Abstract

It has been previously proposed that the transcription complexes TFIID and SAGA comprise a histone octamer-like substructure formed from a heterotetramer of H4-like human hTAFII80 (or its Drosophila melanogaster dTAFII60 and yeast [Saccharomyces cerevisiae] yTAFII60 homologues) and H3-like hTAFII31 (dTAFII40 and yTAFII17) along with two homodimers of H2B-like hTAFII20 (dTAFII30α and yTAFII61/68). However, it has not been formally shown that hTAFII20 heterodimerizes via its histone fold. By two-hybrid analysis with yeast and biochemical characterization of complexes formed by coexpression in Escherichia coli, we showed that hTAFII20 does not homodimerize but heterodimerizes with hTAFII135. Heterodimerization requires the α2 and α3 helices of the hTAFII20 histone fold and is abolished by mutations in the hydrophobic face of the hTAFII20 α2 helix. Interaction with hTAFII20 requires a domain of hTAFII135 which shows sequence homology to H2A. This domain also shows homology to the yeast SAGA component ADA1, and we show that yADA1 heterodimerizes with the histone fold region of yTAFII61/68, the yeast hTAFII20 homologue. These results are indicative of a histone fold type of interaction between hTAFII20-hTAFII135 and yTAFII68-yADA1, which therefore constitute novel histone-like pairs in the TFIID and SAGA complexes.

Transcription factor TFIID is one of the general factors required for accurate and regulated initiation by RNA polymerase II. TFIID comprises the TATA-binding protein (TBP) and TBP-associated factors (TAFIIs) (4, 7). The cDNAs encoding many human TAFIIs (hTAFIIs) have been isolated, revealing a striking sequence conservation with yeast and Drosophila TAFIIs (yTAFIIs and dTAFIIs, respectively) (25, 27, 35, 36, 40, and references therein). A subset of TAFIIs are present not only in TFIID but also in the SAGA, PCAF, STAGA, and TFTC complexes (6, 16, 32, 43, 52; reviewed in references 18, 19, and 53).

TAFII function in living cells has been studied genetically in yeast and by transfection experiments with mammalian cells. In yeast, a variable requirement for TAFIIs has been found. Temperature-sensitive mutations in yTAFII145 result in cell cycle arrest and lethality, but the expression of only a small number of genes is affected (23, 51). In contrast, tightly temperature-sensitive mutations in yTAFII17, yTAFII25, yTAFII60, or yTAFII61/68 which are also present in the SAGA complex have a more dramatic effect, in which the transcription of the majority of yeast genes is affected (1, 38, 39, 41, 46). An increasing body of results also shows that hTAFII28, hTAFII135, and hTAFII105 can act as specific transcriptional coactivators for nuclear receptors and other activators in mammalian cells (10, 26, 33–35, 45, 55).

It has been proposed that the TFIID, PCAF, and SAGA complexes contain a histone octamer-like substructure (8, 20–22, 54). This is suggested by the fact that three TAFIIs show obvious sequence homology to histones H4, H3, and H2B: hTAFII80 (dTAFII60 and yTAFII60), hTAFII31 (dTAFII40 and yTAFII17), and hTAFII20 (dTAFII30α and yTAFII61/68), respectively. Structural studies show that dTAFII60 and dTAFII40 interact via a histone fold and form an H3-H4-like heterotetramer, although dTAFII40 does not contain an αN helix characteristic of H3 (2, 30, 54). In the mammalian PCAF complex, hTAFII80 is replaced by another histone fold-containing protein, PAF65α, which forms a histone pair with hTAFII31 (43). hTAFII20 shows homology to H2B and may contain an αC helix characteristic of H2B (30). In the absence of an obvious H2A-like TAFII, the histone octamer-like structure is postulated to comprise an hTAFII80 (PAF65α)/hTAFII31 heterotetramer and two hTAFII20 homodimers.

Although it was not originally noted in sequence comparisons, hTAFII28 and hTAFII18 are also histone-like TAFIIs since they interact via a histone fold motif to form a heterodimer (5, 11). hTAFII28 is atypical, since it shows equivalent sequence homology to H3, H4, and H2B, but structurally resembles H3 due to the presence of an αN helix. hTAFII18 shows sequence homology to H4 but is likely to contain an αC helix typical of H2B. Furthermore, the SAGA, PCAF, TFTC, and STAGA component SPT3 shows extensive sequence homology to the histone fold motifs of both hTAFII18 and hTAFII28 in its N- and C-terminal regions, respectively (5, 36). These two regions are separated by a long linker domain which would allow SPT3 to form a histone-like pair by intramolecular interactions. Therefore, while the existence of these additional histone-like pairs in the TFIID, PCAF, TFTC, and SAGA complexes does not rule out the existence of a histone octamer-like structure, this simple model cannot account for all of the histone pairs seen in these complexes.

One essential postulate of the original octamer-like model was the presence of two hTAFII20 homodimers in TFIID, yet hTAFII20 has not been shown to homodimerize via its histone fold motif. In this report, we show that hTAFII20 does not form homodimers in either yeast two-hybrid assays or Escherichia coli. Instead, coexpressed hTAFII20 and hTAFII135 interact in two-hybrid assays and this interaction requires the histone fold region of hTAFII20 and a conserved region in hTAFII135. Interaction with hTAFII135 is abolished by mutation of the hydrophobic amino acids in the α2 helix of the hTAFII20 histone fold, which in histone pairs typically form the hydrophobic interface with the heterodimeric partner. Coexpression of hTAFII135 in E. coli solubilizes the hTAFII20 histone fold and leads to the formation of a heterodimeric complex. Therefore, our results show that, rather than forming homodimers, hTAFII20 heterodimerizes with hTAFII135.

In contrast, yTAFII68, the hTAFII20 homologue, does not interact with hTAFII135. Analysis of hTAFII135 interaction with hTAFII20/yTAFII68 chimeras locates determinants for partner specificity in the α2-L2-α3 segment of the histone fold. Finally, we demonstrate that the SAGA component yADA1 contains a domain with homology to hTAFII135 which mediates its heterodimerization with the histone fold of yTAFII68 in two-hybrid assays and in E. coli coexpression. This shared hTAFII135/ADA1 domain shows homology with the histone fold region of H2A. These results show the existence of additional histone-like pairs in the both the TFIID and SAGA complexes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Construction of recombinant plasmids.

Two-hybrid expression vectors and bacterial expression vectors were constructed by PCR using primers with the appropriate restriction sites, and constructs were verified by automated DNA sequencing. Details of constructions are available on request. LexA fusions were constructed in the multicopy vector pBTM116 containing the TRP1 marker, and the VP16 fusions were constructed in the multicopy vector pASV3 containing the LEU2 marker (28, 29).

Yeast strains and two-hybrid assays.

The vectors expressing the LexA-TAFII and VP16-TAFII fusion proteins were sequentially transformed into Saccharomyces cerevisiae L40 (49) [MATa trp1-901 leu2-3,112 his 3-Δ200 ade2 LYS2::(LexAop)4-HIS3, URA3::(LexAop)8-LacZ] by the lithium acetate technique (14). Transformants were selected on Trp− Leu− plates. For qualitative detection of β-galactosidase activity, yeast colonies were replica plated on a nitrocellulose filter and lysed by freezing in liquid nitrogen and the filter was then placed on filter paper presoaked with X-Gal (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside) to turn positive colonies blue. Quantitative β-galactosidase assays of individual L40 transformants were determined as previously described (50). Reproducible results were obtained in several independent experiments, and the results of typical experiments are shown in the figures.

Coexpression in E. coli.

PCR was used to clone the hTAFII20 histone fold region (and derivatives) between the NdeI and BamHI sites of the pET15b vector to generate a six-histidine-tagged fusion protein. Deletion mutant forms of the TAFII135 CR-II domain and yADA1(259–359) were cloned in a modified version of the vector pACYC184 (New England BioLabs) (unpublished data). Plasmid pairs were introduced into E. coli BL21 (DE3), and double transformants were selected on plates containing ampicillin and chloramphenicol. Bacteria were amplified to an optical density at 600 nm of 0.45 and induced for 4 h at 25°C with 1 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG). Cell were lysed by sonication in buffer (25 mM Tris HCl [pH 6.0], 0.4 M NaCl), and the soluble fraction was collected after centrifugation at 14,000 rpm for 20 min at 4°C in an Eppendorf centrifuge. Aliquots of the soluble fraction from a 10-ml bacterial culture were then incubated with 50 μl of Co2+ beads (TALON metal affinity resin; Clontech) for 30 min at 4°C. The beads were washed three times with 1 ml of lysis buffer and then resuspended in Laemmli buffer. One-fifth of the bound proteins were analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and staining with Coomassie brilliant blue as shown in the figures. Interactions with the glutathione S-transferase (GST) derivatives were performed by using glutathione-Sepharose (Pharmacia). Binding and washing were done essentially as described above. For gel filtration, the hTAFII20(57–128)–hTAFII135(870–952) complex was purified by chromatography on Co2+ beads from 1.5 liters of culture. The eluted material was loaded on a Superdex 75 column (Pharmacia), and molecular mass was determined by comparing its elution time with that of known standards in the gel filtration standard kit from Bio-Rad.

RESULTS

The histone fold region of hTAFII20 interacts with hTAFII135.

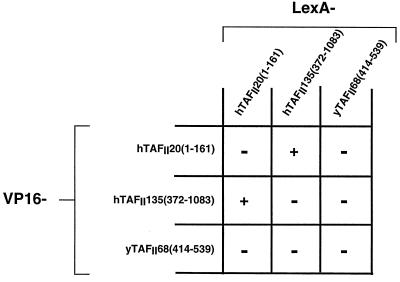

To test its ability to form homodimers, full-length hTAFII20(1–161) was fused to either the LexA DNA-binding domain (DBD) or the VP16 acidic activation domain (AAD) (see Materials and Methods and Fig. 1 and 2B). Both expression vectors were transformed into yeast strain L40, which harbors a LexA-responsive β-galactosidase gene. Interaction of the two proteins was evaluated from expression of the LexA-dependent β-galactosidase reporter (see Materials and Methods). In such experiments, coexpression of LexA-hTAFII20 and VP16-hTAFII20 did not lead to significant activation of the β-galactosidase reporter gene (summarized in Fig. 1), showing that hTAFII20 did not homodimerize in two-hybrid assays.

FIG. 1.

Summary of the results obtained with LexA- and VP16 AAD-TAFII fusions in yeast two-hybrid assays. The combinations used are indicated along with the amino acid coordinates of the TAFII segments included in each fusion. A plus sign indicates β-galactosidase activity significantly higher than that seen with the appropriate LexA or VP16 control, and a minus sign indicates background levels (see Fig. 2C and 4B for examples).

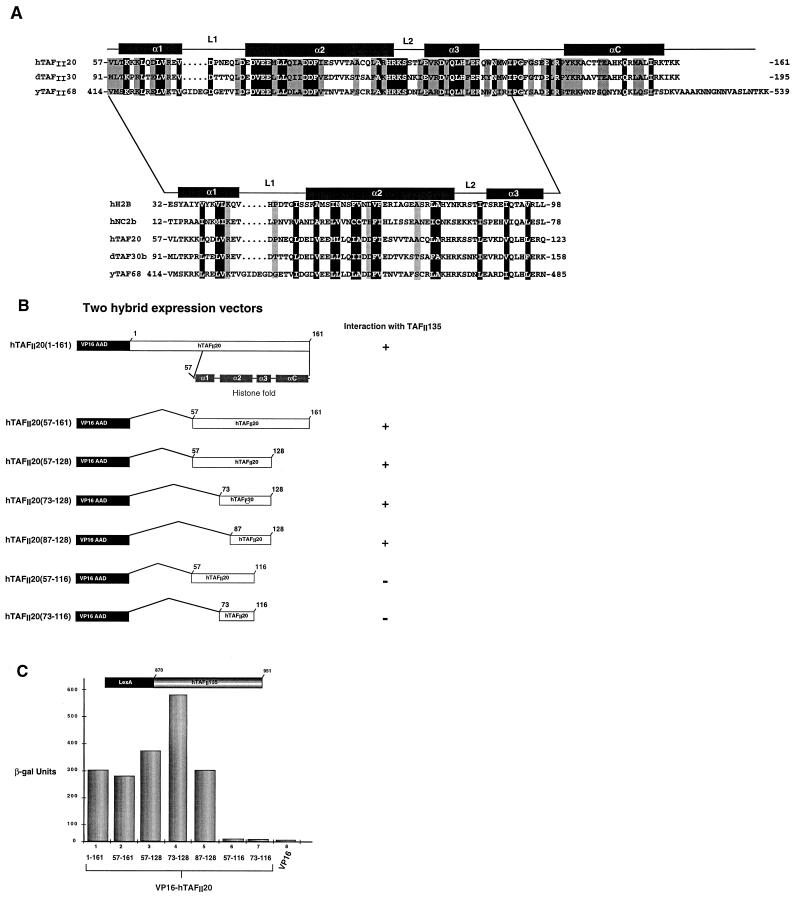

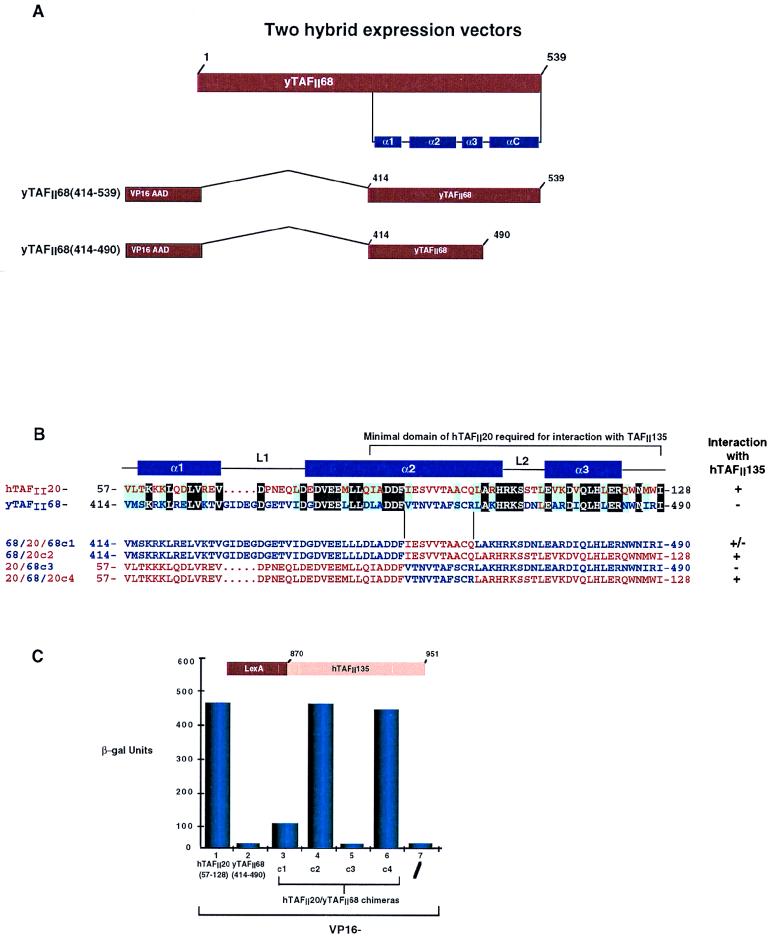

FIG. 2.

(A) Alignment of the sequences of the histone fold regions of hTAFII20, dTAFII30α, and yTAFII68 with those of H2B and NC2β. The prefixes h, d, and y are for human, Drosophila melanogaster, and yeast (S. cerevisiae). The positions of the predicted α helices and loops are indicated above the sequence based on homology with H2B (30). In the upper panel, invariant amino acids are in white on a black background and similar amino acids are indicated by gray shading. In the lower panel, conserved hydrophobic residues are in white on a black background and conserved charged or small residues are indicated by gray shading. Amino acids were classified as follows: small residues, P, A, G, S, and T; hydrophobic residues, L, I, V, A, F, M, C, Y, and W; polar-acidic residues, D, E, Q, and N; basic residues, R, K, and H. (B) Schematic structure of VP16-hTAFII20 fusions. The hTAFII20 amino acids at the boundaries of the fusions are indicated. The ability of each fusion to interact with hTAFII135 is shown to the right by a plus or minus sign. (C) Quantification of β-galactosidase (β-gal) activity in two-hybrid assays. The VP16 AAD-hTAFII20 fusions shown below each lane were assayed in a LexA–hTAFII135(870–951) background as indicated above the graph.

Previous results have shown in vitro interactions between hTAFII20 and hTAFII135 and between their Drosophila homologues dTAFII30α and dTAFII110 (22, 48, 56). We tested the ability of hTAFII135 and hTAFII20 to interact in the yeast two-hybrid assay. Amino acids 372 to 1083 of hTAFII135 were fused to the LexA DBD or the VP16 AAD (see Materials and Methods and Fig. 4A), and the expression vectors were sequentially introduced into yeast with the corresponding hTAFII20 expression vectors. Strong β-galactosidase activity was observed in yeast expressing complementary hTAFII20/hTAFII135 LexA-VP16 AAD pairs (summarized in Fig. 1). These results show that while neither hTAFII20 nor hTAFII135 homodimerizes, they do interact with each other.

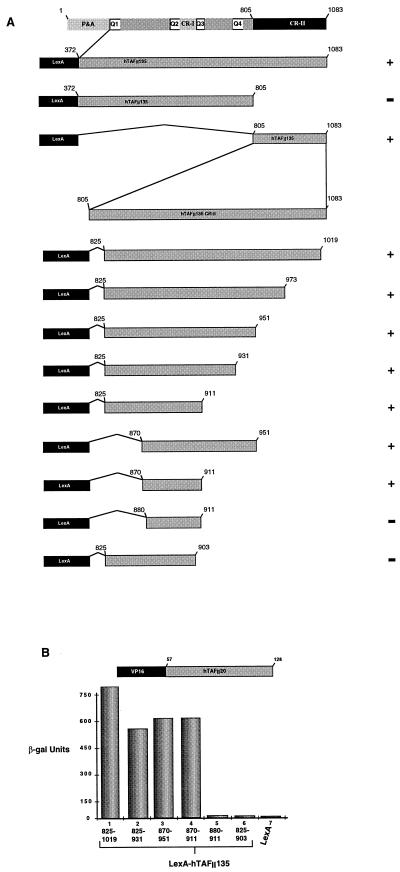

FIG. 4.

(A) Schematic structures of hTAFII135 and LexA two-hybrid fusions. P&A indicates the proline- and alanine-rich region at the N terminus of hTAFII135. Glutamine-rich regions Q1 to Q4 are also indicated, along with conserved domains CR-I and CR-II. The abilities of the LexA-hTAFII135 hybrids to interact with VP16-hTAFII20 are summarized to the right. (B) Determination of the minimal region of hTAFII135 required for interaction with hTAFII20. The LexA-hTAFII135 fusions shown below each lane were assayed in the VP16-hTAFII20 background indicated above the graph. β-gal, β-galactosidase.

The C-terminal domains of hTAFII20, dTAFII30α, and yTAFII68 contain a putative histone fold motif which shows sequence homology to that of H2B (Fig. 2A). The minimal histone fold motif comprises three α helices, (α1, α2, and α3) separated by two loops, L1 and L2. In addition, they may possess an αC helix, as observed in H2B. Fusion proteins containing the full hTAFII20 histone fold or subdomains fused to the VP16 AAD (Fig. 2B) were tested for the ability to interact with LexA–hTAFII135(870–951) (see below). TAFII20(57–161), containing the entire histone fold region, interacted with hTAFII135 as efficiently as full-length hTAFII20 (Fig. 2C, lanes 1 and 2). Interaction was not affected by deletion of the αC helix [hTAFII20(57–128); Fig. 2C, lane 3]. Interaction was mildly increased when the α1 helix was deleted [hTAFII20(73–128); Fig. 2C, lane 4], while wild-type levels were seen when the α1 helix and the N-terminal end of the α2-helix were deleted [TAFII20(87–128); Fig. 2C, lane 5]. In contrast, interaction was abolished when the α3 helix was deleted [hTAFII20(57–116) and hTAFII20(73–116); Fig. 2C, lanes 6 and 7]. Therefore, a minimal region including amino acids 87 to 128 of hTAFII20 containing the C-terminal region of the α2 helix along with L2 and the α3 helix suffices to mediate interaction with hTAFII135.

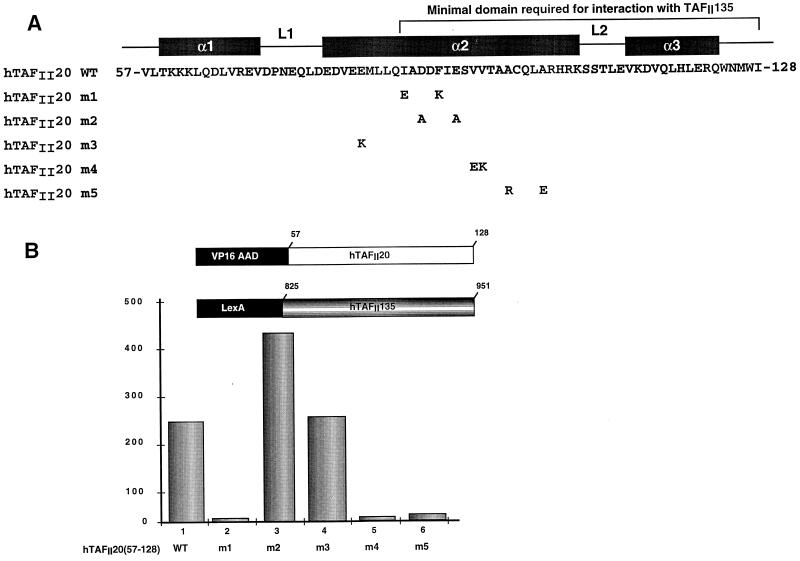

In histone folds, the α2 helix is an amphipathic α helix in which many of the hydrophobic residues interact with the hydrophobic residues of the α2 helix of the heterodimeric partner, while the solvent-exposed face comprises mainly polar and charged residues. Alignment of the hTAFII20 histone fold with that of H2B, whose structure has been determined, shows that a similar arrangement may exist in hTAFII20. To determine which residues of the hTAFII20 α2 helix were involved in interactions with hTAFII135, hydrophobic or charged residues were mutated (Fig. 3A). Mutation of I87 and F91 completely abolished interaction with hTAFII135 [hTAFII20(57–128) m1; Fig. 3B, lanes 1 and 2). Similarly, mutation of V95 and V96 [hTAFII20(57–128) m4] and A99 and A103 [hTAFII20(57–128) m5] also abolished interaction with hTAFII135 (Fig. 3B, lanes 5 and 6). In contrast, mutation of charged residues D89 and E93 [hTAFII20(57–128) m2] or E82 [hTAFII20(57–128) m3] had no effect on interaction with hTAFII135 (Fig. 3B, lanes 3 and 4). Therefore, the residues which form the hydrophobic interface of the hTAFII20 histone fold are critical for interaction with hTAFII135.

FIG. 3.

(A) Locations of mutations in the hTAFII20 histone fold. The sequence of the hTAFII20 histone fold is shown along with the mutated amino acids below the wild-type (WT) sequence. (B) Mutations in hTAFII20 which abolish interaction with hTAFII135. The hTAFII20 mutants assayed in each lane are shown below the graph in the background of the vectors schematized above the graph.

A region of the CR-II domain of hTAFII135 required for interaction with hTAFII20.

TAFII135 consists of 1,083 amino acids which can be divided into several regions: an N-terminal proline- and alanine-rich region, four glutamine-rich regions which interact with the SP1 and CREB activators, and two conserved regions, CR-I, present in hTAFII105, dTAFII110, and Nervy/ETO, as well as other transcription factors, and the long CR-II region, conserved in hTAFII105 and dTAFII110 (35, 45). We determined the region of hTAFII135 required for interaction with hTAFII20 by using a series of LexA-TAFII135 fusions (Fig. 4A). The N-terminal region of hTAFII135(372–805) lacking CR-II did not interact with hTAFII20 (data not shown), whereas interaction was observed with the hTAFII135(805–1083) and hTAFII135(825–1019) fusions containing only the CR-II region (summarized in Fig. 4A; see also Fig. 4B, lane 1).

Further CR-II region deletion mutants were made to more precisely define the amino acids required for interaction with hTAFII20. Progressive deletions from both the N and C termini indicated that amino acids 870 to 911 suffice to mediate interaction with hTAFII20 (Fig. 4A and B, lanes 2 to 4). However, deletion of a further 10 amino acids from the N terminus [hTAFII135(880–911)] or deletion of 8 amino acids from the C terminus [hTAFII135(825–903)] completely abolished interaction with hTAFII20 (Fig. 4A and B, lanes 5 and 6). Therefore, amino acids 870 to 911 constitute the minimal domain required for interaction with hTAFII20.

Chimeras between the histone fold domains of hTAFII20 and its yeast homologue yTAFII68 interact with hTAFII135.

Yeast yTAFII68 contains a histone fold sequence which is highly homologous to that of hTAFII20 and is located at the C terminus of the protein between amino acids 414 and 539 (Fig. 2A and 5A and B). To test the abilities of the yTAFII68 histone fold to homodimerize and to interact with hTAFII135, two-hybrid expression vectors were constructed in which the histone fold region was fused to the LexA DBD or the VP16 AAD (Fig. 5A). Upon coexpression in yeast, no interaction was seen between LexA–yTAFII68(414–539) and VP16–yTAFII68(414–539) (summarized in Fig. 1), showing that, as observed for hTAFII20, yTAFII68 does not homodimerize. However, no interaction between LexA-hTAFII135 and VP16-yTAFII68 was observed irrespective of whether the entire histone fold region, including the αC or only the α1 to α3 region, was used (summarized in Fig. 1; see also Fig. 5C, lane 2). Thus, despite the high homology between the hTAFII20 and yTAFII68 histone fold regions, they differ in the ability to interact with hTAFII135.

FIG. 5.

(A) Schematic structures of yTAFII68 two-hybrid vectors. The location of the histone fold in yTAFII68 is shown schematically. (B) Structure of chimeric hTAFII20-yTAFII68 histone folds. A sequence comparison of the histone folds of hTAFII20 and yTAFII68 is shown in which the conserved residues are highlighted against a black background and the similar residues are shaded in blue. The criteria for identity take into account differences seen in the dTAFII30α sequence as shown in Fig. 2A. In chimeras c1 to c4, the hTAFII20 residues are in red and the yTAFII68 residues are in blue. Their abilities to interact with hTAFII135 are summarized to the right. (C) Interaction of chimeras c1 to c4 with hTAFII135. The chimeras used are shown below each lane, and their activity, as measured in the hTAFII135 background, is indicated above the graph. β-gal, β-galactosidase.

Comparison of the yTAFII68 and hTAFII20 histone fold sequences shows two regions of variability which may contribute to specificity. The L1 loop of yTAFII68 is longer than that of hTAFII20, and the sequences are divergent. Similarly, the region of the α2 helix between amino acids I92 and Q101 of hTAFII20 and L2 show several differences. To determine which regions of the histone fold were responsible for the specificity of interaction, chimeras between the hTAFII20 and yTAFII68 histone folds were made in fusions with the VP16 AAD (Fig. 5B).

We first replaced the divergent sequence between V454 and R463 of the yTAFII68 α2 helix with I92 to Q101 of hTAFII20 (68/20/68 c1, Fig. 5B). This chimera interacted weakly with hTAFII135 (Fig. 5C, lane 3), and replacement of amino acids V454 to I490 of yTAFII68 with those of hTAFII20 allowed full interaction with hTAFII135 (68/20 c2, lane 4). On the other hand, the converse chimera did not interact with hTAFII135 (20/68 c3, lane 5) whereas the replacement of I92 to Q101 of hTAFII20 with the equivalent yTAFII68 region did not affect interaction with hTAFII135 (20/68/20 c4). Therefore, interaction with TAFII135 requires hTAFII20 amino acids C terminal of I92 which cannot be replaced with their yTAFII68 counterparts whereas the differences in the L1 loop do not affect interaction with TAFII135. Within the hTAFII20 α2-L2-α3 segment, one determinant of specificity is located between I92 and Q101; however, full interaction requires the entire region.

hTAFII20 and hTAFII135 coexpressed in E. coli heterodimerize.

To show that hTAFII20 and hTAFII135 interact directly and form heterodimers, as suggested by the yeast two-hybrid data, each protein was expressed in E. coli (see Materials and Methods). Expression of the his6-tagged hTAFII20(57–128) histone fold region alone resulted in the accumulation of almost totally insoluble protein, little of which was retained on Co2+ beads (Fig. 6A, lanes 2 and 3). When expressed alone, untagged hTAFII135(825–1019) was not significantly retained on the Co2+ beads (lanes 4 and 5) while hTAFII135(870–952) was unstable and failed to accumulate (Fig. 6A, lane 8).

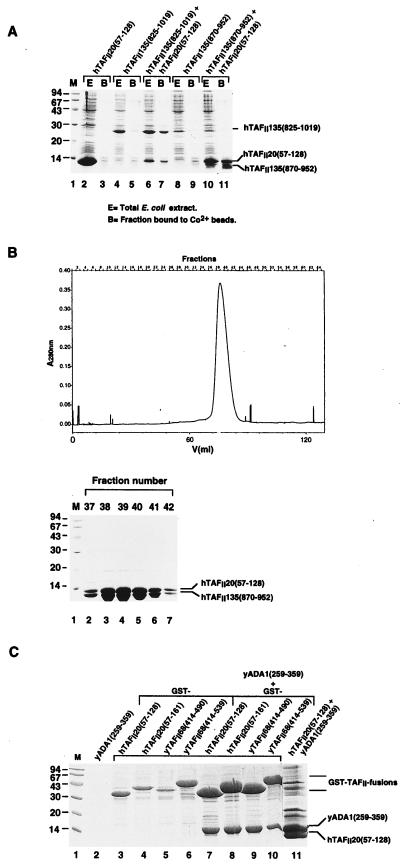

FIG. 6.

Coexpression of hTAFII20 and hTAFII135 in E. coli. (A) Bacteria were transformed to express the proteins shown above the lanes, and total extracts (E) were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and staining with Coomassie brilliant blue. The proteins from each extract bound to Co2+ beads (B) are shown in the adjacent lanes. The migration of the molecular mass standards in lane M (in kilodaltons) are shown on the left. (B) Elution profile of the purified hTAFII20(57–128)–hTAFII135(870–952) complex from a Superdex 75 gel filtration column. The lower panel shows the Coomassie brilliant blue staining of the relevant eluted fractions after SDS-PAGE. (C) yADA1 interacts with the histone fold of yTAFII68 and hTAFII20. Bacterial extracts expressing the proteins shown above each lane were chromatographed on glutathione-Sepharose, and the bound proteins were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and staining with Coomassie brilliant blue. Lane 11 shows the proteins bound to Co2+ beads following coexpression of his6–hTAFII20(57–128) and yADA1(259–359).

In contrast, coexpression of hTAFII135(825–1019) resulted in solubilization of his6–hTAFII20(57–128) and the formation of an hTAFII20/hTAFII135 complex, since the untagged hTAFII135(825–1019) protein was now retained on the Co2+ beads in stoichiometric amounts with his6–hTAFII20(57–128) (Fig. 6A, lanes 6 and 7 compared with lanes 4 and 5). Likewise, coexpression of his6–hTAFII20(57–128) stabilized hTAFII135(870–952) and resulted in the formation of a soluble complex which could be retained on Co2+ beads (Fig. 6A, lanes 10 and 11 compared with lanes 8 and 9). These results show that coexpression of hTAFII20 and hTAFII135 promotes the formation of a stable, soluble complex while each protein alone is insoluble or unstable.

To determine whether the hTAFII20/hTAFII135 complex is a heterodimer or a heterotetramer, the purified complex formed between his6–hTAFII20(57–128) and hTAFII135(870–952) was analyzed by gel filtration. The complex eluted from a Superdex 75 column as a single species with an apparent native molecular mass of approximately 20 kDa indicative of a heterodimer (Fig. 6B). Therefore, the histone fold region of hTAFII20 forms a heterodimer with hTAFII135.

Similar coexpression experiments were performed with the hTAFII135 derivatives and a GST fusion of the histone fold region of yTAFII68. In agreement with the yeast two-hybrid data, no hTAFII135 was retained on glutathione beads along with GST-yTAFII68 (data not shown). There is thus no interaction between E. coli-expressed histone fold regions of yTAFII68 and hTAFII135.

Yeast ADA1 interacts with the histone fold regions of hTAFII20 and yTAFII68.

It has previously been reported that there is no yeast homologue for TAFII135 (35, 40). Nevertheless, our finding that yTAFII68 does not homodimerize implies that there is a heterodimeric partner(s) for the yTAFII68 histone fold in TFIID and SAGA. To identify potential partners, we used the sequence of the minimal region of hTAFII135 required for interaction with hTAFII20 to blast search the yeast genome. One of the highest-scoring proteins found in this way was the SAGA component ADA1 (24, 47).

The sequences of both yeast ADA1 and a putative Schizosaccharomyces pombe ADA1 homologue could be aligned with those of hTAFII135, hTAFII105, and dTAFII110, and this region is predicted to adopt a helix-strand-helix conformation (Fig. 7A). This alignment shows the presence of many conserved positions occupied by hydrophobic residues. At several other well-conserved positions, a hydrophobic residue is sometimes replaced by a threonine. Two conserved basic residues are also observed in the α1 helix and in L2 (Fig. 7A). Interestingly, most of these residues are also conserved in the α1 and α2 helices of H2A and in the α subunit of the transcriptional repressor NC2, which has been classified as an H2A-like protein (15, 37).

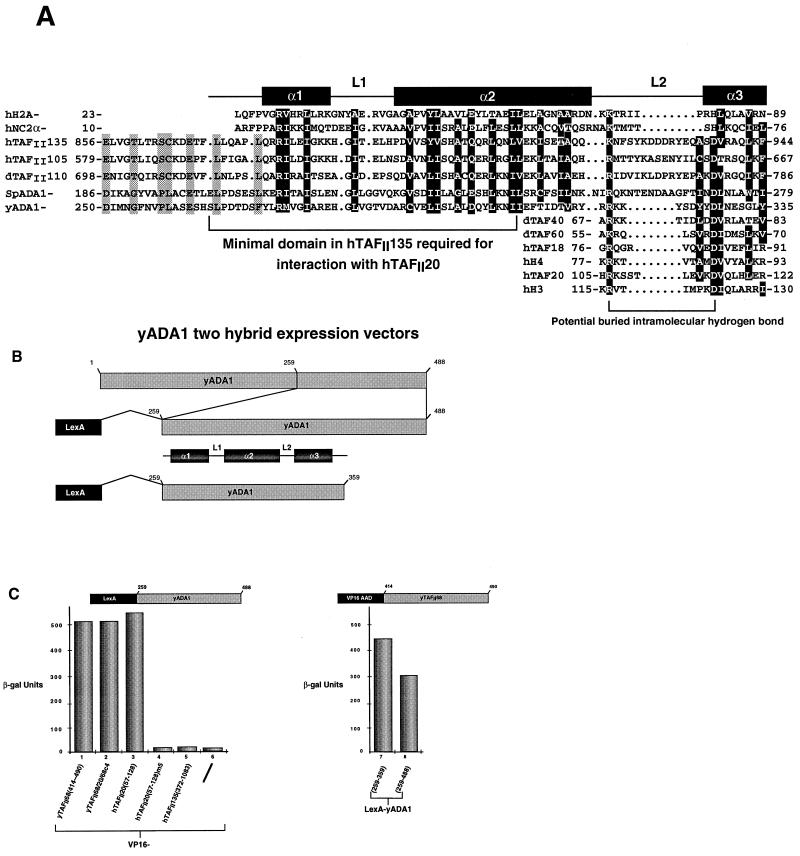

FIG. 7.

(A) Sequence comparison of the putative histone fold regions of hTAFII135, hTAFII105, dTAFII110, yADA1, and a putative S. pombe ADA1 (accession no. CAA21903) with H2A and NC2α. In the α1-L1-α2 segment, residues which are conserved in the ADA1, TAFII, and H2A/NC2α families are in white against a black background. Residues which are conserved only between the TAFII and ADA1 families are shaded in grey. In the L2-α3 segment, additional alignments with the α3 helices of dTAFII40, dTAFII60, hTAFII18, hH3, hH4, and hTAFII20 are shown. Highly conserved residues are in white against a black background. The location of a potential buried intramolecular hydrogen bond between the R(K) and D residues is indicated. (B) Schematic structures of yADA1 two-hybrid vectors. (C) Two-hybrid interactions with yADA1. In the left graph, the proteins tested for interaction with yADA1(259–488) are shown below the lanes. In the right graph, the yADA1 deletion mutants tested for interaction with yTAFII68(414–490) are shown. β-gal, β-galactosidase.

To test the ability of this region of ADA1 to interact with yTAFII68 and hTAFII20, amino acids 259 to 488 or 259 to 359 were fused to the LexA DBD and transformed into yeast (Fig. 7B). A strong interaction was seen between both of the yADA1 constructs and yTAFII68(414–490) or hTAFII20(57–128) (Fig. 7C, lanes 1, 3, 7, and 8, and data not shown). Strong interactions were also seen with the 68/20/68 c3 and c4 chimeras (Fig. 7C, lane 2, and data not shown). Importantly, yADA1 interaction with hTAFII20 was abolished by mutations m1, m4, and m5 in the hydrophobic core of the hTAFII20 α2 helix (lane 4 and data not shown). As expected, however, no interaction was observed with hTAFII135(372–1083) (lane 5) or with the VP16 AAD alone (lane 6). These results demonstrate that the region of yADA1 with homology to hTAFII135 and H2A interacts specifically with the histone fold regions of yTAFII68 and hTAFII20 but not with hTAFII135.

We also tested the ability of yADA1 to form complexes with yTAFII68 and hTAFII20 in E. coli. GST fusions of the histone fold regions of hTAFII20(57–128) or hTAFII20(57–161) or yTAFII68(414–490) or yTAFII68(414–539) were coexpressed in E. coli with an untagged version of yADA1(259–359). When expressed alone, yADA1 was globally insoluble and did not bind to glutathione or Co2+ beads (Fig. 6C, lane 1, and data not shown). In contrast, when coexpressed with the GST-histone fold fusion of yTAFII68 or hTAFII20, yADA1(259–359) was retained on glutathione beads (Fig. 6C, lanes 7 to 10). Note also that coexpression with yADA1(259–359) significantly increased the solubility of the GST-TAFII fusions (compare lanes 3 to 6 and 7 to 10). Similarly, coexpression of yADA1(259–359) solubilized his6–hTAFII20(57–128) and resulted in the formation of a heterodimeric complex which could be retained on Co2+ beads. (Fig. 6C, lane 11). These results show that yADA1 interacts directly with the histone fold domains of yTAFII68 or hTAFII20 to form stable complexes.

The histone fold region of hTAFII135 is required for coactivator activity in mammalian cells.

We have previously shown that coexpression of hTAFII135 or hTAFII28 potentiates transcriptional activation by ligand-dependent activation function 2 of various nuclear receptors (33, 35). In hTAFII28, the histone fold region plays a critical role in this function (26). To test the requirement for the histone fold region of hTAFII135 in this process, we generated an hTAFII135 deletion mutant in which the minimal region required for interaction with hTAFII20 (amino acids 870 to 910) had been removed.

As previously described, coexpression of hTAFII135(372–1083) in Cos cells strongly increased activation by a chimeric fusion protein comprising the DBD of the yeast activator GAL4 (G4) fused to activation function 2 of the nuclear receptor for all-trans retinoic acid (RARα) from a minimal G4-responsive promoter (Fig. 8, lanes 2, 4, and 5). In contrast to our previous findings, the CR-II region alone (amino acids 805 to 1083) was also able to elicit such an effect, albeit less strongly than amino acids 372 to 1083 (Fig. 8, lanes 7 and 8). Deletion of amino acids 870 to 910 from the CR-II domain completely abrogated the transcriptional coactivator effect (lanes 10 and 11). Therefore, the histone fold within the CR-II domain is essential for the coactivator activity of hTAFII135.

FIG. 8.

The hTAFII135 histone fold is required for coactivator activity. Quantitative analysis of chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (CAT) activity. The structures of the activator and reporter plasmids are schematized above the graph. The plasmids transfected in each lane are shown below the graph. Transfections contained 50 nM RARα, 2 μg of the chloramphenicol acetyltransferase reporter plasmid, and 2 μg of a luciferase internal control (35), along with 0.25 μg of the G4-RARα chimera and 3 or 5 μg of the hTAFII135 expression vectors, as indicated. Quantitation was done on a Fujix Bas 2000.

DISCUSSION

hTAFII20-hTAFII135, a novel histone-like pair in the TFIID complex.

In this report, we show that hTAFII20 interacts with hTAFII135 in yeast two-hybrid assays. In these assays, interaction with hTAFII135 requires a minimal region of the hTAFII20 histone fold comprising the C-terminal region of the α2 helix, L2, and the α3 helix. This is in good agreement with the region previously observed in in vitro interactions (22). Interaction with hTAFII135 is abolished by mutation of hydrophobic amino acids in the hTAFII20 α2 helix. Many of the equivalent residues in H2B participate in interactions with H2A in the nucleosome (30). These observations indicate that hTAFII20-hTAFII135 interaction also involves the hydrophobic interface formed by residues of the hTAFII20 α2 helix.

Interestingly, despite the fact that the histone fold region of yTAFII68 is highly homologous to that of hTAFII20, no interaction between yTAFII68 and hTAFII135 was observed. However, interaction with hTAFII135 was partially restored when amino acids V454 to R463 of the yTAFII68 α2 helix were replaced with I92 to Q101 of hTAFII20 and fully restored when the whole α2-L2-α3 segment was exchanged. The region from I92 to Q101 therefore contains specific determinants for interaction with hTAFII135. However, the remainder of the L2-α3 region, which appears highly conserved, must contain further important determinants and only the combination of these two regions allows full interaction with hTAFII135. Thus, even apparently minor differences in the primary amino acid sequence can have important consequences in terms of partner specificity.

The histone fold region of hTAFII20 is insoluble when expressed alone in E. coli. This is what is observed when many other histone fold proteins are expressed in the absence of their heterodimeric partners and is not what would be expected if the hTAFII20 histone fold were to homodimerize. Similarly, the hTAFII135 CR-II region required for interaction with hTAFII20 is unstable and does not accumulate. In contrast, coexpression of these two proteins results in the formation of a soluble, stable complex which has the native molecular mass of a heterodimer. Indeed, in analogous coexpression experiments, hTAFII28 solubilized hTAFII18 and the resulting complex eluted as a heterodimer while the histone fold region of hTAFII31 solubilized that of hTAFII80 and the resulting complex eluted as a heterotetramer. However, in mixing and matching experiments, no complexes other than hTAFII28-hTAFII18, hTAFII31-hTAFII80, and hTAFII20-hTAFII135 were formed (unpublished data). Therefore, there are determinants within the histone folds of these TAFIIs which impose strict partner specificity rules.

Taken together, the interaction mapping data obtained with yeast and the biochemical characterization of the bacterially expressed proteins strongly suggest that hTAFII20 and hTAFII135 interact directly via a histone fold and form a novel histone-like pair in the TFIID complex (Fig. 9).

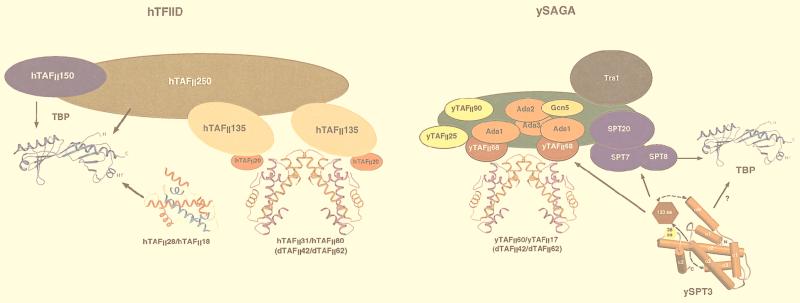

FIG. 9.

Summary of the structures and some of the molecular interactions within the TFIID and SAGA complexes. In hTFIID, ribbon representations of the structures of the TBP (42), dTAFII60/TAFII40 (54), and hTAFII28/hTAFII18 are shown (5). Other TAFIIs are depicted as colored ovals. Some of the molecular interactions are shown either by overlapping of the ovals or by arrows. In SAGA, the predicted structure of SPT3 is indicated along with the TBP and dTAFII60/TAFII40, whose histone fold domain is assumed to adopt the same structure as that of yTAFII60/TAFII17. Potential interactions, as suggested in references 9, 13, 16, 17, 31, 44, and 47, are depicted. aa, amino acids.

Previous models have proposed that hTAFII20 homodimers contribute to the formation of a histone octamer-like structure within TFIID. In two-hybrid assays, no interaction between lexA-hTAFII20 and VP16-hTAFII20 was observed although each of these proteins interacted with hTAFII135. Furthermore, when radiolabelled full-length recombinant hTAFII20 was used to probe immunopurified hTFIID in far-Western blot experiments, interaction with hTAFII135 was clearly seen but no interaction with hTAFII20 was observed (our unpublished data).

It has been shown that dTAFII30α and hTAFII20 can oligomerize (22, 56). For hTAFII20, oligomerization was observed with a fragment comprising the C-terminal half of the α2 helix, L2, and the α3 helix. In contrast, as no oligomerization was seen with the full α1-α3 region, it is unlikely to correspond to homodimerization of the histone fold. It is possible that in such experiments the short subdomains of hTAFII20 used were misfolded and formed aggregates due to the presence of many hydrophobic residues. Indeed, our coexpression experiments show that accumulation of the soluble hTAFII20 histone fold domain requires the presence of hTAFII135. Taken together, all of our data argue against the existence of hTAFII20 homodimers and for the formation of heterodimers with hTAFII135.

In hTAFII135, interaction with hTAFII20 minimally requires amino acids 870 to 911 of the hTAFII135 CR-II region. This region is conserved in hTAFII105, which, in contrast to previous reports (12), also heterodimerizes with hTAFII20 in yeast two-hybrid assays (our unpublished data). This minimal region shows homology to a region of yADA1 which can also mediate specific interactions with yTAFII68 and hTAFII20. Both the hTAFII135 and yADA1 regions can be further aligned with the α1-L1-α2 region of H2A and the H2A-like protein NC2α (and the C subunit of transcription factor NFY [our unpublished data]). This homology with H2A and H2A-like proteins is consistent with the observation that their partners hTAFII20 and yTAFII68 are H2B-like proteins. Most of the conserved residues are hydrophobic, with the exceptions of a conserved arginine in the α1 helix, a polar-acidic residue in the α2 helix, and a basic residue at the beginning of L2. The homology between the TAFII135/ADA1 and H2A/NC2α families is comparable to that seen between the hTAFII20 and H2B/NC2β families in that the majority of the conserved residues are the hydrophobic amino acids which make up the heterodimerization interface (30).

The alignment predicts that the minimal domain of hTAFII135 required for interaction with hTAFII20 would contain the α1-L1-α2 region of the histone fold. This is in good agreement with the observation that the minimal domain of hTAFII20 required for interaction is the α2-L2-α3 region. Due to the head-to-tail arrangement of the histone fold partners, the α1-L1-α2 region of hTAFII135 would be juxtaposed with the α2-L2-α3 region of hTAFII20. The histone fold is postulated to arise from gene duplication of two helix-strand-helix segments, HSH1 and HSH2, corresponding to the N- and C-terminal halves of the histone fold (3). The minimal TAFII20 and TAFII135 domains necessary for their mutual interactions correspond well to these predicted HSH2 and HSH1 segments, respectively.

By using only the homology with H2A/NC2α, it was not possible to locate an α3 helix in the TAFII135 and ADA1 families. However, by taking into account other known histone fold α3 sequences, homology between the TAFII135/ADA1 families and dTAFII40, dTAFII60, and hTAFII20 could be found. In this alignment, a D(V/I/L) pair is found to be conserved. In H3, H4, and dTAFII60, this D residue forms a buried intramolecular hydrogen bond with a conserved R(K) residue in the L2 loop which stabilizes the folding of the α3 helix back over the α2 helix (30, 54). In other histone folds (H2B and dTAFII40), this pair is conserved but no interaction is observed. This D(V/I/L) pair is therefore a useful signature which allows us to identify a potential hTAFII135/ADA1 α3 helix at this position. It is interesting to notice from this alignment that the hTAFII135 region required for interaction with hTAFII20 is well conserved and similar to H2A, whereas the more divergent α3 region is not absolutely required for interaction.

The histone fold region is critically required for coexpressed hTAFII135 to potentiate transcriptional activation by the RAR. We previously reported that hTAFII135 coactivator activity requires a domain N terminal to the CR-II region (35). In the subsequent experiments reported here, however, we did see activity of the CR-II region alone, although it was weaker than that seen when the N-terminal region was present. Notwithstanding this discrepancy, deletion of the HSH1 segment of the hTAFII135 histone fold completely abrogates coactivator activity.

In hTAFII28, deletion of the histone fold region also abrogates coactivator activity (33). We have further shown that specific residues in the α2 helix of the hTAFII28 histone fold are critical for this coactivator activity (26). These residues are located on the solvent-exposed face of this helix and in the interface with hTAFII18. This suggests that hTAFII28 acts by integrating into the endogenous TFIID via interactions with hTAFII18 and that the solvent-exposed face of the α2 helix interacts with other factors required for coactivator activity (for a discussion, see reference 26). Further experiments are required to determine whether a similar mechanism operates in the case of hTAFII135.

yTAFII68-yADA1, a novel histone-like pair in the SAGA complex.

Our present results show that yADA1 is a heterodimeric partner for yTAFII68, providing a direct physical link between the TAFII and yADA protein families. yADA1 and yTAFII68 have been identified as components of the SAGA complex (16, 44). Previous results have shown that the histone fold region of yTAFII68 is necessary and sufficient for integration in the SAGA complex (40, 41). Shifting of tightly temperature-sensitive mutants of yTAFII68 with mutations in the histone fold domain to the nonpermissive temperature results in the disappearance of yADA1 and disruption of the SAGA complex (38). Similarly, in yADA1 mutant strains, the integrity of the SAGA complex is severely compromised (47). These observations are consistent with our present data, and together they show that the yTAFII68-yADA1 pair is a critical structural element in the SAGA complex. However, in another yTAFII68 temperature-sensitive strain, yTAFII68 is depleted from SAGA prepared from cells grown at the nonpermissive temperature along with SPT3, suggesting that there is also an intimate relationship between these two histone fold proteins (16).

Our results lead to a better understanding of the molecular interactions within the SAGA complex (Fig. 9). If there is a histone octamer-like core in SAGA, it may comprise a yTAFII60-yTAFII17 heterotetramer and at least one yTAFII68-yADA1 heterodimer. Furthermore, the yTAFII68-yADA1 interaction provides a mechanism by which the yTAFII60-yTAFII17 heterotetramer, which is also present in TFIID, can be recruited into SAGA. This TAFII substructure is linked to the other SAGA components via heterodimerization with ADA1, which itself interacts with ADA3 (our unpublished data). As the interactions among ADA2, ADA3, and GCN5 have been well characterized (9), this results in the identification of a well-defined substructure within the SAGA complex.

While the genetic data are consistent with an important yADA1-yTAFII68 interaction in the SAGA complex, both biochemical and genetic results indicate that yADA1 is likely not a component of yTFIID. The genes encoding the yTAFIIs are all essential, while the yADA1 gene is not. In addition, yTBP does not coprecipitate with yADA1 (24). Mutation of yTAFII68 results in the disappearance of yADA1, but deletion of yADA1 does not result in the disappearance of yTAFII68. This indicates that most, if not all, of ADA1 is complexed with yTAFII68 in SAGA or related complexes while, as previously noted (38), the majority of yTAFII68 is in TFIID, where it would not depend on the presence of yADA1 for stability but may be complexed with another partner, since it does not homodimerize. No homologue for TAFII135 has been described in yeast, whose genome does not encode a protein with obvious homology to TAFII135. The sequence of the yTAFII68 partner in TFIID must therefore diverge from that of TAFII135, and we have not yet identified potential partners. Given the high degree of homology between the other human and yeast TAFIIs, it is quite remarkable that TAFII135 is an exception to this rule.

Our results show that there are three histone-like pairs in the TFIID complex, hTAFII31-hTAFII80, hTAFII20-hTAFII135, and hTAFII28-hTAFII18, and in the SAGA complex, yTAFII17-yTAFII60, yTAFII68-yADA1, and SPT3. Consequently, in each case, there are more pairs than can be accommodated in a simple octamer-like model. Further experiments will reveal how these three pairs interact together and/or with other proteins to form the TFIID and SAGA complexes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank S. Hollenberg for the generous gift of yeast strain L40; R. Losson, J. Ortiz, C. Gaudon, and M. Cervino for help with yeast assays and material; M. Abrink and L. Perletti for critical reading of the manuscript; S. Vicaire and D. Stephane for DNA sequencing; the staff of the cell culture and oligonucleotide facilities; and B. Boulay, J. M. Lafontaine, R. Buchert, and C. Werlé for illustrations.

S.W. and C.R. were supported by EMBO fellowships. This work was supported by grants from the CNRS, the INSERM, the Hôpital Universitaire de Strasbourg, the Ministère de la Recherche et de la Technologie, the Association pour la Recherche contre le Cancer, the Ligue Nationale contre le Cancer, and the Human Frontier Science Programme.

REFERENCES

- 1.Apone L M, Virbasius C A, Holstege F C, Wang J, Young R A, Green M R. Broad, but not universal, transcriptional requirement for yTAFII17, a histone H3-like TAFII present in TFIID and SAGA. Mol Cell. 1998;2:653–661. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80163-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arents G, Burlingame R W, Wang B C, Love W E, Moudrianakis E N. The nucleosomal core histone octamer at 3.1 A resolution: a tripartite protein assembly and a left-handed superhelix. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:10148–10152. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.22.10148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arents G, Moudrianakis E N. Topography of the histone octamer surface: repeating structural motifs utilized in the docking of nucleosomal DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:10489–10493. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.22.10489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bell B, Tora L. Regulation of gene expression by multiple forms of TFIID and other novel TAFII-containing complexes. Exp Cell Res. 1999;246:11–19. doi: 10.1006/excr.1998.4294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Birck C, Poch O, Romier C, Ruff M, Mengus G, Lavigne A C, Davidson I, Moras D. Human TAFII28 and TAFII18 interact through a histone fold encoded by atypical evolutionary conserved motifs also found in the SPT3 family. Cell. 1998;94:239–249. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81423-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brand M, Yamamoto K, Staub A, Tora L. Identification of TATA-binding protein-free TAFII-containing complex subunits suggests a role in nucleosome acetylation and signal transduction. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:18285–18289. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.26.18285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burley S K, Roeder R G. Biochemistry and structural biology of transcription factor IID (TFIID) Annu Rev Biochem. 1996;65:769–799. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.65.070196.004005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burley S K, Xie X, Clark K L, Shu F. Histone-like transcription factors in eukaryotes. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 1997;7:94–102. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(97)80012-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Candau R, Berger S L. Structural and functional analysis of yeast putative adaptors. Evidence for an adaptor complex in vivo. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:5237–5245. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.9.5237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Caron C, Mengus G, Dubrowskaya V, Roisin A, Davidson I, Jalinot P. Human TAFII28 interacts with the human T cell leukemia virus type I Tax transactivator and promotes its transcriptional activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;9:3662–3667. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.8.3662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davidson I, Romier C, Lavigne A C, Birck C, Mengus G, Poch O, Moras D. Functional and structural analysis of the subunits of human transcription factor TFIID. Cold Spring Harbor Symp Quant Biol. 1998;63:233–241. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1998.63.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dikstein R, Zhou S, Tjian R. Human TAFII105 is a cell type-specific TFIID subunit related to hTAFII130. Cell. 1996;87:137–146. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81330-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eisenmann D M, Arndt K M, Ricupero S L, Rooney J W, Winston F. SPT3 interacts with TFIID to allow normal transcription in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genes Dev. 1992;6:121–131. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.7.1319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gietz R D, Schiestl R H, Willems A R, Woods R A. Studies on the transformation of intact yeast cells by the LiAc/SS-DNA/PEG procedure. Yeast. 1995;11:355–360. doi: 10.1002/yea.320110408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goppelt A, Stelzer G, Lottspeich F, Meisterernst M. A mechanism for repression of class II gene transcription through specific binding of NC2 to TBP-promoter complexes via heterodimeric histone fold domains. EMBO J. 1996;15:3105–3116. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grant P A, Schieltz D, Pray-Grant M G, Steger D J, Reese J C, Yates J R, Workman J L. A subset of TAFIIs are integral components of the SAGA complex required for nucleosome acetylation and transcriptional stimulation. Cell. 1998;94:45–53. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81220-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grant P A, Schieltz D, Pray-Grant M G, Yates J R, Workman J L. The ATM-related cofactor Tra1 is a component of the purified SAGA complex. Mol Cell. 1998;2:863–867. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80300-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grant P A, Sterner D E, Duggan L J, Workman J L, Berger S L. The SAGA unfolds: convergence of transcription regulators in chromatin-modifying complexes. Trends Cell Biol. 1998;8:193–197. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(98)01263-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grant P A, Workman J L. Transcription. A lesson in sharing? Nature. 1998;396:410–411. doi: 10.1038/24723. . (News.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hoffmann A, Chiang C M, Oelgeschlager T, Xie X, Burley S K, Nakatani Y, Roeder R G. A histone octamer-like structure within TFIID. Nature. 1996;380:356–359. doi: 10.1038/380356a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hoffmann A, Oelgeschlager T, Roeder R G. Considerations of transcriptional control mechanisms: do TFIID-core promoter complexes recapitulate nucleosome-like functions? Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:8928–8935. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.17.8928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hoffmann A, Roeder R G. Cloning and characterization of human TAF20/15. Multiple interactions suggest a central role in TFIID complex formation. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:18194–18202. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.30.18194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Holstege F C, Jennings E G, Wyrick J J, Lee T I, Hengartner C J, Green M R, Golub T R, Lander E S, Young R A. Dissecting the regulatory circuitry of a eukaryotic genome. Cell. 1998;95:717–728. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81641-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Horiuchi J, Silverman N, Pina B, Marcus G A, Guarente L. ADA1, a novel component of the ADA/GCN5 complex, has broader effects than GCN5, ADA2, or ADA3. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:3220–3228. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.6.3220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jacq X, Brou C, Lutz Y, Davidson I, Chambon P, Tora L. Human TAFII30 is present in a distinct TFIID complex and is required for transcriptional activation by the estrogen receptor. Cell. 1994;79:107–117. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90404-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lavigne A C, Gangloff Y G, Carr L, Mengus G, Birck C, Poch O, Romier C, Moras D, Davidson I. Synergistic transcriptional activation by TATA-binding protein and hTAFII28 requires specific amino acids of the hTAFII28 histone fold. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:5050–5060. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.7.5050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lavigne A C, Mengus G, May M, Dubrovskaya V, Tora L, Chambon P, Davidson I. Multiple interactions between hTAFII55 and other TFIID subunits. Requirements for the formation of stable ternary complexes between hTAFII55 and the TATA-binding protein. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:19774–19780. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.33.19774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.LeDouarin B, Nielsen A L, Garnier J M, Ichinose H, Jeanmougin F, Losson R, Chambon P. A possible involvement of TIF1 alpha and TIF1 beta in the epigenetic control of transcription by nuclear receptors. EMBO J. 1996;15:6701–6715. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.LeDouarin B, Nielsen A L, You J, Chambon P, Losson R. TIF1 alpha: a chromatin-specific mediator for the ligand-dependent activation function AF-2 of nuclear receptors? Biochem Soc Trans. 1997;25:605–612. doi: 10.1042/bst0250605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Luger K, Mader A W, Richmond R K, Sargent D F, Richmond T J. Crystal structure of the nucleosome core particle at 2.8 A resolution. Nature. 1997;389:251–260. doi: 10.1038/38444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Madison J M, Winston F. Evidence that Spt3 functionally interacts with Mot1, TFIIA, and TATA-binding protein to confer promoter-specific transcriptional control in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:287–295. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.1.287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Martinez E, Kundu T K, Fu J, Roeder R G. A human SPT3-TAFII31-GCN5-L acetylase complex distinct from transcription factor IID. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:23781–23785. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.37.23781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.May M, Mengus G, Lavigne A C, Chambon P, Davidson I. Human TAFII28 promotes transcriptional stimulation by activation function 2 of the retinoid X receptors. EMBO J. 1996;15:3093–3104. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mazzarelli J M, Mengus G, Davidson I, Ricciardi R P. The transactivation domain of adenovirus E1A interacts with the C terminus of human TAFII135. J Virol. 1997;71:7978–7983. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.10.7978-7983.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mengus G, May M, Carre L, Chambon P, Davidson I. Human TAFII135 potentiates transcriptional activation by the AF-2s of the retinoic acid, vitamin D3, and thyroid hormone receptors in mammalian cells. Genes Dev. 1997;11:1381–1395. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.11.1381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mengus G, May M, Jacq X, Staub A, Tora L, Chambon P, Davidson I. Cloning and characterization of hTAFII18, hTAFII20 and hTAFII28: three subunits of the human transcription factor TFIID. EMBO J. 1995;14:1520–1531. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07138.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mermelstein F, Yeung K, Cao J, Inostroza J A, Erdjument-Bromage H, Eagelson K, Landsman D, Levitt P, Tempst P, Reinberg D. Requirement of a corepressor for Dr1-mediated repression of transcription. Genes Dev. 1996;10:1033–1048. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.8.1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Michel B, Komarnitsky P, Buratowski S. Histone-like TAFs are essential for transcription in vivo. Mol Cell. 1998;2:663–673. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80164-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moqtaderi Z, Keaveney M, Struhl K. The histone H3-like TAF is broadly required for transcription in yeast. Mol Cell. 1998;2:675–682. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80165-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moqtaderi Z, Yale J D, Struhl K, Buratowski S. Yeast homologues of higher eukaryotic TFIID subunits. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:14654–14658. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.25.14654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Natarajan K, Jackson B M, Rhee E, Hinnebusch A G. yTAFII61 has a general role in RNA polymerase II transcription and is required by Gcn4p to recruit the SAGA coactivator complex. Mol Cell. 1998;2:683–692. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80166-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nikolov D B, Chen H, Halay E D, Hoffman A, Roeder R G, Burley S K. Crystal structure of a human TATA box-binding protein/TATA element complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:4862–4867. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.10.4862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ogryzko V V, Kotani T, Zhang X, Schlitz R L, Howard T, Yang X J, Howard B H, Qin J, Nakatani Y. Histone-like TAFs within the PCAF histone acetylase complex. Cell. 1998;94:35–44. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81219-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Roberts S M, Winston F. Essential functional interactions of SAGA, a Saccharomyces cerevisiae complex of Spt, Ada, and Gcn5 proteins, with the Snf/Swi and Srb/mediator complexes. Genetics. 1997;147:451–465. doi: 10.1093/genetics/147.2.451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Saluja D, Vassallo M F, Tanese N. Distinct subdomains of human TAFII130 are required for interactions with glutamine-rich transcriptional activators. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:5734–5743. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.10.5734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sanders S L, Klebanow E R, Weil P A. TAF25p, a non-histone-like subunit of TFIID and SAGA complexes, is essential for total mRNA gene transcription in vivo. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:18847–18850. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.27.18847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sterner D E, Grant P A, Roberts S M, Duggan L J, Belotserkovskaya R, Pacella L A, Winston F, Workman J L, Berger S L. Functional organization of the yeast SAGA complex: distinct components involved in structural integrity, nucleosome acetylation, and TATA-binding protein interaction. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:86–98. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.1.86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tanese N, Saluja D, Vassallo M F, Chen J L, Admon A. Molecular cloning and analysis of two subunits of the human TFIID complex: hTAFII130 and hTAFII100. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:13611–13616. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.24.13611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vojtek A B, Hollenberg S M, Cooper J A. Mammalian Ras interacts directly with the serine/threonine kinase Raf. Cell. 1993;74:205–214. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90307-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.vom Baur E, Harbers M, Um S J, Benecke A, Chambon P, Losson R. The yeast Ada complex mediates the ligand-dependent activation function AF-2 of retinoid X and estrogen receptors. Genes Dev. 1998;12:1278–1289. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.9.1278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Walker S S, Shen W C, Reese J C, Apone L M, Green M R. Yeast TAFII145 required for transcription of G1/S cyclin genes and regulated by the cellular growth state. Cell. 1997;90:607–614. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80522-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wieczorek E, Brand M, Jacq X, Tora L. Function of TAFII-containing complex without TBP in transcription by RNA polymerase II. Nature. 1998;393:187–191. doi: 10.1038/30283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Workman J L, Kingston R E. Alteration of nucleosome structure as a mechanism of transcriptional regulation. Annu Rev Biochem. 1998;67:545–579. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Xie X, Kokubo T, Cohen S L, Mirza U A, Hoffmann A, Chait B T, Roeder R G, Nakatani Y, Burley S K. Structural similarity between TAFs and the heterotetrameric core of the histone octamer. Nature. 1996;380:316–322. doi: 10.1038/380316a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yamit-Hezi A, Dikstein R. TAFII105 mediates activation of anti-apoptotic genes by NF-kappaB. EMBO J. 1998;17:5161–5169. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.17.5161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yokomori K, Chen J L, Admon A, Zhou S, Tjian R. Molecular cloning and characterization of dTAFII30 alpha and dTAFII30 beta: two small subunits of Drosophila TFIID. Genes Dev. 1993;7:2587–2597. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.12b.2587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]