Abstract

Background

Older people with multi-morbidities commonly experience an uncertain illness trajectory. Clinical uncertainty is challenging to manage, with risk of poor outcomes. Person-centred care is essential to align care and treatment with patient priorities and wishes. Use of evidence-based tools may support person-centred management of clinical uncertainty. We aimed to develop a logic model of person-centred evidence-based tools to manage clinical uncertainty in older people.

Methods

A systematic mixed-methods review with a results-based convergent synthesis design: a process-based iterative logic model was used, starting with a conceptual framework of clinical uncertainty in older people towards the end of life. This underpinned the methods. Medline, PsycINFO, CINAHL and ASSIA were searched from 2000 to December 2019, using a combination of terms: “uncertainty” AND “palliative care” AND “assessment” OR “care planning”. Studies were included if they developed or evaluated a person-centred tool to manage clinical uncertainty in people aged ≥65 years approaching the end of life and quality appraised using QualSyst. Quantitative and qualitative data were narratively synthesised and thematically analysed respectively and integrated into the logic model.

Results

Of the 17,095 articles identified, 44 were included, involving 63 tools. There was strong evidence that tools used in clinical care could improve identification of patient priorities and needs (n = 14 studies); that tools support partnership working between patients and practitioners (n = 8) and that tools support integrated care within and across teams and with patients and families (n = 14), improving patient outcomes such as quality of death and dying and satisfaction with care. Communication of clinical uncertainty to patients and families had the least evidence and is challenging to do well.

Conclusion

The identified logic model moves current knowledge from conceptualising clinical uncertainty to applying evidence-based tools to optimise person-centred management and improve patient outcomes. Key causal pathways are identification of individual priorities and needs, individual care and treatment and integrated care. Communication of clinical uncertainty to patients is challenging and requires training and skill and the use of tools to support practice.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12904-021-00845-9.

Keywords: Review, Uncertainty, Aged, Palliative care, Process assessment (health care), Patient outcome assessment, Patient care planning, Advance care planning, Communication

Introduction

People are living longer and increasingly die with multi-morbidities and frailty [1–4]. The last years of life for older people are often characterised by clinical uncertainty over recovery or continued deterioration leading to death. Clinical uncertainty is a challenging area of clinical care. It requires parallel planning and intervention to support recovery and to anticipate and plan for deterioration and dying [5]. Health and social care staff (practitioners) require expertise to communicate uncertainty with patients (including long term care residents) and families (including friends) and to manage multiple perspectives which are sometimes conflicting about treatment decisions, whilst ensuring that care is person-centred and aligned with the patient’s and family’s wishes and priorities [6, 7]. Poorly managed clinical uncertainty leads to poorer outcomes for patients and their family, including compromised quality of life [8].

Clinical uncertainty comprises multiple interlinked perspectives, such as the patient and practitioner [9–12] and levels such as the individual and service [13]. Studies have developed conceptual understanding for clinical care. Mishel [9–11] conceptualised uncertainty in illness as a clinical presentation that is ambiguous, complex with limited information and/or is unpredictable [10]. Goodman et al. (2015) pursued this understanding in care homes [13] identifying layers of treatment uncertainty arising for example from multi-morbidity, relationship uncertainty such as divergent priorities and service uncertainty such as workforce turnover. Etkind et al. [12] explored the views of patients to develop a typology of priorities in managing clinical uncertainty including level of engagement in decisions about care and treatment, tailored information to individual preferences and the time period an individual is focused.

Central to managing clinical uncertainty is person-centred care to align care and treatment with the patient’s and carer’s priorities and wishes. A person-centred tool is an instrument designed to support, facilitate or guide person-centred care or treatment and as such is a complex intervention. Examples of person-centred tools are patient-reported outcome measures to identify an individual’s priorities, symptoms or needs, or Advance Care Planning (ACP) tools to support patients in discussing and sharing their wishes for future care and treatment [14].

Managing clinical uncertainty for older adults with multimorbidity and frailty, is an important and complex area of clinical care, but no reviews have considered conceptually how using tools as complex interventions in clinical practice could support the management of clinical uncertainty and improve patient outcomes. This study aimed to develop a logic model by systematically identifying, appraising and synthesising the evidence on person-centred tools intended to support the management of clinical uncertainty for older people towards the end of life.

Methods

This is a mixed methods systematic review using a results-based convergent design [15] to inform the logic model. The logic model is intended to: describe the components of person-centred tools; depict and conceptualise the causal pathways (how using them changes care and impacts on effect) and linkages with the intended outcomes and describe and understand the context in which this occurs [16].

We used the following methods to develop a process-based iterative logic model [17]. We started with a conceptual framework of clinical uncertainty in older people with multi-morbidity and frailty, informed by conceptual understanding from Mishel, Goodman et al. and Etkind et al. [9–13] (Additional file 1 - conceptual framework of clinical uncertainty). This conceptual framework underpinned our search strategy and initial data analysis to inform the development of the logic model [17]. From the conceptual framework we identified three domains of clinical uncertainty that we aimed to address: 1) comprehensive assessment targeting complexity and ambiguity, 2) communication of clinical uncertainty to patients and family targeting lack of information and 3) continuity of care (care planning, ACP and communicating within and across teams) targeting unpredictability. The logic model was iteratively reviewed and refined, informed by research project meetings, project steering group meetings and emerging review findings [17].

The systematic review followed Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) (Additional file 2 - PRISMA checklist). The protocol was registered on PROSPERO (CRD42018098566).

Search strategy

The following databases were searched: IBSS (2000 - July 2018), Medline, PsycINFO and CINAHL, from year 2000 to December 2019 using a combination of MeSH terms and keyword terms. MeSH terms included “uncertainty” OR “disease progression” AND “chronic illness” OR “palliative care” OR terminal care AND “assessment” OR “outcome assessment” OR “care planning” OR “decision making” (Additional file 3 - full search strategy). The electronic search was supplemented by reference chaining and consulting experts in the field.

Eligibility criteria

Participants

Adults aged 65 years and over, living with advanced or life-limiting condition(s), including cancer and chronic noncancer conditions, and nearing end of life. Nearing end of life encompassed: the last 1–2 years of life through to death, or using services or facilities associated with advanced disease e.g. receiving palliative care, residing in a care home. At least half of individual study populations needed to be within the above definitions [18].

Interventions/tools

The intervention comprised: (i) person-centred tools to inform clinical assessment of conditions, including outcome measures to assess physical symptoms and/or psychosocial concerns, tools to assess multi-dimensional clinical constructs, such as frailty and function, and those that support identification of person-centred goals; (ii) tools to support integrated care within and across settings, including, but not limited to, care and contingency planning tools, pathways and decision-support tools; and (iii) tools to support communication in advanced conditions between health and social care practitioners, the patient, and/or their families.

To maintain the focus of person-centred tools, we excluded assessments of individual symptoms e.g. pain, diagnostic, prognostication or risk assessment tools such as risk of mortality. Out of scope were models of care delivery, training interventions and systems of tool delivery e.g. telemonitoring or telehealth.

Control

All control groups and those with no controls.

Outcomes

All outcomes were included. We included carer and practitioner outcomes when these were included with patient outcomes.

Study design

We included published qualitative, quantitative and mixed-methods studies. Studies included development and evaluation of tools for clinical care e.g. cognitive interviews, studies that evaluated tools in clinical care, including randomised and non-randomised trials, process evaluations and quality improvement studies. Unpublished grey literature studies were ineligible as considered insufficiently robust evidence because, for example, not subject to peer review. Psychometric evaluations and tool development studies without use in clinical care were excluded. Reviews, clinical guidelines, case studies, opinion pieces, conference abstracts, theses and dissertations were also excluded.

Other limits

English language and human subjects.

Study selection

All identified studies were managed using a reference management system (EndNote X9). One reviewer screened all titles and abstracts, and 10% of abstracts and titles were double-blind screened by a second reviewer (151 publications were double screened, 3 publications with divergence between assessors were reviewed by a third). Full text articles were reviewed by one reviewer and those with uncertain eligibility discussed with the full project team.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Data extraction tables were developed, piloted and refined following discussion with all investigators. Fields extracted are detailed in Tables 1 and 2, and specific data to inform the logic model including implementation requirements, causal pathways, and acceptability and feasibility for routine clinical care.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies

| Lead author, country, quality assessment | Family of tools | Name and description of tool | Domain of uncertainty | Study design | Study population | Research question/aim | Primary outcomes/results/ conclusions | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comprehensive assessment | Communication | Continuity of care | |||||||

| Dunckley [19], 2005, UK, 0.45 | POS |

Palliative care Outcome Scale (POS) The POS is a 10-item questionnaire covering physical and psychological symptoms; and spiritual, practical and emotional concerns. |

X | X | Qualitative study | Practitioners working in nursing homes or clinical hospices | To identify facilitators and barriers to implementing outcome measures. | Barriers to implementing POS included, a top-down decision-making approach, time-consuming tools, limited resources for data analysis and a lack of practitioner knowledge of the importance of using tools. Facilitators to successful implementation included practitioners being involved in implementation decisions and using a tool that can be adapted to clinical practice and organisational needs. | |

| Tavares [20], 2017, Brazil, 0.7 | X | X | Observational study | Patients admitted to a specialist palliative care unit. Mean age 77.5 years. | To implement the POS in a specialist palliative care inpatient unit in daily practice. | POS is feasible to implement and improves quality of care. Pain was particularly improved between timepoints. | |||

|

Kane [21], 2018, UK, 0.6 Kane [22], 2017, UK,0.9 |

Integrated Palliative care Outcome Scale (IPOS) The IPOS has 10 questions with two open questions covering patients’ main concerns and symptoms, respectively, and a five-point Likert scale (0–4) accompanying common symptoms, patient and family distress, existential well-being, sharing feelings with family, information available and practical concerns. |

X | X | X | A parallel, mixed methods embedded study | Advanced chronic heart failure patients in a nurse-led chronic heart failure disease management clinic. Mean age 75 years. Plus 4 nurses. | To examine the feasibility and acceptability of using a patient reported outcome measure and its potential to influence patient perceptions of care. | IPOS was feasible and acceptable to patients and practitioners for use in clinical care and research. IPOS also allowed patients to become more engaged in their clinical care and highlight their unmet needs. | |

| Ellis-Smith [23], 2017, UK, 0.85 |

Integrated Palliative care Outcome Scale for Dementia (IPOS-Dem) A 28-item questionnaire with all questions, apart from the first, rated on a 5-point scale. |

X | X | X | A multi-method qualitative study | Care home residents with dementia, family members, care home practitioners, GPs and district nurses. | To examine the content validity, acceptability and comprehension of IPOS-Dem for routine use in long-term care settings for people with dementia and to refine the tool. |

IPOS-Dem is a comprehensive and acceptable way to detect symptoms and problems for those with dementia. It is also acceptable as a carer-reported measure. Refinements have been made to maximise caregiver expertise. |

|

| Ellis-Smith [24], 2018, UK, 0.9 | A qualitative study with an embedded quantitative component | Care home residents with dementia, family members, care home practitioners, GPs and district nurses. | To explore the mechanisms of action, feasibility, acceptability and implementation requirements of a the IPOS-Dem |

Key mechanisms of action were identified, and a theoretical model was developed. IPOS-Dem was shown to be acceptable and feasible. Assessment and management of symptoms and concerns is supported by IPOS-Dem. |

|||||

|

Salisbury [25], 2018, UK, 0.86 Mann [26], 2019, UK, 0.85 Thorn [27] 2020, UK, 0.85 |

3D Approach |

3D Approach Replaces disease specific reviews of each health condition with one 6-montly comprehensive multidisciplinary review, including medication review. |

X | X | X | A pragmatic cluster-randomised controlled trial | Patients of participating GP surgeries with at least 3 chronic conditions. Mean age 71 years. | To implement, at scale, a new approach to managing patients with multimorbidity in primary care and to assess its effectiveness. |

The 3D intervention did not improve patients’ quality of life. Both implementation and intervention failure were cited as reasons for failure. Cost effectiveness was equivocal. |

|

Forbat [28], 2019, Australia, 0.73 Liu [29], 2020, Australia, 0.93 |

Palliative care needs rounds Needs rounds are monthly clinical meetings that are conducted at the care facility that integrate a specialist palliative care perspective into nursing home care. |

X | X | A prospective stepped-wedge cluster randomised control trial | Care home residents. Mean age 85 years. Care home practitioners interviewed. | To determine whether a model of care providing specialist palliative care in care homes, called Specialist Palliative Care Needs Rounds, could reduce length of stay in hospital. |

The primary outcome was length of stay in acute care. Secondary outcomes included number and cost of hospitalisations. Palliative care needs rounds reduced the number of hospitalisations and length of stay. |

||

| Forbat [30], 2018, Australia, 0.5 | Development of checklist | A grounded theory ethnography | To describe the activities, thought processes and activities of practitioners that are generated within and from needs rounds. To develop a model that explains what occurs in needs rounds and distil checklist from this. To finalise the checklist. | The checklist was suitable to support the integration of specialist palliative care into residential care. | |||||

| Waller [31], 2012, Canada, 0.91 | Needs Assessment Tool |

Needs Assessment Tool: Progressive Disease Cancer (NAT: PD-C) One-page practitioner completed questionnaire |

X | Interrupted time series trial | Advanced cancer patients recruited from medical oncology, radiation oncology, and haematology outpatient clinics with an average age of 67 years. | To assess the impact of the systematic and ongoing use of the Guidelines and NAT: PD-C on patient outcomes including level of need, quality of life, anxiety, and depression. | The NAT:PD-C reduces health system and information needs, and patient care and support needs. | ||

| Janssen [32], 2019, The Netherlands, 0.73 |

Needs Assessment Tool: Progressive Disease Heart Failure (NAT: PD-HF) One-page practitioner completed questionnaire |

X | Mixed methods | Outpatients with diagnosis of chronic heart failure. Average age 84.4 (SD: 7.7) years. | To translate and study the feasibility and acceptability of the NAT:PD-HF. | The NAT:PD-HF identified palliative care needs in all participants, and triggered action to address these in half. Palliative care communication skills training is required when implementing this tool. | |||

| Actcherberg [33], 2001, The Netherlands, 0.86 | Resident Assessment Instrument |

Resident Assessment Instrument (RAI) The RAI consists of a structured screening questionnaire [the Minimum Data Set (MDS)], an algorithm that links the information from the MDS to certain important problem areas, and triggers protocols for these problem areas if required. |

X | X | Non randomised controlled trial | Residents admitted for long term care in a somatic ward. Average age 78.6 years | Does the implementation of the RAI method improve the quality of the co-ordination of care in Dutch nursing homes? | Improvements in case history, care plan, end of shift reporting, communication, patient allocation and patient report in the RAI group. RAI has the potential to improve the quality of co-ordination of care in nursing homes | |

| Gestsdottir [34], 2015, Iceland, 0.91 |

InterRAI Palliative Care The InterRAI PC is divided into 16 domains: demographics, health conditions, oral and nutritional status, skin condition, cognition, communication, mood and behaviour, psychosocial wellbeing, physical functioning, urinary and bowel continence, medications, treatments and procedures, responsibility/directives, social relationships, discharge or death, and assessment information. |

X | Longitudinal | Patients using the services of the palliative consultation team and hospital general and palliative care units | To assess the symptoms and functional status of patients at the point of admission to specialised palliative care in Iceland and to investigate whether symptoms and functional status change over time. Also, to examine the difference in symptoms and functional status between care settings. A secondary aim was to participate in the development of interRAI PC assessment tool |

Symptom burden and functional loss were significantly experienced by patients from admission to discharge or death. Symptoms indicating progressive deterioration also increased in frequency and severity. Physical and cognitive function decreased at all levels. Inpatients had more symptoms and experienced more functional decline than home-care patients. The interRAI PC version 8 supported capture of important clinical information and monitoring changes over time. |

|||

| Hill [35], 2002, New Zealand, 0.6 | The Missoula-VITAS Quality of Life Index (MVQOLI) |

The Missoula-VITAS Quality of Life Index (MVQOLI) The Missoula-VITAS Quality of Life Index (MVQOLI) is a 25-item patient-centred index that weights each of five QOL dimensions by its importance to the respondent. |

X | A pre-test/post-test quasi-experimental design | 72 hospice patients and 10 nursing practitioners. Ages ranging from 20 to 89 years old. | To examine the concept and measurement of quality of life (QOL) in terminally ill patients and how QOL can be improved within a hospice setting |

Providing nurses with access to information on the patient’s QOL perspective better prepares them to meet the patient’s QOL needs. This results in clinically significant improvements to patient QOL. |

||

| Schwartz [36], 2005, USA, 0.77 |

Missoula-VITAS Quality of Life Index - Revised (MVQOLI-R) As above, without the weighting. |

X | X | Psychometric evaluation and intervention study | End-stage renal disease patients and hospice, or long-term care facility, patients. Mean age 66.3 years. | To evaluate the MVQOLI-R from both psychometric and clinimetric perspectives. | The MVQOLI-R has clinical utility as a patient QOL assessment tool and may support communication between patients and clinicians. | ||

| Rockwood [37], 2000, Canada, 0.79 | Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment |

CGA and Goal Attainment Scale (GAS) Unspecified group of tools used together in CGA. GAS is used to record patient goals and the achievement of those goals. |

X | X | Randomized, controlled, single-blinded trial | Frail patients living in a rural community. Mean ages 82.2 and 81.4 years. | Testing of the CGA in the common, but constrained, environment of frail older patients without nearby access to specialized care. | Intervention group more likely to achieve their goals. No change or difference in function, QOL, survival or time to institutionalisation. | |

|

Parlevliet [38], 2012, The Netherlands 0.86 |

CGA: Comprising of: Charlson’s comorbidity index; Activities of Daily Living; Instrumental Activities of Daily Living; MMSE; SDGS; SNAQ; VAS; EuroQol-6D; IQCOD-SF; NPI-q; CAM; EDIZ; De Jong-Gierveldschaal |

X | Cross sectional comparative and feasibility study | Patients with end stage renal disease aged 65 years or above, either receiving peritoneal dialysis or haemodialysis in hospitals with dialysis facilities |

To perform a systematic CGA to investigate somatic, psychological, functional and social function in a group of older dialysis patients. Secondly, we aimed to place our findings in a broader perspective by comparing our group to a population of elderly cancer patients who likewise suffered from an end-stage chronic progressive disease. Finally, we asked the multidisciplinary team for their opinion on the feasibility of the systematic CGA and the relevance of its outcome. |

Geriatric conditions were highly prevalent among elderly dialysis patients and prevalence’s were comparable in both intervention and control populations. The CGA was feasible for use of recognition of conditions and overburdened carers. |

|||

|

Basic [39], 2002, Australia 0.86 |

CGA Comprising of: Activities of Daily Living; Instrumental Activities of Daily Living; MMSE; GDS; SSI; Waterlow Risk Assessment Scale |

X | Observational study | Older people presenting to the emergency department who were considered at high risk of admission but who were not severely ill. Mean age 79.4 years | To evaluate the ability of the nurse to assess high risk elderly patients comprehensively. A secondary aim was to explore patient characteristics associated with referral to community aged care services from the emergency department. | A single nurse working in a busy emergency department can successfully identify patients with increased care needs, and direct high-risk patients to existing services. | |||

|

Mariano [40], 2015, Canada 0.73 |

Geriatric assessment | Geriatric assessment (unspecified) | X | Pilot study | Cancer patients. Mean age 77 years. Hospitals | To evaluate the feasibility of GA in this frail, historically difficult-to-study population. Secondary objectives were to describe the level of deficits detected on GA, to assess whether hospital-based clinicians recognized and addressed these deficits, and to describe hospital-based outcomes including length of stay, discharge disposition, and 30-day readmission rates |

GA was feasible in this population. Hospitalized older cancer patients experience more functional and psychosocial issues. Clinical recognition and management of these issues was poor. GA tools can be used to inform guide referrals to appropriate services. |

||

|

Jadczak [41], 2017, Australia 0.59 |

Geriatric Assessment Comprising of: FRAIL screen; CCI; SF-36; TMT; MNA-SF; RCS; Lawton IADL | X | Observational study | Patients from a Geriatric Evaluation and Management Unit (GEMU) screened pre-frail or frail on the FRAIL Screen. Mean age 85.37 years. | To determine the feasibility of standardised geriatric assessments and standard physical exercises in hospitalised pre-frail and frail older adults | The FRAIL Screen, MNA-SF, Rapid Cognitive Screen, Lawton iADL and the physical exercises were deemed to be feasible with only minor comprehension, execution and safety issues. The TMT was not considered to be feasible and the SF-36 should be replaced by its shorter form, the SF-12. | |||

| Pepersack [42], 2008, Belgium, 0.67 |

Minimum Geriatric Screening Tools (MGST) Battery of tools including: ADL; IADL; CSDD; Socios Scale; MUST; pain indicators; ISAR |

X | Prospective observational survey | Patients attending an acute geriatric unit, mean age 83.3 years. | The aims of this project were: 1) to assess the feasibility of a MGST within the teams of Belgian geriatric units; 2) to assess the efficacy of a MGST on the detection rate of the geriatric problems; and 3) to analyse quality variables within the data collected. | MGST leads to better assessment of geriatric domains (functional, continence, cognition, depression, nutrition, pain, social), apart from falls. | |||

| Cheang [43], 2014, Australia, 0.72 | Advance Care Planning |

ACP screening interviews Guided interview |

X | Cross-sectional | Patients ages 80 years or over, who have been admitted for at least 48 h to an adult medical/surgical ward | To assess the prevalence of advanced care documents and documented medical orders regarding end-of-life care in the medical record of elderly inpatients and to explore the feasibility and acceptability of an advanced care planning screening interview. | Advance Care Directives and correct documentation of suitable decision-maker were uncommon in the medical records. The ACP screening interview appears feasible and acceptable and may be a useful tool for identifying suitable decision-maker and patients willingness to discuss ACP further. | ||

|

Silvester [44] 2013, Australia 0.68 |

Advance Care Plan Two-sided questionnaire asking about values and beliefs, unacceptable health condition, specific treatments wanted and unwanted. |

X | Audit of pre-existing documentation and pilot study | No patients recruited. | The development of the aged care specific Advance Care Plan template, the pre-implementation quality of ACP documents and the performance of the newly developed Advance Care Plan template | Standardised procedures and documentation are needed to improve the quality of processes, documents and outcomes of ACP. | |||

|

Miller [45], 2019, Australia 0.75 |

Advance Care Planning GP completes referral to GPN including health and social information. GPN conducts ACP discussion using an Advance Care Planning workbook and Advance Care Directive template was used to guide discussions and to record the patient’s wishes if required. |

X | Qualitative interviews | Patients of participating GP surgeries. Mean age 81 years. | To understand how patients experienced involvement in advanced care planning in the general practice setting when common barriers to uptake were addressed and what impact this has on patients and their families. | GPNs are able to hold ACP conversations with patients when provided with training and support. GPNs involvement in these conversations can benefit patients. Some patients may feel uncomfortable communicating results of ACP conversations with family. | |||

|

Sudore [46], 2013, USA 0.9 |

Advance Care Planning Engagement survey Survey with two sections containing 31 items in ‘process measures’ and 18 items in ‘action measures’. |

X | Development and psychometric evaluation | Patients recruited from hospitals, outpatient clinics and nursing homes. Mean age 69.3 years. | To develop and validate a survey designed to quantify the process of behaviour change in the advance care planning process. | The Advance Care Planning Engagement Survey measuring behaviour change and multiple advance care planning actions demonstrated good reliability and validity. | |||

|

Bristowe [47], 2015, UK 0.85 |

The AMBER Care Bundle |

The AMBER Care Bundle This intervention has an algorithmic approach and is intended to encourage the clinical team to develop and document a clear medical plan and consider anticipated outcomes and resuscitation and escalation status; this is revisited daily. |

X | X | Mixed methods observational study | Patients in the acute hospital setting who are deteriorating, clinically unstable, with limited reversibility and at risk of dying in the next 1–2 months. Mean age 77 years. | Aims to examine the experience of care supported by the AMBER care bundle compared to standard care in the context of clinical uncertainty, deterioration and limited reversibility | Patients in the intervention group appeared to have higher awareness of prognosis. This does not translate to better quality communication and information was judged less easy to understand. | |

| Koffman [48], 2019, UK, 0.82 | Randomised controlled trial | Hospital inpatients. 38.5% were aged 60–79 years old, 46.2% were aged over 80 years old. | To investigate the feasibility of a cluster RCT of the AMBER care bundle. | The cluster RCT was feasible. However, optimal recruitment was prevented by impracticalities in the fundamental issues in operationalising the intervention’s eligibility criteria. | |||||

| McMillan [49], 2011, USA, 0.86 | Tools used together as a package |

Patient instruments Palliative Performance Scale (PPS) Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale-Revised (MSAS) Hospice Quality of Life Index-14 (HQLI-14) Instruments for Both Patients and Caregivers Center for Epidemiological Study-Depression Scale (CES-D) Spiritual Needs Inventory Short Portable Mental Status Questionnaire |

X | Clinical trial | Patients newly admitted to hospice care and their family caregivers. Patient mean age 72.66 years, caregiver mean age of 65.37 years. | To determine the efficacy of providing systematic feedback from standardized assessment tools for hospice patients and caregivers in improving hospice outcomes compared to the usual clinical practice |

Depression scores were improved in the intervention group. Standard care received was so good that the overall quality of life improved as a result. This prevented improvement in other variables. |

||

| Gilbert [50], 2012, Canada, 0.55 |

Edmonton Symptom Assessment Symptom (ESAS), Palliative Performance Scale and Advance Care Plan |

X | X | Mixed methods quality improvement | Cancer patients receiving community palliative care | The project involved 1) implementation of the ESAS for symptom screening, 2) use of “rapid-cycle change” quality improvement processes to improve screening and symptom management, and 3) improvements in integration and access to palliative care services. | The Provincial Palliative Care Integration Project demonstrated that by using rapid-cycle change and collaborative approaches, symptom screening and responses can be improved. Improvements can occur in the long and short term but require changes in system design and changes in clinical practice culture. | ||

| Mercandante [51], 2019, Italy, 0.82 |

Patient Dyspnea Goal, Patient Dyspnea Goal Response and Patient Global Impression Patient Dyspnea Goal is an assessment tool to tailor symptom management, providing a therapeutic ‘target’. Patient Dyspnea Goal Response is the achievement of the goal. Global impression is global rating-of-change scale that assesses patients’ subjective response based on the individual feeling of improvement or deterioration. |

X | X | Secondary analysis | Advanced cancer patients admitted to palliative care units. Mean age 68.2 years. | To characterize the Patient Dyspnea Goal and Patient Dyspnea Goal Response, and Patients Global Impression after 1 week of a comprehensive symptom management. The secondary aim was to find possible factors influencing the clinical responses assessed as Patient Dyspnea Goal Response and Patient Global Impression. | Patient Dyspnea Goal Response and Patient Global Impression seem to be relevant for evaluating the effects of a comprehensive management of symptoms, assisting decision making process. | ||

| Cox [52], 2011, UK, 0.5 |

Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale (ESAS) and the Euro-QoL (EQ-5D) Technologies HealthHUB (held by patients) and CareHUB (held by clinicians) used as prompts to complete ESAS and EQ-5D questionnaires to assess symptoms and QoL respectively. |

X | X | Mixed methods | Hospice patients with a diagnosis of lung cancer | This study had two aims: [1] to test and evaluate the support provided to patients by the computerized assessment tool and [2] to determine the clinical acceptability of the technology in a palliative care setting. |

Clinicians acknowledged patient and practice benefits of computerised patient assessment but highlighted the importance of clinical intuition over standardised assessment. While clinicians were positive about palliative care patients participating in research, they did indicate concerns around age and potential for rapid deterioration. The contribution of e-technology needs to be prompted, particularly in its potential to improve patient outcomes and experience, to encourage acceptance of its use in palliative care. |

||

| Hockley [53], 2010, UK, 0.82 | Liverpool Care Pathway and Gold standards framework | X | X | Evaluation | Nursing home residents aged 66–103 years. 51% of residents had 3 or more diagnoses. | Using tools to help improve end-of-life care in care homes | There was a highly statistically significant increase in use of Do Not Attempt Resuscitation (DNAR) documentation, advance care planning and use of the LCP. An apparent reduction in unnecessary hospital admissions and a reduction in hospital deaths post-study were also found. | ||

| Jennings [54], 2016, USA, 0.95 |

Physician Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment (POLST) Legal document indicating preferences for life sustaining treatment |

X | Observational study | Residents in nursing facilities with a mean age of 78 years. | To evaluate the use of POLST among California nursing home residents, including variation by resident characteristics and by nursing home facility. | State-wide nursing home data show broad uptake of POLST in California without racial disparity. However, variation in POLST completion among nursing homes indicates potential areas for quality improvement. | |||

| Krumm [55], 2014, Germany, 0.8 |

Minimal Documentation system for Palliative Care (MIDOS) One-page symptom assessment tool |

X | X | Qualitative multiple-unit study | Nurses and care assistants from specialist dementia units | To describe health professionals’ experiences of assessing the symptoms of people with dementia using a cancer-patient-oriented symptom-assessment tool from a palliative care context | The MIDOS tool was perceived as a helpful and valuable. Practitioners expressed some concerns regarding the subjective nature of perceiving symptoms and clinical decision making. The use of tools such as this has the potential to enhance the quality of palliative care in dementia care. | ||

| Landi [56], 2001, Italy, 0.93 | Minimum Data Set for Home Care (MDS-HC) | X | X | Single blind randomized controlled trial | Older people living in the community receiving home care services | To test the effectiveness—in standardized home care programmes with case management—of a new, internationally validated assessment instrument, the MDS-HC | The intervention group used more at home services, were sent to hospital later and less often following assessment using MDS-HC assessment, therefore, reducing costs. MDS-HC also indicated improvements in physical and cognitive function in the intervention group. | ||

| Ratner [57], 2001, USA, 0.55 |

The Kitchen Table Discussion Formally structured social work visits at patients’ homes to discuss end-of-life issues, with communication of results to home health nurses and attending physicians. |

X | Case series | Patients with a serious or life-threatening illness with a life expectancy of less than 2 years receiving home care. 75% aged 65 years and older. | To determine whether home health agency patients’ preferences to die at home can be honoured following a structured, professionally facilitated advance-care planning (ACP) process provided in the home. | Patients were willing to take part in ACP discussions at home. Most patients preferred to die at home. Facilitating ACP among such patients and their families was associated with end-of-life care at home. Use of hospice services was common following ACP in this population. | |||

| Schamp [58], 2006, USA, 0.68 |

Pathways Tool A documentation tool that captures both present and advance directives in a framework of “pathways,” blending goals of care with typical procedure-oriented directives. |

X | Pre and post observational study design | Elderly, frail and medically complex population with an average of 8 chronic medical conditions living in the community. More than 133, of the 160 patients, were over the age of 65 years. | To determine the effect of using the Pathways Tool upon the rates of completion of health care wishes and whether the distinction of “present” versus “advance” directives might be associated with differing qualitative choices expressed | The Pathways Tool was associated with increased completion of health care wishes, preferences toward less invasive levels of care at life’s end, and increased compliance with participants’ wishes and deaths at home. | |||

| Zafirau [59], 2012, USA, 0.64 |

Resident Change in Condition Assessment/Transfer Form The form provides background information on patient’s health history and other information helpful and necessary for receiving hospitals. It also records the presence of advanced directives. If a DNR order exists, a copy is attached directly to the form. |

X | Pre and Post test intervention evaluation | Patients in long term care facilities transferring to the emergency department, mean ages 72.8 and 76 years. | To test the efficacy of a standardized form used during transfers between long-term care facilities and the acute care setting | Communication between LTCFs of advanced directives was improved by use of the standardised transfer form. The form may also have increased admissions to the palliative care unit. | |||

| McGlinchey [60], 2019, UK, 0.8 |

Serious Illness Conversation Guide Guide to support clinician’s communication with patients regarding current and future care and to promote shared decision making |

X | X |

Stage 1: Nominal Group Technique Stage 2: Cognitive Interviews Stage 3: Stakeholder review and consensus |

Stage 1: Medical oncologists, palliative care and communication skills experts. Stage 2: Lay representatives Stage 3: Stakeholders made up of lay members and health service practitioners and researchers. |

To explore the ‘face validity’, applicability and relevance of the clinical tool, the Serious Illness Conversation Guide, to explore whether adaptations were required for the UK before its use in the pilot. | Interviews indicate acceptance from practitioners with some considerations. Use of the guide has the potential to benefit patients, facilitating a ‘person-centred’ approach to these important conversations, and to provide a framework to promote shared decision making and care planning. | ||

| Mills [61] 2018, Australia, 0.55 |

Goals-of-Care form A one-page document used to guide and record discussions between clinicians and patients around care preferences. |

X | X | A prospective mixed methods study | 108 forms were available from hospital inpatients. Median age 91 years. 16 doctors were interviewed. | To evaluate the utility to doctors of a form specifically designed to guide and document Goals of Care discussions at point of care. A secondary aim was to collect data on the length of GOC conversations and documentation. | Having a Goals-of-Care form in emergency medicine is supported. However, the ideal contents of the form were not determined. | ||

| Bouvette [62], 2002, Canada, 0.4 |

Pain and Symptom Assessment Record (PSAR) Two-sided questionnaire. |

X | X | Mixed methods | Palliative care patients in acute care institutions and community palliative care and oncology services, such as hospices and nursing agencies | To determine the feasibility of implementing the Pain and Symptom Assessment Record (PSAR) to assess the pain and symptoms of palliative care patients in a variety of settings | Based on the results from this study, the tool has been modified and is currently utilized in a variety of settings. | ||

Quality rating: < 0.60 = low; ≥0.60–0.79 = moderate; ≥0.80 = high

ACP Advance Care Plan (or planning), ADL Activities of Daily Living, CAM Confusion Assessment Method, CGA Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment, CCI Charlson Comorbidity Index, CES-D Center for Epidemiological Study-Depression Scale, CHF Chronic heart failure, CSDD Cornell Scale for Depression in Dementia, DNAR Do Not Attempt Resuscitation, EDIZ Experienced Burden of Informal Care, EQ-5D EuroQol-5D, ESAS Edmonton Symptom Assessment Symptom, FRAIL screen Fatigue, Resistance, Ambulation, Illness and Loss of weight screen, GA Geriatric assessment, GAS Geriatric Attainment Scale, GDS Geriatric Depression Scale, GP general practitioner, GOC Goals Of Care, GPN general practitioner nurse, HQLI-14 Hospice Quality of Life Index-14, IQCOD-SF Informant Questionnaire Cognitive Decline – Short Form, InterRAI PC Residents Assessment Instrument - Palliative care, IPOS Integrated Palliative care Outcome Scale, IPOS-Dem Integrated Palliative care Outcome Scale for Dementia, ISAR Identification of Seniors at Risk, (Lawton) IADL (Lawton) Instrumental Activities of Daily Living, LCP Liverpool Care Pathway, LTCF Long Term Care Facility, MDS-HC Minimum Data Set for Home Care, MGST Minimum Geriatric Screening tool, MIDOS Minimal Documentation system for Palliative Care, MMSE Mini Mental State Examination, MNA-SF Mini Nutritional assessment – short form, MSAS Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale-Revised, MUST Malnutrition Universal Screening Tool, MVQOLI (−R) The Missoula-VITAS Quality of Life Index (−Revised), NAT: PD-C Needs Assessment Tool: Progressive Disease – Cancer, NAT: PD-HF Needs Assessment Tool: Progressive Disease – Heart Failure, NPI-q Neuropsychiatric Inventory Questionnaire, POLST Physician Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment, POS Palliative care Outcome Scale, PPS Palliative Performance Scale, PROM Patient reported outcome measure, PSAR Pain and Symptom Assessment Record, QOL Quality of Life, RCS Rapid Cognitive Screen, RCT Randomised Controlled Trial, SD Standard deviation, SF-36 Short Form survey, SNAQ Short Nutritional Assessment Questionnaire, SSI Social Support Instrument, TMT Trail Making Test, VAS Visual Analogue Scale

Table 2.

Evidence of effectiveness

| First author (country), study design and quality rating* | N | Tool | Domain of uncertainty | Outcome measured and results | Results and Interpretation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comprehensive Assessment | Communication | Continuity of care | |||||

| QUALITY OF LIFE | |||||||

| Quality of life | |||||||

|

Hill, 2002 [35] New Zealand A pre-test/post-test quasi-experimental design 0.54 |

N = 72 | Missoula-VITAS Quality of Life Index (MVQOLI) | x |

MVQOLI - Overall: mean (SD) Control T1: 24.11 (33.70) Control T2: 35.00 (40.10) (ns) Intervention T1: 30.88 (41.88) Intervention T2: 47.41 (39.22) (p < 0.001) Between group, reported not significant |

No effect between intervention and control group Within group improvement in intervention |

||

|

McMillan, 2011 [49] USA RCT 0.86 |

N = 709 | Package of tools with feedback of results to care team | x |

HQLI - Model term: Estimate (SE), p-value Intercept: 102.33 (1.07), p < 0.001 Group: 1.65 (1.30), p = 0.206 Time: 0.29 (0.08), p < 0.001 Group x time: 0.03 (0.12), p = 0.811 |

No effect between intervention and control group Within group improvement in intervention |

||

|

Salisbury, 2018 [25] UK Cluster RCT 0.86 |

N = 1546 | 3D approach | x | x | x |

EQ-5D-5L – unadjusted mean (SE) Intervention: 0.533 (0.012) Control: 0.504 (0.012) Adjusted difference in means (95% CI): 0.00 (− 0.02–0.02) |

No effect between intervention and control |

|

Waller, 2012 [31] Canada Interrupted time series trial 0.91 |

N = 114 | Needs Assessment Tool: Progressive Disease-Cancer (NAT:PD-C) | x |

EORTC QLQ-C30 Mean quality of life score (0–100) 6 months pre and 6 months post intervention: T-3: 64.5 (p < 0.05), T-2: 61.2, T-1: 61.2 T0: 58.0, T1: 57.5, T2: 56.5, T3: 57.5 |

No effect | ||

| Quality of death and dying | |||||||

|

Liu, 2019 [29] Australia Stepped Wedge RCT 0.93 |

N = 1700 | Palliative Care Needs Rounds Checklist | x | x |

QODD – mean (SD) Intervention: 72.4 (13.0) Control: 69.1 (13.6) Treatment effect (95% CI): 8.1 (3.8–12.4) |

Effective | |

| Health status | |||||||

|

Rockwood, 2000 [37] Canada RCT 0.79 |

N = 182 | CGA and Goal Attainment Scale (GAS) | x | x |

Clinician’s global assessment - Proportion improved Intervention: 39/85 Control: 15/80 p = 0.001 |

Effective | |

|

Janssen, 2019 [32] The Netherlands Pre-test/post-test pilot study 0.73 |

N = 17 | Dutch Needs Assessment Tool: Progressive Disease – Heart Failure (NAT:PD-HF) | x |

Health status (MLHFQ) at baseline and 4 months: p = 0.04 |

Worsening effect | ||

| Symptom control | |||||||

|

Tavares, 2017 [20] Brazil Observational study 0.7 |

N = 317 |

Palliative Outcome Scale/Palliative Outcome Scale-Symptoms (POS/POS-S) |

x | x |

POS – Number and percentage of patients scoring moderate or high (≥2) at T0 with any improvement at T1 Pain: n = 10/11 (91%), p = 0.01 Other symptoms: n = 7/11 (64%), p = 0.03 |

Effective | |

|

POS – Number and percentage of patients scoring moderate or high (≥2) at T0 with any improvement at T1 Anxiety: n = 5/17 (29%), p = 0.35 Family anxiety: n = 3/20 (15%), p = 0.73 Information: n = 1/1 (100%) Support: n = 1/1 (100%) Depression: n = 2/5 (40%), p = 0.18 Self-worth: n = 1/4 (25%), p = 1.00 Time wasted: n = 3/3 (100%), p = 0.10 Personal affairs: n = 0/2 (0%), p = 1.00 |

No effect | ||||||

|

Modified POS-S - Percentage of patients scoring moderate or high (≥2) at T0 with any improvement at T1 Pain: n = 45/51 (88%), p < 0.001 Shortness of breath: n = 42/50 (84%), p < 0.001 Poor appetite: n = 18/42 (42%), p = 0.02 Constipation: n = 24/31 (77%), p < 0.001 Mouth problems: n = 17/25 (68%), p = 0.00 Drowsiness: n = 45/83 (54%), p < 0.001 Anxiety or agitation: n = 31/49 (63%), p < 0.001 Nausea/vomiting: n = 12/15 (80%), p = 0.00 Insomnia: n = 12/15 (80%), p = 0.01 Diarrhoea: n = 7/8 (88%), p = 0.01 |

Effective | ||||||

|

Ellis-Smith, 2018 [24] UK Single arm mixed methods feasibility and process evaluation 0.9 |

N = 30 | Integrated Palliative care Outcome Scale – Dementia (IPOS-Dem) | x | x | x |

IPOS-Dem - Mean (SD) Baseline total score: 15.47 (10.51) Final time point total score: 15.82 (10.94) |

No effect |

|

Gestsdottir, 2015 [34] Iceland Prospective longitudinal 0.91 |

N = 81 | Inter Resident Assessment Instrument - Palliative Care (InterRAI-PC) | x |

InterRAI-PC - Mean rank T1, T2, T3, X2, p-value Fatigue 1.99, 1.93, 2.08, 3.783, p = 0.151 Pain frequency 1.95, 1.89, 2.16, 4.866, p = 0.088 Pain strength 1.91, 1.94, 2.15, 4.071, p = 0.131 Difficulty sleeping 2.02, 1.88, 2.10, 3.957, p = 0.138 Nausea 2.16, 1.92, 1.93, 6.7, p = 0.035 Constipation 2.03, 1.91, 2.06, 1.694, p = 0.429 Oedema 1.90, 2.04, 2.06, 4.825, p = 0.090 Change in usual sleeping patterns 2.07, 1.87, 2.05, 3.206, p = 0.201 Sadness 1.98, 1.92, 2.09, 2.341, p = 0.310 Reduced social interaction 1.98, 1.88, 2.14, 4.200, p = 0.122 |

No effect | ||

|

InterRAI-PC - Mean rank T1, T2, T3, X2, p-value Loss of appetite 1.96, 1.83, 2.21, 11.346, p = 0.003 Insufficient nutritional intake 1.93, 1.84, 2.23, 14.510, p = 0.001 Shortness of breath with exertion 1.96, 1.87, 2.16, 10.393, p = 0.006 Dry mouth 1.83, 1.99, 2.18, 12.797, p = 0.002 |

Worsening symptoms | ||||||

|

Janssen, 2019 [32] The Netherlands Pre-test/post-test pilot study 0.73 |

N = 17 | NAT:PD-HF | x |

Symptom distress (ESAS) score at baseline and 4 months: p = 0.78 |

No effect | ||

| Illness burden | |||||||

|

Salisbury, 2018 [25] UK Cluster RCT 0.86 |

N = 1546 | 3D approach | x | x | x |

Self-rated health of good or better - n/N (%) Intervention: 242/642 (38%) Control: 230/631 (36%) Adjusted odds ratio (95% CI): 0.845 (0.67–1.05) |

No effect |

|

Bayliss measure of illness burden - Mean (SD) Intervention: 16.7 (11.6) Control: 18.4 (12.9) Adjusted beta-coefficient (95% CI): −0.64 (−1.54–0.27) |

No effect | ||||||

| Needs | |||||||

|

Waller, 2012 [31] Canada Interrupted time series trial 0.91 |

N = 114 | NAT: PD-C | x |

Supportive Care Needs Survey and spiritual domain of NAT: PD-C - Percentage of people reporting at least one moderate or high need T0: 64%, T1: 61%, T2: 51%, T3: 52% (z = 1.73, p = 0.08) |

No effect | ||

| Goal Attainment | |||||||

|

Rockwood, 2000 [37] Canada RCT 0.79 |

N = 182 | CGA and GAS | x | x |

GAS at 3 months Intervention: Total GAS = 46.4 ± 5.9, Outcome GAS = 48.0 ± 6.6 Control: Total GAS = 38.7 ± 4.1, Outcome GAS = 40.8 ± 5.6 p < 0.001 |

Effective | |

| Psychological/spiritual wellbeing | |||||||

|

McMillan, 2011 [49] USA RCT 0.73 |

N = 709 | Package of tools with feedback of results to care team | x |

CES-D - Model term: Estimate (SE), p-value Intercept: 4.51 (0.11), p < 0.001 Group: 0.01 (0.13), p = 0.929 Time: −0.02 (0.01), p = 0.23 Group x time: − 0.03 (0.01), p = 0.027 |

Effective | ||

|

MSAS distress - Model term: Estimate (SE), p-value Intercept: 1.99 (0.06), p < 0.001 Group: −0.08 (0.07), p = 0.238 Time: − 0.01 (0.01), p = 0.628 Group x time: 0 (0.01), p = 0.991 |

No effect | ||||||

|

Spiritual Needs Inventory - Model term: Estimate (SE), p-value Intercept: 1.67 (0.10), p < 0.001 Group: −0.23 (0.12), p = 0.062 Time: − 0.02 (0.09), p = 0.058 Group x time: 0.02 (0.01), p = 0.158 |

No effect | ||||||

|

Salisbury, 2018 [25] UK Cluster RCT 0.86 |

N = 1546 | 3D approach | x | x | x |

Depression (HADS) - Mean (SD) Intervention group: 6.1 (4.6) Control group: 6.8 (4.6) Adjusted beta coefficient (95% CI): − 0.01 (− 0.33–0.30) |

No effect |

|

Anxiety (HADS) - Mean (SD) Intervention group: 5.8 (4.7) Control group: 6.3 (4.8) Adjusted beta coefficient (95% CI): −0.24 (− 0.57–0.08) | |||||||

|

Waller, 2012 [31] Canada Interrupted time series trial 0.91 |

N = 114 | NAT:PD-C | x |

Clinical depression (HADS) - Percentage of patients with score 11+ 6 months pre and 6 months post intervention: T-3 9.9, T-2 8.4 (p < 0.05), T-1 10.2, T0 13.5, T1 9.5, T2 10.9, T3 13.8 |

No effect | ||

|

Clinical anxiety (HADS) - Percentage of patients with score 11+ 6 months pre and 6 months post intervention: T-3 8.8, T-2 8.1, T-1 8.5, T0 9.2, T1 9.2, T2 13.5, T3 8.1 | |||||||

| FUNCTION | |||||||

| Functional status/ADL | |||||||

|

Landi, 2001 [56] Italy RCT 0.93 |

N = 176 | Minimum Data Set for Home Care (MDS-HC) | x | x |

Barthel Index - Adjusted mean (SD) Intervention: 51.7 (36.1) Control: 46.3 (33.7) p = 0.05 |

Effective | |

|

IADL – Lawton Index - Adjusted mean (SD) Intervention: 23.5 (5.9) Control: 21.9 (6.6) p = 0.4 |

No effect | ||||||

|

Gestsdottir, 2015 [34] Iceland Prospective longitudinal 0.91 |

N = 81 | InterRAI-PC | x |

Change in physical function (InterRAI-PC) - Mean rank T1, T2, T3 X2, p-value Personal hygiene 1.62, 1.81, 2.57, 69.926, p = 0.001 Toilet use 1.71, 1.87, 2.42, 42.683, p = 0.001 Walking ability 1.71, 1.83, 2.46, 47.523, p = 0.001 Bed mobility 1.62, 1.83, 2.54, 66.953, p = 0.001 Eating 1.64, 1.81, 2.56, 73.345, p = 0.001 Use of urinary collection device 1.85, 1.98, 2.17, 10.950, p = 0.004 Bowel continence 1.83, 1.86, 2.30, 24.093, p = 0.001 |

Worsening effect | ||

|

Janssen, 2019 [32] The Netherlands Pre-test/post-test pilot study 0.73 |

N = 17 | NAT:PD-HF | x |

Performance status (AKPS) at baseline and 4 months: p = 0.10 |

No effect | ||

|

Care dependency (CDS): number of symptoms at baseline and 4 months: p = 0.43 |

No effect | ||||||

| Cognitive function | |||||||

|

Landi, 2001 [56] Italy RCT 0.93 |

N = 176 | MDS-HC | x | x |

MMSE - Adjusted mean (SD) Intervention: 19.9 (8.9) Control: 19.2 (10.7) p = 0.03 |

Effective | |

|

Gestsdottir, 2015 [34] Iceland Prospective longitudinal 0.91 |

N = 81 | InterRAI-PC | x |

Change in cognitive function (InterRAI-PC) - Mean rank T1, T2, T3 X2, p-value Cognitive skills for daily decision making 1.71, 1.86, 2.41, 39.282, p = 0.001 |

Worsening effect | ||

| SATISFACTION/QUALITY OF CARE | |||||||

| Patient-centred care | |||||||

|

Salisbury, 2018 [25] UK Cluster RCT 0.86 |

N = 1546 | 3D approach | x | x | x |

PACIC – Mean (SD) Intervention group: 2.8 (1.0) Control group: 2.5 (0.9) Adjusted beta coefficient (95% CI): 0.29 (0.16–0.41) |

Effective |

|

CARE doctor – Mean (SD) Intervention group: 40.2 (9.7) Control group: 37.5 (10.0) Adjusted beta coefficient (95% CI): 1.20 (0.28–2.13) |

Effective | ||||||

|

CARE nurse – Mean (SD) Intervention group: 40.8 (8.9) Control group: 38.5 (9.5) Adjusted beta coefficient (95% CI): 1.11 (0.03–2.19) |

Effective | ||||||

|

Patients reporting that they almost always discuss the problems most important to them in managing their own health – n/N (%) Intervention group: 256/612 (42%) Control group: 153/599 (26%) Adjusted odds ratio (95% CI): 1.85 (1.44–2.38) |

Effective | ||||||

|

Patients reporting that support and care is almost always joined up - n/N (%) Intervention group: 257/614 (42%) Control group: 173/603 (29%) Adjusted odds ratio (95% CI): 1.48 (1.18–1.85) |

Effective | ||||||

|

Patients reporting being very satisfied with care - n/N (%) Intervention group: 345/614 (56%) Control group: 236/608 (39%) Adjusted odds ratio (95% CI): 1.57 (1.19–2.08) |

Effective | ||||||

|

Patients reporting having a written care, health, or treatment plan - n/N (%) Intervention group: 141/623 (23%) Control group: 91/623 (15%) Adjusted odds ratio (95% CI): 1.97 (1.32–2.95) |

Effective | ||||||

| HEALTH SERVICE USE | |||||||

| Hospital admission/readmission | |||||||

|

Landi, 2001 [56] Italy RCT 0.93 |

N = 176 | MDS-HC | x | x |

Number of persons admitted at least once Intervention: 14.8% (n = 13) Control: 26.1% (n = 23) Relative Risk: 0.49 (95% CI: 0.56–0.97) |

Effective | |

|

Time to first hospital admission Log rank p = 0.05 | |||||||

|

Zafirau, 2012 [59] USA Pre-test/post-test 0.64 |

Pre-intervention N = 130 Post-intervention N = 117 |

Resident Change in Condition Assessment/Transfer Form | x |

Readmission within 30 days Pre intervention: 28.2% Post intervention: 22.2% p = 0.280 |

No effect | ||

|

Admissions to ICU, CCU, telemetry Pre intervention: 34% Post intervention: 47% p = 0.053 | |||||||

|

Treated and released from ER (%) Pre intervention: 79% Post intervention: 32% p = 0.329 | |||||||

|

Rockwood, 2000 [37] Canada RCT 0.79 |

N = 182 | CGA and GAS | x | x |

Institution-free survival -Days of institution-free survival Intervention: 340, SE = 9 Control: 342, SE = 8 Log rank = 0.661, p = 0.416 |

No effect | |

|

Proportion institutionalised Intervention: 13/95 Control: 8/87 X2 = 0.634, p = 0.426 | |||||||

|

Salisbury, 2018 [25] UK Cluster RCT 0.86 |

N = 1546 | 3D approach | x | x | x |

Hospital admissions - Median (IQR) Intervention group: 0.0 (0.0–1.0) Control group: 0.0 (0.0–1.0) Adjusted incidence rate ratio (95% CI): 1.04 (0.84–1.30) |

No effect |

| Hospital length of stay | |||||||

|

Forbat, 2019 [28] Australia Step-wedged RCT 0.73 |

N = 1700 | Palliative Care Needs Round Checklist | x | x |

Length of hospital stay (days) – Mean (SD) Intervention: 6.4 (8.3) Control: 6.9 (9.1) Treatment effect: − 0.22, 95% CI − 0.44—0.01, p = 0.038 |

Effective | |

|

Bristowe, 2015 [47] UK Comparative observational 0.85 |

N = 60 | Amber Care Bundle | x | x |

Length of hospital stay (days) – Mean (SD, median, range) Intervention: 20.3 (19.2, 14, 1–87) Comparison: 29.3 (20.4, 21, 6–70) p = 0.10 |

No effect | |

|

Landi, 2001 [56] Italy RCT 0.93 |

N = 176 | MDS-HC | x | x |

Total number of hospital days Intervention: 273 Control: 631 p = 0.40 |

No effect | |

|

Number of hospital days per user – Mean (SD) Intervention: 21.0 (13.4) Control: 27.4 (26.9) p = 0.40 | |||||||

|

Number of hospital days per admission – Mean (SD) Intervention: 13.3 (7.9) Control 20.8. (14.8) p = 0.08 | |||||||

|

Zafirau, 2012 [59] USA Pre-test/post-test 0.64 |

Pre-intervention. N = 130 Post-intervention N = 117 |

Resident Change in Condition Assessment/Transfer Form | x |

Length of hospital stay (days) Pre-intervention: 5.77 Post-intervention: 6.79 p = 0.058 |

No effect | ||

|

Length of hospital stay excluding hospice patients (days) Pre-intervention: 5.8 Post-intervention: 6.3 p = 0.480 | |||||||

| Place of death | |||||||

|

Schamp, 2006 [58] USA Pre-test/post- interventional cohort 0.68 |

Pre-intervention deaths N = 33 Post-intervention deaths N = 49 |

Pathways tool | x |

Deaths at home Before intervention: 24% After intervention: 65% p < 0.001 |

Effective | ||

|

Bristowe, 2015 [47] UK Comparative observational 0.85 |

N = 79 | Amber Care Bundle | x | x |

Place of death Intervention: Home or home of relative or close friend: 20% Hospice: 20% Hospital: 51% Care home: 9% Comparison: Home or home of relative or close friend: 9% Hospice: 9% Hospital: 68% Care home: 14% X2 = 5.71, p = 0.126 |

No effect | |

| Treatment/services received | |||||||

|

Rockwood, 2000 [37] Canada RCT 0.79 |

N = 182 | CGA and GAS | x | x |

Proportion receiving pneumococcal inoculation (%) Intervention: 10% (n = 8/81) Control: 1% (n = 1/74) P = 0.013 |

Effective | |

|

Zafirau, 2012 [59] USA Pre-test/post-test 0.64 |

Pre-intervention N = 130 Post-intervention N = 117 |

Resident Change in Condition Assessment/Transfer Form | x |

Admission to hospice (%) Pre intervention: 1.5% Post intervention: 7.7% P = 0.015 |

Effective | ||

|

Admitted to geropsychiatry (%) Pre-intervention: 1.7% Post-intervention: 2.3% p = 0.136 |

No effect | ||||||

|

Change in CPR, intubation, cardioversion performed (%) Pre intervention: 12% Post intervention: 9% p = 0.460 | |||||||

|

Feeding tube, surgery performed (%) Pre intervention: 19% Post intervention:23% p = 0.290 | |||||||

|

Landi, 2001 [56] Italy RCT 0.93 |

N = 176 | MDS-HC | x | x |

Use of community services: Home help (hours/year/patient) – Mean (SD) Intervention: 59.2, (18.0) Control: 14.7 (5.6) p = 0.02 |

Effective | |

|

Use of community services: Home nursing (hours/year/patient) – Mean (SD) Intervention: 28.3 (5.1) Control: 22.9 (2.1) p = 0.30 |

No effect | ||||||

|

Use of community services: Physiotherapist (hours/year/patient) – Mean (SD) Intervention: 11.2 (2.1) Control: 10.2 (1.6) p = 0.70 | |||||||

|

Use of community services – GP (home visits/year/patient) – Mean (SD) Intervention: 9.8 (1.2) Control: 10.1 (1.3) p = 0.80 | |||||||

|

Salisbury, 2018 [25] UK Cluster RCT 0.86 |

N = 1546 | 3D approach | x | x | x |

Nurse consultations – Median (IQR) Intervention group: 6.0 (4.0–10.0) Control group: 4.0 (2.0–8.0) Adjusted incidence rate ratio (95% CI): 1.37 (1.17–1.61) p = 0.0001 |

Effective |

| 3D approach | x | x | x |

Primary care physician consultations – Median (IQR) Intervention group: 10.0 (6.0–16.0) Control group: 8.0 (4.0–14.0) Adjusted incidence rate ratio (95% CI): 1.13 (1.02–1.25) p = 0.0209 |

|||

| 3D approach | x | x | x |

High risk prescribing – Median (IQR) Intervention group: 0.0 (0.0–1.0) Control group: 0.0 (0.0–1.0) Adjusted incidence rate ratio (95% CI): 1.04 (0.87–1.25) p = 0.680 |

No effect | ||

| 3D approach | x | x | x |

Hospital outpatient attendances – Median (IQR) Intervention group: 3.0 (1.0–5.0) Control group: 2.0 (1.0–5.0) Adjusted incidence rate ratio (95% CI): 1.02 (0.92–1.14) p = 0.720 |

|||

|

Bristowe, 2015 [47] UK Comparative observational 0.85 |

N = 76 | Amber Care Bundle | x | x |

Involvement of palliative care (%) Intervention: 60% Comparison: 61% X2 = 0.001, p = 0.980 |

No effect | |

|

McMillan, 2011 [49] USA RCT 0.73 |

N = 709 | Package of tools with feedback of results to care team | x |

Number of contacts (visits or calls) by members of interdisciplinary team - Mean (SD) at T1, T2, T3 Nurse visits: 3.4 (1.4), 2.2 (1.4), 2.5 (1.7) Home Health Aide: 0.50 (1.1), 0.80 (1.4), 0.9 (1.5) Volunteer visits: 0.02 (0.15), 0.06 (0.31) 0.05 (0.23) Physician visits: 0.3 (0.5), 0.2 (0.4), 0.2 (0.4) Psychosocial visits: 1.2 (0.6), 0.5 (0.6), 0.6 (0.7) Chaplain visits: 0.1 (0.3), 0.2 (0.4), 0.2 (0.5) Advanced Registered Nurse Practitioner: 0.1 (0.4), 0.1 (0.3), 0.1, (0.3) No change over time within groups (p > 0.05), and not modified by intervention (p > 0.05). |

No effect | ||

| Treatment burden/quality of disease management | |||||||

|

Salisbury, 2018 [25] UK Cluster RCT 0.86 |

N = 1546 | 3D approach | x | x | x |

Multimorbidity Treatment Burden Questionnaire – Mean (SD) Intervention group: 12.9 (15.0) Control group: 15.0 (17.1) Adjusted beta coefficient (95% CI): −0.46 (−1.78–0.86) |

No effect |

|

Eight-item Morisky Medication Adherence – Mean (SD) Intervention group: 6.7 (1.2) Control group: 6.6 (1.3) Adjusted beta coefficient (95% CI): 0.06 (− 0.05–0.17) | |||||||

|

Number of different drugs prescribed in past 3 months – Median (SE) Intervention group: 11.0 (8.0–15.0) Control group: 11.0 (8.0–15.0) Adjusted incidence rate ratio (95% CI): 1.02 (0.97–1.06) | |||||||

|

Number of QOF indicators met (quality of disease management) – Mean (SD) Intervention group: 84.3 (17.5) Control group: 85.6 (17.3) Adjusted beta coefficient (95% CI): 0.41 (−3.05–3.87) | |||||||

| SURVIVAL | |||||||

| Mortality/survival | |||||||

|

Landi, 2001 [56] Italy RCT 0.93 |

N = 176 | MDS-HC | x | x |

One-year mortality (%) Intervention: 30.5% Control: 29.5% RR = 1.05, 95% CI = 0.55–2.01 |

No difference in survival/mortality | |

|

Rockwood, 2000 [37] Canada RCT 0.79 |

N = 182 | CGA and GAS | x | x |

12-month survival - Proportion died Intervention: 13/95 Control: 7/87 X2 = 1.476, p = 0.224 |

No difference in survival/mortality | |

|

Survival time Intervention = 320 days (SE = 6) Controls = 294 days (SE = 6) Log rank = 1.284, p = 0.257 |

No difference in survival/mortality | ||||||

| CARER OUTCOMES | |||||||

|

Janssen, 2019 [32] The Netherlands Pre-test/post-test pilot study 0.73 |

N = 17 | NAT:PD-HF | x |

FACQ-PC at baseline and 4 months: Caregiver strain: p = 0.10 Caregiver distress: p = 0.48 Positive caregiving appraisal: p = 0.53 Family wellbeing: p = 0.94 |

No effect | ||

|

McMillan, 2011 [49] USA RCT 0.73 |

N = 709 | Package of tools with feedback of results to care team | x |

Received support - Model term: Estimate (SE), p-value Intercept: 3.67 (0.03), p < 0.001 Group: 0.02 (0.04), p = 0.618 Time: 0 (0), p = 0.964 Group x time: 0.01 (0), p = 0.228 |

No effect | ||

|

CES-D - Model term: Estimate (SE), p-value Intercept: 4.48 (0.10), p < 0.001 Group: −0.11 (0.12), p = 0.367 Time: −0.01 (0.01), p = 0.104 Group x time: − 0.01 (0.01), p = 0.574 | |||||||

|

Spiritual needs inventory - Model term: Estimate (SE), p-value Intercept: 1.21 (0.14), p < 0.001 Group: −0.08 (0.17), p = 0.637 Time: 0.01 (0.01), p = 0.271 Group x time: 0.02 (0.02), p = 0.138 | |||||||

| COSTS | |||||||

|

Forbat, 2019 [28] Australia Step-wedged RCT 0.73 |

N = 1700 | Palliative Care Needs Rounds Checklist | x | x |

Overall annual net cost-saving across 12 sites: A$1759, 011 (US$1.3 m; UK£0.98 m) Years 2017–2018 |

Cost effective | |

|

Landi, 2001 [56] Italy RCT 0.93 |

N = 176 | MDS-HC | x | x |

Total per capita health care costs Intervention: $837 Control: $1936 Years 1998/1999 p < 0.01 |

Cost effective | |

|

Thorn 2020 [27] UK Pragmatic cluster RCT 0.85 |

N = 1546 | 3D approach | x | x | x |

Adjusted QALYs over 15 months of follow-up - Mean (SE) Intervention: 0.675 (0.006) Control: 0.668 (0.006) Years 2015–2016 Incremental difference (95% CI): 0.007 (−0.009–0.023) |

Not cost-effective |

|

Adjusted costs from the NHS/PSS perspective - Mean (SE) Intervention: £6140 (333) Control: £6014 (343) Years 2015–2016 Incremental difference (95% CI): £126 (£-739-£991) | |||||||

|

ICER: £18,499 Years 2015–2016 Net monetary benefit at £20,000 (95% CI): £10 (£-956-£977) | |||||||

AKPS Australia-modified Karnofsky Performance Status, CARE Consultant and relational empathy, CES-D Center for Epidemiological Study-Depression Scale, EQ-5D-5L EuroQol-5D 5 level, EORTC QLQ-C30 European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire, FACQ-PC Family Appraisal of Caregiving Questionnaire, HADS Hospital anxiety and depression scale, HQLI Hospice quality of life index, IADL Instrumental activities of daily living, ICER Incremental cost-effectiveness ratio, IQR Interquartile range, MMSE Mini mental state examination, MSAS Memorial symptom assessment scale-revised, NHS National health service, PACIC Patient Assessment of Care for Chronic Conditions, PSS Personal social services, QALY Quality-adjusted life year, QODD Quality of death and dying, QOF Quality and outcomes framework, RCT Randomised controlled trial, SD Standard deviation, SE Standard error

We used QualSyst to appraise the quality of included studies [63]. One reviewer assessed the quality of each of the papers. We graded the quality of papers as strong (≥0.80), medium (≥0.60–0.79) and low (< 0.60) [64, 65]. A random 10% sample was assessed by a second reviewer. Scores that diverged by > 10% were discussed within the research team. For mixed methods study, we quality rated the dominant method that the study employed and gave the corresponding quality rating.

Data analysis and data synthesis

We used a results-based convergent synthesis design [15] to incorporate disparate data from qualitative and quantitative studies, in order to understand the processes of using tools in clinical care and the outcomes on care, and used data triangulation to strengthen the findings. Qualitative and quantitative data were analysed and presented separately, and the findings integrated into figures [15]. Qualitative data of the included papers’ results sections and quotations were thematically analysed using an a priori coding tree. This was informed by our conceptual framework of clinical uncertainty [9–13], and a theoretical model of using a person-centred outcome measure to improve outcomes of care [24]. We inductively developed additional codes for data relevant to our aim, but not in our a priori coding tree. The codes were then inductively themed. Qualitative data analysis was conducted by three investigators and all analysis was discussed in research meetings with the research team. We conducted narrative synthesis of quantitative data.

Outcomes and intervention components were defined and categorised in accordance with Rohwer et al. [66], and our conceptual framework of clinical uncertainty [9–13]. Intervention components and causal pathways were examined and presented according to the domains of our conceptual framework of clinical uncertainty (comprehensive assessment, communication with patients and families, continuity of care). Similarly, for effectiveness studies, we examined and presented outcomes by the domains of clinical uncertainty that the tools targeted. Only studies that had a comparison group, and presented and analysed comparator data to examine effect on the stated outcome, were included in the narrative synthesis. As we did not have any a priori criteria for acceptability and feasibility, and recognised that these may be different dependent on tool and setting, we did not report quantitative data on acceptability and feasibility.

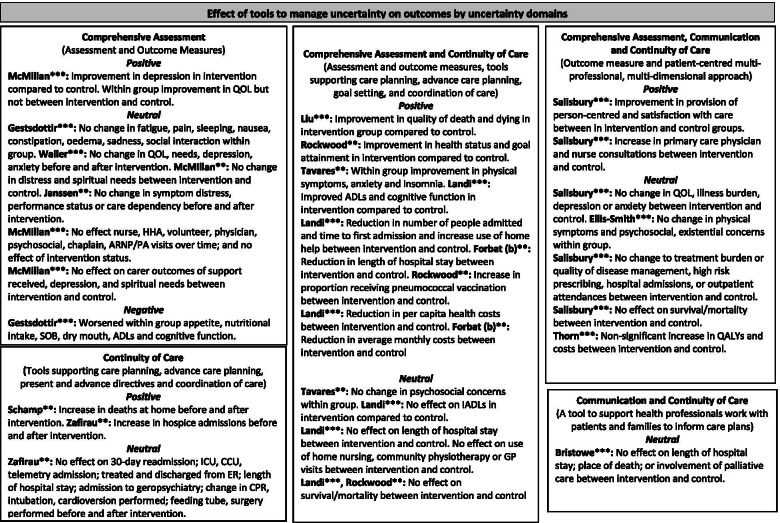

Results

Study selection

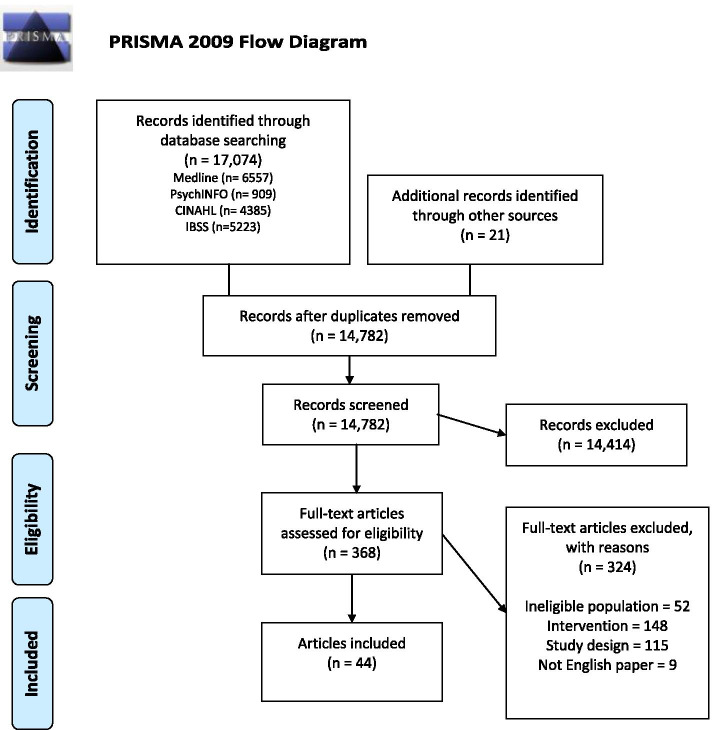

We identified 17,074 articles. Forty four articles met the eligibility criteria, reporting 40 studies (Fig. 1). After duplicates were removed, 14,782 articles were screened, including 21 articles retrieved from hand searching methods. From title and abstract screening, 368 articles proceeded to full text review. Studies were excluded at full text review due to ineligible population (n = 52), intervention (n = 148), study design (n = 115) and not written in English (n = 9).

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flowchart

Study characteristics and participants

Most of the included studies were conducted in the UK (n = 11), Australia (n = 8) or USA (n = 8). Study settings included hospitals (n = 12), community (including patient home, care agencies and GP surgeries) (n = 12), specialist units (including geriatric, palliative care and disease specific) (n = 8), hospice (n = 5) and care homes with or without nursing (n = 6; n = 5). Twenty-one articles were assessed as high quality (14 quantitative [25, 26, 29, 31, 33, 34, 38, 39, 46, 48, 51, 53, 54, 56], 7 qualitative [22–24, 27, 47, 55, 60]), 15 as medium quality (12 quantitative [20, 28, 32, 36, 37, 40, 42–44, 49, 58, 59], 3 qualitative [21, 35, 45])and 8 as low quality (3 quantitative [41, 50, 61], 5 qualitative [19, 30, 52, 57, 62]) (Table 1).

The number of participants included in studies ranged from 13 to 289,753, with approximately 54% female participants. Participants’ average age was 77.4 years and ranged from 28 to 103 years old. Most participants were patients, four studies included family members/carers and 9 studies included practitioners.

Sixty-three tools were identified over the 40 studies (Table 1). The Palliative care Outcome Scale (POS), and versions of it, were reported in six publications [19–24]. Three articles were included reporting the 3D approach study [25–27] and two studies examined the Palliative Care Needs Rounds tool across three publications [28–30]. Four tools and/or versions were identified in multiple studies (POS n = 4; Needs Assessment Tool (NAT) n = 2; Resident Assessment Instrument (RAI) n = 2; Missoula-VITAS Quality of Life Index (MVQOLI) n = 2). Six studies included Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment (CGA) [37–39] or geriatric assessments [40–42], however two of these studies did not define specific tools [37, 40]. Five studies examined ACP, including one as a part of a package of tools [43–46, 50]. Two articles reported on two ‘packages of tools’, meaning more than a single tool was used [49, 50].

Comprehensive assessment was the domain most targeted (31 publications) and communication was the least targeted (8 publications) (Table 1).

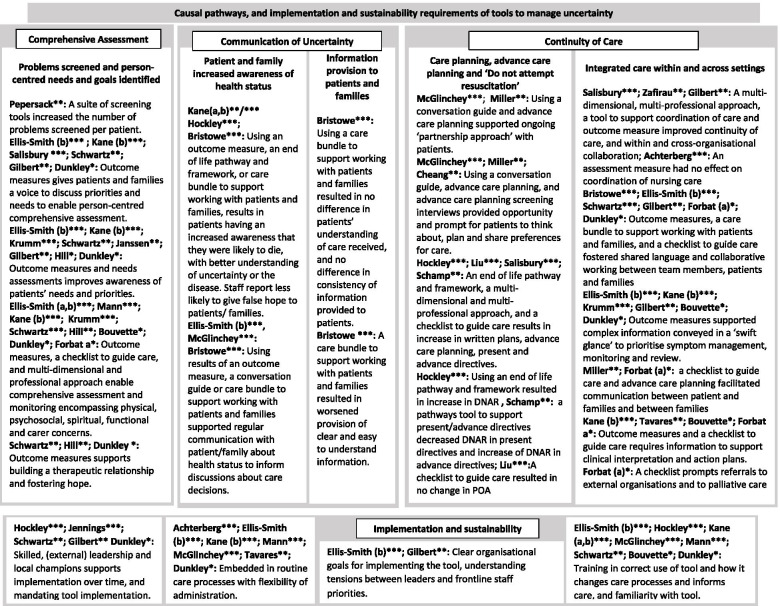

Causal pathways of tools used to manage clinical uncertainty

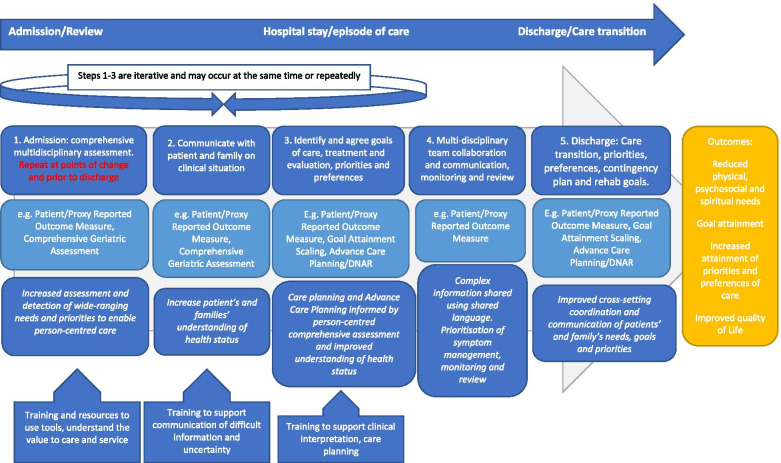

The causal pathways formed three overarching areas informed by our conceptual framework comprising: comprehensive assessment of the patient as a person and their family; communication with the patient and their family and continuity of care (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Causal pathways and implementation and sustainability requirements of tools to manage clinical uncertainty. Legend: Quality rating *** High quality; ** Medium quality; * Low quality

Comprehensive assessment of the patient as a person and their family, and enhanced understanding of patients’ priorities and needs

Our findings suggest that using tools improved practitioners’ awareness of patients’ priorities and needs through facilitating and enabling a systematic and structured discussion. Most studies used validated outcome measures to support comprehensive assessment, encompassing multiple domains of health in a single multidimensional tool such as POS, or a battery of standardised assessment tools, such as CGA. Comprehensive assessment sought to move beyond the biomedical model to encompass unstable or unmet symptoms, psychosocial and spiritual concerns, and to identify the patient’s priorities and needs [19, 24–26, 30, 32, 35, 36, 50, 55, 60, 62]:

‘It’s just so different from what you actually think and it’s quite frightening actually. You opened your eyes as to how complicated the human being is, totally and utterly. And [laughing] we don’t know it all and we never will. And people are just … [they] just live such different lives, their whole experience of life is so different from others.’ Nurse [35] (MVQOLI).

The use of tools increased attention on the importance of person-centred care and legitimatised spending time with the patient to understand what mattered to them [19]. The time spent as a result of using the tool may support the development of a therapeutic relationship and enhance discussions that may be challenging for practitioners or the patient [35, 36]. These mechanisms are linked to perceptions of improved symptom management and psychosocial outcomes, for example patient empowerment [19, 22, 50]. Using a tool gave patients a voice to communicate, in a systematic way, with practitioners to support assessment and enabled patients to be more actively involved in the clinical consultation [21, 26, 35]:

‘You never think of what’s wrong with you and how you’re feeling about it or has it improved, has it got worse, and should you do something different. I would think this [IPOS] is very good ‘cause, as I said, it makes you pinpoint exactly how you’re feeling … and what you can do or what you can’t do to improve it.’ [21] (Patient 10, female NYHA III, HFmrEF).

This facilitated consideration of areas practitioners and/or patients may not have otherwise discussed [22, 26, 35, 50, 55] and challenged practitioners’ perception of patients’ problems, shifting care and treatment to priorities for the patient [19, 22, 36].

Quantitative data supported these qualitative findings, indicating improved discussion of concerns important to patients [25] and improved screening of problems [42]. A high quality study tested the effectiveness of the 3D approach, an intervention targeting all domains [25]. In this Randomised Controlled Trial (RCT), 42% of patients in the intervention group reported that they almost always discussed the problems most important to them, compared to 26% in the control group, adjusted odds ratio (1.85 (95% CI 1.44–2.38), n = 1211). One medium quality study examined the use of a suite of tools, the Minimum Geriatric Screening Tools, to support comprehensive assessment [42]. The study demonstrated improvement in screening of problems after implementation of the intervention compared to before, with a mean increase of 3.2 (SD 1.8, p < 0.0001) problems per patient screened (n = 326).

Communication of clinical uncertainty with patients and families

Tools supported communication with patients and their families about the illness, changes in clinical presentation, progression of the disease and prognosis and empowered patients to engage in their own care. However, there was evidence that communication is challenging to do well and risks negative patient and carer experience. Tools targeting communication included outcome measures to facilitate discussion [21, 22, 24], end of life pathways and frameworks [53], a conversation guide [60], and a care bundle, called the Amber Care Bundle focusing on improving care and outcomes for hospitalised patients nearing the end of life and their families [47].

Tools improved communication with patients and families, supported improved understanding of the disease, and resulted in patients taking a more active role in understanding their disease [22, 60] and understanding of uncertainty [47]. Tools appeared to enhance communication with families by making routine the requirement for practitioners to update them on what to expect [47].