Abstract

In ageing tissues, long-lived extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins are susceptible to the accumulation of structural damage due to diverse mechanisms including glycation, oxidation and protease cleavage. Peptide location fingerprinting (PLF) is a new mass spectrometry (MS) analysis technique capable of identifying proteins exhibiting structural differences in complex proteomes. PLF applied to published young and aged intervertebral disc (IVD) MS datasets (posterior, lateral and anterior regions of the annulus fibrosus) identified 268 proteins with age-associated structural differences. For several ECM assemblies (collagens I, II and V and aggrecan), these differences were markedly conserved between degeneration-prone (posterior and lateral) and -resistant (anterior) regions. Significant differences in peptide yields, observed within collagen I α2, collagen II α1 and collagen V α1, were located within their triple-helical regions and/or cleaved C-terminal propeptides, indicating potential accumulation of damage and impaired maintenance. Several proteins (collagen V α1, collagen II α1 and aggrecan) also exhibited tissue region (lateral)-specific differences in structure between aged and young samples, suggesting that some ageing mechanisms may act locally within tissues. This study not only reveals possible age-associated differences in ECM protein structures which are tissue-region specific, but also highlights the ability of PLF as a proteomic tool to aid in biomarker discovery.

Keywords: proteomics, peptide location fingerprinting, extracellular matrix, ageing, intervertebral disc, spine, mass spectrometry

1. Introduction

Intervertebral discs (IVDs) are fibrocartilaginous cushions residing between vertebrae, which confer flexibility and stability to the spinal column and function as effective shock absorbers over an individual’s lifetime [1]. Age-associated degeneration of the IVD in the lower lumbar spine is the leading cause of lower back pain within an ageing population [2], imposing major socioeconomic and healthcare burdens.

IVDs (located between the endplates of vertebrae) consist of two extracellular matrix (ECM)-rich tissue compartments: (i) a central gel-like nucleus pulposus (NP), composed predominantly of the chondroitin sulphate proteoglycans (CSPGs) aggrecan and versican, and a relatively disordered network of collagen II and (ii) an encircling annulus fibrosus (AF) consisting of highly ordered, concentric rings (lamellae) of parallel collagen I and elastic fibres arranged in a crisscross pattern [3,4]. These compartments are large, avascular and subject to mechanical loads, creating a challenging environment for tissue repair and regeneration (mediated mainly by a small population of chondrocyte-like cells in the NP and fibroblast-like cells in the AF [5]). Crucially, regional differences in ECM composition exist within the AF. ECM components within the inner AF reflect the interface between the NP and outer AF, being comprised of not only collagen I fibrils but also CSPGs and collagen II fibrils [4,6].

Clinically, the onset and progression of IVD ageing and degeneration is characterised typically by a gradual reduction of hydration, pressure and height of the NP and the formation of tears in AF lamellae making the disc more prone to bulging, protrusion or herniation [7]. This structural damage to the AF, and hence susceptibility to failure, is profoundly regional, with degeneration mainly localised in the posterior-lateral portion of the IVD [8,9]. The dynamic alteration in ECM composition and abundance likely underpins this regional progression of IVD ageing and degeneration, with decreasing levels of CSPGs in both the NP and the AF and increasing levels of collagen I fibres, leading to a fibrotic, dehydrated phenotype [4,10,11,12,13]. Additionally, we previously showed that the protein composition of the inner AF becomes gradually more similar to that of the outer AF with ageing [13]. It is clear, therefore, that understanding the mechanisms and consequences of ECM remodelling is key to defining and potentially reversing IVD degeneration and ageing.

ECM assemblies and components can be long-lived, with biological half-lives measured in years or decades. For example, lung elastic fibres and collagens in cartilaginous tissues remain present throughout the life of an individual [14,15]. Consequently, ECM assemblies residing in the IVD (such as collagen I in the AF [16] and aggrecan in the NP [17]) are susceptible to the progressive accumulation of damage to both their molecular structures and networks over time, leading to loss of functions of many diverse ECM components. The potential causative mechanisms of this remodelling include the chronic exposure of ECM proteins to elevated protease-mediated cleavage [18], cross-linking by sugars leading to advanced glycation end products (AGEs) [19], mechanical fragmentation [20] and oxidation by reactive oxygen species (ROS) [21]. These processes may lead to a spectrum of modifications to protein higher order structures that are challenging to detect. Although several proteomics studies have characterised IVD ageing and degeneration through changes in protein presence and abundance alone [12,13,22,23,24], the identification of ECM proteins susceptible to damage modifications to their structure is also crucial both for the discovery of novel ageing biomarker candidates and for deciphering the underlying mechanisms involved.

Peptide location fingerprinting (PLF) is a new computational technique capable of identifying proteins exhibiting structural differences in mass spectrometry (MS) datasets derived from complex biological samples regardless of the causal mechanisms [25]. In standard proteomics, proteins are exposed to enzymes (e.g., trypsin), generating peptides whose sequence identities and relative abundances are then measured by liquid chromatography tandem MS (LC–MS/MS). PLF relies on the fact that, for a given protein, the pattern of peptides detected by LC–MS/MS following protease digestion is determined by its higher order structure and reflects its solubility, stability and enzyme susceptibility. Therefore, differences in protein structure, due to either the accumulation of damage (via ageing and disease), changes in interaction states with other protein or differential synthesis may be detected by PLF [25,26,27]. This is particularly true for the highly insoluble ECM proteins that exist within tightly bound networks. In standard LC–MS/MS, peptides are mapped to proteins, enabling the quantification of protein abundance. PLF maps and quantifies peptides (by spectral counting) within specific protein regions instead, enabling the detection of statistical differences along the primary structure (peptide yield patterns) [25,26]. Previously, we used PLF to reproducibly detect UVR-induced damage within the structures of photosensitive skin ECM proteins in vitro [26] and tissue-specific differences in eye (ciliary zonule) and skin fibrillin-1 [27]. Crucially, and most recently, we have developed and employed an online webtool (MPLF) to identify potential proteins with structural differences between photoaged and photo-protected skin and young and aged tendon [25]. Comparisons with conventional protein quantification also revealed that PLF identifies significant differences, which are unique to the methodology, particularly in ECM proteins, demonstrating that modifications to protein structure may not correlate with protein abundance in damage-susceptible long-lived proteins [25].

Recently, we have also published DIPPER, a detailed spatiotemporal proteomic analysis of the ageing and degenerating human IVD, which included high-resolution label-free LC–MS/MS performed on 11 separate regions of discs sourced from two male cadaveric lumbar spines, one young (16 years old) and one aged (59 years old) [13]. This study revealed novel, region-specific differences in ECM proteome (matrisome) composition and abundance, which demonstrated a dynamic shift along the lateral and anteroposterior axes, with a rapid decline of NP proteins and an increase in AF proteins in the aged inner AF. Although this proteomic study was highly detailed, modification-related differences to ECM protein structures were not interrogated. Since degeneration in the ageing disc is profoundly regional [8,9], and PLF can be applied post hoc to historical LC–MS/MS data (as shown for ageing tendon [25]), further analysis of the DIPPER dataset presents us with a timely opportunity to test: (i) the hypothesis that protein structures (as indicated by peptide yield pattern) are spatially and potentially age-dependent in the IVD and (ii) the ability of PLF to detect protein structural differences within localised tissue regions.

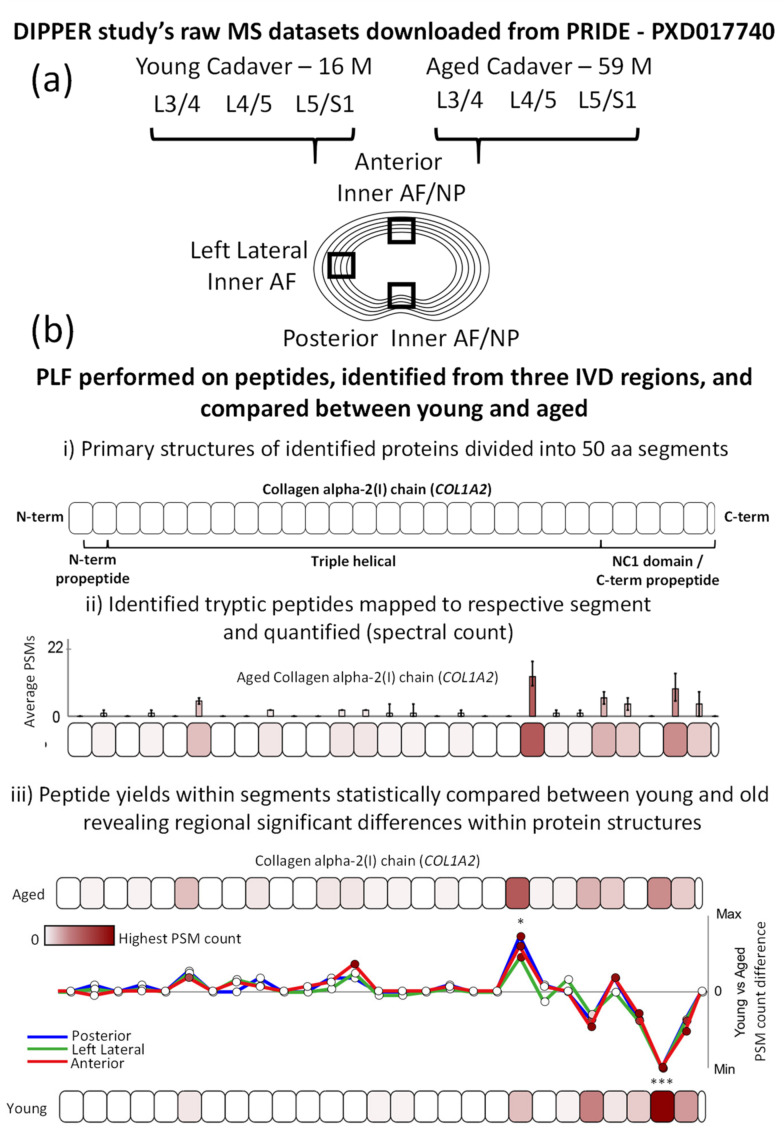

As the inner AF appeared particularly susceptible to matrisomal changes [13], we applied PLF to LC–MS/MS datasets corresponding to the inner AFs of three distinct IVD regions (posterior, left lateral and anterior; Figure 1a). This enabled the detection of structural differences in ECM proteins between aged and young IVDs, which could be further compared between degeneration-prone (posterior and lateral) and -resistant (anterior) regions of the IVD (Figure 1b), revealing potentially age-affected proteins with tissue region-specific peptide yield patterns. Please note, in the following text and figures, proteins are commonly referred to by their gene name (indicated by italics).

Figure 1.

Experimental design for the application of PLF to three distinct regions of young and aged IVDs. (a) Raw LC–MS/MS datasets (from two males, one young [16 years old] and one aged [59 years old]), corresponding to the posterior inner AF/NP, left lateral inner AF and anterior inner AF/NP regions of the L3/4, L4/5 and L5/S1 lower lumbar IVDs were downloaded from the PRIDE repository (PXD017740) [13]. (b) After MS/MS peptide identification, the MPLF webtool [25] was used to perform PLF on the identified peptides and compare peptide yields across protein structures between young and aged discs—three vs. three discs for anterior and left lateral datasets and three vs. two discs for posterior datasets (the young anterior L4/5 disc was omitted from the analysis due to the insufficient number of identified peptides for PLF analysis). As previously described [25], ((b), i) proteins were divided into 50-amino acid (aa)-sized segments; the collagen I α2 chain (COL1A2) is shown here as an example. ((b), ii) Peptides were mapped to their respective segments, summed, normalised between aged and young groups based on the median whole protein spectrum count and averaged for each group (average peptide spectrum match [PSM] count per segment). ((b), iii) Peptide yields in each segment were statistically compared between young and aged IVDs using an unpaired, Bonferroni-corrected, repeated-measures ANOVA (* p ≤ 0.05; *** p ≤ 0.001). To visualise these differences along the protein structure, average PSM counts per segment in the young group were subtracted from those in the aged one and compared between posterior, left lateral and anterior IVD regions.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Peptide Location Fingerprinting Reveals Proteins with Region-Specific Differences between Aged and Young IVDs

MS/MS peptide searches identified 260 posterior, 391 left lateral and 303 anterior inner AF-specific proteins in both young and aged groups (Figure S1; peptide reports: Tables S1–S3). Principal component analyses of peptide spectral counts demonstrated clear separations of data between young and aged discs for all three IVD regions tested (Figure S2), reflecting a global compositional difference in ageing similar to that showcased previously in the DIPPER study [13]. PLF analysis identified a combined total of 268 proteins (across tissue regions) with significant differences in peptide yield patterns along their primary structures (Figure 2a; full PLF analysis reports: Tables S4–S6). When compared to the proteins identified in the DIPPER study with significant differences in relative abundance between aged and young samples (by label-free quantification) [13], PLF identified 119 proteins that were unique to this approach, with significant differences in protein structure but not abundance (Figure S3).

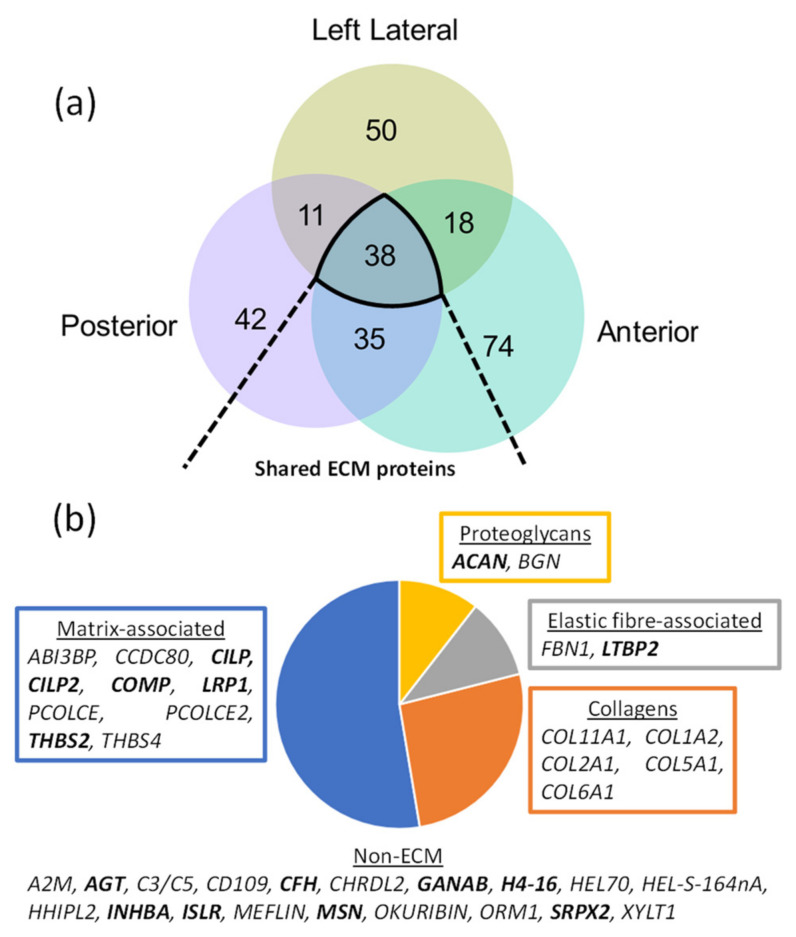

Figure 2.

ECM-associated proteins make up half of the proteins identified with significant, age-associated structural differences in all three IVD regions. PLF revealed 126 proteins in posterior (Table S4), 117 in left lateral (Table S5) and 165 in anterior (Table S6) IVD regions with significant differences in peptide yield between aged and young IVDs, across their structures. (a) Of these, 38 were shared between the three regions. (b) Classification of these shared proteins revealed ECM as the major class, which included several ECM-associated proteins, collagens, two elastic fibre-specific proteins and two proteoglycans. The affected proteins which were uniquely discovered by PLF and not by label-free quantification of abundance in the DIPPER study [13] (Figure S3) are highlighted in bold.

Of the 268 proteins identified with age-associated structural differences, 38 were shared between posterior, lateral and anterior inner AF regions (Figure 2a). Classification of these proteins into ECM-specific protein classes highlighted several matrix-associated proteins, including the major structural collagens of the AF (collagen I [COL1A2] and V [COL5A1]) and NP (collagen II [COL2A1] and VI [COL6A1]), elastic fibre-associated proteins (fibrillin-1 [FBN1] and LTBP2 [LTBP2]) and proteoglycans such as aggrecan (ACAN] as key affected components (Figure 2b). Some of the identified proteins have been linked to disease, including osteoarthritis-associated [28,29] cartilage intermediate layer proteins 1 and 2 (CILP and CILP2), the levels of which were shown to differ significantly between degenerated and non-degenerated AFs and NPs [12], and cell-matrix adhesion-mediating thrombospondins 2 [30] and 4 [31]. The levels of thrombospondin 4 (THBS4) were shown previously in the DIPPER study to be significantly higher in the young inner AF than in the aged one [13]. However, to our knowledge, age-associated structural differences in disc thrombospondin have not been previously shown, although two single-nucleotide polymorphisms were found to be associated with IVD degeneration [32].

The decline of the proteoglycan aggrecan in IVD ageing due to proteolysis by MMPs and aggrecanases is well established [33]. Here, we show evidence of structural differences within the aggrecan core protein between aged and young IVDs which may relate to these mechanisms. Similarly, the degeneration of elastic fibre and collagen architectures are a hallmark of ageing in many connective tissues such as IVD, skin and aorta [34,35,36,37,38]. Our data show that, in the IVD, this process may possibly extend specifically to modification-associated changes in the protein structures of elastic fibre proteins fibrillin-1 and latent TGFβ-binding protein 2 and in multiple α-chains from collagens I, II, V, VI and XI.

To investigate whether the age-associated differences in peptide yield patterns along the primary structure of ECM proteins are consistent between regions, members of these 38 shared, significantly different proteins were examined further.

2.2. Age-Associated Fluctuations in Peptide Yield along the Primary Structures of COL1A2 and PCOLCE Are Markedly Conserved between Posterior, Lateral and Anterior IVD Regions

Both the collagen I α2 chain (COL1A2) and procollagen C-endopeptidase enhancer 1 (PCOLCE; PCPE1) were identified with age-associated modifications to their structures in all three IVD regions (Figure 2b). COL1A2 is a major structural component of collagen I fibrils, forming a tightly bound triple helix alongside two additional α1 chains (COL1A1) within a monomer. The extracellular glycoprotein procollagen C-endopeptidase enhancer 1 (PCOLCE) binds to the C-terminal propeptide of procollagens and drives the activity of tolloid proteinases, procollagen cleavage and their subsequent assembly into fibres [39]. PCOLCE therefore plays a crucial role in collagen deposition and associated morbidities such as fibrosis [40].

Comparisons between posterior, lateral and anterior regions revealed notable, consistent age-associated differences in peptide yield across the protein structures of COL1A2 and PCOLCE. On the C-terminal side of the COL1A2 protein, characteristic significant increase and decrease in peptide yield pattern were observed in aged compared to young, along the primary structure for all three IVD regions (Figure 3a). Similarly, a characteristic increase in peptide yield was seen on the N-terminal side of aged PCOLCE compared to young PCOLCE, followed by a significant decrease in peptide yield on the C-terminal side (Figure 3b). This pattern was also consistent for posterior, lateral and anterior inner AF regions. While there were age-associated differences observed along the structures of both proteins, it is important to consider that peptide yields were also stable between aged and young in many protein regions (such as on the N-terminal side of COL1A2). This lack of difference between young and old was also consistent between IVD regions.

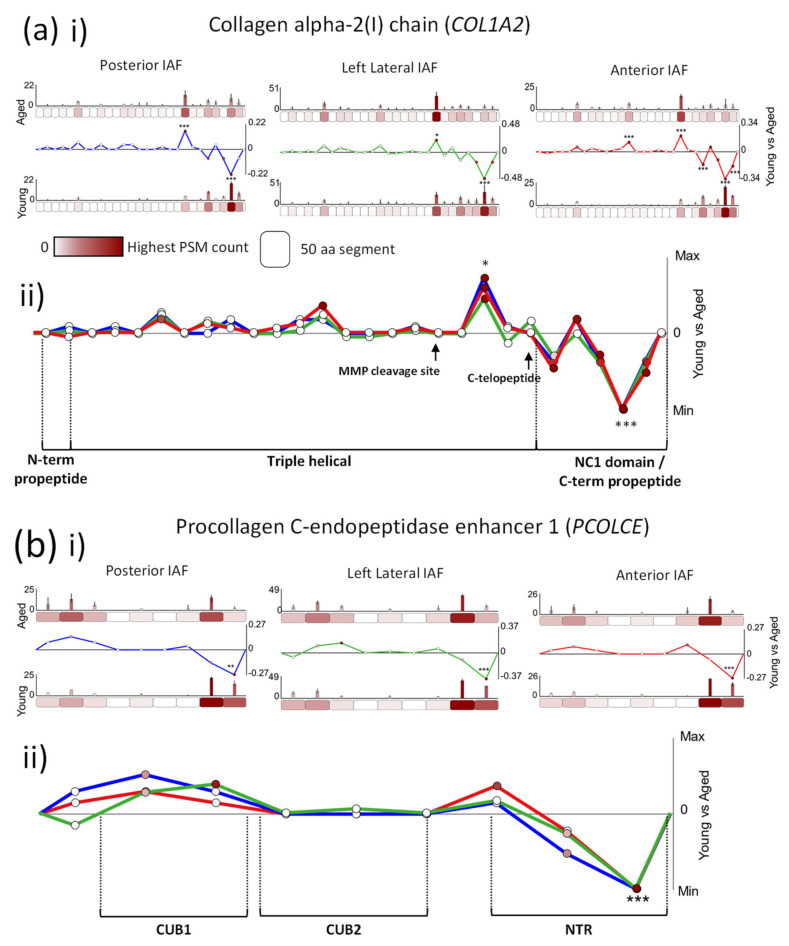

Figure 3.

COL1A2 and PCOLCE protein structures exhibit differences in peptide yield patterns between young and aged proteins, which were conserved in posterior, left lateral and anterior IVD regions. PSMs were summed in each 50-aa protein segment, normalised and averaged for young and aged groups (bar graphs = average, normalised PSMs, error bars = standard deviation). Average PSMs per segment in young were subtracted by those in aged and divided by segment aa length (50) to reveal fluctuations in peptide yield along protein structures (line graph y axes = aged–young PSM counts/segment length, normalised between tissue regions in composite graphs; * p ≤ 0.05; ** p ≤ 0.01; *** p ≤ 0.001, Bonferroni-corrected, repeated-measures ANOVA; black * in composite line graph = significant in all three IVD regions; functional domains, sourced from UniProt, are indicated). ((a), i) Several COL1A2 segments exhibited significant differences in peptide yield between young and aged samples within the C-terminal half of the protein (blue line: posterior, green: left lateral, red: anterior). ((a), ii) Crucially, these differences in peptide yield along the COL1A2 structure are markedly consistent between all the three regions, with a similarly higher peptide yield displayed in segment 20 of aged compared to young and lower peptide yield in the last three segments, nearest to the C-terminus. ((b), i) The last 50-aa segment on the C-terminal end of PCOLCE also exhibited a significantly lower peptide yield in aged compared to young for the inner AFs of all three IVD regions. ((b), ii) Peptide yield difference patterns along the primary structure were also similar between all the three regions, with a consistently higher peptide yield in aged compared to young measured on the N-terminal side of the protein followed by a lower yield in the last two segments near the C-terminal end.

The significantly higher peptide yield, observed on the C-terminal end of young COL1A2 compared to the aged protein, corresponds directly to its non-collagenous (NC1) domain (Figure 3a(ii)). These domains are cleaved prior to fibril assembly [41] by C-proteinases such as bone morphogenic protein-1/tolloid proteinase (BMP1) from fully folded procollagen, releasing a C-terminal propeptide. Since the release of this domain is critical for the formation and assembly of the collagen triple helix protomer [42], its higher detection in the young IVD suggests heightened collagen synthesis compared to the aged one. Also in support of this, the significantly lower peptide yield in aged PCOLCE compared to young PCOLCE, seen on its C-terminal end for all IVD regions, coincides directly with its netrin (NTR) domain (Figure 3b(ii)), critical for the super-stimulation of BMP1 and its cleavage of the collagen NC1 domain prior to fibril assembly [43]. This lower peptide yield in the netrin domain of aged PCOLCE may impact on its interaction with BMP1. It is possible that age-associated changes to PCOLCE structure may have resulted in masking of this protein region, which would explain its lower availability to trypsin and potentially BMP1, also impacting on collagen synthesis. Recent studies of collagen turnover in healthy tendon have shown that collagen is not repaired [44,45] but instead maintained daily, through a cycle of synthesis and degradation that is controlled by the circadian rhythm [46]. It is likely that a similar maintenance program exists in young, healthy AF (compositionally similar to tendon), and here, we show indications that this may deteriorate with age.

A second COL1A2 protein region, located near the C-terminal end of the triple helical domain (Figure 3a(ii)), also differed significantly between aged and young samples (higher peptide yields in aged) for all three IVD regions. As this protein region is located well within the triple helix of collagen I, peptides derived from this domain are likely to be from mature collagen fibrils. In osteoporosis, fragments of the C-terminal telopeptide of collagen I α1 are frequently used as markers of collagen degradation in bone [47,48]. Although the COL1A2 protein region seen here is located upstream of its C-terminal telopeptide (Figure 3a(ii), black arrow), a higher peptide yield in aged IVD may also be indicative of collagen fibril degradation as a consequence of damage accumulation to structure. COL1A2 is a substrate for matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) 1, 2, 3, 8 and 14 [49] (see interaction network Figure S4), all of which were shown to be upregulated in degenerated IVD [50]. All of these enzymes (except MMP3) preferentially cleave the α-chains of collagens I, II and III at a point approximately three-quarters of the way along the mature chain from the N-terminus [51,52]. The COL1A2 region, which had higher peptide yields in aged than in young samples, is located just downstream of this prominent MMP cleavage site (indicated in Figure 3a(ii), black arrow) and corresponds to this degradation fragment, cleaved three-quarters away from the N-terminus. This suggests that chronic exposure to elevated endogenous MMPs, thought to be one of several ageing mechanisms driving the accumulation of damage to long-lived ECM assemblies, could potentially be playing a role in the higher peptide yield observed in the triple-helical domain of aged COL1A2 compared to young COL1A2.

In addition to BMP1, PCOLCE also binds fibronectin [53], LTBP1, thrombospondin 1, aggrecan and biglycan [54] (and their associated glycosaminoglycans), and COL1A2 binds COL5A1 [55] within the wider ECM network (Figure S4). If the structural differences seen in aged PCOLCE and COL1A2 compared to the young molecules (Figure 3) result in the impediment of these interactions, it could drive the deterioration of the wider proteostasis [13].

The remarkable consistency in the age-associated peptide yield patterns of COL1A2 and PCOLCE structures between the posterior, lateral and anterior regions of the inner AF (Figure 3) is an interesting observation, as it indicates the possibility that ageing mechanisms may be at play tissue-wide. However, some proteins exhibited significant structural differences in peptide yield, which were entirely tissue region-specific.

2.3. Age-Associated Peptide Yield Patterns along the Primary Structures of the α1 Chains of Collagens II and V and Aggrecan Exhibit Regional Tissue Specificity within the IVD

A sub-population of IVD proteins showed significant differences in structure which were region-specific (42 for posterior, 50 for lateral and 74 for anterior) between young and aged samples (Figure 4). These proteins included several prominent ECM components such as tenascin (TNC) and proteoglycan 4 (PRG4) (exclusive to posterior), collagen XIV α1 (COL14A1) and osteomodulin (OMD) unique to left lateral) and EMILIN-1 (EMILIN1) and nidogen 2 (NID2) (exclusive to anterior) (Figure S5).

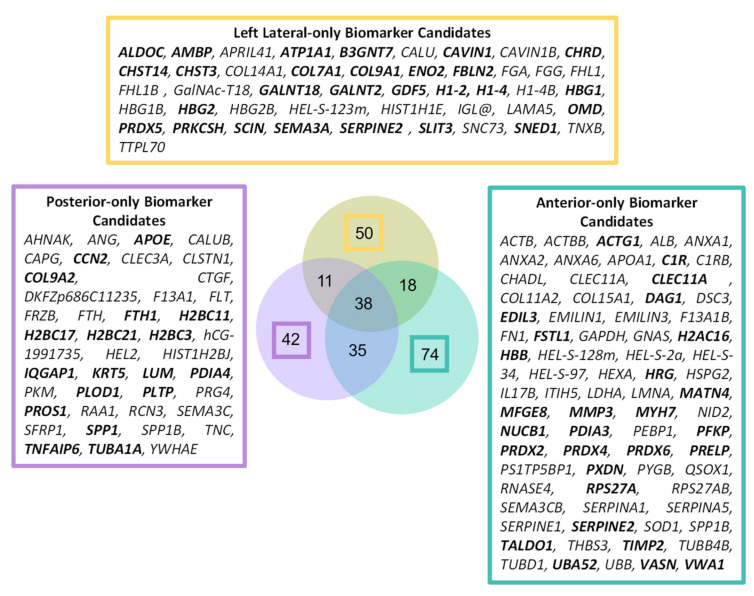

Figure 4.

A total of 166 proteins were identified with significant, age-associated structural differences that were entirely IVD-region specific. The affected proteins which were uniquely discovered by PLF and not by label-free quantification of abundance in the DIPPER study (Figure S3) [13] are highlighted in bold.

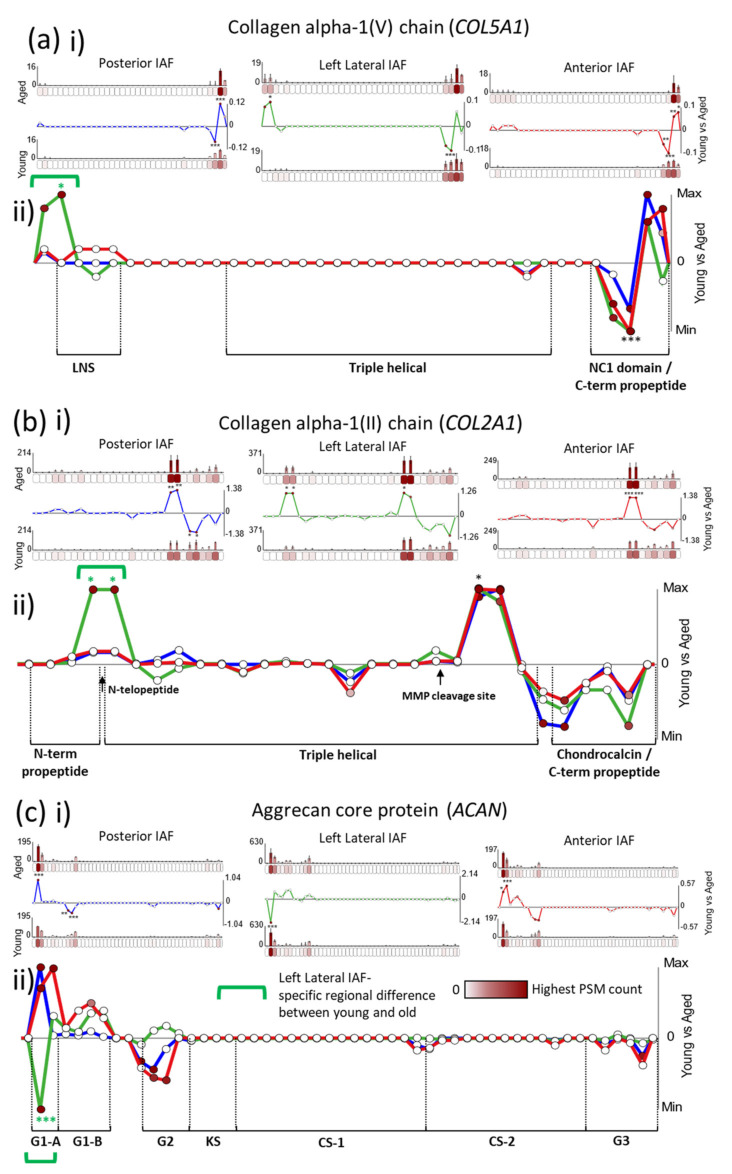

Importantly, some proteins even displayed differences in peptide yield between young and aged samples, which were shared between all AF regions (Figure 2b) on one side of their protein structures but region-specific on the other side, as seen for collagen V α1 (COL5A1), collagen II α1 (COL2A1) and aggrecan core protein (ACAN) (Figure 5). For COL5A1, a characteristic significant decrease in peptide yield in aged compared to young samples, followed by an increase, can be seen in the C-terminal end, along the primary structure, which remains consistent for all three IVD regions (Figure 5a). This is similar also for COL2A1, which exhibited the same significant rise and fall in peptide yield along its chain in all three IVD regions, on its C-terminal side (Figure 5b). However, both α1 chains of collagens V and II displayed additional N-terminal, significant increases in peptide yield in aged compared to young samples that were lateral-specific (green brackets in Figure 5a,b(ii)). Contrastingly, a significantly higher peptide yield was observed near the N-terminal end of aged aggrecan than in the young one, for both the posterior and the anterior inner AF regions (Figure 5c). However, this pattern was reversed for left lateral, with the same protein region yielding significant lower peptide counts in aged aggrecan than in young aggrecan (green bracket in Figure 5c(ii)).

Figure 5.

COL5A1, COL2A1 and aggrecan all exhibit lateral, inner AF-specific differences in peptide yield not seen in the posterior or anterior IVD regions. PSMs were summed in each 50-aa protein segment, normalised and averaged for young and aged groups (bar graphs = average, normalised PSMs, error bars = standard deviation). Average PSMs per segment in the young group were subtracted by those in the aged one and divided by segment aa length (50) to reveal fluctuations in peptide yield along protein structures (line graph y axes = aged–young PSM counts/segment length, normalised between tissue regions in composite graphs; * p ≤ 0.05; ** p ≤ 0.01; *** p ≤ 0.001, Bonferroni-corrected, repeated-measures ANOVA; black * in composite line graph = significant in all three IVD regions; functional domains, sourced from UniProt, are indicated). ((a), i) Several segments on the C-terminal end of COL5A1 exhibited significant differences in peptide yields between young and aged samples for all three IVD regions. However, a left lateral-specific significant difference in yield was also observed in its second segment, on the N-terminal end of the protein. ((a), ii) Fluctuations in COL5A1 peptide yield on the C-terminal end follow a similar pattern in all three regions, with a consistent fall and rise of peptide yield observed in aged compared to young samples for the last four segments of its primary structure. However, a clear left lateral-specific increase in peptide yield can also be seen on the N-terminal end. ((b), i) COL2A1 also had several protein segments on the C-terminal side which exhibited significant differences in peptide yield. ((b), ii) These displayed a characteristic rise-and-fall peptide yield pattern in aged compared to young samples, which were markedly consistent between the three IVD regions. However, once again, two COL2A1 segments on the N-terminal side of the protein exhibited significantly higher yields for aged than for young samples that were unique to the left lateral region of the disc. ((c), i) Segments two and three on the N-terminal side of the aggrecan protein (ACAN) also exhibited significant differences in peptide yield between young and aged samples. ((c), ii) These differences were significantly higher in aged aggrecan within the posterior and anterior inner AF regions, compared to young aggrecan, but significantly lower in the left lateral region.

The tissue region-conserved, higher peptide yields seen on the C-terminal ends of young COL5A1 and COL2A1 compared to the aged one (Figure 5a,b(ii)) also corresponded to their cleaved C-terminal propeptides, as seen for COL1A2 (Figure 3a(ii)). This once again reflects a possible tissue-wide perturbation in collagen maintenance [46] in aged compared to young discs, for collagen II and V fibrils in addition to collagen I. Interestingly, we noticed that the C-terminal propeptides of COL1A2 and COL5A1 are enriched in ROS-sensitive residues [56] (Figure S6), indicating a potential role for these fragments as antioxidants, whose presence is reduced in aged IVD (Figure 3a and Figure 5a(ii)). Again in common with COL1A2 (Figure 3a(ii)), aged COL2A1 also exhibited an AF region-wide significant increase in peptide yield compared to young COL2A1, downstream to a prominent MMP cleavage site (Figure 5b(ii), black arrow) [51,52], possibly suggesting that chronic degradation of collagen II by MMPs may be an ageing mechanism at play.

The lateral-specific, significant rise in peptide yield seen on the N-terminal end of aged COL5A1 compared to young COL5A1 (green bracket in Figure 5a(ii)) corresponded partly to its laminin G-like (LNS) domain [57]. Although capable of matriglycan interactions [58], the function of this domain specifically within collagen V fibrils remains elusive. Here, we show clear evidence that the binding availability of the LNS domain is significantly higher exclusively in left lateral aged COL5A1 than for all other groups (young, aged and posterior, anterior). For COL2A1, these aged, lateral-specific increases in peptide yield (Figure 5b) corresponded directly to the interface between the N-terminal propeptide and the triple-helical region, where the telopeptide is located. Collectively, these observations in COL5A1 and COL2A1 may indicate the degradation of their respective collagen V and II fibrils exclusively in the lateral regions of the AF.

The heightened peptide yield observed near the N-terminal end of aged posterior and anterior ACAN compared to young ACAN, which was reversed (lower) for the aged left lateral protein, coincides with the immunoglobulin fold of its globular G1-A domain (Figure 5c(ii)), [33]. The A subdomain in particular is critical for stabilising and enhancing the binding of its adjacent B subdomains to hyaluronan [59]. This interaction is crucial for the anchorage of aggrecan to collagen fibrils in articular cartilage [60] (Figure S4). Several ageing mechanisms have been suggested for age-related changes previously observed in aggrecan structure. Interestingly, Sivan et al. proposed that, as a consequence of elevated proteases in ageing discs, proteolysis on the N-terminal end of aggrecan results in only the G1 domain remaining bound to the hyaluronan, which leads to the accumulation of unbound aggrecan fragments in the NP [33]. Additionally, aged aggrecan is known to accumulate AGEs on its lysine residues in vivo [37], and lysine residues within the G1 domain are critical for its hyaluronan interaction [33]. Collectively, these insights highlight the functional importance of this N-terminal protein region in aggrecan and may provide clues for the mechanisms (e.g., proteolysis or glycation) behind the tissue region-specific differences in peptide yield observed within this protein region between aged and young samples.

It is important to note that these displays of tissue region-specific modifications to protein structures were not limited to ECM proteins. For instance, similar peptide pattern differences were observed within the immune regulator complement factor H (CFH) (Figure S7), which also exhibited anterior inner AF-specific regional difference between young and aged samples, on the C-terminal side of its primary structure, and also tissue region-wide differences near its N-terminus. CFH plays a key role in regulating the progression of inflammation in age-related diseases such as vascular atherosclerosis [61] and macular degeneration [62]. The structural modifications observed here suggest that similar CFH-driven inflammation pathways may be involved in regions of the inner AF.

Collectively, these observations indicate not only the possibility of regional downstream consequences of ageing to major ECM components, on a molecular level, but also the potential of mechanisms acting exclusively within specific IVD regions.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Dataset Collection

In this study, young and aged IVD LC–MS/MS datasets were sourced from the Proteomics Identification Database (PRIDE)—Project ID PXD017740. These were originally generated for an earlier study which led to the spatiotemporal IVD proteomic resource DIPPER—http://www.sbms.hku.hk/dclab/DIPPER/ (last accessed 13 September 2021). For detailed methods of human tissue sourcing, sample preparation and MS, please refer to this original publication [13]. In brief, the datasets were generated by LC–MS/MS (data-dependant acquisition on an Orbitrap Fusion Lumos Tribrid Mass Spectrometer) from trypsin/LysC-digested whole protein samples extracted from 11 separate regions of IVDs—three discs (L3/4, L4/5 and L5/S1)—sourced from two male cadaveric human lumbar spines, one young (16-year-old) and one aged (59-year-old). Prior to LC–MS/MS, peptides were fractionated into four samples per IVD region by high-pH reversed-phase peptide fractionation and separately analysed. For this study, only 3 out of the 11 IVD regions available for analysis were evaluated by PLF: the anterior, left lateral and posterior inner AF/NPs (Figure 1a). PLF measures the relative difference in regional digestibility within proteins between two groups, and so it is important to note that the more preserved the native quaternary structure of the protein is, the more differences should be identifiable using this approach. Unfortunately, all protein extraction methods will inherently change the higher order structure of a protein. However, because all proteins in the samples tested were originally extracted using identical sample preparation methods [13], the regional differences measured are therefore a direct reflection of their native structure, prior to extraction. For this reason, PLF can be applied to historic datasets regardless of the extraction protocol used, as we have shown previously for ageing tendon [25].

It is important to highlight that the acquisition of non-degenerated human IVD tissue is challenging, and such samples from young and aged individuals are rare. Although we acknowledge that this detailed analysis was performed on one young and one aged individual only, this limitation is outweighed by the merits of the study, since our findings are based on human in vivo data and, therefore, of direct clinical relevance.

3.2. Peptide Identification

Raw MS spectrum files were converted to Mascot MGF files using RawConverter (Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, CA, USA) [63], and peak spectra searched against the Uniprot human database (Swiss-Prot and TreEMBL; 2018) [64] using Mascot (Matrix Science, MA, USA). MS/MS ion searches were performed using the following parameters—instrument: ESI-TRAP; database: Swissprot_TreEMBL_2018_01; species: Homo sapiens (161,629 protein isoforms); fragment tolerance: 20 ppm; parent tolerance: 6 ppm (monoisotopic); fixed modifications: +58 Da on C (carboxymethyl); variable modifications: +16 Da on M (oxidation); digestion enzyme: trypsin; max missed cleavages: 2; peptide charge: 2+, 3+ and 4+. Mascot search results were exported as DAT files.

Scaffold 5 (Proteome Software, Portland, OR, USA) was then used to generate high-confidence PSMs by standard LFDR scoring. Mascot DAT files were imported into Scaffold 5, and individual fractionated peptide sample datasets were combined to form a single IVD region sample dataset using MudPIT (Stowers Institute, Kansas, MO, USA) [65]. Only peptides exclusive to their matched proteins and with a peptide probability of 95% minimum were used for PLF analysis, giving a low false discovery rate (FDR) of 0.6% per group (posterior, left lateral and anterior). Peptide FDR was calculated by the PeptideProphet algorithm (open source: http://peptideprophet.sourceforge.net/, accessed on 13 September 2021) [66] within Scaffold 5 using peptide probabilities designated by the Trans-Proteomic Pipeline. CSV files containing peptide lists were exported from Scaffold 5 for PLF analysis (Tables S1–S3).

3.3. Peptide Location Fingerprinting

Peptide lists were imported into our MPLF webtool (accessible at https://www.manchesterproteome.manchester.ac.uk/#/MPLF) (accessed on 13 September 2021), and three separate PLF analyses were performed on young vs. aged molecules for each IVD region (posterior, left lateral and anterior). As previously described [25] (Figure 1b), protein primary sequences were computationally divided into 50-aa-sized segments, and peptide sequences and their spectrum counts were mapped and summed within each segment. Sequences spanning two adjoining segments were counted in both. In order to identify differences in peptide yield along protein structures that are independent of differences in whole protein abundance, peptide counts in each 50-aa segment were normalised based on the experiment-wide (young and aged), median whole spectrum count of its corresponding protein. As a result of this protein-specific normalisation, each protein was treated as its own separate experiment during statistical comparison. Average, normalised peptide counts in each segment for the young group were subtracted from those in the aged group and divided by the segment aa length (50) to reveal regional fluctuations in peptide yield within the primary structures of proteins. Average, normalised peptide counts per protein segment were statistically compared between young and aged groups using unpaired, Bonferroni-corrected, repeated-measures ANOVAs (Tables S4–S6). Proteins which were only present in one group (young or aged) were excluded from the analysis. For more information on PLF and the MPLF webtool, please refer to our earlier publication [25].

3.4. Interaction Network Analysis

Exemplar proteins COL1A2, PCOLCE, COL5A1, COL2A1 and aggrecan were used to construct an experimentally identified interaction network (Figure S4). ECM protein interactions were derived using Matrix DB [67], which were constructed and visualised using Cytoscape 3.4.0. (open source: https://cytoscape.org/, accessed on 13 September 2021) [68].

4. Conclusions

Although ageing and degeneration of IVDs are the result of genetics, environments and their interplays [5], this study focused predominantly on the identification of ECM proteins that may have accumulated modifications to structure over time. This was successfully enabled through the application of PLF to historic LC–MS/MS datasets generated from the inner AF of posterior, lateral and anterior regions of young and aged human IVDs. We demonstrated that, although many of these affected proteins were region-specific, several were identified in all three regions tested. Some of these shared proteins, such as COL1A2 and PCOLCE, exhibited remarkably consistent age-associated differences in peptide yields along their protein structures between all tissue regions. This indicates the possibility that the same mechanisms of ageing may act on proteins across the entire tissue, leading to similar molecular-level consequences. However, several proteins identified, such as COL5A1, COL2A1 and ACAN, also had lateral-specific differences in structure between aged and young samples, which indicates the possibility that some mechanisms acting on proteins may also be exclusive to certain tissue regions. This suggests that protein structures are potentially spatially and age-dependent in the IVD and that PLF is capable of detecting differences within localised tissue regions. This study highlights the merits of PLF as an interrogator of structural changes within proteins and potentially as a powerful tool for aiding biomarker discovery [25], which, in tandem with relative protein quantification (achieved in the DIPPER study [13]), allows for a more complete assessment of tissue proteostasis.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Karl Kadler for the illuminating discussions with regard to collagen data interpretation. We also acknowledge the University of Manchester research IT services for their aid in hosting and running of the MPLF webtool.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ijms221910408/s1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.E., M.J.S., A.T.; methodology, A.E.; software, M.O.; validation, A.E.; formal analysis, A.E.; investigation, A.E.; resources, M.J.S.; data curation, A.E., M.O.; writing—original draft preparation, A.E.; writing—review and editing, A.E., M.O., P.C., V.T., J.A.H., A.T., D.C., M.J.S.; visualization, A.E., M.J.S., A.T., D.C.; supervision, M.J.S.; project administration, A.E., M.J.S.; funding acquisition, A.E., M.J.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was jointly funded by the Manchester Institute for Collaborative Research on Ageing (MICRA), Manchester and Walgreens Boots Alliance, Nottingham, UK. D.C. is supported by The Research Council of Hong Kong (E-HKU703/18), P.C. by the Shenzhen Health Commission (SZHC) “Key Medical Discipline Construction Fund” (SZXK077) and M.O. by the Wellcome Trust (206194). M.J.S. and J.A.H. would like to acknowledge funding from the UK Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EP/V011065/1).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were not required for this study as it was conducted using publicly available datasets from the PRIDE database, already published [13] and ethically approved.

Informed Consent Statement

This study was conducted using publicly available datasets from the PRIDE database already published [13]. Informed consent was obtained as part of that already published study.

Data Availability Statement

The LC–MS/MS raw data were downloaded from the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE repository; dataset identifier PXD017740. Interactive protein schematics showcasing the PLF analysis of these IVD datasets can be viewed (and the comparison datasets downloaded) via the MPLF webtool—https://www.manchesterproteome.manchester.ac.uk/#/MPLF by selecting the “Location Fingerprinter” tab (accessed on 13 September 2021). The DIPPER resource [13] is accessible at: http://www.sbms.hku.hk/dclab/DIPPER/ (accessed on 13 September 2021).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest. Walgreens Boots Alliance approved the submission of this manuscript but exerted no editorial control.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Alonso F., Hart D.J. Intervertebral Disk. In: Aminoff M.J., Daroff R.B., editors. Encyclopedia of the Neurological Sciences. 2nd ed. Academic Press; Oxford, UK: 2014. pp. 724–729. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hoy D., March L., Brooks P., Blyth F., Woolf A., Bain C., Williams G., Smith E., Vos T., Barendregt J. The global burden of low back pain: Estimates from the Global Burden of Disease 2010 study. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2014;73:968. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mirza S.K. Intervertebral Disk. In: Aminoff M.J., Daroff R.B., editors. Encyclopedia of the Neurological Sciences. 2nd ed. Academic Press; New York, NY, USA: 2003. pp. 683–689. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ohnishi T., Novais E.J., Risbud M.V. Alterations in ECM signature underscore multiple sub-phenotypes of intervertebral disc degeneration. Matrix Biol. Plus. 2020;6–7:100036. doi: 10.1016/j.mbplus.2020.100036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kepler C.K., Ponnappan R.K., Tannoury C.A., Risbud M.V., Anderson D.G. The molecular basis of intervertebral disc degeneration. Spine J. 2013;13:318–330. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2012.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eyre D.R., Muir H. Types I and II collagens in intervertebral disc. Interchanging radial distributions in annulus fibrosus. Biochem. J. 1976;157:267. doi: 10.1042/bj1570267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vergroesen P.-P.A., Kingma I., Emanuel K.S., Hoogendoorn R.J.W., Welting T.J., van Royen B.J., van Dieën J.H., Smit T.H. Mechanics and biology in intervertebral disc degeneration: A vicious circle. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2015;23:1057–1070. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2015.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wilke H.-J., Kienle A., Maile S., Rasche V., Berger-Roscher N. A new dynamic six degrees of freedom disc-loading simulator allows to provoke disc damage and herniation. Eur. Spine J. 2016;25:1363–1372. doi: 10.1007/s00586-016-4416-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheung K.M.C., Karppinen J., Chan D., Ho D.W.H., Song Y.-Q., Sham P., Cheah K.S.E., Leong J.C.Y., Luk K.D.K. Prevalence and pattern of lumbar magnetic resonance imaging changes in a population study of one thousand forty-three individuals. Spine. 2009;34:934–940. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181a01b3f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gruber H.E., Hoelscher G.L., Ingram J.A., Bethea S., Zinchenko N., Hanley E.N. Variations in aggrecan localization and gene expression patterns characterize increasing stages of human intervertebral disk degeneration. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 2011;91:534–539. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2011.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Collin E.C., Carroll O., Kilcoyne M., Peroglio M., See E., Hendig D., Alini M., Grad S., Pandit A. Ageing affects chondroitin sulfates and their synthetic enzymes in the intervertebral disc. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2017;2:1–8. doi: 10.1038/sigtrans.2017.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yee A., Lam M.P.Y., Tam V., Chan W.C.W., Chu I.K., Cheah K.S.E., Cheung K.M.C., Chan D. Fibrotic-like changes in degenerate human intervertebral discs revealed by quantitative proteomic analysis. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2016;24:503–513. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2015.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tam V., Chen P., Yee A., Solis N., Klein T., Kudelko M., Sharma R., Chan W.C.W., Overall C.M., Haglund L. DIPPER, a spatiotemporal proteomics atlas of human intervertebral discs for exploring ageing and degeneration dynamics. eLife. 2020;9:e64940. doi: 10.7554/eLife.64940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shapiro S.D., Endicott S.K., Province M.A., Pierce J.A., Campbell E.J. Marked longevity of human lung parenchymal elastic fibers deduced from prevalence of D-aspartate and nuclear weapons-related radiocarbon. J. Clin. Investig. 1991;87:1828–1834. doi: 10.1172/JCI115204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sivan S.-S., Wachtel E., Tsitron E., Sakkee N., van der Ham F., DeGroot J., Roberts S., Maroudas A. Collagen turnover in normal and degenerate human intervertebral discs as determined by the racemization of aspartic acid. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:8796. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M709885200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gruber H.E., Hanley E.N. Observations on morphologic changes in the aging and degenerating human disc: Secondary collagen alterations. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2002;3:9. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-3-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Craddock R.J., Hodson N.W., Ozols M., Shearer T., Hoyland J.A., Sherratt M.J. Extracellular matrix fragmentation in young, healthy cartilaginous tissues. Eur. Cells Mater. 2018;35:34. doi: 10.22203/eCM.v035a04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xu H., Mei Q., Xu B., Liu G., Zhao J. Expression of matrix metalloproteinases is positively related to the severity of disc degeneration and growing age in the East Asian lumbar disc herniation patients. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 2014;70:1219–1225. doi: 10.1007/s12013-014-0045-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hoy R.C., D’Erminio D.N., Krishnamoorthy D., Natelson D.M., Laudier D.M., Illien-Jünger S., Iatridis J.C. Advanced glycation end products cause RAGE-dependent annulus fibrosus collagen disruption and loss identified using in situ second harmonic generation imaging in mice intervertebral disk in vivo and in organ culture models. JOR Spine. 2020;3:e1126. doi: 10.1002/jsp2.1126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alkhatib B., Gawri R., Önnerfjord P., Ouellet J., Roughley P., Steffen T., Haglund L.A. Chondroadherin Fragmentation as a Biochemical Marker for Early Stage Disk Degeneration. Glob. Spine J. 2012;2:s-0032. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1319867. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Feng C., Yang M., Lan M., Liu C., Zhang Y., Huang B., Liu H., Zhou Y. ROS: Crucial intermediators in the pathogenesis of intervertebral disc degeneration. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2017;2017:5601593. doi: 10.1155/2017/5601593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Babu N.S., Krishnan S., Swamy C.V.B., Subbaiah G.P.V., Reddy A.V.G., Idris M.M. Quantitative proteomic analysis of normal and degenerated human intervertebral disc. Spine J. 2016;16:989. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2016.03.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rajasekaran S., Tangavel C., Soundararajan D.C.R., Nayagam S.M., Matchado M.S., Muthurajan R., Anand K.S.S.V., Rajendran S., Shetty A.P., Kanna R.M. Proteomic Signatures of Healthy Intervertebral Discs From Organ Donors: A Comparison With Previous Studies on Discs From Scoliosis, Animals, and Trauma. Neurospine. 2020;17:426. doi: 10.14245/ns.2040056.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ye D., Liang W., Dai L., Zhou L., Yao Y., Zhong X., Chen H., Xu J. Comparative and quantitative proteomic analysis of normal and degenerated human annulus fibrosus cells. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2015;42:530–536. doi: 10.1111/1440-1681.12386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ozols M., Eckersley A., Mellody K.T., Mallikarjun V., Warwood S., O’Cualain R., Knight D., Watson R.E.B., Griffiths C.E.M., Swift J., et al. Peptide location fingerprinting reveals modification-associated biomarker candidates of ageing in human tissue proteomes. Aging Cell. 2021;20:e13355. doi: 10.1111/acel.13355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eckersley A., Ozols M., O’Cualain R., Keevill E.J., Foster A., Pilkington S., Knight D., Griffiths C.E.M., Watson R.E.B., Sherratt M.J. Proteomic fingerprints of damage in extracellular matrix assemblies. Matrix Biol. Plus. 2020;5:100027. doi: 10.1016/j.mbplus.2020.100027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eckersley A., Mellody K.T., Pilkington S., Griffiths C.E.M., Watson R.E.B., O’Cualain R., Baldock C., Knight D., Sherratt M.J. Structural and compositional diversity of fibrillin microfibrils in human tissues. J. Biol. Chem. 2018;293:5117. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA117.001483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tsuruha J., Masuko-Hongo K., Kato T., Sakata M., Nakamura H., Nishioka K. Implication of cartilage intermediate layer protein in cartilage destruction in subsets of patients with osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44:838–845. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200104)44:4<838::AID-ANR140>3.0.CO;2-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bernardo B.C., Belluoccio D., Rowley L., Little C.B., Hansen U., Bateman J.F. Cartilage intermediate layer protein 2 (CILP-2) is expressed in articular and meniscal cartilage and down-regulated in experimental osteoarthritis. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:37758–37767. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.248039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bornstein P., Agah A., Kyriakides T.R. The role of thrombospondins 1 and 2 in the regulation of cell–matrix interactions, collagen fibril formation, and the response to injury. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2004;36:1115–1125. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2004.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Subramanian A., Schilling T.F. Thrombospondin-4 controls matrix assembly during development and repair of myotendinous junctions. eLife. 2014;3:e02372. doi: 10.7554/eLife.02372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yuan B., Ji W., Fan B., Zhang B., Zhao Y., Li J. Association analysis between thrombospondin-2 gene polymorphisms and intervertebral disc degeneration in a Chinese Han population. Medicine. 2018;97:e9586. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000009586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sivan S.S., Wachtel E., Roughley P. Structure, function, aging and turnover of aggrecan in the intervertebral disc. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gen. Subj. 2014;1840:3181–3189. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2014.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sherratt M.J. Tissue elasticity and the ageing elastic fibre. Age. 2009;31:305–325. doi: 10.1007/s11357-009-9103-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Watson R.E.B., Griffiths C.E.M., Craven N.M., Shuttleworth C.A., Kielty C.M. Fibrillin-rich microfibrils are reduced in photoaged skin. Distribution at the dermal-epidermal junction. J. Investig. Dermatol. 1999;112:782–787. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.1999.00562.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lovell C.R., Smolenski K.A., Duance V.C., Light N.D., Young S., Dyson M. Type I and III collagen content and fibre distribution in normal human skin during ageing. Br. J. Dermatol. 1987;117:419–428. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1987.tb04921.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sivan S.S., Tsitron E., Wachtel E., Roughley P., Sakkee N., Van Der Ham F., Degroot J., Maroudas A. Age-related accumulation of pentosidine in aggrecan and collagen from normal and degenerate human intervertebral discs. Biochem. J. 2006;399:29–35. doi: 10.1042/BJ20060579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Urabe G., Hoshina K., Shimanuki T., Nishimori Y., Miyata T., Deguchi J. Structural analysis of adventitial collagen to feature aging and aneurysm formation in human aorta. J. Vasc. Surg. 2016;63:1341–1350. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2014.12.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vadon-Le Goff S., Kronenberg D., Bourhis J.-M., Bijakowski C., Raynal N., Ruggiero F., Farndale R.W., Stöcker W., Hulmes D.J.S., Moali C. Procollagen C-proteinase Enhancer Stimulates Procollagen Processing by Binding to the C-propeptide Region Only. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:38932–38938. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.274944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lagoutte P., Bettler E., Vadon-Le Goff S., Moali C. Procollagen C-proteinase enhancer-1 (PCPE-1), a potential biomarker and therapeutic target for fibrosis. Matrix Biol. Plus. 2021;11:100062. doi: 10.1016/j.mbplus.2021.100062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Canty E.G., Kadler K.E. Procollagen trafficking, processing and fibrillogenesis. J. Cell Sci. 2005;118:1341–1353. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Khoshnoodi J., Cartailler J.-P., Alvares K., Veis A., Hudson B.G. Molecular Recognition in the Assembly of Collagens: Terminal Noncollagenous Domains Are Key Recognition Modules in the Formation of Triple Helical Protomers. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:38117–38121. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R600025200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bekhouche M., Kronenberg D., Vadon-Le Goff S., Bijakowski C., Lim N.H., Font B., Kessler E., Colige A., Nagase H., Murphy G., et al. Role of the Netrin-like Domain of Procollagen C-Proteinase Enhancer-1 in the Control of Metalloproteinase Activity. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:15950–15959. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.086447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Heinemeier K.M., Schjerling P., Øhlenschlæger T.F., Eismark C., Olsen J., Kjær M. Carbon-14 bomb pulse dating shows that tendinopathy is preceded by years of abnormally high collagen turnover. FASEB J. 2018;32:4763–4775. doi: 10.1096/fj.201701569R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Heinemeier K.M., Schjerling P., Heinemeier J., Magnusson S.P., Kjaer M. Lack of tissue renewal in human adult Achilles tendon is revealed by nuclear bomb 14C. FASEB J. 2013;27:2074–2079. doi: 10.1096/fj.12-225599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chang J., Garva R., Pickard A., Yeung C.Y.C., Mallikarjun V., Swift J., Holmes D.F., Calverley B., Lu Y., Adamson A., et al. Circadian control of the secretory pathway maintains collagen homeostasis. Nat. Cell Biol. 2020;22:74–86. doi: 10.1038/s41556-019-0441-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Song L. Chapter One—Calcium and Bone Metabolism Indices. In: Makowski G.S., editor. Advances in Clinical Chemistry. Volume 82. Elsevier; Amsterdam, The Netherlands: 2017. pp. 1–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Christgau S., Rosenquist C., Alexandersen P., Bjarnason N.H., Ravn P., Fledelius C., Herling C., Qvist P., Christiansen C. Clinical evaluation of the Serum CrossLaps One Step ELISA, a new assay measuring the serum concentration of bone-derived degradation products of type I collagen C-telopeptides. Clin. Chem. 1998;44:2290–2300. doi: 10.1093/clinchem/44.11.2290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Packard B.Z., Artym V.V., Komoriya A., Yamada K.M. Direct visualization of protease activity on cells migrating in three-dimensions. Matrix Biol. 2009;28:3–10. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2008.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang W.-J., Yu X.-H., Wang C., Yang W., He W.-S., Zhang S.-J., Yan Y.-G., Zhang J. MMPs and ADAMTSs in intervertebral disc degeneration. Clin. Chim. Acta. 2015;448:238–246. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2015.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chung L., Dinakarpandian D., Yoshida N., Lauer-Fields J.L., Fields G.B., Visse R., Nagase H. Collagenase unwinds triple-helical collagen prior to peptide bond hydrolysis. EMBO J. 2004;23:3020–3030. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Laronha H., Caldeira J. Structure and function of human matrix metalloproteinases. Cells. 2020;9:1076. doi: 10.3390/cells9051076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Weiss T., Brusel M., Rousselle P., Kessler E. The NTR domain of procollagen C-proteinase enhancer-1 (PCPE-1) mediates PCPE-1 binding to syndecans-1,-2 and-4 as well as fibronectin. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2014;57:45–53. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2014.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Salza R., Peysselon F., Chautard E., Faye C., Moschcovich L., Weiss T., Perrin-Cocon L., Lotteau V., Kessler E., Ricard-Blum S. Extended interaction network of procollagen C-proteinase enhancer-1 in the extracellular matrix. Biochem. J. 2014;457:137–149. doi: 10.1042/BJ20130295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Symoens S., Renard M., Bonod-Bidaud C., Syx D., Vaganay E., Malfait F., Ricard-Blum S., Kessler E., Van Laer L., Coucke P. Identification of binding partners interacting with the α1-N-propeptide of type V collagen. Biochem. J. 2011;433:371–381. doi: 10.1042/BJ20101061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ozols M., Eckersley A., Platt C.I., Stewart-McGuinness C., Hibbert S.A., Revote J., Li F., Griffiths C.E.M., Watson R.E.B., Song J. Predicting Proteolysis in Complex Proteomes Using Deep Learning. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021;22:3071. doi: 10.3390/ijms22063071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fallahi A., Kroll B., Warner L.R., Oxford R.J., Irwin K.M., Mercer L.M., Shadle S.E., Oxford J.T. Structural model of the amino propeptide of collagen XI α1 chain with similarity to the LNS domains. Protein Sci. 2005;14:1526–1537. doi: 10.1110/ps.051363105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hohenester E. Laminin G-like domains: Dystroglycan-specific lectins. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2019;56:56–63. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2018.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Watanabe H., Cheung S.C., Itano N., Kimata K., Yamada Y. Identification of hyaluronan-binding domains of aggrecan. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:28057–28065. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.44.28057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kiani C., Liwen C., Wu Y.J., Albert J.Y.E.E., Burton B.Y. Structure and function of aggrecan. Cell Res. 2002;12:19–32. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7290106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Calippe B., Augustin S., Beguier F., Charles-Messance H., Poupel L., Conart J.-B., Hu S.J., Lavalette S., Fauvet A., Rayes J. Complement factor H inhibits CD47-mediated resolution of inflammation. Immunity. 2017;46:261–272. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2017.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Klein R., Knudtson M.D., Klein B.E.K., Wong T.Y., Cotch M.F., Liu K., Cheng C.Y., Burke G.L., Saad M.F., Jacobs D.R., Jr. Inflammation, complement factor h, and age-related macular degeneration: The Multi-ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Ophthalmology. 2008;115:1742–1749. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2008.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.He L., Diedrich J., Chu Y.-Y., Yates J.R., III Extracting accurate precursor information for tandem mass spectra by RawConverter. Anal. Chem. 2015;87:11361–11367. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.5b02721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Consortium U. UniProt: The universal protein knowledgebase. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;45:D158–D169. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw1099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Washburn M.P., Wolters D., Yates J.R. Large-scale analysis of the yeast proteome by multidimensional protein identification technology. Nat. Biotechnol. 2001;19:242–247. doi: 10.1038/85686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Keller A., Nesvizhskii A.I., Kolker E., Aebersold R. Empirical statistical model to estimate the accuracy of peptide identifications made by MS/MS and database search. Anal. Chem. 2002;74:5383–5392. doi: 10.1021/ac025747h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Launay G., Salza R., Multedo D., Thierry-Mieg N., Ricard-Blum S. MatrixDB, the extracellular matrix interaction database: Updated content, a new navigator and expanded functionalities. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:D321–D327. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Shannon P., Markiel A., Ozier O., Baliga N.S., Wang J.T., Ramage D., Amin N., Schwikowski B., Ideker T. Cytoscape: A software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 2003;13:2498–2504. doi: 10.1101/gr.1239303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The LC–MS/MS raw data were downloaded from the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE repository; dataset identifier PXD017740. Interactive protein schematics showcasing the PLF analysis of these IVD datasets can be viewed (and the comparison datasets downloaded) via the MPLF webtool—https://www.manchesterproteome.manchester.ac.uk/#/MPLF by selecting the “Location Fingerprinter” tab (accessed on 13 September 2021). The DIPPER resource [13] is accessible at: http://www.sbms.hku.hk/dclab/DIPPER/ (accessed on 13 September 2021).