Abstract

Bax is a proapoptotic member of the Bcl-2 family of proteins which localizes to and uses mitochondria as its major site of action. Bax normally resides in the cytoplasm and translocates to mitochondria in response to apoptotic stimuli, and it promotes apoptosis in two ways: (i) by disrupting mitochondrial membrane barrier function by formation of ion-permeable pores in mitochondrial membranes and (ii) by binding to antiapoptotic Bcl-2 family proteins via its BH3 domain and inhibiting their functions. A hairpin pair of amphipathic α-helices (α5-α6) in Bax has been predicted to participate in membrane insertion and pore formation by Bax. We mutagenized several charged residues in the α5-α6 domain of Bax, changing them to alanine. These substitution mutants of Bax constitutively localized to mitochondria and displayed a gain-of-function phenotype when expressed in mammalian cells. Furthermore, substitution of 8 out of 10 charged residues in the α5-α6 domain of Bax resulted in a loss of cytotoxicity in yeast but a gain-of-function phenotype in mammalian cells. The enhanced function of this Bax mutant was correlated with increased binding to Bcl-XL, through a BH3-independent mechanism. These observations reveal new functions for the α5-α6 hairpin loop of Bax: (i) regulation of mitochondrial targeting and (ii) modulation of binding to antiapoptotic Bcl-2 proteins.

Members of the Bcl-2 family are major regulators of apoptosis and include both pro- and antiapoptotic proteins. Bax is a proapoptotic Bcl-2 family member which participates in the induction of apoptosis in response to a variety of apoptotic signals (4, 15, 27, 31). Furthermore, overexpression of Bax induces apoptosis in many cells (31, 50). A number of biochemical functions have been defined for Bax, some of which correlate with its proapoptotic activity, including (i) heterodimerization with the proapoptotic Bcl-2 proteins (9, 48, 49), (ii) homodimerization (8, 19, 51), (iii) release of cytochrome c from mitochondria (14), and (iv) disruption of the potential across the inner mitochondrial membrane (32, 47). Recently, it has been shown that Bax functionally interacts with components of the mitochondrial inner membrane, the adenine nucleotide transporter (ANT) (22), and the mitochondrial F0F1 ATPase H+ pump (24), as well as the outer membrane voltage-dependent anion channel (VDAC) (40).

The three-dimensional structures of the Bcl-2 family members Bcl-XL and Bid have been determined, revealing striking resemblance to the pore-forming domains of certain bacterial toxins (2, 25, 35). Moreover, Bcl-2 and Bax can be readily modeled on the same X-ray crystallographic coordinates (36), suggesting that they also possess similar protein folds. This structural homology correlates with the ability of at least four members of the Bcl-2 family, Bcl-XL, Bcl-2, Bid, and Bax, to form ion-conducting pores in synthetic lipid membranes in vitro (1, 26, 37–39). A hairpin pair of α-helices within the pore-forming domains of bacterial toxins that share structural similarity to Bcl-2 family proteins directly participates in membrane insertion, leading to the generation of voltage-dependent ion-conducting channels (3, 28). Similarly, deletion of the corresponding α-helical hairpin in Bcl-2 and Bax (i.e., α5 and α6) abrogates their ability to form ion-conducting pores in vitro (23, 38), suggesting that this domain performs a similar function in the Bcl-2 family.

The putative pore-forming α-helices in Bcl-2 family proteins are amphipathic. When inserted into membranes, the polar residues of the amphipathic α-helices presumably line the aqueous channels of pores, and this would be expected to play an important role in mediating the function of Bcl-2 family proteins in their capacity as pore-forming proteins. Alternatively, since the α5-α6 domain is involved in membrane insertion, the charged residues within this domain might participate in or regulate interactions of Bax with other proteins within mitochondrial membranes. We therefore generated a series of alanine substitutions for charged residues within the α5 and α6 helices of Bax, evaluating the relevance of these polar residues to the proapoptotic function of the Bax protein.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmids.

Bax mutants were constructed by the method of two-step PCR mutagenesis (10), using a cDNA encoding the open reading frame of mouse Bax (49). The final PCR products were cloned into EcoRI and XhoI sites of the pSKII plasmid, and the entire mouse Bax open reading frame was sequenced. Subsequently, wild-type (WT) and mutant Bax cDNAs were subcloned into the yeast expression plasmids pGilda (a gift of E. Golemis) and pEMBLGST (a gift of Elain Elion) as EcoRI/XhoI and SmaI/HindIII fragments, respectively. Bax is expressed as a fusion protein with an N-terminal LexA DNA-binding domain and glutathione-S-transferase in the pGilda and pEMBELGST plasmids, respectively. For mammalian expression, the EcoRI/XhoI fragments of WT and mutant Bax cDNAs were subcloned into the EcoRI/XhoI and EcoRI/SalI sites of HA-pcDNA3 and pEGFP-C2, respectively. Bax is expressed as a fusion protein C-terminal to three contiguous HA tags and to green fluorescent protein (GFP) in HA-pcDNA3 and pEGFP-C2, respectively.

Yeast studies.

The yeast strains EGY48 and Brm-1 were used for Bax-mediated cytotoxicity assays (24). Cells were transformed by the lithium acetate method, using 1.0 μg of plasmid DNA and 1.0 μg of sheared, denatured salmon sperm (carrier) DNA. To test viability, transformant colonies were streaked on histidine-deficient (pGilda-based plasmids) or uracil-deficient (pEMBELGST-based plasmids) minimal medium containing either glucose or galactose as a carbon source. The ability of the cells to grow in the presence of Bax expression (on galactose-containing medium) was monitored after incubation at 30°C for 4 to 5 days. For analysis of protein expression, transformants were grown in the appropriate liquid minimal medium containing glucose to an optical density at 600 nm of 0.4 to 0.5. The cells were washed in H2O three times before incubation in minimal medium containing galactose for 12 h.

Cell culture, transfection, and mammalian-cell apoptosis assays.

Cos-7 and 293T cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 1 mM l-glutamine (final concentration), and antibiotics. The transfection reagents Lipofectamine (Gibco BRL) and Superfect (Qiagen) were used for transfection of Cos-7 and 293T cells, respectively. For luciferase-based killing assays, 0.5 μg of either pEGFP-C2 or GFP fusion plasmids, along with 0.1 μg of pGL3 control plasmid (Promega) containing the firefly luciferase gene, was used to transfect 5 × 104 Cos-7 cells in 12-well tissue culture dishes. The transfectants were washed with phosphate-buffered saline and harvested using a luciferase assay system (Promega). Luciferase activity was measured using a luminometer (MicroLumat LB96P; Wallac Inc., Gaithersburg, Md.). To test apoptotic activity in 293T cells, both floating and adherent cells were pooled, fixed in 3.7% paraformaldehyde, and subjected to staining with 4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) 6 to 18 h after transfection with 2.0 μg of pcDNA3 or pEGFP-C2 plasmids encoding WT or mutant Bax. For transfections with pcDNA3 constructs, 0.5 μg of pEGFP-N2 was included to identify transfected cells. In some transfections, zVAD-fmk (100 μM) was added 2 h after transfection, and apoptotic and cytotoxic activity was assessed by DAPI staining and propidium iodide (PI) dye exclusion, respectively, 48 h posttransfection. To test suppression of Bax activity by Bcl-XL, 0.5 μg of either WT or mutant GFP fusion plasmids was cotransfected with 1.5 μg of either pcDNA3-Bcl-XL or pcDNA3 into 293T cells. Cytotoxic and apoptotic assays were performed as described above at 48 h posttransfection.

Confocal microscopy.

Cos-7 cells (104) in eight-chambered glass slides (LabTek) were transfected with 0.25 μg of either pEGFP-C2 or GFP-Bax (WT or mutant) fusion constructs using 0.75 μl of Lipofectamine. The cells were incubated with or without Staurosporine (STS) (1 μM final concentration) for 4 h, after which they were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde. To test the localization of Bax in 293T cells, 6 × 105 cells were transfected with 2.0 μg of the above-mentioned plasmids and the cells were harvested 6 h posttransfection, fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde, and mounted on a glass slide. The localization of GFP and GFP fusion proteins was monitored by confocal microscopy using a Bio-Rad laser confocal microscope (MRC-1024).

Immunoblot and immunoprecipitation studies.

For immunoblot assays involving yeast, extracts were prepared by breaking the cells using glass beads in lysis buffer (150 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 50 mM Tris [pH 7.4], 1% NP-40, and protease inhibitors). Aliquots containing 10 μg of total protein were separated in sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)–10% polyacrylamide gels, transferred to Immobilon P nylon membranes, and incubated with a polyclonal rabbit anti-LexA antiserum (a gift of E. Golemis). Antigen was detected by incubation of the blots with horseradish peroxidase secondary antibodies followed by the Enhanced ChemiLuminescence detection kit (Amersham). For mammalian expression studies, cells were lysed in radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer (10 mM Tris [pH 7.4], 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 0.5% deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 5 mM EDTA, and protease inhibitors). Aliquots of extracts containing 5 to 30 μg of total protein were analyzed by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis immunoblotting as described above. Antigen detection was accomplished using either a polyclonal rabbit anti-mouse Bax (16) or a monoclonal antibody to GFP (Clonetech).

For immunoprecipitation experiments, Cos-7 cells (7.5 × 105/10-mm-diameter dish) were transfected with 5.0 μg of FLAG-Bcl-XL in pcDNA3 and 5.0 μg of either pEGFP-C2 or GFP fusion Bax plasmids, using 30 μl of Lipofectamine. zVAD-fmk was added to cultures 2 h posttransfection, and the cells were incubated for a further 20 h. Cell extracts were prepared using an isotonic lysis buffer (142.5 mM KCl, 1 mM EGTA, 5 mM MgCl2, 10 mM HEPES [pH 7.4], 0.2% NP-40, and protease inhibitors). Following preclearing of extracts with agarose-GST, Bcl-XL complexes were immunoprecipitated using an anti-FLAG M2-agarose affinity gel (Sigma). The immune complexes were denatured by boiling them in the presence of Laemmli sample buffer, and aliquots from each sample were loaded into SDS–12% polyacrylamide gels. The presence of Bcl-XL and GFP-Bax (WT or mutant) complexes was monitored by immunoblotting using a polyclonal anti-human Bcl-XL (17) and a monoclonal anti-GFP antibody, respectively.

Subcellular fractionation.

Cos-7 cells (3 × 106/20-mm-diameter plate) were transfected with 18 μg of HA-pcDNA3 Bax (WT or mutant) along with 2 μg of pEGFP-C2 plasmid, using 60 μl of Lipofectamine. zVAD-fmk (50 μM) was added to the cell cultures 2 h posttransfection, and the cells were incubated for a further 20 h. Then the cells were incubated in the presence or absence of STS (1 μM) for 4 h. Cell extracts were prepared in a hypotonic buffer (5 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4], 5 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, and protease inhibitors), and fractionated as previously described (43). The heavy-membrane (HM) and light-membrane (LM) fractions were boiled in 100 μl of Laemmli buffer. The soluble fraction was mixed with one-third volume of a 4×-concentrated Laemmli solution and boiled. Aliquots of fractions normalized for cell equivalents were separated on SDS–12% polyacrylamide gels and transferred to Immobilon nylon membranes. Antigen detection was performed using a rat monoclonal antihemagglutinin (anti-HA) high-affinity antibody (Boehringer Mannheim) and a rabbit polyclonal anti-human Bcl-2 antiserum (27). For alkali extractions using HM mitochondrion-enriched fractions, cell extracts were prepared in buffer A (20 mM HEPES [pH 7.4], 10 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM dithiothreitol, and protease inhibitors). After a low-speed centrifugation to pellet whole cells and nuclei, the cell extract was divided into two portions, each of which was centrifuged to obtain an HM fraction. One HM fraction was resuspended in a mitochondrial resuspension buffer (120 mM mannitol, 70 mM sucrose, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, and 10 mM HEPES [pH 7.5]). The other HM preparation was resuspended in the same volume of freshly prepared 0.1 M Na2CO3 (pH 11.5). Both HM fractions were incubated on ice for 30 min, followed by centrifugation for 10 min at 170,000 × g in a Beckman airfuge. Mitochondrial pellets and supernatants were boiled in Laemmli sample solution, normalized for cell equivalents, and separated in SDS–12% polyacrylamide gels. Protein was blotted onto Immobilon-P nylon membranes and probed with a rat monoclonal anti-HA high-affinity antibody (Boehringer Mannheim), a mouse monoclonal antibody to human mitochondrial Hsp60 (Santa Cruz), and a mouse monoclonal antibody (Molecular Probes) recognizing subunit II of human cytochrome c oxidase (COX-II).

RESULTS

Cytotoxicity of Bax alanine substitution mutants in yeast.

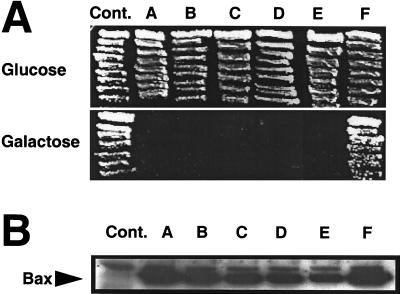

The putative pore-forming α5-α6 region of Bax is predicted to comprise a hairpin-pair of amphipathic α-helices which contains 10 charged residues (Fig. 1). We systematically replaced these charged residues with alanine to investigate their significance for the killing activity of Bax. Bax confers a lethal phenotype when ectopically expressed in the lower eukaryote Saccharomyces cerevisiae, with characteristics similar to that imposed by Bax on mammalian cells, including induction of cytochrome c release from mitochondria and disruption of mitochondrial membrane potential in a manner that is suppressible by Bcl-2, Bcl-XL, and Mcl-1 (13, 21, 34, 50). It is highly likely that the ability of Bax to kill yeast is related to its intrinsic activity as a pore-forming protein for two reasons: (i) yeast lacks Bcl-2 family proteins and (ii) deletion of the α5-α6 region of Bax abrogates its lethal effect in yeast (23). As such, yeast provides a convenient readout system for understanding structure-function relations within Bax protein which are relevant to its pore-like activity. Thus, we initially analyzed the cytotoxic activity of the Bax mutants in the yeast S. cerevisiae strain EGY48. For these experiments, WT and mutant versions of Bax were expressed in yeast under the control of the GAL1 promoter, which permits repression and induction of Bax protein expression, by plating cells on media containing glucose or galactose, respectively. As shown in Fig. 2A, the cytotoxic activity of Bax is not compromised upon alanine substitution for up to 7 of 10 charged residues within α5-α6; however, replacement of an additional charged residue (R109), leaving E131 and R147 as the only charged residues, completely abrogated the killing activity of Bax in yeast. Single substitution of tryptophan for the R109 residue did not lead to loss of Bax activity (not shown), suggesting a requirement for multiple substitutions in the putative pore-forming domain for inactivation of the cytotoxic function of Bax in yeast. Measurement of protein expression by immunoblotting (Fig. 2B) showed that the loss of activity of the multiply substituted Bax mutant was not due to instability of the mutant protein.

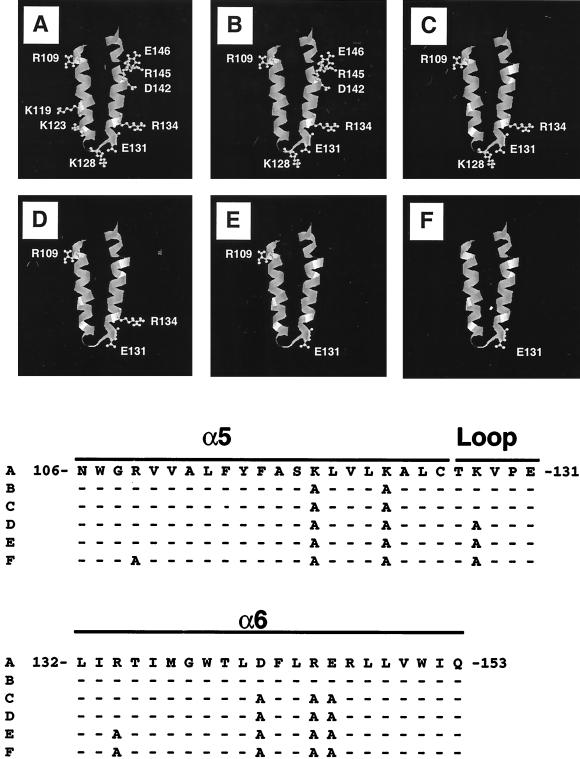

FIG. 1.

Diagram of mutations generated in Bax. (Top) Ribbon diagrams of the α5-α6 helical hairpin of Bax. The hypothetical three-dimensional structure of Bax was modeled, based on the coordinates available for Bcl-XL, using the Quanta software package (Molecular Simulations, San Diego, Calif.). The charged residues lining the helical hairpin (residues N106 to Q153) are shown as ball-and-stick representations for WT Bax (A). To illustrate the mutagenic alterations (B to F), the ball-and-stick representations for the residues replaced by alanine are omitted. (Bottom) Amino acid sequence of the α5-α6 regions of WT and mutant Bax proteins. Although the α5-α6 region contains a total of 10 charged residues, we have not considered R147, since it is present in the opposite side of all other charged residues. Accordingly, the ball-and-stick representation of this residue is not depicted in the ribbon diagrams above. The letters on the left correspond to the panels above. The dashes represent residues identical to those in sequence A.

FIG. 2.

Cytotoxic activity and expression of Bax mutants in yeast. (A) Yeast strain EGY48 was transformed with 1.0 μg of either the empty yeast expression vector pGilda (Cont.) or pGilda containing WT Bax or the various Bax alanine substitution mutants (the letters correspond to those in Fig. 1). Individual transformant colonies were streaked on histidine-deficient (His−) medium containing glucose (Bax expression repressed) or His−-galactose (Bax expression induced) semisolid medium and incubated at 30°C for 4 days. (B) Immunoblot results are shown for lysates (10 μg) of yeast cells grown in His−-galactose medium for 12 h. The blot was incubated with anti-LexA antiserum, followed by enhanced chemiluminescence-based detection.

Neutralization of charged residues in the α5-α6 region of Bax enhances apoptotic and cytotoxic activities.

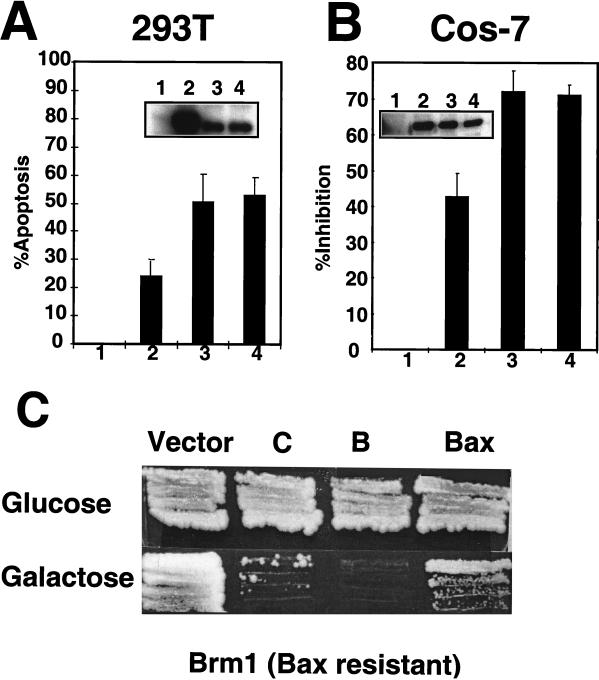

To further evaluate the characteristics of Bax mutants, we first concentrated on Bax mutants B and C, which remain active in yeast and which, among the mutants tested, have the fewest substitutions in the pore-forming domain. Although neutralization of charged residues in the α5-α6 domain did not inactivate the cytotoxicity of Bax in yeast, we considered the possibility that some of these residues in the α5-α6 helix might be required for apoptosis in mammalian cells. For this reason, the apoptotic activity of Bax mutants B (K119A and K123A) and C (K119A, K123A, D142A, R145A, and E146A) was compared with WT Bax in transient-transfection assays in 293T and Cos-7 cells. The Bax B and C mutants induced higher percentages of apoptosis in 293T cells than did WT Bax (Fig. 3A). Similarly, the B and C mutants of Bax were more potent than WT Bax at inducing cell death in Cos-7 cells (Fig. 3B) when tested in a cytotoxicity assay that uses luciferase activity as an endpoint for determining relative numbers of surviving cells (45). Comparison of the steady-state levels of WT and mutant Bax proteins by immunoblot analysis of lysates prepared from 293T and Cos-7 transfectants revealed that the B and C mutant Bax proteins were generally present at slightly lower levels than WT Bax, excluding excessive production of mutants as an explanation for their apparent gain-of-function phenotypes.

FIG. 3.

Bax mutants B and C display a gain-of-function phenotype in mammalian and yeast cells. (A) 293T cells were transfected with empty HA-pcDNA3 vector (bar 1) or pcDNA3 encoding HA-tagged WT Bax (bar 2) or mutant Bax-B (bar 3) or Bax-C (bar 4) protein. The percentage of apoptotic cells (+ standard deviation [SD]) was determined by DAPI staining at 8 h posttransfection. The inset shows an immunoblot analysis of the cells transfected with HA-pCDNA3 (lane 1) or plasmids encoding WT Bax (lane 2) and mutant Bax-B (lane 3) and Bax-C (lane 4), detected with a polyclonal anti-mouse Bax antiserum. (B) Cos-7 cells were transfected with 0.1 μg of the luciferase-encoding plasmid pGL3 control, along with either empty pEGFP-C2 (bar 1), pEGFP-C2–Bax WT (bar 2), pEGFP-C2–Bax mutant B (bar 3), or pEGFP-C2–Bax mutant C (bar 4). The amount of luciferase activity measured for WT and mutant Bax was normalized to that obtained for pEGFP-C2 alone, taking the latter as 100% activity. The results were then subtracted from 100% and plotted as percent inhibition. The data shown represent the averages of three different experiments, each performed in duplicate (mean + SD). The inset shows expression of GFP-WT Bax (lane 2) or GFP-mutant Bax (lanes 3 and 4) proteins detected with a monoclonal antibody to GFP. Lane 1 contains extract from cells transfected with empty vector. (C) The Bax-resistant yeast strain Brm-1 was transformed with 1.0 μg of empty pEMBELGST vector, or pEMBELGST encoding WT Bax or Bax mutants B and C. Transformants were selected on Ura−-glucose+ medium, and individual colonies were grown on Ura−-glucose+ medium (Bax expression repressed) or Ura−-galactose+ medium (Bax expression induced) for 4 days at 4°C.

To investigate whether the increase in apoptotic activity of Bax mutants is also manifested in yeast, we tested the killing activity of the B and C Bax mutants in the yeast strain Brm-1 (for Bax-resistant mutant 1), which, as we have shown previously, is resistant to the cytotoxic activity of WT Bax (24). In contrast to WT Bax, which was unable to kill the Brm-1 yeast strain, the gain-of-function Bax mutants were cytotoxic, preventing the growth of Brm-1 cells on galactose-containing medium, which induces production of these proteins (Fig. 3C). Immunoblot analysis suggested that the enhanced activity of the B and C Bax mutants was not due to higher levels of protein production than WT Bax (not shown). We concluded, therefore, that the B and C mutants of Bax display a gain-of-function phenotype in both mammalian cells and yeast.

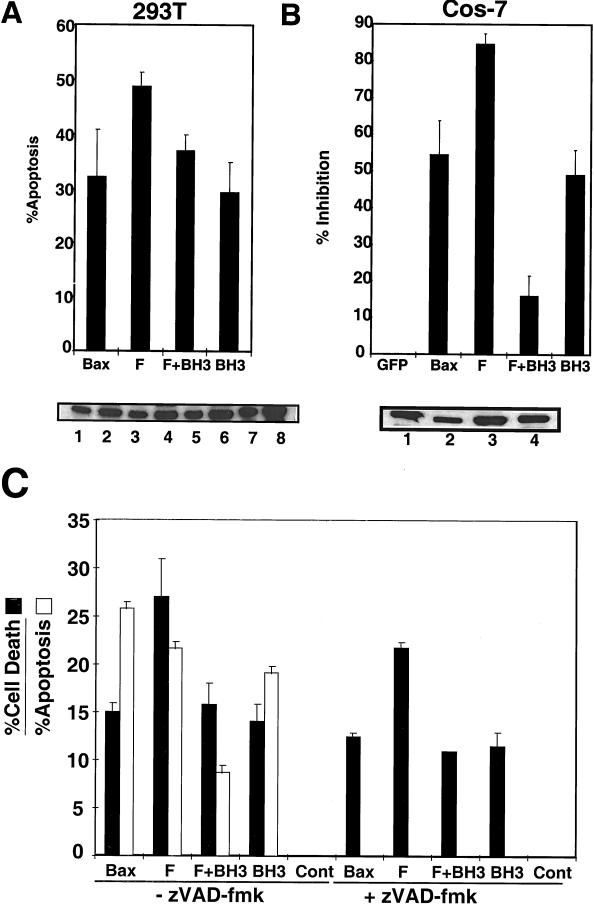

Cytotoxic activity of gain-of-function mutants of Bax is nullified by Bcl-XL but not by the caspase inhibitor zVAD-fmk.

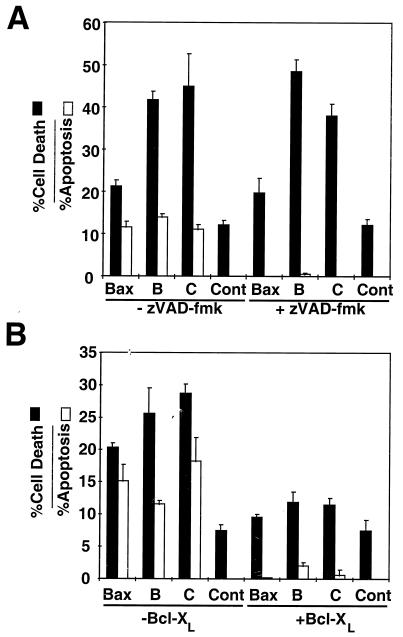

It has been shown that the cytotoxic activity of Bax arises from two separable components which are caspase dependent and independent (14, 47, 50), with the latter ascribed to the intrinsic function of Bax as a pore-forming protein (reviewed in references 7 and 33). The intrinsic caspase-independent activity of Bax can be monitored by culturing Bax-overexpressing cells in the presence of the broad-spectrum caspase inhibitor zVAD-fmk. Accordingly, 293T cells were transiently transfected with plasmids encoding WT or mutant Bax proteins and then cultured in the presence or absence of zVAD-fmk. The percentages of apoptotic and dead cells were measured after 48 h by DAPI staining and by PI dye exclusion assays, respectively (43, 50). As shown in Fig. 4A, when tested in the absence of zVAD-fmk, WT Bax and the Bax B and C mutants induced both apoptosis and cell death of transiently transfected 293T cells, with the B and C mutants displaying enhanced cytotoxic activity relative to that of WT Bax. In contrast, addition of zVAD-fmk almost completely prevented Bax-induced apoptosis but did not block cell death induction. Moreover, the Bax B and C mutants continued to exhibit enhanced cytotoxic activity relative to WT Bax, even in the presence of zVAD-fmk (Fig. 4). In contrast to zVAD-fmk, which only suppressed Bax-induced apoptosis but not cell death, Bcl-XL suppressed both apoptosis (nuclear fragmentation as revealed by DAPI staining) and cell death (PI dye uptake) induced by WT and mutant Bax proteins (Fig. 4B). These data argue that the enhanced cytotoxicity of the B and C mutants does not arise through nonspecific mechanisms, since it is suppressible by Bcl-XL.

FIG. 4.

Inhibition of apoptotic and cytotoxic activity of WT and mutant Bax by zVAD-fmk and Bcl-XL. (A) zVAD-fmk inhibits the apoptotic but not the cytotoxic activity of WT and mutant Bax. Empty HA-pcDNA3 (Cont) or pcDNA3 encoding HA-WT Bax, Bax-B, or Bax-C (2 μg each) was transfected into 293T cells, followed by culturing in the presence (+) or absence (−) of 100 μM zVAD-fmk. The percentages of apoptotic cells and dead cells were measured by DAPI staining of the nuclei and cellular uptake of PI, respectively, 2 days posttransfection (mean + standard deviation [SD]; n = 3). (B) Bcl-XL inhibits both the apoptotic and cytotoxic activities of WT and mutant Bax. Control HA-pcDNA3 plasmid (Cont) or HA-pcDNA3 plasmids encoding WT Bax or HA-Bax mutants (0.5 μg), were transfected into 293T cells, with or without 1.5 μg of pcDNA3-Bcl-XL. The cells were scored for apoptotic nuclei and cytotoxic cell death (means + SD) by DAPI staining of nuclei and uptake of PI, respectively, 2 days after transfection.

Gain-of-function Bax mutants induce apoptosis with accelerated kinetics.

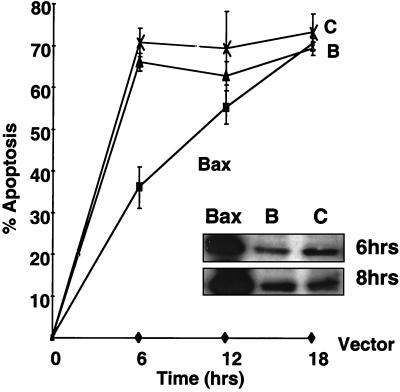

To investigate whether the enhanced apoptotic activity of Bax mutants was due to a higher rate of apoptosis induction versus an absolute increase in potency, the time course of apoptosis induction was examined in cultures of 293T cells following transfection with plasmids encoding WT Bax or the B and C mutants of Bax. The GFP-encoding pEGFP-N2 plasmid was included in all the transfections to monitor transfection efficiency. Although WT Bax induced a lower percentage of transfected cells to undergo apoptosis than did the gain-of-function mutants at 6 h posttransfection, given sufficient time, the apoptotic activity exhibited by WT Bax approached that of the B and C mutants (Fig. 5). Immunoblotting experiments indicated that the faster kinetics of apoptosis induction exhibited by the B and C mutants was not attributable to accelerated production of these proteins in transfected cells compared to WT Bax (Fig. 5, inset). Indeed, WT Bax protein levels were consistently higher than those of Bax-B or Bax-C proteins. This observation suggests that the gain-of-function Bax mutants bypass a rate-limiting step required for Bax protein activation or function.

FIG. 5.

Gain-of-function Bax mutants kill 293T cells with accelerated kinetics. Plasmid HA-pcDNA3 (Vector) or HA-pcDNA3 encoding WT-Bax (Bax) or mutants Bax-B (B) and Bax-C (C) (2.0 μg each) was transfected into 293T cells. The percentages of apoptotic nuclei were scored 6, 12, and 18 h after transfection (mean ± standard deviation; n = 3). The inset is an immunoblot showing the expression of WT and mutant Bax at 6 and 8 h after transfection, using a polyclonal anti-mouse Bax antiserum.

Bax mutants constitutively localize to mitochondria.

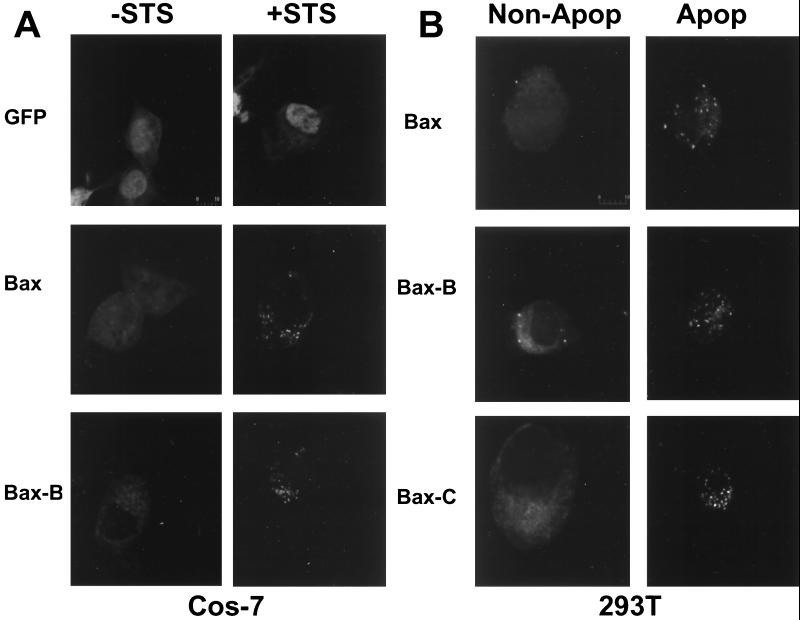

Previously, it has been shown that Bax protein resides in the cytosol of some types of cells, undergoing translocation to mitochondrial membranes upon receiving an apoptotic stimulus (11, 12, 46). Since the only early rate-limiting step thus far identified in the Bax pathway for apoptosis is the localization of Bax to mitochondria, we used fluorescence microscopy to monitor the subcellular localization of GFP-tagged WT and mutant Bax proteins. These experiments were performed using Cos-7 cells, in which it has been reported that STS induces the translocation of Bax to mitochondria (11, 12, 46). As shown in Fig. 6A, Bax displayed a uniform distribution in unstimulated Cos-7 cells but localized to cytosolic organellar structures upon treatment with STS. In contrast, the B and C mutants of Bax exhibited a punctate cellular distribution in both the presence and absence of STS (Fig. 6A [only mutant B is shown]). Two-color analysis using a mitochondrion-specific dye (Mitotracker C) confirmed colocalization of Bax to mitochondria following exposure to STS (not shown). We conclude, therefore, that the alanine substitutions in the hyperactive mutants B and C modify the subcellular distribution of these proteins, allowing constitutive mitochondrial localization.

FIG. 6.

Bax gain-of-function mutants constitutively localize to cellular membranes. (A) Cos-7 cells were transfected with either pEGFP-C2 or pEGFP-C2 encoding WT Bax or mutant Bax-B. After 20 h of transfection, the cells were incubated with or without STS for 4 h. The cells were fixed, and the localization of GFP and GFP fusion proteins was determined using confocal microscopy. (B) Localization of GFP and various GFP-Bax fusion proteins at 6 h posttransfection in 293T cells. Healthy (non-Apop) and apoptotic (Apop) cells are shown.

Similar observations were made using 293T cells. In 293T cells, WT Bax constitutively targets mitochondria when overexpressed by transient transfection without the necessity for additional apoptotic stimuli (50). By monitoring GFP-Bax localization in 293T cells at various times after transfection, we observed that WT GFP-Bax was diffusely distributed throughout most cells at 6 h posttransfection (Fig. 6B, left), localizing to mitochondria only in apoptotic cells (Fig. 6B, right). In contrast, the GFP-tagged Bax B and C mutants exhibited a punctate distribution indicative of mitochondrial localization in essentially all cells examined at 6 h posttransfection (Fig. 6B). Cotransfection of Bcl-XL did not alter the punctate distribution of Bax mutants in 293T or Cos-7 cells (not shown) but did prevent Bax-induced cell death.

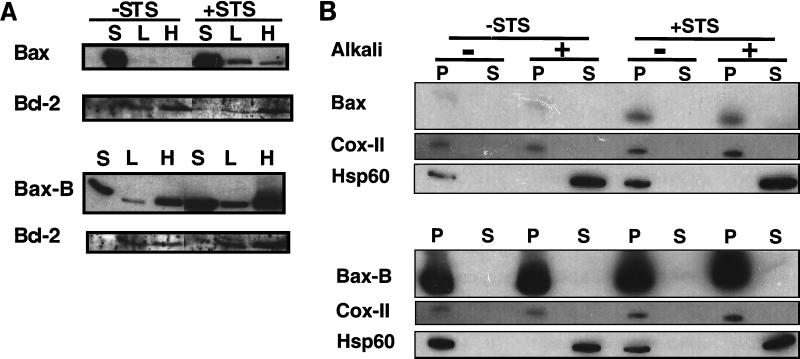

To confirm that the punctate distribution of Bax mutants represents constitutive mitochondrial localization, we performed subcellular-fractionation experiments using cell lysates from Cos-7 cells which had been transiently transfected with plasmids encoding HA-tagged WT Bax or Bax mutant B. The cells were cultured in the presence or absence of STS prior to preparation of soluble (cytosolic), LM, and HM fractions. As shown in Fig. 7A, WT Bax was located predominantly in the soluble fractions of unstimulated Cos-7 cells, with a negligible association with membrane fractions in the absence of STS. In contrast, in extracts prepared from STS-treated cells, WT Bax was clearly detected in both the LM and mitochondrion-enriched HM fractions. Although some of the mutant B and C Bax protein was found in the soluble fraction, a considerable proportion of the Bax-B (Fig. 7A) and Bax-C (not shown) localized to intracellular membranes, including mitochondria, in the absence of STS, unlike WT Bax. These observations thus confirm the results obtained by confocal microscopy using GFP-tagged proteins. Furthermore, the HM-associated Bax-B and Bax-C proteins were mostly membrane inserted, based on their resistance to extraction from membranes by alkali (Fig. 7B and not shown). Examination of soluble (Hsp60) and integral (COX-II) membrane mitochondrial proteins as controls verified successful use of the alkali extraction procedure for assessing the status of WT and mutant Bax proteins (Fig. 7B). We conclude, therefore, that a large fraction of the Bax-B and Bax-C gain-of-function mutant proteins constitutively target and insert in membranes prior to any evidence of apoptosis or stimulation with exogenous apoptosis-inducing agents.

FIG. 7.

Analysis of Bax mutants by subcellular fractionation and alkali extraction. Cos-7 cells were transfected with 18 μg of pcDNA3 encoding HA-Bax or HA–Bax-B, followed by incubation for 20 h. Then the transfectants were incubated for 4 h with or without STS. (A) Cell extracts were prepared and fractionated into soluble (S), light-membrane (L), and HM (H) fractions. Aliquots from each fraction normalized to cell equivalents were monitored for the presence of transfected HA-Bax (WT or mutant) and for endogenous Bcl-2 protein by immunoblot analysis using rat monoclonal anti-HA and polyclonal anti-human Bcl-2 antibodies, respectively. (B) Mitochondrion-enriched HM pellets were resuspended in either Na2CO3 (pH 11.5) or mitochondrial isolation buffer (pH 7.4). After 30 min of incubation on ice, the mitochondria were pelleted and resuspended in Laemmli sample buffer. Equal proportions of the mitochondrial supernatants (S) and pellets (P) were analyzed by immunoblotting and probing for the presence of HA-Bax (WT or mutant), COX-II (inner membrane), or Hsp60 (matrix or soluble). +, present; −, absent.

As shown in Fig. 6, mutant Bax-B has a punctate localization throughout the cytoplasm in healthy cells, consistent with the presence of both soluble and membrane-bound Bax-B protein detected in subcellular fractionation experiments (Fig. 7A). However, in apoptotic cells, GFP–Bax-B becomes solely concentrated on mitochondria such that the distributions of mutant and WT Bax become indistinguishable under these conditions (Fig. 6). It has been suggested that in response to apoptotic stimuli, a fraction of soluble Bax localizes to mitochondria and the remaining soluble Bax is removed by proteolysis (5). Thus, the difference in the cellular distributions of GFP–Bax-B protein in healthy and apoptotic cells might be due to proteolysis of the fraction of Bax that remains soluble after receipt of an apoptotic signal. Alternatively, the fraction of soluble Bax-B might undergo a conformational change and translocate to mitochondria in apoptotic cells. Nevertheless, the combined data presented in Fig. 6 and 7 indicate that, unlike WT Bax, a large fraction of mutant Bax-B protein constitutively localizes to mitochondria, correlating with a gain-of-function phenotype.

The mutant Bax-F reveals a dual function for the α5-α6 domain.

Having evaluated the effects of the Bax mutants (B and C) which contained fewer alanine replacements and which retained cytotoxic activity in yeast, we next turned our attention to the Bax-F mutant, which displayed a loss-of-function phenotype in yeast (Fig. 2) and in which 8 out of 10 charged residues in the α5-α6 domain of Bax had been neutralized. In contrast to the results obtained in yeast, when expressed by transient transfection in 293T and Cos-7 cells, a GFP-tagged Bax-F mutant displayed a gain-of-function phenotype (Fig. 8) and constitutive localization to cellular membranes (not shown). Similar to Bax mutants B and C, Bax-F showed enhanced cytotoxic activity which was suppressed by Bcl-XL (not shown) but not by zVAD-fmk (Fig. 8C).

FIG. 8.

Apoptotic and cytotoxic activity of Mutant Bax F in mammalian cells. (A and B) Mutant Bax F displays a gain-of-function phenotype in mammalian cells. Plasmids encoding GFP-tagged WT, mutant F, mutant F+BH3, or mutant BH3 (D68A) Bax were transfected into 293T (A) and Cos-7 (B) cells and assayed for apoptosis 5 (A) and 16 (B) h posttransfection, respectively. Protein expression was tested in 293T cells (A, bottom) using either 5 (lanes 1, 3, 5, and 7) or 10 (lanes 2, 4, 6, and 8) μg of protein from extracts of cells transfected with plasmids encoding GFP-Bax (lanes 1 and 2), GFP-F (lanes 3 and 4), GFP-(F+BH3) (lanes 5 and 6), or GFP-BH3 (lanes 7 and 8). For measurement of protein expression in Cos-7 cells (B, bottom), 10 μg of proteins from cells expressing GFP-Bax (lane 1), GFP-F (lane 2), GFP-(F+BH3) (lane 3), or GFP-BH3 (lane 4) was analyzed. Antigen detection for both 293T and Cos-7 extracts was accomplished using monoclonal anti-GFP antibody. (C) zVAD-fmk inhibits the apoptotic, but not the cytotoxic, activity of mutant F. Plasmid DNA was transfected into 293T cells, and zVAD-fmk (100 μM) was added to the cell culture medium 2 h posttransfection. Apoptosis and cytotoxicity were measured by DAPI staining and PI dye exclusion assays, respectively, 48 h posttransfection. The error bars indicate standard deviation. +, present; −, absent.

Since the cytotoxic activity of Bax in yeast has been attributed to the intrinsic pore-forming activity of Bax, we considered the possibility that the gain-of-function phenotype of Bax mutant F in mammalian cells relates to its ability to bind antiapoptotic Bcl-2 family proteins which are not present in yeast. To test this hypothesis, we made a combination mutant (F+BH3) in which the F mutation was combined with an alanine substitution for the D68 residue in the BH3 domain. Previously, it has been shown that the BH3 domain is the minimal region of Bax required for binding to antiapoptotic Bcl-2 proteins and that a D68A substitution greatly inhibits this interaction (44, 49, 51). The apoptotic activity of the GFP-tagged F+BH3 mutant was compared to that of GFP-tagged WT Bax, Bax-F, and Bax-D68A mutants by transient transfection in 293T and Cos-7 cells.

As shown in Fig. 8, the F+BH3 combination mutant exhibited reduced apoptotic and cytotoxic activity compared to the F mutant in 293T and Cos-7 cells. This reduced activity was not attributable to a change in cellular distribution (not shown) or to impaired production of Bax-(F+BH3) protein, as determined by immunoblot analysis (Fig. 8). However, in both 293T and Cos-7 cells, the F+BH3 mutant retained some killing activity, despite disruption of its BH3 domain and neutralization of most charged residues in its α5-α6 region.

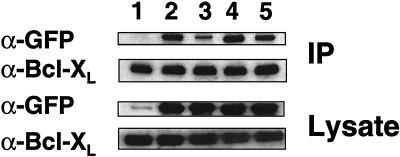

In an effort to probe the mechanism responsible for the enhanced function of the Bax-F mutant and the residual activity of the Bax-(F+BH3) mutant, we performed coimmunoprecipitation experiments exploring the association of these mutants with Bcl-XL. For these experiments, Cos-7 cells were transiently transfected with plasmids encoding GFP, GFP-Bax, GFP–Bax-F, GFP–Bax-BH3, or GFP–Bax-(F+BH3), along with FLAG-tagged Bcl-XL. Immunoprecipitations were then performed with anti-FLAG antibody, and the resulting immune complexes were analyzed for associated Bax protein by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis immunoblotting. As shown in Fig. 9, the BH3 domain D68A mutation greatly reduced the interaction of Bax with Bcl-XL (compare lanes 2 and 3), as previously reported (51). However, when examined in combination with the F mutations, the BH3 domain D68A mutation only partially reduced interaction with Bcl-XL, compared to WT Bax (Fig. 9, lane 5). Moreover, the Bax mutant F displayed enhanced interaction with Bcl-XL compared to that of WT Bax (Fig. 9, compare lanes 2 and 4). These observations correlate with the inability of the BH3 domain D68A mutation to completely abolish the apoptotic activity of Bax when combined with the α5-α6 mutant F and provide an explanation for the gain-of-function phenotype of mutant F, despite its lack of cytotoxic activity in yeast.

FIG. 9.

The gain-of-function phenotype of Bax mutant F correlates with increased binding to Bcl-XL. Cos-7 cells were transfected with pcDNA3 encoding FLAG-tagged Bcl-XL, along with plasmids encoding GFP (lane 1) or GFP fusions of WT Bax (lane 2) or Bax mutant F (lane 4), F+BH3 (lane 5), or BH3 (lane 3). Cell extracts were subjected to immunoprecipitation with a monoclonal antibody to the FLAG epitope. The immune complexes and 1/40 of the extract used for coimmunoprecipitations were analyzed by immunoblotting, using a monoclonal antibody to GFP and a polyclonal anti-human Bcl-XL antiserum. IP, immunoprecipitate.

DISCUSSION

The α5-α6 helical hairpin of Bax has been implicated in the formation of ion-conducting channels in cellular membranes, by analogy to prior work performed with structurally similar bacterial toxins (3, 23). The analogous α-helices of colicins have been shown to insert into membranes, based on electron paramagnetic resonance and fluorescence probe studies (3). Accordingly, the presence of charged residues in the α5-α6 region of Bax imposes certain restrictions on the membrane-inserted state of this protein. One of these is that energetic barriers exist to attaining the membrane-inserted state, since polar residues must be driven into an apolar environment. Second, once inserted into the membrane, the charged residues, residing on one face of each of the amphipathic α-helices in the α5-α6 domain, must be somehow shielded from the lipid bilayer. The most straightforward mechanism for accomplishing this shielding is by directing the polar face of the membrane-inserted α-helices towards the aqueous lumen of a channel and having two or more Bax molecules collaborate by contributing pairs of α-helices that can form a ring around this lumen (reviewed in references 28 and 36). Presumably, this highly charged aqueous lumen would participate in the channel formation and cytotoxicity of Bax by allowing passage of ions through the membrane. We predicted, therefore, that neutralizing charged residues in the α5-α6 region of Bax should make it easier for the protein to attain a membrane-inserted state but also might impair its ability to form ion-permeable cytotoxic channels. The systematic alanine substitutions reported here support these concepts but also reveal previously unidentified functions for the α5-α6 helical hairpin of Bax.

α5-α6 helical hairpin of Bax as regulator of membrane insertion.

We have shown that neutralization of as little as two charges in the α5 helix of Bax allows the protein to localize to cellular membranes, including mitochondria. Mitochondria represent a major site of action of Bcl-2 family proteins. Although the antiapoptotic proteins Bcl-2 and Bcl-XL are predominantly localized to mitochondria and other cellular membranes (46), the proapoptotic protein Bax is normally cytosolic and migrates to the mitochondria in response to undefined apoptotic signals (11, 20, 46). Previous mutational analysis, aimed at determining the regulatory event(s) leading to mitochondrial localization of Bax, have concentrated on the C-terminal hydrophobic domain (TM domain) of this protein (6, 30). The results of these studies suggest that an interaction between the TM domain and the N-terminal first 20 amino acids of Bax prevents Bax from localizing to mitochondria and that a conformational change disrupts this interaction, leading to mitochondrial targeting and membrane insertion (6, 30). The work presented here implicates the charged residues in the α5 helix of Bax as additional determinants of mitochondrial localization. Since the K119A and K123A substitutions in the α5 helix of Bax resulted in mitochondrial localization of a large fraction of mutant B and led to enhanced apoptotic activity, we suggest that either or both of the positively charged residues K119 and K123 are required for maintaining Bax in an aqueous-soluble state. Similar mutational analysis of the membrane insertion α-helical hairpin of diphtheria toxin has shown that substitution of positively charged residues for acidic residues in the loop connecting the two α-helices in this domain (α-helices 8 and 9) blocks membrane insertion (41). This suggests that the presence of positively charged residues is inhibitory for membrane insertion and is consistent with the previously documented energetic unfavorability of inserting positively charged residues into membranes (18). Interestingly, previous studies have shown that enforced dimerization of Bax leads to mitochondrial localization and apoptosis in the absence of external apoptotic stimuli (8, 44). Conceivably, therefore, Bax homodimerization might additionally promote membrane insertion by masking positive charges within the α5-α6 domain.

The α5-α6 helical hairpin as regulator of intrinsic cytotoxic activity of Bax.

The cytotoxic activity of Bax in yeast has been attributed to the intrinsic pore-forming capacity of Bax, based on the observation that deletion of the α5-α6 region nullifies the ability of Bax to induce cell death in yeast (23) and due to the absence of Bcl-2 homologues in yeast (reviewed in references 7 and 33). Furthermore, it has recently been shown that Bax functionally interacts with other evolutionarily conserved channel proteins resident in mitochondrial membranes, such as VDAC, ANT, and the F0F1 ATPase proton pump, in both yeast and mammalian cells (22, 24, 29, 42). Bax mutants B and C, which largely localize to mitochondria, display gain-of-function phenotypes in both mammalian cells and the Bax-resistant mutant yeast strain Brm-1. Thus, we hypothesize that enhanced membrane insertion facilitates channel formation or interaction with the above-mentioned mitochondrial channel proteins. Since mutant F constitutively localizes to mitochondria but lacks lethal activity in yeast, we predict that this protein is defective in channel activity and/or interaction with other mitochondrial channel proteins. Despite substantial effort, we have been unable to produce any of the Bax mutants as recombinant proteins suitable for direct measurement of channel activity, precluding the determination of the precise biochemical activities that are responsible for the gain-of-function phenotype of mutants B and C and the loss-of-function phenotype of mutant F in yeast.

The α5-α6 region of Bax as a regulator of interactions with Bcl-XL.

Previous studies have suggested that Bax has two mechanisms for killing mammalian cells: one linked to its intrinsic function as a channel-forming or membrane-inserted protein mediated by its α5-α6 region and the other attributable to its ability to dimerize with proapoptotic Bcl-2 family proteins through its BH3 domain, nullifying their cell survival functions (44, 47, 49). Thus, ablating either of these mechanisms individually through mutagenesis of the Bax protein is insufficient to abolish its proapoptotic function in mammalian cells. Despite lacking activity in yeast-killing assays, mutant Bax F, in which 8 of 10 charged residues in α5-α6 were neutralized, displayed a gain-of-function phenotype in mammalian cells. Inasmuch as the Bax-F mutant would be expected to lack intrinsic pore-forming activity, we presumed that the ability of Bax-F to kill mammalian cells but not yeast reflected the BH3-dependent mechanism of killing by Bax. However, when the BH3 domain in Bax-F was mutated (D68A) in a way previously shown to greatly reduce interactions of the WT Bax protein with Bcl-2 and Bcl-XL (51), the resulting Bax-(F+BH3) mutant protein still retained substantial apoptotic activity. Our attempts to explore the basis for retention of activity by the Bax-(F+BH3) protein have revealed that it retains the ability to associate with Bcl-XL in coimmunoprecipitation assays. Thus, whereas the BH3 mutation (D68A) greatly reduces binding to Bcl-XL within the context of the otherwise WT Bax protein (51), it does not prevent association with Bcl-XL within the context of the Bax-F protein. Moreover, the Bax-F protein displayed enhanced association with Bcl-XL compared to that of WT Bax, suggesting that alanine substitution neutralization of charged residues in the α5-α6 region of Bax facilitates its interaction with antiapoptotic Bcl-2 family proteins.

The reasons for the apparently enhanced interaction of Bax-F with Bcl-XL remain to be elucidated. One possibility is that the superior membrane-inserting ability of Bax-F compared to WT Bax allows it to more fully expose the amphipathic face of its BH3 domain, which has been shown to be involved in dimerizing with antiapoptotic Bcl-2 family proteins. Accordingly, perhaps the D68A mutation within the BH3 domain is no longer an impediment to BH3-mediated dimerization in this setting. Alternatively, recent chemical cross-linking studies and other investigations have suggested that membrane-inserted Bax and Bcl-2 or Bcl-XL may physically interact in membranes in a BH3-independent fashion (44). By favoring membrane insertion, therefore, it is possible that the neutralizing alanine substitution mutations in the α5-α6 region of the Bax-F protein enhance this BH3-independent association of Bax with antiapoptotic proteins, such as Bcl-XL, affording the protein a gain-of-function phenotype. This putative enhanced interaction of the membrane-inserted forms of Bax and Bcl-XL hypothetically could abrogate or modify the intrinsic channel activity of the Bcl-XL protein (44) or could improve the ability of Bax to compete with Bcl-XL for interactions with other proteins in mitochondrial membranes, such as VDAC or ANT (22, 29, 42). Further investigations are required to distinguish among these possible explanations for the data presented here and to further delineate the mechanisms of the Bax protein function.

Conclusions.

The results reported here support prior suggestions that the Bax protein has a dual mechanism of action: (i) formation of pores in cellular membranes, attributed to the putative pore-forming α5-α6 region, and (ii) heterodimerization with antiapoptotic Bcl-2 family members through the BH3 domain of Bax. Our results, however, also suggest that the α5-α6 domain participates in or regulates interactions of Bax with antiapoptotic Bcl-2 family proteins, such as Bcl-XL, and that it influences mitochondrial targeting. It remains to be determined whether the α5-α6 domain of Bax participates directly in interaction of the membrane-inserted Bax protein with other integral membrane proteins, such as components of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore complex.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the University of California Tobacco Related Disease Research Program (grant 7FT-0100) and NIH (GM60554) for generous support.

REFERENCES

- 1.Antonsson B, Conti F, Ciavatta A, Montessuit S, Lewis S, Martinou I, Bernasconi L, Bernard A, Mermod J-J, Mazzei G, Maundrell K, Gambale F, Sadoul R, Martinou J-C. Inhibition of Bax channel-forming activity by Bcl-2. Science. 1997;277:370–372. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5324.370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chou J, Li H, Salvesen G, Yuan J, Wagner G. Solution structure of BID, an intracellular amplifier of apoptotic signaling. Cell. 1999;96:615–624. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80572-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cramer W A, Heymann J B, Schendel S L, Deriy B N, Cohen F S, Elkins P A, Stauffacher C V. Structure-function of the channel-forming colicins. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 1995;24:611–641. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bb.24.060195.003143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Deckwerth T L, Elliott J L, Knudson C M, Johnson E M, Jr, Snider W D, Korsmeyer S J. BAX is required for neuronal death after trophic factor deprivation and during development. Neuron. 1996;17:401–411. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80173-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Desagher S, Osen-Sand A, Nichols A, Eskes R, Montessuit S, Lauper S, Maundrell K, Antonsson B, Martinou J-C. Bid-induced conformational change of Bax is responsible for mitochondrial cytochrome c depletion during apoptosis. J Cell Biol. 1998;144:891–901. doi: 10.1083/jcb.144.5.891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goping I, Gross A, Lavoie J, Nguyen M, Jemmerson R, Roth K, Korsmeyer S, Shore G. Regulated targeting of BAX mitochondria. J Cell Biol. 1998;143:207–215. doi: 10.1083/jcb.143.1.207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Green D, Reed J. Mitochondria and apoptosis. Science. 1998;281:1309–1312. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5381.1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gross A, Jockel J, Wei M, Korsmeyer S. Enforced dimerization of Bax results in its translocation, mitochondrial dysfunction and apoptosis. EMBO J. 1998;17:3878–3885. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.14.3878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Han J, Sabbatini P, Perez D, Rao L, Modha D, White E. The E1B 19K protein blocks apoptosis by interacting with and inhibiting the p53-inducible and death-promoting Bax protein. Genes Dev. 1996;10:461–477. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.4.461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ho S, Hunt H, Horton R, Pullen J, Pease L. Site-directed mutagenesis by overlap extension using the polymerase chain reaction. Gene. 1989;77:51–59. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(89)90358-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hsu Y-T, Wolter K G, Youle R J. Cytosol-to-membrane redistribution of Bax and Bcl-XL during apoptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:3668–3672. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.8.3668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hsu Y T, Youle R J. Nonionic detergents induce dimerization among members of the Bcl-2 family. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:13829–13834. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.21.13829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jurgensmeier J, Krajewski S, Armstrong R, Wilson G, Oltersdorf T, Fritz L, Reed J, Ottilie S. Bax- and Bak-induced cell death in the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Mol Biol Cell. 1997;8:325–339. doi: 10.1091/mbc.8.2.325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jurgensmeier J M, Xie Z, Deveraux Q, Ellerby L, Bredesen D, Reed J C. Bax directly induces release of cytochrome c from isolated mitochondria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;5:4997–5002. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.9.4997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Knudson C M, Tung K S K, Tourtellotte W G, Brown G A J, Korsmeyer S J. Bax-deficient mice with lymphoid hyperplasia and male germ cell death. Science. 1995;270:96–99. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5233.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krajewski S, Krajewska M, Shabaik A, Miyashita T, Wang H-G, Reed J C. Immunohistochemical determination of in vivo distribution of Bax, a dominant inhibitor of Bcl-2. Am J Pathol. 1994;145:1323–1333. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krajewski S, Krajewska M, Shabaik A, Wang H-G, Irie S, Fong L, Reed J C. Immunohistochemical analysis of in vivo patterns of Bcl-X expression. Cancer Res. 1994;54:5501–5507. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krishtalik L I, Cramer W A. On the physical basis for the cis-positive rule describing protein orientation in biological membranes. FEBS Lett. 1995;369:140–143. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)00756-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lewis S, Bethell S, Patel S, Martinou J-C, Antonsson B. Purification and biochemical properties of soluble recombinant human Bax. Protein Expr Purif. 1998;13:120–126. doi: 10.1006/prep.1997.0871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li H, Zhu H, Xu C, Yuan J. Cleavage of BID by caspase 8 mediates the mitochondrial damage in the Fas pathway of apoptosis. Cell. 1998;94:491–501. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81590-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Manon S, Chaudhuri B, Buérin M. Release of cytochrome c and decrease of cytochrome c oxidase in Bax-expressing yeast cells, and prevention of these effects by coexpression of Bcl-XL. FEBS Lett. 1997;415:29–32. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)01087-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marzo I, Brenner C, Zamzami N, Jurgensmeier J M, Susin S A, Vieira H L A, Prevost M-C, Xie Z, Matsuyama S, Reed J C, Kroemer G. Bax and adenine nucleotide translocator cooperate in the mitochondrial control of apoptosis. Science. 1998;281:2027–2031. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5385.2027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Matsuyama S, Schendel S, Xie Z, Reed J. Cytoprotection by Bcl-2 requires the pore-forming α5 and α6 helices. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:30995–31001. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.47.30995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Matsuyama S, Xu Q, Velours J, Reed J C. The mitochondrial F0F1-ATPase proton pump is required for function of proapoptotic protein Bax in yeast and mammalian cells. Mol Cell. 1998;1:327–336. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80033-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McDonnell J, Fushman D, Milliman C, Korsmeyer S, Cowburn D. Solution structure of the proapoptotic molecule BID: a structural basis for apoptotic agonists and antagonists. Cell. 1999;96:625–634. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80573-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Minn A J, Velez P, Schendel S L, Liang H, Muchmore S W, Fesik S W, Fill M, Thompson C B. Bcl-xL forms an ion channel in synthetic lipid membranes. Nature. 1997;385:353–357. doi: 10.1038/385353a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miyashita T, Krajewski S, Krajewska M, Wang H G, Lin H K, Hoffman B, Lieberman D, Reed J C. Tumor suppressor p53 is a regulator of BCL-2 and BAX in gene expression in vitro and in vivo. Oncogene. 1994;9:1799–1805. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Montal M. Protein folds in channel structure. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 1996;6:499–510. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(96)80115-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Narita M, Shimizu S, Ito T, Chittenden T, Lutz R J, Matsuda H, Tsujimoto Y. Bax interacts with the permeability transition pore to induce permeability transition and cytochrome c release in isolated mitochondria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:14681–14686. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.25.14681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nechushtan A, Smith C, Hsu Y-T, Youle R. Conformation of the Bax C-terminus regulates subcellular location and cell death. EMBO J. 1999;18:2330–2341. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.9.2330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oltvai Z, Milliman C, Korsmeyer S. Bcl-2 heterodimerizes in vivo with a conserved homolog, Bax, that accelerates programmed cell death. Cell. 1993;74:609–619. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90509-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pastorino J G, Chen S T, Tafani M, Snyder J W, Farber J L. The overexpression of Bax produces cell death upon induction of the mitochondrial permeability transition. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:7770–7775. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.13.7770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reed J. Bcl-2 family proteins. Oncogene. 1998;17:3225–3236. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sato T, Hanada M, Bodrug S, Irie S, Iwama N, Boise L H, Thompson C B, Golemis E, Fong L, Wang H-G, Reed J C. Interactions among members of the Bcl-2 protein family analyzed with a yeast two-hybrid system. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:9238–9242. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.20.9238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sattler M, Liang H, Nettesheim D, Meadows R P, Harlan J E, Eberstadt M, Yoon H S, Shuker S B, Chang B S, Minn A J, Thompson C B, Fesik S W. Structure of Bcl-xL-Bak peptide complex: recognition between regulators of apoptosis. Science. 1997;275:983–986. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5302.983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schendel S, Montal M, Reed J C. Bcl-2 family proteins as ion-channels. Cell Death Differ. 1998;5:372–380. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schendel S L, Azimov R, Powlowski K, Godzik A, Kagan B L, Reed J C. Ion channel activity of the BH3 only Bcl-2 family member, BID. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:21932–21936. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.31.21932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schendel S L, Xie Z, Montal M O, Matsuyama S, Montal M, Reed J C. Channel formation by antiapoptotic protein Bcl-2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:5113–5118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.10.5113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schlesinger P, Gross A, Yin X-M, Yamamoto K, Saito M, Waksman G, Korsmeyer S. Comparison of the ion channel characteristics of proapoptotic BAX and antiapoptotic BCL-2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:11357–11362. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.21.11357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shimizu Y, Narita M, Tsujimoto Y. Bcl-2 family proteins regulate the release of apoptogenic cytochrome c by the mitochondrial channel VDAC. Nature. 1999;399:483–487. doi: 10.1038/20959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Silverman J A, Mindell J A, Finkelstein A, Shen W H, Collier R J. Mutational analysis of the helical hairpin region of diphtheria toxin transmembrane domain. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:22524–22532. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vander Heiden M, Chandel N, Schumacker P, Thompson C. Bcl-XL prevents cell death following growth factor withdrawal by facilitating mitochondrial ATP/ADP exchange. Mol Cell. 1999;3:159–167. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80307-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang H G, Rapp U R, Reed J C. Bcl-2 targets the protein kinase Raf-1 to mitochondria. Cell. 1996;87:629–638. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81383-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang K, Gross A, Waksman G, Korsmeyer S J. Mutagenesis of the BH3 domain of Bax identifies critical residues for dimerization and killing. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:6083–6089. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.10.6083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang K, Yin W-M, Chao D T, Milliman C L, Korsmeyer S J. BID: a novel BH3 domain-only death agonist. Genes Dev. 1996;10:2859–2869. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.22.2859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wolter K G, Hsu Y T, Smith C L, Nechushtan A, Xi X G, Youle R J. Movement of Bax from the cytosol to mitochondria during apoptosis. J Cell Biol. 1997;139:1281–1292. doi: 10.1083/jcb.139.5.1281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Xiang J, Chao D T, Korsmeyer S J. BAX-induced cell death may not require interleukin 1β-converting enzyme-like proteases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:14559–14563. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.25.14559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yin X M, Oltvai Z N, Korsmeyer S J. BH1 and BH2 domains of Bcl-2 are required for inhibition of apoptosis and heterodimerization with Bax. Nature. 1994;369:321–323. doi: 10.1038/369321a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zha H, Aime-Sempe C, Sato T, Reed J C. Pro-apoptotic protein Bax heterodimerizes with Bcl-2 and homodimerizes with Bax via a novel domain (BH3) distinct from BH1 and BH2. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:7440–7444. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.13.7440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zha H, Fisk H, Yaffe M, Mahajan N, Herman B, Reed J. Structure-function comparisons of proapoptotic protein Bax in yeast and mammalian cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:6494–6508. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.11.6494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zha H, Reed J C. Heterodimerization-independent functions of cell death regulatory proteins Bax and Bcl-2 in yeast and mammalian cells. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:31482–31488. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.50.31482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]