by an independent Blood Pressure Monitoring Committee. The committee was able to mandate changes in randomized treatment to ensure BP in both arms was similar. Exclusion criteria included diabetes mellitus, left ventricular systolic dysfunction (ejection fraction <50%), or severe valvular disease, atrial fibrillation, recent acute myocardial infarction, or other adverse cardiovascular event, and documented previous hyperkalemia or serum potassium at screening of >5.0 mEq/L (8).

Outcome Measures

Investigations were performed at baseline (<6 weeks before initiating study medication) and at 40 weeks postrandomization, with a further “run-out” study at 6 weeks after trial drugs ended (46 weeks). The primary end point was change in left ventricle mass at week 40; secondary end points have been reported (8), but included changes in carotid-femoral pulse wave velocity (cfPWV), office and ambulatory BPs, and safety parameters (hyperkalemia, decline in kidney function of >30%, requiring discontinuation of trial drugs). Analyses of cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (NCE) and cfPWV (research nurses) data were performed by clinicians blinded to treatment allocation and clinical data.

Cardiac Magnetic Resonance Imaging.

Studies were performed on 1.5-T (Avanto/Aera; Siemens, and Discovery; GE) or 3T (Verio, Siemens) scanners. Left ventricular dimensions, function, and mass were assessed in accordance with validated methodology as previously described (9). Data were analyzed in a Core Lab (Birmingham) using CVi 42 software (Circle Vascular Imaging, Canada).

BP and Arterial Function.

Office BP were recorded at each face-to-face clinical review using a semiautomated device. Three readings were performed in the seated position after 5 minutes of rest. The mean of the last two readings were used for analysis (8). Resting BP, 24-hour ambulatory BP monitoring (Mobil-O-Graph; IEM GmbH, Stolberg, Germany), applanation tonometry (SphygmoCor; AtCor Medical, Sydney), and cfPWV were assessed as previously described (10,11).

Biochemical and Safety Monitoring.

Routine hematologic and biochemical parameters were recorded at weeks 1, 2, 4, 8, 24, 40, and 46 after randomization. Modification to the doses of both treatments was made according to protocols (Table 1).

Table 1.

Treatment modification for potassium, eGFR, and sodium levels

| Result | Action |

| Potassium (mEq/L) | |

| Participants on chlorthalidone | |

| >3.5 | No action |

| 3.0–3.5 | Remeasure serum potassium in 2 wk. Dietary advice |

| <3.0 | Stop drug |

| Participants on spironolactone | |

| 5.5–5.9 | Reduce to alternate days |

| 6.0–6.5 | Stop for 1 wk and recommence on alternate day if potassium <5 mEq/L on repeat check |

| >6.5 | Stop trial drug |

| eGFR reduction (%) | |

| <25 | No action |

| 25–30 | Stop trial drug and restart after 1 wk on alternate days |

| >30 | Stop trial drug |

| Sodium (mmol/L) | |

| >135 | No action |

| 135–130 | Remeasure serum sodium in 2 wk |

| <125 | Stop trial drug |

Study Outcomes and Statistical Analysis

The initial design of the study used a coprimary end point of change in left ventricular mass and change in cfPWV to replicate the original Chronic Renal Impairment in Birmingham (CRIB) 2 methodology (7). This required a sample size of 350 participants. However, recruitment was significantly slower than anticipated, and after discussion with the funder and the Trial Steering Committee, the trial design was revised with a single primary end point of change in left ventricular mass. This decision was made blinded to all data and reflected the superior prognostic value of left ventricular mass and technical precision to ensure the study was appropriately powered with a reduced sample size (8). Using an SD of change in left ventricle mass of 13 g (data from CRIB 2) (7), to detect a minimum relevant difference in left ventricular mass of 7 g (12), 63 patients per arm were required to provide 85% power with two-sided α=0.05. After allowing for 15% drop-out, the total sample was 150 patients. The difference of 7 g was chosen as the minimum clinically important difference because this value is at the limits of precision of measurement of left ventricular mass by cardiac magnetic resonance (13). Analyses were conducted as stated in our statistical analysis plan (Supplemental Appendix: Statistical Analyses). In brief, estimates of differences between the groups for the primary and secondary end points are presented with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) and P values from two-sided tests at the 5% significance level. All analyses were on the basis of the intention-to-treat principle and used a model-based analysis with the minimization variables (age, systolic BP, and sex) and baseline values (where available; e.g., left ventricular mass) included in the model as covariates. The chlorthalidone arm was the reference category. Continuous end points were analyzed using a linear regression model to estimate an adjusted mean difference between groups at week 40. For PWV, systolic and diastolic office BP, which were collected over multiple time points, a secondary analysis using mixed-effects linear regression models was performed. Categorical end points were analyzed using a log-binomial regression model to estimate an adjusted relative risk. Sensitivity and exploratory analyses were performed; this included a per-protocol analysis and an analysis where missing data for the primary outcome were imputed using multiple imputation with chained equations. In total, 50 imputations were generated and imputed results were combined using Rubin’s rule. Analyses were undertaken using Stata v15 and SAS v9.3.

Results

Study Population

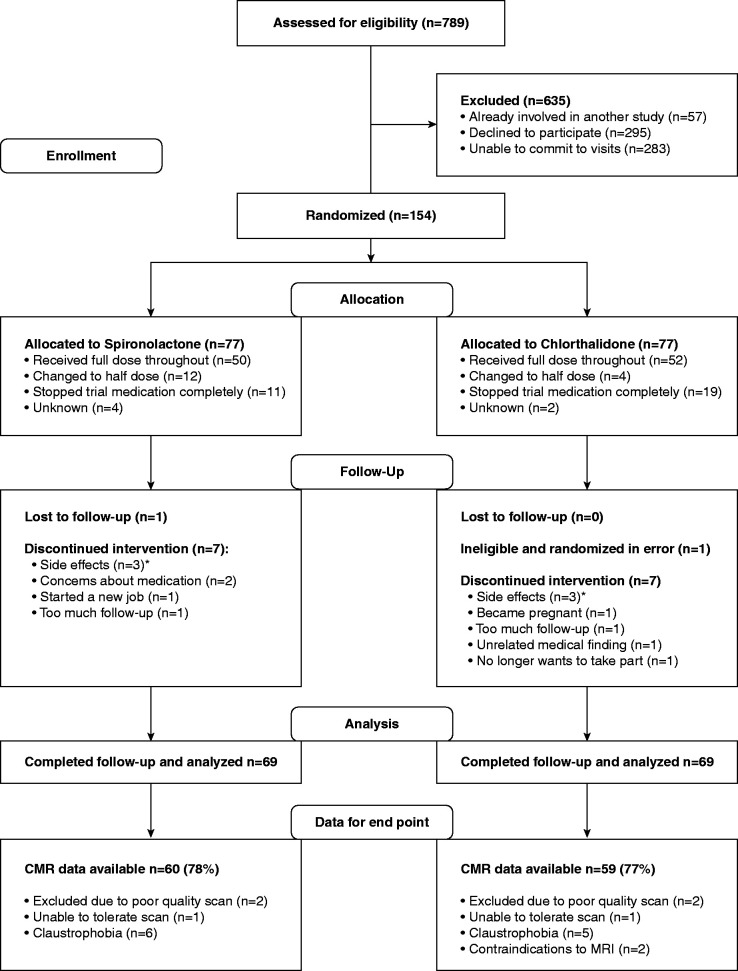

A total of 154 patients were randomized to either spironolactone (n=77) or chlorthalidone (n=77). Participants were well matched at baseline (Table 2). After randomization, a total of 16 participants did not complete the study: eight participants in the spironolactone group (side effects n=3, medication concern n=2, follow-up frequency n=2, and lost to follow-up n=1) and eight in the chlorthalidone group (side effects n=3, follow-up frequency n=2, pregnant n=1, new medical finding unrelated to study n=1, randomization error n=1) (Figure 1). A total of 50 patients randomized to spironolactone remained on full-dose medication and 12 changed to half-dose; in the chlorthalidone group, 52 patients were on full-dose medication and four on half-dose. Adherence to treatment (defined as >70% medication taken by pill count) was 81% for spironolactone and 73% for chlorthalidone.

Table 2.

Baseline patient clinical characteristics

| Characteristics | Spironolactone (n=77) | Chlorthalidone (n=77) |

| Age (yr) | 57 (14) | 56 (15) |

| Male, n (%) | 53 (69) | 53 (69) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 29.5 (5.0) | 27.6 (3.8) |

| Smoking, n (%) | ||

| Never smoked | 37 (48) | 37 (48) |

| Ex-smoker | 35 (46) | 29 (38) |

| Current smoker | 5 (6) | 11 (14) |

| Office systolic BP (mm Hg) | 134 (14) | 135 (14) |

| Office diastolic BP (mm Hg) | 80 (10) | 81 (9) |

| Heart rate (bpm) | 72 (14) | 71 (12) |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dl) | 1.45 (0.46) | 1.32 (0.35) |

| eGFR (ml/min per 1.73 m2) | 52 (16) | 57 (15) |

| Hemoglobin (g/dl) | 13.6 (1.3) | 13.6 (1.6) |

| Cholesterol (mg/dl) | 191 (38) | 184 (40) |

| Serum potassium (mEq/L) | 4.4 (0.4) | 4.5 (0.3) |

| No. of patients on treatment, n (%) | ||

| ACE inhibitors | 42 (55) | 43 (56) |

| Angiotensin receptor blockers | 35 (45) | 34 (44) |

| Beta blockers | 13 (17) | 13 (17) |

| Calcium channel blockers | 33 (43) | 23 (30) |

| Alpha blockers | 13 (17) | 6 (8) |

| Statins | 31 (40) | 35 (45) |

| Etiology of kidney disease, n (%) | ||

| Known pathology | 60 (78) | 59 (77) |

| Primary GN | 29 (48) | 20 (34) |

| Interstitial nephropathies | 5 (8) | 10 (17) |

| Hereditary nephropathy | 15 (25) | 16 (27) |

| Kidney vascular disease | 2 (5) | 4 (7) |

| Hypertensive nephropathy | 4 (7) | 3 (5) |

| Secondary GN | 0 | 3 (5) |

| Other multisystem disease | 2 (3) | 2 (3) |

| Other | 3 (5) | 1 (2) |

| Cardiovascular history, n (%) | ||

| Previous myocardial infarction | 1 (1) | 4 (5) |

| Previous hypertension | 67 (87) | 64 (83) |

| Previous stroke | 1 (1) | 1 (1) |

Values are mean±SD for continuous data. Categorical data are number (percentage). BMI, body mass index; ACE, angiotensin converting enzyme.

Figure 1.

CONSORT diagram: Eligibility, randomization, and follow-up. *Side effects leading to patient withdrawal of spironolactone: inflamed gums, symptomatic hyponatremia, and worsening of polymyalgia rheumatica and back and leg pain. Side effects leading to patient withdrawal of chlorthalidone: dizziness and headache, too many unwanted side effects from being on irbesartan necessary for the trial, and patient concern about kidney function. CMR, cardiac magnetic resonance imaging.

Primary End Point

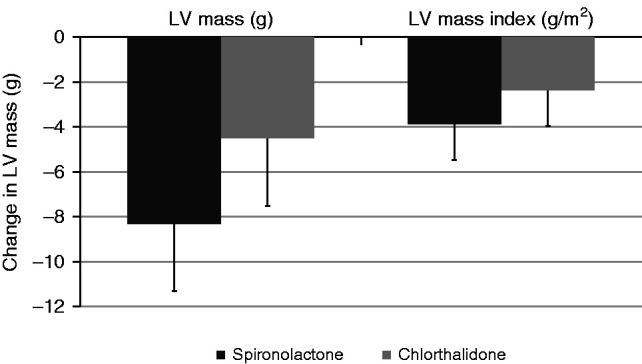

The effects of both drugs on left ventricular mass are shown in Figure 2 and Table 3. Both spironolactone and chlorthalidone reduced left ventricular mass at week 40 (estimated marginal mean −8.3 g, 95% CI, −11.3 to −5.3 versus −4.5 g, 95% CI, −7.5 to −1.5, respectively); however, there was no significant difference between treatments (adjusted mean difference −3.8 g, 95% CI, −8.1 to 0.5, P=0.08). Sensitivity analyses using multiple imputation on the basis of the 136 patients who had cardiac magnetic resonance studies at baseline (adjusted mean difference −3.8 g, 95% CI, −8.2 to 0.6, P=0.09) and a per-protocol analysis of participants that received full doses of trial medications throughout the study (adjusted mean difference −3.1 g, 95% CI −8.2 to 2.1, P=0.20) gave similar results. There was also no difference in left ventricular mass index (adjusted mean difference −1.5 g/m2, 95% CI −3.8 to 0.7, P=0.20).

Figure 2.

Change in left ventricular mass and left ventricular mass index in patients treated with spironolactone and chlorthalidone. On intention-to-treat analysis, there was no significant difference in either drug for change in left ventricular mass (P=0.08) or left ventricular mass indexed to BSA (P=0.19) using a linear regression model adjusted for minimization variables and baseline left ventricular mass. LV, left ventricular.

Table 3.

Treatment effects on outcome measures

| Spironolactone | Chlorthalidone | Adjusted Effect Difference (95% Confidence Interval) | P Value | |||

| Outcome | Week 0 | Week 40 | Week 0 | Week 40 | ||

| Primary outcome variable, n (%) | ||||||

| Left ventricular mass (g) | 131 (28) | 124 (24) | 124 (33) | 122 (37) | −3.8 (−8.1 to 0.5) | 0.08 |

| Change in LV mass | — | −9 (11) | — | −4 (12) | ||

| Left ventricular mass index (g/m2) | 66 (12) | 62 (11) | 64 (14) | 63 (15) | −1.5 (−3.8 to 0.7) | 0.2 |

| Change in LV mass index | — | −4 (6) | — | −2 (7) | ||

| Secondary outcome variables, n (%) | ||||||

| cfPWV (m/s) | 7.4 (1.8) | 7.3 (1.9) | 7.6 (2.2) | 7.50 (2.0) | 0.04 (−0.4 to 0.5) | 0.9 |

| Change in cfPWV | — | 0.02 (1.3) | — | −0.16 (1.5) | ||

| Serum potassium (mEq/L) | 4.4 (0.4) | 4.6 (0.4) | 4.5 (0.3) | 4.2 (0.4) | 0.45 (0.32 to 0.58) | <0.01 |

| Change in serum potassium | — | 0.2 (0.5) | — | −0.3 (0.4) | ||

| Office systolic BP (mm Hg) | 134 (11) | 124 (15) | 136 (14) | 127 (14) | −3 (−7 to 2) | 0.3 |

| Change in systolic BP | — | −10 (15) | — | −9 (16) | ||

| Office diastolic BP (mm Hg) | 82 (8) | 76 (11) | 81 (10) | 78 (8) | −2 (−5 to 0) | 0.1 |

| Change in diastolic BP | — | −6 (9) | — | −3 (10) | ||

| Left ventricular function (strain %) | −15.9 (2.1) | −15.8 (2.5) | −15.6 (2.7) | −15.4 (2.5) | 0.05 (−0.9 to 1.0) | 0.9 |

| Change in strain | — | −0.1 (2.3) | — | −0.2 (2.6) | ||

| eGFR, ml/min/1.73 m2 | 52 (16) | 50 (17) | 57 (15) | 53 (17) | 2 (−1 to 4) | 0.3 |

| Change in eGFR, ml/min/1.73 m2 | — | −2 (8) | — | −5 (8) | ||

| Exploratory outcomes, n (%) | ||||||

| AIx @75 (%) | 23.3 (11.3) | 24.0 (11.2) | 25.8 (10.8) | 23.5 (11.6) | 1.9 (−0.8 to 4.7) | 0.2 |

| 24 h central systolic BP (mm Hg)a | 116 (9) | 111 (11) | 117 (13) | 110 (12) | 2 (−2 to 6) | 0.3 |

| 24 h central diastolic BP (mm Hg)a | 80 (8) | 77 (9) | 81 (10) | 76 (9) | 1 (−1 to 4) | 0.3 |

| 24 h peripheral systolic BP (mm Hg)a | 127 (11) | 122 (13) | 128 (13) | 121 (14) | 2 (−2 to 6) | 0.3 |

| 24 h peripheral diastolic BP (mm Hg)a | 79 (8) | 75 (9) | 80 (9) | 75 (8) | 1 (−1 to 4) | 0.3 |

| UACR (mg/mmol)b | 6 (1–39) | 5 (2–18) | 5 (2–49) | 2 (1–17) | 2 (1 to 3)b | 0.05 |

| LVEF (%) | 74 (6) | 74 (7) | 73 (6) | 72 (7) | 0 (−2 to 2) | 0.7 |

| NTpro BNP (ng/L)b | 74 (41–161) | 78 (38–171) | 114 (39–189) | 66 (31–162) | 1.1 (0.9 to 1.4)b | 0.2 |

Values are mean (SD) for parametric data otherwise median and (interquartile range). Significance P<0.05; chlorthalidone is the reference group. LV, left ventricular; cfPWV, carotid-femoral pulse wave analysis; AIx @75, augmentation index corrected for a heart rate of 75 beats per minute; UACR, urinary albumin-creatinine ratio; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; NTpro BNP, N-terminal pro b-type natriuretic peptide.

BP values given are derived from 24 h ambulatory BP monitoring.

Data were logged before analysis then exponentiated, so the adjusted effect size for these outcomes is the ratio of geometric means.

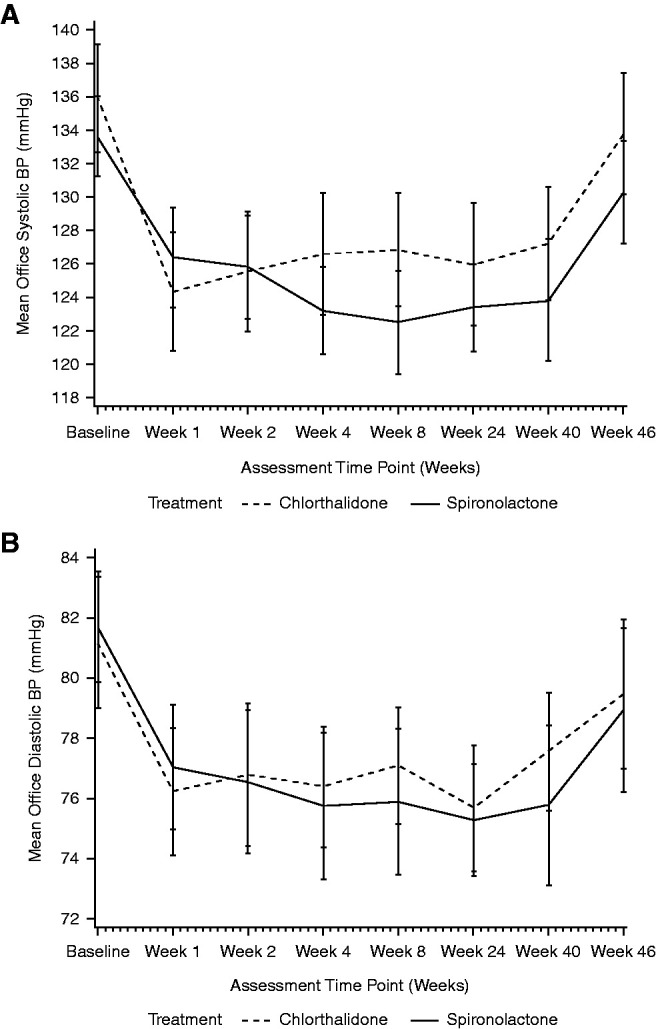

Secondary Outcomes: BP

Both drugs reduced office and 24-hour ambulatory BPs over the treatment period, with no significant differences between treatment groups; no changes in treatment were advised by the BP Monitoring Committee (Figure 3, A and B, Table 3). For office systolic BP at week 40, the estimated marginal means for spironolactone and chlorthalidone were −11 mm Hg (95% CI, −14 to −8) versus −8 mm Hg (95% CI, −12 to −5) respectively, adjusted mean difference −3 mm Hg (95% CI, −7 to 2, P=0.30). For office diastolic BP at week 40, the estimated marginal means were −6 mm Hg (95% CI, −8 to −4) versus −3 mm Hg (95% CI, −5 to −1), respectively, adjusted mean difference −2 mm Hg (95% CI, −5 to 0, P=0.10). Repeated measures analysis also revealed no significant differences between the treatment arms. Mean 24-hour ambulatory BPs also fell with each drug and were not significantly different between treatments at week 40; adjusted mean difference 2 mm Hg (95% CI, −2 to 6, P=0.30) for systolic peripheral BP and 1 mm Hg (95% CI, −1 to 4, P=0.30) for diastolic peripheral BP (Table 3).

Figure 3.

Changes in office systolic and diastolic BP over follow-up. Change in systolic BP (A) and diastolic BP (B) associated with spironolactone (solid line) and chlorthalidone (dashed line) from initiation to end of treatment at week 40, followed by reassessment 4 weeks after cessation of the trial drug. Data are mean and 95% confidence interval.

Other Secondary Outcome Measures

There was no significant difference between treatment arms in cfPWV, augmentation index corrected for a heart rate of 75 beats per minute, left ventricular volumes, ejection fraction, urinary albumin-creatinine ratio, and N-terminal pro–B-type natriuretic peptide (Table 3).

BP Reduction and Changes in Left Ventricular Mass

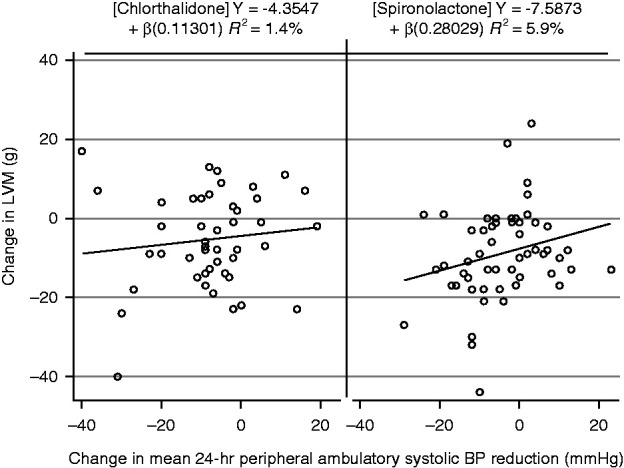

This exploratory analysis suggested a possible graded relationship between changes in left ventricular mass from baseline versus changes in 24-hour ambulatory systolic BP (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Change in left ventricular mass and 24-hour ambulatory systolic BP after 40 weeks of treatment with spironolactone or chlorthalidone.

Adverse Events and Side Effects

In accordance with the protocol, medication was reduced to half-dose in 12 participants in the spironolactone arm due to moderate hyperkalemia (six participants), decline in eGFR (four), hyponatremia (one), and symptomatic hypotension (one). In the chlorthalidone group, medication was reduced to half-dose in four participants due to a decline in eGFR (two), symptomatic hypotension (one), and malaise (one). Permanent discontinuation of the study drug was required in 11 participants taking spironolactone: patient-reported side effects (eight), decline in eGFR (one), decline in eGFR and moderate hyperkalemia (one), and hyponatremia (one), and 19 participants taking chlorthalidone: patient-reported side effects (ten), decline in eGFR (eight), and hyponatremia (one).

Hyperkalemia occurred in 12 participants on spironolactone compared with two on chlorthalidone; mild hyperkalemia occurred in ten on spironolactone and two on chlorthalidone; and moderate hyperkalemia occurred in one participant on spironolactone (information missing for one participant). There were no episodes of severe hyperkalemia. Over 70% of the episodes of hyperkalemia occurred within 4 weeks of starting medication. The mean change in serum potassium at week 40 was +0.2±0.5 mEq/L with spironolactone and −0.3±0.4 mEq/L with chlorthalidone, adjusted mean difference 0.5 mEq/L (95% CI, 0.3 to 0.6, P<0.001). A severe decline in kidney function (>30% fall in eGFR) requiring discontinuation from trial therapy occurred in two participants on spironolactone and eight on chlorthalidone. There were no significant differences between the treatment arms for eGFR at week 40, adjusted mean difference 2 ml/min per 1.73 m2 (95% CI, 1.1 to 4.3, P=0.30). There were no patients with symptomatic hypotension requiring discontinuation of treatment in either treatment arm.

Discussion

In participants with early-stage, nondiabetic CKD, left ventricular mass and BP were both reduced with spironolactone and chlorthalidone, with no statistically significant difference between groups at the end of the 40-week treatment period. There were also no statistically significant differences between spironolactone and chlorthalidone on measures of left ventricular geometry or function, arterial stiffness, urinary albumin-creatinine ratio, or N-terminal pro–B-type natriuretic peptide. The hypothesis that spironolactone would be superior to chlorthalidone in reducing left ventricular mass due to its nonhemodynamic, mineralocorticoid antagonist–specific mediated antihypertrophic and inflammatory effects was not confirmed, despite the use of modern cardiac magnetic resonance imaging techniques capable of measuring left ventricular mass to an accuracy of <10 g. Both treatments were well tolerated, with a low incidence of major adverse effects.

In experimental work, spironolactone effectively inhibits multiple deleterious actions of aldosterone, including vascular, myocardial, endothelial, proinflammatory, fibrotic, and hypertrophic effects (6,14). It is also highly effective in reducing mortality and hospitalization for populations with heart failure due to reduced ejection fraction (<35%) and after acute myocardial infarction (15,16). In CRIB 2, spironolactone reduced left ventricular mass over 40 weeks by a mean of 14 g in patients with CKD stage 2–3, compared with no change with inactive placebo (7). Similar reductions in left ventricular mass with spironolactone were also reported in the 4E study, in which the use of eplerenone and enalapril produced additive reductions in left ventricular mass in hypertensive participants with left ventricular hypertrophy (17). These effects were similar to those of this study. Our new finding, however, that chlorthalidone, which activates rather than inhibits the renin angiotensin system, also reduces left ventricular mass to an extent not different to spironolactone, suggests these actions are a result of BP reduction rather than other effects of mineralocorticoid antagonism. This conclusion is strengthened by the association between the changes in systolic pressure and left ventricular mass. The study illustrates the importance of comparing the effects of mineralocorticoid receptor blockers with active BP-lowering control drugs, a design feature yet to be used in important trials of new nonsteroidal mineralocorticoid receptor blockers (18).

Change in left ventricular mass was chosen as the primary outcome for this study because of the adverse prognostic importance of left ventricular hypertrophy in hypertension and CKD irrespective of BP (19–22), the nondichotomous graded relationship between left ventricular mass and prognosis in essential hypertension (23), and the positive prognostic value of a reduction in left ventricular mass in essential hypertension, independent of baseline left ventricular mass and degree of BP reduction (24,25). In the Framingham study, left ventricular mass was second only to age in its ability to predict cardiovascular morbidity and mortality (19). Although a meta-analysis has questioned the validity of using left ventricular mass as a surrogate for total mortality in CKD, many of the studies used the less accurate technique of echocardiography for measurement of left ventricular mass and few were large enough, or of adequate duration, to ascertain relevant changes (26). In a 5-year study in kidney failure, participants classified as “responders” saw each 1 g reduction in left ventricular mass associated with a 1% fall in cardiovascular mortality (27). There are no similar studies in early-stage CKD, despite its much higher prevalence and presence of abnormalities of left ventricular mass, myocardial fibrosis, and cardiac function (28–30). Our study shows that left ventricular mass in early-stage CKD is responsive to BP reduction irrespective of the mode of action of drug therapy, even when starting BP is controlled at Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes target and left ventricular mass is not in a range categorized as hypertrophy (31).

The possible relationship between BP reduction and fall in left ventricular mass provides support for a primarily BP-mediated mode of action. The findings extend those of Simpson et al. (32) who showed that in a group of participants with left ventricular hypertrophy, left ventricular mass was reduced by BP lowering, even when starting BP was in the normotensive range.

The BP-lowering effects of both spironolactone and chlorthalidone on top of baseline treatment with an ACE inhibitor or ARB in this group of patients with CKD are of importance in their own right. Neither agent is in common use in CKD—spironolactone because of concerns about effects on serum potassium and kidney function and chlorthalidone principally because of concerns about efficacy of thiazide-like drugs in CKD. Our data suggest that both agents are similarly effective in lowering BP and well tolerated in participants with CKD. The appropriate target for BP in patients with CKD remains uncertain. Evidence for the positive effects of lowering BP on the progression of kidney disease remains inconclusive, whereas the effects on cardiovascular end points in CKD are probably similar to those shown in the general population (33). Subgroup analysis of Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial (SPRINT) participants with CKD at baseline showed no effect modification by CKD status, with a substantial reduction in the composite cardiovascular outcome of cardiovascular mortality and deaths (34). In a meta-analysis of the effects of intensive BP lowering on mortality in >15,000 patients with predominantly later-stage (3–5) CKD, intensive treatments with a mean reduction in systolic BP of 16 mm Hg reduced all-cause mortality by 14% compared with control groups on standard therapy (35). Our finding that intensive BP reduction reduces left ventricular mass in participants with CKD provides a plausible pathophysiological mechanism for this result.

With respect to safety and tolerability, although the number of events was small, hyperkalemia was more common with spironolactone, whereas clinically significant reductions in kidney function were more common with chlorthalidone. The effect of chlorthalidone on office systolic BP in this study was similar to that observed in participants with CKD treated with chlorthalidone in the Antihypertensive and Lipid-lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT) in whom systolic BP was reduced by approximately 11 mm Hg over a 6-year treatment period (36). Several recent meta-analyses of the effects of mineralocorticoid receptor blockers in stage 3–4 CKD have shown similar reductions in BP to those seen in this study with spironolactone (37–39). In addition, these studies suggest possible beneficial effects on kidney function with consistent reductions in proteinuria, although there were small excess risks of hyperkalemia (38–40). Thus, although spironolactone has not shown specific effects on the end points of our study, it remains an effective treatment option for patients with early-stage CKD that reduces BP, left ventricular mass, and proteinuria and appears safe providing the starting potassium is not elevated and potassium is monitored during the weeks after its introduction. Problems with hyperkalemia in CKD may be circumvented by coprescription of potassium-binding agents (41).

There are limitations to our study. Recruitment was slower and more challenging than anticipated. This required us to change to a single primary end point of left ventricular mass to ensure the study was adequately powered to detect a clinically significant outcome. The 119 participants who completed paired cardiac magnetic resonance studies provided 83% power to detect a 7 g difference in left ventricular mass with an α of 0.05. As some of our patients had dose reductions, the study might be regarded as underpowered. We were concerned about our ability to detect small changes in left ventricular mass, even with the use of cardiac magnetic resonance and it is reassuring that recently published data have confirmed the precision of cardiac magnetic resonance in the measurement of left ventricular mass (12). Although the study was not powered to detect changes in left ventricular mass smaller than 7 g, changes of this magnitude are of doubtful clinical significance and below the limits of accuracy of the measurement technique. We acknowledge that our results do not definitively exclude the possibility that spironolactone is superior to chlortalidone in the reduction of left ventricular mass at an equal BP; a larger study would be required to provide conclusive data. Patients with diabetes and previous serum potassium >5 mmol/L were excluded on safety grounds, meaning the low rates of hyperkalemia observed with spironolactone may not be generalizable to all patients with early-stage CKD. We acknowledge that discontinuation of treatment and half-dose treatment in both arms could have contributed to missing the treatment effect, although a per-protocol analysis of all patients with no change to treatment schedule gave similar results for the primary analyses.

In conclusion, in patients with stable nondiabetic CKD stage 2 and 3 with controlled BP, on treatment with ACE inhibitors or ARBs, we found no evidence that spironolactone was superior to chlorthalidone in its effects on left ventricular mass. Although previous experimental studies have shown spironolactone to mediate a wide variety of potentially beneficial antiproliferative and antifibrotic effects on cardiac and vascular tissues, we could not demonstrate evidence for such pleiotropic effects over and above BP reduction. Both treatments effectively reduced BP to levels below present CKD guideline target recommendations and had a low level of adverse effects. Although the specific class of antihypertensive may not be critical, intensively reducing systolic BP to further reduce left ventricular mass in CKD may be associated with long-term prognostic benefit and requires further investigation.

Disclosures

A.S. Herrey reports serving as a Board Member of the UK Maternal Cardiac Society. D.C. Wheeler reports consultancy agreements with Astellas, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Gilead, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Merck Sharp and Dohme, Mundipharma, Napp, Tricida, Vifor Fesenius, and Zydus; reports receiving honoraria from Amgen, Astellas, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelhiem, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Merck Sharp and Dohme, Mundipharma, Napp, Pharmacosmos, Reata, and Vifor Fresenius; reports serving as a scientific advisor or member of AstraZeneca; reports speakers bureau for Amgen, AstraZeneca, Astellas, Janssen, Merck Sharp and Dohme, Mundipharma, Napp, and Vifor Fresenius; and reports serving as Honorary Professorial Fellow, George Institute for Global Health. D.J. Webb reports employment with UK Medicines & Healthcare products Regulatory Agency and serving on the Council of UK Academy of Medical Sciences, Executive Committee of International Union of Basic & Clinical Pharmacology, and as Non-Executive Director of UK Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. I.M. Macintyre reports consultancy agreements with, and receiving honoraria from, AstraZeneca. I. Wilkinson reports receiving research funding from AstraZeneca and GlaxoSmithKline and serving on the Editorial Board of Hypertension. P.J. Greasley reports employment with, and ownership interest in, AstraZeneca. N. Dhaun reports consultancy agreements with, and serving as a scientific advisor or member of, Travere and reports receiving research funding from Pfizer. R.P. Steeds reports consultancy agreements with Freeline Therapeutics; reports receiving research funding from Sanofi Genzyme and Takeda Shire; and reports receiving honoraria from Amicus and Janssen. T.F. Hiemstra reports employment with, and an ownership interest in, GlaxoSmithKline, Kodika Corporation, and Ovibio Corporation; reports receiving support from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Cambridge Biomedical Research Centre; and reports serving on the Scientific Advisory Boards of Kodika Corporation and Ovibio Corporation. All remaining authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding

This work was supported by the British Heart Foundation (SP/12/8/29620).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was carried out in Birmingham at the NIHR/Wellcome Trust Birmingham Clinical Research Facility, NIHR Cambridge BRC, and the University of Edinburgh Clinical Research Center. T.F. Hiemstra is supported by the NIHR Cambridge BRC. A.M. Price is supported by a British Heart Foundation Clinical Research Fellowship (FS/13/30/29994, 16/73/32314). The views are those of the authors and not of the National Health Service, the NIHR or the Department of Health. The authors wish to acknowledge the following individuals for their contribution: Dr. Neil Chapman (Trial Steering Committee Chair) (London UK), Dr. Louise Hiller (Warwick UK), Dr. Fergus Caskey (Bristol UK), and Dr. Keira Markey (Birmingham UK) from the Trial Steering Committee; Prof. Tom MacDonald (Dundee UK), Prof. Ian Ford (Glasgow UK), Prof. Allan Struthers (Dundee UK) from the BP Monitoring Committee; and Emma Hayes (Birmingham Clinical Trial Unit); Mr. Nicholas Hilken, Mr. Andrew Howman, Mr. Rajnikant Mehta, Hannah Watson, Mr. Adrian Wilcockson; and Mrs. Mary Dutton, Mr. Ceclilio Andujar, Mrs. Elizabeth Dwenger, Ms. Katie Kirkham, Jane Smith, Sarah Stevens, Mr. Norman Madeja, Eleanor Damian, Toluleyi Sobande, Vashist Deelchand, Rachel Davies, Aarti Nandani, Elizabeth Woodford from Research Nurse/Pharmacy Support; and Dr. Ben Caplain (subinvestigator).

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

Data Sharing Statement

Individual deidentified participant data (clinical data acquired in the trial) and related study documents (study protocol, statistical analysis plan) will be available for researchers requesting data from the Birmingham Clinical Trials Unit.

Supplemental Material

This article contains the following supplemental material online at http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2215/CJN.01930221/-/DCSupplemental.

Supplemental Appendix. Statistical analyses.

References

- 1.Sarnak MJ, Levey AS, Schoolwerth AC, Coresh J, Culleton B, Hamm LL, McCullough PA, Kasiske BL, Kelepouris E, Klag MJ, Parfrey P, Pfeffer M, Raij L, Spinosa DJ, Wilson PW; American Heart Association Councils on Kidney in Cardiovascular Disease, High Blood Pressure Research, Clinical Cardiology, and Epidemiology and Prevention : Kidney disease as a risk factor for development of cardiovascular disease: A statement from the American Heart Association Councils on Kidney in Cardiovascular Disease, High Blood Pressure Research, Clinical Cardiology, and Epidemiology and Prevention. Hypertension 42: 1050–1065, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thomas B, Matsushita K, Abate KH, Al-Aly Z, Ärnlöv J, Asayama K, Atkins R, Badawi A, Ballew SH, Banerjee A, Barregård L, Barrett-Connor E, Basu S, Bello AK, Bensenor I, Bergstrom J, Bikbov B, Blosser C, Brenner H, Carrero JJ, Chadban S, Cirillo M, Cortinovis M, Courville K, Dandona L, Dandona R, Estep K, Fernandes J, Fischer F, Fox C, Gansevoort RT, Gona PN, Gutierrez OM, Hamidi S, Hanson SW, Himmelfarb J, Jassal SK, Jee SH, Jha V, Jimenez-Corona A, Jonas JB, Kengne AP, Khader Y, Khang YH, Kim YJ, Klein B, Klein R, Kokubo Y, Kolte D, Lee K, Levey AS, Li Y, Lotufo P, El Razek HMA, Mendoza W, Metoki H, Mok Y, Muraki I, Muntner PM, Noda H, Ohkubo T, Ortiz A, Perico N, Polkinghorne K, Al-Radaddi R, Remuzzi G, Roth G, Rothenbacher D, Satoh M, Saum KU, Sawhney M, Schöttker B, Shankar A, Shlipak M, Silva DAS, Toyoshima H, Ukwaja K, Umesawa M, Vollset SE, Warnock DG, Werdecker A, Yamagishi K, Yano Y, Yonemoto N, Zaki MES, Naghavi M, Forouzanfar MH, Murray CJL, Coresh J, Vos T; Global Burden of Disease 2013 GFR Collaborators; CKD Prognosis Consortium; Global Burden of Disease Genitourinary Expert Group : Global cardiovascular and renal outcomes of reduced GFR. J Am Soc Nephrol 28: 2167–2179, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gansevoort RT, Correa-Rotter R, Hemmelgarn BR, Jafar TH, Heerspink HJ, Mann JF, Matsushita K, Wen CP: Chronic kidney disease and cardiovascular risk: Epidemiology, mechanisms, and prevention. Lancet 382: 339–352, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Edwards NC, Moody WE, Chue CD, Ferro CJ, Townend JN, Steeds RP: Defining the natural history of uremic cardiomyopathy in chronic kidney disease: The role of cardiovascular magnetic resonance. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 7: 703–714, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bomback AS, Klemmer PJ: The incidence and implications of aldosterone breakthrough. Nat Clin Pract Nephrol 3: 486–492, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown NJ: Aldosterone and vascular inflammation. Hypertension 51: 161–167, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Edwards NC, Steeds RP, Stewart PM, Ferro CJ, Townend JN: Effect of spironolactone on left ventricular mass and aortic stiffness in early-stage chronic kidney disease: A randomized controlled trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 54: 505–512, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hayer MK, Edwards NC, Slinn G, Moody WE, Steeds RP, Ferro CJ, Price AM, Andujar C, Dutton M, Webster R, Webb DJ, Semple S, MacIntyre I, Melville V, Wilkinson IB, Hiemstra TF, Wheeler DC, Herrey A, Grant M, Mehta S, Ives N, Townend JN: A randomized, multicenter, open-label, blinded end point trial comparing the effects of spironolactone to chlorthalidone on left ventricular mass in patients with early-stage chronic kidney disease: Rationale and design of the SPIRO-CKD trial. Am Heart J 191: 37–46, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kawel-Boehm N, Maceira A, Valsangiacomo-Buechel ER, Vogel-Claussen J, Turkbey EB, Williams R, Plein S, Tee M, Eng J, Bluemke DA: Normal values for cardiovascular magnetic resonance in adults and children. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 17: 29, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wilkinson IB, Fuchs SA, Jansen IM, Spratt JC, Murray GD, Cockcroft JR, Webb DJ: Reproducibility of pulse wave velocity and augmentation index measured by pulse wave analysis. J Hypertens 16: 2079–2084, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Savage MT, Ferro CJ, Pinder SJ, Tomson CR: Reproducibility of derived central arterial waveforms in patients with chronic renal failure. Clin Sci (Lond) 103: 59–65, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bhuva AN, Bai W, Lau C, Davies RH, Ye Y, Bulluck H, McAlindon E, Culotta V, Swoboda PP, Captur G, Treibel TA, Augusto JB, Knott KD, Seraphim A, Cole GD, Petersen SE, Edwards NC, Greenwood JP, Bucciarelli-Ducci C, Hughes AD, Rueckert D, Moon JC, Manisty CH: A multicenter, scan-rescan, human and machine learning CMR study to test generalizability and precision in imaging biomarker analysis. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 12: e009214, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moody WE, Edwards NC, Chue CD, Taylor RJ, Ferro CJ, Townend JN, Steeds RP: Variability in cardiac MR measurement of left ventricular ejection fraction, volumes and mass in healthy adults: Defining a significant change at 1 year. Br J Radiol 88: 20140831, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Briet M, Schiffrin EL: Aldosterone: Effects on the kidney and cardiovascular system. Nat Rev Nephrol 6: 261–273, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pitt B, White H, Nicolau J, Martinez F, Gheorghiade M, Aschermann M, van Veldhuisen DJ, Zannad F, Krum H, Mukherjee R, Vincent J; EPHESUS Investigators : Eplerenone reduces mortality 30 days after randomization following acute myocardial infarction in patients with left ventricular systolic dysfunction and heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 46: 425–431, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pitt B, Zannad F, Remme WJ, Cody R, Castaigne A, Perez A, Palensky J, Wittes J; Randomized Aldactone Evaluation Study Investigators : The effect of spironolactone on morbidity and mortality in patients with severe heart failure. N Engl J Med 341: 709–717, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pitt B, Reichek N, Willenbrock R, Zannad F, Phillips RA, Roniker B, Kleiman J, Krause S, Burns D, Williams GH: Effects of eplerenone, enalapril, and eplerenone/enalapril in patients with essential hypertension and left ventricular hypertrophy: The 4E-left ventricular hypertrophy study. Circulation 108: 1831–1838, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ruilope LM, Agarwal R, Anker SD, Bakris GL, Filippatos G, Nowack C, Kolkhof P, Joseph A, Mentenich N, Pitt B; FIGARO-DKD study investigators : Design and baseline characteristics of the finerenone in reducing cardiovascular mortality and morbidity in diabetic kidney disease trial. Am J Nephrol 50: 345–356, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Levy D, Garrison RJ, Savage DD, Kannel WB, Castelli WP: Prognostic implications of echocardiographically determined left ventricular mass in the Framingham Heart Study. N Engl J Med 322: 1561–1566, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vakili BA, Okin PM, Devereux RB: Prognostic implications of left ventricular hypertrophy. Am Heart J 141: 334–341, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Foley RN, Parfrey PS, Harnett JD, Kent GM, Murray DC, Barré PE: The prognostic importance of left ventricular geometry in uremic cardiomyopathy. J Am Soc Nephrol 5: 2024–2031, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zoccali C, Benedetto FA, Mallamaci F, Tripepi G, Giacone G, Stancanelli B, Cataliotti A, Malatino LS: Left ventricular mass monitoring in the follow-up of dialysis patients: Prognostic value of left ventricular hypertrophy progression. Kidney Int 65: 1492–1498, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schillaci G, Verdecchia P, Porcellati C, Cuccurullo O, Cosco C, Perticone F: Continuous relation between left ventricular mass and cardiovascular risk in essential hypertension. Hypertension 35: 580–586, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Devereux RB, Wachtell K, Gerdts E, Boman K, Nieminen MS, Papademetriou V, Rokkedal J, Harris K, Aurup P, Dahlöf B: Prognostic significance of left ventricular mass change during treatment of hypertension. JAMA 292: 2350–2356, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Verdecchia P, Schillaci G, Borgioni C, Ciucci A, Gattobigio R, Zampi I, Reboldi G, Porcellati C: Prognostic significance of serial changes in left ventricular mass in essential hypertension. Circulation 97: 48–54, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Badve SV, Palmer SC, Strippoli GFM, Roberts MA, Teixeira-Pinto A, Boudville N, Cass A, Hawley CM, Hiremath SS, Pascoe EM, Perkovic V, Whalley GA, Craig JC, Johnson DW: The validity of left ventricular mass as a surrogate end point for all-cause and cardiovascular mortality outcomes in people with CKD: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Kidney Dis 68: 554–563, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.London GM, Pannier B, Guerin AP, Blacher J, Marchais SJ, Darne B, Metivier F, Adda H, Safar ME: Alterations of left ventricular hypertrophy in and survival of patients receiving hemodialysis: Follow-up of an interventional study. J Am Soc Nephrol 12: 2759–2767, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Edwards NC, Hirth A, Ferro CJ, Townend JN, Steeds RP: Subclinical abnormalities of left ventricular myocardial deformation in early-stage chronic kidney disease: The precursor of uremic cardiomyopathy? J Am Soc Echocardiogr 21: 1293–1298, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Edwards NC, Moody WE, Yuan M, Hayer MK, Ferro CJ, Townend JN, Steeds RP: Diffuse interstitial fibrosis and myocardial dysfunction in early chronic kidney disease. Am J Cardiol 115: 1311–1317, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Park M, Hsu CY, Li Y, Mishra RK, Keane M, Rosas SE, Dries D, Xie D, Chen J, He J, Anderson A, Go AS, Shlipak MG; Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC) Study Group : Associations between kidney function and subclinical cardiac abnormalities in CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol 23: 1725–1734, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD Work Group. KDIGO 2012 Clinical Practice Guideline for the Evaluation and Management of Chronic Kidney Disease. Available at: https://kdigo.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/KDIGO_2012_CKD_GL.pdf. Accessed January 7, 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Simpson HJ, Gandy SJ, Houston JG, Rajendra NS, Davies JI, Struthers AD: Left ventricular hypertrophy: Reduction of blood pressure already in the normal range further regresses left ventricular mass. Heart 96: 148–152, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moody WE, Ferro CJ, Townend JN: SPRINTing towards trials of blood pressure reduction to reduce CKD progression? Eur Heart J Qual Care Clin Outcomes 2: 229–230, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cheung AK, Rahman M, Reboussin DM, Craven TE, Greene T, Kimmel PL, Cushman WC, Hawfield AT, Johnson KC, Lewis CE, Oparil S, Rocco MV, Sink KM, Whelton PK, Wright JT Jr, Basile J, Beddhu S, Bhatt U, Chang TI, Chertow GM, Chonchol M, Freedman BI, Haley W, Ix JH, Katz LA, Killeen AA, Papademetriou V, Ricardo AC, Servilla K, Wall B, Wolfgram D, Yee J; SPRINT Research Group : Effects of intensive BP control in CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol 28: 2812–2823, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Malhotra R, Nguyen HA, Benavente O, Mete M, Howard BV, Mant J, Odden MC, Peralta CA, Cheung AK, Nadkarni GN, Coleman RL, Holman RR, Zanchetti A, Peters R, Beckett N, Staessen JA, Ix JH: Association between more intensive vs less intensive blood pressure lowering and risk of mortality in chronic kidney disease stages 3 to 5: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med 177: 1498–1505, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rahman M, Pressel S, Davis BR, Nwachuku C, Wright JT Jr, Whelton PK, Barzilay J, Batuman V, Eckfeldt JH, Farber M, Henriquez M, Kopyt N, Louis GT, Saklayen M, Stanford C, Walworth C, Ward H, Wiegmann T: Renal outcomes in high-risk hypertensive patients treated with an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or a calcium channel blocker vs a diuretic: A report from the Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT). Arch Intern Med 165: 936–946, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bolignano D, Palmer SC, Navaneethan SD, Strippoli GF: Aldosterone antagonists for preventing the progression of chronic kidney disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev Apr 29: CD007004, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Currie G, Taylor AH, Fujita T, Ohtsu H, Lindhardt M, Rossing P, Boesby L, Edwards NC, Ferro CJ, Townend JN, van den Meiracker AH, Saklayen MG, Oveisi S, Jardine AG, Delles C, Preiss DJ, Mark PB: Effect of mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists on proteinuria and progression of chronic kidney disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Nephrol 17: 127, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ng KP, Arnold J, Sharif A, Gill P, Townend JN, Ferro CJ: Cardiovascular actions of mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists in patients with chronic kidney disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. J Renin Angiotensin Aldosterone Syst 16: 599–613, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yang CT, Kor CT, Hsieh YP: Long-term effects of spironolactone on kidney function and hyperkalemia-associated hospitalization in patients with chronic kidney disease. J Clin Med 7: E459, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Agarwal R, Rossignol P, Romero A, Garza D, Mayo MR, Warren S, Ma J, White WB, Williams B: Patiromer versus placebo to enable spironolactone use in patients with resistant hypertension and chronic kidney disease (AMBER): A phase 2, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 394: 1540–1550, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.