Abstract

The defining structural motif of the inhibitor of apoptosis (iap) protein family is the BIR (baculovirus iap repeat), a highly conserved zinc coordination domain of ∼70 residues. Although the BIR is required for inhibitor-of-apoptosis (IAP) function, including caspase inhibition, its molecular role in antiapoptotic activity in vivo is unknown. To define the function of the BIRs, we investigated the activity of these structural motifs within Op-IAP, an efficient, virus-derived IAP. We report here that Op-IAP1–216, a loss-of-function truncation which contains two BIRs but lacks the C-terminal RING motif, potently interfered with Op-IAP's capacity to block apoptosis induced by diverse stimuli. In contrast, Op-IAP1–216 had no effect on apoptotic suppression by caspase inhibitor P35. Consistent with a mechanism of dominant inhibition that involves direct interaction between Op-IAP1–216 and full-length Op-IAP, both proteins formed an immunoprecipitable complex in vivo. Op-IAP also self-associated. In contrast, the RING motif-containing truncation Op-IAP183–268 failed to interact with or interfere with Op-IAP function. Substitution of conserved residues within BIR 2 caused loss of dominant inhibition by Op-IAP1–216 and coincided with loss of interaction with Op-IAP. Thus, residues encompassing the BIRs mediate dominant inhibition and oligomerization of Op-IAP. Consistent with dominant interference by interaction with an endogenous cellular IAP, Op-IAP1–216 also lowered the survival threshold of cultured insect cells. Taken together, these data suggest a new model wherein the antiapoptotic function of IAP requires homo-oligomerization, which in turn mediates specific interactions with cellular apoptotic effectors.

The iap (inhibitor of apoptosis) genes function in phylogenetically diverse organisms to regulate apoptosis, a genetically programmed suicide response critical to normal development and tissue homeostasis (11, 25, 32, 44). The iap genes are evolutionarily conserved in vertebrates and invertebrates, as well as their viral pathogens (41). As the first discovered members of the iap family (5, 10), baculovirus iap genes function to suppress apoptotic death of the host cell and thereby enhance virus production (reviewed in reference 33). In Drosophila melanogaster, loss of function of the cellular iap designated diap1 causes inappropriate cell death during fly development (18, 49). In mammals, including humans, overexpression of c-iap1, c-iap2, xiap, and survivin is associated with neoplasia (1, 2, 24, 28, 29) and genetic lesions in naip are linked to the neurodegenerative disorder spinal muscular atrophy (36). Collectively, this evidence attests to a critical physiological role for viral and cellular IAPs.

The baculovirus iap repeat (BIR) is the defining sequence motif of the IAP protein family. Present in one to three tandem copies per protein, the ∼70-residue BIR is required for antiapoptotic activity (reviewed in references 11, 25, and 32). The BIR possesses a highly conserved C2HC arrangement of Cys and His residues which participates in tetrahedral coordination with Zn and contributes to a novel fold, as indicated by solution structure (21, 38). The BIR is also necessary for IAP interaction with diverse proapoptotic factors, including the invertebrate death inducers Reaper, Grim, Hid, and Doom from Drosophila and vertebrate and invertebrate members of the caspase family of death proteases (12, 13, 15, 23, 35, 40, 45, 46, 49). How the BIR participates in interactions with these different proteins and thereby contributes to IAP function is unknown. In addition to the BIR, some IAPs possess a C-terminal RING finger motif, a common Zn-binding motif which appears to be distinct in structure and function (reviewed in references 11, 25, and 32).

Current evidence suggests that IAPs act at conserved steps in the apoptotic-death pathway (reviewed in references 3, 11, 25, and 32). Mammalian c-IAP1, c-IAP2, XIAP, and Survivin and Drosophila DIAP1 interact with and inhibit select caspases in vitro, suggesting that these IAPs also inhibit active caspases in vivo (12, 13, 23, 35, 40, 49). Furthermore, ectopic overexpression of iap genes can prevent the proteolytic activation of caspases (13, 23, 30, 35, 37; D. J. LaCount, S. F. Hanson, C. L. Schneider, and P. D. Friesen, submitted for publication). Thus, the capacity of IAPs to interact with Reaper, Hid, and Grim and block an upstream step in apoptosis also suggests a mechanism of direct inactivation by association with these death inducers (16, 45, 46, 48). Similarly, c-IAP1 and c-IAP2 interact with and inhibit apoptosis induced by overproduction of Reaper and Grim in mammalian cells (31). However, recent genetic evidence from Drosophila suggests that Reaper, Hid, and Grim disrupt the anticaspase activity of DIAP1 (49). Thus, it remains unclear whether IAPs disrupt the function of these death inducers by direct interaction or whether the death inducers themselves inactivate IAP, which promotes caspase activation.

Op-iap is a potent inhibitor of apoptosis when expressed ectopically in both insect and mammalian cells. Derived from the baculovirus Orgyia pseudotsugata nucleopolyhedrovirus (5), Op-IAP is one of the smallest tandem BIR proteins. This 268-residue protein contains two BIRs and a C-terminal RING motif (Fig. 1). Op-IAP functions upstream of the universal caspase inhibitor P35 to prevent caspase activation (30, 37; LaCount et al., submitted). Moreover, Op-IAP prevents apoptosis induced by diverse signals, including UV radiation, virus infection, and overexpression of reaper, hid, grim, and doom (14, 15, 17, 18, 30, 42, 45, 46). Thus, Op-IAP functions at a central step in the death pathway. In addition, Op-IAP physically associates with death proteins Reaper, Hid, Grim, and Doom (15, 45, 46). Although its BIRs are necessary and sufficient for these interactions, the mechanism by which such association prevents caspase activation is unknown.

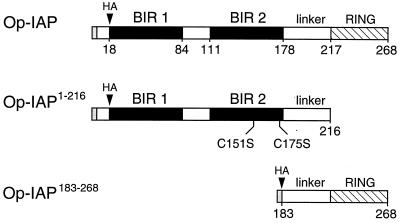

FIG. 1.

Structures of Op-IAP and truncations. Op-IAP (268 amino acids) contains two BIRs (black boxes) and a C-terminal RING finger motif (crosshatched). Truncation Op-IAP1–216 (residues 1 to 216) contains BIRs 1 and 2 plus the linker domain but lacks the RING finger. Truncation Op-IAP183–268 (residues 183 to 268) contains the linker and RING finger. Each protein contains Op-IAP residues 1 to 5 followed by the influenza virus HA epitope tag. Residues at the boundary of each motif are those previously described (18).

To define the molecular mechanism of IAP function, we investigated the contribution of BIR and RING motifs to the antiapoptotic activity of Op-IAP. The capacity of each motif to modulate cellular sensitivity to apoptosis was tested by using Spodoptera frugiperda SF21 cells, a lepidopteran cell line with a well-characterized apoptotic response (4, 7, 9, 26, 30, 37, 46, 48). In this study, we specifically used UV radiation and baculovirus infection as apoptotic stimuli since they are diverse signals and are physiologically relevant for SF21 cells. We report here that Op-IAP1–216, a loss-of-function truncation that contains BIRs 1 and 2 but lacks the RING finger, dominantly interfered with the capacity of full-length Op-IAP to suppress apoptosis. As demonstrated by immunoprecipitations, full-length Op-IAP formed oligomers with itself and with Op-IAP1–216. BIR-specific mutations caused loss of interaction and loss of dominant interference. These findings are consistent with a mechanism of dominant interference that involves direct interaction between Op-IAP and Op-IAP1–216 which may disrupt required interactions of Op-IAP with cellular apoptotic effectors. Taken together, these results provide the first evidence that the BIR motifs mediate IAP homophilic interactions which contribute to antiapoptotic activity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Op-iap plasmids.

Plasmid pIE1-Op-IAPHA/1–216, which encodes Op-IAP residues 1 to 216 with the influenza virus hemagglutinin (HA) epitope YPYDVPDYA inserted at residue 6, was constructed by PCR mutagenesis. In brief, pPRM−IAPHA (30) sequences were amplified by using Op-iap primers 5′-GCCGCAGTGTCCGTTTGT-3′ and 5′-GAGAGAGTCGACCTAGGTTACGCCACCTCCGCTTCAA-3′, which introduced a unique SalI site (underlined) and a stop codon after residue 216. The amplified fragment was digested with PshA1 and SalI and inserted into the corresponding sites of pPRM−IAPHA. A HindIII-SalI fragment was subsequently inserted into the corresponding sites of pIE1hr/PA (6) to generate pIE1-Op-IAPHA/1–216, in which the ie-1 promoter directed constitutive expression. To construct plasmid pIE1-Op-IAPHA/183–268, which encodes C-terminal Op-IAP residues 183 to 268 preceded by Op-IAP residues 1 to 5 and the HA epitope, the M13/T7 pBluescript primer (Stratagene) and Op-iap primer 5′-CACAAAGTCGCGGCCGCTAGCAGCGTAGTCT-3′ were used to amplify pPRM−IAPHA sequences. The resulting DNA was used with the Rev21 pBluescript primer to PCR amplify a fragment which was digested with BamHI and NruI and inserted into the corresponding sites of pPRM−IAPHA to generate pPRM−Op-IAPHA/183–268. The HindIII-SalI fragment of this plasmid was inserted into the corresponding sites of vector pIE1hr/PA to generate pIE1-Op-IAPHA/183–268. To construct pIE1-Op-IAPFLAG, a DNA fragment encoding the FLAG epitope (DYKDDDDK) was substituted for HA sequences of pPRM−IAPHA and the resulting PstI-SalI fragment was inserted into the corresponding sites of pIE1hr/PA. An XbaI-NotI fragment, including FLAG sequences, was inserted into the corresponding sites of pIE1-Op-IAPHA/1–216 to generate pIE1-Op-IAPFLAG/1–216. Op-IAP1–216 mutations (C151S and C175S) in which Cys151 or Cys175 was replaced with Ser were generated by PCR mutagenesis using mutagenic primers 5′-CTTTTGCAGTGACGGCGGTCTGAAGGAT-3′ and 5′-GCAGCACGTACTCTGAGCGGTCGTACCAGCGG-3′ and subcloning. All mutations were confirmed by nucleotide sequence analysis.

Cells and viruses.

S. frugiperda cell line IPLB-SF21 (43) was propagated at 27°C in TC100 growth medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (HyClone Laboratories) and 0.26% tryptose broth. Autographa californica nucleopolyhedrovirus (strain L1) recombinant viruses wt/lacZ, vΔp35/lacZ, vOp-IAP, and vOp-IAP/P35 were described previously (19, 30). For infection, SF21 monolayers were inoculated at the indicated multiplicity of infection (MOI). After 1 h, residual virus was replaced with supplemented TC100.

Plasmid transfections.

SF21 cells (2 × 106/60-mm-diameter plate) were washed three times with TC100 and incubated with a transfection mixture containing 10 μg of DOTAP {N-[1-(2,3-dioleoyloxy)propyl]-N,N,N-trimethylammonium methyl sulfate} and 2 μg of DNA plasmid in TC100. After 4 h at room temperature, the transfection mixture was replaced with supplemented TC100.

Generation of stably transfected SF21 cell lines.

Cells were transfected with pIE1-Op-IAPHA/1–216 and neomycin resistance plasmid pIE1-neo/PA as described previously (6). After selection for resistance to Geneticin (G418 sulfate; GIBCO-Bethesda Research Laboratories), pooled and cloned cell lines were obtained. Cloned lines were derived from individual cells by serial dilution. Nine of 12 isolated lines synthesized detectable levels of Op-IAPHA/1–216, as judged by HA.11-specific immunoblot analyses (see below). Stable Op-IAPHA cell lines C8, E6, and F6 were described previously (30).

DNA fragmentation assays.

SF21 cells were irradiated with UV-B by using a Blak Lamp (UVP, Upland, Calif.) or a UV-transilluminator (Fotodyne) as described previously (30). Low-molecular-weight DNA was collected at the indicated times from cells and associated apoptotic bodies (20). Isolated DNA was electrophoresed in 2% agarose–Tris-borate-EDTA gels and visualized by ethidium bromide staining.

Quantitation of apoptotic responses.

Following apoptotic stimulation by UV irradiation or virus infection of SF21 cell monolayers, cell survival was determined by counting viable, nonapoptotic cells using a Zeiss Axiovert 135TV phase-contrast microscope (magnification, ×200) equipped with a digital camera and IP Lab Spectrum P software. On the basis of extensive plasma membrane blebbing and cell body fragmentation, apoptotic SF21 cells were readily distinguished from viable cells in this assay. The mean ± standard deviation was calculated from the number of nonapoptotic cells (ranging from 600 to 1,100) counted in a total of eight evenly distributed fields of view.

Caspase assays.

Cells and apoptotic bodies were pooled, suspended in lysis buffer containing 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.0), 2 mM EDTA, 0.1% 3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonate (CHAPS), and 5 mM dithiothreitol along with a protease inhibitor cocktail (Boehringer Mannheim) for 20 min on ice. After clarification by centrifugation (16,000 × g), caspase activity was determined by using 10 μM Ac-DEVD-AMC (Peptides International) as the substrate in 100-μl reaction mixtures with protease buffer (25 mM HEPES [pH 7.5], 0.1% CHAPS, 10% sucrose, 1 mM EDTA, 10 mM dithiothreitol) and 0.005% bovine serum albumin. Fluorescent-product accumulation (excitation, 360 nm; emission, 465 nm) was monitored by using a Biolumin 960 Kinetic Fluorescence/Absorbance microplate reader (Molecular Dynamics). When necessary, lysates were diluted in lysis buffer to ensure assay linearity. All values are the averages of triplicate assays and are reported as the rate of product formation obtained from the linear portion of progress curves within the first 10% of substrate depletion.

Immunoprecipitations.

Cells (3 × 106) were collected ∼24 h after transfection, washed with phosphate-buffered saline (31), and lysed by suspension in 300 μl of immunoprecipitation buffer (10 mM CHAPS, 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM sodium phosphate [pH 7.1], 2 mM EDTA, 50 mM sodium fluoride containing protease inhibitor cocktail) for 45 min on ice. After clarification by centrifugation (16,000 × g) for 10 min at 4°C, 100 μl of lysate was mixed with 400 μl of immunoprecipitation buffer containing 6 μg of anti-FLAG M2 monoclonal antibody (Kodak). After 4 h on ice, immune complexes were collected by using protein G-Sepharose. After washing three times with immunoprecipitation buffer, proteins were eluted by boiling in 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)–2.5% β-mercaptoethanol.

Immunoblot analysis.

Whole-cell lysates, prepared by boiling in 1% SDS–1% β-mercaptoethanol, or immunoprecipitated proteins were electrophoresed on SDS–12.5% polyacrylamide gels. After protein transfer, membranes were incubated with monoclonal antibody HA.11 (BAbCO) or anti-FLAG M2 (Eastman Kodak) at dilutions of 1:1,000 and 1:300, respectively, followed by alkaline phosphatase-conjugated goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories). Signal development was performed by using nitroblue tetrazolium–5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolylphosphate (BCIP) colorimetric detection as described previously (20) or the Western-Star Chemiluminescent Detection System (Tropix).

Image processing.

Immunoblots and photographs were scanned at a resolution of 300 dots/in. by using a Hewlett-Packard ScanJetIIcx. The files were printed from Adobe Photoshop by using a Tektronics 450 dye sublimation printer.

RESULTS

The BIRs, but not the RING finger, dominantly interfere with Op-IAP function.

To investigate the individual contributions of BIR and RING motifs to IAP antiapoptotic activity, we first tested the capacity of each motif to affect cellular sensitivity to apoptotic stimuli. We constructed Op-iap truncations Op-iap1–216 and Op-iap183–268, which contain either the BIR motifs (BIRs 1 and 2) or the RING finger, respectively (Fig. 1). Each truncation was epitope (HA) tagged and placed under the control of the constitutively active ie-1 promoter for expression in S. frugiperda SF21 cells, which have a well-characterized apoptotic response to various stimuli (reviewed in references 8 and 33). Upon plasmid transfection, proteins Op-IAP1–216 (26 kDa) and OpIAP183–268 (11 kDa) were readily detected (Fig. 2A, lanes 5 and 9). Despite their relative abundance, both Op-IAP1–216 and Op-IAP183–268 failed to protect cells from signal-induced apoptosis. Upon UV irradiation, the levels of intracellular DNA fragmentation (Fig. 2B, lanes 5 and 9) and plasma membrane blebbing (data not shown) were comparable to those of cells transfected with the vector alone (lane 1). In contrast, previously generated SF21 cells (30) that constitutively synthesized full-length (31-kDa) Op-IAP (cell lines C8, E6, and F6) were fully protected from UV-induced apoptosis (Fig. 2B, lanes 2 to 4). Thus, consistent with previous studies using similar mutations (16, 42, 45), both Op-IAP truncations failed to prevent apoptosis.

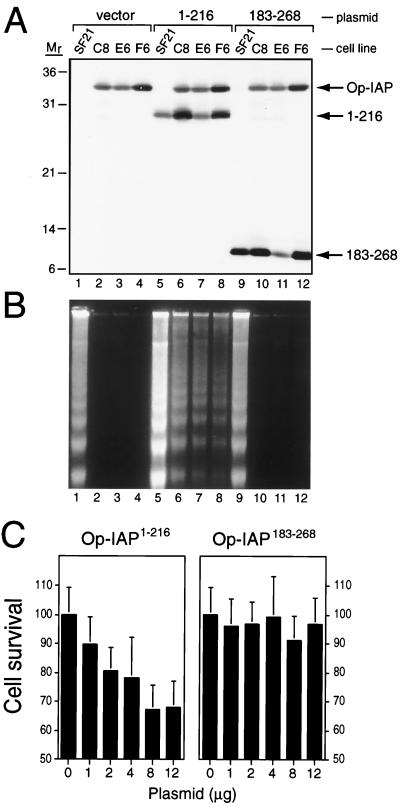

FIG. 2.

Op-IAP1–216 interference with Op-IAP-mediated suppression of UV-induced apoptosis. (A) Protein levels. Parental SF21 cells or stable SF21 lines C8, E6, and F6 that produce full-length Op-IAP were transfected with the vector alone (vector) or a plasmid encoding Op-IAPHA/1–216 or Op-IAPHA/183–268, respectively. Total cell lysates were prepared 18 h after transfection and subjected to immunoblot analysis by using HA-specific antiserum. Proteins Op-IAPHA, Op-IAPHA/1–216 (1–216), and Op-IAPHA/183–268 (183–268) and molecular mass (Mr) markers (sizes are in kilodaltons) are indicated. (B) DNA fragmentation. The cells were transfected with plasmids as indicated in panel A and UV irradiated 18 h later. Low-molecular-weight DNA was collected from cells and apoptotic bodies 12 h after irradiation and subjected to agarose gel electrophoresis in the presence of ethidium bromide. (C) Dose responses. Op-IAP-producing cell line F6 was transfected with increasing amounts of a plasmid encoding Op-IAPHA/1–216 (left) or Op-IAPHA/183–268 (right). A constant level of DNA was maintained by using the vector plasmid. Cells were UV irradiated 19 h after transfection. Cell survival was scored 26 h later and is reported as the average ± the standard deviation of viable cells relative to that of vector-transfected cells (normalized to 100). On the basis of reporter gene (lacZ) expression, about 50% of the SF21 population is transfected under these conditions (data not shown).

To determine if Op-IAP function was affected by these Op-IAP truncations, the stable Op-IAP cell lines C8, E6, and F6 were UV irradiated after transfection with plasmids encoding the Op-IAP motifs. The vector alone or a plasmid encoding Op-IAP183–268 had no effect on Op-IAP-mediated resistance to UV-induced apoptosis (Fig. 2B, lanes 2 to 4 and 10 to 12). In contrast, a plasmid encoding Op-IAP1–216 sensitized the three Op-IAP cell lines to apoptosis (Fig. 2B, lanes 6 to 8). The level of apoptotic death was proportional to the dosage of Op-IAP1–216 delivered by transfection and increased to include approximately 30% of the cell population (Fig. 2C, left). In contrast, Op-IAP183–268 failed to inhibit Op-IAP at all of the plasmid doses tested (Fig. 2C, right). Immunoblot analysis (Fig. 2A) indicated that Op-IAP1–216 did not affect the steady-state level of full-length Op-IAP in these cell lines. Thus, BIR-containing Op-IAP1–216, but not RING-containing Op-IAP183–268, interfered with the antiapoptotic activity of full-length Op-IAP.

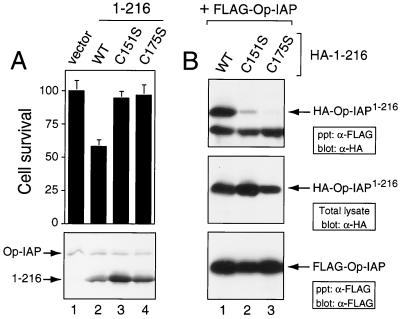

Constitutively synthesized Op-IAP1–216 inhibits Op-IAP but not P35.

To investigate dominant negative activity in a cell population constitutively expressing Op-IAP1–216, we generated stable Op-iap1–216 SF21 cell lines. After selection for neomycin resistance, both cloned and pooled cell lines were isolated in which Op-iap1–216 expression was directed by the constitutive ie-1 promoter (6). Immunoblot analysis indicated that the level of Op-IAP1–216 in cloned cell lines (Fig. 3A, lanes 5 to 7) was consistently higher than that in pooled cells (lane 4) but lower than that of full-length Op-IAP in stable cell lines (lane 3). Neither protein was detected in parental SF21 or control neomycin-resistant (Neor) cells (lanes 1 and 2). Consistent with our transient-expression data, constitutive synthesis of Op-IAP1–216 failed to prevent apoptosis since stable Op-IAP1–216 cell lines were as sensitive as parental and Neor cells to apoptosis induced by UV radiation and virus infection (data not shown).

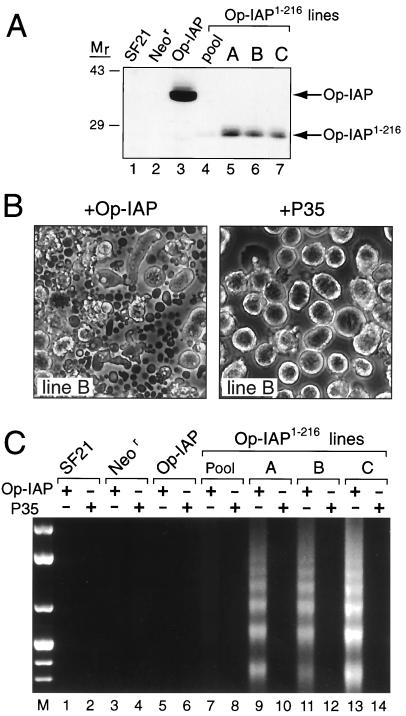

FIG. 3.

Effect of Op-IAP1–216 in stably transfected cell lines. (A) Op-IAP1–216 protein levels. Total cell lysates (2.5 × 105 cell equivalents) from pooled (lane 4) or cloned lines A, B, and C (lanes 5 to 7) stably transfected with Op-iapHA/1–216 were subjected to immunoblot analysis by using anti-HA serum. Lysates from parental SF21 (lane 1), Neor (lane 2), and Op-IAP line E6 (lane 3) cells were included. Molecular mass (Mr) markers (sizes are in kilodaltons) are indicated on the left. (B) Apoptosis by dominant inhibition of Op-IAP. Op-IAP1–216 cell line B was inoculated (MOI of 5) with A. californica nucleopolyhedrovirus recombinant vOp-IAP (+Op-IAP) or wt/lacZ (+P35) expressing either Op-iap or p35, respectively. Cells and apoptotic bodies were photographed 18 h later (original magnification, ×100). (C) DNA fragmentation. Pooled or cloned Op-IAP1–216 cell lines, along with SF21, Neor, and Op-IAP cells, were inoculated (MOI of 5) with virus vOp-IAP (Op-IAP) or wt/lacZ (P35). Low-molecular-weight DNA was quantified 24 h later as described in the legend to Fig. 2. DNA molecular weight markers (lane M) were included.

To assess the dominant negative effect of Op-IAP1–216 in stable cell lines, we used recombinant baculoviruses engineered to encode either full-length Op-IAP or caspase inhibitor P35. Baculovirus infection is a potent and uniform apoptotic stimulus (33). Thus, these recombinant viruses provided an efficient vehicle for delivery of functional apoptotic regulators to every cell signaled to undergo apoptosis, a process which is not possible when transient-transfection protocols are used. When infected with recombinant virus vOp-IAP which encodes Op-iap but lacks p35 (30), stable Op-IAP1–216 cell lines underwent widespread apoptosis that included >95% of each population (Fig. 3B, left panel). Intracellular DNA fragmentation was extensive (Fig. 3C, lanes 9, 11, and 13). Less apoptosis was detected in pooled Op-IAP1–216 cells (lane 7) in which intracellular levels of Op-IAP1–216 were reduced. In contrast, when stable Op-IAP1–216 cells were infected with a p35-expressing virus (wt/lacZ) (20) which lacks Op-iap, apoptosis was blocked (Fig. 3B, right panel) and DNA fragmentation was prevented (Fig. 3C, lanes 8, 10, 12, and 14). Parental SF21 and Neor cells failed to undergo apoptosis upon infection with vOp-IAP or the p35-expressing virus (Fig. 3C, lanes 1 and 3) due to the activity of functional Op-IAP or P35, respectively, as shown previously (20, 30). Similarly, apoptosis was blocked in stable Op-IAP cell lines following infection with vOp-IAP or the p35-expressing virus (Fig. 3C, lanes 5 and 6). These findings indicated that Op-IAP1–216 had no effect on the antiapoptotic activity of P35. Thus, Op-IAP1–216 likely acts upstream from this caspase inhibitor. In addition, these data demonstrated that Op-IAP1–216 interferes with the capacity of Op-IAP to prevent apoptosis induced by distinct signals, including virus infection and UV radiation.

Op-IAP synthesis or stability is not affected by Op-IAP1–216.

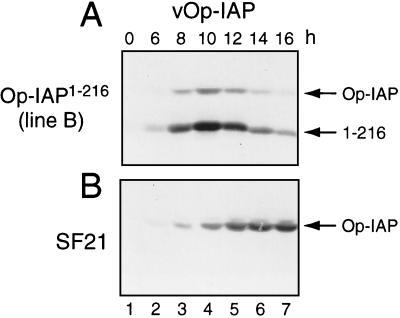

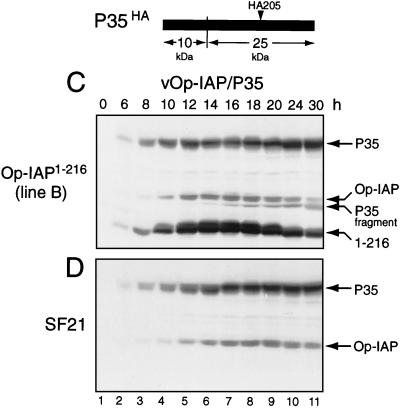

To define the mechanism by which Op-IAP1–216 interfered with Op-IAP, we first determined whether Op-IAP1–216 affected Op-iap expression following apoptotic signaling. Upon infection of stable Op-IAP1–216 cells with vOp-IAP, full-length Op-IAP was readily detected from 8 to 14 h (Fig. 4A). Consistent with dominant inhibition, the level of Op-IAP was lower than that of Op-IAP1–216, which was increased due to viral enhancement of the ie-1 promoter (6, 22). Through the first 10 h, Op-IAP levels in Op-IAP1–216 cell lines (Fig. 4A) were comparable to that in parental SF21 cells (Fig. 4B). However, by 12 h after infection, both proteins declined in Op-IAP1–216 cells (Fig. 4A). Since apoptosis was widespread by this time, the decline in protein levels was likely due to cellular degeneration. We therefore blocked apoptosis with P35 and determined the effect on protein levels by using recombinant virus vOp-IAP/P35, which encodes epitope (HA)-tagged P35 and Op-IAP (30). Upon infection with vOp-IAP/P35, Op-IAP1–216 cells failed to undergo apoptosis (see below). Moreover, the levels of both Op-IAP and Op-IAP1–216 were stabilized at late times after infection (Fig. 4C). We concluded that Op-IAP1–216 had no effect on intracellular levels of Op-IAP following apoptotic signaling and thus did not interfere with Op-IAP function by altering its expression or stability.

FIG. 4.

Stability of full-length Op-IAP during apoptosis. Op-IAP1–216 cell line B and parental SF21 cells were inoculated (MOI of 5) with virus vOp-IAP (A and B) or vOp-IAP/P35 (C and D). At the indicated times after infection, intact cells and associated apoptotic bodies were collected, lysed with SDS, and subjected to immunoblot analysis (2.5 × 105 cell equivalents) by using anti-HA serum. Proteins Op-IAPHA, Op-IAPHA/1–216 (1–216), and P35HA and the 25-kDa P35HA cleavage fragment are indicated at the right. The cleavage site and the position of the HA epitope within P35 encoded by vOp-IAP/P35 are shown.

Op-IAP fails to block caspase activation in the presence of Op-IAP1–216.

Current evidence indicates that Op-IAP functions upstream of substrate inhibitor P35 to block caspase activation or activity (30, 37; LaCount et al., submitted). We therefore predicted that Op-IAP1–216-mediated inhibition of Op-IAP would promote caspase activation upon apoptotic signaling. Since substrate P35 is a sensitive in vivo indicator of caspase activity (30), we monitored intracellular P35 cleavage in the absence and presence of Op-IAP1–216. Due to the upstream activity of Op-IAP, only full-length, uncleaved P35 was detected by immunoblot analysis of parental SF21 cells infected with vOp-IAP/P35 (Fig. 4D), as shown previously (30). However, the 25-kDa cleavage fragment of P35 appeared during infection of stable Op-IAP1–216 cells (Fig. 4C). This signature cleavage fragment was first detected between 12 and 14 h (Fig. 4C, lanes 5 to 6) and thus coincided with normal caspase activation during baculovirus infection (4; LaCount et al., submitted). Apoptosis of these cells was prevented due to the abundance of P35, which ensured complete inhibition of activated caspases. The appearance of caspase activity in stable Op-IAP1–216 cells, despite the presence of Op-IAP, demonstrated that Op-IAP1–216 interfered with Op-IAP's capacity to prevent caspase activation.

Op-IAP1–216 interacts with full-length Op-IAP.

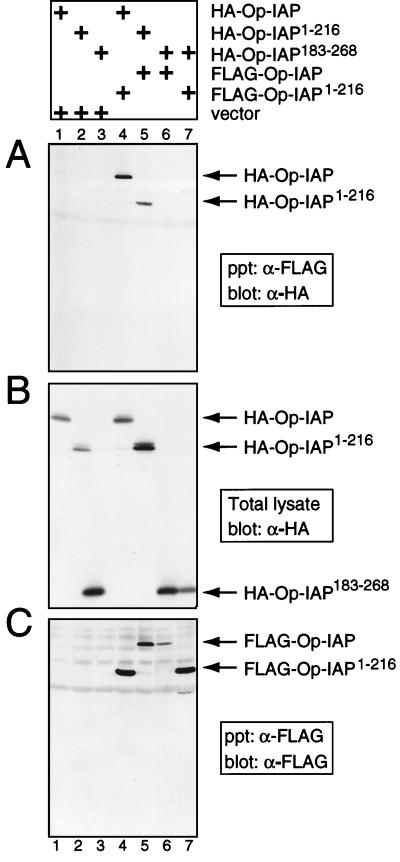

To define the molecular mechanism of dominant interference of Op-IAP, we first tested whether inhibition involves direct association of truncation Op-IAP1–216 with Op-IAP. Protein interactions were assessed by immunoprecipitations of differentially epitope-tagged proteins produced in plasmid-transfected SF21 cells. When proteins were coproduced by plasmid transfection, Op-IAP1–216, but not Op-IAP183–268, interfered with the capacity of Op-IAP to block apoptosis by virus infection and UV radiation (data not shown). Thus, each protein functioned as expected when synthesized transiently in this assay.

Immunoprecipitation of FLAG–Op-IAP1–216 from extracts of transfected cells by using anti-FLAG serum coprecipitated HA–Op-IAP (Fig. 5A, lane 4). In a reciprocal experiment, HA–Op-IAP1–216 also immunoprecipitated with full-length FLAG–Op-IAP (lane 5). Neither HA–Op-IAP nor HA–Op-IAP1–216 was precipitated in the absence of FLAG–Op-IAP1–216 or FLAG–Op-IAP, respectively (Fig. 5A, lanes 1 and 2). Moreover, RING-containing truncation HA–Op-IAP183–268 failed to immunoprecipitate either with FLAG–Op-IAP (lane 6) or with FLAG–Op-IAP1–216 (lane 7). In each case, the presence of the HA-tagged protein in cell extracts (Fig. 5B) and the precipitation of FLAG-tagged proteins (Fig. 5C) were verified by immunoblot analyses using anti-HA and anti-FLAG sera, respectively. Collectively, these data indicated that BIR-containing Op-IAP1–216, but not RING-containing Op-IAP183–268, is capable of forming a stable complex with full-length Op-IAP in SF21 cells.

FIG. 5.

Immunoprecipitation of Op-IAP and Op-IAP1–216. SF21 cells were transfected with plasmids (+) encoding the indicated epitope-tagged proteins or the vector alone, and extracts were prepared ∼24 h later. Proteins (106 cell equivalents) were immunoprecipitated (ppt) by using a FLAG-specific monoclonal antibody (α-FLAG) and subjected to immunoblot analysis by using either anti-HA (A) or anti-FLAG (C) serum. HA-tagged proteins in extracts (2.5 × 105 cell equivalents) prior to immunoprecipitation were quantified by immunoblot analysis using anti-HA serum (B).

Op-IAP homo-oligomerizes.

The dominant inhibition by Op-IAP1–216 and its association with full-length Op-IAP suggested that Op-IAP homo-oligomerizes and that this interaction is required for antiapoptotic function. To date, no evidence for IAP oligomerization has been reported. To test for Op-IAP homophilic interaction, we immunoprecipitated differentially tagged Op-IAPs from extracts of plasmid-transfected SF21 cells. Upon immunoprecipitation of FLAG–Op-IAP by using anti-FLAG serum, HA–Op-IAP was readily coprecipitated (Fig. 6A, lane 2). HA–Op-IAP was not precipitated in the absence of FLAG–Op-IAP (Fig. 6A, lane 1), despite its abundance in transfected cells (Fig. 6B, lane 1). In addition, immunoprecipitations detected interaction between BIR-containing truncations HA–Op-IAP1–216 and FLAG–Op-IAP1–216 (Fig. 6A, lane 4). Taking into account the reduced level of HA–Op-IAP1–216 present in these cell extracts (Fig. 6B, lane 4), the interaction between the truncated forms of Op-IAP was comparable to that between full-length forms of Op-IAP. These data indicated that the BIRs are sufficient for Op-IAP interaction and that the RING motif is not required. In an independent approach, Op-IAP oligomerization was confirmed by using the yeast two-hybrid assay in which Op-IAP fusions interacted strongly with each other (S. J. Zoog and P. D. Friesen, unpublished data). Collectively, these data indicated that Op-IAP forms homo-oligomers and that this interaction is mediated by Op-IAP domains encompassed by residues 1 to 216.

FIG. 6.

Intracellular oligomerization of Op-IAP. Immunoprecipitations of extracts from SF21 cells transfected with plasmids (+) encoding the indicated proteins or the vector alone were performed by using anti-FLAG (α-FLAG) serum as described in the legend to Fig. 5. The resulting complexes were subjected to immunoblot analysis with anti-HA (α-HA) (A) or anti-FLAG (C) serum. HA-tagged proteins in extracts (2.5 × 105 cell equivalents) prior to immunoprecipitation were quantified by immunoblot analysis using α-HA (B).

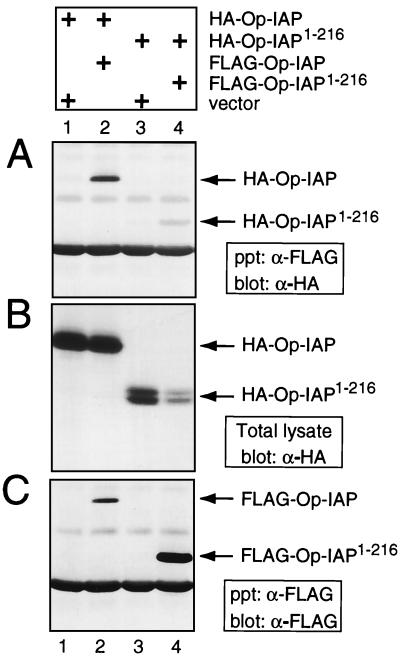

BIR mutations cause loss of Op-IAP1–216 interference and interaction.

To determine whether dominant inhibition requires Op-IAP1–216 interaction with Op-IAP, we examined the effects of mutational disruption of Op-IAP1–216. Since the BIRs possess a highly conserved arrangement of Zn-binding Cys and His residues, we generated C151S- and C175S-mutated versions of Op-IAP1–216 in which Ser was substituted for conserved Cys residues within BIR 2 (Fig. 1). Both C151S- and C175S-mutated Op-IAP1–216 proteins were synthesized at levels greater than or equal to that of Op-IAP (Fig. 7A and B). Whereas wild-type Op-IAP1–216 effectively inhibited Op-IAP's capacity to block virus-induced apoptosis, reducing cell survival by 50%, neither BIR-mutated Op-IAP1–216 had any effect on Op-IAP function (Fig. 7A). In particular, transfection with plasmids encoding the C151S and C175S substitutions failed to cause apoptosis of vOp-IAP-infected cells. Thus, these mutations caused loss of Op-IAP1–216 dominant inhibition. Likewise, both BIR mutations within Op-IAP1–216 disrupted its capacity to interact with full-length Op-IAP (Fig. 7B). Whereas HA-tagged Op-IAP1–216 wild type (WT) was readily immunoprecipitated with full-length, FLAG-tagged Op-IAP, the levels of coprecipitating C151S- and C175S-mutated Op-IAP1–216 were significantly reduced. The strong correlation between the loss of Op-IAP1–216 dominant inhibition and the disruption of Op-IAP1–216 interaction with Op-IAP supports a mechanism of oligomerization-mediated dominant interference.

FIG. 7.

Loss of dominant inhibition and interaction by Op-IAP1–216 mutations. (A) Dominant-inhibition assays. SF21 cells were transfected in duplicate with the vector alone or a plasmid encoding WT Op-IAPHA/1–216 or C151S- or C175S-mutated Op-IAPHA/1–216 and infected with vOp-IAP (MOI of 10) 18 h later. Cell survival was scored 24 h after infection and is reported as averages (± the standard deviation) relative to that of vector-transfected cells (normalized to 100). Cell lysates (2.5 × 105 cell equivalents) prepared 7.5 h after infection were subjected to immunoblot analysis by using anti-HA (α-HA) serum (lower panel). (B) Immunoprecipitations. SF21 cells were transfected with a plasmid encoding FLAG-tagged Op-IAP and WT or C151S- or C175S-mutated Op-IAPHA/1–216. Cell extracts prepared 16 h later were immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG (α-FLAG) serum. The resulting complexes were subjected to immunoblot analysis with anti-HA (top panel) or anti-FLAG (bottom panel) serum. HA-tagged proteins present prior to immunoprecipitation were quantified by using anti-HA serum (central panel).

Op-IAP1–216 sensitizes SF21 cells to apoptosis.

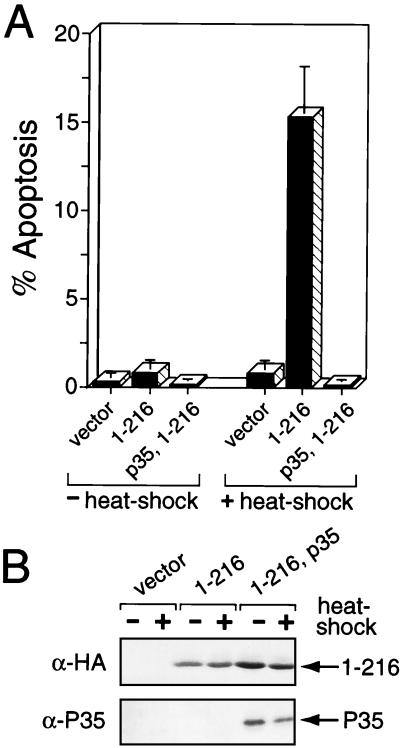

The finding that Op-IAP1–216 forms a complex with full-length Op-IAP raised the possibility that this BIR-containing truncation also interacts with and inhibits endogenous cellular IAPs. We predicted that these potential inhibitory interactions would increase cellular sensitivity to apoptosis. To investigate this prospect, we determined the effect of transient overexpression of Op-iap1–216 on the sensitivity of SF21 cells to undergo apoptosis induced by heat shock, a mild cellular stress. Transfection of Op-iap1–216 caused little (<5%) apoptosis of untreated cells (Fig. 8A). However, Op-iap1–216-transfected cells underwent a significant increase in apoptosis upon heat shock. By 3 h after heat shock, the level of apoptosis was 18-fold higher in Op-iap1–216-transfected cells than in untreated cells (Fig. 7A). Heat shock had no effect on cells transfected with the vector alone. Coexpression of caspase inhibitor p35 blocked the increase in cell death in Op-iap1–216-expressing cells, demonstrating that caspase-mediated cell death was involved. Immunoblot analysis (Fig. 8B) indicated that Op-IAP1–216 levels were not affected by heat shock and ruled out the possibility that increased synthesis of Op-IAP1–216 caused apoptosis. Thus, in the absence of Op-IAP, Op-IAP1–216 sensitized cells to stress-induced apoptosis. This finding is consistent with a modulation of cellular survival factors, including endogenous S. frugiperda IAPs, by the inhibitor Op-IAP1–216. Harvey et al. previously reported that heat shock promoter-driven expression of the Op-IAP BIRs caused apoptosis of SF21 cells (16). Our findings here indicate that the heat shock used to boost expression contributed to the observed cell death.

FIG. 8.

Stress-induced apoptosis by Op-IAP1–216. (A) Transient transfections. SF21 cells were transfected with the vector alone (vector) or a plasmid encoding Op-IAPHA/1–216 (1–216) or P35 (p35). After 18 h, transfected cells were incubated for 30 min at either 27°C (−heat shock) or 42°C (+heat shock) and scored 2.5 to 3 h later for apoptosis by microscopic visualization of cellular membrane blebbing. Reported values are averages ± the 95% confidence intervals of the percent apoptosis for a representative experiment. (B) Protein levels. Transfected cell lysates prepared 2 h after heat shock were subjected to immunoblot analysis by using anti-HA (α-HA) serum.

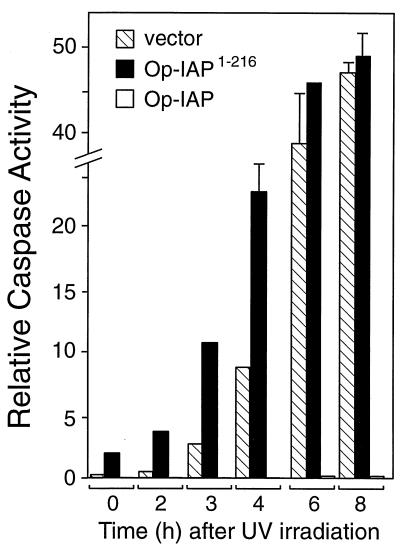

Op-IAP1–216 accelerates in vivo caspase activation.

To further examine the impact of Op-IAP1–216 on endogenous cell survival factors, we assessed the effect of Op-iap1–216 overexpression on sensitivity to apoptosis induced by a strong apoptotic stimulus, UV radiation. Upon UV irradiation of Op-iap1–216-transfected SF21 cells, the kinetics of cell death was accelerated. As measured by in vitro assays that used the tetrapeptide Ac-DEVD-AMC as a substrate, intracellular caspase activity appeared earlier in Op-iap1–216-transfected cells than in control cells (Fig. 9). Within the first 4 h after irradiation, Op-iap1–216-expressing cells contained 2- to 10-fold higher levels of caspase activity than vector-transfected cells. Consistent with this early caspase activation, Op-iap1–216 caused a more-than-twofold increase in apoptotic blebbing throughout this early period (data not shown). By 8 to 12 h after irradiation, >90% of cells with or without Op-IAP1–216 had undergone apoptosis and intracellular caspase activities were comparable (Fig. 8). In contrast, stable cells expressing functional Op-iap exhibited little, if any, caspase activity (Fig. 8) and were fully resistant to UV-induced apoptosis (30). These data indicated that overexpression of Op-iap1–216 reduced the time needed to initiate UV-induced cell death and suggested that Op-IAP1–216 affected normal antiapoptotic thresholds, possibly by interfering with cellular IAPs.

FIG. 9.

Op-IAP1–216 acceleration of caspase activation. SF21 cells were UV irradiated 18 h after transfection with a plasmid encoding Op-IAPHA/1–216 (solid bars) or the vector alone (striped bars). Cell extracts prepared immediately prior to irradiation (0 h) or at the indicated times after irradiation were assayed for caspase activity by using Ac-DEVD-AMC as the substrate. Relative caspase activities are averages ± the standard deviations of triplicate assays. Caspase activity in extracts from stably transfected Op-IAP cell line E6 after UV irradiation (open bars) was included.

DISCUSSION

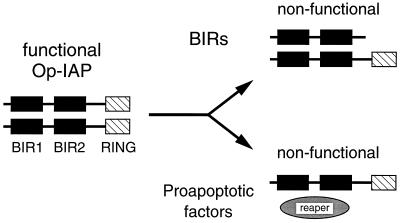

The BIRs are required for IAP antiapoptotic function. Although these Zn-binding motifs interact with a surprising diversity of proteins, which include proapoptotic factors and signaling complexes (12, 15, 34, 45, 46, 50), the contribution of these associations to antiapoptotic activity in vivo is unknown. We have shown here that Op-IAP residues 1 to 216, which include BIR motifs 1 and 2, are sufficient for Op-IAP self-association and when present in a RING-less truncation potently inhibit the antiapoptotic activity of Op-IAP. Our findings are consistent with a mechanism of dominant interference that involves direct interaction and inactivation of Op-IAP (Fig. 10). This mechanism suggests that BIR-mediated oligomerization contributes to Op-IAP function and that disruption of such homophilic interactions causes loss of Op-IAP antiapoptotic activity.

FIG. 10.

Model for dominant inhibition of oligomeric Op-IAP. Op-IAP exhibits antiapoptotic activity as an oligomeric complex through undefined interactions with downstream apoptotic effectors. The BIR-containing truncation Op-IAP1–216 dominantly interferes with Op-IAP by direct interaction, forming an inactive heterocomplex that lowers the survival threshold. By a similar mechanism, proapoptotic factors (invertebrate Reaper, Hid, and Grim) may interact with Op-IAP to form an inactive complex. The balance between proapoptotic factors (determined by the strength of the inductive signal) and endogenous IAP determines cell fate. During infection, the baculovirus prolongs cell survival by overproduction of Op-IAP, thereby overwhelming the death factor activity.

Mechanism of BIR-mediated inhibition of Op-IAP.

Although Op-IAP1–216 exhibited no antiapoptotic activity, this BIR-containing truncation interfered with the capacity of Op-IAP to prevent apoptosis induced by diverse stimuli, including UV radiation and virus infection (Fig. 2 and 3). Dominant inhibition was not limited to Op-IAP1–216, since we have found that other truncations that contain the complete BIR 1 and 2 motifs but lack the RING motif exhibit the same inhibitory effect (R. R. Hozak, unpublished data). In contrast, the RING-containing truncation Op-IAP183–268, which lacks the BIRs, failed to affect Op-IAP function (Fig. 2). We concluded that Op-IAP residues 1 to 216, including BIRs 1 and 2, are necessary and sufficient for dominant inhibition. None of the previously identified factors that associate with Op-IAP require the RING motif for interaction (15, 45, 46). Thus, the role of this C-terminal motif remains unknown.

Op-IAP1–216 eliminated Op-IAP's capacity to block caspase activation by a mechanism that did not affect the antiapoptotic activity of caspase inhibitor P35 (Fig. 4). Since Op-IAP acts upstream of P35 to block caspase activation (30, 37; LaCount et al., submitted), it is likely that Op-IAP1–216 also functions upstream by interacting with factors required for Op-IAP function. Suggesting that Op-IAP itself is the target of Op-IAP1–216 inhibition, immunoprecipitations demonstrated that Op-IAP1–216, but not BIR-less Op-IAP183–268, associated with full-length Op-IAP in vivo (Fig. 5). Moreover, substitution of conserved residues within Op-IAP1–216 BIR 2 caused loss of interaction with Op-IAP and a concomitant loss of dominant inhibition (Fig. 7). The BIRs were sufficient for self-association of full-length Op-IAP in vivo (Fig. 6). The interaction of Op-IAP with itself and with Op-IAP1–216 occurred in the presence and absence of known apoptotic stimuli (R. R. Hozak, unpublished data). Thus, it is likely that these interactions are not mediated by a proapoptotic factor but rather involve direct BIR-BIR association. This conclusion is consistent with independent two-hybrid data which indicated strong interaction between full-length Op-IAPs in yeast (Zoog and Friesen, unpublished data). Collectively, these data suggest that Op-IAP1–216 interacts directly with full-length Op-IAP, causing loss of function (Fig. 10). Furthermore, these findings imply that oligomerization is required for Op-IAP antiapoptotic activity.

Other mechanisms for inhibition by Op-IAP1–216 are not excluded. For example, Op-IAP1–216 may also interact with a cellular death factor that is the target of Op-IAP antiapoptotic activity and thereby compete with Op-IAP for binding. Op-IAP interacts with Drosophila Reaper, Hid, and Grim and inhibits apoptosis induced by their overproduction in SF21 cells (15, 45, 46). However, under optimal conditions, an Op-IAP truncation that contains only BIR 2 is sufficient to block apoptosis induced by any of these proteins (47). Therefore, because Op-IAP1–216 would also likely inhibit apoptosis induced by these proapoptotic factors, we find it unlikely that Op-IAP1–216 interferes with Op-IAP function by competing for interaction with the SF21 homologs of these death inducers.

Op-IAP1–216 interference with cell survival.

It has been hypothesized that endogenous IAPs contribute to the survival threshold of a cell (reviewed in references 3, 11, and 32). Our studies here indicated that Op-IAP1–216 reduced the survival threshold of SF21 cells. Transient or stable expression of Op-iap1–216 did not induce SF21 apoptosis (Fig. 8). However, Op-IAP1–216 caused a significant increase in apoptosis upon heat shock, which by itself is not sufficient to induce cell death. Thus, these cells were sensitized by Op-IAP1–216 to a stress that is normally nonlethal. UV-induced caspase activation and apoptotic death also occurred earlier in Op-IAP1–216-producing cells (Fig. 9), indicating that the barrier to radiation-induced apoptosis was lowered. These findings suggest that Op-IAP1–216 has the capacity to disable endogenous survival factors. The inactivation of Op-IAP by Op-IAP1–216 raises the possibility that this truncation also interacts with an endogenous S. frugiperda IAP, displacing it from its normal target and lowering the level of protective IAP. Indeed, S. frugiperda cells possess an endogenously expressed iap (J. C. Reed, personal communication). The affinity of Op-IAP1–216 for S. frugiperda IAPs remains to be determined.

Functionality of oligomeric IAPs.

Op-IAP's capacity to oligomerize and the dominant interference exhibited by Op-IAP1–216 suggest that oligomerization is required for IAP antiapoptotic activity. Not only are the BIRs required for oligomerization, but they are necessary for interaction with Drosophila Reaper, Hid, and Grim (15, 23, 45, 46). Since the most conserved amino acid residues among these three death inducers are the same residues required for both apoptosis induction and IAP interaction, these apoptotic effectors may target oligomeric IAP, causing dissociation and inactivation by a mechanism similar to that of Op-IAP1–216 (Fig. 10). As a consequence of the loss of IAP function, the cellular survival threshold is diminished, whereupon downstream effectors, caspases included, are activated (11, 32). This model is consistent with genetic evidence from Drosophila, which suggests that the function of these death proteins is to disable the anticaspase activity of cellular IAP (49). Baculoviruses overcome this problem by directing the synthesis of functional IAP, thereby rebuilding the survival threshold and prolonging host cell survival despite active apoptotic signaling by viral infection. Although the exact role of oligomerization in Op-IAP function is unknown, it may be required for proper interaction with downstream apoptotic effectors.

Potential BIR-mediated oligomerization of cellular IAPs.

Certain cellular IAPs, including Drosophila DIAP1, human XIAP, and human cIAPs, do not require their C-terminal RING motif to prevent apoptosis induced by specific stimuli (13, 18, 35, 39, 47). Thus, the RING motif may have different functions for different IAPs. In contrast, the BIR motif is absolutely required for IAP antiapoptotic activity (11, 25, 32). The high degree of sequence similarity among BIRs within the IAP family raises the possibility that other IAPs, including cellular IAPs, self-associate and that such oligomerization contributes to antiapoptotic activity. Although c-IAP1 or c-IAP2 oligomers have not been detected in vivo (34), c-IAP1 BIR 3 has the capacity to self-associate in vitro (21). If IAP oligomerization is not universal, it is possible that such interaction is more important for those IAPs containing one or two BIRs, such as Op-IAP. Intramolecular oligomerization may unite a required number of BIRs for appropriate interactions with targeted apoptotic effectors. To address such possibilities, it is necessary to distinguish the biochemical contributions of individual BIRs to IAP oligomerization and stable association with proapoptotic factors.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Q. Huang John Reed for sharing unpublished data, Steve Zoog for yeast two-hybrid analyses, Christine Schneider for Op-IAP plasmids, and Doug LaCount for helpful discussions. We also acknowledge the University of Wisconsin-Madison Medical School Vector Core Laboratory for the gift of DOTAP reagent.

This work was supported in part by Public Health Service grant AI40482 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (P.D.F.) and NIH Predoctoral Traineeship GM07215 (R.R.H.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Adida C, Berrebi D, Peuchmaur M, Reyes-Mugica M, Altieri D C. Anti-apoptotis gene, survivin, and prognosis of neuroblastoma. Lancet. 1998;351:882–883. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)70294-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ambrosini G, Adida C, Altieri D C. A novel anti-apoptosis gene, survivin, expressed in cancer and lymphoma. Nat Med. 1997;3:917–921. doi: 10.1038/nm0897-917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bergmann A, Agapite J, Steller H. Mechanisms and control of programmed cell death in invertebrates. Oncogene. 1998;17:3215–3223. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bertin J, Mendrysa S M, LaCount D J, Gaur S, Krebs J F, Armstrong R C, Tomaselli K J, Friesen P D. Apoptotic suppression by baculovirus P35 involves cleavage by and inhibition of a virus-induced CED-3/ICE-like protease. J Virol. 1996;70:6251–6259. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.9.6251-6259.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Birnbaum M J, Clem R J, Miller L K. An apoptosis-inhibiting gene from a nuclear polyhedrosis virus encoding a polypeptide with Cys/His sequence motifs. J Virol. 1994;68:2521–2528. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.4.2521-2528.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cartier J L, Hershberger P A, Friesen P D. Suppression of apoptosis in insect cells stably transfected with baculovirus p35: dominant interference by N-terminal sequences p351–76. J Virol. 1994;68:7728–7737. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.12.7728-7737.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clem R J, Fechheimer M, Miller L K. Prevention of apoptosis by a baculovirus gene during infection of insect cells. Science. 1991;254:1388–1390. doi: 10.1126/science.1962198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clem R J, Hardwick J M, Miller L K. Anti-apoptotic genes of baculoviruses. Cell Death Differ. 1996;3:9–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clem R J, Miller L K. Control of programmed cell death by the baculovirus genes p35 and iap. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:5212–5222. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.8.5212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crook N E, Clem R J, Miller L K. An apoptosis-inhibiting baculovirus gene with a zinc finger-like motif. J Virol. 1993;67:2168–2174. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.4.2168-2174.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deveraux Q L, Reed J C. IAP family proteins-suppressors of apoptosis. Genes Dev. 1999;13:239–252. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.3.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deveraux Q L, Roy N, Stennicke H R, Van Arsdale T, Zhou Q, Srinivasula S M, Alnemri E S, Salvesen G S, Reed J C. IAPs block apoptotic events induced by caspase-8 and cytochrome c by direct inhibition of distinct caspases. EMBO J. 1998;17:2215–2223. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.8.2215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deveraux Q L, Takahashi R, Salvesen G S, Reed J C. X-linked IAP is a direct inhibitor of cell-death proteases. Nature. 1997;388:300–304. doi: 10.1038/40901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Duckett C S, Nava V E, Gedrich R W, Clem R J, Van Dongen J L, Gilfillan M C, Shiels H, Hardwick J M, Thompson C B. A conserved family of cellular genes related to the baculovirus iap gene and encoding apoptosis inhibitors. EMBO J. 1996;15:2685–2694. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harvey A J, Bidwai A P, Miller L K. Doom, a product of the Drosophila mod(mdg4) gene, induces apoptosis and binds to baculovirus inhibitor-of-apoptosis proteins. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:2835–2843. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.5.2835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harvey A J, Soliman H, Kaiser W J, Miller L K. Anti- and pro-apoptotic activities of baculovirus and Drosophila IAPs in an insect cell line. Cell Death Differ. 1997;4:733–744. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hawkins C J, Uren A G, Hacker G, Medcalf R L, Vaux D L. Inhibition of interleukin 1-beta-converting enzyme-mediated apoptosis of mammalian cells by baculovirus IAP. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:13786–13790. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.24.13786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hay B A, Wassarman D A, Rubin G M. Drosophila homologs of baculovirus inhibitor of apoptosis proteins function to block cell death. Cell. 1995;83:1253–1262. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90150-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hershberger P A, Dickson J A, Friesen P D. Site-specific mutagenesis of the 35-kilodalton protein gene encoded by Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus: cell line-specific effects on virus replication. J Virol. 1992;66:5525–5533. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.9.5525-5533.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hershberger P A, LaCount D J, Friesen P D. The apoptotic suppressor P35 is required early during baculovirus replication and is targeted to the cytosol of infected cells. J Virol. 1994;68:3467–3477. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.6.3467-3477.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hinds M G, Norton R S, Vaux D L, Day C L. Solution structure of a baculoviral inhibitor of apoptosis (IAP) repeat. Nat Struct Biol. 1999;6:648–651. doi: 10.1038/10701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jarvis D L. Effects of baculovirus infection on IE1-mediated foreign gene expression in stably transformed insect cells. J Virol. 1993;67:2583–2591. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.5.2583-2591.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaiser W J, Vucic D, Miller L K. The Drosophila inhibitor of apoptosis D-IAP1 suppresses cell death induced by the caspase drICE. FEBS Lett. 1998;440:243–248. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)01465-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kawasaki H, Altieri D C, Lu C D, Toyoda M, Tenjo T, Tanigawa N. Inhibition of apoptosis by survivin predicts shorter survival rates in colorectal cancer. Cancer Res. 1998;58:5071–5074. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.LaCasse E C, Baird S, Korneluk R G, MacKenzie A E. The inhibitors of apoptosis (IAPs) and their emerging role in cancer. Oncogene. 1998;17:3247–3259. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.LaCount D J, Friesen P D. Role of early and late replication events in induction of apoptosis by baculoviruses. J Virol. 1997;71:1530–1537. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.2.1530-1537.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee H H, Miller L K. Isolation of genotypic variants of Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus. J Virol. 1978;27:754–767. doi: 10.1128/jvi.27.3.754-767.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liston P, Young S S, Mackenzie A E, Korneluk R G. Life and death decisions-the role of the IAPs in modulating programmed cell death. Apoptosis. 1997;2:423–441. doi: 10.1023/a:1026465926478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lu C D, Altieri D C, Tanigawa N. Expression of a novel antiapoptosis gene, survivin, correlated with tumor cell apoptosis and p53 accumulation in gastric carcinomas. Cancer Res. 1998;58:1808–1812. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Manji G A, Hozak R R, LaCount D J, Friesen P D. Baculovirus inhibitor of apoptosis functions at or upstream of the apoptotic suppressor P35 to prevent programmed cell death. J Virol. 1997;71:4509–4516. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.6.4509-4516.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McCarthy J V, Dixit V M. Apoptosis induced by Drosophila Reaper and Grim in a human system. Attenuation by Inhibitor of Apoptosis proteins (cIAPs) J Biol Chem. 1998;273:24009–24015. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.37.24009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miller L K. An exegesis of IAPs: salvation and surprises from BIR motifs. Trends Cell Biol. 1999;9:323–328. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(99)01609-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Miller L K, Kaiser W J, Seshagiri S. Baculovirus regulation of apoptosis. Semin Virol. 1998;8:445–452. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rothe M, Pan M G, Henzel W J, Ayres T M, Goeddel D V. The TNFR2-TRAF signaling complex contains two novel proteins related to baculoviral inhibitor of apoptosis proteins. Cell. 1995;83:1243–1252. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90149-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Roy N, Deveraux Q L, Takahashi R, Salvesen G S, Reed J C. The c-IAP-1 and c-IAP-2 proteins are direct inhibitors of specific caspases. EMBO J. 1997;16:6914–6925. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.23.6914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Roy N, Mahadevan M S, McLean M, Shutler G, Yaraghi Z, Farahani R, Baird S, Besner-Johnston A, Lefebvre C, Kang X, Salih M, Aubry H, Tamai K, Guan X, Ioannou P, Crawford T O, de Jong P J, Surh L, Ikeda J, Korneluk R G, MacKenzie A. The gene for neuronal apoptosis inhibitory protein is partially deleted in individuals with spinal muscular atrophy. Cell. 1995;80:167–178. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90461-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Seshagiri S, Miller L K. Baculovirus inhibitors of apoptosis (IAPs) block activation of Sf-caspase-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:13606–13611. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.25.13606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sun C, Cai M, Gunasekera A H, Meadows R P, Wang H, Zhang H, Wu W, Xu N, Ng S, Fesik S W. NMR structure and mutagenesis of the inhibitor-of-apoptosis protein XIAP. Nature. 1999;401:818–822. doi: 10.1038/44617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Takahashi R, Deveraux Q, Tamm I, Welsh K, Assa-Munt N, Salvesen G S, Reed J C. A single BIR domain of XIAP sufficient for inhibiting caspases. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:7787–7790. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.14.7787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tamm I, Wang Y, Sausville E, Scudiero D A, Vigna N, Oltersdorf T, Reed J C. IAP-family protein Survivin inhibits caspase activity and apoptosis induced by Fas (CD95), Bax, caspases, and anticancer drugs. Cancer Res. 1998;58:5315–5320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Uren A G, Coulson E J, Vaux D L. Conservation of baculovirus inhibitor of apoptosis repeat proteins (BIRPs) in viruses, nematodes, vertebrates and yeasts. Trends Biochem Sci. 1998;23:159–162. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(98)01198-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Uren A G, Pakusch M, Hawkins C J, Puls K L, Vaux D L. Cloning and expression of apoptosis inhibitory protein homologs that function to inhibit apoptosis and/or bind tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:4974–4978. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.10.4974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vaughn J L, Goodwin R H, Thompkins G L, McCawley P. Establishment of two insect cell lines from the insect Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera:Noctuidae) In Vitro. 1977;13:213–217. doi: 10.1007/BF02615077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vaux D L, Korsmeyer S J. Cell death in development. Cell. 1999;96:245–254. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80564-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vucic D, Kaiser W J, Harvey A J, Miller L K. Inhibition of reaper-induced apoptosis by interaction with inhibitor of apoptosis proteins (IAPs) Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:10183–10188. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.19.10183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vucic D, Kaiser W J, Miller L K. Inhibitor of apoptosis proteins physically interact with and block apoptosis induced by Drosophila proteins HID and GRIM. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:3300–3309. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.6.3300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vucic D, Kaiser W J, Miller L K. A mutational analysis of the baculovirus inhibitor of apoptosis Op-IAP. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:33915–33921. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.51.33915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vucic D, Seshagiri S, Miller L K. Characterization of reaper- and FADD-induced apoptosis in a lepidopteran cell line. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:667–676. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.2.667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang S L, Hawkins C J, Yoo S J, Muller H J, Hay B A. The Drosophila caspase inhibitor DIAP1 is essential for cell survival and is negatively regulated by HID. Cell. 1999;98:453–463. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81974-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yamaguchi K, Nagai S, Ninomiya-Tsuji J, Nishita M, Tamai K, Irie K, Ueno N, Nishida E, Shibuya H, Matsumoto K. XIAP, a cellular member of the inhibitor of apoptosis protein family, links the receptors to TAB1-TAK1 in the BMP signaling pathway. EMBO J. 1999;18:179–187. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.1.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]