Abstract

The concept of the exposome was introduced over 15 years ago to reflect the important role that the environment exerts on health and disease. While originally viewed as a call-to-arms to develop more comprehensive exposure assessment methods applicable at the individual level and throughout the life course, the scope of the exposome has now expanded to include the associated biological response. In order to explore these concepts, a workshop was hosted by the Gunma University Initiative for Advanced Research (GIAR, Japan) to discuss the scope of exposomics from an international and multidisciplinary perspective. This Global Perspective is a summary of the discussions with emphasis on (1) top-down, bottom-up, and functional approaches to exposomics, (2) the need for integration and standardization of LC- and GC-based high-resolution mass spectrometry methods for untargeted exposome analyses, (3) the design of an exposomics study, (4) the requirement for open science workflows including mass spectral libraries and public databases, (5) the necessity for large investments in mass spectrometry infrastructure in order to sequence the exposome, and (6) the role of the exposome in precision medicine and nutrition to create personalized environmental exposure profiles. Recommendations are made on key issues to encourage continued advancement and cooperation in exposomics.

Introduction

As early as the 18th century, it was demonstrated that environmental exposures increase risks of chronic human disease.1 Public awareness for this idea grew in the 1950s when causal links were reported between smoking and lung cancer.2 Soon afterward, Rachel Carson’s “Silent Spring” raised concerns about the adverse health consequences of synthetic organic chemical exposures,3 thus motivating establishment of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and many new funding avenues for research into the occurrence and health consequences of environmental contaminant exposures. The Environmental Science and Technology (ES&T) journal has communicated such research to an international audience since 1969.4 However, while myriad environmental exposures have since been discovered—of which only a few hundred have been studied for disease risks—the underlying methods of exposure assessment and environmental epidemiology have remained remarkably static. There has been a shift from occupational studies of workplace exposures to population-based environmental studies to research on multiple factors (e.g., age specific vulnerability) and low dose effects. However, epidemiology studies still tend to focus on single chemicals or a handful of related chemicals (e.g., phthalates), rather than real-world mixtures.

Environmental monitoring and human biomonitoring have historically been hypothesis driven, addressing environmental contaminants one at a time. Today, thousands of targeted analytical methods exist for the accurate measurement of contaminants in biofluids, food, air, drinking water, and soil. Nonetheless, each method tends to be applied to only a small number of chemicals having similar properties or structures.5−7 The health risks of single chemical exposures, or the sum of chemicals within a related chemical class (e.g., polychlorinated dioxins8), are estimated by comparison of measured levels to dose–response relationships derived from animal studies, which are also conducted one chemical at a time. In environmental epidemiology, associations between single chemicals or chemical mixtures are investigated over a wide range of exposures to strengthen causal inference.9,10 Although these chemical-by-chemical approaches are valuable for confirming a priori hypotheses, they are unsuited for discovering health effects that arise from the vast majority of still unknown exposures not yet measured in environmental media or biospecimens. The exposome concept addresses this issue, in part through more comprehensive or unbiased exposure measurements; however, because the number of chemicals we can measure is now so large, studies need to be designed differently to avoid promoting false positive findings.

The practical limitations of targeted exposure-effect studies are obvious. A recent review of chemicals in commerce identified more than 350,000 chemicals that are registered for production and use.11 The number of synthetic chemicals that comprise real-world exposures is even greater because chemicals in commerce may be complex mixtures or contain isomers and impurities, and many are transformed in humans or by microbes in the body (i.e., the microbiome) or in the environment (e.g., methylmercury) to a multitude of degradation products. Beyond exposure to commercial chemicals, we breathe, drink, and eat complex mixtures of pollutants from anthropogenic emissions to air and water, and even the cooking of food introduces potentially carcinogenic byproducts.12 In addition, the greatest intake of the chemical exposome is through diet, a massive contributor to the exogenous biochemical load, consisting of thousands of natural or anthropogenic chemicals that impact our endogenous metabolism and fine-tune risk of diseases.13−15 Natural substances in food, air, and water may affect health directly16,17 but may also interact with effects posed by environmental contaminants.18 In addition, environmental exposures to nonchemical stressors, including noise, light, social, and socioeconomic factors and green space and climate, affect biological responses and may also interact with chemical exposures.19−21 Additional complications arise from variability in exposures and effects due to changing locations, age, lifestyle, diet, sex, ethnicity, and health status.22−24

The complex milieu of real-world exposures highlights the limitations of targeted methods for exploring causes of disease. Moreover, experimental and observational studies evaluating adverse effects typically focus on doses or exposures to a single chemical, which is quite different from those presented by mixtures,25,26 and unmeasured coexposures can confound results of targeted studies.27,28 Among the largest systematic human biomonitoring programs in North America and Europe (NHANES29 and HBM4 EU,30 respectively), only ∼300 chemicals are routinely analyzed by targeted methods in human biofluids. Moreover, owing to limitations of the sample volume needed, this list of chemicals has never been measured collectively in a single individual. Accordingly, cumulative environmental chemical exposures and their effects are still poorly understood in population studies.

The “exposome” was first proposed as a research priority ∼15 years ago to recognize the important roles that environment plays in cancer (and by extension other chronic diseases).31 The concept was motivated by recognition that the genome alone explained only a small proportion of the population variance of chronic disease in developed countries.32,33 The exposome was intended to represent everything that the genome did not, and if it could be adequately characterized in sufficient numbers of people throughout their life course, it promises to reveal nongenetic causes of disease and gene–environment interactions (i.e., genome × exposome interactions).34−37 Although there has been a call to “sequence the exposome”,38 there is currently no agreement as to how this could be accomplished.39 Acquiring data for all exposures is one obstacle, but linking such data to health information brings additional challenges. Nonetheless, the number of publications using the term exposome is increasing exponentially, and granting agencies are beginning to provide support for large exposome studies.40−43

In order to discuss the exposome and its collective challenges, the second International Exposome Symposium of the Gunma University Initiative for Advanced Research (GIAR) was organized. Speakers were invited from Europe, North America, and Japan with a range of expertise in the areas of medicine, epidemiology, data science, environmental toxicology, analytical chemistry, and food science (Figure S1). This article summarizes and integrates the presentations and subsequent discussions with respect to (1) defining terminology and the scope of the exposome, (2) considerations in designing exposome studies, (3) characterizing the exposome via high-resolution mass spectrometry, (4) developing computational strategies for exposomics data, (5) producing databases for exposures and exposure-disease relationships, and (6) predicting roles of exposomics in precision medicine and precision nutrition.

Scope of the Exposome

For the exposome to achieve widespread adoption, multiple disciplines will need to work together, including environmental scientists, social scientists, analytical chemists, molecular biologists, toxicologists, epidemiologists, and physicians. Unlike DNA sequencing, where a common technology can accurately and reproducibly characterize an individual’s genome, the exposome is highly dynamic in time and space and requires a range of tools to measure it. Furthermore, effects of exposure are complicated by the quantal nature of dose–response relationships within a population, where individual responses vary with exposure history, age, age at exposure, genetics, and coexposures. As a result, an individual’s exposome tends to be defined by the analytical and methodological approaches used in a given study.20

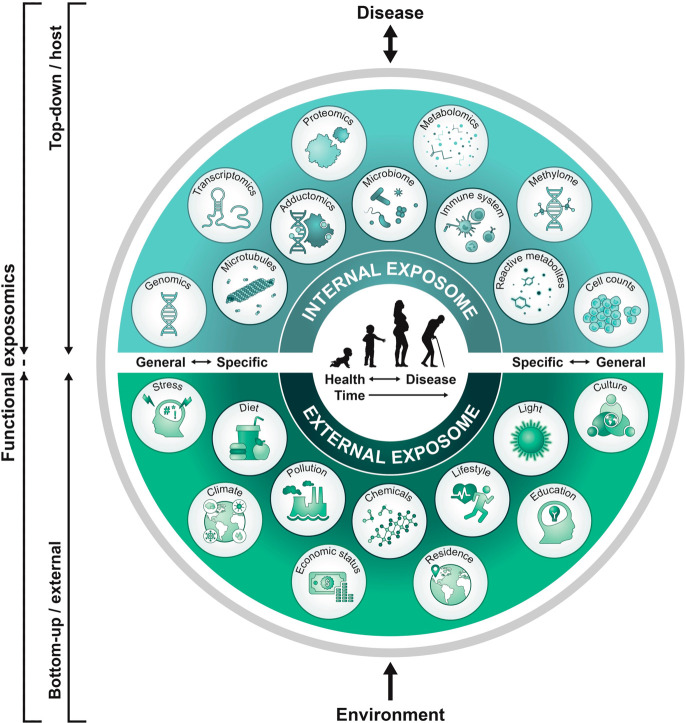

Since the original conceptualization of the exposome, the definition has evolved to incorporate omics technologies that can be harnessed to characterize exposures.44 The exposome was originally envisioned in 2005 from Dr. Christopher Wild’s perspective as a cancer epidemiologist as “. . .encompassing life-course environmental exposures from the prenatal period onwards”.31 Here, the emphasis was on improving exposure characterization to find causes of disease that moved beyond traditional approaches of individual targeted exposures. A few years later, Rappaport and Smith considered two exposomics approaches for finding causal human exposures.45,46 The bottom-up approach that would characterize chemicals in environmental media (e.g., air, water, diet, the built environment) and the top-down approach that would focus on chemicals measured in biospecimens (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Functional exposomics approach to study the exposome. In the top-down approach, molecular epidemiology studies focus on exposure (e.g., small molecule biomarkers of exogenous compounds, protein adducts, reactive metabolites) and biological response profiles (e.g., metabolomics, gene expression, methylation) within the host using biospecimens. This approach can generate hypotheses regarding exposure–disease and exposure–response relationships but does not necessarily capture direct measures of exposure. In the bottom-up approach, comprehensive data on environmental exposures are collected through surveys, sensors, or trace analytical chemistry in environmental samples (external exposures) or in biospecimens. This can generate hypotheses on effects but does not necessarily investigate the effect. We propose that a functional exposomics study bridges these two approaches and consists of the biologically active exposures present in an individual and specifically examines associations between environmental exposure and biological effect.

More recently, an expansion of the bottom-up definition has been made to include combinations of external exposure to chemical, physical, psychological, and social factors. As comprehensive understanding of bottom-up exposures increases, new and more sophisticated hypotheses can be developed regarding potential health consequences. Concurrent to advances in analytical chemistry, methods to measure the external exposome are also expanding. Geospatial methods to measure indirect exposure include satellite remote sensing to measure air pollution, human activities, and green space among other end points.47 Census data can be mined for neighborhood characteristics. Public databases contain extensive information including crime, infections, environmental measures, and pesticide application rates, as well as geospatial data that can be linked to home address, school, or work.48−50 Personal air samplers (passive and active)51−55 can be worn to monitor bottom-up exposures in the near-field environment, and smartphone apps or other wearable devices, such as smart watches, increasingly can be used to “crowd source” measures of noise, activity, and social factors and link them to physiologic measures.56 Recent work has even detailed an integrated pipeline to analyze a full complement of biotic and abiotic exposures in the personal airborne exposome.57 A great deal of potential for understanding social networks can be derived from social media platforms, rendering measures of the exposome even more robust and helping to identify sources of variability in the detected endogenous chemicals.

In contrast, the top-down strategy for finding causes of disease relies on samples of human biospecimens to simultaneously investigate exposures originating both inside and outside the body. By employing untargeted omics to compare exposomes in biospecimens from diseased and healthy subjects, it is now possible to discover potentially causal chromatographic features and use them to generate hypotheses for follow-up studies that confirm their chemical identities, identify sources of exposure, and establish exposure–response curves.36,58−60 Since blood is the most common biospecimen that is archived in prospective-cohort studies, this top-down strategy led to the concept of the “blood exposome” and broadened the universe of exposures to include pollutants, diet, drugs, and endogenous chemicals.17 More recent definitions of the exposome have been formulated to include the collection of other omics methods—metabolomics, metallomics, adductomics, proteomics, and metagenomics—that can characterize exposures61 and the molecular changes associated with exposures.60,62−66 Critical to this latter definition is the notion that a cumulative biological effect can be used to evaluate overall exposure and allostatic load.60 Incorporating biological responses within a top-down framework enables an understanding of how exposures exert stress on host homeostasis, while potentially revealing causal pathways and mechanisms underlying exposure–disease relationships. Recent applications of this approach that combine exposure monitoring with biological response, where multiple exposures are assessed in individuals and compared with phenotype or omics profiles, have provided novel insight into the role of environment in disease risk.36 This is exemplified by linking dietary exposure with various clinical outcomes and disease risk in an epidemiological setting using metabolomics-based approaches.67,68 However, while allostatic load can be estimated, the root causes of these stressors and the role of exposure timing, route, or source cannot be captured by a top-down approach and may even be absent from the analysis, limiting the ability to develop interventions.

Full characterization of causal exposome features and subsequent interventions requires knowledge of exposure sources. This is relatively simple when exposures are measured bottom-up in external media, such as air, water, or food (external exposome), but can be more complicated when measurements are made top-down in biofluids (internal exposome66). Herein, we propose to further distinguish measurable components of both approaches for characterizing the exposome. Accordingly, the exposome can be divided into the following four categories (Figure 1): Bottom-up: (i) general external exposures including the built environment, climate, air pollution, social stressors, socioeconomic factors, etc. and (ii) specific external exposures such as chemical contaminants, diet, occupational exposures, or medication. Top-down: (iii) internalized exogenous exposures that comprise the fraction of non-nutrient environmental molecules that have entered the organism and (iv) endogenous nutrient exposures, including gut microbiota and their associated metabolites, that arose either directly from the diet or are products of endogenous metabolism reflecting the exposure (e.g., lipid peroxidation products from oxidative stress, etc.). A combination of these four categories provides a framework for linking external exposure to internal dose, biological response. and adverse health outcomes, thus defining an individual’s functional exposome.

While bottom-up and top-down definitions of the exposome can aid in study design, the greatest potential in the application of exposomic approaches lies in integrating the top-down approach with the bottom-up approach. This approach, which we define here as functional exposomics, has a greater scope that enables synergy by combining internal measures of exposure and biological response with measures of the external environment in order to identify exposure sources, the source of the biological response, and to better establish disease causality.69 For example, untargeted high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) approaches may demonstrate that the small molecule chemical profiles in biofluids are central in linking external exposure (i.e., measured as environmental chemicals of concern in food) to internal dose (i.e., exposure biomarkers), biological response (measured as alterations in endogenous metabolic pathways), and disease (through shifts in metabolism linked to disease pathogenesis). This information can be linked to source of exposure (e.g., air, water, diet) to provide a complete understanding of the relationship between environment/exposome and health or disease outcome.67,68,70 This has been demonstrated by recent studies linking occupational exposures to a chlorinated volatile organic solvent with alterations in both the exogenous and endogenous metabolome,71 metabolomic phenotypes of exposure to common traffic-related air pollutants, and metabolite changes detected in individuals decades after an initial exposure occurred.71−74 Incorporating measures of additional omics layers within the exposome enables a systems–biology framework to study the effects of exposures, providing, for the first time, the comprehensive characterization needed to elucidate potential toxicological mechanisms at the population level.75 A recent report proposed eight hallmarks of environmental insult that jointly lay the foundation for the health consequences of environmental exposures.76

The current work focuses on the role of small molecules in the exposome of the type that are generally analyzed in untargeted metabolomics-based efforts using HRMS. However, the other “omic” approaches also play an important role in exposomic science. In particular, integrative “omics” offers the potential to provide global patterns coupled to metabolic and physiological dysregulations and capture the biological complexity associated with exogenous exposures. One omic technology that has been explored in detail is adductomics,77−79 which has been proven useful for identifying exposures to exogenous compounds and in newborn blood spots.64 While beyond the scope of this work, interested readers are encouraged to explore examples of the applications of proteomics,80 genomics,81 and epigenetics82 to investigating the exposome. It is expected that these technologies will continue to contribute to our understanding of the health effects of environmental exposure.83

The necessity of exposomics will be further amplified by the consequences of climate change, with multiple ramifications for the environment and the ensuing effects upon human health.84,85 Accordingly, exposomics should be considered an important component of climate change research. In addition, although all these approaches are largely discussed from a human perspective, they can be equivalently applied to other organisms. For example, the polar bear blood exposome has been examined to identify the specific chemicals that lead to thyroid disruption.86 Other laboratory animal models are being used to simulate human exposome conditions, such as to combinations of dietary and occupational exposures, but also to understand aquatic exposomes downstream of municipal wastewater,87 as well as for real-world applications due to tire rubber-derived exposure.88 Nonhuman exposome studies will be important for the protection of wildlife and ecosystems as recently demonstrated for coho salmon88 and will also protect humans under the one health paradigm.89,90

Considerations in Exposome Study Design

Exposomics is a nascent field with unique data requirements, thus existing cohorts and ongoing studies may not be optimal for exposome studies.91 For example, many existing large-scale metabolomics studies were designed to explore associations between nutrient metabolites and health outcomes, and general demographic and disease-specific clinical parameters were collected with this sole intention. Data on environmental exposures, or exposure biomarkers, and broader health conditions are often lacking, and biological samples may not be of sufficient quality or quantity for comprehensive and optimal exposomic analyses. An atlas or reference exposome study has not yet been conducted but is sorely needed. Such a study would be analogous to efforts in genomics to haplotype different populations around the world (i.e., the Hapmap). Because the exposome will vary by culture, geography, time (i.e., the 1990s are different from the 2020s) and life stage (an infant is different from an adult), mapping a reference exposome will require significant resources, similar to the Hapmap project. However, the potential benefit to researchers is enormous because it will enable us to better understand the role of culture, geography, life stage, and time in predicting the exposome and improve our interpretation of results enabling better causal inference. Such a large-scale global project should be a major priority for researchers and will require substantial resources and collaboration. With respect to the more typical exposome study, we propose a suite of guidelines that are described in the Supporting Information.

Measuring the Chemical Exposome by Mass Spectrometry

There are multiple approaches for data acquisition that should be considered in comprehensive exposome studies, including questionnaires, mobile sensors for air quality92 and noise,93 UV exposure,94 and physical activity,95,96 as well as smartphone apps to assist with acquisition of dietary data.97 Nevertheless, given the great potential for making molecular links between bottom-up and top-down studies, the current discussion focuses on the application of mass spectrometry for acquiring the small molecule chemical exposome, with an emphasis on HRMS acquisition and untargeted data analysis.

Considering the complexity of the chemical exposome, it is unlikely that there will soon be a single untargeted method capable of capturing the full range of small molecules that are present in biofluids or environmental samples.98 In a review of the human blood exposome by Rappaport et al.,17 the concentrations of 94 known pollutants, 49 drugs, 195 food chemicals, and 1223 endogenous chemicals spanned 11 orders of magnitude in blood, from 160 fM to 140 mM.17 Considering that modern mass spectrometers are at best linear over 5–6 orders of magnitude, several types of unbiased sample extractions and untargeted analytical methods will be required to achieve detection and semiquantification for a comprehensive profile of small molecules in human blood.98

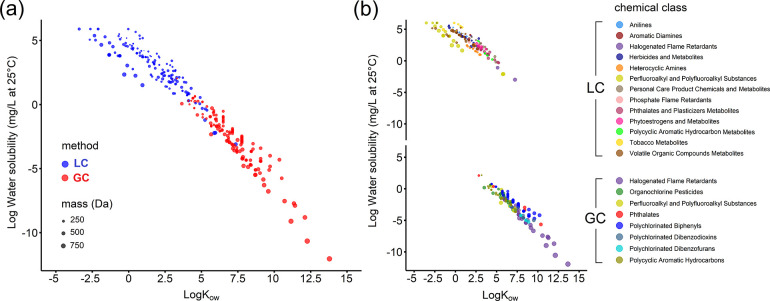

Untargeted high-resolution metabolomics analysis, based on liquid chromatography (LC) and HRMS has been proposed for “sequencing the exposome”,38 but clearly, a wider range of instrumental approaches will be required. This can be exemplified by considering the wide range of organic contaminants routinely monitored in human blood by target methods (Figure 2). These analytes span approximately 18 orders of magnitude in water solubility and 15 orders of magnitude in octanol–water partition coefficients. Only half of these analytes are relatively water soluble and have polar functional groups that can be ionized under atmospheric pressure, making them amenable to LC-HRMS workflows. The other half are relatively nonpolar and semivolatile and are best analyzed by gas chromatography (GC)-HRMS workflows. Untargeted GC-HRMS is therefore becoming increasingly popular as a complement to LC-HRMS, which together enable a more comprehensive coverage of the small molecule exposome.99−102 Furthermore, considering that prominent hydrophobic organic contaminants are preferably analyzed by GC, and their biotransformation products are only detectable by LC,103 the combination of both instrumental approaches in untargeted modes could simultaneously reveal exposure sources and individual variation in biotransformation capacity. For truly comprehensive exposure, trace metals in blood should be analyzed by another method such as inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS).104

Figure 2.

Full coverage of the chemical exposome will require multiple instrumental approaches, as shown by the chemical space of 299 internal exogenous analytes routinely targeted in large population biomonitoring studies in blood or urine. a) Measurement of the analytes will require a mixture of LC- and GC-based approaches that are b) dependent upon the analyte class. Analytes were selected from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (1999–2016, latest update in 2019), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (USA), and HBM4 EU (European Environment Agency, and European Commission, latest update in 2018). Water solubility and Kow values are estimated from EPA EPI Suite software and span 18 orders of magnitude for water solubility and 15 orders of magnitude for Kow. Estimations of the Kow values for the anionic perfluoroalkyl acids included in the class of perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances are from Hidalgo and Mora-Diez.163

HRMS technologies are an essential component for characterizing the human exposome because of their inherent sensitivity, dynamic range, and high-frequency full scanning with high mass accuracy.105,106 The present capabilities of these instruments to collect full scan MS1 and parallel MS2 data, by data-dependent or data-independent approaches, opens possibilities to identify known substances through formula assignment and spectral library matching, with the additional possibility to annotate and structurally characterize complex “molecular dark matter”, which constitutes the majority of all HRMS signals in typical samples.107−112 In addition, the advent of ion mobility technologies can provide further resolving power for untargeted approaches.113−116 However, critical challenges remain. As described by Rappaport et al.,17 the abundance of environmental chemicals in biological samples is, on average, 3 orders of magnitude lower than endogenous metabolites, drugs, or dietary components. Thus, going beyond the metabolome into the exposome necessitates higher sensitivity instruments or methods. Unbiased sample preparation methods should be further developed to comprehensively concentrate the trace small molecule exposome, while minimizing matrix suppression by highly abundant endogenous metabolites (e.g., phospholipids). Although untargeted HRMS data acquisition strategies are not inherently quantitative (i.e., few internal standards, lack of external calibration curves for most analytes), a strategy has been developed and validated that allows retrospective quantification of analytes discovered in untargeted exposome studies. The so-called “reference standardization protocol” makes use of concurrently analyzed pooled reference samples and was shown to be comparable to surrogate standardization or internal standardization.117,118

Sample throughput in HRMS approaches remains an obstacle to large exposome studies, and this is compounded here by our recommendations that multiple mass spectrometry methods should be applied to individual samples. For example, the Japan Environment and Children’s Study (JECS)119−121 cohort has hundreds of thousands of individual samples, which may not be feasible for the current state of HRMS without many dedicated instruments working in parallel. As a reference point, JECS is currently analyzing 5000–20,000 samples by mass spectrometry per year for heavy metals, PFASs, and phthalate metabolites, as well as some insecticides; however, this throughput is not currently feasible for brominated/phosphorus flame retardants, dioxins, and some pesticides that require complex sample preparations. Targeted LC-MS/MS methods (i.e., with MRM transitions) are becoming more comprehensive and can be adapted to increase throughput in exposomics studies. For example, a recent platform was able to analyze 1000 metabolites or exposome-related compounds using a triple quadrupole linear ion trap instrument.63 Conversely, it is not always necessary to analyze thousands of chemicals. Attempts have been made to prioritize chemicals for exposome-based studies, enabling the development of targeted quantitative methods suitable for low-abundant molecules that are difficult to measure with screening approaches.122

While there is a necessity to increase mass spectrometry throughput, there is a concomitant need to increase institutional investment in facilities for exposome studies at a scale that approaches the investments in genome sequencing technologies. In order to actionize the exposome on the scale of the Human Genome Project, extensive support will be required from funders. Concurrent with this investment, there is a requisite need for method standardization and data harmonization. A good example of these efforts is the EPA’s Non-Targeted Analysis Collaborative Trial (ENTACT), which included nearly 30 laboratories to characterize 10 synthetic chemical mixtures, three standardized media (human serum, house dust, and silicone band) extracts, and thousands of individual substances using GC- and LC-HRMS approaches.123 While it is not realistic or even desirable for every laboratory to employ identical methodologies, common retention indexing in LC and GC approaches, as well as common reference materials (e.g., NIST SRM1950 for plasma) could assist in producing data that can be combined across independent laboratories.124 For example, the concentration of small molecules could be normalized based on their fold difference relative to human plasma (NIST SRM1950) or semiquantified against other common reference materials using reference standardization.117

A number of existing resources support MS-based untargeted small molecule profiling and identification, including open-access software for data preprocessing (e.g., MS-DIAL,125 MZmine,126 XCMS127) and compound databases and spectral libraries (e.g., Massbank,128 GNPS,129 HMDB,130 T3DB,131 and PubChemLite132,133), as well as resources dedicated to cover the exposome and its associated metabolism (e.g., Exposome-Explorer,134 NORMAN (https://www.norman-network.com/), and CECscreen135). Confidence in annotations can be strengthened by using a standardized retention indexing system. For GC, a robust system already exists (Kovats retention index, using a series of alkanes), but for LC, there is currently no widely accepted method for any mode of chromatography. Efforts have been made to establish a similar strategy for LC-MS with a series of 2-dimethylaminoethylamine (DMED)-labeled fatty acids.136 Moreover, new approaches based on drift time in ion-mobility separation (i.e., based on collision cross section) in modern hybrid mass spectrometers show alternative promise.137,138 Software for data analysis that can accommodate both LC- and GC-HRMS chromatograms, while deconvoluting MS2 data, must continue to be optimized and validated.139 Ideally, the software and supporting spectral libraries should be vendor neutral (e.g., mzXML) to enable experimental replication and to support open science activities under FAIR data management principles (findability, accessibility, interoperability, and reusability). A bottleneck in exposome studies is the structural characterization of hundreds or thousands of important, yet unknown, molecular features in human or environmental samples, but powerful open science tools are increasingly available that combine untargeted MS1 and MS2 data for high-throughput structural characterization by molecular networking.140 These resources and approaches, if commonly adopted, would open the possibility to combine several small exposome studies into larger and more powerful metastudies.

Working with Exposome Data

A Call to Create a Comprehensive Exposome Database

There have been a number of initial efforts in exposome database construction.141,142 The EPA CompTox Chemical Dashboard, in particular, is an excellent source that currently contains 882,000 chemicals as of December 2020.143 In addition, the NORMAN network (http://www.norman-network.net/) contains extensive information on emerging substances in the environment, and the recent COlleCtion of Open Natural prodUcTs (COCONUT) database provides over 400,000 unique natural products.144 However, the majority of databases focus on the parent structures of exposures and lack information on the biological and microbiota transformation products, which can serve as internal biomarkers of both exposures and biological processes. Moreover, the dark matter of the metabolome (known unknowns112) in the existing databases is largely missing. Incorporating known unknowns into future methods or data analysis workflows can be done by sharing suspect lists (e.g., 10.5281/zenodo.2656745)145 with associated confidence levels for compound annotation146 and even proposed structures. Likewise, the current repositories for food-borne compounds still lack spectral information essential for identification purposes, and in general, the biochemical diversity in foods remains relatively poorly catalogued.147 In the future, this can be vastly improved by retention index reporting and associated MS2 spectra. In current databases, various nomenclature methods are used including IUPAC Name, InChI, InChIKey, SMILES, CHEBI, and CAS Number. There should be a common nomenclature and ontology dedicated to exposome chemicals, and InChIKey might be the best choice because it facilitates the search and share of chemical information and is commonly used in most databases due to its fixed length and format. In order to make it comprehensive, an exposome database should also include organometallic compounds that are not routinely analyzed by HRMS-based approaches. With respect to the analysis, interpretation, and reporting of exposomic data, we provide additional discussion and details in the Supporting Information.

Precision Diagnostics

A potential future application of exposomics is in the area of diagnostic tools. The relative transiency of metabolic changes across individuals may be limiting in this regard, but for chronic illnesses (i.e., cancer, liver disease), disease specific signatures have already been described.148,149 A potentially overlooked area of research is nontraditional biological matrices—such as skin, hair, or toenails. Medicine has traditionally focused on blood and urine as the major biosamples for routine medical monitoring. However, tissues with slow growth rates may offer complementary findings that reflect integrated changes in metabolism over time.150−152 While exogenous chemicals can contaminate these tissues, focusing on endogenous metabolites (e.g., cotinine, cortisol) has been validated in targeted assays.153,154 Additional research is needed using nonconventional biological matrices because they may provide cumulative and/or time varying information on metabolic changes secondary to disease. Further, given that the pharmacokinetics of chemicals favor measurement in different matrices (e.g., hydrophobic chemicals tend to be better measured in plasma, while hydrophilic chemicals are better measured in urine), researchers should consider the use of multiple biomatrix samples in conducting exposomic studies. For example, the use of both plasma and urine would increase overall coverage of the exposome compared to studies that use only a single biomatrix for analysis.

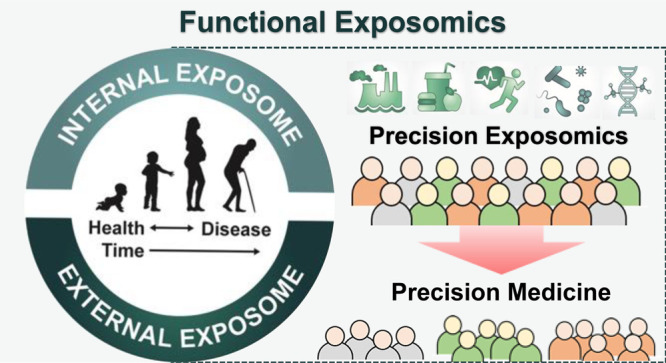

Precision Exposomics

One of the most important ways to integrate exposomics into healthcare is to focus on precision medicine, which is designed to optimize efficiency, diagnosis, or therapeutic benefit for particular subgroups of patients. To date, precision medicine has focused on genetic or molecular (epigenomics, proteomic, etc.) profiling. However, we know that the environment must be a driver of patient response to treatment or disease progression. For example, if lead is neurotoxic, it stands to reason that exposure to lead will affect the progression of Alzheimer’s Disease or Autism. Further, we are well aware that air pollution affects asthma and that smoking will exacerbate lung and heart disease. Nevertheless, environmental or exposomic issues are rarely considered in precision medicine programs. For precision medicine to be truly precise, there is a clear need to incorporate environmental factors that determine the variability in treatment effects or disease progression. Furthermore, because environmental factors are modifiable, identifying their role in the response to treatment may be actionable. Therefore, a major driver of exposomics should be to identify markers of vulnerability and susceptibility that can be clinically actionable.155 To do this, exposomics must expand from public health prevention studies (i.e., case control or longitudinal cohorts of healthy individuals) that address the environmental causes of disease to clinical studies of patients to determine how environment impacts existing disease. Although a seemingly subtle shift in focus, the purpose and interpretation of clinical research is very different from public health research. Clinicians may not find causal environmental factors to be useful in patient care. For example, the clinical treatment of a 61-year-old man who has a history of smoking and presents with a lung cancer is not impacted by the smoking history. Decisions on his care, (e.g., surgery, chemotherapy, or even hospice) will be made independent of his smoking history. However, if we begin to measure exposomic chemical signatures when such patients present, we may begin to impact such decisions. It is reasonable to hypothesize that certain signatures predict differential responses to chemotherapeutic agents, resulting in a need to modify their dose to reduce the degree of side effects. Further, as we create better informatic tools to identify the source of chemical signatures (diet, home environment, behavior, geography, cultural practices, water/air quality, etc.), we may be able to alter such signatures toward preferred treatment phenotypes. In doing so, we become partners in the growing wave of precision medicine and open the possibility to understand the gene–environment interactions that are impacting clinical outcomes. This information can be combined with data from wearables to provide a digital phenotype that includes a temporal component necessary for establishing causality in relation to environmental exposures.

Exposomic studies combined with wearables may be able to identify previously unknown triggers of disease exacerbation at the individual level, such as triggers of asthma attacks or angina. It would be of particular benefit to identify personalized environmental triggers of disease exacerbation or progression as well as environmental factors that interfere with drug treatment. For example, personal environment sample collecting devices could be carried by individuals with asthma or chronic lung disease.57 The collected samples could then be analyzed using mature exposome-based protocols that measure thousands of small molecules and environmental chemicals of concern. A more specific example is that of a metabolomics-based method that monitored real-time exposure to xenobiotics in sweat.156 The data provided personalized exposure profiles of individuals that can be coupled to individualized metabolic activities to map the physiological response to exposure. When coupled with a symptom diary or, even better, physiologic data such as that collected by a wearable device,157 we can individualize our understanding of the triggers of disease exacerbation. When that is possible, exposomics will then have entered the world of clinical medicine. Further, by doing so, exposomics and environmental health will finally be integrated into medical education, which has been long overdue. As another example, a targeted approach might include screening for the most suspect environmental stressors that have already been linked to a particular disease. Obesogenic chemical exposures such as phthalates could be screened in patients with Type 2 diabetes and linked to measures of insulin resistance (e.g., hemoglobin A1c) and if exposures are associated with higher glucose; then, interventions implemented to reduce phthalate exposure could be made accordingly158 with glucose monitoring to establish cause and effect of the intervention. The effect of potential drug–exposome interactions can also be evaluated and catalogued in databases maintained by health care facilities.159 Personalized nutrition will be an important component of an exposome-based approach,160,161 and dietary intervention remains a readily actionable area. In addition to the medical level, an exposome (i.e., untargeted) approach can also be applied as a public health prevention measure in communities that experience clusters of disease, such as cancer. Such a precision public health initiative could discover chemicals that may impact disease in the community and develop strategies to reduce exposure in susceptible patients. Furthermore, a variety of “omics” platforms can be used to enhance plausibility in the context of environmental health challenges that may be contentious and politically sensitive. Support for mechanistic underpinnings for a charged claim related to social inequities driving adverse health effects, for example, through unbiased observation of DNA methylation associated with various levels of disadvantage, may add value to candidate end point approaches that can be seen as preordained via prior observations. As one specific such application, early life family adversity was shown to be reflected in patterns of DNA methylation in kindergarten children,162 increasing the call for interventions to protect youth for such stresses. Given our increasing understanding of the causal role that environmental exposures exert in disease etiology, precision exposomics will become an important component of precision medicine approaches to personalized healthcare as well as public health initiatives.

Conclusion

The exposome concept is maturing and gaining increasing applications in human and wildlife studies. Significant progress has been made in multiple areas including the following: (1) The scope and composition of the exposome has become clearer. (2) Increased numbers of health researchers have begun including exposomic risks in etiological research. (3) The urgency and importance of funding exposome projects has been acknowledged by governments and funding agencies. (4) Advanced techniques and methods for characterizing exposures and tools for analyzing complex data sets are more available. (5) Databases for compiling and sharing exposome data are evolving quickly. However, there are still multiple obstacles to actionizing the exposome to directly benefit patients and contribute to disease prevention. Some critical challenges include the following: (1) How to untangle the interactions across exposures and those between exposures and genomes, microbiomes, and other endogenous factors that could influence exposure-disease relationships. (2) Replication and validation of the findings will be needed for better delineating the causes of human diseases. (3) Statistical and computational methods will be required to meaningfully associate the exposome to health outcomes. (4) Methods will be needed to characterize personal exposome phenotypes and utilize the information to achieve precision medicine. These efforts will require the combined endeavors of diverse stakeholders including basic scientists, clinicians, policy makers, funders, and the general public to resolve the challenges. Working together across disciplines, we can actionize the exposome to increase our understanding of the etiology of chronic heterogeneous diseases toward the goal of intervention and future disease prevention.

Key Messages

-

(1)

The exposome is the interplay of environmental exposure and biological effect. It can be studied top-down, bottom-up, or by an integrated functional approach. Each approach contributes new knowledge and may also lead to sophisticated new hypotheses.

-

(2)

Small molecule profiling by high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) is a key approach for measuring external and internal exposures, including exogenous and endogenous molecules. However, additional efforts to combine GC- and LC-analytical approaches are needed for comprehensive exposomic measures.

-

(3)

Large investments in mass spectrometry infrastructure will be necessary to support human exposome studies on a scale equivalent to the human genome project. This should be done in conjunction with activities in support of method standardization.

-

(4)

Open science workflows and comprehensive public exposome databases in combination with spectral libraries of known and known-unknown substances will accelerate exposome knowledge.

-

(5)

There is a need for significant developments in big data analysis and informatics approaches in order to establish causal links between exposure and adverse health outcomes.

-

(6)

The precision exposome promises to be an important component of precision medicine and precision public health.

-

(7)

Strengthening communication between scientists across disciplines in combination with the development of interdisciplinary exposomics centers is vital for tackling the challenge of the exposome.

Acknowledgments

We thank Komugi Kanazawa, Kyoko Miyoshi, and Kyoko Ogura for extensive support for the planning of the symposium and workshop.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.estlett.1c00648.

Figure S1: Speaker list for the symposium. Extended discussions of the sections “Considerations in Exposome Study Design” and “Working with Exposome Data”. (PDF)

Author Contributions

P.Z. and C.E.W. planned and drafted the manuscript. C.C., R.C., K.H., M.H., T.I., V.M.K., J.W.M., I.M., S.P., S.M.R., K.S., H.T., D.I.W., T.J.W., R.O.W., and H.X. assisted in editing and reviewing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript for publication.

This work was supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) KAKENHI grants (JP18H06121, JP19K21239, 19K17662) and the Japanese Environment Research and Technology Development Fund (No. 5-1752). We acknowledge the Gunma University Initiative for Advanced Research (GIAR), the STINT Foundation, the Swedish Heart Lung Foundation (HLF 20170734, HLF 20180290, HLF 20200693), and the Swedish Research Council (2016-02798). K.H. has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under Grants Agreement No. 874739 and No. 754412. D.I.W. and C.E.W. are part of the EXPANSE consortium funded by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program (No. 874627). S.R. received funding from the U.S. National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (P42ES004705). T.J.W. was funded by NIH R01ES027051 and UH3 OD023272. R.O.W. received funding from NIH P30ES023515, U2CES026561, UH3OD02337 and U2CES030435.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Pott P.Chirurgical Observations Relative to the Cataract, The Polypus of the Nose, The Cancer of the Scrotum, The Differenent Kinds of Ruptures, and The Mortification of the Toes and Feet; T. J. Carnegy, for L. Hawes, W. Clarke, and R. Collins: London, 1775. [Google Scholar]

- Doll R.; Hill A. B. The mortality of doctors in relation to their smoking habits; a preliminary report. Br Med. J. 1954, 1 (4877), 1451–5. 10.1136/bmj.1.4877.1451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carson R.Silent Spring; Houghton Mifflin: Boston, MA, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Schafer M. L.; Peeler J. T.; Gardner W. S.; Campbell J. E. Pesticides in drinking water. Waters from the Mississippi and Missouri Rivers. Environ. Sci. Technol. 1969, 3 (12), 1261–1269. 10.1021/es60035a005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grohs M. N.; Reynolds J. E.; Liu J.; Martin J. W.; Pollock T.; Lebel C.; Dewey D. Prenatal maternal and childhood bisphenol a exposure and brain structure and behavior of young children. Environ. Health 2019, 18 (1), 85. 10.1186/s12940-019-0528-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawthorne S. B.; Grabanski C. B.; Miller D. J. Solid-phase-microextraction measurement of 62 polychlorinated biphenyl congeners in milliliter sediment pore water samples and determination of K(DOC) values. Anal. Chem. 2009, 81 (16), 6936–43. 10.1021/ac901001j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotlarz N.; McCord J.; Collier D.; Lea C. S.; Strynar M.; Lindstrom A. B.; Wilkie A. A.; Islam J. Y.; Matney K.; Tarte P.; Polera M. E.; Burdette K.; DeWitt J.; May K.; Smart R. C.; Knappe D. R. U.; Hoppin J. A. Measurement of Novel, Drinking Water-Associated PFAS in Blood from Adults and Children in Wilmington, North Carolina. Environ. Health Perspect. 2020, 128 (7), 077005. 10.1289/EHP6837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorber M.; Phillips L. Infant exposure to dioxin-like compounds in breast milk. Environ. Health Perspect. 2002, 110 (6), A325–32. 10.1289/ehp.021100325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbstman J. B.; Mall J. K. Developmental Exposure to Polybrominated Diphenyl Ethers and Neurodevelopment. Curr. Environ. Health Rep 2014, 1 (2), 101–112. 10.1007/s40572-014-0010-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radke E. G.; Braun J. M.; Nachman R. M.; Cooper G. S. Phthalate exposure and neurodevelopment: A systematic review and meta-analysis of human epidemiological evidence. Environ. Int. 2020, 137, 105408. 10.1016/j.envint.2019.105408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z.; Walker G. W.; Muir D. C. G.; Nagatani-Yoshida K. Toward a Global Understanding of Chemical Pollution: A First Comprehensive Analysis of National and Regional Chemical Inventories. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54 (5), 2575–2584. 10.1021/acs.est.9b06379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi A. D.; Kim A.; Lewinger J. P.; Ulrich C. M.; Potter J. D.; Cotterchio M.; Le Marchand L.; Stern M. C. Meat intake, cooking methods, dietary carcinogens, and colorectal cancer risk: findings from the Colorectal Cancer Family Registry. Cancer Med. 2015, 4 (6), 936–52. 10.1002/cam4.461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Pena D.; Brennan L. Recent Advances in the Application of Metabolomics for Nutrition and Health. Annu. Rev. Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 10, 479–519. 10.1146/annurev-food-032818-121715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milanlouei S.; Menichetti G.; Li Y.; Loscalzo J.; Willett W. C.; Barabási A.-L. A systematic comprehensive longitudinal evaluation of dietary factors associated with acute myocardial infarction and fatal coronary heart disease. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11 (1), 6074. 10.1038/s41467-020-19888-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scalbert A.; Brennan L.; Manach C.; Andres-Lacueva C.; Dragsted L. O.; Draper J.; Rappaport S. M.; van der Hooft J. J.; Wishart D. S. The food metabolome: a window over dietary exposure. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2014, 99 (6), 1286–308. 10.3945/ajcn.113.076133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- do Valle I. F.; Roweth H. G.; Malloy M. W.; Moco S.; Barron D.; Battinelli E.; Loscalzo J.; Barabási A.-L. Network medicine framework shows that proximity of polyphenol targets and disease proteins predicts therapeutic effects of polyphenols. Nat. Food 2021, 2 (3), 143–155. 10.1038/s43016-021-00243-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rappaport S. M.; Barupal D. K.; Wishart D.; Vineis P.; Scalbert A. The blood exposome and its role in discovering causes of disease. Environ. Health Perspect. 2014, 122 (8), 769–74. 10.1289/ehp.1308015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi L.; Brunius C.; Bergdahl I. A.; Johansson I.; Rolandsson O.; Donat Vargas C.; Kiviranta H.; Hanhineva K.; Akesson A.; Landberg R. Joint Analysis of Metabolite Markers of Fish Intake and Persistent Organic Pollutants in Relation to Type 2 Diabetes Risk in Swedish Adults. J. Nutr. 2019, 149 (8), 1413–1423. 10.1093/jn/nxz068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pirttila K.; Videhult Pierre P.; Haglof J.; Engskog M.; Hedeland M.; Laurell G.; Arvidsson T.; Pettersson C. An LCMS-based untargeted metabolomics protocol for cochlear perilymph: highlighting metabolic effects of hydrogen gas on the inner ear of noise exposed Guinea pigs. Metabolomics 2019, 15 (10), 138. 10.1007/s11306-019-1595-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oresic M.; McGlinchey A.; Wheelock C. E.; Hyotylainen T. Metabolic Signatures of the Exposome-Quantifying the Impact of Exposure to Environmental Chemicals on Human Health. Metabolites 2020, 10 (11), 454. 10.3390/metabo10110454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emeny R. T.; Carpenter D. O.; Lawrence D. A. Health disparities: Intracellular consequences of social determinants of health. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2021, 416, 115444. 10.1016/j.taap.2021.115444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casey J. A.; Morello-Frosch R.; Mennitt D. J.; Fristrup K.; Ogburn E. L.; James P. Race/Ethnicity, Socioeconomic Status, Residential Segregation, and Spatial Variation in Noise Exposure in the Contiguous United States. Environ. Health Perspect. 2017, 125 (7), 077017. 10.1289/EHP898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh G.; Singh V.; Wang Z. X.; Voisin G.; Lefebvre F.; Navenot J. M.; Evans B.; Verma M.; Anderson D. W.; Schneider J. S. Effects of developmental lead exposure on the hippocampal methylome: Influences of sex and timing and level of exposure. Toxicol. Lett. 2018, 290, 63–72. 10.1016/j.toxlet.2018.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsson T.; Barcellos L. F.; Alfredsson L. Interactions between genetic, lifestyle and environmental risk factors for multiple sclerosis. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2017, 13 (1), 25–36. 10.1038/nrneurol.2016.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reardon A. J. F.; Karathra J.; Ribbenstedt A.; Benskin J. P.; MacDonald A. M.; Kinniburgh D. W.; Hamilton T. J.; Fouad K.; Martin J. W. Neurodevelopmental and Metabolomic Responses from Prenatal Coexposure to Perfluorooctanesulfonate (PFOS) and Methylmercury (MeHg) in Sprague-Dawley Rats. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2019, 32 (8), 1656–1669. 10.1021/acs.chemrestox.9b00192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho R. N.; Arukwe A.; Ait-Aissa S.; Bado-Nilles A.; Balzamo S.; Baun A.; Belkin S.; Blaha L.; Brion F.; Conti D.; Creusot N.; Essig Y.; Ferrero V. E.; Flander-Putrle V.; Furhacker M.; Grillari-Voglauer R.; Hogstrand C.; Jonas A.; Kharlyngdoh J. B.; Loos R.; et al. Mixtures of chemical pollutants at European legislation safety concentrations: how safe are they?. Toxicol. Sci. 2014, 141 (1), 218–33. 10.1093/toxsci/kfu118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlsten C. Synergistic Environmental Exposures and the Airways Capturing Complexity in Humans: An Underappreciated World of Complex Exposures. Chest 2018, 154 (4), 918–924. 10.1016/j.chest.2018.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu M.; Jia S.; Dong T.; Zhao F.; Xu T.; Yang Q.; Gong J.; Fang M. Metabolomic and Transcriptomic Analysis of MCF-7 Cells Exposed to 23 Chemicals at Human-Relevant Levels: Estimation of Individual Chemical Contribution to Effects. Environ. Health Perspect. 2020, 128 (12), 127008. 10.1289/EHP6641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel C. J.; Pho N.; McDuffie M.; Easton-Marks J.; Kothari C.; Kohane I. S.; Avillach P. A database of human exposomes and phenomes from the US National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Sci. Data 2016, 3, 160096. 10.1038/sdata.2016.96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apel P.; Rousselle C.; Lange R.; Sissoko F.; Kolossa-Gehring M.; Ougier E. Human biomonitoring initiative (HBM4 EU) - Strategy to derive human biomonitoring guidance values (HBM-GVs) for health risk assessment. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2020, 230, 113622. 10.1016/j.ijheh.2020.113622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wild C. P. Complementing the genome with an “exposome“: the outstanding challenge of environmental exposure measurement in molecular epidemiology. Cancer Epidemiol., Biomarkers Prev. 2005, 14 (8), 1847–50. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simonds N. I.; Ghazarian A. A.; Pimentel C. B.; Schully S. D.; Ellison G. L.; Gillanders E. M.; Mechanic L. E. Review of the Gene-Environment Interaction Literature in Cancer: What Do We Know?. Genet Epidemiol 2016, 40 (5), 356–65. 10.1002/gepi.21967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rappaport S. M. Genetic Factors Are Not the Major Causes of Chronic Diseases. PLoS One 2016, 11 (4), e0154387 10.1371/journal.pone.0154387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rappaport S. M. Redefining environmental exposure for disease etiology. NPJ. Syst. Biol. Appl. 2018, 4 (1), 1–6. 10.1038/s41540-018-0065-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rappaport S. M.; Smith M. T. Environment and disease risks. Science 2010, 330 (6003), 460–461. 10.1126/science.1192603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vermeulen R.; Schymanski E. L.; Barabasi A. L.; Miller G. W. The exposome and health: Where chemistry meets biology. Science 2020, 367 (6476), 392–396. 10.1126/science.aay3164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheelock C. E.; Rappaport S. M. The role of gene-environment interactions in lung disease: the urgent need for the exposome. Eur. Respir. J. 2020, 55 (2), 1902064. 10.1183/13993003.02064-2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones D. P. Sequencing the exposome: A call to action. Toxicol Rep 2016, 3, 29–45. 10.1016/j.toxrep.2015.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang P.; Arora M.; Chaleckis R.; Isobe T.; Jain M.; Meister I.; Melen E.; Perzanowski M.; Torta F.; Wenk M. R.; Wheelock C. E. Tackling the Complexity of the Exposome: Considerations from the Gunma University Initiative for Advanced Research (GIAR) Exposome Symposium. Metabolites 2019, 9 (6), 106. 10.3390/metabo9060106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haddad N.; Andrianou X. D.; Makris K. C. A Scoping Review on the Characteristics of Human Exposome Studies. Curr. Pollut Rep 2019, 5 (4), 378–393. 10.1007/s40726-019-00130-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stingone J. A.; Buck Louis G. M.; Nakayama S. F.; Vermeulen R. C.; Kwok R. K.; Cui Y.; Balshaw D. M.; Teitelbaum S. L. Toward Greater Implementation of the Exposome Research Paradigm within Environmental Epidemiology. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2017, 38, 315–327. 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-082516-012750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossman J.; Macherone A. Review of the 32nd Sanibel Conference on Mass Spectrometry: Unraveling the Exposome. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2021, 32, 835. 10.1021/jasms.1c00065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vlaanderen J.; de Hoogh K.; Hoek G.; Peters A.; Probst-Hensch N.; Scalbert A.; Melen E.; Tonne C.; de Wit G. A.; Chadeau-Hyam M.; Katsouyanni K.; Esko T.; Jongsma K. R.; Vermeulen R. Developing the building blocks to elucidate the impact of the urban exposome on cardiometabolic-pulmonary disease: The EU EXPANSE project. Environ. Epidemiol 2021, 5 (4), e162 10.1097/EE9.0000000000000162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vineis P.; Robinson O.; Chadeau-Hyam M.; Dehghan A.; Mudway I.; Dagnino S. What is new in the exposome?. Environ. Int. 2020, 143, 105887. 10.1016/j.envint.2020.105887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rappaport S. M.; Smith M. T. Epidemiology. Environment and disease risks. Science 2010, 330 (6003), 460–1. 10.1126/science.1192603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rappaport S. M. Implications of the exposome for exposure science. J. Exposure Sci. Environ. Epidemiol. 2011, 21 (1), 5–9. 10.1038/jes.2010.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorek-Hamer M.; Just A. C.; Kloog I. Satellite remote sensing in epidemiological studies. Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 2016, 28 (2), 228–34. 10.1097/MOP.0000000000000326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Q.; Dai L.; Wang Y.; Zanobetti A.; Choirat C.; Schwartz J. D.; Dominici F. Association of Short-term Exposure to Air Pollution With Mortality in Older Adults. JAMA 2017, 318 (24), 2446–2456. 10.1001/jama.2017.17923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakerveld J.; Wagtendonk A.; Vaartjes I.; Karssenberg D. Deep phenotyping meets big data: the Geoscience and hEalth Cohort COnsortium (GECCO) data to enable exposome studies in The Netherlands. Int. J. Health Geogr 2020, 19 (1), 49. 10.1186/s12942-020-00235-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrianou X. D.; Pronk A.; Galea K. S.; Stierum R.; Loh M.; Riccardo F.; Pezzotti P.; Makris K. C. Exposome-based public health interventions for infectious diseases in urban settings. Environ. Int. 2021, 146, 106246. 10.1016/j.envint.2020.106246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang C.; Wang X.; Li X.; Inlora J.; Wang T.; Liu Q.; Snyder M. Dynamic Human Environmental Exposome Revealed by Longitudinal Personal Monitoring. Cell 2018, 175 (1), 277–291. 10.1016/j.cell.2018.08.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connell S. G.; Kincl L. D.; Anderson K. A. Silicone Wristbands as Personal Passive Samplers. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 48 (6), 3327–3335. 10.1021/es405022f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin E. Z.; Esenther S.; Mascelloni M.; Irfan F.; Godri Pollitt K. J. The Fresh Air Wristband: A Wearable Air Pollutant Sampler. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2020, 7 (5), 308–314. 10.1021/acs.estlett.9b00800. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guo P.; Lin E. Z.; Koelmel J. P.; Ding E.; Gao Y.; Deng F.; Dong H.; Liu Y.; Cha Y.; Fang J.; Shi X.; Tang S.; Godri Pollitt K. J. Exploring personal chemical exposures in China with wearable air pollutant monitors: A repeated-measure study in healthy older adults in Jinan, China. Environ. Int. 2021, 156, 106709. 10.1016/j.envint.2021.106709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young A. S.; Herkert N.; Stapleton H. M.; Cedeno Laurent J. G.; Jones E. R.; MacNaughton P.; Coull B. A.; James-Todd T.; Hauser R.; Luna M. L.; Chung Y. S.; Allen J. G. Chemical contaminant exposures assessed using silicone wristbands among occupants in office buildings in the USA, UK, China, and India. Environ. Int. 2021, 156, 106727. 10.1016/j.envint.2021.106727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J.; Campbell A. S.; de Avila B. E.; Wang J. Wearable biosensors for healthcare monitoring. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37 (4), 389–406. 10.1038/s41587-019-0045-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang C.; Zhang X.; Gao P.; Chen Q.; Snyder M. Decoding personal biotic and abiotic airborne exposome. Nat. Protoc. 2021, 16 (2), 1129–1151. 10.1038/s41596-020-00451-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis K. K.; Auerbach S. S.; Balshaw D. M.; Cui Y.; Fallin M. D.; Smith M. T.; Spira A.; Sumner S.; Miller G. W. The Importance of the Biological Impact of Exposure to the Concept of the Exposome. Environ. Health Perspect. 2016, 124 (10), 1504–1510. 10.1289/EHP140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lioy P. J.; Rappaport S. M. Exposure science and the exposome: an opportunity for coherence in the environmental health sciences. Environ. Health Perspect. 2011, 119 (11), A466–7. 10.1289/ehp.1104387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller G. W.; Jones D. P. The nature of nurture: refining the definition of the exposome. Toxicol. Sci. 2014, 137 (1), 1–2. 10.1093/toxsci/kft251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rappaport S. M. Redefining environmental exposure for disease etiology. NPJ. Syst. Biol. Appl. 2018, 4, 30. 10.1038/s41540-018-0065-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gil A. M.; Duarte D.; Pinto J.; Barros A. S. Assessing Exposome Effects on Pregnancy through Urine Metabolomics of a Portuguese (Estarreja) Cohort. J. Proteome Res. 2018, 17 (3), 1278–1289. 10.1021/acs.jproteome.7b00878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Dominguez R.; Jauregui O.; Queipo-Ortuno M. I.; Andres-Lacueva C. Characterization of the Human Exposome by a Comprehensive and Quantitative Large-Scale Multianalyte Metabolomics Platform. Anal. Chem. 2020, 92 (20), 13767–13775. 10.1021/acs.analchem.0c02008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrick L. M.; Uppal K.; Funk W. E. Metabolomics and adductomics of newborn bloodspots to retrospectively assess the early-life exposome. Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 2020, 32 (2), 300–307. 10.1097/MOP.0000000000000875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Breda S. G.; Wilms L. C.; Gaj S.; Jennen D. G.; Briede J. J.; Kleinjans J. C.; de Kok T. M. The exposome concept in a human nutrigenomics study: evaluating the impact of exposure to a complex mixture of phytochemicals using transcriptomics signatures. Mutagenesis 2015, 30 (6), 723–31. 10.1093/mutage/gev008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wild C. P. The exposome: from concept to utility. Int. J. Epidemiol 2012, 41 (1), 24–32. 10.1093/ije/dyr236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noerman S.; Kokla M.; Koistinen V. M.; Lehtonen M.; Tuomainen T. P.; Brunius C.; Virtanen J. K.; Hanhineva K. Associations of the serum metabolite profile with a healthy Nordic diet and risk of coronary artery disease. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 40, 3250. 10.1016/j.clnu.2020.10.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y.; Fang M. Nutritional and Environmental Contaminant Exposure: A Tale of Two Co-Existing Factors for Disease Risks. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54 (23), 14793–14796. 10.1021/acs.est.0c05658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung M. K.; Rappaport S. M.; Wheelock C. E.; Nguyen V. K.; van der Meer T. P.; Miller G. W.; Vermeulen R.; Patel C. J. Utilizing a Biology-Driven Approach to Map the Exposome in Health and Disease: An Essential Investment to Drive the Next Generation of Environmental Discovery. Environ. Health Perspect. 2021, 129 (8), 085001. 10.1289/EHP8327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escher B. I.; Hackermuller J.; Polte T.; Scholz S.; Aigner A.; Altenburger R.; Bohme A.; Bopp S. K.; Brack W.; Busch W.; Chadeau-Hyam M.; Covaci A.; Eisentrager A.; Galligan J. J.; Garcia-Reyero N.; Hartung T.; Hein M.; Herberth G.; Jahnke A.; Kleinjans J.; et al. From the exposome to mechanistic understanding of chemical-induced adverse effects. Environ. Int. 2017, 99, 97–106. 10.1016/j.envint.2016.11.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker D. I.; Uppal K.; Zhang L.; Vermeulen R.; Smith M.; Hu W.; Purdue M. P.; Tang X.; Reiss B.; Kim S.; Li L.; Huang H.; Pennell K. D.; Jones D. P.; Rothman N.; Lan Q. High-resolution metabolomics of occupational exposure to trichloroethylene. Int. J. Epidemiol 2016, 45 (5), 1517–1527. 10.1093/ije/dyw218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang D.; Ladva C. N.; Golan R.; Yu T.; Walker D. I.; Sarnat S. E.; Greenwald R.; Uppal K.; Tran V.; Jones D. P.; Russell A. G.; Sarnat J. A. Perturbations of the arginine metabolome following exposures to traffic-related air pollution in a panel of commuters with and without asthma. Environ. Int. 2019, 127, 503–513. 10.1016/j.envint.2019.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeanneret F.; Boccard J.; Badoud F.; Sorg O.; Tonoli D.; Pelclova D.; Vlckova S.; Rutledge D. N.; Samer C. F.; Hochstrasser D.; Saurat J. H.; Rudaz S. Human urinary biomarkers of dioxin exposure: analysis by metabolomics and biologically driven data dimensionality reduction. Toxicol. Lett. 2014, 230 (2), 234–43. 10.1016/j.toxlet.2013.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritz B.; Yan Q.; He D.; Wu J.; Walker D. I.; Uppal K.; Jones D. P.; Heck J. E. Child serum metabolome and traffic-related air pollution exposure in pregnancy. Environ. Res. 2022, 203, 111907. 10.1016/j.envres.2021.111907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escher B. I.; Stapleton H. M.; Schymanski E. L. Tracking complex mixtures of chemicals in our changing environment. Science 2020, 367 (6476), 388–392. 10.1126/science.aay6636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters A.; Nawrot T. S.; Baccarelli A. A. Hallmarks of environmental insults. Cell 2021, 184 (6), 1455–1468. 10.1016/j.cell.2021.01.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S.; Grigoryan H.; Edmands W. M. B.; Dagnino S.; Sinharay R.; Cullinan P.; Collins P.; Chung K. F.; Barratt B.; Kelly F. J.; Vineis P.; Rappaport S. M. Cys34 Adductomes Differ between Patients with Chronic Lung or Heart Disease and Healthy Controls in Central London. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 52 (4), 2307–2313. 10.1021/acs.est.7b05554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu S. S.; Grigoryan H.; Edmands W. M.; Hu W.; Iavarone A. T.; Hubbard A.; Rothman N.; Vermeulen R.; Lan Q.; Rappaport S. M. Profiling the Serum Albumin Cys34 Adductome of Solid Fuel Users in Xuanwei and Fuyuan, China. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 51 (1), 46–57. 10.1021/acs.est.6b03955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rappaport S. M.; Li H.; Grigoryan H.; Funk W. E.; Williams E. R. Adductomics: characterizing exposures to reactive electrophiles. Toxicol. Lett. 2012, 213 (1), 83–90. 10.1016/j.toxlet.2011.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papaioannou N.; Distel E.; de Oliveira E.; Gabriel C.; Frydas I. S.; Anesti O.; Attignon E. A.; Odena A.; Diaz R.; Aggerbeck M.; Horvat M.; Barouki R.; Karakitsios S.; Sarigiannis D. A. Multi-omics analysis reveals that co-exposure to phthalates and metals disturbs urea cycle and choline metabolism. Environ. Res. 2021, 192, 110041. 10.1016/j.envres.2020.110041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leffers H. C. B.; Lange T.; Collins C.; Ulff-Mo̷ller C. J.; Jacobsen S. The study of interactions between genome and exposome in the development of systemic lupus erythematosus. Autoimmun. Rev. 2019, 18 (4), 382–392. 10.1016/j.autrev.2018.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe C. F.; Padmanabhan V.; Dolinoy D. C.; Domino S. E.; Jones T. R.; Bakulski K. M.; Goodrich J. M. Maternal environmental exposure to bisphenols and epigenome-wide DNA methylation in infant cord blood. Environ. Epigenet 2020, 6 (1), dvaa021 10.1093/eep/dvaa021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeBord D. G.; Carreon T.; Lentz T. J.; Middendorf P. J.; Hoover M. D.; Schulte P. A. Use of the “Exposome” in the Practice of Epidemiology: A Primer on -Omic Technologies. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2016, 184 (4), 302–14. 10.1093/aje/kwv325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinmuth-Selzle K.; Kampf C. J.; Lucas K.; Lang-Yona N.; Frohlich-Nowoisky J.; Shiraiwa M.; Lakey P. S. J.; Lai S.; Liu F.; Kunert A. T.; Ziegler K.; Shen F.; Sgarbanti R.; Weber B.; Bellinghausen I.; Saloga J.; Weller M. G.; Duschl A.; Schuppan D.; Poschl U. Air Pollution and Climate Change Effects on Allergies in the Anthropocene: Abundance, Interaction, and Modification of Allergens and Adjuvants. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 51 (8), 4119–4141. 10.1021/acs.est.6b04908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson O.; Rocklov J.; Lehoux A. P.; Bergquist J.; Rutgersson A.; Blunt M. J.; Birnbaum L. S. The human exposome and health in the Anthropocene. Int. J. Epidemiol 2021, 50 (2), 378–389. 10.1093/ije/dyaa231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon E.; van Velzen M.; Brandsma S. H.; Lie E.; Loken K.; de Boer J.; Bytingsvik J.; Jenssen B. M.; Aars J.; Hamers T.; Lamoree M. H. Effect-directed analysis to explore the polar bear exposome: identification of thyroid hormone disrupting compounds in plasma. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 47 (15), 8902–12. 10.1021/es401696u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- David A.; Lange A.; Abdul-Sada A.; Tyler C. R.; Hill E. M. Disruption of the Prostaglandin Metabolome and Characterization of the Pharmaceutical Exposome in Fish Exposed to Wastewater Treatment Works Effluent As Revealed by Nanoflow-Nanospray Mass Spectrometry-Based Metabolomics. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 51 (1), 616–624. 10.1021/acs.est.6b04365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian Z.; Zhao H.; Peter K. T.; Gonzalez M.; Wetzel J.; Wu C.; Hu X.; Prat J.; Mudrock E.; Hettinger R.; Cortina A. E.; Biswas R. G.; Kock F. V. C.; Soong R.; Jenne A.; Du B.; Hou F.; He H.; Lundeen R.; Gilbreath A.; Sutton R.; Scholz N. L.; Davis J. W.; Dodd M. C.; Simpson A.; McIntyre J. K.; Kolodziej E. P. A ubiquitous tire rubber-derived chemical induces acute mortality in coho salmon. Science 2021, 371, 185. 10.1126/science.abd6951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandit N.; Vanak A. T. Artificial Intelligence and One Health: Knowledge Bases for Causal Modeling. J. Indian Inst. Sci. 2020, 100, 717. 10.1007/s41745-020-00192-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao P. The Exposome in the Era of One Health. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 55, 2790. 10.1021/acs.est.0c07033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huhn S.; Escher B. I.; Krauss M.; Scholz S.; Hackermuller J.; Altenburger R. Unravelling the chemical exposome in cohort studies: routes explored and steps to become comprehensive. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2021, 33 (1), 17. 10.1186/s12302-020-00444-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doherty B. T.; Koelmel J. P.; Lin E. Z.; Romano M. E.; Godri Pollitt K. J. Use of Exposomic Methods Incorporating Sensors in Environmental Epidemiology. Curr. Environ. Health Rep 2021, 8, 34. 10.1007/s40572-021-00306-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loh M.; Sarigiannis D.; Gotti A.; Karakitsios S.; Pronk A.; Kuijpers E.; Annesi-Maesano I.; Baiz N.; Madureira J.; Oliveira Fernandes E.; Jerrett M.; Cherrie J. W. How Sensors Might Help Define the External Exposome. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14 (4), 434. 10.3390/ijerph14040434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donaire-Gonzalez D.; Curto A.; Valentin A.; Andrusaityte S.; Basagana X.; Casas M.; Chatzi L.; de Bont J.; de Castro M.; Dedele A.; Granum B.; Grazuleviciene R.; Kampouri M.; Lyon-Caen S.; Manzano-Salgado C. B.; Aasvang G. M.; McEachan R.; Meinhard-Kjellstad C. H.; Michalaki E.; Panella P.; et al. Personal assessment of the external exposome during pregnancy and childhood in Europe. Environ. Res. 2019, 174, 95–104. 10.1016/j.envres.2019.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pradal-Cano L.; Lozano-Ruiz C.; Pereyra-Rodriguez J. J.; Saigi-Rubio F.; Bach-Faig A.; Esquius L.; Medina F. X.; Aguilar-Martinez A. Using Mobile Applications to Increase Physical Activity: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17 (21), 8238. 10.3390/ijerph17218238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saberi Hosnijeh F.; Casabonne D.; Nieters A.; Solans M.; Naudin S.; Ferrari P.; Mckay J. D.; Benavente Y.; Weiderpass E.; Freisling H.; Severi G.; Boutron Ruault M.-C.; Besson C.; Agnoli C.; Masala G.; Sacerdote C.; Tumino R.; Huerta J. M.; Amiano P.; Rodriguez-Barranco M.; Bonet C.; Barricarte A.; Christakoudi S.; Knuppel A.; Bueno-de-Mesquita B.; Schulze M. B.; Kaaks R.; Canzian F.; Spath F.; Jerkeman M.; Rylander C.; Tjønneland A.; Olsen A.; Borch K. B.; Vermeulen R. Association between anthropometry and lifestyle factors and risk of B-cell lymphoma: An exposome-wide analysis. Int. J. Cancer 2021, 148, 2115. 10.1002/ijc.33369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poelman M. P.; van Lenthe F. J.; Scheider S.; Kamphuis C. B. A Smartphone App Combining Global Positioning System Data and Ecological Momentary Assessment to Track Individual Food Environment Exposure, Food Purchases, and Food Consumption: Protocol for the Observational FoodTrack Study. JMIR ResProtoc 2020, 9 (1), e15283 10.2196/15283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyotylainen T. Analytical challenges in human exposome analysis with focus on environmental analysis combined with metabolomics. J. Sep. Sci. 2021, 44 (8), 1769–1787. 10.1002/jssc.202001263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan M.; Xiang P.; Yu Z.; Zhao Y.; Yan H. Development of a high-throughput screening analysis for 288 drugs and poisons in human blood using Orbitrap technology with gas chromatography-high-resolution accurate mass spectrometry. J. Chromatogr A 2019, 1587, 209–226. 10.1016/j.chroma.2018.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valvi D.; Walker D. I.; Inge T.; Bartell S. M.; Jenkins T.; Helmrath M.; Ziegler T. R.; La Merrill M. A.; Eckel S. P.; Conti D.; Liang Y.; Jones D. P.; McConnell R.; Chatzi L. Environmental chemical burden in metabolic tissues and systemic biological pathways in adolescent bariatric surgery patients: A pilot untargeted metabolomic approach. Environ. Int. 2020, 143, 105957. 10.1016/j.envint.2020.105957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price E. J.; Palat J.; Coufalikova K.; Kukucka P.; Codling G.; Vitale C. M.; Koudelka S.; Klanova J. Open, High-Resolution EI+ Spectral Library of Anthropogenic Compounds. Front Public Health 2021, 9, 622558. 10.3389/fpubh.2021.622558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misra B. B.; Olivier M. high-resolution GC-Orbitrap-MS Metabolomics Using Both Electron Ionization and Chemical Ionization for Analysis of Human Plasma. J. Proteome Res. 2020, 19 (7), 2717–2731. 10.1021/acs.jproteome.9b00774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]