Abstract

Replicative senescence in human fibroblasts is absolutely dependent on the function of the phosphoprotein p53 and correlates with activation of p53-dependent transcription. However, no evidence for posttranslational modification of p53 in senescence has been presented, raising the possibility that changes in transcriptional activity result from upregulation of a coactivator. Using a series of antibodies with phosphorylation-sensitive epitopes, we now show that senescence is associated with major changes at putative regulatory sites in the N and C termini of p53 consistent with increased phosphorylation at serine-15, threonine-18, and serine-376 and decreased phosphorylation at serine-392. Ionizing and UV radiation generated overlapping but distinct profiles of response, with increased serine-15 phosphorylation being the only common change. These results support a direct role for p53 in signaling replicative senescence and are consistent with the generation by telomere erosion of a signal which shares some but not all of the features of DNA double-strand breaks.

Normal human somatic cells (with the possible exception of stem cells) are capable of only a finite number of cell divisions, after which they enter a nondividing though viable state termed replicative senescence (22, 55). The significance of this phenomenon for human health is two-edged. On the one hand, it imposes a natural obstacle to clonal expansion, which probably plays a vital part in limiting tumor development (2, 38, 59). On the other hand, in some tissues, notably skin and blood vessels, it may account for progressive functional abnormality with advancing age. This may result directly from loss of regenerative capacity but also indirectly through senescence-associated biochemical changes, a good example being the increased collagenase secretion by ageing dermal fibroblasts, which may be significant even when only a minority of cells are overtly senescent (11, 34). Knowledge of the underlying mechanisms of cellular senescence is therefore central to both cancer and aging research.

We and others have demonstrated that one key signal pathway mediating replicative senescence involves the phosphoprotein p53, more widely recognized for its role as a tumor suppressor, which is known to mediate growth arrest in response to a wide variety of cellular stress signals including DNA damage (31, 40). Experimental abrogation of p53 function prevents fibroblasts from entering senescence normally and indeed can reverse established senescence, demonstrating that p53, if not sufficient, is certainly necessary for this process (5, 6, 20). Furthermore, growth arrest in senescence is tightly correlated with switching on of the transcriptional transactivation function of p53, as revealed by the use of reporter constructs and by DNA binding assays (1, 7, 50).

Nevertheless, senescence has not thus far been shown to lead to any of the range of posttranslational modifications of the p53 protein which bring about its activation in response to other signals such as DNA damage (19). This therefore leaves open the possibility that the above data can be explained not by any primary modification of p53 itself but by upregulation of a p53 binding coactivator which modulates its ability to transactivate target promoters, for which there are several candidates (40), one of which, p33ING1 (18), has already been shown to be overexpressed in senescent fibroblasts (17). In other words, although its presence is essential, p53 may be merely playing the role of a passive partner rather than the active biochemical switch in senescence.

Failure in the past to detect changes in phosphorylation may have been due to reliance on conventional 32P metabolic labeling, which is now recognized to generate a DNA damage signal due to autoirradiation, which may itself perturb the phosphorylation state of p53 and hence mask the specific changes being sought (8). The recent availability of panels of antibodies to p53 whose binding is sensitive to the phosphorylation state of their epitopes (phosphospecific antibodies) has allowed us to reexamine this question without the risk of encountering this artifact. We now show for the first time that p53 is indeed subject to posttranslational modification in senescent fibroblasts and that the profile of changes in epitope reactivity overlaps but is distinct from that induced by DNA-damaging agents.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and culture conditions.

Human neonatal diploid fibroblasts (HCA2 fibroblasts; kindly provided by James Smith, Baylor College, Houston, Tex.) were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Gibco/BRL) containing 10% fetal calf serum (FCS) (Gibco/BRL). As described previously (20), the following minimum criteria were used for senescence: (i) failure to reach confluence up to 3 weeks after a final 1:2 passage despite regular refeeding; (ii) over 90% of cells showing the characteristic enlarged, flattened shape; and (iii) over 90% of cells failing to incorporate bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) after a 72-h labeling period, as detected by immunofluoresence (data not shown).

DNA-damaging agents.

For UV irradiation, medium was removed and dishes without lids were placed under a UVG-11 Mineralight lamp (U.V. Products, San Gabriel, Calif.) and exposed to 25 J of UVC per m2 over a period of 25 s before the cells were refed. For γ-irradiation (IR), sealed flasks were placed in a 137Cs source for ∼2 min, giving a total dose of 5 Gy.

Bleomycin (Lundbeck, Milton Keynes, United Kingdom) was added for 1 h at a final concentration of 250 μg/ml (previously determined as the lowest dose required to obtain maximal growth arrest in these cells), after which the cells were washed and refed with normal medium.

Antibodies.

Mouse monoclonal antibodies (as purified immunoglobulin preparations) were obtained either in-house (DO-12, FPS15, FPT18, and FPS392) or from Oncogene Science (PAb421, [Ab-1], DO-1 [Ab-6]) and diluted as appropriate in 0.6% bovine serum albumin in phosphate-buffered saline–Tween buffer prior to use.

Western blot analysis.

Cells (∼106) were lysed for 15 min at 0°C in 1% NP-40 in a buffer containing 25 mM HEPES (pH 7.6), 5 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 0.4 M KCl, 5 mM EDTA, 10 mM NaF, 2 μg of Pefabloc (Roche Diagnostics) per ml, 20 μg of leupeptin per ml, 1 μg of aprotinin per ml, 2 μg of pepstatin per ml, 10 μg of trypsin inhibitor per ml, and 1 mM benzamidine and cleared by centrifugation. Lysate supernatants (15 μg of protein per lane) were electrophoresed on a sodium dodecyl sulfate–10% polyacrylamide gel and blotted to polyvinylidene difluoride (Immobilon-P; Millipore, Watford, United Kingdom). Immunoreactive p53 was detected using antibody FPS15, FPT18, DO-1, DO-12, PAb421, or FPS392 at a concentration of 1 μg/ml followed by the enhanced chemiluminescence detection system (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Little Chalfont, United Kingdom) with peroxidase-conjugated rabbit anti-mouse secondary antibody. The blots were stained with India ink to check for equal protein loading. Signals were quantified by scanning using a GS700 imaging densitometer (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hemel Hempstead, United Kingdom) running Molecular Analyst software. In cases where protein loading was found to differ by more than 20%, the enhanced chemiluminescence signals were adjusted by normalizing to the India ink signal. All Western analyses were performed at least three times on independent lysates. The mean relative change (± standard error) from “control” is quoted (corrected for differences in protein loading where necessary), except in cases where one of the two samples gave no detectable signal.

In vitro phosphatase treatment.

Cell lysates were dialyzed at 4°C for 6 h against a buffer containing 25 mM HEPES (pH 7.6), 5 mM DTT, 0.2 M KCl, and 15% glycerol. Protein phosphatase 2A (Sigma Aldrich, Poole, United Kingdom) (0.5 U) was added to dialyzed lysate containing 15 μg of protein in a buffer containing 25 mM HEPES (pH 7.6), 50 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, 0.02% Triton X-100, 1 mM benzamidine, and 10% glycerol and incubated for 1 h at 30°C. The treated and control (mock-digested) lysates were then analyzed by Western blotting as above.

BrdU assay.

Cells undergoing DNA synthesis were identified by addition of BrdU (Roche Diagnostics) to a final concentration of 10 μM for 1 h prior to fixation in 70% ethanol (30 min at 4°C). After pretreatment with 4 M HCl (10 min) and 0.1 M borax (pH 8.5) (5 min), incorporated nuclear BrdU was detected using a mouse anti-BrdU primary antibody (Dako) followed by peroxidase-labeled rabbit anti-mouse immunoglobulin (Dako) and finally diaminobenzidine substrate. After the cells were counterstained with hematoxylin, the proportion of positive nuclei (BrdU labeling index) was assessed, based on a sample size of >300 cells per data point.

RESULTS

Posttranslational modification of p53 in senescent fibroblasts.

Evidence for posttranslational modification was sought using a panel of mouse monoclonal antibodies, extensively characterized in our laboratories, which are directed against sites of phosphorylation suspected of playing a significant role in regulating transcriptional activation by p53.

At the N terminus, we used antibody DO-1 (51), which binds an epitope (amino acids 20 to 25) overlapping the transactivation and mdm2 binding domain of p53 (9, 32, 46) and which we have recently shown to be inhibited by phosphorylation at serine-20 (8, 13), as well as two new in-house antibodies, FPS15 and FPT18, which we have shown to be specific for p53 phosphorylated at serine-15 (13) and threonine-18 (14), respectively.

At the C terminus, we used antibody PAb421, which recognizes an epitope (amino acids 372 to 382) (46) containing several serines, phosphorylation of at least one of which, serine-376, has been shown to block binding (53). For the putative casein kinase II site at amino acid 392, we used a new in-house monoclonal antibody FPS392 (J. P. Blaydes, H. M. Ball, N. J. Traynor, N. K. Gibbs, and T. R. Hupp, submitted for publication) raised against a peptide corresponding to amino acids 378 to 393 of human p53, including a phosphorylated residue at serine-392. Western blot analysis and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay using recombinant human p53 before and after phosphorylation by casein kinase II in vitro confirmed that FPS392 is specific for the phosphorylated form of its epitope under denaturing conditions or in solid-phase assays (Blaydes et al., submitted).

Finally, to control for changes in total p53 protein levels, we also used antibody DO-12, directed against the central core domain (amino acids 256 to 270) (3, 52), which is not known to be subject to phosphorylation in vivo.

Western blots (Fig. 1a) were prepared using lysates of “young” human diploid fibroblasts at population doubling level (PDL) of ∼35 and from the same stock of cells passaged until they reached replicative senescence (PDL ≈ 65), as defined previously (20).

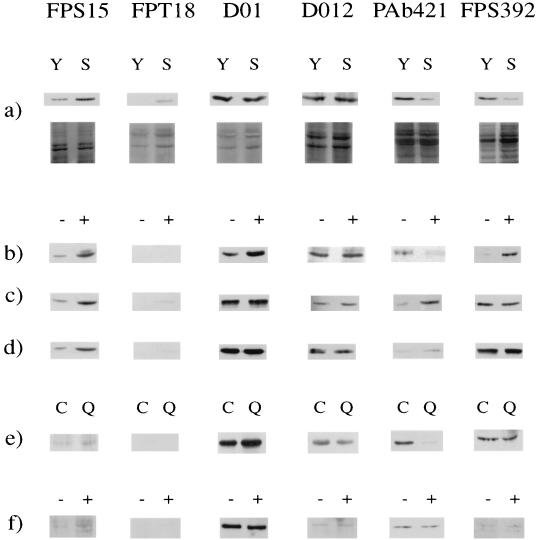

FIG. 1.

Effects of senescence, DNA-damaging agents, and quiescence on the immunoreactivity of p53 from human diploid fibroblasts. Western blot analysis of whole-cell lysates was performed using monoclonal antibodies FPS15, FPT18, DO-1, DO-12, PAb421, and FPS392 as indicated. (a) Comparison of senescent (S) with young (PDL ≈ 35) (Y) fibroblasts; (b to d) effects of UV radiation, IR, and bleomycin, respectively, on young fibroblasts (+) compared to mock-treated controls (−); (e) effect of quiescence induced by low serum concentrations (Q) compared to proliferating controls (C); (f) effect of long-term growth arrest observed 96 h after IR (+) compared to mock-treated controls (−). Blots were stained with India ink to check the equivalence of total-protein transfer in each pair of lanes (shown in the lower images of panel a only). The location of p53 migration was verified by comparison to a recombinant p53 standard (results not shown). Note that the values quoted in the text refer to means of at least three Western analyses and therefore, for some pairs of samples, do not correspond exactly to the single example shown here.

When normalized to total cellular protein, no change in the total amount of p53 protein was seen, using antibody DO-12, in lysates of senescent compared to young fibroblasts. Likewise, no change was observed with antibody DO-1, indicating no change in serine-20 phosphorylation (8). In contrast, the following changes were observed in senescent compared to young cell lysates. (i) At the N terminus, there was a 3.8- ± 0.2-fold increase (mean ± standard error) in binding of FPS15 and an even more marked induction of FPT18 binding, consistent with increased phosphorylation at serine-15 and de novo phosphorylation at threonine-18. (ii) There was a marked reduction in binding of both C-terminally directed antibodies, PAb421 and FPS392 (5.7- ± 0.4-fold and 5.4- ± 0.1-fold, respectively). Given the known opposing effects of phosphorylation on the binding of these two antibodies, this result is consistent with an increase in phosphorylation within the PAb421 epitope (most probably at serine-376) but a decrease in phosphorylation of the FPS392 epitope (at serine-392).

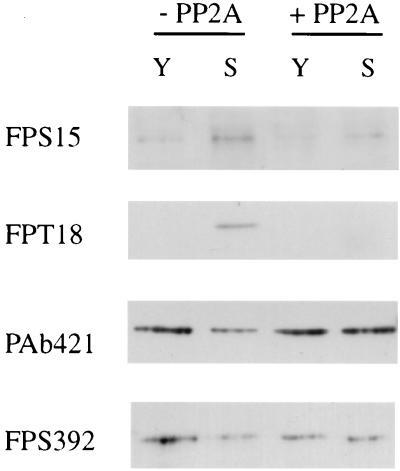

All of the above differences were abolished by pretreatment of lysates in vitro with protein phosphatase 2A prior to Western analysis (Fig. 2), confirming that they are the result of altered phosphorylation rather than other possible covalent modifications. The persistence of some binding for the FPS392 (and FPS15) epitopes almost certainly reflects the known difficulty in completely removing phosphates from some sites using pure catalytic subunits of phosphatases in vitro rather than reflecting any lack of antibody specificity, which we have shown to be extremely high on Western blots (13; Blaydes et al., submitted).

FIG. 2.

Reversal of senescence-induced changes in phosphospecific antibody binding by phosphatase treatment. A Western blot analysis of lysates from young (Y) or senescent (S) cultures after in vitro treatment with protein phosphatase 2A (+PP2A) compared to undigested lysates (−PP2A) is shown.

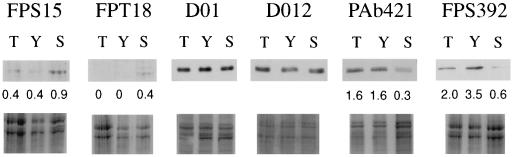

We repeated the above analyses using fibroblasts which had escaped senescence as a result of forced expression of the catalytic subunit of human telomerase (hTERT). These were derived in our laboratory by infection of presenescent HCA2 fibroblasts with a retroviral vector constructed by cloning hTERT cDNA into pBABEpuro (57) and, as expected from the original experiments of Bodnar et al. (4), have so far reached over 150 population doublings beyond their expected point of senescence, with no diminution in growth rate. Western blots (Fig. 3) performed on lysates of these presumed-immortal fibroblasts using our panel of phosphospecific antibodies showed a profile of phosphorylation which (apart from a partial reduction in FPS392 binding) closely resembled that of normal, young fibroblasts, indicating that stabilization of telomere length by hTERT is sufficient to prevent nearly all the changes in phosphorylation associated with senescence.

FIG. 3.

Abrogation of senescence-associated changes in p53 phosphorylation in fibroblasts immortalized by expression of hTERT. A Western blot analysis of lysates from young (Y) or senescent (S) fibroblasts, compared to a population (T) which have escaped senescence through forced expression of the catalytic subunit of telomerase, hTERT, analyzed at ∼80 population doublings beyond the normal proliferative life span is shown. For each of the four epitopes which show senescence-associated changes, the numbers indicate the intensity of the p53 band (upper panel) corrected for any differences in protein loading (lower panel). Note the overall similarity between the T and Y values.

Comparison of posttranslational modifications induced by senescence and DNA damage.

The same panel of antibodies was also used to assess the effects of DNA-damaging agents in young fibroblasts at doses shown previously to result in activation of p53-mediated transcription (7) and growth arrest (56).

To assess the effect of “bulky” lesions, such as pyrimidine dimers, fibroblasts were exposed to UV irradiation (25 J/m2) and lysates were prepared 16 h later for Western blot analysis (Fig. 1b). Somewhat unexpectedly, no change in overall p53 protein level could be detected using antibody DO-12. However, major changes in the binding of phospho-specific antibodies were observed. At the N terminus, there was an increase in FPS15 binding (6.3- ± 0.8-fold) similar to that seen in senescence. Unlike the latter, however, there was no change in FPT18 binding, which remained undetectable, but instead there was an increase in DO-1 binding (3.0- ± 0.1-fold), consistent with dephosphorylation at serine-20. At the C terminus, a 3.9- ± 0.1-fold decrease in PAb421 binding occurred, similar to that observed in senescence, but, in sharp contrast to the latter, a 12.0- ± 0.9-fold increase in binding to FPS392 was observed.

To assess the effect of DNA strand break damage, fibroblasts were exposed to IR (5 Gy) or bleomycin (250 μg/ml) and analyzed 4 h later (Fig. 1c and d). Again, no change in DO-12 binding was observed. At the N terminus, the changes were similar to those seen in senescence and consisted of an increase in FPS15 and FPT18 binding and (in contrast to the effect of UV) no change in binding to DO-1. At the C terminus, however, there was a sharp contrast to the effects of both senescence and UV, with no change in FPS392 binding and an increase as opposed to a decrease in binding to PAb421 (6.5- ± 0.5- and 2.1- ± 0.1-fold following IR and bleomycin treatment, respectively).

Effect of quiescence on posttranslational modifications of p53.

One possible confounding influence in the above comparisons is the growth state of the cultures being analyzed. In particular, in senescent cultures, essentially all cells are out of cycle, in contrast to young cultures 4 h after IR, in which a large proportion are still in S-phase, raising the possibility that some of the observed differences in phosphorylation between these two states, particularly the opposite changes at the PAb421 epitope, are misleading.

To address this, we first examined the effect of inducing growth arrest in young fibroblasts, independent of DNA damage, by plating subconfluent cultures in low serum concentrations (0.2% FCS) for 72 h, by which time only 3% of the cells were in S phase as assessed by 1 h of BrdU labeling, compared to 45% in control cultures proliferating in 10% FCS. At the N terminus, only minor changes in phosphospecific antibody binding were observed compared to control cultures in 10% FCS (<1.5-fold increase in binding of FPS15 and DO-1). At the C terminus, however, there was a striking decrease in PAb421 binding, of even greater magnitude (10.0- ± 0.7-fold) than that seen in senescence (Fig. 1e).

As a further test for secondary effects of the growth state, we also made use of the well-established finding (16, 33) that following 5-Gy IR, the vast majority of human fibroblasts eventually end up in a state of irreversible growth arrest resembling senescence. Cultures were studied 96 h after irradiation, at which point BrdU labeling confirmed near-total growth arrest (labeling index, <1%). In comparison to irradiated cells at 4 h, the increase in FPS15 binding was lower (2.5- ± 0.3-fold compared to 4.8- ± 0.2-fold) and there was no detectable binding of FPT18 (Fig. 1f). Furthermore, the increase in PAb421 binding seen at 4 h was no longer apparent at 96 h. Nevertheless, the resulting profile of phosphospecific epitope reactivities in these pseudosenescent cells was still clearly distinct from that of truly senescent, nonirradiated cells (Fig. 1; Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Contrasting effects of senescence, quiescence, and DNA-damaging agents on binding of monoclonal antibodies to p53 in human fibroblasts

| Treatment | Changea in binding of:

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DO-12 | FPS15 | FPT18 | DO-1 | PAb421 | FPS392 | |

| Senescence | → | ↑ | ↑ | → | ↓ | ↓ |

| UVR | → | ↑ | → | ↑ | ↓ | ↑ |

| IR (+4 h) | → | ↑ | ↑ | → | ↑ | → |

| Bleomycin | → | ↑ | ↑ | → | ↑ | → |

| Quiescence (0.2% FCS) | → | [↑]b | → | [↑]b | ↓ | → |

| IR (+96 h) | → | ↑ | → | → | → | → |

Changes are shown as increase (↑), decrease (↓), or unchanged (→) by Western blot analysis with respect to untreated, young fibroblast controls. See the text for quantitation and details of antibody specificities.

Less than 1.5-fold increase as estimated by densitometry.

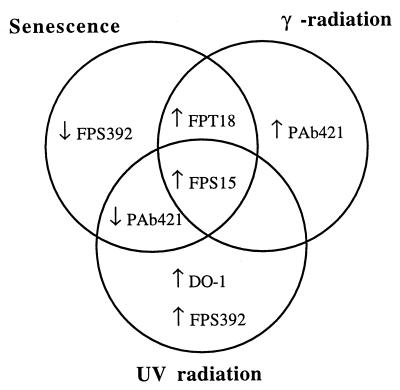

The changes in antibody binding under all the above conditions are summarized in Table 1 and Fig. 4.

FIG. 4.

Venn diagram highlighting the major similarities and differences between the effects of senescence, UV radiation, and IR on phosphospecific p53 epitopes in human diploid fibroblasts.

DISCUSSION

Our data show, for the first time, that replicative senescence in normal human fibroblasts is associated with major changes in the binding of phosphospecific antibodies to potential regulatory sites at both the N and C termini of p53.

These changes were observed after denaturing electrophoresis and must therefore reflect covalent modification rather than epitope masking by p53-binding proteins. Although at the C terminus, modifications other than phosphorylation are known to occur, notably acetylation (21, 42) and O glycosylation (43), given the specificities of the antibodies used and the results of phosphatase treatment, it is reasonable to assume that the observed alterations in epitope reactivity reflect the following: (i) at the N terminus, increased phosphorylation at serine-15 and threonine-18, and (ii) at the C terminus, decreased phosphorylation at serine-392, with increased phosphorylation at the PAb421 epitope, most probably at serine-376 (53).

We can only speculate that such changes were missed for technical reasons in previous studies, reflecting the inadvertant induction of a confounding DNA damage response by 32P labeling (8) and/or the lack of resolution of the approaches used (1, 29).

To obtain some insight into the functional significance of these changes and clues to possible upstream signals, we compared the patterns of phosphoepitope reactivity in senescent cells with those seen in the much better characterized models of p53 activation following DNA damage. At the N terminus, both UV and IR (as well as the radiomimetic agent bleomycin) led to increased binding of FPS15, of similar magnitude to that seen in senescence. Serine-15 phosphorylation has been consistently observed in response to DNA-damaging agents (39), and there is strong evidence for its functional role in activation and stabilization of p53 both by conformational changes and by disruption of mdm2 binding (44). Several candidate kinases have been identified (19), notably the ATM-related protein, ATR, and (more controversially) DNA-dependent protein kinase (26, 54) with evidence for differential roles in response to different forms of DNA damage. For example, ATM is required for the early response to IR (45) whereas ATR is required for the late response to IR and the response to UV (48). On the other hand, as far as we are aware, there are no previous reports of threonine-18 phosphorylation, which was observed here following IR and at senescence. However, recent in vitro studies indicate that it may be even more potent at disrupting the p53-mdm2 interaction (10, 14) and hence is a very plausible additional p53-activating mechanism.

In contrast to the similarity of effects of senescence and IR at the N terminus, IR led to increased rather than decreased binding of PAb421 at the C terminus. Unmasking of the PAb421 epitope following IR has been reported previously by Waterman et al. (53), who provided evidence that it results from ATM-dependent activation of a serine-376 phosphatase and activates p53 by allowing its association with a 14-3-3 protein. It is not clear, however, how this can be reconciled with previous evidence, albeit mainly from in vitro studies, that the opposite change, i.e., masking of the PAb421 epitope (through phosphorylation or antibody binding) can also lead to activation of DNA binding and transcription factor activity (20, 23–25, 37, 47). Interestingly, UV radiation, while causing the same changes at serine-15 as were seen following IR, resulted in increased masking of the epitope at the PAb421 site, thereby resembling senescence rather than IR. This was accompanied by two other changes not seen following IR, increased DO-1 binding, reflecting decreased serine-20 phosphorylation, and increased FPS392 binding, indicating increased serine-392 phosphorylation; both of these have been reported previously in other cell models (3, 13, 27, 35).

We considered the possibility that the contrasting findings at the PAb421 site reflected the fact that cell cycle arrest is much more complete in senescence and at 16 h following UV radiation than at the much earlier time point (4 h) used for studying the response to IR (these times having been decided on the basis of maximum p53 functional responses reported in the literature). Indeed, there is long-standing support for this from the work of Milner and Watson, who showed loss of PAb421 binding correlating with quiescence unrelated to DNA damage (36). We therefore examined the effect of cell cycle arrest induced by serum deprivation (which we and others have shown to be p53 independent) and indeed found a marked diminution of PAb421 binding of even greater magnitude than that seen at senescence and with only minimal changes at the N terminus. As a further approach to addressing the possible confounding influence of growth state, we also analyzed cells at a later time (96 h) after IR, when the vast majority have undergone an irreversible growth arrest with features similar to senescence (16, 33, 41). The initial increase in binding of the PAb421 epitope observed at 4 h had completely reverted to control levels by this time despite evidence for continued modification at the N terminus.

The simplest interpretation of these data is that growth arrest leads secondarily to increased phosphorylation at the PAb421 epitope, which is “unopposed” in senescent and UV-irradiated cells but which is effectively counterbalanced in IR-treated cells by a persisting dephosphorylation response. This is consistent with evidence for ATM-dependent activation of a putative serine-376 phosphatase by IR (53) and with the lack of involvement of ATM in the response to UV (12, 28, 45). The similarity between UV and senescence in turn suggests that the latter may also be ATM independent. Indeed, this would be consistent with the observation that senescence in ATM-deficient human fibroblasts is not delayed and is associated with normal induction of p53 DNA binding activity (50). As has been suggested recently (30, 48), it is likely that different genomic stress stimuli signal to p53 via overlapping but distinct combinations of kinases of the phosphoinositide 3-kinase-related superfamily. It will be of interest to determine, therefore, whether, as in the case of UV (48), it is the ATR kinase, rather than ATM, which plays an essential role in senescence.

In summary, these data identify overlapping but distinct profiles of p53 amino acid phosphorylation in response to senescence and DNA damage, two of which, serine-15 and threonine-18, are highly plausible as activating modifications on the basis of their known biological effects. Candidate transcriptional targets for p53 activated at senescence include p21waf1, whose induction in senescent fibroblasts is blocked by antibodies directed at the N-terminal transactivation domain of p53, as shown by our group previously (20); interestingly, though, we have failed to detect any induction of another major p53 target, mdm2, by Western blot analysis of senescent fibroblasts (K. Webley and D. Wynford-Thomas, unpublished data).

There is now very strong evidence, both observational and experimental, that the underlying cell division “clock” which triggers senescence is based on the progressive erosion of chromosome telomeres (4). Our finding that the changes in p53 phosphorylation at senescence are almost entirely abrogated in cells which have been immortalized by forced expression of telomerase show that these modifications are not just a nonspecific response to time or the number of cell divisions in culture but are a specific consequence of telomere erosion. We and others (15, 49, 58) have suggested that one or more critically short telomeres may, through loss of telomere binding proteins, generate a free end, which is effectively seen as a double-strand break, thereby generating a signal to p53 via pathways shared with DNA damage responses. Our data provide further support for such a model, although they also indicate the existence of significant differences in the signal pathways involved.

The panel of changes described here also represents, to our knowledge, the most comprehensive study of p53 phosphorylation following DNA damage in the context of a normal primary human cell, avoiding the potential confounding influence of preexisting, unknown p53-modifying signals which are likely to be present in most of the transformed cell line models used previously for this purpose (3, 44, 45, 48, 53).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to James Smith (Baylor College, Houston, Tex.) for human fibroblasts and to Theresa King for manuscript preparation. We thank Julia Skinner for supplying fibroblasts expressing hTERT.

We thank the Cancer Research Campaign for grant support.

REFERENCES

- 1.Atadja P, Wong H, Garkavtsev I, Geillette C, Riabowol K. Increased activity of p53 in senescing fibroblasts. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:8348–8352. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.18.8348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bacchetti S, Counter C M. Telomeres and telomerase in human cancer. Int J Oncol. 1995;7:423–432. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blaydes J P, Hupp T. DNA damage triggers DRB-resistant phosphorylation of human p53 at the CK2 site. Oncogene. 1998;17:1045–1052. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bodnar A G, Ouellette M, Frolkis M, Holt S E, Chiu C-P, Morin G B, Harley C B, Shay J W, Lichtsteiner S, Wright W E. Extension of life-span by introduction of telomerase into normal human cells. Science. 1998;279:349–352. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5349.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bond J A, Wyllie F S, Wynford-Thomas D. Escape from senescence in human diploid fibroblasts induced directly by mutant p53. Oncogene. 1994;9:1885–1889. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bond J A, Blaydes J P, Rowson J, Haughton M F, Smith J R, Wynford-Thomas D, Wyllie F S. Mutant p53 rescues human diploid cells from senescence without inhibiting the induction of SD11/WAF1. Cancer Res. 1995;55:2404–2409. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bond J A, Haughton M, Blaydes J, Gire V, Wynford-Thomas D, Wyllie F. Evidence that transcriptional activation by p53 plays a direct role in the induction of cellular senescence. Oncogene. 1996;13:2097–2104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bond J A, Webley K, Wyllie F S, Jones C J, Craig A, Hupp T, Wynford-Thomas D. p53-Dependent growth arrest and altered p53-immunoreactivity following metabolic labelling with 32P ortho-phosphate in human fibroblasts. Oncogene. 1999;18:3788–3792. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bottger V, Bottger A, Howard S F, Picksley S M, Chene P, Carcia-Echeverria C, Hochkeppel H-K, Lane D P. Identification of novel mdm2 binding peptides by phage display. Oncogene. 1996;13:2141–2147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bottger V, Bottger A, Garcia-Echeverria C, Ramos Y, van der Eb A, Jochemsen A, Lane D. Comparative study of the p53-mdm2 and p53-MDMX interfaces. Oncogene. 1999;18:189–199. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Campisi J. The biology of replicative senescence. Eur J Cancer. 1997;33:703–709. doi: 10.1016/S0959-8049(96)00058-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Canman C E, Wolff A C, Chen C Y, Fornace A J, Jr, Kastan M B. The p53-dependent G1 cell cycle checkpoint pathway and ataxia-telangiectasia. Cancer Res. 1994;54:5054–5058. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Craig A, Blaydes J, Burch L, Thompson A, Hupp T. Dephosphorylation of human p53 at serine20 following cellular exposure to low levels of non-ionizing radiation. Oncogene. 1999;18:6305–6312. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Craig A L, Burch L, Vojtesek B, Mikutowska J, Thompson A, Hupp T R. Novel phosphorylation sites of human tumour suppressor protein p53 at Ser20 and Thr18 that disrupt the binding of mdm2 (mouse double minute 2) protein are modified in human cancers. Biochem J. 1999;342:133–141. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.de Lange T. Telomere dynamics and genome instability in human cancer. Cold Spring Harbor Monogr Ser. 1995;10:1–27. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Di Leonardo A, Linke S P, Clarkin K, Wahl G M. DNA damage triggers a prolonged p53-dependent G1 arrest and long-term induction of Cip1 in normal human fibroblasts. Genes Dev. 1994;8:2540–2551. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.21.2540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garkavtsev I, Riabowol K. Extension of the replicative lifespan of human diploid fibroblasts by inhibition of the p33ING1 candidate tumor suppressor. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:2014–2019. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.4.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Garkavtsev I, Grigorian I A, Ossovskaya V S, Chernov M V, Chumakov P M, Gudkov A V. The candidate tumour suppressor p33INK1 cooperates with p53 in cell growth control. Nature. 1998;391:295–298. doi: 10.1038/34675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Giaccia A J, Kastan M B. The complexity of p53 modulation: emerging patterns from divergent signals. Genes Dev. 1998;12:2973–2983. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.19.2973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gire V, Wynford-Thomas D. Reinitiation of DNA synthesis and cell division in senescent human fibroblasts by microinjection of anti-p53 antibodies. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:1611–1621. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.3.1611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gu W, Roeder R G. Activation of p53 sequence-specific DNA binding by acetylation of the p53 C-terminal domain. Cell. 1997;90:595–606. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80521-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hayflick L. The limited in vitro lifetime of human diploid cell strains. Exp Cell Res. 1965;37:614–636. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(65)90211-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hupp T R, Lane D P. Regulation of the cryptic sequence-specific DNA-binding function of p53 by protein kinases. Cold Spring Harbor Symp Quant Biol. 1994;59:195–206. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1994.059.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hupp T R, Lane D P. Allosteric activation of latent p53 tetramers. Curr Biol. 1994;4:865–875. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00195-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hupp T R, Sparks A, Lane D P. Small peptides activate the latent sequence-specific DNA binding function of p53. Cell. 1995;83:237–245. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90165-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jimenez G S, Bryntesson F, Torres-Arzayus M I, Priestley A, Beeche M, Saito S, Sakaguchi K, Appella E, Jeggo P A, Taccioli G E, Wahl G M, Hubank M. DNA-dependent protein kinase is not required for the p53-dependent response to DNA damage. Nature. 1999;400:81–83. doi: 10.1038/21913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kapoor M, Lozano G. Functional activation of p53 via phosphorylation following DNA damage by UV but not gamma radiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:2834–2837. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.6.2834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Khanna K K, Keating K E, Kozlov S, Scott S, Gatei M, Hobson K, Taya Y, Gabrielli B, Chan D, Lees-Miller S P, Lavin M F. ATM associates with and phosphorylates p53: mapping the region of interaction. Nat Genet. 1998;20:398–400. doi: 10.1038/3882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kulju K S, Lehman J M. Increased p53 protein associated with aging in human diploid fibroblasts. Exp Cell Res. 1995;217:336–345. doi: 10.1006/excr.1995.1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lakin N, Hann B, Jackson S. The ataxia-telangiectasia related protein ATR mediates DNA-dependent phosphorylation of p53. Oncogene. 1999;18:3989–3995. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lane D P. p53, guardian of the genome. Nature. 1992;358:15–16. doi: 10.1038/358015a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lin J, Teresky A K, Levine A J. Two critical hydrophobic amino acids in the N-terminal domain of the p53 protein are required for the gain of function phenotypes of human p53 mutants. Oncogene. 1995;10:2387–2390. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Linke S P, Clarkin K C, Wahl G M. p53 mediates permanent arrest over multiple cell cycles in response to gamma-irradiation. Cancer Res. 1997;57:1171–1179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Linskens M H, Feng J, Andrews W H, Enlow B E, Saati S M, Tonkin L A, Funk W D, Villeponteau B. Cataloging altered gene expression in young and senescent cells using enhanced differential display. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:3244–3251. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.16.3244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lu H, Taya Y, Ikeda M, Levine A J. Ultraviolet radiation, but not gamma radiation or etoposide-induced DNA damage, results in the phosphorylation of the murine p53 protein at serine-389. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:6399–6402. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.11.6399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Milner J, Watson J V. Addition of fresh medium induces cell cycle and conformation changes in p53, a tumour suppressor protein. Oncogene. 1990;5:1683–1690. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mundt M, Hupp T, Fritsche M, Merkle C, Hansen S, Lane D, Groner B. Protein interactions at the carboxyl terminus of p53 result in the induction of its in vitro transactivation potential. Oncogene. 1997;15:237–244. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Parkinson E K, Newbold R F, Keith W N. The genetic basis of human keratinocyte immortalisation in squamous cell carcinoma development: the role of telomerase reactivation. Eur J Cancer. 1997;33:727–734. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(97)00063-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Prives C. Signaling to p53: breaking the MDM2-p53 circuit. Cell. 1998;95:5–8. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81774-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Prives C, Hall P. The p53 pathway. J Pathol. 1999;187:112–126. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199901)187:1<112::AID-PATH250>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Robles S J, Adami G R. Agents that cause DNA double strand breaks lead to p16INK4a enrichment and the premature senescence of normal fibroblasts. Oncogene. 1998;16:1113–1123. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sakaguchi K, Herrera J E, Saito S, Miki T, Bustin M, Vassilev A, Anderson C W, Appella E. DNA damage activates p53 through a phosphorylation-acetylation cascade. Genes Dev. 1998;12:2831–2841. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.18.2831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shaw P, Freeman J, Bovey R, Iggo R. Regulation of specific DNA binding by p53: evidence for a role for O-glycosylation and charged residues at the carboxy-terminus. Oncogene. 1996;12:921–930. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shieh S Y, Ikeda M, Taya Y, Prives C. DNA damage-induced phosphorylation of p53 alleviates inhibition by MDM2. Cell. 1997;91:325–334. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80416-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Siliciano J D, Canman C E, Taya Y, Sakaguchi K, Appella E, Kastan M B. DNA damage induces phosphorylation of the amino terminus of p53. Genes Dev. 1997;11:3471–3481. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.24.3471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stephen C W, Helminen P, Lane D P. Characterisation of epitopes on human p53 using phage-displayed peptide libraries: insights into antibody-peptide interactions. J Mol Biol. 1995;248:58–78. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Takenaka I, Morin F, Seizinger B R, Kley N. Regulation of the sequence-specific DNA binding function of p53 by protein kinase C and protein phosphatases. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:5405–5411. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.10.5405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tibbetts R S, Brumbaugh K M, Williams J M, Sarkaria J N, Cliby W A, Shieh S Y, Taya Y, Prives C, Abraham R T. A role for ATR in the DNA damage-induced phosphorylation of p53. Genes Dev. 1999;13:152–157. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.2.152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.van Steensel B, Smogorzewska A, de Lange T. TRF2 protects human telomeres from end-to-end fusions. Cell. 1998;92:401–413. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80932-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vaziri H, West M D, Allsopp R C, Davison T S, Wu Y-S, Arrowsmith C H, Poirier G G, Benchimol S. ATM-dependent telomere loss in aging human diploid fibroblasts and DNA damage lead to the post-translational activation of p53 protein involving poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase. EMBO J. 1997;16:6018–6033. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.19.6018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vojtesek B, Bartek J, Midgley C A, Lane D P. An immunochemical analysis of the human nuclear phosphoprotein p53. J Immunol Methods. 1992;151:237–244. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(92)90122-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vojtesek B, Dolezalova H, Lauerova L, Svitakova M, Havlis P, Kovarik J, Midgley C A, Lane D P. Conformational changes in p53 analysed using new antibodies to the core DNA binding domain of the protein. Oncogene. 1995;10:389–393. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Waterman M J, Stavridi E S, Waterman J L, Halazonetis T D. ATM-dependent activation of p53 involves dephosphorylation and association with 14-3-3 proteins. Nat Genet. 1998;19:175–178. doi: 10.1038/542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Woo R A, McLure K G, Lees-Miller S P, Rancourt D E, Lee P W K. DNA-dependent protein kinase acts upstream of p53 in response to DNA damage. Nature. 1998;394:700–704. doi: 10.1038/29343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wright W E, Shay J W. Time, telomeres and tumours: is cellular senescence more than an anticancer mechanism? Trends Cell Biol. 1995;5:293–297. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(00)89044-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wyllie F S, Haughton M F, Bond J A, Rowson J M, Jones C J, Wynford-Thomas D. S phase cell-cycle arrest following DNA damage is independent of the p53/p21 WAF1 signalling pathway. Oncogene. 1996;12:1077–1082. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wyllie F S, Jones C J, Skinner J W, Haughton M F, Wallis C, Wynford-Thomas D, Farragher R G, Kipling D. Telomerase prevents the accelerated cell ageing of Werner syndrome fibroblasts. Nat Genet. 2000;24:16–17. doi: 10.1038/71630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wynford-Thomas D, Bond J A, Wyllie F S, Jones C J. Does telomere shortening drive selection for p53 mutation in human cancer? Mol Carcinog. 1995;12:119–123. doi: 10.1002/mc.2940120302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wynford-Thomas D. Proliferative lifespan checkpoints: cell-type specificity and influence on tumour biology. Eur J Cancer. 1997;33:716–726. doi: 10.1016/S0959-8049(97)00064-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]