Abstract

Background:

The risk for all addictive drug and non-drug behaviors, especially, in the unmyelinated Prefrontal Cortex (PFC) of adolescents, is important and complex. Many animal and human studies show the epigenetic impact on the developing brain in adolescents, compared to adults. Some reveal an underlying hyperdopaminergia that seems to set our youth up for risky behaviors by inducing high quanta pre-synaptic dopamine release at reward site neurons. In addition, altered reward gene expression in adolescents caused epigenetically by social defeat, like bullying, can continue into adulthood. In contrast, there is also evidence that epigenetic events can elicit adolescent hypodopaminergia. This complexity suggests that neuroscience cannot make a definitive claim that all adolescents carry a hyperdopaminergia trait.

Objective:

The primary issue involves the question of whether there exists a mixed hypo or hyper–dopaminergia in this population.

Method:

Genetic Addiction Risk Score (GARS®) testing was carried out of 24 Caucasians of ages 12–19, derived from families with RDS.

Results:

We have found that adolescents from this cohort, derived from RDS parents, displayed a high risk for any addictive behavior (a hypodopaminergia), especially, drug-seeking (95%) and alcohol-seeking (64%).

Conclusion:

The adolescents in our study, although more work is required, show a hypodopaminergic trait, derived from a family with Reward Deficiency Syndrome (RDS). Certainly, in future studies, we will analyze GARS in non-RDS Caucasians between the ages of 12–19. The suggestion is first to identify risk alleles with the GARS test and, then, use well-researched precision, pro-dopamine neutraceutical regulation. This “two-hit” approach might prevent tragic fatalities among adolescents, in the face of the American opioid/psychostimulant epidemic.

Keywords: Adolescents, meso-limbic system, prefrontal cortex, hypodopaminergia, hyperdopaminergia, Precision Addiction Management (PAM), Genetic Addiction Risk Score (GARS)

1. INTRODUCTION

The role of dopamine in the brain is complicated [Mesolimbic Dopamine and the Regulation of Motivated Behavior. A review of the literature reveals inconsistent results in terms of explaining dopamine’s role in reward processing as well as other complicated behavioral, neurogenetic effects. While we are learning more about the role of neurogenetics in psychiatry and neurology [Polygenic Risk Scores in Psychiatry], there are more unanswered questions than illuminating findings. Despite this state of affairs, the neuropsychiatric community continues to generate an enormous amount of research, especially in the field of psychiatric genetics (PubMed listed 24,174 papers as of 8–18-20). As early as 1974, scientists attempted to find genetic links between psychiatric issues and substance use disorders via family-based genetic, inheritable characteristics versus a search for specific genes. In 1990, Merikangas and Gelertner discussed, without specific genetic evidence, the possible genetic links between alcoholism and depression [1]. Eight months earlier, however, Blum et al. [2], had provided the first confirmed finding of an association between the dopamine D2 receptor gene (DRD2) Taq A1 allele and severe alcoholism [2]. This finding was followed up by reports, which showed that carriers of the DRD2 A1 had a significantly reduced number of D2 receptors (by as much as 30–40%), compared to DRD2 A2 allele carriers [3].

1.1. Reward Deficiency Syndrome (RDS) Concept and Study Controls

An enormous amount of research work has been performed since 1990, some without carefully controlling for Reward Deficiency Syndrome (RDS) behaviors. RDS brings together a list of behaviors known to have the hypodopaminergic trait. The SAGE Encyclopedia of Abnormal and Clinical Psychology includes a description of RDS [4] first identified by Blum et al., in 1995 [5]. To reiterate, RDS is a neurogenetic and psychological theory first noted in 1996 [5]. It is characterized by reward-seeking behavior and/or addictions stemming from genetic variations, most notably resulting from those carrying the D2A1 allele. We now know that there are many gene polymorphisms involved, primarily inducing hypodopaminergia as identified in many early studies [ Genetic Addiction Risk Score (GARS): molecular neurogenetic evidence for predisposition to Reward Deficiency Syndrome (RDS)].In one published study by Fried et al., [ Hypodopaminergia and “Precision Behavioral Management” (PBM): It is a Generational Family Affair] through polymorphic genetic testing, it was shown that in a three-generation case series, each family member carried a hypodopaminergic compromised DNA allelic association. Another five generational study by Blum et al., [Generational association studies of dopaminergic genes in reward deficiency syndrome (RDS) subjects: selecting appropriate phenotypes for reward dependence behavior] showed a nonspecific RDS phenotype throughout the family. In essence, utilization of a nonspecific “reward” phenotype, rather than any subset (e.g. alcoholism) may be a paradigm shift in future association and linkage studies involving dopaminergic polymorphisms and other neurotransmitter gene candidates. It has been clearly shown that family members carrying a combination of these hypodopaminergic polymorphic genes in the brain reward circuitry may have a Bayesian Predictive value of 74.4% [see The D2 dopamine receptor gene as a predictor of compulsive disease: Bayes’ theorem]

1.1.1. Screening for RDS-free Controls

It should be noted that mixing diseased controls with experimental subjects can lead to spurious results [6]. In an earlier report, Blum’s group compared 122 obese/overweight (O/OW) Caucasian subjects with 30 Caucasian, non-obese controls, screened to exclude all RDS behaviors in the proband and family. The DRD2 Taq1 A1 allele was present in 67% of the O/OW subjects, compared to only 3.3% of super controls versus unscreened literature controls 29.4% (p≤ 0.001). Indeed, “Super Controls” identified by using a computer-programmed algorithm, which controlled (eliminated probands) for all known RDS behaviors, found a significant reduction of DRD2 A1 allelic prevalence (see Fig. 1) [7]. Further explanation of the importance of super controls will be presented in the “limitation and Issue” section below.

Fig. (1).

Illustrates the importance of screening for RDS free controls and DRD2 A1 allele [7] with permission.

1.2. The Epidemic

An overwhelming, tragic statistic is that by 2015, approximately two million people had a prescription opioid-use disorder and 591,000 were suffering from a heroin-use disorder. Prescription drug misuse cost the nation $78.5 billion in healthcare, law enforcement, and lost productivity. The death toll from opioid overdose reached over 47,600 people in 2017, with young and old dying prematurely [8]. Notably, the abuse of alcohol, stimulants, and cannabis is still on the rise in America. The National Institute of Health (NIH) and, specifically, the National Institute of Drug Abuse (NIDA), and the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) as well as lawmakers and representatives from health care, law enforcement, and many private stakeholders, have become committed to ending this crisis.

1.3. The Genetic Addiction Risk Score (GARS)

The Genetic Addiction Risk Score (GARS), developed by Blum’s group, can help to identify children, adolescents, or adults at-risk for the future development of addictions [9]. The ability to identify at-risk children and follow them prospectively throughout their teenage years could have significant public health implications, while, at the same time, expanding our understanding of the core biology of addiction. Extant addiction research has demonstrated that the key to effective treatment is early identification and treatment of drug use. Like heart disease, cancer, and other chronic illnesses with the potential for fatalities, the longer they go untreated, the more difficult they are to treat. The ability to identify at-risk individuals would be a step forward in the attempt to alter the negative impact of addiction on individual and population health. An epidemic of this magnitude requires bold, innovative interventions/screenings, educational awareness campaigns as well as high-quality scientific information and the secure monitoring of sensitive DNA data. Certainly, RDS, if untreated, can be a fatal disorder, which, therefore, requires early identification through genetic testing.

Research into the neurobiology and neurogenetics of reward deficiency behaviors, including substance and behavioral addictions, has led to the development of the patented GARS test. In unpublished work, a comparison of GARS with the Addiction Severity Index Media Version (ASI-MV), used in many clinical settings, found that GARS predicted the severity of both alcohol and drug dependency. In support of early testing for addiction and other RDS subtypes, early identification, therefore, seems most prudent.

To our knowledge, concerning USA and European awarded patents, GARS is the only panel of genes with established polymorphisms reflecting the Brain Reward Cascade (BRC), which has been correlated with the ASI-MV alcohol and drug risk severity score. While other studies are required to confirm and extend the GARS test to include other genes and polymorphisms that associate with a hypodopaminergic trait, these results provide clinicians with a noninvasive genetic test that can identify hypodopaminergia.

As discussed in our earlier publications [10, 11], genomic testing, such as GARS, can improve clinical interactions and decision-making. Precise knowledge of polymorphic associations can help assuage guilt and denial, corroborate family gene-o-grams, and assist in risk-severity-based decisions about appropriate therapies. The GARS result can inform choices regarding the selection of pain medications and risk for addiction. Also, decisions about placement, the appropriate level of care (inpatient, outpatient, intensive outpatient, residential, and determination of the length of stay in treatment, based on severity-relapse and recovery liability and vulnerability- these all can be informed by GARS. Pharmacogenetic medical monitoring provides for better clinical outcomes: for example, the A1 allele of the DRD2 gene reduces the binding to opioid delta receptors in the brain, thus, reducing naltrexone’s clinical effectiveness and, if present, would support “medical necessity” for insurance scrutiny.

The hypothesis under study is that in adolescents, there is a complex trait and state difference, whereby, despite a potential, genetically-induced dopaminergic deficit antecedent trait, especially, in children of Substance Use Disorder parents, there is a known, developmental, epigenetic impact induction of a dopaminergic surfeit state.

2. METHODS AND MATERIALS

Research into the neurogenetic basis of addiction identified and characterized by Reward Deficiency Syndrome (RDS) includes all drug and non-drug addictive, obsessive and compulsive behaviors. We are proposing herein that a new model for the prevention and treatment of Substance Use Disorder (SUD) a subset of RDS behaviors, based on objective biologic evidence, should be given serious consideration in the face of a drug epidemic. The development of the Genetic Addiction Risk Score (GARS) followed seminal research in 1990, whereby Blum’s group identified the first genetic association with severe alcoholism published in JAMA [2]. While it is true that no one to date has provided adequate RDS free controls there have been many studies using case-controls whereby SUD has been eliminated.

Our group continues to argue that this deficiency needs to be addressed in the field and if adopted appropriately, many spurious results would be eliminated, reducing confusion regarding the role of genetics in addiction. However, an estimation, based on these previous literature results provided herein, while not representative of all association studies known to date, this sampling of case-control studies displays significant associations between alcohol and drug risk. In fact, our argument is supported by a total of 110,241 cases and 122,525 controls derived from the current literature. The overwhelming evidence derived from all of these published studies strongly suggest that, while we may take argument concerning many of these so-called controls (e.g., blood donors), it is quite remarkable that there is a plethora of case-control studies indicating the selective association of these risk alleles (measured in GARS) for the most part indicating a hypodopaminergia. For completion, albeit published earlier, this paper presents the detailed methodology of the GARS. While it is true that no one to date has provided adequate RDS-free controls there have been many studies using case –controls whereby SUD has been eliminated. We argue that this deficiency needs to be addressed in the field and if adopted appropriately, many spurious results would be eliminated and as such it will reduce confusion providing a clearer understanding and an overhaul of the current state of the art of genetics underlining all addictive behaviors drug and non-drug or RDS.

Data collection procedures, instrumentation, and the analytical approach used to obtain GARS and subsequent research objectives are described. Can we combat SUD through early genetic risk screening in the addiction field, enabling early intervention by the induction of dopamine homeostasis? It is thought that GARS type of screening will provide a novel opportunity to help identify causal pathways and associated mechanisms of genetic factors, psychological characteristics, and addictions awaiting additional scientific evidence, including a future meta-analysis of all available data –a work in progress.

The GARS test is a direct-to-consumer (DTC), non-diagnostic, DNA genetic testing kit. The GARS genetic test determines genetic risk for RDS behaviors quantitatively by enumerating the number of single nucleotide polymorphisms (polymorphic risk alleles) detected. The GARS testing was approved by the University of Vermont School of Medicine IRB committee. Since the GARS test is available commercially, there was an exempt statement also executed by the IRB committee of Path Foundation, NY.

As part of the data collected by the Geneus Health Genomic Collection Center research initiative, the following data represents a small sample of 22 Caucasian subjects, age range from 12 to 19 years, from a direct to consumer cohort. The subjects were from families with RDS, although the actual drug and alcohol history is unknown for those who were tested with the GARS panel.

Specifically, the genetic panel was selected for polymorphisms of a number of reward genes that have been correlated with chronic dopamine deficiency and drug-related reward-seeking behavior (see Table 1). In Table 1 we display the current polymorphic risk alleles of the GARS panel.

Table 1.

Represents the GARS SNPS and VNTRs (snapshot).

| Gene | Polymorphism | Location | Risk Allele(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dopamine D1 Receptor DRD1 | rs4532 SNP | Chr 5 | A |

| Dopamine D2 Receptor DRD2 | rs1800497 SNP | Chr 11 | A |

| Dopamine D3 Receptor DRD3 | rs6280 SNP | Chr 3 | C |

| Dopamine D4 Receptor DRD4 | rs1800955 SNP | Chr 11 | C |

| 48 bases Repeat VNTR | Chr 11, Exon 3 | 7R,8R,9R,10R,11R | |

| Catechol-O-Methyltransferase COMT | rs4680 SNP | Chr 22 | G |

| Mu-Opioid Receptor OPRM1 | rs1799971 SNP | Chr 6 | G |

| Dopamine Active Transporter DAT1 | 40 bases Repeat VNTR | Chr 5, Exon 15 | 3R, 4R, 5R, 6R, 7R, 8R |

| Monoamine Oxidase A MAOA | 30 bases Repeat VNTR | Chr X, Promoter | 3.5R, 4R |

| Serotonin Transporter SLC6A4 (5HTTLPR) | 43 bases Repeat INDEL/VNTR plus rs25531 SNP | Chr 17 | LG, S |

| GABA(A) Receptor, Alpha-3 GABRB3 | CA-Repeat DNR | Chr15 (downstream) | 181 |

Abbreviations: Single Nucleotide Polymorphism [SNP]; Variable Number Tadem Repeat

2.1. Population GARS Prevalence

PubMed provides frequency data of major and minor alleles, but not population prevalence. SNPedia provides population diversity percentages for homozygous SNP; homozygous normal; and heterozygous for all but one of our SNPs, in the following populations (rs4532; rs1800497; rs6280; rs1800955; rs4680 and rs1799971) expressed in Table 2a and our cohort expressed in Table 2b. [see Table 2a,b]. Unfortunately, currently, there is no population prevalence data on variable number tandem repeats or dinucleotide repeats (see Tables 3–5).

Table 2A.

Global Heterozygous Prevalence.

| SNP | Global Heterozygous Prevalence |

|---|---|

| rs4532 | 32% |

| rs1800497 | 46% |

| rs6280 | 41% |

| rs1800955 | Frequency of C allele= .42 Prevalence not available |

| rs4680 | 42% |

| rs1799971 | 29% |

Table 2B.

Current Cohort demographics.

| Population | All | Male | Female |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number (n) | 22 | 15 (68%) | 7 (32%) |

| Average Age (n=22) | 13.5 | 14.4 | 11.5 |

Table 3A.

Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs).

| Gene | Polymorphism | Variant Alleles | Risk Allele |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dopamine D1 Receptor DRD1 | rs4532 | A/G | A |

| Dopamine D2 Receptor DRD2 | rs1800497 | A/G (A1/A2) | A (A1) |

| Dopamine D3 Receptor DRD3 | rs6280 | C/T | C |

| Dopamine D4 Receptor DRD4 | rs1800955 | C/T | C |

| Catechol-O-Methyltransferase COMT | rs4680 | A/G (Met/Val) | G (Val) |

| Mu-Opioid Receptor OPRM1 | rs1799971 | A/G (Asn/Asp) | G (Asp) |

Table 5.

GARS Repeats Primer Details.

| Primer | Sequence (5’ to 3’) | 5’ Label | Reaction (nM) |

|---|---|---|---|

| AMELO-F AMELO-R |

CCC TGG GCT CTG TAA AGA ATA GTG ATC AGA GCT TAA ACT GGG AAG CTG |

NED - |

150 |

| MAO-F MAO-R |

ACA GCC TGA CCG TGG AGA AG GAA CGG ACG CTC CAT TCG GA |

NED - |

120 |

| DAT-F DAT-R |

TGT GGT GTA GGG AAC GGC CTG AG CTT CCT GGA GGT CAC GGC TCA AGG |

6FAM - |

120 |

| DRD4-F DRD4-R |

GCT CAT GCT GCT GCT CTA CTG GGC CTG CGG GTC TGC GGT GGA GTC TGG |

VIC - |

480 |

| GABRA-F GABRA-R |

CTC TTG TTC CTG TTG CTT TCA ATA CAC CAC TGT GCT AGT AGA TTC AGC TC |

NED - |

120 |

| HTTLPR-F HTTLPR-R |

ATG CCA GCA CCT AAC CCC TAA TGT GAG GGA CTG AGC TGG ACA ACC AC |

PET - |

120 |

2.2. Sample Collection and Processing Utilized to Obtain Data

Buccal cells are collected from each patient using an established minimally invasive collection kit. Sterile Copan 4N6FLOQ Swabs (Regular Size Tip In 109MM Long Dry Tube with Active Drying System) were utilized for sample collection. Individuals collect cells from both cheeks by rubbing the swab at least 25 times on each side of their mouth, and then returned the swab to the specimen tube. For all steps of sample processing, appropriate controls, including non-template controls and known DNA standards, were included and verified.

An index of the genes included in the GARS panel and the specific risk polymorphisms are provided in Table 3A-C. Each polymorphism was selected based on SUD, a subset of Reward Deficiency Syndrome (RDS), and a known contribution to a state of low dopaminergic or hypodopaminergic functioning in the brain reward circuitry. Samples were also subject to sex determination using PCR amplification and capillary electrophoresis to detect AMELX and AMELY (AMELX’s intron 1 contains a 6 bp deletion relative to intron 1 of AMELY).

Table 3C.

Dinucleotide Repeats.

| Gene | Polymorphism | Variant Alleles | Risk Allele |

|---|---|---|---|

| GABA(A) Receptor, Alpha-3 GABRB3 | rs764926719 | CA dinucleotide repeat 171–201bp sized fragments | 181 |

DNA was isolated from buccal samples using a Mag-Bind Swab DNA 96 Kit (Custom M6395–01, Omega Bio-Tek, Norcross, GA) with the MagMAX Express-96 Magnetic Particle Processor (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Extracted DNA was quantified for total human gDNA using the TaqMan RNaseP assay (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) on a QuantStudio 12k Flex (Thermo Fischer Scientific, Waltham, MA).

Testing for genetic variation was performed using 1) Real-Time PCR with TaqMan® allele-specific probes on the QuantStudio 12K Flex, or 2) iPlex reagents on the Agena MassARRAY® system, plus 3) Proflex PCR and size separation using the SeqStudio Genetic Analyzer.

For genotyping the single nucleotide polymorphisms (Table 3A) with Real-Time PCR with on the QuantStudio 12K Flex, commercially available or custom TaqMan RT-PCR assays (Thermo Fischer Scientific, Waltham, MA) were used (see Table 4A for Assay IDs and context sequences). For each reaction, 2.25µL normalized DNA (10ng total) was mixed with 2.75µL assay master mix and then subjected to RT-PCR amplification and detection. Manufacturer recommended thermal cycling conditions were utilized, and genotypes were called using TaqMan Genotyper Software v1.3 (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA).

Table 4A.

GARS Single Nucleotide Polymorphism Assays Information- Taqman.

| Assay ID | Gene & SNP | Context Sequence |

|---|---|---|

| C 1011777_10 | DRD1 rs4532 | TCTGACTGACCCCTATTCCCTGCTT [G/A] GGAACTTGAGGGGTGTCAGAGCCCC |

| C 7486676_10 | DRD2, ANKK1 rs1800497 | CACAGCCATCCTCAAAGTGCTGGTC [A/G] AGGCAGGCGCCCAGCTGGACGTCCA |

| C 949770_10 | DRD3 rs6280 | GCCCCACAGGTGTAGTTCAGGTGGC [C/T] ACTCAGCTGGCTCAGAGATGCCATA |

| C 7470700_30 | DRD4 rs1800955 | GGGCAGGGGGAGCGGGCGTGGAGGG [C/T] GCGCACGAGGTCGAGGCGAGTCCGC |

| C 25746809_50 | COMT rs4680 | CCAGCGGATGGTGGATTTCGCTGGC [A/G] TGAAGGACAAGGTGTGCATGCCTGA |

| C 8950074_1_ | OPRM1 rs1799971 | GGTCAACTTGTCCCACTTAGATGGC [A/G] ACCTGTCCGACCCATGCGGTCCGAA |

For genotyping the single nucleotide polymorphisms with the Agena MassARRAY® system, iPlex reagents were used (see Table 3B for iPlex PCR primer sequences). Primers are multiplex; therefore, only one reaction is required for each sample. For each reaction, 2 ul normalized DNA (10ng total) was mixed with the iPlex Pro PCR cocktail. The reaction was amplified on a ProFlex thermocycler with the Agena manufacturer PCR conditions. Amplified DNA was then SAP treated, followed by an extension. The iPLEX Extension Reaction Product was then desalted using a Dry Resin Method. Samples were then dispensed onto a 96well SpectroCHIP Array using the MassARRAY Nanodis-penser. Genotypes were called using the MassARRAY Analyzer Software.

Table 3B.

Simple Sequence Repeats (Variable Number Tandem Repeats & Insertion/Deletions).

| Gene | Polymorphism | Variant Alleles | Risk Allele |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dopamine D4 Receptor DRD4 | rs761010487 | 48bp repeat 2R-11R | ≥7R, long form |

| Dopamine Active Transporter DAT1 | rs28363170 | 40p repeat 3R-11R | <9R |

| Monoamine Oxidase A MAOA | rs768062321 | 30bp repeat 2R-5R | 3.5R, 4R, 5R |

| Serotonin Transporter SLC6A4 (5-HTTLPR) | rs4795541, rs25531 | 43bp repeat, with SNP L/XL and S, G/A | S, LG |

For fragment genotyping, two multiplexed PCR reactions (50µL total volume) were required. Reaction A included 5’ fluorescently labeled primers forward primers and non-labeled reverse primers for AMELOX/Y, DAT1, MAOA, and the GABRB3 dinucleotide repeat (with sets at 150nM, 120nM, 120nM, and 480nM primer concentrations, respectively). Reaction B included 5’ fluorescently labeled forward primers and non-labeled reverse primers for DRD4 and the SLC6A4 HTTLPR, all in 120nM concentrations. For all PCR reactions, 2ng DNA was amplified with primers, 25µL OneTaq HotStart MasterMix (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA), and water. For reaction B, 5µM 7-deaza-dGTP (Thermo Fischer Scientific, Waltham, MA) was added to the above recipe. Primers details are listed in Table 5.

Amplifications were performed using a touchdown PCR method. An initial 95°C incubation for 10 min was followed by two cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 65°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 60 s. The annealing temperature was decreased every two cycles from 65°C to 55°C in 2°C increments (10 cycles total), followed by 30 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 55°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 60 s, and a final 30-min incubation at 60°C, then hold at 4°C. A 10µL aliquot of reaction B amplicon was further subjected to MspI restriction digest (37°C for 1hr) to interrogate rs25531 (with 1U restriction enzyme and 1X Tango Buffer, Thermo Fischer Scientific, Waltham, MA).

For fragment detection by capillary electrophoresis, reactions 1 and 2 were mixed in a 2:1 ratio. 1µL of this amplicon mixture was added to 9.5µL mixed LIZ1200 size standard/-formamide (Thermo Fischer Scientific, Waltham, MA recommended concentrations). For detection of rs25531, 1uL of restriction digest mixture was added to 9.5µL LIZ1200+-formamide. Both mixtures were subjected to capillary electrophoresis on the SeqStudio (run time 60min, voltage 5000V, 10 sec injection at 1200V) then analyzed with GeneMapper 5 software (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA).

The patient/clinician who requests the test receives a personalized report discussing the results. The report provides a GARS Score (based on a scale 1–22) that is the sum of all risk alleles for that individual. Various substance and non--substance behaviors are listed as high, moderate, or low-risk behavior frequency for that individual. The reports are designed to help users understand the meaning of their results and any appropriate actions that may be taken.

3. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Figure 2 represents the prevalence of eleven alleles linked to a ten GARS gene panel. The mixed-gender pie charts (Figures Fig. 2A, Fig. 2B) represent the percent addiction risk for drugs (based on ≥ 4 alleles) and the percent addiction risk for alcohol (based on ≥ 7 alleles). In this cohort, we show that only one subject out of 22 adolescents did not carry at least four alleles. Figure 2A shows 95% indicating a high risk for drug severity. In terms of alcohol risk in the same cohort of 22 subjects, in Figure 2B, 14 out of 22, show high risk for alcohol severity risk, compared to 8 out of 22 showing a low risk.

Fig. (2).

GARS results in 22 Caucasian adolescents in the United States. Substance Use Disorder = SUD; Alcohol Use Disorder =AUD. (A higher resolution / colour version of this figure is available in the electronic copy of the article).

This result is consistent with continued work revealing that in a white mixed-gender population (N=293), derived from the United States, we found GARS testing resulted in the following: high alcohol severity (N=197) or 64% of the sample, compared to high drug severity (N=288) or 98%,with low drug risk (N=5) or 2% of the sample.

3.1. Neurogenetic Risk (Hypodopaminergia - Deficit)

As presented by this preliminary case- series,, adolescents from families having RDS issues show a high genetic risk for both drugs and alcohol. This genetic hypodopaminergia finding is not surprising, given a rather high familiar heritability of addictive behaviors [12]. Blum’s group reported that carriers of the DRD2 A1 allele, using the Bayesian theorem, possess a Predictive Value of 74% for one or more RDS behaviors.

3.2. Epigenetic Risk (Hyperdopaminergia - Surfeit)

Epigenetic changes are heritable, phenotypical changes that do not involve alterations in the DNA sequence. They shape gene activity and RNA-induced protein expression and influence cellular and phenotypic traits. Epigenetic changes are part of healthy development and result from external or environmental factors, especially as seen in adolescent brain development [13].

Examples of mechanisms that produce such epigenetic changes are DNA methylation and modification of histones on chromosome structure. For the most part, histone methylation alters gene expression, not the underlying DNA sequence. Bird [14] also adds that these gene expression changes may last despite cell lifetime division duration and may also last for multiple generations, without involving changes in the underlying DNA sequence of the organism. De-acetylation on histone increases acetylation content and is also known to enhance RNA gene expression.

Moreover, as defined by Berger et al., “An epigenetic trait is a stably heritable phenotype resulting from changes in a chromosome without alterations in the DNA sequence” [15].

An extracellular signal, referred to as the “Epigenator,” originates from the environment and can trigger the epigenetic pathway. The “Epigenetic Initiator” receives the signal from the “Epigenator” and determines the precise chromatin DNA for the establishment of the epigenetic pathway and the “Epigenetic Maintainer” functions to sustain the chromatin environment initially and during succeeding generations. The persistence of the chromatin milieu may require cooperation between the Initiator and the Maintainer. Thus, the consensus definition of “epigenetic” requires a trait to be heritable (see Fig. 3) [15].

Fig. (3).

Epigenetic mecanisms illustrated. (A higher resolution / colour version of this figure is available in the electronic copy of the article).

Fig. 3. Epigenetics is a relatively new field of molecular biology dealing with regulatory mechanisms of gene activity and inheritance that are independent of changes in the nucleotide sequence of DNA. Epigenetics forms a layer of control that determines which genes are turned off and which genes are turned on in particular cells in the body (active versus inactive genes). They do this by making chemical modifications of chromosomal DNA and/or structures that change the pattern of gene expression without altering the DNA sequence. In fact, epigenetics is the study of heritable changes in gene expression that happen without involving any changes to the basic DNA sequence, which ultimately results in a change in the phenotype without a change in the genotype. Epigenetic changes can be influenced by several factors, including age, environment, and particular disease state. Every cell has the same DNA, but every cell has a different function, and the expression patterns of genes are different in each particular cell type. For example, enzyme secreting cells in the intestinal epithelial help break down food. Every cell has its specified function, and that specified function is determined by which genes are on and which genes are off. There are at least 3 different epigenetic mechanisms that have been identified, including DNA methylation, histone modification, and non-coding RNA (ncR-NA)-associated gene silencing, each of which alters how genes are expressed without altering the underlying DNA sequence. Several factors and processes, including development in utero and in childhood, environmental chemicals, drugs and pharmaceuticals, aging, and diet affecting Epigenetic mechanisms. DNA methylation is what occurs when methyl groups, an epigenetic factor found in some dietary sources, can tag DNA and activate or repress genes. During deacetylation there is a removal of an acetyl group on Histones which causes decrease gene expression. Histones are proteins around which DNA can wind for compaction and gene regulation. Histone modification occurs when the binding of epigenetic factors to histone “tails” alters the extent to which DNA is wrapped around histones and the availability of genes in the DNA to be activated. All of these factors and processes can have an effect on people’s health and influence their health, possibly resulting in cancer, autoimmune disease, mental disorders, or diabetes, among other illnesses.

Currently, there seems to be a controversy regarding the possibility that the developing brain of adolescents displays hyperdopaminergia [Prenatal THC exposure produces a hyperdopaminergic phenotype rescued by pregnenolone; Neuroadaptive changes and behavioral effects after a sensitization regime of MDPV; Psychotic like experiences as part of a continuum of psychosis: Associations with effort-based decision-making and reward responsivity; Adolescent Synthetic Cannabinoid Exposure Produces Enduring Changes in Dopamine Neuron Activity in a Rodent Model of Schizophrenia Susceptibility; Amygdala Hyperactivity in MAM Model of Schizophrenia is Normalized by Peripubertal Diazepam Administration; Dopamine dysfunction in AD/HD: integrating clinical and basic neuroscience research; Adolescent Cannabinoid Exposure Induces a Persistent Sub-Cortical Hyper-Dopaminergic State and Associated Molecular Adaptations in the Prefrontal Cortex; Aripiprazole in children with Tourette’s disorder and co-morbid attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a 12-week, open-label, preliminary study; The antemortem neurobehavior in fatal paramethoxymetham-phetamine usage; Effects of fluoxetine treatment on striatal dopamine transporter binding and cerebrospinal fluid insulin-like growth factor-1 in children with autism; Neuroleptics, catecholamines, and psychoses: a study of their interrelations] despite potentially having genetically-induced hypodopaminergia. This conundrum makes it very difficult actually to treat high-risk addiction-prone adolescents. The authors are becoming increasingly concerned about the involvement of pre-teenagers and young adults with substance use as a way of relieving stress and anger. The reason for the continued neurogenetic investigation of brain function is the underdevelopment of the adolescent prefrontal cortex (PFC).

During adolescence, the PFC development is undergoing significant changes and, as such, may hijack appropriate decision-making in this population [17]. Thus, early genetic testing for addiction risk alleles seems prudent and may help encourage adolescents to avoid known risky behaviors like the use of psychoactive drugs. The consensus of the literature highlights the importance of epigenetics as it relates to family history and parenting styles such as child abuse. There is also agreement that reward-genes and bonding substances (like oxytocin and vasopressin, which influence dopaminergic function) modify “attachment.”

Interestingly, well-controlled, neuroimaging experiments reflect region-specific, differential responses to drugs, food, and other non-substance-addictive behaviors) via either “surfeit” or “deficit.” For example, a hyperdopaminergia in young adults may trigger an exacerbated euphoria from drugs and alcohol and even non-drug behaviors as well like gaming.

3.3. Controversy About Dopaminergic Trait in Adolescents

Dopamine is crucially important during adolescence. The protracted development of dopamine signaling pathways leads to cognitive impediments that can affect decisions about behavior. Dopamine also has a role in psychopathology [18]. One positive study in rats by Kang et al. [19] suggests dopamine receptor functionality in the Prelimbic cortex (PLC) increases during adolescent development, playing an essential role in this late-maturating form of plasticity. Aguilar et al. [20] exposed adolescent rats to synthetic cannabinoids and found that, when compared to controls treated with saline, a significant proportion displayed a schizophrenia-like hyperdopaminergic phenotype. The results of this experiment provide evidence that adolescent synthetic cannabinoid exposure may contribute to psychosis in susceptible individuals in the form of hyperdopaminergia.

During adolescence, the dopamine system undergoes essential remodeling and maturation. Early-life stress augments the risk of psychopathologies during adolescence and adulthood and interferes with the maturation of the dopamine system. Majcher-Maslanka et al. [21], have shown that maternal separation (MS) enhanced the density of tyrosine hydroxylase immunoreactive fibers in the PLC and nucleus accumbens (NAc). Importantly, these alterations accompanied a reduced level of D5 receptor mRNA and an increase in D2 receptor mRNA expression in the PLC of MS females only. In contrast, D1 and D5 receptor mRNA levels were augmented in the Caudate Putamen (CP), while the expression of the D3 dopamine receptor transcript was lower in MS females. In the NAc, MS elicited a decrease in D2 receptor mRNA expression. Zbukvic et al. [22], highlighted the significance of D2R signaling in the infralimbic cortex (IL) for cue extinction during adolescence. Cue extinction is a learned behavior that fades when not reinforced, for example, a failure to extinguish conditioned fear. They found that adolescents may be more susceptible to relapse due to a deficit in cue extinction. These findings may have relevance for the development of, for example, nutrigenomic tools that balance dopamine, especially, in IL.

Undoubtedly, peer-drinking norms are arguably one of the strongest motivators for adolescent drinking. In an experiment by Park and associates [23], a significant difference was found between adolescents, compared to college students. In the younger cohort, group selection to drink was associated with socialization and peer norm drinking beliefs, not DRD4 genotype. On the other hand, in the college cohort group, selection and friendships formed, especially with those who drink heavily as a function of DRD4 seven-repeat allele genotypes showing a difference between these two age groups. Shnitko et al. [24], based on rodent studies, suggested that exposure to binge levels of ethanol during adolescence seems to blunt the effect of ethanol challenge and to reduce the amplitude of phasic dopamine release in adulthood. However, more extracellular dopamine after alcohol challenge in adolescent-exposed rats may be one mechanism by which alcohol is more reinforcing in people who initiated drinking at an early age. Ernst et al. [25], based on neuroimaging studies, suggest that chronic marijuana use reduces incentive motivation and impacts the developing dopamine system, leading to deficiencies in goal-directed activities. Furthermore, adolescent alcohol-use, remains a foremost public health issue, in part, because of well-established findings that implicate the age of onset in alcohol use with the development of alcohol use disorders. Persistent decision-making deficits in adults may not only have genetic antecedents but maybe the sequelae of epigenetic insults and or a combination of both.

Spoelder et al. [26], show that moderate adolescent alcohol consumption potentiates stimulus-evoked phasic dopamine transmission in adulthood, and this hyperdopaminergia sets up individuals toward a dopamine-dependent incentive learning strategy [18]. The psychostimulant methylphenidate (MPH), a conventional treatment for Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), is also misused by adolescence in both clinical and general populations. Amodeo et al. [27], using a Reward Magnitude Discrimination task, provided evidence that MPH exposure in adolescents reduced preference for large rewards but did not affect preference for smaller-sooner rewards in a Delay Discounting task.The take-home message is that people who want reward now instead of later maybe be more prone to addictive like behaviors. However, it is noteworthy that in adulthood, MPH augmented mRNA expression of dopamine D3 receptor subtype, but not D1 or D2. This information is important because it is known that DRD3 polymorphisms load onto abnormal

In terms of peer pressure, Cao et al. [28], found evidence to suggest that carrying COMT Val/Val and DAT1 CC polymorphisms indicate a hypodopaminergia, which is more sensitive to peer acceptance than other genotype combinations. This finding may have relevance to peer inducement of alcohol and other drug-seeking behavior. Moreover, adult psychiatric disorders characterized by cognitive deficits reliant on PFC dopamine have been associated with teenage bullying. Weber et al. [29], in a related study, found that exposure to adolescent defeat caused more decreases in extracellular dopamine release in the adult medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC), upon local infusion of the D2 receptor agonist, quinpirole (3 nM). This finding implies better D2 autoreceptor function, which is suggestive of hypodopaminergia. Equally, augmented D2 autoreceptor-mediated inhibition of dopamine release seen in the adolescent mPFC of defeated adolescent rats; [Enhanced dopamine D2 autoreceptor function in the adult prefrontal cortex contributes to dopamine hypoactivity following adolescent social stress]compared to declines in D2 auro-receptor-mediated inhibition [Species differences in somatodendritic dopamine transmission determine D2-autoreceptor-mediated inhibition of ventral tegmental area neuron firing.] for control rats by adulthood. Interpretation of these findings indicates adolescent defeat (as seen in bullying) decreases extracellular dopamine availability in the adult mPFC via enhanced inhibition of dopamine release and increased dopamine clearance, causing hypodopaminergia and not hyperdopaminergia. These findings point to a potentially critical target for inducing dopamine balance or regulation via the adoption of our Precision Addiction Management (PAM) solution [9, 30]. Other work by Watt et al. [31] supports this notion that both the developing and mature PFC DA systems are vulnerable to social stress, but only adolescent defeat causes DA hypofunction. The mechanism seems to result, in part, from stress-induced activation of mPFC D2 autoreceptors.

The development and maintenance of addictions occur in the ventral tegmental area (VTA), part of the mesencephalic dopamine system. The dopamine regulatory factors TH, Nurr1, and Pitx3, are disrupted, especially, by morphine dependence [32]. Montagud-Romero et al. [33], found that adolescent-defeated mice, compared to non- defeated adolescent exposed adult mice, had a reduction in levels of the Pitx3 transcription factors in the VTA, but no changes in the expression of D2DR and DAT in the NAc. This finding helps explain why socially defeated adolescent mice developed “conditioned place preference” for the compartment associated with low doses of cocaine. Novick et al. [34], also, studying bullying as represented by social defeat, found that rats exposed to adolescent social defeat, demonstrated decreased DA signal accumulation, compared to controls, with the mechanism thought to be an enhanced DAT1 expression, leading to hypodopaminergia.

For the most part, gene-environment interaction research on depression has focused on negative epigenetics. However, Zhang et al. [35], investigated prospective, longitudinal effects of maternal parenting, the DRD2 TaqIA polymorphism, and their interaction on adolescent depressive symptoms in a Chinese cohort. Their results suggested that maternal positive and negative parenting significantly predicted adolescent depressive symptoms. Specifically, TaqIA polymorphism interacted with negative parenting in predicting concurrent depressive symptoms at age 11 and 12 but lost significance at age 13. Carriers of the A1 allele were more susceptible to negative parenting compared to A2A2 homozygotes, such that adolescents carrying A1 alleles experiencing high negative parenting reported more depressive symptoms but fared better when experiencing low negative parenting [35]. This work shows the importance of gene-environment interaction rather than genetic determinism alone.

Finally, adolescence is a developmental period of complex, neurobiological change linked to heightened vulnerability to psychiatric illness, including RDS. Thus, it is essential to understand factors, such as sex and stress hormones known to drive changes in adolescent brains, which may influence critical neurotransmitter systems implicated in psychiatric illness, especially, dopaminergic ones. According to Sinclair et al. [36], in adolescence and early adulthood, testosterone, estrogen, and glucocorticoids interact and have distinct region-specific impacts on adolescent dopamine neurotransmission that shape neurological maturation and cognitive function. Some of the effect hormones (explain?) modulate dopamine neurotransmission. The effect is similar to dopaminergic abnormalities, like dopamine surfeit, observed in schizophrenia and may influence the risk for psychiatric illness.

The global opioid epidemic is hijacking our youth and preventing their leading healthy, productive lives, free from addictive behaviors that cause premature death [1, 2]. To combat this scenario, the system illustrated here combines early genetic risk diagnosis, medical monitoring, and precision neuronutrient pro-dopaminergic therapy [37, 38].

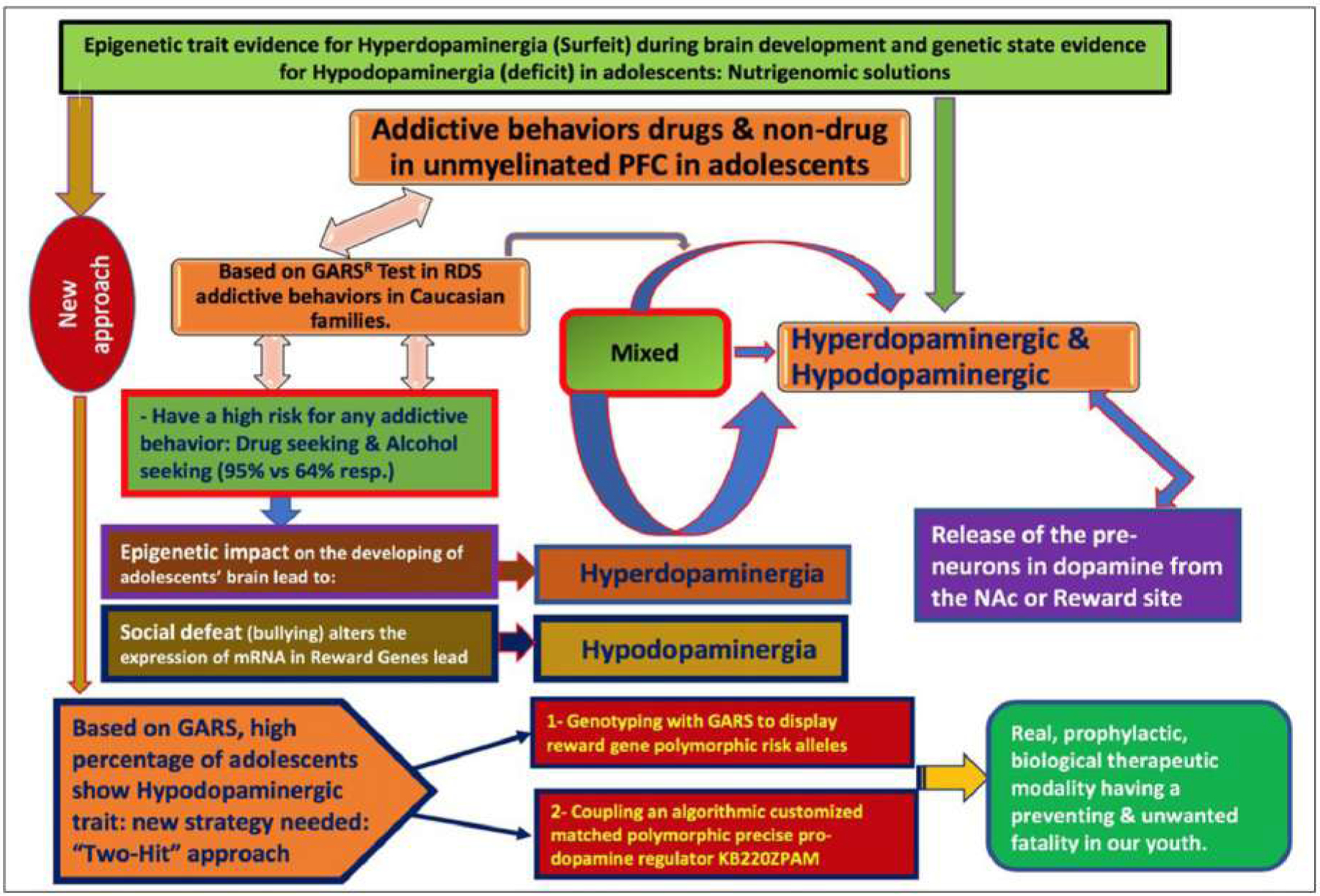

The following schematic provides an easy-to-follow model of the authors’ hypothesis (see Fig. 4).

Fig. (4).

Schematic representation of Exploration Of Epigenetic State Hyperdopaminergia (Surfeit) And Genetic Trait Hypodopaminergia (Deficit) During Adolescent Brain Development. (A higher resolution / colour version of this figure is available in the electronic copy of the article).

Fig. 4. describes the risk for all addictive behaviors, of both a drug and non –drug nature, especially, in the unmyelinated PFC in adolescents. It is well known that the risk for all addictive behaviors is not only important but quite complex. The primary issue in this figure suggests a mixed combination of both hypo and hyperdopaminergic. Based on our very preliminary data, involving the GARS test in RDS addictive behaviors in Caucasian families, we find that Caucasians of ages of 12–19, from families with RDS addictive behaviors, especially drug-seeking (95%) and alcohol-seeking (64%) display a high risk for any addictive behavior. However, there are a plethora of research studies that show the epigenetic impact on the developing brain in adolescents, compared to adults reveal a hyperdopaminergia that seems to set our youth up for risky behavior involving a higher quanta release of dopamine from the pre-neurons in the NAc or reward site. It also appears that social defeat, like bullying, alters the expression of reward gene mRNA in reward genes lead to Hypodopaminergia, especially in adolescent brains, which carries over into adulthood. A new approach to understand the epigenetic state evidence for hyperdopaminergic (surfeit) during brain development and genetic traits evidence for hypodopaminergia (deficit) in adolescents: nutrigenomic solutions is warranted. This new approach is based on GARS, where a high percentage of adolescents show a Hypodopaminergic state. Indeed, a new strategy composed of the “Two-Hit” approach is needed to understand this phenomenon: The first suggests Genotyping with GARS to display reward gene polymorphic risk alleles and the second is coupling an algorithmic customized matched polymorphic precise pro-dopamine regulator KB220ZPAM. Both approaches lead to a real, prophylactic, biological therapeutic modality having a preventive and unwanted fatality in our youth.

3.4. Limitations and Issues

While we seem to have found an interesting, genetic hypodopaminergia in our very small sample of adolescents, we must consider this finding preliminary, at best and, as such, requiring larger cohorts. Moreover, our findings are not surprising, given the fact that these adolescent subjects were from a parental RDS base. Newer work must consider comparing RDS-related parents with non-RDS parents.

Moreover, evidence from animal work has shown that hypodopaminergic states in the NAc, usually do not modify consummatory behaviour, or the motivation to eat, but rather it affects behavioural invigoration, effort-related behaviors and instrumental learning [39]. While at first glance their conclusion may seem accurate, other work does not support this assumption at all. Consistent with the theory that individuals with hypo-functioning reward circuitry overeat to compensate for a reward deficit, obese versus lean humans have fewer striatal D2 receptors and show less striatal response to palatable food intake. Low striatal response to food intake predicts future weight gain in those at genetic risk for reduced signaling of dopamine-based reward circuitry. Yet animal studies indicate that intake of palatable food results in downregulation of D2 receptors, reduced D2 sensitivity, and decreased reward sensitivity, implying that overeating may contribute to reduced striatal responsivity. The authors found that women who gained weight over a 6 month period showed a reduction in striatal response to palatable food consumption relative to weight-stable women. Collectively, Other work results suggest that low sensitivity of reward circuitry (including hypodopaminergia) increases the risk for overeating and that this overeating may further attenuate responsivity of reward circuitry in a feed-forward process.

Further support is derived from Bello & Hajnal [41] following an exhaustive review revealed: “ studies on the comorbidity of illicit drug use and eating disorders, the data reviewed here support a role for dopamine in perpetuating the compulsive feeding patterns of binge eating Disorder(BED)”. They suggested that sustained stimulation of the dopamine systems by bingeing promoted by preexisting conditions (e.g., genetic traits, dietary restraint, stress, etc.) results in progressive impairments of dopamine signaling. In addition, the brain reward circuits that promote drug abuse may also be involved in pleasure-seeking behavior and food cravings observed in severely obese subjects. Drug addiction polymorphisms such as the TaqI A1 allele of the dopamine D2 receptor (DRD2) are associated with cocaine, alcohol, and opioid use [42]. Other genes such as the leptin receptor gene (LEPR) and mu-opioid receptor gene (OPRM1) that affect appetite and pleasure centers in the brain may also influence food addiction and obesity. Carpenter et al. [42], showed that these three genes together may function synergistically and could induce a hypodopaminergia. However, the DRD2 TaqI A1 allele was significantly associated with BMI (P=0.04), while LEPR Lys109Arg and OPRM1 A118G variants were not. They stratified DRD2 by LEPR and OPRM1, and they observed a significant interaction (P = 0.04) between DRD2 and LEPR, and a marginally significant interaction (P=0.06) between DRD2 and OPRM1. The literature is rift with many other studies since the 2012 report by [39] showing increased generalized craving behavior with reduced phasic dopamine. In fact, recently, Chen et al. [43], demonstrated that low levels of D2Rs in both the VTA and NAc regions increase low doses of cocaine intake.

While we discussed earlier in this article the potential role of epigenetics, it is imperative to point out that there is emerging evidence that clearly shows epigenetic events on specific dopamine genes in the brain and lifetime RDS behaviors. Hillemacher et al. [44] found DNA-methylation patterns in the DRD2-gene. In fact, it was found that the DRD2 gene was altered in respect to abstinence over a 12-month or a 30-month period and to treatment utilization with higher methylation levels in non-abstinent and participants without treatment-seeking behavior. These results point towards a pathophysiologic relevance of altered DRD2-expression due to changes of DNA methylation in the brain of pathologic gambling behavior.

One other issue that limits our interpretation of these results relates to an inability to refine the important historical backgrounds of each proband in this study. It would have been important to include the previous history of their use/misuse of not only alcohol but illicit drug abuse. In addition, information regarding parenting, including early life stress as well as the history of mental and physical abuse.

In order to understand the issue surrounding the best practice to determine genetic association to a disease, it is mandatory, in our opinion, to carefully remove all RDS hidden diseases from any controls. These highly screened controls have been named “Super Controls”. The search for an accurate, gene-based test to identify heritable risk factors for RDS was conducted based on hundreds of published studies about the role of dopamine in addictive behaviors, including risk for drug dependence and compulsive/impulsive behavior disorders. The term RDS was first coined by Blum’s group in 1995 to identify a group of behaviors with a common neurobiological mechanism associated with a polymorphic allelic propensity for hypodopaminergia. To address the limitations caused by inconsistent results that occur in many case-controls behavioral association studies, we impose the development of these “Super Controls”. These limitations are perhaps due to the failure of investigators to adequately screen controls for drug and alcohol use disorder and any of the many RDS behaviors, including nicotine dependence, obesity, pathological gambling, and internet gaming addiction. Unlike one gene-one disease (OGOD), RDS is polygenetic and very complex. In addition, any RDS-related behaviors must be eliminated from the control group in order to obtain the best possible statistical analysis instead of comparing the phenotype with disease-ridden controls. In one particular study our laboratory accomplished this only with the DRD2 A1 allele, whereby the prevalence of the DRD2 A1 allele in unscreened controls (33.3%), compared to “Super-Controls” [highly screened RDS controls (3.3%) in proband and family] is used to exemplify a possible solution [45].

We are facing a significant challenge in combatting the current opioid and drug epidemic worldwide. In the USA, although there has been notable progress, in 2017 alone, 72,000 people died from a narcotic overdose. The NIAAA & NIDA continue to struggle with innovation to curb or eliminate this unwanted epidemic. The current FDA list of approved Medication Assistance Treatments (MATS) works by primarily blocking dopamine function and release at the pre-neuron in the nucleus accumbens. We oppose this option in the long-term tertiary treatment but agree for short-term harm reduction potential [46]. As an alternative motif, the utilization of a well-researched neuro-nutrient called KB220 has been intensely investigated in at least 40 studies showing evident effects related to everything from AMA rate, attenuation of craving behavior, reward system activation, including BOLD dopamine signaling, relapse prevention, as well as a reduction in stress, anger, improved mood, and aggressive behaviors. We are continuing research, especially as it relates to genetic risk, including the now patented Genetic Addiction Risk Score (GARS®) and the development of “Precision Addiction Management (PAM)” to potentially combat the opioid/psychostimulant epidemic. Based on animal research and clinical trials as presented in a published annotated bibliography [47], the Pro-Dopamine Regulator known as KB220 shows promise in the addiction and pain space. Other neurobiological and genetic studies are required to help understand the mechanism of action of this neuro-nutrient. However, the evidence to date points to induction of “dopamine homeostasis” enabling an asymptotic approach for epigenetic induced “normalization” of brain neurotransmitter signaling and associated improved function in the face of either genetic or epigenetic impairment of the Brain Reward Cascade (BRC).With that said, we are encouraged about these results as published over the last 50 years and look forward to continued advancements related to appropriate nutrigenomic solutions to the millions of victims of all addictions (from drugs to food to smoking to gambling and gaming especially in our next generation) called Reward Surfeit Syndrome (RSS) in adolescents as an epigenetic state and Reward Deficiency Syndrome (RDS) in adulthood as a trait.

There is also concern as to how the dopaminergic function can be altered during pregnancy with various drugs of abuse. In fact, this is very important as we consider the topic of this article. While it may be true, especially in families of RDS siblings who may display a DNA measured hypodopaminergic trait, the use and misuse of drugs during pregnancy such as heroin and even nicotine may induce an unwanted “hyperdopaminergia “ or surfeit and as such, increase ones risk. According, Romili et al. [48] suggested that neonatal nicotine exposure potentiates drug preference in adult mice, induces alterations in calcium spike activity of midbrain neurons, and increases the number of dopamine-expressing neurons in the ventral tegmental area. Specifically, glutamatergic neurons are first primed to express transcription factor Nurr1, then acquire the dopaminergic phenotype following nicotine re-exposure in adulthood. Enhanced neuronal activity combined with Nurr1 expression is both necessary and sufficient for the nicotine-mediated neurotransmitter plasticity to occur. This could result in increased subsequent proband use of drugs in the future because of this epigenetic insult. Moreover, Dalterio et al. [49], showed that following perinatal exposure to delta 9-THC in mice increased enkephalin and sensitivity in vas deferens. This pharmacological effect could potentially induce increased use of for example of opioid type drugs like heroin.

Finally, there is always the question of genetic polymorphisms as a function of ancestry. Along these lines, many studies exclude non-White individuals. Studies that include diverse populations report ethnicity-specific frequencies of risk genes, with certain polymorphisms specifically associated with Caucasian and not African-American or Hispanic susceptibility to OUD or SUDs, and vice versa. To adapt precision medicine-based addiction management in a blended society, we propose that ethnicity/ancestry-informed genetic variations must be analyzed to provide real precision-guided therapeutics with the intent to attenuate this uncontrollable fatal epidemic [50].

CONCLUSION

Understanding the risk for all addictive behaviors of both a drug and non-drug nature, especially in the unmyelinated PFC in adolescents, is not only necessary but quite complex. The primary issue, as presented in this paper, suggests the existence of a combination of both hypo and hyperdopaminergia in this group. Based on our very preliminary data, involving the GARS, we find that Caucasians of ages of 12–19, from families with RDS addictive behaviors, display risk for hypodopaminergia and have a high risk for any addictive behavior, especially drug-seeking (95%) and alcohol-seeking (64%). However, there is a plethora of both animal and human research studies that show the epigenetic impact on the developing brain in adolescents compared to adults. Specifically, many studies reveal a hyperdopaminergia that seems to set our youth up for risky behavior involving a higher quanta release of dopamine from the pre-neurons in the NAc or reward site.

It also appears that social defeat, like bullying, alters the expression of reward gene mRNA, especially, in adolescent brains, which carries over into adulthood. In contrast, there is also evidence that, through epigenetic events, adolescents can display hypodopaminergia. This complexity, as expressed here, suggests that the neuroscience community cannot make a unilateral claim that all adolescents possess a hyperdopaminergic trait, especially in the face of with the preliminary knowledge, as suggested here, that, in the United States, there seems to an underlying hypodopaminergia in the general population. Additional, extensive population studies in the United States are required to verify recent results, obtained with only 293 white, mixed-gender subjects, who showed a very high percentage of risk, based on gene polymorphisms linked to low dopamine function. If this finding remains, following more population-based genetic studies using GARS, we should ask the question: Is this the reason for America’s current opioid epidemic?

Unfortunately, hyperdopaminergia vs. hypodopaminergia makes a singular treatment very difficult. The real dilemma is how, as clinicians, do we accurately differentiate, at birth, genetics from environmental impact with epigenetic phenomena, which results in the generation of either a hyper- or a hypo-dopaminergic state. While it is possible to use resting state, functional magnetic resonance imaging (rsfM-RI) to obtain evidence for BOLD dopamine activation across the mesolimbic system in order to show a dopaminergic state, either hypo or hyper, this approach is not clinically feasible. Nevertheless, it might be wise to genotype at an early age with the GARS test and, based on these results, attempt epigenetically to influence dopamine balance [37], and treat hypodopaminergia with a precision neuronutrient dopamine restoration, as with KB200z.

Table 4B.

GARS Single Nucleotide Polymorphism Assays Information- iPlex.

| Gene | SNP | UEP DIR | UEP SEQ | EXT1 Call | EXT1 SEQ | EXT2 Call | EXT2 Seq |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COMT | rs4680 | R | CACACCTTGTCCTTCA | G | CACACCTTGTCCTTCAC | A | CACACCTTGTCCTTCAT |

| DRD3 | rs6280 | F | GTGTAGTTCAGGTGGC | C | GTGTAGTTCAGGTGGCC | T | GTGTAGTTCAGGTGGCT |

| DRD2 | rs1800497 | F | TCCTCAAAGTGCTGGTC | A | TCCTCAAAGTGCTGGTCA | G | TCCTCAAAGTGCTGGTCG |

| DRD4 | rs1800955 | F | gtAGCGGGCGTGGAGGG | C | gtAGCGGGCGTGGAGGGC | T | gtAGCGGGCGTGGAGGGT |

| OPRM1 | rs1799971 | F | CTTGTCCCACTTAGATGGC | A | CTTGTCCCACTTAGATGGCA | G | CTTGTCCCACTTAGATGGCG |

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We appreciate the expert edits of Margaret A. Madigan, and the assistance of Geneus Health LLC staff especially Erin Gallagher. We are also grateful to Jessica Valdez-Ponce and Lisa Lott of Geneus Health LLC. The authors are appreciative of the formatting by Dr. Sampada Badgaiyan.

FUNDING

The work of RDB was partially supported by the National Institutes of Health grants 1R01NS073884 and 1R21 MH073624. MG-L is the recipient of R01 AA021262/AA/-NIAAA NIH HHS/United States. KB and MG-L are the recipients of R41 MD012318/NIMHD NIH HHS/United States. PT is the recipient of R01HD70888–01A1. The work the NY Research Foundation funds PT (RIAQ0940) and the NIH (DA035923 and DA035949)

Footnotes

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Not applicable.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

KB is the chairman and CSO of the Geneus Health Board of Directors and CSO. He is the inventor of GARS and the pro-dopamine regulator (KB220Pam) and is credited with the patents issued and pending. Through their company, Igene KB owns stock in Geneus Health LLC. KB is also the chairman of the Board of Directors and Scientific Advisory Board of Geneus Health that includes MGL, EJM, PKT, RDB, and DB. There are no other conflicts to report.

Publisher's Disclaimer: DISCLAIMER: The above article has been published, as is, ahead-of-print, to provide early visibility but is not the final version. Major publication processes like copyediting, proofing, typesetting and further review are still to be done and may lead to changes in the final published version, if it is eventually published. All legal disclaimers that apply to the final published article also apply to this ahead-of-print version.

REFERENCES

- [1].Merikangas KR, Gelernter CS. Comorbidity for alcoholism and depression. Psychiatr Clin North Am 1990; 13(4): 613–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Blum K, Noble EP, Sheridan PJ, et al. Allelic association of human dopamine D2 receptor gene in alcoholism. JAMA 1990; 263(15): 2055–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Noble EP, Blum K, Ritchie T, Montgomery A, Sheridan PJ. Allelic association of the D2 dopamine receptor gene with receptor-binding characteristics in alcoholism. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1991; 48(7): 648–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Blum K. Reward Deficiency Syndrome.The Sage Encyclopedia of Abnormal Clinical Psychology Pensylvania Sage Publications; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- [5].Blum K, Sheridan PJ, Wood RC, et al. The D2 dopamine receptor gene as a determinant of reward deficiency syndrome. J R Soc Med 1996; 89(7): 396–400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Bolos AM, Dean M, Lucas-Derse S, Ramsburg M, Brown GL, Goldman D. Population and pedigree studies reveal a lack of association between the dopamine D2 receptor gene and alcoholism. JAMA 1990; 264(24): 3156–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Chen AL, Blum K, Chen TJ, et al. Correlation of the Taq1 dopamine D2 receptor gene and percent body fat in obese and screened control subjects: a preliminary report. Food Funct 2012; 3(1): 40–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Center for Disease Control and Prevention NCfHS, National Vital Statistics System, Mortality File. Today’s Heroin Epidemic CDC Vital Signs 2015. [Google Scholar]

- [9].Blum K, Gondré-Lewis MC, Baron D, et al. Introducing Precision Addiction Management of Reward Deficiency Syndrome, the Construct That Underpins All Addictive Behaviors. Front Psychiatry 2018; 9(548): 548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Ritchie T, Noble EP. [3H]naloxone binding in the human brain: alcoholism and the TaqI A D2 dopamine receptor polymorphism. Brain Res 1996; 718(1–2): 193–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Blum K, Modestino EJ, Badgaiyan RD, et al. Analysis of Evidence for the Combination of Pro-dopamine Regulator (KB220-PAM) and Naltrexone to Prevent Opioid Use Disorder Relapse. EC Psychol Psychiatr 2018; 7(8): 564–79. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Blum K, Wood RC, Braverman ER, Chen TJ, Sheridan PJ. The D2 dopamine receptor gene as a predictor of compulsive disease: Bayes’ theorem. Funct Neurol 1995; 10(1): 37–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Dupont C, Armant DR, Brenner CA. Epigenetics: definition, mechanisms and clinical perspective. Semin Reprod Med 2009; 27(5): 351–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Bird A. Perceptions of epigenetics. Nature 2007; 447(7143): 396–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Berger SL, Kouzarides T, Shiekhattar R, Shilatifard A. An operational definition of epigenetics. Genes Dev 2009; 23(7): 781–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].NIH. Illustration Epigenetic mechanisms 2019.http://commonfund.nih.gov/epigenomics/figure.aspx

- [17].Blum K, Febo M, Smith DE, et al. Neurogenetic and epigenetic correlates of adolescent predisposition to and risk for addictive behaviors as a function of prefrontal cortex dysregulation. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 2015; 25(4): 286–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Padmanabhan A, Luna B. Developmental imaging genetics: linking dopamine function to adolescent behavior. Brain Cogn 2014; 89: 27–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Kang S, Cox CL, Gulley JM. High frequency stimulation-induced plasticity in the prelimbic cortex of rats emerges during adolescent development and is associated with an increase in dopamine receptor function. Neuropharmacology 2018; 141: 158–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Aguilar DD, Giuffrida A, Lodge DJ. Adolescent Synthetic Cannabinoid Exposure Produces Enduring Changes in Dopamine Neuron Activity in a Rodent Model of Schizophrenia Susceptibility. The international journal of neuropsychopharmacology / official scientific journal of the Collegium Internationale Neuropsychopharmacologicum (CINP) 2018; 21(4): 393–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Majcher-Maślanka I, Solarz A, Wędzony K, Chocyk A. The effects of early-life stress on dopamine system function in adolescent female rats. Int J Dev Neurosci 2017; 57: 24–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Zbukvic IC, Ganella DE, Perry CJ, Madsen HB, Bye CR, Lawrence AJ, et al. Role of Dopamine 2 Receptor in Impaired Drug-Cue Extinction in Adolescent Rats. Cerebral cortex (New York, NY : 1991) 2016; 26(6): 2895–904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Park A, Kim J, Zaso MJ, et al. The interaction between the dopamine receptor D4 (DRD4) variable number tandem repeat polymorphism and perceived peer drinking norms in adolescent alcohol use and misuse. Dev Psychopathol 2017; 29(1): 173–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Shnitko TA, Spear LP, Robinson DL. Adolescent binge-like alcohol alters sensitivity to acute alcohol effects on dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens of adult rats. Psychopharmacology (Ber-l) 2016; 233(3): 361–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Ernst M, Luciana M. Neuroimaging of the dopamine/reward system in adolescent drug use. CNS Spectr 2015; 20(4): 427–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Spoelder M, Tsutsui KT, Lesscher HM, Vanderschuren LJ, Clark JJ. Adolescent Alcohol Exposure Amplifies the Incentive Value of Reward-Predictive Cues Through Potentiation of Phasic Dopamine Signaling. Neuropsychopharmacology : official publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology 2015; 40(13): 2873–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Amodeo LR, Jacobs-Brichford E, McMurray MS, Roitman JD. Acute and long-term effects of adolescent methylphenidate on decision-making and dopamine receptor mRNA expression in the or-bitofrontal cortex. Behav Brain Res 2017; 324: 100–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Cao Y, Lin X, Chen L, Ji L, Zhang W. The Catechol-O-Methyltransferase and Dopamine Transporter Genes Moderated the Impact of Peer Relationships on Adolescent Depressive Symptoms: A Gene-Gene-Environment Study. J Youth Adolesc 2018; 47(11): 2468–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Weber MA, Graack ET, Scholl JL, Renner KJ, Forster GL, Watt MJ. Enhanced dopamine D2 autoreceptor function in the adult prefrontal cortex contributes to dopamine hypoactivity following adolescent social stress. Eur J Neurosci 2018; 48(2): 1833–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Blum K, Modestino EJ, Neary J, et al. Promoting Precision Addiction Management (PAM) to Combat the Global Opioid Crisis. Biomed J Sci Tech Res 2018; 2(2): 1–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Watt MJ, Roberts CL, Scholl JL, et al. Decreased prefrontal cortex dopamine activity following adolescent social defeat in male rats: role of dopamine D2 receptors. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2014; 231(8): 1627–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Shi W, Zhang Y, Zhao G, et al. Dysregulation of Dopaminergic Regulatory Factors TH, Nurr1, and Pitx3 in the Ventral Tegmental Area Associated with Neuronal Injury Induced by Chronic Morphine Dependence. Int J Mol Sci 2019; 20(2): E250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Montagud-Romero S, Nuñez C, Blanco-Gandia MC, et al. Repeated social defeat and the rewarding effects of cocaine in adult and adolescent mice: dopamine transcription factors, proBDNF signaling pathways, and the TrkB receptor in the mesolimbic system. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2017; 234(13): 2063–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Novick AM, Forster GL, Hassell JE, et al. Increased dopamine transporter function as a mechanism for dopamine hypoactivity in the adult infralimbic medial prefrontal cortex following adolescent social stress. Neuropharmacology 2015; 97: 194–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Zhang W, Cao Y, Wang M, Ji L, Chen L, Deater-Deckard K. The Dopamine D2 Receptor Polymorphism (DRD2 TaqIA) Interacts with Maternal Parenting in Predicting Early Adolescent Depressive Symptoms: Evidence of Differential Susceptibility and Age Differences. J Youth Adolesc 2015; 44(7): 1428–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Sinclair D, Purves-Tyson TD, Allen KM, Weickert CS. Impacts of stress and sex hormones on dopamine neurotransmission in the adolescent brain. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2014; 231(8): 1581–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Blum K, Liu Y, Wang W, et al. rsfMRI effects of KB220Z™ on neural pathways in reward circuitry of abstinent genotyped heroin addicts. Postgrad Med 2015; 127(2): 232–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Gold MS, Blum K, Oscar-Berman M, Braverman ER. Low dopamine function in attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder: should genotyping signify early diagnosis in children? Postgrad Med 2014; 126(1): 153–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Salamone JD, Correa M. The mysterious motivational functions of mesolimbic dopamine. Neuron 2012; 76(3): 470–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Stice E, Yokum S, Blum K, Bohon C. Weight gain is associated with reduced striatal response to palatable food. J Neurosci 2010; 30(39): 13105–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Bello NT, Hajnal A. Dopamine and binge eating behaviors. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 2010; 97(1): 25–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Carpenter CL, Wong AM, Li Z, Noble EP, Heber D. Association of dopamine D2 receptor and leptin receptor genes with clinically severe obesity. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2013; 21(9): E467–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Chen R, McIntosh S, Hemby SE, et al. High and low doses of cocaine intake are differentially regulated by dopamine D2 receptors in the ventral tegmental area and the nucleus accumbens. Neurosci Lett 2018; 671: 133–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Hillemacher T, Frieling H, Buchholz V, et al. Alterations in DNA-methylation of the dopamine-receptor 2 gene are associated with abstinence and health care utilization in individuals with a lifetime history of pathologic gambling. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 2015; 63: 30–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Blum K, Baron D, Lott L, et al. In Search of Reward Deficiency Syndrome (RDS)-free Controls: The “Holy Grail” in Genetic Addiction Risk Testing. Curr Psychopharmacol 2020; 9(1): 7–21. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Blum K, Baron D. Opioid Substitution Therapy: Achieving Harm Reduction While Searching for a Prophylactic Solution. Curr Pharm Biotechnol 2019; 20(3): 180–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Blum K, et al. Pro-Dopamine Regulator (KB220) A Fifty Year Sojourn to Combat Reward Deficiency Syndrome (RDS): Evidence Based Bibliography (Annotated). CPQ Neurol Psychol 2018; 1(2)https://www.cientperiodique.com/journal/fulltext/CPQN-P/1/2/13 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Romoli B, Lozada AF, Sandoval IM, et al. Neonatal Nicotine Exposure Primes Midbrain Neurons to a Dopaminergic Phenotype and Increases Adult Drug Consumption. Biol Psychiatry 2019; 86(5): 344–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Dalterio S, Blum K, DeLallo L, Sweeney C, Briggs A, Bartke A. Perinatal exposure to delta 9-THC in mice: altered enkephalin and norepinephrine sensitivity in vas deferens. Subst Alcohol Actions Misuse 1980; 1(5–6): 467–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Abijo T, Blum K, Gondré-Lewis MC. Neuropharmacological and Neurogenetic Correlates of Opioid Use Disorder (OUD) As a Function of Ethnicity: Relevance to Precision Addiction Medicine. Curr Neuropharmacol 2020; 18(7): 578–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]