| Atualização da Diretriz Brasileira de Hipercolesterolemia Familiar – 2021 | |

|---|---|

| O relatório abaixo lista as declarações de interesse conforme relatadas à SBC pelos especialistas durante o período de desenvolvimento deste posicionamento, 2020/2021. | |

| Especialista | Tipo de relacionamento com a indústria |

| Adriana Bertolami | Nada a ser declarado |

| Ana Maria Lottenberg | Declaração financeira |

| Nada a ser declarado | |

| Ana Paula M. Chacra | Nada a ser declarado |

| Andre Arpad Faludi | Nada a ser declarado |

| Andrei C. Sposito | Outros relacionamentos |

| Financiamento de atividades de educação médica continuada, incluindo viagens, hospedagens e inscrições para congressos e cursos, provenientes da indústria farmacêutica, de órteses, próteses, equipamentos e implantes, brasileiras ou estrangeiras: | |

| - Sanofi: Aula médica. | |

| Antônio Carlos Palandri Chagas | Declaração financeira |

| A - Pagamento de qualquer espécie e desde que economicamente apreciáveis, feitos a (i) você, (ii) ao seu cônjuge/ companheiro ou a qualquer outro membro que resida com você, (iii) a qualquer pessoa jurídica em que qualquer destes seja controlador, sócio, acionista ou participante, de forma direta ou indireta, recebimento por palestras, aulas, atuação como proctor de treinamentos, remunerações, honorários pagos por participações em conselhos consultivos, de investigadores, ou outros comitês, etc. Provenientes da indústria farmacêutica, de órteses, próteses, equipamentos e implantes, brasileiras ou estrangeiras: | |

| - Instituto de Vita: Membro do conselho científico; Novo Nordisk: Diabetes/obesidade; Pfizer/ Upjohn: Hipolipemiante. | |

| Cinthia Elim Jannes | Nada a ser declarado |

| Cristiane Kovacs Amaral | Nada a ser declarado |

| Daniel Branco de Araújo | Declaração financeira |

| A - Pagamento de qualquer espécie e desde que economicamente apreciáveis, feitos a (i) você, (ii) ao seu cônjuge/ companheiro ou a qualquer outro membro que resida com você, (iii) a qualquer pessoa jurídica em que qualquer destes seja controlador, sócio, acionista ou participante, de forma direta ou indireta, recebimento por palestras, aulas, atuação como proctor de treinamentos, remunerações, honorários pagos por participações em conselhos consultivos, de investigadores, ou outros comitês, etc. Provenientes da indústria farmacêutica, de órteses, próteses, equipamentos e implantes, brasileiras ou estrangeiras: | |

| - Novo Nordisk/ Merk do Brasil: Diabetes; Novartis: Dislipidemia. | |

| Outros relacionamentos | |

| Financiamento de atividades de educação médica continuada, incluindo viagens, hospedagens e inscrições para congressos e cursos, provenientes da indústria farmacêutica, de órteses, próteses, equipamentos e implantes, brasileiras ou estrangeiras: | |

| - Sanofi: Dislipidemia. | |

| Dennys Esper Cintra | Nada a ser declarado |

| Elaine dos Reis Coutinho | Declaração financeira |

| A - Pagamento de qualquer espécie e desde que economicamente apreciáveis, feitos a (i) você, (ii) ao seu cônjuge/ companheiro ou a qualquer outro membro que resida com você, (iii) a qualquer pessoa jurídica em que qualquer destes seja controlador, sócio, acionista ou participante, de forma direta ou indireta, recebimento por palestras, aulas, atuação como proctor de treinamentos, remunerações, honorários pagos por participações em conselhos consultivos, de investigadores, ou outros comitês, etc. Provenientes da indústria farmacêutica, de órteses, próteses, equipamentos e implantes, brasileiras ou estrangeiras: | |

| - Novartis: Atividade não promocional. | |

| Fernando Cesena | Declaração financeira |

| A - Pagamento de qualquer espécie e desde que economicamente apreciáveis, feitos a (i) você, (ii) ao seu cônjuge/ companheiro ou a qualquer outro membro que resida com você, (iii) a qualquer pessoa jurídica em que qualquer destes seja controlador, sócio, acionista ou participante, de forma direta ou indireta, recebimento por palestras, aulas, atuação como proctor de treinamentos, remunerações, honorários pagos por participações em conselhos consultivos, de investigadores, ou outros comitês, etc. Provenientes da indústria farmacêutica, de órteses, próteses, equipamentos e implantes, brasileiras ou estrangeiras: | |

| - Libbs/ Novartis: Dislipidemia; Abbott/ Novo Nordisk: Diabetes; Pfizer: Anticoagulação. | |

| Outros relacionamentos | |

| Financiamento de atividades de educação médica continuada, incluindo viagens, hospedagens e inscrições para congressos e cursos, provenientes da indústria farmacêutica, de órteses, próteses, equipamentos e implantes, brasileiras ou estrangeiras: | |

| - Novartis; Novo Nordisk: Diabetes. | |

| Francisco Antonio Helfenstein Fonseca | Declaração financeira |

| A - Pagamento de qualquer espécie e desde que economicamente apreciáveis, feitos a (i) você, (ii) ao seu cônjuge/ companheiro ou a qualquer outro membro que resida com você, (iii) a qualquer pessoa jurídica em que qualquer destes seja controlador, sócio, acionista ou participante, de forma direta ou indireta, recebimento por palestras, aulas, atuação como proctor de treinamentos, remunerações, honorários pagos por participações em conselhos consultivos, de investigadores, ou outros comitês, etc. Provenientes da indústria farmacêutica, de órteses, próteses, equipamentos e implantes, brasileiras ou estrangeiras: | |

| - Novo Nordisk: Semaglutida; AstraZeneca: Rosuvastatina, Metoprolol, Candesartana; Libbs: Rosuvastatina, Ezetimiba; Sanofi. | |

| Outros relacionamentos | |

| Financiamento de atividades de educação médica continuada, incluindo viagens, hospedagens e inscrições para congressos e cursos, provenientes da indústria farmacêutica, de órteses, próteses, equipamentos e implantes, brasileiras ou estrangeiras: | |

| - AstraZeneca/ Novo Nordisk: Congresso virtual. | |

| Hermes Toros Xavier | Declaração financeira |

| A - Pagamento de qualquer espécie e desde que economicamente apreciáveis, feitos a (i) você, (ii) ao seu cônjuge/ companheiro ou a qualquer outro membro que resida com você, (iii) a qualquer pessoa jurídica em que qualquer destes seja controlador, sócio, acionista ou participante, de forma direta ou indireta, recebimento por palestras, aulas, atuação como proctor de treinamentos, remunerações, honorários pagos por participações em conselhos consultivos, de investigadores, ou outros comitês, etc. Provenientes da indústria farmacêutica, de órteses, próteses, equipamentos e implantes, brasileiras ou estrangeiras: | |

| - Torrent do Brasil: Colesterol; Bayer: Aterotrombose. | |

| Outros relacionamentos | |

| Financiamento de atividades de educação médica continuada, incluindo viagens, hospedagens e inscrições para congressos e cursos, provenientes da indústria farmacêutica, de órteses, próteses, equipamentos e implantes, brasileiras ou estrangeiras: | |

| - Torrent do Brasil: Colesterol. | |

| Isabela Cardoso Pimentel Mota | Declaração financeira |

| A - Pagamento de qualquer espécie e desde que economicamente apreciáveis, feitos a (i) você, (ii) ao seu cônjuge/ companheiro ou a qualquer outro membro que resida com você, (iii) a qualquer pessoa jurídica em que qualquer destes seja controlador, sócio, acionista ou participante, de forma direta ou indireta, recebimento por palestras, aulas, atuação como proctor de treinamentos, remunerações, honorários pagos por participações em conselhos consultivos, de investigadores, ou outros comitês, etc. Provenientes da indústria farmacêutica, de órteses, próteses, equipamentos e implantes, brasileiras ou estrangeiras: | |

| - PTC Therapheutics: Doenças raras. | |

| Isabela de Carlos Back Giuliano | Declaração financeira |

| B - Financiamento de pesquisas sob sua responsabilidade direta/pessoal (direcionado ao departamento ou instituição) provenientes da indústria farmacêutica, de órteses, próteses, equipamentos e implantes, brasileiras ou estrangeiras: | |

| - Genzyme do Brasil: Mipomersen. | |

| José Francisco Kerr Saraiva | Nada a ser declarado |

| José Rocha Faria Neto | Declaração financeira |

| A - Pagamento de qualquer espécie e desde que economicamente apreciáveis, feitos a (i) você, (ii) ao seu cônjuge/ companheiro ou a qualquer outro membro que resida com você, (iii) a qualquer pessoa jurídica em que qualquer destes seja controlador, sócio, acionista ou participante, de forma direta ou indireta, recebimento por palestras, aulas, atuação como proctor de treinamentos, remunerações, honorários pagos por participações em conselhos consultivos, de investigadores, ou outros comitês, etc. Provenientes da indústria farmacêutica, de órteses, próteses, equipamentos e implantes, brasileiras ou estrangeiras: | |

| - AstraZeneca: Diabetes; Boehringer Ingelheim: Diabetes, Fibrilação atrial; Sanofi/ Medley: Dislipidemia; Novartis. | |

| Outros relacionamentos | |

| Financiamento de atividades de educação médica continuada, incluindo viagens, hospedagens e inscrições para congressos e cursos, provenientes da indústria farmacêutica, de órteses, próteses, equipamentos e implantes, brasileiras ou estrangeiras: | |

| - Sanofi/ Medley: Dislipidemia. | |

| Juliana Tieko Kato | Nada a ser declarado |

| Luciana Ribeiro Bahia | Declaração financeira |

| A - Pagamento de qualquer espécie e desde que economicamente apreciáveis, feitos a (i) você, (ii) ao seu cônjuge/ companheiro ou a qualquer outro membro que resida com você, (iii) a qualquer pessoa jurídica em que qualquer destes seja controlador, sócio, acionista ou participante, de forma direta ou indireta, recebimento por palestras, aulas, atuação como proctor de treinamentos, remunerações, honorários pagos por participações em conselhos consultivos, de investigadores, ou outros comitês, etc. Provenientes da indústria farmacêutica, de órteses, próteses, equipamentos e implantes, brasileiras ou estrangeiras: | |

| - Novo Nordisk: Obesidade; AstraZeneca: Diabetes. | |

| Outros relacionamentos | |

| Financiamento de atividades de educação médica continuada, incluindo viagens, hospedagens e inscrições para congressos e cursos, provenientes da indústria farmacêutica, de órteses, próteses, equipamentos e implantes, brasileiras ou estrangeiras: | |

| - Novo Nordisk: Obesidade. | |

| Marcelo Chiara Bertolami | Declaração financeira |

| A - Pagamento de qualquer espécie e desde que economicamente apreciáveis, feitos a (i) você, (ii) ao seu cônjuge/ companheiro ou a qualquer outro membro que resida com você, (iii) a qualquer pessoa jurídica em que qualquer destes seja controlador, sócio, acionista ou participante, de forma direta ou indireta, recebimento por palestras, aulas, atuação como proctor de treinamentos, remunerações, honorários pagos por participações em conselhos consultivos, de investigadores, ou outros comitês, etc. Provenientes da indústria farmacêutica, de órteses, próteses, equipamentos e implantes, brasileiras ou estrangeiras: | |

| - Abbott: Lipidil; Sanofi: Zinpass e Zinpass eze, Libbs: Plenance eze. | |

| Outros relacionamentos | |

| Financiamento de atividades de educação médica continuada, incluindo viagens, hospedagens e inscrições para congressos e cursos, provenientes da indústria farmacêutica, de órteses, próteses, equipamentos e implantes, brasileiras ou estrangeiras: | |

| - Novo Nordisk: Ozempic; EMS: Hipolipemiantes; Aché: Trezate. | |

| Marcelo Heitor Vieira Assad | Declaração financeira |

| A - Pagamento de qualquer espécie e desde que economicamente apreciáveis, feitos a (i) você, (ii) ao seu cônjuge/ companheiro ou a qualquer outro membro que resida com você, (iii) a qualquer pessoa jurídica em que qualquer destes seja controlador, sócio, acionista ou participante, de forma direta ou indireta, recebimento por palestras, aulas, atuação como proctor de treinamentos, remunerações, honorários pagos por participações em conselhos consultivos, de investigadores, ou outros comitês, etc. Provenientes da indústria farmacêutica, de órteses, próteses, equipamentos e implantes, brasileiras ou estrangeiras: | |

| - AstraZeneca: Prevenção cardiovascular; Boehringerr: Diabetes/anticoagulação; Novo Nordisk: Diabetes. | |

| Outros relacionamentos | |

| Financiamento de atividades de educação médica continuada, incluindo viagens, hospedagens e inscrições para congressos e cursos, provenientes da indústria farmacêutica, de órteses, próteses, equipamentos e implantes, brasileiras ou estrangeiras: | |

| - Boehringer; Novo Nordisk: Diabetes | |

| Marcio Hiroshi Miname | Declaração financeira |

| A - Pagamento de qualquer espécie e desde que economicamente apreciáveis, feitos a (i) você, (ii) ao seu cônjuge/ companheiro ou a qualquer outro membro que resida com você, (iii) a qualquer pessoa jurídica em que qualquer destes seja controlador, sócio, acionista ou participante, de forma direta ou indireta, recebimento por palestras, aulas, atuação como proctor de treinamentos, remunerações, honorários pagos por participações em conselhos consultivos, de investigadores, ou outros comitês, etc. Provenientes da indústria farmacêutica, de órteses, próteses, equipamentos e implantes, brasileiras ou estrangeiras: | |

| - Amgen: Repatha; Novo Nordisk: Ozempic; Libbs. | |

| B - Financiamento de pesquisas sob sua responsabilidade direta/pessoal (direcionado ao departamento ou instituição) provenientes da indústria farmacêutica, de órteses, próteses, equipamentos e implantes, brasileiras ou estrangeiras: | |

| - Kowa: Pemafibrato. | |

| Outros relacionamentos | |

| Financiamento de atividades de educação médica continuada, incluindo viagens, hospedagens e inscrições para congressos e cursos, provenientes da indústria farmacêutica, de órteses, próteses, equipamentos e implantes, brasileiras ou estrangeiras: | |

| - Novo Nordisk: Ozempic. | |

| Maria Cristina de Oliveira Izar | Declaração financeira |

| A - Pagamento de qualquer espécie e desde que economicamente apreciáveis, feitos a (i) você, (ii) ao seu cônjuge/ companheiro ou a qualquer outro membro que resida com você, (iii) a qualquer pessoa jurídica em que qualquer destes seja controlador, sócio, acionista ou participante, de forma direta ou indireta, recebimento por palestras, aulas, atuação como proctor de treinamentos, remunerações, honorários pagos por participações em conselhos consultivos, de investigadores, ou outros comitês, etc. Provenientes da indústria farmacêutica, de órteses, próteses, equipamentos e implantes, brasileiras ou estrangeiras: | |

| - Amgen: Evolocumabe; Amryt: Lomitapide; Aché: Rosuvastatina, Ezetimiba; Libbs. | |

| B - Financiamento de pesquisas sob sua responsabilidade direta/pessoal (direcionado ao departamento ou instituição) provenientes da indústria farmacêutica, de órteses, próteses, equipamentos e implantes, brasileiras ou estrangeiras: | |

| - Novartis; PTC Bio; Amgen: Dislipidemia. | |

| C - Financiamento de pesquisa (pessoal), cujas receitas tenham sido provenientes da indústria farmacêutica, de órteses, próteses, equipamentos e implantes, brasileiras ou estrangeiras: | |

| - PTC Bio; Amgen: Dislipidemia. | |

| Maria Helane Costa Gurgel Castelo | Declaração financeira |

| A - Pagamento de qualquer espécie e desde que economicamente apreciáveis, feitos a (i) você, (ii) ao seu cônjuge/ companheiro ou a qualquer outro membro que resida com você, (iii) a qualquer pessoa jurídica em que qualquer destes seja controlador, sócio, acionista ou participante, de forma direta ou indireta, recebimento por palestras, aulas, atuação como proctor de treinamentos, remunerações, honorários pagos por participações em conselhos consultivos, de investigadores, ou outros comitês, etc. Provenientes da indústria farmacêutica, de órteses, próteses, equipamentos e implantes, brasileiras ou estrangeiras: | |

| - PTC: Palestra e Advisory board sobre SQF; Amgen: Estuco clinico nos últimos 2 anos - Houser; | |

| B - Financiamento de pesquisas sob sua responsabilidade direta/pessoal (direcionado ao departamento ou instituição) provenientes da indústria farmacêutica, de órteses, próteses, equipamentos e implantes, brasileiras ou estrangeiras: | |

| - Amgen: Estudo Houser; Novertis: Estudo Orion. | |

| Maria Sílvia Ferrari Lavrador | Nada a ser declarado |

| Patrícia Guedes de Souza | Nada a ser declarado |

| Raul Dias dos Santos Filho | Declaração financeira |

| A - Pagamento de qualquer espécie e desde que economicamente apreciáveis, feitos a (i) você, (ii) ao seu cônjuge/ companheiro ou a qualquer outro membro que resida com você, (iii) a qualquer pessoa jurídica em que qualquer destes seja controlador, sócio, acionista ou participante, de forma direta ou indireta, recebimento por palestras, aulas, atuação como proctor de treinamentos, remunerações, honorários pagos por participações em conselhos consultivos, de investigadores, ou outros comitês, etc. Provenientes da indústria farmacêutica, de órteses, próteses, equipamentos e implantes, brasileiras ou estrangeiras: | |

| - Abbott; Amgen: Dislipidemia; AstraZeneca: Diabetes; EMS; GETZ Pharma; Kowa; Merck; MSD; Novo Nordisk; Novartis; PTC; Pfizer; Hypera; Sanofi. | |

| B - Financiamento de pesquisas sob sua responsabilidade direta/pessoal (direcionado ao departamento ou instituição) provenientes da indústria farmacêutica, de órteses, próteses, equipamentos e implantes, brasileiras ou estrangeiras: | |

| - Amgen, Sanofi; Esperion: Dislipidemia; Kowa. | |

| Renato Jorge Alves | Declaração financeira |

| A - Pagamento de qualquer espécie e desde que economicamente apreciáveis, feitos a (i) você, (ii) ao seu cônjuge/ companheiro ou a qualquer outro membro que resida com você, (iii) a qualquer pessoa jurídica em que qualquer destes seja controlador, sócio, acionista ou participante, de forma direta ou indireta, recebimento por palestras, aulas, atuação como proctor de treinamentos, remunerações, honorários pagos por participações em conselhos consultivos, de investigadores, ou outros comitês, etc. Provenientes da indústria farmacêutica, de órteses, próteses, equipamentos e implantes, brasileiras ou estrangeiras: | |

| - Amgen: Evolocumabe; PTC: Volanesorsen; Pfizer: Apixaban. | |

| Roberta Marcondes Machado | Declaração financeira |

| Nada a ser declarado | |

| Outros relacionamentos | |

| Financiamento de atividades de educação médica continuada, incluindo viagens, hospedagens e inscrições para congressos e cursos, provenientes da indústria farmacêutica, de órteses, próteses, equipamentos e implantes, brasileiras ou estrangeiras: | |

| - PTC: Nutricionista. | |

| Tania L. R. Martinez | Nada a ser declarado |

| Valeria Arruda Machado | Nada a ser declarado |

| Viviane Zorzanelli Rocha Giraldez | Declaração financeira |

| A - Pagamento de qualquer espécie e desde que economicamente apreciáveis, feitos a (i) você, (ii) ao seu cônjuge/ companheiro ou a qualquer outro membro que resida com você, (iii) a qualquer pessoa jurídica em que qualquer destes seja controlador, sócio, acionista ou participante, de forma direta ou indireta, recebimento por palestras, aulas, atuação como proctor de treinamentos, remunerações, honorários pagos por participações em conselhos consultivos, de investigadores, ou outros comitês, etc. Provenientes da indústria farmacêutica, de órteses, próteses, equipamentos e implantes, brasileiras ou estrangeiras: | |

| - Novo Nordisk: Agonistas de receptor de GLP1; AstraZeneca: Dapagliflozina; Amgen: Inibidores de PCSK9. | |

| Outros relacionamentos | |

| Financiamento de atividades de educação médica continuada, incluindo viagens, hospedagens e inscrições para congressos e cursos, provenientes da indústria farmacêutica, de órteses, próteses, equipamentos e implantes, brasileiras ou estrangeiras: | |

| - Novo Nordisk: Agonistas de receptor de GLP1. | |

| Wilson Salgado Filho | Nada a ser declarado |

Definição de graus de recomendação e níveis de evidência

Classes (graus) de recomendação:

Classe I – Condições para as quais há evidências conclusivas, ou, na sua falta, consenso de que o procedimento é seguro e útil/eficaz.

Classe II – Condições para as quais há evidências conflitantes e/ou divergência de opinião sobre segurança e utilidade/eficácia do procedimento.

Classe IIA – Peso ou evidência/opinião a favor do procedimento. A maioria aprova.

Classe IIB – Segurança e utilidade/eficácia menos bem estabelecida, não havendo predomínio de opiniões a favor.

Classe III – Condições para as quais há evidências e/ou consenso de que o procedimento não é útil/eficaz e, em alguns casos, pode ser prejudicial.

Níveis de evidência:

Nível A – Dados obtidos a partir de múltiplos estudos randomizados de bom porte, concordantes, e/ou de meta-análise robusta de estudos clínicos randomizados.

Nível B – Dados obtidos a partir de meta-análise menos robusta, de um único estudo randomizado ou de estudos não randomizados (observacionais).

Nível C – Dados obtidos de opiniões consensuais de especialistas.

Introdução

A hipercolesterolemia familiar (HF) é uma causa genética comum de doença coronariana prematura, especialmente de infarto do miocárdio, devido à exposição ao longo da vida a concentrações elevadas de colesterol da lipoproteína de baixa densidade (LDL-c). Caracteriza-se por ser uma forma grave de dislipidemia de base genética, em que aproximadamente 85% dos homens e 50% das mulheres podem ter um evento coronariano antes de completar os 65 anos de idade, se não tratados adequadamente.

A HF é considerada um problema de saúde pública, devido à sua alta prevalência (em torno de 1:200 a 1:300 indivíduos da população geral) e à sua associação com doença arterial coronariana (DAC) precoce, com redução da expectativa de vida observada em várias famílias. Além disso, cerca de 200.000 pessoas no mundo vão a óbito a cada ano por ataques cardíacos precoces devido à doença, os quais poderiam ser evitados com tratamentos apropriados. Se a HF não for tratada, homens e mulheres com a forma heterozigótica desenvolverão DAC antes dos 55 e 60 anos, respectivamente. Já os homozigotos comumente desenvolvem DAC muito cedo na vida e, se não tratados, podem morrer antes dos 20 anos de idade. No entanto, quando o diagnóstico é feito e o tratamento é instituído, pode-se modificar a história natural da doença aterosclerótica.

O diagnóstico precoce é fundamental, pois torna possível o início antecipado da medicação hipolipemiante e a mudança na história natural da doença, devendo ser guiado por diretrizes e podendo ser facilitado pelo uso de algoritmos. A identificação dos casos de maior gravidade e o cuidado integrado são estratégias para minimizar o impacto da HF na doença cardiovascular. A abordagem diagnóstica, as medidas nutricionais e o emprego de fármacos potentes, como o tratamento com estatinas de alta intensidade, a combinação de medicamentos e o uso de novos agentes hipolipemiantes, podem modificar a história natural da doença nesses indivíduos.

É importante também o reconhecimento da HF como condição genética autossômica dominante, pois o rastreamento em cascata de familiares de indivíduos afetados é imperativo, uma medida custo-efetiva e que propicia o reconhecimento precoce e a instituição de terapêutica que vise retardar ou impedir o aparecimento da doença aterosclerótica. Atenção especial a crianças e adolescentes, gestantes e HF grave são assuntos abordados nesta diretriz.

O Departamento de Aterosclerose e os maiores especialistas do país reuniram-se com o objetivo de transmitir as melhores informações disponíveis para melhoria da prática clínica no Brasil, de forma clara e objetiva, para a prevenção e o tratamento da doença aterosclerótica cardiovascular prematura e para tranquilizar famílias afetadas por essa condição.

Sinceramente,

Profa. Dra. Maria Cristina de Oliveira Izar, MD, PhD

1. História Natural da Hipercolesterolemia Familiar

1.1. Definição

A HF é uma doença genética do metabolismo das lipoproteínas, cujo modo de herança é autossômico codominante. Caracteriza-se por níveis muito elevados do LDL-c e pela presença de sinais clínicos específicos, como xantomas tendíneos, arco corneal e doença aterosclerótica cardiovascular (DASCV) antes dos 45 anos. 1,2

As primeiras observações sobre a doença foram feitas pelo patologista Harbitz em meados do século XVIII, quando relatou casos de morte súbita em portadores de xantomas. E em 1938, Müller 3 descreveu a HF como uma entidade clínica e observou que a associação de hipercolesterolemia, xantomas e manifestações de DAC eram achados comuns em algumas famílias e herdados como um traço dominante. Cerca de 50 anos mais tarde, Brown e Goldstein, 4-6 ao estudarem pacientes e culturas de células, elucidaram a complexa via da síntese endógena do colesterol e identificaram o defeito na internalização da lipoproteína de baixa densidade (LDL, do inglês, low density lipoprotein ) ligada ao seu receptor. Em 1983, esse gene foi clonado e mapeado no braço curto do cromossomo 19, 7 sendo então denominado gene do receptor da LDL, ou gene LDLR , em 1989. 8

A HF tinha uma prevalência “histórica” estimada de 1:500 indivíduos afetados na forma heterozigótica e de 1:1.000.000 na forma homozigótica. 9,10 Khachadurian 10 foi quem discriminou essas duas manifestações da HF. No entanto, estudos mais recentes sugerem que a prevalência da doença seja maior, 1:200 a 1:300 na HF heterozigótica (HFHe) e 1:160.000 a 1:300.000 na HF homozigótica (HFHo), com base em critérios clínicos e moleculares. 11,12

As concentrações plasmáticas de LDL-c nos indivíduos com HFHe são, em geral, duas a três vezes maiores do que em pessoas sem a doença, e os portadores da afecção apresentam maior probabilidade de desenvolver DASCV prematura na segunda ou terceira décadas de vida. Já aqueles com HFHo têm concentrações de LDL-c cerca de seis a oito vezes maiores e desenvolvem DASCV muito cedo em sua vida, frequentemente morrendo até a idade de 20 anos, se não tratados. 9,13

O fenótipo clínico de HF é geralmente decorrente de defeitos no gene LDLR , que codifica o LDLR, 5,10 sede de mais de 2.251 mutações descritas até o momento. 14 Mutações pontuais, ou por substituição de uma única base (polimorfismo de nucleotídeo único [SNP, do inglês, single nucleotide polymorphism ]), são responsáveis por mais de 84% das mutações, enquanto rearranjos maiores ocorrem em 16% de todas as mutações descritas no gene LDLR .

O fenótipo clínico da HF pode também ser secundário a defeitos no gene APOB, que codifica a apolipoproteína B-100 (Apo B-100) 15 – quando defeituosa, apresenta menor afinidade pelo LDLR –, ou ainda quando existe catabolismo acelerado do LDLR devido a mutações com ganho de função no gene proproteína convertase subutilisina/kexina tipo 9 ( PCSK9 ), que codifica a proteína NARC-1, 16 a qual participa do catabolismo do LDLR.

Na maioria dos casos, a HF é causada por mutações em genes que codificam proteínas envolvidas na captação e no catabolismo do LDLR. Os genes LDLR , apolipoproteína-B ( APOB ) e PCSK9 são considerados genes ligados ao desenvolvimento de HF, resultando na homeostase defeituosa das partículas de LDL e, consequentemente, na elevação das concentrações plasmáticas de LDL-c. Desse modo, frequentemente, pacientes com diagnóstico molecular de HF apresentam variantes patogênicas no gene LDLR, 17 enquanto as mutações dos genes APOB e PCSK9 respondem por menor percentual da HF na forma autossômica dominante (ADH). 18 A HF autossômica recessiva (ARH), por outro lado, é uma forma rara e ocorre quando os indivíduos herdam mutações patogênicas em ambas as cópias do gene low-density lipoprotein adaptor protein 1 ( LDLRAP1 ), que codifica a proteína adaptadora do receptor de LDL. 19 No entanto, sabe-se ainda que a HF pode ser decorrente de variantes patogênicas em genes não conhecidos, ou mesmo de vários genes, sendo conhecida como HF poligênica. 20

O fenótipo clínico é muito semelhante entre as formas mais comuns de HF; porém, os defeitos do gene APOB são mais comuns entre algumas populações europeias (1:300 a 1:700 na Europa Central), enquanto mutações do gene PCSK9 não têm uma frequência estabelecida (em geral, ~1%). A HF apresenta penetração elevada; 20-22 assim, a maioria dos portadores de mutações causais para a doença apresentam o fenótipo clínico. Pelo seu modo de herança autossômico codominante, a metade dos descendentes em primeiro grau de um indivíduo afetado serão portadores do defeito genético e apresentarão níveis elevados de LDL-c desde o nascimento e ao longo de sua vida, sendo homens e mulheres igualmente afetados. 9,22

Os heterozigotos possuem metade dos receptores de LDL funcionantes, enquanto, nos homozigotos, por defeito no LDLR , ambos os receptores têm perda de função ou função nula 23 . A importância do diagnóstico genético reside no fato de que os critérios clínicos/laboratoriais muitas vezes não são conhecidos pelos pacientes, dificultando a confirmação diagnóstica.

De acordo com normatização recente, 23 a HF inclui múltiplos fenótipos, devido a diferentes etiologias moleculares e fatores genéticos adicionais. Os níveis de LDL-c, o número de mutações e fatores adicionais protetores ou patogênicos determinam o risco de DAC; portanto, indivíduos sob risco pela história familiar, bem como aqueles com fenótipo de HF, devem ser genotipados. Os resultados desse teste podem fornecer três categorias de indivíduos:

Genótipo positivo, fenótipo negativo

Genótipo positivo, fenótipo positivo

Genótipo negativo, fenótipo positivo.

Em alguns casos, outras etiologias moleculares devem ser pesquisadas, 23 como mutações no gene apo (a) , LIPA , que codifica a lipase ácida lisossomal, além da forma poligênica. O risco de DAC é maior em portadores de mutações patogênicas, se comparado àqueles sem mutações para qualquer valor de LDL-c. Acima de 190 mg/dl, o risco de DAC chega a ser mais de 3 vezes maior para um mesmo nível de LDL-c nos portadores de mutações causais, comparado aos não portadores de mutações; isso provavelmente em função da exposição ao longo da vida a níveis muito elevados de LDL-c. 24

A HF é considerada um problema de saúde pública devido à elevada prevalência de doença coronariana precoce e à redução da expectativa de vida observada em várias famílias. Aproximadamente 85% dos homens e 50% das mulheres podem ter um evento coronariano antes de completarem os 65 anos de idade, se não tratados adequadamente. Estudos revelam que cerca de 200.000 pessoas no mundo vão a óbito a cada ano por ataques cardíacos precoces devido à HF, os quais poderiam ser evitados com tratamentos apropriados. 20

1.2. Epidemiologia da Doença Aterosclerótica Cardiovascular

A DASCV e suas complicações no Brasil e no mundo são um grave problema de saúde pública. Segundo dados fornecidos pelo Departamento de Informática do Sistema Único de Saúde (DATASUS), as doenças cardiovasculares (DCV) são a principal causa de morte no país, com aproximadamente 27,65% do total de óbitos. 25 Analisando-se a mortalidade específica por doenças do aparelho circulatório, as afecções isquêmicas do coração são responsáveis por 32% das mortes. 25 Dados publicados em 2016 por Ribeiro et al. 26 mostram que o sistema público financiou 940.323 hospitalizações para DCV em 2012. No período de 2008 a 2012, as taxas de internações por insuficiência cardíaca congestiva e hipertensão arterial foram reduzidas, enquanto aquelas motivadas por angioplastia e infarto agudo do miocárdio (IAM) aumentaram. 26

No mundo, dentre as dez principais causas de morte, estão as doenças isquêmicas do coração e o acidente vascular encefálico (AVE), que ocupam o primeiro e segundo lugares, respectivamente, e juntos são responsáveis por mais de 15,2 milhões de óbitos. Essas afecções permanecem líderes globais de morte nos últimos 15 anos. 27 Em estudo realizado nos Estados Unidos de 1989 a 1998, 51% das mulheres e 41% dos homens com morte súbita cardíaca faleceram antes do primeiro contato médico. As síndromes coronarianas agudas foram responsáveis por 27% dessas mortes. 28

A maioria dos óbitos por IAM ocorre nas primeiras horas de manifestação da doença, sendo 40 a 65% na primeira hora e aproximadamente 80% nas primeiras 24 horas. 29 Entre os sobreviventes, 19% em média evoluem com insuficiência cardíaca, importante causa de internações e morbidade. 30,31

Embora conhecidos fatores de risco cardiovascular sejam responsáveis pela maioria dos casos de DASCV e suas complicações, 32-36 existem condições clínicas que aumentam o risco e antecipam sua ocorrência, como a HF. 37-40

1.3. Aspectos Epidemiológicos da Hipercolesterolemia Familiar no Mundo e no Brasil

A HF tem uma prevalência dita histórica de 1:500 na população geral. 22 No entanto, atualmente, sabe-se que, com base nos dados do Copenhagen General Population Study , a prevalência estimada da doença é de 1:223 por critérios clínicos 37 e de 1:217 utilizando teste genético. 38 Um relato do governo da Dinamarca concluiu que, com uma prevalência de 1:200 a 250, apenas 11 a 13% dos portadores de HFHe seriam identificados (a falha no diagnóstico é particularmente importante nas crianças).

Na forma homozigótica, estimava-se sua prevalência em 1:1.000.000 de indivíduos; porém, hoje se sabe que ela pode acometer 1 em cada 300.000 pessoas, podendo ser maior (1:160.000) quando há um efeito “fundador”. Isso significa que a HFHo pode ser mais prevalente em algumas populações, como os sul-africanos (1:100.000), libaneses (1:170.000), franco-canadenses (1:270.000) e finlandeses, devido à presença de casamentos consanguíneos. 13,14

Assim, dada a estimativa do estudo dinamarquês, uma prevalência de HFHe de 1:220 se traduz em uma frequência alélica de 1:440, assumindo-se uma frequência de HFHo de 1:193.600 casos. Com base nessas estimativas, são preditos cerca de 28 casos de HFHo na Dinamarca; porém, na verdade, bem poucos são reconhecidos, 38,39 e na maioria dos países, a entidade permanece não diagnosticada (menos de 1% no Brasil). 14 Estima-se que no mundo todo existam mais de 34.000.000 indivíduos portadores de HF. 9,14 No entanto, menos de 10% tem diagnóstico conhecido, e menos de 25% recebe tratamento hipolipemiante. 38 Assumindo-se a mesma prevalência no Brasil, o país deve ter cerca de 1.033 casos de HFHo.

Não existem dados objetivos sobre a prevalência da HF no Brasil. Com base nos dados clínicos e laboratoriais e na história familiar, obtidos a partir do estudo ELSA-Brasil, da população adulta das instituições participantes, e adotando-se os critérios da Dutch Lipid Clinic Network (DLCN), há uma estimativa de casos de HF de 1:263, o que corresponde a uma população afetada de 766.000 indivíduos no Brasil. 41 Essa prevalência ainda varia com o gênero (0,38% em mulheres e 0,30% em homens), a raça (0,25% em brancos, 0,47% em etnia mista e 0,67% em negros) e com a idade (0,10% de 35 a 45 anos; 0,42% de 46 a 55 anos; 0,60% de 56 a 65 anos; e 0,26% de 66 a 75 anos). 41 Recentemente, dados de meta-análise, demonstraram a prevalência global da HF na população geral de 1:311, sendo 18 vezes maior entre os indivíduos com doença cardiovascular aterosclerótica. 42 Outra meta-análise evidenciou maior prevalência da HF naqueles com doença isquêmica do coração, doença cardíaca isquêmica prematura e hipercolesterolemia grave, em 10, 20 e 23 vezes, respectivamente. 43

1.4. Impacto da Hipercolesterolemia Familiar na Doença Aterosclerótica Cardiovascular

A HF é uma causa genética comum de doença coronariana prematura, especialmente de infarto do miocárdio (IAM) e angina pectoris , devido à exposição a concentrações elevadas de LDL-c ao longo da vida. 44,45 Se não for tratada, homens e mulheres com HFHe e colesterol total de 310 a 580 mg/dl desenvolverão DAC antes dos 55 e 60 anos, respectivamente. Os homozigotos com colesterol total entre 460 a 1.160 mg/dl geralmente desenvolvem DAC muito cedo na vida e, se não tratados, podem morrer antes dos 20 anos de idade. No entanto, quando o diagnóstico é feito e o tratamento é instituído, pode-se modificar a história natural da doença aterosclerótica. 46

Embora não existam dados a respeito do risco de DASCV ou da taxa de tratamento hipolipemiante na HF, em uma grande amostra da população geral de Copenhage, na Dinamarca, a prevalência de DAC entre aqueles com diagnóstico provável ou certeza de HF (segundo a DLCN) foi de 33%, 37 dos quais apenas 48% recebiam estatinas. O risco de DAC aumentou em 13 vezes (IC 95%: 10 a 17 vezes) em indivíduos com HF provável ou com certeza que não recebiam estatinas. Dados semelhantes foram observados em outras coortes com HF. 47

Por outro lado, o aumento do risco de DASCV em portadores de HF recebendo estatinas é 10 vezes maior (IC 95%: 8 a 14 vezes), o que sugere que as doses de estatinas resultaram em tratamento hipolipemiante insuficiente, ou foram introduzidas tarde na vida, quando a aterosclerose já se desenvolvia de maneira grave. Outros estudos sugerem os mesmos dados sobre o tratamento. 48-50

Na HF, o risco de DASCV prematura é muito elevado, e 5 a 10% dos eventos coronarianos ocorrem antes dos 50 anos. 47,51 Sem tratamento, portadores de HF jovens apresentam um risco de morte 90 vezes maior. 47,51 A doença é ainda responsável por número significativo de internações hospitalares e perda de produtividade, em função da alta incidência de DASCV. 47

Por isso, o diagnóstico precoce é fundamental, pois torna possível o início antecipado da medicação hipolipemiante e a mudança na história natural da doença, devendo ser guiado por diretrizes 52-54 e podendo ser facilitado pelo uso de algoritmos. 55 Além disso, a identificação dos casos de maior gravidade 56,57 e o cuidado integrado à HF 58 são estratégias para minimizar o impacto da HF na doença cardiovascular.

2. Metabolismo Lipídico na Hipercolesterolemia Familiar

A quantidade de colesterol circulante depende, por um lado, do balanço, principalmente, entre sua síntese hepática e sua absorção intestinal, e por outro, de sua excreção, especialmente pelas vias biliares. Quando ocorre desequilíbrio nesse processo, como ocorre na HF, o colesterol pode elevar-se significativamente e formar depósitos como xantomas e aterosclerose mais precoce. 22 A entrada e a saída do colesterol corpóreo são reguladas por sistema de retroalimentação, em que o aumento da sua absorção na dieta determina diminuição da síntese hepática. Ao contrário das gorduras alimentares, que são absorvidas pelo intestino quase completamente, o colesterol é absorvido de modo parcial, e quando sua quantidade na dieta aumenta, a absorção diminui proporcionalmente. No homem, a LDL transporta a maior parte do colesterol. As LDL são produto de metabolismo das lipoproteínas de densidade muito baixa (VLDL, do inglês, very low density lipoprotein ), ricas em triglicerídeos, mas que, sobretudo como remanescentes (lipoproteína de densidade intermediária [IDL, do inglês, intermediate-density lipoprotein ]), fornecem também colesterol para formação das placas. Além disso, ao serem deslipidadas em seu conteúdo de triglicerídeos, originam LDL menores e mais densas, consideradas muito aterogênicas. As LDL são removidas da circulação para o interior das células por receptores da membrana celular que reconhecem a Apo B-100, única proteína existente na LDL. Remanescentes e IDL são removidos também por esses receptores, mas de maneira bem mais rápida que a LDL. Isso acontece porque essas partículas, além da Apo B-100, têm Apo E na superfície, a qual apresenta afinidade bem maior pelos receptores do que a Apo B-100.

Na HF também ocorrem defeitos genéticos que afetam o receptor da LDL e que resultam em diminuição da endocitose da lipoproteína. 59 A existência da endocitose da LDL mediada por receptor e os defeitos que resultam em deficiência da função dos receptores e em hipercolesterolemia foram descritos por Brown e Goldstein na década de 1970. As várias centenas de polimorfismos no gene do receptor podem afetar tanto a estrutura do receptor que liga a Apo B-100 da LDL quanto outros domínios da proteína e até mesmo a recirculação dos receptores que normalmente são reciclados após a endocitose, voltando à membrana celular. Entretanto, apenas parte desses polimorfismos do receptor LDL se associam ao fenótipo da HF. Defeitos da Apo B e aqueles relacionados com ganho de função da PCSK9 que participa do catabolismo do receptor da LDL constituem aproximadamente 5%, e menos de 1% do fenótipo de HF. 2

Outra possibilidade ainda muito mais rara é o defeito em homozigose da proteína adaptadora do receptor de LDL, uma vez que esse polimorfismo é recessivo. Entretanto, estima-se entre 5 e 30% os pacientes com fenótipo de HF em que não se encontra o gene causal, sugerindo uma origem a partir de genes não identificados ou pela combinação (poligênica). Assim, a HF resulta da incapacidade de remoção eficiente do colesterol das LDL, determinando sua elevação plasmática e depósitos nos vasos e tecidos. 59

A HF resulta geralmente da transmissão de gene de um dos pais, como herança monogênica autossômica dominante, determinando mais frequentemente sua forma heterozigótica, estimada em 1:200 a 1:250 na Europa e ao redor de 1:250 no Brasil. Entretanto, não é infrequente a concomitância de aumento da lipoproteína (a) (Lp[a]) ou ainda a concomitância de defeito no metabolismo de triglicerídeos, determinando gravidade ainda maior da dislipidemia.

A ocorrência de xantomas na infância ou adolescência, junto com níveis muito elevados de LDL-c (> 500 mg/dl), doença aterosclerótica prematura e estenose valvar aórtica, sugere a forma homozigótica da HF, de muito maior gravidade e dificuldade no tratamento. 13 Nessa situação, a maioria dos indivíduos tem os pais com HFHe, geralmente por mutações no gene LDLR , mas que também podem ocorrer nos outros genes ( APOB ou PCSK9 ). Pode haver ainda a combinação de polimorfismos de diferentes genes ( LDLR , APOB , PCSK9 ou LDLRAP-1 ). Na forma homozigótica também é frequente a concomitância de baixos níveis de colesterol da lipoproteína de alta densidade (HDL-c), possivelmente por remoção acelerada da Apo A-I ou defeito no efluxo de colesterol. Manifestações homozigóticas também devem ser suspeitadas por elevações menos marcantes de LDL-c (> 300 mg/dl) na ocorrência de xantomas antes dos 10 anos. 13

3. Diagnóstico Clínico da Hipercolesterolemia Familiar

Os critérios clínicos e laboratoriais para o diagnóstico da HF são arbitrários e baseiam-se nos seguintes dados:

Sinais clínicos de depósitos extravasculares de colesterol

Taxas elevadas de LDL-c ou colesterol total no plasma

História familiar de hipercolesterolemia e/ou doença aterosclerótica prematura

Identificação de mutações e polimorfismos genéticos que favoreçam o desenvolvimento da HF.

Alguns critérios têm sido propostos na tentativa de uniformizar e formalizar o diagnóstico de HF, como os do US Make Early Diagnosis Prevent Early Death Program ( USA MEDPED ), 60 os da DLCN (Dutch MEDPED, ver Tabela 1 ), 61 e os do Simon Broome Register Group.62 No Brasil é utilizado o Dutch MEDPED .

Tabela 1. Critérios diagnósticos de HF heterozigótica com base nos critérios da Dutch Lipid Clinic Network (Dutch MEDPED) 61 .

| Parâmetro | Pontos |

|---|---|

| História familiar | |

| Parente de primeiro grau portador de doença vascular/coronariana prematura (homens com menos de 55, mulheres com menos de 60 anos) OU Parente adulto com colesterol total > 290 mg/dl * |

1 |

| Parente de primeiro grau portador de xantoma tendíneo e/ou arco corneano OU Parente de primeiro grau < 16 anos com colesterol > 260 mg/dl * |

2 |

| História clínica | |

| Paciente portador de doença coronariana prematura (homens com menos de 55, mulheres com menos de 60 anos) | 2 |

| Paciente portador de doença cerebral ou periférica prematura (homens com menos de 55, mulheres com menos de 60 anos) | 1 |

| Exame físico | |

| Xantoma tendíneo | 6 |

| Arco corneano < 45 anos | 4 |

| Níveis de LDL-c (mg/dl) | |

| ≥ 330 | 8 |

| 250 a 329 | 5 |

| 190 a 249 | 3 |

| 155 a 189 | 1 |

| Análise do DNA | |

| Presença de mutação funcional do gene do receptor de LDL, Apo B-100 ou PCSK9 * | 8 |

| Diagnóstico de HF | |

| Certeza se | > 8 |

| Provável se | 6 a 8 |

| Possível se | 3 a 5 |

Modificado de Dutch Lipid Clinic Network, adotando um critério do Simon Broome Register Group. 62 LDL-c: colesterol da lipoproteína de baixa densidade; DNA: ácido desoxirribonucleico; HF: hipercolesterolemia familiar.

Essa diretriz recomenda a utilização de critérios simples para a suspeita diagnóstica de HF e para a decisão de se iniciar o tratamento (ver adiante). Um algoritmo com base no Dutch MEDPED pode ser empregado para melhor precisão diagnóstica, embora não esteja disponível até o momento validação para a população brasileira.

3.1. Anamnese

Dada a alta prevalência de HF na população geral e o seu grande impacto nas taxas de doença cardiovascular e mortalidade, toda anamnese deve incluir a pesquisa de histórico familiar de hipercolesterolemia, de uso de medicamentos hipolipemiantes e de doença aterosclerótica prematura, incluindo a idade de acometimento. A possibilidade de HF é sempre reforçada com história familiar de hipercolesterolemia e/ou doença aterosclerótica prematura.

3.2. Exame Físico

A pesquisa pelos sinais clínicos da HF (xantomas, xantelasmas e arco córneo) deve fazer parte do exame físico rotineiro e pode ser complementada por exames subsidiários, como o ultrassom de tendão, em casos selecionados. Tais sinais clínicos não são muito sensíveis, mas podem ser bastante específicos, ou seja, embora não haja necessidade deles para o diagnóstico da HF, quando identificados, sugerem fortemente essa etiologia.

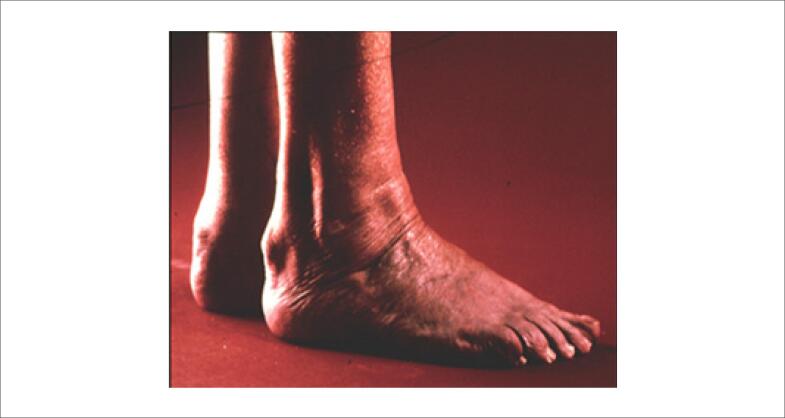

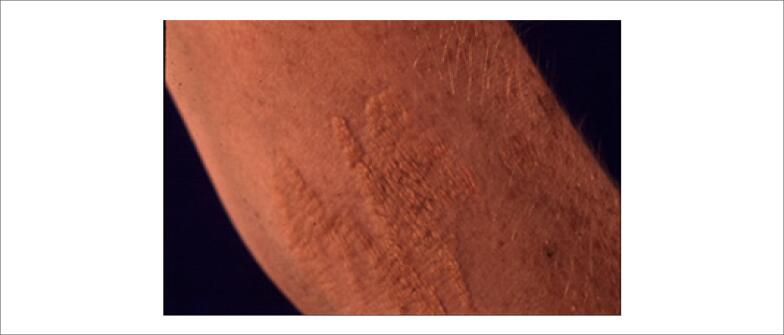

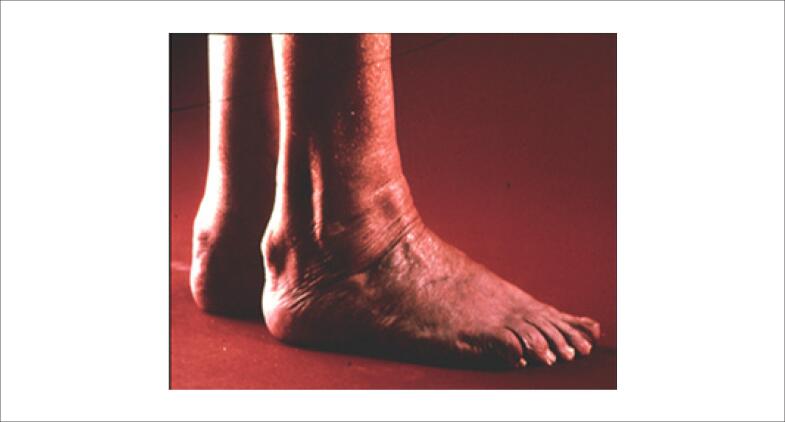

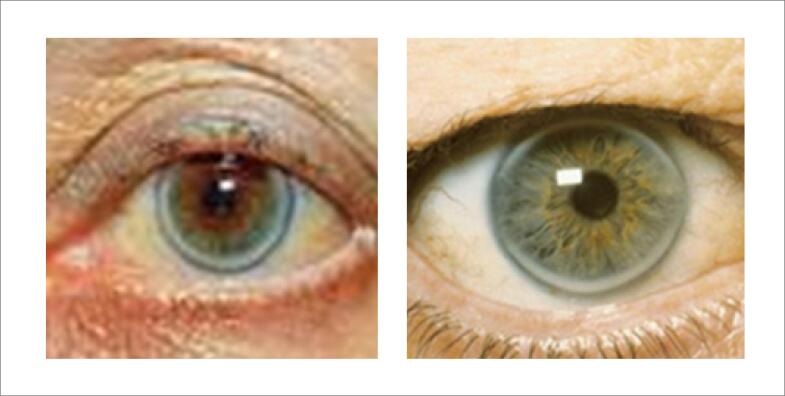

Os xantomas tendinosos ( Figura 1 ) são mais comumente observados no tendão de Aquiles e nos tendões extensores dos dedos, mas também podem ser encontrados nos tendões patelar e do tríceps. Eles devem ser pesquisados não só pela inspeção visual, mas também pela palpação. São praticamente patognomônicos de HF, mas ocorrem em menos de 50% dos casos. 63 Podem ocorrer também xantomas planares intertriginosos, especialmente na HF homozigótica ( Figura 2 ).

Figura 1. Xantoma tendinoso em tendão calcâneo.

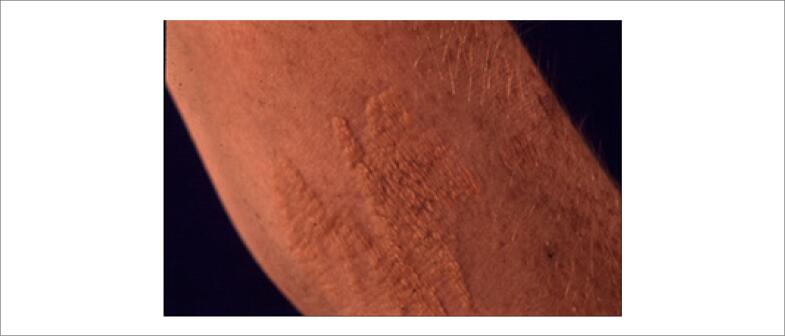

Figura 2. Xantoma plano.

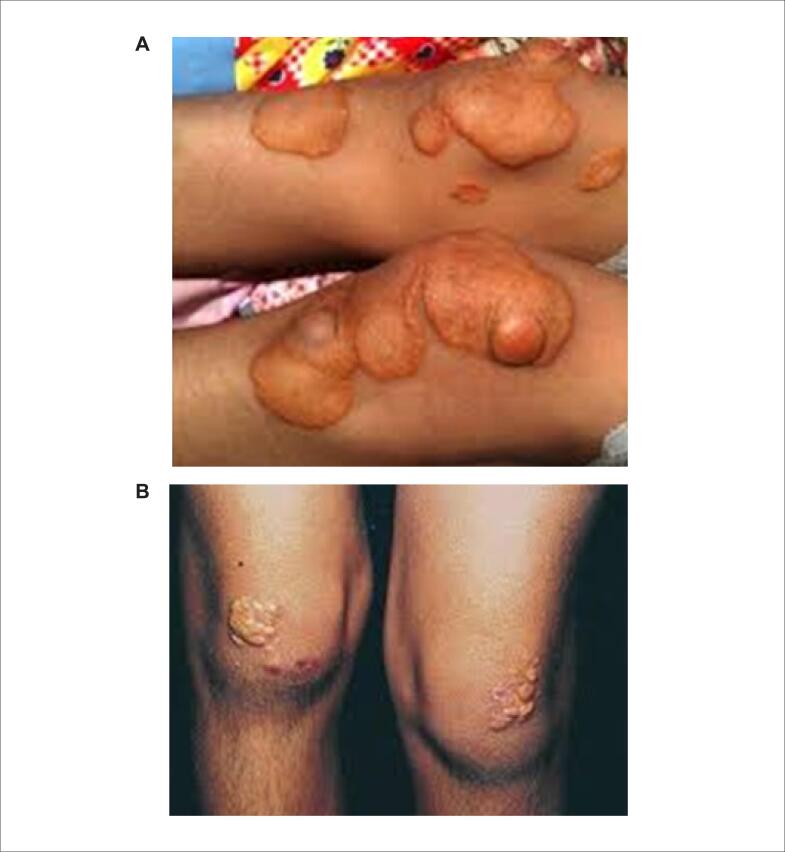

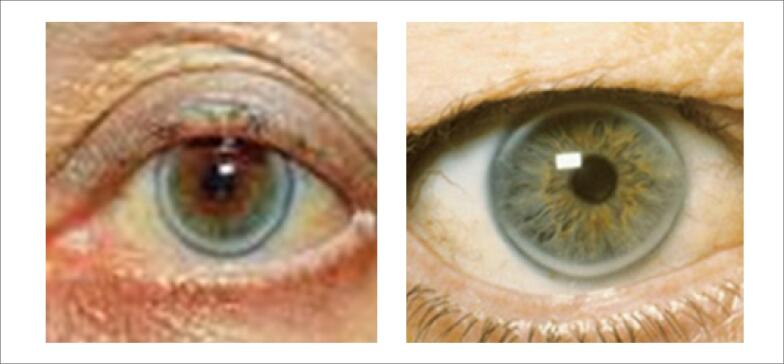

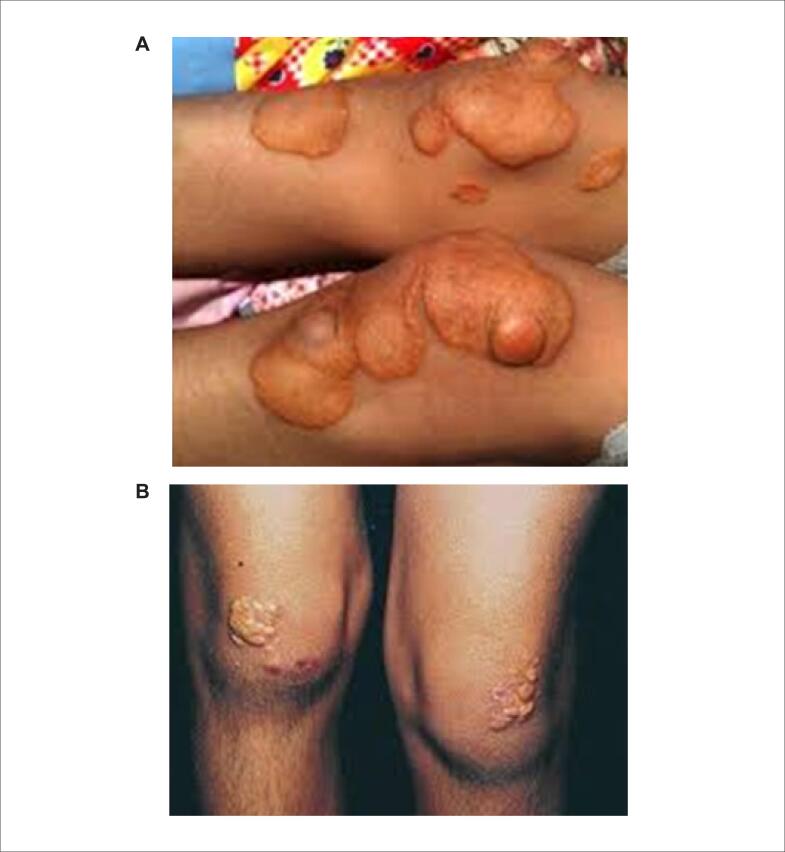

Os xantomas tuberosos amarelo-alaranjados (Figuras 3 e 4 ) e os xantelasmas de pálpebras não são específicos de HF e devem ser valorizados quando encontrados em pacientes com idade em torno de 20 a 25 anos. A presença de arco córneo, parcial ou total, sugere HF quando observada antes dos 45 anos de idade ( Figura 5 ). Portadores da forma homozigótica da HF podem apresentar também sopro sistólico ejetivo decorrente de estenose da valva aórtica e da região supra-aórtica.

Figura 3 (A e B). Xantomas tuberosos em joelhos.

Figura 4. Xantomas tuberosos em mãos.

Figura 5. Arco córneo.

3.3. Rastreamento e Níveis Lipídicos

A coleta de sangue para determinação das taxas de colesterol total e LDL-c visando rastrear a HF é de fundamental importância para o diagnóstico do maior número possível de casos e, consequentemente, para reduzir o impacto da doença sobre a morbimortalidade cardiovascular na população geral. Esse rastreamento pode ser realizado por meio de dois métodos: o chamado rastreamento universal e o rastreamento em cascata. 23,52

3.3.1. Rastreamento Universal

Todas as pessoas acima dos 10 anos de idade devem ser submetidas à análise do perfil lipídico. 52 A obtenção dos lípides plasmáticos também deve ser considerada a partir dos 2 anos de idade nas seguintes situações: 52

Quando houver história familiar de doença aterosclerótica prematura (homens com menos de 55 anos ou mulheres com menos de 65 anos) e/ou dislipidemia.

Se a própria criança apresentar xantomas ou arco córneo, fatores de risco (hipertensão arterial, diabetes melito, obesidade) ou doença aterosclerótica.

A periodicidade recomendada para a determinação dos lípides plasmáticos é motivo de debate. Em geral, se o perfil lipídico for normal, mas existirem outros critérios de possível HF, como história familiar de doença aterosclerótica precoce ou hipercolesterolemia significativa, o exame poderá ser repetido após um ano. Na ausência desses fatores, o exame pode ser repetido em até cinco anos. Alguns dados, como idade, presença de outros fatores de risco para aterosclerose, grau de controle dos fatores de risco, hábitos de vida e eventual uso de medicamentos que possam interferir no metabolismo lipídico, podem ser considerados para individualizar a periodicidade das dosagens lipídicas.

O diagnóstico positivo de HF deve sempre ser suspeitado em adultos (≥ 20 anos) com valores de LDL-c ≥ 190 mg/dl. Na população geral, a probabilidade de ter a doença é de aproximadamente 80% no caso de LDL-c ≥ 250 mg/dl em indivíduos com 30 anos ou mais, ou LDL-c ≥ 220 mg/dl em pessoas entre 20 e 29 anos, ou LDL-c ≥ 190 mg/dl nos que têm menos de 20 anos. 61 O diagnóstico de HF é também mais provável em portadores de LDL-c ≥ 190 mg/dl cujas famílias são caracterizadas por distribuição bimodal do LDL-c, nas quais alguns membros apresentam taxas tipicamente baixas (LDL-c < 130 mg/dl), enquanto outros (os afetados por HF) exibem taxas tipicamente elevadas, ≥ 190 mg/dl. 62

Antes do diagnóstico de HF, no entanto, devem ser afastadas causas secundárias de hipercolesterolemia, incluindo hipotireoidismo e síndrome nefrótica. Deve-se ressaltar também que a presença de hipertrigliceridemia não exclui o diagnóstico de HF.

No Brasil, desde 2017 os laudos laboratoriais destacam valores de colesterol total ≥ 310 mg/dl em adultos e ≥ 230 mg/dl em crianças e adolescentes como sugestivos de HF. 64

Por fim, deve-se considerar que a determinação do perfil lipídico está sujeita a uma série de variações relacionadas tanto ao método e aos procedimentos utilizados como a fatores peculiares do indivíduo, como estilo de vida, uso de medicações e doenças associadas. Desse modo, a confirmação de alteração laboratorial com nova amostra, idealmente coletada com intervalo mínimo de uma semana após a primeira coleta, aumenta a precisão diagnóstica.

3.3.2. Rastreamento em Cascata

O rastreamento em cascata envolve a determinação do perfil lipídico em todos os parentes de primeiro grau (pai, mãe e irmãos) dos pacientes diagnosticados com HF. As chances de identificação de outros portadores da doença a partir de um caso-índice são: 50% nos familiares de primeiro grau, 25% nos de segundo grau e 12,5% nos de terceiro grau. 63 À medida que novos casos vão sendo identificados, novos parentes vão sendo recomendados para o rastreamento. Essa medida é considerada a que tem a melhor relação custo-eficácia para a identificação de portadores de HF.

3.3.2.1. Rastreamento Genético em Cascata

O rastreamento genético é custo-efetivo e pode ser realizado em todos os pacientes e familiares em primeiro grau das pessoas com diagnóstico de HF. O rastreamento em cascata mais custo-efetivo é o que utiliza informação genética de indivíduos afetados nos quais uma mutação causadora da doença tenha sido identificada. 63

3.3.2.2. Cascata Reversa

Trata-se da investigação de familiares de primeiro, segundo e terceiro graus a partir de uma criança como caso-índice e, portanto, de maneira reversa. Muitas vezes, a criança com HF é a primeira a ser diagnosticada pelo pediatra, e seus pais desconhecem se são também portadores dessa condição. Portanto, é uma oportunidade de identificação e de tratamento de pai(s) afetados assintomáticos e que nunca utilizaram medicação. 23

3.3.2.3. Diagnóstico Oportunístico

É a situação em que o rastreamento do perfil lipídico se faz no momento da imunização. No Brasil, essa não é uma prática comum, mas seria uma oportunidade de diagnóstico precoce de crianças assintomáticas. 23,59

3.3.3. Hipercolesterolemia Familiar Homozigótica

Historicamente, a prevalência da HFHo é muito rara, estimada em 1:1.000.000 de indivíduos na população ao redor do mundo. Entretanto, atualmente, são registradas prevalências maiores do que as inferidas em uma população geral, que variam de 1:160.000 a 1:300.000. 13,52 Os critérios diagnósticos de HFHo são apresentados no Quadro 1 .

Quadro 1. Critérios diagnósticos na hipercolesterolemia familiar homozigótica (HFHo).

| 1. Confirmação genética de dois alelos mutantes nos genes LDLR , APOB , PSCK9 , ou no lócus do gene LDLRAP1 OU |

| 2. LDL-c sem tratamento > 500 mg/dl ou LDL-c tratada > 300 mg/dl mais algum dos seguintes critérios: |

| xantomas cutâneos ou tendinosos antes dos 10 anos OU |

| valores de LDL-c elevados consistentes com HF heterozigótica em ambos os pais * |

Exceto no caso de hipercolesterolemia autossômica recessiva. HF: hipercolesterolemia familiar; LDL-c: colesterol da lipoproteína de baixa densidade. Os valores de LDL-c são apenas indicativos de HF homozigótica, mas devem ser considerados valores menores para o diagnóstico de heterozigotos compostos ou duplos, na presença de outros critérios.

3.4. Recomendações

Sinais clínicos de HF e história familiar de doença aterosclerótica precoce e/ou dislipidemia devem ser pesquisados em todos os indivíduos (recomendação classe I, nível de evidência C).

O perfil lipídico deve ser obtido em todos os indivíduos acima dos 10 anos de idade (recomendação classe I, nível de evidência C).

A determinação do perfil lipídico deve ser considerada a partir dos 2 anos de idade na presença de fatores de risco, sinais clínicos de HF ou doença aterosclerótica, bem como no caso de história familiar de doença aterosclerótica prematura e/ou de dislipidemia (recomendação classe I, nível de evidência C).

O perfil lipídico deve ser obtido em todos os parentes de primeiro grau dos indivíduos diagnosticados como portadores de HF (recomendação classe I, nível de evidência C).

4. Teste Genético para Hipercolesterolemia Familiar

A HF é uma doença autossômica codominante. É causada, principalmente, por alterações genéticas capazes de provocar perda de função no receptor da LDL, na APOB e, com menos frequência, quando ocorrem alterações que promovem ganho de função na proteína PCSK9, responsável pela degradação do receptor da LDL.

4.1. Receptor da LDL, Apo B, PCSK9 e Remoção da LDL Circulante

O receptor da LDL está localizado na superfície das células hepáticas e de outros órgãos, ligando-se à LDL via Apo B. Isso leva à sua captação, realizada por um mecanismo de internalização e endocitose do complexo LDL/Apo B/LDLR. Esse processo é mediado pela proteína adaptadora do LDLR tipo 1 (LDLRAP1) presente nas depressões revestidas com clatrina ( clathrin-coated pits ). Após internalização, a partícula de LDL e o LDLR separam-se no endossoma, e o LDLR pode sofrer degradação lisossomal facilitada pela PCSK9 ou ser transferido de volta à superfície da célula, sendo o colesterol liberado na célula para metabolismo ou eliminação. Alternativamente, o LDLR pode ser degradado via ligação da PCSK9 exógena ao LDLR na superfície celular, na qual é internalizada e processada para degradação lisossomal. 16 Quando os LDLR apresentam alguma alteração genética que modifique sua estrutura ou função, o nível de remoção de LDL do plasma diminui e, consequentemente, o nível plasmático de LDL-c aumenta em proporção inversa ao número de receptores funcionais presentes. 65

4.2. Herança Autossômica Dominante

Classicamente a HF é causada por variantes patogênicas nos genes LDLR , APOB e PCSK9 . O gene que codifica o receptor de LDL ( LDLR ) compreende aproximadamente 45.000 pares de bases de DNA e localiza-se no cromossomo 19, sendo formado por 18 éxons e 17 íntrons. O LDLR é uma proteína composta de 839 aminoácidos, incluindo um peptídeo sinal de 21 aminoácidos com vários domínios funcionais.

A análise das mutações descritas no gene LDLR demonstra que não existem regiões principais em sua sequência ( hot spots ) para o aparecimento de alterações. 66,67 Apesar disso, mutações no éxon 4, responsável pela ligação à LDL via Apo B, parecem estar correlacionadas a fenótipos mais graves da doença. 66-70 De modo interessante,, mutações “de novo” no gene LDLR parecem ser raras. 71 A produção é finamente regulada por um mecanismo de retroalimentação sofisticado, que controla a transcrição do gene LDLR em resposta a variações no conteúdo intracelular de esteróis e da demanda celular de colesterol. 72

Existem cerca de 2.900 alterações genéticas associadas à HF, 73 e aproximadamente 85 a 90% ocorrem no gene LDLR . A HF é mais comumente atribuível a alterações no gene LDLR (incluindo missense, nonsense e inserções e deleções), resultando em LDLR com reduções funcionais (parcial a completa) em sua capacidade de remover a LDL da circulação. Dependendo do impacto da mutação sobre a proteína resultante, o indivíduo pode ser receptor-negativo, que expressa pouco ou nenhum LDLR, ou receptor-defeituoso, que expressa isoformas de LDLR com afinidade reduzida para LDL na superfície dos hepatócitos. 70,74-77

Em indivíduos heterozigotos, um alelo com alteração patogênica é herdado de um dos pais, e um alelo normal, do outro. Como dois alelos funcionais são necessários para manter o nível plasmático normal de LDL-c, a ausência de um funcional pode causar um aumento no nível de LDL para aproximadamente duas vezes o normal já na infância. 72 Os indivíduos homozigotos herdam dois alelos com variantes patogênicas; consequentemente, os LDLR têm funcionalidade muito reduzida, e os pacientes são portadores de uma hipercolesterolemia muito grave (400 a 1.000 mg/dl). 72

Existem cinco principais classes de alterações no gene LDLR: 70,76

Classe I (mutações nulas): essas alterações afetam a região promotora ou a região codificante do gene, o que resulta na total ausência de síntese do LDLR ou na síntese de um receptor não funcional.

Classe II: ocasionadas por defeitos no processamento pós-tradução ou falha no transporte do LDLR do retículo endoplasmático para o complexo de Golgi, resultando em menor expressão na superfície celular.

Classe III: a LDL não se liga corretamente ao LDLR na superfície da célula, graças a um defeito no domínio de ligação do substrato ou no domínio que apresenta homologia estrutural ao Fator de Crescimento Epidérmico (EGF), presentes no LDLR.

Classe IV: o LDLR liga-se normalmente à LDL, mas esta não é internalizada eficientemente pelo mecanismo de endocitose via depressões revestidas com clatrina ( clathrin-coated pits ).

Classe V: o LDLR não é reciclado de volta para a superfície celular.

O gene APOB tem 42 kb, é formado por 29 éxons e 28 íntrons, e dá origem a duas isoformas de proteínas: uma pequena, denominada Apo B-48, e uma grande, chamada de Apo B-100. A primeira é produzida no intestino, sendo um componente dos quilomícrons e seus remanescentes; a segunda é produzida no fígado e é um componente de várias lipoproteínas, como VLDL, IDL, LDL e lipoproteína(a) [Lp(a)]. A hipercolesterolemia, devido à mutação no gene APOB , resulta em um fenótipo clínico de HF semelhante ao causado por mutações em outros genes, sendo referida classicamente como defeito familiar da APOB (FDB, do inglês, familial defective Apo B ). 15 Entretanto, é importante enfatizar que, atualmente, o FDB é considerado um dos tipos de HF, e sua distinção é feita apenas do ponto de vista acadêmico.

Em contraste com o gene LDLR , apenas 353 variantes estão descritas para o gene APOB, 80 e a maioria delas encontra-se no éxon 26. 78-80 A mutação mais comum no gene APOB é a substituição Arg3500Gln, que causa o rompimento da estrutura da proteína. Essa variante corresponde a 5 a 10% dos casos de HF nas populações do norte da Europa, sendo, porém, rara em outras populações. 79,80

Outra possível condição que leva a um fenótipo da HF é o aumento da atividade de PCSK9, também chamada de HF3, na qual mutações com ganho de função levam a maior degradação do LDLR. 16,80,81 Essa é a causa menos comum de HF, representando 1 a 3% dos casos de HF clinicamente diagnosticados. 80,81 O gene PCSK 9 tem 25 kb, contém 12 éxons e dá origem a uma proteína de 692 aminoácidos.

4.3. Hipercolesterolemia Autossômica Recessiva

Além dos genes descritos anteriormente, tem-se considerado como uma das causas do fenótipo da HFHo alterações da LDLRAP1. Diferentemente da HF clássica, esses distúrbios têm herança autossômica recessiva, sendo essa forma denominada hipercolesterolemia autossômica recessiva (ARH, do inglês, autosomal recessive hypercholesterolemia ). Nela a expressão reduzida da LDLRAP1 dificulta a associação do LDLR nas depressões revestidas com clatrina da superfície celular, 82,83 consequentemente reduzindo ou impedindo a internalização do complexo LDL/LDLR no hepatócito. O gene LDLRAP1 tem 25 kb, é composto por nove éxons e dá origem a uma proteína de 308 aminoácidos. Apenas indivíduos com mutações no gene em homozigose ou heterozigose composta são afetados; os heterozigotos simples são considerados apenas portadores, pois geralmente não apresentam hipercolesterolemia. Entretanto, existem casos descritos na literatura de portadores com níveis de LDL-c mais altos que outros membros da família e que não apresentam nenhuma alteração. 84

4.4. Outros Genes Candidatos

Além dos genes apresentados, outros candidatos a serem causadores de HF são: APOE, IDOL (MYLIP), HCHOLA4, STAP1 e LIP A. 85

Formas raras de ARH (também denominadas fenocópias da HF) incluem sitosterolemia ou fitosterolemia, em razão de mutações em dois genes adjacentes e com orientações opostas ( ABCG5 e ABCG8 ), que codificam proteínas transportadoras da família ABC ( ATP-binding cassette ), denominadas esterolina-1 e esterolina-2. 86 Elas estão envolvidas na eliminação de esteróis de plantas, que não podem ser utilizados pelas células humanas, e na deficiência de colesterol 7-alfa hidroxilase (CYP7A1), que é a enzima da primeira etapa na síntese de ácidos biliares, resultando em colesterol intra-hepático e aumentado e expressão reduzida de LDLR na superfície do hepatócito. A deficiência de CYP7A1 é a menos comum das condições autossômicas recessivas que podem causar graves hipercolesterolemias. 87

4.5. Variabilidade do Fenótipo na Hipercolesterolemia Familiar

Estudos atuais mostram que a HF engloba um espectro de fenótipos clínicos com base, em parte, na gama de variantes patogênicas. Assim, indivíduos com mais de uma alteração no mesmo gene e em alelos diferentes (heterozigotos compostos em trans, geralmente do LDLR ) podem ter um fenótipo similar ao de um homozigoto verdadeiro (mesma variante em dois alelos). 23,88 A Tabela 2 mostra a variabilidade da distribuição dos valores pré-tratamento de LDL-c para vários genótipos de HF. 23

Tabela 2. Variabilidade no fenótipo da hipercolesterolemia familiar por ordem decrescente de concentrações de LDL-c.

| Valores de LDL-c | Genótipos possíveis |

|---|---|

| 400 a 1.000 mg/dl | Variantes patogênicas em homozigose |

| Homozigoto LDLR “nulo” | |

| Verdadeiro homozigoto LDLR | |

| Heterozigoto composto LDLR | |

| 130 a 450 mg/dl | Variantes patogênicas em heterozigose |

| LDLR “nulo” | |

| LDLR defeituoso | |

| Ganho de função da PCSK9 | |

| APOB | |

| Formas poligênicas (múltiplos SNP que elevam o LDL-c) | |

| Lipoproteína (a) elevada | |

| 130 a 200 mg/dl | Hipercolesterolemia comum |

Adaptada de Sturm et al. 23 LDL-c: colesterol da lipoproteína de baixa densidade; LDLR: receptor da LDL; PCSK9: proproteína convertase subutilisina/kexina tipo 9; APOB: apolipoproteína B; SNP: polimorfismo de nucleotídeo único.

É importante ressaltar que já foram descritos níveis normais de LDL-c em indivíduos com alterações patogênicas em famílias portadoras de HF, e nem sempre é identificada alteração patogênica em pessoas com fenótipo da doença. Desse modo, a presença de um fenótipo compatível com HF sem identificação de alteração patogênica nos clássicos genes LDLR , APOB e PCSK9 pode estar ligada à herança poligênica. Talmud et al. 89 descreveram conjuntos de 12 polimorfismos em diferentes genes em indivíduos hipercolesterolêmicos em que não foi encontrada uma alteração causal. 89 Segundo os autores, a herança poligênica explicaria até 88% dos casos de hipercolesterolemia em geral e cerca de 20% daqueles com fenótipo de HF na ausência de causas monogênicas clássicas. 90

4.6. Racional para Realização do Rastreamento em Cascata

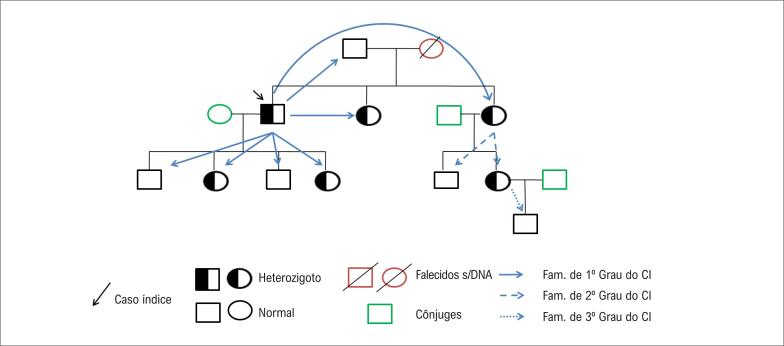

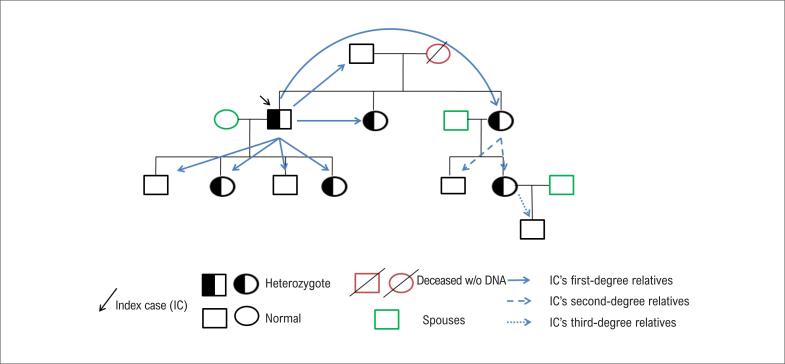

Na HF, o rastreamento genético em cascata vem sendo utilizado como ferramenta para a identificação de novos indivíduos afetados. As alterações patogênicas correlacionadas à doença podem ser identificadas em 30 a 80% dos pacientes, dependendo dos critérios de inclusão e da sensibilidade dos métodos utilizados para o rastreamento. 91,92 A técnica nada mais é do que o sequenciamento das alterações em parentes de primeiro grau de indivíduos identificados com HF. 93 Em rodadas de rastreamento, os parentes de primeiro grau identificados com a afecção passam a ser os casos-índices, e seus respectivos parentes começam a ser rastreados ( Figura 6 ).

Figura 6. Exemplo de rastreamento genético em cascata. DNA: ácido desoxirribonucleico.

A cascata genética é a estratégia mais custo-efetiva para a identificação de indivíduos portadores de HF. 93-95 Marks et al. 93 analisaram essa custo-efetividade, e foi determinado que o custo incremental por ano de vida adquirido era de £ 3.300 por vida ao ano. O programa foi o mais custo-efetivo na Dinamarca, e o custo por vida ao ano foi de US$ 8.700,00, demonstrando uma estimativa de custos menor que o gasto com prevenção secundária em indivíduos não portadores de HF. 96

Estudos mostram que pouquíssimos indivíduos com HF são diagnosticados. Em geral, estima-se que aproximadamente 20% dos pacientes com a doença recebem diagnóstico, e menos de 10% têm tratamento adequado. 10 Assim, o rastreamento em cascata aumenta o número de diagnósticos e diminui a idade com que o indivíduo é diagnosticado, oferecendo-lhe maior chance de tratamento precoce e diminuição do risco cardiovascular global.

O teste genético geralmente não é necessário para diagnóstico ou tratamento clínico de um caso-índice, mas pode ser útil quando o diagnóstico é incerto e para a identificação de familiares de um indivíduo afetado. O método de rastreamento em cascata tem sido utilizado por vários países, como Espanha, 96 Inglaterra, Holanda, 97 Portugal 98 e, mais recentemente, no Brasil, 99 como ferramenta bastante custo-efetiva na identificação de novos portadores de HF.

Em publicação realizada em um consórcio de estudos genéticos, 24 a presença de uma variante patogênica causadora da HF foi encontrada em 2% dos casos graves (LDL-c > 190 mg/dl encontrado em cerca de 7% da população). Indivíduos com a variante monogênica causadora da HF tinham um risco 22 vezes maior de eventos cardiovasculares do que os normolipidêmicos sem alterações genéticas e 4 vezes maior do que os hipercolesterolêmicos sem alterações. 24 Essa elevação foi atribuída principalmente à exposição dos portadores de HF a colesterol alto desde o nascimento, diferentemente da hipercolesterolemia poligênica, que pode manifestar-se mais tardiamente. Esses dados sugerem fortemente que a presença de variante genética patogênica causadora da HF tem implicação prognóstica.

Além disso, a identificação de uma alteração causal pode fornecer uma motivação adicional para alguns pacientes iniciarem o tratamento adequado, e o teste genético é padrão-ouro para o diagnóstico de certeza de HF. Pode ser particularmente útil nos casos de familiares com diagnóstico clínico equivocado ou apenas com nível de LDL-c sugestivo da doença. Testes genéticos também podem ser importantes para a identificação de uma alteração causal em famílias recém-identificadas ou com forte suspeita de HF. Ademais, quando encontrada a alteração, o teste fornece uma resposta simples e definitiva para o diagnóstico da HF, tornando-se ferramenta incontestável para a doença como traço familiar. 23

No entanto, os testes genéticos têm limitações. Entre os pacientes hipercolesterolêmicos com diagnóstico de possível HF, a taxa de identificação de uma alteração causal por meio do teste genético é de 50% ou menos, enquanto, em pacientes com HF definitiva segundo critérios clínicos, a taxa de identificação da mutação pode ser tão alta quanto 86%. 23,100 Desse modo, é importante ressaltar que um teste genético negativo não exclui a HF. Além disso, indivíduos com LDL-c elevado permanecem em alto risco cardiovascular e devem ser tratados de acordo com diretrizes aceitas, independentemente dos resultados dos testes genéticos.

4.7. Metodologias para Diagnóstico Genético

O defeito no gene causal do fenótipo da HF, se LDLR , APOB , PCSK9 ou LDLRAP1 , além dos outros mais raros já citados, não pode ser determinado clinicamente, sendo necessário um teste genético para sua verificação. Assim, por conta da variabilidade de genes e do grande número de mutações possíveis, o método de diagnóstico genético deve incluir o sequenciamento da região codificadora de todos os genes possivelmente ligados à etiologia da doença. 101

Para que seja possível esse sequenciamento em grande escala, de modo que um grupo de genes seja sequenciado (painel de genes-alvo), é necessária a utilização da tecnologia de sequenciamento de nova geração (NGS, do inglês, next-generation sequencing ). Nessa técnica, é feito um painel contendo todos os genes a serem sequenciados, os quais são colocados em um chip. Outro enfoque mais amplo é a utilização do sequenciamento de exomas, o qual possibilita determinar a sequência da região codificante de praticamente todos os genes presentes no genoma em questão. Contudo, apesar de esse enfoque fornecer uma extensa cobertura do genoma, muitos genes podem não ser sequenciados perfeitamente. Assim, em casos específicos de doenças monogenéticas, como é o caso da HF, painéis contendo os genes-alvo configuram-se como uma alternativa mais custo-efetiva, além de mais precisa.

A tecnologia NGS apresenta muitas vantagens em relação ao sequenciamento Sanger, considerado padrão-ouro nessa técnica. Dentre as vantagens, podem ser citados: a velocidade de obtenção de resultados, a quantidade de material necessário utilizado na reação, o custo do sequenciamento por base, a quantidade de informação gerada e a precisão dos resultados obtidos. Resumidamente, para o estudo genético, é efetuada coleta de sangue periférico em tubo contendo ácido etilenodiamino tetra-acético (EDTA, do inglês, ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid ), obtendo-se o DNA genômico de leucócitos. A primeira etapa na preparação do material consiste na geração de uma biblioteca de fragmentos de DNA flanqueados por adaptadores específicos. As regiões de interesse dos genes em estudo são amplificadas por meio da reação em cadeia da polimerase em larga escala, em reações multiplexadas, com centenas de pares de oligonucleotídeos em um mesmo tubo de reação. A partir destas reações, são construídas bibliotecas com códigos de barras para identificar cada paciente analisado. Os fragmentos gerados são amplificados, por clonagem, em esferas por reação em cadeia da polimerase em emulsão, as quais são aplicadas em um chip e inseridas no equipamento de NGS. Uma vez gerados, os dados são transferidos para uma plataforma, na qual as leituras são mapeadas com o genoma humano (hg19/GRCh37) e é realizada a interpretação das variantes.

Cerca de 10% das alterações genéticas no gene do LDLR não são pontuais, 99 mas sim grandes deleções ou duplicações de éxons do LDLR . Portanto, caso não seja identificada nenhuma alteração por NGS, é importante realizar a técnica de amplificação multiplex de sondas dependente de ligação 102 (MLPA, do inglês, multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification ) (MCR-Holland) para identificar prováveis deleções e ou duplicações.

O rastreamento em cascata é custo-efetivo e deve ser realizado em todos os pacientes e familiares em primeiro grau de indivíduos com diagnóstico de HF. O mais custo-efetivo é o que utiliza informação genética de pessoas nas quais uma mutação causadora da doença tenha sido identificada. O rastreamento clínico/bioquímico deve ser realizado mesmo quando a realização de teste genético não é possível. 103-105

Um resumo dos benefícios e das limitações para realização do teste genético em cascata pode ser visto no Quadro 2 , adaptado de Sturm et al. 23

Quadro 2. Benefícios e limitações do teste genético em cascata. 23 .

| Benefícios |

| 1. Fornece diagnóstico definitivo para a HF. |

| 2. Fornece informações prognósticas e a capacidade de realizar estratificação de risco refinado, porque a detecção de uma variante patogênica indica maior risco cardiovascular. |

| 3. Resultados de testes genéticos positivos mostraram aumentar a iniciação da terapia hipolipemiante, a adesão à terapia e as reduções nos níveis de LDL-c. |

| 4. A detecção precoce oferece a oportunidade para modificações mais precoces no tratamento e no estilo de vida. |

| 5. Quando o teste genético no probando é positivo, leva a testes genéticos em cascata em membros da família em risco com alta sensibilidade e especificidade. |

| 6. Pode excluir HF nos membros da família em risco que não herdam a(s) variante(s) patogênica(s). |

| 7. O teste genético proporciona discriminação a nível molecular entre indivíduos com HFHe, HFHe composta, HF de duplo heterozigoto, HFHo, HF autossômica recessiva e os sujeitos sem uma variante patogênica identificável, mas com o fenótipo de HF. Os riscos de recorrência para parentes e as implicações para o planejamento familiar diferem entre esses cenários. |

| 8. O teste genético possibilita a identificação potencial de “fenocópias” de HF que podem requerer terapias específicas e ter padrões de herança diferentes dos da HF. |

| 9. Pode fornecer motivação adicional para os indivíduos terem maior aderência aos medicamentos prescritos. |

| 10. Fornece uma explicação para o fracasso da dieta e exercício de controle para controlar níveis elevados de lipídios |

| 11. Fornece uma explicação útil para a história familiar de doença cardíaca prematura e níveis de LDL-c difíceis de tratar. |

| Limitações |

| 1. O teste genético para a HF não é completamente sensível ou específico. |

| 2. Nem todos os pacientes com diagnóstico clínico de HF terão variante(s) patogênica(s) identificável(s) |

| 3. Alguns pacientes terão uma variante de significância incerta (VUS, do inglês, variant of uncertain significance ) identificada, que pode ser reclassificada como patogênica ou benigna ao longo do tempo, à medida que mais informações são obtidas. |

| Custo |

| 1. Indivíduos podem querer passar por testes genéticos, mas o custo deles pode ser um fator limitante. |

Adaptado de Sturm et al. 23

HF: hipercolesterolemia familiar; HFHe: HF heterozigótica; HFHo: HF homozigótica; LDL-c: colesterol da lipoproteína de baixa densidade.

4.8. Recomendação

Triagem laboratorial: Todo indivíduo com suspeita de HF (caso-índice) deverá ter seus familiares de primeiro grau testados para hipercolesterolemia. Caso o resultado seja positivo, deverá ser realizada uma triagem em cascata em outros familiares (de segundo e terceiro graus). Grau de recomendação: I, nível de evidência: A.

Triagem genética: O teste genético deverá ser oferecido para o caso-índice; se positivo, deverá ser realizado em seus familiares de primeiro grau. Caso o resultado seja positivo, deverá ser realizada uma triagem em cascata em outros familiares (de segundo e terceiro graus). Grau de recomendação: II, nível de evidência: A.

5. Estratificação de Risco Cardiovascular

5.1. Epidemiologia do Risco Cardiovascular na Hipercolesterolemia Familiar

A associação entre HFHe e DAC está bem estabelecida. 51,105 isso porque, na ausência de terapia hipolipemiante, existe um risco cumulativo de doença coronariana fatal e não fatal de aproximadamente 50% em homens e 33% em mulheres até 60 anos. 51 No estudo do Simon Broome Register Group , realizado no período de 1980 até 1995, apesar do tratamento, constatou-se aumento do risco relativo de evento coronariano fatal de 125 vezes entre mulheres com HF e de 20 a 39 anos (mortalidade anual de 0,17%) em relação à população geral da Inglaterra e do País de Gales. Em homens com HF e idade entre 20 e 39 anos, o risco relativo aumentou em 48 vezes (mortalidade anual de 0,46%). 4

Estudos mais recentes corroboram o risco aumentado de DAC entre indivíduos com HF (LDL-c ≥ 190 mg/dl), seja de causa monogênica ou poligênica. No estudo de Khera et al., 24 observou-se risco aumentado de eventos cardiovasculares entre indivíduos com LDL-c ≥ 190 mg/dl, mesmo na ausência de mutação para HF identificada, em relação àqueles com colesterol normal. 24 De 1.386 pessoas com LDL-c ≥ 190 mg/dL (6,7% do total), apenas 24 (1,7%) tinham mutação detectada. Aquelas com LDL-c ≥ 190 mg/dL e sem mutação apresentaram seis vezes mais risco de DAC em relação ao grupo-controle (LDL-c < 130 mg/dL e sem mutação), enquanto as com LDL-c ≥ 190 mg/dL e com mutação demonstraram 22 vezes mais risco. 24

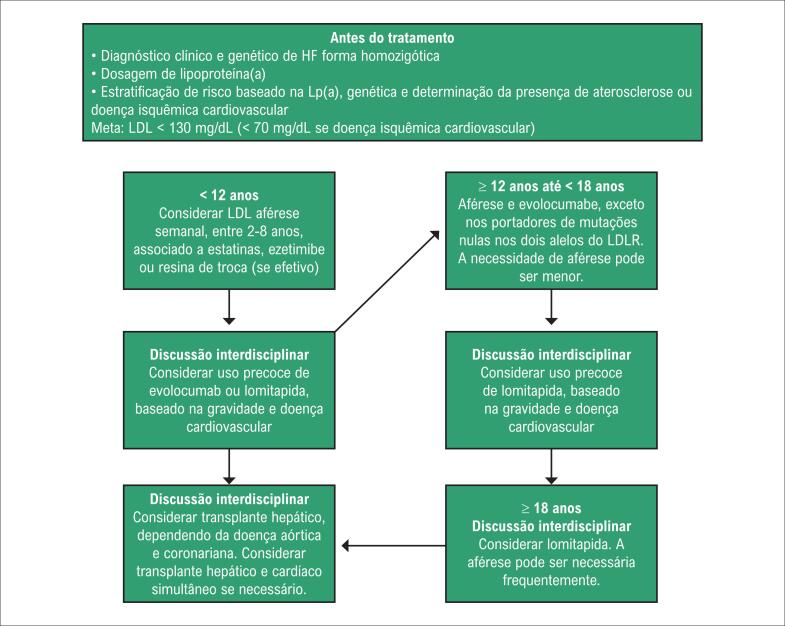

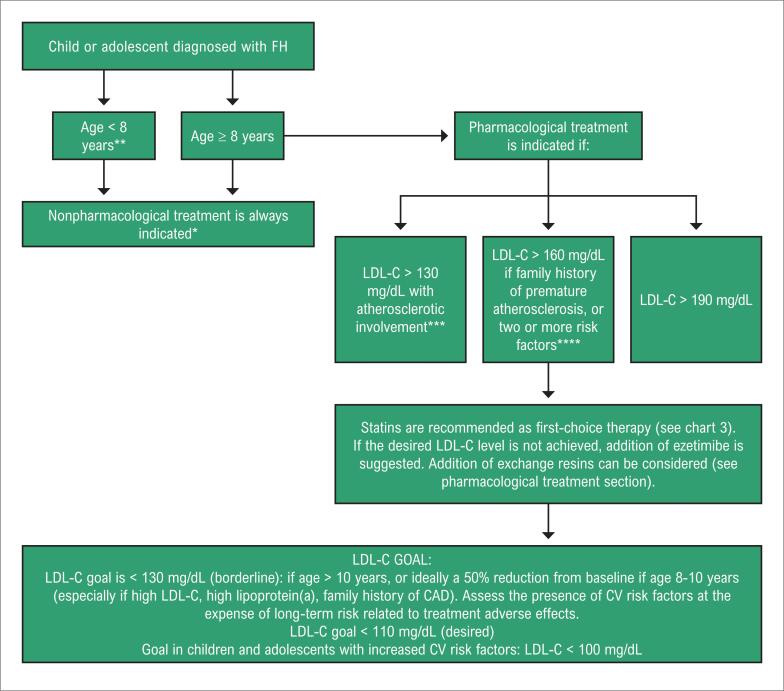

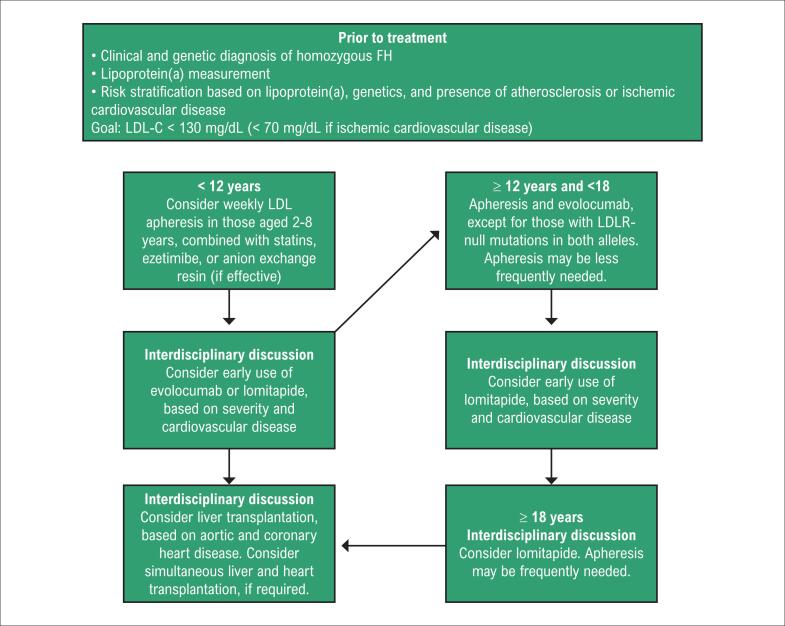

Em outro estudo recente, entre pacientes com HF de diagnóstico clínico, a presença de uma causa monogênica da doença se mostrou associada a risco cardiovascular significativamente aumentado (HR ajustado 1,96; IC 95% 1,24 a 3,12; p = 0,004), enquanto o risco cardiovascular em pacientes com hipercolesterolemia poligênica não foi diferente em comparação àqueles sem causa genética identificada. No entanto, a presença de escore poligênico em indivíduos com HF monogênica aumentou ainda mais o seu risco cardiovascular (HR ajustado 3,06; IC 95% 1,56 a 5,99; p = 0,001). 106