Abstract

Background

Patient‐reported outcomes measures (PROMs) assess a patient’s subjective appraisal of health outcomes from their own perspective. Despite hypothesised benefits that feedback on PROMs can support decision‐making in clinical practice and improve outcomes, there is uncertainty surrounding the effectiveness of PROMs feedback.

Objectives

To assess the effects of PROMs feedback to patients, or healthcare workers, or both on patient‐reported health outcomes and processes of care.

Search methods

We searched MEDLINE, Embase, CENTRAL, two other databases and two clinical trial registries on 5 October 2020. We searched grey literature and consulted experts in the field.

Selection criteria

Two review authors independently screened and selected studies for inclusion. We included randomised trials directly comparing the effects on outcomes and processes of care of PROMs feedback to healthcare professionals and patients, or both with the impact of not providing such information.

Data collection and analysis

Two groups of two authors independently extracted data from the included studies and evaluated study quality. We followed standard methodological procedures expected by Cochrane and EPOC. We used the GRADE approach to assess the certainty of the evidence. We conducted meta‐analyses of the results where possible.

Main results

We identified 116 randomised trials which assessed the effectiveness of PROMs feedback in improving processes or outcomes of care, or both in a broad range of disciplines including psychiatry, primary care, and oncology. Studies were conducted across diverse ambulatory primary and secondary care settings in North America, Europe and Australasia. A total of 49,785 patients were included across all the studies.

The certainty of the evidence varied between very low and moderate. Many of the studies included in the review were at risk of performance and detection bias.

The evidence suggests moderate certainty that PROMs feedback probably improves quality of life (standardised mean difference (SMD) 0.15, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.05 to 0.26; 11 studies; 2687 participants), and leads to an increase in patient‐physician communication (SMD 0.36, 95% CI 0.21 to 0.52; 5 studies; 658 participants), diagnosis and notation (risk ratio (RR) 1.73, 95% CI 1.44 to 2.08; 21 studies; 7223 participants), and disease control (RR 1.25, 95% CI 1.10 to 1.41; 14 studies; 2806 participants). The intervention probably makes little or no difference for general health perceptions (SMD 0.04, 95% CI ‐0.17 to 0.24; 2 studies, 552 participants; low‐certainty evidence), social functioning (SMD 0.02, 95% CI ‐0.06 to 0.09; 15 studies; 2632 participants; moderate‐certainty evidence), and pain (SMD 0.00, 95% CI ‐0.09 to 0.08; 9 studies; 2386 participants; moderate‐certainty evidence). We are uncertain about the effect of PROMs feedback on physical functioning (14 studies; 2788 participants) and mental functioning (34 studies; 7782 participants), as well as fatigue (4 studies; 741 participants), as the certainty of the evidence was very low. We did not find studies reporting on adverse effects defined as distress following or related to PROM completion.

Authors' conclusions

PROM feedback probably produces moderate improvements in communication between healthcare professionals and patients as well as in diagnosis and notation, and disease control, and small improvements to quality of life. Our confidence in the effects is limited by the risk of bias, heterogeneity and small number of trials conducted to assess outcomes of interest. It is unclear whether many of these improvements are clinically meaningful or sustainable in the long term. There is a need for more high‐quality studies in this area, particularly studies which employ cluster designs and utilise techniques to maintain allocation concealment.

Plain language summary

Using patient questionnaires for improving clinical management and outcomes

What is the aim of this review?

The aim of this Cochrane Review was to find out whether healthcare workers who receive information from questionnaires completed by their patients give better health care and whether their patients have better health. We collected and analysed all relevant studies.

Key messages

Patient questionnaire responses fed back to health workers and patients may result in moderate benefits for patient‐provider communication and small benefits for patients' quality of life. Healthcare workers probably make and record more diagnoses and take more notes. The intervention probably makes little or no difference for patient's general perceptions of their health, social functioning, and pain. There appears to be no impact on physical and mental functioning, and fatigue. Our confidence in these results is limited by the quality and number of included studies for each outcome.

What was studied in the review?

When receiving health care, patients are not always asked about how they feel, either about their physical, mental or social health. This can be a problem as knowing how the patient is feeling might help to make decisions about diagnosis and the course of the treatment. One possible solution is to ask the patients to complete questionnaires about their health, and then give that information to the healthcare workers and to patients.

What are the main results of the review?

We found 116 studies (49,785 participants), all of which were from high‐income countries. We found that feeding back patient questionnaire responses to healthcare workers and patients probably slightly improves quality of life and increases communication between patients and their doctors, but probably does not make a lot of difference to social functioning. We are not sure of the impact on physical and mental functioning or fatigue of feeding back patient questionnaire responses as the certainty of this evidence was assessed as very low. The intervention probably increases diagnosis and note‐taking. We did not find studies reporting on adverse effects defined as distress following or related to Patient‐reported outcomes measures (PROM) completion.

How up‐to‐date is this review?

The review authors searched for studies that had been published up to October 2020.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. PROM feedback compared to usual care for improve processes and outcomes of care.

| PROM feedback compared to usual care for improve processes and outcomes of care | ||||||

| Patient or population: ambulatory adult patients. Setting: primary and secondary care settings in North America and Europe. Intervention: PROM feedback reported to physicians or both patients and physicians. Comparison: usual care. | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with usual care | Risk with PROM feedback | |||||

| Quality of life | SMD 0.15

(0.05 to 0.26) favouring PROM feedback vs usual care |

‐ | 2687 (11 randomised trials) | ⊝⊕⊕⊕

Moderate 1 |

PROM feedback probably slightly improves quality of life. Quality of life was assessed using the EuroQoL‐5D (EQ‐5D) KIDSCREEN‐10, Manchester Short Assessment for Quality of Life (MSAQ) , Short Form‐36 (SF‐36), and the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy (FACT) PROMs. Three additional studies also measured overall quality of life; one favoured the intervention and for the other two there was little or no difference between groups. |

|

| General health perceptions | SMD 0.04

(‐0.17 lower to 0.24) indicating little or no difference between PROM feedback and usual care. |

‐ | 552 (2 randomised trials) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low 1, 2 | PROM feedback may make little or no difference to general health perceptions. |

|

| Functioning | Physical functioning | |||||

| SMD ‐0.10 (‐0.30 to 0.10) indicating little or no difference between PROM feedback and usual care. | ‐ | 2788 (14 randomised trials) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low 3, 4 | The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of PROM feedback on physical functioning. Physical functioning was assessed using the physical functioning subscales of the Short Form‐12 (SF‐12), Short form‐36 (SF‐36) Patient‐Physican Communication on HRQOL, European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC‐QLQ‐30) physical functioning, KIDSCREEN‐10, Functional Living Index ‐ Cancer (FLIC) PROMs. |

||

| Mental functioning | ||||||

| SMD 0.16 (0.06 to 0.27) favouring PROM feedback vs usual care | ‐ | 7782 (34 randomised trials) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low 1, 4 | The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of PROM feedback on mental functioning. Mental functioning was assessed using the Outcomes Questionnaire ‐ 45 (OQ‐45), the Outcomes Rating Scale (ORS), General Health Questionnaire (GHQ), Short Form ‐ 12 (SF‐12), Patient‐physician communication on HRQOL, European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC‐QLQ‐30) mental functioning, World Health Organization ‐ 5 (WHO‐5), Beth Isreal‐UCLA Functional Status, Functional Living Index ‐ Cancer (FLIC) PROMs. Six other studies also reported mental functioning, for five studies there was little or no difference between groups and for the sixth study it was not possible to ascertain the direction of the effect. |

||

| Social functioning | ||||||

| SMD 0.02 (‐0.06 to 0.09) indicating little or no difference between PROM feedback and usual care. | ‐ | 2632 (15 randomised trials) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate 1 | PROM feedback probably makes little or no difference to social functioning. Social functioning was assessed using the Community‐Oriented Programs Environment Scale (COPES), the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy (FACT), Work and Social Adjustment Scale (WSAS), Short Form‐12 (SF‐12), Short Form‐36 (SF‐36), KIDSCREEN‐27, Beth Isreal‐UCLA Functional Status, Functional Living Index ‐ Cancer (FLIC) PROMs. One study also reported social functioning, finding little or no difference between groups. |

||

| Symptoms | Pain | |||||

| SMD ‐0.00 (‐0.09 to 0.08) indicating little or no difference between PROM feedback and usual care. | ‐ | 2386 (9 randomised trials) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate 1 | PROM feedback probably makes little or no difference for pain. Pain was assessed using the Short‐Form 36 (SF‐36), European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC‐QLQ‐30) pain module, Symptom Monitor, and the Roland‐Morris Disability Questionnaire |

||

| Fatigue | ||||||

| SMD 0.03 (‐0.29 to 0.36) indicating little or no difference between PROM feedback and usual care. | ‐ | 741 (4 randomised trials) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low 1, 2, 4 | The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of PROM feedback on fatigue. Fatigue was assessed using the Chronic Heart Failure Questionnaire, Symptom Monitor, and the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC‐QLQ‐30) fatigue module. |

||

| Patient‐physician communication | SMD 0.36 (0.21 to 0.52) favouring PROM feedback vs usual care | ‐ | 658 (5 randomised trials) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate 1 | PROM feedback probably increases patient‐physician communication. Communcation was assessed using patient‐physician communication on HRQOL, Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems Clinician and Group Survey (CAHPS) PROM, number of topics discussed. One study not included in the pooled analysis indicated that participants allocated to the intervention rated communication with their physician better than those allocated to usual care. |

|

| Diagnosis and notation | Study population | RR 1.73 (1.44 to 2.08) | 7223 (21 randomised trials) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate 4 | PROM feedback probably increases diagnosis and notation. Diagnosis and notation was assessed using chart review. |

|

| 172 per 1,000 | 347 per 1,000 (278 to 423) | |||||

| Disease control | Study population | RR 1.25 (1.10 to 1.41) | 2806 (14 randomised trials) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate1 | PROM feedback probably leads to an increase in disease control. Disease control was assessed using both PROMs and chart‐based assessments including Partners for Change Outcome Measurement System (PRCOMS), Outcomes Questionnaire ‐ 45 (OQ‐45), Outcomes Rating Scale (ORS), Primary Care Screener for Affective Disorders, Cutting down; Annoyance by criticism, Guilty feeling, and Eye‐openers (CAGE) questionnaire; New York Heart Association class, Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS), Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), and Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM; depression symptoms >= 1). |

|

| 300 per 1,000 | 400 per 1,000 (345 to 458) | |||||

| Adverse effects | ‐‐ | ‐‐ | ‐‐ | ‐‐ | ‐‐ | We did not find studies reporting on adverse effects. |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; OR: Odds ratio;SMD: Standardised mean difference. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

1 We downgraded one point for risk of unblinding due to the nature of the intervention in the majority of studies.

2 We downgraded one point for imprecision due to the small number of studies with wide confidence intervals included in meta‐analysis.

3 We downgraded one point for high risk of bias in multiple studies.

4 We downgraded one point for inconsistency due to statistical heterogeneity.

Background

Description of the condition

Definition of patient‐reported outcome measures

Patient‐reported outcomes measures (PROMs) assess patients' subjective appraisal of outcomes from their own perspective (Valderas 2008b). PROMs feedback offer complementary information to the objective measurements usually collected (Porter 2016).

Historically, the use of PROM information has been far less common in clinical practice than in research, where PROMs are often selected as outcome measures in clinical trials (FDA 2009;Fitzpatrick 1998; Nelson 2015; Valderas 2008c). At an individual level and within the clinician‐patient interface, PROMs have been used for screening and monitoring a condition, such as depression symptoms; for monitoring the progress of the patient during the course of treatment or throughout time; and for promoting patient‐centred care, by explicitly assessing the patient’s perspective (Basch 2016; Greenhalgh 2009).

Description of the intervention

Patient reported outcomes (PRO) have been defined as assessments of any aspect of a patient’s health status which are provided directly by the patient (FDA 2009; Valderas 2008b), usually through a questionnaire scale referred to as PROMs. Patient‐reported outcome is an umbrella term: it can be applied to an array of different outcomes, including symptoms, functioning, perceived health status and health‐related quality of life (Black 2013; McKenna 2011).

PROMs that measure aspects of health which are relevant to all people are referred to as generic. One such example is the Short Form 36, which assesses, alongside specific symptoms, physical functioning and psychological well‐being, as well as evaluating overall self‐reported health (Garratt 1993; Valderas 2008d). In theory, such generic measures can be used within and between populations, regardless of age, gender, and disease or condition. Concerns regarding the suitability of generic PROMs for patients and groups with specific conditions has led to the development of PROMs with a narrower focus on a single group of patients. (Garratt 2002). So called disease‐specific PROMs are widely available for common conditions such as diabetes (Bradley 1999), to less frequent ones, including amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (Gibbons 2011), and haemophilia (Arranz 2004).

When used in clinical practice at the level of the individual patient level, PROM feedback forms part of a complex intervention which can include a number of different components (Craig 2008). The fundamental components of a PROM intervention is that: a) patients complete one of more questionnaires and b) the results are fed back to the clinician, the patient, or both. The International Society for Quality of Life Research has defined a set of eight considerations which ought to be followed when implementing PROMs in clinical practice; establishing the goals;identifying patients and settings; selecting questionnaires; defining the administration and scoring procedures; reporting results; facilitating score interpretation; establishing protocols to address issues raised by the questionnaires; and assessing the eventual impact of the questionnaire in clinical practice (Snyder 2012).

While evidence can be found that these steps have been followed in many PROM feedback interventions, considerable variation is also apparent. For instance, instruments can be self‐completed (Rand 1988) or interviewer‐administered (German 1987); completed in the clinical setting (Christensen 2005) or posted to the patient’s home (Lewis 1996); and supported by an electronic format such as online or tablet administration (Basch 2016; Velikova 2004) or rely on pencil and paper (Trowbridge 1997). As for the feedback, discrepancies might exist between trials as to when the information is given to healthcare professionals, e.g. immediately before the visit (Berry 2011); and how it is given, e.g. printed form (Saitz 2003); and by whom, e.g. available in the notes (Linn 1980). More importantly, considerable differences occur regarding the amount of feedback provided. For example, in some studies the only information fed back to healthcare professionals were the scores each patient obtained in the PROM (Bergus 2005), whereas in other studies professionals were given information on how to apply interpretation guidelines for the scores (Rosenbloom 2007), or treatment guidelines for the conditions detected by the PROM (Saitz 2003). The number of times the patient completes the PROM can also vary considerably, from single responses (Hoeper 1984) to feedback at multiple points (Cleeland 2011; Klinkhammer‐Schalke 2012). Reflecting this, there is also variation in whether the clinician receives the PROM scores immediately or at given intervals (e.g. daily, weekly). Finally, the endpoints used to assess the impact of PROM feedback in clinical practice have also been a source of considerable variation, with trials inconsistently reporting on processes of healthcare (e.g. patient‐clinician communication), outcomes of healthcare (e.g. changes in the number or rate of symptoms or complaints), and patient experience (e.g. overall satisfaction with care).

How the intervention might work

The Feedback Intervention Theory (FIT) posits that behaviour is regulated through comparison with standards or goals, and that feedback can draw attention to existing gaps between current and ideal states (Kluger 1996). In the context of PROM feedback interventions, PROM scores are being presented to either patients or clinicians to highlight specific issues and, in some cases, are presented alongside information designed to help to address the highlighted issues (Greenhalgh 2017). For example, If a patient scores above the established cut‐off point in a depression screening PROM, then the healthcare professional will be made aware of this discrepancy between the desired state of psychological well‐being and the current distress experienced by the patient. In this case, the PROM feedback and the desired outcome may be measured by the same PROM. Other interventions may utilise PROM feedback to improve other outcomes, such as an intervention to feedback information relating to symptoms of cancer and its treatments with the goal of reducing emergency room visits. Whether the same PROMs are used to provide feedback and measure outcomes or not, FIT further postulates that once the gap has been identified, different methods can be followed in order to decrease this gap and attain the standard, including increasing the effort currently being made(Kluger 1996).

Feedback to patients and clinicians could be expected to modify a number of behaviours (Greenhalgh 2017; Greenhalgh 2018; Porter 2016). Feedback to clinicians could be substantiated by the professional using several strategies, including providing advice, referring to other services, or altering the patient's medication plan. All of these are processes of care that would, potentially, trigger improvements in outcomes, such as improved functioning and increased health‐related quality of life. Feedback given directly to patients could result in additional care being sought or implementing self‐management solutions relating to the PROM scores. However, whether these outcomes do materialise depends on a range of other contextual factors including the patient or clinician's willingness or ability to act on the provided feedback as well the patient’s acceptance of, and adherence to, any treatment changes and the effectiveness of that treatment.

Why it is important to do this review

In the UK, PROMs are one of the cornerstones of National Health Service reform for the transition towards a patient outcomes‐oriented performance model (Black 2016; Calvert 2019; Valderas 2012). In the USA, initiatives such as the Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (Alonso 2013; PROMIS 2007), funded by the National Institutes of Health, or the inclusion of PROMs in electronic health record software, such as EpicCare (EpicCare 2015) held by Group Health Cooperative, highlight the progressive relevance these outcome measures play in healthcare contexts. The US Department of Health and Human Services also plans to incorporate PROMs into meaningful use standards, which is likely to prompt more widespread use (Hostetter 2011).

The level of evidence for the impact of assessing outcome using PROM feedback in clinical practice has been mixed (Espallargues 2000; Gilbody 2001; Greenhalgh 1999; Marshall 2006; Valderas 2008a). Valderas 2008a found that there was more evidence for impact upon the processes rather than the outcomes of care. Specifically, there was an increase for the rate of diagnoses and chart notations for the conditions targeted by the interventions (e.g. diagnosis of depression in primary care). Similarly, there was also a positive effect on the advice and education provided by the healthcare professionals. Furthermore, Valderas 2008a identified a total of 36 endpoints for the 28 randomised trials included in their systematic review, which seems to reiterate the lack of consensus amongst researchers of how the intervention should work and thus what constitutes a relevant indicator when using PROMs in clinical practice.

Notwithstanding the potential benefits for clinical practice, several objections have been raised in relation to their routine use. Healthcare professionals have expressed doubts about the clinical utility of PROM feedback, as they consider that little value is added to their clinical judgement (Leydon 2011; Taylor 1996). Healthcare professionals have also described how burdensome the use of PROMs can be, as it requires time to administer the measures and time to learn how to analyse and interpret the results (Brown 2006) and also to integrate them into clinical practice in an efficient and non‐disruptive manner (Nelson 1990). Clinicians have voiced concerns that the PROMs might represent a threat to the holistic nature of the patient‐doctor relationship (Leydon 2011). It has also been suggested that PROMs increase the healthcare professional’s responsibility and burden of care, as they might detect problems that could otherwise go unnoticed (Tavabie 2009). Finally, the use of PROMs has been increasingly advocated for guiding the provision of care for people with multiple chronic conditionsValderas 2009; Smith 2021; Valderas 2019.

Taking both the potential benefits and risks and the current health policy initiatives into account, it becomes essential to ascertain to what extent the use of PROMs in clinical practice does actually improve processes and outcomes of care. Previous reviews have provided mixed evidence and a number of relevant studies have been subsequently published (Valderas 2010).

Objectives

To assess the effects of Patient‐reported outcomes measures (PROMs) feedback to patients, healthcare workers, or both on patient‐reported health outcomes and processes of care.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised trials and cluster‐randomised trials, where individuals (healthcare professionals or patients) or groups of individuals (including whole hospitals or practices) were randomly allocated to either a control or an intervention group. We did not include studies that follow a non‐randomised design, such as before‐after studies and interrupted time series. The protocol of this review is available on the Cochrane LibraryGonçalves‐Bradley 2015.

Types of participants

We only included studies where participants have been recruited in primary (e.g. health practitioner’s office) or secondary/tertiary (e.g. hospital) care settings in order to ensure that interventions were delivered as part of clinical care. We excluded studies conducted outside primary and secondary/tertiary healthcare settings (e.g. assisted living facilities) in order to ensure that PROM feedback was used for clinical purposes only. There were no age or gender restrictions, nor restrictions based on the presence or absence of any specific disease.

Types of interventions

We only included studies if they reported a replicable intervention, where standardised or individualised PROMs were administered to patients and the resulting information on each individual patient was subsequently fed back to healthcare providers or patients, or both. Patient‐reported outcome measures were defined as the assessment of any aspect of a patient’s health status which is provided directly by the patient (FDA 2009), usually through a questionnaire or scale. PROMs could be used for a number of different outcomes, including measurements of health status, quality of life, symptoms and functioning (McKenna 2011). A replicable intervention was defined as one where details of the content and timing of the assessment and feedback provision were clearly described. We included studies regardless of whether feedback was provided to patients only or to healthcare providers only, or to both. We included studies irrespective of whether the results were fed back along with guidelines regarding their optimal use, or other educational strategies. We included studies if they were conducted either during a specific procedure, for instance a surgical procedure; or during routine care, for example a primary‐care appointment. The comparison (control) condition consisted of routine clinical practice without the feedback of any information to the healthcare professionals.

When multiple control arms were included, we selected as control the arm that most closely reproduced standard care. For intervention arms, we selected the arm that included the least additional components (other than PROMs were fed‐back)Cochrane Handbook 5.1.0, Section 16.5.4.

Types of outcome measures

Our primary outcomes included generic or disease‐specific patient‐reported outcomes such as health‐related quality of life and functioning. Secondary outcome measures were considered to assess processes of care.

The intervention is hypothesised to increase the awareness of those receiving feedback of health problems as perceived and reported by patients. Since the additionally available information on health problems that is fed back is patient‐reported, the main benefit of the intervention can be anticipated to be on health status as appraised by patient themselves (Greenhalgh 2017; Greenhalgh 2018; Porter 2016; Porter 2021). In addition, increased awareness of existing health problems can also have the negative effect of creating anxiety and distress on patients (Porter 2016; Valderas 2012).

Awareness of a health problem can potentially impact on a cascade of effects on processes of health care involving the appraisal of the severity of problem and consideration of whether it meets diagnostic criteria for a specific condition, proposing, implementing and monitoring a management. In the case of the patient as a recipient of the information, increased awareness may also trigger self‐management activities, activation and concordance with the agreed management plan (Greenhalgh 2017; Greenhalgh 2018;Porter 2016; Porter 2021).

Primary outcomes

Our primary outcomes were:

patient‐reported outcomes: quality of life, general health perceptions, functioning, and symptoms, such as nausea, fatigue, and mental health‐related symptoms;

adverse effects: distress following or related to PROM completion.

Secondary outcomes

For the processes of health care, we considered the following endpoints:

patient‐physician communication (e.g. patients' ratings of the quality of the communication);

diagnosis and recognition (e.g. number of target diagnoses made);

treatment (e.g. changes to treatment);

health services and resource use (e.g. referral to specialist or social care);

patient behaviour (e.g. compliance with treatment);

patient empowerment (e.g. measured using available self‐reported instruments); and

healthcare professionals’ awareness of patients' quality of life.

Other outcomes included: patients' experiences (e.g. overall satisfaction with care) and healthcare professionals' perceptions (e.g. attitude and overall satisfaction with intervention); consultation length; healthcare costs.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR; to 2018, Issue 9) and the Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE; to 2015, Issue 2) for primary studies in related systematic reviews. We searched the following databases on 5 October 2020:

MEDLINE Ovid (including in‐process and other non‐indexed citations; 1946 onwards)

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2020, Issue 10) in the Cochrane Library

Embase Ovid (1974 onwards)

PsycINFO Ovid (1806 onwards)

CINAHL EBSCO (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature; 1980 onwards)

The EPOC Cochrane Information Specialist (CIS) developed the search strategies in consultation with the authors. Search strategies are comprised of natural language and controlled vocabulary terms. We applied no language or date limits. All search strategies used are provided in Appendix 1.

Searching other resources

Trial Registries

We searched the following trials registries on 5 October 2020:

International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP), Word Health Organization (WHO) www.who.int/ictrp/en/;

ClinicalTrials.gov, US National Institutes of Health (NIH) clinicaltrials.gov/.

We also conducted the following measures:

screened previously published reviews for potentially‐relevant references;

contacted authors of the included studies to request information about ongoing studies.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors independently assessed each reference in title and abstract form to ascertain whether they met the eligibility criteria. We piloted the eligibility criteria against a random sample of approximately 1% of all the documents received, after which two review authors independently screened all the references. Because we were aiming for maximum sensitivity at this stage, we included all references assessed as relevant by at least one team member, and only excluded references unanimously assessed as irrelevant.

We followed the same strategy for the full‐text documents selected for inclusion in the review. We conducted a sensitivity strategy with a random sample of approximately 1% of the records. As at this stage in order for maximum specificity to be achieved, we discussed disagreements between team members until consensus was reached, and we only include references rated as relevant by all the review authors. We involved a third review author where consensus was not achieved. Whenever pertinent and possible, we contacted authors for the documents that received a discrepant rating, in order to clarify any queries. We documented the selection process using a PRISMA flow diagram and described all the studies that fulfil the inclusion criteria in the Characteristics of included studies table.

Data extraction and management

We independently saved all the retrieved results to a bibliographic database using reference management software (Reuters 2011). We saved all the results and removed any duplicates. Two review authors independently extracted data from the studies assessed as relevant during the stage of study, and we resolved any disagreements through discussion. We designed the data extraction form according to aspects considered to be relevant for the present systematic review, including those suggested by the Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Group (EPOC 2014), and covered the following domains.

a) Study features: clinical setting (type of setting, academic status, and country); method of randomisation (including allocation concealment and blinding); unit of randomisation and analysis (patient/healthcare professional or practice/hospital); number of arms.

b) Participants' features: inclusion and exclusion criteria; patients' characteristics (socio‐demographic information using the PROGRESS framework; health condition; and whether new or known to the healthcare professional); healthcare professionals' characteristics (profession; level of training; and previous experiences with PROM feedback).

c) Intervention features: design, which were either: single simple feedback (one PROM at a single time); multiple simple feedback (one PROM at multiple times); single complex feedback (multiple PROMs at a single time); multiple complex feedback (multiple PROMs at multiple times); and how PROMs were used (which may be for the intervention or for assessing outcomes, or both); constructs measured; PROM categories/domains.

d) Administration features: method for data collection (self‐reported; interviewer; other); support used (pencil and paper; computer‐assisted; other); setting of data collection (home; clinical; other); facilitator (no facilitator; clinical facilitator; research facilitator; other); other relevant administration‐related characteristics.

e) Feedback: timing (associated with visits or not; scores given before appointments, during or other); amount of information provided (last score; previous scores; application of interpretation guidelines; application of treatment guidelines; other); support used (printed form; computer‐assisted; other); method for feeding back the information (handed by patients; handed by research staff; available in notes; other).

f) Description of the intervention: narrative description as provided by authors.

g) Results: results as provided by authors, both for processes and outcomes of care.

h) Other features: study identifier; source of funding; ethical approval; sample size calculation; prospectively‐identified barriers to change; methodological quality.

Complex health interventions pose specific challenges to assessment (Craig 2008); and data synthesis (Shepperd 2009). Specific recommendations on how to overcome these limitations have now been suggested, including identifying key components of the interventions and categorising them according to those components (Shepperd 2009). Hence, when extracting data we also categorised the identified interventions according to their main components.

Given the heterogeneity of outcomes in this review, we handled the outcome results in a two‐stage approach. In the first stage, we carried out the following measures.

1) Collated data according to the headings outlined in the Types of outcome measures section.

2) Extracted the appropriate data for each arm according to the principle of intention‐to‐treat (i.e. according to the original random allocation). For dichotomous data: number of patients experiencing outcome/total patient number. For continuous data: total patient number, outcome mean and standard deviation (SD). We sought continuous data reported as mean and SD for change in outcome from baseline (adjusted for baseline score); and, where not available, mean absolute outcome and SD at follow‐up was recorded. For other outcome types (e.g. event rate, time to event) we extracted data appropriately.

3) Extracted outcome data for all follow‐up points.

4) Extracted outcome data by subgroups according to the characteristics of the intervention (straight feedback of the results to the healthcare professional; or feedback along with guidelines regarding how to interpret results or other educational strategies); and patient characteristics (educational level). When required and feasible, data were transformed in order to standardise outcomes, for instance for differences in the direction of the scales.

We piloted the data extraction form with a small sample of articles. The sample was purposively selected to ensure heterogeneity in terms of type of studies and interventions. All researchers who participated in the data extraction took part in this pilot. Extracted data were stored in an electronic database, which was created using RevMan 5 (RevMan 2012).

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We assessed risk of bias based on criteria suggested by Cochrane (Higgins 2011) and additional criteria proposed by EPOC (EPOC 2017c), assessing the following nine domains: random sequence generation; allocation concealment; participants' blinding (either patients or healthcare providers); blinding of outcome assessment; similarity of baseline measurement, both for outcome measures and participants’ characteristics; incomplete outcome data; protection against contamination; selective reporting; and other sources of bias, including whether the used PROMs have been previously validated for the specific setting and population. We classified each parameter as high risk of bias, low risk of bias, or unclear, and obtained information was summarised in tabulated form, using RevMan 5 (RevMan 2012). As a guide, we judged a study as at high risk of bias if more than three of the nine individual items were considered to be high risk. We expressed level of confidence in the evidence for each outcome using the GRADE criteria, by assessing the type of evidence, limitations in study design, indirectness of evidence, unexplained heterogeneity of findings, imprecision of results, and probability of publication bias in accordance with the guidance of Higgins 2011. We assessed publication bias by inspecting funnel plots for all analyses.

Measures of treatment effect

We calculated risk ratios with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for dichotomous data. Where studies used continuous scales of measurement to assess the effects of the intervention, we used mean differences (MD) with 95% CIs; or, when studies used different scales or measurements, we used the standardised mean difference (SMD). Where studies used other outcome metrics, e.g. rates of events or time to event, we sought the appropriate overall measure of effect, e.g. rate RR, hazard ratio (HR). We used established guidelines to aid interpretation of effect sizes (Cohen 1988), and considered estimates <0.35 to represents a small effect, 0.35 to 0.65 a moderate effect, and d>0.65 a large effect. Similarly, we considered RR estimates to correspond to small (0.66>RR>1.5), moderate (between 033>RR>0.66 or 1.5>RR>3), and large effects (either RR<0.33 or RR>3).

Unit of analysis issues

Where included studies included a cluster design, we contacted the trial authors to obtain an estimate of the intra‐cluster correlation (ICC) where appropriate adjustments for the correlation between participants within clusters had not been made, or imputed it using estimates from the other included trials, or from similar external trials. Where necessary, we inflated the trial standard errors (SEs). We attempted to either reduce the size of trials to its ‘effective sample size’ or recalculate the effects using an approximately correct analysis and using design effect calculated from the ICC (Higgins 2011). Whenever studies included more than one intervention arm, we combined arms to create a single pair‐wise comparison or conducted pair‐wise comparisons by comparing each intervention arm to the control arm (splitting the control arm sample size).

Dealing with missing data

We attempted to obtain any missing information which was necessary to conduct our analyses by contacting the authors of the trials. Missing information included outcome data including estimates of distribution and number of patients included in each analysis.

For dichotomous outcomes, we carried out analyses according to the intention‐to‐treat (ITT) method (Higgins 2011), which includes all participants irrespective of compliance or follow‐up. For the primary analyses, we assumed that participants lost to follow‐up were alive, and had no serious adverse events. For continuous outcomes, we performed available patient analysis and included data only on those for whom results were known (Higgins 2011). Wherever it had not been possible to obtain SDs either from authors or by calculation, we planned for the missing data to be imputed by using SDs from other included trials, specifically trials with a low risk of bias (Furukawa 2006). However, heterogeneity in populations and measures prevented us from doing so in all the relevant cases.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We explored clinical heterogeneity across studies by comparing the population, intervention and control arms. We explored statistical heterogeneity observed in the trials both by visual inspection of a forest plot, and by using a standard Chi² value with a significance level of P = 0.10. We assessed heterogeneity using the I² statistic. An I² estimate greater than 50% was interpreted as evidence of a substantial problem with heterogeneity (Higgins 2011). Where this was the case, we explored reasons for heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

We did not assess reporting biases through visual inspection of funnel plots.

Data synthesis

We performed data synthesis according to recommendations in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011), using RevMan 5 (RevMan 2012) and STATA v13 (StataCorp 2013). Given the likely heterogeneity of data in this review, we handled the outcome results in a two‐stage approach. In the first stage, we: (1) collated data according to the headings outlined in the Types of outcome measures section; (2) according to outcome, extracted the appropriate data for each arm according to the principle of ITT (i.e. according to the original random allocation): for dichotomous data: number of patients experiencing outcome/total patient number; for continuous data: total patient number, outcome mean and SD. We sought continuous data reported as mean and SD for change in outcome from baseline (adjusted for baseline score) and where not available, we recorded mean absolute outcome and SD at follow‐up. For other outcome types (e.g. event rate, time to event) we extracted data appropriately; (3) we extracted outcome data at all follow‐up points; (4) where reported, we also extracted this outcome data by subgroups according to the characteristics of the intervention (straight feedback of the results to the healthcare professional; feedback along with guidelines regarding how to interpret results or other educational strategies) and patient characteristics (educational level).

In the second stage, based on the quality and consistency of outcome reporting, we decided to synthesise results across studies using either a formal quantitative meta‐analytic approach or a more descriptive approach that focused on summarising the size and direction of treatment effect separately for each individual study. Where sufficient information was provided by the studies included in the review, the potential impact of moderator variables was considered through meta‐regression analysis. When required and feasible, we transformed data in order to homogenise outcomes, for instance for differences in the direction of the scales. We assessed heterogeneity using the I² statistic (Higgins 2003). Due to the expected heterogeneity of the data, we employed random‐effects methods (Deeks 2008). Further specification of the methods for analysis, e.g. MD versus SMD, was tailored to the type of outcome data. When the heterogeneity of studies was found to be substantial, i.e. I² above 50%, we performed a meta‐analysis to quantify the results by calculating effect sizes (EPOC 2014b).

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We did not hypothesise interactions or effect modifiers in this review, and therefore we did not pre‐specify stratified meta‐analysis or meta‐regression analyses (except for risk of bias — see Sensitivity analysis below). However, where conducted, we extracted data and reported trial‐level subgroup analyses to inform hypothetical models of subgroup analysis for future meta‐analyses.

Sensitivity analysis

We conducted a sensitivity analysis by verifying the impact that the exclusion of certain studies (e.g. those with high overall risk of bias (see definition above), and those with large samples) has on the overall results. We defined a large sample as having more than twice the number of patients than the second largest study in that analysis. Whenever relevant and possible we attempted to contact study authors in order to obtain missing information. Where authors failed to provide missing information, existing data were analysed and the hypothetical impact of the missing data examined as a sensitivity analysis. Finally, we undertook a sensitivity analysis to examine the impact varying the ICC for reanalysis of cluster‐randomised trials.

Summary of findings and assessment of the certainty of the evidence

Four review authors (CSG, IP, ET, JMV) worked in two groups to assess the certainty of the evidence (high, moderate, low, and very low) using the five GRADE considerations: risk of bias, inconsistency, imprecision, indirectness, and publication bias (Guyatt 2008). We used methods and recommendations described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Schünemann 2019) and the EPOC worksheets (EPOC 2017), using GRADEpro software (GRADEpro GDT). We resolved disagreements on certainty ratings by discussion and provided justification for decisions to down‐ or upgrade the ratings using footnotes in the table, making comments to aid readers' understanding of the review where necessary. We used plain language statements to report these findings in the review (EPOC 2017b).

We created a summary of findings table with the following outcomes in order to draw conclusions about the certainty of the evidence within the text of the review: quality of life, general health perceptions, functioning (physical, mental, and social), symptoms (pain and fatigue), patient‐physician communication, diagnosis and notation, and adverse effects.

We considered whether there was any additional outcome information that we were not able to incorporate into meta‐analyses, noted this in the footnotes and stated if it supports or contradicts the information from the meta‐analyses. When it was not possible to meta‐analyse the data, we summarised the results in the text and in the comments section of the summary of findings tables.

Results

Description of studies

See Characteristics of included studies for more information.

Results of the search

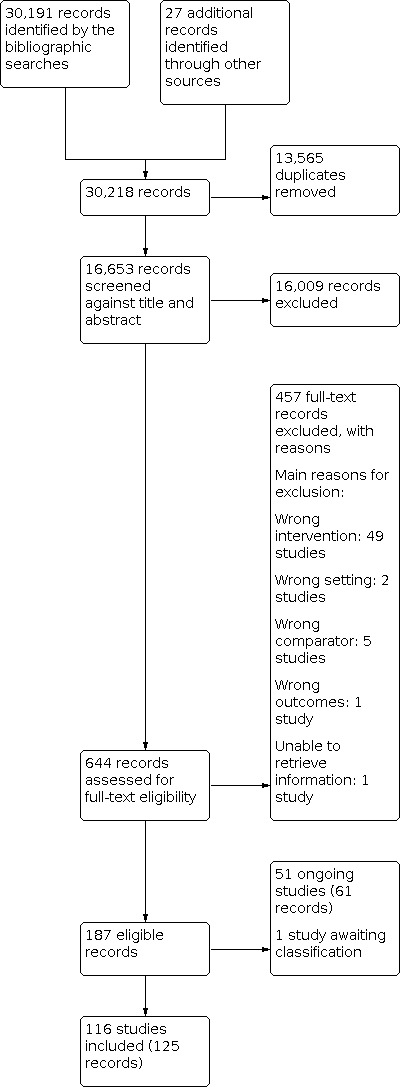

The electronic searches yielded 30,191 references for screening, with an additional 27 references identified from other sources. After we removed duplicates, we screened 16,653 records against title and abstract. Of these, we excluded directly or indirectly 16,009 records following title and abstract screening (Figure 1). We retrieved full texts for 644 records which two independent reviewers assessed for eligibility. We excluded further 457 records (see Characteristics of excluded studies). We included 116 studies in this review, from 125 records. We identified 51 ongoing studies (see Characteristics of ongoing studies), and there is one study awaiting classification (see Characteristics of studies awaiting classification).

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

One hundred and sixteen studies met our inclusion criteria. The individual studies are described in detail in the Characteristics of included studies table.

Population/Participants

There was a total of 49,785 participants randomised across all the included studies. The number of patients randomised ranged from 30 (Blonigen 2015) to 2284 (Stuck 2015). There was a wide variation in the time to follow‐up between one month and two years. Studies were conducted across a broad range of settings including primary and secondary care clinics in North America and Europe.

Mean age varied between 22 (Lambert 2001) and 80 years (Hadjistavropoulos 2009). Seventy‐three studies recruited a higher percentage of women compared to men, including one study (Wheelock 2015) which recruited 100% women (breast cancer study). Twenty‐seven studies recruited more men than women, including two which had 100% male recruitment, one was a prostate cancer study (Davis 2013), the other too few women were recruited so were excluded from the sample altogether (Magruder‐Habib 1990). Three studies recruited an equal proportion of females and males (Anker 2009; Rand 1988van der Hout 2020). A minority of studies did not report exact or accurate figures for gender, e.g. ‘about two thirds female’ (German 1987) including six which did not report clearly enough to indicate whether more men or women were recruited.

Description of the interventions

Included studies were conducted in high‐income countries including the USA, Canada, Ireland, Spain, the UK, France, the Netherlands, Norway, Denmark, Sweden, Switzerland, Italy, Australia and New Zealand.

All interventions were designed to elicit information from patients using a standardised patient‐reported outcome measure (PROM )and fed that information back to either patients, clinicians, or both. Different types of PROMs as well as administration methods and timings were used. Studies either assessed PROM feedback once at a single visit, multiple times prior to or during scheduled ambulatory visits, or by assessing patients in the community at pre‐specified intervals. 27 studies utilised single simple feedback (one PROM at a single time); 37 studies utilised multiple simple feedback (one PROM at multiple times); 7 studies utilised single complex feedback (multiple PROMs at a single time); 45 studies utilised multiple complex feedback (multiple PROMs at multiple times). The majority of studies (84 studies) utilised a domain or disease‐specific PROM, 24 studies used both and generic and disease‐specific tool, and the remaining 8 studies reported the use of a generic PROM alone.

In total, 58 of the included studies used paper‐based PROMs, 47 studies used electronic administration methods, while 3 studies used a combination of both. The assessment method was unclear in the remaining 8 studies.

Information was most frequently fed‐back to clinicians alone (74 studies). Some studies reported feeding this information back to both patients and clinicians (35 studies). Only three studies fed the information back to patients alone (Gossec 2018; LeBlanc 2019; van der Hout 2020). In the Gossec 2018 study it was at patients’ discretion how many times they recorded information and received feedback, and in turn could share the feedback with clinicians at their instigation, while the LeBlanc 2019 and van der Hout 2020 studies both recommended professional health‐care options based upon symptoms.

Funding sources

Most studies were funded by governmental or academic grants. Some studies were partially or fully funded by pharmaceutical companies (Gilliam 2004; Lugtenberg 2020; Mathias 1994; Mazonson 1996; Moore 2019; Myasoedova 2019; Schriger 2001; Schriger 2005; van Os 2003), a health‐insurance fund (Scheidt 2012), a home‐assistance company (Mathias 1994), a contract research organisation (Gossec 2018), and a digital platform for early detection of disease (Denis 2017). Seventeen studies did not report funding sources.

Excluded studies

We excluded 58 studies (456 reports and present in the Characteristics of excluded studies the 58 studies for which we could not reach immediate consensus, or that readers might expect to see included in the review. The main reason for exclusion was wrong intervention, as PROMs feedback was not part of the intervention (49 studies).

Risk of bias in included studies

For a summary assessment of the risk of bias of the included studies see Figure 2 and Figure 3. Most studies were at high risk of bias for blinding of patients and personnel (performance bias) and blinding of outcomes assessment (detection bias). We did not find any evidence of publication bias in the funnel plots of the studies included in the meta‐analyses except for studies evaluating the impact of the intervention in dyspnoea, anxiety, and disease control, for which there seemed to be a fewer studies than expected with small sample sizes and negative results.

2.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

3.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Allocation

We assessed sequence generation as high risk of bias in 10 studies (Absolom 2021; Anker 2009; Berking 2006; Christensen 2005; Dowrick 1995b; German 1987; McCusker 2001; Scheidt 2012; Subramanian 2004; Zung 1983).

Thirty‐one studies had a high risk of allocation disclosure (Amble 2014; Berking 2006; Calkins 1994; Callahan 1994; Callahan 1996; Cherkin 2018; Detmar 2002; Goldsmith 1989; Gutteling 2008; Hadjistavropoulos 2009; Hoekstra 2006; Kendrick 2017; Mathias 1994; Mazonson 1996; Murillo 2017; Priebe 2007; Puschner 2009; Rand 1988; Rubenstein 1995; Ruland 2003; Saitz 2003; Scheidt 2012; Slade 2006b; Strasser 2016; Subramanian 2004; Trudeau 2001; Wasson 1992; White 1995; Whooley 2000; Wikberg 2017; Wolfe 2014).

Blinding

Due to the nature of the interventions in this review, which all included the routine administration and feedback of PROMs in clinical practice, it was not feasible to blind participants and personnel, hence we necessarily assessed this criterion as high risk in most studies. We did not have enough information to make a decision for Atreja 2018; Cooley 2016; Haas 2016. Similarly, we deemed the blinding of outcomes assessment as high risk in most studies, as due to the nature of the interventions blinding of outcomes was not possible, PROMS used for feedback were also used to assess outcome. For 17 studies (Absolom 2021; Atreja 2018; Bastiaansen 2018; Bryant 2020; Cooley 2016; Dueck 2015; Franco 2020; Haas 2016; Kuo 2020; LeBlanc 2019; Lugtenberg 2020; Moore 2019; Myasoedova 2019; Richardson 2019; Tolstrup 2020; Valles 2017; van der Hout 2020), there was not enough information to make a decision and we assessed those studies to have an unclear risk of detection bias. We assessed one study to be at low risk of detection bias as the main outcome was objective and directly collected from the health records (Sandheimer 2020).

Baseline characteristics and outcome measurements

We assessed differences in baseline characteristics between intervention and control groups as high risk in nine studies (Amble 2014; Hadjistavropoulos 2009; McCusker 2001; Puschner 2009; Simon 2012; Strasser 2016; Thomas 2016; Valles 2017; Wagner 1997).

Ten studies had a risk of bias for differences in baseline outcome measurements between intervention and control groups (Anderson 2015; Blonigen 2015; De Jong 2014; Denis 2017; Kendrick 2017; Nimako 2017; Puschner 2009; Trudeau 2001; Valles 2017; Zung 1983).

Incomplete outcome data

Inadequate strategies for addressing incomplete data leading to high risk of bias were evident in 26 studies (Anderson 2015; Anker 2009; Callahan 1994; Callahan 1996; De Jong 2012; De Jong 2014; Dowrick 1995a; Gossec 2018; Haas 2016; Hadjistavropoulos 2009; Hawkins 2004; Kazis 1990; Kendrick 2017; Lugtenberg 2020; Magruder‐Habib 1990; Moore 1978; Murphy 2012; Rubenstein 1995; Saitz 2003; Scheidt 2012; Schottke 2019; Simon 2012; Strasser 2016; Thomas 2016; Whipple 2003; Wikberg 2017).

Protected against contamination

Thirty‐four studies were at high risk of contamination (Absolom 2021; Amble 2014; Anker 2009; Bastiaansen 2018; Bryant 2020; Christensen 2005; Cleeland 2011; Detmar 2002; Dowrick 1995a; Dowrick 1995b; Franco 2020; Hoeper 1984; Kazis 1990; Lambert 2001; Linn 1980; Lugtenberg 2020; Magruder‐Habib 1990; McLachlan 2001; Nimako 2017; Nipp 2019; Pouwer 2001; Richardson 2019; Rubenstein 1995; Saitz 2003; Sandheimer 2020; Simons 2015; Slade 2006b; Stuck 2015; Thomas 2016; Tolstrup 2020; Wagner 1997; Whipple 2003; Wikberg 2017; Zung 1983).

Selective reporting

Six studies were at high risk for selective outcome reporting (Hoeper 1984; LeBlanc 2019; Lugtenberg 2020; Mazonson 1996; Reese 2009; Yager 1981).

Other potential sources of bias

We did not assess other potential sources of bias.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Our comprehensive search of the literature identified 116 randomised studies which evaluated the impact of patient‐reported outcome assessment and feedback on either processes or patient‐reported outcomes of care. We conducted 37 analyses in 15 categories of Quality of Life, Health Perceptions, Functioning, Symptoms, Communication, Clinician‐rated severity, diagnosis and notation, Pharmacological treatment, Counselling, Referrals, Visits and sessions, Hospital admissions and length of stay, Disease control, Patient perceptions, Quality of care, and Costs. For specific details on the certainty of the evidence, refer to Table 1 and Table 2.

1. PROM feedback compared to usual care for improve processes and outcomes of care.

| PROM feedback compared to usual care for improve processes and outcomes of care: additional analyses not included in Summary of Findings. | ||||||

| Patient or population: Ambulatory adult patients. Setting: Primary and secondary care settings in North America and Europe. Intervention: PROM feedback reported to physicians or both patients and physicians. Comparison: Usual care. | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with usual care | Risk with PROM feedback | |||||

| Symptoms | Dyspnoea | |||||

| SMD ‐0.11 (‐0.32 to 0.11) indicating no difference between PROM feedback and usual care | ‐ | 765 (5 randomised trials) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low 1, 2, 3 | We are uncertain about the effect of PROM feedback on dyspnoea. | ||

| Nausea | ||||||

| SMD ‐0.08 (‐0.76 to 0.59) indicating no difference between PROM feedback and usual care | ‐ | 239 (2 randomised trials) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low 1, 2, 3 | We are very uncertain about the effect of PROM feedback on nausea. | ||

| Cough | ||||||

| SMD ‐0.14 (‐0.75 to 0.48) indicating no difference between PROM feedback and usual care | ‐ | 122 (2 randomised trials) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low 1, 2, 3 | The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of PROM feedback on cough. | ||

| Depressive symptoms | ||||||

| SMD ‐0.12 (‐0.19 to ‐0.05) indicating no difference between PROM feedback and usual care | ‐ | 3449 (16 randomised trials) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate 1 | PROM feedback probably results in a slight reduction in depressive symptoms. | ||

| Anxiety symptoms | ||||||

| SMD ‐0.17 (‐0.31 to ‐0.03) indicating no difference between PROM feedback and usual care | ‐ | 2334 (8 randomised trials) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low 1, 4 | We are very uncertain about the effect of PROM feedback on anxiety. | ||

| Clinician severity ratings | SMD 0.36 (0.12 to 0.6) favouring PROM feedback vs usual care. | ‐ | 312 (3 randomised trials) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low 1, 4 | We are very uncertain about the effect of PROM feedback on clinician severity ratings. | |

| Pharmacological treatment | Study population | RR 1.21 (0.91 to 1.59) | 2528 (10 randomised trials) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate 3 | The evidence suggests that PROM feedback probably makes little or no difference for pharmacological treatment. Pharmacological treatment was assessed using chart review. Two additional studies reported little or no difference between groups, a third study reported that those allocated to the intervention were more Liley to have their pharmacological treatment changed. |

|

| 195 per 1,000 | 256 per 1,000 (171 to 365) | |||||

| Hospital admissions | Study population | RR 0.96 (0.82 to 1.11) | 1681 (4 randomised trials) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate 1 | PROM feedback probably results in little to no difference in hospital admissions. | |

| 66 per 1,000 | 60 per 1,000 (45 to 79) | |||||

| Visits | Visits | |||||

| Study population | RR 1.09 (0.92 to 1.30) | 2777 (8 randomised trials) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low 1, 2, 3 | The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of PROM feedback on visits. | ||

| 502 per 1,000 | 514 per 1,000 (410 to 619) | |||||

| ER visits | ||||||

| Study population | RR 0.83 (0.68 to 1.01) | 812 (3 randomised trials) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate 3 | PROM feedback may reduce ER visits slightly. | ||

| 434 per 1,000 | 359 per 1,000 (293 to 427) | |||||

| Unscheduled visits | ||||||

| Study population | RR 1.43 (0.55 to 3.74) | 333 (2 randomised trials) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low 2, 3 | PROM feedback likely results in little to no difference in unscheduled visits. | ||

| 401 per 1,000 | 551 per 1,000 (194 to 862) | |||||

| Number of visits | ||||||

| SMD 0.02 (‐0.17 to 0.21) indicating no difference between PROM feedback and usual care. | ‐ | 2505 (7 randomised trials) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low 2, 4 | The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of PROM feedback on number of visits. | ||

| Referral | Study population | RR 2.00 (1.58 to 2.54) | 2519 (10 randomised trials) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low 1, 4 | The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of PROM feedback on referral. |

|

| 66 per 1,000 | 148 per 1,000 (113 to 190) | |||||

| Counselling (provided or referred to) | Study population | RR 1.61 (1.02 to 2.53) | 815 (4 randomised trials) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low 1, 4 | The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of PROM feedback on counselling (provided or referred to). | |

| 246 per 1,000 | 396 per 1,000 (251 to 622) | |||||

| Patient satisfaction | SMD 0.12 SD higher (0.12 lower to 0.36 higher) indicating no difference between PROM feedback and usual care. | ‐ | 2760 (10 randomised trials) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low 3, 4 | The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of PROM feedback on patient satisfaction (overall). | |

| Patient perceptions | Self efficacy | |||||

| SMD ‐0.05 (‐0.21 to 0.32) indicating no difference between PROM feedback and usual care. | ‐ | 349 (2 randomised trials) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate 2 | PROM feedback likely results in little to no difference in self efficacy. | ||

| Unmet needs | ||||||

| SMD ‐0.10 (‐0.22 to 0.02) indicating no difference between PROM feedback and usual care. | ‐ | 1025 (3 randomised trials) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate 2 | PROM feedback probably results in little to no difference in unmet needs. | ||

| Patient‐physician relationship | ||||||

| SMD 0.12 (‐0.12 to 0.36) indicating no difference between PROM feedback and usual care. | ‐ | 282 (2 randomised trials) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low 1, 3 | PROM feedback may result in little to no difference in patient‐physician relationship. | ||

| Quality of care | SMD 1.47 (1.00 to 2.17) favouring PROM feedback vs usual care. | ‐ | 1403 (2 randomised trials) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low 1, 2 | PROM feedback may increase the quality of care but the evidence is uncertain. | |

| Length of stay | SMD 0.18 (‐0.12 to 0.49) indicating no difference between PROM feedback and usual care. | ‐ | 174 (2 randomised trials) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low 1, 2 | The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of PROM feedback on length of stay | |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; SMD: standardised mean difference; RR: Risk ratio; OR: Odds ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 We downgraded one point for high risk of unblinding due to nature of intervention for most studies.

2 We downgraded one point for imprecision due to the small number of studies with wide confidence intervals included in meta‐analysis.

3 We downgraded one point for inconsistency due to high heterogeneity.

4 We downgraded two points for inconsistency due to very high heterogeneity.

1. Primary outcomes

1.1 Quality of Life

In total, 16 randomised trials assessed overall quality of life (QoL) using a generic PROM (Aardoom 2016; Basch 2016; Calkins 1994; Jha 2013; Kendrick 2017; LeBlanc 2019; Murillo 2017; Priebe 2007; Richardson 2008; Rosenbloom 2007; Santana 2010; Simons 2015; Slade 2006b; Strasser 2016; van der Hout 2020; Wikberg 2017).

Our meta‐analysis involving 11 studies including 2687 patients revealed a small improvement in QoL for patients receiving the intervention (standardised mean difference (SMD) = 0.15, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.05 to 0.26; Analysis 1.1). It was not possible to include the studies by Calkins 1994, LeBlanc 2019, Slade 2006b, Strasser 2016 and Wikberg 2017 in the meta‐analysis because of missing information. There was little or no difference between groups in satisfaction with health status at 12 months for Calkins 1994. There were little or no differences between groups in mean follow‐up patient‐rated quality of life for Calkins 1994, LeBlanc 2019, Slade 2006b, and Wikberg 2017. For Strasser 2016 the between‐arm difference in global QoL scores was in favour of the intervention arm. We rated the certainty of the evidence as moderate for this analysis, downgrading one point for risk of bias in the included studies.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Quality of Life, Outcome 1: Quality of life (all generic)

1.2 General health perceptions

We conducted a single meta‐analysis containing 552 patients from two randomised trials which had evaluated health perceptions (Mathias 1994; Richardson 2008). Our meta‐analysis revealed no effect of the intervention (SMD = 0.04, 95% CI = ‐0.17 to 0.24; Analysis 2.1). We could not include Stuck 2015 in the meta‐analyses because of how the data were reported. Patients in the intervention group of this study reported better health perceptions than those in the control group. We rated the certainty of the evidence as low; downgrading both for risk of bias arising from intervention design and imprecision due to the small number of studies available for analysis.

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2: General health perceptions, Outcome 1: General health perceptions (overall)

1.3 Functioning

In total, 17 studies assessed the impact of the intervention on physical functioning using different measures (Absolom 2021; Davis 2013; Detmar 2002; Girgis 2009; Gutteling 2008; Kornblith 2006; Lugtenberg 2020; Mathias 1994; Murillo 2017; Nimako 2017; Richardson 2008; Rosenbloom 2007; Scheidt 2012; Strasser 2016; Subramanian 2004; van Dijk‐de Vries 2015; Wolfe 2014). Our meta‐analysis of 14 studies included 2788 patients illustrated little or no effect of the intervention (SMD = ‐0.10, 95% CI ‐0.30 to 0.10; Analysis 3.1). We could not include in the meta‐analysis the studies by Absolom 2021 because of the way in which data had been reported, nor for Strasser 2016 or Wolfe 2014 due to missing information. There were little or no difference in physical functioning between intervention and control groups for any of these studies.

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3: Functioning, Outcome 1: Physical functioning

Forty studies evaluated the effect of the intervention on mental functioning (Amble 2014; Anker 2009; Berking 2006; Brody 1990; Calkins 1994; Davis 2013; De Jong 2012; Detmar 2002; Fann 2017; Girgis 2009; Gossec 2018; Gutteling 2008; Hansson 2013; Hawkins 2004; Jha 2013; Kornblith 2006; Lambert 2001; Lugtenberg 2020; Mathias 1994; Murillo 2017; Murphy 2012; Nimako 2017; Pouwer 2001; Probst 2013; Puschner 2009; Reese 2009; Richardson 2008; Rosenbloom 2007; Rubenstein 1995; Scheidt 2012; Schottke 2019; Simon 2012; Strasser 2016; Subramanian 2004; Trudeau 2001; van der Hout 2020; van Dijk‐de Vries 2015; Whipple 2003; Wikberg 2017; Wolfe 2014). Our meta‐analysis of thirty‐four studies, which included 7782 patients demonstrated a small positive benefit of the intervention (SMD = 0.16, 95% CI 0.06 to 0.27; Analysis 3.2). It was not possible to include studies by Calkins 1994, De Jong 2012, Strasser 2016, Trudeau 2001, Wikberg 2017 and Wolfe 2014 in the meta‐analysis because of missing information. In Calkins 1994 the number of patients in the intervention and usual care groups was not specified, and there was little or no difference between groups for De Jong 2012, Strasser 2016, Trudeau 2001, Wikberg 2017, and Wolfe 2014.

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3: Functioning, Outcome 2: Mental functioning

Social functioning was assessed by 16 studies (Bastiaansen 2018; Blonigen 2015; Calkins 1994; Davis 2013; Detmar 2002; Fann 2017; Girgis 2009; Kendrick 2017; Lugtenberg 2020; Mathias 1994; Murillo 2017; Nimako 2017; Richardson 2008; Rosenbloom 2007; Rubenstein 1995; van Dijk‐de Vries 2015). Meta‐analysis of 15 studies (Bastiaansen 2018; Blonigen 2015; Davis 2013; Detmar 2002; Fann 2017; Girgis 2009; Kendrick 2017; Lugtenberg 2020; Mathias 1994; Murillo 2017; Nimako 2017; Richardson 2008; Rosenbloom 2007; Rubenstein 1995; van Dijk‐de Vries 2015) including a total of 2632 patients revealed no effect of the intervention (SMD = 0.02, 95% CI ‐0.06 to 0.09; Analysis 3.3). It was not possible to include in the meta‐analysis the study by Calkins 1994 because of missing information. There was no difference between intervention and control participants in social function.

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3: Functioning, Outcome 3: Social Functioning

We rated the certainty of the evidence as very low for both the physical functioning and mental functioning meta‐analyses, downgrading the evidence for both risk of bias in the included studies and statistical heterogeneity (I2 = 85% and 80%, respectively). In both cases, the heterogeneity appeared to be driven by the inclusion of Subramanian 2004, a large study with high risk of bias that produced markedly different results to the majority of other studies. The evidence for social functioning was rated as moderate, with the evidence downgraded due to risk of bias of the included studies on the basis of un‐blinding due to the nature of the intervention.

1.4 Symptoms

We conducted 11 meta‐analyses which assessed the impact of PROM feedback on patient symptoms including pain, fatigue, insomnia, anorexia, nausea, diarrhoea, constipation, dyspnoea, cough, as well as symptoms of anxiety and depression.

We included nine studies (10 comparisons: Cherkin 2018; Detmar 2002; Hadjistavropoulos 2009; Hoekstra 2006; Kazis 1990; Lugtenberg 2020; Mathias 1994; Nimako 2017; Richardson 2008) in a meta‐analysis assessing the impact of the intervention on pain. Our analysis included 2386 participants and found little or no improvement in pain scores associated with the intervention (SMD = ‐0.00, 95% CI ‐0.09 to 0.08, Analysis 4.1). It was not possible to include in the meta‐analysis on pain the studies by Kroenke 2018 and Strasser 2016 because of missing information nor Bryant 2020 because of the nature of the categorical nature of the data. For Kroenke 2018, participants allocated to the intervention group had a slight improvement on the PROMIS pain scale (0.07; P > 0.10). There was little or no difference between groups in Strasser 2016 and Bryant 2020.

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4: Symptoms, Outcome 1: Pain

Seven studies evaluated fatigue (Bryant 2020; Hoekstra 2006; Kroenke 2018; Lugtenberg 2020; Nimako 2017; Strasser 2016; Subramanian 2004). Pooled analysis of four studies and 741 participants (Hoekstra 2006; Lugtenberg 2020; Nimako 2017; Subramanian 2004) revealed little or no improvement for participants in the intervention group (SMD = 0.03, 95% CI ‐0.29 to 0.36, Analysis 4.2). It was not possible to include the study by Bryant 2020 because of the categorical nature of the reported data, nor the studies by Kroenke 2018 and Strasser 2016 in the meta‐analysis on fatigue because of missing information. For Kroenke 2018 there was a slight improvement for participants allocated to the intervention and there were little or no differences in Bryant 2020 and Strasser 2016.

4.2. Analysis.

Comparison 4: Symptoms, Outcome 2: Fatigue

Dyspnoea was assessed in six studies (Hoekstra 2006; Lugtenberg 2020; Nimako 2017; Strasser 2016; Subramanian 2004; White 1995) and our meta‐analysis of five studies and 765 patients found no effect of the intervention (SMD = ‐0.11, 95% CI ‐0.32 to 0.11; Analysis 4.3). It was not possible to include the study by Strasser 2016 because of missing information (little or no differences reported for this study).

4.3. Analysis.

Comparison 4: Symptoms, Outcome 3: Dysponea

Cough was assessed in two studies (Hoekstra 2006, White 1995) and our meta‐analyses (N = 122) suggested that the intervention had little or no effect on cough (SMD = ‐0.14, 95% CI ‐0.75 to 0.480; Analysis 4.4).

4.4. Analysis.

Comparison 4: Symptoms, Outcome 4: Cough

Nausea was assessed in three studies (Hoekstra 2006; Rosenbloom 2007; Strasser 2016). Our meta‐analysis of two studies (239 patients) revealed little or no effect of the intervention (SMD = 0.08, 5% CI ‐0.76 to 0.59; Analysis 4.5). The meta‐analysis did not include the study by Strasser 2016 due to missing information (no differences reported between intervention and control group).

4.5. Analysis.

Comparison 4: Symptoms, Outcome 5: Nausea

Vomiting was assessed in the study by Hoekstra 2006. The severity scores for vomiting in the control group were lower than those in the intervention group (median 2 compared to median 4, P < 0.05).

Symptoms of depression were evaluated in 16 studies which included 3449 patients (Bastiaansen 2018; Boyer 2013; Brodey 2005; Cherkin 2018; Dowrick 1995a; Fann 2017; Hadjistavropoulos 2009; Jha 2013; Kazis 1990; Kendrick 2017; Kornblith 2006; Lugtenberg 2020; Picardi 2016; Scheidt 2012; Simons 2015; Whooley 2000). Our meta‐analysis revealed a small improvement in depression symptoms for patients receiving the intervention (SMD = ‐0.12, 95% CI ‐0.20 to ‐0.05; Analysis 4.6). Anxiety was evaluated in eight studies which included 2334 (Brodey 2005; Brody 1990; Cherkin 2018; Dailey 2002; Kazis 1990; Kornblith 2006; Lugtenberg 2020; Mathias 1994). Our meta‐analysis revealed a small improvement in anxiety symptoms (SMD = ‐0.17, 95% CI ‐0.31 to ‐0.03; Analysis 4.7).

4.6. Analysis.

Comparison 4: Symptoms, Outcome 6: Depressive symptoms

4.7. Analysis.

Comparison 4: Symptoms, Outcome 7: Anxiety symptoms

We graded the certainty of the evidence as moderate for the pain and depression analyses, downgrading the evidence for risk of bias. The certainty of the evidence for the fatigue, dyspnoea, cough, nausea, and anxiety symptoms was very low with studies being downgraded for risk of bias, inconsistency, and imprecision. The explaination for the heterogeneity was not found.

1.5 Adverse effects

We did not find studies reporting adverse effects defined as distress following or related to PROM completion. Some studies reported on outcomes associated with the intervention that can be perceived as adverse (e.g. anxiety and depression), however we reported those outcomes in other categories. Three studies studied the impact of the intervention on adverse events related to the usual management of the relevant diseases (Gilliam 2004; Murillo 2017; Wikberg 2017). Due to differences in the nature and reporting of data it was not possible to conduct a meta‐analysis. In the study by Gilliam 2004, patients in intervention group experienced a significantly higher improvement in a self‐reported adverse events scale than those in the control group. There were no differences between intervention and control groups in number of hypoglycaemic events in the study by Murillo 2017, and no adverse events were reported for any participant in the study by Wikberg 2017.

2. Secondary outcomes

2.1 Communication between patients and clinicians