Abstract

Purpose:

Cytochrome P450 2D6 (CYP2D6) genotype-guided opioid prescribing is limited. The purpose of this type 2 hybrid implementation-effectiveness trial was to evaluate the feasibility of clinically implementing CYP2D6-guided post-surgical pain management and determine that such an approach did not worsen pain control.

Methods:

Adults undergoing total joint arthroplasty were randomized 2:1 to genotype-guided or usual pain management. For participants in the genotype-guided arm with a CYP2D6 poor (PM), intermediate (IM), or ultra-rapid metabolizer (UM) phenotype, recommendations were to avoid hydrocodone, tramadol, codeine, and oxycodone. The primary endpoints were feasibility metrics and opioid use; pain intensity was a secondary endpoint. Effectiveness outcomes were collected 2-weeks post-surgery.

Results:

Of 282 patients approached, 260 (92%) agreed to participate. In the genotype-guided arm, 20% had a high-risk (IM/PM/UM) phenotype, of whom 72% received an alternative opioid versus 0% of usual care participants (p<0.001). In an exploratory analysis, there was less opioid consumption (200 [104-280] vs. 230 [133-350] morphine milligram equivalents; p=0.047) and similar pain intensity (2.6 ± 0.8 vs. 2.5 ± 0.7; p=0.638) in the genotype-guided vs. usual care arm, respectively.

Conclusion:

Implementing CYP2D6 to guide post-operative pain management is feasible and may lead to lower opioid use without compromising pain control.

INTRODUCTION

More Americans suffer from pain than are affected by heart disease, cancer, and lung disease combined.1 Opioids are commonly used to treat pain and are among the most widely prescribed medications in the United States.2 Given the role of opioids in acute, postoperative pain management, it is no surprise that approximately 35% of all opioid prescriptions originate from surgeons.3 However, interindividual variability in analgesic response to opioids has been observed, which may compromise post-operative pain control.4–7 Considering factors underlying this variability in opioid response may allow surgeons to individualize treatments and optimize opioid prescribing.

Hydrocodone, tramadol, codeine, and oxycodone are among the most prescribed opioids, and the cytochrome P450 enzyme 2D6 (CYP2D6) is central to generation of highly potent metabolites for these opioids.8 Codeine and tramadol are dependent on bioactivation by the CYP2D6 enzyme to morphine and O-desmethyltramadol, respectively, which have 200-fold greater affinity for the μ-opioid receptor than their parent compounds.9,10 Tramadol also has non-opioid mechanisms of action, via reuptake inhibition of serotonin and norepinephrine, which does not require bioactivation, thus providing some non-opioid analgesic activity with the parent compound.11 Hydrocodone and oxycodone undergo similar metabolism via CYP2D6 to hydromorphone and oxymorphone, respectively, which have 10- to 40-fold higher receptor affinity than the parent compound.9,10,12

The CYP2D6 gene is highly polymorphic, with over 130 alleles defined (https://www.pharmvar.org/gene/CYP2D6). CYP2D6 variation affects opioid metabolism and contributes to the interindividual variability in opioid response.9 Clinically, CYP2D6 genotype is used to predict CYP2D6 enzyme activity. Approximately 5-10% of individuals are poor metabolizers (PMs), with no enzyme activity, and another 2-11% are intermediate metabolizers (IMs), with significantly reduced enzyme activity.9 Patients with a CYP2D6 PM or IM phenotype have a reduced capacity to biotransform codeine and tramadol to their active metabolites.9 Clinically, this may result in insufficient analgesia, and data suggest these drugs should be avoided in PMs and potentially in IMs.9,13 At the opposite extreme, approximately 1-2% of individuals are ultra-rapid metabolizers (UMs) secondary to CYP2D6 copy number variation. Patients with the UM phenotype are at increased risk for toxic concentrations of active opioid metabolites, with reports of life-threatening toxicity and death with codeine or tramadol.14–16 The data are less clear with hydrocodone and oxycodone. However, evidence that the effectiveness of hydrocodone is reduced with concomitant use of CYP2D6 inhibitors suggests that CYP2D6 genotype has implications for response to hydrocodone as well.17,18

Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) Guidelines support CYP2D6 genotype-guided use of opioid analgesics,9 but this is rarely done in clinical practice. Given frequent post-operative opioid use and the role of CYP2D6 in opioid metabolism and response, this pharmacogene is uniquely poised to facilitate opioid prescribing decisions and individualize post-operative pain management. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to evaluate the feasibility of implementing a CYP2D6-guided post-surgical pain management paradigm and determine that such an approach did not worsen post-operative pain control. We specifically hypothesized that CYP2D6-guided management of post-surgical pain is feasible, with reduced use of codeine, tramadol, hydrocodone, and oxycodone in PMs/IMs/UMs. Additionally, we hypothesized that a CYP2D6-guided approach would not worsen pain control compared with an unguided approach.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design

This study was a randomized, open label, type 2 hybrid implementation-effectiveness trial19 with the co-primary endpoints of feasibility of clinical implementation and opioid utilization. The study was conducted in 260 adult participants undergoing unilateral total joint arthroplasty, funded under a University of Florida (UF) Health-Clinical and Translational Science Institute Learning Health System Initiative, with additional support from UF Health Shands hospital. According to the PRagmatic-Explanatory Continuum Indicator Summary (PRECIS)-2 tool, this trial was highly pragmatic as opposed to explanatory in six of nine domains assessed (Supplementary Table 1).20 Participants were enrolled between June 2018 and June 2019. This study initially recruited participants from a single UF orthopaedic clinic and later expanded to include a second UF orthopaedic clinic site. Five orthopaedic physicians were involved in this study and referred patients for study participation.

Study participants

Eligible participants were adults ≥18 years of age scheduled for primary unilateral total hip or knee arthroplasty. Those scheduled to undergo a revision or bilateral procedure; with planned discharge to a rehabilitation facility; receiving long-term opioid therapy, defined as use of opioids on most days for more than three months; or with an allergy to opioids were excluded.

Randomization and baseline procedures

Prior to surgery, patients typically had two orthopaedic clinic visits. The first was an initial evaluation visit when the decision for surgery was made. The second was a pre-operative visit that occurred within one month of surgery, during which the post-operative pain management plan was developed, and a prescription for post-operative opioid therapy was provided. Clinical research coordinators approached patients about study participation at the initial evaluation visit after the decision for surgery was made. After providing written informed consent, a buccal sample and data on participant demographics and medical history were collected, and participants were randomized 2:1 to a CYP2D6-guided or usual post-operative pain management approach. Simple random allocation with block sizes of 6 or 12 was performed within each site. For participants in the CYP2D6-guided arm, buccal samples were batched each week and processed in the College of American Pathologists/Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments-licensed UF Health Pathology Laboratory, and CYP2D6 genotype and metabolizer phenotype results were reported to the electronic health record (EHR). This process allowed genotype results to be available in time to inform the post-operative pain management plan. Participants randomized to the usual care pain management arm had their DNA sample stored in the pathology laboratory until they completed their study participation, at which time, the sample was processed, and CYP2D6 genotype and metabolizer phenotype were reported in the EHR for future use. Samples were not genotyped for participants in the usual care arm who did not complete study procedures.

CYP2D6 genotyping, phenotype assignment, and recommendations

CYP2D6 genotype was determined for all but four participants using a Luminex xTAG CYP2D6 Kit v3 (Luminex Corporation, Austin, TX, USA). In early June 2019, the pathology laboratory transitioned genotyping to the QuantStudio 12K Flex Real-Time PCR System (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), which was used to genotype the final four participants. Both platforms tested for the CYP2D6 *2, *3, *4, *5, *6, *7, *8, *9, *10, *17, *29, and *41 alleles and copy number variation. The Luminex kit additionally tested for the *11, *15, and *35 alleles. The activity score (AS) method was used to assign CYP2D6 metabolizer phenotype based on genotype and concomitant use of strong or moderate CYP2D6 inhibitors. First, an AS was assigned for each allele based on CPIC guidance at the time of study enrollment.9 An activity value of 1 was assigned for each normal function allele (i.e., *1, *2, *35), 0.5 for each decreased function allele (i.e., *9, *10, *17, *29, *41), and 0 for each no function allele (i.e., *3-*8).9,21,22 The allele activity scores were summed to derive the total AS for the diplotype. Then, the total AS was multiplied by a factor of 0.5 for individuals taking a moderate inhibitor (i.e. duloxetine) or 0 for individual taking a strong CYP2D6 inhibitor (i.e. bupropion, fluoxetine, paroxetine) to derive the clinical CYP2D6 activity score.9,21,23,24 Phenotypes were then assigned based on the clinical CYP2D6 activity score that accounted for CYP2D6 genotype and phenoconversion: 0, PM; >0-0.75, IM; 1-2, normal metabolizer (NM); and >2, UM. The genotyping assay could detect the presence of allele duplication, but could not determine which allele was duplicated or the number of allele copies, and thus, ranged phenotypes were possible (e.g., NM to UM).

After return of CYP2D6 genotype, a clinical pharmacist provided a standardized consult note in the EHR, as has been described25, to communicate prescribing recommendations based on CYP2D6 phenotype. For participants in the genotype-guided arm with a CYP2D6 PM, IM, or UM clinical phenotype (high risk phenotype), recommendations were to avoid tramadol, hydrocodone, codeine, and oxycodone and to use an alternative opioid (e.g. morphine, hydromorphone) or non-opioid (e.g. NSAID) analgesic. Tramadol was recommended as the preferred opioid in NMs because of its opioid and non-opioid mechanisms and purported lower risk for misuse.26,27 Given the risks for toxicity in UMs, participants with the NM to UM ranged phenotype were treated as UM in regards to opioid recommendations.

Study surveys

At 1-week post-surgery, participants in both arms completed the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) pain intensity survey. At 2 weeks (± 4 days) post-surgery, participants in both arms were asked to complete the PROMIS 43 and pain intensity surveys (www.nihpromis.org) and the Hip Disability and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score Short Form (HOOS-JR) or Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score Short Form (KOOS-JR) based on surgery indication (e.g., total hip arthroplasty [THA] vs. total knee arthroplasty [TKA]). At both post-operative follow-up time points, participants were also asked about their consumption of any opioid prescribed since discharge home from surgery. Pain intensity surveys were utilized to determine composite pain intensity, defined as the mean of current pain and worst and average pain over the past seven days.13 Participants rated their pain intensity for each of the three questions on a 5-point Likert scale: “Had no pain” = 1, “Mild” = 2, “Moderate” = 3, “Severe” = 4, and “Very severe” = 5. The PROMIS 43 survey assessed the domains of physical functioning, anxiety, depression, fatigue, sleep disturbance, ability to participate in social activities, pain interference, prescription pain medication misuse, and average pain intensity.28 The HOOS-JR and KOOS-JR surveys assessed the participant’s ability to complete usual activities and are part of the standard clinical post-operative follow-up assessment. Opioid consumption was evaluated by asking participants to report the strength and quantity of the prescribed opioid and the number of pills remaining in the bottle (Supplementary Figure 1). A series of questions was also posed regarding medication refills to capture opioid use beyond what was prescribed at the pre-operative appointment. If the participant had a follow-up clinic visit at the two-week time point, surveys and assessment of opioid consumption were completed in person with the study coordinator. Otherwise, based on participant preference, surveys and assessment of opioid consumption were completed by email, via a link provided in a text message, or by phone call with a pharmacist or pharmacy technician from the UF Center for Quality Medication Management.

Data analysis

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation, median [interquartile range], or count (%). The primary outcomes were feasibility of implementing a genotype-guided opioid prescribing approach for participants undergoing an elective surgical procedure and opioid utilization. The following implementation metrics were assessed: percentage of patients who agreed to participate, percentage of participants in both arms with a clinical phenotype (based on CYP2D6 and phenoconversion) warranting alternative therapy, percentage of participants in the genotype-guided arm for whom a clinical phenotype-guided recommendation was accepted by the clinician, and specific opioids prescribed by CYP2D6 phenotype.

Consult recommendations were considered accepted for participants with a high-risk phenotype if an alternative opioid (e.g., hydromorphone, morphine) was prescribed. For CYP2D6 NMs, consult recommendations were accepted if tramadol was prescribed. Participants whose genotype resulted after the pre-operative appointment were excluded from the analysis of acceptance of consult recommendations.

Opioid consumption was calculated as the differences between participant reported opioid pills prescribed at the pre-operative appointment and opioid pills remaining at the1-week and 2-week follow-up time-points. This difference was calculated for each opioid and then expressed as morphine milligram equivalents (MME) using standard conversion factors and the medication strength of the prescribed opioid analgesic.29 If a participant was prescribed multiple opioids, MMEs were calculated for each opioid and then summed to give a total MME value.

Secondary outcomes included composite pain intensity, PROMIS-43 measures, and mobility as assessed by the HOOS-JR or KOOS-JR survey. Data on pain intensity were collected to document that there were not obvious trends of the CYP2D6-guided approach leading to worse pain control, which in turn could lead to worse post-surgical outcomes. While composite pain intensity and opioid consumption were collected at both 1-week and 2-weeks post-surgery, the 2-week time-point was designated as the primary time-point for data on pain control.

Study participant characteristics, composite pain intensity, and other survey results were compared between the CYP2D6-guided and usual care arms by chi-squared, Fisher’s exact, or two independent samples t-test where appropriate. Opioid consumption data were not normally distributed and were compared between study arms using the Mann-Whitney U test. Main analyses were conducted in all participants in each study arm, with subset analyses conducted in IM/PMs and separately in NMs. Comparisons between the CYP2D6-guided and usual care groups for opioid consumption and composite pain intensity were also performed by analysis of covariance, adjusting for baseline differences between groups. Data analyses were performed using Python.30

This study was originally funded as a pilot project within our NIH-funded Learning Health System, with planned enrollment of 130 participants. In an a priori power calculation assuming 25% of participants in the CYP2D6-guided arm would have a PM, IM, or UM phenotype (based on genotype and drug interactions) and that codeine, tramadol, hydrocodone, and oxycodone would be avoided in these participants, whereas the remaining 75% of participants in the implementation arm would be prescribed tramadol and nearly all (i.e. 95%) of controls would be prescribed tramadol, codeine, hydrocodone, or oxycodone, including 130 patients was estimated to have >80% power, with an alpha of 0.05, to detect a difference in use of codeine, tramadol, hydrocodone, or oxycodone between arms. After the trial started, we received additional funding from our health system, which enabled expansion of our sample size to 260 participants. A post-hoc power calculation based on the number of patients who completed the assessment of opioid consumption showed that including 126 participants in the CYP2D6-guided arm and 68 participants in the usual care arm, with an alpha of 0.05, provided 80% power to detect an effect size of 0.43 which is equivalent to a difference of 60 MME between arms.

RESULTS

Participant population

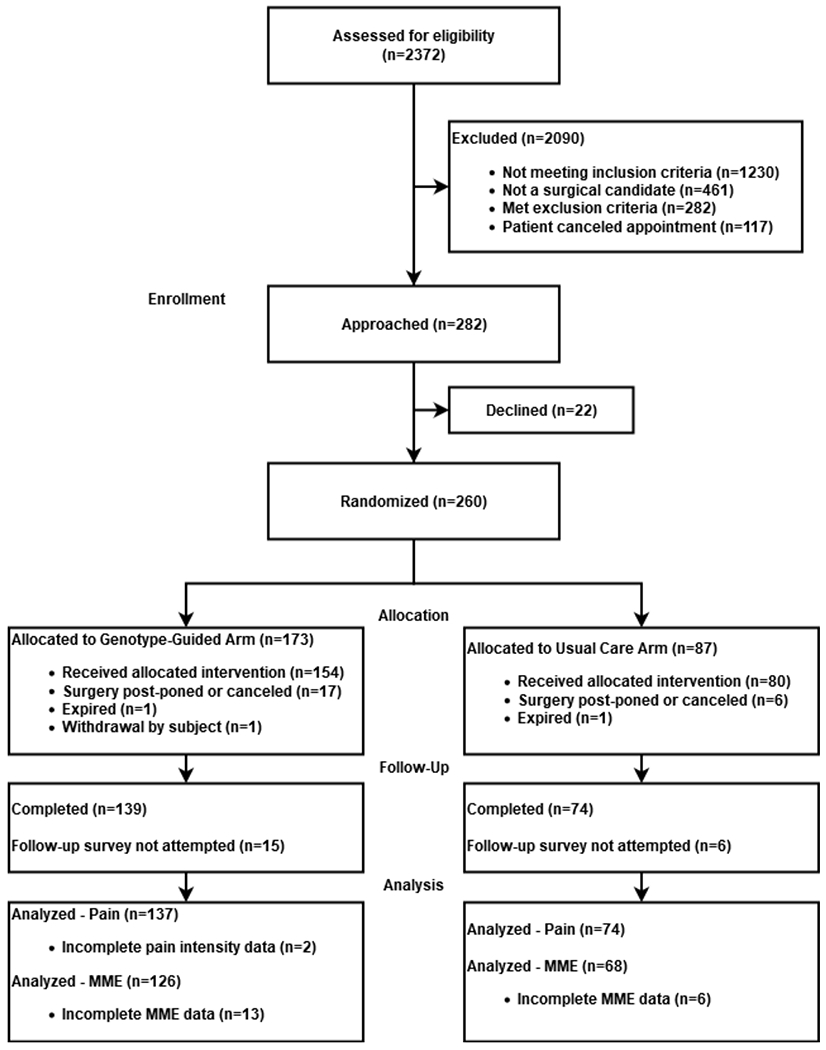

Of 282 participants approached about study participation, 260 (92%) agreed to participate and were randomized to the genotype-guided (n=173) or usual care (n=87) arm (Figure 1). Prevailing reasons why patients declined participation included being uncomfortable with research (n=5) or genotyping (n=3), unwilling to take an opioid analgesic (n=3) or complete follow-up surveys (n=2), and content with post-operative analgesics used with prior surgery (n=1). The remaining declinations were for other, unknown, or logistical reasons (n=8). Of those who agreed to participate, total joint arthroplasty was performed in 90% (234/260) of participants, including 154 in the genotype-guided arm and 80 in the usual care arm. Study participant demographics and clinical variables for these 234 participants are summarized in Table 1. Clinical CYP2D6 phenotype and body mass index (BMI) varied between treatment arms. The CYP2D6 NM phenotype occurred less frequently in the usual care arm (56%) compared with the genotype-guided arm (77%; p=0.017). Otherwise, participant characteristics were well balanced between the CYP2D6-guided and usual care arms.

Figure 1.

CONSORT Flow Diagram

Table 1.

Study Participant Characteristics by Allocated Treatment Group

| Characteristic | Participants, No. (%) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CYP2D6-guided (n = 154) | Usual Care (n = 80) | ||

| Type of Surgery | |||

| THA | 67 (44) | 30 (38) | 0.376 |

| TKA | 87 (56) | 50 (62) | |

| Age, years | 68 [62-74] | 65 [57-72] | 0.075 |

| Female | 91 (59) | 46 (58) | 0.925 |

| Race | |||

| White | 131 (85) | 65 (81) | 0.529 |

| Black | 16 (10) | 12 (15) | |

| Asian | 3 (2) | 1 (1) | |

| Other | 4 (3) | 2 (3) | |

| BMI, kg/m 2 | 29 [27-35] | 32 [28-38] | 0.039 |

| Past medical history | |||

| Osteoarthritis | 145 (94) | 74 (93) | 0.834 |

| Diabetes | 29 (19) | 18 (23) | 0.622 |

| Hypertension | 47 (59) | 94 (61) | 0.843 |

| Depression | 33 (21) | 14 (18) | 0.590 |

| Anxiety | 33 (21) | 17 (21) | 0.999 |

| Psychiatric disorder | 8 (5) | 3 (4) | 0.753 |

| Clinical CYP2D6 Phenotype a | |||

| PM | 23 (15) | 16 (20) | 0.012c |

| IM | 9 (6) | 9 (11) | |

| NM | 119 (77) | 45 (56) | |

| UM | 2 (1) | 0 | |

| NM-UM | 0 | 3 (4) | |

| IM-UMb | 1 (<1) | 0 | |

| Indeterminate | 0 | 1 (1) | |

| Not performed | 0 | 6 (8) | |

| Pre-operative composite pain intensity | 3.2 ± 0.7 | 3.2 ± 0.7 | 0.595 |

| Length of hospital stay, days | 1 [1-2] | 1 [1-2] | 0.678 |

Data are presented as n (%), mean ± SD, or median [interquartile range]. BMI: body mass index, IM: intermediate metabolizer, NM: normal metabolizer, PM: poor metabolizer, THA: total hip arthroplasty, TKA: total knee arthroplasty, UM: ultrarapid metabolizer.

Clinical CYP2D6 phenotype accounts for CYP2D6 genotype and phenoconversion with moderate and strong CYP2D6 inhibitors.

IM-UM ranged phenotype reported as “indeterminate” within the electronic health record.

p value for comparison of PM, IM, NM, UM, and NM-UM phenotypes between the CYP2D6-guided and usual care arms.

Feasibility and Implementation Metrics

Clinical CYP2D6 genotyping was successful from the initial buccal swab in >99% (227/228) of participants in both study arms. The only indeterminate genotype result occurred in a usual care participant who was unable to be re-contacted to obtain a second sample for repeat genotyping. CYP2D6 phenotype frequencies based on genotype alone and with consideration of phenoconversion are listed in Table 2. Based on CYP2D6 genotype, 6% of participants were PMs, 7% were IMs, and 16% (36/228) had a high-risk CYP2D6 phenotype that warranted a peri-operative opioid other than codeine, tramadol, hydrocodone, or oxycodone. Once phenoconversion was considered in the overall study population, there was a 2.8-fold increase in the prevalence of the PM phenotype and the proportion of participants with a high-risk CYP2D6 phenotype increased to 27% (62/228). Of those who underwent surgery within the CYP2D6-guided arm, 94% (145/154) had genotype results returned prior to the pre-operative appointment when the opioid prescription was provided, with a median genotype turnaround time of 8 (range: 2 - 23) days.

Table 2.

CYP2D6 Phenotype Frequencies Among Participants Who Underwent Total Joint Arthroplasty

| CYP2D6 Phenotype | Participants, No. (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| CYP2D6 Genotype | CYP2D6 genotype + phenoconversiona | |

| PM | 14 (6) | 39 (17) |

| IM | 17 (7) | 18 (8) |

| NM | 190 (83) | 164 (72) |

| UM | 2 (<1) | 2 (<1) |

| NM-UM | 3 (1) | 3 (1) |

| IM-UM | 1 (<1) | 1 (<1) |

| Indeterminate | 1 (<1) | 1 (<1) |

IM: intermediate metabolizer, NM: normal metabolizer, PM: poor metabolizer, UM: ultrarapid metabolizer.

Phenoconversion with moderate or strong CYP2D6 inhibitor.

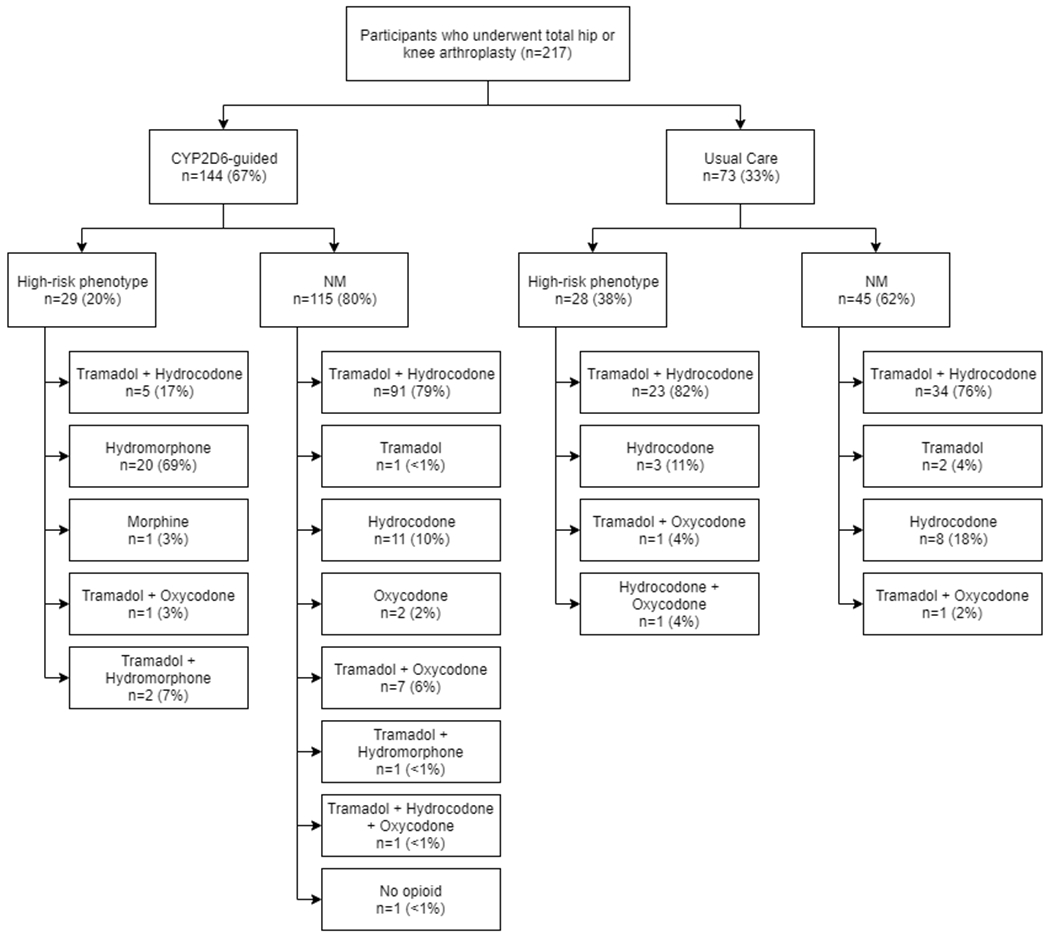

In the CYP2D6-guided arm, 20% (29/145) of those with genotype returned prior to the pre-op appointment had a high-risk (IM/PM/UM/NM-UM) CYP2D6 phenotype, of whom 72% (21/29) received an opioid other than codeine, tramadol, hydrocodone, or oxycodone. Hydromorphone was the most commonly prescribed alternative opioid in those with a high-risk phenotype (20/21; 95%, Figure 2). None of the usual care participants with a high-risk phenotype received an alternative opioid (Figure 2. p<0.001 for comparison with the genotype-guided arm). Among those with a NM phenotype, 88% (101/115) of CYP2D6-guided and 82% (37/45) of usual care participants were prescribed a tramadol-based regimen (p=0.355). In most cases (87% of those in genotype-guided arm and 78% in usual care arm) hydrocodone, or another opioid, was prescribed concomitantly with tramadol as is usual practice at the clinics where participants were enrolled. Tramadol was prescribed as the sole opioid to 1% of NMs in the genotype-guided arm and 4% of NMs in the usual care arm.

Figure 2.

Implementation Outcomes: Opioid Use Among Study Participants Stratified by Treatment Assignment and CYP2D6 Phenotype

High-risk phenotype defined as CYP2D6 IM (intermediate metabolizer), PM (poor metabolizer), UM (ultrarapid metabolizer), or NM-UM (range from NM to UM).

Opioid Consumption and Pain Intensity

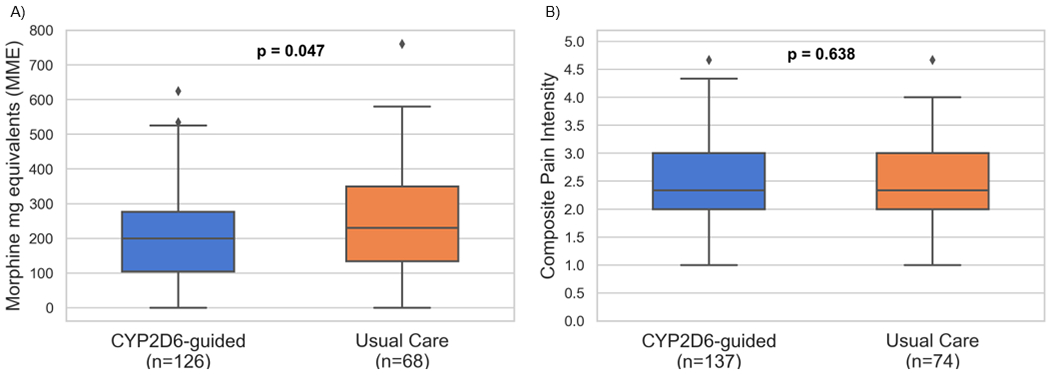

MME data were provided by 72% (111/154) and 82% (126/154) of CYP2D6-guided and 71% (57/80) and 85% (68/80) of usual care participants at the 1- and 2-weeks post-operative timepoints. One- and two-week post-operative pain intensity surveys were completed by 86% (133/154) and 89% (137/154) of CYP2D6-guided and 84% (67/80) and 93% (74/80) of usual care participants, respectively. In the trial population overall at 2-weeks post-surgery, opioid consumption was lower in the CYP2D6-guided group (200 mg [104 mg – 280 mg]) compared with the usual care group (230 mg [133 mg – 350 mg]; p=0.047; Figure 3a). However, composite pain intensity was similar between CYP2D6-guided (2.6 ± 0.8) and usual care (2.5 ± 0.7) arms (p=0.638; Figure 3b); most reported a mild to moderate level of pain intensity. Adjusting for BMI and clinical CYP2D6 phenotype did not influence results for pain intensity (p=0.640) or MME consumption (p=0.029). None of the participants with the UM phenotype completed study follow-up, and all participants with the NM-UM ranged phenotype were in the usual care arm. Subset analyses were conducted in those with the IM/PM and NM phenotypes. Within these subsets, MME use and pain intensity did not differ significantly between study arms (Supplementary Table 2). There were similar trends in the opioid consumption and composite pain intensity data at the 1-week post-surgery time point (Supplementary Table 3).

Figure 3.

Effectiveness Outcomes: Opioid Consumption and Composite Pain Intensity at 2-weeks Post-op by Study Arm

(a) Opioid consumption and (b) composite pain intensity. Boxes represent the median values and upper and lower quartiles. Whiskers extend to show the rest of the distribution, except for outliers which are represented by diamonds.

Two-week post-operative opioid consumption and pain intensity were greater following TKA, compared with THA in both the genotype-guided and usual care arms (Table 3). Opioid consumption did not differ between CYP2D6-guided and usual care arms for participants undergoing THA (p=0.865). However, among TKA recipients, opioid consumption was lower in the CYP2D6-guided versus usual care arm (Table 3; p=0.003). Composite pain intensity was similar between CYP2D6-guided and usual care arms when stratified by surgery indication (Table 3).

Table 3.

Clinical Effectiveness Outcomes at 2-weeks Post-arthroplasty Stratified by Surgery Indication

| CYP2D6-guided | Usual Care | P values | |

|---|---|---|---|

| MME Consumption | |||

| THA | 150 mg [68-255] (n=51) | 133 mg [45-230] (n=26) | 0.865 |

| TKA | 216 mg [125-325] (n=75) | 308 mg [193-413] (n=42) | 0.003 |

| p-value for THA vs. TKA | 0.036 | <0.001 | |

| Composite Pain Intensity | |||

| THA | 2.3 ± 0.7 (n=55) | 2.3 ± 0.6 (n=28) | 0.973 |

| TKA | 2.8 ± 0.8 (n=82) | 2.7 ± 0.8 (n=46) | 0.506 |

| p-value for THA vs. TKA | <0.001 | 0.031 |

MME: morphine milligram equivalents; THA: total hip arthroplasty; TKA: total knee arthroplasty. PROMIS Composite Pain Intensity and opioid consumption; values displayed as median [IQR] or mean ± SD.

Other PROMIS measures and KOOS-JR/HOOS-JR interval scores were similar between CYP2D6-guided and usual care arms when considering all patients in the study arm and when limiting to PM/IMs and NMs (Supplementary Tables 4 and 5. Opioid-related adverse events were not systematically collected as part of the study. However, none of the participants required naloxone in the post-operative period, or throughout their hospitalization.

DISCUSSION

Data from the current investigation demonstrate the feasibility of implementing CYP2D6 genotyping to guide post-operative pain management, with most participants agreeing to testing and high provider acceptance of genotype-guided recommendations in those with a high-risk phenotype. Further, our data suggest a genotype-guided approach may lead to lower opioid use without compromising pain control. Similarities in composite pain intensity and HOOS/KOOS-JR interval scores between study arms suggests participants consumed opioids as needed to minimize post-operative pain, but those in the genotype-guided arm needed less opioids for similar pain control.

Results when stratified by surgery type imply that the impact of a genotype-guided approach on opioid consumption may be greatest in those undergoing more painful surgical procedures. Participants who underwent TKA had greater composite pain intensity scores and consumed more post-operative opioids than their THA counterparts, regardless of the post-operative pain management approach. The CYP2D6-guided approach was associated with decreased opioid consumption after TKA, but not THA, suggesting that overall results were driven by participants undergoing TKA.

While not directly assessing the opioid epidemic, our results may have implications in this regard in that the majority of individuals who misuse opioids report the pursuit of pain relief as a primary motivator.31 Similar pain intensity with less opioid consumption in the CYP2D6-guided arm indicates that this guided approach leads to better pain control,32 and as such, may potentially avert future opioid misuse. Indeed, post-operative opioid use is proposed to be a gateway to chronic opioid use, with evidence of new persistent opioid use three to six months after a surgical procedure in approximately 6% of individuals who were opioid naïve prior to surgery.33 Physicians in certain specialties, like orthopaedic surgery, prescribe opioids at a higher rate than those of other specialties and primary care physicians.3,34 Opioid sparing measures for post-operative analgesia have thus become a priority for surgeons to expedite patient recovery and combat the opioid epidemic,33,35 and patients undergoing orthopaedic surgery may especially benefit from measures, such as CYP2D6-genotyping, to guide opioid prescribing. Patients have also expressed a desire for more individualized information regarding pain management after hip and knee arthroplasty.36 Indeed, over 90% of patients approached about the current study agreed to participate. The elective surgical setting further lends itself well to a genotype-guided opioid approach. Even with a median genotype turnaround time of 8 days, 95% of genotypes resulted prior to the pre-operative visit, demonstrating that a major logistical barrier to pharmacogenetic implementation, that is genotype turnaround time, can be largely overcome in the elective surgery setting. While this study primarily focused on utilizing CYP2D6 genotype to guide post-operative opioid prescribing, studies evaluating perioperative pharmacogenomic implementations are underway.37,38

Multiple studies have evaluated post-operative opioid effectiveness according to CYP2D6 genotype. In line with our findings, a longitudinal cohort study of patients undergoing abdominal or thoracic surgeries showed similar post-operative pain scores after tramadol administration across CYP2D6 phenotypes; however, opioid consumption was not assessed.39 Other studies evaluating tramadol effectiveness in relieving post-operative pain included both pain intensity and tramadol consumption as outcomes measures. Among patients undergoing elective nephrectomy or major abdominal surgery, increased pain intensity, despite higher opioid consumption, was observed in those with CYP2D6 nonfunctional or reduced function genotypes versus NMs.40,41 A study of patients undergoing knee arthroscopy showed that pain intensity, but not tramadol consumption, varied by CYP2D6 phenotype in the immediate post-operative period.42 The totality of these data, in addition to findings from the current study, support the importance of assessing both opioid consumption and pain intensity when evaluating post-surgical pain management approaches.

The current study also highlights the importance and prevalence of phenoconversion (i.e., use of moderate and strong CYP2D6 inhibitors) in clinical phenotype determination among patients undergoing total joint arthroplasty. After considering phenoconversion in this cohort of participants, the prevalence of high-risk CYP2D6 phenotypes increased from 16% to 27%. More specifically, the prevalent use of strong CYP2D6 inhibitors resulted in the PM phenotype nearly tripling. These results suggest future pain-related pharmacogenomics research should screen for the concomitant use of moderate and strong CYP2D6 inhibitors.

This study has limitations that deserve consideration. First, assessment of MME may be considered exploratory in that it was not the focus of our a priori power calculation. In addition, reliance on participant reported opioid consumption restricts MME analysis to those who successfully completed the two-week survey. Given this was a pragmatic study, participants could have received any number of analgesics at various doses. Therefore, reliance on participant responses was key to calculating MME at the follow-up time points, and incomplete participant-reported data reduces the available sample to assess post-op opioid consumption. Second, CYP2D6 phenotype distributions were unequal between genotype-guided and usual care arms, with the usual care group displaying higher IM and PM percentages than expected. This was possibly the result of adding the second study site over the course of the trial that had a less ancestrally diverse population, but not initially adjusting the randomization approach to account for a second site (e.g. randomizing separately by site). Nonetheless, adjusting for CYP2D6 phenotype did not affect the overall results. Third, only five providers were involved in the peri-operative care of these patients, and the high acceptance rate of genotype-guided recommendations observed in this study may not be generalizable across a larger provider group. However, surgeons have made opioid-sparing analgesic regimens a priority in clinical practice to reduce post-operative opioid use without compromising pain control. The overall study goals aligned with this clinical practice paradigm. Thus, surgeons were motivated to follow CYP2D6-guided recommendations, as evidenced by the high physician acceptance rate, which we expect may be true more generally. Fourth, differences in opioid consumption may be subject to a placebo-effect since study participants were not blinded. To mitigate a placebo-effect, CYP2D6 results were not actively provided to study participants. However, we cannot rule out that surgeons discussed results with patients or that CYP2D6 results were accessed through the patient portal. Finally, the practice of prescribing tramadol with another opioid, most commonly hydrocodone, suggests surgeons were not comfortable with prescribing tramadol as the sole post-operative opioid for NMs. Thus, further research to demonstrate whether use of tramadol alone in NMs results in sufficient pain control is warranted.

Future efforts will examine the effects of having CYP2D6 genotype on pain management and pain control. Findings from this study informed the design of a multi-center, NHGRI-funded, clinical trial (ADOPT-PGx: A Depression and Opioid Pragmatic Trial in Pharmacogenomics; https://gmkb.org/) evaluating the efficacy of a CYP2D6-guided approach on post-operative pain management as part of the IGNITE Pragmatic Trials Network.

In summary, preemptive CYP2D6-guided opioid selection is feasible in an elective surgery setting, with high patient acceptance of genotyping and provider acceptance of genotype-guided recommendations in PMs/IMs/UMs. We also show that CYP2D6 can be obtained in the pre-operative period after the decision for surgery is made so that results are available in time to guide post-operative opioid selection. Our results also suggest that a CYP2D6-guided approach may reduce post-operative opioid utilization without sacrificing pain control, with the greatest effect potentially in those undergoing more painful surgical procedures (e.g., TKA). Overall, utilizing a CYP2D6-guided approach to prescribe post-operative opioids is feasible and pain control may be achieved with less opioid use. In the current opioid climate, the need to develop safe and effective pain management strategies has never been more imperative, and precision medicine initiatives may prove invaluable.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by the University of Florida Clinical and Translational Science Institute, which is supported in part by the NIH National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences under award number UL1TR001427 and University of Florida Health Shands. Work by C.D.T. was supported by T32 HG008958. Research reported in this publication was also supported by NIH/NHGRI (U01 HG 007269). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Conflict of Interest Notification Page

Y.G., R.B.F., J.A.J., and L.H.C. have received research funding from the National Institutes of Health. P.S. receives support from University of Florida Health Pathology Laboratories. C.F.G. is a stockholder for ROMTech. The other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

ETHICS DECLARATION

All study participants provided written, informed consent. The study was approved by the University of Florida Institutional Review Board, and all procedures were in accordance with the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki and registered in ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT03534063).

DATA AVAILABILITY

Dataset and code available upon request.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gereau RWt, Sluka KA, Maixner W, et al. A pain research agenda for the 21st century. The journal of pain : official journal of the American Pain Society. 2014;15(12):1203–1214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hoots BE, Xu L, Kariisa M, et al. 2018. Annual surveillance report of drug-related risks and outcomes--United States. In: Services USDoHaH, ed2018. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levy B, Paulozzi L, Mack KA, Jones CM. Trends in Opioid Analgesic-Prescribing Rates by Specialty, U.S., 2007–2012. American journal of preventive medicine. 2015;49(3):409–413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aubrun F, Langeron O, Quesnel C, Coriat P, Riou B. Relationships between measurement of pain using visual analog score and morphine requirements during postoperative intravenous morphine titration. Anesthesiology. 2003;98(6):1415–1421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abdel Shaheed C, Maher CG, Williams KA, Day R, McLachlan AJ. Efficacy, Tolerability, and Dose-Dependent Effects of Opioid Analgesics for Low Back Pain: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(7):958–968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kalso E, Edwards JE, Moore RA, McQuay HJ. Opioids in chronic non-cancer pain: systematic review of efficacy and safety. Pain. 2004;112(3):372–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lopes GS, Bielinski SJ, Moyer AM, et al. Sex Differences in Associations Between CYP2D6 Phenotypes and Response to Opioid Analgesics. Pharmacogenomics and personalized medicine. 2020;13:71–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crews KR, Gaedigk A, Dunnenberger HM, et al. Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium guidelines for cytochrome P450 2D6 genotype and codeine therapy: 2014 update. Clinical pharmacology and therapeutics. 2014;95(4):376–382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crews KR, Gaedigk A, Dunnenberger HM, et al. Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium guidelines for cytochrome P450 2D6 genotype and codeine therapy: 2014 update. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2014;95(4):376–382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Volpe DA, McMahon Tobin GA, Mellon RD, et al. Uniform assessment and ranking of opioid mu receptor binding constants for selected opioid drugs. Regulatory toxicology and pharmacology : RTP. 2011;59(3):385–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ultram (tramadol) [package insert]. Titusville, NJ: Janssen Pharmaceutical Companies; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davis MP, Varga J, Dickerson D, Walsh D, LeGrand SB, Lagman R. Normal-release and controlled-release oxycodone: pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and controversy. Support Care Cancer. 2003;11(2):84–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smith DM, Weitzel KW, Elsey AR, et al. CYP2D6-guided opioid therapy improves pain control in CYP2D6 intermediate and poor metabolizers: a pragmatic clinical trial. Genetics in Medicine. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ciszkowski C, Madadi P, Phillips MS, Lauwers AE, Koren G. Codeine, ultrarapid-metabolism genotype, and postoperative death. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(8):827–828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gasche Y, Daali Y, Fathi M, et al. Codeine intoxication associated with ultrarapid CYP2D6 metabolism. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(27):2827–2831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koren G, Cairns J, Chitayat D, Gaedigk A, Leeder SJ. Pharmacogenetics of morphine poisoning in a breastfed neonate of a codeine-prescribed mother. Lancet. 2006;368(9536):704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kapil RP, Friedman K, Cipriano A, et al. Effects of paroxetine, a CYP2D6 inhibitor, on the pharmacokinetic properties of hydrocodone after coadministration with a single-entity, once-daily, extended-release hydrocodone tablet. Clinical therapeutics. 2015;37(10):2286–2296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Monte AA, Heard KJ, Campbell J, Hamamura D, Weinshilboum RM, Vasiliou V. The effect of CYP2D6 drug-drug interactions on hydrocodone effectiveness. Acad Emerg Med. 2014;21(8):879–885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Curran GM, Bauer M, Mittman B, Pyne JM, Stetler C. Effectiveness-implementation hybrid designs: combining elements of clinical effectiveness and implementation research to enhance public health impact. Medical care. 2012;50(3):217–226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Loudon K, Treweek S, Sullivan F, Donnan P, Thorpe KE, Zwarenstein M. The PRECIS-2 tool: designing trials that are fit for purpose. Bmj. 2015;350:h2147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gaedigk A, Simon SD, Pearce RE, Bradford LD, Kennedy MJ, Leeder JS. The CYP2D6 activity score: translating genotype information into a qualitative measure of phenotype. Clinical pharmacology and therapeutics. 2008;83(2):234–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hicks JK, Swen JJ, Gaedigk A. Challenges in CYP2D6 phenotype assignment from genotype data: a critical assessment and call for standardization. Current drug metabolism. 2014;15(2):218–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Borges S, Desta Z, Jin Y, et al. Composite functional genetic and comedication CYP2D6 activity score in predicting tamoxifen drug exposure among breast cancer patients. Journal of clinical pharmacology. 2010;50(4):450–458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim KM, Murray MD, Tu W, et al. Pharmacogenetics and healthcare outcomes in patients with chronic heart failure. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2012;68(11):1483–1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mosley SA, Hicks JK, Portman DG, et al. Design and rational for the precision medicine guided treatment for cancer pain pragmatic clinical trial. Contemp Clin Trials. 2018;68:7–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Adams EH, Breiner S, Cicero TJ, et al. A comparison of the abuse liability of tramadol, NSAIDs, and hydrocodone in patients with chronic pain. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2006;31(5):465–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Preston KL, Jasinski DR, Testa M. Abuse potential and pharmacological comparison of tramadol and morphine. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1991;27(1):7–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cella D, Yount S, Rothrock N, et al. The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS): progress of an NIH Roadmap cooperative group during its first two years. Medical care. 2007;45(5 Suppl 1):S3–s11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain--United States, 2016. Jama. 2016;315(15):1624–1645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Virtanen P, Gommers R, Oliphant TE, et al. SciPy 1.0: fundamental algorithms for scientific computing in Python. Nature Methods. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Han B, Compton WM, Blanco C, Crane E, Lee J, Jones CM. Prescription Opioid Use, Misuse, and Use Disorders in U.S. Adults: 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Annals of internal medicine. 2017;167(5):293–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dai F, Silverman DG, Chelly JE, Li J, Belfer I, Qin L. Integration of pain score and morphine consumption in analgesic clinical studies. The journal of pain : official journal of the American Pain Society. 2013;14(8):767–777.e768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brummett CM, Waljee JF, Goesling J, et al. New Persistent Opioid Use After Minor and Major Surgical Procedures in US Adults. JAMA surgery. 2017;152(6):e170504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ringwalt C, Gugelmann H, Garrettson M, et al. Differential prescribing of opioid analgesics according to physician specialty for Medicaid patients with chronic noncancer pain diagnoses. Pain Res Manag. 2014;19(4):179–185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wick EC, Grant MC, Wu CL. Postoperative Multimodal Analgesia Pain Management With Nonopioid Analgesics and Techniques: A Review. JAMA surgery. 2017;152(7):691–697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sjoveian AKH, Leegaard M. Hip and knee arthroplasty - patienťs experiences of pain and rehabilitation after discharge from hospital. International journal of orthopaedic and trauma nursing. 2017;27:28–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jhun EH, Apfelbaum JL, Dickerson DM, et al. Pharmacogenomic considerations for medications in the perioperative setting. Pharmacogenomics. 2019;20(11):813–827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Truong TM, Apfelbaum J, Shahul S, et al. The ImPreSS Trial: Implementation of Point-of-Care Pharmacogenomic Decision Support in Perioperative Care. Clinical pharmacology and therapeutics. 2019;106(6):1179–1183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Seripa D, Latina P, Fontana A, et al. Role of CYP2D6 Polymorphisms in the Outcome of Postoperative Pain Treatment. Pain medicine (Malden, Mass). 2015;16(10):2012–2023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dong H, Lu SJ, Zhang R, Liu DD, Zhang YZ, Song CY. Effect of the CYP2D6 gene polymorphism on postoperative analgesia of tramadol in Han nationality nephrectomy patients. European journal of clinical pharmacology. 2015;71(6):681–686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stamer UM, Lehnen K, Höthker F, et al. Impact of CYP2D6 genotype on postoperative tramadol analgesia. Pain. 2003;105(1–2):231–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Slanar O, Dupal P, Matouskova O, Vondrackova H, Pafko P, Perlik F. Tramadol efficacy in patients with postoperative pain in relation to CYP2D6 and MDR1 polymorphisms. Bratisl Lek Listy. 2012;113(3):152–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.