Abstract

Levels of circulating cell-free hemoglobin are elevated during hemolytic and inflammatory diseases and contribute to organ dysfunction and severity of illness. Though several studies have investigated the contribution of hemoglobin to tissue injury, the precise signaling mechanisms of hemoglobin-mediated endothelial dysfunction in the lung and other organs are not yet completely understood. The purpose of this review is to highlight the knowledge gained thus far and the need for further investigation regarding hemoglobin-mediated endothelial inflammation and injury to develop novel therapeutic strategies targeting the damaging effects of cell-free hemoglobin.

Keywords: endothelium, heme, hemoglobin, inflammation, lung injury, microvascular endothelial dysfunction

BACKGROUND

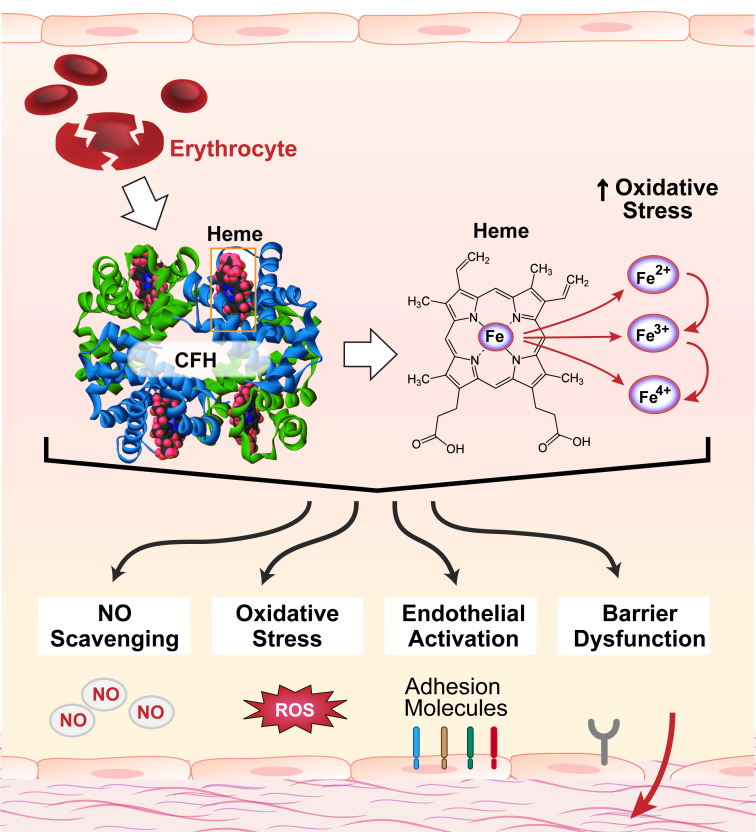

Increased circulating cell-free hemoglobin (CFH) is a characteristic of several pathologic entities, including hemolytic diseases, sickle cell anemia, and inflammatory conditions such as sepsis (Table 1). In sepsis, higher levels of plasma CFH are associated with disease severity and organ dysfunction (23), including injury to the lung (20). Red blood cell fragility and damage during these pathologies leads to release of hemoglobin into the intravascular space. Although there have been many reports implicating CFH in endothelial activation and injury over the past 30 years, the precise signaling mechanisms involved in CFH-mediated endothelial dysfunction are still unknown. Our current knowledge of CFH-induced endothelial injury is limited to mechanisms involving nitric oxide scavenging (1, 2, 5–7), oxidative stress (29–31), general endothelial cell activation (3, 8, 26, 32), and more recently, endothelial barrier dysfunction (25, 33, 34) (Fig. 1). Hemoglobin is composed of two α-globin and two β-globin subunits, each containing a heme group with a central iron atom. The iron can redox cycle from its oxygen-carrying ferrous (2+) form to ferric (3+, methemoglobin) or the highly reactive ferryl (4+) form. The multiple oxidation states and the potential for heme and iron to be released from hemoglobin adds to the difficulty of identifying specific mechanisms of cellular and tissue injury, especially in vivo since the oxidation state can change rapidly and heme and iron release are difficult to quantify at the tissue or cellular level. Complicating things further, free heme can itself induce hemolysis, releasing more CFH into the circulation (35). Considering this, the purpose of this review is to provide a comprehensive overview of the studies to date that have investigated CFH-mediated endothelial injury in the lung and nonpulmonary organs and to highlight the knowledge gaps and need for more in-depth studies of the underlying pathological processes of CFH-induced organ dysfunction. The potential molecular mechanisms related to CFH-mediated endothelial injury that are discussed in this review are summarized in Fig. 2.

Table 1.

Disease states associated with elevated circulating CFH

| Disorder | References |

|---|---|

| Hemolytic disorders | |

| Inherited (sickle cell disease, thalassemias) | (1–4) |

| Acquired [blood transfusion, Rh incompatibility, hemodialysis, cardiac surgery, preeclampsia, extracorporeal circulation (ECMO), malaria] | (5–16) |

| Pulmonary hypertension | (17–19) |

| Sepsis | (20–22) |

| Acute respiratory distress syndrome | (23) |

| Trauma/hemorrhage/transfusion-related acute lung injury (TRALI) | (24) |

| Primary graft dysfunction (PGD) after lung transplantation | (25) |

| Vasculopathies (atherosclerosis, intraventricular hemorrhage, subarachnoid hemorrhage) | (26–28) |

Figure 1.

Circulating cell-free hemoglobin (CFH) and its released components contribute to endothelial injury via NO scavenging, oxidative stress, endothelial activation, and endothelial barrier dysfunction. CFH is released from damaged red blood cells during several hemolytic and inflammatory pathologies. Elevated circulating levels of CFH are associated with higher risk of organ dysfunction and mortality. Hemoglobin is composed of two α-globin and two β-globin subunits, each consisting of an iron-containing heme group. The iron can redox cycle from its oxygen-carrying ferrous (2+) form to ferric (3+, methemoglobin) or the highly reactive ferryl (4+) form, which can oxidize lipids and other substrates, increasing oxidative stress. Moreover, there is potential for the release of heme and/or iron from circulating CFH, adding complexity to the contributions of CFH to endothelial injury. Mechanisms demonstrated to be involved in CFH-mediated endothelial injury include NO scavenging, oxidative stress, endothelial activation, and endothelial barrier dysfunction. NO, nitric oxide; ROS, reactive oxygen species.

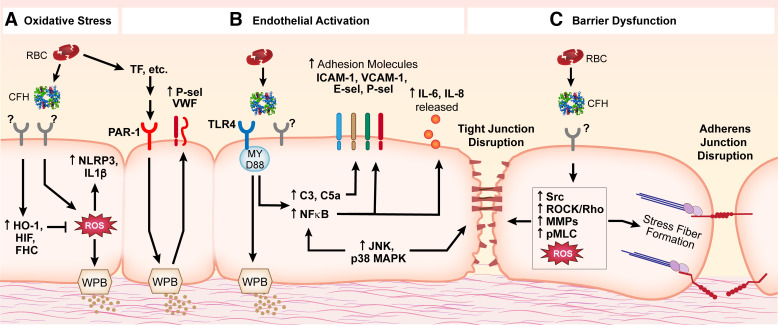

Figure 2.

Potential signaling mechanisms involved in CFH-mediated endothelial injury. Though the entirety of the precise signaling mechanisms contributing to endothelial injury is yet to be elucidated, multiple pathways have been implicated. A: CFH causes increased ROS that lead to activation of NLRP3 signaling and activation of IL-1β, as well as degranulation of WPBs. Protective cellular mechanisms activated by CFH include HO-1, HIF, and FHC to counter oxidative stress. B: endothelial activation in response to CFH signals through the TLR4/MyD88 pathway leading to activation of MAPKs, NF-κB and complement signaling, upregulation of adhesion molecules, and release of pro-inflammatory cytokines; PAR-1 activation by CFH-mediated upregulation of the TF signaling cascade leads to increased coagulation signaling (including increased VWF and P-selectin). C: endothelial barrier dysfunction induced by CFH or its components is characterized by disruption of cell-cell junctions (adherens junctions and tight junctions) and reorganization of the actin cytoskeleton (stress fiber formation); signaling mechanisms that may be involved include upregulation of MAPKs, Src, Rho, MMPs, and pMLC signaling. Many of these signaling pathways are complex and overlapping. Of note, some studies show that TLR4/MAPK/NLRP3 signaling was not required in CFH-mediated endothelial injury; the precise signaling mechanisms involved most likely depend on context and require further investigation. CFH, circulating cell-free hemoglobin; C3, complement component 3; C5a, complement component 5a; E-sel, E-selectin; FHC, ferritin heavy chain; HIF, hypoxia-inducible factor; HO-1, heme oxygenase-1; ICAM-1, intercellular adhesion molecule 1; IL-1β, interleukin 1 beta; IL-6, interleukin 6; IL-8, interleukin 8; JNK, c-Jun N-terminal kinases; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; MMPs, matrix metalloproteinases; MyD88, myeloid differentiation primary response 88; NF-κB, nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells; NLRP3, NOD-, LRR- and pyrin domain-containing protein 3; PAR-1, protease-activated receptor-1; pMLC, phosphorylated myosin light chain; P-sel, P-selectin; ROCK, Rho-associated protein kinase; ROS, reactive oxygen species; TF, tissue factor; TLR4, Toll-like receptor 4; VCAM-1, vascular cell adhesion protein 1; VWF, von Willebrand factor; WPB, Weibel-Palade bodies.

CELLULAR AND MOLECULAR MECHANISMS OF CFH-MEDIATED TOXICITY

Nitric Oxide Scavenging

It has been recognized for over 150 years that hemoglobin has the capacity to bind nitric oxide (NO) (36). A number of studies have demonstrated the ability of intravascular CFH to scavenge NO and impair vasodilation, especially during conditions such as sickle cell disease-induced hemolysis (1, 2, 4), blood transfusion with storage lesion (5), hemodialysis (6), and hemolysis during cardiac surgery (7). CFH-mediated NO scavenging leading to vasoconstriction triggers a downstream cascade of endothelial events including decreased blood flow, increased inflammation, platelet activation, and organ injury (37). The effects are amplified when the endothelium is already dysfunctional, as is seen in patients with hyperlipidemia or diabetes (38). In fact, infusion of hemoglobin in db/db (diabetic) mice or mice fed a high-fat diet induced severe systemic vasoconstriction, which was prevented with inhalation of NO (39). In mice with hemorrhagic shock, transfusion of red blood cells (RBCs) stored for an extended amount of time, i.e., “stored” or “old” RBCs (14 days for porcine/mouse and 35–40 days for human), which are more fragile and more prone to CFH release, led to increased levels of CFH and augmented inflammatory markers, oxidative stress, and death; the effects were exacerbated in mice fed a high-fat diet and improved with NO inhalation (9).

Oxidative Stress

Hemoglobin can exist in multiple oxidation states with differing pro-oxidant capacity depending on the oxidation state of the heme iron moiety. An oxidative environment can convert ferrous hemoglobin (Hb2+) to the ferric (Hb3+, methemoglobin) or a more highly reactive ferryl (Hb4+) form, both of which induce greater toxicity through oxidation of lipids (17, 40, 41) and lipoproteins (42). Highly oxidized forms of hemoglobin have been detected in plasma and urine samples of mice with intravascular hemolysis and in human samples of cerebrospinal fluid following intraventricular hemorrhage (43). In a clinical study of preeclampsia, which is characterized by high levels of circulating CFH, patients had higher plasma membrane peroxidation capability and higher plasma levels of protein carbonyl groups, markers of oxidation (10), suggesting that CFH was driving oxidative injury. Circulating oxidants, including reactive oxygen species (ROS), oxidized hemoglobin, or oxidized lipids, have the capability to activate and/or damage other cells such as leukocytes and red blood cells that can further increase the oxidative environment creating a feed-forward mechanism that can amplify endothelial injury (40, 44). Exposure of endothelial cells to oxidized forms of hemoglobin also increases pathways that protect against hemoglobin-induced oxidative injury including intracellular heme oxygenase and ferritin (29). When taken up by cells, heme is broken down by heme oxygenase to labile iron (which leads to ferritin production), carbon monoxide, and biliverdin (which can be converted to bilirubin). Deletion of the heme oxygenase-1 gene has been shown to exacerbate many pathologies in mouse models of disease (45, 46). Each of these breakdown products has demonstrated cytoprotective effects in response to toxic stimuli (47). For example, exogenous CO administration protected against hypoxic lung injury in rats (48), and CO exposure in vitro inhibited proinflammatory cytokine production in response to LPS (49). Bilirubin (50) and ferritin (51) both exert antioxidant properties to protect endothelial cells from oxidative stress. Together, these antioxidant and anti-inflammatory products of heme catabolism maintain cellular homeostasis by protecting against oxidative stress and death (45, 46). However, in the setting of hemoglobin or heme exposure, these protective responses can be overwhelmed resulting in, for example, susceptibility to the toxic effects of hydrogen peroxide-mediated cellular injury (29, 31).

Endothelial Activation

Endothelial cell (EC) activation is characterized by upregulation of inflammatory cytokines, adhesion molecules, and procoagulant mediators. Increased circulating CFH has been implicated in general EC activation in patients with hemolytic disease (3), malaria-induced intravascular hemolysis (8), ruptured atherosclerotic lesions, and intraventricular hemorrhage (26). Several studies in animal models have demonstrated hemolysis-mediated EC activation as well. For instance, in a phenylhydrazine (PHZ) model of intravascular hemolysis, several inflammatory and EC injury markers were elevated in kidneys and hemolysis led to multiorgan injury (52). In the same model, intravascular hemolysis led to complement-dependent liver damage involving Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) signaling and upregulation of P-selectin on the endothelial surface (53). A study by Wozniak et al. (11) lends further evidence to the importance of studying the inflammatory effects of increased levels of circulating CFH. In a swine model of blood transfusion, stored RBCs contributed to pulmonary endothelial dysfunction as indicated by increased pulmonary vascular resistance index, and lung injury as measured by functional, histological, and biochemical parameters of acute lung injury recommended by the American Thoracic Society (54). When the stored RBCs were washed mechanically, levels of CFH increased and were associated with increased endothelial activation and tissue injury; alternatively, RBC rejuvenation before transfusion using a Food and Drug Administration-approved method to increase cellular adenosine triphosphate (ATP) and 2,3-diphosphoglycerate (2,3-DPG), reduced plasma CFH and was associated with a reduction in endothelial dysfunction, leukocyte sequestration, and lung and kidney injury (11). Direct evidence of hemoglobin-mediated endothelial activation was reported by Liu and Spolarics who showed that stimulation of endothelial cells with ferric hemoglobin induced nuclear factor κ-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB)-mediated upregulation of adhesion molecules and release of chemokines and cytokines (32). Together, these studies indicate that CFH-mediated endothelial activation can contribute to lung damage in several pathophysiological contexts.

Barrier Dysfunction and Hyperpermeability

Endothelial barrier dysfunction leading to tissue edema can be triggered by inflammation and is especially deleterious in the lung, where disruption of the alveolar-capillary barrier causes pulmonary edema formation and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). It is increasingly apparent that high levels of circulating CFH during hemolytic and inflammatory pathologies disrupt the endothelial barrier, leading to microvascular hyperpermeability, edema, and organ dysfunction. Our group and others have shown that increased levels of CFH in patients during sepsis (20, 21), hemolytic anemia-associated pulmonary hypertension (55), and primary graft dysfunction after lung transplantation (25) are associated with increased lung injury and poor outcomes. Elevated plasma levels of CFH also lead to lung endothelial barrier dysfunction and lung microvascular hyperpermeability in rodent models of sickle cell disease (56), pulmonary hypertension (55), transfusion-induced acute lung injury (24), and sepsis (57). Direct hemoglobin infusion in an ex vivo-perfused human lung model resulted in increased lung weight and Evans blue-labeled albumin leakage from the circulation into the airspace, indicating increased vascular permeability (25). In vivo, hemoglobin injection caused blood-brain barrier disruption demonstrated by protein leak into brain tissue and loss of tight junction proteins; potential mechanisms include oxidative injury, indicated by increased staining of 4-hydroxynonenal (4-HNE, marker of lipid peroxidation) and 8-hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine (8-OHdG, marker of oxidative DNA damage) (58), apoptosis, determined by increased protein levels of cleaved caspase-3 (58), Rho kinase activation (59), and matrix metalloproteinase signaling (59). Though not lung specific, these studies offer clues to the potential mechanisms leading to alveolar-capillary barrier disruption due to increased circulating CFH.

In lung microvascular endothelial cells, direct hemoglobin stimulation has been shown to cause barrier dysfunction assessed by several measures, including decreased transendothelial electrical resistance (25, 33, 34), increased flux of protein across a monolayer (33, 34), cytoskeletal rearrangement and stress fiber formation (33), and formation of intercellular gaps (33). These effects have also been seen in other endothelial cell types, including pulmonary artery (60, 61), dermal (62), and aortic (63) endothelial cells. Many of these studies provide strong evidence for the role of oxidative stress in hemoglobin-mediated endothelial barrier dysfunction. For example, hemoglobin increases intracellular oxidative signaling as evidenced by induction of pathways that protect against oxidative injury such as heme oxygenase-1 (60) and hypoxia inducible factor (62). Hemoglobin-induced hyperpermeability can be reduced by antioxidant treatments such as n-acetylcysteine (NAC) (60, 61), ascorbate (34, 60), acetaminophen (a hemoprotein reductant) (25, 64), superoxide dismutase, or catalase (62). Furthermore, exposure to hyperoxia enhances hemoglobin-mediated lung endothelial permeability (25), and the ferryl (4+) form of hemoglobin is more potent than the ferric or ferrous forms (60, 65). In addition, although ferrous hemoglobin (Hb2+) alone did not cause endothelial barrier dysfunction in several endothelial cell types, including human lung microvascular endothelial cells, addition of glucose oxidase, a hydrogen peroxide-producing enzyme, stimulated a significant drop in transendothelial electrical resistance and loss of the adherens junction protein β-catenin at cell-cell contacts; the effects were prevented by haptoglobin, the endogenous scavenger of hemoglobin (66). Other signaling pathways involved in hemoglobin-induced endothelial barrier dysfunction include myeloid differentiation primary response 88 (MYD88) and NF-κB (62), as well as Src (61) or mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) (65). Conversely, others reported that blocking MAPKs, TLR4, NOD-, LRR-, and pyrin domain-containing protein 3 (NLRP3), or receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE) (61) did not reduce the barrier disrupting effects of RBC supernatants (containing increased levels of hemoglobin). The differences in reported signaling mechanisms could be explained by experimental use of lysed RBC supernatants rather than purified hemoglobin or differences in type of endothelial cell used. Of note, Lisk et al. (62) also reported that blocking TLR4 was unable to prevent barrier dysfunction of human dermal microvascular endothelial cells in response to direct stimulation with hemoglobin. Thus, although there is ample evidence for hemoglobin-induced endothelial barrier dysfunction and subsequent microvascular hyperpermeability across a variety of models and species, the precise signaling mechanisms may be tissue specific and are still incompletely elucidated.

CONTRIBUTION OF HEMOGLOBIN COMPONENTS TO CFH-MEDIATED TOXICITY

Toxic Effects of Heme

Although there is still much to parse out, several studies have advanced our understanding of the contribution of specific CFH components to hemoglobin-mediated injury and it is clear that free heme alone can induce many of the injurious effects observed for cell-free hemoglobin. The toxic effects of heme (or “hemin”—the chloride salt of heme used in many studies) have primarily been studied in the context of sickle cell disease (SCD), characterized by systemic hemolysis, inflammation, and coagulation. Infusion of hemoglobin or heme in SCD mice for 1 h induced vaso-occlusion and ischemic injury due to obstruction of the microcirculation by sickled RBCs; the authors concluded that heme was the major active molecule causing the effect since ferric hemoglobin, which was capable of releasing heme, caused much greater vaso-occlusion (measured by percent stasis) than cyanomethemoglobin (a form of hemoglobin in which heme cannot be released), and infusion of heme alone matched the percent stasis induced by hemoglobin (67). The authors also concluded that the intact iron was required since an iron-free heme mimic protoporphyrin IX (PPIX) had little effect on stasis. Further investigation into heme-induced vaso-occlusion revealed that hemoglobin or heme infusion in vivo or direct stimulation in vitro increased endothelial adhesion molecule surface expression, Weibel-Palade body (WPB) degranulation, oxidant production, and TLR4 signaling in mouse microvessels, human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs), or mouse pulmonary vein endothelial cells (mPVECs); antibodies blocking individual adhesion molecules, hemopexin (the primary endogenous scavenger of heme), NADPH oxidase (NOX) and protein kinase C (PKC) inhibitors, iron chelation, antioxidant NAC, and TLR4 inhibition or knockout all blocked the stasis induced by heme. In addition, inhibition of TLR4 blocked leukocyte rolling and adhesion, activation of NF-κB, and mortality induced by heme in SCD mice (67). Building upon this study, a recent investigation reported that inhibition of tissue factor, factor Xa, thrombin, or protease-activated receptor-1 (PAR-1) reduced stasis in a hemoglobin-infusion model of vaso-occlusive crisis in SCD mice (68). Another study showed that intact heme (but not ferrous or ferric hemoglobin, iron-free heme, or iron alone) stimulated NLRP3 inflammasome activation and production of interleukin 1 beta (IL-1β) in HUVECs; the effect was enhanced by LPS priming and partially dependent on ROS production (69). A recent study also showed heme-induced ROS production in HUVECs; the toxic effects could be prevented with hydroxyurea-induced upregulation of intracellular antioxidant systems (70). Though ferric hemoglobin stimulated heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1), ROS production, and IL-1β, much higher concentrations were needed than those required with heme. Heme-mediated activation of caspase-1 and cleavage of IL-1β was prevented in NLRP3 knockout mice (69). These results are supported by a report of red blood cell-derived microparticles containing high levels of heme, especially from patients with SCD, that transfer heme to HUVECs and induce apoptosis through activation of TLR4/ROS signaling (71). Mechanisms of heme- and iron-mediated endothelial cytotoxicity have been reviewed in more detail previously (72, 73).

Lung-Specific Heme-Mediated Endothelial Toxicity

Specific to the lung, direct stimulation of human lung microvascular endothelial cells with heme decreased transendothelial electrical resistance, increased barrier dysfunction as measured by flux of FITC-dextran, and induced necroptosis; barrier dysfunction and cell death were prevented by TLR4 inhibitor TAK-242, antioxidant NAC, iron chelator deferoxamine, and necroptosis inhibitor necrostatin-1 (74). A recent study also reported that heme-induced barrier dysfunction of human lung microvascular endothelial cells is characterized by disruption of tight junction proteins zonula occludens-1 (ZO-1), claudin-1, and claudin-5, activation of p22 and p38/MAPK pathways, and promotion of stress fiber formation (75). Heme injection (intravenous) into mice resulted in p38 activation [phosphorylation of p38 and upstream MAPK-activated protein kinase 2 (MK2) and dual specificity mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 3 (MKK3)], loss of tight junction proteins, and disruption of the lung endothelial barrier; the effects were blocked in MKK3−/− mice (75).

Complexity of Heme-Mediated Endothelial Responses

Though the above studies support an injurious effect of heme on the endothelium, not all studies support a role for heme alone. For instance, even though endothelial activation and vascular permeability were exacerbated in a model of intravascular hemolysis, particularly in the liver, there was no difference in alveolar-capillary barrier permeability in mice with genetic deletion of hemopexin, the primary endogenous scavenger of heme, compared to wild-type (76). One study even showed that pretreatment of human microvascular endothelial cells with hemin, the chloride salt of heme, inhibited permeability induced by hydrogen peroxide; however, hyperpermeability was exacerbated in bovine aortic endothelial cells (77). Conversely, heme administration to wild-type mice was not lethal, but greatly enhanced mortality in a cecal ligation and puncture (CLP) model of sepsis (22). The results of these studies indicate that the endothelial response to heme is complex, and it will be important to examine the differences in the inflammatory, pro-thrombotic, and barrier function responses in different vessels (conduit vs. microvascular) and specific tissue beds during distinct disease states.

Role for Iron in CFH-Mediated Endothelial Dysfunction

The role of free iron in hemoglobin-related endothelial dysfunction is even less well understood. As mentioned above, several studies point to a critical role for the iron moiety in hemoglobin- or heme-mediated endothelial injury (67, 69), and iron chelation has shown protection against hemoglobin- or heme-mediated endothelial dysfunction (67, 74). On one hand, one study showed free iron was not sufficient to activate endothelium (69). However, another study demonstrated that iron loading of endothelial cells contributes to cytotoxicity and lipid peroxidation (78). The mechanisms involved in iron-mediated endothelial dysfunction, particularly in the context of hemoglobin-mediated injury, require additional investigation.

THERAPEUTIC TARGETING OF CFH TO PRESERVE ENDOTHELIAL FUNCTION

Haptoglobin and Hemopexin

Haptoglobin and hemopexin are endogenous scavengers of hemoglobin and heme, respectively, and have been investigated for their usefulness in preventing hemoglobin-mediated injury and inflammation. Comprehensive reviews describing the role of endogenous hemoglobin scavengers and defense pathways during inflammatory processes, including sickle cell disease, pulmonary hypertension, vasculopathies, atherosclerosis, sepsis, and blood transfusion, have been published previously (79–81). Here, we will explore the potential benefit of exogenous administration of haptoglobin or hemopexin in pathologies with increased circulating levels of hemoglobin or heme.

Elevated plasma levels of cell-free hemoglobin are associated with poor outcomes in sepsis (20, 21), primary graft dysfunction (25), pulmonary arterial hypertension (18), acute respiratory distress syndrome (23), and blood transfusion (12), indicating hemoglobin-or heme-binding scavengers have potential in a number of acute and chronic pathological conditions. In a retrospective observational study of critically ill patients with sepsis, those with higher levels of haptoglobin or hemopexin were significantly less likely to die in the hospital using univariate analysis; using multivariate analysis, however, the significant association remained only with haptoglobin levels (21). In addition, Larsen et al. (22) observed an association of low hemopexin concentration with more organ dysfunction and increased mortality in patients with septic shock. In patients with SCD, low levels of haptoglobin or hemopexin were associated with increased lipid peroxidation; postmortem analysis of pulmonary artery and lung parenchyma tissue from patients with SCD and pulmonary hypertension (PH), in which haptoglobin and hemopexin levels were depleted, showed evidence of oxidized LDL deposits in the pulmonary artery, right ventricular fibrosis, and markers of endothelial dysfunction (82). Furthermore, in children with sickle cell anemia, the HP2-2 genotype, a common variant of the haptoglobin gene which has a lower affinity for binding plasma CFH, was associated with an increased risk for the development of acute severe vaso‐occlusive pain episodes (83). Interestingly, removing hemoglobin from cerebral spinal fluid derived from patients with subarachnoid hemorrhage via haptoglobin sequestration restored vasodilatory responses to NO in isolated arteries ex vivo (27).

In several animal models of increased levels of CFH, haptoglobin and hemopexin have been shown to protect against severity of tissue damage, organ dysfunction, and death. In mice with septic shock and RBC transfusion, infusion of haptoglobin or hemopexin improved survival, attenuated inflammation, and prevented hemoglobinuria and kidney injury (84). Haptoglobin infusion also attenuated organ damage and disease severity in a canine model of pneumonia (85), a guinea pig model of blood transfusion with storage lesion (86), a rat model of pulmonary hypertension (17), a rat model of hemolysis (87), and a sheep model of hemoglobin-induced cerebral vasospasm (27). Glucocorticoid stimulation of endogenous haptoglobin synthesis reduced the hemoglobin-induced hypertensive response in canines, and haptoglobin infusion in guinea pigs prevented hypertension, hemoglobinuria, peroxidative activity, and oxidative tissue damage in response to CFH infusion (88). In mice deficient in heme oxygenase-1, sepsis induced by low-grade cecal ligation and puncture resulted in increased plasma levels of hemoglobin and heme, decreased levels of haptoglobin and hemopexin, organ injury indicated by histological detection of necrosis in liver, kidney, and heart tissue with corresponding increased plasma levels of aspartate aminotransferase (AST), blood urea nitrogen (BUN), and creatinine phosphokinase (CPK), and mortality; restoration of hemopexin prevented the negative outcomes (22). Hemopexin was also able to prevent heme loading of the vascular endothelium and subsequent endothelial activation, oxidative stress, and cardiac function in SCD mice (89). Notably, purified human haptoglobin is approved in Japan for clinical use during several hemolytic processes including cardiopulmonary bypass surgery, massive transfusion, and extracorporeal circulation, among others (90).

Acetaminophen and Ascorbate

In 2010, Boutaud et al. (91) discovered that the commonly used analgesic acetaminophen was able to inhibit hemoprotein-induced lipid peroxidation by reducing ferryl to ferric heme and quenching globin radicals. Acetaminophen administration decreased oxidant injury and tissue damage and improved kidney function in a rat rhabdomyolysis model. This study revealed the potential therapeutic application for acetaminophen in diseases involving hemoprotein-mediated injury. Specific to CFH-mediated lung injury, acetaminophen was shown to prevent vascular permeability in an ex vivo perfused human lung model and in human lung microvascular endothelial cells in response to direct CFH stimulation (25). In a retrospective study, Janz et al. (21) observed that patients with elevated circulating levels of CFH who received acetaminophen during ICU admission had decreased plasma levels of oxidative injury markers and lower risk of death in the hospital independent of other risk factors for poor outcomes. Building on this, in a single center, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 2 clinical trial in patients with sepsis with detectable plasma levels of CFH, acetaminophen (1 g every 6 h for 3 days, enteral administration) reduced oxidative injury and improved renal function (92) compared to placebo treatment. Furthermore, in patients with severe falciparum malaria with prominent intravascular hemolysis, a phase 2, open-label, randomized controlled trial (NCT01641289) demonstrated that acetaminophen (1 g every 6 h for 3 days, enteral administration) reduced creatinine levels, indicating renoprotection; the therapy was most effective in patients with higher plasma hemoglobin levels (>45,000 ng/mL) (13). These studies provide compelling preclinical and clinical evidence for potential utility of acetaminophen for treatment of pathologic entities associated with elevations in circulating cell-free hemoglobin. A prospective multicenter phase 2 b randomized placebo-controlled double-blinded interventional platform trial, Acetaminophen and Ascorbate in Sepsis: Targeted Therapy to Enhance Recovery (ASTER), has been proposed (NCT04291508) to investigate the clinical efficacy of acetaminophen for patients with evidence of sepsis-induced hemodynamic or respiratory failure. Interestingly, the other arm of the proposed ASTER trial investigating ascorbate in critically ill patients could also be effective for hemoglobin-mediated pathologies. Ascorbate, a potent antioxidant, has been shown to attenuate CFH-mediated endothelial barrier dysfunction (34, 60).

Other Potential Therapeutic Options

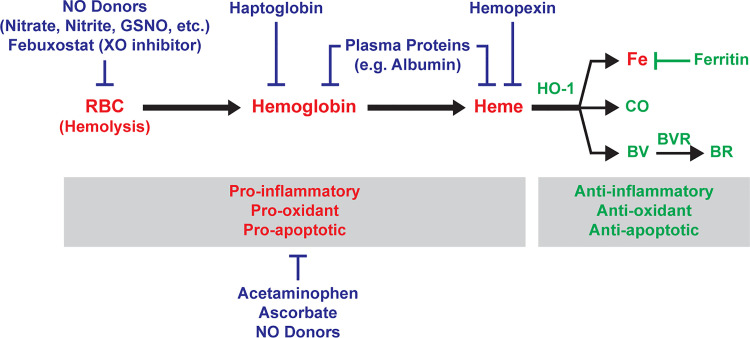

Therapeutic strategies for hemoglobin-mediated endothelial injury (Table 2) could target several facets of the pathophysiologic process, including prevention of hemolysis, neutralization of hemoglobin or its released products, inhibition of downstream signaling mechanisms, or repair of tissue injury (Fig. 3). A combination of these strategies may provide greater and/or longer lasting benefits. One such therapy tested during hemolysis-induced inflammation in normal and SCD mice is nitrite. Nitrite is able to reduce hemolysis, deliver NO to areas of hypoxia, and reduce platelet and leukocyte adhesion to endothelium (94). Nitrite therapy has also been shown to decrease transfusion-related acute lung injury in mice (24). A recent study confirmed the ability of nitrite, along with additional NO donors, to protect RBCs from hemolysis; the most effective was S-nitrosoglutathione (GSNO) (95). A recent study in SCD mice also showed that inhibition of xanthine oxidase, a potent inducer of oxidant production, with febuxostat decreased hemolysis, indicated by a decrease of circulating CFH and increase in circulating haptoglobin levels, and improved pulmonary vasoreactivity, measured by wire myography of isolated arteries (96). The endogenous scavengers of hemoglobin and heme have already been discussed, but other options for neutralizing hemoglobin are possible. In fact, plasma proteins such as albumin are known to bind hemoglobin and heme, and it has been shown that hemoproteins must be unbound in the plasma to stimulate inflammatory responses in the endothelium (69, 93). However, albumin was not sufficient to prevent inflammation or improve survival during RBC transfusion in mice with septic shock (84). Targeting hemolysis or circulating hemoglobin may be beneficial in early stages of critical illness or for chronic illness but targeting downstream mechanisms may be required when damage is already done. Especially when it comes to disruption of the alveolar-capillary barrier, it will be important to investigate strategies to enhance barrier function or repair dysfunctional endothelium to improve outcomes in inflammatory injury; the many strategies currently being investigated are beyond the scope of this review.

Table 2.

Potential therapies targeting CFH-mediated endothelial injury

| Therapy | Method of Action | References |

|---|---|---|

| Haptoglobin | Endogenous scavenger of hemoglobin | (17, 21, 27, 66, 80, 82, 84–86, 88, 90) |

| Hemopexin | Endogenous scavenger of heme | (22, 80, 82, 84, 89, 90) |

| Plasma proteins (e.g. albumin) | Binds hemoglobin/heme | (69, 93) |

| Acetaminophen | Hemoprotein reductant | NCT04291508 (21, 25, 91, 92) |

| Ascorbate | Antioxidant | (34, 89) |

| NO donors [nitrite, nitrate, spermine NONOate (SPNO), S-nitrosoglutathione (GSNO)] | Delivers NO (increases bioavailability in hypoxic areas and reduces hemolysis) | (24, 94, 95) |

| Febuxostat | Xanthine oxidase inhibitor | (96) |

Figure 3.

Potential therapeutic strategies that target CFH-mediated endothelial injury. [Color key: Red = Injurious, Green = Cytoprotective, Blue = Potential therapies] Hemolysis (lysis of red blood cells) in the circulation releases CFH and subsequent free heme to affect endothelial function via oxidative stress and inflammation. Intracellular anti-inflammatory, anti-oxidant, and anti-apoptotic pathways driven by upregulation of HO-1 break down heme into labile iron (which leads to production of cytoprotective ferritin), CO, and biliverdin (which is converted to bilirubin by biliverdin reductase). Potential therapies against CFH-mediated endothelial injury are aimed at targeting hemolysis (NO donors such as nitrate, nitrite, GSNO, or Febuxostat), CFH (haptoglobin, plasma proteins), heme (hemopexin, plasma proteins), or oxidative stress/inflammation (acetaminophen, ascorbate, NO donors). BR, bilirubin; BV, biliverdin; BVR, biliverdin reductase; CFH, cell-free hemoglobin; CO, carbon monoxide; Fe, iron; GSNO, S-nitrosoglutathione; HO-1, heme oxygenase-1; RBC, red blood cells; XO, xanthine oxidase; NO, nitric oxide.

Ongoing Research Priorities

Further investigation into the pathophysiology and therapeutic targeting of CFH-mediated endothelial dysfunction holds promise in several inflammatory and hemolytic conditions. Questions remain regarding how different disease states induce red cell fragility leading to release of hemoglobin and its components, the cellular mechanisms by which CFH and heme interact with the endothelium, what downstream signaling mechanisms play a role in CFH-mediated endothelial injury, and how each step in this process can be efficiently targeted. Therapeutic strategies to neutralize CFH or heme with haptoglobin or hemopexin, respectively, or downstream effectors, have been mostly limited to preclinical studies (97); moving these investigations into clinical trials is necessary to evaluate their effectiveness in a variety of inflammatory syndromes. Though clinical trials using acetaminophen during conditions in which CFH is elevated show promise in reducing organ injury, more investigation into its potential benefits is required. Additionally, more work should be done to investigate the potential for pharmacologic interventions already being used to target vascular dysfunction, especially those targeting oxidative pathways such as vitamin C, xanthine oxidase, or polyphenols [recently reviewed by Daiber and Chlopicki (98)], in the context of CFH- and heme-mediated pathologies. Additionally, circulating levels of CFH, heme, haptoglobin, or hemopexin may have value as biomarkers. Preclinical and clinical evidence shows associations of changes in the circulating levels of these proteins with poor outcomes in sepsis (21, 99, 100), pulmonary hypertension (18), subarachnoid hemorrhage (101), preeclampsia (102), and cardiopulmonary bypass (103). In addition, measurement of CFH was used to identify patients with elevated circulating CFH for enrollment in a pilot clinical trial of acetaminophen to target CFH-mediated oxidative injury in patients with sepsis (92); a similar approach could be used to target other therapies such as scavengers of CFH and heme to patients with elevated CFH who would be more likely to benefit from these strategies. Evaluating and combining strategies to prevent hemolysis, measure and neutralize hemoglobin and its released components, and interrupt downstream signaling events involved in CFH-mediated endothelial injury in preclinical and clinical studies in which circulating CFH is elevated has potential to uncover novel therapeutic strategies for a number of inflammatory and hemolytic conditions.

CLOSING REMARKS

Evidence continues to grow for the contributions of elevated circulating levels of CFH and its components to endothelial injury in disease states characterized by red cell fragility and damage. The complex pathophysiological processes involved in hemolytic and inflammatory diseases in which circulating CFH contributes to endothelial injury will most likely require a multifaceted therapeutic approach to improve patient outcomes. Further investigation into the precise signaling mechanisms involved in CFH-mediated endothelial injury utilizing complex physiological disease models with translational potential is warranted to reach this goal.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) Grant HL094296 (to J.E.M.), NHLBI Grant HL135849 (to J.A.B. and L.B.W.), and NHLBI Grant HL103836 (to L.B.W.).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

J.E.M., J.A.B., and L.B.W. prepared figures; J.E.M. drafted manuscript; J.E.M., J.A.B., and L.B.W. edited and revised manuscript; J.E.M., J.A.B., and L.B.W. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Diana Lim (University of Utah Molecular Medicine Program) for excellent work in designing the figures for this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hsu LL, Champion HC, Campbell-Lee SA, Bivalacqua TJ, Manci EA, Diwan BA, Schimel DM, Cochard AE, Wang X, Schechter AN, Noguchi CT, Gladwin MT. Hemolysis in sickle cell mice causes pulmonary hypertension due to global impairment in nitric oxide bioavailability. Blood 109: 3088–3098, 2007. [Erratum in Blood 111: 1772, 2008]. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-08-039438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Detterich JA, Kato RM, Rabai M, Meiselman HJ, Coates TD, Wood JC. Chronic transfusion therapy improves but does not normalize systemic and pulmonary vasculopathy in sickle cell disease. Blood 126: 703–710, 2015. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-12-614370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Atichartakarn V, Chuncharunee S, Archararit N, Udomsubpayakul U, Aryurachai K. Intravascular hemolysis, vascular endothelial cell activation and thrombophilia in splenectomized patients with hemoglobin E/beta-thalassemia disease. Acta Haematol 132: 100–107, 2014. doi: 10.1159/000355719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reiter CD, Wang X, Tanus-Santos JE, Hogg N, Cannon RO 3rd, Schechter AN, Gladwin MT. Cell-free hemoglobin limits nitric oxide bioavailability in sickle-cell disease. Nat Med 8: 1383–1389, 2002. doi: 10.1038/nm1202-799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Donadee C, Raat NJ, Kanias T, Tejero J, Lee JS, Kelley EE, Zhao X, Liu C, Reynolds H, Azarov I, Frizzell S, Meyer EM, Donnenberg AD, Qu L, Triulzi D, Kim-Shapiro DB, Gladwin MT. Nitric oxide scavenging by red blood cell microparticles and cell-free hemoglobin as a mechanism for the red cell storage lesion. Circulation 124: 465–476, 2011. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.008698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meyer C, Heiss C, Drexhage C, Kehmeier ES, Balzer J, Muhlfeld A, Merx MW, Lauer T, Kuhl H, Floege J, Kelm M, Rassaf T. Hemodialysis-induced release of hemoglobin limits nitric oxide bioavailability and impairs vascular function. J Am Coll Cardiol 55: 454–459, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.07.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vermeulen Windsant IC, de Wit NC, Sertorio JT, van Bijnen AA, Ganushchak YM, Heijmans JH, Tanus-Santos JE, Jacobs MJ, Maessen JG, Wa B. Hemolysis during cardiac surgery is associated with increased intravascular nitric oxide consumption and perioperative kidney and intestinal tissue damage. Front Physiol 5: 340, 2014. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2014.00340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barber BE, Grigg MJ, Piera KA, William T, Cooper DJ, Plewes K, Dondorp AM, Yeo TW, Anstey NM. Intravascular haemolysis in severe Plasmodium knowlesi malaria: association with endothelial activation, microvascular dysfunction, and acute kidney injury. Emerg Microbes Infect 7: 106, 2018. doi: 10.1038/s41426-018-0105-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lei C, Yu B, Shahid M, Beloiartsev A, Bloch KD, Zapol WM. Inhaled nitric oxide attenuates the adverse effects of transfusing stored syngeneic erythrocytes in mice with endothelial dysfunction after hemorrhagic shock. Anesthesiology 117: 1190–1202, 2012. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e318272d866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Olsson MG, Centlow M, Rutardottir S, Stenfors I, Larsson J, Hosseini-Maaf B, Olsson ML, Hansson SR, Akerstrom B. Increased levels of cell-free hemoglobin, oxidation markers, and the antioxidative heme scavenger alpha(1)-microglobulin in preeclampsia. Free Radic Biol Med 48: 284–291, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.10.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Woźniak MJ, Qureshi S, Sullo N, Dott W, Cardigan R, Wiltshire M, Nath M, Patel NN, Kumar T, Goodall AH, Murphy GJ. A comparison of red cell rejuvenation versus mechanical washing for the prevention of transfusion-associated organ injury in swine. Anesthesiology 128: 375–385, 2018. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000001973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vermeulen Windsant IC, de Wit NC, Sertorio JT, Beckers EA, Tanus-Santos JE, Jacobs MJ, Wa B. Blood transfusions increase circulating plasma free hemoglobin levels and plasma nitric oxide consumption: a prospective observational pilot study. Crit Care 16: R95, 2012. doi: 10.1186/cc11359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Plewes K, Kingston HWF, Ghose A, Wattanakul T, Hassan MMU, Haider MS, et al. Acetaminophen as a renoprotective adjunctive treatment in patients with severe and moderately severe falciparum malaria: a randomized, controlled, open-label trial. Clin Infect Dis 67: 991–999, 2018. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciy213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Murphy DA, Hockings LE, Andrews RK, Aubron C, Gardiner EE, Pellegrino VA, Davis AK. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation-hemostatic complications. Transfus Med Rev 29: 90–101, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.tmrv.2014.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vermeulen Windsant IC, Hanssen SJ, Buurman WA, Jacobs MJ. Cardiovascular surgery and organ damage: time to reconsider the role of hemolysis. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 142: 1–11, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2011.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vermeulen Windsant IC, Snoeijs MG, Hanssen SJ, Altintas S, Heijmans JH, Koeppel TA, Schurink GW, Buurman WA, Jacobs MJ. Hemolysis is associated with acute kidney injury during major aortic surgery. Kidney Int 77: 913–920, 2010. doi: 10.1038/ki.2010.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Irwin DC, Baek JH, Hassell K, Nuss R, Eigenberger P, Lisk C, Loomis Z, Maltzahn J, Stenmark KR, Nozik-Grayck E, Buehler PW. Hemoglobin-induced lung vascular oxidation, inflammation, and remodeling contribute to the progression of hypoxic pulmonary hypertension and is attenuated in rats with repeated-dose haptoglobin administration. Free Radic Biol Med 82: 50–62, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2015.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brittain EL, Janz DR, Austin ED, Bastarache JA, Wheeler LA, Ware LB, Hemnes AR. Elevation of plasma cell-free hemoglobin in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Chest 146: 1478–1485, 2014. doi: 10.1378/chest.14-0809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Buehler PW, Baek JH, Lisk C, Connor I, Sullivan T, Kominsky D, Majka S, Stenmark KR, Nozik-Grayck E, Bonaventura J, Irwin DC. Free hemoglobin induction of pulmonary vascular disease: evidence for an inflammatory mechanism. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 303: L312–L326, 2012. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00074.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kerchberger VE, Bastarache JA, Shaver CM, Nagata H, McNeil JB, Landstreet SR, Putz ND, Yu W-K, Jesse J, Wickersham NE, Sidorova TN, Janz DR, Parikh CR, Siew ED, Ware LB. Haptoglobin-2 variant increases susceptibility to acute respiratory distress syndrome during sepsis. JCI Insight 4: e131206, 2019. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.131206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Janz DR, Bastarache JA, Peterson JF, Sills G, Wickersham N, May AK, Roberts LJ, Ware LB. Association between cell-free hemoglobin, acetaminophen, and mortality in patients with sepsis: An observational study. Crit Care Med 41: 784–790, 2013. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182741a54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Larsen R, Gozzelino R, Jeney V, Tokaji L, Bozza FA, Japiassú AM, Bonaparte D, Cavalcante MM, Chora Â, Ferreira A, Marguti I, Cardoso S, Sepúlveda N, Smith A, Soares MP. A central role for free heme in the pathogenesis of severe sepsis. Sci Transl Med 2: 51ra71, 2010. 51ra71doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3001118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Janz DR, Ware LB. The role of red blood cells and cell-free hemoglobin in the pathogenesis of ARDS. J Intensive Care 3: 20, 2015. doi: 10.1186/s40560-015-0086-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stapley R, Rodriguez C, Oh JY, Honavar J, Brandon A, Wagener BM, Marques MB, Weinberg JA, Kerby JD, Pittet JF, Patel RP. Red blood cell washing, nitrite therapy, and antiheme therapies prevent stored red blood cell toxicity after trauma-hemorrhage. Free Rad Biol Med 85: 207–218, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2015.04.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shaver CM, Wickersham N, McNeil JB, Nagata H, Miller A, Landstreet SR, Kuck JL, Diamond JM, Lederer DJ, Kawut SM, Palmer SM, Wille KM, Weinacker A, Lama VN, Crespo MM, Orens JB, Shah PD, Hage CA, Cantu E, Porteous MK, Dhillon G, McDyer J, Bastarache JA, Christie JD, Ware LB. Cell-free hemoglobin promotes primary graft dysfunction through oxidative lung endothelial injury. JCI Insight 3: 1–12, 2018. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.98546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Posta N, Csősz É, Oros M, Pethő D, Potor L, Kalló G, Hendrik Z, Sikura KÉ, Méhes G, Tóth C, Posta J, Balla G, Balla J. Hemoglobin oxidation generates globin-derived peptides in atherosclerotic lesions and intraventricular hemorrhage of the brain, provoking endothelial dysfunction. Lab Invest 100: 986–1002, 2020. doi: 10.1038/s41374-020-0403-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hugelshofer M, Buzzi RM, Schaer CA, Richter H, Akeret K, Anagnostakou V, Mahmoudi L, Vaccani R, Vallelian F, Deuel JW, Kronen PW, Kulcsar Z, Regli L, Baek JH, Pires IS, Palmer AF, Dennler M, Humar R, Buehler PW, Kircher PR, Keller E, Schaer DJ. Haptoglobin administration into the subarachnoid space prevents hemoglobin-induced cerebral vasospasm. J Clin Invest 129: 5219–5235, 2019. doi: 10.1172/JCI130630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Michel JB, Martin-Ventura JL. Red blood cells and hemoglobin in human atherosclerosis and related arterial diseases. Int J Mol Sci 21: 6756, 2020. doi: 10.3390/ijms21186756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Balla J, Jacob HS, Balla G, Nath K, Eaton JW, Vercellotti GM. Endothelial-cell heme uptake from heme proteins: induction of sensitization and desensitization to oxidant damage. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 90: 9285–9289, 1993. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.20.9285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Balla J, Nath KA, Balla G, Juckett MB, Jacob HS, Vercellotti GM. Endothelial cell heme oxygenase and ferritin induction in rat lung by hemoglobin in vivo. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 268: L321–L327, 1995. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1995.268.2.L321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.D'Agnillo F, Alayash AI. Interactions of hemoglobin with hydrogen peroxide alters thiol levels and course of endothelial cell death. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 279: H1880–H1889, 2000. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.279.4.H1880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu X, Spolarics Z. Methemoglobin is a potent activator of endothelial cells by stimulating IL-6 and IL-8 production and E-selectin membrane expression. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 285: C1036–C1046, 2003. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00164.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dull RO, DeWitt BJ, Dinavahi R, Schwartz L, Hubert C, Pace N, Fronticelli C. Quantitative assessment of hemoglobin-induced endothelial barrier dysfunction. J Appl Physiol (1985) 97: 1930–1937, 2004. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00102.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kuck JL, Bastarache JA, Shaver CM, Fessel JP, Dikalov SI, May JM, Ware LB. Ascorbic acid attenuates endothelial permeability triggered by cell-free hemoglobin. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 495: 433–437, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2017.11.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kumar S, Bandyopadhyay U. Free heme toxicity and its detoxification systems in human. Toxicol Lett 157: 175–188, 2005. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2005.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hermann L. Ueber die Wirkungen des Stickstoffoxydgasses auf das Blut [On the effects of nitrogen oxide gas on the blood]. Arch Anat Physiol Sci Med 469–481, 1865. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gladwin MT, Crawford JH, Patel RP. The biochemistry of nitric oxide, nitrite, and hemoglobin: role in blood flow regulation. Free Radic Biol Med 36: 707–717, 2004. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2003.11.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Graw JA, Yu B, Rezoagli E, Warren HS, Buys ES, Bloch DB, Zapol WM. Endothelial dysfunction inhibits the ability of haptoglobin to prevent hemoglobin-induced hypertension. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 312: H1120–H1127, 2017. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00851.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yu B, Shahid M, Egorina EM, Sovershaev MA, Raher MJ, Lei C, Wu MX, Bloch KD, Zapol WM. Endothelial dysfunction enhances vasoconstriction due to scavenging of nitric oxide by a hemoglobin-based oxygen carrier. Anesthesiology 112: 586–594, 2010. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181cd7838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nagy E, Eaton JW, Jeney V, Soares MP, Varga Z, Galajda Z, Szentmiklosi J, Mehes G, Csonka T, Smith A, Vercellotti GM, Balla G, Balla J. Red cells, hemoglobin, heme, iron, and atherogenesis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 30: 1347–1353, 2010. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.206433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Loomis Z, Eigenberger P, Redinius K, Lisk C, Karoor V, Nozik-Grayck E, Ferguson SK, Hassell K, Nuss R, Stenmark K, Buehler P, Irwin DC. Hemoglobin induced cell trauma indirectly influences endothelial TLR9 activity resulting in pulmonary vascular smooth muscle cell activation. PLoS One 12: e0171219–e0171221, 2017. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0171219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Balla G, Jacob HS, Eaton JW, Belcher JD, Vercellotti GM. Hemin: a possible physiological mediator of low density lipoprotein oxidation and endothelial injury. Arterios Thromb Vas Biol 11: 1700–1711, 1991. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.11.6.1700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nyakundi BB, Erdei J, Tóth A, Balogh E, Nagy A, Nagy B, Novák L, Bognár L, Paragh G, Kappelmayer J, Jeney V. Formation and detection of highly oxidized hemoglobin forms in biological fluids during hemolytic conditions. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2020: 8929020, 2020. doi: 10.1155/2020/8929020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kiefmann R, Rifkind JM, Nagababu E, Bhattacharya J. Red blood cells induce hypoxic lung inflammation. Blood 111: 5205–5214, 2008. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-09-113902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gozzelino R, Jeney V, Soares MP. Mechanisms of cell protection by heme oxygenase-1. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 50: 323–354, 2010. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.010909.105600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Soares MP, Bach FH. Heme oxygenase-1: from biology to therapeutic potential. Trends Mol Med 15: 50–58, 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2008.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Otterbein LE, Soares MP, Yamashita K, Bach FH. Heme oxygenase-1: unleashing the protective properties of heme. Trends Immunol 24: 449–455, 2003. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(03)00181-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Otterbein LE, Mantell LL, Choi AM. Carbon monoxide provides protection against hyperoxic lung injury. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 276: L688–L694, 1999. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1999.276.4.L688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Otterbein LE, Bach FH, Alam J, Soares M, Tao Lu H, Wysk M, Davis RJ, Flavell RA, Choi AM. Carbon monoxide has anti-inflammatory effects involving the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway. Nat Med 6: 422–428, 2000. doi: 10.1038/74680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stocker R, Yamamoto Y, McDonagh AF, Glazer AN, Ames BN. Bilirubin is an antioxidant of possible physiological importance. Science 235: 1043–1046, 1987. doi: 10.1126/science.3029864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Balla G, Jacob HS, Balla J, Rosenberg M, Nath K, Apple F, Eaton JW, Vercellotti GM. Ferritin: a cytoprotective antioxidant strategem of endothelium. J Biol Chem 267: 18148–18153, 1992. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Merle NS, Grunenwald A, Figueres ML, Chauvet S, Daugan M, Knockaert S, Robe-Rybkine T, Noe R, May O, Frimat M, Brinkman N, Gentinetta T, Miescher S, Houillier P, Legros V, Gonnet F, Blanc-Brude OP, Rabant M, Daniel R, Dimitrov JD, Roumenina LT. Characterization of renal injury and inflammation in an experimental model of intravascular hemolysis. Front Immunol 9: 1–13, 2018. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.00179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Merle NS, Paule R, Leon J, Daugan M, Robe-Rybkine T, Poillerat V, Torset C, Frémeaux-Bacchi V, Dimitrov JD, Roumenina LT. P-selectin drives complement attack on endothelium during intravascular hemolysis in TLR-4/heme-dependent manner. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 116: 6280–6285, 2019. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1814797116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Matute-Bello G, Downey G, Moore BB, Groshong SD, Matthay MA, Slutsky AS, Kuebler WM; Acute Lung Injury in Animals Study G. An official American Thoracic Society workshop report: features and measurements of experimental acute lung injury in animals. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 44: 725–738, 2011. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2009-0210ST. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rafikova O, Williams ER, McBride ML, Zemskova M, Srivastava A, Nair V, Desai AA, Langlais PR, Zemskov E, Simon M, Mandarino LJ, Rafikov R. Hemolysis-induced lung vascular leakage contributes to the development of pulmonary hypertension. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 59: 334–345, 2018. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2017-0308OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ghosh S, Tan F, Ofori-Acquah SF. Spatiotemporal dysfunction of the vascular permeability barrier in transgenic mice with sickle cell disease. Anemia 2012: 582018–582018, 2012. doi: 10.1155/2012/582018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Meegan JE, Shaver CM, Putz ND, Jesse JJ, Landstreet SR, Lee HNR, Sidorova TN, McNeil JB, Wynn JL, Cheung-Flynn J, Komalavilas P, Brophy CM, Ware LB, Bastarache JA. Cell-free hemoglobin increases inflammation, lung apoptosis, and microvascular permeability in murine polymicrobial sepsis. PLoS One 15: e0228727, 2020. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0228727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Butt OI, Buehler PW, D'Agnillo F. Blood-brain barrier disruption and oxidative stress in guinea pig after systemic exposure to modified cell-free hemoglobin. Am J Pathol 178: 1316–1328, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2010.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fu Z, Chen Y, Qin F, Yang S, Deng X, Ding R, Feng L, Li W, Zhu J. Increased activity of Rho kinase contributes to hemoglobin-induced early disruption of the blood-brain barrier in vivo after the occurrence of intracerebral hemorrhage. Int J Clin Exp Pathol 7: 7844–7853, 2014. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jana S, Meng F, Hirsch RE, Friedman JM, Alayash AI. Oxidized mutant human hemoglobins S and E induce oxidative stress and bioenergetic dysfunction in human pulmonary endothelial cells. Front Physiol 8: 1082, 2017. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2017.01082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kim J, Nguyen TTT, Li Y, Zhang CO, Cha B, Ke Y, Mazzeffi MA, Tanaka KA, Birukova AA, Birukov KG. Contrasting effects of stored allogeneic red blood cells and their supernatants on permeability and inflammatory responses in human pulmonary endothelial cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 318: L533–L–548., 2020. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00025.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lisk C, Kominsky D, Ehrentraut S, Bonaventura J, Nuss R, Hassell K, Nozik-Grayck E, Irwin DC. Hemoglobin-induced endothelial cell permeability is controlled, in part, via a myeloid differentiation primary response gene-88-dependent signaling mechanism. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 49: 619–626, 2013. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2012-0440OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Potor L, Nagy P, Méhes G, Hendrik Z, Jeney V, Pethő D, Vasas A, Pálinkás Z, Balogh E, Gyetvai Á, Whiteman M, Torregrossa R, Wood ME, Olvasztó S, Nagy P, Balla G, Balla J. Hydrogen sulfide abrogates hemoglobin-lipid interaction in atherosclerotic lesion. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2018: 3812568, 2018. doi: 10.1155/2018/3812568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Shaver CM, Wickersham N, McNeil JB, Nagata H, Sills G, Kuck JL, Janz DR, Bastarache JA, Ware LB. Cell-free hemoglobin-mediated increases in vascular permeability. A novel mechanism of primary graft dysfunction and a new therapeutic target. Ann Am Thorac Soc 14: S251–S252, 2017. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201609-693MG. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Silva G, Jeney V, Chora A, Larsen R, Balla J, Soares MP. Oxidized hemoglobin is an endogenous proinflammatory agonist that targets vascular endothelial cells. J Biol Chem 284: 29582–29595, 2009. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.045344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Schaer CA, Deuel JW, Bittermann AG, Rubio IG, Schoedon G, Spahn DR, Wepf RA, Vallelian F, Schaer DJ. Mechanisms of haptoglobin protection against hemoglobin peroxidation triggered endothelial damage. Cell Death Differ 20: 1569–1579, 2013. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2013.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Belcher JD, Chen C, Nguyen J, Milbauer L, Abdulla F, Alayash AI, Smith A, Nath KA, Hebbel RP, Vercellotti GM. Heme triggers TLR4 signaling leading to endothelial cell activation and vaso-occlusion in murine sickle cell disease. Blood 123: 377–390, 2014. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-04-495887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sparkenbaugh EM, Chen C, Brzoska T, Nguyen J, Wang S, Vercellotti GM, Key NS, Sundd P, Belcher JD, Pawlinski R. Thrombin activation of PAR-1 contributes to microvascular stasis in mouse models of sickle cell disease. Blood 135: 1783–1787, 2020. doi: 10.1182/blood.2019003543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Erdei J, Toth A, Balogh E, Nyakundi BB, Banyai E, Ryffel B, Paragh G, Cordero MD, Jeney V. Induction of NLRP3 inflammasome activation by heme in human endothelial cells. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2018: 4310816, 2018. doi: 10.1155/2018/4310816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Santana SS, Pitanga TN, de Santana JM, Zanette DL, Vieira JJ, Yahouédéhou SCMA, Adanho CSA, Viana SM, Luz NF, Borges VM, Goncalves MS. Hydroxyurea scavenges free radicals and induces the expression of antioxidant genes in human cell cultures treated with hemin. Front Immunol 11: 1488–1488, 2020. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.01488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Camus SM, De Moraes JA, Bonnin P, Abbyad P, Le Jeune S, Lionnet F, Loufrani L, Grimaud L, Lambry JC, Charue D, Kiger L, Renard JM, Larroque C, Le Clésiau H, Tedgui A, Bruneval P, Barja-Fidalgo C, Alexandrou A, Tharaux PL, Boulanger CM, Blanc-Brude OP. Circulating cell membrane microparticles transfer heme to endothelial cells and trigger vasoocclusions in sickle cell disease. Blood 125: 3805–3814, 2015. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-07-589283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Balla J, Vercellotti GM, Jeney V, Yachie A, Varga Z, Jacob HS, Eaton JW, Balla G. Heme, heme oxygenase, and ferritin: how the vascular endothelium survives (and dies) in an iron-rich environment. Antioxi Redox Signal 9: 2119–2137, 2007. doi: 10.1089/ars.2007.1787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Belcher JD, Nath KA, Vercellotti GM. Vasculotoxic and proinflammatory effects of plasma heme: cell signaling and cytoprotective responses. ISRN Oxidative Med 2013: 831596, 2013. doi: 10.1155/2013/831596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Singla S, Sysol JR, Dille B, Jones N, Chen J, Machado RF. Hemin causes lung microvascular endothelial barrier dysfunction by necroptotic cell death. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 57: 307–314, 2017. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2016-0287OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.James J, Srivastava A, Valuparampil Varghese M, Eccles CA, Zemskova M, Rafikova O, Rafikov R. Heme induces rapid endothelial barrier dysfunction via the MKK3/p38MAPK axis. Blood 136: 749–754, 2020. doi: 10.1182/blood.2019003986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Vinchi F, Gastaldi S, Silengo L, Altruda F, Tolosano E. Hemopexin prevents endothelial damage and liver congestion in a mouse model of heme overload. Am J Pathol 173: 289–299, 2008. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.071130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wilson SJ, Keenan AK. Role of hemin in the modulation of H2O2-mediated endothelial cell injury. Vascul Pharmacol 40: 109–118, 2003. doi: 10.1016/s1537-1891(02)00340-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Balla G, Vercellotti GM, Eaton JW, Jacob HS. Iron loading of endothelial cells augments oxidant damage. J Lab Clin Med 116: 535–545, 1990. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Schaer DJ, Alayash AI. Clearance and control mechanisms of hemoglobin from cradle to grave. Antioxid Redox Signal 12: 181–184, 2010. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Schaer DJ, Vinchi F, Ingoglia G, Tolosano E, Buehler PW. Haptoglobin, hemopexin and related defense pathways-basic science, clinical perspectives and drug development. Front Physiol 5: 415–413, 2014. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2014.00415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Smith A, McCulloh RJ. Hemopexin and haptoglobin: allies against heme toxicity from hemoglobin not contenders. Front Physiol 6: 187, 2015. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2015.00187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Yalamanoglu A, Deuel JW, Hunt RC, Baek JH, Hassell K, Redinius K, Irwin DC, Schaer DJ, Buehler PW. Depletion of haptoglobin and hemopexin promote hemoglobin-mediated lipoprotein oxidation in sickle cell disease. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 315: L765–L774, 2018. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00269.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Willen SM, McNeil JB, Rodeghier M, Kerchberger VE, Shaver CM, Bastarache JA, Steinberg MH, DeBaun MR, Ware LB. Haptoglobin genotype predicts severe acute vaso-occlusive pain episodes in children with sickle cell anemia. Am J Hematol 95: E92–E95, 2020. doi: 10.1002/ajh.25728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Graw JA, Mayeur C, Rosales I, Liu Y, Sabbisetti VS, Riley FE, Rechester O, Malhotra R, Warren HS, Colvin RB, Bonventre JV, Bloch DB, Zapol WM. Haptoglobin or hemopexin therapy prevents acute adverse effects of resuscitation after prolonged storage of red cells. Circulation 134: 945–960, 2016. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.019955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Remy KE, Cortés-Puch I, Solomon SB, Sun J, Pockros BM, Feng J, Lertora JJ, Hantgan RR, Liu X, Perlegas A, Warren HS, Gladwin MT, Kim-Shapiro DB, Klein HG, Natanson C. Haptoglobin improves shock, lung injury, and survival in canine pneumonia. JCI insight 3: e123013, 2018. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.123013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Baek JH, D'Agnillo F, Vallelian F, Pereira CP, Williams MC, Jia Y, Schaer DJ, Buehler PW. Hemoglobin-driven pathophysiology is an in vivo consequence of the red blood cell storage lesion that can be attenuated in guinea pigs by haptoglobin therapy. J Clin Invest 122: 1444–1458, 2012. doi: 10.1172/JCI59770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Schaer CA, Deuel JW, Schildknecht D, Mahmoudi L, Garcia-Rubio I, Owczarek C, Schauer S, Kissner R, Banerjee U, Palmer AF, Spahn DR, Irwin DC, Vallelian F, Buehler PW, Schaer DJ. Haptoglobin preserves vascular nitric oxide signaling during hemolysis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 193: 1111–1122, 2016. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201510-2058OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Boretti FS, Buehler PW, D'Agnillo F, Kluge K, Glaus T, Butt OI, Jia Y, Goede J, Pereira CP, Maggiorini M, Schoedon G, Alayash AI, Schaer DJ. Sequestration of extracellular hemoglobin within a haptoglobin complex decreases its hypertensive and oxidative effects in dogs and guinea pigs. J Clin Invest 119: 2271–2280, 2009. doi: 10.1172/JCI39115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Vinchi F, Franceschi LD, Ghigo A, Townes T, Cimino J, Silengo L, Hirsch E, Altruda F, Tolosano E. Hemopexin therapy improves cardiovascular function by preventing heme-induced endothelial toxicity in mouse models of hemolytic diseases. Circulation 127: 1317–1329, 2013. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.130179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Schaer DJ, Buehler PW, Alayash AI, Belcher JD, Vercellotti GM. Hemolysis and free hemoglobin revisited: exploring hemoglobin and hemin scavengers as a novel class of therapeutic proteins. Blood 121: 1276–1284, 2013. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-11-451229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Boutaud O, Moore KP, Reeder BJ, Harry D, Howie AJ, Wang S, Carney CK, Masterson TS, Amin T, Wright DW, Wilson MT, Oates JA, Roberts LJ 2nd.. Acetaminophen inhibits hemoprotein-catalyzed lipid peroxidation and attenuates rhabdomyolysis-induced renal failure. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 2699–2704, 2010. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910174107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Janz DR, Bastarache JA, Rice TW, Bernard GR, Warren MA, Wickersham N, Sills G, Oates JA, Roberts LJ 2nd, Ware LB; Acetaminophen for the Reduction of Oxidative Injury in Severe Sepsis Study Group. Randomized, placebo-controlled trial of acetaminophen for the reduction of oxidative injury in severe sepsis: the acetaminophen for the reduction of oxidative injury in severe sepsis trial. Crit Care Med 43: 534–541, 2015. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Vallelian F, Schaer CA, Deuel JW, Ingoglia G, Humar R, Buehler PW, Schaer DJ. Revisiting the putative role of heme as a trigger of inflammation. Pharmacol Res Perspect 6: 1–15, 2018. doi: 10.1002/prp2.392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Wajih N, Basu S, Jailwala A, Kim HW, Ostrowski D, Perlegas A, Bolden CA, Buechler NL, Gladwin MT, Caudell DL, Rahbar E, Alexander-Miller MA, Vachharajani V, Kim-Shapiro DB. Potential therapeutic action of nitrite in sickle cell disease. Redox Biol 12: 1026–1039, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2017.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Sengupta P, Mahalakshmi V, Stebin JJ, Ganesh S, Suganya N, Chatterjee S. Nitric oxide donors offer protection to RBC from storage lesion. Transfus Clin Biol 27: 229–236, 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.tracli.2020.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Schmidt HM, Wood KC, Lewis SE, Hahn SA, Williams XM, McMahon B, Baust JJ, Yuan S, Bachman TN, Wang Y, Oh J-Y, Ghosh S, Ofori-Acquah SF, Lebensburger JD, Patel RP, Du J, Vitturi DA, Kelley EE, Straub AC. Xanthine oxidase drives hemolysis and vascular malfunction in sickle cell disease. Arterioscl Thromb Vasc Biol 41: 769–782, 2021. doi: 10.1161/atvbaha.120.315081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Immenschuh S, Vijayan V, Janciauskiene S, Gueler F. Heme as a target for therapeutic interventions. Front Pharmacol 8: 146, 2017. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2017.00146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Daiber A, Chlopicki S. Revisiting pharmacology of oxidative stress and endothelial dysfunction in cardiovascular disease: evidence for redox-based therapies. Free Radic Biol Med 157: 15–37, 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2020.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Kerchberger VE, Ware LB. The role of circulating cell-free hemoglobin in sepsis-associated acute kidney injury. Semin Nephrol 40: 148–159, 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2020.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Janz DR, Bastarache JA, Sills G, Wickersham N, May AK, Bernard GR, Ware LB. Association between haptoglobin, hemopexin and mortality in adults with sepsis. Crit Care 17: R272, 2013. doi: 10.1186/cc13108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Hugelshofer M, Sikorski CM, Seule M, Deuel J, Muroi CI, Seboek M, Akeret K, Buzzi R, Regli L, Schaer DJ, Keller E. Cell-free oxyhemoglobin in cerebrospinal fluid after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: biomarker and potential therapeutic target. World Neurosurg 120: e660–e666, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2018.08.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Anderson UD, Jälmby M, Faas MM, Hansson SR. The hemoglobin degradation pathway in patients with preeclampsia—fetal hemoglobin, heme, heme oxygenase-1 and hemopexin—potential diagnostic biomarkers? Pregnancy Hypertens 14: 273–278, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.preghy.2018.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Kim-Campbell N, Gretchen C, Callaway C, Felmet K, Kochanek PM, Maul T, Wearden P, Sharma M, Viegas M, Munoz R, Gladwin MT, Bayir H. Cell-free plasma hemoglobin and male gender are risk factors for acute kidney injury in low risk children undergoing cardiopulmonary bypass. Crit Care Med 45: e1123–e1130, 2017. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]