Significance

The cytoskeleton plays a central role in mechanobiology, serving both as a scaffold to support the cell’s shape and as an engine that allows the cell to exert large-scale mechanical forces. A key feature of the cytoskeleton is that it is dynamic, continually remodeling itself to respond to changing cellular needs. We use computer simulations to study this remodeling process, primarily focusing on fluctuations in the system’s mechanical energy. We observe an avalanche-like tendency for energy to accumulate slowly in the network and then dissipate in large amounts during occasional events that involve large collective network motions. This observation is consistent with recent experiments and suggests that the cytoskeleton is highly responsive to time-varying cellular cues.

Keywords: cytoskeleton, avalanche, active matter, cell mechanics

Abstract

Eukaryotic cells are mechanically supported by a polymer network called the cytoskeleton, which consumes chemical energy to dynamically remodel its structure. Recent experiments in vivo have revealed that this remodeling occasionally happens through anomalously large displacements, reminiscent of earthquakes or avalanches. These cytoskeletal avalanches might indicate that the cytoskeleton’s structural response to a changing cellular environment is highly sensitive, and they are therefore of significant biological interest. However, the physics underlying “cytoquakes” is poorly understood. Here, we use agent-based simulations of cytoskeletal self-organization to study fluctuations in the network’s mechanical energy. We robustly observe non-Gaussian statistics and asymmetrically large rates of energy release compared to accumulation in a minimal cytoskeletal model. The large events of energy release are found to correlate with large, collective displacements of the cytoskeletal filaments. We also find that the changes in the localization of tension and the projections of the network motion onto the vibrational normal modes are asymmetrically distributed for energy release and accumulation. These results imply an avalanche-like process of slow energy storage punctuated by fast, large events of energy release involving a collective network rearrangement. We further show that mechanical instability precedes cytoquake occurrence through a machine-learning model that dynamically forecasts cytoquakes using the vibrational spectrum as input. Our results provide a connection between the cytoquake phenomenon and the network’s mechanical energy and can help guide future investigations of the cytoskeleton’s structural susceptibility.

The actin-based cytoskeleton is an active biopolymer network that plays a central role in cell biology, providing the cell with a means to control its shape and produce mechanical forces during processes such as migration and cytokinesis (1–5). These cellular-level forces arise from the collective nonequilibrium activity of molecular motors interacting with the actin filament scaffold, enabling dynamic, driven-dissipative cytoskeletal remodeling (6–8). Recent experimental efforts have uncovered a remarkable phenomenon exhibited by cytoskeletal networks in vivo: These networks undergo large, sudden structural rearrangements significantly more frequently than predicted by a Gaussian distribution (9, 10). Heavy-tailed distributions of event sizes are well known in seismology, where the Gutenberg–Richter law describes the power-law relationship between the energy released by an earthquake and such an earthquake’s frequency (11, 12). Due to this analogy, the term “cytoquake,” which we adopt here, has been coined by experimenters to describe large cytoskeletal remodeling events. In previous work, we have reported the first in silico observations of this phenomenon, appearing as heavy tails in the distributions of mechanical energy released by cytoskeletal networks (13). These findings suggest that avalanche-like processes may play a fundamental role in cytoskeletal dynamics.

The physics underlying cytoquakes is not well understood, as current explanations based on experimental data are mostly speculative and rely on qualitative comparisons to systems amenable to computational study, which similarly exhibit nonexponential relaxation, such as jammed granular packings and spin glasses (9, 10, 14, 15). In particular, it is not known whether large cytoskeletal displacements actually arise from an avalanche-like process of slow energy storage and fast, large events of energy release. Alternative explanations of heavy-tailed distributions of cytoskeletal displacements that do not involve avalanche-like dynamics have also been considered. For instance, heterogeneity in the spatial distribution of molecular motors has been proposed as a possible mechanism for non-Gaussian distributions of tracer particle displacements (7, 16). Here, we describe a detailed numerical study focused on the mechanical energy of cytoskeletal networks exhibiting large displacements. We find that the statistics of energy accumulation and release support the hypothesis of avalanche-like dynamics occurring in cytoskeletal networks and, thus, that avalanche-like dynamics do at least contribute to the observed heavy-tailed distributions of cytoskeletal displacements.

In addition, in previous studies, little emphasis has been given to the possible biological roles played by cytoquakes. We propose one such role, that these large mechanical fluctuations are concomitant with a large susceptibility to mechanical forces or chemical perturbations, allowing the cytoskeleton to be highly sensitive to physiological cues arriving via various cell-signaling pathways (17). Dynamic instability is already an acknowledged feature of certain cytoskeletal components, such as microtubules and filopodia (18). A similar design principle may also apply to larger cytoskeletal structures to allow fast remodeling. For instance, avalanche-like dynamics may serve a useful purpose in the lamellipodia of migrating cells, which probe local chemical gradients and must quickly collapse protrusions in unsuccessful search directions, as well as adaptively remodel their structure in response to changing mechanical loads (2, 19). However, to investigate such possible biological roles, we first need a more detailed account of the underlying causes of the observed large structural rearrangements, which is the subject of this paper.

Here, we perform detailed simulations of a minimal cytoskeletal model system using the software package MEDYAN (Mechanochemical Dynamics of Active Networks) (20). Our main qualitative result is that there is a significant asymmetry between how cytoskeletal networks accumulate and release mechanical energy. While both accumulation and release statistics are heavy-tailed, the magnitudes of energy release are more broadly distributed than those of energy accumulation. Several measures of network dynamics are also found to be distributed asymmetrically for energy release and accumulation, including the network displacement, the localization of tension, and the projection of the network motion onto the vibrational normal modes. These results support an avalanche-like picture of slow energy accumulation punctuated by fast, broadly distributed events of energy release that involve a collective structural rearrangement of the network. The asymmetric energy fluctuations are found to be robust against changes in chemical concentrations and system size, suggesting that avalanches are intrinsic to cytoskeletal network dynamics. We further establish a connection between cytoquakes and mechanical stability, both through the observed spatial delocalization of tension during cytoquakes and the machine-learning-assisted ability to dynamically forecast cytoquakes using the Hessian eigenspectrum of the mechanical energy function. This implies that mechanical instability, as encoded in the Hessian eigenspectrum, precedes incipient cytoquakes, which then act to homogenize tension in the network. At the end of the paper, we pose several open questions based on these results, which can help to guide future investigations into cytoquakes and their possible physiological functions.

Results

Energy Fluctuations Are Asymmetric, Heavy-Tailed, and Self-Affine.

We study a subsystem of the full cytoskeleton called an actomyosin network. This consists of semiflexible actin filaments and associated proteins, including active molecular motors (e.g., minifilaments of nonmuscle myosin IIA [NMIIA]) and passive cross-linkers (e.g., -actinin). An actomyosin network as represented in simulation is visualized in Fig. 1. The actin filaments hydrolyze adenosine triphosphate (ATP) molecules in a directed polymerization process, which reaches a steady state called “treadmilling” (21). The myosin minifilaments (200 in length) transiently bind to pairs of actin filaments and also hydrolyze ATP as fuel to walk along the filaments, generating motion and mechanical stresses. These active process drive the network away from equilibrium. The cross-linkers (35 ) bind more stably to nearby filaments, serving to transmit the force produced by motors and to both store and, through unbinding, dissipate the resulting energy, heating the environment (22–28). Dissipation of stored mechanical energy also occurs as filaments relax out of strained configurations, in a manner that depends on mutual constraints that filaments exert on each other through bound cross-linkers and motors. Additionally, the rates of motor walking and unbinding, as well as of cross-linker unbinding, depend exponentially on the forces sustained by these molecules, giving rise to nonlinear coupling between the mechanical state of the network and its chemical propensities (29, 30). These processes by which the ability of the network to mechanically relax depends on its current state set the stage for avalanche-like dynamics.

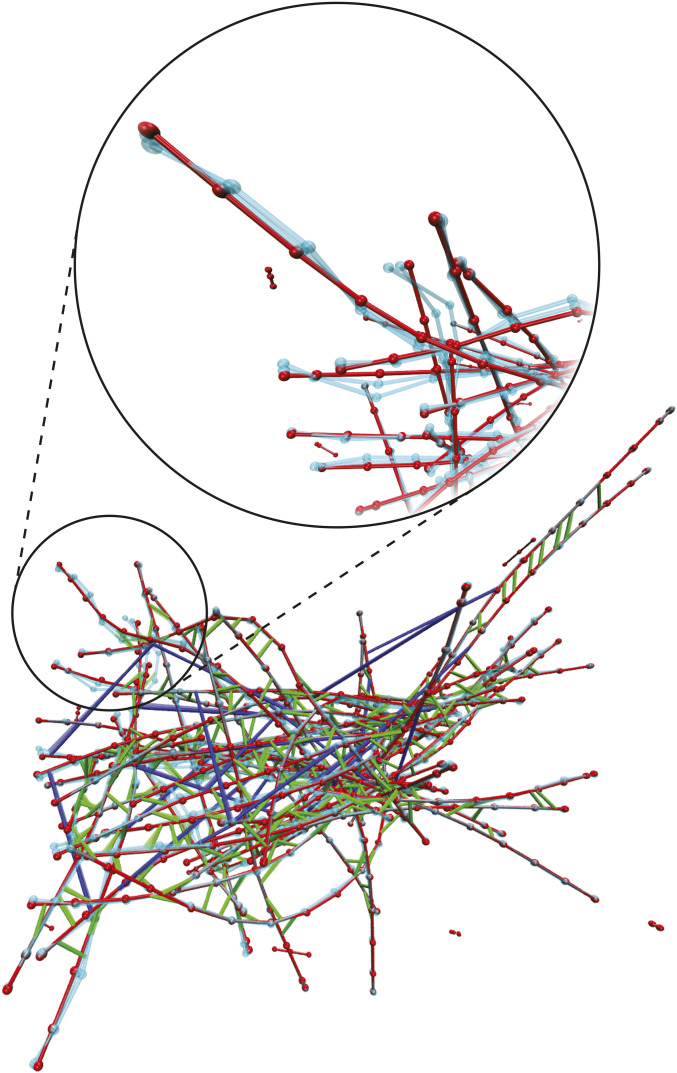

Fig. 1.

A snapshot from a MEDYAN trajectory of an actomyosin network in a box for the condition (Materials and Methods). Actin filaments are shown in red, -actinin is shown in green, and myosin motors are shown in blue. Beads representing the joined points (i.e., hinges) of thin cylinders (at most long) are visualized as red spheres. The cyan filaments represent motion of the network corresponding to a soft, delocalized vibrational mode determined from Hessian analysis, as described in Normal Mode Decomposition Probes Network’s Mechanical State. In Inset, we zoom in on part of the network and exclude associated proteins to show greater detail of this vibrational motion.

Using MEDYAN, we performed simulations of small cytoskeletal networks consisting of 50 actin filaments in 1- hard-walled cubic boxes with varying concentrations of -actinin cross-linkers () and of NMIIA myosin-motor minifilaments () (13, 20, 31–33). We omit here other associated proteins, such as the branching agent Arp2/3, finding that our minimal system is sufficient to produce heavy-tailed distributions of event sizes, although it has recently been discovered that branching acts to enhance avalanche-like processes (34). MEDYAN simulations combine stochastic chemical dynamics with a mechanical representation of filaments and associated proteins (see SI Appendix, Description of MEDYAN Simulation Platform for a detailed outline of the MEDYAN model). Simulations proceed iteratively in a cycle of four steps: 1) stochastic chemical simulation for a time (here, ), 2) computation of the resulting new forces, 3) equilibration via minimization of the mechanical energy, and 4) updating of force-sensitive reaction rates, such as slip-bonds of cross-linkers, catch-bonds of motors, and motor stalling. Recent extensions to the MEDYAN platform allow calculation of the change in the system’s Gibbs free energy during each of these steps (13, 35), originally applied to study the thermodynamic efficiency of myosin motors in converting chemical free energy to mechanical energy under various conditions of cross-linker and motor concentration. We employ this methodology here and focus on the statistics of the system’s mechanical energy as it self-organizes.

We first characterize the observed occurrence of avalanche-like dynamics in these simulations. The simulations begin with short seed filaments that quickly polymerize (tens of seconds) to their steady-state lengths. Following this, the slower process (hundreds of seconds) of primarily myosin-driven self-organization occurs, which for most conditions, results in geometric contraction to a percolated network (Movie S1) (26, 36). The mechanical energy fluctuates near a quasi-steady state (QSS) value, which we analyze as a stochastic process. In Fig. 2A, we display the trajectory of for condition (with -actinin concentration and motor concentration ; see Materials and Methods for a description of the experimental conditions). We tracked the net changes of the mechanical energy resulting from each complete cycle of simulation steps (1)–(4). The total energy is a sum over the molecular components in the network, i.e., filaments, motors, and cross-linkers, as well as the excluded volume repulsion between nearby filaments. We show this decomposition of the energy into these components in SI Appendix, Fig. S1. For the purpose of analyzing the observed asymmetric heavy tails in the distribution of , we treated the negative increments (energy release) and positive increments (energy accumulation) as samples from separate distributions with semi-infinite domains. The complementary cumulative distribution functions (CCDFs, or “tail distribution,” the probability of observing a value of the random variable above a threshold , as a function of ) of the observed samples collected from all five runs at QSS are illustrated in Fig. 2B. Both distributions display striking heavy tails relative to a fitted half-normal distribution. The CCDFs are better fit by stretched exponential (Weibull) functions of the form (37)

| [1] |

We justify this choice of distribution by constructing Weibull plots, as discussed in SI Appendix, Weibull Plots. We find for and for with uncertainty taken over the five runs, indicating shallower tails for energy release compared to energy accumulation. We also measured parameter that indicates non-Gaussianity:

| [2] |

where is the moment about zero; for a half-normal distribution , and quantifies heavy-tailedness. We find for and for . This, along with the shallower tails of the fitted stretched exponential functions, indicates greater deviation from Gaussianity for energy release compared to energy accumulation. These results support the picture that, typically, energy accumulates comparatively slowly and is released via large occasional events.

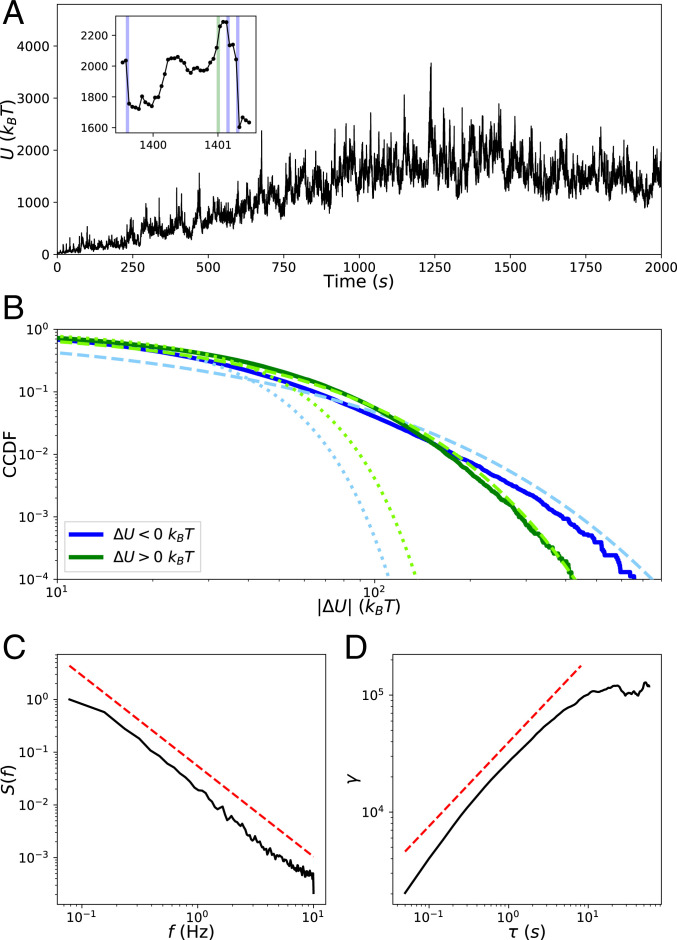

Fig. 2.

Statistics of . (A) Trajectory of the network’s mechanical energy for condition (Materials and Methods). (A, Inset) A blow-up of the trajectory to show instances of rare events of energy release (; blue) and accumulation (; green). (B) CCDFs of (blue) and (green) collected from five runs when the system is at QSS after 1,000 . Dotted lines in lighter colors represent fits to the data of a half-normal CCDF, and dashed lines represent fits of stretched exponentials. (C) The normalized power spectral density of for a single run at QSS from which the spectral exponent is determined by fitting a power law, shown offset in red. (D) The semivariogram obeys the scaling relationship over the scaling range.

We next analyze the temporal correlations of at QSS. A self-affine stochastic time series , for which and have the same statistics for any scaling parameter , has a power spectral density exhibiting a power-law dependence on frequency : , where the spectral exponent is the persistence strength, related to the color of the signal (38, 39). We find for , as shown in Fig. 2C. With this value of , is classified as a pinkish-brown signal, implying that it is nonstationary and has temporally anticorrelated increments . Self-affine time series further obey the theoretical relationship when , where is the Hausdorff exponent determined from the scaling of the semivariogram

| [3] |

and where the overbar represents temporal averaging (40, 41). We find that this relationship is satisfied by , as shown in Fig. 2D, yielding and confirming that is self-affine. Such non-Markovian and self-affine time series and spatial patterns commonly arise in various complex geophysical processes (e.g., the temporal variation of riverbed elevation), further supporting the analogy between the cytoskeleton and earth systems (42, 43).

Distinguishing Features of Cytoquakes.

We find that cytoquakes, defined throughout as simulation cycles for which , are correlated with several changes in the state of the network. This cutoff at is chosen to lie in the tail of the distribution of (Fig. 2), but its specific value does not significantly affect our conclusions. A discussion of the conversion of the numerical data into discrete categories can be found in SI Appendix, Binning. In Fig. 3, we show that rare large events of energy accumulation correspond to a greater than usual number of myosin-motor steps, whereas rare large events of energy release correspond to greater than usual total displacement of the actin filaments and a slightly greater number of linker unbinding events. The displacement between filaments from to is calculated by triangulating the area between the two filament configurations and dividing the area by the filament length, as described in SI Appendix, Filament Displacements. The total filament displacement at time is computed as the sum of displacements over all filaments during the time interval . This quantity is found to be largest during cytoquake events. Furthermore, these large total displacements do not come from highly localized motions. Instead, they depend on many filaments each displacing an unusually large amount, as shown in Fig. 4, where the filaments are ranked according to their displacement during a cycle. For cytoquake events, the typical displacement at almost every rank is greater than the corresponding displacement at that rank for other cycle types. This agrees with the notion of cytoquakes as a large and collective structural rearrangement of the network.

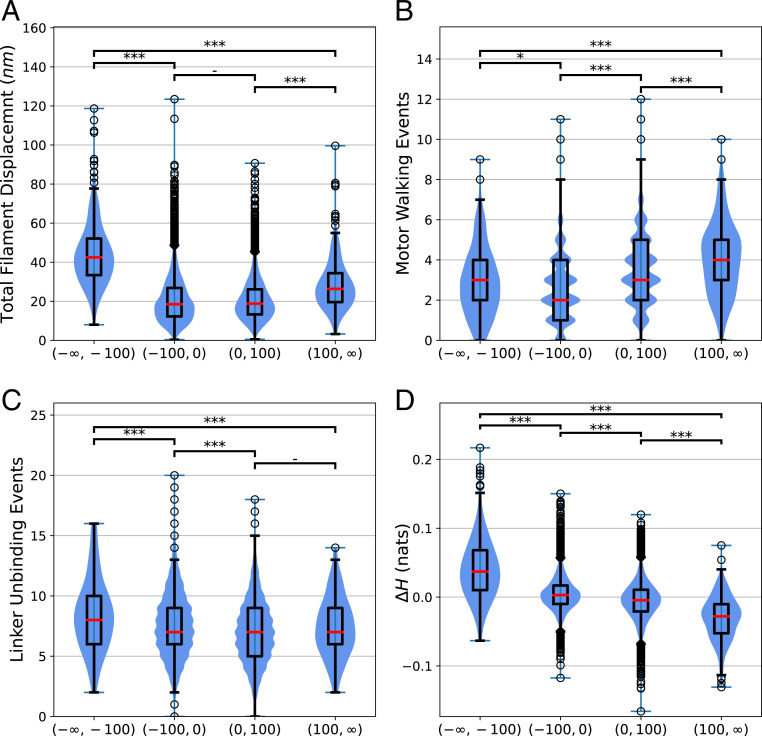

Fig. 3.

(A) Differences in the total filament displacement between simulation cycles for which , cycles for which , cycles for which , and, finally, cycles for which . To compare these distributions, we first performed a Kruskal–Wallis test on the group, which indicated statistically significant between-group differences. A post hoc two-sided Wilcoxon rank-sum test was then performed on pairs of distributions using a Bonferroni correction factor of 6 on the significance level to account for multiple comparisons. The corrected value of the Wilcoxon rank sum test between pairs of cycle types is reported as follows: -not significant (); *significant at level 1 (); **significant at level 2 (); ***significant at level 3 () (44). The red bar of the box plots represent the median, and the scatter-plot data represent detected outliers. (B) Differences in the number of motor walking events between the different cycle types as just described. (C) Differences in the number of -actinin unbinding events between the different cycle types. (D) Differences in the changes in Shannon entropy of the spatial tension distribution of network tension between the different cycle types.

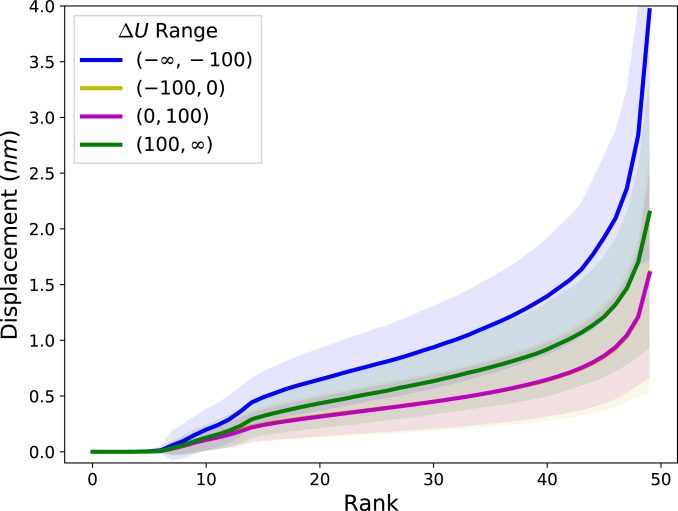

Fig. 4.

Rank-size distribution of the displacements experienced by each of the 50 filaments during simulation cycles when is in different ranges, in units of . For each cycle, the filaments are ranked according to their displacement, and these ranks are plotted against the corresponding displacement. The average and SD of these rank-displacement curves are taken over each cycle in a given category. The curves for the categories and are nearly coincident. This data are collected from one run of condition at QSS.

We also observed cytoquakes to induce a spatial homogenization of the tension sustained by the network during large events of energy release, as quantified by changes in the Shannon entropy of the spatial tension distribution (Fig. 3D). The tension distribution is constructed by discretizing the simulation volume of into a grid of voxels indexed by and computing the proportion of the total network tension belonging to the mechanical elements (filament cylinders, cross-linkers, and motors) inside each voxel. Additional details for the calculation of can be found in Materials and Methods. The combination of large, collective rearrangement and a spatial homogenization of tension supports the interpretation of cytoquakes as an avalanche-like event of energy release.

Asymmetric Statistics Are Robust across Concentrations and System Size.

We next discuss how these results generalize to different concentrations of associated proteins and different system sizes. Five concentrations of -actinin (ranging from 0.17 to 5.48 ) and five concentrations of myosin minifilaments (ranging from 0.003 to 0.08 ) were tested with a constant G-actin monomer concentration of 13.3 , in the regime of physiological concentrations (45). At the lowest concentrations of cross-linkers and motors, the network did not contract, representing a very different actomyosin phase, to which we omit comparisons. For all of the conditions producing contracting networks, we found that asymmetric heavy-tailed distributions of persist, with large values of the non-Gaussian parameter for () and (), although for negative increments was observed to decrease with the motor concentration (SI Appendix, Fig. S2). We conclude that the avalanche-like energy fluctuations discussed above are not highly sensitive to associated protein concentrations. These fluctuations may depend on the parameters of the force-sensitive reaction rates (which are taken here to correspond to experimental values), but we leave this interesting question for future work.

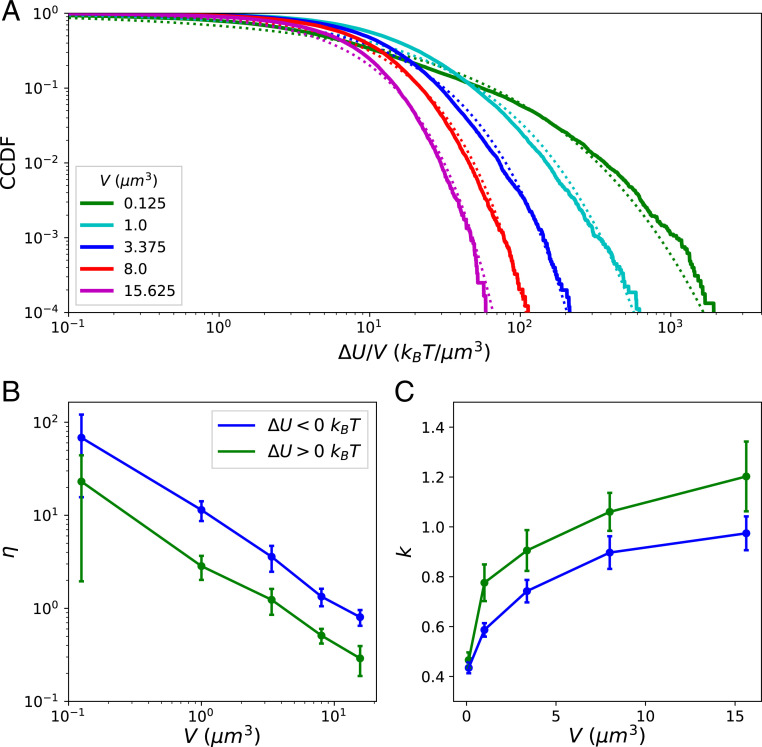

We performed a finite-size scaling study by holding the concentrations of condition fixed (with -actinin concentration and motor concentration ) and varying the system volume . Larger systems reach QSS at later times, and our simulations of larger systems did not reach QSS in the allotted computational time. As a result, we collected samples of for these systems on the approach to QSS, from to , once the networks had all nearly fully percolated (i.e., nearly all filaments belonged to a single component connected by cross-linkers), trusting that the relevant scaling behavior could still be observed. Stretched exponential functions approximately fit the distributions of and for all system sizes (see Fig. 5A for the fits of ). Larger systems displayed steeper tails, as indicated by the observed power-law decay of for and (Fig. 5B), although, interestingly, for was larger than that for by a constant factor of roughly 3 for all systems sizes. The steeper tails were also evidenced by the slow growth of the Kohlrausch exponents with (Fig. 5C). Thus, the distributions of energy release and accumulation across the entire network become narrower and more Gaussian for large systems. This, in contrast to driven-dissipative systems that exhibit self-organized criticality (SOC), suggests the existence of some intrinsic and finite scale for avalanche-like releases of energy in cytoskeletal networks. By summing over many local energy fluctuations of this finite scale, the distribution of the fluctuations in the total energy becomes increasingly Gaussian for large systems, owing to the central limit theorem. This intrinsic scale may be partly determined by the nonconservative transfer (dissipation) of mechanical energy as it spreads through the network during avalanches (24, 46).

Fig. 5.

(A) CCDFs of normalized by the system volume collected for five runs for increasing system sizes plotted against the fitted stretched exponential functions. (B) The non-Gaussian parameters for and are plotted with uncertainty taken over the different runs. (C) The Kohlrausch exponents for and .

Local vs. Global Metrics.

Existing experimental studies of cytoquakes define them as large local displacements of the cytoskeleton probed using transmembrane-attached microbeads or flexible micropost arrays, rather than as large changes in the cytoskeleton’s total energy , as done here (9, 10). To roughly compare our results to experiments, we made the corresponding local measurements of the displacements of individual filaments. Rather than summing over all filaments, we tracked each filament individually and measured the set (where is the number of filaments) of the non-Gaussian parameter corresponding to each filament ’s distribution of displacements from 300 to . The calculation of filament displacements is described in SI Appendix, Filament Displacements. We find that the resulting distributions are heavy-tailed with values of the non-Gaussian parameter for most filaments in the range (Fig. 6). This finding is in semiquantitative agreement with in vivo measurements on micropost arrays, whose displacements have distributions characterized by (10). In addition, we find the distribution of itself to be heavy-tailed, also in agreement with the micropost experiments. We next estimated the instantaneous filament speed as the filament displacement divided by . We find the typical actin filament displacement speeds () to be consistent in order of magnitude with separate in vitro experiments on disordered, contractile networks, which estimate this speed as (47). These corroborations with existing measurements suggest that our simulations of a minimal cytoskeletal model system can approximately reproduce experimentally observed cytoskeletal dynamics. We finally mention in connection to experiments that it has recently been argued that more detailed understanding of mechanical dissipation by cytoskeletal networks should help to precisely control traction-based measurements of cellular force production (28). The discovery of avalanche-like dynamics in cytoskeletal networks reported in this and previous studies may help to resolve this experimental difficulty.

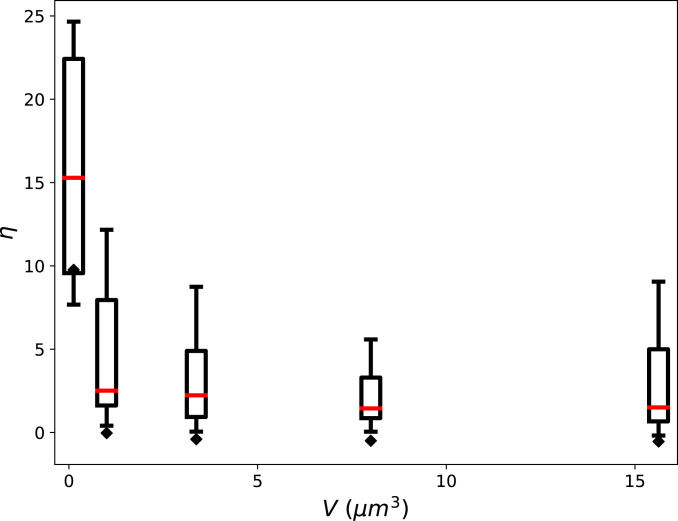

Fig. 6.

Plots for different simulation volumes of the distributions of non-Gaussian parameter of the distributions of individual filament displacements. The box and whisker plots summarize the distribution of for all filaments in the system, with the median shown as a red bar, the box extending from the first to the third quartiles, and the whiskers extending across the range of , omitting outliers. The black diamonds indicate the value of obtained when instead of tracking each filament’s displacement individually, the total summed displacement of all filaments from time point to time point is tracked. These global measurements of displacement are more Gaussian (with ) than the corresponding local measurements obtained from tracking filaments individually.

The local measurements , obtained by tracking each filament individually, can be compared to global measurements, obtained by summing over every filament to obtain the total displacement. The distribution of total displacements is closer to Gaussian, characterized by for most volumes tested (Fig. 6). As with the increasing Gaussianity of for large systems, this can be attributed to the central limit theorem since many filaments were summed over to determine the total displacement. We conclude that in large systems, metrics can be heavy-tailed when measured locally, but Gaussian when measured globally. This distinction between local and global measurements may be important in interpreting future studies of anomalous statistics in cytoskeletal self-organization.

Normal Mode Decomposition Probes Network’s Mechanical State.

Having described the statistics of the increments , we next aimed to connect the occurrence of cytoquakes, defined as large values of , to the cytoskeletal network’s mechanical stability. To this end, we implemented a method to compute the Hessian matrix of the mechanical energy function . The eigen-decomposition of is , where is the number of mechanical degrees of freedom in the system, which comprises “beads” that are used to discretize the actin filaments. is related to the mechanical stability of the cytoskeletal network: The eigenvectors are the normal vibrational modes of the network, and the eigenvalues indicate the stiffness () and stability () of the corresponding mode. Example vibrational modes are illustrated in Movies S2–S5. We drew inspiration for studying in the current context from several sources: In single-molecule molecular dynamics studies, the saddle points of (i.e., points in the landscape with some imaginary frequencies) are associated with transition states (48, 49); studies of polymer networks show that internal stresses produce nonfloppy vibrational modes, even below the isostatic threshold (50); in simulations of glass-forming liquids, the instantaneous normal-mode spectrum allows inference about proximity to the glass transition and determination of incipient plastic deformation regions (51–53); in deep-learning models for predicting earthquake aftershock distributions, it was found that certain metrics also related to stability (e.g., the von Mises criterion) are informative model inputs (54, 55).

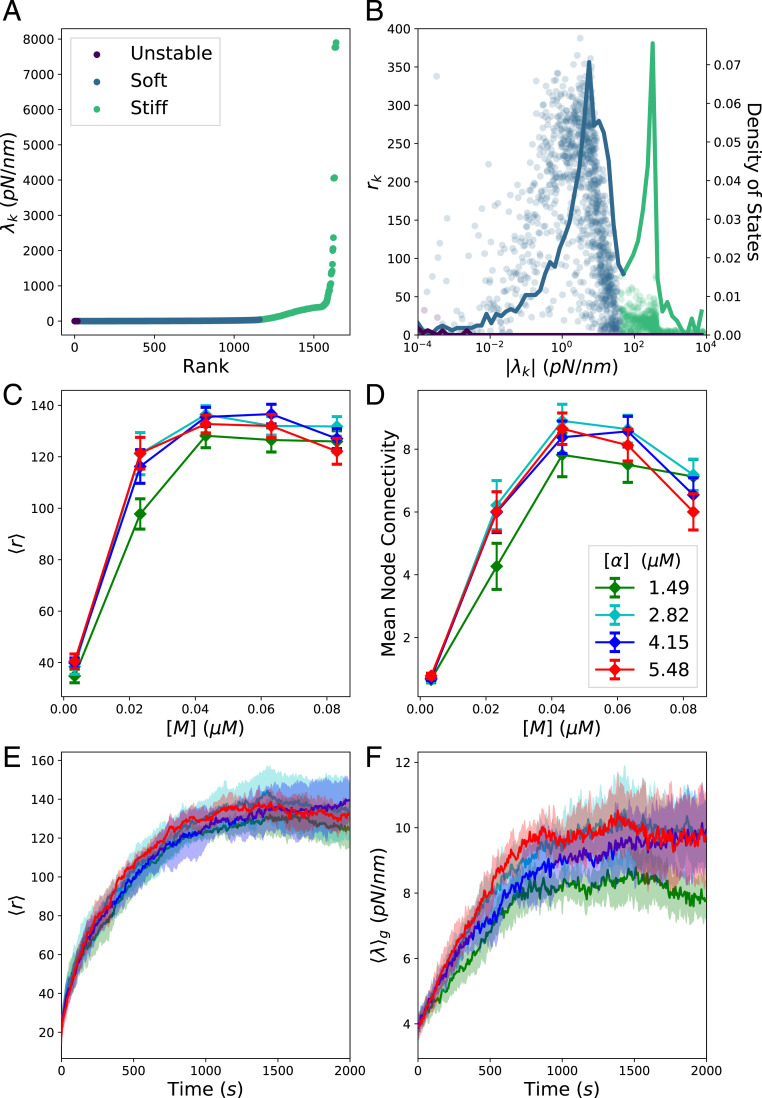

We briefly digress from the results on cytoquakes to describe some interesting observed trends of metrics defined on . We distinguish between unstable, stable, soft, and stiff modes: For unstable modes, , for stable modes, , for soft modes , and for stiff modes, , where we define the threshold to discriminate between the twin peaks in the density of states (Fig. 7B). The set is visualized with these modes labeled in Fig. 7A for a QSS time point of condition . A very small number of unstable modes persist after each minimization cycle, later iterations stopping once the maximum force on any bead in the network is below a threshold (here 1 ). Thus, the minimized configurations are, in fact, saddle points of ; this is expected, as it is known from the theory of minimizing loss functions that the ratio of saddle points to true local minima increases exponentially with the dimensionality of the domain (56). We expect that in the space of all possible network topologies (i.e., patterns of cross-linkers and motors binding to filaments), the energy landscape will be rugged, leading to the well-appreciated glassy dynamics of nonequilibrium cross-linked networks (57, 58). For a fixed topology, however, which is the result of the chemical reactions occurring during step (1) of the iterative simulation cycle, the energy landscape should be smooth (i.e., not rugged) with respect to the beads’ positions, with a single nearby local minimum being sought during mechanical minimization in step (3). The residual unstable modes are therefore thought to be an unimportant artifact of thresholded stopping in the conjugate-gradient minimization routine, and not representative of some physical feature of cytoskeletal networks. The observed quantitative dependence of the number of residual unstable modes on supports this conclusion and is illustrated in SI Appendix, Fig. S11.

Fig. 7.

Metrics defined on Hessian eigen-decomposition. (A) Ordered eigenspectrum at a QSS time point for condition . (B) Scatter plot of the pairs (circles) plotted against the density of states (solid line), i.e., the proportion of eigenvalues between and . (C) The mean value at QSS of for the stable modes for various conditions . The conditions with low linker concentrations are not visualized, as these networks did not percolate and obscure visualization for the remaining conditions. The mean is taken over the last 500 and over different runs. (D) The mean value of the mean node connectivity for various conditions. (E) Trajectories of of the stable modes as the network self-organizes for the conditions , , , and , where the color indicates the -actinin concentration as in D, and with the mean and SD taken over the different runs. (F) Similar trajectories of the geometric mean of the stable modes .

We quantify the number of degrees of freedom involved in a given normalized eigenvector using the inverse participation ratio (51):

| [4] |

If the eigenmode involves only one degree of freedom, then one component of will be one and the rest will be zero, and . On the other hand, if the eigenmode is evenly spread over all degrees of freedom, then each component , and . In Fig. 7B, we plot for the unstable, soft, and stiff modes, along with the density of states, showing that the soft modes involve many degrees of freedom, while the stiff and unstable modes are comparatively localized.

We find that the mean value of over the stable modes varies nonmonotonically with myosin-motor concentration and -actinin concentration (Fig. 7C). To understand this trend, we implemented a mapping from the cytoskeletal network into a graph and measured its mean node connectivity, a purely topological measure of network percolation. The graph was constructed to capture the cross-linker binding topology of cytoskeletal networks. Nodes in the graph correspond to actin filaments, and weighted edges (which may be thresholded and converted to binary edges in an unweighted graph) correspond to the number of cross-linkers connecting the pair of filaments. The mean node connectivity is defined as the average over all pairs of nodes in the unweighted graph of the number of edges necessary to remove in order to disconnect them, thus quantifying the typical number of force chains between filaments or, equivalently, the extent of network percolation (59, 60). Revealingly, the mean node connectivity correlates closely with for the stable modes across the various conditions (Fig. 7 C and D). We also find the number of connected components of and of the graph’s adjacency matrix to match for most time points, supporting this connection between network topology and stable mode delocalization. Intermediate concentrations of myosin motors can enhance the network percolation, but as continues to increase, the motors act to disconnect cross-linked network structures, causing the mean node connectivity and to decrease (61). In SI Appendix, Degree Distributions, we plot the distributions of the weighted node degree and connectivity. These plots indicate that the networks investigated here are not critically connected, and, thus, network connectivity does not by itself explain heavy-tailed energy fluctuations. However, it would be interesting to investigate in future work how these two aspects of actomyosin networks are interrelated. It may be the case that heavy tails in the distribution of network connectivity can allow for heavier tails in the distribution of .

We observed that as a network contracts and becomes percolated during the process of myosin-driven self-organization, the stable modes steadily delocalize ( increases) and stiffen (the geometric mean increases), as shown in Fig. 7 E and F. During this process, we also witnessed a qualitative change in the level-spacing statistics of the very soft and delocalized modes (, ) from a Poisson to a Wigner–Dyson distribution (SI Appendix, Fig. S3). This indicates that in the percolated state, these vibrational modes interact and exhibit level repulsion, similar to soft particles near the jamming transition (10, 14, 62, 63). Future studies may reveal further similarities between these systems and other marginally stable solids (58, 64).

Cytoquakes Are Preceded by Mechanical Instability and Deform along Soft Modes.

Can the eigen-decomposition of the Hessian matrix be used to forecast cytoquake occurrence? Intuition suggests that, by analogy with the connection between imaginary frequencies (i.e., unstable modes) and molecular transition states, the vibrational modes of the cytoskeletal network may contain information that a large structural rearrangement is poised to occur (48, 49). To test this idea, and without detailed a priori knowledge about which features in would be informative, we implemented a machine-learning model using the eigen-decomposition as the input and outputting the predicted probability of observing a large event of energy release () occurring within the next . As detailed in SI Appendix, Machine Learning Model, we found that, indeed, the Hessian eigenspectrum contains sufficient information to forecast cytoquake occurrence with significant accuracy compared to a random model. We first reduced the dimensionality of using principal component analysis, finding that 30 dimensions sufficed to explain of the variance across time points, and then used the reduced input in a three-layer feed-forward neural network. We validated our model using receiver operating characteristic curves, achieving an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.70 when using data from five runs of condition . This improvement in prediction performance over a random model (which would have an AUC of 0.5) implies that mechanical instability, as encoded in the Hessian eigenspectrum, precedes the occurrence of cytoquakes.

To further study the connection between cytoquakes and mechanical stability, we measured the projections of the network’s displacements onto the vibrational normal modes . Network displacements were found by tracking the movement of each of the beads during simulation cycles. As a working approximation, beads that depolymerized during a cycle were assigned a displacement of zero, and beads that newly polymerized were not assigned elements in . The -dimensional displacement vectors were then normalized to have unit length. We define

| [5] |

as the projections of onto the eigenmodes , which obey owing to the normalization of and . Thus, the quantity is the weight of the displacement along the eigenmode. With this, we define the effective stiffness

| [6] |

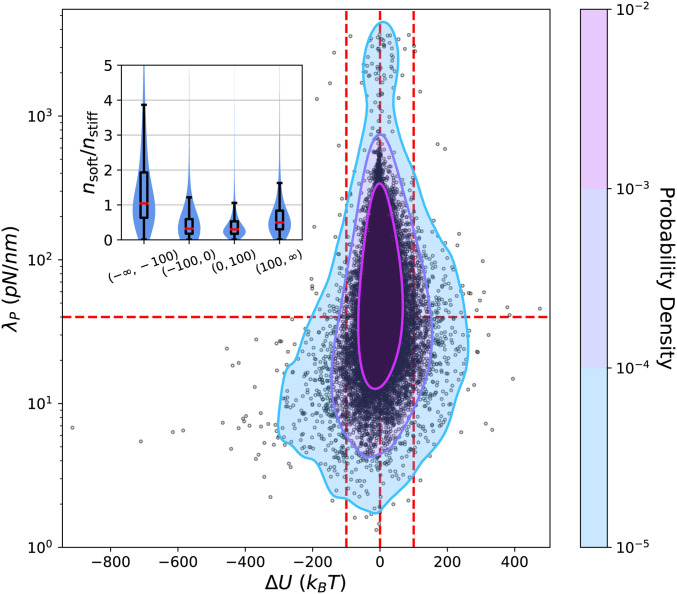

as the displacement-weighted average of the eigenvalues. In Fig. 8, we display a scatter plot of the pairs , measured during QSS for a run of condition , along with a kernel density estimate of their joint probability density function (PDF). We again distinguish between soft () and stiff () eigenmodes, where separates the twin peaks in the density of states (Fig. 7B). The structure of the joint PDF is markedly asymmetric about and shows that during cytoquake events is almost always soft, whereas for all other simulation cycles, could be soft or stiff with similar probabilities. Because soft modes inherently involve a large number of degrees of freedom, as illustrated in Fig. 7B, we also consider

| [7] |

as the weight of the displacement along eigenmode per degree of freedom involved in the eigenmode, where is the inverse participation ratio defined in Eq. 4. We define and as the mean of over the soft and stiff subsets. Values of for different simulation cycle types are displayed in Fig. 8, Inset, showing that typically only during cytoquakes. Based on this analysis, we conclude that during the large collective rearrangements corresponding to cytoquakes, cytoskeletal networks exhibit enhanced displacement along the soft vibrational modes. We qualify these results by observing that, since cytoquakes involve particularly large network displacements, it may be inappropriate to interpret them using the local harmonic approximation to implicit in Hessian analysis (53). In addition, changes in network topology from linker and motor (un)binding cannot be captured using normal mode decomposition of instantaneous network configurations. The eigenspectrum still informs on the stability of the energy-minimized configuration before a cytoquake, but caution should be used in interpreting the cytoquake motion from to as decomposing cleanly into noninteracting motions along the normal modes . We leave a detailed analysis of the anharmonicity of cytoquake deformations to future work.

Fig. 8.

Scatter plot of the pairs , measured during QSS for a run of condition . From these points, a Gaussian kernel density estimate of the joint PDF (treating on a log-scale) is constructed and shown as a contour plot. Red guidelines demarcate regions of interest. (Inset) Combination violin and box-and-whisker plots showing the ratio for different categories of simulation cycles; c.f. Fig. 3. Inset is not blocking any of the scatter-plot data.

Discussion

We have presented evidence supporting the following picture of active cytoskeletal network self-organization: Cytoskeletal networks explore a rugged mechanical energy landscape in a stochastic process characterized by occasional, sudden jumps out of metastable configurations (57, 58). These jumps entail non-Gaussian dissipation of mechanical energy and are accomplished by an avalanche-like process of spreading destabilization, resulting in a collective structural rearrangement and a homogenization of tension. These collective motions have large projections along the soft, delocalized vibrational modes, and, furthermore, properties of these modes can be used to predict when such relaxation events will occur. The key finding supporting the interpretation of cytoskeletal dynamics as avalanche-like is the marked asymmetry about zero in the distribution of (Figs. 2B and 5 B and C). In addition, several key quantities, including filament displacements (Figs. 3A and 4), tension delocalization (Fig. 3D), and effective stiffness of the motion (Fig. 8), are distributed asymmetrically about , supporting the picture described above.

An interesting possible interpretation of the heavy tails of is that cytoskeletal networks are at a point of SOC (40, 41, 65–67). Technical definitions of what constitutes SOC behavior are not universally agreed upon, but we may follow the definition of ref. 41, which states that SOC systems must have event-size distributions that tend to a power law in the limit of an infinite system size and a temporal signal that integrates a pink noise process, giving for the signal. The observed distribution of for this system size is fit by a stretched exponential function and has . Further, the distributions of become increasingly Gaussian for large system sizes (Fig. 5). We thus conclude that cytoskeletal networks for these physiological conditions display noncritical dynamics, at least as measured by using the global energy release . The motor walking in the system may not be sufficiently slow to yield SOC behavior, which requires a sharp separation of time scales between slow driving and fast dissipation, and the nonconservative transfer of mechanical energy between network components may also play a role (13, 24, 46, 67, 68). We note, however, that recent studies have indicated that branched cytoskeletal networks polymerizing against a flexible membrane can produce shape fluctuations of the membrane that exhibit true SOC, leaving open the question of whether criticality is an inherent feature of cytoskeletal dynamics (69, 70).

Instead of scale-free fluctuations, we conjecture that there exists a finite and intrinsic scale for avalanche-like releases of energy that, when summed over sufficiently large systems to obtain the global measure , yields an approximately Gaussian distribution (Fig. 5). An important next question is then what sets this scale and how it may be measured. We expect that the nonconservative transfer of mechanical energy through the network is one factor that attenuates the avalanches. This nonconservation of mechanical energy arises from damping by the cytosol, accounted for in simulation through periodic minimization of the energy following stochastic chemical activity (SI Appendix, Description of MEDYAN Simulation Platform). In the lattice-based Olami–Feder–Christensen model of earthquake systems, nonconservation of energy was shown to introduce a stretched exponential cutoff to the power-law distribution of event sizes, supporting this idea (46, 71). A rough estimate of the intrinsic energy scale of avalanches can be obtained from the SD of the approximately Gaussian distributions of for large systems. However, a detailed measurement of the spatiotemporal scale will require spatially resolving the measured energy fluctuations, which was not done in this study. In addition, in this study, the temporal extent of avalanches was assumed fixed at the smallest resolved time interval (see SI Appendix, Dependence on δt and FT for a discussion of how varying affects the distribution of ). Characterizing in-depth the spatiotemporal scales of avalanches is thus an important avenue for future work.

In addition to the question of what characterizes the spatiotemporal scale of cytoskeletal avalanches, several other open questions can be posed, based on the results presented here. First, we may ask about the role of force-sensitive reaction rates, including cross-linker unbinding and motor walking and unbinding, in modulating cytoquakes (see SI Appendix, Description of MEDYAN Simulation Platform for details of these reactions). The nonlinear coupling introduced by this force sensitivity between the local tensions in the network and the local relaxation propensities is expected to strongly accentuate avalanche-like dynamics, but in this study, we held the force-sensitive reaction-rate parameters fixed at their physiological values. It would also be interesting to vary the mechanical and geometrical properties of the network, such as the molecular elastic constants and the typical length of the myosin motors. A phase diagram over these parameters would help elucidate the conditions leading to avalanches and how the cell might modulate their occurrence, e.g., by localizing different myosin isoforms to different regions of the cell. Second, we may ask whether the harmonic approximation to the energy implicit in Hessian analysis is sufficient to describe the energy landscape and how it leads to avalanches. The information on cytoquake dynamics obtained by projecting the network motion onto the Hessian eigenmodes revealed an asymmetry between energy-release events and energy-accumulation events (Fig. 8), and a neural network model detected correlations between the Hessian eigenspectrum and the time-varying likelihood for a cytoquake to occur (SI Appendix, Machine Learning Model). However, as cytoquakes are, by definition, large deformations of the network, we expect that the quadratic approximation will fail to accurately describe the energy landscape around a cytoquake event. Higher-order terms in the energy expansion or recently introduced nonlinear metrics of the local energy landscape, such as the “flatness parameter,” may be used in future computational investigations (53, 72). Third, we may ask about the role of thermal noise in inducing cytoquake events. In this study, thermal noise enters in the stochastic nonequilibrium chemical dynamics, which are simulated by using a variant of the Gillespie algorithm over a reaction–diffusion compartment grid (13). However, the mechanical minimization routine is deterministic given the instantaneous chemical state of the network. Chemical reactions including motor walking and filament polymerization are expected to contribute the dominant structural fluctuations in these far-from-equilibrium networks, but the neglected diffusive motion of the filaments should also help the network escape from metastable configurations and modulate the frequency and scale of avalanches. Elucidating whether cytoquakes can be thermally activated in this way remains another open direction for future work.

Finally, perhaps the most interesting open question regarding cytoquakes pertains to their possible physiological role in cell biology. We proposed here that cytoquakes may be concomitant with a large structural susceptibility, by analogy with well-studied systems like the Ising model that have large susceptibilities to applied fields near their critical point (17, 73). In this argument, the cytoskeleton may undergo large structural changes in response to small changes in the relevant mechanical or chemical signals, an amplification that would serve to enhance cellular sensitivity during dynamic processes, such as chemotaxis. This could also enhance mechanical adaptivity, an increasingly well-documented feature of cytoskeletal networks (19, 74–76). This connection between large cytoskeletal fluctuations and large susceptibility remains speculative at this stage, however, and would benefit from dedicated study. Recent work has suggested that the branching agent Arp2/3, which was not included in the minimal model studied here, can enhance cytoquake sizes (34). One can ask if by tuning the strength of this or other cytoquake-modulating factors, the network is more or less responsive to external perturbation. This perturbation could be introduced either mechanically, for example, through a simulated or real-force microscopy experiment, or chemically, through a variation of the chemical boundary conditions (33). Such studies should clarify whether large events in cytoskeletal dynamics serve a biologically useful purpose.

Materials and Methods

Simulation Setup and Conditions.

To computationally study cytoskeletal networks at high spatiotemporal resolution, we used the simulation platform MEDYAN (13, 20, 31–33). We provide an in-depth discussion of how MEDYAN works in SI Appendix, Description of MEDYAN Simulation Platform. MEDYAN simulations combine stochastic chemical dynamics with a mechanical representation of filaments and associated proteins. Simulations move forward in time by iterating through a cycle of four steps: 1) a short bust of stochastic chemical simulation using a variant of the Gillespie algorithm for a time , 2) computation of the new forces resulting from the reactions in step (1), 3) equilibration of the network via minimization of the mechanical energy, and 4) updating of force-sensitive reaction rates. This protocol reflects an assumed separation of time scales between the slow chemical dynamics and the fast mechanical response, such that the mechanical subsystem is assumed to always remain near equilibrium and to adiabatically follow the chemical changes in the network. As argued in ref. 20, supported using experimental evidence from refs. 22, 77, and 78, this time-scale separation holds for typical cytoskeletal networks that experience localized force deformations with fast relaxation times compared to the typical waiting time between myosin-motor walking steps and filament-growth-induced deformations.

We performed MEDYAN simulations of small cytoskeletal networks consisting of 50 actin filaments in 1- cubic boxes with varying concentrations of -actinin cross-linkers () and of NMIIA minifilaments (). The boundaries of the box exert an exponentially repulsive force against the filaments with a short screening length of 2.7 . Five concentrations of -actinin (ranging from 0.17 to 5.48 ) and five concentrations of myosin miniflaments (ranging from 0.003 to 0.08 ) were used with a constant G-actin monomer concentration of 13.3 , in the regime of physiological concentrations (45). This led to a steady-state filament-length distribution with mean 0.48 and SD 0.26 . We label these conditions , where represents the rank of the cross-linker concentration and represents the rank of the myosin-motor concentration. Five runs of each condition were simulated, each for . The length of the simulation cycle was chosen as for the results presented in this paper, although we explore dependence on this parameter in SI Appendix, Dependence on δt and FT.

Entropy of Spatial Tension Distribution.

The simulation volume of 1 is discretized into cubic voxels, each in linear dimension. Let index these voxels, which are an analysis tool and not related to the reaction–diffusion compartments used in MEDYAN. After each simulation cycle, the mechanical components of the cytoskeletal network (i.e., the filament cylinders, the myosin motors, and the passive cross-linkers) are each under some compressive or tensile force , where indexes the mechanical component. There are other mechanical potentials involving these components, but we focus here only on the tensions . Each mechanical component has a center of mass , and we define the indicator function , which is equal to one if is inside voxel and zero otherwise. The total tension magnitude inside voxel is

| [8] |

The discrete nonnegative scalar field is converted to a distribution by normalization:

| [9] |

Finally, we introduce the discrete Shannon entropy of this distribution at time as

| [10] |

The units of are nats, and large values indicate a uniform spatial distribution of tension magnitudes throughout the network. Reported trends using this metric are found to be essentially independent of the discretization length.

Constructing the Hessian Matrix.

In MEDYAN, semiflexible filaments are represented as a connected sequence of thin cylinders whose joined endpoints (i.e., hinges) are called beads. The set of potentials defining the mechanical energy of the filaments and associated proteins is outlined in SI Appendix, Description of MEDYAN Simulation Platform. The mechanical energy is a function of these beads’ positions, and elements of the Hessian matrix are defined as

| [11] |

where is the Cartesian component of the position of the bead. We have and , where is the number of beads in the network, so is a square symmetric -dimensional matrix. The number of beads will change as filaments (de)polymerize; in these simulations, at QSS, a single filament of length comprises 10 cylinders (11 beads), each in length. After each mechanical minimization, is constructed by numerically computing the derivatives on the right of Eq. 11. The derivative is found by using a second-order central difference approximation by moving the bead in the directions by a small amount and determining the changes in the force component (79). Due to issues of numerical accuracy, we do not assume the symmetry of the matrix , but instead directly compute each component and then symmetrize the result: .

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Qin Ni, Aravind Chandrasekaran, Michelle Girvan, Haoran Ni, Miloš Nikolić, and Hao Wu for helpful discussions and editing of the manuscript. This work was supported by NSF Grants COMBINE 1632976, CHE-1800418, and DMR-1506969. H.L. was supported in part by the NSF Center for Theoretical Biological Physics (Grant PHY-2019745).

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.2110239118/-/DCSupplemental.

Data Availability

Trajectories from numerical simulations have been deposited in the Digital Repository at the University of Maryland (DRUM) (80).

References

- 1.Fletcher D. A., Mullins R. D., Cell mechanics and the cytoskeleton. Nature 463, 485–492 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boal D., Mechanics of the Cell (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, 2012). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mogilner A., Oster G., Cell motility driven by actin polymerization. Biophys. J. 71, 3030–3045 (1996). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mogilner A., On the edge: Modeling protrusion. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 18, 32–39 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang J. H.-C., Thampatty B. P., An introductory review of cell mechanobiology. Biomech. Model. Mechanobiol. 5, 1–16 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McLaughlin R. T., Diehl M. R., Kolomeisky A. B., Collective dynamics of processive cytoskeletal motors. Soft Matter 12, 14–21 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Toyota T., Head D. A., Schmidt C. F., Mizuno D., Non-Gaussian athermal fluctuations in active gels. Soft Matter 7, 3234–3239 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 8.MacKintosh F. C., Levine A. J., Nonequilibrium mechanics and dynamics of motor-activated gels. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 018104 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alencar A. M., et al., Non-equilibrium cytoquake dynamics in cytoskeletal remodeling and stabilization. Soft Matter 12, 8506–8511 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shi Y., Porter C. L., Crocker J. C., Reich D. H., Dissecting fat-tailed fluctuations in the cytoskeleton with active micropost arrays. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 116, 13839–13846 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gutenberg B., Richter C., Seismicity of the Earth and Associated Phenomena (Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ, 1949). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bak P., Christensen K., Danon L., Scanlon T., Unified scaling law for earthquakes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 88, 178501 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Floyd C., Papoian G. A., Jarzynski C., Quantifying dissipation in actomyosin networks. Interface Focus 9, 20180078 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van Hecke M., Jamming of soft particles: Geometry, mechanics, scaling and isostaticity. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 22, 033101 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bouchaud J.-P., Weak ergodicity breaking and aging in disordered systems. J. Phys. I 2, 1705–1713 (1992). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Swartz D. W., Camley B. A., Active gels, heavy tails, and the cytoskeleton. arXiv [Preprint] (2021). https://arxiv.org/abs/2105.02348 (Accessed 14 July 2021). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Zhuravlev P. I., Papoian G. A., Molecular noise of capping protein binding induces macroscopic instability in filopodial dynamics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 11570–11575 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mitchison T., Kirschner M., Dynamic instability of microtubule growth. Nature 312, 237–242 (1984). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mueller J., et al., Load adaptation of lamellipodial actin networks. Cell 171, 188–200.e16 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Popov K., Komianos J., Papoian G. A., MEDYAN: Mechanochemical simulations of contraction and polarity alignment in actomyosin networks. PLoS Comput. Biol. 12, e1004877 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Floyd C., Jarzynski C., Papoian G., Low-dimensional manifold of actin polymerization dynamics. New J. Phys. 19, 125012 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kovács M., Wang F., Hu A., Zhang Y., Sellers J. R., Functional divergence of human cytoplasmic myosin II: Kinetic characterization of the non-muscle IIA isoform. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 38132–38140 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Erdmann T., Albert P. J., Schwarz U. S., Stochastic dynamics of small ensembles of non-processive molecular motors: The parallel cluster model. J. Chem. Phys. 139, 175104 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Howard J., Mechanics of Motor Proteins and the Cytoskeleton (Sinauer Associates, Sunderland, MA, 2001). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Otey C. A., Carpen O., -actinin revisited: A fresh look at an old player. Cell Motil. Cytoskeleton 58, 104–111 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Komianos J. E., Papoian G. A., Stochastic ratcheting on a funneled energy landscape is necessary for highly efficient contractility of actomyosin force dipoles. Phys. Rev. X 8, 021006 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lieleg O., Claessens M. M., Luan Y., Bausch A. R., Transient binding and dissipation in cross-linked actin networks. Phys. Rev. Lett. 101, 108101 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kurzawa L., et al., Dissipation of contractile forces: The missing piece in cell mechanics. Mol. Biol. Cell 28, 1825–1832 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Keller D., Bustamante C., The mechanochemistry of molecular motors. Biophys. J. 78, 541–556 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pereverzev Y. V., Prezhdo O. V., Forero M., Sokurenko E. V., Thomas W. E., The two-pathway model for the catch-slip transition in biological adhesion. Biophys. J. 89, 1446–1454 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chandrasekaran A., Upadhyaya A., Papoian G. A., Remarkable structural transformations of actin bundles are driven by their initial polarity, motor activity, crosslinking, and filament treadmilling. PLoS Comput. Biol. 15, e1007156 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ni Q., Papoian G. A., Turnover versus treadmilling in actin network assembly and remodeling. Cytoskeleton (Hoboken) 76, 562–570 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li X., et al., Tensile force-induced cytoskeletal remodeling: Mechanics before chemistry. PLoS Comput. Biol., 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1007693 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Liman J., et al., The role of the Arp2/3 complex in shaping the dynamics and structures of branched actomyosin networks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 117, 10825–10831 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Floyd C., Papoian G. A., Jarzynski C., Gibbs free energy change of a discrete chemical reaction event. J. Chem. Phys. 152, 084116 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang S., Wolynes P. G., Active contractility in actomyosin networks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 6446–6451 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Prabhakar Murthy D. N., Xie M., Jiang R., Weibull Models (Wiley Series in Probability and Statistics, John Wiley & Sons, New York, NY, 2004), vol. 505. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Malamud B. D., Turcotte D. L., Self-affine time series: I. Generation and analyses. Adv. Geophys. 40, 1–90 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pelletier J. D., Turcotte D. L., Self-affine time series: II. Applications and models. Adv. Geophys. 40, 91–166 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Turcotte D. L., Fractals and Chaos in Geology and Geophysics (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, 1997). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hergarten S., Self Organized Criticality in Earth Systems (Springer, Berlin, Germany, 2002). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Witt A., Malamud B.D., Quantification of long-range persistence in geophysical time series: Conventional and benchmark-based improvement techniques. Surv. Geophys. 34, 541–651 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Williams Z. C., Pelletier J. D., Meixner T., Self-affine fractal spatial and temporal variability of the San Pedro River, southern Arizona. J. Geophys. Res. Earth Surf. 124, 1540–1558 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hogg R. V., McKean J., Craig A. T., Introduction to Mathematical Statistics (Pearson Education, Boston, MA, 2005). [Google Scholar]

- 45.Milo R., Phillips R., Cell Biology by the Numbers (Garland Science, New York, NY, 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pun C.-K., Matin S., Klein W., Gould H., Prediction in a driven-dissipative system displaying a continuous phase transition using machine learning. Phys. Rev. E 101, 022102 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Linsmeier I., et al., Disordered actomyosin networks are sufficient to produce cooperative and telescopic contractility. Nat. Commun. 7, 12615 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schlick T., Molecular Modeling and Simulation: An Interdisciplinary Guide (Interdisciplinary Applied Mathematics, Springer Science & Business Media, New York, NY, 2010), vol. 21. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Leach A. R., Molecular Modelling: Principles and Applications (Pearson Education, Boston, MA, 2001). [Google Scholar]

- 50.Huisman E. M., Lubensky T. C., Internal stresses, normal modes, and nonaffinity in three-dimensional biopolymer networks. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 088301 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cho M., Fleming G.R., Saito S., Ohmine I., Stratt R. M., Instantaneous normal mode analysis of liquid water. J. Chem. Phys. 100, 6672–6683 (1994). [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bembenek S. D., Laird B. B., Instantaneous normal modes and the glass transition. Phys. Rev. Lett. 74, 936–939 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Richard D., Kapteijns G., Giannini J. A., Manning M. L., Lerner E., Simple and broadly applicable definition of shear transformation zones. Phys. Rev. Lett. 126, 015501 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.DeVries P. M. R., Viégas F., Wattenberg M., Meade B. J., Deep learning of aftershock patterns following large earthquakes. Nature 560, 632–634 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mignan A., Broccardo M., One neuron versus deep learning in aftershock prediction. Nature 574, E1–E3 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dauphin Y. N., et al., “Identifying and attacking the saddle point problem in high-dimensional non-convex optimization” in NIPS’14: Proceedings of the 27th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Z. Ghahramani, M. Welling, C. Cortes, N. D. Lawrence, K. Q. Weinberger, Eds. (MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, 2014), pp. 2933–2941.

- 57.Wang S., Wolynes P. G., Microscopic theory of the glassy dynamics of passive and active network materials. J. Chem. Phys. 138, A521 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Shen T., Wolynes P. G., Stability and dynamics of crystals and glasses of motorized particles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 8547–8550 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Newman M., Networks (Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK, 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 60.Alvarado J., Sheinman M., Sharma A., MacKintosh F. C., Koenderink G. H., Force percolation of contractile active gels. Soft Matter 13, 5624–5644 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Alvarado J., Sheinman M., Sharma A., MacKintosh F. C., Koenderink G. H., Molecular motors robustly drive active gels to a critically connected state. Nat. Phys. 9, 591–597 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 62.Silbert L. E., Liu A. J., Nagel S. R., Normal modes in model jammed systems in three dimensions. Phys. Rev. E Stat. Nonlin. Soft Matter Phys. 79, 021308 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zeravcic Z., van Saarloos W., Nelson D.R., Localization behavior of vibrational modes in granular packings. Europhys. Lett. 83, 44001 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wang S., Wolynes P. G., Communication: Effective temperature and glassy dynamics of active matter. J. Chem. Phys. 135, 051101 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bak P., Tang C., Wiesenfeld K., Self-organized criticality: An explanation of the 1/f noise. Phys. Rev. Lett. 59, 381–384 (1987). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bak P., Tang C., Earthquakes as a self-organized critical phenomenon. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 94, 15635–15637 (1989). [Google Scholar]

- 67.Jensen H. J., Self-Organized Criticality: Emergent Complex Behavior in Physical and Biological Systems (Cambridge Lecture Notes in Physics, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, 1998), vol. 10. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Seara D. S., et al., Entropy production rate is maximized in non-contractile actomyosin. Nat. Commun. 9, 4948 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cardamone L., Laio A., Torre V., Shahapure R., DeSimone A., Cytoskeletal actin networks in motile cells are critically self-organized systems synchronized by mechanical interactions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 13978–13983 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bonilla-Quintana M., Wörgötter F., D’Este E., Tetzlaff C., Fauth M., Reproducing asymmetrical spine shape fluctuations in a model of actin dynamics predicts self-organized criticality. Sci. Rep. 11, 4012 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Matin S., Pun C.-K., Gould H., Klein W., Effective ergodicity breaking phase transition in a driven-dissipative system. Phys. Rev. E 101, 022103 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Feng Y., Tu Y., The inverse variance-flatness relation in stochastic gradient descent is critical for finding flat minima. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 118, e2015617118 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Binney J. J., Dowrick N. J., Fisher A. J., Newman M. E. J..The Theory of Critical Phenomena: An Introduction to the Renormalization Group (Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK, 1992). [Google Scholar]

- 74.Banerjee S., Gardel M. L., Schwarz U. S., The actin cytoskeleton as an active adaptive material. Annu. Rev. Condens. Matter Phys. 11, 421–439 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Stern M., Pinson M. B., Murugan A., Continual learning of multiple memories in mechanical networks. Phys. Rev. X 10, 031044 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 76.Tabatabai A. P., et al., Detailed balance broken by catch bond kinetics enables mechanical-adaptation in active materials. Adv. Funct. Mater. 31, 2006745 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Falzone T. T., Blair S., Robertson-Anderson R. M., Entangled F-actin displays a unique crossover to microscale nonlinearity dominated by entanglement segment dynamics. Soft Matter 11, 4418–4423 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Fujiwara I., Vavylonis D., Pollard T. D., Polymerization kinetics of ADP- and ADP-Pi-actin determined by fluorescence microscopy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 8827–8832 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Brooks B.R., Janežič D., Karplus M., Harmonic analysis of large systems. I. Methodology. J. Comput. Chem. 16, 1522–1542 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- 80.Floyd C., Levine H., Jarzynski C., Papoian G. A., “Data for: Understanding cytoskeletal avalanches using mechanical stability analysis.” DRUM. 10.13016/s8yq-dary. Deposited 19 August 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Trajectories from numerical simulations have been deposited in the Digital Repository at the University of Maryland (DRUM) (80).