Abstract

Raccoon dogs have successfully invaded Europe, including Denmark. Raccoon dogs are potential vectors and reservoir hosts of several zoonotic pathogens and thus have the potential for posing a threat to both human and animal health. This study includes analysis of four zoonotic parasites, 16 tick-borne pathogens and two pathogen groups from 292 raccoon dogs collected from January 2018 to December 2018. The raccoon dogs were received as a part of the Danish national wildlife surveillance program and were hunted, found dead or road killed. The raccoon dogs were screened for Alaria alata and Echinococcus multilocularis eggs in faeces by microscopy and PCR, respectively, Trichinella spp. larvae in muscles by digestion, antibodies against Toxoplasma gondii by ELISA and screening of ticks for pathogens by fluidigm real-time PCR.

All raccoon dogs tested negative for E. multilocularis and Trichinella spp., while 32.9% excreted A. alata eggs and 42.7% were T. gondii sero-positive. Five tick-borne pathogens were identified in ticks collected from 15 raccoon dogs, namely Anaplasma phagocytophilum (20.0%), Babesia venatorum (6.7%), Borrelia miyamotoi (6.7%), Neoehrlichia mikurensis (6.7%) and Rickettsia helvetica (60.0%).

We identified raccoon dogs from Denmark as an important reservoir of T. gondii and A. alata infection to other hosts, including humans, while raccoon dogs appear as a negligible reservoir of E. multilocularis and Trichinella spp. infections. Our results suggest that raccoon dogs may be a reservoir of A. phagocytophilum.

Keywords: Raccoon dog, Nyctereutes procyonoides, Endoparasites, Tick-borne pathogens, Reservoir, Zoonoses

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

We investigated the occurrence of zoonotic endoparasites.

-

•

We investigated the occurrence of pathogens in ticks attached to raccoon dogs.

-

•

We found 32.9% excreted A. alata eggs and 42.7% were T. gondii sero-positive.

-

•

We found five tick-borne pathogens in ticks from Danish raccoon dogs.

1. Introduction

The raccoon dog (Nyctereutes procyonoides) is considered an invasive species in Denmark. Since its arrival in 1980, the population has increased continuously and at present comprises 2000–3000 individuals (The Environmental Protection Agency, n.d.). Raccoon dogs are well-known hosts of several zoonotic and pathogenic infections (Al-sabi et al., 2013; Kauhala and Kowalczyk, 2011; Malakauskas et al., 2007; Wodecka et al., 2016) posing a potential risk to human and animal health. However, neither tick-borne pathogens from raccoon dogs nor the prevalence of the zoonotic parasites Toxoplasma gondii and Trichinella spp. has previously been identified in raccoon dogs from Denmark, while Echinococcus multilocularis and Alaria alata has been identified several years ago (Al-sabi et al., 2013; Petersen et al., 2018).

Echinococcus multilocularis infections in humans are rare. Nonetheless, the clinical implications are critical and cause considerable public health concerns (Torgerson et al., 2008). Humans acquire the infection by ingesting E. multilocularis eggs, excreted by canine hosts, usually from contaminated food or water. Trichinella spp. infection can cause serious illness in humans including death (Darwin Murrell and Pozio, 2011) following consumption of Trichinella spp. infected raw or undercooked meat. Denmark is officially recognized with negligible risk of Trichinella spp. infection in farmed pigs (Danish Veterinary and Food Administration, n.d.), but organic and other outdoor pig production systems are increasing (Denmark Statistics, 2021). Currently, no systematic surveillance of Trichinella spp. occur in Danish wildlife, but previous surveillance projects have demonstrated T. pseudospiralis in a wild mink from the island of Bornholm in 2007 (Data not published), and three cases of Trichinella spp. in red foxes (0.1%) in the mid-1990s (Enemark et al., 2000). Toxoplasma gondii infection can cause toxoplasmosis, and 30–50% of the world's human population are estimated to be infected with T. gondii (Flegr et al., 2014). Most T. gondii infections in immunocompetent humans are asymptomatic or subclinical with minor symptoms (Montoya and Liesenfeld, 2004). However, ocular disease occur occasionally (Holland, 2003), and infection might be a contributing causal factor for developing any psychiatric disorder (Burgdorf et al., 2019). Toxoplasma gondii can also be transmitted to the foetus via the placenta resulting in congenital toxoplasmosis which can cause abortion, neonatal death, or foetal abnormalities (Chaudhry et al., 2014; Fallahi et al., 2018). Human Alaria infections are rare, but infections include clinical signs ranging from low-grade respiratory and cutaneous symptoms (Hedges, 2000) to fatal anaphylactic shock (Möhl et al., 2009). The adult Alaria stage which infects raccoon dogs has little relevance as a pathogen, while the mesocercariae stage found in paratenic host, e.g. wild boars (Sus scrofa), is pathogenic (Möhl et al., 2009). Infected raccoon dogs can act as reservoir for infection in wild boars and further transmission to humans through ingestion of wild boar meat (Möhl et al., 2009; Ozoliņa et al., 2020; Riehn et al., 2012).

Tick-borne diseases are primarily transmitted from one host to another via the tick vector (Estrada-Peña and de la Fuente, 2014) and the host can serve as a reservoir continuously infecting new feeding ticks (Keesing et al., 2012; Ostfeld et al., 2014). The disease-causing pathogens belonging to Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato (s.l.) species complex commonly occur in the northern hemisphere (Kjær et al., 2020b), including species causing Lyme borreliosis in both humans and animals, in particular B. afzelii, B. garinii, B. burgdorferi sensu stricto (s.s.), B. lusitaniae, B. spielmanii, and B. valaisiana (Klitgaard et al., 2019b; Michelet et al., 2014; Skarphédinsson et al., 2007; Vennestrøm et al., 2008; Wilhelmsson et al., 2010). Furthermore, Anaplasma phagocytophilum, species of the genus Babesia (Babesia canis, B. divergens, B. microti, B. venatorum), Bartonella henselae, Borrelia miyamotoi, Coxiella burnetii, Francisella tularensis, Neoehrlichia mikurensis, Rickettsia helvetica, and Tick Borne Encephalitis virus complex (TBEV) have been found in Scandinavia (Fertner et al., 2012; Fomsgaard et al., 2013; Jensen et al., 2017; Kjær et al., 2020a; Lundkvist et al., 2011; Michelet et al., 2014; Quarsten et al., 2017; Stuen et al., 2013; Svensson et al., 2019). Borrelia miyamotoi, R. helvetica and N. mikurensis rarely cause disease in humans in Scandinavia (Frivik et al., 2017; Grankvist et al., 2014; Nilsson et al., 2010; Welinder-Olsson et al., 2010). Anaplasma phagocytophilum and species within the Babesia genus are known disease-causing agents in domestic livestock (Stuen et al., 2013), but can also cause disease in humans (Heyman et al., 2010). For an overview of some of the pathogens found in Denmark and Scandinavia and their zoonotic potential, see Table 1.

Table 1.

A selection of tick-borne pathogens found in Denmark/Scandinavia included in the real-time PCR assay, their zoonotic potential, primary cause of disease in Denmark, as well as their main reservoirs.

| Species | Zoonotic potential | Vector | Main reservoirs | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anaplasma phagocytophilum | Human granulocytic anaplasmosis | I. ricinus | Rodents, wild ruminants, birds | (Heyman et al., 2010; Jaarsma et al., 2019) |

| Babesia canis | None, but causes canine babesiosis | D. reticulatus | Canines | (Jongejan et al., 2015; Øines et al., 2010) |

| Babesia divergens | Human babesiosis | I. ricinus | Bovines | (Heyman et al., 2010; Karlsson and Andersson, 2016) |

| Babesia microti | Rodents | |||

| Babesia venatorum | Cervids | |||

| Bartonella henselae | Cat scratch fever | Cat fleas, I. ricinus | Cats | (Cotté et al., 2008; Dietrich et al., 2010) |

| Borrelia afzelii, B. burgdorferi s. s., | Lyme borreliosis | I. ricinus | Rodents, birds, lizards | (Heyman et al., 2010; Kjelland et al., 2010) |

| B. garinii, B. lusitaniae, | ||||

| B. spielmanii, B. valaisiana | ||||

| Borrelia miyamotoi | Relapsing fever | I. ricinus | Rodents | (Krause et al., 2015; Tobudic et al., 2020) |

| Coxiella burnetii | Q fever | Aerosols from infected animals, I. ricinus, D. reticulatus | Wild and domestic mammals, birds, arthropods | (Špitalská and Kocianová, 2003; Sprong et al., 2012) |

| Francisella tularensis | Tularaemia | Ingestion/aerosols from infected animals, D. reticulatus, deer flies, horse flies, mosquitoes | Rodents, lagomorphs | (Byström et al., 2005; Petersen et al., 2009; Seiwald et al., 2020) |

| Neoehrlichia mikurensis | Neoehrlichiosis | I. ricinus, D. reticulatus | Rodents | (Jahfari et al., 2012; Portillo et al., 2018) |

| Rickettsia helvetica | Tick-borne rickettsiosis | I. ricinus, mites, lice fleas | Ticks, rodents, deer | Sprong et al. (2009) |

Previous studies have revealed infections with A. phagocytophilum, B. henselae, Borrelia spp., and N. mikurensis in raccoon dogs (Han et al., 2017; Härtwig et al., 2014; Hildebrand et al., 2018; Kang et al., 2018; Szewczyk et al., 2019), thus investigating the raccoon dog's potential as a wildlife reservoir of zoonotic diseases is necessary to access the impact of an increasing raccoon dog population on human and animal health. We performed this study to address the raccoon dogs as wildlife reservoirs of tick-borne pathogens and serious zoonotic parasites.

2. Materials and method

2.1. Study animals

We included raccoon dogs submitted for necropsy from January 2018 to December 2018, as a part of the Danish national wildlife surveillance program. The raccoon dogs were hunted or trapped, found dead or road killed. All animals were transported in sealed plastic bags and subsequently stored at −80 °C for min. four days prior to necropsy to inactivate potential zoonotic parasites. At necropsy, faecal sample from rectum, a muscle sample from the thighs, the heart and ticks were collected and stored at −20 °C until further examination. Data of origin and sex of the raccoon dog were noted. Occasionally, samples were unsuitable for examination due to traumatic injury, predation or decomposition and were excluded.

2.2. Screening for parasites

2.2.1. Alaria alata

Alaria alata eggs were identified in individual faeces samples by sedimentation. Briefly, 4 g faeces were diluted in 36 ml tap water, filtered through gauze, the filtrate distributed into 10 ml tubes and centrifuged at 1000×g for 10 min. The supernatant was removed, flotation fluid added to each tube up to 8 ml and centrifuged at 53×g for 1 min. The supernatant was filtered through a 20 μm sieve and the sieves examined microscopically for A. alata eggs using a Leica DMRB light microscope (Leica Microsystems A/S, Brønshøj, Denmark).

2.2.2. Echinococcus multilocularis

Genomic DNA was isolated from 0.25 g faeces using DNeasy PowerSoil Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) following the instructions of the manufacturer. Samples were analysed for the presence of E. multilocularis eggs using the E. multilocularis primer set EmSP1-A’/B′ with forward primer 5′-GTCATATTTGTTTAAGTATAAGTGG-3′ and reverse primer 5′-CACTCTTATTTACACTAGAATTAAG-3’ (Nonaka et al., 2009) targeting a fraction of the cytochrome c oxidase subunit I gene (cox1). For all reactions, mastermix were prepared containing all ingredients to ensure homogeneity between wells. All reactions in volumes of 22 μl, containing 0.7 μM of each primer, 5u/μl KAPA 2G robust DNA polymerase, 5.0 μl KAPA 2G buffer, 5.0 μl KAPA Enhancer (all KAPA 2G products were included in the KAPA 2G Robust PCR kit, Sigma-Aldrich, Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany), 0.2 mM dNTP, 2.0 μl DNA and dH2O. The PCR was performed in a conventional PCR machine using the following conditions: 95 °C for 15 min followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 30 s, 50 °C for 30 s, 72 °C for 30 s and final extension for 10 min at 72 °C. The protocol could consistently amplify DNA from two E. multilocularis eggs per 0.25 g faeces. A negative control without DNA was included in all tests.

2.2.3. Trichinella spp

Muscles from thighs were analysed for Trichinella spp. larvae by the magnetic stirrer method for pooled sample digestion according to Mayer-Scholl et al. (2017). Briefly, 20 g individual muscle samples from 10 animals were mixed with digestion fluid. The mixture was then stirred for a maximum of 60 min at 45 °C, subsequently sieved and allowed to sediment for 30 min. The sediment was collected and allowed to sediment for another 10 min. The supernatant was removed and the sediment was analysed for presence of Trichinella spp. larvae by stereomicroscopy at × 20 magnification using a Leica M125 stereo microscope (Leica Microsystems A/S, Brønshøj, Denmark).

2.2.4. Toxoplasma gondii

Antibodies against T. gondii were examined in meat juice from the heart using a commercial indirect enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ID Screen® Toxoplasmosis Indirect Multi-species ELISA kit, ID.vet, France). The heart was placed in a plastic funnel (CC Plast A/S, Hillerød, Denmark) at room temperature as described by Nielsen et al. (1998). Meat juice was collected in a 10 ml tube during thawing and placed at −20 °C until further analysis. The collected meat juice was subsequently examined for IgG antibodies, following the instructions of the manufacturer (ID Screen® Toxoplasmosis Indirect Multi-species ELISA kit, ID.vet, France). The samples and the controls provided in the kit were analysed in duplicate. The optical density (OD) was read at 450 nm. Results were evaluated following the instructions of the manufacturer for carnivores by calculating the S/P% (sample/positive percentage) = (mean OD of sample − mean OD of negative control)/(mean OD of positive control − mean OD of negative control) × 100. Samples with S/P% ≤40% were considered negative, 40–70% doubtful, and ≥70% positive. Raccoon dogs that tested positive with the ELISA were considered seropositive; others were considered seronegative.

2.3. Tick collection and screening for tick-borne pathogens

Raccoon dogs were macroscopically screened for ticks, particularly the inner thighs, belly and eye area. Tick larvae and nymphs were screened for pathogens commonly known or assumed present in Denmark: A. phagocytophilum, Babesia spp. (B. divergens, B. microti, B. canis, B. venatorum), species belonging to the B. burgdorferi s.l. species complex (Borrelia garinii, B. afzelii, B. spielmanii, B. valaisiana, B. lusitaniae, B. burgdorferi sensu strictu), B. miyamotoi, N. mikurensis, C. burnetii, F. tularensis, and R. helvetica (Table 1) (Kjær et al., 2020a; Klitgaard et al., 2019b; Michelet et al., 2014). We focused on larvae in this study, as any tick-borne pathogens found in the larvae could indicate infection transmitted from the raccoon dog to the tick larvae. The most common tick species in Denmark, the castor bean tick (Ixodes ricinus) only feeds once per life cycle (larva-nymph-adult, Estrada-Peña and de la Fuente, 2014), and thus pathogens found within larvae may come from this first blood meal taken from the raccoon dogs. Naturally, this only pertains to pathogens that are not vertically transmitted within the tick vector (Han et al., 2019; Michelitsch et al., 2019; Oechslin et al., 2017; Sprong et al., 2009).

2.3.1. DNA extraction

The ticks were washed in 70% ethanol followed by 2 × 5 min in sterile water. We added 75 μl of incubation buffer (D920), 75 μl of lysis buffer (MC501) and 3 mm tungsten beads (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), and homogenized the ticks in a TissueLyser II (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). DNA was subsequently isolated using the Maxwell 16 LEV Blood DNA kit (Promega, Madison, Wisconsin, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions with a few modifications (samples were incubated at 56 °C overnight).

2.3.2. Screening of tick-borne pathogens by real-time PCR

We examined the ticks for the presence of the above mentioned bacterial and parasitic pathogens (see section 2.2) via the BioMark real-time PCR system (Fluidigm, San Francisco, California, USA). Whereas I. ricinus is the most common tick in Scandinavia, the closely related taiga tick, I. persulcatus, has been found in Sweden and the meadow tick Dermacentor reticulatus has sporadically been found in both Denmark, Norway and Sweden. Thus, we additionally screened for the tick species I. ricinus, I. persulcatus and D. reticulatus. The method used is thoroughly described in Michelet et al. (2014), Klitgaard et al. (2019b) and in Kjær et al. (2020a). Prior to the analysis, we homogenized the ticks using a TissueLyser II (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) in a mixture of 75 μl Incubation buffer (D920), 75 μl Lysis buffer (MC501) and with three 3-mm Tungsten beads (Qiagen) for 2 × 2.5 min at 25 Hz. We then pre-amplified the DNA in a master mix consisting of 2.5 μL TaqMan PreAmp Master Mix (2X), 1.2 μL pooled primer mix (except primers targeting tick DNA) and 1.3 μL DNA. We did not pre-amplify tick DNA, as homogenising whole ticks, should provide enough tick DNA for analysis. The samples ran one cycle at 95 °C for 10 min, 14 cycles at 95 °C for 15 s and 4 min at 60 °C. We first diluted the pre-amplified DNA 5-fold in water after which we ran the real-time PCR with FAM and black hole quencher (BHQ1)-labelled TaqMan probes with TaqMan Gene Expression Master Mix according to the manufacturer's instructions (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, California, USA). The final cycles were performed as follows: 50 °C for 2 min, 95 °C for 10 min, 40 cycles at 95 °C for 15 s, and at 60 °C for 15 s. The results were obtained through the BioMark real-time PCR system and analysed using the Fluidigm real-time PCR Analysis software, and cut-off values for crossing points (CP) were set to ≤28. We included one negative water control and Escherichia coli primers and probes for internal inhibition control (Michelet et al., 2014). Numerous studies have used and validated the Fluidigm real-time PCR system (Klitgaard et al, 2017a, 2019a, 2019b; Michelet et al., 2014; Moutailler et al., 2016; Reye et al., 2013).

2.4. Statistical analyses

When possible, depending on sample size, the prevalence of the zoonotic parasitic infections, the sero-prevalence of T. gondii and the prevalence of pathogens in ticks were calculated with their respective 95% confidence intervals (CI). Also when possible, differences in prevalence were determined by a binary logistic regression model with pathogen as the dependent variable and sex and region of origin as independent variables using SAS 9.4 software (SAS for Windows, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). The variables are analysed independently. A p-value below 0.05 was considered significant.

3. Results

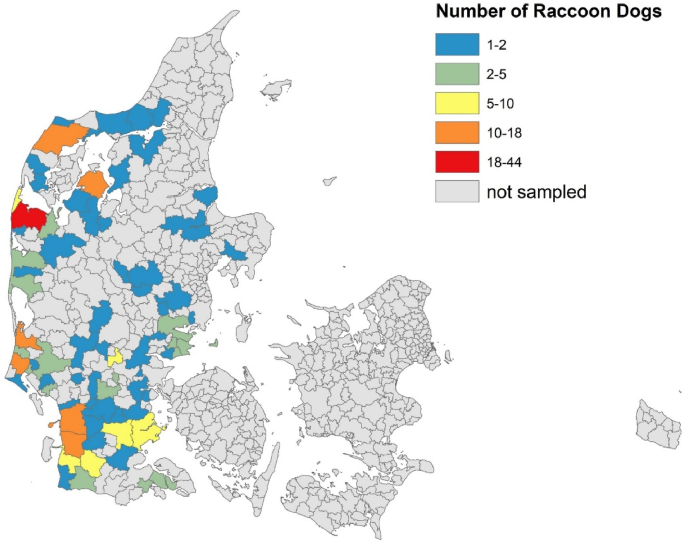

A total of 292 raccoon dogs were included in the study. Of these, 149 (47.6%) were males and 139 (51.0%) females, while sex was not recorded for four (1.4%) raccoon dogs. All raccoon dogs originated from the Jutland peninsula of Denmark (Fig. 1), with 30 (10.3%) animals originating from Northern Jutland, 121 (41.4%) from Middle Jutland and 141 (48.3%) from Southern Jutland.

Fig. 1.

Map of Denmark showing the origin of the collected raccoon dogs by county. The colour coding shows differences in the number of raccoon dogs collected. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

3.1. Parasites

Table 2 gives an overview of examined raccoon dogs and raccoon dogs positive for the various parasites along with their 95% CIs. All raccoon dogs were negative for Trichinella spp. and E. multilocularis, while 32.9% excreted A. alata eggs and 42.7% were sero-positive for T. gondii. Neither A. alata, nor T. gondii was associated with sex or region of origin.

Table 2.

Prevalence and 95% confidence intervals of zoonotic parasites and tick-borne pathogens in raccoon dogs by sex and region. CI=Confidence interval.

| Total |

Malesa |

Femalesa |

Northern Jutland |

Middle Jutland |

Southern Jutland |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pathogen | Pos/total | % [95% CI] | Pos/total | % [95% CI] | Pos/total | % [95% CI] | Pos/total | % [95% CI] | Pos/total | % [95% CI] | Pos/total | % [95% CI] |

| Alaria alata | 78/237 | 32.9 [27.0–39.3] | 39/118 | 33.1 [24.7–42.3] | 39/117 | 33.3 [24.9–42.6] | 10/28 | 35.7 [18.6–55.9] | 31/98 | 31.6 [22.6–41.8] | 37/111 | 33.3 [24-7-42.9] |

| Echinococcus multilocularis | 0/281 | – | 0/142 | – | 0/134 | – | 0/29 | – | 0/118 | – | 0/133 | – |

| Trichinella spp. | 0/233 | – | 0/114 | – | 117 | – | 0/29 | – | 0/90 | – | 0/114 | – |

| Toxoplasma gondii | 97/227 | 42.7 [36.2–49.5] | 53/110 | 48.2 [35.2–57.9] | 43/115 | 37.4 [28.6–46.9] | 16/28 | 57.1 [37.2–75.5] | 33/98 | 37.1 [27.1–48.0] | 48/111 | 43.6 [34.2–53.4] |

Sex was unknown for two raccoon dogs.

3.2. Tick-borne diseases

In total, 41 raccoon dogs were examined for ticks. Of these 41 raccoon dogs, 25 carried 392 tick larvae in total. We decided to test 10 larvae from each raccoon dog for pathogens due to time and funding available. Only 15 raccoon dogs contained 10 or more larvae, resulting in analysis of 150 individual larvae. Additionally, if any of the selected 15 raccoon dogs had ten or more nymphs, then we would screen ten nymphs from each raccoon dog as well. Only 4 of the raccoon dogs with ten or more larvae also had ten or more nymphs. From 150 larvae screened for tick DNA, 127 larvae from 13 individual raccoon dogs were successfully amplified by PCR, all of which were identified as I. ricinus (Table 3). Ixodes persulcatus and D. reticulatus were not detected. Failed pre-amplification of tick DNA is most likely due to insufficient crushing of the ticks prior to extraction. Insufficient crushing may also affect the extraction of pathogen DNA and these samples were therefore omitted from the analysis.

Table 3.

Overview of the results from the screening of tick-borne pathogens. Only tests where the positive control for I. ricinus DNA was validated are depicted. # Raccoon dogs in parenthesis denote how many raccoon dogs the positive larvae and nymphs stemmed from. None of the ticks tested positive for B. afzelii, B. garinii, B. burgdorferi sensu stricto, B. spielmanii, B. valaisiana, B. lusitaniae, B. divergens, B. microti, B. canis, B. henselae, C. burnetii or F. tularensis.

| Pathogen | # larvae testeda | #positive larvae (# raccoon dogs) | # nymphs testedb | # positive nymphs (#raccoon dogs) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anaplasma phagocytophilum | 127 | 10 (3) | 22 | 7 (1) |

| Babesia canis | 127 | 0 | 22 | 0 |

| Babesia divergens | 127 | 0 | 22 | 0 |

| Babesia microti | 127 | 0 | 22 | 0 |

| Babesia venatorum | 127 | 1 (1) | 22 | 0 |

| Bartonella henselae | 127 | 0 | 22 | 0 |

| Borrelia spp. | 127 | 0 | 22 | 0 |

| Borrelia miyamotoi | 127 | 1 (1) | 22 | 0 |

| Coxiella burnetii | 127 | 0 | 22 | 0 |

| Francisella tularensis | 127 | 0 | 22 | 0 |

| Neoehrlichia mikurensis | 127 | 1 (1) | 22 | 2 (1) |

| Rickettsia helvetica | 127 | 17 (8) | 22 | 5 (2) |

Stemmed from 13 raccoon dogs.

Stemmed from 3 raccoon dogs.

We found A. phagocytophilum in 3/13 remaining raccoon dogs. One raccoon dogs had 1/10 analysed larvae testing positive for A. phagocytophilum, one raccoon dog had 3/10 larvae testing positive, and one raccoon dog had 6/9 larvae testing positive for A. phagocytophilum. Rickettsia helvetica was found in 17 larvae distributed on 8 raccoon dogs. From the 127 analysed larvae, one tested positive for B. venatorum, one for B. myiamotoi and one for N. mikurensis (Table 3).

From 40 nymphs screened for tick DNA, 22 nymphs from 3 individual raccoon dogs were successfully amplified by PCR and identified as I. ricinus (Table 3). From the raccoon dog with six A. phagocytophilum positive larvae, 7/9 nymphs were additionally positive for A. phagocytophilum. An overview of the pathogen results are listed in Table 3.

Prevalence and 95% CIs were not calculated due to low number of raccoon dogs. We furthermore did not conduct any statistical analyses as the statistical power given these sample sizes, would be very low.

4. Discussion

This is the first investigation of T. gondii sero-prevalence and tick-borne pathogens in raccoon dogs from Denmark. Moreover, we studied the prevalence of the zoonotic parasites Trichinella spp., A. alata and E. multilocularis to get updated information on the occurrence in the increasing raccoon dog population. The results demonstrated that a noteworthy proportion of raccoon dogs from Denmark are infected with A. alata (32.9%) and are T. gondii sero-positive (42.7%), while the zoonotic parasites E. multilocularis and Trichinella spp. were not identified. A previous Danish study identified E. multilocularis in 2/123 raccoon dogs from South Jutland (Petersen et al., 2018), an area where 21 raccoon dogs in our study also originated from. In contrast, Trichinella spp. infection remain unidentified in raccoon dogs from Denmark, although both E. multilocularis and Trichinella spp. are prevalent in raccoon dogs from other European countries (Cybulska et al., 2019; Laurimaa et al., 2015; Mayer-Scholl et al., 2016; Oksanen et al., 2016). However, the absence of E. multilocularis and Trichinella spp. positive raccoon dogs in our study cannot exclude a negligible prevalence of these parasites in Danish raccoon dogs.

Nearly half the raccoon dogs (42.7%) in our study were T. gondii sero-positive. Infection was unrelated to sex or region of origin, thus T. gondii infection is prevalent throughout the raccoon dog population. Toxoplasma gondii sero-positive Danish wildlife species (Christiansen and Siim, 1951; Laforet et al., 2019), livestock (Agerholm et al., 2006; Kofoed et al., 2017) and humans (Burgdorf et al., 2019) have previously been identified. Studies of T. gondii infections in raccoon dogs are generally scarce, and those studies existing are mostly performed on farmed domestic raccoon dogs from China (Qin et al., 2020; Zheng et al., 2017). However, T. gondii positive wild-living raccoon dogs from Poland have been identified (Kornacka et al., 2016; Sroka et al., 2019). Raccoon dogs consume a wide range of food items including small mammals, birds and carrions (Mikkelsen et al., 2016), all of which can carry T. gondii cysts (Dubey, 2002; Tenter et al., 2000) and be a source of infection for the raccoon dogs.

Almost one third (32.9%) of the raccoon dogs excreted eggs of A. alata. This finding is significantly lower than a previous Danish study of A. alata infection in raccoon dogs (69.7%) (Al-sabi et al., 2013). In other European countries, the prevalence of A. alata in raccoon dogs varied from 30% in Austria (Duscher et al., 2017) to 96.5% in Lithuania (Bružinskaitė-Schmidhalter et al., 2012). However, the previous study identified adult Alaria worm in the whole intestine, while in our study we identified eggs excreted in faeces. The differences in method used could explain the lower prevalence observed in our study compared to the previous Danish study. The adult stage of A. alata parasitize the small intestine of carnivores, where embryonated eggs are excreted with faeces. Subsequently, A. alata needs two intermediate hosts to develop into infective mesocercariae. The final host is reached by ingestion of an infected amphibian secondary intermediate host or a paratenic host harbouring mesocercariae. Numerous animal species can act as paratenic hosts (Odening 1963; Möhl et al., 2009). In Denmark, mesocercariae have been identified in 66.7% of badgers (6/9) and 3.0% of feral cats (3/99) (Takeuchi-Storm et al., 2015), whereas 34.4% of examined red foxes had adult worms in the intestine (Al-sabi et al., 2013) indicating that A. alata is highly prevalent in Denmark. Humans can act as paratenic hosts for Alaria spp., however, reports of human alariosis have only been published for the American species of the genus Alaria (Beaver et al., 1977; Fernandes et al., 1976; Fried and Abruzzi, 2010; Möhl et al., 2009). Thus, Odening (1963) has shown severe infestation in rhesus macaque (Macaca mulatta) experimentally infected with A. alata, proving that a host closely related to humans can become infected with this trematode.

The real-time PCR test for tick-borne pathogens only identified the tick species I. ricinus, which is also the most common tick species found in Denmark and Northern Europe. We also screened for the meadow tick, D. reticulatus and the taiga tick I. persulcatus. Although I. persulcatus has not been found in Denmark (Kjær et al., 2019), it has been found in northern Sweden (Jaenson et al., 2016), thus we included it in our screening. Dermacentor reticulatus has been found on a migrating golden jackal (Canis aureus) in Denmark (Klitgaard et al., 2017b) and several dogs on the Danish islands of Lolland and Falster have recently been diagnosed with canine babesiosis, caused by Babesia canis which is only transmitted via D. reticulatus in Denmark (data not published). This suggests that D. reticulatus is present in Denmark, but so far we have not been able to confirm this (Kjær et al., 2019). Furthermore, with the small sample sizes used in the screening for tick- and pathogen species in this study, we cannot rule out the presence of species not found through the real-time PCR.

We found A. phagocytophilum, B. venatorum, B. myiamotoi, N. mikurensis, and R. helvetica in the tick nymphs and larvae analysed from the raccoon dogs. In the larvae, we found a relatively high percentage of the raccoon dogs with R. helvetica and A. phagocytophilum. Vertical transmission from mother to offspring has been documented for R. helvetica and B. myiamotoi in Ixodid ticks (Breuner et al., 2017; Han et al., 2019; Socolovschi et al., 2009; Sprong et al., 2009), thus we cannot conclude that these pathogens were transmitted from the raccoon dog host to the tick larvae. Many of the Babesia species also exhibit transovarial transmission from female to offspring (Bonnet et al., 2007; Øines et al., 2012), and the one B. venatorum positive larva we found, could have obtained the pathogen through the adult female tick. However, there is no evidence for vertical transmission of A. phagocytophilum in I. ricinus (Jaarsma et al., 2019; Severinsson et al., 2010). Among the 17 ticks (10 larvae and 7 nymphs) testing positive for A. phagocytophilum, 6 larvae and 7 nymphs originated from the same raccoon dog, whereas 3 other larvae originated from one other raccoon dog. This high level of clustering of positive ticks on individual raccoon dogs strongly suggests that raccoon dogs may function as reservoirs of A. phagocytophilum and infect I. ricinus larvae with the pathogen. While it is still unknown whether N. mikurensis can be transmitted transovarially, most researchers agree that this is not the common transmission pathway (Jahfari et al., 2012; Obiegala and Silaghi, 2018; Silaghi et al., 2012). We only found two raccoon dogs with ticks positive for N. mikurensis (one with one positive larva and one with two positive nymphs), thus our study cannot conclude whether raccoon dogs may serve as reservoir host for N. mikurensis. Studies from Poland and Germany have detected both A. phagocytophilum and N. mikurensis in raccoon dogs (Hildebrand et al., 2018; Szewczyk et al., 2019), so our findings, at least for A. phagocytophilum correspond well with what has been found elsewhere in Europe.

Anaplasma phagocytophilum has long been known to cause tick-borne fever in domestic ruminants and can cause high fever, anorexia, drop in milk yield, abortion in ewes and reduced fertility in rams (Stuen et al., 2013). As a zoonosis, A. phagocytophilum can cause human granulocytic anaplasmosis, with symptoms varying from mild fever and influenza-like symptoms to fatal infections (Heyman et al., 2010; Stuen et al., 2013). Natural reservoirs of A. phagocytophilum are rodents, wild ruminants and birds (Heyman et al., 2010; Jaarsma et al., 2019). Neoehrlichia mikurensis has only recently been discovered as a cause of human disease, and many aspect of this pathogen have not yet been fully investigated (Obiegala and Silaghi, 2018; Portillo et al., 2018). However, it is believed that rodents are the main reservoirs of this pathogen (Obiegala and Silaghi, 2018; Portillo et al., 2018). Neoehrlichia mikurensis mostly affects immunosuppressed people and causes mild fever, joint pain, headache, and in some cases rashes (Obiegala and Silaghi, 2018). Wildlife reservoirs of zoonotic pathogens help maintain these pathogens in the environment, where they can continuously infect animals and humans. Although the racoon dog population in Denmark is fairly limited, it seems to be continuously increasing (The Environmental Protection Agency, n.d.). Being a natural reservoir of A. phagocytophilum and potentially N. mikurensis and other tick-borne pathogens, an increasing raccoon dog population may play a role in maintaining and spreading these zoonotic pathogens, potentially increasing the health risk for livestock, wildlife and humans.

5. Conclusion

Assuming T. gondii sero-positivity equals hosting viable parasites, a great proportion of raccoon dogs from Denmark are potential reservoir of T. gondii cysts. Also, raccoon dogs are a potential reservoir of A. alata infection, while our findings suggest that raccoon dogs are negligible reservoir of E. multilocularis and Trichinella spp. infections. Since raccoon dogs are not consumed, the risk of acquiring T. gondii infection when handling them is considered negligible. However, raccoon dogs seems to be an essential factor in the continued maintenance of these infections in the environment and there is a risk of acquiring the infection when handling the raccoon dogs during pelting if the hygiene is poor. Strong clustering of A. phagocytophilum-positive ticks on individual raccoon dogs analysed in this study indicates that raccoon dogs may act as reservoirs of this parasite and thus may play a part in maintaining and spreading A. phagocytophilum in nature.

Declaration of competing interest

None.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by the Ministry of Environment and Food of Denmark and the Environmental Protection Agency, Denmark. We thank The Danish Nature Agency and Danish Hunters association for submitting the raccoon dogs. The authors also thank the laboratory technicians in the parasitology laboratory at the Centre for Diagnostics, Technical University of Denmark for skilled technical assistance with analysing the samples. Lastly, we thank Sandra Helmark Hansen for the skilful hand drawings used in the graphical abstract.

References

- Agerholm J.S., Aalbaek B., Fog-Larsen A.M., Boye M., Holm E., Jensen T.K., Lindhardt T., Larsen L.E., Buxton D. Veterinary and medical aspects of abortion in Danish sheep. Acta Pathol. Microbiol. Immunol. Scandivica. 2006;114:146–152. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0463.2006.apm_362.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-sabi M.N.S., Hammer T., Chriél M., Larsen Enemark H. Endoparasites of the raccoon dog (Nyctereutes procyonoides) and the red fox (Vulpes vulpes) in Denmark 2009–2012 – a comparative study. Int. J. Parasitol. Parasites Wildl. 2013;2:144–151. doi: 10.1016/j.ijppaw.2013.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaver P.C., Little M.D., Tucker C.F., Reed R.J. Mesocercaria in the skin of man in Louisiana. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1977;26:422–426. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1977.26.422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonnet S., Jouglin M., Malandrin L., Becker C., Agoulon A., L'Hostis M., Chauvin A. Transstadial and transovarial persistence of Babesia divergens DNA in Ixodes ricinus ticks fed on infected blood in a new skin-feeding technique. Parasitology. 2007;134:197–207. doi: 10.1017/S0031182006001545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breuner N.E., Dolan M.C., Replogle A.J., Sexton C., Hojgaard A., Boegler K.A., Clark R.J., Eisen L. Transmission of Borrelia miyamotoi sensu lato relapsing fever group spirochetes in relation to duration of attachment by Ixodes scapularis nymphs. Ticks Tick. Borne. Dis. 2017;8:677–681. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2017.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bružinskaitė-Schmidhalter R., Šarkūnas M., Malakauskas A., Mathis A., Torgerson P.R., Deplazes P. Helminths of red foxes (Vulpes vulpes) and raccoon dogs (Nyctereutes procyonoides) in Lithuania. Parasitology. 2012;139:120–127. doi: 10.1017/S0031182011001715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgdorf K.S., Trabjerg B.B., Pedersen M.G., Nissen J., Banasik K., Pedersen O.B., Sørensen E., Nielsen K.R., Larsen M.H., Erikstrup C., Bruun-Rasmussen P., Westergaard D., Thørner L.W., Hjalgrim H., Paarup H.M., Brunak S., Pedersen C.B., Torrey E.F., Werge T., Mortensen P.B., Yolken R.H., Ullum H. Large-scale study of Toxoplasma and Cytomegalovirus shows an association between infection and serious psychiatric disorders. Brain Behav. Immun. 2019;79:152–158. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2019.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byström M., Böcher S., Magnusson A., Prag J., Johansson A. Tularemia in Denmark: identification of a Francisella tularensis subsp. holarctica strain by real-time PCR and high-resolution typing by multiple-locus variable-number tandem repeat analysis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2005;43:5355–5358. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.10.5355-5358.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhry S., Gad N., G K. Toxoplasmosis and pregnancy. Can. Fam. Physician. 2014;60:334–336. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christiansen M., Siim J.C. Toxoplasmosis in hares in Denmark. Serological identity of human and hare strains of Toxoplasma. Lancet. 1951;1:1201–1203. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(51)92707-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotté V., Bonnet S., Rhun D. Le, Naour E. Le, Chauvin A., Boulouis H.-J., Lecuelle B., Lilin T., Vayssier-Taussat M. Transmission of Bartonella henselae by Ixodes ricinus. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2008;14:1074. doi: 10.3201/EID1407.071110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cybulska A., Kornacka A., Moskwa B. The occurrence and muscle distribution of Trichinella britovi in raccoon dogs (Nyctereutes procyonoides) in wildlife in the Głęboki Bród Forest District, Poland. Int. J. Parasitol. Parasites Wildl. 2019 doi: 10.1016/j.ijppaw.2019.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darwin Murrell K., Pozio E. Worldwide occurrence and impact of human trichinellosis, 1986-2009. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2011;17:2194–2202. doi: 10.3201/eid1712.110896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denmark Statistics . 2021. Organic Livestock by Species of Animals and Time. [WWW Document] [Google Scholar]

- Dietrich F., Schmidgen T., Maggi R.G., Richter D., Matuschka F.R., Vonthein R., Breitschwerdt E.B., Kempf V.A.J. Prevalence of Bartonella henselae and Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato DNA in Ixodes ricinus ticks in Europe. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2010;76:1395–1398. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02788-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubey J.P. A review of toxoplasmosis in wild birds. Vet. Parasitol. 2002;106:121–153. doi: 10.1016/S0304-4017(02)00034-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duscher T., Hodžić A., Glawischnig W., Duscher G.G. The raccoon dog (Nyctereutes procyonoides) and the raccoon (Procyon lotor)—their role and impact of maintaining and transmitting zoonotic diseases in Austria, Central Europe. Parasitol. Res. 2017;116:1411–1416. doi: 10.1007/s00436-017-5405-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enemark H.L., Bjørn H., Henriksen S.A., Nielsen B. Screening for infection of Trichinella in red fox (Vulpes vulpes) in Denmark. Vet. Parasitol. 2000;88:229–237. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4017(99)00219-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estrada-Peña A., de la Fuente J. The ecology of ticks and epidemiology of tick-borne viral diseases. Antivir. Res. 2014;108:104–128. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2014.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fallahi S., Rostami A., Nourollahpour Shiadeh M., Behniafar H., Paktinat S. An updated literature review on maternal-fetal and reproductive disorders of Toxoplasma gondii infection. J. Gynecol. Obstet. Hum. Reprod. 2018;47:133–140. doi: 10.1016/j.jogoh.2017.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes B.J., Cooper J.D., Cullen J.B., Freeman R.S., Ritchie A.C., Scott A.A., Stuart P.F. Systemic infection with Alaria americana (Trematoda) Can. Med. Assoc. J. 1976;115:1111–1114. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fertner M.E., Mølbak L., Pihl T.P.B., Fomsgaard A., Bødker R. First detection of tick-borne “Candidatus Neoehrlichia mikurensis” in Denmark 2011. Euro Surveill. 2012;17:20096. doi: 10.2807/ese.17.08.20096-en. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flegr J., Prandota J., Sovičková M., Israili Z.H. Toxoplasmosis - a global threat. Correlation of latent toxoplasmosis with specific disease burden in a set of 88 countries. PloS One. 2014;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0090203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fomsgaard A., Fertner M.E., Essbauer S., Nielsen A.Y., Frey S., Lindblom P., Lindgren P.-E., Bødker R., Weidmann M., Dobler G. Tick-borne encephalitis virus, Zealand, Denmark, 2011. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2013;19:1171–1173. doi: 10.3201/eid1907.130092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fried B., Abruzzi A. Food-borne trematode infections of humans in the United States of America. Parasitol. Res. 2010;106:1263–1280. doi: 10.1007/s00436-010-1807-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frivik J.O., Noraas S., Grankvist A., Wennerås C., Quarsten H. En mann i 60-årene fra Sørlandet med intermitterende feber (In Norwegian) Tidsskr. Den Nor. legeforening. 2017;137 doi: 10.4045/tidsskr.17.0353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grankvist A., Andersson P.-O., Mattsson M., Sender M., Vaht K., Hoper L., Sakiniene E., Trysberg E., Stenson M., Fehr J., Pekova S., Bogdan C., Bloemberg G., Wenneras C. Infections with the tick-borne bacterium ‘Candidatus Neoehrlichia mikurensis’ mimic noninfectious conditions in patients with B cell malignancies or autoimmune diseases. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2014;58:1716–1722. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han Y.J., Park J., Lee Y.S., Chae J. seok, Yu D.H., Park B.K., Kim H.C., Choi K.S. Molecular identification of selected tick-borne pathogens in wild deer and raccoon dogs from the Republic of Korea. Vet. Parasitol. Reg. Stud. Rep. 2017;7:25–31. doi: 10.1016/j.vprsr.2016.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han S., Lubelczyk C., Hickling G.J., Belperron A.A., Bockenstedt L.K., Tsao J.I. Vertical transmission rates of Borrelia miyamotoi in Ixodes scapularis collected from white-tailed deer. Ticks Tick. Borne. Dis. 2019;10:682–689. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2019.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Härtwig V., von Loewenich F.D., Schulze C., Straubinger R.K., Daugschies A., Dyachenko V. Detection of Anaplasma phagocytophilum in red foxes (Vulpes vulpes) and raccoon dogs (Nyctereutes procyonoides) from Brandenburg, Germany. Ticks Tick. Borne. Dis. 2014;5:277–280. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2013.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedges T. Diffuse unilateral subacute neuroretinopathy. Princ. Pract. Ophthalmol. Clin. Pract. 2000;3:2167. [Google Scholar]

- Heyman P., Heyman P., Cochez C., Sprong H., Porter S.R., Losson B., Saegerman C., Donoso-mantke O., Niedrig M. A clear and present danger : tick-borne diseases in Europe. Expert Rev. Anti Infect. Ther. 2010;8:33–50. doi: 10.1586/eri.09.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hildebrand J., Buńkowska-Gawlik K., Adamczyk M., Gajda E., Merta D., Popiołek M., Perec-Matysiak A. The occurrence of Anaplasmataceae in European populations of invasive carnivores. Ticks Tick. Borne. Dis. 2018;9:934–937. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2018.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland G.N. Ocular toxoplasmosis: a global reassessment. Part I: epidemiology and course of disease. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2003;136:973–988. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2003.09.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaarsma R.I., Sprong H., Takumi K., Kazimirova M., Silaghi C., Mysterud A., Rudolf I., Beck R., Földvári G., Tomassone L., Groenevelt M., Everts R.R., Rijks J.M., Ecke F., Hörnfeldt B., Modrý D., Majerová K., Votýpka J., Estrada-Peña A. Anaplasma phagocytophilum evolves in geographical and biotic niches of vertebrates and ticks. Parasites Vectors. 2019;12:328. doi: 10.1186/s13071-019-3583-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaenson T.G.T., Värv K., Fröjdman I., Jääskeläinen A., Rundgren K., Versteirt V., Estrada-Peña A., Medlock J.M., Golovljova I. First evidence of established populations of the taiga tick Ixodes persulcatus (Acari: Ixodidae) in Sweden. Parasites Vectors. 2016;9:377. doi: 10.1186/s13071-016-1658-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahfari S., Fonville M., Hengeveld P., Reusken C., Scholte E.-J., Takken W., Heyman P., Medlock J.M., Heylen D., Kleve J., Sprong H. Prevalence of Neoehrlichia mikurensis in ticks and rodents from North-west Europe. Parasit. Vectors. 2012;5:74. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-5-74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen P.M., Christoffersen C.S., Moutailler S., Michelet L., Klitgaard K., Bødker R. Transmission differentials for multiple pathogens as inferred from their prevalence in larva, nymph and adult of Ixodes ricinus (Acari: Ixodidae) Exp. Appl. Acarol. 2017;71:171–182. doi: 10.1007/s10493-017-0110-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jongejan F., Ringenier M., Putting M., Berger L., Burgers S., Kortekaas R., Lenssen J., van Roessel M., Wijnveld M., Madder M. Novel foci of Dermacentor reticulatus ticks infected with Babesia canis and Babesia caballi in The Netherlands and in Belgium. Parasites Vectors. 2015;8:232. doi: 10.1186/s13071-015-0841-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang J.G., Chae J.B., Cho Y.K., Jo Y.S., Shin N.S., Lee H., Choi K.S., Yu D.H., Park J., Park B.K., Chae J.S. Molecular detection of Anaplasma, Bartonella, and Borrelia theileri in raccoon dogs (Nyctereutes procyonoides) in Korea. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2018;98:1061–1068. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.17-0380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson M.E., Andersson M.O. Babesia species in questing Ixodes ricinus, Sweden. Ticks Tick. Borne. Dis. 2016;7:10–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2015.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kauhala K., Kowalczyk R. Invasion of the raccoon dog <i>Nyctereutes procyonoides<I> in Europe: history of colonization, features behind its success, and threats to native fauna. Curr. Zool. 2011;57:584–598. doi: 10.1093/czoolo/57.5.584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keesing F., Hersh M.H., Tibbetts M., McHenry D.J., Duerr S., Brunner J., Killilea M., LoGiudice K., Schmidt K.A., Ostfeld R.S. Reservoir competence of vertebrate hosts for Anaplasma phagocytophilum. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2012;18 doi: 10.3201/eid1812.120919. 2013–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kjær L.J., Soleng A., Edgar K.S., Lindstedt H.E.H., Paulsen K.M., Andreassen Å.K., Korslund L., Kjelland V., Slettan A., Stuen S., Kjellander P., Christensson M., Teräväinen M., Baum A., Isbrand A., Jensen L.M., Klitgaard K., Bødker R. A large-scale screening for the taiga tick, Ixodes persulcatus, and the meadow tick, Dermacentor reticulatus, in southern Scandinavia. Parasites Vectors. 2019;12:338. doi: 10.1186/s13071-019-3596-3. 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kjær L.J., Klitgaard K., Soleng A., Edgar K.S., Lindstedt H.E.H., Paulsen K.M., Andreassen Å.K., Korslund L., Kjelland V., Slettan A., Stuen S., Kjellander P., Christensson M., Teräväinen M., Baum A., Jensen L.M., Bødker R. Spatial patterns of pathogen prevalence in questing Ixodes ricinus nymphs in southern Scandinavia, 2016. Sci. Rep. 2020;10:19376. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-76334-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kjær L.J., Klitgaard K., Soleng A., Skarsfjord Edgar K., Elisabeth Lindstedt H.H., Paulsen K.M., Kristine andreassen Å., Korslund L., Kjelland V., Slettan A., Stuen S., Kjellander P., Christensson M., Teräväinen M., Baum A., Mark Jensen L., Bødker R. Spatial data of Ixodes ricinus instar abundance and nymph pathogen prevalence, Scandinavia, 2016-2017. Sci. Data. 2020;71 7:1–7. doi: 10.1038/s41597-020-00579-y. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kjelland V., Stuen S., Skarpaas T., Slettan A. Prevalence and genotypes of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato infection in Ixodes ricinus ticks in southern Norway. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 2010;42:579–585. doi: 10.3109/00365541003716526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klitgaard K., Chriél M., Isbrand A., Jensen T.K., Bødker R. Identification of Dermacentor reticulatus ticks carrying Rickettsia raoultii on migrating jackal, Denmark. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2017;23:2072–2074. doi: 10.3201/eid2312.170919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klitgaard K., Chriél M., Isbrand A., Jensen T.K., Bødker R. Identification of Dermacentor reticulatus ticks carrying Rickettsia raoultii on migrating jackal, Denmark. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2017;23:2072–2074. doi: 10.3201/eid2312.170919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klitgaard K., Højgaard J., Isbrand A., Madsen J.J., Thorup K., Bødker R. Screening for multiple tick-borne pathogens in Ixodes ricinus ticks from birds in Denmark during spring and autumn migration seasons. Ticks Tick. Borne. Dis. 2019;10:546–552. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2019.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klitgaard K., Kjær L.J., Isbrand A., Hansen M.F., Bødker R. Multiple infections in questing nymphs and adult female Ixodes ricinus ticks collected in a recreational forest in Denmark. Ticks Tick. Borne. Dis. 2019;10:1060–1065. doi: 10.1016/J.TTBDIS.2019.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kofoed K.G., Vorslund-Kiær M., Nielsen H.V., Alban L., Johansen M.V. Sero-prevalence of Toxoplasma gondii in Danish pigs. Vet. Parasitol. 2017;10:136–138. doi: 10.1016/j.vprsr.2017.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornacka A., Cybulska A., Bień J., Goździk K., Moskwa B. The usefulness of direct agglutination test, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and polymerase chain reaction for the detection of Toxoplasma gondii in wild animals. Vet. Parasitol. 2016;228:85–89. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2016.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause P.J., Fish D., Narasimhan S., Barbour A.G. Borrelia miyamotoi infection in nature and in humans. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2015;21:631–639. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2015.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laforet C.K., Deksne G., Petersen H.H., Jokelainen P., Johansen M.V., Lassen B. Toxoplasma gondii seroprevalence in extensively farmed wild boars (Sus scrofa) in Denmark. Acta Vet. Scand. 2019;61:4. doi: 10.1186/s13028-019-0440-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurimaa L., Süld K., Moks E., Valdmann H., Umhang G., Knapp J., Saarma U. First report of the zoonotic tapeworm Echinococcus multilocularis in raccoon dogs in Estonia, and comparisons with other countries in Europe. Vet. Parasitol. 2015;212:200–205. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2015.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundkvist Å., Wallensten A., Vene S., Hjertqvist M. Tick-borne encephalitis increasing in Sweden, 2011. Euro Surveill. 2011;16:19981. doi: 10.2807/ese.16.39.19981-en. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malakauskas A., Paulauskas V., Järvis T., Keidans P., Eddi C., Kapel C.M.O. Molecular epidemiology of Trichinella spp. in three Baltic countries: Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia. Parasitol. Res. 2007;100:687–693. doi: 10.1007/s00436-006-0320-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer-Scholl A., Reckinger S., Schulze C., Nöckler K. Study on the occurrence of Trichinella spp. in raccoon dogs in Brandenburg, Germany. Vet. Parasitol. 2016;231:102–105. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2016.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer-Scholl A., Pozio E., Gayda J., Thaben N., Bahn P., Nöckler K. Magnetic stirrer method for the detection of Trichinella larvae in muscle samples. JoVE. 2017;121:55354. doi: 10.3791/55354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michelet L., Delannoy S., Devillers E., Umhang G., Aspan A., Juremalm M., Chirico J., van der Wal F.J., Sprong H., Boye Pihl T.P., Klitgaard K., Bãdker R., Fach P., Moutailler S. High-throughput screening of tick-borne pathogens in Europe. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2014;4:103. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2014.00103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michelitsch A., Wernike K., Klaus C., Dobler G., Beer M. Exploring the reservoir hosts of tick-borne Encephalitis virus. Viruses. 2019;11:669. doi: 10.3390/v11070669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikkelsen D.M.G., Nørgaard L.S., Jensen T.H., Chriél M., Pertoldi C., Elmeros M. Mårhundens (Nyctereutes procyonoides) føde og fødeoverlap med hjemmehørende rovdyr i Danmark [in Danish] Flora Fauna. 2016;122:101–114. [Google Scholar]

- Möhl K., Große K., Hamedy A., Wüste T., Kabelitz P., Lücker E. Biology of Alaria spp. and human exposition risk to Alaria mesocercariae— a review. Parasitol. Res. 2009;105:1–15. doi: 10.1007/s00436-009-1444-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montoya J., Liesenfeld O. Toxoplasmosis. Lancet. 2004;363:1965–1976. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16412-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moutailler S., Valiente Moro C., Vaumourin E., Michelet L., Tran F.H., Devillers E., Cosson J.-F., Gasqui P., Van V.T., Mavingui P., Vourc’h G., Vayssier-Taussat M. Co-infection of ticks: the rule rather than the exception. PLoS Neglected Trop. Dis. 2016;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen B., Ekeroth L., Bager F., Lind P. Use of muscle fluid as a source of antibodies for serologic detection of Salmonella infection in slaughter pig herds. J. Vet. Diagn. Invest. 1998;10:158–163. doi: 10.1177/104063879801000207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson K., Elfving K., Påhlson C. Rickettsia helvetica in patient with meningitis, Sweden, 2006. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2010;16:490–492. doi: 10.3201/eid1603.090184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nonaka N., Kamiya M., Kobayashi F., Ganzorig S., Ando S., Yagi K., Iwaki T., Inoue T., Oku Y. Echinococcus multilocularis infection in pet dogs in Japan. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2009;9:201–206. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2008.0097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obiegala A., Silaghi C. Candidatus Neoehrlichia mikurensis—recent insights and future perspectives on clinical cases, vectors, and reservoirs in Europe. Curr. Clin. Microbiol. Reports. 2018;5:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s40588-018-0085-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Oechslin C.P., Heutschi D., Lenz N., Tischhauser W., Péter O., Rais O., Beuret C.M., Leib S.L., Bankoul S., Ackermann-Gäumann R. Prevalence of tick-borne pathogens in questing Ixodes ricinus ticks in urban and suburban areas of Switzerland. Parasites Vectors. 2017;10:558. doi: 10.1186/s13071-017-2500-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Øines Ø., Storli K., Brun-Hansen H. First case of babesiosis caused by Babesia canis canis in a dog from Norway. Vet. Parasitol. 2010;171:350–353. doi: 10.1016/J.VETPAR.2010.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Øines Ø., Radzijevskaja J., Paulauskas A., Rosef O. Prevalence and diversity of Babesia spp. in questing Ixodes ricinus ticks from Norway. Parasites Vectors. 2012;5:156. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-5-156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oksanen A., Siles-Lucas M., Karamon J., Possenti A., Conraths F.J., Romig T., Wysocki P., Mannocci A., Mipatrini D., La Torre G., Boufana B., Casulli A. The geographical distribution and prevalence of Echinococcus multilocularis in animals in the European Union and adjacent countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Parasites Vectors. 2016;9:519. doi: 10.1186/s13071-016-1746-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostfeld R.S., Levi T., Jolles A.E., Martin L.B., Hosseini P.R., Keesing F. Life history and demographic drivers of reservoir competence for three tick-borne zoonotic pathogens. PloS One. 2014;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0107387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozoliņa Z., Mateusa M., Šuksta L., Liepiņa L., Deksne G. The wild boar (Sus scrofa, Linnaeus, 1758) as an important reservoir host for Alaria alata in the Baltic region and potential risk of infection in humans. Vet. Parasitol. Reg. Stud. Rep. 2020;22 doi: 10.1016/J.VPRSR.2020.100485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen J.M., Mead P.S., Schriefer M.E. Francisella tularensis: an arthropod-borne pathogen. Vet. Res. 2009;40:7. doi: 10.1051/VETRES:2008045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen H.H., Al-Sabi M.N.S., Enemark H.L., Kapel C.M.O., Jørgensen J.A., Chriél M. Echinococcus multilocularis in Denmark 2012–2015: high local prevalence in red foxes. Parasitol. Res. 2018;117:2577–2584. doi: 10.1007/s00436-018-5947-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portillo A., Santibáñez P., Palomar A.M., Santibáñez S., Oteo J.A. ‘Candidatus Neoehrlichia mikurensis’ in Europe. New Microb. New Infect. 2018;22:30–36. doi: 10.1016/j.nmni.2017.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin S.Y., Chu D., Sun H.T., Wang D., Xie L.H., Xu Y., Li J.H., Cui D.Y., You F., Cai Y., Jiang J. Prevalence and genotyping of Toxoplasma gondii infection in raccoon dogs (Nyctereutes procyonoides) in Northern China. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2020;20:231–235. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2019.2512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quarsten H., Grankvist A., Høyvoll L., Myre I.B., Skarpaas T., Kjelland V., Wenneras C., Noraas S. Candidatus Neoehrlichia mikurensis and Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato detected in the blood of Norwegian patients with erythema migrans. Ticks Tick. Borne. Dis. 2017;8:715–720. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2017.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reye A.L., Stegniy V., Mishaeva N.P., Velhin S., Hübschen J.M., Ignatyev G., Muller C.P. Prevalence of tick-borne pathogens in Ixodes ricinus and Dermacentor reticulatus ticks from different geographical locations in Belarus. PloS One. 2013;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riehn K., Hamedy A., Grosse K., Wüste T., Lücker E. Alaria alata in wild boars (Sus scrofa, Linnaeus, 1758) in the eastern parts of Germany. Parasitol. Res. 2012;111:1857–1861. doi: 10.1007/S00436-012-2936-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seiwald S., Simeon A., Hofer E., Weiss G., Bellmann-Weiler R. Tularemia goes west: epidemiology of an emerging infection in Austria. Microorganisms. 2020;8:1–13. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms8101597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Severinsson K., Jaenson T.G., Pettersson J., Falk K., Nilsson K. Detection and prevalence of Anaplasma phagocytophilum and Rickettsia helvetica in Ixodes ricinus ticks in seven study areas in Sweden. Parasites Vectors. 2010;3:1–7. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-3-66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silaghi C., Woll D., Mahling M., Pfister K., Pfeffer M. Candidatus Neoehrlichia mikurensis in rodents in an area with sympatric existence of the hard ticks Ixodes ricinus and Dermacentor reticulatus, Germany. Parasites Vectors. 2012;5:285. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-5-285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skarphédinsson S., Lyholm B.F., Ljungberg M., Søgaard P., Kolmos H.J., Nielsen L.P. Detection and identification of Anaplasma phagocytophilum, Borrelia burgdorferi, and Rickettsia helvetica in Danish Ixodes ricinus ticks. APMIS. 2007;115:225–230. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0463.2007.apm_256.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Socolovschi C., Mediannikov O., Raoult D., Parola P. The relationship between spotted fever group rickettsiae and ixodid ticks. Vet. Res. 2009;40:34. doi: 10.1051/vetres/2009017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Špitalská E., Kocianová E. Detection of Coxiella burnetii in ticks collected in Slovakia and Hungary. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2003;183 18:263–266. doi: 10.1023/A:1023330222657. 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprong H., Wielinga P.R., Fonville M., Reusken C., Brandenburg A.H., Borgsteede F., Gaasenbeek C., van der Giessen J.W. Ixodes ricinus ticks are reservoir hosts for Rickettsia helvetica and potentially carry flea-borne Rickettsia species. Parasites Vectors. 2009;2:41. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-2-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprong H., Tijsse-Klasen E., Langelaar M., Bruin A. De, Fonville M., Gassner F., Takken W., Wieren S. Van, Nijhof A., Jongejan F., Maassen C.B.M., Scholte E.-J., Hovius J.W., Hovius K.E., Špitalská E., Duynhoven Y.T. Van. Prevalence of Coxiella Burnetii in ticks after a large outbreak of Q fever. Zoonoses Publ. Health. 2012;59:69–75. doi: 10.1111/J.1863-2378.2011.01421.X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sroka J., Karamon J., Wójcik-Fatla A., Dutkiewicz J., Bilska-Zając E., Zając V., Piotrowska W., Cencek T. Toxoplasma gondii infection in selected species of free-living animals in Poland. Ann. Agric. Environ. Med. 2019;26:656–660. doi: 10.26444/aaem/114930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuen S., Granquist E.G., Silaghi C. Anaplasma phagocytophilum—a widespread multi-host pathogen with highly adaptive strategies. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2013;3:31. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2013.00031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svensson J., Hunfeld K.-P., Persson K.E.M. High seroprevalence of Babesia antibodies among Borrelia burgdorferi-infected humans in Sweden. Ticks Tick. Borne. Dis. 2019;10:186–190. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2018.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szewczyk T., Werszko J., Myczka A.W., Laskowski Z., Karbowiak G. Molecular detection of Anaplasma phagocytophilum in wild carnivores in north-eastern Poland. Parasites Vectors. 2019;12:465. doi: 10.1186/s13071-019-3734-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeuchi-Storm N., Al-Sabi M.N.S., Thamsborg S.M., Enemark H.L. Alaria alata mesocercariae among feral cats and badgers, Denmark. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2015;21:1872–1874. doi: 10.3201/eid2010.141817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tenter A.M., Heckeroth A.R., Weiss L.M. Toxoplasma gondii: from animals to humans. Int. J. Parasitol. 2000;30:1217–1258. doi: 10.1016/S0020-7519(00)00124-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Environmental Protection Agency Mårhund. https://mst.dk/natur-vand/natur/artsleksikon/pattedyr/maarhund/ n.d. [WWW Document] accessed 5.29.20.

- Tobudic S., Burgmann H., Stanek G., Winkler S., Schötta A.-M., Obermüller M., Markowicz M., Lagler H. Human Borrelia miyamotoi infection, Austria. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2020;26:2201–2204. doi: 10.3201/EID2609.191501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torgerson P.R., Schweiger A., Deplazes P., Pohar M., Reichen J., Ammann R.W., Tarr P.E., Halkik N., Müllhaupt B. Alveolar echinococcosis: from a deadly disease to a well-controlled infection. Relative survival and economic analysis in Switzerland over the last 35 years. J. Hepatol. 2008;49:72–77. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2008.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vennestrøm J., Egholm H., Jensen P.M. Occurrence of multiple infections with different Borrelia burgdorferi genospecies in Danish Ixodes ricinus nymphs. Parasitol. Int. 2008;57:32–37. doi: 10.1016/J.PARINT.2007.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veterinary Danish, Food Administration Trichinella. https://www.foedevarestyrelsen.dk/english/Food/Trichinella/Pages/default.aspx n.d. [WWW Document] accessed 5.26.20.

- Welinder-Olsson C., Kjellin E., Vaht K., Jacobsson S., Wennerås C., Wenneras C. First case of human ‘Candidatus Neoehrlichia mikurensis’ infection in a febrile patient with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2010;48 doi: 10.1128/JCM.02423-09. 1956–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilhelmsson P., Fryland L., Börjesson S., Nordgren J., Bergström S., Ernerudh J., Forsberg P., Lindgren P.-E. Prevalence and diversity of Borrelia species in ticks that have bitten humans in Sweden. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2010;48:4169–4176. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01061-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wodecka B., Michalik J., Lane R.S., Nowak-Chmura M., Wierzbicka A. Differential associations of Borrelia species with European badgers (Meles meles) and raccoon dogs (Nyctereutes procyonoides) in western Poland. Ticks Tick. Borne. Dis. 2016;7:1010–1016. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2016.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng W. Bin, Cong W., Hou J., Ma J.G., Zhang X.X., Zhu X.Q., Meng Q.F., Zhou D.H. Seroprevalence and risk factors of Toxoplasma gondii infection in farmed raccoon dogs (Nyctereutes procyonoides) in China. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2017;17:209–212. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2016.2035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]