Abstract

G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) are dimeric proteins, but the functional consequences of the process are still debated. Active GPCR conformations are promoted either by agonists or constitutive activity. Inverse agonists decrease constitutive activity by promoting inactive conformations. The histamine H3 receptor (H3R) is the target of choice for the study of GPCRs because it displays high constitutive activity. Here, we study the dimerization of recombinant and brain H3R and explore the effects of H3R ligands of different intrinsic efficacy on dimerization. Co-immunoprecipitations and Western blots showed that H3R dimers co-exist with monomers in transfected HEK 293 cells and in rodent brains. Bioluminescence energy transfer (BRET) analysis confirmed the existence of spontaneous H3R dimers, not only in living HEK 293 cells but also in transfected cortical neurons. In both cells, agonists and constitutive activity of the H3R decreased BRET signals, whereas inverse agonists and GTPγS, which promote inactive conformations, increased BRET signals. These findings show the existence of spontaneous H3R dimers not only in heterologous systems but also in native tissues, which are able to adopt a number of allosteric conformations, from more inactive to more active states.

Keywords: BRET, brain, constitutive activity, dimerization, GPCR, H3R

1. Introduction

A large body of biochemical and biophysical evidence indicates that G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) form dimers not only in heterologous systems but also in native tissues [1,2,3,4,5,6]. The observation that GPCRs can form dimers or larger oligomers has led to intense research to study the functional and physiological relevance of such complex formations [7,8,9,10,11].

Although some studies have suggested that agonists can regulate dimers by either promoting or inhibiting their formation [12,13,14,15], a general consensus tends to conclude that dimerization is a spontaneous process that pre-dates receptor activation [6,16,17,18,19]. In addition, in some studies, ligands do not influence dimerization [20,21,22], whereas, in others, they induce important conformational changes in dimers, leading to allosteric interactions between the two protomers [23,24,25,26,27,28,29].

Active GPCR conformations are not only promoted by agonists but also occur in their absence, leading to constitutive activity. Inverse agonists decrease constitutive activity by promoting inactive conformations. Whether an alteration of this constitutive activity by inverse agonists leads to changes in the amounts and/or conformations of dimers remains unclear. In fact, very few studies have addressed the putative relationship existing between constitutive activity and the dimerization of GPCRs. In cross-linking experiments performed on the dopamine D2 receptor, the homodimer interface in the inverse agonist-bound conformation is consistent with the dimer of the inactive form of rhodopsin [25]. In trafficking experiments on the dopamine D1 receptor, inverse agonists induced a conformational change, which stabilized D1 receptor dimers at the cell surface [28]. It was also suggested that inverse agonist binding to the second protomer of a Class A GPCR dimer enhances signaling, i.e., that constitutive activity of this second protomer inhibits signaling [26]. This assumption is consistent with studies on the Class C mGluR, in which the inactive state of a protomer caused by inverse agonist binding results in more efficient activation of the adjacent protomer [30,31].

We identified the histamine H3 receptor (H3R) as an autoreceptor located on histaminergic nerve endings, controlling histamine synthesis and release in the brain [32,33]. Since then, it has been shown that many H3Rs in the brain are, in fact, located in many neuronal populations [34] and play a role in the pathophysiology of various central nervous system diseases [35]. The H3R is a target of choice for the molecular study of GPCRs [36]. Both the rat and human H3Rs display a high level of constitutive activity [37,38,39]. We also demonstrate a high constitutive activity of cerebral H3Rs, thereby bringing evidence of the constitutive activity of native GPCRs in vitro and in vivo [38,40,41]. H3R dimerization has been reported in previous studies [42,43]; however, the functional consequence of the process has not yet been explored.

In the present study, we used Western blot, co-immunoprecipitation, and bioluminescence resonance energy transfer (BRET) analyses to further investigate the dimerization of recombinant and brain H3Rs, as well as their regulation by agonists and inverse agonists in human embryonic kidney 293 (HEK 293) cells and cultured cortical neurons.

2. Results

2.1. Biochemical Detection of H3R Dimers

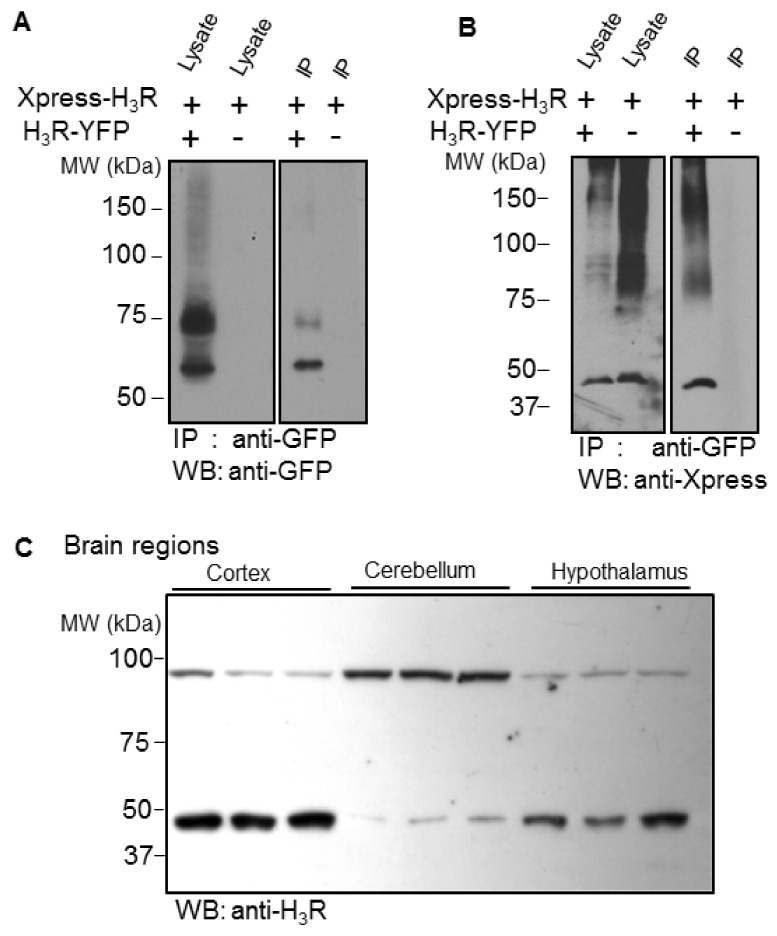

We first investigated H3R dimerization by performing co-immunoprecipitation experiments. HEK293 cells were co-transfected with two different H3R constructs, H3R-YFP and Xpress-H3R, expressing the receptor tagged at its N-terminus with an Xpress epitope. After solubilization, cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with an anti-GFP-antibody and assessed for the presence of H3R-YFP with the anti-GFP antibody and for the presence of Xpress-H3R with the anti-Xpress antibody. Western blot analysis of the co-immunoprecipitates with the anti-GFP antibody revealed two prominent immunoreactive species at around 75 and 65 kDa (Figure 1A), representing the glycosylated and non-glycosylated monomeric forms of the recombinant H3R-YFP (see Figure S1). As shown in Figure 1B, Xpress-H3R specifically co-immunoprecipitates with H3R-YFP both as monomeric (~45 kDa) and SDS-resistant oligomeric forms (~90 and >120 kDa). We then performed Western blot analysis of membranes from rat brain regions using a specific anti-H3R antibody (Figure S2). The labeling of two prominent immunoreactive species was observed with sizes of ~45 and 90 kDa, expected for the monomeric and dimeric forms of the receptor (Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

Detection of H3R dimers in HEK293 cells and rat brain regions. The Xpress-tagged H3 receptor (Xpress-H3R) was expressed transiently in HEK293 cells in the presence or absence of H3R-YFP. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated using GFP-Trap agarose beads (A,B). Lysates or immunoprecipitates (IP) were separated by SDS/PAGE on 8% (A) or 10% (B) gels. Analysis was performed by Western blot (WB) using a polyclonal anti-GFP antibody (A) and a monoclonal anti-Xpress antibody (B). Membranes from rat cerebral cortex, cerebellum, and hypothalamus were separated by a NuPAGE 7% Tris-acetate gel system and analyzed by Western blot using the anti-H3R antibody (C). Similar results were obtained using three different lysates from each brain region.

2.2. Detection of Constitutive H3R Dimers in Living HEK-293 Cells by BRET

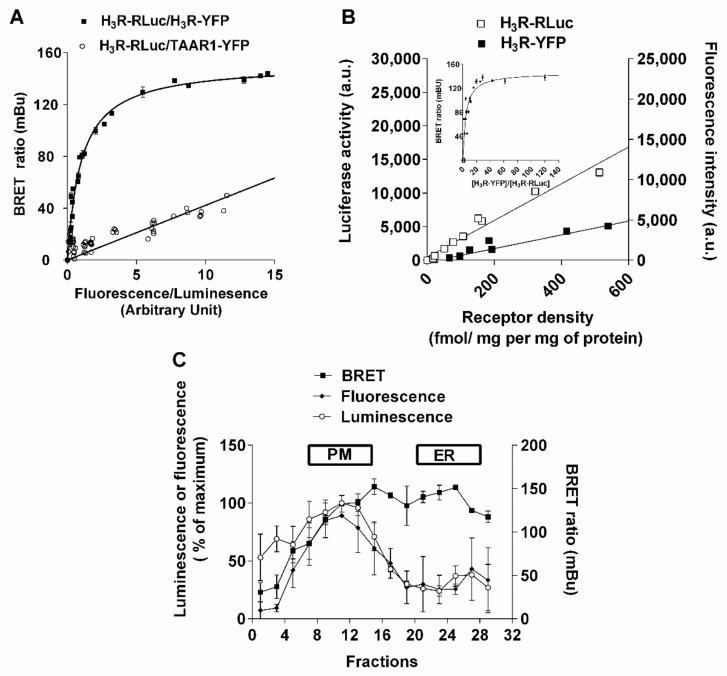

We also studied H3R dimerization in intact living HEK-293 cells by BRET analysis with the proper controls required by this approach [44,45,46,47]. The specificity of H3R dimerization was shown by the high energy transfer in cells co-expressing H3R-RLuc (H3R fused to Renilla Luciferase (RLuc)) with H3R-YFP (H3R fused to Yellow Fluorescent Protein (YFP)), and by the lower energy transfer in cells co-expressing H3R-RLuc with TAAR1-YFP. The extent of energy transfer between the RLuc and YFP tags of the H3R was plotted as a function of increasing acceptor–donor ratios (Figure 2A). The curve obtained for H3R-RLuc-H3R-YFP was saturated and best fitted by s non-linear regression equation (BRETmax = 144 ± 3 mBU). When cells were transfected with H3R-RLuc, tracemine-associated receptor 1 (TAAR1)-YFP signals were best fitted by linear regression.

Figure 2.

Characterization of H3R BRET signals. (A) The BRET donor saturation curve of H3R-RLuc-H3R-YFP (■) is compared with that obtained with a control receptor (○) (TAAR1-YFP). BRET saturation curves were generated by transient transfection of HEK 293 cells with a constant DNA amount of H3R-RLuc and increasing quantities of H3R-YFP or TAAR1-YFP. BRET, total luminescence, and total fluorescence were measured 48 h after transfection. BRET levels were plotted as a function of the ratio of the expression level of the YFP construct (quantitated by the total fluorescence of the cells) over the RLuc construct (quantitated by the luminescence of the cells) (fluorescence/luminescence). The results are representative of three independent experiments carried out in triplicate. The curve obtained for H3R-RLuc-H3R-YFP was best fitted with a non-linear regression equation assuming a single binding site (BRETmax = 144 ± 3 mBU), and the curve obtained for H3R-RLuc-TAAR1-YFP was best fitted with a linear regression equation. (B) To correlate fluorescence and luminescence levels with H3 receptor densities, HEK 293 cells were transfected with increasing DNA concentrations of the H3R-Rluc or H3R-YFP constructs. Forty-eight hours after transfection, luminescence and fluorescence were measured, and H3R expression was determined by radioligand binding assay cells that were diluted in HBSS and distributed in 96-well microplates for luminescence or fluorescence measurements at a density of ~100,000 cells per well. To correlate the luminescence and fluorescence values with receptor densities, the specific number of [125I]iodoproxyfan binding sites was determined in the same cells. Luminescence (right, Y-axis) and fluorescence (left, Y-axis) were plotted against binding densities, and the linear regression of the data was performed using GraphPad Prism (inset, Figure 2B) as follows: H3R-Rluc: y = 26.3x + 467; H3R-YFP: y = 8.5x + 258). The BRET saturation curve presented in the inset was generated from the corrected ratio [H3R-YFP]/[H3R-Rluc], determined by transforming luminescence and fluorescence values measured for each data point into receptor densities using the equations described above. (C) Sub-cellular distribution of H3R dimers. HEK 293 cells were transfected with H3R-RLuc and H3R-YFP. Sub-cellular fractions were subjected to fluorescence/luminescence and BRET analysis. Means ± SEM of 6 determinations from 2 separate experiments.

In order to exclude that the dimerization process is due to H3R overexpression in the heterologous system, we ensured that H3R was expressed at the physiological level in our BRET experiments. For this purpose, the luminescence and fluorescence signals obtained after transfection of different concentrations of H3R-RLuc or H3R-YFP plasmids were correlated to the receptor density measured in cells by binding experiments (Figure 2B). Then, cells were co-transfected with constant amounts of H3R-Rluc (~20 fmol/mg protein) construct and increasing amounts of H3R-YFP plasmid. The amount of each receptor species effectively expressed in transfected cells was determined for each condition by correlating luminescence and fluorescence signals with receptor densities (Figure 2B inset). BRET signals increased as a hyperbolic function of the ratio between the BRET acceptor and donor to reach a plateau (maximal energy transfer (BRETmax)) of ~150 mBU from a ratio of ~15 (Figure 2B). In addition, the formation of constitutive H3R dimers did not result from an over-expression of the receptor in transfected cells since BRET signals are independent of H3R density (Figure S3). When the ratio H3R-YFP/H3R-Luc was selected to ensure a BRETmax signal, it remained constant over a wide range of H3R densities (from 50 fmol/mg protein to 1 pmol/mg protein).

In terms of the dimerization of various GPCRs occurring at early stages of receptor biosynthesis within the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), we further analyzed the distribution of H3R dimers by cell-fractionation studies. The distributions of the fluorescent and luminescent receptors both indicated that the vast majority (~80%) of total H3Rs were exported from the ER to the plasma membrane (Figure 2C). BRETmax values on membrane preparations were slightly higher than in whole living cells, in agreement with various studies indicating that the energy transfer depends on the environment [23]. These maximal BRET values were reached not only at the plasma membrane but also in the ER (Figure 2C), indicating that dimerization of the H3R occurs early during its biosynthesis.

2.3. Effects of H3R Ligands on BRET in HEK 293 Living Cells

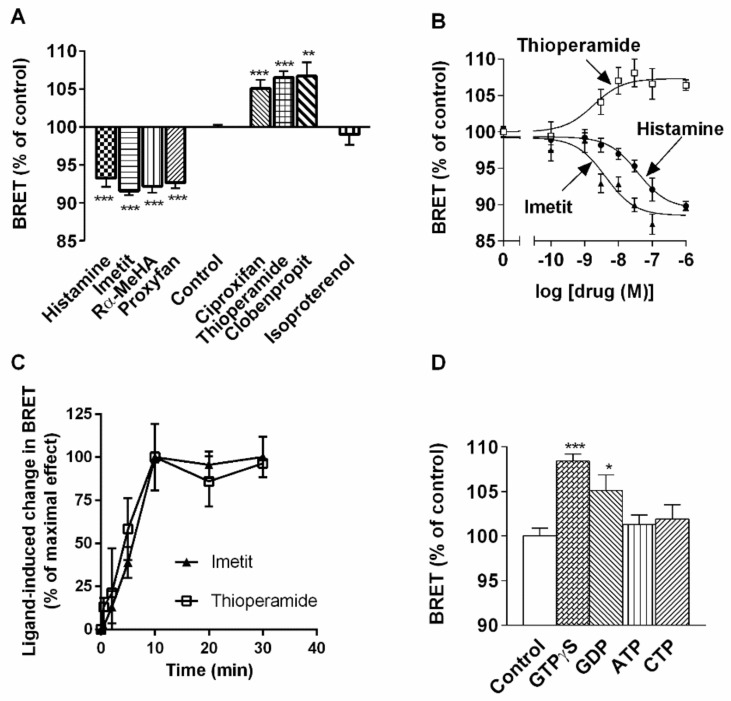

We investigated the effect of various H3R agonists and inverse agonists on constitutive BRET signals observed in living HEK (H3R) cells (Figure 3). All agonists, including histamine and standard H3R agonists (R)-α-methylhistamine [32] and imetit [48], significantly decreased (by ~10%) maximal BRET signals (Figure 3A). In contrast, all inverse agonists, including the standard compounds thioperamide [32], ciproxifan [49], and clobenpropit [50], significantly increased BRET signals (by ~7%) (Figure 3A). The protean agonist proxyfan [36,51] mimicked the effect of agonists and decreased BRET signals to the same extent. The β-adrenergic agonist isoproterenol did not significantly modify BRET signals (Figure 3A). Histamine and imetit decreased BRET in a dose-dependent manner, with similar maximal effects and EC50 values of 28 ± 2 and 4 ± 2 nM, respectively (Figure 3B), leading to relative potencies in the same range as those observed in H3R-mediated responses [48] (Figure 3B). The increase induced by the inverse agonist thioperamide was also concentration-dependent and saturable. It occurred with an EC50 value of 2 ± 1 nM (Figure 3B), in the same range as its inverse agonist potency on various H3R-mediated responses [41]. The BRET changes induced by imetit and thioperamide were time-dependent. They increased rapidly to reach a plateau within 10 min after drug exposure (Figure 3C). The BRET signals obtained without exposure to the ligands remained stable over 30 min (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Effects of H3-receptor ligands on H3-receptor homodimerization in HEK 293 cells. HEK 293 cells expressing H3R-RLuc and H3R-YFP (200–500 fmol per mg protein; sub-maximal BRET) were incubated with isoproterenol (1 µM) or H3 ligands at fixed (100 nM) (A) or increasing (B) concentrations. (C) BRET kinetic analysis of ligand-induced BRET changes in living HEK 293 cells co-transfected with H3R-Rluc and H3R-YFP. (D) Membranes prepared from HEK 293 cells co-expressing H3R-RLuc and H3R-YFP were incubated with various nucleotides (100 µM). The results are representative of three or four experiments carried out in triplicate. Data are expressed as a percent of BRET signals in controls. * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001 versus control.

The addition of the stable GTP analog GTPγS (100 µM) mimicked the effect of inverse agonists and enhanced BRET signals by the same amplitude (Figure 3D). This effect was partially reproduced with GDP (100 µM), whereas ATP and CTP (100 µM) had no significant effect (Figure 3D).

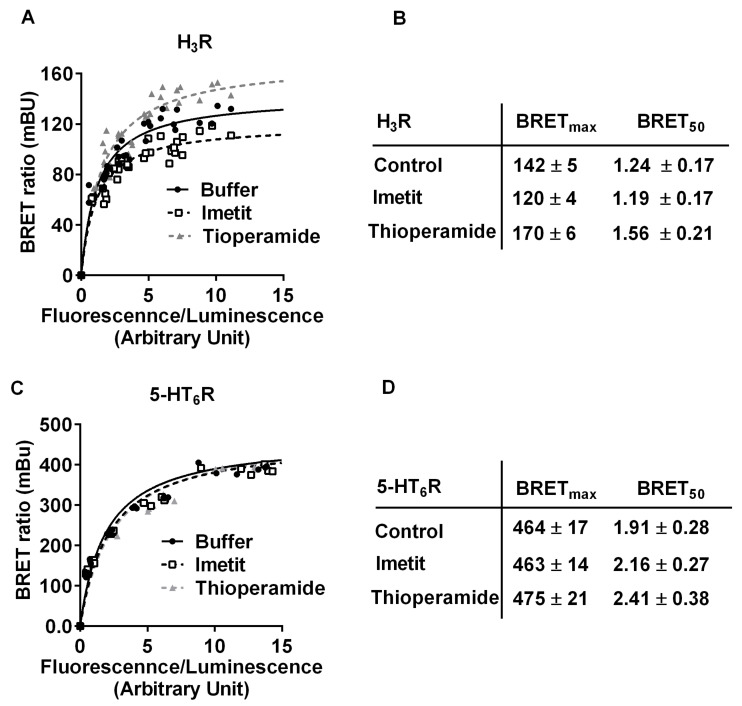

The magnitude of the opposite effects of the agonist imetit and inverse agonist thioperamide was inversely related to BRET levels (Figure 4A,B). It was significantly higher at low BRET levels (20–40% of basal BRET15–30) than at higher BRET levels (~10% of basal BRET75-max). When BRET values were analyzed in the presence of imetit or thioperamide, the BRETmax values were significantly different from controls (p < 0.001), whereas the BRET50 values remained unchanged (BRET50 basal = 1.24 ± 0.017; BRET50 imetit = 1.19 ± 0.17, and BRET50 thioperamide = 1.56 ± 0.21). The H3R ligands did not significantly modify the BRET signals obtained after co-expression in the cells of the serotonin 5-HT6 receptors, 5-HT6R-RLuc and 5-HT6R-YFP (Figure 4C,D), indicating that changes induced by these ligands were selective of H3R dimers.

Figure 4.

BRET saturation curves of homodimerization of H3R and 5-HT6R in HEK-293 cells. (A) BRET signals were performed on HEK 293 cells transiently transfected with a constant DNA amount of H3R-RLuc (A) or 5-HT6-RLuc (C) and increasing quantities of, respectively, H3R-YFP (A) or 5-HT6-YFP (C). BRET signals were determined in the absence (control) or presence of 100 nM of the H3R agonist (imetit) or 100 nM of the H3R inverse agonist (thioperamide). The curves were fitted using a non-linear regression equation assuming a single binding site (GrapPadPrism). The goodness of fit was given by r2 values that were very close to unity in each dose–response curve: r2 = 0.928, 0.926, and 0.928 for control, imetit, and thioperamide, respectively. Data were obtained from three separate experiments with triplicate determinations. (B,D) Parameters derived from BRET saturation curves of the homodimerization of H3R (A) or 5-HT6R (B) in the absence or presence of imetit or thioperamide. Data were analyzed by two-way ANOVA as follows: factor BRET level F(13, 42) = 195.5, p < 0.0001; factor treatment F(2, 42) = 104.1, p < 0.0001; and interaction F(26, 42) = 3.53, p = 0.0001.

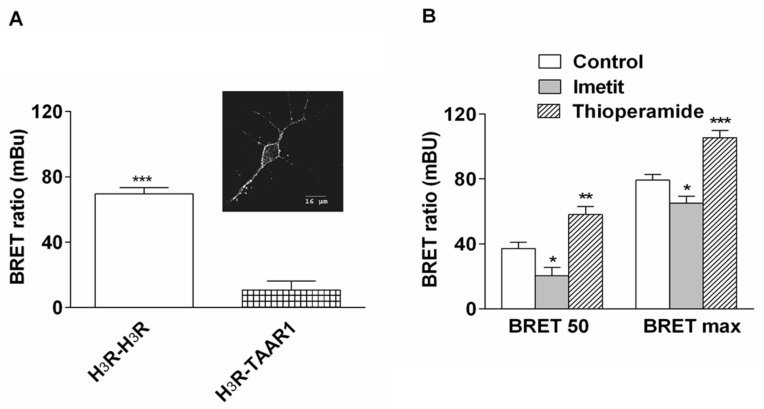

2.4. Effects of H3R Ligands on BRET in Cultured Cortical Neurons

BRET experiments were also conducted on living cortical neurons in primary culture (Figure 5). The sub-cellular localization of the fluorescent receptor expressed in neurons indicated that the H3R was predominantly found at the plasma membrane (Figure 5A). BRET signals were spontaneously generated in neurons after their co-transfection with H3R-YFP and H3R-RLuc. The specificity of this signal was illustrated by the absence of any significant energy transfer between H3R-RLuc and the control TAAR1 receptor (TAAR1-YFP) (Figure 5A). The constitutive BRETmax in neurons was about half that observed in HEK-293 cells (~70 versus ~140 mBU). Imetit and thioperamide (100 nM) did not modify the net BRET ratio when the donor H3R-RLuc was expressed alone but induced a significant decrease and increase, respectively, of the net BRET ratio obtained after co-expression of H3R-RLuc and H3R-YFP in cortical neurons (Figure 5B). The changes observed in neurons were much higher than those observed in HEK-293 cells. Thus, at half-maximal BRET of the controls, imetit decreased constitutive BRET signals by 45 ± 9%, whereas thioperamide increased them by 56 ± 13%. As observed in fibroblasts, the changes were inversely related to BRET levels. Interestingly, imetit still decreased constitutive BRETmax by 18 ± 4%, and thioperamide still increased BRETmax by 33 ± 8% (Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

Effects of H3-receptor ligands on BRET signals in cultured cortical neurons. (A) Sub-cellular localization of H3R-YFP in rat cortical neurons, as observed by confocal microscopy two days after transfection. (A) Cortical neurons were transfected with H3R-RLuc and H3R-YFP or TAAR1-YFP as a control receptor in order to obtain sub-maximal BRET signals. A similar level of H3R-YFP and TAAR1-YFP expression was ensured by fluorescence analysis. Data are the means of 6 values from two independent experiments. *** p < 0.001 versus H3R-TAAR1 heterodimers. (B) Effects of ligands (100 nM) on H3R dimerization were evaluated at two different BRET levels. Means ± SEM of 18–24 values from 3–4 separate experiments. Two way ANOVA was performed as follows: factor BRET F(1, 99) = 152.2, p < 0.001; factor treatment F(2, 99) = 34.8, p < 0.001; and interaction F(2, 99) = 0.196, p = 0.8. Then, the effect of ligands was evaluated in each BRET group using a non-parametric Wilcoxon/Mann–Whitney test, * p < 0.05, ** p <0.01, *** p < 0.001 versus respective control.

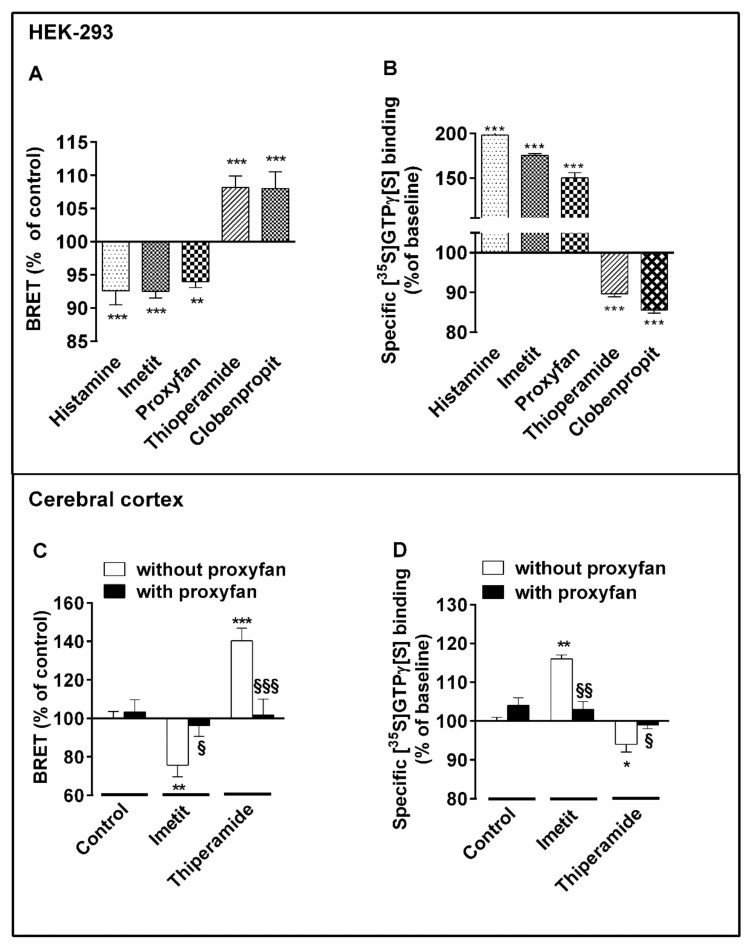

2.5. Comparison of the Effects of H3R Ligands on H3R-Mediated BRET Signals and [35S]GTPγS Binding in HEK 293 Cells and Rat Cerebral Cortex

In order to further determine whether the changes of BRET induced by H3R ligands were related to their functional properties at the H3R, we compared the effects of the agonists histamine and imetit, the inverse agonists thioperamide and clobenpropit, and the protean agonist proxyfan on both [35S]GTPγS binding used as a functional response and BRET signals.

In membranes from HEK 293 cells, histamine and imetit induced the expected decreases in BRET (Figure 6A) and increases in specific [35S]GTPγS binding (Figure 6B). In contrast, the inverse agonists thioperamide and clobenpropit significantly increased BRET (Figure 6A) and decreased [35S]GTPγS binding (Figure 6B), thereby confirming the existence of H3R constitutive activity in the system. The protean agonist proxyfan behaved as a partial agonist for both BRET and [35S]GTPγS binding, its effect reproducing that of histamine and imetit but with a lower magnitude (Figure 6A,B).

Figure 6.

Effects of H3-receptor ligands on BRET signals and H3R-mediated [35S]GTPγS binding in HEK 293 cells and rat cerebral cortex. (A) HEK 293 cells expressing H3R-RLuc and H3R-YFP (200–500 fmol per mg protein; sub-maximal BRET) were incubated with the indicated H3R ligands (100 nM) ** p <0.01, *** p < 0.001 versus control (B) For [35S]GTPγS binding assays, membranes from HEK 293 cells expressing the H3R (200–500 fmol per mg protein) were incubated with H3 ligands at 100 nM. Means ± SEM of 8–16 values from two experiments. *** p < 0.001 versus control. (C) Cultured cortical neurons expressing H3R-RLuc and H3R-YFP were incubated with H3 ligands (100 nM) in the absence or presence of proxyfan (10 µM). Means ± SEM of 15–30 values from five separate experiments. ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001 versus control; § p < 0.05; §§§ p < 0.001 versus without proxyfan. (D) [35S]GTPγS binding assay was performed on membranes from the cerebral cortex of adult rats without or with H3 ligands at 100 nM. Means ± SEM of 8–16 values from two experiments. * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; versus control; § p < 0.05; §§ p < 0.05 versus without proxyfan.

In rat cerebral cortex, imetit significantly decreased BRET signals in cortical neurons (Figure 6C) and increased [35S]GTPγS binding to membranes from adult rat cerebral cortex (Figure 6D). In contrast, thioperamide significantly increased BRET signals in neurons (Figure 6C) and decreased [35S]GTPγS binding to membranes by abrogating constitutive activity of the H3R (Figure 6D). In cultured neurons from the cerebral cortex, the protean agonist proxyfan had no effect alone on BRET signals but totally inhibited the opposite effects of imetit and thioperamide, indicating that it was acting as a neutral antagonist on BRET signals [51] (Figure 6C). Proxyfan also behaved as a neutral antagonist on [35S]GTPγS binding to adult membranes. Added alone, it had no effect, but it entirely blocked the opposite effects of imetit or thioperamide (Figure 6D). Since endogenous histamine levels in the medium of cortical neurons were not detectable, and proxyfan did not modify BRET signals when tested alone, it can be concluded that the effect of thioperamide resulted only from inhibition of H3R constitutive activity.

3. Discussion

BRET analysis, co-immunoprecipitation studies, and Western blot experiments confirm that H3 receptors (as many, if not all GPCRs) exist under dimeric forms. In a previous report, H3R dimerization required cross-linking, making its physiological significance doubtful [43]. However, in the present study, spontaneous dimerization was clearly observed not only for recombinant H3Rs expressed in heterologous systems but also for recombinant H3Rs expressed in cerebral neurons as well as for native brain receptors. In addition to dimers, BRET and Western blot signals suggest that H3R also form higher oligomers. However, these oligomeric forms were hardly detected by co-immunoprecipitation, thereby suggesting that H3Rs predominantly exist as dimers.

The physiological existence of “protean” agonism has been reported in cell lines and tissues [36,52]; this pharmacological concept is derived from constitutive activity and introduced by Kenakin on theoretical grounds [53]. We suggest that this protean agonism results from an equilibrium between inactive, ligand-directed active, and constitutively active conformations of the H3R [51]. The main finding of the present study is that BRET is an excellent biosensor that allows for biophysical evidence of these various allosteric H3R conformations.

Indeed, we show that spontaneous BRET signals correspond to constitutively active conformations. Minimal BRET signals correspond to agonist-induced conformations, whereas maximal BRET signals correspond to inactive conformations generated by inverse agonists. These BRET variations, therefore, unravel allosteric conformational changes of H3R dimers. Although the molecular nature of these changes remains unknown, they likely yield changes in the position or orientation of the Luc and YFP moieties [23,54,55,56], i.e., changes in the distance between the two BRET reporters. Both constitutive activity and agonists would promote an “opening” of the H3R dimer, enhancing the distance between protomers and, thereby, decreasing BRET signals. In contrast, the optimal BRET signals observed with inverse agonists indicate that the distance between the C terminal parts of the two protomers becomes minimal within inactive conformations of the receptor dimer. These BRET changes promoted by H3R ligands did not occur in a random fashion but paralleled the pharmacological profile of the receptor in a functional response such as [35S]GTPγS binding in both cells and neurons. Altogether, these data suggest that changes in BRET signals induced by H3R ligands reflect conformational changes linked to the activation process. We previously reported that H3R constitutive activity in cells and tissues required a level of expression higher than 80 fmol per mg protein in order to be detectable in various transductional responses [38,41]. The modulation of BRET signals induced by inverse agonists in neurons was detected at a density as low as ~20 fmol per mg protein, indicating that BRET is a very sensitive approach to detect the constitutive activity of the H3R. The BRET changes occurred with a time course consistent with the association kinetics of the ligands to the brain H3R [57,58]. Interestingly, GTPγS increased BRET signals to the same extent as inverse agonists, indicating that the same inactive conformations could be promoted not only via allosteric transconformations of constitutively active dimers by inverse agonists but also via the uncoupling of the same dimers from G proteins.

In agreement with previous studies on other GPCRs [25,59,60,61], changes in BRET signals induced by agonists or inverse agonists strongly suggest the existence of allosteric cross-talks between the two H3R protomers. In agreement, a previous study established that GPCRs of Class A, to which the H3R belongs [62], operate through the transactivation between the two protomers [8,26]. As reported for the GABAB receptor [63], maximal activation of dimers was ensured by agonist binding to a single protomer. Moreover, the dimer function was regulated by the activity state of the second protomer [26]. Interestingly, as also reported with Class C GPCRs [30,31], inverse agonist and agonist binding to a protomer facilitated and blunted, respectively, the activation of the adjacent protomer [26]. Other studies are also consistent with such an asymmetry between the two protomers in activated Class A GPCRs [1,64]. The increase and decrease in BRET signals that we observe with inverse agonists and agonists/constitutive activity, respectively, strongly suggest a similar scenario for H3R dimers. If confirmed by other approaches, our findings would, therefore, support an asymmetrical activation of H3R dimers, with distinct conformations and functions of the two protomers, the first one being activated by the agonist and the second one serving as a fine-tuner of the first.

The interest in such a scenario is to reconcile or resolve some findings or questions raised by previous studies on GPCRs, including H3Rs. The negative cooperativity, repeatedly observed with H3R agonists in binding experiments with brain membranes and full or partial [3H]-agonists, was initially thought to reflect the existence of two distinct populations of sites with high and low affinity, respectively [57,65,66]. However, it was surprisingly maintained with recombinant receptors from various species [67,68,69,70] and was rather due to the fact that agonist binding to the second protomer blunted agonist binding to the first one. The positive cooperativity observed at recombinant or cerebral H3Rs with antagonists, then reclassified as inverse agonists, remained unexplained and likely reveals the facilitation of agonist binding to the first protomer induced by the binding of inverse agonists to the second protomer [65,69].

Such a scenario, based on the transactivation of two protomers, may also lead us to reconsider the existence that we have proposed—a simple competition between ligand-directed and constitutively active conformations of the H3R for G proteins. The inverse relationship between the efficacy of agonists and the level of constitutive activity that we observed in both native and recombinant H3Rs [41,71] may not only reflect such a competition, as has been assumed so far [51], but also the allosteric interactions between the two protomers. Indeed, this apparent inverse relationship between agonism and constitutive activity may result as well from the fact, as suggested by BRET changes, that agonism at one promoter is progressively blunted when the constitutive activity of the second promoter increases [26]. Such an inverse relationship likely exists between endogenous histamine acting as the physiological H3R agonist and H3R constitutive activity. In fact, after the evidence for a physiological role of H3R constitutive activity in vivo, the role of endogenous histamine in the activation of brain H3Rs was questioned [36]. We suggested that the constitutive activity of H3 autoreceptors located on the cell bodies of histaminergic neurons was higher than that of H3 autoreceptors located on nerve terminals because the effects of inverse agonists on histamine neuron activity in vivo are much higher than their effects on histamine release in vitro [41]. Considering H3Rs as asymmetrical dimers may help us to understand the functional role of histamine, which would be predominant at presynaptic autoreceptors with low constitutive activity of the second protomer but largely blunted at somato-dendritic autoreceptors by the much higher constitutive activity of this second protomer.

The regulation of BRET signals by agonists, inverse agonists, and GTPγS definitely show that the minimal functional signaling units of the H3R are not monomers but dimers coupled to G proteins. However, although their formation by dissociation of dimers during the experiments cannot be entirely ruled out, our findings from Western blot strongly suggest that H3R monomers co-exist with dimers and/or oligomers in the brain and cells. Moreover, if various studies suggest that dimerization of GPCRs is a prerequisite for G-protein activation [72,73,74,75], a single molecule of rhodopsin [76] or β2-adrenergic receptor [77] can efficiently activate G proteins when reconstituted in a nanodisc. However, whether such a coupling of a single protomer occurs in vivo is unknown, and the absence of the second regulatory protomer would be expected to induce an over-activation of the monomer, leading to its rapid internalization. Whatever the presence and function of H3R monomers in the brain, our findings show that they cannot be generated by the dissociation of dimers [22,23,54,78], even though H3R agonists tended to promote the “opening” of the dimer, i.e., decreased BRET signals. Firstly, the unchanged relative affinity between the protomers (unchanged BRET 50 values), as well as the changes of BRETmax in cells, suggest that BRET changes promoted by the H3R ligands reflect transconformations. Secondly, agonists and constitutive activity only partially decrease but do not abolish BRET signals. Finally, using Western blot analysis, we were not able to detect the dissociation of H3R dimers after treatment with agonists (Figure S4). Altogether, our findings are consistent with the consensus that ligand-induced changes in BRET reflect conformational changes within pre-existing dimers and not changes in the equilibrium between monomers and dimers [16,18,25].

The conformational changes observed in intact living cells resulted in a modest (10% to 20%) increase or decrease in BRET signals. However, these changes were highly reproducible and were in the same range as those observed for other Class A GPCRs [79,80]. Moreover, the changes (by 30% to 40%) induced in neurons by H3R ligands were stronger than in fibroblasts. This observation may be attributable to a higher coupling efficacy of the receptor and/or to increased receptor-G protein stoichiometry [81] in neurons than in non-neuronal cells. This better coupling would be accompanied by higher constitutive activity in neurons than in fibroblasts. In agreement, the increase in BRET signals induced by the standard inverse agonist thioperamide was higher in neurons than in cells (+45% versus +21%). Additionally, consistent with higher H3R constitutive activity in neurons than in cells, the protean agonist proxyfan behaved as an agonist in cells but became a neutral antagonist in neurons, not only upon [35S]GTPγS binding but also upon BRET signaling. Moreover, the stronger effect of H3R ligands observed in neurons may also result from more favorable orientations of the two protomers within H3R dimers to detect ligand-induced conformational changes.

Both the high density of H3Rs at the plasma membrane of cells and neurons and the high dimerization observed within the ER show that H3R dimers are formed at the early stages of receptor biosynthesis and trafficking. It has been proposed that this early dimerization occurs to warrant that only properly folded receptors reach their site of action [16]. The extent of the surface expression of GPCRs would be, therefore, dependent on their ability to form dimers and/or oligomers at the pro-receptor stage. The upregulation of GPCRs, including the H3R [37,40,82], induced by sustained treatment with inverse agonists would then result from a decreased constitutive desensitization of the receptor [83,84] and a stabilization of the membrane dimers by inverse agonists [26]. The capacity of H3R protomers to dimerize was, however, not dependent on their intracellular or membrane localization per se because the H3R did not dimerize with the TAAR1 receptor, which is mainly intracellular [85], and hardly dimerized with the D3 receptor, which is predominantly found at the cell membrane [86].

In conclusion, dimeric forms of H3Rs are regulated by agonists and inverse agonists. All our data are consistent with a model in which transactivation between the two protomers of pre-existing dimers underlies H3R activation. The present data also indicate that major regulations induced by the constitutive activity of H3Rs in neurons may occur at three distinct levels: the drug-intrinsic property [51], the receptor itself (dimers), and its associated biological responses [38,40,41]. H3R inverse agonists have entered clinical trials for the treatment of arousal, cognitive, and food intake disorders [35,36]; functional dimers represent, with H3R functional isoforms and species differences, an additional level of complexity that may influence their therapeutic effects.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plasmid Constructs

Rat H3 receptor cDNA, corresponding to the long isoform of the receptor (H3(445)R) without its stop codon, was amplified by PCR. The product was sub-cloned in a frame into the NheI/BglII site of the pEYFP-N1 vector (Clontech, San Jose, CA, USA) encoding the YFP variant of the green fluorescent protein and into the NheI site of the pRL-CMV-RLuc vector (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) to generate H3R-YFP and H3R-RLuc fusion proteins, respectively. Renilla Luciferase (RLuc) and YFP were inserted at the C-terminal end of the receptor. All constructs were checked using direct DNA sequencing.

4.2. Animals

All animal protocols were carried out according to French Government animal experiment regulations and were approved by Animal Ethical Committees (Comité d’Ethique pour l’Expérimentation Animale Orléans CE03) and accredited by the French Ministry of Education and Research (MESR) under national authorization number #C45231412.

4.3. Cell Cultures and Transfections

Cortical neurons were prepared from 18-day-old embryos of male Wistar rats (Janvier, Le Genest-St-Isle, France). Neurons were plated on polyornithin-coated plastic culture dishes for BRET experiments and glass coverslips for immunofluorescence (50,000 cells per cm2). Cultures were grown in neurobasal medium (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA) supplemented with B27 (Invitrogen) and 2 mM L-glutamine. Neurons (8 days in vitro) were transfected with lipofectamine 2000 (InvitrogenTM, Life technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA). HEK 293 cells (European Collection of Cell Cultures, ECACC Ref 85120602 (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA) were transfected using the calcium phosphate precipitation method.

4.4. Membrane Preparations

Forty-eight hours after transfection, membranes from HEK 293 cells were prepared and suspended in the appropriate ice-cold buffer for [125I]iodoproxyfan binding assays (Na2HPO4/KH2PO4 50 mM, pH 7.4), [35S]GTPγS-binding assays (Tris-HCl 50 mM, pH 7.4), Western blot analysis (Tris-HCl 50 mM, pH 7.4, 5 mM EDTA with protease cocktail inhibitor), and BRET assays (Tris-HCl 50 mM, pH 7.4). Crude membranes from rat cerebral cortex, cerebellum, and hypothalamus were prepared [65] and suspended in ice-cold Western blot buffer.

4.5. Immunoprecipitation Assays

HEK 293 cells were co-transfected with C-terminal YFP-fused and N-terminal Xpress-tagged H3Rs. Forty-eight hours after transfection, cells were washed with ice-cold PBS and lysed in buffer containing 50 mM Tris pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM EDTA, and 0.5% Triton X-100 plus protease cocktail inhibitor on ice for 10 min. The lysates were then centrifuged at 10,000× g for 10 min. The supernatants were incubated with protein A-sepharose (GE Healthcare, Chalfont St. Giles, UK) and anti-GFP antibodies (BD Bioscience Clontech, San Jose, CA, USA) overnight at 4 °C. The beads were washed five times with lysis buffer and resuspended in 4-fold concentrated Laemmli buffer (200 mM Tris-HCl pH 6.8, 4% SDS, 40% glycerol, 0.02% bromophenol, βME 0.5 M). Non-specific background was determined by the transfection of N-terminal Xpress-tagged H3Rs without H3R-YFP.

4.6. Western Blots

The cell lysates, immunoprecipitates, or membranes from various rat or mouse brain regions were separated by electrophoresis on SDS/PAGE (8% or 10% gels) or NuPAGE Tris-Acetate 3–8% or 7% precast gels (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc,Rockford, IL, USA). under reducing conditions and transferred on polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Chalfont St. Giles, UK). Blots containing Xpress or YFP-tagged receptors were probed with a mouse anti-Xpress antibody (1:1000, Invitrogen) or a rabbit anti-BD living colors full-length polyclonal antibody (1:3000, BD Biosciences). Immunoblots were also probed with a rabbit anti-H3R polyclonal antibody (1:1000, Livespan Biosciences). Horseradish–peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse or anti-rabbit antibodies (1:33,000 dilutions) were used as secondary antibodies (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). Immunoreactive bands were detected using the Pico or Dura detection kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc (Rockford, IL, USA).

4.7. Binding Assays

For H3R radioligand binding assays, membranes were incubated with [125I]iodoproxyfan as described [65]. For [35S]GTPγS-binding assays, membranes were pretreated and incubated with 0.1 nM [35S]GTPγS and the H3 ligands, as described [38]. Statistical evaluation of the results was performed using one-way ANOVA followed by Student’s Newman-Keuls posthoc test.

4.8. Cell Fractionation Studies

Forty-eight hours after transfection, HEK 293 cells were washed with PBS, scraped off, and lysed with cold hypotonic lysis buffer containing 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 2 mM EDTA, 2 mM EGTA, 6 mM MgCl2, 1 mM PMSF, and protease cocktail inhibitor. Cell suspensions were homogenized and lysates centrifuged at 1000× g for 5 min. The supernatant was collected, and sucrose was added to obtain a final concentration of 0.2 M. Cell lysates were applied to the top of a discontinuous sucrose step gradient (5 mL per step), made at 0.5, 0.9, 1.2, 1.35, 1.5, and 2.0 M sucrose in lysis buffer. The samples were centrifuged (27,000× g for 16 h). Fractions were then submitted to fluorescence/luminescence and BRET analysis. Identification of plasma membranes and ER-enriched fractions was achieved by Western blot using rabbit polyclonal anti-Na+/K+-ATPase (Sigma Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA) and anti-calnexin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) antibodies, respectively.

4.9. Luminescence, Fluorescence, and BRET Assays

Forty-eight hours after transfection, HEK 293 cells or cultured cortical neurons were detached with versene (Invitrogen) and resuspended in HBSS saline buffer (Invitrogen). Intact cells or membranes were distributed in 96-well microplates (Optiplate, Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA, USA) and incubated for 15 min at 25 °C in the absence or presence of the indicated ligands. Coelenterazine H substrate (Interchim) was added at a final concentration of 5 µM, and reading was performed with a Mithras LB 940 multireader (Berthold, Bad Widbad, Germany), which allows the sequential integration of luminescence signals detected with two filter settings (RLuc filter, 485 ± 10 nm; YFP filter, 530 ± 12 nm). Emission signals at 530 nm were divided by emission signals at 485 nm. The difference between this emission ratio, obtained with co-transfected RLuc and YFP fusion proteins, and that obtained with the RLuc fusion protein alone is defined as the BRET ratio. The results are expressed in milliBRET units (mBU, with 1 mBU corresponding to the BRET ratio values multiplied by 1000). BRETmax is the maximal BRET signal obtained in milliBRET units, and BRET50 represents the ratio of acceptor and donor receptors (acceptor/donor), yielding 50% of the maximum BRET signal. Statistical evaluation of the results was performed using one-way ANOVA followed by the Newman-Keuls posthoc test or two-way ANOVA followed by a non-parametric Wilcoxon/Mann–Whitney test.

Fluorescence was measured in black 96-well plates (Optiplate, Perkin Elmer) using the Mithras LB 940 reader (Berthold) with an excitation filter at 480 nm and an emission filter at 510 nm (gain, 1; photomultiplicator tube, 2000 V; time, 1.0 s). Total luminescence of cells was determined in white 96-well plates (Otiplate, Perkin Elmer). Background luminescence and fluorescence determined in wells containing untransfected cells were subtracted.

4.10. Fluorescence Microscopy

Neurons cultured for 8 days were transfected using lipofectamine 2000 with the plasmid encoding H3R-YFP. Cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde two days after transfection. Images were acquired using a TCS-SP2 confocal laser scanning microscope (Leica Biosystems, Nanterre, France).

4.11. Analysis of Data

For BRET saturation or modulation, the total curves were analyzed with an iterative least-squares method derived from that of Parker and Waud [87]. Computer analysis was performed by non-linear regression using a one-site cooperative model. The method provided estimates for EC50 values, BRETmax and BRET50 values, and their SEMs. Statistical evaluation of the results was performed using one-way ANOVA, followed by Student’s Newman-Keuls posthoc test or by two-way ANOVA.

4.12. Radiochemicals and Drugs

[125I]Iodoproxyfan (2000 Ci/mmol) was prepared as described [88,89]. [35S]GTPγS (1250 Ci/mmol) was from Perkin Elmer Life Sciences (Boston, MA, USA). Clobenpropit was from Tocris (Bristol, UK). R-α-methylhistamine, ciproxifan, and proxyfan were provided by W. Schunack (Freie Universität Berlin, Berlin, Germany). Histamine, imetit, thioperamide, and isoproterenol were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Saint Quentin Fallavier, France). All other chemicals were from commercial sources and were of the highest purity available. Interventionary studies involving animals or humans and other studies that require ethical approval must list the authority that provides the approval and the corresponding ethical approval code.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank S. Marullo and H. Issafras for their help in setting up BRET experiments. We also thank C. Chabret for her contribution to Western blot analysis, A. Burban for her contribution to neuronal cultures, and E. Davenas for immunocytochemistry experiments. We thank F. Gbahou for the critical reading of the manuscript and A. Cherfouh for his help in statistical analysis.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ijms221910638/s1, Figure S1: Deglycosylation of H3R-YFP with endoglycosidase H (Endo H) and peptide-N-glycosidase (PNGase F); Figure S2: Characterization of the H3 receptor antibody by immunolabeling in Cos7-transfected cells; Figure S3: Influence of H3R receptor density on BRET signals; Figure S4: Analysis of ligand-promoted changes in dimerization states.

Author Contributions

C.E.K. and S.M.-L. designed, performed, and analyzed the BRET experiments. L.C. and S.M.-L. provided the WB data. J.-M.A. validated data and reviewed and edited the manuscript. C.E.K. reviewed and edited the manuscript. S.M.-L. supervised the study and wrote the original draft. S.M.-L. and J.-M.A. were involved in funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by CNRS, INSERM, the Region Centre Val de Loire (PAIN), and the University of Orléans. C.E.K. was the recipient of a Ph.D. fellowship from the Region Centre Val de Loire.

Institutional Review Board Statement

All animal protocols were carried out according to French Government animal experiment regulations and were approved by Animal Ethical Committees (Comité d’Ethique pour l’Expérimentation Animale Orléans CE03) and accredited by the French Ministry of Education and Research (MESR) under national authorization number #C45231412.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data included in the study are presented in the manuscript. The corresponding author bears as guarantor for data validation.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Albizu L., Cottet M., Kralikova M., Stoev S., Seyer R., Brabet I., Roux T., Bazin H., Bourrier E., Lamarque L., et al. Time-resolved FRET between GPCR ligands reveals oligomers in native tissues. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2010;6:587–594. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bai M. Dimerization of G-protein-coupled receptors: Roles in signal transduction. Cell Signal. 2004;16:175–186. doi: 10.1016/S0898-6568(03)00128-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ciruela F., Casado V., Rodrigues R.J., Lujan R., Burgueno J., Canals M., Borycz J., Rebola N., Goldberg S.R., Mallol J., et al. Presynaptic control of striatal glutamatergic neurotransmission by adenosine A1-A2A receptor heteromers. J. Neurosci. 2006;26:2080–2087. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3574-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fotiadis D., Liang Y., Filipek S., Saperstein D.A., Engel A., Palczewski K. Atomic-force microscopy: Rhodopsin dimers in native disc membranes. Nature. 2003;421:127–128. doi: 10.1038/421127a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pin J.P., Neubig R., Bouvier M., Devi L., Filizola M., Javitch J.A., Lohse M.J., Milligan G., Palczewski K., Parmentier M., et al. International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. LXVII. Recommendations for the recognition and nomenclature of G protein-coupled receptor heteromultimers. Pharmacol. Rev. 2007;59:5–13. doi: 10.1124/pr.59.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Terrillon S., Bouvier M. Roles of G-protein-coupled receptor dimerization. EMBO Rep. 2004;5:30–34. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Angers S., Salahpour A., Bouvier M. Dimerization: An emerging concept for G protein-coupled receptor ontogeny and function. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2002;42:409–435. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.42.091701.082314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bourque K., Jones-Tabah J., Devost D., Clarke P.B.S., Hébert T.E. Exploring functional consequences of GPCR oligomerization requires a different lens. Prog. Mol. Biol. Transl. Sci. 2020;169:181–211. doi: 10.1016/bs.pmbts.2019.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferré S., Ciruela F., Casadó V., Pardo L. Oligomerization of G protein-coupled receptors: Still doubted? Prog. Mol. Biol. Transl. Sci. 2020;169:297–321. doi: 10.1016/bs.pmbts.2019.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gomes I., Jordan B.A., Gupta A., Rios C., Trapaidze N., Devi L.A. G protein coupled receptor dimerization: Implications in modulating receptor function. J. Mol. Med. 2001;79:226–242. doi: 10.1007/s001090100219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Milligan G. A day in the life of a G protein-coupled receptor: The contribution to function of G protein-coupled receptor dimerization. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2008;153((Suppl. 1)):S216–S229. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grant M., Collier B., Kumar U. Agonist-dependent dissociation of human somatostatin receptor 2 dimers: A role in receptor trafficking. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:36179–36183. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407310200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rocheville M., Lange D.C., Kumar U., Sasi R., Patel R.C., Patel Y.C. Subtypes of the somatostatin receptor assemble as functional homo- and heterodimers. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:7862–7869. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.11.7862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vila-Coro A.J., Mellado M., Martin de Ana A., Lucas P., del Real G., Martinez A.C., Rodriguez-Frade J.M. HIV-1 infection through the CCR5 receptor is blocked by receptor dimerization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:3388–3393. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.7.3388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhu C.C., Cook L.B., Hinkle P.M. Dimerization and phosphorylation of thyrotropin-releasing hormone receptors are modulated by agonist stimulation. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:28228–28237. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204221200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bulenger S., Marullo S., Bouvier M. Emerging role of homo- and heterodimerization in G-protein-coupled receptor biosynthesis and maturation. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2005;26:131–137. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2005.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mandrika I., Petrovska R., Klovins J. Evidence for constitutive dimerization of niacin receptor subtypes. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2010;395:281–287. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Milligan G. G protein-coupled receptor dimerization: Function and ligand pharmacology. Mol. Pharmacol. 2004;66:1–7. doi: 10.1124/mol.104.000497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nobles M., Benians A., Tinker A. Heterotrimeric G proteins precouple with G protein-coupled receptors in living cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:18706–18711. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504778102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dinger M.C., Bader J.E., Kobor A.D., Kretzschmar A.K., Beck-Sickinger A.G. Homodimerization of neuropeptide y receptors investigated by fluorescence resonance energy transfer in living cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:10562–10571. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205747200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McVey M., Ramsay D., Kellett E., Rees S., Wilson S., Pope A.J., Milligan G. Monitoring receptor oligomerization using time-resolved fluorescence resonance energy transfer and bioluminescence resonance energy transfer. The human delta -opioid receptor displays constitutive oligomerization at the cell surface, which is not regulated by receptor occupancy. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:14092–14099. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008902200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Terrillon S., Durroux T., Mouillac B., Breit A., Ayoub M.A., Taulan M., Jockers R., Barberis C., Bouvier M. Oxytocin and vasopressin V1a and V2 receptors form constitutive homo- and heterodimers during biosynthesis. Mol. Endocrinol. 2003;17:677–691. doi: 10.1210/me.2002-0222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Couturier C., Jockers R. Activation of the leptin receptor by a ligand-induced conformational change of constitutive receptor dimers. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:26604–26611. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302002200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Damian M., Martin A., Mesnier D., Pin J.P., Baneres J.L. Asymmetric conformational changes in a GPCR dimer controlled by G-proteins. EMBO J. 2006;25:5693–5702. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guo W., Shi L., Filizola M., Weinstein H., Javitch J.A. Crosstalk in G protein-coupled receptors: Changes at the transmembrane homodimer interface determine activation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:17495–17500. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508950102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Han Y., Moreira I.S., Urizar E., Weinstein H., Javitch J.A. Allosteric communication between protomers of dopamine class A GPCR dimers modulates activation. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2009;5:688–695. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mesnier D., Baneres J.L. Cooperative conformational changes in a G-protein-coupled receptor dimer, the leukotriene B4 receptor BLT1. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:49664–49670. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404941200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.O’Dowd B.F., Ji X., Alijaniaram M., Rajaram R.D., Kong M.M., Rashid A., Nguyen T., George S.R. Dopamine receptor oligomerization visualized in living cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:37225–37235. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504562200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Urizar E., Montanelli L., Loy T., Bonomi M., Swillens S., Gales C., Bouvier M., Smits G., Vassart G., Costagliola S. Glycoprotein hormone receptors: Link between receptor homodimerization and negative cooperativity. EMBO J. 2005;24:1954–1964. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goudet C., Kniazeff J., Hlavackova V., Malhaire F., Maurel D., Acher F., Blahos J., Prezeau L., Pin J.P. Asymmetric functioning of dimeric metabotropic glutamate receptors disclosed by positive allosteric modulators. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:24380–24385. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502642200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hlavackova V., Goudet C., Kniazeff J., Zikova A., Maurel D., Vol C., Trojanova J., Prezeau L., Pin J.P., Blahos J. Evidence for a single heptahelical domain being turned on upon activation of a dimeric GPCR. EMBO J. 2005;24:499–509. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Arrang J.M., Garbarg M., Lancelot J.C., Lecomte J.M., Pollard H., Robba M., Schunack W., Schwartz J.C. Highly potent and selective ligands for histamine H3-receptors. Nature. 1987;327:117–123. doi: 10.1038/327117a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Arrang J.M., Garbarg M., Schwartz J.C. Auto-inhibition of brain histamine release mediated by a novel class (H3) of histamine receptor. Nature. 1983;302:832–837. doi: 10.1038/302832a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pillot C., Heron A., Cochois V., Tardivel-Lacombe J., Ligneau X., Schwartz J.C., Arrang J.M. A detailed mapping of the histamine H3 receptor and its gene transcripts in rat brain. Neuroscience. 2002;114:173–193. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4522(02)00135-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ghamari N., Zarei O., Arias-Montaño J.A., Reiner D., Dastmalchi S., Stark H., Hamzeh-Mivehroud M. Histamine H(3) receptor antagonists/inverse agonists: Where do they go? Pharmacol. Ther. 2019;200:69–84. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2019.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Arrang J.M., Morisset S., Gbahou F. Constitutive activity of the histamine H3 receptor. Trends Pharm. Sci. 2007;28:350–357. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2007.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Morisset S., Traiffort E., Arrang J.M., Schwartz J.C. Changes in histamine H3 receptor responsiveness in mouse brain. J. Neurochem. 2000;74:339–346. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0740339.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rouleau A., Ligneau X., Tardivel-Lacombe J., Morisset S., Gbahou F., Schwartz J.C., Arrang J.M. Histamine H3-receptor-mediated [35S]GTP gamma[S] binding: Evidence for constitutive activity of the recombinant and native rat and human H3 receptors. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2002;135:383–392. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wieland K., Bongers G., Yamamoto Y., Hashimoto T., Yamatodani A., Menge W.M., Timmerman H., Lovenberg T.W., Leurs R. Constitutive activity of histamine H3 receptors stably expressed in SK-N-MC cells: Display of agonism and inverse agonism by H3 antagonists. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2001;299:908–914. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Humbert-Claude M., Morisset S., Gbahou F., Arrang J.M. Histamine H3 and dopamine D2 receptor-mediated [35S]GTPgamma[S] binding in rat striatum: Evidence for additive effects but lack of interactions. Biochem. Pharm. 2007;73:1172–1181. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2007.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Morisset S., Rouleau A., Ligneau X., Gbahou F., Tardivel-Lacombe J., Stark H., Schunack W., Ganellin C.R., Schwartz J.C., Arrang J.M. High constitutive activity of native H3 receptors regulates histamine neurons in brain. Nature. 2000;408:860–864. doi: 10.1038/35048583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bakker R.A., Lozada A.F., van Marle A., Shenton F.C., Drutel G., Karlstedt K., Hoffmann M., Lintunen M., Yamamoto Y., van Rijn R.M., et al. Discovery of naturally occurring splice variants of the rat histamine H3 receptor that act as dominant-negative isoforms. Mol. Pharmacol. 2006;69:1194–1206. doi: 10.1124/mol.105.019299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shenton F.C., Hann V., Chazot P.L. Evidence for native and cloned H3 histamine receptor higher oligomers. Inflamm. Res. 2005;54((Suppl. 1)):S48–S49. doi: 10.1007/s00011-004-0422-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bacart J., Corbel C., Jockers R., Bach S., Couturier C. The BRET technology and its application to screening assays. Biotechnol. J. 2008;3:311–324. doi: 10.1002/biot.200700222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bouvier M., Heveker N., Jockers R., Marullo S., Milligan G. BRET analysis of GPCR oligomerization: Newer does not mean better. Nat. Methods. 2007;4:3–4. doi: 10.1038/nmeth0107-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.El Khamlichi C., Reverchon-Assadi F., Hervouet-Coste N., Blot L., Reiter E., Morisset-Lopez S. Bioluminescence Resonance Energy Transfer as a Method to Study Protein-Protein Interactions: Application to G Protein Coupled Receptor Biology. Molecules. 2019;24:537. doi: 10.3390/molecules24030537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.James J.R., Oliveira M.I., Carmo A.M., Iaboni A., Davis S.J. A rigorous experimental framework for detecting protein oligomerization using bioluminescence resonance energy transfer. Nat. Methods. 2006;3:1001–1006. doi: 10.1038/nmeth978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Garbarg M., Arrang J.M., Rouleau A., Ligneau X., Tuong M.D., Schwartz J.C., Ganellin C.R. S-[2-(4-imidazolyl)ethyl]isothiourea, a highly specific and potent histamine H3 receptor agonist. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1992;263:304–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ligneau X., Lin J., Vanni-Mercier G., Jouvet M., Muir J.L., Ganellin C.R., Stark H., Elz S., Schunack W., Schwartz J. Neurochemical and behavioral effects of ciproxifan, a potent histamine H3-receptor antagonist. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1998;287:658–666. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Van der Goot H., Schepers M., Sterk G., Timmerman H. Isothiourea analogues of histamine as potent agonists or antagonists of the histamine H3 receptor. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 1992;27:511–517. doi: 10.1016/0223-5234(92)90185-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gbahou F., Rouleau A., Morisset S., Parmentier R., Crochet S., Lin J.S., Ligneau X., Tardivel-Lacombe J., Stark H., Schunack W., et al. Protean agonism at histamine H3 receptors in vitro and in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:11086–11091. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1932276100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mancini I., Brusa R., Quadrato G., Foglia C., Scandroglio P., Silverman L., Tulshian D., Reggiani A., Beltramo M. Constitutive activity of cannabinoid-2 (CB2) receptors plays an essential role in the protean agonism of (+)AM1241 and L768242. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2009;158:382–391. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00154.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kenakin T. Pharmacological proteus? Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1995;16:256–258. doi: 10.1016/S0165-6147(00)89037-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ayoub M.A., Couturier C., Lucas-Meunier E., Angers S., Fossier P., Bouvier M., Jockers R. Monitoring of ligand-independent dimerization and ligand-induced conformational changes of melatonin receptors in living cells by bioluminescence resonance energy transfer. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:21522–21528. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200729200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mercier J.F., Salahpour A., Angers S., Breit A., Bouvier M. Quantitative assessment of beta 1- and beta 2-adrenergic receptor homo- and heterodimerization by bioluminescence resonance energy transfer. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:44925–44931. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205767200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhou Y., Meng J., Xu C., Liu J. Multiple GPCR Functional Assays Based on Resonance Energy Transfer Sensors. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021;9:611443. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2021.611443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Arrang J.M., Roy J., Morgat J.L., Schunack W., Schwartz J.C. Histamine H3 receptor binding sites in rat brain membranes: Modulations by guanine nucleotides and divalent cations. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1990;188:219–227. doi: 10.1016/0922-4106(90)90005-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.West R.E., Jr., Zweig A., Granzow R.T., Siegel M.I., Egan R.W. Biexponential kinetics of (R)-alpha-[3H]methylhistamine binding to the rat brain H3 histamine receptor. J. Neurochem. 1990;55:1612–1616. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1990.tb04946.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Albizu L., Balestre M.N., Breton C., Pin J.P., Manning M., Mouillac B., Barberis C., Durroux T. Probing the existence of G protein-coupled receptor dimers by positive and negative ligand-dependent cooperative binding. Mol. Pharmacol. 2006;70:1783–1791. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.025684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sleno R., Hébert T.E. The Dynamics of GPCR Oligomerization and Their Functional Consequences. Int. Rev. Cell Mol. Biol. 2018;338:141–171. doi: 10.1016/bs.ircmb.2018.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Springael J.Y., Le Minh P.N., Urizar E., Costagliola S., Vassart G., Parmentier M. Allosteric modulation of binding properties between units of chemokine receptor homo- and hetero-oligomers. Mol. Pharmacol. 2006;69:1652–1661. doi: 10.1124/mol.105.019414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lovenberg T.W., Roland B.L., Wilson S.J., Jiang X., Pyati J., Huvar A., Jackson M.R., Erlander M.G. Cloning and functional expression of the human histamine H3 receptor. Mol. Pharmacol. 1999;55:1101–1107. doi: 10.1124/mol.55.6.1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kaupmann K., Malitschek B., Schuler V., Heid J., Froestl W., Beck P., Mosbacher J., Bischoff S., Kulik A., Shigemoto R., et al. GABAB-receptor subtypes assemble into functional heteromeric complexes. Nature. 1998;396:683–687. doi: 10.1038/25360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mancia F., Assur Z., Herman A.G., Siegel R., Hendrickson W.A. Ligand sensitivity in dimeric associations of the serotonin 5HT2c receptor. EMBO Rep. 2008;9:363–369. doi: 10.1038/embor.2008.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ligneau X., Garbarg M., Vizuete M.L., Diaz J., Purand K., Stark H., Schunack W., Schwartz J.C. [125I]iodoproxyfan, a new antagonist to label and visualize cerebral histamine H3 receptors. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1994;271:452–459. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Clark E.A., Hill S.J. Differential effect of sodium ions and guanine nucleotides on the binding of thioperamide and clobenpropit to histamine H3-receptors in rat cerebral cortical membranes. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1995;114:357–362. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb13234.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ligneau X., Morisset S., Tardivel-Lacombe J., Gbahou F., Ganellin C.R., Stark H., Schunack W., Schwartz J.C., Arrang J.M. Distinct pharmacology of rat and human histamine H3 receptors: Role of two amino acids in the third transmembrane domain. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2000;131:1247–1250. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Morisset S., Sasse A., Gbahou F., Heron A., Ligneau X., Tardivel-Lacombe J., Schwartz J.C., Arrang J.M. The rat H3 receptor: Gene organization and multiple isoforms. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2001;280:75–80. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.4073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rouleau A., Heron A., Cochois V., Pillot C., Schwartz J.C., Arrang J.M. Cloning and expression of the mouse histamine H3 receptor: Evidence for multiple isoforms. J. Neurochem. 2004;90:1331–1338. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02606.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Uveges A.J., Kowal D., Zhang Y., Spangler T.B., Dunlop J., Semus S., Jones P.G. The role of transmembrane helix 5 in agonist binding to the human H3 receptor. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2002;301:451–458. doi: 10.1124/jpet.301.2.451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Arrang J.M., Garbarg M., Schwartz J.C. Autoregulation of histamine release in brain by presynaptic H3-receptors. Neuroscience. 1985;15:553–562. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(85)90233-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Baneres J.L., Parello J. Structure-based analysis of GPCR function: Evidence for a novel pentameric assembly between the dimeric leukotriene B4 receptor BLT1 and the G-protein. J. Mol. Biol. 2003;329:815–829. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(03)00439-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Filipek S., Krzysko K.A., Fotiadis D., Liang Y., Saperstein D.A., Engel A., Palczewski K. A concept for G protein activation by G protein-coupled receptor dimers: The transducin/rhodopsin interface. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2004;3:628–638. doi: 10.1039/b315661c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gomes I., Ayoub M.A., Fujita W., Jaeger W.C., Pfleger K.D.G., Devi L.A. G Protein–Coupled Receptor Heteromers. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2016;56:403–425. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-011613-135952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Liang Y., Fotiadis D., Filipek S., Saperstein D.A., Palczewski K., Engel A. Organization of the G protein-coupled receptors rhodopsin and opsin in native membranes. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:21655–21662. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302536200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bayburt T.H., Leitz A.J., Xie G., Oprian D.D., Sligar S.G. Transducin activation by nanoscale lipid bilayers containing one and two rhodopsins. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:14875–14881. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M701433200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Whorton M.R., Bokoch M.P., Rasmussen S.G., Huang B., Zare R.N., Kobilka B., Sunahara R.K. A monomeric G protein-coupled receptor isolated in a high-density lipoprotein particle efficiently activates its G protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:7682–7687. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611448104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Bedini A. Bioluminescence Resonance Energy Transfer (BRET) to Detect the Interactions Between Kappa Opioid Receptor and Nonvisual Arrestins. In: Spampinato S.M., editor. Opioid Receptors: Methods and Protocols. Springer US; New York, NY, USA: 2021. pp. 45–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Babcock G.J., Farzan M., Sodroski J. Ligand-independent dimerization of CXCR4, a principal HIV-1 coreceptor. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:3378–3385. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210140200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Levoye A., Balabanian K., Baleux F., Bachelerie F., Lagane B. CXCR7 heterodimerizes with CXCR4 and regulates CXCL12-mediated G protein signaling. Blood. 2009;113:6085–6093. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-12-196618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kenakin T. Differences between natural and recombinant G protein-coupled receptor systems with varying receptor/G protein stoichiometry. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1997;18:456–464. doi: 10.1016/S0165-6147(97)01136-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Pan J.B., Yao B.B., Miller T.R., Kroeger P.E., Bennani Y.L., Komater V.A., Esbenshade T.A., Hancock A.A., Decker M.W., Fox G.B. Evidence for tolerance following repeated dosing in rats with ciproxifan, but not with A-304121. Life Sci. 2006;79:1366–1379. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2006.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Pei G., Samama P., Lohse M., Wang M., Codina J., Lefkowitz R.J. A constitutively active mutant beta 2-adrenergic receptor is constitutively desensitized and phosphorylated. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1994;91:2699–2702. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.7.2699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Smit M.J., Leurs R., Alewijnse A.E., Blauw J., Van Nieuw Amerongen G.P., Van De Vrede Y., Roovers E., Timmerman H. Inverse agonism of histamine H2 antagonist accounts for upregulation of spontaneously active histamine H2 receptors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1996;93:6802–6807. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.13.6802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Bunzow J.R., Sonders M.S., Arttamangkul S., Harrison L.M., Zhang G., Quigley D.I., Darland T., Suchland K.L., Pasumamula S., Kennedy J.L., et al. Amphetamine, 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine, lysergic acid diethylamide, and metabolites of the catecholamine neurotransmitters are agonists of a rat trace amine receptor. Mol. Pharmacol. 2001;60:1181–1188. doi: 10.1124/mol.60.6.1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Diaz J., Pilon C., Le Foll B., Gros C., Triller A., Schwartz J.C., Sokoloff P. Dopamine D3 receptors expressed by all mesencephalic dopamine neurons. J. Neurosci. 2000;20:8677–8684. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-23-08677.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Parker R.B., Waud D.R. Pharmacological estimation of drug-receptor dissociation constants. Statistical evaluation. I. Agonists. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1971;177:1–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Krause M., Stark H., Schunack W. Iododestannylation: An improved synthesis of [125I]iodoproxyfan, a specific radioligand of the histamine H3 receptor. J. Label. Comp. Radiopharm. 1997;39:601–606. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1344(199707)39:7<601::AID-JLCR2>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Davenas E., Rouleau A., Morisset S., Arrang J.M. Autoregulation of McA-RH7777 hepatoma cell proliferation by histamine H3 receptors. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2008;326:406–413. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.135368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data included in the study are presented in the manuscript. The corresponding author bears as guarantor for data validation.