Summary

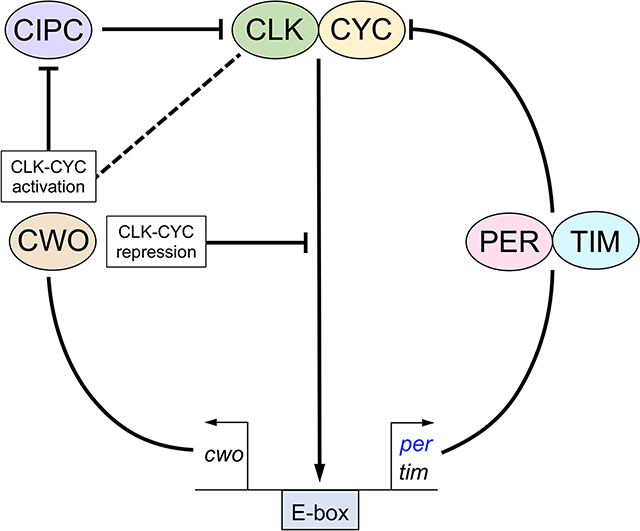

The Drosophila circadian clock is driven by a transcriptional feedback loop in which CLOCK-CYCLE (CLK-CYC) binds E-boxes to transcribe genes encoding the PERIOD-TIMELESS (PER-TIM) repressor, which releases CLK-CYC from E-boxes to inhibit transcription. CLOCKWORK ORANGE (CWO) reinforces PER-TIM repression by binding E-boxes to maintain PER-TIM bound CLK-CYC off DNA, but also promotes CLK-CYC transcription through an unknown mechanism. To determine how CWO activates CLK-CYC transcription, we identified CWO target genes that are upregulated in the absence of CWO repression, conserved in mammals and preferentially expressed in brain pacemaker neurons. Among the genes identified was a putative ortholog of mouse Clock Interacting Protein Circadian (Cipc), which represses CLOCK-BMAL1 transcription. Reducing or eliminating Drosophila Cipc expression shortens period while overexpressing Cipc lengthens period, consistent with previous work showing that Drosophila Cipc represses CLK-CYC transcription in S2 cells. Cipc represses CLK-CYC transcription in vivo, but not uniformly as per is strongly repressed, tim less so, and vri hardly at all. Long period rhythms in cwo mutant flies are largely rescued when Cipc expression is reduced or eliminated, indicating that increased Cipc expression mediates period lengthening of cwo mutants. Consistent with this behavioral rescue, eliminating Cipc rescues the decreased CLK-CYC transcription in cwo mutant flies, where per is strongly rescued, tim is moderately rescued and vri shows little rescue. These results suggest a mechanism for CWO-dependent CLK-CYC activation: CWO inhibition of CIPC repression promotes CLK-CYC transcription. This mechanism may be conserved since cwo and Cipc perform analogous roles in the mammalian circadian clock.

Keywords: Circadian clock, Drosophila, feedback loop, transcriptional repression, activity rhythms, clock gene mutants, ChIP-seq, RNA-seq

eTOC blurb

In addition to its role as a CLK-CYC repressor CWO activates CLK-CYC transcription via an unknown mechanism. Rivas et al. show that CWO represses the fly ortholog of mouse CLOCK-BMAL1 repressor CIPC. Molecular and behavioral analysis of Cipc mutant and overexpression flies shows CWO activates CLK-CYC transcription by inhibiting Cipc repression.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Daily rhythms in animal behavior, physiology and metabolism are driven by cell-autonomous circadian clocks. These clocks keep time via one or more transcriptional feedback loops (TFLs) that drive ~24h rhythms in gene expression 1,2. The main timekeeping TFL in Drosophila is activated around mid-day by CLOCK-CYCLE (CLK-CYC) binding to E-boxes to activate transcription of hundreds of genes whose mRNAs peak around dusk, including the period (per) and timeless (tim) repressors 3. PER-TIM complexes accumulate in the evening and bind CLK-CYC to inhibit transcription, but after dawn PER-TIM is degraded, thereby permitting CLK-CYC binding to initiate another round of transcription 3. In addition, CLK-CYC activates Pdp1ε and vri to initiate an interlocked feedback loop that drives transcription of genes whose mRNAs peak around dawn 4,5 Although rhythmic transcription largely peaks around dawn and dusk, mRNAs peak at all times during the circadian cycle through a combination of transcriptional and post-transcriptional processes 1,2.

A proposed third feedback loop within the Drosophila clock involves the basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH)-ORANGE transcriptional repressor CLOCKWORK ORANGE (CWO) 6–9. CLK-CYC drives rhythms in cwo transcription with a peak near dusk 6–8, but the abundance of CWO protein is constant over a diurnal cycle 10. However, CWO binds E-boxes to displace CLK-CYC-PER-TIM complexes during the late night and early morning, thereby decreasing trough levels of CLK-CYC transcription and reinforcing PER-TIM repression 10. Consequently, cwo null mutants have higher trough levels of CLK-CYC transcription, but surprisingly peak levels of CLK-CYC transcription are also much lower in cwo null mutant flies 6–9, suggesting that cwo also promotes CLK-CYC transcription. Like other mutants that compromise CLK-CYC transcription, cwo null mutants have weak behavioral rhythms with a long >26h period 6–9. Despite the impact of cwo-dependent CLK-CYC activation on behavioral rhythms, how CWO promotes transcriptional activation is not known.

To determine how CWO promotes CLK-CYC transcription, we identified CWO binding targets that are upregulated in cwo5073 mutant flies, conserved in mammals and preferentially expressed in brain pacemaker neurons. Among the eight candidate genes is an ortholog of mouse Clock interacting protein circadian (Cipc), which functions to repress CLOCK-BMAL1 transcription 11. In cwo5073 mutant flies Cipc mRNA levels are increased, suggesting that CWO represses Cipc. Overexpressing Cipc decreases CLK-CYC transcription and lengthens period, while Cipc RNAi knockdown and Cipc null mutant flies increase CLK-CYC transcription and shorten period, suggesting that Cipc represses CLK-CYC transcription. Consistent with these behavioral results, in vivo experiments with Cipc RNAi knockdown, Cipc mutant and Cipc overexpression flies show that Cipc represses CLK-CYC targets per and tim, but repression is variable with per showing strong repression, tim showing moderate repression and vri showing little or no repression. Moreover, Cipc RNAi knockdown and Cipc mutant flies decrease circadian period of cwo5073 flies by ~2.5h, suggesting that increased Cipc levels account for most of the period lengthening in cwo5073 flies. Indeed, when Cipc levels are reduced in cwo mutant flies, the low expression levels of CLK-CYC targets are rescued, albeit variably, with per strongly increased, tim modestly increased and vri not increased. These results, together with previous Cipc transcription assays in Drosophila S2 cells 12, suggest that CWO activates CLK-CYC activity primarily by relieving Cipc repression in Drosophila.

Results

Identification of CWO and CLK target genes in Drosophila

CWO reinforces PER-TIM repression of core clock gene transcription by antagonizing CLK-CYC binding to E-boxes 10, but also functions to promote CLK-CYC transcription of core clock genes 6–9. To determine the relationship between CWO and CLK-CYC binding across the genome, we identified CWO and CLK binding sites via ChIP-seq. To immunoprecipitate (IP) CWO with high sensitivity and specificity, a transgenic line bearing a modified BAC clone that expresses C-terminal HA-tagged CWO (cwo-HA) was generated (see STAR Methods). HA antibody detects constant levels of CWO in heads from cwo-HA; cwo5073 flies collected during a 12-h light/12-h dark (LD) cycle (Figure S1), consistent with CWO levels in wild-type flies 10. Moreover, cwo-HA; cwo5073 flies partially restore the ~26.6h period of cwo5073 flies to 24.8h (Table S1), indicating that CWO-HA protein is functional.

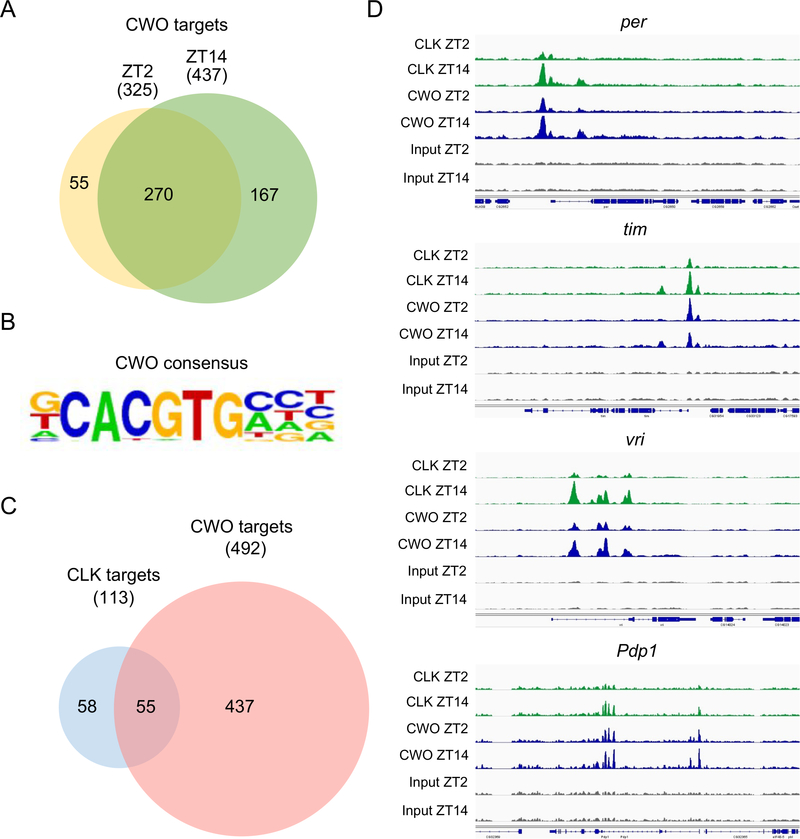

To identify CWO target genes, HA antibody was used to IP CWO-HA from heads of cwo-HA; cwo5073 flies collected during transcriptional repression at Zeitgeber Time 2 (ZT2, where ZT0 is lights-on and ZT12 is lights-off during an LD cycle) and transcriptional activation at ZT14 for ChIP-seq analysis. CWO binding peaks were identified at 393 sites at ZT2 and 549 sites at ZT 14 (Data S1E, F), where binding was enriched at Promoter-transcription start sites (TSS) (defined as −1kb to +100bp from the TSS) and introns (Table S2). To identify CWO target genes, peaks mapping to intergenic regions were excluded, resulting in a total of 492 target genes, with 270 in common between ZT2 and ZT14 (Figure 1A, Data S1A, B). Previously characterized CWO binding targets per, tim, vri, Pdp1 and cwo rank in the top half of genes based on their peak scores in HOMER at both ZT2 and ZT14 (Data S1A, B). Analysis of DNA binding motifs in CWO binding peaks identified a consensus sequence containing a central CACGTG E-box (Figure 1B), consistent with previous experiments showing that CWO binds CACGTG E-box sequences 7,8,10.

Figure 1. ChIP-seq analysis of CLK and CWO binding sites.

(A) Venn diagram of CWO ChIP-seq targets at ZT2 (yellow) and ZT14 (green). The numbers in the brackets are the total number of targets for each time point, excluding CWO binding sites that map to intergenic regions. The numbers in the circles and the overlap region indicate the numbers of targets present in each category or in both categories, respectively. (B) The top five motifs enriched in CWO binding peaks contain canonical CACGTG E-box sequences. (C) Venn diagram comparing CLK ChIP-seq targets (blue) and CWO ChIP-seq targets (red). The numbers shown are determined as described in panel A. (D) ChIP-seq track showing CLK (green) and CWO-HA (blue) binding sites for the core clock genes tim, vri, per, Pdp1 and cwo at ZT2 and ZT14. Chromatin prepared from flies collected at ZT2 and ZT14, but not IPed, were used as input (gray). Binding peaks are based on the analysis of ChIP-seq data in HOMER (see STAR Methods). See also Figure S1, Tables S1 and S2 and Data S1.

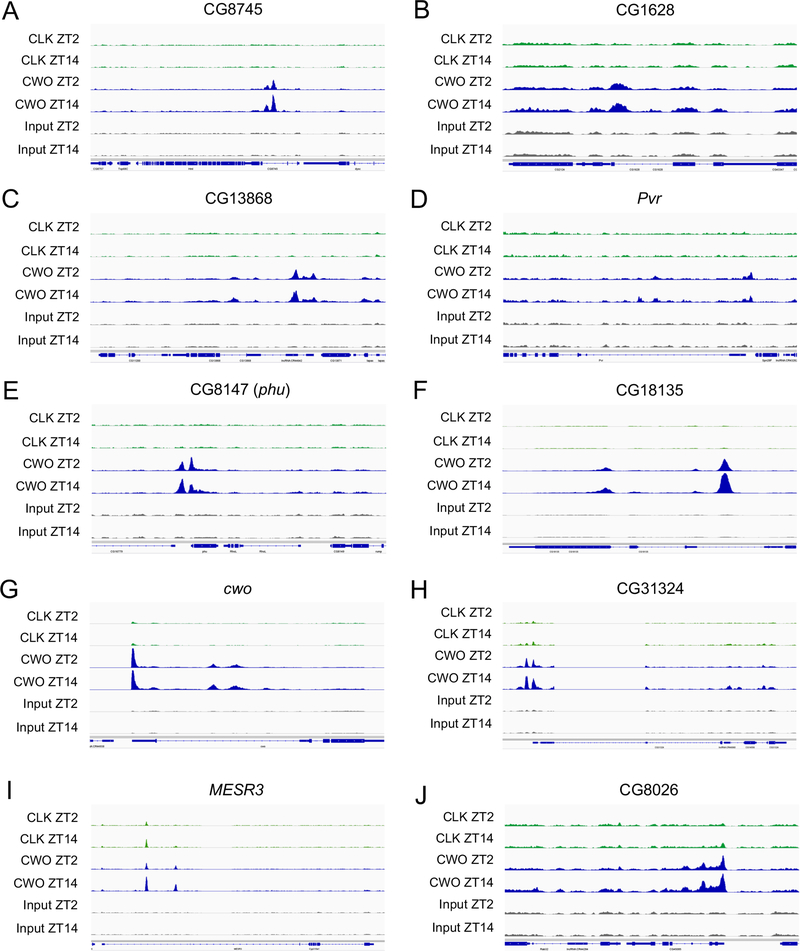

To identify common binding targets of CWO and CLK, CLK was IPed with an anti-CLK antibody previously used for ChIP PCR analysis of CLK binding 10,13,14. ChIP-seq of CLK binding in heads from cwo-HA; cwo5073 flies collected at ZT2 and ZT14 revealed 22 and 149 CLK binding peaks, respectively (Data S1G, H). These binding peaks identified a total 113 CLK target genes (14 at ZT2, 110 at Z14), including the core clock genes per, tim, vri and Pdp1 (Data S1C, D). Almost half the CLK target genes are also bound by CWO (Figure 1C), where CWO and CLK binding overlap (Data S1A–D). This overlap includes sites within the regulatory regions of clock genes (Figure 1D; Data S1A–D), consistent with earlier studies showing that CWO competes with CLK for E-box binding 6–8,10. These data suggest that the competition for CLK and CWO binding at clock genes is broadly used for regulating circadian transcription. In contrast to the large overlap in CWO binding to CLK target genes, CLK only binds ~11% of CWO target genes (Figure 1C, Data S1A–D), suggesting that CWO controls gene expression independent of the circadian clock. Although CWO targets many genes independent of CLK (Figure 2A–F), a subset of genes including cwo show strong CWO binding at sites with weaker CLK binding than at clock genes (Figure 2G–J; Figure 1D). These differences in CWO and CLK-CYC binding are presumably due to the nature of the target sequences since CWO and CLK-CYC bind CACGTG E-boxes with different flanking nucleotides (Figure 1B) 8,15.

Figure 2. CWO target genes having prominent CWO binding peaks.

ChIP-seq tracks are shown for CLK (green) and CWO-HA (blue) binding sites for the indicated target genes at ZT2 and ZT 14. Chromatin prepared from flies collected at ZT2 and ZT 14, but not IPed, were used as input (gray). Binding peaks are based on the analysis of ChIP-seq data in HOMER (see STAR Methods). See also Figure S2 and Figure S4.

Differential gene expression in w1118 control vs. cwo5073 mutant flies

Given that CWO acts as a transcriptional repressor 6–8, we reasoned that CWO activates CLK-CYC transcription indirectly via transcriptional repression. To identify genes that are repressed by CWO, we compared the transcriptome in heads of control (w1118) and cwo5073 flies collected at 4h intervals between ZT2 to ZT22 during an LD cycle. Genes repressed by CWO were defined as having expression levels ≥ 50% higher on average (i.e. across all six timepoints) in cwo5073 flies than w1118 controls. This analysis identified a total of 401 genes that are upregulated in cwo5073 flies (Table S3).

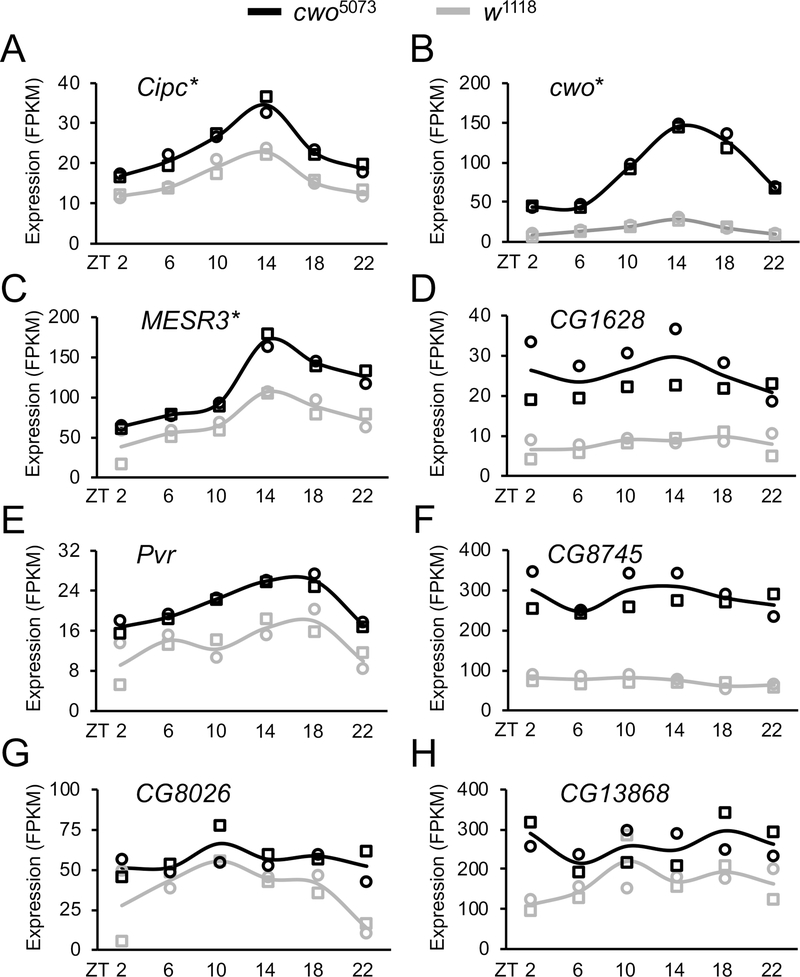

We reasoned that one or more of the genes upregulated in cwo5073 flies lengthen circadian period by repressing CLK-CYC transcription. Thus, repression of these CLK-CYC repressors by CWO under normal circumstances would, in effect, activate CLK-CYC transcription. In this scenario, loss of these CWO-dependent repressors of CLK-CYC transcription would shorten circadian period, which can be tested via RNAi knockdown and/or loss-of-function mutants. To prioritize the 401 genes upregulated in cwo5073 flies we selected genes that 1) are preferentially expressed in brain pacemaker neurons that control activity rhythms 16, 2) are direct targets of CWO binding, 3) play a role in regulating transcription or transcription factor activity (e.g. transcription factors, chromatin modifiers, kinases, phosphatases, ubiquitin ligases) and 4) have mammalian orthologs. Of the 401 genes upregulated in cwo5073 flies, 24 are preferentially expressed in brain pacemaker neurons (Table 1). Of these 24 genes, eight are CWO targets: cwo, CG8745, CG1628, Misexpression suppressor of ras 3 (MESR3), CG13868, PDGF- and VEGF-receptor related (Pvr), CG8026 and CG31324 (Table 1). Remarkably, all eight of these genes contain strong CWO-only binding or strong CWO binding at sites with weak CLK binding relative to clock genes (Figure 1; Figure 2, Data S1A–D), suggesting that CWO binding to these sites represses transcription. However, not all genes upregulated in cwo5073 flies show CWO binding (Figure S2), indicating that CWO indirectly upregulates their expression. The expression of genes targeted by CWO is repressed throughout the circadian cycle; mRNA levels of these eight genes are higher in cwo5073 flies at all times of day whether they are rhythmically expressed or not (Figure 3, Table S3). We used information from Flybase (https://flybase.org/) to determine whether these genes play a role in regulating transcription and have mammalian orthologs 17. CG8745, CG1628, CG8026 and Pvr are conserved in mammals, but their predicted roles as an ethanolamine-phosphate phospho-lyase (CG8745), L-ornithine transferase (CG1628), SLC25-family mitochondrial transporter (CG8026) and membrane-bound growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase (Pvr) are not directly connected to transcriptional regulation (Table 1). Although CG13868 and CG31324 display no known molecular or biological function or mammalian orthologs in Flybase, MESR3 is proposed to function as a transcription factor, but has no mammalian ortholog (Table 1).

Table 1.

Differentially expressed genes enriched in brain pacemaker neurons.

| gene | Proposed function | CWO target a | Mosquito ortholog b | Mouse ortholog b | adjP c | Fold-change d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cwo | DNA-binding transcription repressor | X | XP_038105613.1 | NP_077789.1 | 1.60E-21 | 5.65 |

| CG8745 | transferase activity | X | XP_029717543.1 | AAH43680.2 | 3.00E-63 | 3.94 |

| CG1628 | amino acid transmembrane transporter activity | X | XP_029709683.1 | NP_001345900.1 | 1.16E-29 | 3.22 |

| ade3 | phosphoribosylami ne-glycine ligase | ---- | XP_035915073.1 | NP_001344280.1 | 1.62E-14 | 2.66 |

| pug | formate-tetrahydrofolate ligase | ---- | XP_021710488.1 | NP_620084.2 | 1.60E-09 | 2.50 |

| ctrip | ubiquitin protein ligase | ---- | XP_021710575.1 | NP_598736.4 | 3.68E-03 | 1.96 |

| Ahcy13 | Adenosylhomo cysteinase | ---- | XP_001659155.1 | AAA70378.1 | 1.43E-07 | 1.82 |

| Mct1 | monocarboxylic acid transmembrane transporter | ---- | XP_038122556.1 | NP_766426.1 | 4.10E-06 | 1.77 |

| Tsf1 | metal ion binding | ---- | XP_019565638.2 | NP_598738.1 | 8.05E-04 | 1.70 |

| MESR3 | DNA-binding transcription factor, RNA pol II-specific | X | EDS26580.1 | ---- | 3.33E-03 | 1.67 |

| Gadd45 | activation of MAPKKK | ---- | XP_001652310.1 | NP_031862.1 | 3.63E-07 | 1.63 |

| CG13868 | unknown | X | EAT33738.1 | ---- | 3.49E-06 | 1.63 |

| Pvr | transmembrane receptor protein tyrosine kinase | X | XP_035905721.1 | NP_001076785.1 | 1.02E-04 | 1.58 |

| CG8026 | FAD transmembrane transporter activity | X | ETN63560.1 | NP_765990.2 | 2.81E-02 | 1.57 |

| h | DNA-binding transcription repressor | ---- | XP_019540047.1 | EDK97718.1 | 2.57E-13 | 1.57 |

| gem | DNA-binding transcription activator | ---- | XP_021698725.1 | NP_076244.2 | 6.12E-08 | 1.56 |

| CG7530 | signaling receptor activity | ---- | XP_038114720.1 | NP_001346839.1 | 1.38E-10 | 1.56 |

| bnb | gliogenesis | ---- | ---- | ---- | 1.79E-10 | 1.54 |

| to | circadian rhythm | ---- | XP_001865588.1 | ---- | 4.87E-02 | 1.53 |

| CG3376 | acid sphingomyelin phosphodiesterase activity | ---- | XP_038113603.1 | NP_065586.3 | 8.51E-03 | 1.52 |

| dom | Chromatin remodeling | ---- | XP_038118809.1 | XP_017176624.1 | 9.41E-03 | 1.51 |

| CG1407 | protein-cysteine S-palmitoyl transterase activity | ---- | XP_038118596.1 | NP_001347026.1 | 1.51E-02 | 1.51 |

| CG31324 | unknown | X | ETN61479.1 | NP 001276358.1 | 1.05E-03 | 1.50 |

| gpp | histone methyl transterase | ---- | XP_038116347.1 | NP_955354.1 | 7.33E-03 | 1.50 |

CWO targets were aetinea based on cnip-seq aata (Data S1).

NCBI Keterence sequence or mosquito and mouse orthologs identified by BlastP or remote ortholog search using HHMEK (see STAR Methods).

Adjusted p-value using DESeq2.

Linear told-change values tor upregulated genes in cwo5073 tlies (see STAR Methods). See also Figure S3.

Figure 3. Expression of direct CWO targets that are upregulated in cwo5073 flies.

RNA-seq analysis was carried out on heads from w1118 (gray lines) and cwo5073 (black lines) flies entrained in LD cycles and collected at the indicated times (see STAR Methods). Graphs show mRNA expression levels of two independent biological replicates (open circles and squares) in fragments per kilobase million (FPKM) for the indicated genes. Asterisks indicate rhythmic expression in w1118 flies. See also Table S3.

To better characterize the function and/or conservation of CG13868, CG31324 and MESR3 we conducted InterPro database searches using the HMMER web server (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/hmmer/) 18. Consistent with Flybase, all three genes have mosquito orthologs, but no mammalian orthologs were identified (Table 1). However, a HMMER search using the mosquito ortholog of CG31324 detected sequence similarity in Drosophila and mammals to a domain called CiPC (Figure S3A). The CiPC domain is a highly conserved portion of the CLOCK-Interacting Protein Circadian (CIPC) protein, which was previously characterized as a repressor of CLOCK-BMAL1 activity 11. Although mammalian Cipc was not initially thought to be present in invertebrates, recent reports identified CG31324 as the Drosophila homolog of mammalian Cipc based on conservation within the CiPC domain, the ability of CG31324 to repress CLK-CYC transcription in S2 cells and/or direct interaction between the CiPC domain of CG31324 and the CLOCK exon 19 analogous region from Drosophila CLK 12,19. Despite the limited sequence conservation outside the CiPC domain between Drosophila CG31324 and Cipc in mammals or mosquitoes (Figure S3B), the conserved function of CG31324 within the circadian clock suggests that this gene is a putative Cipc ortholog, which we will refer to hereafter as Drosophila Cipc. Like Cipc in mammals, Drosophila Cipc has a similar gene organization including 14 canonical CACGTG E-boxes (Figure S4). Several of these E-boxes coincide with CLK and/or CWO binding peaks (Data S1A–D, Figure 2) 20, consistent with Cipc mRNA cycling (Figure 3A; Table S3). To determine if Drosophila Cipc functions within the circadian clock in vivo we tested whether altered Cipc expression disrupts behavioral rhythms.

Behavioral analysis of Drosophila strains with altered Cipc expression

The ability of Cipc to repress CLK-CYC transcription in S2 cells suggests that loss of Cipc function activates CLK-CYC transcription, which is known to shorten circadian period in flies 21. To test if reducing cipc expression shortens circadian period, a UAS-RNAi transgene targeting coding and 3’UTR sequences of the last exon of Cipc (UAS-CipcRNAi#1) was driven by tim-Gal4 in all clock cells and pdf-Gal4 in ventrolateral neurons (LNvs). The period of tim-Gal4 driven UAS-cipcRNAi#1 flies was 23.07h, which is significantly shorter (p<10−4) than that of UAS-CipcRNAi#1 and tim-Gal4 controls, but the 23.69h period of pdf-Gal4 driven UAS-CipcRNAi#1 flies was only significantly shorter than the pdf-Gal4 control (p<10−3), not the UAS-cipcRNAi#1 control (p=0.813) (Table 2). To confirm the period shortening of clock cell-specific RNAi knockdown, a second UAS-RNAi transgene targeting coding sequences in the last exon of Cipc (UAS-CipcRNAi#2) was tested. The period of tim-Gal4 driven UAS-CipcRNAi#2 was shortened to 23.18h, which is significantly shorter than tim-GaI4 controls (p<10−6) but not UAS-CipcRNAi#2 controls (p=0.051) (Table 2), whereas the 23.87h period of pdf-GaI4 driven UAS-CipcRNAi#2 flies was not significantly shorter than either pdf-GaI4 (p=0.147) or UAS-CipcRNAi#2 (p=0.037) controls (Table 2). The relatively weak effect of pdf-Gal4 driven UAS-CipcRNAi on period may be due to insufficient GaI4 expression, as previously noted when UAS-Clk failed to shorten period with pdf-GaI4 but did with tim-GaI4 21. A recent study also found that tim-Gal and pdf-Gal4 driven UAS-CipcRNAi#1 shortened circadian period, though not significantly so, whereas a third Cipc RNAi line lengthened period 19. The period lengthening by the third Cipc RNAi is difficult to reconcile with the period shortening by UAS-CipcRNAi#1 and UAS-CipcRNAi#2 since the third Cipc RNAi, though shorter, targets sequences that overlap with the other two Cipc RNAis in the last exon of Cipc 17. Nevertheless, short period rhythms in clock cell-specific Cipc RNAi knockdown flies are consistent with the period shortening seen in Per1-luciferase rhythms when Cipc is knocked down via RNAi in NIH3T3 fibroblasts 11.

Table 2.

Activity rhythms of flies with altered Cioc expression.

| Genotype | Total | % Rhythmic | Period ± s.e.m. | Strength ± s.e.m. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| W 1118 | 32 | 90.62 | 23.59 ± 0.05 | 150.12 ± 20.22 |

| W1118; tim-Gal4/+; +/+ | 32 | 81.25 | 24.03 ± 0.07 | 177.67 ± 29.62 |

| W1118; +/+; pdf-Gal4/+ | 24 | 91.66 | 24.13 ± 0.07 | 266.81 ± 38.50 |

| W1118; U-CipcRNAi#1/tim-Gal4; +/+ a | 30 | 100 | 23.07 ± 0.06 1 | 210.78 ± 16.92 |

| W1118; U-CipcRNAi#1/+; pdf-Gal4/+ a | 33 | 100 | 23.69 ± 0.05 | 187.49 ± 21.24 |

| W1118; U-CipcRNAi#1/+; +/+ a | 32 | 96.87 | 23.67 ± 0.07 | 102.42 ± 16.06 |

| W1118; U-CipcRNAi#2/tim-Gal4; +/+ b | 12 | 100 | 23.18 ± 0.05 2 | 209.20 ± 49.35 |

| W1118; U-CipcRNAi#2/+; pdf-Gal4/+ b | 12 | 91.66 | 23.87 ± 0.09 | 226.64 ± 39.57 |

| W1118; U-CipcRNAi#2/+; +/+ b | 24 | 87.50 | 23.51 ± 0.09 | 244.98 ± 42.84 |

| W1118; +/+; CpicΔ11 | 19 | 68.42 | 22.93 ± 0.17 3 | 48.92 ± 17.26 8 |

| W1118; +/+; CpicΔ22 | 14 | 85.71 | 23.11 ± 0.18 4 | 45.33 ± 8.21 9 |

| W1118; +/+; CpicΔ64 | 64 | 82.81 | 23.00 ± 0.10 5 | 69.84 ± 7.05 10 |

| W1118; +/tim-Gal4; U-Cpic/+ c | 32 | 18.75 | 25.93 ± 1.32 6 | 8.17 ± 3.37 11 |

| W1118; +/+; pdf-Gal4/ U-Cpic c | 25 | 64.00 | 24.70 ± 0.16 7 | 72.75 ± 22.16 12 |

| W1118; +/+; U-Cpic/+ c | 31 | 93.54 | 23.60 ± 0.05 | 158.81 ± 22.50 |

Activity rhythm period in constant darkness is given in hours ± standard error ot the mean (s.e.m.).

UAS-CipcRNAi#1, VDKC # KK107220.

UAS-CipcRNAi#2, BDSC #28774.

UAS-Cpic, FLYOKF #F004315.

Period signiticantly (p<10−4) shorter than W1118; tim-Gal4/+; +/+ and W1118; UAS-CipcRNAi1/+; +/+ control flies.

Period signiticantly (p<10−5) shorter than W1118; tim- Gal4/+; +/+ control tlies but not signiticantly (p=0.051) shorter than W1118; UAS-CpicRNAi#2/+; +/+ control flies.

Period signiticantly (p=0.005) shorter than W1118 control flies.

Period signiticantly (p=0.046) shorter than W1118 control flies.

Period signiticantly (p<10−3) shorter than W1118 control flies.

Period signiticantly (p<10−3) longer than W1118; tim-Gal4/+; +/+ and W1118; +/+; UAS-Cpic/+ control flies.

Period significantly (p<10−3) longer than W1118; +/+; pdf-Gal4/+ and W1118; +/+; UAS-Cpic/+ control flies.

Power significantly (p=0.001) lower than W1118 control flies.

Power significantly (p=0.001) lower than W1118 control flies.

Power significantly (p<10−3) lower than W1118 control flies.

Power significantly (p<10−4) lower than W1118; tim-Gal4/+; +/+ and W1118; +/+; UAS-Cpic/+control flies.

Power significantly (p<10−3) lower than W1118; +/+; pdf-Gal4/+ control flies but not significantly (p=0.068) lower than W1118; +/+; UAS-Cpic/+ control flies. See also Figure S5.

Given that clock cell-specific Cipc RNAi knockdown doesn’t uniformly shorten circadian period, we assessed circadian activity rhythms in Cipc null mutants that were generated using CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing (see STAR Methods). Three Cipc mutants were recovered that deleted 11 bp (CipcΔ11), 22bp (CipcΔ22) and 64bp (CipcΔ64) of coding sequence in exon 1 (Figure S5A). The translation products for CipcΔ11, CipcΔ22 and CipcΔ64 are predicted to produce truncated CIPC proteins containing the first 16 (CipcΔ22) or 17 (CipcΔ11, CipcΔ64) amino acids of CIPC and a frameshifted coding segment (Figure S5B). Given that these truncated proteins only contain the first 16 or 17 natural CIPC amino acids and lack of the conserved CiPC domain, we consider them to be null for CIPC function. Behavioral analysis of these Cipc mutants revealed that eliminating CIPC significantly (p<0.05) shortens period to ~23h and significantly (p<0.001) reduces rhythm amplitude by >50% (Table 2). This period is similar to that seen in tim-Gal4 driven UAS-CipcRNAi#1 and UAS-CipcRNAi#2, suggesting that RNAi knockdown in these lines is effective.

The short period rhythms of Cipc RNAi knockdowns and null mutant strains suggest that Cipc represses CLK-CYC transcription. If this is the case, then increasing Cipc expression should increase repression of CLK-CYC transcription and lengthen circadian period. To overexpress Cipc, a UAS-Cipc transgene was driven by tim-Gal4 or pdf-Gal in w1118 flies. Overexpression of Cipc in all clock cells by tim-Gal4 significantly (p<10−3) increased period to 25.93h, but the period was quite variable and most of these flies were arrhythmic (Table 2). When pdf-Gal4 was used to overexpress Cipc the period was also significantly (p<10−3) lengthened to 24.70h, but the period was more stable and most of the flies were rhythmic, albeit with a reduced amplitude (Table 2). The period lengthening due to Cipc overexpression is consistent with CIPC repression of CLK-CYC transcription, as shown previously in S2 cells 12.

Loss of Cipc function restores the period of activity rhythms in cwo5073 flies

If the long period observed in cwo5073 flies is caused by increased levels of Cipc expression, we expect that reducing or eliminating Cipc expression in cwo5073 flies will restore the circadian period to that of w1118 control animals. To test this possibility, we generated cwo5073 flies in which Cipc expression was either knocked down by tim-Gal4 driven UAS-CipcRNAi#1 or eliminated by the CipcΔ64 mutant. RNAi knockdown of Cipc in clock cells of cwo5073 flies shortened period length by >1.5h to 24.27h (Table 3). Likewise, CipcΔ64 cwo5073 double mutants also shorten circadian period length by ~2.0h to 24.27h (Table 3). Given that tim-Gal4 driven Cipc RNAi and homozygous CipcΔ64 mutants only shorten period by ~0.6h in w1118 flies (Table 2), the reduction of period in cwo5073 flies by >1.5h is not simply additive and indicates a genetic interaction between Cipc and cwo. These results suggest that the period lengthening in cwo5073 flies is largely due to increased Cipc expression, thus under normal circumstances cwo inhibits Cipc repression to promote CLK-CYC activation and maintain a ~24h period. However, given that neither tim-Gal4 driven Cipc RNAi and homozygous CipcΔ64 mutants completely rescue cwo5073 period to that of w1118 control flies (Table 3), cwo likely controls other genes that contribute to period shortening.

Table 3.

Activity rhythms of cwo5073 flies having reduced/eliminated Cipc expression.

| Genotype | Total | % Rhythmic | Period ± s.e.m. | Strength ± s.e.m. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| W 1118 | 51 | 98.04 | 23.55 ± 0.04 | 233.63 ± 21.80 |

| W1118; +/tim-Gal4; cwo5073 | 32 | 90.62 | 26.99 ± 0.11 | 134.53 ± 25.26 |

| W1118; U-CpicRNAi#1 /tim-Gal4; cwo5073 a | 32 | 81.25 | 24.27 ± 0.05 1,2,3 | 136.39 ± 24.24 |

| W1118; UAS-CpicRNAi#1/+; cwo5073 a | 32 | 90.62 | 25.79 ± 0.14 | 109.45 ± 19.62 |

| W1118; +/+; cwo5073 | 41 | 80.48 | 26.30 ± 0.21 | 124.17 ± 23.57 |

| W1118; CpicΔ64 cwo5073 | 27 | 62.96 | 24.27 ± 0.22 4,5 | 43.82 ± 10.07 6 |

Activity rnytnm period in constant darkness is given in nours ± standard error of tne mean (s.e.m.).

UAS-CpicRNAi#1, VDRC # KK107220.

Period significantly (p<10−4) shorter than W1118; tim-Gal4/+; cwo5073 control flies.

Period is significantly (p<10−4) shorter than +; UAS-CpicRNAi#1/+; cwo5073 control flies.

Period significantly (p<10−4) longer than W1118 controls.

Period significantly (p<10−4) shorter than W1118; +/+; cwo5073 control flies.

Period significantly (p<10−3) longer than W1118 flies. Power significantly (p<0.05) lower than W1118; +/+; cwo5073 controls.

CIPC represses CLK-CYC transcription in a CWO-dependent manner in vivo

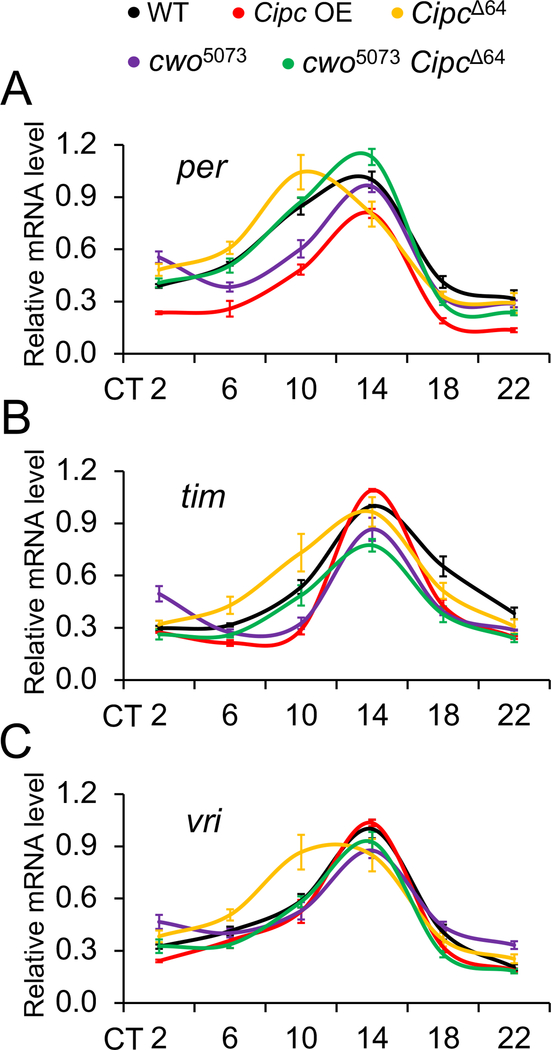

Our behavioral analysis suggests that 1) Cipc represses CLK-CYC transcription and 2) cwo inhibits Cipc repression to activate CLK-CYC transcription. To determine whether Cipc represses CLK-CYC transcription, quantitative RT-PCR was used to test whether expression of CLK-CYC target genes per, tim and vri is increased in CipcΔ64 mutant flies and decreased in tim-Gal4 driven Cipc overexpression flies compared to wild-type. The levels of per, tim and vri mRNAs are higher (per, ns; tim, p<0.01 at ZT10; vri, p<0.0001 at ZT10) during the subjective day (Figure 4). Consequently, per and vri mRNAs peak earlier in CipcΔ64 flies than in wild-type flies (Figure 4), consistent with their short period rhythms (Table 1). In contrast, the levels of per and tim mRNAs are lower in Cipc overexpression flies than wild-type flies (per, p<0.03 at CT6-CT22; tim, p<0.02 at CT10 and ZT18), but vri mRNA levels are not significantly different in Cipc overexpression flies than in wild-type flies (Figure 4). These data suggest that Cipc represses CLK-CYC transcription, but such repression is not uniform; per expression is the most impacted, followed by tim and then vri.

Figure 4. Levels of per, tim and vri mRNAs in CipcΔ64, Cipc overexpression, cwo5073 and CipcΔ64 cwo5073 flies.

Flies were entrained in LD, collected on DD day 1 at the indicated times and mRNA levels were measured from fly heads via quantitative RT-PCR. (A) per mRNA levels were measured in w1118 (WT, black), CipcΔ64 (yellow), tim-Gal4 driven UAS-Cipc (Cipc OE, red), cwo5073 (purple) and CipcΔ64 cwo5073 (green) flies. per mRNA was significantly lower (p<0.03) in CipcΔ64 than WT at CT14, significantly lower (p<0.03) in Cipc OE than WT at CT6-CT22, significantly higher (p<0.03) in cwo5073 than WT at CT2, significantly lower (p<0.0001) in cwo5073 than WT at CT10, significantly higher (p<0.04) in CipcΔ64 cwo5073 than WT at CT14, significantly higher (p<0.05) in cwo5073 than CipcΔ64 cwo5073 at CT2 and significantly lower (p<0.03) in cwo5073 than CipcΔ64 cwo5073 at CT10 and CT14. (B) tim mRNA levels were measured in the genotypes listed in A. tim mRNA was significantly higher (p<0.01) in CipcΔ64 than WT at CT10, significantly lower (p<0.02) in Cipc OE than WT at CT10 and CT18, significantly higher (p<0.03) in cwo5073 than WT at CT2, significantly lower (p<0.0001) in cwo5073 than WT at CT10 and CT18, significantly lower (p<0.04) in CipcΔ64 cwo5073 than WT at CT14, significantly higher (p<0.05) in cwo5073 than CipcΔ64 cwo5073 at CT2 and significantly lower (p<0.03) in cwo5073 than CipcΔ64 cwo5073 at CT10. (C) vri mRNA levels were measured in the genotypes listed in A. vri mRNA was significantly higher (p<0.01) in in CipcΔ64 than WT at CT10.

To determine whether cwo inhibits Cipc repression to activate CLK-CYC transcription, we tested whether low per, tim and vri mRNA levels in cwo5073 mutant flies were increased in CipcΔ64 cwo5073 double mutant flies. Consistent with previous studies, the levels of per and tim mRNAs were lower in cwo5073 flies than wild-type flies during the late day (per, p<0.001 at CT10; tim, p<0.02 at CT10), but higher during early day (per, p<0.03 at CT2; tim, p<0.05 at CT2) (Figure 4). The levels of vri trended lower in cwo5073 flies during the late day and early evening and higher in the early morning than wild-type flies, but not significantly so. As in wild-type flies, per and tim mRNA levels were higher in CipcΔ64 cwo5073 double mutants than in cwo5073 flies during the late day and/or early evening (per, p<0.03 at CT10 and CT14; tim, p<0.02 at CT10) and lower during early day (per, p<0.05 at CT2; tim, p<0.02 at CT2) (Figure 4). However, the levels of vri mRNA in CipcΔ64 cwo5073 double mutants were not significantly different than in cwo5073 flies at any time during the circadian cycle (Figure 4). These results suggest that cwo inhibits Cipc repression to activate CLK-CYC transcription, though the effects of removing Cipc repression in cwo5073 flies are again not uniform; per is strongly upregulated, tim is upregulated to a lesser extent, and vri expression is not altered.

Discussion

To understand how cwo functions to activate CLK-CYC transcription, we used ChIP-seq and RNA-seq analyses to identify genes directly targeted by CWO and upregulated in cwo5073 mutant flies. ChIP-seq identified 492 CWO target genes, including the core clock genes, per, tim, vri and Pdp1. Consensus CACGTG E-boxes are enriched in CWO binding sites, consistent with previous ChIP-seq analysis that identified 1103 CWO target genes in S2 cells 8. However, of these 1103 CWO target genes only 154 overlap with the 492 identified in flies. This relatively poor overlap may stem from differences in cell type (clock cells in flies and non-clock S2 cells), CWO expression levels (overexpression of CWO in S2 cells), use of epitope tagged CWO-HA that didn’t fully rescue cwo5073 rhythms (Table S1) and/or the different techniques used to assess CWO binding (ChIP microarray in S2 cells and ChIP-seq in flies). Our ChIP-seq analysis of CLK binding identified 113 genes, which is much fewer than the ~1500 CLK target genes identified via ChIP microarray 20. This disparity is likely due to differences in these techniques as well as the different antibodies and wash conditions used 20,22. Despite the lower number of CLK target genes identified by ChIP-seq, about 50% of CLK target genes are bound by CWO (Figure 1C), which suggests that competition for E-box binding between CLK-CYC and CWO is a prominent pattern for regulating circadian transcription. Only ~11% of CWO targets are bound by CLK (Figure 1C), where CWO binding alone or strong CWO binding paired with relatively weak CLK binding results in transcriptional repression at all times during a diurnal cycle (Figures 2, 3), consistent with CWO function as a transcriptional repressor 6–10. Rhythmic CLK-CYC activation at some target sites and CWO repression at other sites is likely due to their preference for binding CACGTG E-boxes with different flanking nucleotides (Figure 1B) 8,15. However, there is some flexibility in binding that allows CWO to bind strong CLK-CYC sites, but only if CLK-CYC is either complexed with PER-TIM or absent altogether 10.

Since CWO is a transcriptional repressor, we hypothesized that CWO-dependent repression of a CLK-CYC repressor would activate CLK-CYC transcription. Thus, we sought to identify genes that are upregulated in cwo5073 flies that repress CLK-CYC transcription. RNA-seq analysis of wild-type and cwo5073 mutant flies identified 401 genes that are upregulated in cwo5073 flies (Table S3). Of these genes, only eight were expressed in clock brain neurons and are directly bound by CWO (Table 1). Bioinformatic analysis of these genes revealed that only CG31324 is predicted to regulate transcription and is conserved in mammals. CG31324 is a putative ortholog of mammalian Cipc 12,19, which functions to repress CLOCK-BMAL1 transcription 11. Previous analysis of CIPC protein in mammals not only showed that its conserved CiPC domain interacts with the CLOCK exon 19 domain to repress transcription 11,12, but showed that the CiPC domain of Drosophila Cipc also interacts with the CLK exon 19 analogous region to repress CLK-CYC transcription in S2 cells 12.

In flies, increased CLK-CYC transcription shortens circadian period and decreased CLK-CYC transcription lengthens or abolishes circadian period 21,23,24. Since Drosophila Cipc functions to repress CLK-CYC transcription in S2 cells, eliminating Cipc expression should shorten period due to increased CLK-CYC transcription and increasing Cipc expression should lengthen period due to decreased CLK-CYC transcription. Indeed, Cipc null mutants shortened circadian period by ~0.6h and two of three Cipc RNAi lines also shortened period (Table 2) 19, whereas Cipc overexpression lengthened circadian period by ~2h and increased arrhythmicity (Table 2). These results suggest that Cipc represses CLK-CYC transcription in vivo, consistent with previous transcription assays in S2 cells 12. To test whether Cipc represses CLK-CYC transcription in vivo, we measured the levels of per, tim and vri mRNAs in CipcΔ64 and tim-Gal4 driven Cipc overexpression flies. Our results support repression of CLK-CYC transcription by CIPC, but the extent of repression is variable, with per being the most strongly repressed, followed by tim, and vri showing weak or no repression. Although the molecular basis of this variability is not known, it is not surprising given that cwo mutants have a variable impact on the peak levels of clock genes activated by CLK-CYC 6,7,9 (Figure 4). In addition, the levels of per mRNA are the most strongly reduced by Cipc, which may be consequential as per is a limiting negative feedback regulator that increases or decreases circadian period when its expression levels/gene copy numbers are higher or lower, respectively 25–27. Taken as a whole, our data show that Drosophila CIPC represses CLK-CYC transcription in vivo.

In cwo5073 mutants Cipc expression is upregulated (Figure 3, Table 1), thus increased CLK-CYC repression by CIPC could account for the ~26h rhythms in cwo5073 flies. We show that reducing Cipc expression in cwo5073 flies via clock cell-specific RNAi or eliminating Cipc function in cwo5073 flies (e.g. CipcΔ64 cwo5073 double mutants) shortens rhythms by >1.5h to ~24.3h (Table 3), which indicates that period lengthening in cwo5073 flies is primarily due to increased Cipc levels. Since the period of Cipc RNAi knockdown in cwo5073 flies and CipcΔ64, cwo5073 double mutants was longer than the ~23.6h period of w1118 controls, other cwo-dependent factors likely contribute to period lengthening. Two known clock factors that are upregulated in cwo5073 flies, circadian trip (ctrip) and domino (dom), lengthen period when their expression is reduced rather than increased 28,29, indicating that they don’t repress CLK-CYC transcription or activity. Other transcription regulators that are upregulated in cwo5073 flies, MESR3, hairy (h), gemini (gem) and grappa (gpp), are of interest as they could contribute to CLK-CYC repression.

If decreased expression of CLK-CYC target genes in cwo5073 flies is due to increased Cipc expression, then eliminating Cipc expression in CipcΔ64 cwo5073 flies should restore higher levels of CLK-CYC target gene expression. We found that rescuing per, tim and vri expression in cwo5073 flies depends on the extent to which their expression is decreased; per mRNA levels are strongly reduced at CT6 and CT10 in cwo5073 flies and restored to wild-type levels at these times in CipcΔ64 cwo5073 double mutant flies, tim mRNA levels are lower from CT10 to CT22 in cwo5073 flies and restored to wild-type levels at CT6, while vri mRNA levels are not reduced in cwo5073 flies and thus not rescued in CipcΔ64 cwo5073 flies (Figure 4). These results support a model in which cwo inhibits Cipc repression of CLK-CYC transcription, but not uniformly for the CLK-CYC targets tested as per expression is most impacted, tim expression is less impacted, and vri expression is impacted little if at all.

Like other CLK-CYC repressors in flies, Cipc mRNA is rhythmically expressed with a peak around ZT14 16,19,20 (Figure 3, Table S3). This rhythm in Cipc mRNA expression is presumably imposed by rhythmic CLK-CYC binding at the Cipc locus that also peaks at ~ZT14 20. Although no antibodies against Drosophila CIPC are available, we expect CIPC activity to coincide with PER cycling to repress CLK-CYC. If so, CIPC presumably reinforces its own rhythmic expression and that of other CLK-CYC regulated genes. We and others previously showed that CWO represses CLK-CYC transcription by binding E-boxes to maintain PER-TIM bound CLK-CYC off DNA 6–10. CWO also downregulates Cipc expression as loss of cwo increases Cipc mRNA by ~50% (Figure 3, Table 1). The increased Cipc expression in cwo5073 flies inhibits CLK-CYC dependent transcription of per and tim 6–9, thereby weakening PER-TIM repression and lengthening period. This data indicates that CWO not only directly inhibits CLK-CYC transcription via E-box binding, but indirectly activates CLK-CYC transcription by repressing Cipc, thus releasing CIPC inhibition of CLK-CYC transcription. Given that CipcΔ64 doesn’t completely rescue cwo5073 molecular and behavioral rhythms, CWO also activates CLK-CYC transcription independent of Cipc to some extent.

Given that CWO, CIPC and CLOCK-BMAL1 have conserved functional domains between insects and mammals, a similar regulatory mechanism may operate in mammals. In mice, CIPC protein cycles in phase with the key CLOCK-BMAL1 repressors mPER1 and mPER2 11,30,31. Although RNAi knockdown of Cipc in NIH3T3 fibroblasts shortens circadian period, a homozygous Cipc−/− null mutation alters neither activity rhythms nor Per2-luc rhythms in tissue explants 32. Mammalian CWO orthologs DEC1 and DEC2 repress CLOCK-BMAL1 transcription by competing for E-box binding 33. In Dec1−/− Dec2−/− double mutant mice circadian period is lengthened by ~0.5h 34, but the impact on clock gene expression varies depending on tissue; Per2 mRNA levels are decreased in pacemaker neurons in the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) and Per1 and Per2 mRNA levels are increased in peripheral clock tissues such as the cerebral cortex and liver 34. Interestingly, in Cipc−/− livers the only clock gene whose expression is altered is Per1, though its levels are decreased 32. Since Dec1−/− Dec2−/− double mutants differentially impact clock gene expression in the SCN versus peripheral tissues it is possible that Cipc will also have opposing effects, though clock gene expression in Cipc−/− mutant mice hasn’t been measured in the SCN. If DEC1 and DEC2 repress transcription, their loss in Dec1−/− Dec2−/− mice would increase CLOCK-BMAL1 transcription, which is the case in peripheral tissues but not the SCN. Consequently, the Dec genes appear to activate CLOCK-BMAL1 transcription in the SCN, analogous to the ability of CWO to activate CLK-CYC in flies. Since Cipc is expressed in the mouse SCN 11, it is conceivable that the Dec genes could activate CLOCK-BMAL1 in pacemaker neurons by repressing Cipc. Determining whether the Dec genes operate in concert with Cipc in the SCN to promote CLOCK-BMAL1 transcription awaits future study.

STAR METHODS

RESOURCE AVAILABILITY

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents not made available through national stock centers should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Paul Hardin (phardin@bio.tamu.edu).

Materials availability

All unique reagents generated in this study are available from the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center or the Lead Contact without restriction.

Data and code availability

The ChIP-seq and RNA-seq datasets generated in this study are available at the Gene Expression Omnibus Repository and are publicly available as of the date of publication.

ChIP-seq and RNA-seq data accession numbers are listed in the key resources table.

This paper does not report original code.

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

KEY RESOURCES TABLE.

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Rabbit anti-HA | Abcam | ab128131; RRID: AB_11143947 |

| Mouse anti-β ACTIN | Abcam | ab8224; RRID: AB_449644 |

| Chemicals, peptides and recombinant proteins | ||

| High Fidelity DNA polymerase | Invitrogen | Cat# 11304011 |

| TRIzol reagent | Invitrogen | Cat# 15596026 |

| TURBO DNAse | Thermo Scientific | Cat# AM2238 |

| NEBNext® Ultra™ II RNA Library Prep Kit | New England Biolabs | Cat# E7760S |

| NEBNext® Ultra™ DNA Library Prep Kit | New England Biolabs | Cat# E7370S |

| NEBNext Poly(A) mRNA Magnetic Isolation Module | New England Biolabs | Cat# E7490S |

| SuperScript™ II Reverse Transcriptase | Invitrogen | Cat# 18064014 |

| 2X Universal SYBR Green Fast qPCR Mix | ABclonal | Cat# RK21203 |

| Bacterial and Virus Strains | ||

| SW102 cells | Biological Resources Branch, NCI-Frederick | Bacteria set |

| EL350 cells | Biological Resources Branch, NCI-Frederick | Bacteria set |

| EPI300 cells | Epicenter | Cat#EC300110 |

| Deposited Data | ||

| ChIP-Seq | This paper | GSE165044 |

| RNA-Seq | This paper | GSE165044 |

| Experimental Models: Organisms/Strains | ||

| D. mel: CipcΔ64, CipcΔ22, CipcΔ11, cwo-HA | This Paper | N/A |

| D. mel: CG31324 KK RNAi | VDRC | #107220 |

| D. melr: CG31324 RNAi | BDSC | #28774 |

| D. mel: UAS-CG31324 | FLYORF | #F004315 |

| D. mel: cwo5073 | 6. 7 | N/A |

| D. mel: tim-Gal4 | 35 | N/A |

| D. mel: pdf-Gal4 | 36 | N/A |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

|

cwo-MyC-3xHA-L primer (5’-GCAGCGGTGGCTAAGGCCAAAC TGGAGCAGGCCATGAACCAGAGCTGGGAACAAAAACTTAT TTCTGAAGAAGATCTGAATAGCGCCGTCGACTACCCATACG ACGTACCAGATTACGCTTACCCATACGACGTACCAGATTAC GCTTACCCATACGACGTACCAGATTACGCTTAGGCAGCCCA ATTCCGATCATATTC-3’) |

This Paper | N/A |

|

cwo-R primer (5’-TACTGAGGTAGTGTTGTTCCATCTGTCGAC CCATTGCATTGCGATTGCTTTGCTGGATCCCCTCGAGGGAC CTAT-3’) |

This Paper | N/A |

| Cipc translation start gRNA sense (5’-CGCGAAACGCGGCGACATCA-3’) | This Paper | N/A |

| Cipc translation start gRNA antisense (5’-TGATGTCGCCGCGTTTCGCG-3’) | This Paper | N/A |

| Cipc intron 1 splice donor gRNA sense (5’-TGCCGCCACACAAGCTAGTT-3’) | This Paper | N/A |

| Cipc intron 1 splice donor gRNA antisense (5’-AACTAGCTTGTGTGGCGGCA-3’) | This Paper | N/A |

| Cipc mutant screen forward (5’-GCTCAAAGTTAAACGAACCCAAAG-3’) | This Paper | N/A |

| Cipc mutant screen reverse (5’-GCAAGCTATTGGCACTGAACAA-3’) | This Paper | N/A |

| rp49 qPCR Forward (5’-CGATATGCTAAGCTGTCGCACA-3’) | This Paper | N/A |

| rp49 qPCR Reverse (5’-GGCATCAGATACTGTCCCTTGAA-3’) | This Paper | N/A |

| per qPCR Forward (5’-GCAGCCTAATCGCAGCCTAATC-3’) | This Paper | N/A |

| per qPCR Reverse (5’-CCTTGGTGTTGTGTGTGGACTC-3’) | This Paper | N/A |

| tim qPCR Forward (5’-AGTTGGTCATGCGCAGCAAATG-3’) | . 9 | N/A |

| tim qPCR Reverse (5’-GGCTCAAAGTGGTTGTGGGATTA-3’) | This Paper | N/A |

| vri qPCR Forward (5’-GCGAACAGGTGCTGAGTAACA-3’) | This Paper | N/A |

| vri qPCR Reverse (5’-CATTGCCATTGGGTCCGTAGAT-3’) | This Paper | N/A |

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| PACMAN clone CH321–18B09 | BACPAC Resources | CH321–18B09 |

| Software and Algorithms | ||

| ClockLab | Actimetrics | N/A |

| GraphPad Prism 5 | GraphPad Software | https://www.graphpad.com |

| Excel | Microsoft | Version 16 |

| Bowtie2 | 41 | http://bowtie-bio.sourceforge.net/bowtie2/index.shtml;RRID:SCR_016368 |

| Samtools | 42 | http://samtools.sourceforge.net/;RRID:SCR_002105 |

| HOMER | 45 | http://homer.ucsd.edu/homer/;RRID:SCR_010881 |

| Integrated Genomics Viewer | 46 | http://software.broadinstitute.org/software/igv/;RRID:SCR_011793 |

| STAR aligner | 47 | Version 2.6.1d |

| StringTie | 48 | Version 1.3.5 |

| RStudio Version 1.2.5033 | RStudio | https://rstudio.com/;RRID:SCR_000432 |

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

The following fly strains were used in this study: w1118 (control strain having a wild-type clock), cwo5073 6,7, tim-Gal4 35, pdf-Gal4 36, CG31324 RNAi KK107220 (Vienna Drosophila RNAi Center, VDRC), CG31324 RNAi #28774 (Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center, BDSC), CG31324 FLYORF strain #F004315 37.

METHOD DETAILS

Transgenic fly generation

A cwo transgene containing c-Myc and 3xHA epitope tags at the C-terminus (cwo-HA) was constructed via recombineering. High Fidelity DNA polymerase (Invitrogen) was used to amplify the Frt-ampicillin-Frt (Frt-Amp-Frt) cassette from FRT-gb2-amp-FRT plasmid (Gene Bridges) using the cwo-MyC-3xHA-L primer (5’ gcagcggtggctaaggccaaactggagcaggccatgaaccagagctggGAACAAAAACTTATTTCTGAAGAAGATCTGaatagcgccgtcgacTACCCATACGACGTACCAGATTACGCTTACCCATACGACGTACCAGATTACGCTTACCCATACGACGTACCAGATTACGCTtagGCAGCCCAATTCCGATCATATTC 3’) containing the last 48 nucleotides (nts) of cwo coding sequence upstream of the stop codon (lower case), 30 nts of the c-Myc sequence (upper case), 15 nts of the linker sequence (lower case italics), 81 nts of the 3xHA sequence (upper case underlined), a stop codon (lower case bold) and 23 nts of the Frt-Amp-Frt cassette (lowercase italics), and the cwo-R primer (5’ tactgaggtagtgttgttccatctgtcgacccattgcattgcgattgctttgcTGGATCCCCTCGAGGGACCTAT 3’) containing 53 nts of cwo sequence immediately downstream of the stop codon (lower case) and 22 nts from the 3’ end of Frt-Amp-Frt cassette (upper case italics). This PCR reaction was run at melting temperature (Tm) of 56°C for 35 cycles, treated with Dpnl enzyme and purified. This fragment was used to transform SW102 cells harboring the P[acman] BAC clone CH321–18B09 (BACPAC Resources Center), which contains the 12.494 kb genomic region of cwo. Recombinants containing the Frt-Amp-Frt cassette inserted into cwo were selected on plates containing ampicillin. The ampicillin gene was removed by inducing recombination at the Frt sites 38, resulting in a chloramphenicol resistant cwo-Myc-HA P[acman] plasmid. The cwo-Myc-HA plasmid was sequenced to confirm in-frame fusion of the C-terminal cMyc-3xHA tag. The cwo-HA transgene was then inserted into attP40 on chromosome 2 via PhiC31-mediated transgenesis 39.

Western blotting

Flies were entrained in 12-h light/12-h dark (LD) cycles for at least 3 days, collected at different times during a diurnal cycle, and frozen at −80°C. Fly heads were isolated and homogenized in radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer (20 mM Tris at pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.05 mM EGTA, 10% glycerol, 1% Triton X-100, 0.4% sodium deoxycholate) containing 0.5 mM PMSF (phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride), 10 μg/ml aprotinin, 10 μg/ml leupeptin, 2 μg/ml pepstatin A, 1 mM Na3VO4, and 1 mM NaF. This homogenate was sonicated for 10s 3–5 times using a Misonix XL2000 model sonicator at a setting of 3 and then centrifuged at 20,000 g for 10 min. The supernatant was collected as RIPA S extract, and protein concentration was determined by the Bradford assay. Equal amounts of RIPA S extract were separated by PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose, and probed with rabbit anti-HA (Abcam; 1:20,000) or mouse anti-beta-actin (Abcam; 1:20,000). Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat secondary antibodies (Sigma) against rabbit and mouse were diluted 1:5,000. Immunoblots were visualized using ECL plus (GE) reagent.

ChIP-seq library preparation

w1118 and cwo-HA; cwo5073 flies were entrained for 3 days in LD at 25oC, collected at ZT2 and ZT14, frozen on dry ice and heads were isolated as described 40. ChIP was performed with HA antibody (for CWO-HA) and CLK antibody as previously described 10,22. DNA sequencing library construction was performed using NEBNext® Ultra™ DNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina (New England Biolabs) following manufacturer’s instructions for end repair, adaptor ligation and size selection. The DNA products were then used as template for PCR amplification for 12 cycles following the PCR conditions in the manufacturer’s instructions, and after purification the eluted DNA targets were sent for sequencing on an Illumina HiSeq2500 system using 50bp single-end reads at the Texas A&M AgriLife Genomics and Bioinformatics Facility.

ChIP-seq mapping and peak finding

Sequences from the different libraries (fastq format) were first mapped to the Drosophila genome (version dm3) using bowtie2 41. Only those reads that mapped uniquely to the Drosophila genome were sorted using the samtools suite (http://samtools.sourceforge.net/) 42, and used for further analysis as described 43,44. Peak calling was performed using the findPeaks program from the HOMER software suite (http://homer.ucsd.edu) 45. Briefly, findPeaks loads tags from each chromosome, adjusting them to the center of their fragments, or by half of the estimated fragment length in the 3’ direction. It then scans the entire genome looking for fixed width clusters with the highest density of tags. As clusters are found, the regions immediately adjacent are excluded to ensure there are no “piggyback peaks” that feed off the signal of large peaks. By default, peaks must be greater than 2x the peak width apart from one another. This continues until all tags have been assigned to clusters. Visualization of the ChIP-seq signal was performed using the bw file and the Integrated Genomics Viewer software 46.

RNA-seq library preparation and analysis

w1118 and cwo5073 mutant flies were entrained for 3 days in LD at 25oC, collected every 4 hours during LD, frozen on dry ice and heads were isolated as described 40. Total RNA was isolated using Trizol (Invitrogen), treated with a TURBO™ DNase (Thermo Fisher Scientific), precipitated and purified with Lithium Chloride (Thermo Fisher Scientific) following the manufacture’s instructions. 1.0 μg of total RNA was used to isolate mRNA using the NEBNext Poly(A) mRNA Magnetic Isolation Module (New England Biolabs), which was used for RNA library construction with the NEBNext® Ultra™ II Directional RNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina (New England Biolabs). The resulting cDNA products were then used as template for PCR amplification for 12 cycles following the PCR conditions in the manufacturer’s instructions, and after purification the eluted DNA fragments were sent for sequencing. RNA (cDNA) libraries were mixed and multiplexed at the same equimolar concentrations and sequenced on an Illumina Next Seq 500 system using 75bp single end reads at the Texas A&M AgriLife Genomics and Bioinformatics Facility. Sequenced reads were mapped to the Drosophila genome (dm6) using STAR aligner version 2.6.1d 47. Uniquely mapped sequences from the STAR output files (bam format) were assembled using StringTie as described 48.

Quantitative RT-PCR

RNA extraction and quantitative RT-PCR were performed as described 10, except flies were entrained in LD and collected during the first day of DD. Rp49 mRNA was used to normalize (ΔCt) the total amount of mRNA in each sample. The ΔCt values for each timepoint was normalized (ΔΔCt) to the peak value for each transcript in wild-type at CT14 to generate the relative expression values (2−ΔΔCt) for each gene. Primers used to amplify each transcript are shown in the Key Resource Table.

Drosophila activity monitoring

One to three-day old male flies were entrained for three days in LD and transferred to DD for seven days at 25°C. Locomotor activity was monitored using the Drosophila Activity Monitor (DAM) system (Trikinetics). Each experiment was repeated at least twice for all genotypes.

Generation of Drosophila Cipc mutants

The CRISPR/Cas9 system was used to generate Drosophila Cipc mutants 49. Guide RNAs (gRNAs) that target sites near the Cipc translation start (Cipc translation start gRNA sense, 5’ CGCGAAACGCGGCGACATCA 3’) and intron 1 splice donor sequences (Cipc translation start gRNA antisense, 5’ TGCCGCCACACAAGCTAGTT 3’) were designed using the CRISPR database (https://flycrispr.org/protocols/gRNA/). Complementary oligonucleotides corresponding to each gRNA were annealed and inserted into the U6b-sgRNA-short vector for expression in Drosophila 50. The resulting Cipc gRNA plasmids were sequenced to confirm the integrity of the gRNA inserts and sent for injection into y1 M{vas-Cas9} ZH2A w1118 embryos that express Cas9 in the germ line (Best Gene Inc.). Injected embryos that survived to adulthood were crossed with w1118;+;TM2/TM6B, and once progeny were observed, injected adults were screened for deletions between or flanking the gRNAs. To screen for deletions, a ~600bp DNA fragment containing the gRNA binding sites was amplified using the Cipc mutant screen forward 5’ GCTCAAAGTTAAACGAACCCAAAG 3’ and the Cipc mutant screen reverse 5’ GCAAGCTATTGGCACTGAACAA 3’ primers via PCR, and sequenced. The three largest deletions that created a frameshift, CipcΔ64, CipcΔ22 and CipcΔ11 were kept for further analysis.

Quantification and Statistical Analysis

Each peak identified using HOMER is assigned a peak score, which is a relative measure of binding strength. Significant ChIP-seq peaks were computationally assigned to a gene. The following criteria were used to assign significant Chip-seq peaks: FDR rate threshold = 0.001, p-value over local region required = 1.00e-04, fold over local region required = 4.00. CWO and CLK binding at ZT2 and ZT14 is reported from highest to lowest peak score for all binding sites (DataS1E–H) or for binding sites that are associated with genes (Data S1A–D), which excludes binding in intergenic regions (see Figure 1). Analysis of RNA-seq data was carried out using RStudio (https://rstudio.com/). Differential expression across all time points was conducted using DESeq2 51. Significant differentially expressed genes were selected using the following criteria: an adjusted p-value ≤ 0.05 and a fold-change of ≥ 1.5 for upregulated genes or ≤ 0.5 for down-regulated genes. To estimate rhythmicity of transcripts, the function -B in StringTie was used to create Ballgown input table files 52. The Ballgown object had a total of 16,727 genes, which were filtered to remove low abundance genes as described 48. A matrix of 8489 genes was created with normalized FPKM values using the function gexp and used to estimate rhythmic genes with programs RAIN 53 and MetaCycle 54. p-values of both programs were combined as described 55 and only genes with an adjusted p-value ≤ 0.05 and fold-change ≥ 1.3 were considered rhythmic. GO analysis of differentially expressed genes identified by DESeq2 was performed using Metascape (http://pantherdb.org/). For quantitative RT-PCR experiments, differences in mRNA levels between genotypes at a specific timepoint were analyzed using 2-Way ANOVA followed by a Bonferroni post-hoc test. P-values from post-hoc tests were used to determine whether differences between genotypes were significant at a specific CT timepoint. Statistical analyses were carried out using GraphPad Prism Software version 5.3 (Prism, La Jolla, CA). To analyze behavioral rhythms, data from each fly was used to determine the period length and strength of rhythmicity using the ClockLab (Actimetrics) software as previously described 56.

Supplementary Material

Data S1. ChIP-seq analysis of CWO and CLK binding targets at ZT2 and ZT14. Related to Figure 1 and STAR Methods. CWO and CLK binding targets identified at ZT2 and ZT14 are listed from highest to lowest peak score. A) Genes targeted by CWO at ZT2 after removing binding peaks mapping to intergenic regions. B) Genes targeted by CWO at ZT14 after removing binding peaks mapping to intergenic regions. C) Genes targeted by CLK at ZT2 after removing binding peaks mapping to intergenic regions. D) Genes targeted by CLK at ZT14 after removing binding peaks mapping to intergenic regions. E) Total CWO binding peaks at ZT2. F) Total CWO binding peaks at ZT14. G) Total CLK binding peaks at ZT2. H) Total CLK binding peaks at ZT14.

Table S3. Up-regulated genes in heads of w1118 control and cwo5073 mutant flies during LD cycles. Related to Figure 3. RNA-seq data collected in LD cycles was analyzed to identify genes that were significantly up-regulated (see STAR Methods). Column A, list of significantly up-regulated genes sorted from highest to lowest fold-change. Columns B-M, values of gene expression in read counts for w1118 (WT) fly heads at Zeitgeber Time 02 (ZT02), ZT06, ZT10, ZT14, ZT18 and ZT22 for two independent replicates R1 and R2. Columns N-Y, values of gene expression in read counts for cwo5073 (CWO) fly heads at ZT02, ZT06, ZT10, ZT 14, ZT18 and ZT22 for two independent replicates R1 and R2. Column Z, average read count for all WT samples. Column AA, average read count for all CWO samples. Column AB, linear fold change calculated from Log 2-Fold change values that were generated using DESeq2. Column AC, adjusted p-value generated using DESeq2. Column AD, the gene expression peak is shown in ZT for rhythmic genes based on two RNA-seq replicates. Non-rhythmic genes are shown as dashes (--).

Highlights.

CWO repress transcription of the putative Drosophila ortholog of mouse Cipc

Altering Cipc expression changes period length and rescues cwo mutant rhythms

CIPC represses CLK-CYC transcription where per is impacted more than tim and vri

CWO indirectly activates CLK-CLK transcription by repressing Cipc

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Jerome Menet for his help analyzing ChIP-seq data and Mr. Aldrin Lugena for his help analyzing RNA-seq data. This work was supported by NIH grant GM124617 to CM and PEH.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Supplemental Information

Figures S1, S2, S3, S4 and S5 are included in the main supplemental data PDF file. Tables S1 and S2 are included in the main supplemental data PDF file. Table S3, Up-regulated genes in heads of w1118 control and cwo5073 mutant flies during LD cycles, is included as an Excel file. Data S1, ChIP-seq analysis of CWO and CLK binding targets at ZT2 and ZT14, is included as an Excel file.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Patke A, Young MW, and Axelrod S (2020). Molecular mechanisms and physiological importance of circadian rhythms. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 21, 67–84. 10.1038/s41580-019-0179-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Takahashi JS (2017). Transcriptional architecture of the mammalian circadian clock. Nat Rev Genet 18, 164–179. 10.1038/nrg.2016.150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hardin PE (2011). Molecular genetic analysis of circadian timekeeping in Drosophila. Adv Genet 74, 141–173. 10.1016/B978-0-12-387690-4.00005-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cyran SA, Buchsbaum AM, Reddy KL, Lin MC, Glossop NR, Hardin PE, Young MW, Storti RV, and Blau J (2003). vrille, Pdp1, and dClock form a second feedback loop in the Drosophila circadian clock. Cell 112, 329–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Glossop NR, Houl JH, Zheng H, Ng FS, Dudek SM, and Hardin PE (2003). VRILLE feeds back to control circadian transcription of Clock in the Drosophila circadian oscillator. Neuron 37, 249–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kadener S, Stoleru D, McDonald M, Nawathean P, and Rosbash M (2007). Clockwork Orange is a transcriptional repressor and a new Drosophila circadian pacemaker component. Genes Dev 21, 1675–1686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lim C, Chung BY, Pitman JL, McGill JJ, Pradhan S, Lee J, Keegan KP, Choe J, and Allada R (2007). Clockwork orange encodes a transcriptional repressor important for circadian-clock amplitude in Drosophila. Curr Biol 17, 1082–1089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Matsumoto A, Ukai-Tadenuma M, Yamada RG, Houl J, Uno KD, Kasukawa T, Dauwalder B, Itoh TQ, Takahashi K, Ueda R, et al. (2007). A functional genomics strategy reveals clockwork orange as a transcriptional regulator in the Drosophila circadian clock. Genes Dev 21, 1687–1700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Richier B, Michard-Vanhee C, Lamouroux A, Papin C, and Rouyer F (2008). The clockwork orange Drosophila protein functions as both an activator and a repressor of clock gene expression. J Biol Rhythms 23, 103–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhou J, Yu W, and Hardin PE (2016). CLOCKWORK ORANGE Enhances PERIOD Mediated Rhythms in Transcriptional Repression by Antagonizing E-box Binding by CLOCK-CYCLE. PLoS Genet 12, e1006430. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhao WN, Malinin N, Yang FC, Staknis D, Gekakis N, Maier B, Reischl S, Kramer A, and Weitz CJ (2007). CIPC is a mammalian circadian clock protein without invertebrate homologues. Nature cell biology 9, 268–275. 10.1038/ncb1539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hou Z, Su L, Pei J, Grishin NV, and Zhang H (2017). Crystal Structure of the CLOCK Transactivation Domain Exon19 in Complex with a Repressor. Structure 25, 1187–1194 e1183. 10.1016/j.str.2017.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Taylor P, and Hardin PE (2008). Rhythmic E-box binding by CLK-CYC controls daily cycles in per and tim transcription and chromatin modifications. Mol Cell Biol 28, 4642–4652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yu W, Zheng H, Houl JH, Dauwalder B, and Hardin PE (2006). PER-dependent rhythms in CLK phosphorylation and E-box binding regulate circadian transcription. Genes Dev 20, 723–733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Paquet ER, Rey G, and Naef F (2008). Modeling an evolutionary conserved circadian cis-element. PLoS Comput Biol 4, e38. 07-PLCB-RA-0532 [pii] 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0040038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kula-Eversole E, Nagoshi E, Shang Y, Rodriguez J, Allada R, and Rosbash M (2010). Surprising gene expression patterns within and between PDF-containing circadian neurons in Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107, 13497–13502. 10.1073/pnas.1002081107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Larkin A, Marygold SJ, Antonazzo G, Attrill H, Dos Santos G, Garapati PV, Goodman JL, Gramates LS, Millburn G, Strelets VB, et al. (2021). FlyBase: updates to the Drosophila melanogaster knowledge base. Nucleic Acids Res 49, D899–D907. 10.1093/nar/gkaa1026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Potter SC, Luciani A, Eddy SR, Park Y, Lopez R, and Finn RD (2018). HMMER web server: 2018 update. Nucleic Acids Res 46, W200–W204. 10.1093/nar/gky448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Litovchenko M, Meireles-Filho ACA, Frochaux MV, Bevers RPJ, Prunotto A, Anduaga AM, Hollis B, Gardeux V, Braman VS, Russeil JMC, et al. (2021). Extensive tissue-specific expression variation and novel regulators underlying circadian behavior. Sci Adv 7. 10.1126/sciadv.abc3781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abruzzi KC, Rodriguez J, Menet JS, Desrochers J, Zadina A, Luo W, Tkachev S, and Rosbash M (2011). Drosophila CLOCK target gene characterization: implications for circadian tissue-specific gene expression. Genes Dev 25, 2374–2386. 10.1101/gad.174110.11110.1101/gad.178079.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhao J, Kilman VL, Keegan KP, Peng Y, Emery P, Rosbash M, and Allada R (2003). Drosophila Clock Can Generate Ectopic Circadian Clocks. Cell 113, 755–766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhou J, Yu W, and Hardin PE (2015). ChIPping away at the Drosophila clock. Methods Enzymol 551, 323–347. 10.1016/bs.mie.2014.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Allada R, Kadener S, Nandakumar N, and Rosbash M (2003). A recessive mutant of Drosophila Clock reveals a role in circadian rhythm amplitude. Embo J 22, 3367–3375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Allada R, White NE, So WV, Hall JC, and Rosbash M (1998). A mutant Drosophila homolog of mammalian Clock disrupts circadian rhythms and transcription of period and timeless. Cell 93, 791–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baylies MK, Bargiello TA, Jackson FR, and Young MW (1987). Changes in abundance or structure of the per gene product can alter periodicity of the Drosophila clock. Nature 326, 390–392. 10.1038/326390a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hao H, Glossop NR, Lyons L, Qiu J, Morrish B, Cheng Y, Helfrich-Forster C, and Hardin P (1999). The 69 bp circadian regulatory sequence (CRS) mediates per-like developmental, spatial, and circadian expression and behavioral rescue in Drosophila. J Neurosci 19, 987–994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smith RF, and Konopka RJ (1981). Circadian clock phenotypes of chromosome aberrations with a breakpoint at the per locus. Molecular & general genetics : MGG 183, 243–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lamaze A, Lamouroux A, Vias C, Hung HC, Weber F, and Rouyer F (2011). The E3 ubiquitin ligase CTRIP controls CLOCK levels and PERIOD oscillations in Drosophila. EMBO reports 12, 549–557. 10.1038/embor.2011.64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu Z, Tabuloc CA, Xue Y, Cai Y, Mclntire P, Niu Y, Lam VH, Chiu JC, and Zhang Y (2019). Splice variants of DOMINO control Drosophila circadian behavior and pacemaker neuron maintenance. PLoS Genet 15, e1008474. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1008474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen R, Schirmer A, Lee Y, Lee H, Kumar V, Yoo SH, Takahashi JS, and Lee C (2009). Rhythmic PER abundance defines a critical nodal point for negative feedback within the circadian clock mechanism. Mol Cell 36, 417–430. 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee C, Etchegaray JP, Cagampang FR, Loudon AS, and Reppert SM (2001). Posttranslational mechanisms regulate the mammalian circadian clock. Cell 107, 855–867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Qu Z, Wang X, Liu D, Gao X, and Xu Y (2015). Inactivation of Cipc alters the expression of Per1 but not circadian rhythms in mice. Science China. Life sciences 58, 368–372. 10.1007/s11427-015-4828-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Honma S, Kawamoto T, Takagi Y, Fujimoto K, Sato F, Noshiro M, Kato Y, and Honma K (2002). Dec1 and Dec2 are regulators of the mammalian molecular clock. Nature 419, 841–844. 10.1038/nature01123nature01123 [pii]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rossner MJ, Oster H, Wichert SP, Reinecke L, Wehr MC, Reinecke J, Eichele G, Taneja R, and Nave KA (2008). Disturbed clockwork resetting in Sharp-1 and Sharp-2 single and double mutant mice. PLoS ONE 3, e2762. 10.1371/journal.pone.0002762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Emery P, So WV, Kaneko M, Hall JC, and Rosbash M (1998). CRY, a Drosophila clock and light-regulated cryptochrome, is a major contributor to circadian rhythm resetting and photosensitivity. Cell 95, 669–679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Park JH, Helfrich-Forster C, Lee G, Liu L, Rosbash M, and Hall JC (2000). Differential regulation of circadian pacemaker output by separate clock genes in Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 97, 3608–3613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bischof J, Bjorklund M, Furger E, Schertel C, Taipale J, and Basler K (2013). A versatile platform for creating a comprehensive UAS-ORFeome library in Drosophila. Development 140, 2434–2442. 10.1242/dev.088757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Venken KJ, Kasprowicz J, Kuenen S, Yan J, Hassan BA, and Verstreken P (2008). Recombineering-mediated tagging of Drosophila genomic constructs for in vivo localization and acute protein inactivation. Nucleic Acids Res 36, e114. 10.1093/nar/gkn486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Groth AC, Fish M, Nusse R, and Calos MP (2004). Construction of transgenic Drosophila by using the site-specific integrase from phage phiC31. Genetics 166, 1775–1782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Oliver D, and Phillips JP (1970). Technical note. Drosophila Information Service 45, 58. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Langmead B, and Salzberg SL (2012). Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat Methods 9, 357–359. 10.1038/nmeth.1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A, Fennell T, Ruan J, Homer N, Marth G, Abecasis G, Durbin R, and Genome Project Data Processing, S. (2009). The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 25, 2078–2079. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Menet JS, Pescatore S, and Rosbash M (2014). CLOCK:BMAL1 is a pioneer-like transcription factor. Genes Dev 28, 8–13. 10.1101/gad.228536.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Menet JS, Rodriguez J, Abruzzi KC, and Rosbash M (2012). Nascent-Seq reveals novel features of mouse circadian transcriptional regulation. eLife 1, e00011. 10.7554/eLife.00011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Heinz S, Benner C, Spann N, Bertolino E, Lin YC, Laslo P, Cheng JX, Murre C, Singh H, and Glass CK (2010). Simple combinations of lineage-determining transcription factors prime cis-regulatory elements required for macrophage and B cell identities. Mol Cell 38, 576–589. 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Robinson JT, Thorvaldsdottir H, Winckler W, Guttman M, Lander ES, Getz G, and Mesirov JP (2011). Integrative genomics viewer. Nature biotechnology 29, 24–26. 10.1038/nbt.1754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dobin A, Davis CA, Schlesinger F, Drenkow J, Zaleski C, Jha S, Batut P, Chaisson M, and Gingeras TR (2013). STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics 29, 15–21. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pertea M, Kim D, Pertea GM, Leek JT, and Salzberg SL (2016). Transcript-level expression analysis of RNA-seq experiments with HISAT, StringTie and Ballgown. Nature protocols 11, 1650–1667. 10.1038/nprot.2016.095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gratz SJ, Rubinstein CD, Harrison MM, Wildonger J, and O’Connor-Giles KM (2015). CRISPR-Cas9 Genome Editing in Drosophila. Current protocols in molecular biology / edited by Frederick M. Ausubel … [et al.] 111, 31 32 31–20. 10.1002/0471142727.mb3102s111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ren X, Sun J, Housden BE, Hu Y, Roesel C, Lin S, Liu LP, Yang Z, Mao D, Sun L, et al. (2013). Optimized gene editing technology for Drosophila melanogaster using germ line-specific Cas9. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110, 19012–19017. 10.1073/pnas.1318481110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Love MI, Huber W, and Anders S (2014). Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol 15, 550. 10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Frazee AC, Pertea G, Jaffe AE, Langmead B, Salzberg SL, and Leek JT (2015). Ballgown bridges the gap between transcriptome assembly and expression analysis. Nature biotechnology 33, 243–246. 10.1038/nbt.3172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Thaben PF, and Westermark PO (2014). Detecting rhythms in time series with RAIN. J Biol Rhythms 29, 391–400. 10.1177/0748730414553029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wu G, Anafi RC, Hughes ME, Kornacker K, and Hogenesch JB (2016). MetaCycle: an integrated R package to evaluate periodicity in large scale data. Bioinformatics 32, 3351–3353. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btw405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lugena AB, Zhang Y, Menet JS, and Merlin C (2019). Genome-wide discovery of the daily transcriptome, DNA regulatory elements and transcription factor occupancy in the monarch butterfly brain. PLoS Genet 15, e1008265. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1008265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Agrawal P, and Hardin PE (2016). The Drosophila Receptor Protein Tyrosine Phosphatase LAR Is Required for Development of Circadian Pacemaker Neuron Processes That Support Rhythmic Activity in Constant Darkness But Not during Light/Dark Cycles. J Neurosci 36, 3860–3870. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4523-15.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data S1. ChIP-seq analysis of CWO and CLK binding targets at ZT2 and ZT14. Related to Figure 1 and STAR Methods. CWO and CLK binding targets identified at ZT2 and ZT14 are listed from highest to lowest peak score. A) Genes targeted by CWO at ZT2 after removing binding peaks mapping to intergenic regions. B) Genes targeted by CWO at ZT14 after removing binding peaks mapping to intergenic regions. C) Genes targeted by CLK at ZT2 after removing binding peaks mapping to intergenic regions. D) Genes targeted by CLK at ZT14 after removing binding peaks mapping to intergenic regions. E) Total CWO binding peaks at ZT2. F) Total CWO binding peaks at ZT14. G) Total CLK binding peaks at ZT2. H) Total CLK binding peaks at ZT14.