Abstract

Alcohol consumption has been strongly associated with circadian clock gene expression in mammals. Analysis of clock genes revealed a potential role of Bmal1 in the control of alcohol drinking behavior. However, a causal role of Bmal1 and neural pathways through which it may influence alcohol intake have not yet been established. Here we show that selective ablation of Bmal1 (Cre/loxP system) from medium spiny neurons of the striatum induces sexual dimorphic alterations in alcohol consumption in mice, resulting in augmentation of voluntary alcohol intake in males and repression of intake in females. Per2mRNA expression, quantified by qPCR, decreases in the striatum after the deletion of Bmal1. To address the possibility that the effect of striatal Bmal1 deletion on alcohol intake and preference involves changes in the local expression of Per2, voluntary alcohol intake (two-bottle, free-choice paradigm) was studied in mice with a selective ablation of Per2 from medium spiny neurons of the striatum. Striatal ablation of Per2 increases voluntary alcohol intake in males but has no effect in females. Striatal Bmal1 and Per2 expression thus may contribute to the propensity to consume alcohol in a sex -specific manner in mice.

Subject terms: Risk factors, Addiction, Reward, Circadian regulation

In order to examine the role of the circadian clock driver Brain and Muscle ARNT-Like 1 (Bmal1) in alcohol consumption, de Zavalia et al assess the effects of (Bmal1) deletion in the mouse striatum on alcohol drinking behavior. They show that striatal Bmal1 and downstream effects on Period Circadian Regulator 2 (Per2) play a sex-dependent role on alcohol consumption propensity.

Introduction

Brain and muscle ARNT-like protein 1 (Bmal1) is a circadian clock gene and transcriptional regulator that plays an obligatory role in the generation of circadian rhythms in the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN), the master circadian clock in mammals1. Notably, Bmal1 is widely expressed in the mammalian brain2, and perturbations in Bmal1 expression in distinct regions outside the SCN cause various physiological and behavioral disruptions3–5, including disturbances in sleep architecture6, and in cognitive and mood-related behaviors7–12. Over the past years, association analysis of clock genes revealed a potential role of Bmal1 in the control of alcohol drinking behavior13,14. Kovanen and colleagues found evidence that Bmal1 is linked to alcohol consumption15. Similarly, an association between Bmal1 polymorphisms and an increased risk of alcohol use disorder (AUD) has been described16. However, a causal role of Bmal1 and neural pathways through which it may influence alcohol intake have not yet been established. The striatum, a subcortical part of the forebrain, is the major input site of the basal ganglia, a neuronal structure involved in the control of reward-related processes. Alcohol alters the function of striatal circuits in multiple ways, which may contribute to acute intoxication, alcohol-seeking, dependence and withdrawal17–24. The dorsal striatum is involved in the control of alcohol habit formation and goal-directed alcohol seeking, whereas the ventral striatum has an important role in environmental control of alcohol drinking and relapse25.

Alcohol use, abuse and dependence are sex-dependent. In humans, females report lower alcohol use and dependency than males26–29. This pattern is reversed in rodents; females display higher alcohol intake compared to males30–32. In both humans and rodents, females suffer from more adverse consequences of alcohol use and dependency, spanning from physical health to cognition and mental health26–29. Interestingly, striatal function and morphology is sexual dimorphic, and affected by components of the circadian clock33–39.

Therefore, we hypothesize that circadian clock genes affect ethanol consumption in mice in a sex dependent manner. We examine voluntary alcohol consumption and preference in male and female mice that lack Bmal1 in medium spiny neurons (MSNs) of the striatum exclusively, which constitute approximately 95% of striatal neurons25. Our experiments reveal that Bmal1 in MSNs exerts a sexually dimorphic influence on alcohol drinking behavior – repressing preference and intake in males and promoting high preference and intake in females – which may contribute to sex differences in the propensity to consume alcohol in mice. This mechanism seems to be mediated by Per2 in male mice, whereas is appears to be independent of Per2 in females.

Results

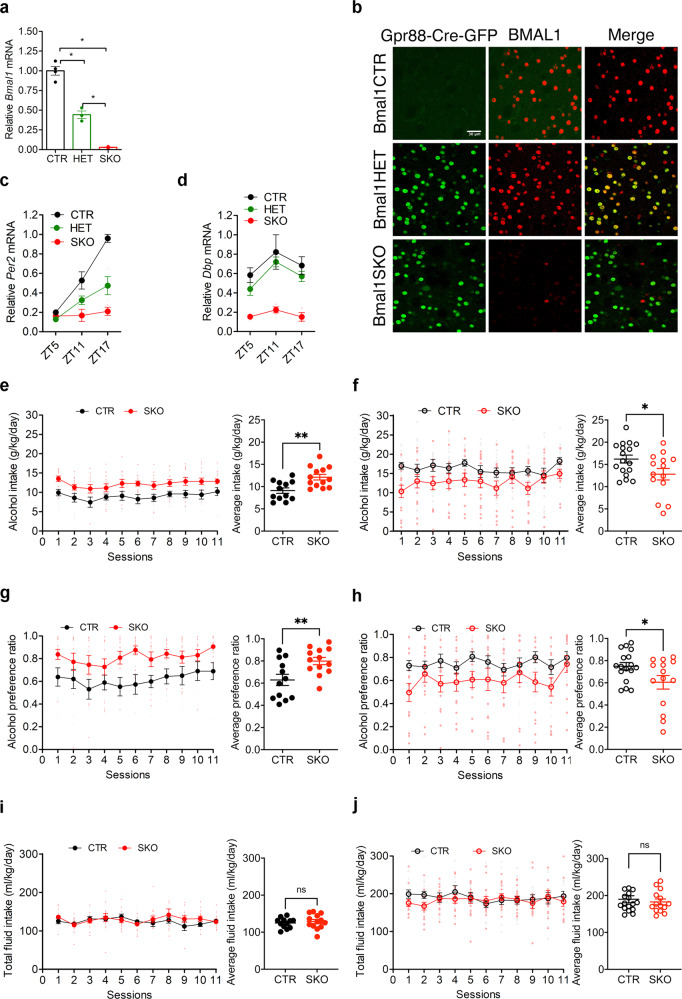

Generation and validation of striatal Bmal1 knockout mice

Conditional knockout mice that lack Bmal1 exclusively in striatal MSNs were created by crossing mice that express floxed alleles of Bmal1 with mice that express Cre recombinase under the control of Gpr88, a striatum specific G-protein coupled receptor. Knockout efficiency and specificity were validated by mRNA and protein expression analysis, confirming the striatum- specific absence of Bmal1 and loss of circadian clock function in the striatum but not in the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN), the master circadian clock. Specifically, quantitative-PCR analysis of striatal tissue revealed a substantial reduction of Bmal1 mRNA levels in homozygote Bmal1 knockout mice (Gpr88Cre/+; Bmal1fl/fl [Bmal1SKO]) and heterozygote knockout mice (Gpr88Cre/+; Bmal1fl/+ [Bmal1HET]) compared to wildtype controls (Gpr88+/+; Bmal1fl/fl, [Bmal1CTR]) (Fig. 1a). Fluorescence immunohistochemistry shows that BMAL1 is expressed in striatal tissue sections from Bmal1CTR and Bmal1HET mice, whereas sections from Bmal1SKO mice lacked BMAL1 immunostaining (Fig. 1b). The reduction of BMAL1 in the striatum was further confirmed by western blotting analysis of striatal tissue at 2 different times across the 24 h day (Supplementary Figs. 1a, b, 3). In addition, we established that the deletion of Bmal1 is restricted to the striatum by showing the presence of BMAL1 immunostaining in the SCN and hippocampus of knockout mice (Supplementary Fig. 1c). To determine if the deletion of Bmal1 disrupted the striatal circadian clock, we studied the expression of the clock gene Per2 and the canonical clock-controlled gene Dbp. In the striatum of Bmal1CTR mice, Per2 mRNA levels peaked at night (Zeitgeber time (ZT) 17, i.e. 5 h after the light goes off). In contrast, in Bmal1SKO mice, striatal levels of Per2 mRNA were significantly downregulated at ZT11 and ZT17, and its rhythm was blunted (Fig. 1c). Similarly, Bmal1 deletion from MSNs induced a significant downregulation of Dbp mRNA in the striatum (Fig. 1d, Supplementary Data 1).

Fig. 1. Alcohol drinking behavior of control and Bmal1 knockout mice.

a Quantitative PCR analysis of Bmal1 mRNA levels measured at ZT1 in dorsal striatal tissue of control, Bmal1 heterozygote and knockout mice. ANOVA, significant genotype effect, F (2, 7) = 113.8, p < 0.0001, Tukey’s post-hoc test, *p < 0.005. b A representative image of BMAL1 immunofluorescence staining at ZT 1 in dorsal striatal tissue of control, Bmal1 heterozygote and knockout mice. BMAL1: red, Gpr88-Cre-GFP: green. Scale bar = 30 µm. c Quantitative PCR analysis of Per2 mRNA levels in dorsal striatal tissue of control, Bmal1 heterozygote and knockout male mice. Two-way ANOVA, significant genotype effect, F (2, 5) = 21.46, p = 0.0035, and time point effect, F (2, 8) = 51.7, p < 0.0001, significant interaction effect, F (4, 8) = 13.97, p = 0.0011. d Quantitative PCR analysis of Dbp mRNA levels in dorsal striatal tissue of control, Bmal1 heterozygote and knockout mice. Two-way ANOVA, significant genotype effect, F (2, 5) = 116.6, p < 0.0001, and time point effect F (2, 8) = 5.236, p < 0.05 effect, Tukey’s test, **p < 0.05. e Daily alcohol consumption (left) and average alcohol consumption (right) of control, and Bmal1 knockout male mice. Two-way repeated measure ANOVA, (RM-ANOVA) significant genotype effect, F (1, 23) = 13.26, p = 0.0014, Unpaired two-tailed t-test, **p < 0.01. f Daily alcohol consumption (left) and average alcohol consumption (right) of control, and Bmal1 knockout female mice. RM-ANOVA, significant genotype effect, F (1, 29) = 5.0, p = 0.033. Unpaired two-tailed t-test, *p < 0.05. g Daily alcohol preference (left) and average alcohol preference (right) of control, and Bmal1 knockout male mice. RM-ANOVA, significant genotype effect, F (1, 23) = 10.73, p = 0.0033. Unpaired two tailed t-test, **p < 0.01. h Daily alcohol preference (left) and average alcohol preference (right) of control, and Bmal1 knockout female mice. RM-ANOVA, significant genotype effect, F (1, 29) =4.708, p = 0.0384. Unpaired two tailed t-test, *p < 0.05. i Daily fluid intake (left) and average fluid intake (right) of control and Bmal1 knockout male mice. RM-ANOVA, no significant effect, F (1, 23) = 0.3737, p = 0.5470. Unpaired two-tailed t-test, NS. j Daily fluid intake (left) and average fluid intake (right) of control and Bmal1 knockout female mice. RM-ANOVA, no significant effect, F (1,29) = 0.3185, p = 0.5769. Unpaired two-tailed t-test, NS. NS = no significant differences. CTR: control, HET: Bmal1 heterozygote, SKO: Bmal1 knockout. ZT: Zeitgeber time. c-j, the values express mean ± S.E.M. a–d, n = 3/genotype. e, g, i, CTR n = 12, SKO n = 13. f, h, j, CTR n = 17, SKO n = 14.

Voluntary alcohol consumption in Bmal1 knockout mice

To study voluntary alcohol consumption, we used a two-bottle, free-choice paradigm. Mice had access to one bottle of 15% ethanol solution in tap water (vl/vl) and one bottle of tap water only, every other day, in alternate left-right position, for a total of 11 sessions. Analysis of variance revealed a significant main effect of genotype on alcohol intake and preference across the 11 test sessions in both males (Fig. 1e, g) and females (Fig. 1f, h). On average, Bmal1SKO males consumed 33% more alcohol and exhibited 36% greater alcohol preference than Bmal1CTR mice over the 11 alcohol test days. Strikingly, contrary to males, Bmal1SKO females consumed 22% less alcohol than Bmal1CTR females (Fig. 1f) and exhibited 15% lower alcohol preference (Fig. 1h, Supplementary Data 1) over the 11 alcohol test days. These results show that Bmal1 in MSNs exerts a sexually dimorphic influence on alcohol drinking behavior in mice, repressing intake and preference in males and promoting them in females. Interestingly, in both males and females, Bmal1HET show no difference in alcohol consumption compared to control animals (Fig. 3a–f and Supplementary Data 3), indicating that one copy of Bmal1 in MSNs is sufficient to maintain the normal level of alcohol consumption. Total fluid intake (Fig. 1i, j) and body weight (Supplementary Fig. 1e–h, Supplementary Data 1) were comparable between genotypes in both sexes, establishing that the changes in alcohol consumption in knockout mice are not the result of changes in body mass or general fluid intake.

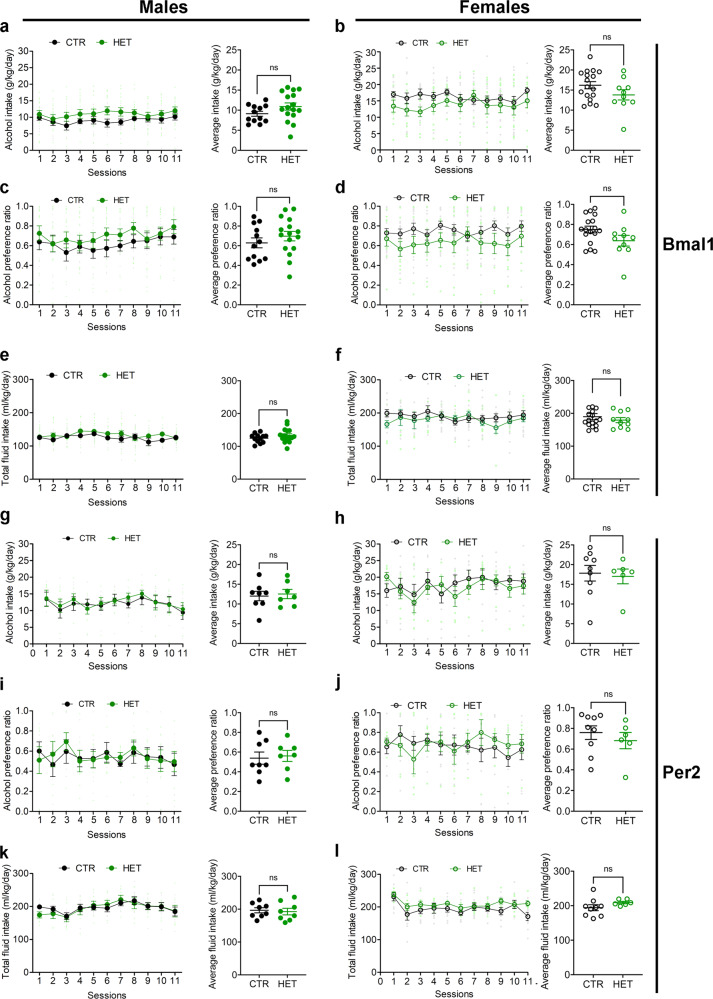

Fig. 3. Alcohol drinking behavior of control, Bmal1, and Per2 heterozygote mice.

a Daily alcohol intake (left) and average alcohol intake (right) of control and Bmal1 heterozygote male mice. Two-way repeated measure ANOVA (RM-ANOVA), no significant effect, F (1, 26) = 2.793, p = 0.1067, Unpaired two-tailed t-test, NS. b Daily alcohol intake (left) and average alcohol intake (right) of control and Bmal1 heterozygote female mice. RM-ANOVA, no significant effect, F (1, 25) = 2.507, p = 0.1259, Unpaired two-tailed t-test, NS. c Daily alcohol preference (left) and average alcohol preference (right) of control and Bmal1 heterozygote male mice. RM-ANOVA, no significant effect, F (1, 26) = 1.326, p = 0.26, Unpaired two-tailed t-test, NS. d Daily alcohol preference (left) and average alcohol preference (right) of control and Bmal1 heterozygote female mice. RM-ANOVA, no significant effect, F (1, 25) = 3.506, p = 0.0729, Unpaired two tailed t-test, NS. e Total fluid intake (left) and average fluid intake (right) of control and Bmal1 heterozygote male mice. RM-ANOVA, no significant effect, F (91, 26) = 1.498, p = 0.2320, Unpaired two-tailed t-test, NS. f Total fluid intake (left) and average fluid intake (right) of control and Bmal1 heterozygote female mice. RM-ANOVA, no significant effect, F (1, 25) = 0.5874, p = 0.4506, Unpaired two-tailed t-test, NS. g Daily alcohol intake (left) and average alcohol intake (right) of control and Per2 heterozygote male mice. RM-ANOVA, no significant effect, F (1, 13) = 0.09317, p = 0.7650. Unpaired two-tailed t-test, NS. h Daily alcohol intake (left) and average alcohol intake (right) of control and Per2 heterozygote female mice. RM-ANOVA, no significant effect, F (1, 13) = 0.08137. p = 0.7799. Unpaired two-tailed t-test, NS. i Daily alcohol preference (left) and average alcohol preference (right) of control and Per2 heterozygote male mice. RM-ANOVA, no significant effect, F (1, 13) = 0.01314, p = 0.9105. Unpaired two-tailed t-test, NS. j Daily alcohol preference (left) and average alcohol preference (right) of control and Pe2 heterozygote female mice. RM-ANOVA, no significant effect, F (1, 13) = 0.04381, p = 0.8375. Unpaired two-tailed t-test, NS. k Total fluid intake (left) and average fluid intake (right) of control and Per2 heterozygote male mice. RM-ANOVA, no significant effect, F (1, 13) = 0.02780, p = 0.8702. Unpaired two-tailed t-test, NS. l Total fluid intake (left) and average fluid intake (right) of control and Per2 heterozygote female mice. RM-ANOVA, no significant effect, F (1, 13) = 1.833, p = 0.1988. Unpaired two tailed t-test, NS. NS = no significant differences. The values express mean ± S.E.M. a–f, CTR: control, HET: Bmal1 heterozygote. a, c, e CTR n = 12, HET n = 16. b, d, f CTR n = 17, HET n = 10. g–l CTR: control, HET: Per2 heterozygote. g, i, k CTR n = 8, HET n = 7. h, j, l CTR n = 9, HET n = 6.

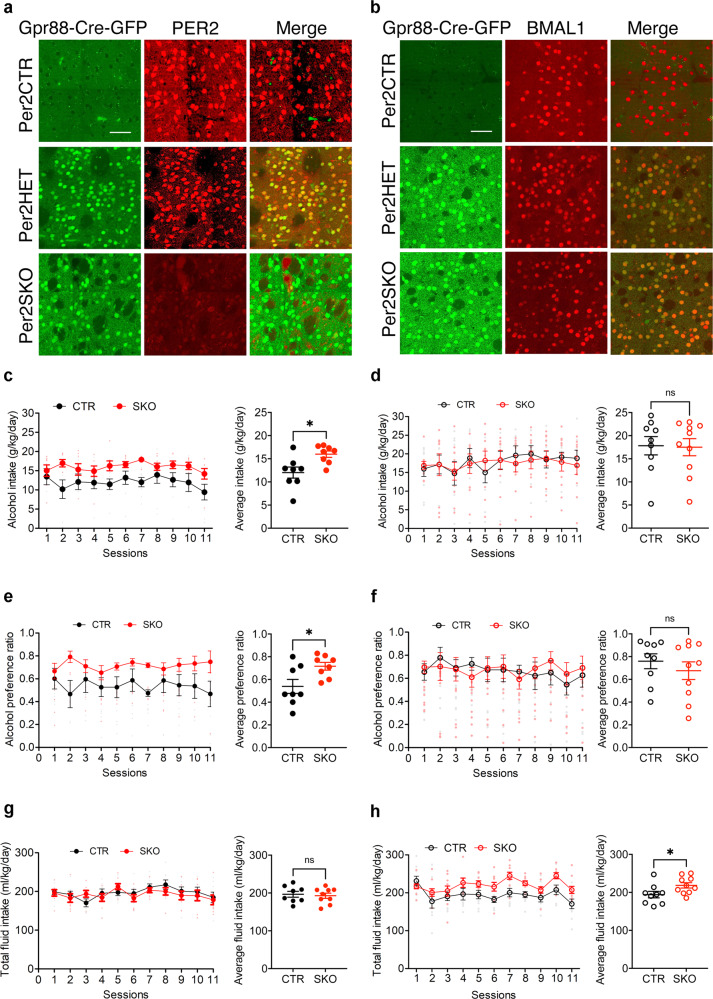

Voluntary alcohol consumption in Per2 knockout mice

Bmal1 plays an obligatory role in the expression of the clock gene Per2 in the striatum, as shown by gene expression analysis (Fig. 1c). Per2 is associated with alcohol consumption in animal models and humans40. Global loss of function of Per2 has been shown to augment alcohol intake and preference in male mice40, raising the possibility that the effect of striatal Bmal1 deletion on alcohol intake and preference involve changes in the local expression of Per2. To study the direct contribution of striatal Per2 expression in alcohol drinking, we generated striatum-specific Per2 knockout male and female mice by crossing animals carrying floxed alleles of Per2 with mice expressing Cre recombinase under the control of the Gpr88 promoter. Immunostaining of brain sections from Per2SKO mice revealed a complete absence of PER2 immunoreactivity in the striatum (Fig. 2a), but not in the cortex (Supplementary Fig. 1d). The deletion of Per2 from the MSNs augmented voluntary alcohol intake and preference in male mice (Fig. 2c, e), thus mimicking the effect of striatal Bmal1 deletion. On average, daily alcohol intake and preference of Per2SKO male mice were 33% higher than control littermates. Importantly, the absence of Per2 expression in the MSNs did not affect Bmal1 expression (Fig. 2b, Supplementary Data 2), indicating that the effect of Per2 deletion on alcohol consumption is independent of Bmal1.

Fig. 2. Alcohol drinking behavior of control and Per2 knockout mice.

a A representative image of PER2 immunofluorescence staining in dorsal striatal tissue of control and Per2 knockout mice. PER2: red, Gpr88-Cre-GFP: green. n = 3/genotype, scale bar = 50 µm. b A representative image of BMAL1 immunofluorescence staining in dorsal striatal tissue of control, and Per2 knockout mice. BMAL1: red, Gpr88-Cre-GFP: green. n = 3/genotype, scale bar = 50 µm. c Daily alcohol consumption (left) and average alcohol consumption (right) of control and Per2 knockout male mice. Two-way repeated measure ANOVA (RM-ANOVA), significant genotype effect, F (1, 14) = 8.332, p = 0.0120. Unpaired two-tailed t-test, *p < 0.05. d Daily alcohol consumption (left) and average alcohol consumption (right) of control and Per2 knockout female mice. RM-ANOVA, no significant effect, F (1, 17) = 0.014, p = 0.9072. Unpaired two-tailed t-test, NS. e Daily alcohol preference (left) and average alcohol preference (right) of control and Per2 knockout male mice. RM-ANOVA, significant genotype effect, F (1, 14) = 6.552, p = 0.0227. Unpaired two-tailed t-test, *p < 0.05. f Daily alcohol preference (left) and average alcohol preference (right) of control and Per2 knockout female mice. RM-ANOVA, no significant effect, F (1, 17) = 0.01779, p = 0.8955. Unpaired two-tailed t-test, NS. g Daily fluid intake (left) and average fluid intake (right) of control and Per2 knockout male mice. RM-ANOVA, no significant effect, F (1, 14) = 0.142, p = 0.7116. Unpaired two-tailed t-test, NS. h Daily fluid intake (left) and average fluid intake (right) of control and Per2 knockout female mice. RM-ANOVA, significant genotype effect, F (1, 17) = 5.665, p = 0.0293. Unpaired two-tailed t-test, *p < 0.05. NS = no significant differences. CTR: control, HET: Per2 heterozygote, SKO: Per2 knockout. c–h The values express mean ± S.E.M. a, b n = 3/genotype. c, e, g, CTR n = 8, SKO n = 8. d, f, h CTR n = 9, SKO n = 10.

In contrast to males, the removal of Per2 from the MSNs did not affect alcohol consumption and preference in females (Fig. 2d, f), revealing a female-specific dissociation between the effect of Bmal1 and Per2 on alcohol intake. These results suggest that the effect of Bmal1 deletion on alcohol behavior could be mediated by Per2 in males. On the contrary, this effect does not rely on Per2 and is directly related to the loss of function of Bmal1 in the striatum in females.

Deletion of one copy of Per2 (Per2HET) had no effect on alcohol intake and preference in males or females, indicating that striatal Per2 is haplosufficient in the control of alcohol intake (Fig. 3g–l, Supplementary Data 3). Finally, similar to our findings for the deletion of Bmal1, no difference in body weight (Supplementary Fig. 1i–l) was found across the 11 sessions. The total liquid consumption was significantly different for the Per2SKO females compared to the controls (Fig. 2h, Supplementary Data 2).

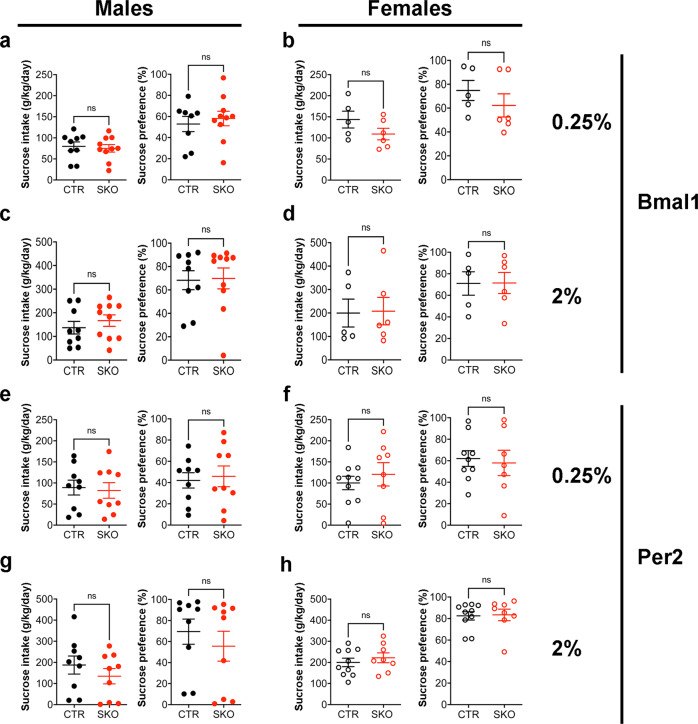

Sucrose consumption in Bmal1 and Per2 knockout mice

Alcohol consumption and preference have been associated with the propensity to consume sweet solutions41. To study whether the sexually dimorphic effects of striatal deletion of Bmal1 or Per2 on alcohol behavior extend to, or may have resulted from, a change in the general sensitivity to palatable taste, we assessed sucrose consumption in Bmal1SKO and Per2SKO mice.

We found that the striatal deletion of Bmal1 or Per2 did not affect voluntary intake of 0.25% or 2.0% sucrose solution, delivered in a two-bottle free-choice paradigm with water for 3 consecutive days, in males (Fig. 4a, c, e, g) or females (Fig. 4b, d, f, h, Supplementary Data 4).

Fig. 4. Drinking behavior of Bmal1 and Per2 knockout mice is independent of changes in the general reward processing.

a Average daily intake (left) and preference (right) of 0.25% sucrose solution of control and Bmal1 knockout male mice. Unpaired two-tailed t-test, NS. b Average daily intake (left) and preference (right) of 0.25% sucrose solution of control and Bmal1 knockout female mice. Unpaired two-tailed t-test, NS. c Average daily intake (left) and preference (right) of 2% sucrose solution of control and Bmal1 knockout male mice. Unpaired two-tailed t-test, NS. d Average daily intake (left) and preference (right) of 2% sucrose solution of control and Bmal1 knockout female mice. Unpaired two-tailed t-test, NS. e Average daily intake (left) and preference (right) of 0.25% sucrose solution of control and Per2 knockout male mice. Unpaired two-tailed t-test, NS. f Average daily intake (left) and preference (right) of 0.25% sucrose solution of control and Per2 knockout female mice. Unpaired two-tailed t-test, NS. g Average daily intake (left) and preference (right) of 2% sucrose solution of control and Per2 knockout male mice. Unpaired two-tailed t-test, NS. h, Average daily intake (left) and preference (right) 2% sucrose solution of control and Per2 knockout female mice. Unpaired two-tailed t-test, NS. NS = no significant differences. a–h, the values express mean ± S.E.M. a–d, CTR: Bmal1 control, SKO: Bmal1 Knockout. a, c, CTR n = 9, SKO n = 9. b, d CTR n = 5, SKO n = 6. e–h CTR: Per2 control, SKO: Per2 knockout. e, g CTR n = 9, SKO n = 9. f, h CTR n = 10, SKO n = 8.

Thus, the effects of striatal deletion of Bmal1 or Per2 from MSNs on alcohol intake and preference appears to be specific and not due to changes in the palatability of alcohol taste.

Circadian rhythms analysis in Bmal1 and Per2 knockout mice

Global or selective deletion of Bmal1 or Per2 in the SCN disrupts circadian behavioral rhythms1,42, and disruption of circadian rhythms can influence alcohol consumption43,44. However, both types of rhythm disruptions comprise systemic alterations of circadian functions and do not allow to draw conclusions on the exact origin of the observed behavioral phenotypes. To ensure that the differences in alcohol consumption observed in striatal Bmal1 and Per2 knockout animals were not due to indirect effects of the conditional knockout on SCN function, we monitored wheel- running behavior in alcohol naïve mice housed individually under different lighting conditions.

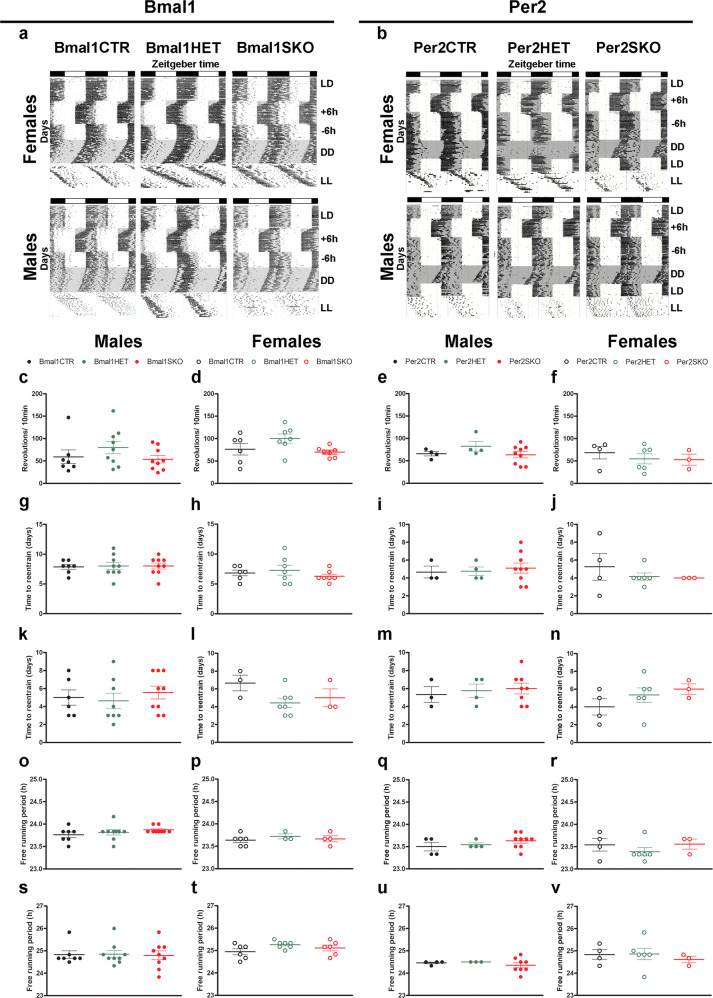

Circadian activity rhythms in Bmal1SKO, Bmal1HET, Per2SKO and Per2HET male and female mice were indistinguishable from those in respective male and female controls (Fig. 5). In particular, striatal deletion of two (SKO) or only one copy (HET) of Bmal1 or Per2 did not affect activity levels and entrainment of daily rhythms of wheel running to a 12:12 h light-dark cycle (Figure 5a–f), adjustments to phase shifts in the light cycle (Fig. 5g–n), and free running in constant conditions (Fig. 5o–v, Supplmentary Data 5). These results show that Bmal1SKO and Per2SKO male and female mice and their respective HET mice have a functional SCN and normal circadian pacemaking. Thus, the sexually dimorphic changes in alcohol consumption in SKO and HET male and female mice are specific to the clock gene manipulation in MSNs of the striatum.

Fig. 5. Conditional ablation of Bmal1 and Per2 does not affect SCN function.

a Representative double-plotted actograms illustrating the daily pattern of running-wheel activity of control, Bmal1 heterozygote and knockout female (top), and male (bottom) mice. b Representative double-plotted actograms illustrating the daily pattern of running-wheel activity of control, Per2 heterozygote and knockout female (top) and male (bottom) mice. The vertical marks indicate periods of activity of at least 10-wheel revolutions per 10 min. Each horizontal line plots 48 h, and sequential days are arranged from top to bottom. The empty and gray shaded areas in each actogram illustrate the light and dark phases, respectively. c–v Circadian analysis of locomotor activity of Bmal1 and Per2 control, heterozygote and knockout male and female mice. One way-ANOVA. No significant differences were observed between the different genotypes in any of the parameters analyzed. c–f Amplitude of the locomotor activity rhythm. g–j, time to entrain to a 6-h phase advance. k–n Time to entrain to a 6-h phase delay. o–r Free running period in constant dark (DD). s-v Free running period in constant light (LL). a, b LD, 12:12 h light dark; +6 h, 6-h phase advance; −6h, 6-h phase delay; DD, constant dark; LL, constant light. Bmal1CTR: control, Bmal1HET: Bmal1 heterozygote, Bmal1SKO: Bmal1 knockout. Per2CTR: control, Per2HET: Per2 heterozygote, Per2SKO: Per2 knockout. Bars on the graphs represent the arithmetic mean ± S.E.M.

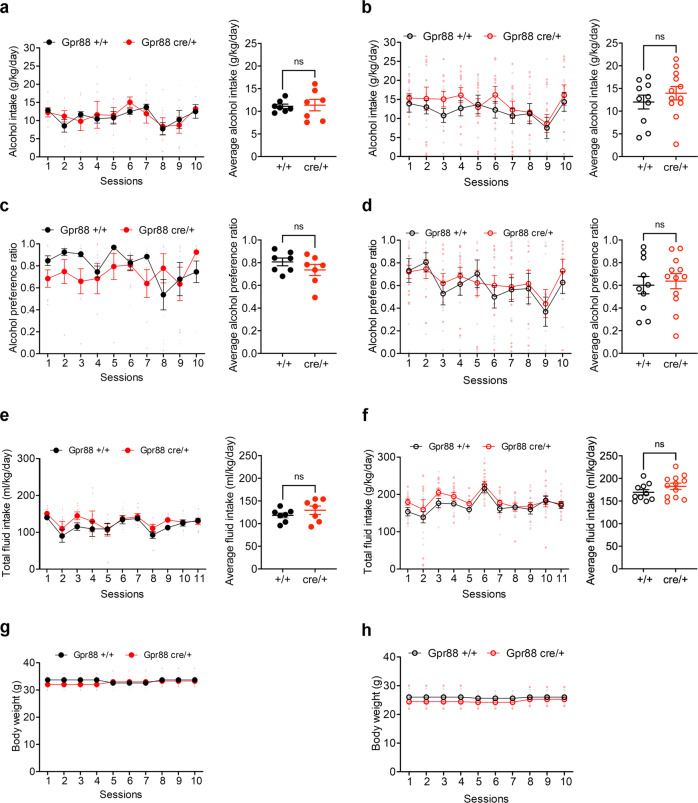

Alcohol consumption in Gpr88 +/cre mice

Bmal1SKO and Per2SKO and the respective HET genotypes have only one functional copy of Gpr88 in MSNs, since one copy is modified to drive Cre and EGFP expression. Complete deletion of Gpr88, has been shown to augment alcohol intake in male mice45, raising the possibility that the sexually dimorphic changes in alcohol consumption seen in striatal Bmal1SKO and Per2SKO were due, at least in part, to a sex difference in a contributory effect of Gpr88 monoallelic expression in MSNs. To study this possibility, we compared alcohol intake and preference between Gpr88+/+ mice and Gpr88Cre/+ mice. Average alcohol intake and preference in Gpr88Cre/+ male and female mice were similar compared to Gpr88 +/+ controls (Fig. 6, Supplementary Data 6), excluding the possibility that the changes in alcohol consumption associated with deletion of striatal Bmal1 or Per2 were due to Gpr88 haploinsufficiency, or expression of Cre-EGFP in Gpr88- bearing cells46.

Fig. 6. Alcohol consumption is not altered in Gpr88 heterozygote mice.

a Daily alcohol intake (left) and average alcohol intake (right) of control and Gpr88 heterozygote male mice. Two-way repeated measure ANOVA (RM-ANOVA), no significant effect, F (1, 12) = 0.03709, p = 0.8505. Unpaired two-tailed t-test, no significance. b Daily alcohol intake (left) and average alcohol intake (right) of control and Gpr88 heterozygote female mice. RM- ANOVA, no significance, F (1, 20) = 0.8286, p = 0.3735. Unpaired two-tailed t-test, no significance. c Daily alcohol preference (left) and average alcohol preference of control and Gpr88 heterozygote male mice. RM-ANOVA, no significance, F (1, 12) = 1.418, p = 0.2567. Unpaired two-tailed t-test, no significance. d Daily alcohol preference (left) and average alcohol preference of control and Gpr88 heterozygote female mice. RM-ANOVA, no significance, F (1, 20) = 0.1233, p = 0.0.7292. Unpaired two-tailed t-test, no significance. e Total fluid intake (left) and average fluid intake (right) of control and Gpr88 heterozygote male mice. RM-ANOVA, no significant effect, F (1, 12) = 1.079, p = 0.3195, Unpaired two-tailed t-test, NS. f Total fluid intake (left) and average fluid intake (right) of control and Gpr88 heterozygote female mice. RM-ANOVA, no significant effect, F (1, 20) = 1.983, p = 0.1744, Unpaired two-tailed t-test, NS. g Daily body weight of control and Gpr88 heterozygote male mice. RM-ANOVA, no significant effect, F (1, 12) = 0.5672, p = 0.4659. h Daily body weight of control and Gpr88 heterozygote female mice. RM-ANOVA, no significant effect, F (1, 20) = 2.905, p = 0.1038. NS = no significant differences. The values express mean ± S.E.M. a, c, e, g, Gpr88+/+, n = 7 and Gpr88Cre/+, n = 7. b, d, f, h Gpr88+/+, n = 10 and Gpr88Cre/+, n = 12.

Sex differences in alcohol behavior are well recognized in rodents, with females generally drinking more alcohol than males33–35. Consistent with this, average daily alcohol intake and preference in female control mice was significantly greater than in males (Supplementary Fig. 2a, d). In contrast, mean alcohol preference in Bmal1SKO male mice was significantly higher than Bmal1SKO females, and no difference in mean alcohol intake was observed (Supplementary Fig. 2c, f). Similarly, average alcohol intake and preference were greater in Per2CTR females than Per2CTR males (Supplementary Fig. 2g, j), whereas no significant differences in mean alcohol preference and intake were noted between Per2SKO males and females (Supplementary Fig. 2i, l). These results show that selective deletion of Bmal1 from MSNs eliminates sex differences in alcohol intake and preference by augmenting consumption and preference in males and suppressing the heightened intake and preference in females. Likewise, striatal deletion of Per2 eliminates sex differences in alcohol consumption, although the effect is attributed primarily to augmentation of intake and preference in Per2SKO males.

Discussion

Our work reveals a novel role of Bmal1 in striatal control of alcohol consumption. The influence of Bmal1 is sexually dimorphic, associated with repression of alcohol consumption in male mice, potentially mediated by Per2, and enhancement of alcohol consumption in females via a mechanism independent of Per2. Both clock genes are associated with the regulation of alcohol intake in humans or animal models, but the exact mechanism of Bmal1- and Per2-dependent changes in alcohol consumption remains elusive. An increasing body of evidence suggest that alterations in glutamatergic signaling in the brain may contribute to the observed phenotypes47–49.

Spanagel and colleagues observed elevated extracellular levels of glutamate due to an attenuated expression of transporter Eaat1 in Per2Brdm1 mutant mice showing increased alcohol consumption40.

Even though this mechanism is unlikely the cause for the phenotype observed in our study50, it gives rise to the assumption that Bmal1 and Per2 affect striatal glutamatergic neurotransmission in a clock gene-specific and sex-dependent manner, conceivably by the neuromodulatory effects of gonadal hormones and/or dopamine. The expression of estrogen receptors has been shown to be clock controlled. Cai and colleagues demonstrated that the CLOCK-BMAL1 dimer binds to an E-box element in the estrogen receptor β (ERβ) promoter. The authors also showed that daily oscillations of ERβ expression, in both lung and skeletal muscle of WT mice, are abolished in BMAL1 knockout mice, indicating that ERβ is a direct target of the circadian clock51, which may contribute to the sex- and clock gene-dependent effects on alcohol consumption in our mouse models. Interestingly, membrane-associated estrogen receptors activate metabotropic glutamate receptor signaling, thereby evoking sex-specific bidirectional responses via cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB) phosphorylation or dephosphorylation, respectively52. Even though alcohol consumption in mice appears to depend on phosphorylated CREB levels in the NAcc53, it needs to be established in future studies whether an altered interaction of sex-hormone and glutamate signaling is directly connected to the observed alcohol drinking phenotypes in striatal clock gene knockout mice.

Alternatively, dopaminergic modulation of the glutamatergic neurotransmission may contribute to the observed differences in alcohol consumption in our mouse model54. It is conceivable that sex- specific factors may also play a role in the regulation of these processes, given that differences between males and females in striatal dopaminergic signaling are well established55,56 and that dopamine receptor expression varies during the different stages of the estrous cycle. Furthermore, clock-dependent alterations in dopamine levels may contribute to the observed phenotypes. The expression of the monoamine oxidase A (MAOA), a key enzyme in dopamine degradation, is clock controlled57–59. Hampp and colleagues found reduced expression and activity of MAOA in the mesolimbic dopaminergic system, and increased levels of dopamine and altered neuronal activity in the striatum of Per2 mutant mice57. Intriguingly, circadian clock genes and components of the dopamine signaling pathway in the striatum influence each other, adding to the complexity of the system. Treatment with DRD1 and DRD2 agonist evoked diverse expression of circadian clock genes in striatal neurons60. Because PER2 expression in MSNs is controlled by the DRD2 receptor61, it is tempting to speculate that the observed clock gene-dependent variations in alcohol consumption in male and female mice may partially be explained by a cell-type specific mechanism. This is emphasized by a recent study revealing opposing roles of DRD1 and DRD2 MSNs in alcohol consumption by a selective activation of glutamatergic or GABAergic neurotransmission, respectively62. The exact role of circadian clock genes in a sex-, cell type- and region-specific neurotransmission in MSNs, and their impact on ethanol consumption, however, needs to be addressed in the future.

Methods

Animals and genotyping

Conditional knockout mice lacking BMAL1 or PER2 protein in the striatum were generated by two genetic crosses. In a first cross, Gpr88(Cre/+) male mice (B6.129S4- Gpr88tm1.1(cre/GFP)Rpa/J; stock number 022510; Jackson Laboratory) were bred with Bmal1(fl/fl) (B6.129S4(Cg)-Arntltm1Weit/J; stock number 007668; Jackson Laboratory) or Per2(fl/fl) (B6.129-Per2tm1.2Ual/Biat, strain ID: EM10599, European Mouse Mutant Archive) female mice to generate respective heterozygote F1 progeny ([Gpr88Cre/+; Bmal1fl/+] or [Gpr88Cre/+; Per2fl/+]). In a second step, F1 males were crossed with Bmal1(fl/fl) or Per2(fl/fl) females to generate desired experimental and control animals. All floxed and Cre-expressing transgenic mouse lines have been backcrossed onto a C57BL/6 J background for at least 6 generations. Genomic DNA was isolated from tail biopsies63, and genotyping was performed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using the OneTaq® Hot Start 2X Master Mix (M0484, New England Biolabs Inc., Ipswich, MA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The specific primers for genotyping were: Cre: Fwd-5′-TTTTCACCTCCCTCCCTTCT-3′; Rev-5′- GCCCACGATTCTTCTTCCTC-3′, yielding a 255 bp product for wild type or a 180 bp product for mutant mice; Bmal1: Fwd-5′-CTGGAAGTAACTTTATCAAACTG-3′, Rev-5′- CTGACCAACTTGCTAACAATTA-3′, yielding a 327 bp product for wild type or a 431 bp product for mutant animals; Per2: Fwd-5′-CTGTGTCCCTGGTTTCTG-3′, Rev-5′-GCAGGGCAGTTTCATCAAGG- 3′, yielding a 468 bp product for wild type or a 596 bp product for mice carrying the transgene.

Mice were group-housed (2–4 individuals) under a 12:12 h light-dark cycle (08:00 am to 08:00 pm) with controlled temperature (22 ± 2 °C) and humidity (40–60% relative humidity), and had access to water and standard rodent chow (5057, Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA, USA) ad libitum. Conditional Bmal1 and Per2 knockout mice (Gpr88Cre/+; Bmal1fl/fl [Bmal1SKO], Gpr88Cre/+; Per2fl/fl [Per2SKO]), littermate heterozygote (Gpr88Cre/+; Bmal1fl/+ [Bmal1HET], Gpr88Cre/+; Per2fl/+ [Per2HET]) and wild type control animals (Gpr88+/+; Bmal1fl/fl [Bmal1CTR], Gpr88+/+; Per2fl/fl [Per2CTR]) of both sexes as well as Gpr88Cre/+ and corresponding control male and female mice were used for experiments with an age of 12–18 weeks. All animal experimental and animal care procedures in this report were conducted in accordance with the guidelines set forth by the Canadian Council of Animal Care and by the Animal Care Committee of Concordia University.

Quantitative PCR

Brains were isolated and flash-frozen from 11 to 13-week-old female Bmal1SKO, HET and CTL mice at ZT5, ZT11, or ZT17 (5, 11 and 17 h after lights turned on). 100 μm coronal section were obtained using a Microm HM 505 E Cryostat (Microm International, Walldorf, Germany) to collect brain tissue. RNA was extracted from tissue punches of the dorsal striatum (DS) and nucleus accumbens (NAcc) using the RNeasy Lipid Tissue Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and converted into cDNA by the iScript™ cDNA Synthesis Kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. qPCR was performed using the following primer pairs: mBmal1: Fwd-5′-GCAGTGCCACTGACTACCAAGA-3′, Rev-5′-TCCTGGACATTGCATTGCAT-3′; mPer2: Fwd-5′-TGATCGAGACGCCTGTGCTCG-3′, Rev-5′-CTCCACGGGTTGATGAAGCTG-3′; mDbp: Fwd-5′-AAGAAGGCAAGGAAAGTCCAG-3′, Rev-5′-ACCTCTTGGCTGCTTCATTG-3′; mGapdh: Fwd- 5′-AGGTCGGTGTGAACGGATTTG-3′, Rev-5′-TGTAGACCATGTAGTTGAGGTC-3′. EvaGreen based amplification detection (EVOlution master mix, MBI-E250, Montreal Biotech, Canada) was performed using an Eco™ real-time PCR system (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). Relative expression of Bmal1, Per2 and Dbp in relation to Gapdh was calculated based on the “delta delta Ct” (ΔΔCt) method64 and normalized to the highest expression value across genotypes and time points for each gene.

Western blot analysis

12–15 weeks old mice were adapted for 10 d to a 12:12 h light-dark cycle and sacrificed either 2 h (ZT2) or 14 h (ZT14) after lights turned on. Brains were isolated and flash-frozen in isopentane. A total of 200 μm coronal sections were cut on a cryostat (Microm HM 505 E Cryostat, Microm International, Walldorf, Germany). The striatal tissue was excised using punches and frozen on dry ice. Tissue was then homogenized in 150 μl of lysis buffer [1 M Tris-HCl pH 6.8, 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 0.1 ml phosphatase inhibitor cocktail 2 (Sigma, # P5726, Burlington, MA, USA), 0.1 ml phosphatase inhibitor cocktail 3 (Millipore Sigma, P0044, Burlington, MA, USA), 1 × protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche, Basel, Switzerland)]. Protein extracts (40 μg/lane) were electrophoresed into a 10% SDS-PAGE gel and then transblotted onto a nitrocellulose membrane (Bio-Rad, # 1620112, Hercules, CA, USA). Membranes were blocked in 5% Milk TBST buffer (skim milk powder) and then incubated (overnight, 4 °C) in TBST (with 5% skim milk powder) with the anti-Bmal1 (1:1000 dilution) antibody (Novus Biologicals, # NB100-2288, Littleton, CO, USA). The same antibody was used for immunolabeling analysis. Next, the membrane was incubated in TBST (with 5% milk) with a goat anti-rabbit IgG horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antibodies (1:200 dilution; Millipore Sigma, # AP132P, Burlington, MA, USA). The signal was visualized using the Western Lighting Chemiluminescence light-emitting system (PerkinElmer Life Sciences, Waltham, MA, USA). Between each antibody treatment, membranes were washed a minimum of three times (10 min per wash) in TBST.

Tissue preparation for Immunohistochemistry

12–15 weeks old mice were transcardially perfused by cold saline (0.9% NaCl), followed by cold paraformaldehyde solution (4% in a 0.1 M phosphate buffer, pH 7.3). Brains were extracted and stored overnight in 4% paraformaldehyde solution at 4 °C. Coronal sections were collected using a Leica vibratome, sliced at a thickness of 50 μm (immunohistochemistry) or 30 μm (immunofluorescence) and then stored at −20 °C in Watson’s cryoprotectant65 until further use.

Immunohistochemistry

Free-floating sections were rinsed once for 10 min in phosphate buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4), followed by 3 × 10 min rinses in 0.3% Triton-X in Trizma-buffered saline solution (TBST: 0.3% Triton, 50 mM Trizma buffer, 0.9% saline). Immunohistochemistry for BMAL1 was performed using an affinity-purified rabbit polyclonal antibody, raised against BMAL1 (1:10000 Novus Biologicals # NB100-2288, Littleton, CO, USA). Brain sections were incubated (40 h, 4 °C) in a primary solution with Bmal1 polyclonal rabbit antibody, 2% normal goat serum, 5% milk buffer in TBST. The sections were then incubated in a secondary solution, composed of biotinylated anti-rabbit IgG, raised in goat (1:200, Vector Laboratories, Burlington, ON, Canada). Lastly, the sections were incubated in a tertiary Avidin-Biotin-Peroxidase solution (Vectastain Elite ABC Kit, Vector Laboratories, Burlington, ON, Canada). All sections were rinsed in a 0.5% 3,3- diaminobenzidine (DAB) solution. Immunoreactive (IR) cells were stained using a 0.5% DAB, 0.01% H2O2 and 8% NiCl2 solution. Stained sections were mounted onto gel-coated slides, dehydrated in a series of alcohols and Citrisolv (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA, USA), covered by Permount media (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA, USA), and coverslipped. The sections were examined under a light microscope (Leica, DMR) and identified using Paxinos mouse brain atlas66.

Images of the SCN, striatum, and hippocampus were captured using a Sony XC-77 video camera, Scion LG-3 frame grabber (Scion Corporation, Frederick, MD, USA), and Image J67.

Immunofluorescence

Free-floating sections were rinsed once for 10 min in phosphate buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4), followed by 3 × 10 min rinses in 0.3% Triton-X in PBS (PBST). Tissue was pre-blocked for 1 h at room temperature with gentle agitation in a solution of PBST containing 3% skim milk powder and 6% normal donkey serum (NDS) then directly transferred to the primary antibody incubation. The tissue was incubated for 48 h with the primary antibody at 4 °C with gentle agitation, rinsed 3 × 10 min in PBST, then incubated with the secondary antibody for 1 h at room temperature with gentle agitation. Antibodies were diluted in a solution of 0.3% PBST with 3% skim milk powder and 2% NDS. The following antibodies and dilutions were used: PER2 rabbit polyclonal (1:500, Novus Biologicals, # NB100-125, Littleton, CO, USA), BMAL1 rabbit polyclonal (1:500, Novus Biologicals # NB100-2288, Littleton, CO, USA), anti-rabbit secondary Alexa-647 (1:500, Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Once all incubations were complete, the tissue was rinsed 3 × 10 min in PBST and 10 min in PBS before being mounted onto slides, allowed to air dry and coverslipped with VECTASHIELD® Antifade Mounting Media (Vector Laboratories, Inc., Burlingame, CA, USA). Slides were left to cure overnight in the dark, sealed with clear nail polish and imaged over the next 5 days. Slides were stored in a slide box at 4 °C. Fluorescent images were captured using the 60 × objective on an Olympus FV10i automated confocal laser scanning microscope at the Centre for Microscopy and Cell Imaging, Concordia University, Montreal, Canada. Brain regions of interest were determined using Paxinos mouse brain atlas66. All confocal parameters (pinhole, contrast, brightness, etc.) were held constant across all data sets from the same experiment.

Two-bottle choice- intermittent access

12–18 weeks old male and female mice (n = 6–17) were separated from group housing one week prior to the beginning of the experiment and single-housed under a 12:12 h light-dark cycle. Oral alcohol intake was determined using 24-h intermittent access to alcohol in a two-bottle choice drinking paradigm. Every other day, at ZT4 (4 h after lights were on), they were given 24 h of concurrent access to one bottle containing 15% ethanol (v/v) in tap water and one bottle containing tap water for 11 sessions of alcohol access. The bottles were weighed every day before and after giving them to the mice. The mice were weighed at the beginning and once a week during the experiment. The position (left or right) of each solution was alternated between sessions as a control for side preference. The possible loss of solutions due to the handling of the bottles, was controlled by weighing bottles in empty cages.

Sucrose consumption

12–18 weeks old male and female mice (n = 5–10) were single-housed under a 12:12 h light-dark cycle. Every day, at ZT4, they were given free access to one bottle containing 0.25% sucrose in tap water (m/v) and 1 bottle containing tap water, in alternate left-right position.

Sucrose solution was offered for 3 consecutive days. The amount of fluid intake was recorded every day before and after giving them to the mice. One week later, the same procedure was performed with 2% sucrose solution. The bottles were weighed every day and the mice were weighed at the beginning of the experiment.

Locomotor activity rhythms

12–15 weeks old male and female mice were housed individually in cages equipped with a running wheel with ad libitum access to food and water. Each cage was kept in a temperature-controlled, soundproof, ventilated isolation chamber and with computer-controlled light sources. Main light source was adjusted such that approximately 100–300 lux of light was equally distributed in the chamber. Mice were kept under a 12:12 h light-dark (LD) schedule, and thereafter exposed to 6 h phase advance (+6 h), followed by a 6 h phase delay (−6 h). After that, mice were transferred into constant darkness (DD) followed by exposure to constant light (LL). Mice were kept for 21–40 days under the respective light regimen. Wheel rotation was recorded using the VitalView program (Mini Mitter, Starr Life Sciences Corp., Oakmont, PA, USA) and double-plotted actograms were prepared using the Actiview software (Mini Mitter, Starr Life Sciences Corp., Oakmont, PA, USA). Microsoft Excel and ClockLab 6 (Actimetrics, Wilmette, IL, USA) were used to analyze locomotor activity patterns. Amplitude was analyzed from summed activity counts recorded over 10 min intervals over a period of 7–10 days. Time to re-entrain to 6-h phase shifts was determined for activity onset and offset individually. The criterion point was a stable alignment of the onset and offset to the shifted light:dark regimen, and the difference between the day at the shift, and the first day of the re-entrained activity phase was calculated. The ActogramJ plugin68 of the Fiji software package69 was used to determine the free-running period in constant darkness and constant light.

Statistics and reproducibility

Statistical analysis was conducted using the GraphPad Prism 8 software package (GraphPad software LLC, San Diego, CA, USA). Unpaired two-tailed t test and ANOVAs with or without repeated measures have been used to compare differences between groups. Significant main effects and interactions of the ANOVAs were further investigated by the appropriate post-hoc test. The level of statistical significance was set at P < 0.05. Exact P values and further details are given in the text.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (S.A). All microscopy was performed at the Concordia Centre for Microscopy and Cellular Imaging at Concordia University, Montreal (special thanks to Dr. Chris Law). Instrumentation for quantitative PCR was provided by the Centre for Structural and Functional Genomics at Concordia University, Montreal (special thanks to Dr. Marc Champagne)

Author contributions

S.A. and N.Z. conceived and designed the study; N.Z., P.S., S.F., J.G., G.P. performed the experiments; S.A., K.S. N.Z. analyzed and Interpreted the data, and wrote the manuscript; S.A. and N.Z. Supervision, N.Z. Project Administration.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Peer review information Communications Biology thanks Olga Barca and the other, anonymous, reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors:Simona Chera and Karli Montague-Cardoso. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Nuria de Zavalia, Email: nuria.dezavalia@concordia.ca.

Shimon Amir, Email: shimon.amir@concordia.ca.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s42003-021-02715-9.

References

- 1.Bunger MK, et al. Mop3 is an essential component of the master circadian pacemaker in mammals. Cell. 2000;103:1009–1017. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)00205-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Frederick A, Goldsmith J, de Zavalia N, Amir S. Mapping the co-localization of the circadian proteins PER2 and BMAL1 with enkephalin and substance P throughout the rodent forebrain. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0176279. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0176279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McDearmon EL, et al. Dissecting the functions of the mammalian clock protein BMAL1 by tissue-specific rescue in mice. Science. 2006;314:1304–1308. doi: 10.1126/science.1132430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hatanaka F, et al. Genome-wide profiling of the core clock protein BMAL1 targets reveals a strict relationship with metabolism. Mol. Cell Biol. 2010;30:5636–5648. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00781-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alvarez JD, et al. The circadian clock protein BMAL1 is necessary for fertility and proper testosterone production in mice. J. Biol. Rhythms. 2008;23:26–36. doi: 10.1177/0748730407311254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khapre RV, Kondratova AA, Susova O, Kondratov RV. Circadian clock protein BMAL1 regulates cellular senescence in vivo. Cell Cycle. 2011;10:4162–4169. doi: 10.4161/cc.10.23.18381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yu X, et al. Circadian factor BMAL1 in histaminergic neurons regulates sleep architecture. Curr. Biol. 2014;24:2838–2844. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2014.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haque SN, Booreddy SR, Welsh DK. Effects of BMAL1 manipulation on the brain’s master circadian clock and behavior. Yale J. Biol. Med. 2019;92:251–258. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Snider KH, et al. Modulation of learning and memory by the targeted deletion of the circadian clock gene Bmal1 in forebrain circuits. Behav. Brain Res. 2016;308:222–235. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2016.04.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kondratova AA, Dubrovsky YV, Antoch MP, Kondratov RV. Circadian clock proteins control adaptation to novel environment and memory formation. Aging (Albany NY) 2010;2:285–297. doi: 10.18632/aging.100142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wardlaw SM, Phan TX, Saraf A, Chen X, Storm DR. Genetic disruption of the core circadian clock impairs hippocampus-dependent memory. Learn Mem. 2014;21:417–423. doi: 10.1101/lm.035451.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Snider KH, Obrietan K. Modulation of learning and memory by the genetic disruption of circadian oscillator populations. Physiol. Behav. 2018;194:387–393. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2018.06.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Valenzuela FJ, et al. Evidences of polymorphism associated with circadian system and risk of pathologies: a review of the literature. Int J. Endocrinol. 2016;2016:2746909. doi: 10.1155/2016/2746909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Partonen T. Clock genes in human alcohol abuse and comorbid conditions. Alcohol. 2015;49:359–365. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2014.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kovanen L, et al. Circadian clock gene polymorphisms in alcohol use disorders and alcohol consumption. Alcohol Alcohol. (Oxf., Oxfs.) 2010;45:303–311. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agq035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Banach E, et al. Clock genes polymorphisms in male bipolar patients with comorbid alcohol abuse. J. Affect. Disord. 2018;241:142–146. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2018.07.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vanderlinden LA, Saba LM, Bennett B, Hoffman PL, Tabakoff B. Influence of sex on genetic regulation of “drinking in the dark” alcohol consumption. Mamm. Genome. 2015;26:43–56. doi: 10.1007/s00335-014-9553-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leggio GM, et al. Dopaminergic-GABAergic interplay and alcohol binge drinking. Pharm. Res. 2019;141:384–391. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2019.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hong SI, Kang S, Chen JF, Choi DS. Indirect medium spiny neurons in the dorsomedial striatum regulate ethanol-containing conditioned reward seeking. J. Neurosci. 2019;39:7206–7217. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0876-19.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kemppainen H, Raivio N, Kiianmaa K. Role for ventral pallidal GABAergic mechanisms in the regulation of ethanol self-administration. Psychopharmacol. (Berl.) 2012;223:211–221. doi: 10.1007/s00213-012-2709-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ji X, et al. Dopamine receptors differentially control binge alcohol drinking-mediated synaptic plasticity of the core nucleus accumbens direct and indirect pathways. J. Neurosci. 2017;37:5463–5474. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3845-16.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhou FC, et al. Chronic alcohol drinking alters neuronal dendritic spines in the brain reward center nucleus accumbens. Brain Res. 2007;1134:148–161. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.11.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lu J, et al. Alcohol intake enhances glutamatergic transmission from D2 receptor expressing afferents onto D1 receptor-expressing medium spiny neurons in the dorsomedial striatum. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2019;44:1123–1131. doi: 10.1038/s41386-019-0332-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Clarke R, Adermark L. Dopaminergic regulation of striatal interneurons in reward and addiction: focus on alcohol. Neural Plast. 2015;2015:814567. doi: 10.1155/2015/814567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen G, et al. Striatal involvement in human alcoholism and alcohol consumption, and withdrawal in animal models. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2011;35:1739–1748. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01520.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ceylan-Isik AF, McBride SM, Ren J. Sex difference in alcoholism: who is at a greater risk for development of alcoholic complication? Life Sci. 2010;87:133–138. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2010.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wilsnack RW, et al. Gender and alcohol consumption: patterns from the multinational GENACIS project. Addiction. 2009;104:1487–1500. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02696.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Becker JB, Koob GF. Sex differences in animal models: focus on addiction. Pharm. Rev. 2016;68:242–263. doi: 10.1124/pr.115.011163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Flores-Bonilla A, Richardson HN. Sex differences in the neurobiology of alcohol use disorder. Alcohol Res. 2020;40:04. doi: 10.35946/arcr.v40.3.04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sneddon EA, White RD, Radke AK. Sex differences in binge-like and aversion resistant alcohol drinking in C57BL/6 J mice. Alcohol Clin. Exp. Res. 2019;43:243–249. doi: 10.1111/acer.13923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.de la Torre ML, Escarabajal MD, Aguero A. Sex differences in adult Wistar rats in the voluntary consumption of ethanol after pre-exposure to ethanol-induced flavor avoidance learning. Pharm. Biochem. Behav. 2015;137:7–15. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2015.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lancaster FE. Gender differences in animal studies. Implications for the study of human alcoholism. Recent Dev. Alcohol. 1995;12:209–215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Segarra AC, et al. Estradiol: a key biological substrate mediating the response to cocaine in female rats. Hormones Behav. 2010;58:33–43. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2009.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ferrario CR, et al. Neural and behavioral plasticity associated with the transition from controlled to escalated cocaine use. Biol. Psychiatry. 2005;58:751–759. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.04.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wissman AM, May RM, Woolley CS. Ultrastructural analysis of sex differences in nucleus accumbens synaptic connectivity. Brain, Struct., Funct. 2012;217:181–190. doi: 10.1007/s00429-011-0353-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Forlano PM, Woolley CS. Quantitative analysis of pre- and postsynaptic sex differences in the nucleus accumbens. J. Comp. Neurol. 2010;518:1330–1348. doi: 10.1002/cne.22233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wissman AM, McCollum AF, Huang GZ, Nikrodhanond AA, Woolley CS. Sex differences and effects of cocaine on excitatory synapses in the nucleus accumbens. Neuropharmacology. 2011;61:217–227. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Strong CE, et al. Locomotor sensitization to intermittent ketamine administration is associated with nucleus accumbens plasticity in male and female rats. Neuropharmacology. 2017;121:195–203. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2017.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ozburn AR, et al. Direct regulation of diurnal Drd3 expression and cocaine reward by NPAS2. Biol. Psychiatry. 2015;77:425–433. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2014.07.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Spanagel R, et al. The clock gene Per2 influences the glutamatergic system and Modulates alcohol consumption. Nat. Med. 2005;11:35–42. doi: 10.1038/nm1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kampov-Polevoy AB, Garbutt JC, Janowsky DS. Association between preference for sweets and excessive alcohol intake: a review of animal and human studies. Alcohol Alcohol. 1999;34:386–395. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/34.3.386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gavrila AM, et al. Double-stranded RNA-mediated suppression of Period2 expression in the suprachiasmatic nucleus disrupts circadian locomotor activity in rats. Neuroscience. 2008;154:409–414. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.04.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gamsby JJ, Gulick D. Chronic shifts in the length and phase of the light cycle increase intermittent alcohol drinking in C57BL/6 J mice. Front Behav. Neurosci. 2015;9:9. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2015.00009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rosenwasser AM, Fixaris MC. Chronobiology of alcohol: studies in C57BL/6 J and DBA/2 J inbred mice. Physiol. Behav. 2013;110-111:140–147. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2013.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ben Hamida S, et al. Increased alcohol seeking in mice lacking Gpr88 involves dysfunctional mesocorticolimbic networks. Biol. Psychiatry. 2018;84:202–212. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2018.01.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ando H, et al. Associations of metabolic parameters and ethanol consumption with messenger RNA expression of clock genes in healthy men. Chronobiol. Int. 2010;27:194–203. doi: 10.3109/07420520903398617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tsai G, Coyle JT. The role of glutamatergic neurotransmission in the pathophysiology of alcoholism. Annu Rev. Med. 1998;49:173–184. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.49.1.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pulvirenti L, Diana M. Drug dependence as a disorder of neural plasticity: focus on dopamine and glutamate. Rev. Neurosci. 2001;12:141–158. doi: 10.1515/REVNEURO.2001.12.2.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Siggins GR, et al. Glutamatergic transmission in opiate and alcohol dependence. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 2003;1003:196–211. doi: 10.1196/annals.1300.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rothstein JD, et al. Localization of neuronal and glial glutamate transporters. Neuron. 1994;13:713–725. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90038-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cai W, et al. Expression levels of estrogen receptor beta are modulated by components of the molecular clock. Mol. Cell Biol. 2008;28:784–793. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00233-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Boulware MI, et al. Estradiol activates group i and ii metabotropic glutamate receptor signaling, leading to opposing influences on camp response element-binding protein. J. Neurosci. 2005;25:5066–5078. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1427-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pandey SC, Roy A, Zhang H, Xu T. Partial deletion of the cAMP response element-binding protein gene promotes alcohol-drinking behaviors. J. Neurosci. 2004;24:5022–5030. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5557-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gardoni F, Bellone C. Modulation of the glutamatergic transmission by Dopamine: a focus on Parkinson, Huntington and Addiction diseases. Front Cell Neurosci. 2005;9:25. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2015.00025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Becker JB. Direct effect of 17 β-estradiol on striatum: sex differences in dopamine release. Synapse. 1990;5:157–164. doi: 10.1002/syn.890050211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Xiao L, Becker JB. Effects of estrogen agonists on amphetamine-stimulated striatal dopamine release. Synapse. 1998;29:379–391. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2396(199808)29:4<379::AID-SYN10>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hampp G, et al. Regulation of monoamine oxidase A by circadian clock components implies clock influence on mood. Curr. Biol. 2008;18:678–683. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yoon SO, Chikaraishi DM. Tissue-specific transcription of the rat tyrosine hydroxylase gene requires synergy between an AP-1 motif and an overlapping E box-containing dyad. Neuron. 1992;9:55–67. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90220-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nakashima A, Ota A, Sabban EL. Interactions between Egr1 and AP1 factors in regulation of tyrosine hydroxylase transcription. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 2003;112:61–69. doi: 10.1016/S0169-328X(03)00047-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Imbesi M, et al. Dopamine receptor-mediated regulation of neuronal “clock” gene expression. Neuroscience. 2009;158:537–544. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.10.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hood S, et al. Endogenous dopamine regulates the rhythm of expression of the clock protein PER2 in the rat dorsal striatum via daily activation of D2 dopamine receptors. J. Neurosci. 2010;30:14046–14058. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2128-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cheng Y, et al. Distinct synaptic strengthening of the striatal direct and indirect pathways drives alcohol consumption. Biol. Psychiatry. 2017;81:918–929. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2016.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Truett GE, et al. Preparation of PCR-quality mouse genomic DNA with hot sodium hydroxide and tris (HotSHOT) Biotechniques. 2000;29:52–54. doi: 10.2144/00291bm09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2∆∆C(T) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Watson RE, Jr., Wiegand SJ, Clough RW, Hoffman GE. Use of cryoprotectant to maintain long- term peptide immunoreactivity and tissue morphology. Peptides. 1986;7:155–159. doi: 10.1016/0196-9781(86)90076-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Franklin, K. B. J. & Paxinos, J. The mouse brain in stereotaxic coordinates. (Academic Press, San Diego, Ca, USA, 1997).

- 67.Rasband, W. S. ImageJ, U. S. National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland, USA, https://imagej.nih.gov/ij/, 1997–2018.

- 68.Schmid B, Helfrich-Förster C, Yoshii TA. New ImageJ Plug-in “ActogramJ” for Chronobiological Analyses. J. Biol. Rhythms. 2011;26:464–467. doi: 10.1177/0748730411414264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Schindelin J, et al. Fiji: an open-source platform for biological image analysis. Nat. Methods. 2012;9:676–682. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.