Abstract

The incidence and lethality of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) will continue to increase in the next decade. For most patients, chemotherapeutic combination therapies remain the standard of care. The development and successful implementation of precision oncology in other gastrointestinal tumor entities point to opportunities also for PDAC. Therefore, markers linked to specific therapeutic responses and important subgroups of the disease are needed. The MYC oncogene is a relevant driver in PDAC and is linked to drug resistance and sensitivity. Here, we update recent insights into MYC biology in PDAC, summarize the connections between MYC and drug responses, and point to an opportunity to image MYC non-invasively. In sum, we propose MYC-associated biology as a basis for the development of concepts for precision oncology in PDAC.

Keywords: Pancreatic cancer, Precision oncology, MYC, Targeted therapies

Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma (PDAC)

Current estimates show that PDAC will be the second leading cause of cancer-related death reason by 2040 [1]. Together with a dismal prognosis reflected by a 5-year survival rate of 10% [2], these data imply the urgent need to intensify research into the disease. Approximately 85% of patients with PDAC are diagnosed with a locally advanced or disseminated disease that prevents surgical resection. For the small group of patients with a resectable tumor, adjuvant chemotherapy according to a modified regimen with folinic acid, 5‐fluorouracil (5‐FU), irinotecan, and oxaliplatin (mFOLFIRINOX) has been established and has improved overall survival [3]. Furthermore, neoadjuvant therapeutic regimens are in clinical development [3]. For the majority of patients with locally advanced or disseminated disease, systemic chemotherapy with FOLFIRINOX or the combination of nab-paclitaxcel and gemcitabine is used [4]. Although these therapies remain standard of care, overall response rates of only 20–30% and significant toxicities must be considered [4]. Therefore, the development of improved therapies is urgently required.

In contrast with the current “one-size-fits-all” clinical trials, precision oncology based on markers to guide therapy selections has the promises to improve outcomes. Precision oncology is also emerging in gastrointestinal (GI) cancers, and molecular profiling was recently highlighted by the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) as the advance of the year 2021 for GI cancers [5]. Examples include clinical trials in HER2 positive gastric cancer [6], the Viktory umbrella trial in gastric cancer [7], the approval of targeted therapies for cholangiocarcinomas with FGFR2 fusions or rearrangements [8], or the use of a triple targeted therapy in BRAF mutated colon cancer [9]. Precise therapies have also been shown to affect PDAC patient survival [10]. Thus, further markers that characterize relevant PDAC subtypes, which are associated with specific drug responses, are needed. We propose the concept that the myelocytomatosis oncogene (MYC) is a relevant biomarker for PDAC. This is based on the strong biology and specific phenotypes associated with MYC, the differential drug sensitivity of cancers with deregulated MYC, and the emerging ability to image MYC non-invasively.

An update of MYC-driven biology in PDAC

KRAS mutations occur in over 90% of PDACs [11] and MYC, a basic-helix-loop–helix/leucine zipper transcription factor (TF), has an important function as an integrator of signaling pathways triggered by oncogenic KRAS [12]. MYC heterodimers (e.g., MYC/MAX) bind to cis-regulatory E-box sequences of numerous genes involved in the regulation of growth, proliferation, or metabolism, thereby serving all hallmark demands of cancer cells [13, 14]. MYC marks an aggressive PDAC subtype, which is supported by the fact that amplifications of MYC have been associated with a worse survival of PDAC patients [15]. Pre-clinical experimental evidence underscores that MYC is an essential and non-redundant node of oncogenic signaling and therefore should be an exceptional therapeutic target [16–18]. We have recently summarized PDAC-specific functions of MYC [19–21] and therefore focus here on recent developments. The MYC network is activated in the so-called basal-like subtype, which is the most aggressive subtype and refractory to current therapies [22–26]. MYC amplifications occur more frequently in PDAC liver metastases, implicating a role of MYC in this process [27]. Interestingly, metastatic PDAC can be grouped into a low frequency metastasis group (< 10 metastases) and high frequency metastasis (> 10 metastases) group, with the high metastasis frequency group having lower overall survival [28]. Genomic and transcriptomic analyses linked MYC to the high metastasis group [28]. Furthermore, adenosquamous cancers of the pancreas showed a high MYC amplification frequency [29].

In addition to its multiple implications in controlling cancer cell biology, MYC`s important role in remodeling the tumor microenvironment (TME) is emerging. The TME is a unique feature of PDAC, evidenced by a prominent desmoplastic reaction that accounts for up to 90% of the tumor mass/volume [30]. Inducing Myc together with the Kras oncogene in murine in vivo PDAC models has an immediate and profound effect on the TME. This MYC-mediated TME-reprogramming is characterized by the attraction of immune cells such as macrophages, neutrophils, granulocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cells and B-cells, while CD3+ T-cells are depleted [31], collectively shaping an immunosuppressive phenotype. Consistently, MYC and BRAF synergistically drive immune-evasion downstream of KRAS [32], supporting a prominent role of MYC in this process. In addition to the immune compartment, MYC instructs the proliferation of fibroblasts and stellate cells, leading to the characteristic tumor desmoplasia [31].

Mechanistically, a link of MYC to immune evasion in PDAC at different levels is described. Double-stranded RNA (dsRNA), derived from intronic inverted repetitive elements, activates the pattern recognition receptor TLR3 and its downstream effector, the serine-threonine kinase TANK-binding kinase 1 (TBK1) [33]. Here, MYC/MIZ1-mediated repression of vesicular transport genes result in decreased dsRNA secretion and consequently decreased activation of TLR3-TBK1-NFκB signaling pathway, which is required for activation of the immune response by controlling the expression of MHC class I antigens [33]. Furthermore, paracrine signals, such as the GAS6–AXL pathway [31] or MYC-dependent repression of the type I interferon pathway [34], account for the TME remodeling. In addition, the folate cycle enzyme methylenetetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase 2 (MTHFD2) was recently demonstrated to facilitate immune escape of PDAC cells. Mechanistically, MTHFD2 promotes the production of uridine diphosphate N-acetylglucosamine (UDP-GlcNAc), leading to O-GlcNAcylation of MYC, a post-translational modification (PTM), that results in its stabilization, and the subsequent increased expression of programmed cell death 1 ligand 1 (PD-L1), thereby blocking anti-tumor immune responses [35]. The effects of MYC on the TME have also been connected to the metastatic cascade. It was suggested that a panel of chemokines and cytokines upregulated in MYC overexpressing cells, including MIF, IL24, CCL4, CCL3, CXCL2, or CXCL3, contributes to the recruitment of pro-metastatic tumor-associated macrophages [28].

Importantly, a reciprocal stroma-to-tumor cell signaling is relevant. Here, a pathway is described in which the fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 (FGFR1) activated by FGF1-derived from cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) is augmenting the tumor cell intrinsic MYC signal [36]. Furthermore, JAK1-STAT6-MYC-mediated increase in expression of enolase 1 and hexokinase (HK2)—enzymes involved in glycolysis—is promoted by IL4 and IL13 cytokines present in the TME, revealing the complex modalities of signals integrated by MYC [37]. In sum, MYC not only integrates KRAS-driven cellular signaling, but reciprocally controls communication with the TME to orchestrate the overall tumor biology. Taken together, this novel knowledge of how MYC shapes the TME additionally underscores its value as a therapeutic target and will open opportunities to implement immunotherapies in combination with concepts to block MYC.

MYC stratifies for therapies

Across all TF and cross-tumor entities, MYC exhibits the most frequent drug interactions [38]. This finding is based on several molecular features. The oncogenic addiction of cancer cells on MYC explains the increased sensitivity of cancer cells to drugs targeting MYC directly or indirectly. Furthermore, MYC-mediated oncogenic stress demands the activation of genes or pathways allowing the cancer cells to cope with. This renders cancer cells with deregulated MYC particularly sensitive to inhibitors of such pathways. The existence of MYC-associated synthetic dosage lethality is well documented by unbiased genetic and pharmacological screening experiments [39] and is relevant in the context of PDAC [21]. Genes allowing to tolerate MYC-induced oncogenic stress may be involved in feedforward regulatory circuits and blocking of such a gene also impacts on MYC expression. Importantly, MYC also marks resistance phenotypes that are currently emerging. Here, we summarize selected connections between MYC and drug sensitivity in PDAC cells.

Drug resistance and MYC

With regard to resistance phenotypes, MYC has been associated with modulation of the sensitivity of inhibitors of the serine/threonine protein kinase mammalian target of rapamycin (MTOR). MTOR is an important therapeutic target in PDAC, and combination therapies based on MTOR inhibitors (MTORi) are currently under development [40–44]. Genetic gain- and loss-of-function experiments demonstrated that MYC confers resistance to the MTORi INK128 (Sapanisertib) [45], a highly selective ATP-competitive inhibitor of the kinase under clinical development (e.g., NCT02197572, NCT02893930, NCT03430882). The MYC protein has a high turnover regulated by oncogenic signaling that cumulates in post-translational-modifications (PTMs) of the protein. KRAS induces stabilization of MYC through ERK-mediated phosphorylation of serine 62 (S62) [46]. The MYC-phospho-S62 counteracting protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A) de-phosphorylates S62, thereby initiating ubiquitin-dependent degradation of MYC. PP2A is a well-described regulator of MYC protein expression in PDAC [47]. Consequently, small-molecules activators of PP2A, like DT1154 [48], synergize with the MTORi INK128 in PDAC in vitro and in vivo models [45].

Additionally, also secondary resistance phenotypes to targeted therapies may also be mediated by MYC. Interference with the canonical KRAS-MEK-ERK signaling induced downregulation of MYC protein expression. Therefore, MEKi perturbs MYC-directed and pentose phosphate pathway (PPP)-mediated nucleotide synthesis with a subsequent growth arrest. Interestingly, in PDAC cells generated as MEKi resistant, MYC escaped regulation and maintained nucleotide synthesis contributing to the resistance phenotype [49].

MYC-induced resistance occurs not only to targeted therapies, but also with conventional chemotherapeutic agents. MYC has been shown to promote epithelial-neuroendocrine lineage plasticity, a state characterized by the increased expression of neuroendocrine markers, like synaptophysin, and resistance to gemcitabine [50]. Lowering MYC expression by an RNA interference approach increased the sensitivity of PDAC cells to gemcitabine [50]. In addition to primary chemotherapy resistance, MYC has been shown to be involved in secondary resistance to paclitaxel [51]. Low-passaged primary PDAC cultures and a ramp-up protocol to induce paclitaxel resistance were used to generate secondary resistant models. Analysis of the models illustrated increased expression of MYC mRNA and protein expression. Furthermore, reduction in MYC expression increased paclitaxel-induced cell death in the resistant lines, whereas overexpression reduced paclitaxel-induced cell death in the parental PDAC cells [51]. Interestingly, gemcitabine was found to trigger a MYC-associated vulnerability in unbiased screening experiments [38, 52, 53] and deregulated MYC sensitizes to mitotic perturbants, including paclitaxel [54, 55]. Such data highlight the need for further research on MYC-associated vulnerabilities and point to a specific context, exemplified here by lineage or secondary versus primary resistance, that needs to be understood.

Targeting MYC in PDAC

Direct targeting of MYC remains a challenge and no small molecule inhibitor has made it to the clinic so far [13, 56]. Due to recent developments, we will only shortly describe OMOMYC, a dominant negative MYC dimerization inhibitor. OMOMYC, a 91 amino acids mutant version of the MYC dimerization domain, prevents MYC from binding to its target genes. In several cancer mouse models, conditional expression of OMOMYC dramatically impacts on tumor growth [17, 57, 58]. In vitro, an inducible OMOMYC reduced the clonogenic growth of murine PDAC cell lines [59]. The concept was recently advanced by the development of an OMOMYC mini-protein. The in vivo efficacy of the mini-protein was demonstrated in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) models [18]. The mini-protein penetrates many organs, including the pancreas [18]. Importantly, a phase I/II clinical trial of the OMOMYC mini-protein (OMO-103) was started in 2021 (NCT04808362), bringing direct MYC inhibition to the clinic. In addition to OMOMYC mini-proteins, it is foreseeable that advanced drug development methods, such as the proteolysis targeting chimera (PROTAC) technology, will lead to the development of clinical candidates that directly and specifically targeting MYC (Fig. 1) [60].

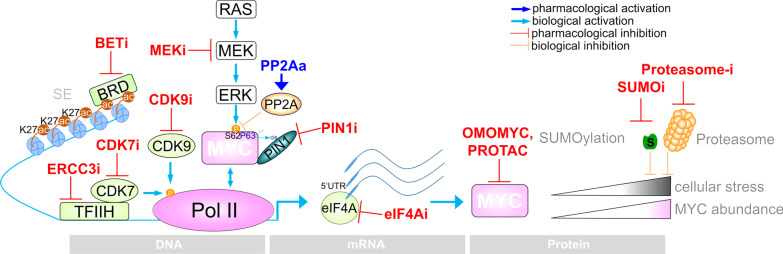

Fig. 1.

Targeting of MYC. Illustrated are options of direct or indirect MYC inhibition by pharmacological inhibitors or activators, respectively. Indirect inhibition is achieved by interfering with transcription, translation. The concept to target MYC by synthetic lethality in PDAC is shown. Direct inhibition by a synthetic OMOMYC peptide or possibly by PROTACs renders the MYC protein itself nonfunctional. SE Super enhancer, BRD Bromodomain proteins

Several approaches to indirectly target MYC expression exist, and we will summarize some with documented relevance in PDAC (Fig. 1). Members of the bromo- and extra-terminal domain (BET) motif protein family, BRD2, BRD3, BRD4, and BRDT, are involved in the regulation of many cancer-relevant pathways, and BET inhibitors (BETi) are in clinical development [61]. Expression of cancer driver genes is often regulated by so-called super-enhancers (SE), specialized cis-acting regulatory elements characterized by an enriched acetylation of histone H3 lysine 27 (H3K27ac), which stimulate high-level expression of associated genes. These enhancers are particularly sensitive to BETi [62] so that oncogenic drivers, including MYC, can be inhibited. Inhibition of MYC expression by BETi has also been documented in PDAC [63]. In primary patient-derived xenografts, a less differentiated PDAC subtype, with a high proliferation index and shorter survival, was characterized [64]. This subtype was characterized by a MYC-driven transcriptional program and sensitivity to BETi [64]. The study was recapitulated in human PDAC organoids, a model with a potential predictive power for the clinical behavior of solid cancers [65]. Again, the defined MYC-signature co-segregates with higher sensitivity to the BETi JQ1 and NHWD-870 [66].

In addition to BETi, inhibitors of histone deacetylases (HDAC) target MYC expression and the MYC-driven transcriptional program in PDAC [67]. Furthermore, HDAC were shown to tune the MYC program and repress a gene program linked to epithelial differentiation [68]. Blocking HDAC function by inhibitors induces these genes in a BRD4-dependent fashion [68], furthermore underlining the close interplay between HDAC and BET proteins. Such connections might contribute to the described synergism of BETi and HDACi in patient-derived xenograft models and are underpinned by the profound effect of the combined inhibition of HDACs and BET on MYC protein expression [63]. Recently dual BET/HDAC inhibitors were developed and tested in PDAC models. Notably, after prolonged treatment, TW9, a dual BET/HDACi, distinctly reduced MYC expression [69]. However, other SE-controlled cancer drivers, including the AP1-TF family member FOSL1, also appear to be targeted by TW9 [69].

The ATP-dependent DNA helicase excision repair cross-complementation protein 3 (ERCC3) is a component of the general transcription factor TFIIH, which is part of the transcriptional preinitiation complex (Fig. 1). ERCC3 can be targeted by the natural diterpenoid epoxide triptolide [70]. In an unbiased pharmacological screening experiment, high activity of triptolide for PDAC was found. Mechanistically, triptolide reduced MYC mRNA and protein expression [71] by disrupting the activity of SE and causing downregulation of associated genes, including MYC [72]. The high efficacy of triptolide has been demonstrated in in vitro and in vivo models of PDAC with deregulated MYC expression [71], allowing to tackle this particular subtype.

In addition to transcriptional or post-translational interference with MYC, the translation of MYC can also be pharmacologically disrupted (Fig. 1). The mRNA of MYC harbors a structured 5′UTR, which is characteristic for translation controlled by the RNA helicase eukaryotic initiation factor 4A (eIF4A) [73]. Therefore, the use of eIF4A inhibitors to impair MYC expression in PDAC is an attractive option. The eIF4A inhibitor CR-1-31B demonstrated high efficacy both in vivo and in vitro [73, 74]. This class of inhibitors (e.g., zotatifine) is currently being tested in a phase 1–2 clinical trial in PDAC patients (NCT04092673). Consistent with the complex cross-talk of MYC with the TME, the natural eIF4A inhibitor silvestrol augmented the activity of an anti-PD1 antibody therapy [75].

The peptidyl-prolyl cis–trans isomerase NIMA-interacting 1 (PIN1), which induces conformational changes in certain phosphorylated proteins, is overexpressed in many cancers [76]. Proline-guided serine or threonine phosphorylation is a typical PTM, conducted by kinases like ERK or cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs). PIN1 complexes with serine 62-phosphorylated MYC leading to trans > cis isomerization of proline 63 [77], which prevents phosphatase activity and an increased DNA binding capacity of MYC. Genetic gain- and loss-of-function experiments have demonstrated that the transcriptional output of MYC is controlled by PIN1 [78]. Recently the covalent, highly selective PIN1 inhibitor sulfopin was shown to downregulate the MYC transcriptional network [79]. Interestingly, sulfopin reduced PDAC growth and prolonged survival in an immune-proficient orthotopic transplantation model in vivo [79].

Targeting MYC-associated vulnerabilities

MYC renders cancer cells dependent on a properly functioning transcriptional machinery [80]. Initiation, pausing, and elongation of the RNA polymerase II (Pol II) are tightly controlled. One control mechanism is integrated by phosphorylation of the carboxy-terminal domain (CTD) of the largest subunit of Pol II, with the CTD integrating the activity of the transcriptional CDKs, like CDK7 or CDK9 [81]. CDK7 acts at multiple sites in the transcriptional cycle and is involved in Pol II-dependent transcriptional entry as well as in the activation of CDK9, involved in transcriptional pause release [81]. A pharmacological screening of epigenetic drugs in human PDAC cell lines revealed the CDK7i THZ1 as a prominent hit. The sensitivity of THZ1 strongly correlated with MYC expression and the activity of the associated network [82]. Selective CDK7 inhibitors, such as the orally available CDK7i CT7001 or SY-5609, are currently tested in clinical trials in patients with solid cancers (NCT03363893, NCT04247126), demonstrating the clinical potential. In addition to CDK7, higher activity of CDK9i in cancers with deregulated MYC is already known [83]. In PDAC, the connection of CDK9i (UNC10112785) to MYC was recently found in a screen using a MYC degradation reporter system. In addition to the decrease in MYC mRNA, CDK9 was shown to induce phosphorylation of serine 62 and thus MYC stability, arguing for a feed forward loop [84].

A drug screening of FDA approved anti-cancer drugs and analysis of several public repositories revealed an increased sensitivity toward perturbations of the protein homeostasis in MYChigh PDAC cells [52]. MYC orchestrates a variety of biological processes by regulating and tuning the transcriptional and translational output [85]. Due to the high amount of protein load in cancer cells and a protein biosynthesis machinery acting at the upper limit, cells with high MYC expression are associated with an increased unfolded protein response (UPR). The strong connection of MYC activity and the UPR is also documented across species [86] and cancer entities [87, 88], explaining increased sensitivity to perturbations in protein homeostasis.

A recent study connected MYC to PDAC with increased expression of the small ubiquitin-like modifier (SUMO)-ylation machinery [89]. The enzymatic cascade of SUMOylation is analogous to ubiquitination, which consists of a single heterodimeric SUMO activating enzyme (E1), a single SUMO conjugating enzyme (E2), and less well-defined SUMO ligases (E3) [21, 88]. Recently, pharmacological SUMO inhibition was shown to be particularly potent in PDAC cells, which are characterized by high MYC activity [89]. This synthetic lethality has already been demonstrated in other entities [90–92] and demonstrated a MYC-dependent and entity-independent vulnerability. SUMO inhibitors such as Subasumstat (TAK-981) are currently under clinical development in advanced solid cancers (NCT04381650).

Imaging MYC in PDAC

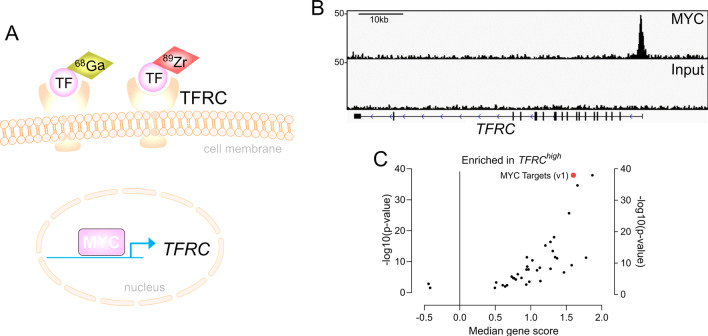

Considering the strong association of MYC with drug responsive states, non-invasive imaging-based biomarkers indicative for activity of MYC will help to stratify PDAC patients for specific therapies. Nearly three decades ago, Indium-111-labeled antisense-oligonucleotides were used to measure MYC mRNA in breast cancer mouse models [93]. However, this imaging method revealed hurdles, such as limited tracer delivery due to physical barriers, target sequence selection, or low stability [94]. In 2012, the radiotracer 89Zirconium (Zr)-desferrioxamine transferrin (89Zr-Tf) was developed and 89Zr-Tf PET imaging was shown to annotate the MYC status [95]. The transferrin receptor (TfR1, TFRC, CD71; TFRC afterwards) is a transmembrane glycoprotein, which acts as a disulfide bond-linked dimer. Transferrin, bound by two iron atoms, shows the highest affinity for the TFRC, and upon binding, transferrin and the receptor are internalized by endocytosis and iron replenish the intracellular pools [96]. Iron is needed for many cellular processes serving the demands of cancer cells, including mitochondrial respiration to generate energy, building of ribonucleotides for DNA synthesis, or DNA repair [96]. MYC directly activates the TFRC gene (Fig. 2) to serve the iron demands of aggressive cancers [97], allowing to indirectly image its activity. Initially 89Zr-Tf PET imaging was developed to annotate MYC in prostate cancer models [95]. Meanwhile, this imaging modality was demonstrated to define the MYC status in other tumor entities, like triple negative breast cancer models [98] and allows monitoring of treatment induced changes of MYC expression (Fig. 2) [99]. 89Zr-Tf PET imaging was also evaluated in PDAC models and determines the extent of the KRAS signaling output and the downstream integrator MYC [100]. Furthermore, the imaging modality was shown to be useful to monitor pharmacological interference with pathways integrated by MYC or drugs which target MYC [100].

Fig. 2.

Imaging of MYC. A Scheme for non-invasive annotating the MYC status. The TFRC gene is a MYC target. The Transferrin receptor can be imaged with a radiotracer, here 89Zr-labeled transferrin (TF) or 68Ga-citrate, which binds transferrin (TF). Overexpression of MYC leads to increased TFRC expression and augmented PET signal. B MYC and control Input ChIP-Seq data of human PDAC cells (MiaPaCa-2) published by Bhattacharyya et al. 2020 [36], were analyzed for specific binding of MYC to the TFRC gene. In addition, the exon structure of the TFRC gene is depicted (black boxes). C A mRNA expression dataset of human PDAC were retrieved via the publication of Bailey et al. [22] and curated as described [52]. A gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) of Hallmark signatures via the GeneTrial 3.0 platform [110] was conducted comparing PDACs with TFRC mRNA expression in the highest quartile (Q4) versus PDACs in the quartiles Q1, Q2, and Q3. Each dot represents a significant hallmark signature. The MYC HALLMARK (v1) signature is highlighted in red

Alternatives to the 89Zr-Tf PET imaging were also developed. A human anti-transferrin receptor monoclonal antibody labeled with 89Zr as a PET probe was investigated in PDAC and shown to allow measurement of the TFRC in xenograft models [101]. In addition, 68Ga-citrate, which binds to transferrin, can be used to image the TFRC (Fig. 2) [102]. In prostate cancer models, PET imaging with the tracer 68Ga-citrate was shown to substitute the 89Zr-Tf PET imaging and some hints of the association of the signal with MYC deregulated cancers were provided [103], increasing the number of imaging modalities to annotate MYC. However, a combination of different imaging and genetic approaches may allow more precise stratification and further prospective studies are needed to validate MYC centric imaging modalities.

Conclusions

Successful concepts for precision oncology require strong drivers of cancer subtypes as biomarkers, that are associated with different drug sensitivity phenotypes, like MYC. However, multiple layers of such an approach need to be advanced, from a better understanding of the MYC-associated drug response to modalities for mapping MYC activity.

Current markers of drug responsiveness only enrich for a responding population, and even cancer stratified by MYC will only increase the proportion of patients who respond to a particular therapy. Therefore, the drug response in PDACs with high MYC activity that does not respond to therapies and trigger associated vulnerability needs to be better characterized and will lead to bi- or trivalent selection markers and molecular combination therapies. Therefore, the context in which MYC operates needs to be better defined experimentally.

Molecular and functional imaging also needs to evolve, and the integration of multimodal imaging can increase the precision in terms of biomarkers and targets. Since MYC is a central regulator of glycolysis and regulates the transcription of glycolytic genes, such as HK2, ENO1, LDHA, SLC2A1 [104, 105], glycolysis might be used as surrogate and an indirect imaging approach to determine MYC activity. In a MYC-inducible model of liver cancer, glycolysis could be visualized by hyperpolarized 13C magnetic resonance spectroscopy and its activity could be attributed to the MYC oncogene [106]. In breast cancer, 18F-FDG PET can image basal-like cancers with deregulated MYC [107]. Glycolysis- and MYC-networks enrich in basal-like PDAC [11], offering an additional opportunity for imaging. As a future example of a multimodal imaging approach, 18F-FDG PET combined with imaging of the MYC-TFRC circuit might enable a more accurate discrimination of basal-like subtypes with deregulated MYC. However, other oncogenic pathways, particularly the PI3K-AKT pathway [108] or hypoxia-mediated activation of the hypoxia-inducible factor 1 (HIF) [109], have also been shown to induce glycolysis. Therefore, there is a definite need for more pre-clinical evidence of such concepts followed by prospective clinical evaluation. In addition, such clinical non-invasive imaging modalities demand to be accompanied by longitudinal biopsy programs to link imaging with molecular features. Finally, more direct non-invasive MYC imaging modalities should be developed. Interestingly, the OMOMYC mini-protein labeled with 89Zr (Omomyc-deferoxamin-maleimide(DFO)-89Zr) was shown to accumulate in mouse lung tumors after intranasal application [18], which will allow further development of OMOMYC mini-proteins into imaging probes for annotation of MYC status as well as for cancer theranostics.

Acknowledgements

We apologize for not citing any relevant reports due to the need to selectively choose examples, a lack of space, or an oversight on our part. Drawing tools from motifolio.com.

Authors' contributions

All authors involved in conception and design of the article; interpretation of data; drafting of the manuscript; revised the manuscript for important intellectual content; and approved the final version submitted for publication.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. DFG-SFB824 Project C9 to G.S. and D.S. and Project C3 to U.K.; DFG-SFB1321 (Project-ID 329628492) to G.S. and D.S., DFG-SCHN959/3-2 and SCHN959/6-1 to G.S., Deutsche Krebshilfe (70113760 to G.S., 70114425 to U.K.), Wilhelm Sander Stiftung (2017.048.2 to G.S and U.K. and 2019.086.1 to G.S.). A Stiftung Charite research grant to U.K.. The funding agencies had no influence on any aspect of the study.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

Ulrich Keller has served in an advisory role for Takeda unrelated to the content of this manuscript. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Günter Schneider and Matthias Wirth have contributed equally to this work

Contributor Information

Günter Schneider, Email: guenter.schneider@med.uni-goettingen.de.

Matthias Wirth, Email: matthias.wirth@charite.de.

References

- 1.Rahib L, Wehner MR, Matrisian LM, Nead KT. Estimated projection of US Cancer incidence and death to 2040. Jama Netw Open. 2021;4:e214708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2021. Ca Cancer J Clin. 2021;71:7–33. doi: 10.3322/caac.21654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mavros MN, Moris D, Karanicolas PJ, Katz MHG, O’Reilly EM, Pawlik TM. Clinical trials of systemic chemotherapy for resectable pancreatic cancer. Jama Surg. 2021;156. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Smithy JW, O’Reilly EM. Pancreas cancer: therapeutic trials in metastatic disease. J Surg Oncol. 2021;123:1475–1488. doi: 10.1002/jso.26359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith SM, Wachter K, Burris HA, Schilsky RL, George DJ, Peterson DE, et al. Clinical cancer advances 2021: ASCO’s report on progress against cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39:1165–1184. doi: 10.1200/JCO.20.03420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roviello G, Aprile G, D’Angelo A, Iannone LF, Roviello F, Polom K, et al. Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) in advanced gastric cancer: where do we stand? Gastric Cancer. 2021;1–15. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Lee J, Kim ST, Kim K, Lee H, Kozarewa I, Mortimer PGS, et al. Tumor genomic profiling guides patients with metastatic gastric cancer to targeted treatment: the VIKTORY umbrella trial. Cancer Discov. 2019;9:1388–1405. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-19-0442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abou-Alfa GK, Sahai V, Hollebecque A, Vaccaro G, Melisi D, Al-Rajabi R, et al. Pemigatinib for previously treated, locally advanced or metastatic cholangiocarcinoma: a multicentre, open-label, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:671–684. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30109-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kopetz S, Grothey A, Yaeger R, Cutsem EV, Desai J, Yoshino T, et al. Encorafenib, binimetinib, and cetuximab in BRAF V600E–mutated colorectal cancer. New Engl J Med. 2019;381:1632–1643. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1908075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pishvaian MJ, Blais EM, Brody JR, Lyons E, DeArbeloa P, Hendifar A, et al. Overall survival in patients with pancreatic cancer receiving matched therapies following molecular profiling: a retrospective analysis of the Know Your Tumor registry trial. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:508–518. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30074-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Collisson EA, Bailey P, Chang DK, Biankin AV. Molecular subtypes of pancreatic cancer. Nat Rev Gastroenterol. 2019;16:207–220. doi: 10.1038/s41575-019-0109-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schneeweis C, Wirth M, Saur D, Reichert M, Schneider G. Oncogenic KRAS and the EGFR loop in pancreatic carcinogenesis—a connection to licensing nodes. Small Gtpases. 2017;9:457–464. doi: 10.1080/21541248.2016.1262935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wolf E, Eilers M. Targeting MYC proteins for tumor therapy. Annu Rev Cancer Biol. 2020;4:61–75. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ross J, Miron CE, Plescia J, Laplante P, McBride K, Moitessier N, et al. Targeting MYC: from understanding its biology to drug discovery. Eur J Med Chem. 2020;213:113137. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Witkiewicz AK, McMillan EA, Balaji U, Baek G, Lin W-C, Mansour J, et al. Whole-exome sequencing of pancreatic cancer defines genetic diversity and therapeutic targets. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6744. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dang CV, Reddy EP, Shokat KM, Soucek L. Drugging the “undruggable” cancer targets. Nat Rev Cancer. 2017;17:502–508. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2017.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Soucek L, Whitfield J, Martins CP, Finch AJ, Murphy DJ, Sodir NM, et al. Modelling Myc inhibition as a cancer therapy. Nature. 2008;455:679–683. doi: 10.1038/nature07260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beaulieu M-E, Jauset T, Massó-Vallés D, Martínez-Martín S, Rahl P, Maltais L, et al. Intrinsic cell-penetrating activity propels Omomyc from proof of concept to viable anti-MYC therapy. Sci Transl Med. 2019;11:eaar5012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Wirth M, Mahboobi S, Kra mer OH, Schneider G. Concepts to Target MYC in Pancreatic Cancer. Mol Cancer Ther. 2016;15:1792–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Wirth M, Schneider G. MYC: a stratification marker for pancreatic cancer therapy. Trends Cancer. 2016;2:1–3. doi: 10.1016/j.trecan.2015.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schneeweis C, Hassan Z, Schick M, Keller U, Schneider G. The SUMO pathway in pancreatic cancer: insights and inhibition. Br J Cancer. 2021;124:531–538. doi: 10.1038/s41416-020-01119-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bailey P, Chang DK, Nones K, Johns AL, Patch A-M, et al. Genomic analyses identify molecular subtypes of pancreatic cancer. Nature. 2016;531:47–52. doi: 10.1038/nature16965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chan-Seng-Yue M, Kim JC, Wilson GW, Ng K, Figueroa EF, O’Kane GM, et al. Transcription phenotypes of pancreatic cancer are driven by genomic events during tumor evolution. Nat Genet. 2020;52:231–240. doi: 10.1038/s41588-019-0566-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aung KL, Fischer SE, Denroche RE, Jang G-H, Dodd A, Creighton S, et al. Genomics-driven precision medicine for advanced pancreatic cancer: early results from the COMPASS trial. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;24:clincanres.2994.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Muckenhuber A, Berger AK, Schlitter AM, Steiger K, Konukiewitz B, Trumpp A, et al. Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma subtyping using the biomarkers hepatocyte nuclear factor-1A and cytokeratin-81 correlates with outcome and treatment response. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;24:1344–1354. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-2180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Noll EM, Eisen C, Stenzinger A, Espinet E, Muckenhuber A, Klein C, et al. CYP3A5 mediates basal and acquired therapy resistance in different subtypes of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Nat Med. 2016;22:278–287. doi: 10.1038/nm.4038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brar G, Blais EM, Bender RJ, Brody JR, Sohal D, Madhavan S, et al. Multi-omic molecular comparison of primary versus metastatic pancreatic tumours. Br J Cancer. 2019;121:264–270. doi: 10.1038/s41416-019-0507-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maddipati R, Norgard RJ, Baslan T, Rathi KS, Zhang A, Raman P, et al. MYC controls metastatic heterogeneity in pancreatic cancer. Biorxiv. 2021;2021.01.30.428641.

- 29.Lenkiewicz E, Malasi S, Hogenson TL, Flores LF, Barham W, Phillips WJ, et al. Genomic and epigenomic landscaping defines new therapeutic targets for adenosquamous carcinoma of the pancreas. Cancer Res. 2020;80:4324–4334. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-20-0078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hessmann E, Buchholz SM, Demir IE, Singh SK, Gress TM, Ellenrieder V, et al. Microenvironmental determinants of pancreatic cancer. Physiol Rev. 2020;100:1707–1751. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00042.2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sodir NM, Kortlever RM, Barthet VJA, Campos T, Pellegrinet L, Kupczak S, et al. Myc instructs and maintains pancreatic adenocarcinoma phenotype. Cancer Discov. 2020;10:588–607. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-19-0435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ischenko I, D’Amico S, Rao M, Li J, Hayman MJ, Powers S, et al. KRAS drives immune evasion in a genetic model of pancreatic cancer. Nat Commun. 2021;12:1482. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-21736-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Krenz B, Gebhardt-Wolf A, Ade CP, Gaballa A, Roehrig F, Vendelova E, et al. MYC- and MIZ1-dependent vesicular transport of double-strand RNA controls immune evasion in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Res. 2021;canres.CAN-21-1677-E.2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Muthalagu N, Monteverde T, Raffo-Iraolagoitia X, Wiesheu R, Whyte D, Hedley A, et al. Repression of the type I interferon pathway underlies MYC & KRAS-dependent evasion of NK & B cells in Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. Cancer Discov. 2020;10:872–887. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-19-0620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shang M, Yang H, Yang R, Chen T, Fu Y, Li Y, et al. The folate cycle enzyme MTHFD2 induces cancer immune evasion through PD-L1 up-regulation. Nat Commun. 2021;12:1940. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-22173-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bhattacharyya S, Oon C, Kothari A, Horton W, Link J, Sears RC, et al. Acidic fibroblast growth factor underlies microenvironmental regulation of MYC in pancreatic cancer. J Exp Med. 2020; 217(8):e20191805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Dey P, Li J, Zhang J, Chaurasiya S, Strom A, Wang H, et al. Oncogenic Kras driven metabolic reprogramming in pancreas cancer cells utilizes cytokines from the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Discov. 2020;10:608–625. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-19-0297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Garcia-Alonso L, Iorio F, Matchan A, Fonseca N, Jaaks P, Peat G, et al. Transcription factor activities enhance markers of drug sensitivity in cancer. Cancer Res. 2017;78:769–780. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-1679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thng DKH, Toh TB, Chow EK-H. Capitalizing on synthetic lethality of MYC to treat cancer in the digital age. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2021;42:166–82. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.Hassan Z, Schneeweis C, Wirth M, Veltkamp C, Dantes Z, Feuerecker B, et al. MTOR inhibitor-based combination therapies for pancreatic cancer. Br J Cancer. 2018;118:366. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2017.421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Conway JR, Herrmann D, Evans TJ, Morton JP, Timpson P. Combating pancreatic cancer with PI3K pathway inhibitors in the era of personalised medicine. Gut. 2019;68:742. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2018-316822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Driscoll DR, Karim SA, Sano M, Gay DM, Jacob W, Yu J, et al. mTORC2 signaling drives the development and progression of pancreatic cancer. Cancer Res. 2016;76:6911–6923. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-0810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Morran DC, Wu J, Jamieson NB, Mrowinska A, Kalna G, Karim SA, et al. Targeting mTOR dependency in pancreatic cancer. Gut. 2014;63:1481. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-306202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Knudsen ES, Kumarasamy V, Ruiz A, Sivinski J, Chung S, Grant A, et al. Cell cycle plasticity driven by MTOR signaling: integral resistance to CDK4/6 inhibition in patient-derived models of pancreatic cancer. Oncogene. 2019;38:3355–3370. doi: 10.1038/s41388-018-0650-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Allen-Petersen BL, Risom T, Feng Z, Wang Z, Jenny ZP, Thoma MC, et al. Activation of PP2A and inhibition of mTOR synergistically reduce MYC signaling and decrease tumor growth in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Res. 2018;79:209–219. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-18-0717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sears R, Nuckolls F, Haura E, Taya Y, Tamai K, Nevins JR. Multiple Ras-dependent phosphorylation pathways regulate Myc protein stability. Gene Dev. 2000;14:2501–2514. doi: 10.1101/gad.836800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Farrell AS, Allen-Petersen B, Daniel CJ, Wang X, Wang Z, Rodriguez S, et al. Targeting inhibitors of the tumor suppressor PP2A for the treatment of pancreatic cancer. Mol Cancer Res. 2014;12:924–939. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-13-0542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sangodkar J, Perl A, Tohme R, Kiselar J, Kastrinsky DB, Zaware N, et al. Activation of tumor suppressor protein PP2A inhibits KRAS-driven tumor growth. J Clin Invest. 2017;127:2081–2090. doi: 10.1172/JCI89548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Santana-Codina N, Roeth AA, Zhang Y, Yang A, Mashadova O, Asara JM, et al. Oncogenic KRAS supports pancreatic cancer through regulation of nucleotide synthesis. Nat Commun. 2018;9:4945. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-07472-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Farrell AS, Joly MM, Allen-Petersen BL, Worth PJ, Lanciault C, Sauer D, et al. MYC regulates ductal-neuroendocrine lineage plasticity in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma associated with poor outcome and chemoresistance. Nat Commun. 2017;8:1728. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-01967-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Parasido E, Avetian G, Naeem A, Graham G, Pishvaian M, Glasgow E, et al. The sustained induction of c-Myc drives nab-paclitaxel resistance in primary pancreatic ductal carcinoma cells. Mol Cancer Res. 2019;17:1815–1827. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-19-0191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lankes K, Hassan ZZ, Doffo MJ, Schneeweis C, Lier S, Öllinger R, et al. Targeting the ubiquitin-proteasome system in a pancreatic cancer subtype with hyperactive MYC. Mol Oncol. 2020;14:3048–3064. doi: 10.1002/1878-0261.12835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang J, Jiang J, Chen H, Wang L, Guo H, Yang L, et al. FDA-approved drug screen identifies proteasome as a synthetic lethal target in MYC-driven neuroblastoma. Oncogene. 2019;38:6737–6751. doi: 10.1038/s41388-019-0912-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Topham C, Tighe A, Ly P, Bennett A, Sloss O, Nelson L, et al. MYC is a major determinant of mitotic cell fate. Cancer Cell. 2015;28:129–140. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2015.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Littler S, Sloss O, Geary B, Pierce A, Whetton AD, Taylor SS. Oncogenic MYC amplifies mitotic perturbations. Open Biol. 2019;9:190136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 56.Allen-Petersen BL, Sears RC. Mission possible: advances in MYC therapeutic targeting in cancer. BioDrugs. 2019;33:539–553. doi: 10.1007/s40259-019-00370-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Soucek L, Whitfield JR, Sodir NM, Massó-Vallés D, Serrano E, Karnezis AN, et al. Inhibition of Myc family proteins eradicates KRas-driven lung cancer in mice. Gene Dev. 2013;27:504–513. doi: 10.1101/gad.205542.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Annibali D, Whitfield JR, Favuzzi E, Jauset T, Serrano E, Cuartas I, et al. Myc inhibition is effective against glioma and reveals a role for Myc in proficient mitosis. Nat Commun. 2014;5:4632. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jung LA, Gebhardt A, Koelmel W, Ade CP, Walz S, Kuper J, et al. OmoMYC blunts promoter invasion by oncogenic MYC to inhibit gene expression characteristic of MYC-dependent tumors. Oncogene. 2017;36:1911–1924. doi: 10.1038/onc.2016.354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Burslem GM, Crews CM. Proteolysis-targeting chimeras as therapeutics and tools for biological discovery. Cell. 2020;181:102–114. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.11.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Shorstova T, Foulkes WD, Witcher M. Achieving clinical success with BET inhibitors as anti-cancer agents. Br J Cancer. 2021;1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 62.Lovén J, Hoke HA, Lin CY, Lau A, Orlando DA, Vakoc CR, et al. Selective inhibition of tumor oncogenes by disruption of super-enhancers. Cell. 2013;153:320–334. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.03.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mazur PK, Herner A, Mello SS, Wirth M, Hausmann S, Sánchez-Rivera FJ, et al. Combined inhibition of BET family proteins and histone deacetylases as a potential epigenetics-based therapy for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Nat Med. 2015;21:1163–1171. doi: 10.1038/nm.3952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bian B, Bigonnet M, Gayet O, Loncle C, Maignan A, Gilabert M, et al. Gene expression profiling of patient-derived pancreatic cancer xenografts predicts sensitivity to the BET bromodomain inhibitor JQ1: implications for individualized medicine efforts. Embo Mol Med. 2017;9:482–497. doi: 10.15252/emmm.201606975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wensink GE, Elias SG, Mullenders J, Koopman M, Boj SF, Kranenburg OW, et al. Patient-derived organoids as a predictive biomarker for treatment response in cancer patients. Npj Precis Oncol. 2021;5:30. doi: 10.1038/s41698-021-00168-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bian B, Juiz NA, Gayet O, Bigonnet M, Brandone N, Roques J, et al. Pancreatic cancer organoids for determining sensitivity to bromodomain and extra-terminal inhibitors (BETi) Frontiers Oncol. 2019;9:475. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2019.00475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Stojanovic N, Hassan Z, Wirth M, Wenzel P, Beyer M, Schäfer C, et al. HDAC1 and HDAC2 integrate the expression of p53 mutants in pancreatic cancer. Oncogene. 2016;36:1804–1815. doi: 10.1038/onc.2016.344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mishra VK, Wegwitz F, Kosinsky RL, Sen M, Baumgartner R, Wulff T, et al. Histone deacetylase class-I inhibition promotes epithelial gene expression in pancreatic cancer cells in a BRD4- and MYC-dependent manner. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:gkx212-. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 69.Zhang X, Zegar T, Weiser T, Hamdan FH, Berger B, Lucas R, et al. Characterization of a dual BET/HDAC inhibitor for treatment of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2020;147:2847–2861. doi: 10.1002/ijc.33137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Titov DV, Gilman B, He Q-L, Bhat S, Low W-K, Dang Y, et al. XPB, a subunit of TFIIH, is a target of the natural product triptolide. Nat Chem Biol. 2011;7:182–188. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Beglyarova N, Banina E, Zhou Y, Mukhamadeeva R, Andrianov G, Bobrov E, et al. Screening of conditionally reprogrammed patient-derived carcinoma cells identifies ERCC3–MYC interactions as a target in pancreatic cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22:6153–6163. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-0149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Noel P, Hussein S, Ng S, Antal CE, Lin W, Rodela E, et al. Triptolide targets super-enhancer networks in pancreatic cancer cells and cancer-associated fibroblasts. Oncogenesis. 2020;9:100. doi: 10.1038/s41389-020-00285-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Singh K, Lin J, Lecomte N, Mohan P, Gokce A, Sanghvi VR, et al. Targeting eIF4A-dependent translation of KRAS signaling molecules. Cancer Res. 2021;81:2002–2014. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-20-2929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Chan K, Robert F, Oertlin C, Kapeller-Libermann D, Avizonis D, Gutierrez J, et al. eIF4A supports an oncogenic translation program in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Nat Commun. 2019;10:5151. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-13086-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hashimoto A, Handa H, Hata S, Tsutaho A, Yoshida T, Hirano S, et al. Inhibition of mutant KRAS-driven overexpression of ARF6 and MYC by an eIF4A inhibitor drug improves the effects of anti-PD-1 immunotherapy for pancreatic cancer. Cell Commun Signal. 2021;19:54. doi: 10.1186/s12964-021-00733-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Chen Y, Wu Y, Yang H, Li X, Jie M, Hu C, et al. Prolyl isomerase Pin1: a promoter of cancer and a target for therapy. Cell Death Dis. 2018;9:883. doi: 10.1038/s41419-018-0844-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Yeh E, Cunningham M, Arnold H, Chasse D, Monteith T, Ivaldi G, et al. A signalling pathway controlling c-Myc degradation that impacts oncogenic transformation of human cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2004;6:308–318. doi: 10.1038/ncb1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Farrell AS, Pelz C, Wang X, Daniel CJ, Wang Z, Su Y, et al. Pin1 regulates the dynamics of c-Myc DNA binding to facilitate target gene regulation and oncogenesis. Mol Cell Biol. 2013;33:2930–2949. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01455-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Dubiella C, Pinch BJ, Koikawa K, Zaidman D, Poon E, Manz TD, et al. Sulfopin is a covalent inhibitor of Pin1 that blocks Myc-driven tumors in vivo. Nat Chem Biol. 2021;1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 80.Bradner JE, Hnisz D, Young RA. Transcriptional addiction in cancer. Cell. 2017;168:629–643. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Parua PK, Fisher RP. Dissecting the Pol II transcription cycle and derailing cancer with CDK inhibitors. Nat Chem Biol. 2020;16:716–724. doi: 10.1038/s41589-020-0563-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lu P, Geng J, Zhang L, Wang Y, Niu N, Fang Y, et al. THZ1 reveals CDK7-dependent transcriptional addictions in pancreatic cancer. Oncogene. 2019;38:3932–3945. doi: 10.1038/s41388-019-0701-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Huang C-H, Lujambio A, Zuber J, Tschaharganeh DF, Doran MG, Evans MJ, et al. CDK9-mediated transcription elongation is required for MYC addiction in hepatocellular carcinoma. Gene Dev. 2014;28:1800–1814. doi: 10.1101/gad.244368.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Blake DR, Vaseva AV, Hodge RG, Kline MP, Gilbert TSK, Tyagi V, et al. Application of a MYC degradation screen identifies sensitivity to CDK9 inhibitors in KRAS-mutant pancreatic cancer. Sci Signal. 2019;12:eaav7259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 85.Wolpaw AJ, Dang CV. MYC-induced metabolic stress and tumorigenesis. Biochimica Et Biophysica Acta Bba Rev Cancer. 2018;1870:43–50. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2018.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Nagy P, Varga Á, Pircs K, Hegedűs K, Juhász G. Myc-driven overgrowth requires unfolded protein response-mediated induction of autophagy and antioxidant responses in drosophila melanogaster. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:e1003664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 87.Hart LS, Cunningham JT, Datta T, Dey S, Tameire F, Lehman SL, et al. ER stress–mediated autophagy promotes Myc-dependent transformation and tumor growth. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:4621–4634. doi: 10.1172/JCI62973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Wirth M, Schick M, Keller U, Krönke J. Ubiquitination and ubiquitin-like modifications in multiple myeloma: biology and therapy. Cancers. 2020;12:3764. doi: 10.3390/cancers12123764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Biederstädt A, Hassan Z, Schneeweis C, Schick M, Schneider L, Muckenhuber A, et al. SUMO pathway inhibition targets an aggressive pancreatic cancer subtype. Gut. 2020;124:531–538. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2018-317856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kessler JD, Kahle KT, Sun T, Meerbrey KL, Schlabach MR, Schmitt EM, et al. A SUMOylation-dependent transcriptional subprogram is required for Myc-driven tumorigenesis. Science. 2012;335:348–353. doi: 10.1126/science.1212728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Hoellein A, Fallahi M, Schoeffmann S, Steidle S, Schaub FX, Rudelius M, et al. Myc-induced SUMOylation is a therapeutic vulnerability for B-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2014;124:2081–2090. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-06-584524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.He X, Riceberg J, Soucy T, Koenig E, Minissale J, Gallery M, et al. Probing the roles of SUMOylation in cancer cell biology by using a selective SAE inhibitor. Nat Chem Biol. 2017;13:1164–1171. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Dewanjee MK, Ghafouripour AK, Kapadvanjwala M, Dewanjee S, Serafini AN, Lopez DM, et al. Noninvasive imaging of c-myc oncogene messenger RNA with indium-111-antisense probes in a mammary tumor-bearing mouse model. J Nucl Med. 1994;35:1054–1063. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Iyer AK, He J. Radiolabeled oligonucleotides for antisense imaging. Curr Org Synth. 2011;8:604–614. doi: 10.2174/157017911796117241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Holland JP, Evans MJ, Rice SL, Wongvipat J, Sawyers CL, Lewis JS. Annotating MYC status with 89Zr-transferrin imaging. Nat Med. 2012;18:1586–1591. doi: 10.1038/nm.2935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Candelaria PV, Leoh LS, Penichet ML, Daniels-Wells TR. Antibodies targeting the transferrin receptor 1 (TfR1) as direct anti-cancer agents. Front Immunol. 2021;12:607692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 97.O’Donnell KA, Yu D, Zeller KI, Kim J, Racke F, Thomas-Tikhonenko A, et al. Activation of transferrin receptor 1 by c-Myc enhances cellular proliferation and tumorigenesis†. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:2373–2386. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.6.2373-2386.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Henry KE, Dilling TR, Abdel-Atti D, Edwards KJ, Evans MJ, Lewis JS. Noninvasive 89 Zr-transferrin PET shows improved tumor targeting compared with 18 F-FDG PET in MYC-overexpressing human triple-negative breast cancer. J Nucl Med. 2017;59:51–57. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.117.192286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Doran MG, Carnazza KE, Steckler JM, Spratt DE, Truillet C, Wongvipat J, et al. Applying 89Zr-transferrin to study the pharmacology of inhibitors to BET bromodomain containing proteins. Mol Pharm. 2016;13:683–688. doi: 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.5b00882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Henry KE, Dacek MM, Dilling TR, Caen JD, Fox IL, Evans MJ, et al. A PET imaging strategy for interrogating target engagement and oncogene status in pancreatic cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2018;25(25):166–176. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-1485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Sugyo A, Tsuji AB, Sudo H, Nagatsu K, Koizumi M, Ukai Y, et al. Preclinical evaluation of 89Zr-labeled human antitransferrin receptor monoclonal antibody as a PET probe using a pancreatic cancer mouse model. Nucl Med Commun. 2015;36:286–294. doi: 10.1097/MNM.0000000000000245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Larson SM, Rasey JS, Allen DR, Nelson NJ, Grunbaum Z, Harp GD, et al. Common pathway for tumor cell uptake of gallium-67 and iron-59 via a transferrin receptor. J Natl Cancer. 1980;I(64):41–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Aggarwal R, Behr SC, Paris PL, Truillet C, Parker MFL, Huynh LT, et al. Real-time transferrin-based PET detects MYC-positive prostate cancer. Mol Cancer Res. 2017;15:1221–1229. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-17-0196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Osthus RC, Shim H, Kim S, Li Q, Reddy R, Mukherjee M, et al. Deregulation of glucose transporter 1 and glycolytic gene expression by c-Myc*. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:21797–21800. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C000023200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Kim J, Zeller KI, Wang Y, Jegga AG, Aronow BJ, O’Donnell KA, et al. Evaluation of Myc E-box phylogenetic footprints in glycolytic genes by chromatin immunoprecipitation assays†. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:5923–5936. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.13.5923-5936.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Hu S, Balakrishnan A, Bok RA, Anderton B, Larson PEZ, Nelson SJ, et al. 13C-pyruvate imaging reveals alterations in glycolysis that precede c-Myc-induced tumor formation and regression. Cell Metab. 2011;14:131–142. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Palaskas N, Larson SM, Schultz N, Komisopoulou E, Wong J, Rohle D, et al. 18F-fluorodeoxy-glucose positron emission tomography marks MYC-overexpressing human basal-like breast cancers. Cancer Res. 2011;71:5164–5174. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-4633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Hoxhaj G, Manning BD. The PI3K–AKT network at the interface of oncogenic signalling and cancer metabolism. Nat Rev Cancer. 2020;20:74–88. doi: 10.1038/s41568-019-0216-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Denko NC. Hypoxia, HIF1 and glucose metabolism in the solid tumour. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:705–713. doi: 10.1038/nrc2468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Gerstner N, Kehl T, Lenhof K, Müller A, Mayer C, Eckhart L, et al. GeneTrail 3: advanced high-throughput enrichment analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020;48:gkaa306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.