Abstract

Background

Loneliness and social isolation are emerging public health challenges for aging populations.

Methods

We followed N = 11 302 U.S. Health and Retirement Study participants aged 50–95 from 2006 to 2014 to measure persistence of experiences of loneliness and exposure to social isolation. We tested associations of longitudinal loneliness and social isolation phenotypes with disability, morbidity, mortality, and biological aging through 2018.

Results

During follow-up, 18% of older adults met criteria for loneliness, with 6% meeting criteria at 2 or more follow-up assessments. For social isolation, these fractions were 21% and 8%. Health and Retirement Study participants who experienced loneliness and were exposed to social isolation were at increased risk for disease, disability, and mortality. Those experiencing persistent loneliness were at a 57% increased hazard of mortality compared to those who never experienced loneliness. For social isolation, the increase was 28%. Effect sizes were somewhat larger for counts of prevalent activity limitations and somewhat smaller for counts of prevalent chronic diseases. Covariate adjustment for socioeconomic and psychological risks attenuated but did not fully explain associations. Older adults who experienced loneliness and were exposed to social isolation also exhibited physiological indications of advanced biological aging (Cohen’s d for persistent loneliness and social isolation = 0.26 and 0.21, respectively). For loneliness, but not social isolation, persistence was associated with increased risk.

Conclusions

Deficits in social connectedness prevalent in a national sample of U.S. older adults were associated with morbidity, disability, and mortality and with more advanced biological aging. Bolstering social connectedness to interrupt experiences of loneliness may promote healthy aging.

Keywords: Biological aging, Chronic disease, Disability, Healthy aging

Experiences of loneliness and exposure to social isolation are prevalent among older adults, with an estimated 20%–30% reporting some loneliness or social isolation (1,2). They are also associated with increased morbidity and mortality (2–7). Loneliness and social isolation therefore represent an emerging priority for public health intervention, the urgency of which is highlighted by the impact of shelter-in-place policies implemented to mitigate the COVID-19 pandemic (8–11).

Loneliness and social isolation are distinct constructs representing different aspects of social connectedness (12). Loneliness is the subjective feeling of being isolated. Social isolation is the objective state of having limited social interactions. Interventions are now being developed to reduce loneliness and social isolation with the aim of improving health and well-being among older adults (2,13–15). While there is some evidence that reducing loneliness may improve symptoms of depression in older adults (16), it is not known if intervention on loneliness and social isolation can affect physical health-related features of healthy aging.

Cross-sectional studies report associations of loneliness and social isolation with physical health deficits in older adults and also with mortality (2–4,17–19). However, cross-sectional data cannot rule out confounding of associations by preexisting economic and psychological risk factors that may interfere with formation and maintenance of social connections and impair healthy aging. Cross-sectional studies also cannot exclude the possibility of reverse causation, in which disease and disability lead to loneliness and social isolation. A further challenge is that cross-sectional data cannot quantify the persistence of loneliness and social isolation, which may be an important dimension of their impact on healthy aging. Longitudinal data are therefore needed to address 4 questions about links from experiences of loneliness and exposure to social isolation to disease, disability, and mortality:

First, are risks associated with experiences of loneliness and exposure to social isolation independent of economic and psychological vulnerabilities that may cause both social disconnection and deficits in healthy aging? Household poverty and adverse neighborhood conditions can cause older people to become socially disconnected from their communities and are also associated with disease, disability, and mortality (20–22). In parallel, psychological vulnerabilities that put people at risk for loneliness and social isolation, including depressive symptoms and related personality features, are also linked with deficits in healthy aging (23–26). Measurements of economic and psychological vulnerability are needed to disentangle the effects of loneliness and social isolation on deficits in healthy aging from the effects of correlated risk factors.

Second, do experiences of loneliness and exposure to social isolation precede the onset of deficits in healthy aging or, instead, could deficits in healthy aging cause individuals to become lonely or socially isolated? Meta-analyses support deficits in social connectedness as predictors of future cardiovascular morbidity and all-cause mortality (7,27). However, data are more limited for prospective relationships with other types of morbidity and disability (2–4,28). Longitudinal data can help clarify the extent of prospective links between deficits in social connectedness and deficits in healthy aging (17).

Third, does the persistence of experiences of loneliness and exposure to social isolation worsen health impacts? Interventions to address loneliness and social isolation aim to improve health by reducing the burden of loneliness and social isolation among individuals who are already lonely and socially isolated (13). However, it is not known if reducing the persistence of loneliness and social isolation will offer protection against deficits in healthy aging. Studies with measures of loneliness and social isolation at multiple time points can compare healthy aging outcomes among those whose symptoms persist to those with intermittent symptoms.

Fourth, there is need to identify biological measurements that can inform mechanisms through which experiences of loneliness and exposure to social isolation may affect healthy aging and provide a healthy-aging surrogate endpoint for interventions to address deficits in social connectedness. Biological aging is hypothesized to be the core mechanism driving age-dependent increases in risk for disease, disability, and mortality (29). There is already evidence that loneliness may compromise immune-system integrity, driving systemic inflammation (30), a pillar of aging (31). However, no studies have yet tested relationships of loneliness and social isolation with biological aging.

To address these questions and build knowledge to inform design of future programs and policies, we analyzed data from the U.S. Health and Retirement Study (HRS), a large national sample of older adults followed longitudinally from 1992 and most recently surveyed in 2016–2018. HRS surveys older adults aged 50+, allowing us to investigate healthy aging sequelae of experiences of loneliness and exposure to social isolation across the second half of the life course. We conducted analysis to evaluate associations of loneliness and social isolation with 3 key dimensions of healthy aging, mortality, disability, and morbidity, and explored a potential link between experiences of loneliness and exposure to social isolation and more advanced biological aging.

Method

Study Population

The HRS is a longitudinal biennial cohort study of a nationally representative sample of noninstitutionalized adults over the age of 50 and their spouses. The HRS selected participants using multistage probability sampling designed to represent adults over the age of 50 in the United States. We analyzed HRS data from RAND corporation (32) including 42 042 participants. We linked RAND files with data from the HRS Leave Behind Questionnaires (LBQ) collected during 2006–2014 (33) and from the HRS Venous Blood Study (VBS) collected in 2016 (34).

Measures

Loneliness and social isolation

We measured experiences of loneliness and exposure to social isolation from data collected during 2006–2014 in the HRS Core Interview and LBQ. The LBQ is a self-administered survey about life circumstances, subjective well-being, and lifestyle. A random subsample of 50% of HRS participants completed the LBQ in 2006 and the other 50% in 2008. Thereafter, these subsamples completed the LBQ at alternating waves (ie, every 4 years).

Loneliness

We measured experiences of loneliness using a 3-item version of the Revised UCLA Loneliness Scale (35). Participants rated how frequently they felt they were (i) lacking companionship, (ii) left out, and (iii) isolated from others on a 3-point scale. Previous analysis showed this version to have similar psychometric properties to the original 20-item version (35). We coded item responses so that higher scores corresponded to more severe experiences of loneliness. To account for missing item-level data, we prorated scale scores for participants who responded to at least 2 of the 3 items by summing the nonmissing item scores, dividing by the number of nonmissing items, and multiplying by the total number of items in the scale. Final scores ranged from 3 to 9. We followed the procedure of Steptoe and colleagues (36) and classified participants in the top quintile of scale scores as lonely. This procedure classified participants scoring ≥7 as lonely.

Social isolation

There is not yet a gold standard measure of exposure to social isolation. Consensus in the field is that scales should comprise multiple items and measure relationships with individuals, groups, and community organizations (37,38). We used a 6-item scale meeting these criteria first validated in the English Longitudinal Study of Aging (5,36) and adapted to the HRS (39). We assigned a social isolation score to each participant based on whether they (i) were unmarried, (ii) lived alone, (iii) had less than monthly contact with children, (iv) had less than monthly contact with other family members, (v) had less than monthly contact with friends, and (vi) did not participate monthly in any groups, clubs, or other social organizations, yielding scores 0–6. We calculated scores for participants providing data for at least 3 of the 6 items. We followed the procedure used for loneliness and classified participants in the top quintile of scale scores as socially isolated. This procedure classified participants scoring ≥3 as socially isolated.

Persistent exposure classification

For loneliness and social isolation, we classified participants with scores meeting or exceeding the threshold score at 2 or more assessment waves as having persistent experiences of loneliness or exposure to social isolation. We classified participants meeting or exceeding the threshold at only 1 assessment as having intermittent experiences of loneliness or exposure to social isolation.

Sensitivity analysis

We conducted sensitivity analysis to evaluate alternative measurements and thresholds to identify experiences of loneliness and exposure to social isolation (Supplementary Methods).

Deficits in healthy aging

Aging is the leading risk factor for many different chronic diseases and disabilities. However, not everyone experiences the onset of these conditions at the same rate. Some individuals remain free of chronic disease and maintain functioning into late life, whereas others develop chronic disease and disability much earlier (40). To understand how loneliness and social isolation relate to individual differences in healthy aging, we analyzed 3 dimensions of this process in parallel.

Mortality measures the life-span dimension of healthy aging. HRS ascertained death dates for participants from linkages with the National Death Index and from reports in exit interviews and in interviews with spouses.

Disability measures the health-span dimension of healthy aging. We measured disability from counts of activities of daily living (ADL) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) limitations. We measured ADL disability as a count of the following activities with which the participant reported having at least some difficulty: bathing, dressing, eating, getting in/out of bed, and walking across a room. We measured IADL disability as a count of the following activities with which the participant reported having at least some difficulty: using the phone, managing money, taking medications, shopping for groceries, and preparing hot meals. We analyzed counts of ADL and IADL disability as 0–3+.

Chronic disease prevalence provides a second measure of the health-span dimension of healthy aging. We measured chronic diseases as a count of aging-related chronic conditions participants reported having been diagnosed with by a physician. The conditions were: high blood pressure, diabetes, cancer, chronic lung disease, heart disease, and stroke. We analyzed counts of chronic disease diagnoses as 0–3+.

We measured biological aging from data collected in HRS’s 2016 VBS (34) using the “Phenotypic Age” algorithm (41–43). There are several methods to quantify biological aging from blood chemistry data. We focused on Phenotypic Age because comparative studies suggest this measure is more predictive of mortality, disability, and morbidity as compared to leading alternatives (42,44,45). The Phenotypic Age algorithm was developed from a machine learning analysis of mortality in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys III data set (41). The analysis screened 42 blood chemistry biomarkers and chronological age to devise a prediction algorithm. The resulting algorithm included chronological age and 9 biomarkers: albumin, alkaline phosphatase, creatinine, C-reactive protein, glucose, mean cell volume, red cell distribution width, white blood cell count, and lymphocyte percent. The algorithm produces a value denominated in the metric of years. The years correspond to the age at which an individual’s risk of death would be approximately normal in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys III sample. A phenotypic age older than a person’s true chronological age indicates more advanced biological aging.

Social and economic circumstances

We measured participants’ social and economic circumstances across 3 domains: neighborhood conditions, household wealth, and education. We measured neighborhood conditions from 2006 to 2014, household wealth from 1993 to 2016, and education at each participant’s first HRS interview. Details are reported in the Supplementary Methods.

Psychological vulnerabilities

We measured participants’ psychological vulnerabilities from assessments of the personality trait neuroticism and of symptoms of depression. We measured neuroticism at each participant’s first LBQ interview and symptoms of depression between their first HRS interview after 1992 and their first LBQ interview. Of the 11 302 participants in the analysis sample, we measured neuroticism in 11 172 participants and depressive symptoms in 11 251 participants. We excluded those with missing data from analysis. Details are reported in the Supplementary Methods.

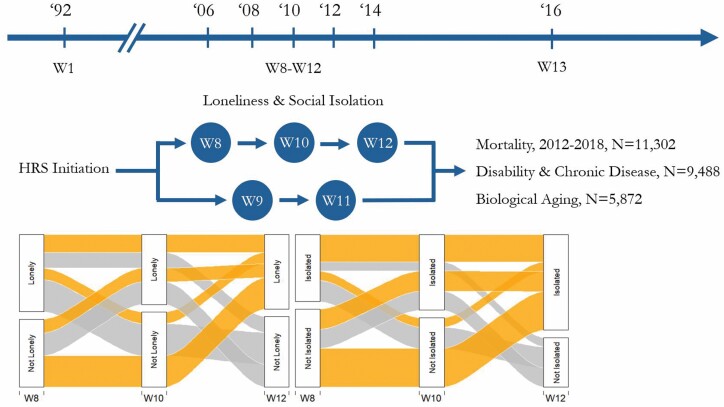

A time line of exposure and outcome assessments is provided in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Time line of assessments of loneliness, social isolation, and deficits in healthy aging. Health and Retirement Study (HRS) collected loneliness and social isolation data at every other assessment wave with half of the sample first surveyed in Wave 8 (2006) and the other half first surveyed in Wave 9 (2008). We included participants who completed at least 2 assessments of loneliness and social isolation. We classified participants who met criteria at 1 wave of measurement as “Intermittent” cases and those who met criteria at 2 or more waves of measurement as “Persistent” cases. The river plots show trajectories of loneliness and social isolation for participants who were measured at 3 time points and met criteria for loneliness or social isolation at least once during follow-up (N = 737 for loneliness; N = 961 for social isolation). The thickness of each path is indicative of the proportion of participants that followed each trajectory. For mortality, we analyzed data between the last assessment of loneliness and social isolation (Wave 11 [2012] or Wave 12 [2014]) and Wave 13 (2016). HRS collected data on death such that data recorded in Wave 13 included deaths through 2018. For analysis of disability and chronic disease, we considered prevalent and incident reports of activities of daily living (ADL) or instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) limitations and chronic disease diagnoses. For analysis of prevalent disability and disease, we used the total number of ADL or IADL limitations and chronic disease diagnoses in 2016. For analysis of incident disability and disease, we used the number of new cases of ADL or IADL limitations and chronic disease diagnoses between participants’ second assessment of loneliness and social isolation and 2016. In the incident analysis, exposure classification was based only on the first 2 assessments of loneliness and social isolation.

Statistical Analysis

Our analysis sample included participants aged 50–95 at their baseline observation for experiences of loneliness and exposure to social isolation who provided at least 2 time points of data for these measures during follow-ups from 2006 to 2014 and were alive at the end of the exposure assessment period (2012 or 2014). Disease and disability analysis included the subset of participants who had data for disease and disability outcomes in 2016, and biological aging analysis included the subset of participants included in the 2016 VBS. A comparison of participants included in these samples is reported in Supplementary Tables 1 and 2.

We tested associations of loneliness and social isolation with mortality, disability, chronic disease, and biological aging using regression methods. We analyzed time-to-event data on mortality using Cox proportional hazards regression to estimate hazard ratios (HRs). Proportional hazards assumptions were met. We analyzed count data on number of ADL and IADL disabilities and chronic disease diagnoses using negative binomial regression models to estimate incidence rate ratios (IRRs). We analyzed continuously distributed data on Phenotypic Age Advancement using linear regression to estimate standardized effect sizes (Cohen’s d). All models included covariate adjustment for age, age-squared, sex, age–sex interactions, race/ethnicity, and a dummy variable coding whether participants were assigned to the subsample of the HRS which first measured loneliness and social isolation in 2006 or 2008. Analysis was performed using Stata 15 (46).

Results

Analysis included 11 302 participants with at least 2 repeated measures of loneliness or social isolation who were aged 50–95 when they completed their first psychosocial questionnaire and were alive at the end of the exposure assessment period (2012 or 2014). Sample characteristics are reported in Supplementary Table 2. At the first waves of measurement (2006 and 2008) 10% of the sample met criteria for experiences of loneliness and 11% met criteria for exposure to social isolation. By the end of exposure assessment in 2014, the proportion that ever met criteria was 18% for loneliness and 21% for social isolation. Of those who ever met criteria for loneliness or social isolation, 20% ever met criteria for both loneliness and social isolation (Supplementary Table 3).

Ever reporting experiences of loneliness or exposure to social isolation during follow-up was more common in women as compared to men (for loneliness, risk ratio [RR] = 1.34, 95% CI [1.23–1.46]; for social isolation, RR = 1.09, [1.02–1.19]). Older participants were less likely than younger participants to report loneliness but more likely to report social isolation (a 10-year increase in age was associated with RR = 0.88, [0.84–0.92] for loneliness and RR = 1.22, [1.17–1.26] for social isolation). Similarly, White participants were less likely than non-White participants to report loneliness but more likely to report social isolation (loneliness RR = 0.76, [0.70–0.83]; social isolation RR = 1.07, [0.98–1.16]). These demographic factors were included as covariates in all analyses.

During follow-up, HRS recorded deaths for 1096 participants in our analysis sample. Participants who ever reported experiences of loneliness or exposure to social isolation during 2006–2014 were at increased risk of mortality compared to those who never reported loneliness or social isolation (for loneliness, HR = 1.48, 95% CI [1.28–1.72]; for social isolation, HR = 1.38, [1.21–1.58]).

In 2016, 19% of participants (N = 1763) reported 1 or more ADL disabilities, 18% (N = 1697) reported 1 or more IADL disabilities, and 82% (N = 7811) reported 1 or more chronic diseases. Those who ever reported experiences of loneliness or exposure to social isolation during 2006–2014 reported higher levels of all 3 outcomes as compared to those who never reported loneliness or social isolation (for loneliness, prevalent-ADL-IRR = 2.01, 95% CI [1.80–2.24], prevalent-IADL-IRR = 1.99, [1.78–2.23], prevalent-chronic disease-IRR = 1.17, [1.14–1.21]; for social isolation, prevalent-ADL-IRR = 1.63, [1.46–1.82], prevalent-IADL-IRR = 1.51, [1.35–1.69], prevalent-chronic disease-IRR = 1.11, [1.08–1.14]).

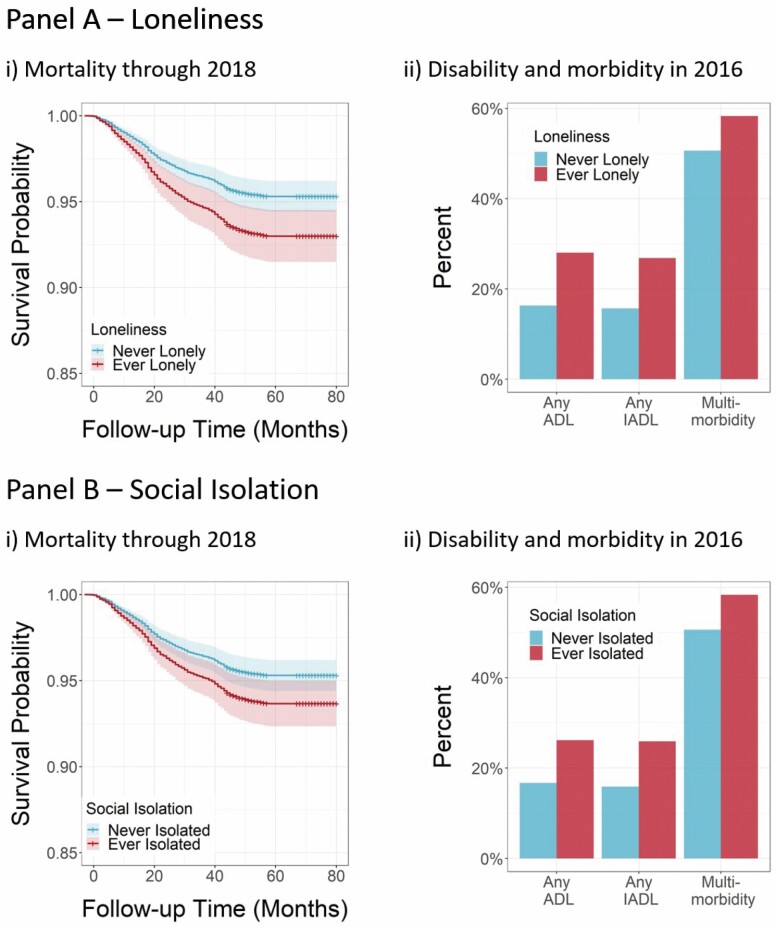

Figure 2 graphs survival proportions and percentages of participants with any disability and multimorbidity by strata of loneliness and social isolation. Effect sizes and confidence intervals are reported in Supplementary Table 4.

Figure 2.

Associations of loneliness and social isolation with deficits in healthy aging. Panels A and B show results from analysis of loneliness and social isolation, respectively. Cell (i) plots survival curves for participants who ever reported loneliness or social isolation and participants who never reported loneliness or social isolation estimated from a Cox model including covariate adjustment for age, age-squared, sex, age–sex interactions, race/ethnicity, and a dummy variable coding whether participants were assigned to the subsample of the Health and Retirement Study (HRS) which first measured loneliness and social isolation in 2006 or 2008. Shaded areas show 95% confidence intervals. Cell (ii) plots the percent of participants reporting any activities of daily living (ADL) limitations, any instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) limitations, and multimorbidity (ie, 2 or more chronic disease diagnoses) among participants who ever reported loneliness or social isolation and participants who never reported loneliness or social isolation.

Disentangling Effects of Loneliness and Social Isolation on Deficits in Healthy Aging From the Effects of Correlated Risk Factors

Experiences of loneliness and exposure to social isolation are not randomly distributed throughout the population. Poorer social and economic circumstances and psychological vulnerabilities may put individuals at greater risk for loneliness and social isolation and increase risk for deficits in healthy aging. We therefore repeated our analysis adding covariate adjustment to account for these correlated risk factors. This analysis evaluated confounding of associations between social connectedness and deficits in healthy aging by risk factors present from earlier in life.

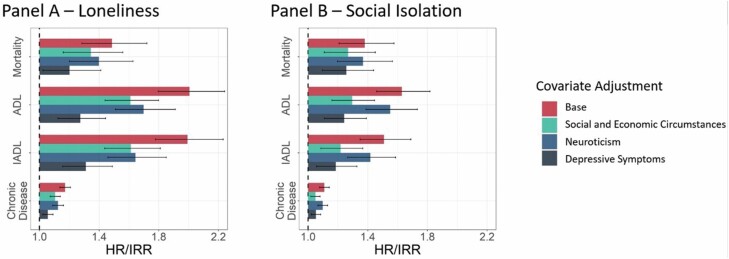

We measured participants’ social and economic circumstances from their reports about neighborhood social cohesion and physical disorder, household wealth, and educational attainment. Those from poorer social and economic circumstances more often reported loneliness and social isolation (Supplementary Table 5). Social and economic circumstances accounted for some but not all of the associations of loneliness and social isolation with deficits in healthy aging. Covariate adjustment for social and economic circumstances attenuated associations of loneliness and social isolation with all outcomes by 25%–37% and 27%–53%, respectively (Figure 3 and Supplementary Table 4).

Figure 3.

Effect sizes for associations of loneliness and social isolation with deficits in healthy aging, with adjustment for social and economic circumstances and psychological vulnerabilities. Panels A and B show results from analysis of loneliness and social isolation, respectively, across different covariate adjusted models. The base model included covariate adjustment for age, age-squared, sex, age–sex interactions, race/ethnicity, and a dummy variable coding whether participants were assigned to the subsample of the Health and Retirement Study (HRS) which first measured loneliness and social isolation in 2006 or 2008. The additional models included these covariates as well as a composite score for social and economic circumstances, a measure of the personality trait neuroticism, and a depressive symptom score. Social and economic circumstances were measured from longitudinal data across all waves of loneliness/social isolation assessment. Neuroticism was measured at the time of the first loneliness/social isolation assessment. Depressive symptoms were measured from 1994—the time of the first loneliness/social isolation assessment. Plots show effect sizes for analysis of mortality (hazard ratios [HRs]) and disability and chronic disease (incidence rate ratios [IRRs]), comparing those who ever reported loneliness or social isolation to those who never reported loneliness or social isolation. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. ADL = activities of daily living; IADL = instrumental activities of daily living.

We measured psychological vulnerabilities from baseline reports of the personality trait neuroticism and depressive symptoms. Participants with more psychological vulnerabilities at baseline more often reported loneliness and social isolation (Supplementary Table 5). Psychological vulnerabilities accounted for some but not all of the associations of loneliness and social isolation with deficits in healthy aging. Covariate adjustment for baseline levels of neuroticism attenuated associations of loneliness and social isolation with all outcomes by 15%–28% and 3%–15%, respectively. Covariate adjustment for baseline depressive symptoms attenuated associations of loneliness and social isolation with all outcomes by 54%–66% and 29%–59%, respectively (Figure 3 and Supplementary Table 4).

As a further analysis to address confounding by factors that could influence both social connectedness and healthy aging but that were not measured by the HRS, we used fixed-effects regression to test associations of changes in loneliness and social isolation with changes in deficits in healthy aging. Fixed-effects analysis blocks confounding by time-invariant characteristics of individuals that may contribute to both loneliness and social isolation and deficits in healthy aging. We analyzed 3 deficits in healthy aging with repeated measures in the HRS: ADLs, IADLs, and chronic diseases. Effect sizes were similar to effect sizes from covariate adjusted regression models (Supplementary Table 6).

Testing Loneliness and Social Isolation as Precursors to Deficits in Healthy Aging

We measured experiences of loneliness and exposure to social isolation prior to the assessment of deficits in healthy aging. However, this prospective design does not rule out the possibility that prior disability and disease might cause loneliness and social isolation. To refine our inference, we limited our measurement of loneliness and social isolation to the first 2 assessments and conducted analysis of incident disability and chronic disease during the interval between the second assessment of loneliness and social isolation and follow-up in 2016. We included all participants from the main analysis, regardless of whether they were free of any disability or disease at baseline. During follow-up of 2–6 years, 13% of participants (N = 1219) reported 1 or more incident ADL disabilities, 13% (N = 1235) reported 1 or more incident IADL disabilities, and 24% (N = 2266) reported 1 or more incident chronic diseases (Supplementary Figure 1).

Participants who reported loneliness and social isolation during the first 2 psychosocial questionnaires had higher incidence of ADL and IADL disabilities in 2016 (for loneliness, incident-ADL-IRR = 1.64, 95% CI [1.41–1.91], incident-IADL-IRR = 1.57, [1.35–1.83]; for social isolation, incident-ADL-IRR = 1.35, [1.16–1.57], incident-IADL-IRR = 1.32, [1.15–1.53]). Incidence of chronic disease did not differ between participants who reported loneliness and social isolation and those who did not (for loneliness, IRR = 1.02, [0.91–1.13]; for social isolation, IRR = 0.99, [0.89–1.09]). Effect sizes are reported in Supplementary Table 7 and graphed in Supplementary Figure 1.

Comparing Intermittent and Persistent Exposure Phenotypes

Of participants who ever met criteria for loneliness during follow-up between 2006 and 2014, 32% met criteria at multiple assessment waves. We classified these participants as persistently experiencing loneliness (6% of the sample) and the remainder as intermittently experiencing loneliness (12% of the sample). Of participants who ever met criteria for social isolation during follow-up, we classified 37% as persistently exposed to social isolation (8% of the sample) and the remainder as intermittently exposed to social isolation (13% of the sample).

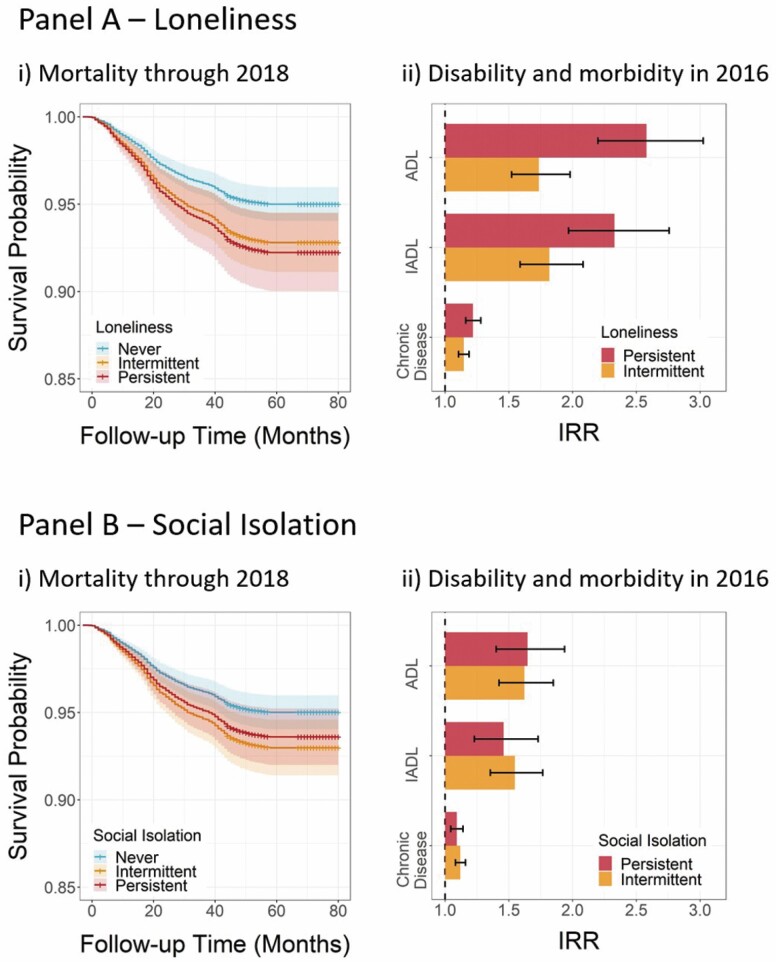

Participants with persistent experiences of loneliness were at increased risk for mortality through 2018 compared to participants with intermittent experiences of loneliness (persistent-loneliness-HR = 1.57, 95% CI [1.24–1.99] as compared to intermittent-loneliness-HR = 1.45, [1.22–1.72]). In parallel, those with persistent loneliness were at increased risk for prevalent disability and chronic disease (for prevalent ADL disability, persistent-loneliness-IRR = 2.57, [2.19–3.02] as compared to intermittent-loneliness-IRR = 1.75, [1.53–1.99]; for prevalent IADL disability, persistent-loneliness-IRR = 2.34, [1.98–2.77] as compared to intermittent-loneliness-IRR = 1.83, [1.60–2.10]; for prevalent chronic disease, persistent-loneliness-IRR = 1.22, [1.16–1.28] as compared to intermittent-loneliness-IRR = 1.15, [1.11–1.19]). Effect sizes are graphed in Figure 4 and reported in Supplementary Table 8.

Figure 4.

Associations of intermittent and persistent loneliness and social isolation with deficits in healthy aging. Panels A and B show results from analysis of loneliness and social isolation, respectively. Cell (i) plots Kaplan–Meier survival curves for participants who reported persistent loneliness or social isolation, participants who reported intermittent loneliness or social isolation, and participants who never reported loneliness or social isolation. Shaded areas show 95% confidence intervals. Cell (ii) plots effect sizes for analysis of incident activities of daily living (ADL) disability, instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) disability, and chronic disease (incidence rate ratios [IRRs]), comparing those who reported persistent loneliness or social isolation to those who never reported loneliness or social isolation and those who reported intermittent loneliness or social isolation to those who never reported loneliness or social isolation. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

In contrast to results for loneliness, we did not find evidence that participants who were persistently exposed to social isolation were at greater risk for any deficits in healthy aging as compared to participants who were intermittently exposed to social isolation (for mortality, persistent-isolation-HR = 1.28, 95% CI [1.04–1.56] as compared to intermittent-isolation-HR = 1.44, [1.23–1.68]; for prevalent ADL disability, persistent-isolation-IRR = 1.65, [1.40–1.94] as compared to intermittent-isolation-IRR = 1.62, [1.42–1.85]; for prevalent IADL disability, persistent-isolation-IRR = 1.46, [1.23–1.73] as compared to intermittent-isolation-IRR = 1.54, [1.35–1.76]; for prevalent chronic disease, persistent-isolation-IRR = 1.09, [1.04–1.14] as compared to intermittent-isolation-IRR = 1.12, [1.08–1.16]). Effect sizes are graphed in Figure 4 and reported in Supplementary Table 8.

Evaluating Biological Aging as a Potential Mechanism Linking Loneliness and Social Isolation to Deficits in Healthy Aging

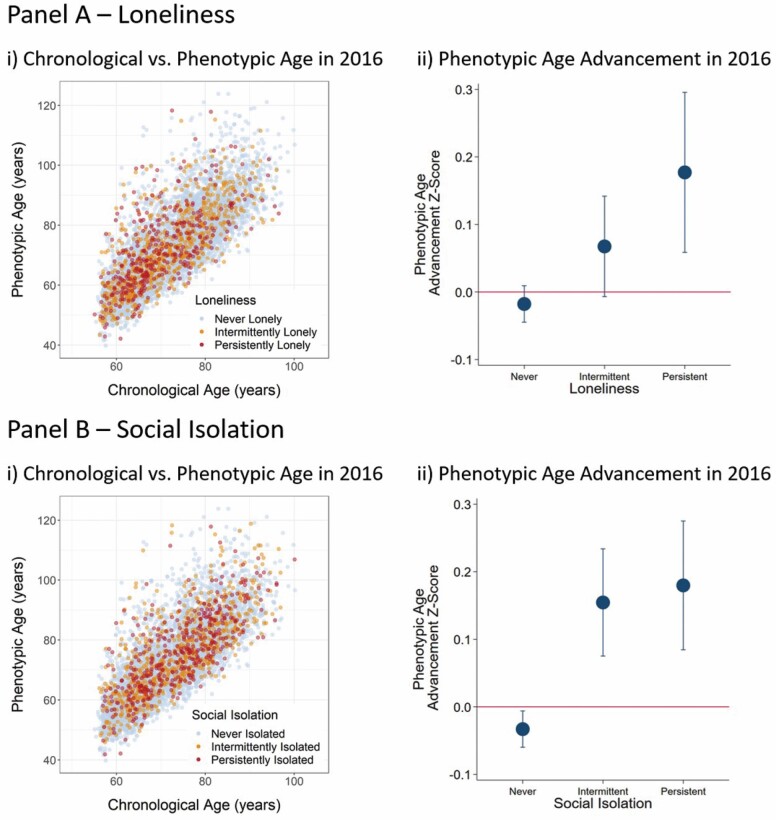

We measured participants’ biological aging using the Phenotypic Age algorithm (41–43). As reported previously (47), participants’ Phenotypic Ages were highly correlated with their chronological ages (r = 0.76). In our analysis sample (N = 5872), participants’ Phenotypic Ages were, on average, 0.50 years (SD = 8.54) older than their chronological ages, indicating that participants’ aging was similar to the expectation based on the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys reference sample in which the Phenotypic Age algorithm was developed. Participants who reported more experiences of loneliness exhibited more advanced biological aging (persistent-loneliness-d = 0.26, 95% CI [0.14–0.39] as compared to intermittent-loneliness-d = 0.12, [0.04–0.20]). For social isolation, participants with any exposure tended to have more advanced biological aging as compared to those never exposed, but there was no evidence of increased risk due to persistent exposure (persistent-isolation-d = 0.21, [0.11–0.31] as compared to intermittent-isolation-d = 0.19, [0.10–0.27]). The relationships between chronological age and phenotypic age and plots of average Phenotypic Age Advancement across strata of persistence are shown in Figure 5. Effect sizes are reported in Supplementary Table 8.

Figure 5.

Associations of loneliness and social isolation with biological aging, by levels of loneliness and social isolation persistence. Panels A and B show results from analysis of loneliness and social isolation, respectively. Cell (i) shows a scatter plot of chronological age versus Phenotypic Age for participants who reported persistent loneliness or social isolation (red), participants who reported intermittent loneliness or social isolation (orange), and participants who never reported loneliness or social isolation (blue). Cell (ii) shows mean Phenotypic Age Advancement (Phenotypic Age − chronological age) for participants exposed to loneliness and social isolation across the strata of Never, Intermittent, and Persistent loneliness and isolation. Phenotypic Age Advancement values are plotted as z-scores (M = 0, SD = 1). Error bars show 95% confidence intervals.

Sensitivity Analysis

We conducted sensitivity analyses. First, to test if our findings depended on our measures of experiences of loneliness and exposure to social isolation, we repeated analysis using alternative codings of the 3-item Revised UCLA Loneliness Scale and the 6-item Social Isolation scale as well as alternative measures of social isolation. We also repeated analysis using continuous loneliness and social isolation scores. The results from this sensitivity analysis were generally the same as the results from the main analysis. Results are reported in Supplementary Table 7 and Supplementary Figure 2.

Second, because our analysis sample included a large chronological age range, we compared findings in a younger subset of the sample (age 50–64) to the older subset of the sample (age 65–95). Results were similar in both groups although effect sizes were somewhat larger for the younger subset. Results are reported in Supplementary Table 9.

Third, the group of participants identified as having intermittent experiences of loneliness and exposure to social isolation varied in the timing of their experiences and exposures relative to outcome assessment. Among those who were intermittently lonely or socially isolated, we compared findings for those who were last lonely or socially isolated at their most recent assessment wave and those who were last lonely or socially isolated at earlier assessment waves. Results are reported in Supplementary Table 10.

Discussion

We tested how older adults’ experiences of loneliness and exposure to social isolation were related to deficits in healthy aging using longitudinal, repeated-measures data from the HRS. We measured loneliness and social isolation during 2006–2014 and analyzed health outcomes in 2016 and mortality through 2018. Findings add to knowledge about relationships of loneliness and social isolation with deficits in healthy aging in 4 ways.

First, experiences of loneliness and exposure to social isolation are associated with deficits in healthy aging, and these associations are partly but not fully explained by correlated social and economic circumstances and psychological vulnerabilities that make loneliness and social isolation more likely. This result points to the centrality of social and economic circumstances to healthy aging. It also highlights the challenge of disentangling loneliness and social isolation from mental health symptoms that may be both causes and consequences of deficits in social connectedness. Second, analysis of incident disability and chronic disease ruled out reverse causation as an explanation for the associations of loneliness and social isolation with disability but not in the case of chronic disease. Third, older adults with persistent experiences of loneliness suffered more severe deficits in healthy aging as compared to those with intermittent experiences of loneliness. In contrast, we found no evidence for a similar increased risk due to persistence in the case of exposure to social isolation. Fourth, associations of loneliness and social isolation with deficits in healthy aging were related to an overall process of biological aging. Previous studies have linked loneliness and social isolation with dysregulation of the immune system (30), and our findings suggest that the biology of the relationships of loneliness and social isolation with deficits in healthy aging may encompass quantifiable declines across multiple physiological systems.

These findings must be interpreted within the context of limitations. The measures of experiences of loneliness and exposure to social isolation used in our analysis are imprecise and are not parallel in what they capture. There are no current gold standard measures for the constructs we studied. Misclassification is possible. We used measurements validated within the HRS and its sister-study English Longitudinal Study of Aging, the 3-item Revised UCLA Loneliness Scale (35), and the 6-item Social Isolation scale (5,36,39). Sensitivity analysis using alternative measures of loneliness and social isolation yielded results similar to those reported in the main analysis (see Supplementary Methods, Supplementary Table 7, and Supplementary Figure 2). Loneliness and social isolation were first assessed in the HRS in 2006 and assessment occurred at every other measurement wave. Most participants had only 2 or 3 repeated measures. Classification of persistence may change with additional follow-up. In parallel, there is no gold standard measure of aging. We analyzed deficits in healthy aging using a combination of mortality records, self-reported disability and chronic disease diagnosis data, and a clinical-biomarker-assessed measure of biological aging. Consistent findings across these outcomes bolster confidence in our conclusions. Follow-up time was limited. We were only able to analyze biological aging at a single time point. For analysis of incident disability and disease, prospective follow-up extended at most 6 years. Continued waves of HRS follow-up will allow for repeated-measures analysis of biological aging and longer follow-up of incident disability and disease outcomes. Experiences of loneliness and exposure to social isolation may be culturally dependent. Our study was based in the United States, and findings may not be transportable to other settings around the world. Strengths of our study include a longitudinal repeated-measures design, analysis of a large national sample of older adults with measurements of loneliness, social isolation, multiple healthy aging endpoints, and key confounding and mediating factors.

Within the context of these limitations, our findings have implications for research related to loneliness, social isolation, and healthy aging and potentially for public health practice. For research, our findings have 3 implications. First, better understanding is needed about how and for whom exposure to social isolation results in experiences of loneliness. In alignment with previous research (5,48), not all individuals in the HRS who reported exposure to social isolation also reported experiences of loneliness. An identification of unique types and characteristics of social relationships that link social isolation to loneliness may inform future interventions and allow for more targeted efforts. Additionally, current measures of loneliness and social isolation are crude, and improved measures may better capture the relationship between those who are isolated and those who are lonely. Second, our findings highlight overlap between the effects of histories of depressive symptoms and the effects of loneliness and social isolation. Future studies should build upon previous efforts to investigate the shared etiology of depression and loneliness, for example, through analysis of the shared genetic basis for these conditions (49). Our findings also highlight continued need for longitudinal repeated-measures studies to disentangle the reciprocal nature of causation between depression and loneliness (17,50). Third, the observation that associations of loneliness and social isolation with mortality, disability, and morbidity were also reflected in an advanced state of biological aging suggests the possibility that methods to quantify biological aging, such as the Phenotypic Age algorithm used in this study, may provide sensitive endpoints for intervention trials. In our study, disease incidence over up to 6 years was unrelated to loneliness or social isolation. Thus, timescales for most intervention follow-up may not be sufficient to detect impact on disease risk. Because methods to quantify biological aging focus on changes that precede disease onset, they may be more sensitive to near-term biological changes resulting from enhanced social connectedness.

For public health practice, our findings amplify prior work identifying experiences of loneliness as the proximate determinant of deficits in healthy aging. Proposed interventions aim to improve health outcomes by reducing the length of experiences of loneliness and exposure to social isolation (13). In our analysis, a less-persistent phenotype was associated with reduced risk only in the case of loneliness. Deficits in healthy aging associated with social isolation were similar across levels of persistence, raising the possibility that interventions reducing length of exposure to social isolation without directly affecting experiences of loneliness may not improve health outcomes.

Our overall findings support a relationship of experiences of loneliness and exposure to social isolation with deficits in healthy aging and provide further motivation for intervention trials. They nevertheless highlight 2 enduring challenges facing research to understand the public health impacts of loneliness and social isolation and efforts to design effective interventions: First, deficits in healthy aging are more concentrated in those individuals who experience persistent deficits in social connectedness. But these individuals represent a minority of the overall population experiencing loneliness or being exposed to social isolation at any given point in time. Longitudinal phenotyping will be important for advancing understanding of etiology and impact. Second, liability to experiences of loneliness and exposure to social isolation is variable in the population and risk is greater in those with few socioeconomic resources and who struggle with mental health problems. Tailoring interventions to meet the needs of these vulnerable populations will be critical.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Linda P. Fried and to the Psychiatric Epidemiology Training Program at the Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health for feedback on earlier drafts of this manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Robert N. Butler Columbia Aging Center, Russel Sage Foundation (grant 1810-08987), and the Jacobs Foundation. C.L.C. is supported by a fellowship from the National Institute of Mental Health (5T32MH013043).

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

Author Contributions

The study was designed by D.W.B. and C.L.C. C.L.C. conducted all analyses with supervision from D.W.B. and support from G.H.G. and D.K. C.L.C. and D.W.B. wrote the paper. All authors contributed critical feedback related to study design and execution and to manuscript preparation and revision.

References

- 1. Cudjoe TKM, Roth DL, Szanton SL, Wolff JL, Boyd CM, Thorpe RJ. The epidemiology of social isolation: National Health and Aging Trends Study. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2020;75:107–113. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gby037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ong AD, Uchino BN, Wethington E. Loneliness and health in older adults: a mini-review and synthesis. Gerontology. 2016;62:443–449. doi: 10.1159/000441651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Luo Y, Hawkley LC, Waite LJ, Cacioppo JT. Loneliness, health, and mortality in old age: a national longitudinal study. Soc Sci Med. 2012;74:907–914. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.11.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Petitte T, Mallow J, Barnes E, Petrone A, Barr T, Theeke L. A systematic review of loneliness and common chronic physical conditions in adults. Open Psychol J. 2015;8(suppl 2):113–132. doi: 10.2174/1874350101508010113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Shankar A, McMunn A, Banks J, Steptoe A. Loneliness, social isolation, and behavioral and biological health indicators in older adults. Health Psychol. 2011;30:377–385. doi: 10.1037/a0022826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hawkley LC, Cacioppo JT. Loneliness matters: a theoretical and empirical review of consequences and mechanisms. Ann Behav Med. 2010;40:218–227. doi: 10.1007/s12160-010-9210-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Holt-Lunstad J, Smith TB, Baker M, Harris T, Stephenson D. Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for mortality: a meta-analytic review. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2015;10:227–237. doi: 10.1177/1745691614568352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Blazer D. Social isolation and loneliness in older adults—a mental health/public health challenge. JAMA Psychiatry. 2020;77:990–991. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.1054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fried L, Prohaska T, Burholt V, et al. A unified approach to loneliness. Lancet. 2020;395:114. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32533-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. McGinty EE, Presskreischer R, Han H, Barry CL. Psychological distress and loneliness reported by US adults in 2018 and April 2020. JAMA. 2020;324:93–94. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.9740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Murthy VH. Together: The Healing Power of Human Connection in a Sometimes Lonely World. HarperCollins; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 12. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Social Isolation and Loneliness in Older Adults: Opportunities for the Health Care System. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2020. doi: 10.17226/25663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gardiner C, Geldenhuys G, Gott M. Interventions to reduce social isolation and loneliness among older people: an integrative review. Health Soc Care Community. 2018;26:147–157. doi: 10.1111/hsc.12367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hawkley LC, Wroblewski K, Kaiser T, Luhmann M, Schumm LP. Are U.S. older adults getting lonelier? Age, period, and cohort differences. Psychol Aging. 2019;34:1144–1157. doi: 10.1037/pag0000365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cacioppo JT, Cacioppo S. The growing problem of loneliness. Lancet. 2018;391:426. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30142-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Yanguas J, Pinazo-Henandis S, Tarazona-Santabalbina FJ. The complexity of loneliness. Acta Biomed. 2018;89:302–314. doi: 10.23750/abm.v89i2.7404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Courtin E, Knapp M. Social isolation, loneliness and health in old age: a scoping review. Health Soc Care Community. 2017;25:799–812. doi: 10.1111/hsc.12311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Simonsick EM, Kasper JD, Phillips CL. Physical disability and social interaction: factors associated with low social contact and home confinement in disabled older women (The Women’s Health and Aging Study). J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 1998;53:S209–S217. doi: 10.1093/geronb/53b.4.s209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lewis TT, Sutton-Tyrrell K, Penninx BW, et al. Race, psychosocial factors, and aortic pulse wave velocity: the Health, Aging, and Body Composition Study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2010;65:1079–1085. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glq089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Eckhard J. Does poverty increase the risk of social isolation? Insights based on panel data from Germany. Sociol Q. 2018;59(2):338–359. doi: 10.1080/00380253.2018.1436943 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Portacolone E, Perissinotto C, Yeh JC, Greysen SR. “I Feel Trapped”: the tension between personal and structural factors of social isolation and the desire for social integration among older residents of a high-crime neighborhood. Gerontologist. 2018;58:79–88. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnw268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Yao L, Robert SA. The contributions of race, individual socioeconomic status, and neighborhood socioeconomic context on the self-rated health trajectories and mortality of older adults. Res Aging. 2008;30(2):251–273. doi: 10.1177/0164027507311155 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Graham EK, Rutsohn JP, Turiano NA, et al. Personality predicts mortality risk: an integrative data analysis of 15 international longitudinal studies. J Res Pers. 2017;70:174–186. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2017.07.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lahey BB. Public health significance of neuroticism. Am Psychol. 2009;64:241–256. doi: 10.1037/a0015309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Rodda J, Walker Z, Carter J. Depression in older adults. BMJ. 2011;343:d5219. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d5219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Schutter N, Koorevaar L, Holwerda TJ, Stek ML, Dekker J, Comijs HC. ‘Big Five’ personality characteristics are associated with loneliness but not with social network size in older adults, irrespective of depression. Int Psychogeriatr. 2020;32:53–63. doi: 10.1017/S1041610219000231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Valtorta NK, Kanaan M, Gilbody S, Ronzi S, Hanratty B. Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for coronary heart disease and stroke: systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal observational studies. Heart. 2016;102:1009–1016. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2015-308790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Perissinotto CM, Stijacic Cenzer I, Covinsky KE. Loneliness in older persons: a predictor of functional decline and death. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:1078–1083. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.1993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ferrucci L, Gonzalez-Freire M, Fabbri E, et al. Measuring biological aging in humans: a quest. Aging Cell. 2020;19:e13080. doi: 10.1111/acel.13080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Cacioppo JT, Cacioppo S. Social relationships and health: the toxic effects of perceived social isolation. Soc Personal Psychol Compass. 2014;8:58–72. doi: 10.1111/spc3.12087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kennedy BK, Berger SL, Brunet A, et al. Geroscience: linking aging to chronic disease. Cell. 2014;159:709–713. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.10.039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bugliari D, Campbell N, Chan C, et al. RAND HRS Longitudinal File 2016 (V1) Documentation. Published online June 2019. https://www.rand.org/well-being/social-and-behavioral-policy/centers/aging/dataprod/hrs-data.html. Accessed July 6, 2020.

- 33. Smith J, Ryan L, Fisher G, et al. HRS Psychosocial and Lifestyle Questionnaire 2006–2016. Published online July 2017. https://hrs.isr.umich.edu/publications/biblio/9066. Accessed October 29, 2019.

- 34. Crimmins E, Faul J, Thyagarajan B, Weir D. Venous Blood Collection and Assay Protocol in the 2016 Health and Retirement Study. Published online December 2017. https://hrs.isr.umich.edu/publications/biblio/9065. Accessed October 29, 2019.

- 35. Hughes ME, Waite LJ, Hawkley LC, Cacioppo JT. A short scale for measuring loneliness in large surveys: results from two population-based studies. Res Aging. 2004;26:655–672. doi: 10.1177/0164027504268574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Steptoe A, Shankar A, Demakakos P, Wardle J. Social isolation, loneliness, and all-cause mortality in older men and women. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:5797–5801. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1219686110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Cornwell EY, Waite LJ. Social disconnectedness, perceived isolation, and health among older adults. J Health Soc Behav. 2009;50:31–48. doi: 10.1177/002214650905000103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Zavaleta D, Samuel K, Mills CT. Measures of social isolation. Soc Indic Res. 2017;131(1):367–391. doi: 10.1007/s11205-016-1252-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Coyle C. The Effects of Loneliness and Social Isolation on Hypertension in Later Life: Including Risk, Diagnosis and Management of the Chronic Condition [Grad Dr Diss.]. Published online June 1, 2014. https://scholarworks.umb.edu/doctoral_dissertations/174. Accessed October 19, 2019.

- 40. Leveille SG, Fried LP, McMullen W, Guralnik JM. Advancing the taxonomy of disability in older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2004;59:86–93. doi: 10.1093/gerona/59.1.m86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Levine ME, Lu AT, Quach A, et al. An epigenetic biomarker of aging for lifespan and healthspan. Aging. 2018;10:573–591. doi: 10.18632/aging.101414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Liu Z, Kuo PL, Horvath S, Crimmins E, Ferrucci L, Levine M. A new aging measure captures morbidity and mortality risk across diverse subpopulations from NHANES IV: a cohort study. PLoS Med. 2018;15:e1002718. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Liu Z, Kuo PL, Horvath S, Crimmins E, Ferrucci L, Levine M. Correction: a new aging measure captures morbidity and mortality risk across diverse subpopulations from NHANES IV: a cohort study. PLoS Med. 2019;16:e1002760. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Hastings WJ, Shalev I, Belsky DW. Comparability of biological aging measures in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Study, 1999–2002. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2019;106:171–178. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2019.03.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Parker DC, Bartlett BN, Cohen HJ, et al. Association of blood chemistry quantifications of biological aging with disability and mortality in older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2020;75:1671–1679. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glz219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 15. StataCorp LLC; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Liu Z, Chen X, Gill TM, Ma C, Crimmins EM, Levine ME. Associations of genetics, behaviors, and life course circumstances with a novel aging and healthspan measure: evidence from the Health and Retirement Study. PLoS Med. 2019;16(6). doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Coyle CE, Dugan E. Social isolation, loneliness and health among older adults. J Aging Health. 2012;24:1346–1363. doi: 10.1177/0898264312460275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Matthews T, Danese A, Wertz J, et al. Social isolation, loneliness and depression in young adulthood: a behavioural genetic analysis. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2016;51:339–348. doi: 10.1007/s00127-016-1178-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Cacioppo JT, Hawkley LC, Thisted RA. Perceived social isolation makes me sad: 5-year cross-lagged analyses of loneliness and depressive symptomatology in the Chicago Health, Aging, and Social Relations Study. Psychol Aging. 2010;25:453–463. doi: 10.1037/a0017216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.