Abstract

Background

Carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae (CP-KP) is becoming extensively disseminated in Iranian medical centers. Colistin is among the few agents that retains its activity against CP-KP. However, the administration of colistin for treatment of carbapenem-resistant infections has increased resistance against this antibiotic. Therefore, the identification of genetic background of co-carbapenem, colistin-resistance K. pneumoniae (Co-CCRKp) is urgent for implementation of serious infection control strategies.

Methods

Fourteen Co-CCRKp strains obtained from routine microbiological examinations were subjected to molecular analysis of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) using whole genome sequencing (WGS).

Results

Nine of 14 K. pneumoniae strains belonged to sequence type (ST)-11 and 50% of the isolates had K-locus type 15. All strains carried blaOXA-48 except for P26. blaNDM-1 was detected in only two plasmids associated with P6 and P26 strains belonging to incompatibility (Inc) groups; IncFIB, IncHI1B and IncFII. No blaKPC, blaVIM and blaIMP were identified. Multi-drug resistant (MDR) conjugative plasmids were identified in strains P6, P31, P35, P38 and P40. MICcolistin of K. pneumoniae strains ranged from 4 to 32 µg/ml. Modification of PmrA, PmrB, PhoQ, RamA and CrrB regulators as well as MgrB was identified as the mechanism of colistin resistance in our isolates. Single amino acid polymorphysims (SAPs) in PhoQ (D150G) and PmrB (R256G) were identified in all strains except for P35 and P38. CrrB was absent in P37 and modified in P7 (A200E). Insertion of ISKpn72 (P32), establishment of stop codon (Q30*) (P35 and P38), nucleotides deletion (P37), and amino acid substitution at position 28 were identified in MgrB (P33 and P42). None of the isolates were positive for plasmid-mediated colistin resistance (mcr) genes. P35 and P38 strains carried iutA, iucD, iucC, iucB and iucA genes and are considered as MDR-hypervirulent strains. P6, P7 and P43 had ICEKp4 variant and ICEKp3 was identified in 78% of the strains with specific carriage in ST11.

Conclusion

In our study, different genetic modifications in chromosomal coding regions of some regulator genes resulted in phenotypic resistance to colistin. However, the extra-chromosomal colistin resistance through mcr genes was not detected. Continuous genomic investigations need to be conducted to accurately depict the status of colistin resistance in clinical settings.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12941-021-00479-y.

Keywords: Colistin-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae, Carbapenemases producing strains, Hypervirulent plasmids

Introduction

Carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae (CP-KP) has been established as a major cause of healthcare-associated infection in many geographic areas, with high morbidity and mortality [1]. Infection with CP-KP is a serious clinical problem because it is difficult to treat using conventional antibiotics. Resistance to carbapenems can be mediated by various mechanisms including the production of carbapenemases, including K. pneumoniae carbapenemase (KPC), New Delhi metallo-β-lactamase (NDM), and oxacillinase-48 (OXA-48), production of extended spectrum β-lactamases (ESBL) plus porins and hyperproduction of Ambler class C (AmpC) β-lactamase [2]. Among major carbapenemases, OXA-48 carbapenemase is currently the one that is spreading the most rapidly in the Middle East and other countries worldwide [3–5]. Polymyxins especially colistin are among the few agents that retain its activity against CP-KP, and they are considered as the key components against severe infections caused by these superbugs. Increasing administration of colistin for treatment of CP-KP infections has contributed to the emergence of acquired resistance against this antibiotic [6]. Resistance to colistin is mostly associated with LPS modification (result from mutations in pmrA/pmrB, phoP/phoQ, mgrB, crrB, and ramA genes) as well as overproduction of efflux-pumps (mediated by kpnE/kpnF and mutations of acrB) on the chromosomal level. Additionally, the production of phosphor-ethanolamine transferase encoded by plasmid-mediated colistin resistance (mcr) genes results in transferable colistin-resistance [7]. In Iran, where the carbapenemase is becoming extensively disseminated among clinical Gram-negative isolates, increasing rate of colistin-resistant K. pneumoniae is a critical matter. Therefore, the identification of genetic background of co-carbapenem, colistin-resistance K. pneumoniae (Co-CCRKp) is urgent for implementation of serious infection control strategies.

Genomic studies based on whole genome sequencing (WGS) accurately identify multi-drug resistant (MDR) and hypervirulent clones in outbreaks and provide data about diversity and antimicrobial resistance (AMR) reservoir of K. pneumoniae [8]. Furthermore, such studies are capable to determine the circulation of clinically important sequence types (ST) and spreading of major AMR genes across various clonal lineages and among hospitalized patients and community carriers [9]. Therefore, the global and regional awareness of antibiotic resistance genetic determinants is critical to combat the spread of highly resistant K. pneumoniae and decrease the number of victims.

In this study, we conducted a comparative genomic analysis of 14 colistin-resistant OXA-48-producing K. pneumoniae isolated from different wards of two Iranian hospitals with focus on their AMR genetic reservoir using WGS.

Methods

Bacterial isolates

In the period between January 2014 to March 2016, one hundred and thirty-eight carbapenem-resistance K. pneumoniae isolates were obtained from routine microbiological examinations on clinical samples (e.g., urine and bronchial aspirate) from two medical centers in two provinces of Iran (hospital A, a 496-bed university hospital, located in Tehran and hospital B, a 800-bed university hospital, located in Isfahan.). Conventional biochemical examinations were used for identification of the isolates. Genus and specie of isolates were confirmed by PCR-sequencing of 16s rRNA [10].

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing

Antimicrobial susceptibility was determined using Kirby-Bauer disk diffusion method according to the clinical and laboratory standards institute (CLSI) guideline [11]. The minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) of carbapenems (imipenem, meropenem and ertapenem) were determined by gradient test strips (Liofilchem, Italy). Broth microdilution method was utilized to determine the MIC of colistin using colistin sulfate (Merck, Germany). According to CLSI M100- S30, a MIC = 2 µg/ml was interpreted as intermediate susceptibility, whereas a MIC of ≥ 4 µg/ml was considered as resistance [11]. E. coli ATCC 25922 was used as a control strain for antimicrobial susceptibility testing.

DNA extraction and whole genome sequencing

DNA extraction was performed using a bacterial genomic DNA kit (GenElute™, Sigma). Genome libraries were obtained from Illumina System (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA).

De novo assembly

The quality scores of the FASTQ paired-end files were checked using FastQC software [12]. Trimming and de novo assembly of short-read sequences was performed using Trimmomatic version 0.40 and SPAdes version 3.15.2, respectively [13] with k-mer = 99. The quality of contig assembly was assessed using QUAST software [14].

Post de novo assembly

Genomic statistics of contig assemblies including genome length, GC content, N50 and number of coding sequences (CDSs), rRNA and tRNA as well as gene annotation were determined using DFAST (https://dfast.ddbj.nig.ac.jp/). Chromosomal and extra-chromosomal contigs were sorted using mlplasmids—version 1.0.0 (https://sarredondo.shinyapps.io/mlplasmids/). Multi-locus sequence typing (MLST) of chromosomal contigs was determined using MLST Server 2.0 (https://cge.cbs.dtu.dk/services/MLST/). Plasmid incompatibility (Inc) was checked using PlasmidFinder 2.0 server (http://cge.cbs.dtu.dk/services/PlasmidFinder/). Antibiotic resistance genes were detected using the comprehensive antibiotic resistance database (CARD) (https://card.mcmaster.ca/analyze/rgi). Capsular typing (K-typing), O typing and allelic determination were performed using the Kaptive webtool (https://kaptive-web.erc.monash.edu/). Taxonomic and phylogenetic analysis was performed using Type Strain Genome Server (https://tygs.dsmz.de/). Modification of phylogenetic tree was performed using the iTOL webtool (https://itol.embl.de). The structures of interactive conjugative element of K. pneumoniae (ICEKp) were characterized using NCBI BLAST (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). Single amino acid polymorphisms (SAPs) of chromosomally-encoded proteins involved in AMR were identified using paired-wise alignment in NCBI P-BLAST.

Results

K. pneumoniae isolates and antimicrobial susceptibilities

Totally, 14 of 138 carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae isolates (10.1%) (P6, P7, P26, P31, P32, P33, P35, P36, P37, P38, P40, P41, P42, P43 and P44) showed colistin-resistant phenotype. All 14 strains were resistant to cefotaxime (CTX), ceftazidime (CAZ), cefepime (FEP), ciprofloxacin (CIP), ertapenem (ETP), meropenem (MEM) and imipenem (IMP). Strains were confirmed as colistin-resistant by broth microdilution method (according to 2020 CLSI M100- S30) with MICs ranged between 4 and 32 µg/ml. E-test results ranged from 0.5 to 8 µg/ml for ertapenem, 0.5 to 32 µg/ml for meropenem and 4 to 256 µg/ml for imipenem. Of 14 Co-CCRKp isolates, seven (50%) were isolated from intensive care unit (ICU), three from neurosurgery ward, two from emergency unit and two different isolates from a 55-year-old female outpatient. The strains were isolated from tracheal (7), urine (2), cerebrospinal fluid (2), blood (1), wound (1) and chest-tube (1). The clinical information of the strains is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Clinical information of 14 colistin-resistant OXA-48-producing K. pneumoniae strains

| Strain | Infection source | Hospital ward | Gender | Age | MIC Colistin |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P6 | Urine | Outpatient | Female | 55 | 16 |

| P7 | Wound | Outpatient | Female | 55 | 16 |

| P26 | Tracheal | ICU | Male | 43 | 4 |

| P31 | Tracheal | ICU | Female | 22 | 16 |

| P32 | Tracheal | ICU | Female | 65 | 16 |

| P33 | Tracheal | Neurosurgery | Female | 34 | 16 |

| P35 | Urine | ICU | Male | 77 | 16 |

| P36 | Chest tube | ICU | Male | 26 | 16 |

| P37 | Tracheal | ICU | Male | 37 | 16 |

| P38 | CSF | ICU | Female | 45 | 16 |

| P40 | Tracheal | Neurosurgery | Male | 38 | 32 |

| P42 | Tracheal | Neurosurgery | Female | 34 | 32 |

| P43 | CSF | Emergency | Male | 57 | 32 |

| P44 | Blood | Emergency | Female | 53 | 16 |

Chromosomal characterization

Genetic features

The DFAST genetic analysis of purified contigs showed that chromosome length of 14 K. pneumoniae strains scaled from minimum 4,941,238 bp (for P38) to maximum 5,349,088 bp (for P37). The number of CDSs varried from 4694 to 5118. The highest N50 was calculated 215,119 belonging to P38. The GC content percentage for all isolated was 57%. The number of rRNA and tRNA varied from three to six and 51 to 80, respectively. See Additional file 1: Table S1.

Multilocus sequence typing (MLST)

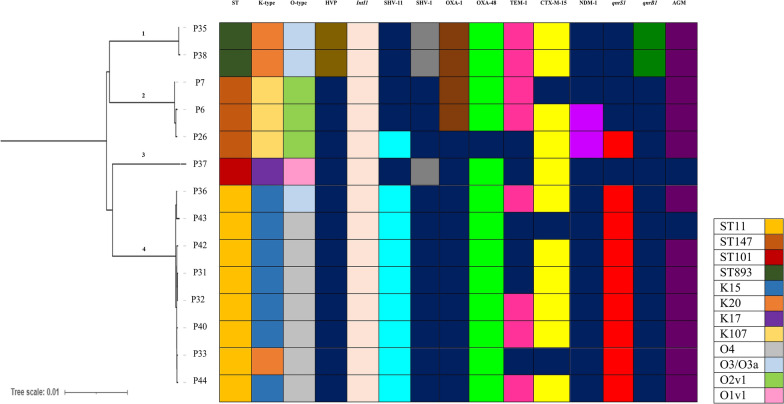

The MLST results showed that eight strains (57%) belonged to ST11 (P31, P32, P33, P36, P40, P42, P43 and P44), three strains belonged to ST147 (P6, P7 and P26), two strains belonged to ST893 (P35, P38) and one strains belonged to ST101 (P37). Figure 1. See Additional file 1: Table S1.

Fig. 1.

Phylogenetic tree and major genetic characteristics of 14 colistin-resistant OXA-48-producing K. pneumoniae strains including STs, serotypes, hypervirulence and major AMR genes. (HVP and AGM stand for hypervirulent plasmid and aminoglycoside modifying enzymes, respectively)

K-locus and O typing

The results of K-locus typing showed that P6, P7 and P26 had K107D1 (wzc 64 and wzi 64); P33, P35 and P38 had K20 (wzc 21 and wzi 150); P37 had K17 (wzc 18 and wzi 137) and the remained strains had K15 allelic profile (wzc 919 and wzi 50) (prevalence rate of 50%). Figure 1. In case of O-varient, P6, P7 and P26 belonged to O2v1 type; P35 and P38 belonged to O3/O3a; P37 belonged to O1v1 and P31, P32, P33, P36, P40, P42, P43 as well as P44 belonged to O4. See Fig. 1. See Additional file 1: Table S1.

AMR analysis

Resistance genes

The CARD results showed that our strains encoded AMR genes from different antibiotic classes including β-lactamases (blaSHV family and ampH), ATP-binding cassette (ABC) antibiotic efflux pumps (lptD and msbA), major facilitator superfamily (mfs, h-NS, emrR, tetB and tetR), antibiotic efflux pumps (kpnE, kpnG, kpnH and kpnG), resistance-nodulation-cell division (RND) antibiotic efflux pumps (oqxA and oqxB, marA, adeF, baeR, rsmA and crp), pmr phosphoethanolamine transferase (eptB and arnT), bacterial porins (OmpK37 and OmpA) and fosfomycin thiol transferase (fosA6 and fosA5). See Additional file 1: Table S1.

Single amino acid polymorphisms (SAPs)

Single amino acid substitutions of chromosomally-encoded proteins involved in AMR were detected by comparing related coding regions of each strains with K. pneumoniae NTUH-K2044 (NC_012731) as the reference colistin-susceptible strain using paired-wise alignment. SAPs resulted in resistance to cephalosporins; PBP3, elfamycin; EF-Tu, fosfomycin; UhpT, fluoroquinolones; ParC, GyrA and GyrB and multiple drugs; MarR were identified. Table 2. All 14 strains underwent identical modifications in PBP3 (D350N, S357N), UhpT (E350Q) and EF-Tu (R234F). S3N (in P6, P7 and P26) and E86K (in P32, P33, P36, P37, P40, P42, P43 and P44) were detected for MarR protein. MarR was found intact in strains P31, P35 and P38. See Table 2. S80I was detected for ParC in all strains except for P38 (P403A). GyrA was modified identically in all strains (S83I) except for P37 and P43 (D87G). GyrB was found intact in all strains except for P6, P7, P26 and P43 (E466D). Regarding colistin-resistance; mgrB was found intact in P6, P7, P26, P31, P36, P40, P43 and P44. However, P35 and P38 underwent a stop codon (Q30*) along MgrB protein sequence. Alteration of MgrB in P32 was mediated by insertion of ISKpn72. Moreover, P37 had a large deletion and frame shift in the mgrB coding region. Amino acid modification (C28W) of MgrB was detected in P33 and P42. SAP of PhoQ (D150G) was identified in all strains except for P35 and P38. No amino acid alteration was found related to PhoP and AcrB. Amino acid substitutions of PmrA were detected in P35 and P38 (A41T) and P37 (A218V). SAP in PmrB (R256G) was identified in all strains except for P35, P37 and P38. RamA underwent modifications in P6, P7, P26 (D71B) and P43 (I25T). See Table 2. Modification of CrrB was only detected in P7 (A200E). Interestingly, CrrB was absent in P37.

Table 2.

Single amino acid polymorphisms related to antimicrobial resistance in 14 colistin-resistant OXA-48-producing K. pneumoniae strains

| Protein | Strains | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cephalosporin resistance | Elfamycin resistance | Fosfomycin resistance | Repressor of multi-drug resistance operon | Fluoroquinolone resistance | Colistin resistance | ||||||||||

| PBP3 | EF-Tu | UhpT | MarR | ParC | GyrA | GyrB | PhoP | PhoQ | PmrA | PmrB | MgrB | RamA | AcrB | CrrB | |

| P6 | D350N, S357N | R234F | E350Q | S3N | S80I | S83I | E466D | Intact | D150G | Intact | R256G | Intact | D71B | Intact | Intact |

| P7 | D350N, S357N | R234F | E350Q | S3N | S80I | S83I | E466D | Intact | D150G | Intact | R256G | Intact | D71B | Intact | A200E |

| P26 | D350N, S357N | R234F | E350Q | S3N | S80I | S83I | E466D | Intact | D150G | Intact | R256G | Intact | D71B | Intact | Intact |

| P31 | D350N, S357N | R234F | E350Q | Intact | S80I | S83I | Intact | Intact | D150G | Intact | R256G | Intact | Intact | Intact | Intact |

| P32 | D350N, S357N | R234F | E350Q | E86K | S80I | S83I | Intact | Intact | D150G | Intact | R256G | Insertion of ISKpn72 | Intact | Intact | Intact |

| P33 | D350N, S357N | R234F | E350Q | E86K | S80I | S83I | Intact | Intact | D150G | Intact | R256G | C28W | Intact | Intact | Intact |

| P35 | D350N, S357N | R234F | E350Q | Intact | S80I | S83F | Intact | Intact | Intact | A41T | Intact | Stop codon (Q30*) | Intact | Intact | Intact |

| P36 | D350N, S357N | R234F | E350Q | E86K | S80I | S83I | Intact | Intact | D150G | Intact | R256G | Intact | Intact | Intact | Intact |

| P37 | D350N, S357N | R234F | E350Q | E86K | S80I | D87N | Intact | Intact | D150G | A218V | Intact | Deletion | Intact | Intact | ND |

| P38 | D350N, S357N | R234F | E350Q | Intact | P403A | S83F | Intact | Intact | Intact | A41T | Intact | Stop codon (Q30*) | Intact | Intact | Intact |

| P40 | D350N, S357N | R234F | E350Q | E86K | S80I | S83I | Intact | Intact | D150G | Intact | R256G | Intact | Intact | Intact | Intact |

| P42 | D350N, S357N | R234F | E350Q | E86K | S80I | S83I | Intact | Intact | D150G | Intact | R256G | C28W | Intact | Intact | Intact |

| P43 | D350N, S357N | R234F | E350Q | E86K | S80I | D87G | E466D | Intact | D150G | Intact | R256G | Intact | I25T | Intact | Intact |

| P44 | D350N, S357N | R234F | E350Q | E86K | S80I | S83I | Intact | Intact | D150G | Intact | R256G | Intact | intact | Intact | Intact |

ND means not detected

Phylogenetic analysis

The genome-based phylogenteic tree showed that our 14 Co-CCRKp starins are devided to four clades as follows: P35 and P38 = clade 1; P6,P7 and P26 = clade 2; P37 = clade 3 and P31, P32, P33, P36, P40, P42, P43 and P44 = clade 4. The dendrogram demonstrated that the phylogenetic categorization of the strains almost matched with their classification based on ST, K-type and O-type. See Fig. 1.

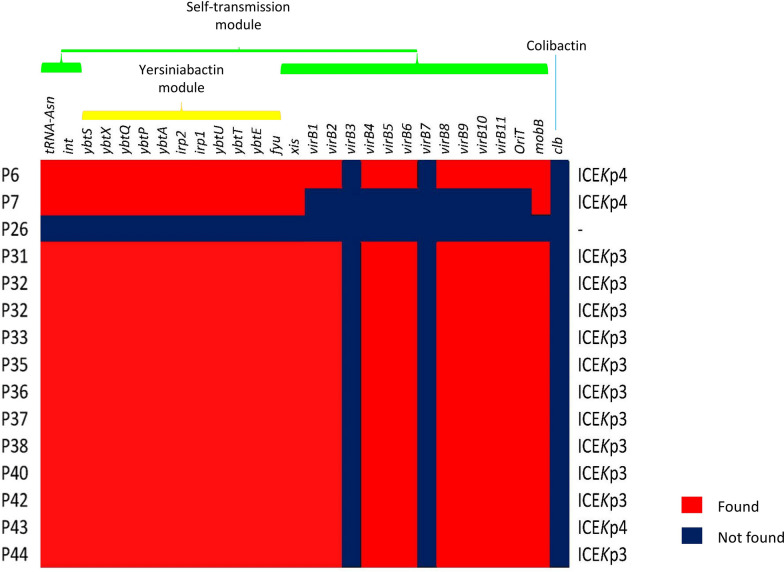

Integrative conjugative element (ICEKp)

Two distinct modules were identified in ICEKp structures of our strains: Yersiniabactin (ybtS, ybtX, ybtQ, ybtP, ybtA, irp2, irp1, ybtU, ybtT, ybtE and fyuA) and self-mobilization (int, xis, virB1, virB2, virB4, virB5, virB6, virB8, virB9, virB10, virB11 and mobB genes as well as oriT site). No colibactin was identified. ICEKp structures were detected in all 14 strains except for P23. P6, P7 and P43 carried ICEKp4 and the rest of the strains (78%) harbored ICEKp3. The virB3 and virB7 genes were absent in all ICEKp structures. The locus of virB was not identified in ICEKp of P7. See Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

The interactive conjugative element structures of 14 colistin-resistant OXA-48-producing K. pneumoniae strains. Two main modules including yersiniabactin (ybtS, ybtX, ybtQ, ybtP, ybtA, irp2, irp1, ybtU, ybtT, ybtE, and fyuA) and self-mobilization (int, xis, virB1, virB2, virB4, virB5, virB6, virB8, virB9, virB10, virB11, mobB genes and oriT site) were identified and no colibactin was detected. ICEKp3 was the prodominant ICEKp variant among 13 positive strains

Extra-chromosomal characterization

Genetic features

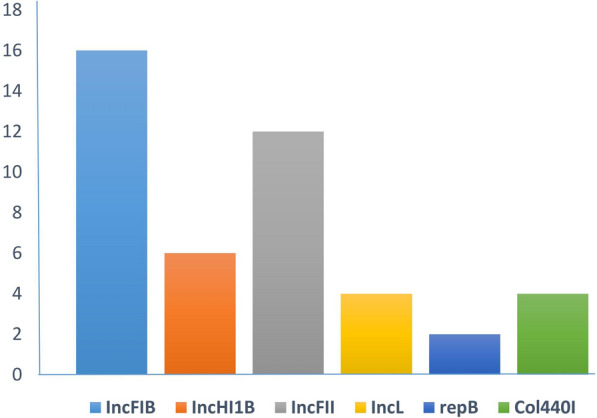

Thirty-five putative plasmids were assembled. Strains P6, P35, P37, P38, P40 and P44 carried three plasmids and P7, P26, P31, P32, P33, P36, P42 and P43 carried two plasmids. Plasmids incompatibility (Inc) groups were identified as IncFIB = 16, IncFII = 12, IncHI1B = 6, Col440I = 4, IncL = 4 and repB = 2. See Fig. 3. One/two plasmids in P6, P7, P35, P38, P40 and P44 strains were positive for all four compartment of relaxsasome complex including oriT, relaxsase, type IV secretion system (T4SS) and type IV coupling protein (T4CP). P31, P32, P36 and P42 carried one plasmid lacking only T4CP. Integron class 1 was detected in plasmids of all 14 K. pneumoniae strains. See Additional file 2: Table S2.

Fig. 3.

Compared frequencies of different plasmid incompatibility (Inc) types among 14 colistin-resistant OXA-48-producing K. pneumoniae strains. The results showed that the majority of plasmids belonged to IncFIB and IncFII

AMR and hypervirulence analysis

AMR genes related to multiple antibiotic drug classes were identified in majority (85%) of plasmids. ESBLs including blaOXA-48, blaOXA-1, blaCTX-M-15, blaTEM-1, and blaNDM-1 were identified. Figure 1. blaOXA-48 was detected in all Co-CCRKp isolates, with the exception of P26. Strains P6, P7, P35 and P38 encoded blaOXA-1. blaCTX-M-15 and blaTEM-1 were identified in 78% and 57% of the strains, respectively. The blaNDM-1 gene was found in only two plasmids related to strains P6 and P26 (both belonging to ST147). No blaKPC, blaVIM and blaIMP were identified. AMR genes related to aminoglycoside modifying enzymes including aph(3'')-Ib, aac(6')-Ib9, aph(6)-Id, aac(6')-Ib-cr6 aadA5, rmtC and rmtF were found in all strains except for P37 and P43. qnrS1 was detected in 71% of the strains. qnrB1 was identified only in plasmids related to P35 and P38. See Fig. 1. Other AMR genes were tetB, tetR, ermB, arr2, mphA, catB3 and dfrA14. No mcr was detected. Strains P35 and P38 carried iutA, iucD, iucC, iucB and iucA hypervirulence genes on their plasmids. See Additional file 2: Table S2.

The blaOXA-48 and blaNDM-1 genetic environment

The gene annotation of OXA-48-producing plasmids showed that blaOXA-48 was flanked upstream/downstream by the LysR family transcriptional factor (lysR) in almost all strains. Additional file 3: Figure S1A. In P31, blaOXA-48 was flanked downstream by insertion sequence (IS) element transposase and blaCTX-M-15. In P32, two blaOXA-48 genes were identified on two distinc regions which environmet for one of them was similar to P31. The latter was flanked upstream by IS6 family transposase. In P33, the lysR and blaOXA-48 complex was flanked downstream by three hypotetical genes and a transposase. The lysR and blaOXA-48 complex, dhps, aph(6)-Id and blaCTX-M-15 were surrounded by IS4 and a transposase element in P35. In P36, P37, P38 and P44, the lysR and blaOXA-48 complex was flanked upstream by IS91, IS4 and IS110 family transposase genes, respectively. No transposase element was found surrounding the lysR and blaOXA-48 complex in P6, P7, P40, P42 and P43. blaNDM-1 was flanked upsteram by bleomycin binding protein and trpF genes and downstream by IS91 family transposase in both P6 and P26. See Additional file 3: Figure S1B.

Discussion

Our understanding about the genetic background of K. pneumoniae has increased worldwide. However, few WGS-based studies have focused on clinical K. pneumoniae isolates in Iran and consequently; the detalied genomic knowledge of cirulating STs in clinical settings is still limited in our country. WGS data for 14 clinical Co-CCRKp strains isolated between 2014 and 2016 in Iran were analyzed to provide a comparative genetic background that will help us to upgarde our information regarding epidemiology of AMR determinants.

One of the most clinically important AMR genes in K. pneumoniae isolates is class D β-lactamase blaOXA-48 [15]. The blaOXA-48 gene has been carrying by various plasmids Inc types including IncL/M, IncN, and IncA/C [16]. However, the results of our plasmid replicon typing shows that blaOXA-48 is carried by various incompatibility groups including IncL, Col440I, IncFIB and mainly IncFII. The genetic analysis of blaOXA-48 environment in our strains indicates that the LysR family transcriptional factor gene is closely related to blaOXA-48 carriage in K. pneumoniae. Detection of blaOXA-48 in transferrable plasmids is a clinical emergency as it can rapidly be widespread among other strains and even other Enterobacterales mediating highly resistant outbreaks in healthcare settings. P6, P31, P35, P38 and P40 are considered clinically significant strains as they contain conjutaive plasmids carrying blaOXA-48 carbapenemase. This suggests that carbapenem-resistance soon will disseminate in ICU and other wards among Iranian medical settings. Also, the carriage of a conjugative OXA-48-producing plasmids in an outpatient is highly troublesome as it implies the higher prevalence rates of carbapenemase in the community in near future. In the presented study, we reported the first extra-chromosomal carriage of two blaOXA-48 in strain P32. The double carriage of blaOXA family by a single strain is rarely reported and is a matter of concern due to more rapid transmission of this significant carbapenemase. Sherchan and colleagues reported two copies of blaOXA-181 on ST147 K. pneumoniae from Nepal in 2020 which was previously reported from Pakistan, the United Arab Emirates and Korea [17].

P6 and P26 strains were detected as the only NDM-1 producing strains in our study indicating lower rate of blaNDM-1 carriage compared to other β-lactamase such as blaCTX-M-15 and blaTEM-1. However, higher prevalence of blaNDM-1 was reported form other Middle Eastern countries specifically Egypt and Saudi Arabia [18, 19]. In the study by Ghaith et al. [20] 52.2% of K. pneumoniae strains isolated from neonatal ICU in Cairo were NDM-1 producers. The prevalence of blaNDM-1 among Enterobacterales is mediated by rapid dissemination of conjugative plasmids [16]. In our study, none of the NDM-1 producing plasmids were conjugative. blaNDM–1 gene has been detected on plasmids of various incompatibility groups including IncF, IncA/C, IncL/M, IncH, IncN, and IncX3 or untypeable [16]. However, both of NDM-1 producing plasmids in our study belonged to IncFIB and IncHI1B. Co-carriage of blaNDM-1 and blaOXA-48 genes was seen in strain P6. Solgi et al. investigated the ESBLs carriage of 71 clinical carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales in an Iranian hospital in Tehran. In this study, among 62 bacterial isolates, 46% and 37% of the isolates harbored blaNDM-1 and blaOXA-48, respectively and co-carriage of blaNDM-1 and blaOXA-48 was detected in 16% of the isolates. Also, the plasmid incompatibility types IncFII and IncA/C were identified among the NDM-1 producing isolates, while only IncL/M was detected among OXA-48 producers [16]. Co-existence of the blaNDM-1 and blaOXA-48 genes among CR-KP isolates was previously reported from other Middle Eastern countries such as Egypt. In a recent study by El-Domany and colleagues [21], 50 isolates co-carrying blaNDM-1 and blaOXA-48 were reported among 230 K. pneumoniae clinical isolates. In this study, the rate of blaNDM-1 and blaOXA-48 was reported 70.0% and 52.0%, respectively. In our study, ST11, ST147, ST893 and ST101 were blaOXA-48 and blaNDM-1 carriers in agreement with previous reports of OXA-48 and NDM-1 producing K. pneumoniae from Iran [16, 22]. These consensus reports suggest successful circulation of mentioned STs in Iran. The clonal carriage of blaOXA-48 and blaNDM-1 among K. pneumoniae strains may be region-specific in a single geographical territory despite high burden of individual transits. Accordingly, a significant association was reported for ST199 and ST152 with blaOXA-48 and blaNDM-1 carriage form Saudi Arabia, respectively [23, 24].

Co-existance of blaOXA-48, blaCTX-M-15 and blaTEM-1 within one single plasmid was observed in P6, P31, P32, P35, P38 and P44. However, this complex production was also observed in separate plasmids of P7, P40 and P42. Production of OXA-48 in K. pneumoniae plasmids seems to be typically concurrent with other ESBLs mainly blaCTX-M and blaTEM. In one study, 88 of 94 of K. pneumoniae isolates in an Iranian hospital harbored blaSHV, blaCTX-M-15 and blaTEM-1 concurrently while only one and two isolates solely carried blaCTX-M-15 and blaSHV, respectively [15]. The transmission of major ESBLs among K. pneumoniae has been reported in conjugative IncL/M and IncFII plasmids with ability of interspecies transfer [23, 25]. Accordingly, in our extra-chromosomal analysis, IncFII was a major plasmid replicon type and IncL was detected in two conjugative ESBL producer plasmids.

Resistance to colistin has been increasingly reported in the world including the Middle East region. A high resistance rate of 16.9% was reported between 2015 and 2016 from Iran [26]. Totally, 524 colistin-resistant K. pneumoniae isolates were reported from Turkey and Iran between 2013 and 2018 [27]. Jafari et al. [28] reported an increase of colistin resistance up to 50% in carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae isolates.

In the presented study; amino acid substitution, premature termination, deletion and insertion of IS element were identified in the coding region of MgrB as well as PmrA/PmrB, PhoP/PhoQ, RamA and CrrB regulators. MgrB inactivation was identified in 42% of the strains including P32, P33, P35, P37, P38 and P42. Substitution of cysteine at position 28 of MgrB with tryptophan was detected in P33 and P42. Position 28 is considered as an important region for amino acid substitution due to the key role of disulfide bonds of cysteine residue in MgrB functionality [29]. Similar SAPs such as C28F, C28Y and C28S has been previously reported in several different studies [6, 30]. In addition, truncation of MgrB at position 30 (Q30*) was identified in P35 and P38. Position 30 is highly prone to be modified in long exposure to colistin and therefore; (Q30*) has been commonly reported in other studies [29]. Insertional inactivation of MgrB was identified in only one strain (P32) mediating by insertion of ISKpn72 element (belonging to IS4 family) in coding region of MgrB. Zhang et al. recently demonstrated the phenotypic switch of colistin-susceptible K. pneumoniae strains to colistin-resistant ones by horizontal transfer of an ISKpn72 carrying-plasmid. Therefore, in spite of chromosomal origin of MgrB; its modification can be plasmid-mediated and depended on conjugation processes. However, this phenomenon is not probable in our study because both plasmids of P32 were non-conjugative [31]. In this study, crrB gene was not carried by the P37 chromosome. The absence of crrB was previously reported in the study by Jayol et al.[32] which may be due to the differences in the lateral acquisition of the crrAB operon in K. pneumoniae. Thomas et al. [33] claimed that the lack of CrrB leads to significantly higher MICcolistin and bacterial virulence than MgrB disruption in CR-KP. However, it seems that such manifestation cannot be attributed to P37. SAPs in PhoQ and PmrB were detected in 85% and 78% of the strains, respectively. PhoQ and PmrB modifications have been frequently reported in colistin-resistant K. pneumoniae isolates. In the study by Haeili et al. [26] 95% of 20 K. pneumoniae strains underwent point mutations in PmrB of which R256G was detected in five strains. However, the amino acid substitution in PhoQ or PmrB does not always correspond colistin-resistance [30, 34, 35]. Zhu et al. [36] reported mutated PhoQ in seven colistin-susceptible isolates of K. pneumoniae. The authors also suggested that the exposure of the isolates to colistin during treatment resulted in new PhoQ alterations mediating resistance to colistin. It is evident that upregulation of pmrHFIJKLM, pmrCAB, as well as pmrK operons is associated with colistin resistance in K. pneumoniae [37, 38]. Therefore, the mechanism of colistin resistance needs to be carefully interpreted.

The prevalence of hypervirulence among MDR K. pneumoniae is increasing worldwide [39]. In a meta-analysis conducted by Sanikhani et al. [40] the rate of reported hypervirulent K. pneumoniae isolates was determined 21.7% globally which majority of them were from China. In our study, P35 and P38 carried non-conjugative hypervirulence plasmids belonging to repB plasmid replicon type and considered as MDR-hypervirulent strains. This may suggest that P35 and P38 possess hypervirulent background which acquired MDR plasmids through conjugative processes. The rate of hypervirulence was 14% in our study and both strains were positive for iutA, iucD, iucC, iucB and iucA. Few studies have reported hypervirulent K. pneumoniae in Iran. Pajand et al. investigated the presence of hypervirulence genes in K. pneumoniae clinical isolates. peg344, iucA, rmpA, rmpA2, iroB1, iroB2 and iutA were detected among all carbapenem-resistant isolates with 1.8%, 1.8%, 1.8%, 1.8%, 7.3%, 12.7% and 18.2% rate of carriage, respectively. The results of their study indicated that the prevalence of iutA was even higher in NDM-1 producing isolates [41]. Taraghian et al. detected 11 MDR-hypervirulent strains among 105 urinary tract K. pneumoniae isolates. In their study, ESBLs were identified in all hypervirulent strains and their carriage by hypervirulent stains were significantly higher compared to the classical ones [42]. In addition, Sanikhani et al. [43] reported the prevalence rate of 21.38% among 477 K. pneumoniae clinical isolates with high percentage of MDR and high-level resistance to imipenem.

The ICEKp analysis highlighted that the majority of our strains (78%) carried ICEKp3. According to an investigation by Lam et al. among 2498 K. pneumoniae genomes belonging to 37 different STs; ICEKp4, ICEKp3, ICEKp10 and ICEKp5 were the most common types of ICEKp. The results of this study also revealed that ICEKp variants can be integrated more frequently in specific STs compared to the other ones. The authors showed that almost 40% of the ICEKp positive K. pneumoniae strains belonged to CC258 [44]. Similarly, another study from South America indicated that the rate of ICEKp carriage is higher in strains belonging to ST11 and ST340. In our study, almost all ST11 strains harbored ICEKp3. This specific carriage of ICEKp3 in K. pneumoniae ST11 was previously reported by a Turkish study in 2019 [45].

Conclusion

In this study, we assembled the whole-genomes of 14 colistin-resistant OXA-48-producing K. pneumoniae referred to two Iranian hospitals as well as their plasmids. The prevalence of blaOXA-48 in our strains was very high as well as blaSHV, blaCTX-M-15 and blaTEM-1. MDR conjugative plasmids as well as hypervirulent plasmids were detected in some strains. Amino acid substitution, premature termination, deletion and insertion of an IS element were identified in the coding region of MgrB. SAPs in PmrA, PmrB, PhoQ, RamA and CrrB regulators were involved in colistin resistance. Pan-genomic investigations can provide data on AMR reservoir of highly-resistant K. pneumoniae at clinical and even community levels and ultimately provide a realistic status of AMR countrywide.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Table S1. Genotypic, resistome profile and capsular and O-typing of 14 colistin-resistant OXA-48-producing K. pneumoniae strains.

Additional file 2: Table S2. Extrachromosomal Genetic and resistome information of 14 colistin-resistant OXA-48-producing K. pneumoniae strains.

Additional file 3: Figure S1. A) The genetic environment of blaOXA-48 and blaNDM-1 in 14 colistin-resistant OXA-48-producing K. pneumoniae strains. blaOXA-48 was identified in all strains except for P26. The lysR and blaOXA-48 complex was found in all strains. No transposase element was detected surrounding the lysR and blaOXA-48 complex in P6, P7, P40, P42 and P43. Two blaOXA-48 with different genetic arrangement were found on P32 plasmid. In P36, P37, P38 and P44; the lysR and blaOXA-48 complex was flanked upstream by IS91, IS4 and IS110 family transposase genes, respectively. B) blaNDM-1 was detected only in P6 and P26. blaNDM-1 was flanked upsteram by bleomycin binding protein and trpF genes and downstream by the IS91 family transposase.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the personnel in the bacteriology department of Pasteur Institute of Iran for their help. This research was supported by Pasteur Institute of Iran.

Abbreviations

- AMR

Antimicrobial resistance

- WGS

Whole genome sequencing

- MDR

Multi-drug resistant

- SAPs

Single amino acid polymorphysims

- mcr

Plasmid-mediated colistin resistance

- Co-CCRKp

Co-carbapenem colistin-resistant K. pneumoniae

- CP-KP

Carbapenemase-producing K. pneumoniae

- KPC

K. pneumoniae carbapenemase

- CLSI

Clinical and laboratory standards institute

- MIC

Minimal inhibitory concentration

- CDSs

Coding sequences

- CARD

Comprehensive antibiotic resistance database

- ICEKp

Interactive conjugative element of K. pneumoniae

- ABC

ATP-binding cassette

- RND

Resistance-nodulation-cell division

- NDM

New Delhi metallo-β-lactamase

- ESBL

Extended spectrum β-lactamases

- AmpC

Ambler class C T4SS: type IV secretion system

- T4CP

Type IV coupling protein

- ICU

Intensive care unit

- IS

Insertion sequence

- Inc

Incompatibility

Authors’ contributions

FB, HS, FS and NB designed the study and drafted the manuscript. FB, HS, CGG, SN, NNG and NB performed the experimental work and analyzed the data. FB read and approved the final manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant or funding.

Availability of data and materials

All generated data and materials are included in the text. This Whole Genome Shotgun project has been deposited at DDBJ/ENA/GenBank under the BioProject accession number PRJNA749021. The genomes described in this paper are version JAHYXE000000000, JAHYXD000000000, JAHYXC000000000, JAHYXB000000000, JAHYXA000000000, JAHYWZ000000000, JAHYWY000000000, JAHYWX000000000, JAHYWW000000000, JAHYWV000000000, JAHYXF000000000, JAHYWU000000000, JAHYWT000000000 and JAHYWS000000000.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This project was conducted based on the ethical guidelines previously approved by the Pasteur Institute of Iran (project number: IR.PII. REC 0.1395.51).

Consent for publication

Authors have read the manuscript and consented for publication of all presented information.

Competing interests

Authors declare that they had no commercial, personal and political conflicting of interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Hamid Solgi, Email: hamid.solgi@gmail.com.

Farzad Badmasti, Email: fbadmasti2008@gmail.com, Email: f_badmasti@pasteur.ac.ir.

References

- 1.Spyridopoulou K, Psichogiou M, Sypsa V, Miriagou V, Karapanou A, Hadjihannas L, Tzouvelekis L, Daikos GL. Containing Carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae in an endemic setting. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2020;9(1):102. doi: 10.1186/s13756-020-00766-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Codjoe FS, Donkor ES. Carbapenem resistance: a review. Med Sci (Basel, Switzerland) 2017;6(1):1. doi: 10.3390/medsci6010001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Han R, Shi Q, Wu S, Yin D, Peng M, Dong D, Zheng Y, Guo Y, Zhang R, Hu F. Dissemination of carbapenemases (KPC, NDM, OXA-48, IMP, and VIM) among carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae isolated from adult and children patients in China. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2020;10:314. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2020.00314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mairi A, Pantel A, Sotto A, Lavigne JP, Touati A. OXA-48-like carbapenemases producing Enterobacteriaceae in different niches. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2018;37(4):587–604. doi: 10.1007/s10096-017-3112-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pitout JDD, Peirano G, Kock MM, Strydom K-A, Matsumura Y. The global ascendency of OXA-48-type carbapenemases. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2019;33(1):e00102-19. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00102-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Palmieri M, D’Andrea MM, Pelegrin AC, Mirande C, Brkic S, Cirkovic I, Goossens H, Rossolini GM, van Belkum A. Genomic epidemiology of carbapenem- and colistin-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates from serbia: predominance of ST101 strains carrying a novel OXA-48 plasmid. Front Microbiol. 2020;11:294. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.00294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aghapour Z, Gholizadeh P, Ganbarov K, Bialvaei AZ, Mahmood SS, Tanomand A, Yousefi M, Asgharzadeh M, Yousefi B, Kafil HS. Molecular mechanisms related to colistin resistance in Enterobacteriaceae. Infect Drug Resist. 2019;12:965–975. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S199844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bowers JR, Kitchel B, Driebe EM, MacCannell DR, Roe C, Lemmer D, de Man T, Rasheed JK, Engelthaler DM, Keim P, et al. Genomic analysis of the emergence and rapid global dissemination of the clonal group 258 Klebsiella pneumoniae pandemic. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(7):e0133727. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0133727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Musicha P, Msefula CL, Mather AE, Chaguza C, Cain AK, Peno C, Kallonen T, Khonga M, Denis B, Gray KJ, et al. Genomic analysis of Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates from Malawi reveals acquisition of multiple ESBL determinants across diverse lineages. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2019;74(5):1223–1232. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkz032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Juretschko S, Loy A, Lehner A, Wagner M. The microbial community composition of a nitrifying-denitrifying activated sludge from an industrial sewage treatment plant analyzed by the full-cycle rRNA approach. Syst Appl Microbiol. 2002;25(1):84–99. doi: 10.1078/0723-2020-00093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.CLSI. Performance standards for antimicrobial suseptibility testing. In: Edited by Institute CLS, 30th edn; 2020.

- 12.Brown J, Pirrung M, McCue LA. FQC Dashboard: integrates FastQC results into a web-based, interactive, and extensible FASTQ quality control tool. Bioinform. 2017;33(19):3137–3139. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btx373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bankevich A, Nurk S, Antipov D, Gurevich AA, Dvorkin M, Kulikov AS, Lesin VM, Nikolenko SI, Pham S, Prjibelski AD. SPAdes: a new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. J Comput Biol. 2012;19(5):455–477. doi: 10.1089/cmb.2012.0021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gurevich A, Saveliev V, Vyahhi N, Tesler G. QUAST: quality assessment tool for genome assemblies. Bioinform. 2013;29(8):1072–1075. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Solgi H, Badmasti F, Giske CG, Aghamohammad S, Shahcheraghi F. Molecular epidemiology of NDM-1-and OXA-48-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae in an Iranian hospital: clonal dissemination of ST11 and ST893. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2018;73(6):1517–1524. doi: 10.1093/jac/dky081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Solgi H, Nematzadeh S, Giske CG, Badmasti F, Westerlund F, Lin YL, Goyal G, Nikbin VS, Nemati AH, Shahcheraghi F. Molecular epidemiology of OXA-48 and NDM-1 producing Enterobacterales species at a University Hospital in Tehran, Iran, Between 2015 and 2016. Front Microbiol. 2020;11:936. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.00936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sherchan JB, Tada T, Shrestha S, Uchida H, Hishinuma T, Morioka S, Shahi RK, Bhandari S, Twi RT, Kirikae T, et al. Emergence of clinical isolates of highly carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae co-harboring blaNDM-5 and blaOXA-181 or -232 in Nepal. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;92:247–252. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khalil MA, Elgaml A, El-Mowafy M. Emergence of multidrug-resistant New Delhi metallo-β-lactamase-1-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae in Egypt. Microb Drug Resist. 2017;23(4):480–487. doi: 10.1089/mdr.2016.0003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Touati A, Mairi A. Epidemiology of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacterales in the Middle East: a systematic review. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2020;18(3):241–250. doi: 10.1080/14787210.2020.1729126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ghaith DM, Zafer MM, Said HM, Elanwary S, Elsaban S, Al-Agamy MH, Bohol MFF, Bendary MM, Al-Qahtani A, Al-Ahdal MN. Genetic diversity of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella Pneumoniae causing neonatal sepsis in intensive care unit, Cairo, Egypt. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2020;39(3):583–591. doi: 10.1007/s10096-019-03761-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.El-Domany RA, El-Banna T, Sonbol F, Abu-Sayedahmed SH. Co-existence of NDM-1 and OXA-48 genes in carbapenem resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae clinical isolates in Kafrelsheikh, Egypt. Afr Health Sci. 2021;21(2):489–496. doi: 10.4314/ahs.v21i2.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Solgi H, Shahcheraghi F, Bolourchi N, Ahmadi A. Molecular characterization of carbapenem-resistant serotype K1 hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae ST11 harbouring blaNDM-1 and blaOXA-48 carbapenemases in Iran. Microb Pathog. 2020;149:104507. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2020.104507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zaman TU, Alrodayyan M, Albladi M, Aldrees M, Siddique MI, Aljohani S, Balkhy HH. Clonal diversity and genetic profiling of antibiotic resistance among multidrug/carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates from a tertiary care hospital in Saudi Arabia. BMC Infect Dis. 2018;18(1):205. doi: 10.1186/s12879-018-3114-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sonnevend Á, Ghazawi AA, Hashmey R, Jamal W, Rotimi VO, Shibl AM, Al-Jardani A, Al-Abri SS, Tariq WU, Weber S. Characterization of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae with high rate of autochthonous transmission in the Arabian Peninsula. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(6):e0131372. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0131372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Torres-González P, Bobadilla-Del Valle M, Tovar-Calderón E, Leal-Vega F, Hernández-Cruz A, Martínez-Gamboa A, Niembro-Ortega MD, Sifuentes-Osornio J, Ponce-de-León A. Outbreak caused by Enterobacteriaceae harboring NDM-1 metallo-β-lactamase carried in an IncFII plasmid in a tertiary care hospital in Mexico City. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015;59(11):7080–7083. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00055-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Haeili M, Javani A, Moradi J, Jafari Z, Feizabadi MM, Babaei E. MgrB alterations mediate colistin resistance in Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates from Iran. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:2470. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.02470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aris P, Robatjazi S, Nikkhahi F, Amin Marashi SM. Molecular mechanisms and prevalence of colistin resistance of Klebsiella pneumoniae in the Middle East region: a review over the last 5 years. J Glob Antimicrob Resist. 2020;22:625–630. doi: 10.1016/j.jgar.2020.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jafari Z, Harati AA, Haeili M, Kardan-Yamchi J, Jafari S, Jabalameli F, Meysamie A, Abdollahi A, Feizabadi MM. Molecular epidemiology and drug resistance pattern of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates from Iran. Microb Drug Resist. 2019;25(3):336–343. doi: 10.1089/mdr.2017.0404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kong Y, Li C, Chen H, Zheng W, Sun Q, Xie X, Zhang J, Ruan Z. In vivo emergence of colistin resistance in carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae mediated by premature termination of the mgrB Gene regulator. Front Microbiol. 2021;12:656610. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.656610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cheng Y-H, Lin T-L, Pan Y-J, Wang Y-P, Lin Y-T, Wang J-T. Colistin resistance mechanisms in Klebsiella pneumoniae strains from Taiwan. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015;59(5):2909–2913. doi: 10.1128/AAC.04763-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang B, Yu B, Zhou W, Wang Y, Sun Z, Wu X, Chen S, Ni M, Hu Y. Mobile plasmid mediated transition from colistin-sensitive to resistant phenotype in Klebsiella pneumoniae. Front Microbiol. 2021;12:619369. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.619369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jayol A, Nordmann P, Brink A, Villegas M-V, Dubois V, Poirel L. High-level resistance to colistin mediated by various mutations in the crrB gene among carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2017;61(11):e01423–e11417. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01423-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McConville TH, Annavajhala MK, Giddins MJ, Macesic N, Herrera CM, Rozenberg FD, Bhushan GL, Ahn D, Mancia F, Trent MS. CrrB positively regulates high-level polymyxin resistance and virulence in Klebsiella pneumoniae. Cell rep. 2020;33(4):108313. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.108313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aires CAM, Pereira PS, Asensi MD, Carvalho-Assef APDA. mgrB mutations mediating polymyxin B resistance in Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates from rectal surveillance swabs in Brazil. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2016;60(11):6969–6972. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01456-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Choi M, Ko KS. Identification of genetic alterations associated with acquired colistin resistance in Klebsiella pneumoniae isogenic strains by whole-genome sequencing. Antibiot. 2020;9(7):374. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics9070374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhu Y, Galani I, Karaiskos I, Lu J, Aye SM, Huang J, Yu HH, Velkov T, Giamarellou H, Li J. Multifaceted mechanisms of colistin resistance revealed by genomic analysis of multidrug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates from individual patients before and after colistin treatment. Int J Infect Control. 2019;79(4):312–321. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2019.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cannatelli A, Giani T, D'Andrea MM, Di Pilato V, Arena F, Conte V, Tryfinopoulou K, Vatopoulos A, Rossolini GM. MgrB inactivation is a common mechanism of colistin resistance in KPC-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae of clinical origin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58(10):5696–5703. doi: 10.1128/AAC.03110-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Poirel L, Jayol A, Bontron S, Villegas M-V, Ozdamar M, Türkoglu S, Nordmann P. The mgrB gene as a key target for acquired resistance to colistin in Klebsiella pneumoniae. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2014;70(1):75–80. doi: 10.1093/jac/dku323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mataseje LF, Boyd DA, Mulvey MR, Longtin Y. Two hypervirulent isolates producing a KPC-2 carbapenemase from a Canadian patient. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2019;63(7):e00517–00519. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00517-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sanikhani R, Moeinirad M, Shahcheraghi F, Lari A, Fereshteh S, Sepehr A, Salimi A, Badmasti F. Molecular epidemiology of hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Iran J Microbiol. 2021;13(3):257–265. doi: 10.18502/ijm.v13i3.6384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pajand O, Darabi N, Arab M, Ghorbani R, Bameri Z, Ebrahimi A, Hojabri Z. The emergence of the hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae (hvKp) strains among circulating clonal complex 147 (CC147) harbouring blaNDM/OXA-48 carbapenemases in a tertiary care center of Iran. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. 2020;19(1):12. doi: 10.1186/s12941-020-00349-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Taraghian A, Nasr Esfahani B, Moghim S, Fazeli H. Characterization of hypervirulent extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae among urinary tract infections: the first report from Iran. Infect Drug Resist. 2020;13:3103–3111. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S264440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sanikhani R, Moeinirad M, Solgi H, Haddadi A, Shahcheraghi F, Badmasti F. The face of hypervirulent Klebsiella Pneumoniae (hvKp) isolated from clinical samples of two Iranian teaching hospitals. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. 2021;20:58. doi: 10.1186/s12941-021-00467-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lam MMC, Wick RR, Wyres KL, Gorrie CL, Judd LM, Jenney AWJ, Brisse S, Holt KE. Genetic diversity, mobilisation and spread of the yersiniabactin-encoding mobile element ICEKp in Klebsiella pneumoniae populations. Microb Genom. 2018;4(9):e000196. doi: 10.1099/mgen.0.000196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Octavia S, Kalisvar M, Venkatachalam I, Ng OT, Xu W, Sridatta PSR, Ong YF, Wang LD, Chua A, Cheng B, et al. Klebsiella pneumoniae and Klebsiella quasipneumoniae define the population structure of blaKPC-2 Klebsiella: a 5 year retrospective genomic study in Singapore. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2019;74(11):3205–3210. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkz332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Table S1. Genotypic, resistome profile and capsular and O-typing of 14 colistin-resistant OXA-48-producing K. pneumoniae strains.

Additional file 2: Table S2. Extrachromosomal Genetic and resistome information of 14 colistin-resistant OXA-48-producing K. pneumoniae strains.

Additional file 3: Figure S1. A) The genetic environment of blaOXA-48 and blaNDM-1 in 14 colistin-resistant OXA-48-producing K. pneumoniae strains. blaOXA-48 was identified in all strains except for P26. The lysR and blaOXA-48 complex was found in all strains. No transposase element was detected surrounding the lysR and blaOXA-48 complex in P6, P7, P40, P42 and P43. Two blaOXA-48 with different genetic arrangement were found on P32 plasmid. In P36, P37, P38 and P44; the lysR and blaOXA-48 complex was flanked upstream by IS91, IS4 and IS110 family transposase genes, respectively. B) blaNDM-1 was detected only in P6 and P26. blaNDM-1 was flanked upsteram by bleomycin binding protein and trpF genes and downstream by the IS91 family transposase.

Data Availability Statement

All generated data and materials are included in the text. This Whole Genome Shotgun project has been deposited at DDBJ/ENA/GenBank under the BioProject accession number PRJNA749021. The genomes described in this paper are version JAHYXE000000000, JAHYXD000000000, JAHYXC000000000, JAHYXB000000000, JAHYXA000000000, JAHYWZ000000000, JAHYWY000000000, JAHYWX000000000, JAHYWW000000000, JAHYWV000000000, JAHYXF000000000, JAHYWU000000000, JAHYWT000000000 and JAHYWS000000000.