Abstract

Researchers and patients conducted an environmental scan of policy documents and public-facing websites and abstracted data to describe COVID-19 adult inpatient visitor restrictions at 70 academic medical centers. We identified variations in how centers described and operationalized visitor policies. Then, we used the nominal group technique process to identify patient-centered information gaps in visitor policies and provide key recommendations for improvement. Recommendations were categorized into the following domains: 1) provision of comprehensive, consistent, and clear information; 2) accessible information for patients with limited English proficiency and health literacy; 3) COVID-19 related considerations; and 4) care team member methods of communication.

Keywords: COVID-19, quality improvement, patient perspectives/narratives, communication

Introduction

Hospital visitor restriction policies in response to the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic have received widespread attention because of their adverse impact on patient- and family-centered care (1–4). Describing and comparing how hospitals have implemented COVID-19 visitor policies presents an opportunity to reduce inconsistencies and promote equitable care (5).

The aims of this study are to 1) conduct an environmental scan of policy documents and websites describing COVID-19 adult inpatient visitor restrictions at 70 academic medical centers and 2) partner with patients and caregivers to use these data to identify gaps and generate recommendations for improvement of these policies and resources.

Patient Stakeholder Engagement

The Hospital Medicine Reengineering Network (HOMERuN) Patient and Family Advisory Council (PFAC) has met monthly since 2018 and comprises a group of 11 patient and caregiver advocates. Each member has experienced hospitalization and represents different medical centers and geographic areas across the United States (6). All HOMERuN PFAC members are collaborators and part of the study team.

Methods

We conducted an environmental scan of internal policy documents and public-facing websites describing visitor restrictions in response to COVID-19 between August and October 2020. Environmental scanning in health care is an established, effective, and widely used approach for gathering and synthesizing information that identifies gaps and opportunities and enables understanding of a specific topic (7). Data from environmental scanning efforts can be used proactively by organizations to inform policy and impact operations (7).

The study took place within a 70-site North American Hospital Medicine research collaborative—HOMERuN (8,9). We invited collaborative participants to submit protocols on COVID-19 visitor restrictions from their hospitals. In addition, we identified public-facing websites of centers that described adult inpatient visitor restriction policies.

We created a data abstraction tool to ensure consistency in data collection, which contained closed and open-ended items asking: number of visitors allowed, categories of restriction exceptions, details of how rules are operationalized, end-of-life policies, rules for visitors, accommodations for visitors (e.g., parking), and care team-to-family communication practices. Data was managed in Qualtrics (Provo, UT). We used descriptive statistics to summarize quantitative data and at least two reviewers independently abstracted and interpretated open-ended items to ensure accuracy (10).

Following data synthesis, all 11 PFAC members of the study team met to identify gaps in policies and create a set of patient-centered COVID-19 hospital visitor recommendations. This was achieved using the nominal group technique (NGT) process—an established and structured methodology for consensus-building (11,12). The NGT process was facilitated by JDH and RW during two 1-hour virtual consensus-building sessions. Prior to the first session, PFAC members were asked to review the results of the data abstraction and website review. Then during the first session, they were asked to discuss any gaps that they perceived and/or any concerns with information contained within the policy documents and/or websites. Standard NGT practices were followed including the opportunity for all PFAC members to share their views, allowing adequate time for discussion, enabling members to comprehend each other's point of view, and ensuring that no perspectives were excluded (11,12). The session was digitally recorded and transcribed. Transcripts summarizing the first session were sent to PFAC members for review before a second consensus-building session. During the second session, again through facilitated discussion and consensus-building, PFAC members were asked to identify the most salient gaps and topics from those discussed in the first session—these gaps and topics informed a set of patient-centered recommendations for COVID-19 hospital visitor policies.

Results

Seventy public-facing websites and 18 local protocols were reviewed (Appendix 1). Twelve (17%) centers did not allow any visitors, 51 (73%) centers allowed one visitor, and 7 (10%) centers did not describe the actual number of visitors that were allowed (Table 1). For hospitalized patients with COVID-19, 44 (63%) centers outlined visitor policies that were different than those for patients without COVID-19. Exceptions to general visitor restriction policies varied by area of the hospital or department. The majority of hospitals required masks for visitors (n = 49, 70%), with 14 (20%) specifying that masks would be provided by the facility if visitors did not have their own. The majority of hospitals did not provide information regarding visitor accommodations.

Table 1.

Summary of n = 70 Sites and COVID-19 Visitor Policies.

| Number of visitors allowed | |

| 0 | 12 (17) |

| 1 | 51 (73) |

| Not described | 7 (10) |

| Exceptions to visitor restrictions by hospital area or patient population* | |

| Admission | 0 |

| Behavioral health issues | 9 (13) |

| Disability | 34 (49) |

| Discharge | 8 (11) |

| Emergency Department | 39 (56) |

| End-of-Life | 43 (61) |

| Infusion Center | 10 (14) |

| Limited English Proficiency patients | 3 (4) |

| Maternity/Labor and Delivery/Obstetrics | 52 (74) |

| Neonatal ICU | 28 (40) |

| Pediatric | 59 (84) |

| Surgery and Procedures | 36 (51) |

| Contact information for patients and caregiver with visitor policy questions? | |

| Yes | 13 (19) |

| Visitor screening elements * | |

| Check for COVID-19 symptoms | 40 (57) |

| Fever screening / temperature check | 20 (29) |

| Masks required | 49 (70) |

| Negative COVID-19 test | 1 (1) |

| ≥18 years old only | 22 (31) |

| Restrictions and accommodations for hospital visitors* | |

| On-site food options | 21 (30) |

| Bathrooms open | 4 (6) |

| Bathrooms restricted | 1 (1) |

| Cafeteria open | 7 (10) |

| Cafeteria restricted | 9 (13) |

| Chapel open | 1 (1) |

| Food not allowed | 5 (7) |

| General restriction for public meeting places / hallways | 7 (10) |

| Gift shop open | 2 (3) |

| Gift shop restricted | 4 (6) |

| Recommendation to stay in patient's room | 34 (49) |

| End-of life visitor exceptions | |

| Stated policy exception exist and details provided | 31 (44) |

| Stated policy exception exist but no details provided | 12 (17) |

| Not described or provided | 27 (39) |

| Number of visitors allowed at end of life | |

| ≤2 | 5 (7) |

| 2 | 19 (27) |

| ≥2 | 5 (7) |

| “exceptions for family” | 3 (4) |

| Definition of end-of-life provided | |

| Yes | 12 (17) |

*sites can provide multiple responses meaning denominator is 70 for each category.

Forty-three (61%) centers noted they would allow end-of-life exceptions, with 32 providing details of the number of visitors allowed at end of life (Table 1). Twelve (17%) centers provided a definition for end-of-life time period, however these definitions varied across centers.

Thirty-one (44%) centers provided information about alternate visitation and communication strategies. Twenty-three (33%) centers described virtual platforms or gave detailed instructions of how to communicate with inpatients. Six (9%) centers specified that hospital resources, including iPads, would be provided if otherwise unavailable to a patient. Five (7%) institutions specified expectations for how inpatient teams would be communicating with advocates/family.

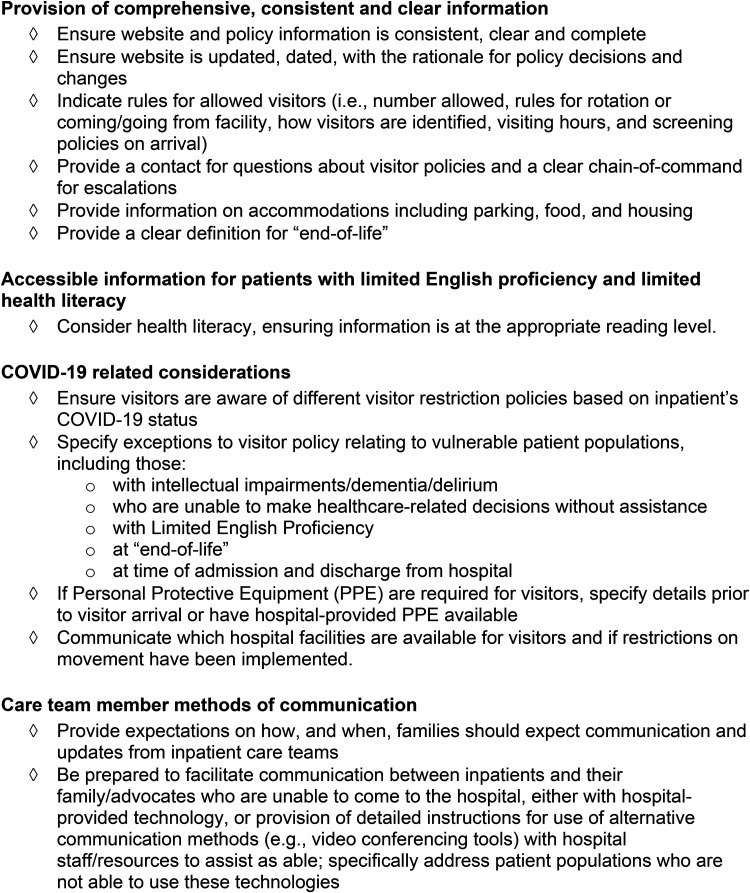

The NGT process identified patient-centered information gaps in visitor policies and provided several key recommendations (Figure 1). These recommendations have been categorized into the following domains: 1) provision of comprehensive, consistent, and clear information; 2) accessible information for patients with limited English proficiency and limited health literacy; 3) COVID-19 related considerations; and 4) care team member methods of communication.

Figure 1.

Nominal group technique findings: patient-and-family centered recommendations for developing, implementing and communicating inpatient COVID-19 visitor policies.

Discussion

Medical center descriptions of COVID-19 visitor policies were highly variable. For patients and caregivers, information overall—and particularly on public-facing websites—were found to be unclear, inconsistent and lacked details most important to them. Our national study provides a broader view consistent with single-site research and guidelines suggesting that centers use clear and consistent publicly available information (5,13–15). We found the lack of attention to health literacy and accessibility for patients with limited English proficiency to be particularly concerning. While these issues have been reported previously (16–19), the COVID-19 pandemic has amplified these problems at a time when the public requires accessible information. Few hospitals provided details of alternative communication options or expectations of how inpatient teams would communicate with families during a time period when visitor restrictions were firmly in place. Patient and family members on our study team expressed concerns that the insufficient consideration of both topics had the potential to reverse gains in patient- and family-centered care that have evolved over the last decade (20).

Given the rapid changes that had to be made in the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, it is understandable that hospitals had to implement visitor policies quickly. However, now that the pandemic continues to evolve, there are opportunities to learn from this last year to enhance patient- and family-centered policies using the recommendations reported in this study. Several recommendations are tailored to COVID-19 itself, but some also relate to how centers can communicate with patients and families who are isolated for other infection control purposes, providing lessons of lasting importance. Other recommendations such as updating websites to ensure information is complete and consideration of health literacy are critical lessons learned during the pandemic and are cross-cutting issues for the future.

Limitations

Our study included academic medical centers, meaning findings may not accurately reflect community hospital settings. The cross-sectional study design means our findings are a snapshot and may not reflect current visitor policies that have since been adjusted based on local needs and surges in COVID-19 infections. We only included local protocols and websites as data sources, meaning we did not include visitor policy information communicated by other methods such as print media, signs, and telephone. We also did not grade websites for health literacy using validated health literacy measures, rather we relied on the lived experiences and opinions of patient and caregiver advocates.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all HOMERuN COVID-19 collaborative members who provided their local COVID-19 visitor policy documents.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article:

James Harrison is supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality under Award Number K12HS026383 and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the NIH under Award Number KL2TR001870. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. Andrew Auerbach and Tiffany Lee report that research reported in this publication was supported by the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation.

ORCID iD: James D Harrison https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7761-7039

Ethical Approval: Ethical approval is not applicable to this article.

Statement of human and animal rights: This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects.

Statement of informed consent: There are no human subjects in this article and informed consent is not applicable.

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1.Coulter A, Richards T. Care during covid-19 must be humane and person centred. Br Med J. 2020;370. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m3483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hart JL, Turnbull AE, Oppenheim IM, Courtright KR. Family-Centered care during the COVID-19 Era. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2020;60(2):e93-7. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.04.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Siddiqi H. To suffer alone: hospital visitation policies during COVID-19. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(11):694-5. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Feder S, Smith D, Griffin H, Shreve ST, Kinder D, Kutney-Lee A, et al. “Why couldn’t I Go in To See Him?” bereaved Families’ perceptions of End-of-life communication during COVID-19. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2021;69(3):587–592. 10.1111/jgs.16993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weiner HS, Firn JI, Hogikyan ND, Jagsi R, Laventhal N, Marks A, et al. Hospital visitation policies during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. Am J Infect Control. 2021;49(4):516–520. 10.1016/j.ajic.2020.09.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hospital Medicine Reeginnering Network (HOMERuN). HOMERun patient & family advisory council (PFAC). Published 2020. Accessed May 22, 2021. https://hospitalinnovate.org/about-homerun/patient-family-advisory-council/

- 7.Charlton P, Doucet S, Azar R, Nagel DA, Boulos L, Luke A, et al. The use of the environmental scan in health services delivery research: a scoping review protocol. BMJ Open. 2019;9(9):e029805. 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-029805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hospital Medicine Reeginnering Network (HOMERUN). Hospital medicine reeginnering network (HOMERUN). Accessed May 21, 2021. http://hospitalinnovate.org

- 9.Auerbach AD, Patel MS, Metlay J, Schnipper JL, Williams MV, Robinson EJ, et al. The hospital medicine reengineering network (HOMERuN): a learning organization focused on improving hospital care. Acad Med. 2014;89(3):415-20. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schreirer M. Qualitative Content Analysis in Practice. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 11.McMillan SS, King M, Tully MP. How to use the nominal group and delphi techniques. Int J Clin Pharm. 2016;38(3):655-62. doi: 10.1007/s11096-016-0257-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Centers for Disease Control & Prevention. Evaluation Briefs: gaining consensus Among stakeholders through the nominal group technique. 2018. Accessed May 21, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/evaluation/pdf/brief7.pdf

- 13.Valley TS, Schutz A, Nagle MT, Miles LJ, Lipman K, Ketcham SW, et al. Changes to visitation policies and communication practices in michigan ICUs during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;202(6):883-5. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202005-1706LE [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu Y-A, Hsu Y-C, Lin M-H, Chang H-T, Chen T-J, Chou LF, et al. Hospital visiting policies in the time of coronavirus disease 2019: a nationwide website survey in Taiwan. J Chin Med Assoc. 2020;83(6):566-70. doi: 10.1097/JCMA.0000000000000326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kitano T, Piché-Renaud P-P, Groves HE, Streitenberger L, Freeman R, Science M. Visitor restriction policy on pediatric wards during novel coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak: a survey study across North America. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2020;31(9):766-8. doi: 10.1093/jpids/piaa126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rooney MK, Santiago G, Perni S, Horowitz DP, McCall AR, Einstein AJ, et al. Readability of patient education materials from high-impact medical journals: a 20-year analysis. J Patient Exp. 2021;8:1–9. 10.1177/2374373521998847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meppelink CS, van Weert JCM, Brosius A, Smit EG. Dutch Health websites and their ability to inform people with low health literacy. Patient Educ Couns. 2017;100(11):2012-9. 10.1016/j.pec.2017.06.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Taira BR, Kim K, Mody N. Hospital and health system-level interventions to improve care for limited English proficiency patients: a systematic review. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2019;45(6):446-58. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjq.2019.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Berdahl TA, Kirby JB. Patient-Provider communication disparities by limited English proficiency (LEP): trends from the US medical expenditure panel survey, 2006–2015. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(8):1434-40. doi: 10.1007/s11606-018-4757-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clay AM, Parsh B. Patient- and family-centered care: it’s Not just for pediatrics anymore. AMA J Ethics. 2016;18(1):40-4. doi: 10.1001/journalofethics.2016.18.1.medu3-1601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]