Abstract

Introduction

The burden of malnutrition is widely evaluated in Bangladesh in different contexts. However, most of them determine the influence of sociodemographic factors, which have limited scope for modification and design intervention. This study attempted to determine the prevalence of underweight, overweight and obesity and their modifiable lifestyle predictors in a rural population of Bangladesh.

Methods

This study was part of a cross-sectional study that applied the WHO Package of Essential Noncommunicable Disease Interventions in a rural area of Bangladesh to assess the burden of diabetes, hypertension and their associated risk factors. Census was used as the sampling technique. Anthropometric measurement and data on sociodemographic characteristics and behavioural risk factors were collected following the standard protocol described in the WHO STEP-wise approach. Analysis included means of continuous variables and multinomial regression of factors.

Results

The mean body mass index of the study population was 21.9 kg/m2. About 20.9% were underweight, 16.4% were overweight and 3.5% were obese. Underweight was most predominant among people above 60 years, while overweight and obesity were predominant among people between 31 and 40 years. Higher overweight and obesity were noted among women. Employment, consumption of added salt and inactivity increased the odds of being underweight by 0.32, 0.33 and 0.14, respectively. On the other hand, the odds of being overweight or obese increased by 0.58, 0.55, 0.78, 0.21 and 0.25 if a respondent was female, literate, married, housewife and consumed red meat, and decreased by 0.38 and 0.18 if a respondent consumed added salt and inadequate amounts of fruits and vegetables, respectively. Consumption of added salt decreases the odds of being overweight or obese by 0.37.

Conclusion

The study emphasised malnutrition to be a public health concern in spite of the dynamic sociodemographic scenario. Specific health messages for targeted population may help improve the nutritional status. Findings from further explorations may support policies and programmes in the future.

Keywords: public health, nutrition & dietetics, epidemiology

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study assessed the current status of malnutrition and look at its association with different modifiable risk factors among adults in a selected rural population of Bangladesh.

Census was used as the sampling technique and data were collected from all adults except those institutionalised in a hospital, prison, nursing home or other similar institutions.

The study could only investigate a third of the individuals since the community clinics were not attended by everyone who were included in the household survey.

Introduction

As studies show, malnutrition is one of the risk factors responsible for non-communicable diseases (NCDs) globally.1 2 About one-third of people in any community have at least one form of malnutrition, which includes disorders caused by excessive and/or imbalanced intake, leading to obesity and overweight, and disorders caused by deficient intake of energy or nutrients, leading to stunting, wasting and micronutrient deficiencies. Both overnutrition and undernutrition are caused by intake of unhealthy and poor quality diets.1 Body mass index (BMI) is an indicator of healthy weight, underweight, overweight and obesity.2 Studies show that the prevalence of obesity and overweight has been increasing over time.3 Globally, about 39% of adult population are overweight and 13% are obese as of 2016.4 At least 2.8 million people die each year due to causes related to obesity and overweight.5 Data from a national survey show that in Bangladesh about 30.4%, 18.9% and 4.6% of adults were underweight, overweight and obese, respectively.6

Unhealthy dietary behaviour, low physical activity, genetics, family history of certain diseases, community environment and usage of some drugs can lead to obesity and overweight.7 Obesity and overweight are two of the key risk factors for NCDs such as cardiovascular diseases and diabetes mellitus, which are known major public health concerns.8–10 Cardiovascular and respiratory diseases, cancer and diabetes are responsible for about 41 million deaths each year.1 11 Diabetes and hypertension have some common and important risk factors, such as unhealthy diet, inadequate physical inactivity, tobacco use, abnormal lipid profiles and overweight/obesity.12 About 85.0% of premature deaths from NCDs now occur in low-income and middle-income countries, where greater burden of undernutrition and infectious diseases also exists.1 13 In economically well-off countries, NCDs are noted disproportionately among vulnerable and disadvantaged groups.2 On the other hand, in less developed economies, childhood undernutrition affects health, survival, growth and development in rural population.1 Globally, undernutrition contributes to around 45% of deaths among under-5 children, the majority of which occur in low-income and middle-income countries.1

Attempting to look closely at the link between unhealthy diets and NCDs, it is seen to be the logical outcome of the dramatic shift in current food systems, which focus on increasing availability of inexpensive, high-calorie foods at the expense of diversity replacing local, often healthier diets. Availability of micronutrient-rich foods (eg, fresh fruits, vegetables, legumes, pulses and nuts) has not improved equally for everyone. Unhealthy foods with salt, sugars, saturated fat/trans fat, sweetened drinks, and processed and ultra-processed foods have become cheaper and more widely available.1 Studies show that reduction in risk factors through lifestyle modifications helps greatly in reducing the burden of most NCDs, including hypertension, diabetes, malnutrition and mental disorders.14 15 Studies in rural Bangladesh found that 55% of women ate rice twice a day as the staple food, while about 80% and 18% of women ate chicken on a weekly and monthly basis, respectively.16 17

Under these circumstances, developing countries like Bangladesh can benefit from interventions that help the primary healthcare facilities to be ready to tackle different NCDs that are predisposed by overweight, obesity and undernutrition. This study provides an opportunity to find the influencing factors and predictors of malnutrition in the current changing lifestyle among selected communities. This study was conducted to determine the prevalence of underweight, overweight and obesity and their predictors in a rural population of Bangladesh. Previous studies in Bangladesh have looked at the risk factors of malnutrition in association with different sociodemographic characteristics.18–26 This study builds up on the previous studies by examining the association of various risk factors with underweight, overweight and obesity on a large data set of adult population.

Methods

Study design, setting and participants

This was a cross-sectional study that incorporated quantitative methods to fulfil the study objectives. It was part of an implementation research in a randomly selected union (smallest rural administrative and local government units), Dhangara, among the three unions (Brammagachha, Chandaikona and Dhangara) of the Raiganj subdistrict in the Sirajganj district of Bangladesh. The three unions of Raiganj have been under an active health and demographic surveillance system of the implementing organisation Centre for Injury Prevention and Research Bangladesh since 2006. Dhangara Union has 12 323 households with a population size of 51 759, of whom 35 704 were adult population (≥18 years old) during the data collection.

Census was used as the sampling technique and included all adults except those who were mentally challenged or institutionalised in a hospital, prison, nursing home or other similar institutions. The duration of the study was 6 months, from January to June 2019, while data were collected from March to June 2019.

Data collection instrument and procedure

As a part of an implementation research, this study collected data by screening out the sociodemographic and cardiometabolic risk factors of chronic diseases (hypertension, diabetes) and determine their prevalence. The study adapted the procedure as described in the WHO Package of Essential Noncommunicable Disease Interventions model.27

Data were collected electronically at the household level using an Android-based mobile platform software. Interviewer-administered face-to-face interview was used to collect data. The questionnaire was prepared based on the STEP-wise approach to Surveillance (STEPS) of NCD risk factors by the WHO (version 3.2). The STEPS questionnaire was modified and used to ask questions on sociodemographic characteristics, behavioural risk factors (such as tobacco and alcohol consumption, physical activity, dietary habits, added salt intake) and occurrence of chronic disease, and to measure physical and biochemical parameters (height, weight, blood glucose, blood pressure). The English STEPS questionnaire was first translated to Bangla and then finalised after necessary modification following pretesting on a suitable population. Data collectors having requisite background were recruited and intensively trained before the commencement of data collection.

Screening at community level posed specific challenges that were identified and addressed, such as the time of day or day of the week to reach a particular population, such as office goers, farmers and home makers, especially for men. The use of active surveillance provided the advantage of having a full list of households and addresses, which ensured full coverage of the survey area. Data collectors were provided with the list and information required to track each household. If the respondent was unable to provide information when the data collector visited, a new time was scheduled for the screening as per convenience of the household member and the data collector. All possible measures were taken to ensure full coverage of the population.

During household data collection, existing chronic diseases (hypertension, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, etc) among the members were explored. Each participant was interviewed for approximately 25–30 min. Treatment and other medical documents were reviewed to confirm the disease conditions, and show cards were used for food and physical activity to ensure quality data. In some cases, where a person was not able to respond to data collectors’ queries (those who were ill or had some form of disability), an appropriate person from the household, for example the caregiver, was asked to answer on behalf provided he/she could give the exact information.

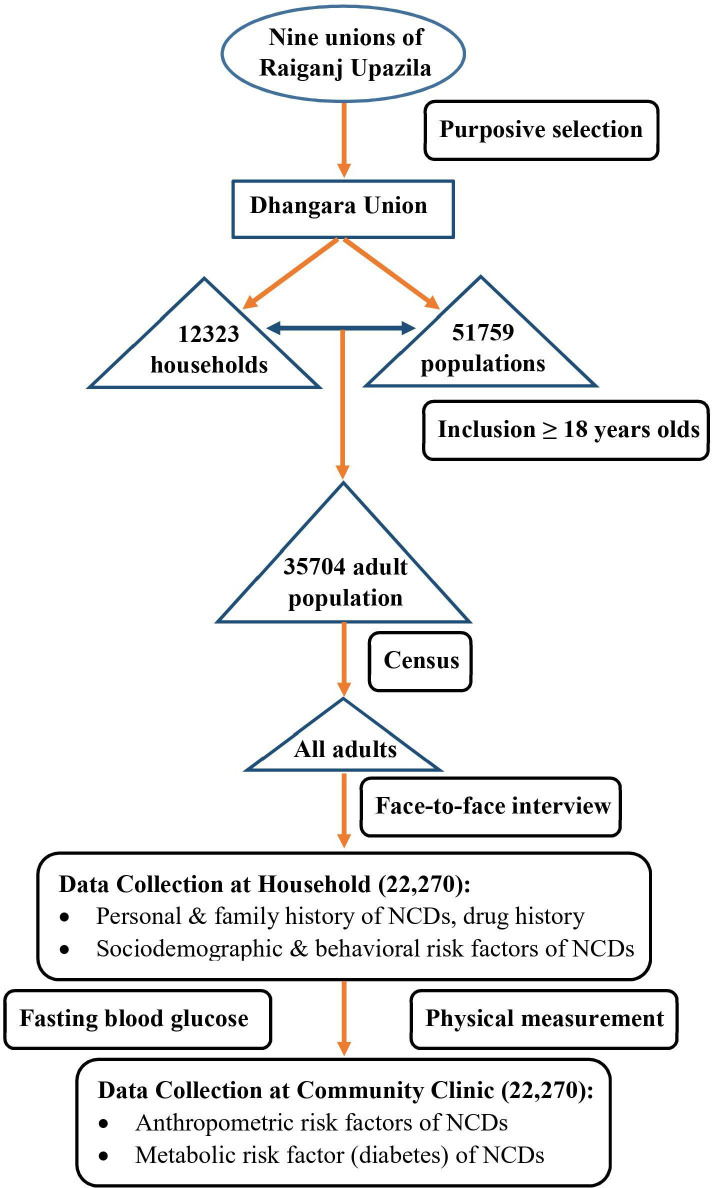

The household survey participants were advised to visit the nearby community clinic (CC) on the next day in a fasting state (not taking food and water for 8–12 hours) to assess their physical and biochemical parameters. In the CC, standard weight scale, height measurement scales, measuring tape and automated digital blood pressure machine were used to record weight, height, waist circumference, hip circumference and blood pressure, respectively. Fasting capillary glucose was measured by a standard glucometer maintaining all necessary aseptic precautions. Blood pressure was measured twice: first, after a 15 min rest time, and the second one 3 min after the first measurement. The mean of the two measurements was used to determine actual blood pressure. Physical measurements were carried out by well-trained male and female assistants maintaining adequate privacy. The data collected at the CC were synced with those collected at the household level. The flow chart of the study methods applied to collect data is shown in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of study methods applied to collect data from a selected rural population of Bangladesh. NCDs, non-communicable diseases.

Ascertainment of key variables

Age: respondents were asked what their age (in years) was at the time of data collection.

Sex: respondents were asked which sex (male or female) did they identify themselves as at the time of data collection.

Education: respondents were asked what was the highest level of education (no schooling, primary, and secondary and above) obtained by them at the time of data collection.

Marital status: respondents were asked if they were ever married or never married.

Occupation: respondents were asked about their occupation. Occupation was classified as unemployed, service holder, farmer, self-employed and housewife.

Red meat intake: respondents who said that they ate red meat on a weekly basis were categorised as consumers of red meat.

Fried food intake: respondents who said that they ate fried food on a weekly basis were categorised as consumers of fried food.

Processed food intake: respondents who said that they ate processed food on a weekly basis were categorised as consumers of processed food.

Sugary drink intake: respondents who said that they ate sugary drinks on a weekly basis were categorised as consumers of sugary drinks.

Added salt intake: respondents who said they took extra dietary salt while eating any cooked meal were categorised as consumers of added dietary salt.

Adequate amount of fruit and vegetable: respondents whose dietary intake of fruit and vegetable corresponded to WHO recommended five servings were considered as taking adequate amount of fruit and vegetable.28

Physical activity: respondents were asked about their work-related physical activities, the number of days a week and the amount of time (in minutes) per day that they spend on vigorous and moderate activities. This was then converted to metabolic equivalent of task-minutes (MET-min) to find out the intensity of physical activity, which was then categorised. The categories were less active or sedentary (≤600 MET-min/week), moderately active (between 600 and 3000 MET-min/week), and highly or vigorously active (≥3000 MET-min/week).29

Underweight: respondents were considered as underweight when their BMI was less than 18.5 kg/m2.30

Normal weight: respondents were considered to have normal weight when their BMI was between 18.5 and 25.0 kg/m2.30

Overweight: respondents were considered overweight when their BMI was between 25.0 and 29.9 kg/m2.30

Obese: respondents were considered obese when their BMI was over 30.0 kg/m2.30

Data analysis

Data were entered in a predesigned Microsoft Office Excel format which was later imported into statistical software STATA V.12. The raw data were initially checked for completeness, consistency, and absence of missing data, errors and outliers. Afterwards, data were carefully cleaned and edited for consistency and for preserving for longer time. Descriptive and relevant statistical analyses were performed on this cleaned data set. The results were then presented in tables and illustrations. Of the 22 270 respondents at the household level, a total of 11 244 visited the CC for the required physical measurements. After cleaning the data, the final analysis was done with a sample of 11 064 respondents.

To assess the distribution of anthropometric measurements among the respondents, the means of the continuous variables were calculated and presented in a tabulated form with range and SD. A pie chart was used to show the overall nutritional status of the respondents. Descriptive analysis was done to show the distribution of nutritional status and presented as percentage. To identify the sociodemographic and behavioural risk factors affecting malnutrition, multinomial regression analysis was used. In this regard, at first, the assumptions of regression analysis were checked and no violations of these assumptions were found. These assumptions included multicollinearity, outlier, normality, linearity, homoscedasticity and the independence of observations. Univariate analysis was performed to determine the eligibility of the variables before including them in the multinomial regression analysis. The variables included were age, sex, education, marital status, occupation, physical activity, red meat intake, fried food intake, processed food intake, sugary drink intake, added salt intake and inadequate intake of fruits and vegetables. During the univariate analysis, only the variables which showed p<0.05 (online supplemental table 1) were considered eligible for inclusion in the multinomial regression analysis. The dependent variable was categorised as underweight, normal weight, overweight and obesity. As per literature review, overweight and obesity have similar predictors. As such, overweight and obesity were merged together into one category, and normal weight was considered as reference. The regression table for each outcome variable included the presentation of the factors with the corresponding OR, and those with OR >1 were considered as predictors. The estimates of precision were all presented at a 95% CI, as appropriate. The significant threshold of p value for all the tables included in the analysis was less than 0.05.

bmjopen-2021-051701supp001.pdf (80KB, pdf)

Patient and public involvement

Data were collected from all adults at the household level. Further anthropometric data were collected at the health facilities from those who visited the CC. However, the public were not directly involved in the research. They did not play any role during the establishment of the research questions, designing or implementing the study, measuring the study outcomes, or interpretation of the results.

Ethical consideration

Participants had the right to withdraw at any point after starting the interview. Rigour, accuracy and impartiality were ensured during data collection through inperson and digital monitoring systems.

Results

Anthropometric measurements

The mean anthropometric measurements of the respondents and the SD with the minimum and maximum values are shown in table 1. The mean weight, height and BMI of the respondents were 51.4 kg, 153.4 cm and 21.9 kg/m2, respectively. The mean waist circumference, hip circumference and waist to hip ratio were 79.9 cm, 87.2 cm and 0.9, respectively.

Table 1.

Mean anthropometric measurements of respondents with SD and minimum and maximum values (N=11 064)

| Mean measurements | Mean (SD) | Minimum | Maximum |

| Weight (kg) | 51.4 (10.4) | 30.0 | 139.0 |

| Height (cm) | 153.4 (8.9) | 78.0 | 203.2 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 21.9 (4.2) | 10.1 | 78.9 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 79.9 (10.8) | 43.0 | 144.0 |

| Hip circumference (cm) | 87.2 (8.7) | 60.0 | 160.0 |

| Waist to hip ratio | 0.9 (0.1) | 0.6 | 1.6 |

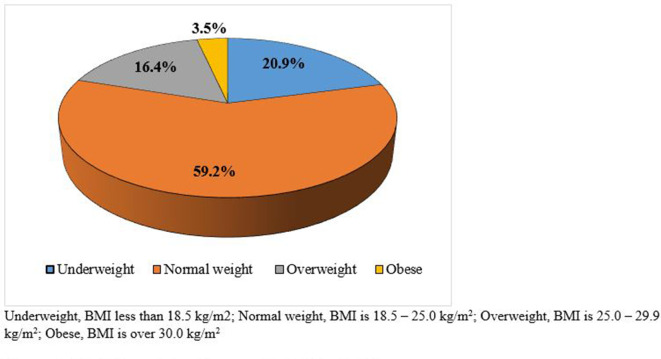

Considering BMI, 59.2% of the respondents were within normal range, that is, between 18.5 and 25.0 kg/m2. Underweight was found in 20.9% of the respondents, while overweight and obesity were found in 16.4% and 3.5% of the respondents, respectively (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Nutritional status of respondents (N=11 064). BMI, body mass index.

Sociodemographic characteristics

The sociodemographic characteristics of the respondents are stratified by nutritional status and shown in table 2. Irrespective of age, normal nutritional status was noted in about 55.5%–61.2% of the respondents, as shown in table 2. Underweight was reported to be highest at 31.3% among ≥60 years, while overweight and obesity were highest at 21.0% and 5.1%, respectively, among the 31–40 years age group. About 62.5% of men and 57.5% of women were within the normal range of weight. About 24.7% of men and 19.0% of women were underweight. Higher overweight and obesity were noted among women, with 18.8% and 4.6%, respectively. Irrespective of years of schooling, normal weight was recorded in 59.2% of the respondents. Being underweight was more common among those with no schooling (26.8%), while being overweight and obesityobese were more common among those with education up to or above secondary level (20.3% and 4.6%, respectively). Normal weight was seen in about 60.0%, irrespective of marital status. Being underweight was more common in those never married (29.3%), while being overweight and obese were more common in those ever married (17.0% and 3.7%, respectively). Being underweight was more common among unemployed and farmers, with 31.2% and 31.9%, respectively. On the other hand, being overweight was more common among service holders (23.8%) and being obese was more common among home makers (4.8%). The sociodemographic characteristics stratified by nutritional status were further stratified by sex (online supplemental table 2).

Table 2.

Sociodemographic characteristics of respondents, stratified by nutritional status (N=11 064)

| Variable | Category | n | Nutritional status, n (%) | |||

| Underweight | Normal weight | Overweight | Obese | |||

| Age (years) | ≤30 | 2184 | 517 (23.7) | 1336 (61.2) | 282 (12.9) | 49 (2.2) |

| 31–40 | 2419 | 348 (14.4) | 1439 (59.5) | 509 (21.0) | 123 (5.1) | |

| 41–50 | 2482 | 405 (16.3) | 1471 (59.3) | 498 (20.1) | 108 (4.4) | |

| 51–60 | 2097 | 455 (21.7) | 1257 (59.9) | 321 (15.3) | 64 (3.1) | |

| >60 | 1882 | 590 (31.3) | 1045 (55.5) | 200 (10.6) | 47 (2.5) | |

| Sex | Male | 3715 | 916 (24.7) | 2322 (62.5) | 427 (11.5) | 50 (1.3) |

| Female | 7349 | 1399 (19.0) | 4226 (57.5) | 1383 (18.8) | 341 (4.6) | |

| Education | No schooling | 3969 | 1064 (26.8) | 2349 (59.2) | 462 (11.6) | 94 (2.4) |

| Primary | 3171 | 627 (19.8) | 1877 (59.2) | 551 (17.4) | 116 (3.7) | |

| Secondary and above | 3924 | 624 (15.9) | 2322 (59.2) | 797 (20.3) | 181 (4.6) | |

| Marital status | Never married | 771 | 226 (29.3) | 475 (61.6) | 58 (7.5) | 12 (1.6) |

| Ever married | 10 293 | 2089 (20.3) | 6073 (59.0) | 1752 (17.0) | 379 (3.7) | |

| Occupation | Unemployed | 1057 | 330 (31.2) | 609 (57.6) | 92 (8.7) | 26 (2.5) |

| Service holder | 307 | 34 (11.1) | 191 (62.2) | 73 (23.8) | 9 (2.9) | |

| Farmer | 1353 | 431 (31.9) | 833 (61.6) | 80 (5.9) | 9 (0.7) | |

| Self-employed | 2416 | 448 (18.5) | 1514 (62.7) | 390 (16.1) | 64 (2.6) | |

| Housewife | 5931 | 1072 (18.1) | 3401 (57.3) | 1175 (19.8) | 283 (4.8) | |

Underweight: BMI is less than 18.5 kg/m2; normal weight: BMI is 18.5–25.0 kg/m2; overweight: BMI is 25.0–29.9 kg/m2; obese: BMI is over 30.0 kg/m2.

BMI, body mass index.

bmjopen-2021-051701supp002.pdf (84.5KB, pdf)

Behavioural risk factors

Nutritional status with respect to behavioural risk factors is shown in table 3. Irrespective of the risk factors considered, normal weight was noted in 57.3%–60.5% of the respondents. Considering each risk factor, being underweight was noted to be more common among those who led sedentary lifestyle (25.1%), did not take red meat (21.9%), ate fried food (21.3%), took sugary drinks (21.7%), took added salt (23.2%) and had inadequate intake of fruits and vegetables (21.4%). On the other hand, being overweight and obese were noted to be more common among those who did moderate to vigorous exercise (16.7% and 3.3%–3.9%, respectively), took red meat (19.9% and 4.0%), did not eat fried food (16.8% and 3.7%), did not take sugary drinks (16.9% and 3.6%), did not take added salt (19.3% and 4.7%), and those who did not take inadequate and took adequate fruits and vegetables (18.2% and 4.3%). Those who did not consume processed food were more likely to be overweight (16.5%), while those who consumed processed food were more likely to be obese (4.2%).

Table 3.

Behavioural risk factors of respondents, stratified by nutritional status (N=11 064)

| Variable | Category | n | Nutritional status, % (95% CI) | |||

| Underweight | Normal weight | Overweight | Obese | |||

| Physical activity | Sedentary | 1995 | 25.1 (23.2 to 27.0) | 57.3 (55.2 to 59.5) | 14.7 (13.2 to 16.4) | 2.9 (2.2 to 3.7) |

| Moderate | 3134 | 22.0 (20.6 to 23.5) | 58.0 (56.2 to 59.7) | 16.7 (15.5 to 18.1) | 3.3 (2.7 to 4.0) | |

| Vigorous | 5935 | 19.0 (18.0 to 20.0) | 60.4 (59.2 to 61.7) | 16.7 (15.8 to 17.7) | 3.9 (3.4 to 4.4) | |

| Red meat intake | Yes | 2687 | 17.9 (16.5 to 19.4) | 58.2 (56.3 to 60.0) | 19.9 (18.4 to 21.5) | 4.0 (3.3 to 4.8) |

| No | 8377 | 21.9 (21.0 to 22.8) | 59.5 (58.5 to 60.6) | 15.2 (14.5 to 16.0) | 3.4 (3.0 to 3.8) | |

| Fried food intake | Yes | 2949 | 21.3 (19.9 to 22.8) | 60.5 (58.7 to 62.2) | 15.2 (13.9 to 16.5) | 3.1 (2.5 to 3.7) |

| No | 8115 | 20.8 (19.9 to 21.7) | 58.7 (57.6 to 59.8) | 16.8 (16.0 to 17.6) | 3.7 (3.3 to 4.1) | |

| Processed food intake | Yes | 2278 | 20.9 (19.2 to 22.6) | 59.3 (57.3 to 61.3) | 15.6 (14.2 to 17.2) | 4.2 (3.5 to 5.1) |

| No | 8786 | 20.9 (20.1 to 21.8) | 59.2 (58.1 to 60.2) | 16.5 (15.8 to 17.3) | 3.4 (3.0 to 3.8) | |

| Sugary drinks intake | Yes | 4044 | 21.7 (20.4 to 23.0) | 59.6 (58.0 to 61.1) | 15.4 (14.3 to 16.5) | 3.4 (2.9 to 4.0) |

| No | 7020 | 20.5 (19.6 to 21.4) | 59.0 (57.8 to 60.1) | 16.9 (16.1 to 17.8) | 3.6 (3.2 to 4.1) | |

| Added salt intake | Yes | 6946 | 23.2 (22.2 to 24.2) | 59.3 (58.2 to 60.5) | 14.6 (13.8 to 15.5) | 2.9 (2.5 to 3.3) |

| No | 4118 | 17.1 (16.0 to 18.3) | 58.9 (57.4 to 60.4) | 19.3 (18.1 to 20.5) | 4.7 (4.1 to 5.4) | |

| Inadequate intake of fruits and vegetables | Yes | 8331 | 21.4 (20.6 to 22.3) | 59.5 (58.5 to 60.6) | 15.7 (15.0 to 16.5) | 3.3 (2.9 to 3.7) |

| No | 2733 | 19.4 (17.9 to 20.9) | 58.1 (56.3 to 60.0) | 18.2 (16.8 to 19.7) | 4.3 (3.6 to 5.1) | |

Underweight: BMI is less than 18.5 kg/m2; normal weight: BMI is 18.5–25.0 kg/m2; overweight: BMI is 25.0–29.9 kg/m2; obese: BMI is over 30.0 kg/m2.

BMI, body mass index.

Factors affecting malnutrition

Table 4 shows the multinomial regression analysis of the data. For this analysis, overweight and obese were merged into one variable as overweight/obese. It was found that the odds of being underweight will decrease by 0.25, 0.35, 0.40 and 0.14 if a respondent is less than 45 years of age, literate, married and consumed red meat, respectively. Employment, consumption of added salt and inactivity increase the odds of being underweight by 0.32, 0.33 and 0.14, respectively.

Table 4.

Factors affecting malnutrition in all its forms among the study population using multinomial regression analysis considering normal body weight as reference (N=11 064)

| Malnutrition | Factors | B | P value | AOR | 95% CI for OR | |

| Lower bound | Upper bound | |||||

| Underweight (BMI <18.5 kg/m2) | Age (years) | |||||

| <45 | −0.252 | <0.001* | 0.777 | 0.696 | 0.869 | |

| ≥45 | Reference | |||||

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | −0.147 | 0.050 | 0.863 | 0.745 | 1.000 | |

| Male | Reference | |||||

| Education | ||||||

| Literate | −0.346 | <0.001* | 0.707 | 0.634 | 0.789 | |

| Illiterate | Reference | |||||

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married | −0.396 | <0.001* | 0.673 | 0.542 | 0.835 | |

| Unmarried | Reference | |||||

| Occupation | ||||||

| Housewife | −0.037 | 0.634 | 0.964 | 0.828 | 1.122 | |

| Employed | 0.316 | 0.001* | 1.371 | 1.133 | 1.659 | |

| Unemployed | Reference | |||||

| Red meat intake | ||||||

| Yes | −0.141 | 0.019* | 0.869 | 0.772 | 0.977 | |

| No | Reference | |||||

| Added salt intake | ||||||

| Yes | 0.327 | <0.001* | 1.387 | 1.249 | 1.540 | |

| No | Reference | |||||

| Physical inactivity | ||||||

| Yes | 0.142 | 0.028* | 1.152 | 1.016 | 1.308 | |

| No | Reference | |||||

| Inadequate fruit/vegetable intake | ||||||

| Yes | 0.030 | 0.614 | 1.030 | 0.917 | 1.157 | |

| No | Reference | |||||

| Overweight/obesity (BMI ≥25.0 kg/m2) | Age (years) | |||||

| <45 | −0.039 | 0.477 | 0.961 | 0.862 | 1.072 | |

| ≥45 | Reference | |||||

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | 0.581 | <0.001* | 1.788 | 1.511 | 2.115 | |

| Male | Reference | |||||

| Education | ||||||

| Literate | 0.547 | <0.001* | 1.727 | 1.532 | 1.948 | |

| Illiterate | Reference | |||||

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married | 0.775 | <0.001* | 2.170 | 1.601 | 2.942 | |

| Unmarried | Reference | |||||

| Occupation | ||||||

| Housewife | 0.205 | 0.011* | 1.228 | 1.049 | 1.438 | |

| Employed | −0.108 | 0.407 | 0.897 | 0.695 | 1.159 | |

| Unemployed | Reference | |||||

| Red meat intake | ||||||

| Yes | 0.252 | <0.001* | 1.287 | 1.152 | 1.438 | |

| No | Reference | |||||

| Added salt intake | ||||||

| Yes | −0.378 | <0.001* | 0.685 | 0.619 | 0.758 | |

| No | Reference | |||||

| Physical inactivity | ||||||

| Yes | 0.017 | 0.813 | 1.017 | 0.886 | 1.167 | |

| No | Reference | |||||

| Inadequate fruit/vegetable intake | ||||||

| Yes | −0.181 | 0.002* | 0.835 | 0.745 | 0.935 | |

| No | Reference | |||||

*Significant at a threshold of p<0.05.

AOR, adjusted odds ratio; BMI, body mass index.

On the other hand, the odds of being overweight/obese increased by 0.58, 0.55, 0.78, 0.21 and 0.25 if the respondent was female, literate, married, housewife and consumed red meat, and decreased by 0.38 and 0.18 if the respondent consumed added salt and inadequate amount of fruits and vegetables, respectively. Consumption of added salt decreased the odds of being overweight/obese by 0.37.

Discussion

This cross-sectional study was undertaken among adult population in a selected rural area and was part of an implementation research. Census was used as the sampling strategy, but only a third of the population (those who attended the CC) were included in this study, for which reason the results do not represent census. Several studies have explored the various preconditions and posteffects of malnutrition in all its forms mostly with regard to modifiable sociodemographic factors. This study attempts to explore the same, but with regard to the status of modifiable lifestyle factors. While adequate knowledge and practices can modify the quality of diet and adjust lifestyles, the influence of a combination of economic, social and demographic factors also plays a key role in modifying these.6 Such complex phenomena may be assessed case by case to determine modification modalities so as to improve the overall health status of a population.

This study found that underweight, overweight and obesity are of similar concern among the adult rural population in Bangladesh. According to the WHO estimates, the age-standardised estimation of the prevalence of overweight among adults in South-East Asia was 21.9% in 2016, which was higher than that found in this study.17 A study in South Africa found that the mean waist circumference in rural men and women was much higher, putting them at high risk of NCDs.31 In a nationwide study in Bangladesh, the prevalence of overweight and obesity among children was found to be less than 10%.18 Other studies among the rural and urban populations of Bangladesh found that the prevalence of overweight and obesity was 15%–18.9% and 3%–4.6%, respectively.6 19–21 The occurrence of overweight and obesity found in this study was near similar to the combined overweight and obesity as found in other studies in Bangladesh. However, the population of other studies included everyone in the study area, while this study included only the adult population. It was noted in this study that factors such as extreme age, varied occupation and other physiodemographic features influenced the prevalence of obesity and overweight. Since this study was conducted in a surveillance population, the community members may already have been a little more aware of the importance of healthy lifestyles.

In this study, respondents in the 31–40 years age group were the most overweight and obese, while those 60 years and above were the most underweight. Women were found to be more overweight and obese than men, while men were found to be more underweight than women. The study also found that the likelihood of being overweight and obese increased among married and literate women, in contrast to unmarried and illiterate men. On the other hand, literate and married women less than 45 years were less likely to be underweight compared with illiterate and married men more than 45 years of age. Age between 33 and 37 years was also found significantly associated with obesity and overweight in other studies among rural women of Bangladesh (OR: 3.71; 95% CI 2.84 to 4.86; p<0.001).19 Other studies have shown that urban women aged 30–39 years were obese and/or overweight with a high association (OR: 3.9; 95% CI 1.9 to 7.7; p<0.001).23 There are studies that also showed that the prevalence of underweight among men more than 50 years of age was much high.20 32 The findings from this study corroborate with these earlier findings.

The odds of being overweight and obesity increased by 0.25 among respondents who consumed red meat and decreased by 0.38 and 0.18 among those who consumed added salt and inadequate amount of fruits and vegetables. On the other hand, consumption of added salt and inactivity increased the odds of being underweight by 0.33 and 0.14, respectively. A study on Malaysian adults showed that the prevalence of obesity and overweight was higher among men who did vigorous physical activity. In contrast, women who did moderate physical activity were more obese and overweight.33 Other studies also showed that being underweight was more often associated with vigorous physical activity, while being overweight and obese was more related to sedentary lifestyle. Variable associations were also noted with gender, education level, marital status, working status and wealth index.19 34 Most likely demographic features influence the source, amount and variety of food intake, and the type of physical activities undertaken based on knowledge and livelihood practices.

The food habit of the rural population in Bangladesh is low in fat and protein and high in carbohydrate.35–37 This may be why people who perform vigorous physical activity can avoid getting overweight or obese. At the same time if balance is not maintained between intake and output, there is increased likelihood of being obese or overweight, a phenomenon observed among a substantial number of subjects in this study. Rural women tend to regularly perform most household chores, some involving heavy activities, but these activities are not considered as such and overlooked by community members and health workers. Moreover, women tend to eat less food of poor quality while ensuring that other family members get more food of better quality.38 39 This may be why inactivity has been found to increase the likelihood of being underweight in this study. Studies show that the prevalence of previously undiagnosed comorbidities such as hypertension and diabetes is on the rise in the South-East Asian region.40 In Bangladesh, about 50%–80% of patients with diabetes and hypertension remain undiagnosed, with a significantly higher percentage among those from lower socioeconomic rural areas.27 30 People once diagnosed tend to visit health facilities more often than those who remain undiagnosed.

In its document on nutrition, the WHO has pointed at malnutrition in all its forms (characterised by coexisting undernutrition and overweight/obesity) and NCDs within individuals, households, populations and across the life course of individuals. Epidemiological evidence supports that undernutrition early in life, even when in utero, may predispose to overweight and NCDs later in life. At the same time, being underweight in later life is an expression of malnutrition. Again, overweight in mothers is often associated with overweight in their offspring. Biological mechanisms, along with environmental and social influences, are increasingly understood as essential drivers in the global burden of NCDs.38

In addition to increasing health literacy among the rural population through training and awareness programmes, the government may also take initiatives to encourage household backyard vegetable and fruit gardening, which would help to reduce the overall family expenditure. As an initial support, the government may distribute free (or at nominal price) saplings of fruits and vegetables among the rural population.

Strengths

The strength of this study is that it attempted to assess the current burden of malnutrition in all its forms and looked at the association of different modifiable risk factors with underweight, overweight and obesity among adults in a selected rural population of Bangladesh. Census was used as the sampling technique and data were collected from all adults except those institutionalised in a hospital, prison, nursing home or other similar institutes. Data from disabled or sick persons were collected from someone in the household who could provide the correct information. The number of such responses was very negligible and most likely did not affect the overall result.

Limitations

Although census was used as the sampling strategy, the study could only investigate a third of the individuals (those who attended the CC). As such, the results do not represent census. The limitation of this study was that household chores performed by women at home were not categorised into sedentary, moderate or vigorous activities, which may have affected the results. Some of the subjects included in the study may have been on medication or may have received lifestyle modification counselling and this may have also affected the results. On the other hand, people who were already diagnosed with diabetes or hypertension tend to visit health facilities more often than those who remain undiagnosed, for which reason the data collected at the CC may have been more on those who were already diagnosed before.

Conclusion

This cross-sectional study found that the prevalence of underweight was near equal to combined overweight and obesity among adults in a selected rural area of Bangladesh. Factors such as age, sex, education, marital status, physical inactivity and intake of added salt were strongly associated with being underweight, while factors such as sex, education, marital status, and consumption of red meat, added salt and fruits and vegetables were associated with being overweight and obese. Physical activity, along with eating habits, influences the nutritional status of adults. Sedentary lifestyle, along with less food consumption, leads to being underweight. Physically active persons who eat more food, such as red meat, tend to be overweight and obese. As such, considering the nutritional status, specific health messages to people on dietary habits and physical activity can go a long way to reduce underweight, overweight and obesity in the community. The effects of health messages can be further explored through qualitative studies so that policy makers and programme managers can take informed decisions while developing policies and implementing programmes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Genuine gratitude is due to the Non-Communicable Disease Control (NCDC) Programme of the Directorate General of Health Services (DGHS) for this study’s financial and technical support.

Footnotes

Twitter: @PalashChandraB7

Contributors: Conceptualisation: SM, AKMFR, MF, RAS, PCB, LB. Data curation: SR, LB. Formal analysis: SR, LB. Methodology: AKMFR, SM, MF, RAS, PCB, LB. Project administration: AKMFR, SM, MF, RAS, PCB, LB. Supervision: SM. Writing the original draft: SR. Writing: SR. Critic review: AKMFR, SM, MF, RAS, PCB, LB. Guarantor: SM

Funding: The study was funded by the Directorate General of Health Services (DGHS) Bangladesh (invitation ref no: DGHS/LD/NCDC/Procurement plan/(GOB) Service/2018-2019/2018/5214/SP-01).

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. The corresponding author will make the data available when required, with valid reasons.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

Ethics approval

Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethical Review Board of the Centre for Injury Prevention and Research, Bangladesh (ERC number: CIPRB/ERC/2019/003).

References

- 1.Branca F, Lartey A, Oenema S, et al. Transforming the food system to fight non-communicable diseases. BMJ 2019;364:l296. 10.1136/bmj.l296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases . Definition & Facts for Adult Overweight & Obesity. NIH, 2018. Available: https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/weight-management/adult-overweight-obesity/definition-facts

- 3.Reilly JJ, El-Hamdouchi A, Diouf A, et al. Determining the worldwide prevalence of obesity. Lancet 2018;391:1773–4. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30794-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization (WHO) . Obesity and overweight, 2018. Available: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight

- 5.World Health Organization (WHO) . 10 facts on obesity, 2017. Available: https://www.who.int/features/factfiles/obesity/en/

- 6.Biswas T, Garnett SP, Pervin S, et al. The prevalence of underweight, overweight and obesity in Bangladeshi adults: data from a national survey. PLoS One 2017;12:e0177395. 10.1371/journal.pone.0177395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) . Adult Obesity Causes & Consequences, 2019. Available: https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/adult/causes.html

- 8.Biswas T, Pervin S, Tanim MIA, et al. Bangladesh policy on prevention and control of non-communicable diseases: a policy analysis. BMC Public Health 2017;17:582. 10.1186/s12889-017-4494-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nyberg ST, Batty GD, Pentti J, et al. Obesity and loss of disease-free years owing to major non-communicable diseases: a multicohort study. Lancet Public Health 2018;3:e490–7. 10.1016/S2468-2667(18)30139-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Russell S, Sturua L, Li C, et al. The burden of non-communicable diseases and their related risk factors in the country of Georgia, 2015. BMC Public Health 2019;19:479. 10.1186/s12889-019-6785-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bhutani J, Bhutani S. Worldwide burden of diabetes. Indian J Endocrinol Metab 2014;18:868–70. 10.4103/2230-8210.141388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Loomba RS, Aggarwal S, Arora R. Depressive symptom frequency and prevalence of cardiovascular Diseases-Analysis of patients in the National health and nutrition examination survey. Am J Ther 2015;22:382–7. 10.1097/MJT.0000000000000043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lozano R, Naghavi M, Foreman K, et al. Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2010. Lancet 2012;380:2095–128. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61728-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Woodyard C. Exploring the therapeutic effects of yoga and its ability to increase quality of life. Int J Yoga 2011;4:49–54. 10.4103/0973-6131.85485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Afable A, Karingula NS. Evidence based review of type 2 diabetes prevention and management in low and middle income countries. World J Diabetes 2016;7:209–29. 10.4239/wjd.v7.i10.209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Casazza K, Brown A, Astrup A, et al. Weighing the evidence of common beliefs in obesity research. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2015;55:2014–53. 10.1080/10408398.2014.922044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.World Health Organization (WHO) . Global health Observatory data Repository (south-east Asia region), 2016. Available: http://apps.who.int/gho/data/view.main-searo.GLOBAL2461A?lang=en

- 18.Bulbul T, Hoque M. Prevalence of childhood obesity and overweight in Bangladesh: findings from a countrywide epidemiological study. BMC Pediatr 2014;14:86. 10.1186/1471-2431-14-86 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sarma H, Saquib N, Hasan MM, et al. Determinants of overweight or obesity among ever-married adult women in Bangladesh. BMC Obes 2016;3:13. 10.1186/s40608-016-0093-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Banik S, Rahman M. Prevalence of overweight and obesity in Bangladesh: a systematic review of the literature. Curr Obes Rep 2018;7:247–53. 10.1007/s13679-018-0323-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Najafipour H, Yousefzadeh G, Forood A, et al. Overweight and obesity prevalence and its predictors in a general population: a community-based study in Kerman, Iran (Kerman coronary artery diseases risk factors studies). ARYA Atheroscler 2016;12:18–27. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tanwi TS, Chakrabarty S, Hasanuzzaman S, et al. Socioeconomic correlates of overweight and obesity among ever-married urban women in Bangladesh. BMC Public Health 2019;19:842. 10.1186/s12889-019-7221-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chowdhury MAB, Adnan MM, Hassan MZ. Trends, prevalence and risk factors of overweight and obesity among women of reproductive age in Bangladesh: a pooled analysis of five national cross-sectional surveys. BMJ Open 2018;8:e018468. 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Islam F, Kathak RR, Sumon AH, et al. Prevalence and associated risk factors of general and abdominal obesity in rural and urban women in Bangladesh. PLoS One 2020;15:e0233754. 10.1371/journal.pone.0233754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ali N, Huda T, Islam S, et al. The prevalence and risk factors of overweight and obesity among women of reproductive age with iron deficiency anaemia in urban Bangladesh (P10-064-19). Curr Dev Nutr 2019;3:nzz034.P10–064–19. 10.1093/cdn/nzz034.P10-064-19 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Banna MHA, Brazendale K, Hasan M, et al. Factors associated with overweight and obesity among Bangladeshi university students: a case–control study. J Am Coll Health 2020;59:1–7. 10.1080/07448481.2020.1851695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Municipality of Pateros . Manual on the pen protocol on the integrated management of hypertension and diabetes (adapted from the who package of essential non-communicable intervention protocol), 2011. Available: https://www.who.int/ncds/management/Manual_of_Procedures_on_WHO_PEN_PHL.pdf

- 28.World Health Organization (WHO) . Factsheet: healthy diet, 2020. Available: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/healthy-diet

- 29.World Health Organization . Non-Communicable disease risk factor survey Bangladesh 2010. SEARO, new Delhi, 2011. Available: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/searo/bangladesh/pdf-reports/year-2007-2012/non-communicable-disease-risk-factor-survey-bangladesh-2010.pdf?sfvrsn=37e45e81_2

- 30.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) . Defining adult overweight and obesity, 2017. Available: https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/adult/defining.html

- 31.Tydeman-Edwards R, Van Rooyen FC, Walsh CM. Obesity, undernutrition and the double burden of malnutrition in the urban and rural southern free state, South Africa. Heliyon 2018;4:e00983. 10.1016/j.heliyon.2018.e00983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Selvamani Y, Singh P. Socioeconomic patterns of underweight and its association with self-rated health, cognition and quality of life among older adults in India. PLoS One 2018;13:e0193979. 10.1371/journal.pone.0193979 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chan YY, Lim KK, Lim KH, et al. Physical activity and overweight/obesity among Malaysian adults: findings from the 2015 National health and morbidity survey (NHMS). BMC Public Health 2017;17:733. 10.1186/s12889-017-4772-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Khan MMA, Karim M, Islam AZ, et al. Prevalence of overweight and obesity among adolescents in Bangladesh: do eating habits and physical activity have a gender differential effect? J Biosoc Sci 2019;51:843–56. 10.1017/S0021932019000142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sheema MK, Rahman R, Yasmin Z, et al. Food habit and nutritional status of rural women in Bangladesh. American Journal of Rural Development 2016;4:114–9. [Google Scholar]

- 36.World Health Organization (WHO) & Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) . Preparation and use of food-based dietary guidelines, 1998. Available: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/42051/WHO_TRS_880.pdf?sequence=1

- 37.Kabir Y, Shahjalal HM, Saleh F, et al. Dietary pattern, nutritional status, anaemia and anaemia-related knowledge in urban adolescent College girls of Bangladesh. J Pak Med Assoc 2010;60:633–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.World Health Organization (WHO) . Double burden of malnutrition, 2021. Available: https://www.who.int/nutrition/double-burden-malnutrition/en/

- 39.Torres A, Willett W, Orav J, et al. Variability of total energy and protein intake in rural Bangladesh: implications for epidemiological studies of diet in developing countries. Food Nutr Bull 1990;12:1–9. 10.1177/156482659001200308 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mohan V, Seedat YK, Pradeepa R. The rising burden of diabetes and hypertension in Southeast Asian and African regions: need for effective strategies for prevention and control in primary health care settings. Int J Hypertens 2013;2013:1–14. 10.1155/2013/409083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2021-051701supp001.pdf (80KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2021-051701supp002.pdf (84.5KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. The corresponding author will make the data available when required, with valid reasons.