Abstract

Objectives –

To show the feasibility of using different unobtrusive activity-sensing technologies to provide objective behavioral markers of patients with dementia (PwD).

Design –

Monitored the behaviors of two PwD living in memory care unit using the Oregon Center for Aging & Technology (ORCATECH) platform, and the behaviors of two PwD living in assisted living facility using the Emerald device.

Setting –

A memory care unit in Portland, Oregon and an assisted living facility in Framingham, Massachusetts.

Participants –

A 63-year-old male with Alzheimer’s disease (AD), and an 80-year-old female with frontotemporal dementia, both lived in a memory care unit in Portland, Oregon. An 89-year-old woman with a diagnosis of AD, and an 85-year-old woman with a diagnosis of major neurocognitive disorder, Alzheimer’s type with behavioral symptoms, both resided at an assisted living facility in Framingham, Massachusetts.

Measurements –

These include: sleep quality measured by the bed pressure mat; number of transitions between spaces and dwell times in different spaces measured by the motion sensors; activity levels measured by the wearable actigraphy device; and couch usage and breathing amplitudes measured by the Emerald device.

Results –

Number of transitions between spaces can identify the patient’s episodes of agitation; activity levels correlate well with the patient’s excessive level of agitation and lack of movement when the patient received potentially inappropriate medication and neared the end of life; couch usage can detect the patient’s increased level of apathy; and breathing amplitude can help detect risperidone-induced periodic limb motion. This is the first demonstration that the ORCATECH platform and the Emerald device can measure such activities.

Conclusions –

The use of technologies for monitoring behaviors of PwD can provide more objective and intensive measurements of PwD behaviors.

Keywords: unobtrusive activity-sensing technology, late-stage dementia, Alzheimer’s disease, technology, behavioral and psychological symptoms, agitation, apathy, end-of-life, potentially inappropriate medication

Objective

Behavioral and Psychological Symptoms of Dementia (BPSD), also called neuropsychiatric symptoms, are the wide range of non-cognitive symptoms and behaviors experienced by persons with dementia (PwD). BPSD can occur in all types of dementia and they include symptoms such as agitation, aggression, anxiety, apathy, depression, and sleep disturbances (1). BPSD often progresses over time, and they correlate with institutional placement, more rapid progression of dementia, and earlier mortality. Some of the symptoms, such as agitation and aggression, can also endanger patients themselves and/or their caregivers. This makes treatment and management of BPSD an important aspect of dementia research. Many different factors may contribute to BPSD, such as personal discomfort(2–4), social interaction(5) or the physical environment(6, 7). Current treatment of BPSD follows both a non-pharmacologic (8–12) and a pharmacologic (13–16) approach. Many of the treatment options, especially the pharmacologic ones, have adverse side effects (17, 18). One needs to have a clear understanding and assessment of the patient’s BPSD to prescribe the most appropriate treatments.

In order to assess the appropriateness and effectiveness of treatments for BPSD, objective and intensive monitoring of PwD is needed. Currently, the behaviors of PwD are most often subjectively assessed by their caregivers through surveys and medical records, which can contain bias (19). In addition, formal caregivers are often time-constrained and cannot be expected to observe the patient continuously. This does not allow more reliable guidance for pharmacotherapy. Using passive environmental technologies promising advances have been made in the measurement and quantification of neuropsychiatric symptoms such as restlessness, wandering, vocalization, and sleep disturbances (20, 21). Some of the technologies presented in this paper have been used to assess sleep in PwD before, such as bedmat(22, 23) and actigraphy(24–26). However, one of the technologies presented in this paper, motion sensors, while they have been used in other published monitoring systems(27, 28), their use is still in infancy and its feasibility for assessing nighttime behaviors have not been established. The advantages of motion sensors are that they cost less, are contactless unlike the actigraphy and would provide information such as lifespace of the participant which is not available from bedmat. Also, another technology presented in this paper, the Emerald device, is also very ambient and it can detect the location and motion of the participant within his living space. Participants presented in this paper all have late-stage and severe Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders (ADRD) with varying behavioral characteristics. These participants are of particular interest as their behavioral symptoms are often most severe. The use of unobtrusive activity-sensing technology may help assess the severity and frequency of their symptoms. Also, these participants are near the end of their life and they receive numerous medications, the use of technology can potentially guide the pharmacological intervention and even palliative care so that the patients’ discomfort and the side effects from medication can be minimized. In this paper, we present case series evidence of the feasibility of using these technologies to provide objective behavioral markers of four PwD with varying behavioral characteristics and how they can be helpful in guiding the treatment of the participants.

Methods

The studies presented in this paper have been approved by the Oregon Health & Science University (OHSU) and Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) institutional review boards (IRB) (OHSU IRB#18464 and MIT protocol #1910000025).

For the study approved by OHSU, the target population has moderate to severe dementia and is decisionally impaired who scores above 50 on the Cohen Mansfield Agitation Inventory (CMAI)(29). The participants may not be able to engage in the informed consent process depending on the severity of their conditions, therefore, it is also required that a legally authorized representative provides informed consent in addition to, or in place of, the participant. Legally authorized representatives for participants also sign a Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) form upon enrollment, to authorize the disclosure of the participanťs current long-term care facility records to the Oregon Center for Aging & Technology (ORCATECH) (30) study team during the period of enrollment. ORCATECH has research agreements with two memory care facilities (both in Portland, Oregon) from which participants with dementia for Cases 1 and 2 were recruited. Diagnosis and stage of dementia was confirmed through chart review of their medical histories. The protocol was to also assess degree of cognitive impairment with the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), but the assessment could not be conducted due to the severity of symptoms in both participants (aggression/agitation in Case 1, and non-verbal in Case 2). A data capturing platform developed at the ORCATECH(30) was used to collect data from these two cases and the behavioral sensors incorporated were PIR motion sensors manufactured by NYCE Sensors (Vancouver, BC), bed pressure mats manufactured by Emfit (Finland) placed underneath the mattresses, and wearable actigraphy devices, Actiwatch Spectrum, manufactured by Philips Respironics (Murrysville, PA) (31). The PIR motion sensors included 1) three motion sensors (NCZ-3041-HA) with restricted-view (created using custom 3D printed covers that concealed part of the motion sensor lens) which were installed in the main living space for each patient to detect motion in subsections of the living space (one above the bed, one on the opposite wall from the one above the bed (over a futon), and one above the front door), 2) one motion sensor (NCZ-3041-HA) in each patient’s bathroom, and 3) four curtain sensors (NCZ-3045-HA) which were placed in a line on the ceiling of the main living space for measuring walking speeds (32, 33). The Emfit bed pressure mat was placed under each participant’s mattress and was able to detect the presence of the participant in their bed. The bed mat was also used to measure the participants’ physiological signals, such as respiratory rates and heart rate variability (34). Utilizing these signals, the bed pressure mat infers the sleep stages of the participants (35) and derives a sleep score based upon variables such as duration of sleep, number of bed exits, and duration spent in each sleep stage. Participants were asked to continuously wear the actigraphy devices, Actiwatch Spectrums, day and night during the study, and facility staff agreed to support continuous use. The wearable actigraphy devices measured the activity level of each patient using an activity count, which was collected every 15 seconds (36).

Cases 3 and 4 were residents in an assisted living facility in Framingham, Massachusetts. For these patients, the research team utilized a novel sensor developed at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology called the Emerald (37). For both participants, consent was provided by the healthcare proxy, since clinicians determined that neither participant had the capacity to provide informed consent. Both participants provided assent to install the technology in their living areas. As with Cases 1 and 2, attempts to quantify cognitive status using standardized instruments (the Montreal Cognitive Assessment for Cases 3 and 4), were not successful because the subjects were not able to participate in a meaningful way. The Emerald device uses a radio-wave sensor and signal processing algorithms to track the position of users. The device requires no physical contact or direct interaction by the person being monitored. It also requires no charging. The device transmits radio signals that reflect off objects in the environment back to the device. The device processes variations in these reflections to infer changes in the 3-dimensional position of the user. Accuracy of the device has been validated against a VICON Motion Tracking System in individuals aged 20–83 in the lab and numerous residential settings. The device is wall-mounted and measures an individual’s position to within 15cm and gait speed to within 0.025m/s (38). It is able to track gait speed, spatial location, as well as the movement of individual limbs. Based on this motion mapping, the device has been validated for its ability to detect sleep patterns, respiratory rate and behavior such as pacing. We have established the feasibility of using this device in assisted living settings with patients with dementia (37).

Results

Case 1

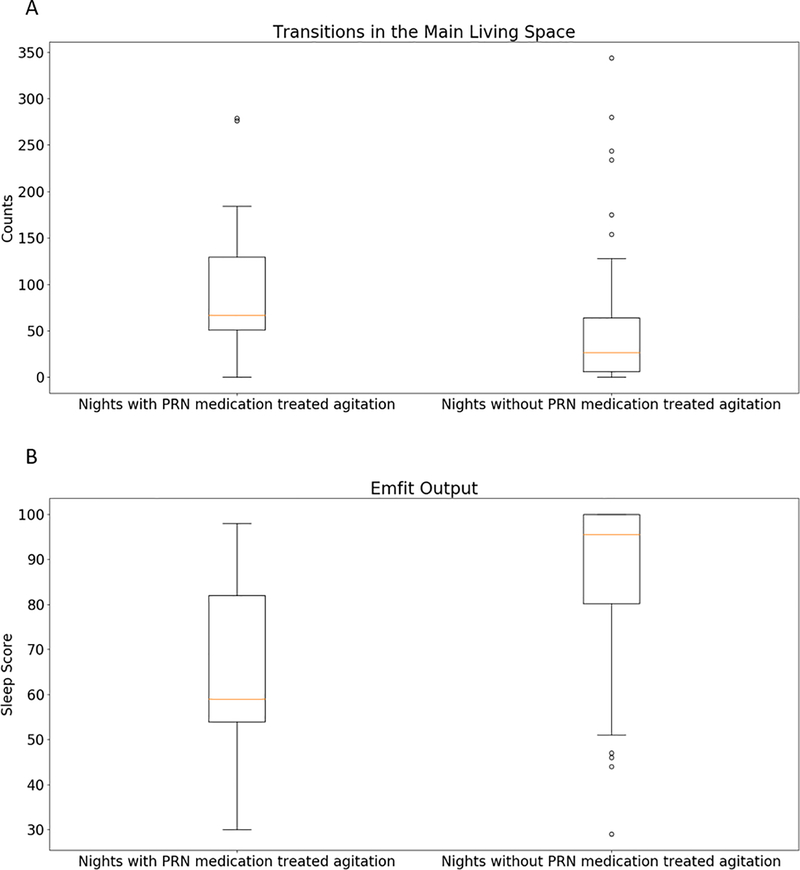

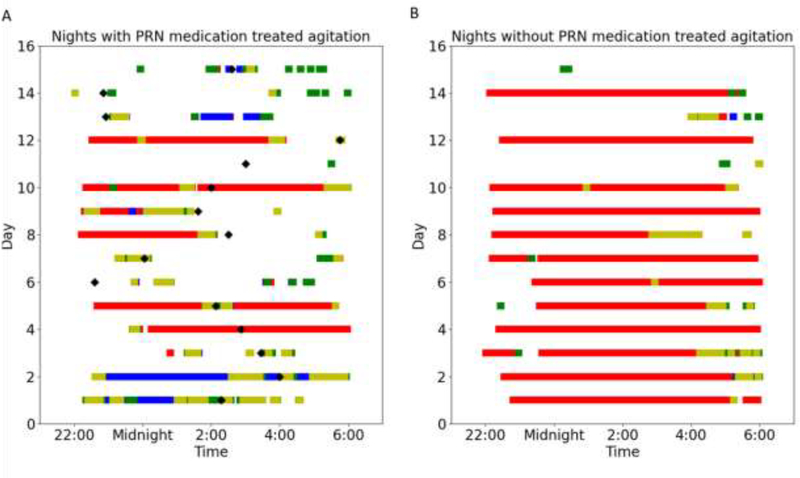

Our first case was a 63 year old male with Alzheimer’s disease residing in a memory care unit in Portland, Oregon. He was given a standing order for administration of risperidone (0.25 mg in AM, 0.5 mg in PM) and lorazepam (0.5 mg in PM) for agitation related to dementia. The pro re nata (PRN) risperidone was only given for agitation as needed up to two times daily. This patient was normally very physically active and had frequent episodes of agitation. During an observation period of 115 night shifts (10 pm-6 am), there were 15 occasions when the patient received PRN medication for treatment of agitation. Often agitation is manifested through pacing, excessive motor activity and disturbed sleep. Using the PIR motion sensors placed in this patient’s main living space, we were able to measure the number of times the patient transitioned between subsections within the living room and the bathroom. It was hypothesized that a high number of transitions between these sections would indicate pacing, and it was found that this feature was significantly associated with periods of agitation (Mann-Whitney U test: p<0.01). The subplot A in Figure 1 shows the boxplot of this feature on agitated nights versus non-agitated nights. The median number of transitions on agitated nights was 67 with an interquartile range from 51 to 130, while the median number of transitions on non-agitated nights was 27 with an interquartile range from 6 to 64.. In addition, the sleep score output by the Emfit bed pressure mat, which is a proxy for the sleep quality of the participant, was also a significant correlative feature for the occurrences of agitation (Mann-Whitney U test: p<0.01). This Emfit output, sleep score, ranges from 0 to 100. The higher the sleep score, the better the sleep quality. The sleep score was significantly lower on agitated nights. On agitated nights, the sleep score had a median of 68 with an interquartile range from 58 to 81 while the sleep score had a median of 98 with an interquartile range from 79 to 100 on non-agitated nights. The subplot B in Figure 1 shows a boxplot of sleep quality on agitated nights versus non-agitated nights. Figure 2 shows the participant’s location within his main living space detected by the PIR motion sensors on agitated nights (A) versus non-agitated nights (B). It can be observed that the participant was in bed much less often and was outside of his main living space a lot more frequently during agitated nights. Also, the time periods spent in the different spaces were also more fragmented during agitated nights.

Figure 1:

A: Boxplot of the number of transitions between subsections within the main living space on nights with PRN medication treated agitation versus nights without PRN medication treated agitation. B: Boxplot of the sleep score from Emfit on nights with PRN medication treated agitation versus nights without PRN medication treated agitation.

Figure 2:

Participant’s locations in the main living space during the 15 nights with PRN medication treated agitation (A) vs participant’s locations in the main living space during 15 randomly selected nights without PRN medication treated agitation (B). Time periods highlighted red indicates that presence detected around the bed, blue indicates presence detected around the futon, green indicates presence detected around the front door, yellow indicates presence detected around the bathroom. The black diamonds indicate the times PRN medications were administered to the patient.

Case 2

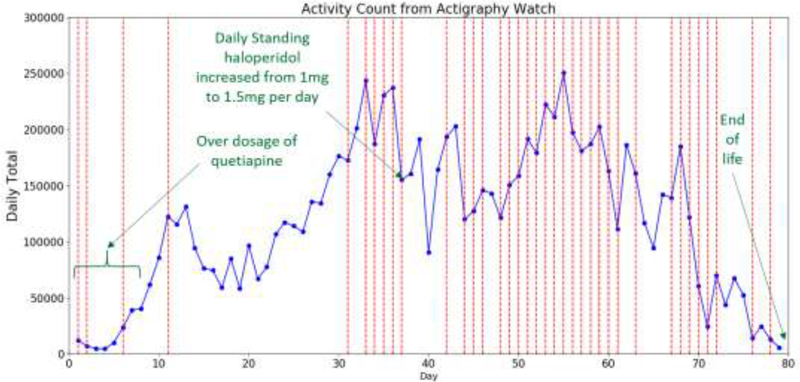

Our second case was an 80-year-old female with frontotemporal dementia (FTD) who lived in a memory care unit in Portland, Oregon. She was not independently mobile and wore an actigraphy watch during the monitoring period of 79 days. The day before the monitoring period began, the dosage of her standing quetiapine prescription started on a tapering regimen, with a new prescription of standing haloperidol initiated (0.5 mg twice daily), which she received as ordered. The patient’s quetiapine prescription was written as 100mg each day (50mg at 8 am and 50 mg at 5 pm) for 5 days but she received 125mg each day (75mg at 8 am and 50 mg at 5 pm) for 5 days (a medication error). On day 6, she received 75mg of quetiapine in the morning and then none in the evening shift. On day 7, she received 75mg in the morning and 50mg in the evening. On day 8, the resident received 50mg in the morning and 25mg in the evening (instead of 25mg in the morning and 25mg in the evening as prescribed). She had 58 episodes of agitation, each treated with PRN-medication haloperidol, morphine sulfate, or lorazepam, over the monitoring period. Figure 3 shows daily total activity counts from the wearable actigraphy device worn by the participant. The daily total activity counts correlated well with the annotations of behavioral change and medication events. When medication errors involving quetiapine occurred, the participant exhibited very little activity (mean daily total activity count for the first 8 days is 17696 while the median daily total activity count for the entire monitoring period is 121348). After the dosage was corrected, the actigraphy counts reflected increased activity and the participant’s medical records reflected a period of increasing agitation. On the day when the daily standing Haloperidol was increased due to the high level of agitation, the daily total activity count exhibited a 34.6% decrease from 237375 to 155306. On days with PRN medication administered, the median daily total activity count is 158680 with interquartile range from 120052 to 191683. On days without PRN medication administered, the median daily total activity count is 94338 with an interquartile range from 59784 to 135443. The daily total activity count is significantly correlated with the occurrence of PRN-treated agitation (Mann Whitney U test: p<0.001). Toward the end of the observation period, the participant entered the end of life phase, and the daily total activity counts showed a downward trend. These events demonstrate the effectiveness of wearable actigraphy device in measuring the activity levels of PwD.

Figure 3:

Line chart of daily total activity counts from the wearable actigraphy device worn by the patient in case 2. Red vertical lines indicate days with occurrences of agitation. Notable events are annotated with green text.

Case 3

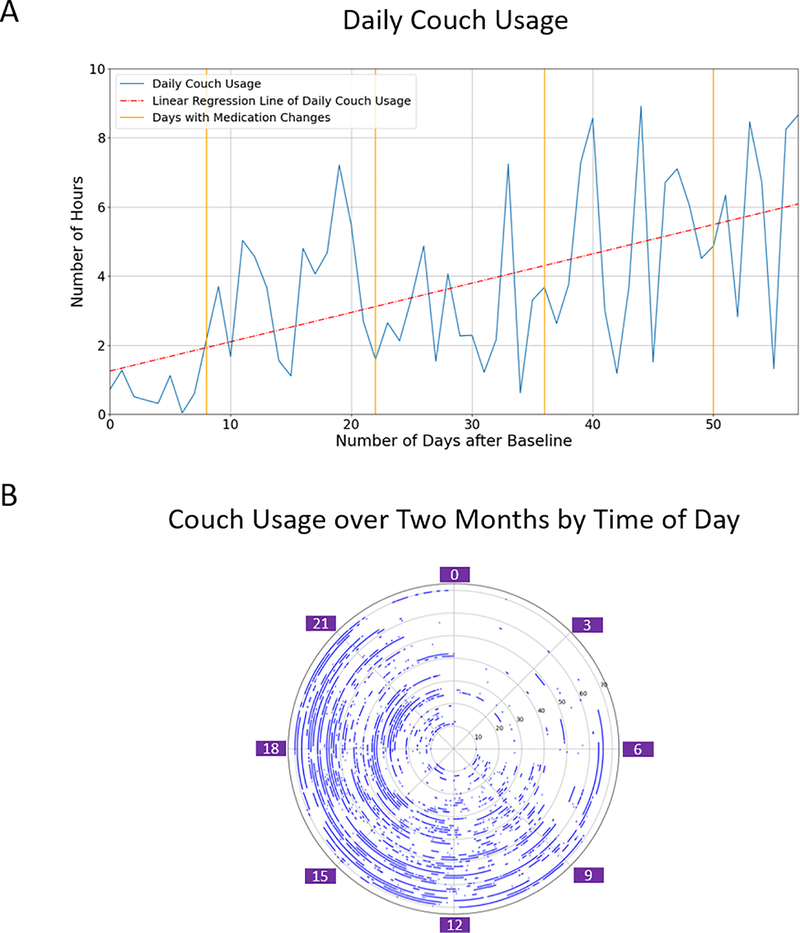

The third case was an 89-year-old woman with a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease who resided at an assisted living facility in Framingham, Massachusetts. She moved into this facility shortly after discharge from a geriatric psychiatry inpatient unit where she was hospitalized for management of worsening depressive symptoms. Upon arrival, the patients medication regimen included dronabinol 10 mg BID (for anxiety), trazodone, and mirtazapine (for insomnia and depression). Over the course of her stay, the patient demonstrated steadily worsening apathy and psychomotor retardation. She was monitored using the Emerald device for a 2-month period. During this time, we established that the time she spent sitting on her couch appeared to be the primary marker of her worsening neurovegetative status. The subplot A of Figure 4 shows changes in time spent on her couch over time. While there is variance on a day-to-day basis, aggregating this over time indicated that as her clinical condition worsened, total amount of time she spent sitting on her couch without any additional activity steadily increased. The subplot B of Figure 4 demonstrates that during the time when the patient was awake, the number of hours that she spent on her couch increased. This was initially attributed to worsening depression, and her treating team initiated a series of medication changes that included discontinuing dronabinol and trazodone, given their potential for causing sedation and psychomotor retardation. She was started on bupropion with the goal of increasing activation. However, no appreciable change in her motor function was noted. The treating team considered other medications such as stimulants, but it was determined that her declining psychomotor function was related to progression of her Alzheimer’s disease, and ultimately aggressive psychopharmacological management was discontinued in favor of a more palliative care approach.

Figure 4:

A: Daily couch usage over 0 to 57 days after baseline. On Day 8, trazodone reduced from 50 to 25mg. On Day 22, dronabinol 2.5mg discontinued. On Day 36, mirtazapine increased from 7.5 to 15mg. On Day 50, mirtazapine discontinued and bupropion introduced. B: Couch usage over two months by time of day.

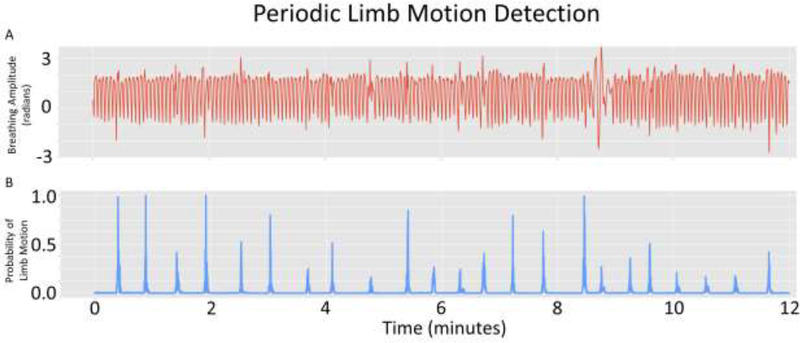

Case 4

The fourth case was an 85-year-old woman with a diagnosis of major neurocognitive disorder, Alzheimer’s type with behavioral symptoms. The patient moved into the assisted living facility in Framingham Massachusetts following an inpatient geriatric psychiatry hospitalization for acute behavior symptoms that included resistance to care, verbal aggression, and physical aggression towards her caregivers. Her behavioral symptoms stabilized on risperidone at a dose of 0.5 mg 3 times a day. Upon moving into the assisted living facility, we monitored her using the Emerald device over a 3-month period with the original goal of determining whether the medication was leading to increased sedation. The device was able to determine the time spent asleep and awake in bed by cross referencing degree of whole body movement against the spatial location of the patienťs bed. While her sleep pattern was determined to be stable and appropriate, the device identified unusual motion signals. The study team was able to isolate these signals as regular episodic movements of her lower limb (see Figure 5). These had never been reported previously according to the patienťs caregiver. The clinical team estimated that these may represent risperidone-induced periodic limb movements. Based on this information, the team initiated a decrease in her risperidone dose, which led to subsequent resolution of these periodic limb movements as well as an improvement in the patienťs overall motor function

Figure 5:

A: Limb and vital signs motion captured from the bed area over time. B: Filtered motion signal to extract Periodic Limb Movements.

Conclusions

Our primary goal with this case series is to provide proof of concept for monitoring PwD in situ in their living environment using unobtrusive activity-sensing technology. Our team of investigators utilized different technological approaches in two geographically distinct areas (Portland, Oregon and Framingham, Massachusetts), but with the same clinical and research goals - to characterize behavior patterns based on unobtrusive activity-sensing technology. As unobtrusive motion-sensing technologies become more sophisticated, they are also becoming more portable, affordable, user-friendly, and there have been rapid advances in the process of collecting, cleaning, and analyzing the vast amount of data that these technologies generate. This, in turn, has led to easier translation of these technologies towards clinical application. A major aspect of this case series is that all 4 patients were monitored in their natural living environments. The data were gathered continuously and processed remotely. Previously, such continuous monitoring would not have been possible without the use of cameras or direct in-person observation. These motion sensing approaches result in data that are inherently distinct from any personally identifying information and can therefore preserve privacy while also generating information that may be clinically useful, and once validated, hold the potential to shift the paradigm of aging care.

The availability of these data, combined with clinical correlation led to the generation of information that had direct clinical implications. Across our cases we were able to detect behavioral activation (in the case of subject 1) as well as psychomotor retardation/apathy (in the case of subject 3). Moreover, we were able to detect medication—induced motor side effects. In the case of subject 2, actigraphy data combined with clinical correlation were able to identify quetiapine induced sedation. In the case of subject 4, radio wave sensing was able to localize individual limb movement that helped clinicians identify risperidone-induced periodic limb movement that had never been reported for this patient previously.

While the use of unobtrusive activity-sensing technology for clinically meaningful behavior monitoring remains in its infancy, we believe that our data may point the way for a substantial leap in the way care is provided and managed in long term care facilities. Integrating the ability to objectively identify behavioral and cognitive changes as well as medication effects in PwD without further adding staffing resources (and the resulting costs) can potentially achieve the sometimes-conflicting goals of more precise care that can also be scalable without further increasing cost and burden of care. To achieve this goal however much work remains. Larger studies with more diverse populations and other symptoms will be needed to understand the full range of behavioral symptoms that can be captured with in-residence motion sensing. Such large studies are also required for analyzing the sensitivity and specificity of potential behvaioral markers obtained via motion sensing. We believe that the potential to use changes in motor behavior to monitor medication effects and side effects may be especially promising. Smooth integration of these systems in care delivery and management requires realtime support and enhanced visualization. In order for such technology to scale, it will also be crucial to develop transparency around how data are collected, stored and accessed. The twin issues of privacy and security will be foundational for this field to realize their potential. For all four cases in this report, data were collected, stored and analyzed securely as mandated by the IRB. For cases 1 and 2, the ORCATECH platform did not record any videos or conversations so the patients’ privacy was preserved. For cases 3 and 4, the PwD, family members and staff all had the ability to disconnect the Emerald device for privacy reasons if it was determined necessary. When fully realized, we believe that activity-sensing will augment in-person care by providing objective information that can be put into clinical context by clinicians, care providers and staff to obtain a more individualized assessment of PwD longitudinally, as well as enable better palliative care.

Nonetheless, these technologies hold the potential to have a significant impact on both quality and cost of dementia care. They may facilitate early detection and intervention of behavioral symptoms, which in turn is likely to reduce acute clinical events that may lead to hospitalization. The ability to monitor behaviors using sensors may also eventually improve the effort in care required for in person support which is one of the primary drivers of the high cost of care for dementia.

Highlights.

This study is to show the feasibility of using different passive environmental sensing approaches to provide objective behavioral markers of patients with dementia (PwD).

Different behavioral and psychological symptoms experienced by four PwD, such as agitation and apathy, are detected by features from the data collected using passive environmental sensing approaches such as passive infrared motion sensors and the Emerald device. Some examples of these features include number of transitions between spaces and couch usage.

These technologies may facilitate early detection and intervention of behavioral symptoms experienced by PwD, and the ability to monitor PWD’s behaviors using sensors may also eventually improve the effort in care required for in person support.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by intramural funding from the McLean Technology in Aging Lab and National Institute on Aging (NIA) grants: P30 AG008017; P30 AG066518; P30 AG024978; U2CAG0543701; T32AG055378-03 A1.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosure/Conflicts of Interest

Dr. Au-Yeung reports grants from National Institute on Aging, during the conduct of the study. Dr. Beattie reports grants from National Institutes of Health, during the conduct of the study. Dr. Kabelac reports personal fees from Emerald Innovations Inc, outside the submitted work. Dr. Katabi reports other from Emerald innovations, outside the submitted work; In addition, Dr. Katabi has a patent Motion tracking via body radio reflections issued to Emerald innovations. Dr. Kaye reports grants from National Institute on Aging, during the conduct of the study. Dr. Vahia reports other from American Journal of geriatric psychiatry, outside the submitted work. For the remaining authors none were declared.

References

- 1.Cerejeira J, Lagarto L, Mukaetova-Ladinska E: Behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia. Frontiers in neurology 2012; 3:73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ballard C, Smith J, Corbett A, et al. : The role of pain treatment in managing the behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD). International journal of palliative nursing 2011; 17:420–424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cohen-Mansfield J, Thein K, Marx MS, et al. : Sources of discomfort in persons with dementia. JAMA Internal Medicine 2013; 173:1378–1379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Husebo BS, Ballard C, Cohen-Mansfield J, et al. : The response of agitated behavior to pain management in persons with dementia. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 2014; 22:708–717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beerens HC, Zwakhalen SM, Verbeek H, et al. : The relation between mood, activity, and interaction in long-term dementia care. Aging & Mental Health 2018; 22:26–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Figueiro MG, Hunter CM, Higgins PA, et al. : Tailored lighting intervention for persons with dementia and caregivers living at home. Sleep Health 2015; 1:322–330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tartarini F, Cooper P, Fleming R, et al. : Indoor Air Temperature and Agitation of Nursing Home Residents With Dementia. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease & Other Dementias 2017; 32:272–281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brotons M, Pickett-Cooper PK: The effects of music therapy intervention on agitation behaviors of Alzheimer’s disease patients. Journal of Music Therapy 1996; 33:2–18 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cohen-Mansfield J: Nonpharmacologic interventions for inappropriate behaviors in dementia: a review, summary, and critique. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 2001; 9:361–381 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Livingston G, Kelly L, Lewis-Holmes E, et al. : Non-pharmacological interventions for agitation in dementia: systematic review of randomised controlled trials. The British Journal of Psychiatry 2014; 205:436–442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.VanVracem M, Spruytte N, Declercq A, et al. : Agitation in dementia and the role of spatial and sensory interventions: experiences of professional and family caregivers. Scandinavian journal of caring sciences 2016; 30:281–289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ueda T, Suzukamo Y, Sato M, et al. : Effects of music therapy on behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing research reviews 2013; 12:628–641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Margallo-Lana M, Swann A, O’Brien J, et al. : Prevalence and pharmacological management of behavioural and psychological symptoms amongst dementia sufferers living in care environments. International journal of geriatric psychiatry 2001; 16:39–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Parnetti L, Amici S, Lanari A, et al. : Pharmacological treatment of non-cognitive disturbances in dementia disorders. Mechanisms of ageing and development 2001; 122:2063–2069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Profenno LA, Tariot PN: Pharmacologic management of agitation in Alzheimer’s disease. Dementia and geriatric cognitive disorders 2004; 17:65–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Locca J-F, Büla CJ, Zumbach S, et al. : Pharmacological treatment of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD) in nursing homes: development of practice recommendations in a Swiss canton. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association 2008; 9:439–448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Franco KN, Messinger-Rapport B: Pharmacological treatment of neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia: a review of the evidence. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association 2006; 7:201–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ford AH, Almeida OP: Management of depression in patients with dementia: is pharmacological treatment justified? Drugs & aging 2017; 34:89–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kales HC, Gitlin LN, Lyketsos CG: Assessment and management of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia. Bmj 2015; 350:h369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Qassem T, Tadros G, Moore P, et al. : Emerging technologies for monitoring behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia, IEEE, 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Husebo BS, Heintz HL, Berge LI, et al. : Sensing Technology to Facilitate Behavioral and Psychological Symptoms and to Monitor Treatment Response in People With Dementia. A Systematic Review. Frontiers in Pharmacology 2020; 10:1699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wallace B, El Harake TN, Goubran R, et al. : Preliminary results for measurement and classification of overnight wandering by dementia patient using multi-sensors, IEEE, 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kroll L, Böhning N, Müßigbrodt H, et al. : Non-contact monitoring of agitation and use of a sheltering device in patients with dementia in emergency departments: a feasibility study. BMC psychiatry 2020; 20:1–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blytt KM, Bjorvatn B, Husebo B, et al. : Effects of pain treatment on sleep in nursing home patients with dementia and depression: A multicenter placebo-controlled randomized clinical trial. International journal of geriatric psychiatry 2018; 33:663–670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Blytt KM, Husebo B, Flo E, et al. : Long-term pain treatment did not improve sleep in nursing home patients with comorbid dementia and depression: a 13-week randomized placebo-controlled trial. Frontiers in psychology 2018; 9:134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gibson RH, Gander PH: Monitoring the sleep patterns of people with dementia and their family carers in the community. Australasian journal on ageing 2019; 38:47–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Khan SS, Zhu T, Ye B, et al. : Daad: A framework for detecting agitation and aggression in people living with dementia using a novel multi-modal sensor network, IEEE, 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Belay M, Henry C, Wynn D, et al. : A Data Framework to Understand the Lived Context for Dementia Caregiver Empowerment, 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cohen-Mansfield J: Conceptualization of agitation: results based on the Cohen-Mansfield agitation inventory and the agitation behavior mapping instrument. International Psychogeriatrics 1997; 8:309–315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kaye J, Reynolds C, Bowman M, et al. : Methodology for establishing a community-wide life laboratory for capturing unobtrusive and continuous remote activity and health data. JoVE (Journal of Visualized Experiments) 2018; e56942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Au-Yeung WTM, Miller L, Beattie Z, et al. : Sensing a problem: Proof of concept for characterizing and predicting agitation. Alzheimer’s & Dementia: Translational Research & Clinical Interventions 2020; 6:e12079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hagler S, Austin D, Hayes TL, et al. : Unobtrusive and ubiquitous in-home monitoring: A methodology for continuous assessment of gait velocity in elders. IEEE transactions on biomedical engineering 2009; 57:813–820 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hayes TL, Hagler S, Austin D, et al. : Unobtrusive assessment of walking speed in the home using inexpensive PIR sensors, IEEE, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ranta JR, Aittokoski T, Tenhunen M, et al. : EMFIT QS heart rate and respiration rate validation. Biomedical Physics & Engineering Express 2019; [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kortelainen JM, Mendez MO, Bianchi AM, et al. : Sleep staging based on signals acquired through bed sensor. IEEE Transactions on Information Technology in Biomedicine 2010; 14:776–785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Figueiro M, Hamner R, Bierman A, et al. : Comparisons of three practical field devices used to measure personal light exposures and activity levels. Lighting Research & Technology 2013; 45:421–434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vahia IV, Kabelac Z, Hsu C-Y, et al. : Radio signal sensing and signal processing to monitor behavioral symptoms in dementia: A case study. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 2020; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hsu C-Y, Liu Y, Kabelac Z, et al. : Extracting gait velocity and stride length from surrounding radio signals, 2017 [Google Scholar]